History Of New Orleans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of New Orleans, Louisiana, traces the city's development from its founding by the

The history of New Orleans, Louisiana, traces the city's development from its founding by the

French explorers, fur trappers and traders arrived in the area by the 1690s, some making settlements amid the Native American village of thatched huts along the

French explorers, fur trappers and traders arrived in the area by the 1690s, some making settlements amid the Native American village of thatched huts along the

Much of the colonial population in early days was of the wildest and, in part, of the most undesirable character: deported galley slaves, trappers, gold-hunters; the colonial governors' letters were full of complaints regarding the riffraff sent as soldiers as late as Kerlerec's administration (1753–1763). Shortly after the founding, slaves were required to build the public works of the nascent city for thirty days when the crops had been harvested.

Two large lakes (in reality

Much of the colonial population in early days was of the wildest and, in part, of the most undesirable character: deported galley slaves, trappers, gold-hunters; the colonial governors' letters were full of complaints regarding the riffraff sent as soldiers as late as Kerlerec's administration (1753–1763). Shortly after the founding, slaves were required to build the public works of the nascent city for thirty days when the crops had been harvested.

Two large lakes (in reality

In 1805, a census showed a heterogeneous population of 8,500, comprising 3,551 whites, 1,556 free blacks, and 3,105 slaves. Observers at the time and historians since believe there was an undercount and the true population was about 10,000.

In 1805, a census showed a heterogeneous population of 8,500, comprising 3,551 whites, 1,556 free blacks, and 3,105 slaves. Observers at the time and historians since believe there was an undercount and the true population was about 10,000.

The next dozen years were marked by the beginnings of self-government in city and state; by the excitement attending the

The next dozen years were marked by the beginnings of self-government in city and state; by the excitement attending the

The introduction of

The introduction of  The importance of New Orleans as a commercial center was reinforced when the

The importance of New Orleans as a commercial center was reinforced when the

Early in the

Early in the

The city again served as capital of Louisiana from 1865 to 1880. Throughout the years of the Civil War and the Reconstruction period the history of the city is inseparable from that of the state. All the constitutional conventions were held here, the seat of government again was here (in 1864–1882) and New Orleans was the center of dispute and organization in the struggle between political and ethnic blocks for the control of government.

The city again served as capital of Louisiana from 1865 to 1880. Throughout the years of the Civil War and the Reconstruction period the history of the city is inseparable from that of the state. All the constitutional conventions were held here, the seat of government again was here (in 1864–1882) and New Orleans was the center of dispute and organization in the struggle between political and ethnic blocks for the control of government.

There was a major street riot of July 30, 1866, at the time of the meeting of the radical constitutional convention. Businessman Charles T. Howard began the Louisiana State Lottery Company in an arrangement which involved bribing state legislators and governors for permission to operate the highly lucrative outfit, as well as legal manipulations that at one point interfered with the passing of one version of the state constitution.

There was a major street riot of July 30, 1866, at the time of the meeting of the radical constitutional convention. Businessman Charles T. Howard began the Louisiana State Lottery Company in an arrangement which involved bribing state legislators and governors for permission to operate the highly lucrative outfit, as well as legal manipulations that at one point interfered with the passing of one version of the state constitution.

During

During  The city suffered flooding in 1882.

The city hosted the 1884

The city suffered flooding in 1882.

The city hosted the 1884

In the early part of the 20th century the Francophone character of the city was still much in evidence, with one 1902 report describing "one-fourth of the population of the city speaks French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths is able to understand the language perfectly." As late as 1945, one still encountered elderly Creole women who spoke no English. The last major French language newspaper in New Orleans, '' L'Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans'', ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years; according to some sources '' Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans'' continued until 1955.

In 1905,

In the early part of the 20th century the Francophone character of the city was still much in evidence, with one 1902 report describing "one-fourth of the population of the city speaks French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths is able to understand the language perfectly." As late as 1945, one still encountered elderly Creole women who spoke no English. The last major French language newspaper in New Orleans, '' L'Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans'', ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years; according to some sources '' Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans'' continued until 1955.

In 1905,  In 1923 the

In 1923 the  In January 1961 a meeting of the city's white business leaders publicly endorsed desegregation of the city's public schools. That same year

In January 1961 a meeting of the city's white business leaders publicly endorsed desegregation of the city's public schools. That same year  The city experienced severe flooding in the May 8, 1995, Louisiana Flood when heavy rains suddenly dumped over a foot of water on parts of town faster than the pumps could remove the water. Water filled up the streets, especially in lower-lying parts of the city. Insurance companies declared more automobiles totaled than in any other U.S. incident up to that time. (See

The city experienced severe flooding in the May 8, 1995, Louisiana Flood when heavy rains suddenly dumped over a foot of water on parts of town faster than the pumps could remove the water. Water filled up the streets, especially in lower-lying parts of the city. Insurance companies declared more automobiles totaled than in any other U.S. incident up to that time. (See

The city suffered from the effects of a major hurricane on and after August 29, 2005, as

The city suffered from the effects of a major hurricane on and after August 29, 2005, as

New Orleans Levees Passed Hurricane Ida's Test, But Some Suburbs Flooded

/ref>

online

* Burns, Peter F. ''Reforming New Orleans : the contentious politics of change in the Big Easy'' (2015

online

* Clark, John G. ''New Orleans, 1718-1812: An Economic History'' (LSU Press 1970) * Cowen, Scott S. ''The inevitable city : the resurgence of New Orleans and the future of urban America'' (2014

online

* Dabney, Thomas Ewing. ''One Hundred Great Years-The Story of the Times Picayune from Its Founding to 1940'' (Read Books Ltd, 2013

online

* Dawdy, Shannon Lee. ''Building the Devil's Empire: French Colonial New Orleans'' (U of Chicago Press 2008) * Dessens, Nathalie. '' Creole City: A Chronicle of Early American New Orleans'' (University Press of Florida, 2015). xiv, 272 pp. * Devore, Donald E. ''Defying Jim Crow: African American Community Development and the Struggle for Racial Equality in New Orleans, 1900-1960'' (Louisiana State University Press, 2015) 276 pp. * Faber, Eberhard L. ''Building the Land of Dreams: New Orleans and the Transformation of Early America'' (2015) covers 1790s to 1820s. * Fraiser, Jim. ''The Garden District of New Orleans'' (U Press of Mississippi, 2012). * Grosz, Agnes Smith. "The Political Career of Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback." Louisiana Historical Quarterly 27 (1944): 527-612. * Guenin-Lelle, Dianne. ''The Story of French New Orleans: History of a Creole City'' (U Press of Mississippi, 2016). * Haas, Edward F. ''Political Leadership in a Southern City: New Orleans in the Progressive Era, 1896-1902'' (1988) * Haskins, James. ''Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback'' (1973). * Ingersoll, Thomas N. ''Mammon and Manon in Early New Orleans: The First Slave Society in the Deep South, 1718–1819'' (University of Tennessee Press, 1999) * Jackson, Joy J. ''New Orleans in the gilded age: politics and urban progress, 1880-1896'' (1969). * Mel Leavitt, ''A Short History of New Orleans'', Lexikos Publishing, 1982,

online

* Maestri, Robert. ''New Orleans City Guide'' (1938) famous WPA guide * Margavio, Anthony V., and Jerome Salomone. ''Bread and respect: the Italians of Louisiana'' (Pelican Publishing, 2014). * Nystrom, Justin A. ''New Orleans After the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom''(Johns Hopkins UP, 2010) 344 pages * Powell, Lawrence N.''The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans (Harvard University Press, 2012) 422 pp. * Rankin, David C. "The origins of Negro leadership in New Orleans during Reconstruction," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. ''Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era'' (1982) 155 – 90. * Rasmussen, Hans C. "The Culture of Bullfighting in Antebellum New Orleans," ''Louisiana History,'' 55 (Spring 2014), 133-76. * Simmons, LaKisha Michelle. ''Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2015). * Solnit, Rebecca, and Rebecca Snedeker. ''Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas'' (University of California Press, 2013) 166 pp. * Sluyter, Andrew et al. ''Hispanic and Latino New Orleans: Immigration and Identity since the Eighteenth Century'' (LSU Press, 2015. xviii, 210 pp. * Somers, Dale A. ''The Rise of Sports in New Orleans, 1850–1900'' (LSU Press, 1972). * Tyler, Pamela. ''Silk stockings & ballot boxes : women and politics in New Orleans, 1920-1963'' (1996

online

; In languages other than English: *

''New Orleans, the Place and the People''

(1895) * Henry Rightor: ''Standard History of New Orleans'' (1900) * John Smith Kendall

(1922)

Resources for research in New Orleans

exhaustive list of local archives and research centers, on the ''Louisiana Historical Society'' (founded 1835) website

University of Chicago's online histories and source documents {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of New Orleans 1718 establishments in the French colonial empire

The history of New Orleans, Louisiana, traces the city's development from its founding by the

The history of New Orleans, Louisiana, traces the city's development from its founding by the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

in 1718 through its period of Spanish control, then briefly back to French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

rule before being acquired by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

in 1803. During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, the last major battle was the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

in 1815. Throughout the 19th century, was the largest port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, exporting most of the nation's cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

output and other products to Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. With it being the largest city in the South at the start of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

(1861–1865), it was an early target for capture by Union forces. With its rich and unique cultural and architectural heritage, New Orleans remains a major destination for live music, tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure or business; also the theory and practice of touring (disambiguation), touring, the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists, and the business of operating tour (disambiguation), tours. Th ...

, conventions, and sporting events and annual Mardi Gras celebrations. After the significant destruction and loss of life resulting from Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina was a destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that caused over 1,800 fatalities and $125 billion in damage in late August 2005, especially in the city of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. It was at the time the cost ...

in 2005, the city would bounce back and rebuild in the ensuing years.

Pre-history through Native American era

The land mass that was to become the city of New Orleans was formed around 2200 BC when the Mississippi River deposited silt creating the delta region. Before Europeans colonized the settlement, the area was inhabited by Native Americans for about 1300 years. TheMississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, eart ...

peoples built mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically highe ...

s and earthworks in the area. Later Native Americans created a portage

Portage or portaging (Canada: ; ) is the practice of carrying water craft or cargo over land, either around an obstacle in a river, or between two bodies of water. A path where items are regularly carried between bodies of water is also called a ...

between the headwaters of Bayou St. John (known to the natives as Bayouk Choupique) and the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

. The bayou flowed into Lake Pontchartrain

Lake Pontchartrain ( ) is an estuary located in southeastern Louisiana in the United States. It covers an area of with an average depth of . Some shipping channels are kept deeper through dredging. It is roughly oval in shape, about from w ...

. This became an important trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sing ...

. Archaeological evidence has shown settlement in the New Orleans dating back to at least 400 A.D. Bulbancha was one of the original names of New Orleans and it translates to "place of many tongues" in Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, Bulbancha was an important trading hub for thousands of years.

Colonial era

First French colonial period

French explorers, fur trappers and traders arrived in the area by the 1690s, some making settlements amid the Native American village of thatched huts along the

French explorers, fur trappers and traders arrived in the area by the 1690s, some making settlements amid the Native American village of thatched huts along the Bayou

In usage in the Southern United States, a bayou () is a body of water typically found in a flat, low-lying area. It may refer to an extremely slow-moving stream, river (often with a poorly defined shoreline), marshy lake, wetland, or creek. They ...

. By the end of the decade, the French made an encampment called "Port Bayou St. Jean" near the head of the bayou; this would later be known as the Faubourg St. John neighborhood. The French also built a small fort, "St. Jean" (known to later generations of New Orleanians as "Old Spanish Fort") at the mouth of the bayou in 1701, using as a base a large Native American shell midden

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and eco ...

dating back to the Marksville culture. In 1708, land grants along the Bayou were given to French settlers from Mobile, but the majority left within the next two years due to the failure of attempts to grow wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

there. These early European settlements are now within the limits of the city of New Orleans, though they predate the city's official founding.

New Orleans was founded in early 1718 by the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

as ''La Nouvelle-Orléans'', under the direction of Louisiana governor Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville (; ; February 23, 1680 – March 7, 1767), also known as Sieur de Bienville, was a French colonial administrator in New France. Born in Montreal, he was an early governor of French Louisiana, appointed four ...

. After considering several alternatives, Bienville selected the site for several strategic reasons and practical considerations, including: it was relatively high ground, along a sharp bend of the flood-prone Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

, which thus created a natural levee

A levee (), dike (American English), dyke (Commonwealth English), embankment, floodbank, or stop bank is a structure that is usually earthen and that often runs parallel to the course of a river in its floodplain or along low-lying coastli ...

(previously chosen as the site of an abandoned Quinipissa village); it was adjacent to the trading route and portage between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain

Lake Pontchartrain ( ) is an estuary located in southeastern Louisiana in the United States. It covers an area of with an average depth of . Some shipping channels are kept deeper through dredging. It is roughly oval in shape, about from w ...

via Bayou St. John, offering access to the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

of Biloxi without going downriver 100 miles; and it offered control of the entire Mississippi River Valley, at a safe distance from Spanish and English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

colonial settlements.

From its founding, the French intended New Orleans to be an important colonial city. The city was named in honor of the then Regent of France, Philip II, Duke of Orléans. The regent allowed Scottish economist John Law

John Law may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John Law (artist) (born 1958), American artist

* John Law (comics), comic-book character created by Will Eisner

* John Law (film director), Hong Kong film director

* John Law (musician) (born 1961) ...

to create a private bank and a financing scheme that succeeded in increasing the colonial population of New Orleans and other areas of Louisiana. The scheme, however, created an investment bubble that burst at the end of 1720. Law's Mississippi Company

The Mississippi Company (french: Compagnie du Mississippi; founded 1684, named the Company of the West from 1717, and the Company of the Indies from 1719) was a corporation holding a business monopoly in French colonies in North America and t ...

collapsed, stopping the flow of investment money to New Orleans. Nonetheless, in 1722, New Orleans was made the capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

of French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana refers to two distinct regions:

* first, to colonial French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by France during the 17th and 18th centuries; and,

* second, to modern French Louisi ...

, replacing Biloxi in that role.

The priest-chronicler Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix

Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix, S.J. ( la, Petrus Franciscus-Xaverius de Charlevoix; 24 or 29 October 1682 – 1 February 1761) was a French Jesuit priest, traveller, and historian, often considered the first historian of New France. He ha ...

described New Orleans in 1721 as a place of a hundred wretched hovels in a malarious wet thicket of willows and dwarf palmetto

''Sabal minor'', commonly known as the dwarf palmetto, is a small species of palm. It is native to the deep southeastern and south-central United States and northeastern Mexico. It is naturally found in a diversity of habitats, including maritime ...

s, infested by serpents and alligators; he seems to have been the first, however, to predict for it an imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas

...

future.

In September 1722, a hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Dep ...

struck the city, blowing most of the structures down. After this, the administrators enforced the grid pattern dictated by Bienville but hitherto previously mostly ignored by the colonists. This grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogon ...

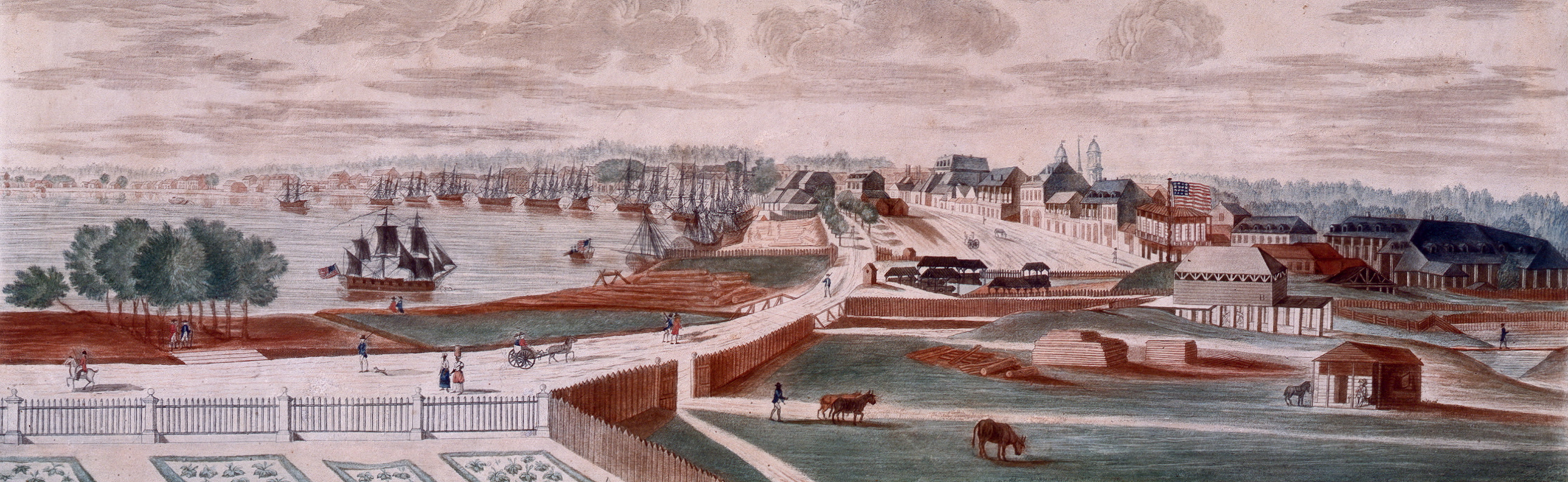

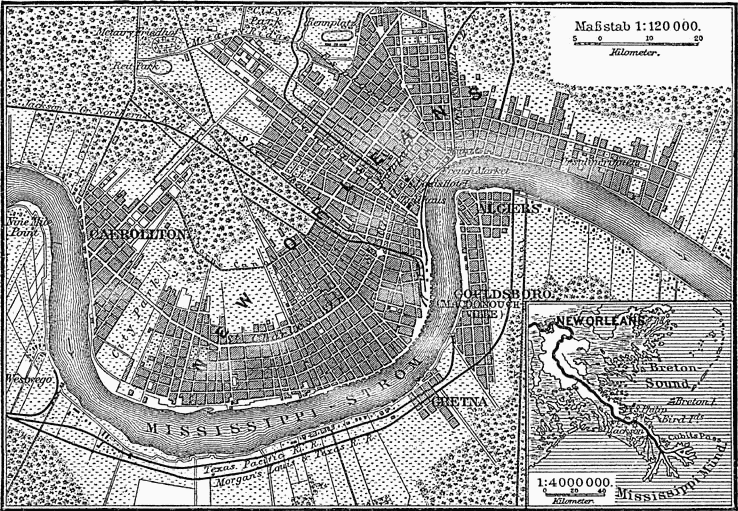

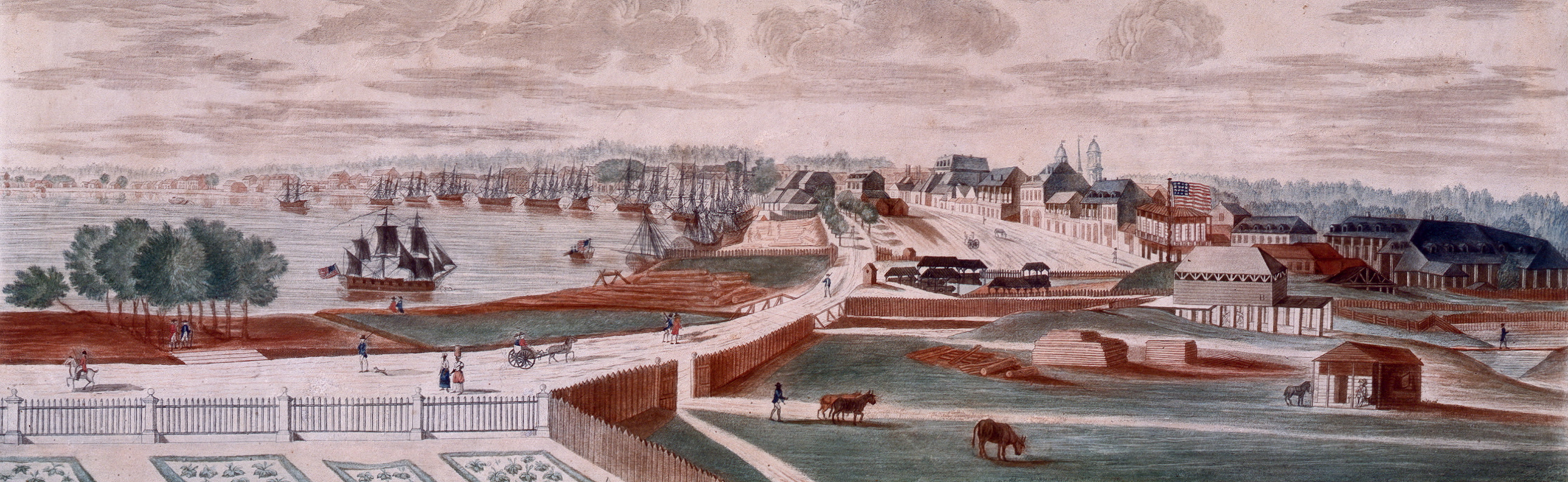

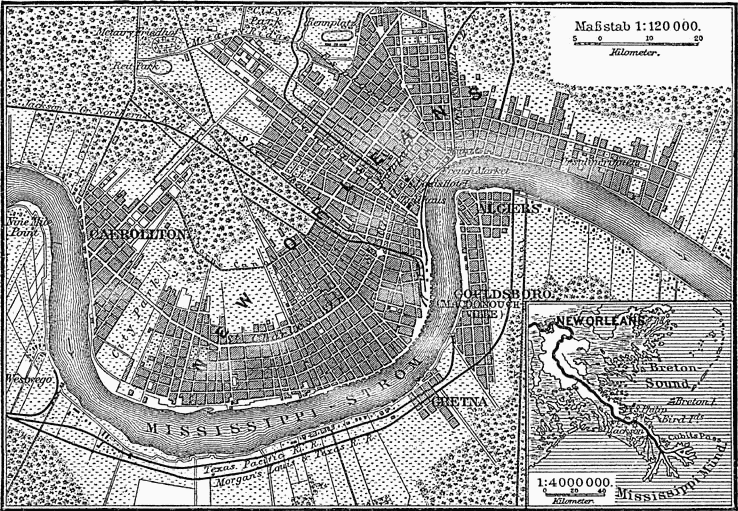

is still seen today in the streets of the city's " French Quarter" (''see map'').

Much of the colonial population in early days was of the wildest and, in part, of the most undesirable character: deported galley slaves, trappers, gold-hunters; the colonial governors' letters were full of complaints regarding the riffraff sent as soldiers as late as Kerlerec's administration (1753–1763). Shortly after the founding, slaves were required to build the public works of the nascent city for thirty days when the crops had been harvested.

Two large lakes (in reality

Much of the colonial population in early days was of the wildest and, in part, of the most undesirable character: deported galley slaves, trappers, gold-hunters; the colonial governors' letters were full of complaints regarding the riffraff sent as soldiers as late as Kerlerec's administration (1753–1763). Shortly after the founding, slaves were required to build the public works of the nascent city for thirty days when the crops had been harvested.

Two large lakes (in reality estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environme ...

) in the vicinity, Lake Pontchartrain

Lake Pontchartrain ( ) is an estuary located in southeastern Louisiana in the United States. It covers an area of with an average depth of . Some shipping channels are kept deeper through dredging. It is roughly oval in shape, about from w ...

and Lake Maurepas, commemorate respectively Louis Phelypeaux, Count Pontchartrain, minister and chancellor of France, and Jean Frederic Phelypeaux, Count Maurepas, minister and secretary of state. A third body of water, Lake Borgne

Lake Borgne (french: Lac Borgne, es, Lago Borgne) is a lagoon of the Gulf of Mexico in southeastern Louisiana. Although early maps show it as a lake surrounded by land, coastal erosion has made it an arm of the Gulf of Mexico. Its name comes fro ...

, was originally a land-locked inlet of the sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

; its name has reference to its incomplete or defective character.

Spanish interregnum

In 1763 following Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War, the French colony west of the Mississippi River—plus New Orleans—was ceded to theSpanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

as a secret provision of the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau, confirmed the following year in the Treaty of Paris. This was to compensate Spain for the loss of Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

to the British, who also took the remainder of the formerly French territory east of the River

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of ...

.

No Spanish governor came to take control until 1766. French and German settlers, hoping to restore New Orleans to French control, forced the Spanish governor to flee to Spain in the bloodless Rebellion of 1768

The Rebellion of 1768, also known as the Revolt of 1768 or the Creole Revolt, was an unsuccessful attempt by the Creole elite of New Orleans, along with nearby German settlers, to reverse the transfer of the French Louisiana Territory to Spain, a ...

. A year later, the Spanish reasserted control, executing five ringleaders and sending five plotters to a prison in Cuba, and formally instituting Spanish law. Other members of the rebellion were forgiven as long as they pledged loyalty to Spain. Although a Spanish governor was in New Orleans, it was under the jurisdiction of the Spanish garrison in Cuba.

In the final third of the Spanish period, two massive fires burned the great majority of the city's buildings. The Great New Orleans Fire of 1788 destroyed 856 buildings in the city on Good Friday

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Holy ...

, March 21 of that year. In December 1794 another fire destroyed 212 buildings. After the fires, the city was rebuilt with bricks, replacing the simpler wooden buildings constructed in the early colonial period. Much of the 18th-century architecture still present in the French Quarter was built during this time, including three of the most impressive structures in New Orleans— St. Louis Cathedral, the Cabildo

The Cabildo was the seat of Spanish colonial city hall of New Orleans, Louisiana, and is now the Louisiana State Museum Cabildo. It is located along Jackson Square, adjacent to St. Louis Cathedral.

History

The original Cabildo was destroyed ...

and the Presbytere. The architectural character of the French Quarter, including multi-storied buildings centered around inner courtyards, large arched doorways, and the use of decorative wrought iron, were ubiquitous in parts of Spain and the Spanish colonies, although precedents in French colonial and even Anglo-colonial America exist. Spanish influence on the urban landscape in New Orleans may be attributed to the fact that the period of Spanish rule saw a great deal of immigration from all over the Atlantic, including Spain and the Canary Islands, and the Spanish colonies.

In 1795 and 1796, the sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

processing industry was first put upon a firm basis. The last twenty years of the 18th century were especially characterized by the growth of commerce

Commerce is the large-scale organized system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions directly and indirectly related to the exchange (buying and selling) of goods and services among two or more parties within local, regional, natio ...

on the Mississippi, and the development of those international interests, commercial and political, of which New Orleans was the center. Within the city, the Carondelet Canal, connecting the back of the city along the river levee with Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. John, opened in 1794, which was a boost to commerce.

Through Pinckney's Treaty signed on October 27, 1795, Spain granted the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

"Right of Deposit" in New Orleans, allowing Americans to use the city's port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

facilities.

Retrocession to France and Louisiana Purchase

In 1800, Spain and France signed the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso stipulating that Spain give Louisiana back to France, although it had to remain under Spanish control as long as France wished to postpone the transfer of power. There was another relevant treaty in 1801, the Treaty of Aranjuez, and later a royal bill issued by KingCharles IV of Spain

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles III of Spain

, mother = Maria Amalia of Saxony

, birth_date =11 November 1748

, birth_place =Palace of Portici, Portici, Naples

, death_date =

, death_place ...

in 1802; these confirmed and finalized the retrocession of Spanish Louisiana to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

In April 1803, Napoleon sold Louisiana (New France)

Louisiana (french: La Louisiane; ''La Louisiane Française'') or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682 to 1769 and 1801 (nominally) to 1803, the area was named in honor of King Louis XIV, ...

(which then included portions of more than a dozen present-day states) to the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

. A French prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

, Pierre Clément de Laussat, who had only arrived in New Orleans on March 23, 1803, formally took control of Louisiana for France on November 30, only to hand it over to the U.S. on December 20, 1803. In the meantime he created New Orleans' first city council, abolishing the Spanish '' cabildo''.

19th century

In 1805, a census showed a heterogeneous population of 8,500, comprising 3,551 whites, 1,556 free blacks, and 3,105 slaves. Observers at the time and historians since believe there was an undercount and the true population was about 10,000.

In 1805, a census showed a heterogeneous population of 8,500, comprising 3,551 whites, 1,556 free blacks, and 3,105 slaves. Observers at the time and historians since believe there was an undercount and the true population was about 10,000.

Early 19th century: a rapidly growing commercial center

The next dozen years were marked by the beginnings of self-government in city and state; by the excitement attending the

The next dozen years were marked by the beginnings of self-government in city and state; by the excitement attending the Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

conspiracy (in the course of which, in 1806–1807, General James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson (March 24, 1757 – December 28, 1825) was an American soldier, politician, and double agent who was associated with several scandals and controversies.

He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, bu ...

practically put New Orleans under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

); and by the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

. From early days the city was noted for its cosmopolitan polyglot population and mixture of cultures. It grew rapidly, with influxes of Americans, African, French and Creole French (people of French descent born in the Americas) and Creoles of color

The Creoles of color are a historic ethnic group of Creole people that developed in the former French and Spanish colonies of Louisiana (especially in the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, and Northwestern Florida i.e. Pensacola, Flor ...

(people of mixed European and African ancestry), many of the latter two groups fleeing from the violent revolution in Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

.

The Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on ...

(1791–1804) in the former French colony of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to ref ...

established the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first led by blacks. Refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s, both white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

and free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

(''affranchis'' or ''gens de couleur libres''), arrived in New Orleans, often bringing slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

with them. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out additional free black men, French Creoles wanted to increase the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

-speaking population. As more refugees were allowed into the Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 180 ...

, Haitian émigrés who had gone to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

also arrived. Nearly 90 percent of the new immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites; 3,102 free persons of African descent; and 3,226 additional enslaved individuals to the city, doubling its French-speaking population. An 1809-1810 migration brought thousands of white francophone refugees (deported by officials in Cuba in response to Bonapartist schemes in Spain).

Plantation slaves' rebellion

The Haitian Revolution also increased ideas of resistance among the slave population in the vicinity of New Orleans. Early in 1811, hundreds of slaves revolted in what became known as the German Coast Uprising. The revolt occurred on the east bank of the Mississippi River in St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes,Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 180 ...

. While the slave insurgency was the largest in U.S. history, the rebels killed only two white men. Confrontations with militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and executions after locally-held tribunals killed ninety-five black people.

Between 64 and 125 enslaved men marched from sugar plantations near present-day LaPlace

Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. He summarized ...

on the German Coast toward the city of New Orleans. They collected more men along the way. Some accounts claimed a total of 200 to 500 slaves participated. During their two-day, twenty-mile march, the men burned five plantation houses (three completely), several sugar houses (small sugar cane mill

A sugar cane mill is a factory that processes sugar cane to produce raw or white sugar.

The term is also used to refer to the equipment that crushes the sticks of sugar cane to extract the juice.

Processing

There are a number of steps in pro ...

s), and crops. They were armed mostly with hand tools.

White men led by officials of the territory formed militia companies to hunt down and kill the insurgents, backed up by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

under the command of Brigadier General Wade Hampton I

Wade Hampton (early 1750sFebruary 4, 1835) was an American soldier and politician. A two-term U.S. Congressman, he may have been the wealthiest planter, and one of the largest slave holders in the United States, at the time of his death.

Biogr ...

, a slave owner himself, and by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

under Commodore John Shaw. Over the next two weeks, white planters and officials interrogated, sentenced, and carried out summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes includ ...

s of an additional 44 insurgents who had been captured. The tribunals were held in three locations, in the two parishes involved and in Orleans Parish (New Orleans). Executions were by hanging, decapitation, or firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are ...

(St. Charles Parish). Whites displayed the bodies as a warning to intimidate the enslaved. The heads of some were put on pikes and displayed along the River Road and at the ''Place d'Armes'' in New Orleans.

Since 1995 the African American History Alliance of Louisiana has led an annual commemoration in January of the uprising, in which they have been joined by some descendants of participants in the revolt.

War of 1812

During theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, the British sent a large force to conquer the city, but they were defeated early in 1815 by Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's combined forces some miles downriver from the city at Chalmette's plantation, during the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

. The American government managed to obtain early information of the enterprise and prepared to meet it with forces (regular, militia, and naval) under the command of Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson. Privateers led by Jean Lafitte

Jean Lafitte ( – ) was a French pirate and privateer who operated in the Gulf of Mexico in the early 19th century. He and his older brother Pierre spelled their last name Laffite, but English language documents of the time used "Lafitte". Th ...

were also recruited for the battle.

The British advance was made by way of Lake Borgne

Lake Borgne (french: Lac Borgne, es, Lago Borgne) is a lagoon of the Gulf of Mexico in southeastern Louisiana. Although early maps show it as a lake surrounded by land, coastal erosion has made it an arm of the Gulf of Mexico. Its name comes fro ...

, and the troops landed at a fisherman's village on December 23, 1814, Major-General Sir Edward Pakenham

Major General Sir Edward Michael Pakenham, (19 March 1778 – 8 January 1815), was a British Army officer and politician. He was the son of the Baron Longford and the brother-in-law of the Duke of Wellington, with whom he served in the Pe ...

taking command there two days later (Christmas). An immediate advance on the still insufficiently-prepared defenses of the Americans might have led to the capture of the city; but this was not attempted, and both sides limited themselves to relatively small skirmishes and a naval battle while awaiting reinforcements. At last in the early morning of January 8, 1815 (after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed but before the news had reached across the Atlantic), a direct attack was made on the now strongly-entrenched line of defenders at Chalmette, near the Mississippi River. It failed disastrously with a loss of 2,000 out of 9,000 British troops engaged, among the dead being Pakenham and Major-General Gibbs. The expedition was soon afterwards abandoned and the troops embarked, under the command of John Lambert John Lambert may refer to:

* John Lambert (martyr) (died 1538), English Protestant martyred during the reign of Henry VIII

*John Lambert (general) (1619–1684), Parliamentary general in the English Civil War

* John Lambert of Creg Clare (''fl.'' c ...

. Another engagement followed: a ten-day artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

battle at Fort St. Philip on the lower Mississippi River. The British fleet set sail on January 18 and went on to capture Fort Bowyer at the entrance to Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. The ...

.

General Jackson had arrived in New Orleans in early December 1814, having marched overland from Mobile in the Mississippi Territory

The Territory of Mississippi was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 7, 1798, until December 10, 1817, when the western half of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Mississippi. T ...

. His final departure was not until mid-March 1815. Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

was maintained in the city throughout the period of three and a half months.

Antebellum New Orleans

The population of the city doubled in the 1830s with an influx of settlers. A few newcomers to the city were friends of theMarquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

who had settled in the newly founded city of Tallahassee, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

, but due to legalities had lost their deeds. One new settler who was not displaced but chose to move to New Orleans to practice law was Prince Achille Murat

Charles Louis Napoleon Achille Murat (known as Achille, 21 January 1801 – 15 April 1847) was the eldest son of Joachim Murat, the brother-in-law of Napoleon who was appointed King of Naples during the First French Empire. After his father was de ...

, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

. According to historian Paul Lachance, "the addition of white immigrants to the white creole population enabled French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

-speakers to remain a majority of the white population until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of free persons of color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820." Large numbers of German and Irish immigrants began arriving at this time. The population of the city doubled in the 1830s and by 1840 New Orleans had become the wealthiest and third-most populous city in the nation.

By 1840, the city's population was approximately 102,000 and it was now the third-largest in the U.S, the largest city away from the Atlantic seaboard

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the co ...

as well as the largest in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

.

The introduction of

The introduction of natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbon d ...

(about 1830); the building of the Pontchartrain Rail-Road

Pontchartrain Rail-Road was the first railway in New Orleans, Louisiana. Chartered in 1830, the railroad began carrying people and goods between the Mississippi River front and Lake Pontchartrain on 23 April 1831. It closed more than 100 years ...

(1830–31), one of the earliest in the United States; the introduction of the first steam-powered cotton press (1832), and the beginning of the public school system (1840) marked these years; foreign exports more than doubled in the period 1831–1833. In 1838 the commercially-important New Basin Canal opened a shipping route from the Lake to uptown New Orleans. Travelers in this decade have left pictures of the animation of the river trade more congested in those days of river boats, steamers, and ocean-sailing craft than today; of the institution of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, the quadroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron was a person with one quarter African/ Aboriginal and three quarters European ancestry.

Similar classifications were octoroon for one-eighth black (Latin root ''oc ...

balls, the medley of Latin tongues, the disorder and carousing of the river-men and adventurers that filled the city. Altogether there was much of the wildness of a frontier town, and a seemingly boundless promise of prosperity. The crisis of 1837, indeed, was severely felt, but did not greatly retard the city's advancement, which continued unchecked until the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

. In 1849 Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. Located the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, it is the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana's most populous parish—the equivalent of counti ...

replaced New Orleans as the capital of the state. In 1850 telegraphic communication was established with St. Louis and New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

; in 1851 the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern railway, the first railway outlet northward, later part of the Illinois Central

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also c ...

, and in 1854 the western outlet, now the Southern Pacific, were begun.

In 1836 the city was divided into three municipalities: the first being the French Quarter and Faubourg Tremé, the second being Uptown (then meaning all settled areas upriver from Canal Street), and the third being Downtown (the rest of the city from Esplanade Avenue on, downriver). For two decades the three Municipalities were essentially governed as separate cities, with the office of Mayor of New Orleans having only a minor role in facilitating discussions between municipal governments.

The importance of New Orleans as a commercial center was reinforced when the

The importance of New Orleans as a commercial center was reinforced when the United States Federal Government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fed ...

established a branch of the United States Mint there in 1838, along with two other Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

branch mints at Charlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most popu ...

, and Dahlonega, Georgia

The city of Dahlonega () is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at the north end of ...

. Although there was an existing coin shortage, the situation became much worse because in 1836 President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

had issued an executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

, called a specie circular, which demanded that all land transactions in the United States be conducted in cash

In economics, cash is money in the physical form of currency, such as banknotes and coins.

In bookkeeping and financial accounting, cash is current assets comprising currency or currency equivalents that can be accessed immediately or near-im ...

, thus increasing the need for minted money. In contrast to the other two Southern branch mints, which only minted gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

coins, the New Orleans Mint produced both gold and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

coinage, which perhaps marked it as the most important branch mint in the country.

The mint produced coins from 1838 until 1861, when Confederate forces occupied the building and used it briefly as their own coinage facility until it was recaptured by Union forces the following year.

On May 3, 1849, a Mississippi River levee

A levee (), dike (American English), dyke (Commonwealth English), embankment, floodbank, or stop bank is a structure that is usually earthen and that often runs parallel to the course of a river in its floodplain or along low-lying coastli ...

breach upriver from the city (around modern River Ridge, Louisiana) created the worst flooding the city had ever seen. The flood, known as Sauvé's Crevasse

Sauvé's Crevasse was a Mississippi River levee failure in May 1849 that resulted in flooding much of New Orleans, Louisiana.

In May 1849 the Mississippi reached the highest water level in this area observed in twenty-one years. Some seventeen mi ...

, left 12,000 people homeless. While New Orleans has experienced numerous floods large and small in its history, the flood of 1849 was of a more disastrous scale than any save the flooding after Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina was a destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that caused over 1,800 fatalities and $125 billion in damage in late August 2005, especially in the city of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. It was at the time the cost ...

in 2005. New Orleans has not experienced flooding from the Mississippi River since Sauvé's Crevasse, although it came dangerously close during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

The slave trade

New Orleans was the biggest slave trading center in the country. In the 1840s, there were about 50 people-selling companies. Some whites went to the slave auctions for entertainment. Especially for travelers, the markets were a rival to the French Opera House and the Théâtre d’Orléans. The St. Louis Hotel#slave market and New Orleans Exchange held important markets. There was great demand for "fancy girls": young, light-skinned, good looking, sexual toys for well-to-do gentlemen.The Civil War

Early in the

Early in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

New Orleans was captured by the Union without a battle in the city itself, and hence was spared the destruction suffered by many other cities of the American South. It retains a historical flavor with a wealth of 19th century structures far beyond the early colonial city boundaries of the French Quarter.

The political and commercial importance of New Orleans, as well as its strategic position, marked it out as the objective of a Union expedition soon after the opening of the Civil War. Elements of the Union Blockade

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlanti ...

fleet arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi on 27 May 1861. An effort to drive them off lead to the Battle of the Head of Passes on 12 October 1861. Captain D.G. Farragut and the Western Gulf squadron sailed for New Orleans in January 1862. The main defenses of the Mississippi consisted of the two permanent forts, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. On April 16, after elaborate reconnaissances, the Union fleet steamed up into position below the forts and opened fire two days later. Within days, the fleet had bypassed the forts in what was known as the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. At noon on the 25th, Farragut anchored in front of New Orleans. Forts Jackson and St. Philip, isolated and continuously bombarded by Farragut's mortar boats, surrendered on the 28th, and soon afterwards the military portion of the expedition occupied the city resulting in the Capture of New Orleans

The capture of New Orleans (April 25 – May 1, 1862) during the American Civil War was a turning point in the war, which precipitated the capture of the Mississippi River. Having fought past Forts Jackson and St. Philip, the Union was ...

.

The commander, General Benjamin Butler, subjected New Orleans to a rigorous martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

so tactlessly administered as greatly to intensify the hostility of South and North. Butler's administration did have benefits to the city, which was kept both orderly and due to his massive cleanup efforts unusually healthy by 19th century standards. Towards the end of the war General Nathaniel Banks held the command at New Orleans.

Late 19th century: Reconstruction and conflict

The city again served as capital of Louisiana from 1865 to 1880. Throughout the years of the Civil War and the Reconstruction period the history of the city is inseparable from that of the state. All the constitutional conventions were held here, the seat of government again was here (in 1864–1882) and New Orleans was the center of dispute and organization in the struggle between political and ethnic blocks for the control of government.

The city again served as capital of Louisiana from 1865 to 1880. Throughout the years of the Civil War and the Reconstruction period the history of the city is inseparable from that of the state. All the constitutional conventions were held here, the seat of government again was here (in 1864–1882) and New Orleans was the center of dispute and organization in the struggle between political and ethnic blocks for the control of government.

There was a major street riot of July 30, 1866, at the time of the meeting of the radical constitutional convention. Businessman Charles T. Howard began the Louisiana State Lottery Company in an arrangement which involved bribing state legislators and governors for permission to operate the highly lucrative outfit, as well as legal manipulations that at one point interfered with the passing of one version of the state constitution.

There was a major street riot of July 30, 1866, at the time of the meeting of the radical constitutional convention. Businessman Charles T. Howard began the Louisiana State Lottery Company in an arrangement which involved bribing state legislators and governors for permission to operate the highly lucrative outfit, as well as legal manipulations that at one point interfered with the passing of one version of the state constitution.

During

During Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, New Orleans was within the Fifth Military District of the United States. Louisiana was readmitted to the Union in 1868, and its Constitution of 1868 granted universal manhood suffrage. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, then-lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback

Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback (May 10, 1837 – December 21, 1921) was an American publisher, politician, and Union Army officer. Pinchback was the second African American (after Oscar Dunn) to serve as governor and lieutenant governor of a ...

succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth as governor of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

, becoming the first non-white governor of a U.S. state, and the last African American to lead a U.S. state until Douglas Wilder

Lawrence Douglas Wilder (born January 17, 1931) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 66th Governor of Virginia from 1990 to 1994. He was the first African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state since the Reconstructi ...

's election in Virginia, 117 years later. In New Orleans, Reconstruction was marked by the Mechanics Institute race riot (1866). The city operated successfully a racially integrated public school system

State schools (in England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand) or public schools (Scottish English and North American English) are generally primary or secondary schools that educate all students without charge. They are funded in whole or in p ...

. Damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade for the port city for some time, as the government tried to restore infrastructure. The nationwide Panic of 1873 also slowed economic recovery.

In the 1850s white Francophones had remained an intact and vibrant community, maintaining instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts.''The Bourgeois Frontier: French towns, French traders, and American expansion'' by Jay Gitlin. Yale University Press. pg 166 As the Creole elite feared, during the war, their world changed. In 1862, the Union general Ben Butler abolished French instruction in schools, and statewide measures in 1864 and 1868 further cemented the policy. By the end of the 19th century, French usage in the city had faded significantly.

New Orleans annexed the city of Algiers, Louisiana, across the Mississippi River, in 1870. The city also continued to expand upriver, annexing the town of Carrollton, Louisiana in 1874.

On September 14, 1874 armed forces led by the White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

defeated the integrated Republican metropolitan police and their allies in pitched battle in the French Quarter and along Canal Street. The White League forced the temporary flight of the William P. Kellogg

William Pitt Kellogg (December 8, 1830 – August 10, 1918) was an American lawyer and Republican Party politician who served as a United States Senator from 1868 to 1872 and from 1877 to 1883 and as the Governor of Louisiana from 1873 to 1877 d ...

government, installing John McEnery

John McEnery (1 November 1943 – 12 April 2019) was an English actor and writer.

Born in Birmingham, he trained (1962–1964) at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, playing, among others, Mosca in Ben Jonson's ''Volpone'' and Gaveston ...

as Governor of Louisiana. Kellogg and the Republican administration were reinstated in power 3 days later by United States troops. Early 20th century segregationists

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

would celebrate the short-lived triumph of the White League as a victory for "white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

" and dubbed the conflict "The Battle of Liberty Place

The Battle of Liberty Place, or Battle of Canal Street, was an attempted insurrection and coup d'etat by the Crescent City White League against the Reconstruction Era Louisiana Republican state government on September 14, 1874, in New Orleans ...

". A monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, hist ...

commemorating the event was built near the foot of Canal Street, to the side of the Aquarium near the trolley tracks. This monument was removed on April 24, 2017. The removal fell on the same day that three states—Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia—observed what's known as Confederate Memorial Day.

U.S. troops also blocked the White League Democrats in January 1875, after they had wrested from the Republicans the organization of the state legislature. Nevertheless, the revolution of 1874 is generally regarded as the independence day of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, although not until President Hayes

Hayes may refer to:

* Hayes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Rutherford B. Hayes, 19th president of the United States

* Hayes (given name)

Businesses

* Hayes Brake, an American designer and manufacturer of disc brakes

* Hay ...

withdrew the troops in 1877 and the Packard government fell did the Democrats actually hold control of the state and city. The financial condition of the city when the whites gained control was very bad. The tax-rate had risen in 1873 to 3%. The city defaulted in 1874. On the interest of its bonded debt, it later refunded this ($22,000,000 in 1875) at a lower rate, to decrease the annual charge from $1,416,000 to $307,500.

The New Orleans Mint was reopened in 1879, minting mainly silver coinage, including the famed Morgan silver dollar from 1879 to 1904.

The city suffered flooding in 1882.

The city hosted the 1884

The city suffered flooding in 1882.

The city hosted the 1884 World's Fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

, called the World Cotton Centennial. A financial failure, the event is notable as the beginnings of the city's tourist economy.

An electric lighting system was introduced to the city in 1886; limited use of electric lights in a few areas of town had preceded this by a few years.

1890s

On October 15, 1890, Chief-of-Police David C. Hennessy was shot, and reportedly his dying words informed a colleague that he was shot by "Dagos", an insulting term forItalians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

. On March 13, 1891, a group of Italian American

Italian Americans ( it, italoamericani or ''italo-americani'', ) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, w ...

s on trial for the shooting were acquitted. However, a mob stormed the jail and lynched eleven Italian-Americans. Local historians still debate whether some of those lynched were connected to the Mafia, but most agree that a number of innocent people were lynched during the Chief Hennessy Riot. The government of Italy protested, as some of those lynched were still Italian citizens, and the government of the U.S. eventually paid reparations to Italy.

In the 1890s much of the city's public transportation system, hitherto relying on mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two po ...

-drawn streetcars on most routes supplemented by a few steam locomotives on longer routes, was electrified.

With a relatively large educated black (including a self-described "Creole" or mixed-race) population that had long interacted with the white population, racial attitudes were comparatively liberal for the Deep South. For example there was the 1892 New Orleans general strike

The New Orleans general strike was a general strike in the U.S. city of New Orleans, Louisiana, that began on November 8, 1892. Despite appeals to racial hatred, black and white workers remained united. The general strike ended on November 12, w ...