host switch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

A pathogen undergoing a host switch is driven by selection pressures to acquire the necessary changes allowing for survival and transmission in the new host species. According to a 2008 Microbiology and Molecular Biology Review, this process of host switching can be defined by three stages:

*Isolated infection

:-An isolated infection of a new host with no further infection within the new species

:-Spillovers into dead-end hosts

*Local spillovers

:-Spillover events that cause small chains of local transmission

*

A pathogen undergoing a host switch is driven by selection pressures to acquire the necessary changes allowing for survival and transmission in the new host species. According to a 2008 Microbiology and Molecular Biology Review, this process of host switching can be defined by three stages:

*Isolated infection

:-An isolated infection of a new host with no further infection within the new species

:-Spillovers into dead-end hosts

*Local spillovers

:-Spillover events that cause small chains of local transmission

*

parasitology

Parasitology is the study of parasites, their host (biology), hosts, and the relationship between them. As a List of biology disciplines, biological discipline, the scope of parasitology is not determined by the organism or environment in questio ...

and epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions and evi ...

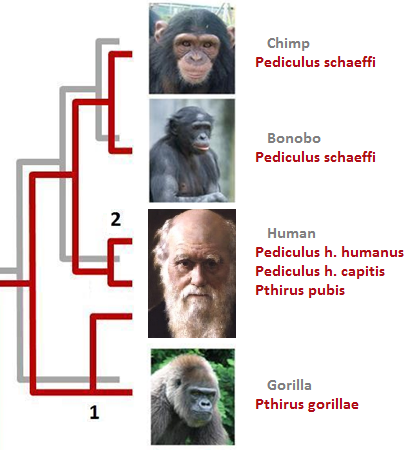

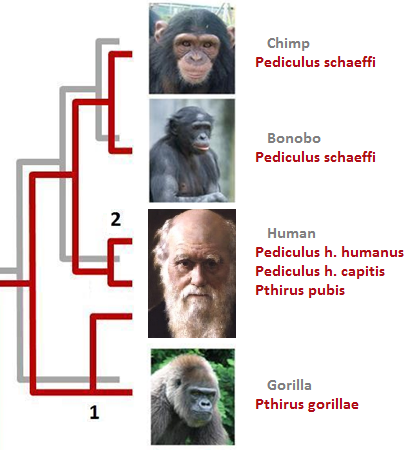

, a host switch (or host shift) is an evolutionary change of the host specificity of a parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson h ...

or pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a g ...

. For example, the human immunodeficiency virus

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of ''Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immun ...

used to infect and circulate in non-human primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians ( monkeys and apes, the latter includin ...

s in West-central Africa, but switched to humans in the early 20th century.

All symbiotic

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or para ...

species, such as parasites, pathogens and mutualists

Mutualism describes the ecological Biological interaction, interaction between two or more species where each species has a net benefit. Mutualism is a common type of ecological interaction. Prominent examples include most vascular plants engag ...

, exhibit a certain degree of host specificity. This means that pathogens are highly adapted to infect a specific host - in terms of but not limited to receptor binding, countermeasures for host restriction factors and transmission methods. They occur in the body (or on the body surface) of a single host species or – more often – on a limited set of host species. In the latter case, the suitable host species tend to be taxonomically related, sharing similar morphology and physiology.

Speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution withi ...

is the creation of a new and distinct species through evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

and so unique differences exist between all life on earth. It goes without saying that dogs and birds are very different classes of animals – for one, dogs have fur coats and birds have feathers and wings. We therefore know that their fundamental biological makeup is as different as their physical appearance, this ranges from their internal cellular mechanisms to their response to infection, and so species-specific pathogens must overcome multiple host range barriers in order for their new host to support their infection.

Types of host switching

Recent studies have proposed to discriminate between two different types of evolutionary change in host specificity. According to this view, host switch can be a sudden and accidental colonization of a new host species by a few parasite individuals capable of establishing a new and viable population there. After a switch of this type, the new population is more-or-less isolated from the population on the donor host species. The new population does not affect the further fate of the conspecific parasites on the donor host, and may finally lead to parasite speciation. This type of switch is more likely to target an increasing host population that harbours a relatively poor parasite/pathogen fauna, such as the pioneer populations of invasive species. The switch of HIV to the human host is of this type. Alternatively, in the case of a multi-host parasite host-shift may occur as a gradual change of the relative role of one host species, which becomes primary rather than secondary host. The former primary host slowly becomes a secondary host, or may even, eventually, be totally abandoned. This process is slower and more predictable, and does not increase parasite diversity. It will typically occur in a shrinking host population harbouring a parasite/pathogen fauna which is relatively rich for the host population size.Host switching features

Reason for host switch events

All diseases have an origin. Some disease circulate in human populations and are already known to epidemiologists, but evolution of the disease can result in a new strain of this disease emerging that makes it stronger - for example, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. In other cases, diseases can be discovered that have not previously been observed or studied. These can emerge due to host switch events allowing the pathogen to evolve to become human-adapted and are only discovered due to an infection outbreak. A pathogen that switches host emerges as a new form of the virus capable of circulating within a new population. Diseases that emerge in this sense can occur more often through human over exposure to the wildlife. This can be as a result ofurbanisation

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly the ...

, deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated ...

, destruction of wildlife habitats and changes to agricultural

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peopl ...

practise. The more exposure humans have to the wild, the more spillover infections occur and pathogens are exposed to human-specific selection pressures

Any cause that reduces or increases reproductive success in a portion of a population potentially exerts evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of ...

. The pathogen is therefore driven towards specific-specific adaptation and is more likely to gain the necessary mutations to jump the species barrier and become human-infective.

Host switch and pathogenicity

The problem with diseases emerging in new species is that the host population will be immunologically naïve. This means that the host has never been previously exposed to the pathogen and has no pre-existingantibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of ...

or protection from the infection. This make host switching dangerous and can result in more pathogenic infections. The pathogen is not adapted to surviving in this new host and this imbalance of coevolution

In biology, coevolution occurs when two or more species reciprocally affect each other's evolution through the process of natural selection. The term sometimes is used for two traits in the same species affecting each other's evolution, as well ...

ary history may result in aggressive infections. However, this balance must be brought under control for the pathogen to maintain its infection in the new host and not burn through the population.

Stages of host switch

A pathogen undergoing a host switch is driven by selection pressures to acquire the necessary changes allowing for survival and transmission in the new host species. According to a 2008 Microbiology and Molecular Biology Review, this process of host switching can be defined by three stages:

*Isolated infection

:-An isolated infection of a new host with no further infection within the new species

:-Spillovers into dead-end hosts

*Local spillovers

:-Spillover events that cause small chains of local transmission

*

A pathogen undergoing a host switch is driven by selection pressures to acquire the necessary changes allowing for survival and transmission in the new host species. According to a 2008 Microbiology and Molecular Biology Review, this process of host switching can be defined by three stages:

*Isolated infection

:-An isolated infection of a new host with no further infection within the new species

:-Spillovers into dead-end hosts

*Local spillovers

:-Spillover events that cause small chains of local transmission

*Epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious ...

:-Sustained epidemic transmission of the pathogen within the new host species

*Pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic disease with a stable number of in ...

:-Global spread of the disease infection

Exposure to new environments and host species is what allows pathogens to evolve. The early isolated infection events exposes the pathogen to the selection pressure of survival in that new species of which some will eventually adapt to. This gives raise to pathogens with the primary adaptations allowing the smaller outbreaks within this potential new host, increasing exposure and driving further evolution. This gives rise to complete host adaptation and the capability for a larger epidemic and the pathogen can sustainably survive in its new host – i.e. host switch. Sufficiently adapted pathogens may also reach pandemic status meaning the disease has infected the whole country or spread around the world.

Zoonosis and spillover

Azoonosis

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from a non-human (usually a vertebrate) to a human. ...

is a specific kind of cross-species infection in which diseases are transmitted from vertebrate animals to humans. An important feature of a zoonotic disease is they originate from animal reservoirs which are essential to the survival of zoonotic pathogens. They naturally exist in animal populations asymptomatically - or causing mild disease - making it challenging to find the natural host ( disease reservoir) and impossible to eradicate as the virus will always continue to live in wild animal species.

Those zoonotic pathogens that permanently make the jump from vertebrate animals to human populations have performed a host switch and thus can continue to survive as they are adapted to transmission in human populations. However, not all zoonotic infections complete the host switch and only exist as smaller isolated events. These are known as spillovers. This means that humans can become infected from an animal pathogen, but it does not necessarily take hold and become a human transmitted disease that circulates in human populations. This is because the host switch adaptations required to make the pathogen sustainable and transmissible in the new host does not occur.

Some cross-species transmission

Cross-species transmission (CST), also called interspecies transmission, host jump, or spillover, is the transmission of an infectious pathogen, such as a virus, between hosts belonging to different species. Once introduced into an individual of a ...

events are important as they can show that a pathogen is getting closer to epidemic/pandemic potential. Small epidemics show that the pathogen is getting more adapted to human transmission and gaining stability to exist in the human population. However, there are some pathogens that do not possess this ability to spread between humans. This is the case for spillover events such as rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, ...

. Humans infected from the bite of rabid animals do not tend to pass on the disease and so are classed as dead-end hosts.

An extensive list of zoonotic infections can be found at Zoonosis

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from a non-human (usually a vertebrate) to a human. ...

.

Case studies

The following pathogens are examples of diseases that have crossed the species barrier into the human population and highlight the complexity of the switch.Influenza

Influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

- also known as the flu - is one of the most well-known viruses that continues to pose a huge burden on today's health care systems and is the most common cause of human respiratory infections. Influenza is an example of how a virus can continuously jump the species barrier in multiple isolated instances over time creating different human infecting strains circulating our populations - for example, H1N1

In virology, influenza A virus subtype H1N1 (A/H1N1) is a subtype of influenza A virus. Major outbreaks of H1N1 strains in humans include the Spanish flu, the 1977 Russian flu pandemic and the 2009 swine flu pandemic. It is an orthomyxoviru ...

, H5N1

Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 (A/H5N1) is a subtype of the influenza A virus which can cause illness in humans and many other animal species. A bird-adapted strain of H5N1, called HPAI A(H5N1) for highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of type ...

and H7N9. These host switch events create pandemic strains that eventually transition into seasonal flu

Flu season is an annually recurring time period characterized by the prevalence of an outbreak of influenza (flu). The season occurs during the cold half of the year in each hemisphere. It takes approximately two days to show symptoms. Influen ...

that annually circulates in the human population in colder months.

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) are classified by two defining proteins. These proteins are present in all influenza viral strains but small differences allow for differentiation of new strains. These identifiers are:

* hemagglutinin

In molecular biology, hemagglutinins (or ''haemagglutinin'' in British English) (from the Greek , 'blood' + Latin , 'glue') are receptor-binding membrane fusion glycoproteins produced by viruses in the '' Paramyxoviridae'' family. Hemagglutinins a ...

(HA)

* neuraminidase

Exo-α-sialidase (EC 3.2.1.18, sialidase, neuraminidase; systematic name acetylneuraminyl hydrolase) is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

: Hydrolysis of α-(2→3)-, α-(2→6)-, α-(2→8)- glyc ...

(NA)

IAVs naturally exist in wild birds without causing disease or symptoms. These birds, especially waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which ...

and shore birds, are the reservoir host of the majority of IAVs with these HA and NA protein antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune respon ...

s. From these animals, the virus spills into other species (e.g. pigs, humans, dogs ) creating smaller scale infections until the virus has acquired significant mutations to spread and maintain itself in another species. The RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens th ...

enzyme of influenza has low level accuracy due to a lack of a proofreading mechanism and therefore has a high error rate in terms of genetic replication. Because of this, influenza has the capacity to mutate frequently dependent of the current selection pressures and has the capability to adapt to surviving in different host species.

Transmission and infection methods

Comparing IAVs in birds and humans, one of the main barriers to host switching is the type of cells the virus can recognise and bind to (celltropism

A tropism is a biological phenomenon, indicating growth or turning movement of a biological organism, usually a plant, in response to an environmental stimulus. In tropisms, this response is dependent on the direction of the stimulus (as oppos ...

) in order to initiate infection and viral replication. An avian influenza

Avian influenza, known informally as avian flu or bird flu, is a variety of influenza caused by viruses adapted to birds.

virus is adapted to binding to the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

of birds. In bird populations, the virus is shed from the excretory system

The excretory system is a passive biological system that removes excess, unnecessary materials from the body fluids of an organism, so as to help maintain internal chemical homeostasis and prevent damage to the body. The dual function of excreto ...

into the water and ingested by other birds to colonise their guts. This is not the case in humans as influenza, in this species, produces a respiratory infection. The virus here binds to respiratory tissue and is transmitted through breathing, talking and coughing, therefore the virus has to adapt in order to switch to the human host from avian populations. Additionally, the respiratory tract is mildly acidic and so the virus must also mutate to overcome these conditions in order to successfully colonise mammalian lungs and respiratory tracts. Acidic conditions are a trigger for viral uncoating as it is normally a sign the virus has penetrated a cell, however premature uncoating will result in virus exposure to the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

leading killing of the virus.

Molecular adaptations

=Host receptor binding

= IAVs binds to host cells using the HA protein. These proteins recognisesialic acid Sialic acids are a class of alpha-keto acid sugars with a nine-carbon backbone.

The term "sialic acid" (from the Greek for saliva, - ''síalon'') was first introduced by Swedish biochemist Gunnar Blix in 1952. The most common member of this ...

that reside on the terminal regions of external glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glyco ...

s on host cell membranes. However, HA proteins have different specificities for isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

Is ...

s of sialic acid depending on which species the IAV is adapted for. IAVs adapted for birds recognise α2-3 sialic acid isomers whereas human adapted IAV HAs bind to α2-6 isomers. These are the isomers of sialic acid mostly present in the regions of the host that each IAVs infected respectively - i.e. the gastrointestinal tract of birds and the respiratory tract of humans. Therefore, in order to commit to a host switch, the HA specificity must mutate to the substrate receptors of the new host.

In the final stages of infection, the HA proteins are cleaved to activate the virus. Certain hemagglutinin subtypes (H5 and H7) have the capacity to obtain additional mutations. These exist at the HA activation cleavage site which changes the HA specificity. This results in a broadening of the range of protease enzymes that can bind to and activate the virus. Therefore, this makes the virus more pathogenic and can make IAV infections more aggressive.

=Polymerase action

= Successfully binding to different host tissue is not the only requirement of host switch for influenza A. The influenzagenome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

is replicated using the virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to ...

but it must adapt to use host specific cofactors in order to function. The polyermase is a heterotrimeric complex and consists of 3 major domains: PB1, PB2 and PA. Each plays their own role in replication of the viral genome but PB2 is an important factor in the host range barrier as it interacts with host cap proteins. Specifically, residue 627 of the PB2 unit shows to play a defining role in the host switch from avian to human adapted influenza strains. In IAVs, the residue at position 627 is glutamic acid (E) whereas in mammal infecting influenza, this residue is mutated to lysine (K). Therefore, the virus must undergo a E627K mutation in order to perform a mammalian host switch. This region surrounding residue 627 forms a cluster protruding from the enzyme core. With lysine, this PB2 surface region can form a basic patch enabling host cofactor interaction, whereas the glutamic acid residue found in IAVs disrupt this basic region and subsequent interactions.

=Host cofactor

= The cellular proteinANP32A

Acidic leucine-rich nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family member A is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''ANP32A'' gene. It is one of the targets of an oncomiR, MIRN21.

Interactions

Acidic leucine-rich nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family member ...

has been shown to account for contrasting levels of avian influenza interaction efficiency with different host species. The key difference between ANP32A is that the avian form contains an additional 33 amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s than the mammalian form. When mammals cells are infected with avian IAVs, the polymerase enzyme efficiency is sub-optimal as the avian virus is not adapted to surviving in mammalian cells. However, when that mammalian cell contains the avian ANP32A protein, viral replication is mostly restored, showing that the ANP32A is likely to positively interact and optimise the polymerase action. Mutations in the PB2 making the influenza mammal-adapted allow for the interaction between the viral polymerase and the mammalian ANP32A protein and therefore essential for the host switch.

Summary

There are many factor that determine a successful influenza host switch from avian to a mammalian host: *Stability in the mildly acidic mammalian respiratory tract *Recognition of mammalian sialic acid by HA receptors *PB2 E627K mutation in the viral polymerase to allow for interaction with mammalian ANP32A for optimal viral replication Each factor has a role to play and so the virus must acquire them all in order to undergo the host switch. This is a complex process and requires time for the virus to sufficiently adapt and mutate. Once each mutation has been achieved, the virus can infect human populations and has the potential to reach pandemic levels. However, this is dependent on virulence and rate of transmission and host switching will change these parameters of viral infection.HIV

HIV is thehuman immunodeficiency virus

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of ''Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immun ...

and attacks cells of the immune system depleting the body's defence against incoming pathogens. In particular, HIV infects CD4+ T helper lymphocytes, a cell involved in the organisation and coordination of the immune response. This means that the body can recognise incoming pathogens but cannot trigger their defences against them. When HIV sufficiently diminishes the immune system, it causes a condition known as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ma ...

characterised by severe weight loss, fever, swollen lymph nodes

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that includ ...

and susceptibility to other severe infections

HIV is a type of lentivirus

''Lentivirus'' is a genus of retroviruses that cause chronic and deadly diseases characterized by long incubation periods, in humans and other mammalian species. The genus includes the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS. L ...

of which two types are known to cause AIDS: HIV-1 and HIV-2, both of which jumped into the human population from numerous cross-species transmission events by the equivalent disease in primates known as simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). SIVs are found in many different primate species, including chimpanzees and mandrills found in sub-Saharan Africa, and for the most part are largely non pathogenic HIV-1 and HIV-2 having similar features but are antigenically different and so are classed as different types of HIV. Most transmission events are unsuccessful in switching its host, however in the context of HIV-1, four distinct forms emerged categorised as groups M, N, O and P of which group M is associated with pandemic HIV-1 and accounts for the majority of global cases. Each type is proposed to have emerged through bush-meat hunting and the exposure to the body fluids of infected primates, including blood.

Host specific adaptations

=Gag-30

= Host-specific selection pressures would bring about a change in the viralproteome

The proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. ...

of HIVs to suit the new host and therefore these regions would not be conserved when compared to SIVs. Through these viral proteomic comparisons, the viral matrix protein Gag-30 was identified as having differing amino acids at position 30. This amino acid is conserved as a methionine in SIVs but mutated to an arginine or lysine in HIV-1 groups M, N and O, suggesting a strong selection pressure in the new host. This observation was supported by other data including the fact that this mutation was reversed when HIV-1 was used to infect primates meaning that the arginine or lysine converted back to the methionine originally observed in SIVs. This reinforces the idea of the strong, opposing host-specific selection pressure between humans and primates. Additionally, it was observed that methionine containing viruses replicated more efficiently in primates and arginine/lysine containing viruses in humans. This is evidence of the reason behind the mutation (optimal levels of replication in host CD4+ T lymphocytes), however the exact function and action of the position 30 amino acid is unknown.

=Tetherin countermeasures

=Tetherin

Tetherin, also known as bone marrow stromal antigen 2, is a lipid raft associated protein that in humans is encoded by the ''BST2'' gene. In addition, tetherin has been designated as CD317 (cluster of differentiation 317). This protein is consti ...

is a defence protein in the innate immune response

The innate, or nonspecific, immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies (the other being the adaptive immune system) in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an older evolutionary defense strategy, relatively speaking, and is the ...

whose production is activation by interferon

Interferons (IFNs, ) are a group of signaling proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of several viruses. In a typical scenario, a virus-infected cell will release interferons causing nearby cells to heighten th ...

. Tetherin specifically inhibits the infective capabilities of HIV-1 by blocking its release from the cells it infects. This prevents the virus from leaving to infect more cells and halts the progression of the infection giving the host defences time to destroy the viral-infected cells. Adapted viruses tend to have countermeasures to defend themselves against tetherin normally through degradation through specific regions of the protein. These anti-tetherin techniques are different between SIVs and HIV-1 showing that tetherin interaction is a host range restriction that must be overcome to enable a primate-human host switch. SIVs use the Nef protein to remove tetherin from the cell membrane whereas HIV-1 uses the Vpu protein degrade the defence protein.

Tetherin is a conserved viral-defence mechanism across species but its exact sequence and structure shows some differences. The regions making up tetherin include the cytoplasmic region, transmembrane region, a coiled-coiled extracellular domain and a GPI anchor; however, human tetherin defers to other primates by having a deletion in the cytoplasmic region. This incomplete cytoplasmic domain renders Nef proteins found in SIVs ineffective as an anti-tetherin response in humans and so in order to switch from non-human primates to a human host, the SIV must activate the Vpu protein which instead blocks tetherin through interaction with the conserved transmembrane region.

Summary

The two factors that are involved in the host range barrier for SIV to HIV viruses are: *Gag-30 protein - specifically the amino acid at position 30 *The use of Nef or Vpu proteins as an anti-tetherin defence Only a SIV virus containing both mutations of the Gag-30 protein and acquisition of the Vpu anti-tetherin protein will be able to undergo a host switch from primates to humans and become a HIV. This evolutionary adaptations allows the virus to acquire optimal levels of polymerase action in human infected cells and the ability to prevent destruction of the virus by tetherin.References

{{Reflist, 32em Evolutionary biology Parasitism