Ice Trade on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ice trade, also known as the frozen water trade, was a 19th-century and early-20th-century industry, centering on the east coast of the

The ice trade, also known as the frozen water trade, was a 19th-century and early-20th-century industry, centering on the east coast of the

Prior to the emergence of the ice trade of the 19th century, snow and ice had been collected and stored to use in the summer months in various parts of the world, but never on a large scale. In the

Prior to the emergence of the ice trade of the 19th century, snow and ice had been collected and stored to use in the summer months in various parts of the world, but never on a large scale. In the

The ice trade began in 1806 as the result of the efforts of Frederic Tudor, a

The ice trade began in 1806 as the result of the efforts of Frederic Tudor, a  The price of the imported ice varied according to the amount of competition; in Havana, Tudor's ice sold for 25 cents ($3.70 in 2010 terms) per pound, while in Georgia it reached only six to eight cents ($0.90–$1.20 in 2010 terms). Where Tudor had a strong market share, he would respond to competition from passing traders by lowering his prices considerably, selling his ice at the unprofitable rate of one cent ($0.20) per pound (0.5 kg); at this price, competitors would typically be unable to sell their own stock at a profit: they would either be driven into debt or if they declined to sell, their ice would melt away in the heat. Tudor, relying on his local storage depots, could then increase his prices once again.Cummings, p. 15. By the middle of the 1820s, around 3,000 tons (3 million kg) of ice was being shipped from Boston annually, two thirds by Tudor.

At these lower prices, ice began to sell in considerable volumes, with the market moving beyond the wealthy elite to a wider range of consumers, to the point where supplies became overstretched. Ice was also being used by tradesmen to preserve perishable goods, rather than for direct consumption. Tudor looked beyond his existing suppliers to Maine and even to harvesting from passing

The price of the imported ice varied according to the amount of competition; in Havana, Tudor's ice sold for 25 cents ($3.70 in 2010 terms) per pound, while in Georgia it reached only six to eight cents ($0.90–$1.20 in 2010 terms). Where Tudor had a strong market share, he would respond to competition from passing traders by lowering his prices considerably, selling his ice at the unprofitable rate of one cent ($0.20) per pound (0.5 kg); at this price, competitors would typically be unable to sell their own stock at a profit: they would either be driven into debt or if they declined to sell, their ice would melt away in the heat. Tudor, relying on his local storage depots, could then increase his prices once again.Cummings, p. 15. By the middle of the 1820s, around 3,000 tons (3 million kg) of ice was being shipped from Boston annually, two thirds by Tudor.

At these lower prices, ice began to sell in considerable volumes, with the market moving beyond the wealthy elite to a wider range of consumers, to the point where supplies became overstretched. Ice was also being used by tradesmen to preserve perishable goods, rather than for direct consumption. Tudor looked beyond his existing suppliers to Maine and even to harvesting from passing

The trade in New England ice expanded during the 1830s and 1840s across the eastern coast of the U.S., while new trade routes were created across the world. The first and most profitable of these new routes was to India: in 1833 Tudor combined with the businessmen Samuel Austin and William Rogers to attempt to export ice to

The trade in New England ice expanded during the 1830s and 1840s across the eastern coast of the U.S., while new trade routes were created across the world. The first and most profitable of these new routes was to India: in 1833 Tudor combined with the businessmen Samuel Austin and William Rogers to attempt to export ice to  New England businessmen also tried to establish a market for ice in England during the 1840s. An abortive first attempt to export ice to England had occurred in 1822 under William Leftwich; he had imported ice from

New England businessmen also tried to establish a market for ice in England during the 1840s. An abortive first attempt to export ice to England had occurred in 1822 under William Leftwich; he had imported ice from

The 1850s was a period of transition for the ice trade. The industry was already quite large: in 1855 around $6–7 million ($118–138 million in 2010 terms) was invested in the industry in the U.S., and an estimated two million tons (two billion kg) of ice was kept in storage at any one time in warehouses across the nation. Over the coming decade, however, the focus of the growing trade shifted away from relying upon the international export market in favour of supplying first the growing, eastern cities of the US, and then the rest of the rapidly expanding country.

In 1850, California was in the midst of a gold rush; backed by this sudden demand for luxuries, New England companies made the first shipments, by ship to

The 1850s was a period of transition for the ice trade. The industry was already quite large: in 1855 around $6–7 million ($118–138 million in 2010 terms) was invested in the industry in the U.S., and an estimated two million tons (two billion kg) of ice was kept in storage at any one time in warehouses across the nation. Over the coming decade, however, the focus of the growing trade shifted away from relying upon the international export market in favour of supplying first the growing, eastern cities of the US, and then the rest of the rapidly expanding country.

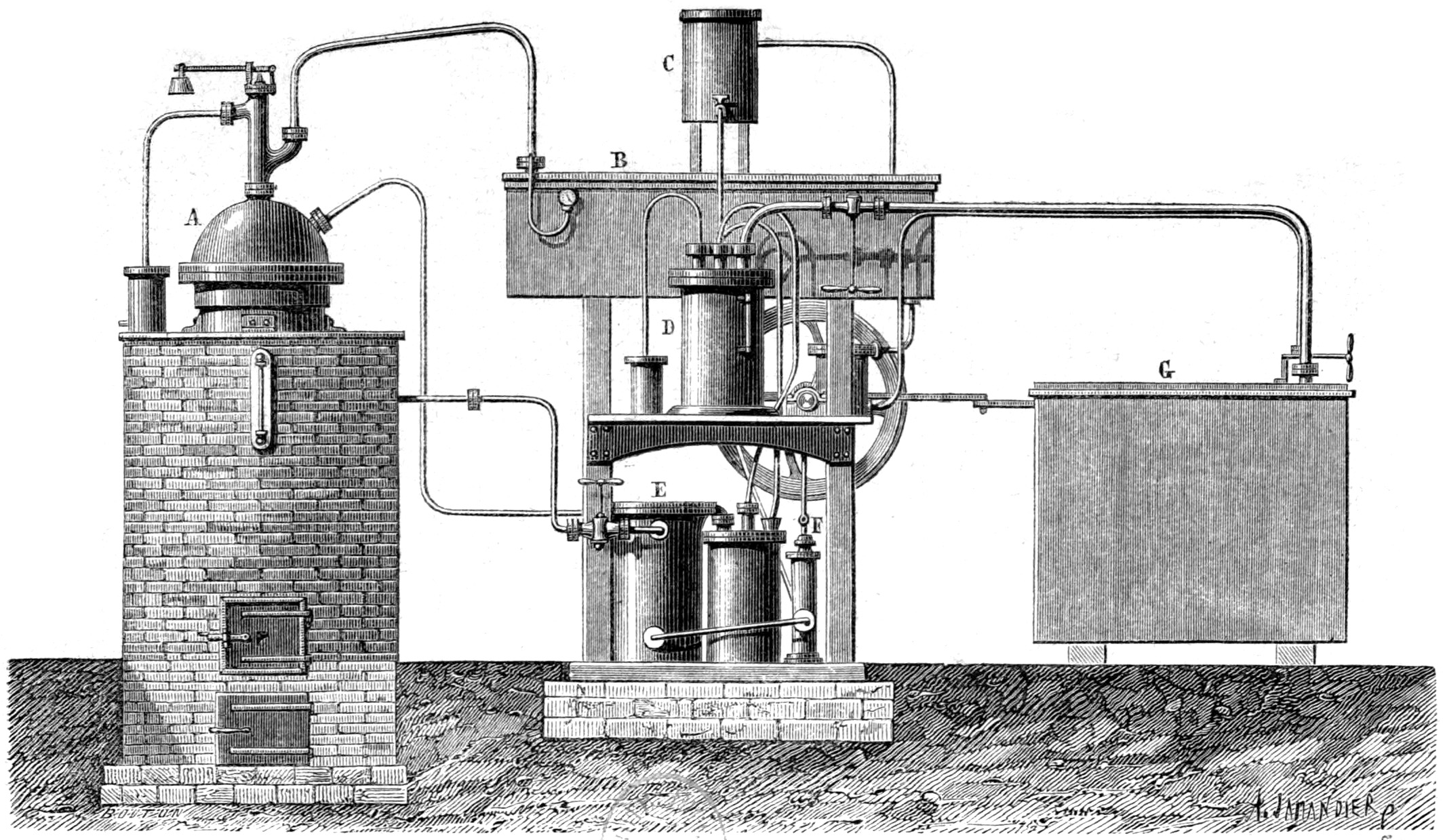

In 1850, California was in the midst of a gold rush; backed by this sudden demand for luxuries, New England companies made the first shipments, by ship to  Meanwhile, it had been known since 1748 that it was possible to artificially chill water with mechanical equipment, and attempts were made in the late 1850s to produce artificial ice on a commercial scale. Various methods had been invented to do this, including Jacob Perkins's

Meanwhile, it had been known since 1748 that it was possible to artificially chill water with mechanical equipment, and attempts were made in the late 1850s to produce artificial ice on a commercial scale. Various methods had been invented to do this, including Jacob Perkins's

The international ice trade continued through the second half of the 19th century, but it increasingly moved away from its former, New England roots. Indeed, ice exports from the US peaked around 1870, when 65,802 tons (59,288,000 kg), worth $267,702 ($4,610,000 in 2010 terms), were shipped out from the ports. One factor in this was the slow spread of plant ice into India. Exports from New England to India peaked in 1856, when 146,000 tons (132 million kg) were shipped, and the Indian natural ice market faltered during the

The international ice trade continued through the second half of the 19th century, but it increasingly moved away from its former, New England roots. Indeed, ice exports from the US peaked around 1870, when 65,802 tons (59,288,000 kg), worth $267,702 ($4,610,000 in 2010 terms), were shipped out from the ports. One factor in this was the slow spread of plant ice into India. Exports from New England to India peaked in 1856, when 146,000 tons (132 million kg) were shipped, and the Indian natural ice market faltered during the  The eastern market for ice in the U.S. was also changing. Cities like New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia saw their population boom in the second half of the century; New York tripled in size between 1850 and 1890, for example.Parker, p. 2. This drove up the demand for ice considerably across the region. By 1879, householders in the eastern cities were consuming two thirds of a ton (601 kg) of ice a year, being charged 40 cents ($9.30) per 100 pounds (45 kg); 1,500 wagons were needed just to deliver ice to consumers in New York.

In supplying this demand, the ice trade increasingly shifted north, away from Massachusetts and towards Maine. Various factors contributed to this. New Englands' winters became warmer during the 19th century, while industrialisation resulted in more of the natural ponds and rivers becoming contaminated. Less trade was brought through New England as other ways of reaching western US markets were opened up, making it less profitable to trade ice from Boston, while the cost of producing ships in the region increased due to deforestation.Dickason, p. 81. Finally, in 1860 there was the first of four ice famines along the Hudson-warm winters that prevented the formation of ice in New England-creating shortages and driving up prices.

The outbreak of the

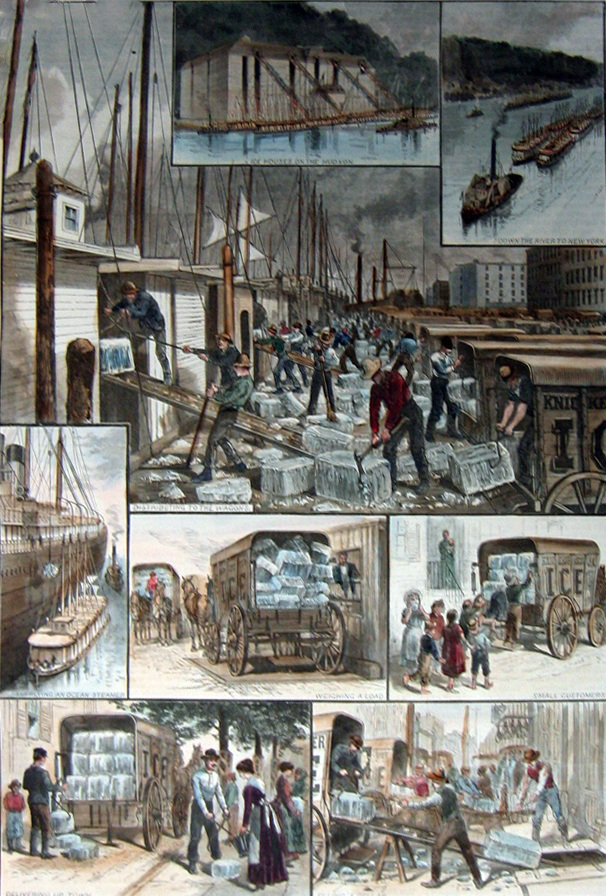

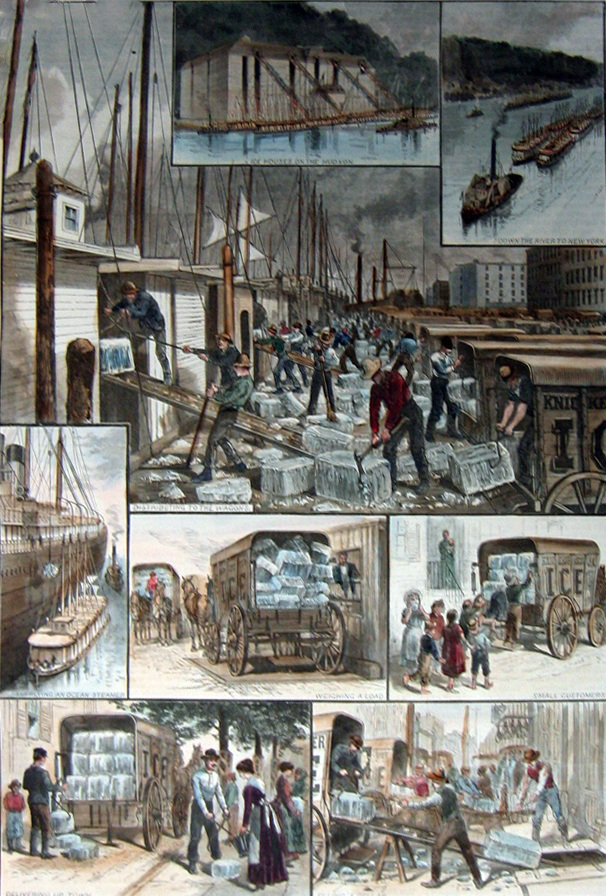

The eastern market for ice in the U.S. was also changing. Cities like New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia saw their population boom in the second half of the century; New York tripled in size between 1850 and 1890, for example.Parker, p. 2. This drove up the demand for ice considerably across the region. By 1879, householders in the eastern cities were consuming two thirds of a ton (601 kg) of ice a year, being charged 40 cents ($9.30) per 100 pounds (45 kg); 1,500 wagons were needed just to deliver ice to consumers in New York.

In supplying this demand, the ice trade increasingly shifted north, away from Massachusetts and towards Maine. Various factors contributed to this. New Englands' winters became warmer during the 19th century, while industrialisation resulted in more of the natural ponds and rivers becoming contaminated. Less trade was brought through New England as other ways of reaching western US markets were opened up, making it less profitable to trade ice from Boston, while the cost of producing ships in the region increased due to deforestation.Dickason, p. 81. Finally, in 1860 there was the first of four ice famines along the Hudson-warm winters that prevented the formation of ice in New England-creating shortages and driving up prices.

The outbreak of the  Another ice famine in 1870 then impacted both Boston and the Hudson, with a further famine following in 1880; as a result entrepreneurs descended on the

Another ice famine in 1870 then impacted both Boston and the Hudson, with a further famine following in 1880; as a result entrepreneurs descended on the

Although the manufacture of artificial plant ice was still negligible in 1880, it began to grow in volume towards the end of the century as technological improvements finally allowed the production of plant ice at a competitive price. Typically ice plants first took hold in more distant locations where natural ice was at a cost disadvantage. The Australian and Indian markets were already dominated by plant ice, and ice plants began to be built in Brazil during the 1880s and 1890s, slowly coming to replace imported ice. In the U.S., plants began to become more numerous in the southern states. The long-distance transportation companies continued to use cheap natural ice for the bulk of their refrigeration needs, but they now used purchased local plant ice at key points across the US, to allow for surge demand and to avoid the need to hold reserve stocks of natural ice. After 1898 the British fishing industry, too, began to turn to plant ice to refrigerate its catches.Cummings, pp. 83, 90; Blain, p. 27.

Plant technology began to be turned to the problem of directly chilling rooms and containers, to replace the need to carry ice at all. Pressure began to grow for a replacement for ice bunkers on the trans-Atlantic routes during the 1870s. Tellier produced a chilled storeroom for the steamship ''Le Frigorifique'', using it to ship beef from Argentina to France, while the Glasgow-based firm of Bells helped to sponsor a new, compressed-air chiller for ships using the Gorrie approach, called the Bell-Coleman design. These technologies soon became used on the trade to Australia, New Zealand and Argentina. The same approach began to be taken in other industries.

Although the manufacture of artificial plant ice was still negligible in 1880, it began to grow in volume towards the end of the century as technological improvements finally allowed the production of plant ice at a competitive price. Typically ice plants first took hold in more distant locations where natural ice was at a cost disadvantage. The Australian and Indian markets were already dominated by plant ice, and ice plants began to be built in Brazil during the 1880s and 1890s, slowly coming to replace imported ice. In the U.S., plants began to become more numerous in the southern states. The long-distance transportation companies continued to use cheap natural ice for the bulk of their refrigeration needs, but they now used purchased local plant ice at key points across the US, to allow for surge demand and to avoid the need to hold reserve stocks of natural ice. After 1898 the British fishing industry, too, began to turn to plant ice to refrigerate its catches.Cummings, pp. 83, 90; Blain, p. 27.

Plant technology began to be turned to the problem of directly chilling rooms and containers, to replace the need to carry ice at all. Pressure began to grow for a replacement for ice bunkers on the trans-Atlantic routes during the 1870s. Tellier produced a chilled storeroom for the steamship ''Le Frigorifique'', using it to ship beef from Argentina to France, while the Glasgow-based firm of Bells helped to sponsor a new, compressed-air chiller for ships using the Gorrie approach, called the Bell-Coleman design. These technologies soon became used on the trade to Australia, New Zealand and Argentina. The same approach began to be taken in other industries.  Despite this emerging competition, natural ice remained vital to North American and European economies, with demand driven up by rising living standards. The huge demand for ice in the 1880s drove the natural ice trade to continue to expand. Around four million tons (four billion kg) of ice was routinely stored along the Hudson River and Maine alone, the Hudson having around 135 major warehouses along its banks and employing 20,000 workers. Firms expanded along the Kennebec River in Maine to meet the demand, and 1,735 vessels were required in 1880 to carry the ice south. Lakes in

Despite this emerging competition, natural ice remained vital to North American and European economies, with demand driven up by rising living standards. The huge demand for ice in the 1880s drove the natural ice trade to continue to expand. Around four million tons (four billion kg) of ice was routinely stored along the Hudson River and Maine alone, the Hudson having around 135 major warehouses along its banks and employing 20,000 workers. Firms expanded along the Kennebec River in Maine to meet the demand, and 1,735 vessels were required in 1880 to carry the ice south. Lakes in

In the years after the war, the natural ice industry collapsed into insignificance.Cummings, p. 112. Industry turned entirely to plant ice and mechanical cooling systems, and the introduction of cheap electric motors resulted in domestic, modern refrigerators becoming common in U.S. homes by the 1930s and more widely across Europe in the 1950s, allowing ice to be made in the home. The natural ice harvests shrunk dramatically, and ice warehouses were abandoned or converted for other uses. The use of natural ice on a small scale lingered on in more remote areas for some years, and ice continued to be occasionally harvested for

In the years after the war, the natural ice industry collapsed into insignificance.Cummings, p. 112. Industry turned entirely to plant ice and mechanical cooling systems, and the introduction of cheap electric motors resulted in domestic, modern refrigerators becoming common in U.S. homes by the 1930s and more widely across Europe in the 1950s, allowing ice to be made in the home. The natural ice harvests shrunk dramatically, and ice warehouses were abandoned or converted for other uses. The use of natural ice on a small scale lingered on in more remote areas for some years, and ice continued to be occasionally harvested for

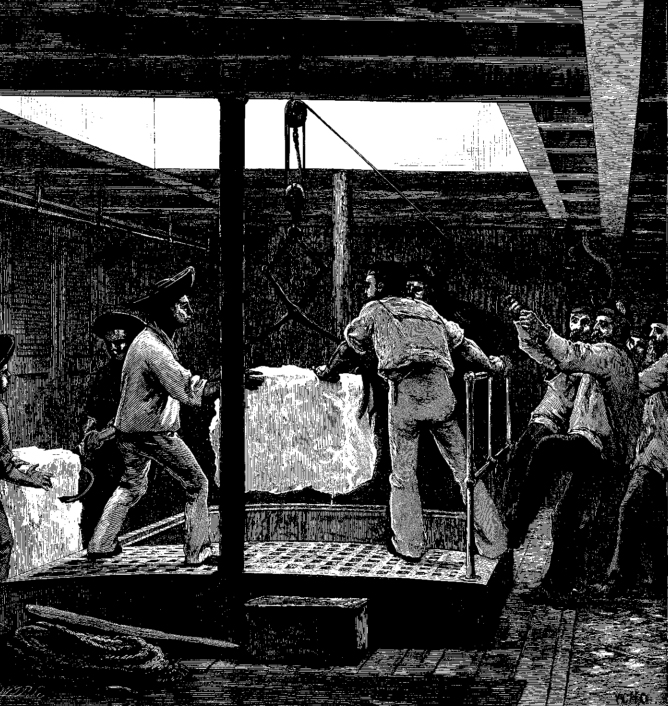

The ice-cutting involved several stages and was typically carried out at night, when the ice was thickest. First the surface would be cleaned of snow with scrapers, the depth of the ice tested for suitability, then the surface would be marked out with cutters to produce the lines of the future ice blocks. The size of the blocks varied according to the destination, the largest being for the furthest locations, the smallest destined for the American east coast itself and being only 22 inches (0.56 m) square. The blocks could finally be cut out of the ice and floated to the shore. The speed of the operation might depend on the likelihood of warmer weather affecting the ice. In both New England and Norway, harvesting occurred during an otherwise quiet season, providing valuable local employment.

The process required a range of equipment. Some of this was protective equipment to allow the workforce and horses to operate safely on ice, including cork shoes for the men and spiked horse shoes. Early in the 19th century only ad hoc, improvised tools such as pickaxes and chisels were used for the rest of the harvest, but in the 1840s Wyeth introduced various new designs to allow for a larger-scale, more commercial harvesting process. These included a horse-drawn ice cutter, resembling a

The ice-cutting involved several stages and was typically carried out at night, when the ice was thickest. First the surface would be cleaned of snow with scrapers, the depth of the ice tested for suitability, then the surface would be marked out with cutters to produce the lines of the future ice blocks. The size of the blocks varied according to the destination, the largest being for the furthest locations, the smallest destined for the American east coast itself and being only 22 inches (0.56 m) square. The blocks could finally be cut out of the ice and floated to the shore. The speed of the operation might depend on the likelihood of warmer weather affecting the ice. In both New England and Norway, harvesting occurred during an otherwise quiet season, providing valuable local employment.

The process required a range of equipment. Some of this was protective equipment to allow the workforce and horses to operate safely on ice, including cork shoes for the men and spiked horse shoes. Early in the 19th century only ad hoc, improvised tools such as pickaxes and chisels were used for the rest of the harvest, but in the 1840s Wyeth introduced various new designs to allow for a larger-scale, more commercial harvesting process. These included a horse-drawn ice cutter, resembling a

Early in the ice trade, there were few restrictions on harvesting ice in the U.S., as it had traditionally held little value and was seen as a

Early in the ice trade, there were few restrictions on harvesting ice in the U.S., as it had traditionally held little value and was seen as a

Natural ice typically had to be moved several times between being harvested and used by the end customer. A wide range of methods were used, including wagons, railroads, ships and barges. Ships were particularly important to the ice trade, particularly in the early phase of the trade, when the focus of the trade was on international exports from the U.S. and railroad networks across the country were non-existent.

Typically, ice traders hired vessels to ship ice as freight, although Frederic Tudor initially purchased his own vessel and the Tudor Company later bought three fast cargo ships of its own in 1877.Bunting, p. 26. Ice was first transported in ships at the end of the 18th century, when it was occasionally used as ballast. Shipping ice as ballast, however, required it to be cleanly cut in order to avoid it shifting around as it melted, which was not easily done until Wyeth's invention of the ice-cutter in 1825. The uniform blocks that Wyeth's process produced also made it possible to pack more ice into the limited space of a ship's hold, and significantly reduced the losses from melting. The ice was typically packed up tightly with sawdust, and the hold was then closed to prevent warmer air entering; other forms of protective

Natural ice typically had to be moved several times between being harvested and used by the end customer. A wide range of methods were used, including wagons, railroads, ships and barges. Ships were particularly important to the ice trade, particularly in the early phase of the trade, when the focus of the trade was on international exports from the U.S. and railroad networks across the country were non-existent.

Typically, ice traders hired vessels to ship ice as freight, although Frederic Tudor initially purchased his own vessel and the Tudor Company later bought three fast cargo ships of its own in 1877.Bunting, p. 26. Ice was first transported in ships at the end of the 18th century, when it was occasionally used as ballast. Shipping ice as ballast, however, required it to be cleanly cut in order to avoid it shifting around as it melted, which was not easily done until Wyeth's invention of the ice-cutter in 1825. The uniform blocks that Wyeth's process produced also made it possible to pack more ice into the limited space of a ship's hold, and significantly reduced the losses from melting. The ice was typically packed up tightly with sawdust, and the hold was then closed to prevent warmer air entering; other forms of protective  Ships carrying ice needed to be particularly strong, and there was a premium placed on recruiting good crews, able to move the cargo quickly to its location before it melted. By the end of the 19th century, the preferred choice was a wooden-hulled vessel, to avoid

Ships carrying ice needed to be particularly strong, and there was a premium placed on recruiting good crews, able to move the cargo quickly to its location before it melted. By the end of the 19th century, the preferred choice was a wooden-hulled vessel, to avoid  For much of the 19th century, it was particularly cheap to transport ice from New England and other key ice-producing centres, helping to grow the industry.Dickason, p. 64. The region's role as a gateway for trade with the interior of the U.S. meant that trading ships brought more cargoes to the ports than there were cargoes to take back; unless they could find a return cargo, ships would need to carry rocks as ballast instead. Ice was the only profitable alternative to rocks and, as a result, the ice trade from New England could negotiate lower shipping rates than would have been possible from other international locations. Later in the century, the ice trade between Maine and New York took advantage of Maine's emerging requirements for Philadelphia's coal: the ice ships delivering ice from Maine would bring back the fuel, leading to the trade being termed the "ice and coaling" business.

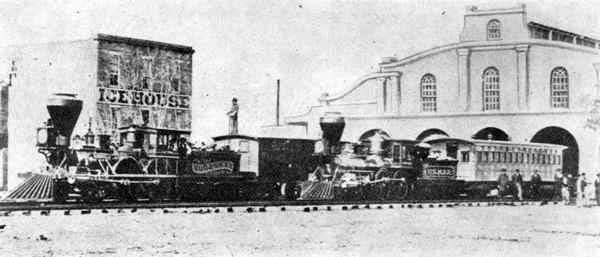

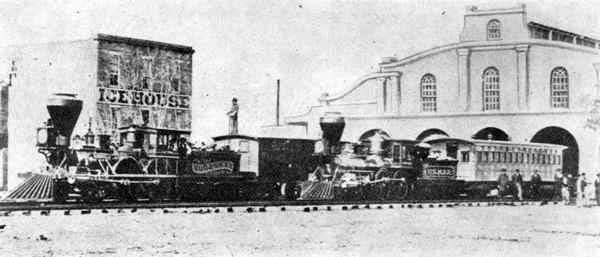

Ice was also transported by railroad from 1841 onwards, the first use of the technique being on the track laid down between Fresh Pond and Charleston by the Charlestown Branch Railroad Company. A special railroad car was built to insulate the ice and equipment designed to allow the cars to be loaded.Cummings, p. 45. In 1842 a new railroad to Fitchburg was used to access the ice at Walden Pond. Ice was not a popular cargo with railway employees, however, as it had to be moved promptly to avoid melting and was generally awkward to transport. By the 1880s ice was being shipped by rail across the North American continent.

The final part of the supply chain for domestic and smaller commercial customers involved the delivery of ice, typically using an ice wagon. In the U.S., ice was cut into 25-, 50- and 100-pound blocks (11, 23 and 45 kg) then distributed by horse-drawn ice wagons. An iceman, driving the cart, would then deliver the ice to the household, using ice tongs to hold the cubes. Deliveries could occur either daily or twice daily. By the 1870s, various specialist distributors existed in the major cities, with local fuel dealers or other businesses selling and delivering ice in the smaller communities. In Britain, ice was rarely sold to domestic customers via specialist dealers during the 19th century, instead usually being sold through

For much of the 19th century, it was particularly cheap to transport ice from New England and other key ice-producing centres, helping to grow the industry.Dickason, p. 64. The region's role as a gateway for trade with the interior of the U.S. meant that trading ships brought more cargoes to the ports than there were cargoes to take back; unless they could find a return cargo, ships would need to carry rocks as ballast instead. Ice was the only profitable alternative to rocks and, as a result, the ice trade from New England could negotiate lower shipping rates than would have been possible from other international locations. Later in the century, the ice trade between Maine and New York took advantage of Maine's emerging requirements for Philadelphia's coal: the ice ships delivering ice from Maine would bring back the fuel, leading to the trade being termed the "ice and coaling" business.

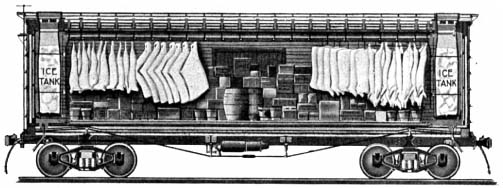

Ice was also transported by railroad from 1841 onwards, the first use of the technique being on the track laid down between Fresh Pond and Charleston by the Charlestown Branch Railroad Company. A special railroad car was built to insulate the ice and equipment designed to allow the cars to be loaded.Cummings, p. 45. In 1842 a new railroad to Fitchburg was used to access the ice at Walden Pond. Ice was not a popular cargo with railway employees, however, as it had to be moved promptly to avoid melting and was generally awkward to transport. By the 1880s ice was being shipped by rail across the North American continent.

The final part of the supply chain for domestic and smaller commercial customers involved the delivery of ice, typically using an ice wagon. In the U.S., ice was cut into 25-, 50- and 100-pound blocks (11, 23 and 45 kg) then distributed by horse-drawn ice wagons. An iceman, driving the cart, would then deliver the ice to the household, using ice tongs to hold the cubes. Deliveries could occur either daily or twice daily. By the 1870s, various specialist distributors existed in the major cities, with local fuel dealers or other businesses selling and delivering ice in the smaller communities. In Britain, ice was rarely sold to domestic customers via specialist dealers during the 19th century, instead usually being sold through

Ice had to be stored at multiple points between harvesting and its final use by a customer. One method for doing this was the construction of ice houses to hold the product, typically either shortly after the ice was first harvested or at regional depots after it had been shipped out. Early ice houses were relatively small, but later storage facilities were the size of large warehouses and contained much larger quantities of ice.

The understanding of

Ice had to be stored at multiple points between harvesting and its final use by a customer. One method for doing this was the construction of ice houses to hold the product, typically either shortly after the ice was first harvested or at regional depots after it had been shipped out. Early ice houses were relatively small, but later storage facilities were the size of large warehouses and contained much larger quantities of ice.

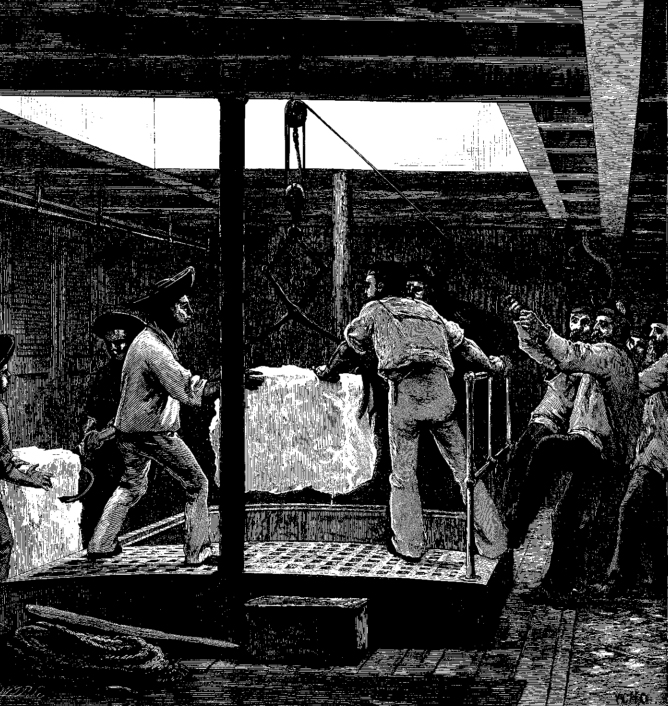

The understanding of  The size of the ice houses made it difficult to load ice into them; in 1827 Wyeth invented a

The size of the ice houses made it difficult to load ice into them; in 1827 Wyeth invented a

The ice trade enabled the consumption of a wide range of new products during the 19th century. One simple use for natural ice was to chill drinks, either being directly added to the glass or barrel, or indirectly chilling it in a

The ice trade enabled the consumption of a wide range of new products during the 19th century. One simple use for natural ice was to chill drinks, either being directly added to the glass or barrel, or indirectly chilling it in a

The ice trade revolutionised the way that food was preserved and transported. Before the 19th century, preservation had depended upon techniques such as curing or

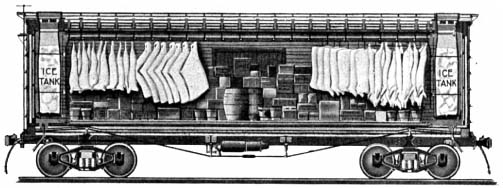

The ice trade revolutionised the way that food was preserved and transported. Before the 19th century, preservation had depended upon techniques such as curing or  With the development of the U.S. railroad system, natural ice became used to transport larger quantities of goods much longer distances through the invention of the

With the development of the U.S. railroad system, natural ice became used to transport larger quantities of goods much longer distances through the invention of the

The ice trade, also known as the frozen water trade, was a 19th-century and early-20th-century industry, centering on the east coast of the

The ice trade, also known as the frozen water trade, was a 19th-century and early-20th-century industry, centering on the east coast of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

, involving the large-scale harvesting, transport and sale of natural ice, and later the making and sale of artificial ice, for domestic consumption and commercial purposes. Ice was cut from the surface of ponds and streams, then stored in ice houses, before being sent on by ship, barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels. ...

or railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

to its final destination around the world. Networks of ice wagons were typically used to distribute the product to the final domestic and smaller commercial customers. The ice trade revolutionised the U.S. meat, vegetable and fruit industries, enabled significant growth in the fishing industry

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity concerned with taking, culturing, processing, preserving, storing, transporting, marketing or selling fish or fish products. It is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization as including ...

, and encouraged the introduction of a range of new drinks and foods. It only flourished in the time between the development of reliable transportation and the development of widespread mechanical refrigeration.

The trade was started by the New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

businessman Frederic Tudor in 1806. Tudor shipped ice to the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

island of Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label= Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

, hoping to sell it to wealthy members of the European elite there, using an ice house he had built specially for the purpose. Over the coming years the trade widened to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, with other merchants joining Tudor in harvesting and shipping ice from New England. During the 1830s and 1840s the ice trade expanded further, with shipments reaching England, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. Tudor made a fortune from the India trade, while brand names such as Wenham Ice became famous in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

.

Increasingly, however, the ice trade began to focus on supplying the growing cities on the east coast of the U.S. and the needs of businesses across the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. The citizens of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

became huge consumers of ice during their long, hot summers, and additional ice was harvested from the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

and Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

to fulfill the demand. Ice began to be used in refrigerator car

A refrigerator car (or "reefer") is a refrigerated boxcar (U.S.), a piece of railroad rolling stock designed to carry perishable freight at specific temperatures. Refrigerator cars differ from simple insulated boxcars and ventilated boxcars (co ...

s by the railroad industry, allowing the meat packing industry around Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

and Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

to slaughter cattle locally, before sending the dressed meat onward to either U.S. domestic or international markets. Chilled refrigerator cars and ships created a national industry in vegetables and fruit that could previously only have been consumed locally. U.S. and British fishermen began to preserve their catches in ice, allowing longer voyages and bigger catches, and the brewing industry became operational all-year round. As U.S. ice exports diminished after 1870, Norway became a major player in the international market, shipping large quantities of ice to England and Germany.

At its peak at the end of the 19th century, the U.S. ice trade employed an estimated 90,000 people in an industry capitalised at $28 million ($660 million in 2010 terms), using ice houses capable of storing up to 250,000 tons (220 million kg) each; Norway exported a million tons (910 million kg) of ice a year, drawing on a network of artificial lakes. Competition had slowly been growing, however, in the form of artificially produced plant ice and mechanically chilled facilities. Unreliable and expensive at first, plant ice began to successfully compete with natural ice in Australia and India during the 1850s and 1870s respectively, until, by the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in 1914, more plant ice was being produced in the U.S. each year than naturally harvested ice. Despite a temporary increase in production in the U.S. during the war, the inter-war years saw the total collapse of the international ice trade around the world. In some isolated rural areas without access to electricity, where plant ice was typically not economically viable and where natural ice was usually free of pollutants, ice continued to be harvested and sold at the local level until after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Today, ice is occasionally harvested for ice carving and ice festival {{short description, None

Ice Festival, Ice and Snow Festival, or Snow and Ice Festival may refer to one of the following events.

*Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival, China

*Sapporo Snow Festival, Japan

* World Ice Art Championsh ...

s, but little remains of the 19th-century industrial network of ice houses and transport facilities. At least one New Hampshire campground still harvests ice to keep cabins cool during the summer.

History

Pre-19th century methods

Prior to the emergence of the ice trade of the 19th century, snow and ice had been collected and stored to use in the summer months in various parts of the world, but never on a large scale. In the

Prior to the emergence of the ice trade of the 19th century, snow and ice had been collected and stored to use in the summer months in various parts of the world, but never on a large scale. In the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

and in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, for example, there was a long history of collecting ice from the upper slopes of the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

and the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

during the summer months and traders transporting this down into the cities. Similar trading practices had grown up in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

during the colonial period. Akkadian tablets from the late Bronze Age (circa. 1750 B.C.E.) attest to ice houses on the Euphrates River built for storing ice collected in winter from the snowy mountains for use in summer drinks. The Russians collected ice along the Neva River

The Neva (russian: Нева́, ) is a river in northwestern Russia flowing from Lake Ladoga through the western part of Leningrad Oblast (historical region of Ingria) to the Neva Bay of the Gulf of Finland. Despite its modest length of , it ...

during the winter months for consumption in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

for many years.Cummings, pp. 56–57. Wealthy Europeans began to build ice houses to store ice gathered on their local estates during the winter from the 16th century onwards; the ice was used to cool drinks or food for the wealthiest elites.

Some techniques were also invented to produce ice or chilled drinks through more artificial means. In India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, ice was imported from the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 10 ...

in the 17th century, but the expense of this meant that by the 19th century ice was instead manufactured in small quantities during the winter further south. Porous clay pots containing boiled, cooled water were laid out on top of straw in shallow trenches; under favourable circumstances, thin ice would form on the surface during winter nights which could be harvested and combined for sale.Herold, p. 163. There were production sites at Hugli-Chuchura

Hugli-Chuchura or Hooghly-Chinsurah is a city and a municipality of Hooghly district in the Indian state of West Bengal. It lies on the bank of Hooghly River, 35 km north of Kolkata. It is located in the district of Hooghly and is h ...

and Allahabad

Allahabad (), officially known as Prayagraj, also known as Ilahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi (Benares). It is the administra ...

, but this "hoogly ice" was only available in limited amounts and considered of poor quality because it often resembled soft slush rather than hard crystals. Saltpeter

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate Salt (chemistry), salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ...

and water were mixed together in India to cool drinks, taking advantage of local supplies of the chemical.Weightman, p. 104. In Europe, various chemical means for cooling drinks were created by the 19th century; these typically used sulphuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular for ...

to chill the liquid, but were not capable of producing actual ice.Weightman, p. 45.

Opening up the trade, 1800–30

The ice trade began in 1806 as the result of the efforts of Frederic Tudor, a

The ice trade began in 1806 as the result of the efforts of Frederic Tudor, a New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

entrepreneur, to export ice on a commercial basis. In New England, ice was an expensive product, consumed only by the wealthy who could afford their own ice houses. Nonetheless, icehouses were relatively common amongst the wealthier members of society by 1800, filled with ice cut, or harvested, from the frozen surface of ponds and streams on their local estates during the winter months. Around the neighbouring New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

area, the hot summers and rapidly growing economy had begun to increase local demand for ice towards the end of the 18th century, creating a small-scale market amongst farmers who sold ice from their ponds and streams to local city institutions and families. Some ships occasionally transported ice from New York and Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

for sale to the southern U.S. states, in particular Charleston in South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, laying it down as ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship ...

on the trip.Cummings, p. 6.

Tudor's plan was to export ice as a luxury good to wealthy members of West Indies and the southern US states, where he hoped they would relish the product during their sweltering summers; conscious of the risk that others might follow suit, Tudor hoped to acquire local monopoly rights in his new markets in order to maintain high prices and profits. He started by attempting to establish a monopoly on the potential ice trade in the Caribbean and invested in a brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

ship to transport ice bought from farmers around Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. At the time, Tudor was regarded by the business community at best as something of an eccentric, and at worst a fool.

The first shipments took place in 1806 when Tudor transported an initial trial cargo of ice, probably harvested from his family estate at Rockwood, to the Caribbean island of Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label= Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

. Sales were hampered, however, by the lack of local storage facilities, both for Tudor's stock and any ice bought by domestic customers, and as a result the ice stocks quickly melted away. Learning from this experience, Tudor then built a functioning ice depot in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

and, despite the U.S. trade embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they ...

declared in 1807, was trading successfully again by 1810. He was unable to acquire exclusive legal rights to import ice into Cuba, but was nonetheless able to maintain an effective monopoly through his control of the ice houses. The 1812 war briefly disrupted trade, but over subsequent years Tudor began to export fruit back from Havana to the mainland on the return journey, kept fresh with part of the unsold ice cargo. Trade to Charleston and to Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

followed, while Tudor's competitors began to supply South Carolina and Georgia by ship from New York or using barges sent downstream from Kentucky.

The price of the imported ice varied according to the amount of competition; in Havana, Tudor's ice sold for 25 cents ($3.70 in 2010 terms) per pound, while in Georgia it reached only six to eight cents ($0.90–$1.20 in 2010 terms). Where Tudor had a strong market share, he would respond to competition from passing traders by lowering his prices considerably, selling his ice at the unprofitable rate of one cent ($0.20) per pound (0.5 kg); at this price, competitors would typically be unable to sell their own stock at a profit: they would either be driven into debt or if they declined to sell, their ice would melt away in the heat. Tudor, relying on his local storage depots, could then increase his prices once again.Cummings, p. 15. By the middle of the 1820s, around 3,000 tons (3 million kg) of ice was being shipped from Boston annually, two thirds by Tudor.

At these lower prices, ice began to sell in considerable volumes, with the market moving beyond the wealthy elite to a wider range of consumers, to the point where supplies became overstretched. Ice was also being used by tradesmen to preserve perishable goods, rather than for direct consumption. Tudor looked beyond his existing suppliers to Maine and even to harvesting from passing

The price of the imported ice varied according to the amount of competition; in Havana, Tudor's ice sold for 25 cents ($3.70 in 2010 terms) per pound, while in Georgia it reached only six to eight cents ($0.90–$1.20 in 2010 terms). Where Tudor had a strong market share, he would respond to competition from passing traders by lowering his prices considerably, selling his ice at the unprofitable rate of one cent ($0.20) per pound (0.5 kg); at this price, competitors would typically be unable to sell their own stock at a profit: they would either be driven into debt or if they declined to sell, their ice would melt away in the heat. Tudor, relying on his local storage depots, could then increase his prices once again.Cummings, p. 15. By the middle of the 1820s, around 3,000 tons (3 million kg) of ice was being shipped from Boston annually, two thirds by Tudor.

At these lower prices, ice began to sell in considerable volumes, with the market moving beyond the wealthy elite to a wider range of consumers, to the point where supplies became overstretched. Ice was also being used by tradesmen to preserve perishable goods, rather than for direct consumption. Tudor looked beyond his existing suppliers to Maine and even to harvesting from passing iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

s, but neither source proved practical. Instead, Tudor teamed up with Nathaniel Wyeth to take advantage of the ice supplies of Boston on an industrial scale. Wyeth created a new form of horse-pulled ice-cutter in 1825 that cut square blocks of ice more efficiently than previous methods. He agreed to supply Tudor from Fresh Pond in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, reducing the cost of harvesting ice from 30 cents ($7.30) a ton (901 kg) to only 10 cents ($2.40). Sawdust to insulate the ice was brought from Maine, at $16,000 ($390,000) a year.

Expansion, 1830–50

The trade in New England ice expanded during the 1830s and 1840s across the eastern coast of the U.S., while new trade routes were created across the world. The first and most profitable of these new routes was to India: in 1833 Tudor combined with the businessmen Samuel Austin and William Rogers to attempt to export ice to

The trade in New England ice expanded during the 1830s and 1840s across the eastern coast of the U.S., while new trade routes were created across the world. The first and most profitable of these new routes was to India: in 1833 Tudor combined with the businessmen Samuel Austin and William Rogers to attempt to export ice to Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

using the brigantine ship the ''Tuscany''. The Anglo-Indian elite, concerned about the effects of the summer heat, quickly agreed to exempt the imports from the usual East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

regulations and trade tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

s, and the initial net shipment of around a hundred tons (90,000 kg) sold successfully. With the ice selling for three pence (£0.80 in 2010 terms) per pound (0.45 kg), the first shipment aboard the ''Tuscany'' produced profits of $9,900 ($253,000), and in 1835 Tudor commenced regular exports to Calcutta, Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

, and Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

.

Tudor's competitors soon entered the market as well, shipping ice by sea to both Calcutta and Bombay, further increasing competition there and driving out most of the indigenous ice dealers. A grand ice house was built from stone in Calcutta by the local British community to store the ice imports. Small shipments of chilled fruit and dairy products began to be sent out with the ice, bringing high prices. Attempts were made by Italian traders to introduce ice from the Alps into Calcutta, but Tudor repeated his monopolistic techniques from the Caribbean, driving them and many others out of the market. Calcutta remained a particularly profitable market for ice for many years; Tudor alone made more than $220,000 ($4,700,000) in profits between 1833 and 1850.

Other new markets were to follow. In 1834 Tudor sent shipments of ice to Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

along with chilled apples, beginning the ice trade with Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

. These ships typically returned to North America carrying cargoes of sugar, fruit and, later, cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

. Ice from traders in New England reached Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

, Australia, in 1839, initially selling at three pence (£0.70) per pound (0.5 kg), later rising to six pence (£1.40).Isaacs, p. 26. This trade was to prove less regular, and the next shipments arrived in the 1840s. The export of chilled vegetables, fish, butter, and eggs to the Caribbean and to markets in the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

grew during the 1840s, with as many as 35 barrels being transported on a single ship, alongside a cargo of ice. Shipments of New England ice were sent as far as Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

, South-East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

and Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

.

New England businessmen also tried to establish a market for ice in England during the 1840s. An abortive first attempt to export ice to England had occurred in 1822 under William Leftwich; he had imported ice from

New England businessmen also tried to establish a market for ice in England during the 1840s. An abortive first attempt to export ice to England had occurred in 1822 under William Leftwich; he had imported ice from Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

, but his cargo had melted before reaching London. Fresh attempts were made by Jacob Hittinger, who owned supplies at Fresh Pond, and Eric Landor, with assets at Wenham Lake

Wenham Lake is a 224-acre body of water located in Wenham and Beverly towns, Essex County, Massachusetts.The lake receives water from the water table and also from a system of streams. In the 19th century, the lake was an important source of ic ...

, in 1842 and 1844 respectively. Of the two, Landor's venture was more successful and he formed the Wenham Lake Ice Company to export to Britain, building an ice depot on the Strand. Wenham ice was marketed as being unusually pure, possessed of special cooling properties, successfully convincing British customers to avoid local British ice, which was condemned as polluted and unhealthy. After some initial success, the venture eventually failed, in part because the English chose not to adopt chilled drinks in the same way as North Americans, but also because of the long distances involved in the trade and the consequent costs of ice wastage through melting. Nonetheless, the trade allowed for some refrigerated goods to arrive in England from America along with ice cargoes during the 1840s.

The east coast of the U.S. also began to consume more ice, particularly as more industrial and private customers found uses for refrigeration. Ice became increasingly used in the northeast of the U.S. to preserve dairy products and fresh fruit for market, the chilled goods being transported over the growing railroad lines.Cummings, p. 33. By the 1840s, ice was being used to transfer small quantities of goods further west across the continent. Eastern U.S. fishermen began to use ice to preserve their catches. Fewer businesses or individuals in the east harvested their own ice independently in winter, most preferring to rely on commercial providers.

With this growth in commerce, Tudor's initial monopoly on the trade broke down, but he continued to make significant profits from the growing trade. Increased supplies of ice were also needed to keep up with demand. From 1842 onwards, Tudor and others invested at Walden Pond in New England for additional supplies.Cummings, p. 46. New companies began to spring up, such as the Philadelphia Ice Company, which made use of the new railroad lines to transport harvested ice, while the Kershow family introduced improved ice harvesting to the New York region.

Growth westwards, 1850–60

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

and Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

, in California, including a shipment of refrigerated apples. The market was proved, but shipping ice in this way was expensive and demand outstripped supply.Keithahn, p. 121. Ice began to be ordered instead from the then Russian-controlled Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

in 1851 at $75 a ton (901 kg). The American-Russian Commercial Company was subsequently formed in San Francisco in 1853 to work in partnership with the Russian-American Company of Alaska to supply ice to the west coast of America. The Russian company trained Aleutian teams to harvest ice in Alaska, built sawmills to produce insulating sawdust and shipped the ice south along with supplies of chilled fish. The costs of this operation remained high, and M. Tallman founded the rival Nevada Ice Company, which harvested ice on Pilot Creek and transported to Sacramento, bringing the west coast price for ice down to seven cents ($2) a pound (0.5 kg).

The U.S. was expanding westwards, and, in Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

, Hiram Joy began to exploit Crystal Lake Crystal Lake or Crystal Lakes may refer to:

Lakes

Canada

* Crystal Lake (Saskatchewan)

* Crystal Lake (Ontario), drain into the Lynn River, which drains into Lake Erie

United States

* Crystal Lake, California, a mountain lake in Nevada Co ...

, near Chicago, which was soon linked to the city by the Chicago, St Paul and Fond du Lac Railroad.Cummings, p. 58. The ice was used to allow goods to be brought to market. Cincinnati and Chicago began to use ice to help the packing of pork in the summer; John L. Schooley developing the first refrigerated packing room. Fruit began to be stored in central Illinois using refrigerators, for consumption in later seasons.Cummings, p. 61. By the 1860s, ice was being used to allow the brewing of the increasingly popular lager beer

Lager () is beer which has been brewed and conditioned at low temperature. Lagers can be pale, amber, or dark. Pale lager is the most widely consumed and commercially available style of beer. The term "lager" comes from the German for "storag ...

all year round. Improved railroad links helped the growth in business across the region and to the east.

Meanwhile, it had been known since 1748 that it was possible to artificially chill water with mechanical equipment, and attempts were made in the late 1850s to produce artificial ice on a commercial scale. Various methods had been invented to do this, including Jacob Perkins's

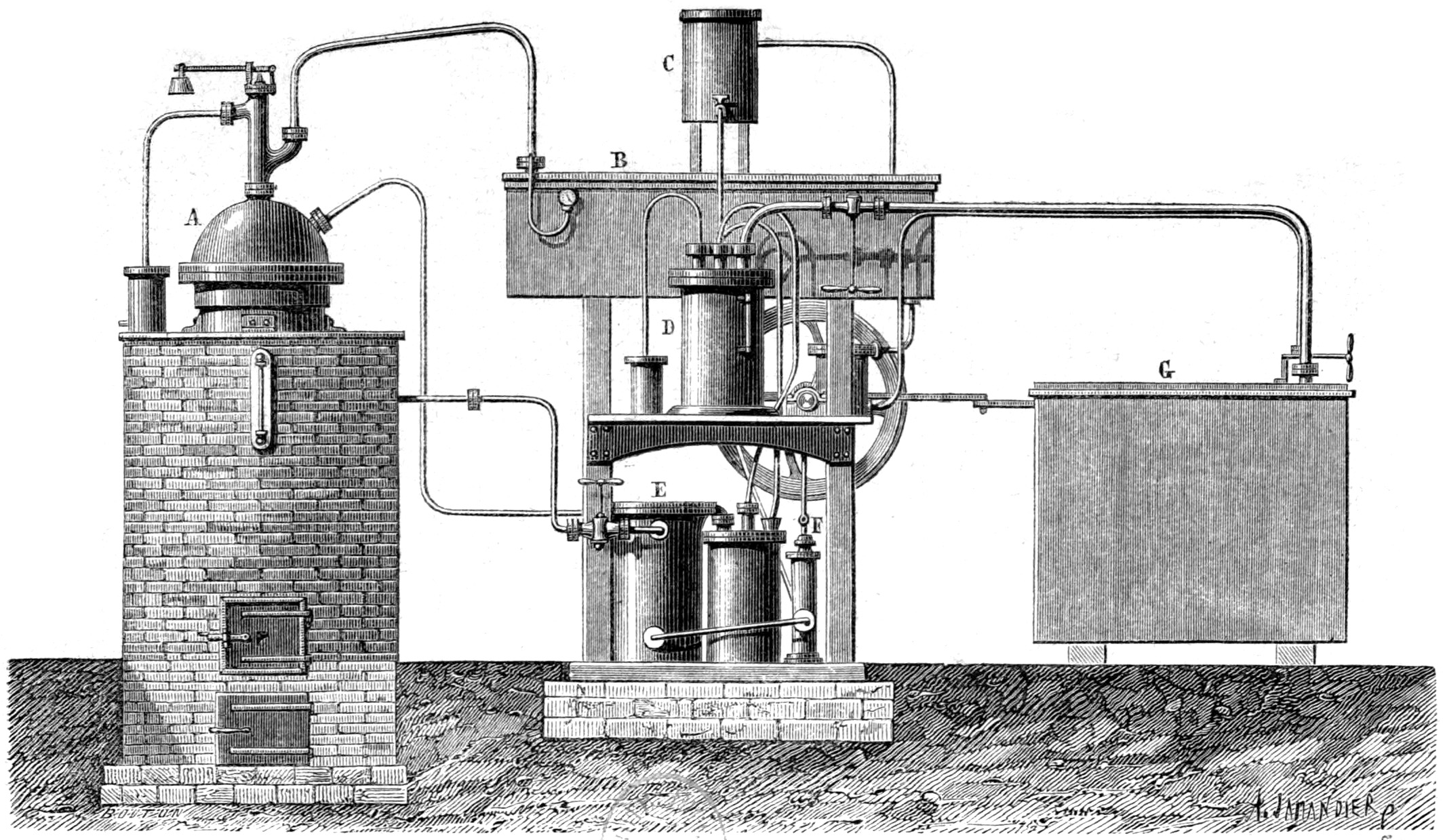

Meanwhile, it had been known since 1748 that it was possible to artificially chill water with mechanical equipment, and attempts were made in the late 1850s to produce artificial ice on a commercial scale. Various methods had been invented to do this, including Jacob Perkins's diethyl ether

Diethyl ether, or simply ether, is an organic compound in the ether class with the formula , sometimes abbreviated as (see Pseudoelement symbols). It is a colourless, highly volatile, sweet-smelling ("ethereal odour"), extremely flammable li ...

vapor-compression refrigeration engine, invented in 1834; engines that used pre-compressed air; John Gorrie's air cycle engines; and ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous ...

-based approaches such as those championed by Ferdinand Carré

Ferdinand Philippe Edouard Carré (11 March 1824 – 11 January 1900) was a French engineer, born at Moislains (Somme) on 11 March 1824. Carré is best known as the inventor of refrigeration equipment used to produce ice. He died on 11 January 19 ...

and Charles Tellier

Charles Tellier (29 June 1828 – 19 October 1913) was a French engineer, born in Amiens. He early made a study of motors and compressed air. In 1868, he began experiments in refrigeration, which resulted ultimately in the refrigerating plant, a ...

. The resulting product was variously called plant or artificial ice, but there were numerous obstacles to manufacturing it commercially. Producing plant ice required large amounts of fuel, in the form of coal, and capital for machinery, so producing ice at a competitive price was challenging.Weightman, p. 177. The early technology was unreliable, and for many decades ice plants faced the risk of explosions and consequent damage to the surrounding buildings. Ammonia-based approaches potentially left hazardous ammonia in the ice, into which it had leaked through the joints of machinery. For most of the 19th century, plant ice was not as clear as much natural ice, sometimes left white residue when it melted and was generally regarded as less suitable for human consumption than the natural product.

Nonetheless, Alexander Twining

Alexander Catlin Twining (July 5, 1801 – November 22, 1884) was an American scientist and inventor.

Twining, the son of Stephen Twining and Almira (Catlin) Twining, was born in New Haven, Connecticut, July 5, 1801. He graduated from Yale Col ...

and James Harrison set up ice plants in Ohio and Melbourne respectively during the 1850s, both using Perkins engines. Twining found he could not compete with natural ice, but in Melbourne Harrison's plant came to dominate the market. Australia's distance from New England, where journeys could take 115 days, and the consequent high level of wastage – 150 tons of the first 400-ton shipment to Sydney melted en route – made it relatively easy for plant ice to compete with the natural product. Elsewhere, however, natural ice dominated the entire market.

Expansion and competition, 1860–80

The international ice trade continued through the second half of the 19th century, but it increasingly moved away from its former, New England roots. Indeed, ice exports from the US peaked around 1870, when 65,802 tons (59,288,000 kg), worth $267,702 ($4,610,000 in 2010 terms), were shipped out from the ports. One factor in this was the slow spread of plant ice into India. Exports from New England to India peaked in 1856, when 146,000 tons (132 million kg) were shipped, and the Indian natural ice market faltered during the

The international ice trade continued through the second half of the 19th century, but it increasingly moved away from its former, New England roots. Indeed, ice exports from the US peaked around 1870, when 65,802 tons (59,288,000 kg), worth $267,702 ($4,610,000 in 2010 terms), were shipped out from the ports. One factor in this was the slow spread of plant ice into India. Exports from New England to India peaked in 1856, when 146,000 tons (132 million kg) were shipped, and the Indian natural ice market faltered during the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

, dipped again during the American Civil War, and imports of ice slowly declined through the 1860s. Spurred on by the introduction of artificial ice plants around the world by the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, the International Ice Company was founded in Madras in 1874 and the Bengal Ice Company in 1878. Operating together as the Calcutta Ice Association, they rapidly drove natural ice out of the market.

An ice trade also developed in Europe. By the 1870s hundreds of men were employed to cut ice from the glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

s at Grindelwald

, neighboring_municipalities = Brienz, Brienzwiler, Fieschertal (VS), Guttannen, Innertkirchen, Iseltwald, Lauterbrunnen, Lütschental, Meiringen, Schattenhalb

, twintowns = Azumi, now Matsumoto (Japan)

Grindelwald is a village and ...

in Switzerland, and Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in France began to import ice from the rest of Europe in 1869.Maw and Dredge, p. 76. Meanwhile, Norway entered the international ice trade, focusing on exports to England. The first shipments from Norway to England had occurred in 1822, but larger-scale exports did not occur until the 1850s.Ouren, p. 31. The ice harvesting was initially centred on the fjords of the west coast, but poor local transport links pushed the trade south and east to the main centres of the Norwegian timber and shipping industries, both essential for ice exporting. In the early 1860s, Lake Oppegård in Norway was renamed "Wenham Lake" with the aim of confusing the product with New England exports, and exports to England increased.Blain, p. 9. Initially these were run by British business interests, but eventually transitioned to Norwegian companies. Distribution of the Norwegian ice across Britain was helped by the growing railway networks, while the railway connection built between the fishing port of Grimsby

Grimsby or Great Grimsby is a port town and the administrative centre of North East Lincolnshire, Lincolnshire, England. Grimsby adjoins the town of Cleethorpes directly to the south-east forming a conurbation. Grimsby is north-east of L ...

and London in 1853 created a demand for ice to allow the transport of fresh fish to the capital.

The eastern market for ice in the U.S. was also changing. Cities like New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia saw their population boom in the second half of the century; New York tripled in size between 1850 and 1890, for example.Parker, p. 2. This drove up the demand for ice considerably across the region. By 1879, householders in the eastern cities were consuming two thirds of a ton (601 kg) of ice a year, being charged 40 cents ($9.30) per 100 pounds (45 kg); 1,500 wagons were needed just to deliver ice to consumers in New York.

In supplying this demand, the ice trade increasingly shifted north, away from Massachusetts and towards Maine. Various factors contributed to this. New Englands' winters became warmer during the 19th century, while industrialisation resulted in more of the natural ponds and rivers becoming contaminated. Less trade was brought through New England as other ways of reaching western US markets were opened up, making it less profitable to trade ice from Boston, while the cost of producing ships in the region increased due to deforestation.Dickason, p. 81. Finally, in 1860 there was the first of four ice famines along the Hudson-warm winters that prevented the formation of ice in New England-creating shortages and driving up prices.

The outbreak of the

The eastern market for ice in the U.S. was also changing. Cities like New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia saw their population boom in the second half of the century; New York tripled in size between 1850 and 1890, for example.Parker, p. 2. This drove up the demand for ice considerably across the region. By 1879, householders in the eastern cities were consuming two thirds of a ton (601 kg) of ice a year, being charged 40 cents ($9.30) per 100 pounds (45 kg); 1,500 wagons were needed just to deliver ice to consumers in New York.

In supplying this demand, the ice trade increasingly shifted north, away from Massachusetts and towards Maine. Various factors contributed to this. New Englands' winters became warmer during the 19th century, while industrialisation resulted in more of the natural ponds and rivers becoming contaminated. Less trade was brought through New England as other ways of reaching western US markets were opened up, making it less profitable to trade ice from Boston, while the cost of producing ships in the region increased due to deforestation.Dickason, p. 81. Finally, in 1860 there was the first of four ice famines along the Hudson-warm winters that prevented the formation of ice in New England-creating shortages and driving up prices.

The outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

in 1861 between the Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a r ...

and Southern