Haskalah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the

Resources > Modern Period > Central and Western Europe (17th\18th Cent.) > Enlightenment (Haskala)

The Jewish History Resource Center – Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The

Rashi by Maurice Liber

Discusses Rashi's influence on Moses Mendelssohn and the Haskalah.

* * *Rasplus, Valéry "Les judaïsmes à l'épreuve des Lumières. Les stratégies critiques de la Haskalah", in: ''ContreTemps'', n° 17, septembre 2006 * * Digital version available at '' European History Online''

* (translated from ''Oświecenie żydowskie w Królestwie Polskim wobec chasydyzmu'') * Brinker, Menahem (2008)

The Unique Case of Jewish Secularism

(audio archive giving history of ideas of the Haskalah movement and its later secular offshoot movements), London Jewish Book Week. *

Haskalah

at The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

Map of the spread of Haskalah

Haskalah collection

John Rylands Library, University of Manchester {{Authority control Hebrew words and phrases Jewish movements

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

of Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

, with a certain influence on those in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

. It arose as a defined ideological worldview during the 1770s, and its last stage ended around 1881, with the rise of Jewish nationalism

* Zionism, seeking territorial concentration of all Jews in the Land of Israel

* Jewish Territorialism, seeking territorial concentration in any land possible

* Jewish Autonomism, seeking an ethnic-cultural autonomy for the Jews of Eastern Europe

...

.

The ''Haskalah'' pursued two complementary aims. It sought to preserve the Jews as a separate, unique collective, and it pursued a set of projects of cultural and moral renewal, including a revival of Hebrew for use in secular life, which resulted in an increase in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

found in print. Concurrently, it strove for an optimal integration in surrounding societies. Practitioners promoted the study of exogenous culture, style, and vernacular, and the adoption of modern values. At the same time, economic production, and the taking up of new occupations was pursued. The ''Haskalah'' promoted rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

, liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

, freedom of thought

Freedom of thought (also called freedom of conscience) is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency ...

, and enquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of th ...

, and is largely perceived as the Jewish variant of the general Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. The movement encompassed a wide spectrum ranging from moderates, who hoped for maximal compromise, to radicals, who sought sweeping changes.

In its various changes, the ''Haskalah'' fulfilled an important, though limited, part in the modernization of Central and Eastern European Jews. Its activists, the ''Maskilim'', exhorted and implemented communal, educational and cultural reforms in both the public and the private spheres. Owing to its dual policies, it collided both with the traditionalist rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

nic elite, which attempted to preserve old Jewish values and norms in their entirety, and with the radical assimilationists who wished to eliminate or minimize the existence of the Jews as a defined collective.

Definitions

Literary circle

The Haskalah was multifaceted, with many loci which rose and dwindled at different times and across vast territories. The name ''Haskalah'' became a standard self-appellation in 1860, when it was taken as the motto of theOdessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

-based newspaper '' Ha-Melitz'', but derivatives and the title ''Maskil'' for activists were already common in the first edition of ''Ha-Meassef'' from 1 October 1783: its publishers described themselves as ''Maskilim''. While Maskilic centres sometimes had loose institutions around which their members operated, the movement as a whole lacked any such.

In spite of that diversity, the ''Maskilim'' shared a sense of common identity and self-consciousness. They were anchored in the existence of a shared literary canon, which began to be formulated in the very first Maskilic locus at Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

. Its members, like Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the '' Haskalah'', or ...

, Naphtali Hirz Wessely, Isaac Satanow and Isaac Euchel, authored tracts in various genres that were further disseminated and re-read among other Maskilim. Each generation, in turn, elaborated and added its own works to the growing body. The emergence of the Maskilic canon reflected the movement's central and defining enterprise, the revival of Hebrew as a literary language for secular purposes (its restoration as a spoken tongue occurred only much later). The Maskilim researched and standardized grammar, minted countless neologisms and composed poetry, magazines, theatrical works and literature of all sorts in Hebrew. Historians described the movement largely as a Republic of Letters, an intellectual community based on printing houses and reading societies.

The Maskilim's attitude toward Hebrew, as noted by Moses Pelli, was derived from Enlightenment perceptions of language as reflecting both individual and collective character. To them, a corrupt tongue mirrored the inadequate condition of the Jews which they sought to ameliorate. They turned to Hebrew as their primary creative medium. The Maskilim inherited the Medieval Grammarians' – such as Jonah ibn Janah and Judah ben David Hayyuj Judah ben David Hayyuj (Hebrew: ר׳ יְהוּדָה בֶּן דָּוִד חַיּוּג׳ Arabic: أبو زكريا يحيى بن داؤد حيوج Abu Zakariyya Yahya ibn Dawūd Hayyūj) was a Moroccan Jewish linguist. He is regarded as the fath ...

– distaste of Mishnaic Hebrew and preference of the Biblical one as pristine and correct. They turned to the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

as a source and standard, emphatically advocating what they termed "Pure Hebrew Tongue" (''S'fat E'ver tzacha'') and lambasting the Rabbinic style of letters, which mixed it with Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

as a single "Holy Tongue

''Holy Tongue'' ( it, La lingua del santo) is a 2000 Italian comedy film written and directed by Carlo Mazzacurati. It entered into the main competition at the 57th Venice International Film Festival.

Cast

* Antonio Albanese - Antonio

* Fa ...

" and often employed loanwords from other languages. Some activists, however, were not averse to using Mishnaic and Rabbinic forms. They also preferred the Sephardi pronunciation, considered more prestigious, to the Ashkenazi one, which was linked with the Jews of Poland

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lon ...

, who were deemed backward. The movement's literary canon is defined by a grandiloquent, archaic register copying the Biblical one and often combining lengthy allusions or direct quotes from verses in the prose.

During a century of activity, the Maskilim produced a massive contribution, forming the first phase of modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew ( he, עברית חדשה, ''ʿivrít ḥadašá ', , '' lit.'' "Modern Hebrew" or "New Hebrew"), also known as Israeli Hebrew or Israeli, and generally referred to by speakers simply as Hebrew ( ), is the standard form of the He ...

literature. In 1755, Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the '' Haskalah'', or ...

began publishing ''Qohelet Musar'' "The Moralist", regarded as the beginning of modern writing in Hebrew and the very first journal in the language. Between 1789 and his death, Naphtali Hirz Wessely compiled ''Shirei Tif'eret'' "Poems of Glory", an eighteen-part epic cycle concerning Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu ( Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pr ...

that exerted influence on all neo-Hebraic poets in the following generations. was the Haskalah's pioneering playwright, best known for his 1794 epic drama ''Melukhat Sha'ul'' "Reign of Saul

Saul (; he, , ; , ; ) was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the first monarch of the United Kingdom of Israel. His reign, traditionally placed in the late 11th century BCE, supposedly marked the transition of Israel and Judah from a scattered tri ...

", which was printed in twelve editions by 1888. Judah Leib Ben-Ze'ev

Judah Leib Ben-Ze'ev (, ; 18 August 176412 March 1811) was a Galician Jewish philologist, lexicographer, and Biblical scholar. He was a member of the Me'assefim group of Hebrew writers, and a "forceful proponent of revitalizing the Hebrew la ...

was the first modern Hebrew grammarian, and beginning with his 1796 manual of the language, he authored books which explored it and were vital reading material for young Maskilim until the end of the 19th century. Solomon Löwisohn was the first to translate Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

into Hebrew, and an abridged form of the "Are at this hour asleep!" monologue in '' Henry IV, Part 2'' was included in his 1816 lyrical compilation ''Melitzat Yeshurun'' (Eloquence of Jeshurun

Jeshurun ( he, יְשֻׁרוּן ''Yəšurūn''; also ''Jesurun'' or ''Yeshurun'') is a poetic name for Israel used in the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible. It is generally thought to be derived from a root word meaning upright, just or straight, but may ...

).

Joseph Perl pioneered satirist writings in his biting, mocking critique of Hasidic Judaism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism ( Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of cont ...

, ''Megaleh Tmirin'' "Revealer of Secrets" from 1819. Avraham Dov Ber Lebensohn

Abraham Dov Ber Lebensohn (; – November 19, 1878), also known by the pen names Abraham Dov-Ber Michailishker () and Adam ha-Kohen (), was a Lithuanian Jewish Hebraist, poet and educator.

Biography

Avraham Dov Ber Lebenson was born in Vilna, ...

was primarily a leading metricist, with his 1842 ''Shirei S'fat haQodesh'' "Verses in the Holy Tongue" considered a milestone in Hebrew poetry Hebrew poetry is poetry written in the Hebrew language. It encompasses such things as:

* Biblical poetry, the poetry found in the poetic books of the Hebrew Bible

* Piyyut, religious Jewish liturgical poetry in Hebrew or Aramaic

* Medieval Hebre ...

, and also authored biblical exegesis and educational handbooks. Abraham Mapu authored the first Hebrew full-length novel, ''Ahavat Zion'' "Love of Zion", which was published in 1853 after twenty-three years of work. Judah Leib Gordon

Judah Leib (Ben Asher) Gordon, also known as Leon Gordon, (December 7, 1830, Vilnius, Lithuania – September 16, 1892, St. Petersburg, Russia) (Hebrew: יהודה לייב גורדון) was among the most important Hebrew poets of the Jewish En ...

was the most eminent poet of his generation and arguably of the ''Haskalah'' in its entirety. His most famous work was the 1876 epic ''Qotzo shel Yodh

Yodh (also spelled jodh, yod, or jod) is the tenth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Yōd /𐤉, Hebrew Yōd , Aramaic Yod , Syriac Yōḏ ܝ, and Arabic . Its sound value is in all languages for which it is used; in many l ...

'' (Tittle of a Jot). Mendele Mocher Sforim was during his youth a Maskilic writer but from his 1886 ''B-Sether Ra'am'' (Hidden in Thunder), he abandoned its strict conventions in favour of a mixed, facile and common style. His career marked the end of the Maskilic period in Hebrew literature and the beginning of the Era of Renaissance. The writers of the latter period lambasted their Maskilic predecessors for their didactic and florid style, more or less paralleling the Romantics' criticism of Enlightenment literature.

The central platforms of the Maskilic "Republic of Letters" were its great periodicals, each serving as a locus for contributors and readers during the time it was published. The first was the Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was ...

(and later Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

)-based '' Ha-Meassef'', launched by Isaac Abraham Euchel

Isaac Abraham Euchel ( he, יצחק אייכל; born at Copenhagen, October 17, 1756; died at Berlin, June 14, 1804) was a Hebrew author and founder of the " Haskalah-movement".

He was born in Copenhagen on October 17, 1756. After his bar mitz ...

in 1783 and printed with growing intervals until 1797. The magazine had several dozen writers and 272 subscribers at its zenith, from Shklow

Shklow ( be, Шклоў, ; Škłoŭ; russian: link=no, Шклов, ''Shklov''; yi, שקלאָוו, ''Shklov'', lt, Šklovas, pl, Szkłów) is a town in Mogilev Region, Belarus, located north of Mogilev on the Dnieper river. It has a railway ...

in the east to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in the west, making it the sounding board of the Berlin ''Haskalah''. The movement lacked an equivalent until the appearance of ''Bikurei ha-I'tim'' in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

between 1820 until 1831, serving the Moravian and Galician ''Haskalah''. That function was later fulfilled by the Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

-based ''Kerem Hemed'' from 1834 to 1857, and to a lesser degree by ''Kokhvei Yizhak'', published in the same city from 1845 to 1870. The Russian ''Haskalah'' was robust enough to lack any single platform. Its members published several large magazines, including the Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

-based '' Ha-Karmel'' (1860–1880), ''Ha-Tsefirah'' in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

and more, though the probably most influential of them all was '' Ha-Melitz'', launched in 1860 at Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

by Aleksander Zederbaum.

Reforming movement

While the partisans of the ''Haskalah'' were much immersed in the study of sciences and Hebrew grammar, this was not a profoundly new phenomenon, and their creativity was a continuation of a long, centuries-old trend among educated Jews. What truly marked the movement was the challenge it laid to the monopoly of the rabbinic elite over the intellectual sphere of Jewish life, contesting its role as spiritual leadership. In his 1782 circular ''Divrei Shalom v'Emeth'' (Words of Peace and Truth),Hartwig Wessely

Naphtali Hirz (Hartwig) Wessely ( yi, נפתלי הירץ וויזעל, translit=Naftali Hirtz Vizel; 9 December 1725 – 28 February 1805) was an 18th-century German-Jewish Hebraist and educationist.

Family history

One of Wessely's ancestors, ...

, one of the most traditional and moderate ''maskilim'', quoted the passage from Leviticus Rabbah

Leviticus Rabbah, Vayikrah Rabbah, or Wayiqra Rabbah is a homiletic midrash to the Biblical book of Leviticus (''Vayikrah'' in Hebrew). It is referred to by Nathan ben Jehiel (c. 1035–1106) in his ''Arukh'' as well as by Rashi (1040–1105) ...

stating that a Torah scholar who lacked wisdom was inferior to an animal's carcass. He called upon the Jews to introduce general subjects, like science and vernacular language, into their children's curriculum; this "Teaching of Man" was necessarily linked with the "Teaching (''Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

'') of God", and the latter, though superior, could not be pursued and was useless without the former.

Historian Shmuel Feiner discerned that Wessely insinuated (consciously or not) a direct challenge to the supremacy of sacred teachings, comparing them with general subjects and implying the latter had an intrinsic rather than merely instrumental value. He therefore also contested the authority of the rabbinical establishment, which stemmed from its function as interpreters of the holy teachings and their status as the only truly worthy field of study. Though secular subjects could be and were easily tolerated, their elevation to the same level as sacred ones was a severe threat, and indeed mobilized the rabbis against the nascent ''Haskalah''. The potential of "Words of Peace and Truth" was fully realized later, by the second generation of the movement in Berlin and other radical ''maskilim'', who openly and vehemently denounced the traditional authorities. The appropriate intellectual and moral leadership needed by the Jewish public in modern times was, according to the ''maskilim'', that of their own. Feiner noted that in their usurpation of the title of spiritual elite, unprecedented in Jewish history since the dawn of Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonia ...

(various contestants before the Enlightened were branded as schismatics and cast out), they very much emulated the manner in which secular intellectuals dethroned and replaced the Church from the same status among Christians. Thus the ''maskilim'' generated an upheaval which – though by no means alone – broke the sway held by the rabbis and the traditional values over Jewish society. Combined with many other factors, they laid the path to all modern Jewish movements and philosophies, either those critical, hostile or supportive to themselves.

The ''maskilim'' sought to replace the framework of values held by the Ashkenazim of Central and Eastern Europe with their own philosophy, which embraced the liberal, rationalistic notions of the 18th and 19th centuries and cast them in their own particular mold. This intellectual upheaval was accompanied by the desire to practically change Jewish society. Even the moderate ''maskilim'' viewed the contemporary state of Jews as deplorable and in dire need of rejuvenation, whether in matters of morals, cultural creativity or economic productivity. They argued that such conditions were rightfully scorned by others and untenable from both practical and idealistic perspectives. It was to be remedied by the shedding of the base and corrupt elements of Jewish existence and retention of only the true, positive ones; indeed, the question what those were, exactly, loomed as the greatest challenge of Jewish modernity.

The more extreme and ideologically-bent came close to the universalist aspirations of the radical Enlightenment, of a world freed of superstition and backwardness in which all humans will come together under the liberating influence of reason and progress. The reconstituted Jews, these radical ''maskilim'' believed, would be able to take their place as equals in an enlightened world. But all, including the moderate and disillusioned, stated that adjustment to the changing world was both unavoidable and positive in itself.

''Haskalah'' ideals were converted into practical steps via numerous reform programs initiated locally and independently by its activists, acting in small groups or even alone at every time and area. Members of the movement sought to acquaint their people with European culture, have them adopt the vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

language of their lands, and integrate them into larger society. They opposed Jewish reclusiveness and self-segregation, called upon Jews to discard traditional dress in favour of the prevalent one, and preached patriotism and loyalty to the new centralized governments. They acted to weaken and limit the jurisdiction of traditional community institutions – the rabbinic courts, empowered to rule on numerous civic matters, and the board of elders, which served as lay leadership. The maskilim perceived those as remnants of medieval discrimination. They criticized various traits of Jewish society, such as child marriage – traumatized memories from unions entered at the age of thirteen or fourteen are a common theme in Haskalah literature – the use of anathema to enforce community will and the concentration on virtually only religious studies.

Maskilic reforms included educational efforts. In 1778, partisans of the movement were among the founders of the Berlin Jewish Free School, or ''Hevrat Hinuch Ne'arim'' (Society for the Education of Boys), the first institution in Ashkenazi Jewry that taught general studies in addition to the reformulated and reduced traditional curriculum. This model, with different stresses, was applied elsewhere. Joseph Perl opened the first modern Jewish school in Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

at Tarnopol

Ternópil ( uk, Тернопіль, Ternopil' ; pl, Tarnopol; yi, טאַרנאָפּל, Tarnopl, or ; he, טארנופול (טַרְנוֹפּוֹל), Tarnopol; german: Tarnopol) is a city in the west of Ukraine. Administratively, Terno ...

in 1813, and Eastern European ''maskilim'' opened similar institutes in the Pale of Settlement and Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. I ...

. They all abandoned the received methods of Ashkenazi education: study of the Pentateuch

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

with the archaic ''I'vri-Taitsch'' (medieval Yiddish) translation and an exclusive focus on the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

as a subject of higher learning, all presided over by old-school tutors, '' melamdim'', who were particularly reviled in maskilic circles. Those were replaced by teachers trained in modern methods, among others in the spirit of German philanthropinism, who sought to acquaint their pupils with refined Hebrew so they may understand the Pentateuch and prayers and thus better identify with their heritage; ignorance of Hebrew was often lamented by ''maskilim'' as breeding apathy towards Judaism. Far less Talmud, considered cumbersome and ill-suited for children, was taught; elements considered superstitious, like ''midrashim

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

'', were also removed. Matters of faith were taught in rationalistic spirit, and in radical circles also in a sanitized manner. On the other hand, the curriculum was augmented by general studies like math, vernacular language, and so forth.

In the linguistic field, the ''maskilim'' wished to replace the dualism which characterized the traditional Ashkenazi community, which spoke Judaeo-German and its formal literary language was Hebrew, with another: a refined Hebrew for internal usage and the local vernacular for external ones. They almost universally abhorred Judaeo-German, regarding it as a corrupt dialect and another symptom of Jewish destitution – the movement pioneered the negative attitude to Yiddish which persisted many years later among the educated – though often its activists had to resort to it for lack of better medium to address the masses. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

Aaron Halle-Wolfssohn Aaron Halle-Wolfssohn (; 1754 or 1756, in probably Halle – 20 March 1835, in Fürth) was a German-Jewish writer, translator, and Biblical commentator. He was a leading writer of the ''Haskalah''.

Biography

He was born in Halle and died in Fü ...

, for example, authored the first modern Judaeo-German play, ''Leichtsinn und Frömmelei'' (Rashness and Sanctimony) in 1796. On the economic front, the ''maskilim'' preached productivization and abandonment of traditional Jewish occupations in favour of agriculture, trades and liberal professions.

In matters of faith (which were being cordoned off into a distinct sphere of "religion" by modernization pressures) the movement's partisans, from moderates to radicals, lacked any uniform coherent agenda. The main standard through which they judged Judaism was that of rationalism. Their most important contribution was the revival of Jewish philosophy

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern '' Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcil ...

, rather dormant since the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

, as an alternative to mysticist ''Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and Jewish theology, school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "rece ...

'' which served as almost the sole system of thought among Ashkenazim and an explanatory system for observance. Rather than complex allegorical exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

, the ''Haskalah'' sought a literal understanding of scripture and sacred literature. The rejection of ''Kabbalah'', often accompanied with attempts to refute the ancientness of the '' Zohar'', were extremely controversial in traditional society; apart from that, the ''maskilim'' had little in common. On the right-wing were conservative members of the rabbinic elite who merely wanted a rationalist approach, and on the extreme left some ventured far beyond the pale of orthodoxy towards Deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning " god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation o ...

.

Another aspect was the movement's attitude to gender relations. Many of the ''maskilim'' were raised in the rabbinic elite, in which (unlike among the poor Jewish masses or the rich communal wardens) the males were immersed in traditional studies and their wives supported them financially, mostly by running business. Many of the Jewish enlightened were traumatized by their own experiences, either of assertive mothers or early marriage, often conducted at the age of thirteen. Bitter memories from those are a common theme in ''maskilic'' autobiographies. Having imbibed the image of European bourgeoisie family values, many of them sought to challenge the semi-matriarchal order of rabbinic families – which combined a lack of Jewish education for women with granting them the status of providers – early marriage, and rigid modesty. Instead, they insisted that men become economically productive while confining their wives to the home environment but also granting them proper religious education, a reversal of what was customary among Jews, copying Christian attitudes at the time.

Transitory phenomena

The ''Haskalah'' was also mainly a movement of transformation, straddling both the declining traditional Jewish society of autonomous community and cultural seclusion and the beginnings of a modern Jewish public. As noted by Feiner, everything connected with the ''Haskalah'' was dualistic in nature. The Jewish Enlighteners pursued two parallel agendas: they exhorted the Jews to acculturate and harmonize with the modern state, and demanded that the Jews remain a distinct group with its own culture and identity. Theirs was a middle position between Jewish community and surrounding society, received mores and modernity. Sliding away from this precarious equilibrium, in any direction, signified also one's break with the Jewish Enlightenment. Virtually all ''maskilim'' received old-style, secluded education, and were young Torah scholars before they were first exposed to outside knowledge (from a gender perspective, the movement was almost totally male-dominated; women did not receive sufficient tutoring to master Hebrew). For generations, Mendelssohn's Bible translation to German was employed by such young initiates to bridge the linguistic gap and learn a foreign language, having been raised on Hebrew and Yiddish only. The experience of abandoning one's sheltered community and struggle with tradition was a ubiquitous trait of ''maskilic'' biographies. The children of these activists almost never followed their parents; they rather went forward in the path of acculturation and assimilation. While their fathers learned the vernaculars late and still consumed much Hebrew literature, the little available material in the language did not attract their offspring, who often lacked a grasp of Hebrew due to not sharing their parents' traditional education. ''Haskalah'' was, by and large, a unigenerational experience. In the linguistic field, this transitory nature was well attested. The traditional Jewish community in Europe inhabited two separate spheres of communication: one internal, where Hebrew served as written high language and Yiddish as vernacular for the masses, and one external, where Latin and the like were used for apologetic and intercessory purposes toward the Christian world. A tiny minority of writers was concerned with the latter. The ''Haskalah'' sought to introduce a different bilingualism: renovated, refined Hebrew for internal matters, while Yiddish was to be eliminated; and national vernaculars, to be taught to all Jews, for external ones. However, they insisted on the maintenance of both spheres. When acculturation far exceeded the movement's plans, Central European Jews turned almost solely to the vernacular.David Sorkin

David Sorkin is the Lucy G. Moses professor of Jewish history at Yale University. Sorkin specializes in the intersection of Jewish and European history, and has published several prominent books including ''Jewish Emancipation: A History Across Fiv ...

demonstrated this with the two great journals of German Jewry: the maskilic '' Ha-Me'assef'' was written in Hebrew and supported the study of German; the post-maskilic ''Sulamith'' (published since 1806) was written almost entirely in German, befitting its editors' agenda of linguistic assimilation. Likewise, upon the demise of Jewish Enlightenment in Eastern Europe, authors abandoned the ''maskilic'' paradigm not toward assimilation but in favour of exclusive use of Hebrew and Yiddish.

The political vision of the ''Haskalah'' was predicated on a similar approach. It opposed the reclusive community of the past but sought a maintenance of a strong Jewish framework (with themselves as leaders and intercessors with the state authorities); the Enlightened were not even fully agreeable to civic emancipation, and many of them viewed it with reserve, sometimes anxiety. In their writings, they drew a sharp line between themselves and whom they termed "pseudo-''maskilim''" – those who embraced the Enlightenment values and secular knowledge but did not seek to balance these with their Jewishness, but rather strove for full assimilation. Such elements, whether the radical universalists who broke off the late Berlin ''Haskalah'' or the Russified intelligentsia in Eastern Europe a century later, were castigated and derided no less than the old rabbinic authorities which the movement confronted. It was not uncommon for its partisans to become a conservative element, combating against further dilution of tradition: in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

, Samuel Joseph Fuenn turned from a progressive into an adversary of more radical elements within a generation. In the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

, the few local ''maskilim'' were more concerned with the rapid assimilation of local Jews into the colonial French culture than with the ills of traditional society.

Likewise, those who abandoned the optimistic, liberal vision of the Jews (albeit as a cohesive community) integrating into wider society in favour of full-blown Jewish nationalism or radical, revolutionary ideologies which strove to uproot the established order like Socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

, also broke with the ''Haskalah''. The Jewish national movements of Eastern Europe, founded by disillusioned ''maskilim'', derisively regarded it – in a manner similar to other romantic-nationalist movements' understanding of the general Enlightenment – as a naive, liberal and assimilationist ideology which induced foreign cultural influences, gnawed at the Jewish national consciousness and promised false hopes of equality in exchange for spiritual enslavement. This hostile view was promulgated by nationalist thinkers and historians, from Peretz Smolenskin, Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zi ...

, Simon Dubnow and onwards. It was once common in Israeli historiography.

A major factor which always characterized the movement was its weakness and its dependence of much more powerful elements. Its partisans were mostly impoverished intellectuals, who eked out a living as private tutors and the like; few had a stable financial base, and they required patrons, whether affluent Jews or the state's institutions. This triplice – the authorities, the Jewish communal elite, and the ''maskilim'' – was united only in the ambition of thoroughly reforming Jewish society. The government had no interest in the visions of renaissance which the Enlightened so fervently cherished. It demanded the Jews to turn into productive, loyal subjects with rudimentary secular education, and no more. The rich Jews were sometimes open to the movement's agenda, but mostly practical, hoping for a betterment of their people that would result in emancipation and equal rights. Indeed, the great cultural transformation which occurred among the ''Parnassim'' (affluent communal wardens) class – they were always more open to outside society, and had to tutor their children in secular subjects, thus inviting general Enlightenment influences – was a precondition of ''Haskalah''. The state and the elite required the ''maskilim'' as interlocutors and specialists in their efforts for reform, especially as educators, and the latter used this as leverage to benefit their ideology. However, the activists were much more dependent on the former than vice versa; frustration from one's inability to further the ''maskilic'' agenda and being surrounded by apathetic Jews, either conservative "fanatics" or parvenu "assimilationists", is a common theme in the movement's literature.

The term ''Haskalah'' became synonymous, among friends and foes alike and in much of early Jewish historiography, with the sweeping changes that engulfed Jewish society (mostly in Europe) from the late 18th century to the late 19th century. It was depicted by its partisans, adversaries and historians like Heinrich Graetz as a major factor in those; Feiner noted that "every modern Jew was identified as a ''maskil'' and every change in traditional religious patterns was dubbed ''Haskalah''". Later research greatly narrowed the scope of the phenomenon and limited its importance: while ''Haskalah'' undoubtedly played a part, the contemporary historical consensus portrays it as much humbler. Other transformation agents, from state-imposed schools to new economic opportunities, were demonstrated to have rivaled or overshadowed the movement completely in propelling such processes as acculturation, secularization, religious reform from moderate to extreme, adoption of native patriotism and so forth. In many regions the ''Haskalah'' had no effect at all.

Origins

As long as the Jews lived in segregated communities, and as long as all social interaction with theirgentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

neighbors was limited, the rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

was the most influential member of the Jewish community. In addition to being a religious scholar and "clergy", a rabbi also acted as a civil judge in all cases in which both parties were Jews. Rabbis sometimes had other important administrative powers, together with the community elders. The rabbinate was the highest aim of many Jewish boys, and the study of the Talmud was the means of obtaining that coveted position, or one of many other important communal distinctions. Haskalah followers advocated "coming out of the ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

", not just physically but also mentally and spiritually, in order to assimilate among gentile nations.

The example of Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the '' Haskalah'', or ...

(1729–86), a Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n Jew, served to lead this movement, which was also shaped by Aaron Halle-Wolfssohn Aaron Halle-Wolfssohn (; 1754 or 1756, in probably Halle – 20 March 1835, in Fürth) was a German-Jewish writer, translator, and Biblical commentator. He was a leading writer of the ''Haskalah''.

Biography

He was born in Halle and died in Fü ...

(1754–1835) and Joseph Perl (1773–1839). Mendelssohn's extraordinary success as a popular philosopher and man of letters

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, ei ...

revealed hitherto unsuspected possibilities of integration and acceptance of Jews among non-Jews. Mendelssohn also provided methods for Jews to enter the general society of Germany. A good knowledge of the German language was necessary to secure entrance into cultured German circles, and an excellent means of acquiring it was provided by Mendelssohn in his German translation of the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

. This work became a bridge over which ambitious young Jews could pass to the great world of secular knowledge. The ''Biur'', or grammatical commentary, prepared under Mendelssohn's supervision, was designed to counteract the influence of traditional rabbinical methods of exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

. Together with the translation, it became, as it were, the primer of Haskalah.

Language played a key role in the haskalah movement, as Mendelssohn and others called for a revival of Hebrew and a reduction in the use of Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

. The result was an outpouring of new, secular literature, as well as critical studies of religious text

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

s. Julius Fürst along with other German-Jewish scholars compiled Hebrew and Aramaic dictionaries and grammars. Jews also began to study and communicate in the languages of the countries in which they settled, providing another gateway for integration.

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

was the city of origin for the movement. The capital city of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

and, later, the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, Berlin became known as a secular, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic center, a fertile environment for conversations and radical movements. This move by the Maskilim away from religious study, into much more critical and worldly studies was made possible by this German city of modern and progressive thought. It was a city in which the rising middle class Jews and intellectual elites not only lived among, but were exposed to previous age of enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

thinkers such as Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

, Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

, and Rousseau. The movement is often referred to as the ''Berlin Haskalah''. Reference to Berlin in relation to the Haskalah movement is necessary because it provides context for this episode of Jewish history. Subsequently, having left Germany and spreading across Eastern Europe, the ''Berlin Haskalah'' influenced multiple Jewish communities who were interested in non-religious scholarly texts and insight to worlds beyond their Jewish enclaves.

Spread

Haskalah did not stay restricted to Germany, however, and the movement quickly spread throughout Europe. Poland–Lithuania was the heartland of Rabbinic Judaism, with its two streams of Misnagdic Talmudism centred inLithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

and other regions, and Hasidic

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism ( Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of conte ...

mysticism popular in Ukraine, Poland, Hungary and Russia. In the 19th century, Haskalah sought dissemination and transformation of traditional education and inward pious life in Eastern Europe. It adapted its message to these different environments, working with the Russian government of the Pale of Settlement to influence secular educational methods, while its writers satirised Hasidic mysticism, in favour of solely Rationalist interpretation of Judaism. Isaac Baer Levinsohn

Isaac Baer Levinsohn (; October 13, 1788 – February 13, 1860), also known as the Ribal (), was a Jewish scholar of Hebrew, a satirist, a writer and Haskalah leader. He has been called "the Mendelssohn of Russia." In his ''Bet Yehudah'' (1837), ...

(1788–1860) became known as the "Russian Mendelssohn". Joseph Perl's (1773–1839) satire of the Hasidic movement, "Revealer of Secrets" (Megalleh Temirim), is said to be the first modern novel in Hebrew. It was published in Vienna in 1819 under the pseudonym "Obadiah ben Pethahiah". The Haskalah's message of integration into non-Jewish society was subsequently counteracted by alternative secular Jewish political movements advocating Folkish, Socialist or Nationalist secular Jewish identities in Eastern Europe. While Haskalah advocated Hebrew and sought to remove Yiddish, these subsequent developments advocated Yiddish Renaissance among Maskilim. Writers of Yiddish literature variously satirised or sentimentalised Hasidic mysticism.

Effects

The Haskalah also resulted in the creation of a secular Jewish culture, with an emphasis on Jewish history andJewish identity

Jewish identity is the objective or subjective state of perceiving oneself as a Jew and as relating to being Jewish. Under a broader definition, Jewish identity does not depend on whether a person is regarded as a Jew by others, or by an exte ...

, rather than on religion. This, in turn, resulted in the political engagement of Jews in a variety of competing ways within the countries where they lived on issues that included

* the struggle for Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It in ...

* involvement in new Jewish political movements, and

* later (in the face of continued persecutions in late nineteenth-century Europe), the development of Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

.

One commentator describes these effects as "The emancipation of the Jews brought forth two opposed movements: the cultural assimilation, begun by Moses Mendelssohn, and Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

, founded by Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

in 1896."

One facet of the Haskalah was a widespread cultural adaptation, as those Jews who participated in the enlightenment began, in varying degrees, to participate in the cultural practices of the surrounding gentile population. Connected with this was the birth of the Reform movement

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary m ...

, whose founders (such as Israel Jacobson

Israel Jacobson (17 October 1768, Halberstadt – 14 September 1828, Berlin) was a German-Jewish philanthropist and communal organiser. Jacobson pioneered political, educational and religious reforms in the early days of Jewish emancipation, an ...

and Leopold Zunz

Leopold Zunz ( he, יום טוב צונץ—''Yom Tov Tzuntz'', yi, ליפמן צונץ—''Lipmann Zunz''; 10 August 1794 – 17 March 1886) was the founder of academic Judaic Studies (''Wissenschaft des Judentums''), the critical investigation ...

) rejected the continuing observance of those aspects of Jewish law which they classified as ritual—as opposed to moral or ethical. Even within orthodoxy, the Haskalah was felt through the appearance, in response, of the Mussar Movement in Lithuania, and ''Torah im Derech Eretz

''Torah im Derech Eretz'' ( he, תורה עם דרך ארץ – Torah with "the way of the land"Rabbi Y. Goldson, Aish HaTorah"The Way of the World", Ethics of the Fathers, 3:21/ref>)

is a phrase common in Rabbinic literature referring to vario ...

'' in Germany. "Enlightened" Jews sided with gentile governments, in plans to increase secular education and assimilation among the Jewish masses, which brought them into acute conflict with the orthodox, who believed this threatened the traditional Jewish lifestyle – which had up until that point been maintained through segregation from their gentile neighbors – and Jewish identity itself.

The spread of Haskalah affected Judaism, as a religion, because of the degree to which different sects desired to be integrated, and in turn, integrate their religious traditions. The effects of the Enlightenment were already present in Jewish religious music, and in opinion on the tension between traditionalist and modernist tendencies. Groups of Reform Jews, including the Society of the Friends of Reform and the Association for the Reform of Judaism were formed, because such groups wanted, and actively advocated for, a change in Jewish tradition, in particular, regarding rituals like circumcision. Another non-Orthodox group was the Conservative Jews, who emphasized the importance of traditions but viewed with a historical perspective. The Orthodox Jews were actively against these reformers because they viewed changing Jewish tradition as an insult to God and believed that fulfillment in life could be found in serving God and keeping his commandments. The effect of Haskalah was that it gave a voice to plurality of views, while the orthodoxy preserved the tradition, even to the point of insisting on dividing between sects.

Another important facet of the Haskalah was its interests to non-Jewish religions. Moses Mendelssohn criticized some aspects of Christianity, but depicted Jesus as a Torah-observant rabbi, who was loyal to traditional Judaism. Mendelssohn explicitly linked positive Jewish views of Jesus with the issues of Emancipation and Jewish-Christian reconciliation. Similar revisionist views were expressed by Rabbi Isaac Ber Levinsohn and other traditional representatives of the Haskalah movement.Matthew Baigell and Milly Heyd, eds. ''Complex Identities: Jewish consciousness and modern art''. Rutgers University Press, 2001

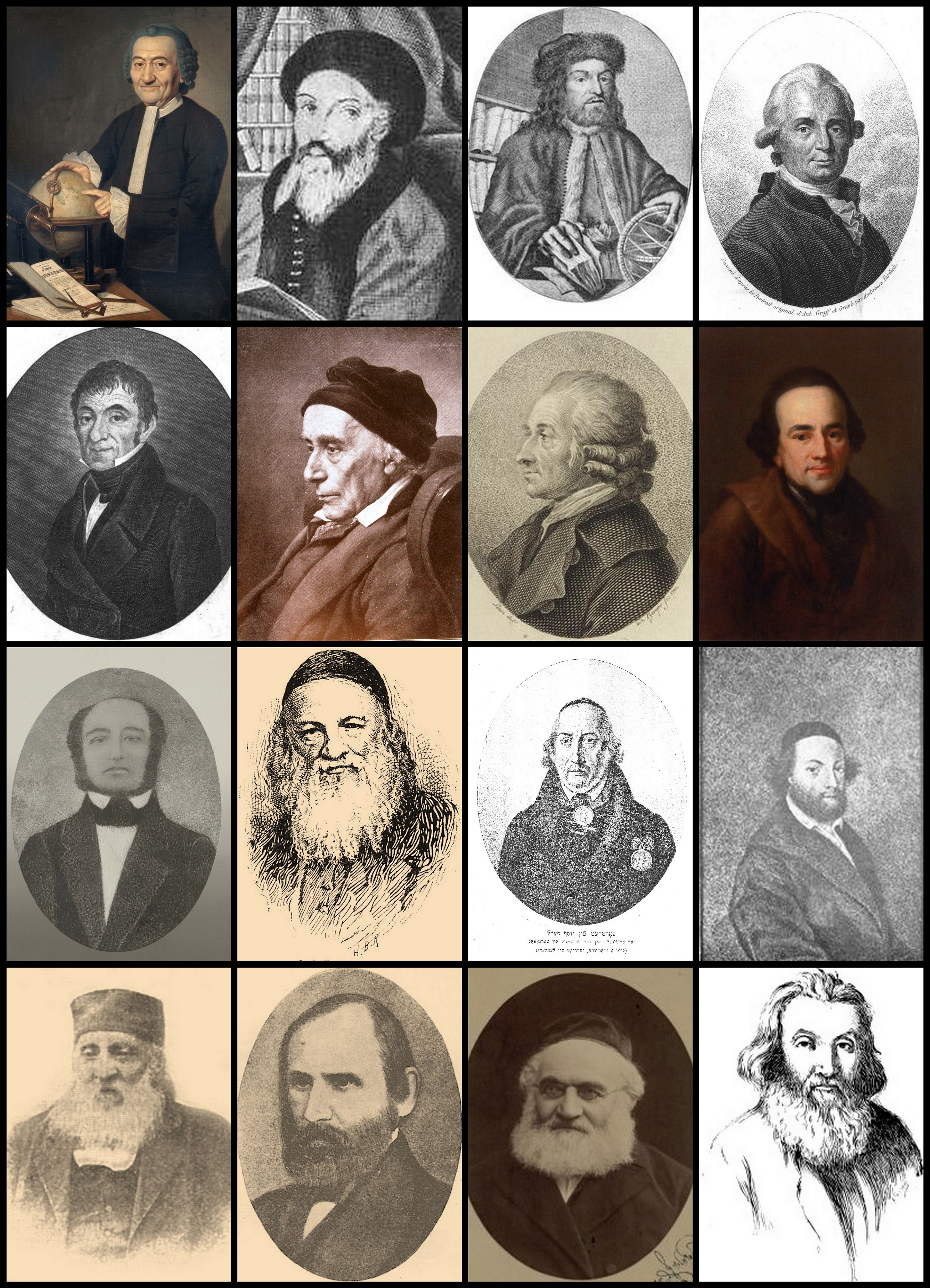

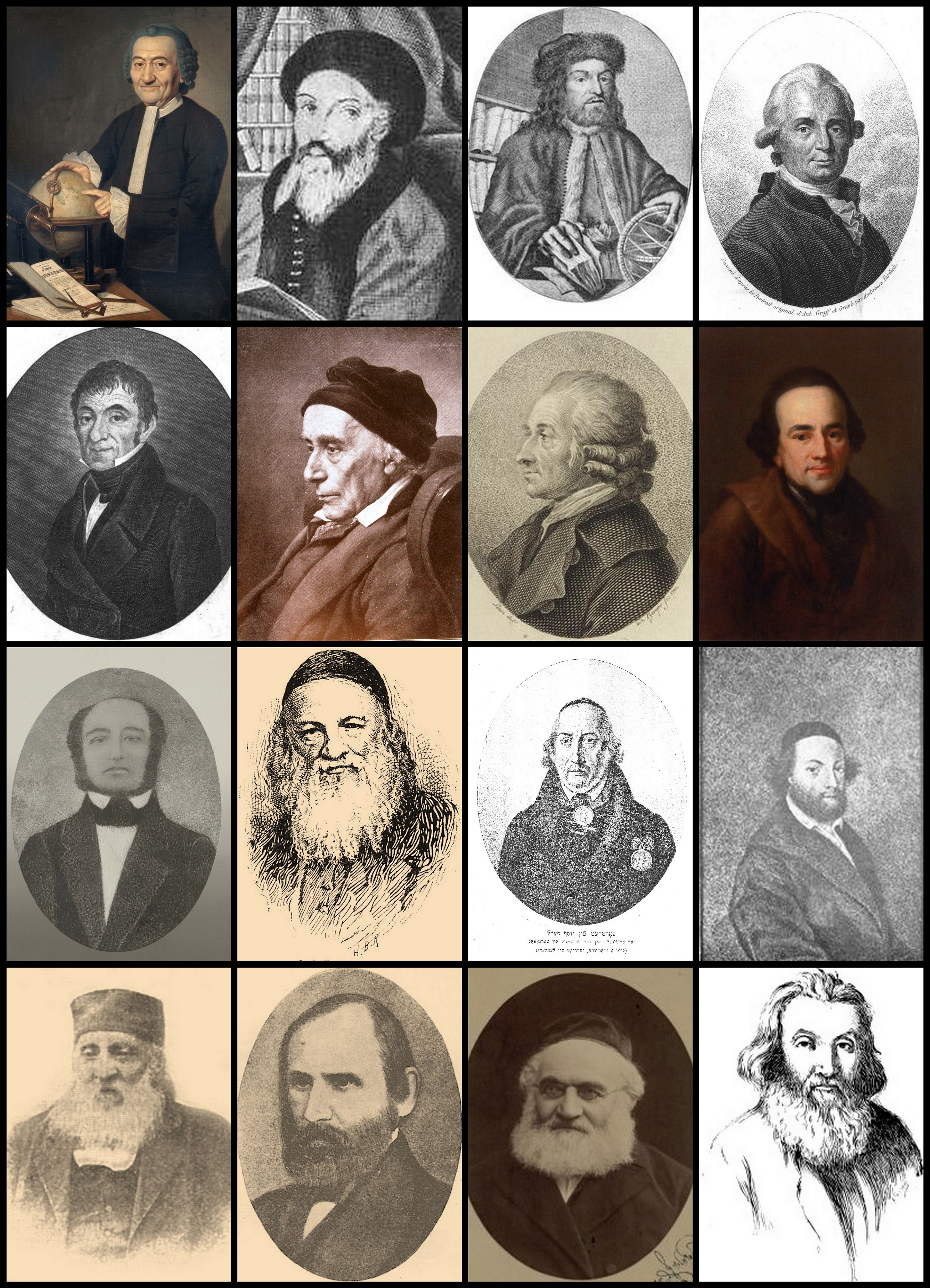

List of Maskilim

* Abraham Dob Bär Lebensohn (~1790–1878) was a Lithuanian Jewish Hebraist, poet, and grammarian. *Abraham Jacob Paperna

Abraham Jacob Paperna ( he, אברהם יעקב פפירנא; 30 August 1840 – 18 February 1919) was a Russian Empire, Russian Jewish educator and author.

Early life and education

Abraham Jacob Paperna was born in 1840 in Kapyl, Minsk Governo ...

(1840–1919) was a Russian Jewish educator and author.

* Aleksander Zederbaum (1816–1893) was a Polish-Russian Jewish journalist. He was founder and editor of ''Ha-Meliẓ'', and other periodicals published in Russian and Yiddish; he wrote in Hebrew.

* Avrom Ber Gotlober (1811–1899) was a Jewish writer, poet, playwright, historian, journalist and educator. He mostly wrote in Hebrew, but also wrote poetry and dramas in Yiddish. His first collection was published in 1835.

* David Friesenhausen (1756–1828), was a Hungarian ''maskil'', mathematician, and rabbi.

* Eliezer Dob Liebermann (1820–1895) was a Russian Hebrew-language writer.

* Ephraim Deinard (1846–1930) was one of the greatest Hebrew 'bookmen' of all time. He was a bookseller, bibliographer, publicist, polemicist, historian, memoirist, author, editor and publisher.

* Isaac Bär Levinsohn (noted in the Haskalah article)

* Isaac ben Jacob Benjacob (1801–1863) was a Russian bibliographer, author, and publisher. His parents moved to Vilnius when he was still a child, and there he received instruction in Hebrew grammar and rabbinical lore.

* Kalman Schulman (1819–1899) was a Jewish writer who translated various volumes and novels into Hebrew.

See also

*Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

* Saul Ascher

Saul Ascher (6 February 1767 in Berlin – 8 December 1822 in Berlin) was a German writer, translator and bookseller.

Life

Saul Ascher (born Saul ben Anschel Jaff), was the first child of Deiche Aaron (c. 1744 Frankfurt – 1820 Berlin) and ...

Notes

References

Resources > Modern Period > Central and Western Europe (17th\18th Cent.) > Enlightenment (Haskala)

The Jewish History Resource Center – Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The

Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; he, הַאוּנִיבֶרְסִיטָה הַעִבְרִית בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם) is a public research university based in Jerusalem, Israel. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Dr. Chaim Weiz ...

Rashi by Maurice Liber

Discusses Rashi's influence on Moses Mendelssohn and the Haskalah.

* * *Rasplus, Valéry "Les judaïsmes à l'épreuve des Lumières. Les stratégies critiques de la Haskalah", in: ''ContreTemps'', n° 17, septembre 2006 * * Digital version available at '' European History Online''

* (translated from ''Oświecenie żydowskie w Królestwie Polskim wobec chasydyzmu'') * Brinker, Menahem (2008)

The Unique Case of Jewish Secularism

(audio archive giving history of ideas of the Haskalah movement and its later secular offshoot movements), London Jewish Book Week. *

External links

Haskalah

at The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

Map of the spread of Haskalah

Haskalah collection

John Rylands Library, University of Manchester {{Authority control Hebrew words and phrases Jewish movements