Giant Tube Worm on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Riftia pachyptila'', commonly known as the giant tube worm and less commonly known as the Giant beardworm, is a marine

Isolating the vermiform body from white chitinous tube, a small difference exists from the classic three subdivisions typical of phylum Pogonophora: the prosoma, the

Isolating the vermiform body from white chitinous tube, a small difference exists from the classic three subdivisions typical of phylum Pogonophora: the prosoma, the  The first body region is the

The first body region is the

AMP + SO3^2- -> PSreductaseAPS

* APS + PPi -> TP sulfurylaseATP + SO4^2-

The electrons released during the entire sulfide-oxidation process enter in an electron transport chain, yielding a proton gradient that produces ATP ( oxydative phosphorylation). Thus, ATP generated from oxidative phosphorylation and ATP produced by substrate-level phosphorylation become available for CO2 fixation in Calvin cycle, whose presence has been demonstrated by the presence of two key enzymes of this pathway:

invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

in the phylum Annelida (formerly grouped in phylum Pogonophora and Vestimentifera

Siboglinidae is a family of polychaete annelid worms whose members made up the former phyla Pogonophora and Vestimentifera (the giant tube worms). The family is composed of about 100 species of vermiform creatures which live in thin tubes buried ...

) related to tube worm

A tubeworm is any worm-like sessile invertebrate that anchors its tail to an underwater surface and secretes around its body a mineral tube, into which it can withdraw its entire body.

Tubeworms are found among the following taxa:

* Annelida, the ...

s commonly found in the intertidal

The intertidal zone, also known as the foreshore, is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide (in other words, the area within the tidal range). This area can include several types of habitats with various species ...

and pelagic zones. ''R. pachyptila'' lives on the floor of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

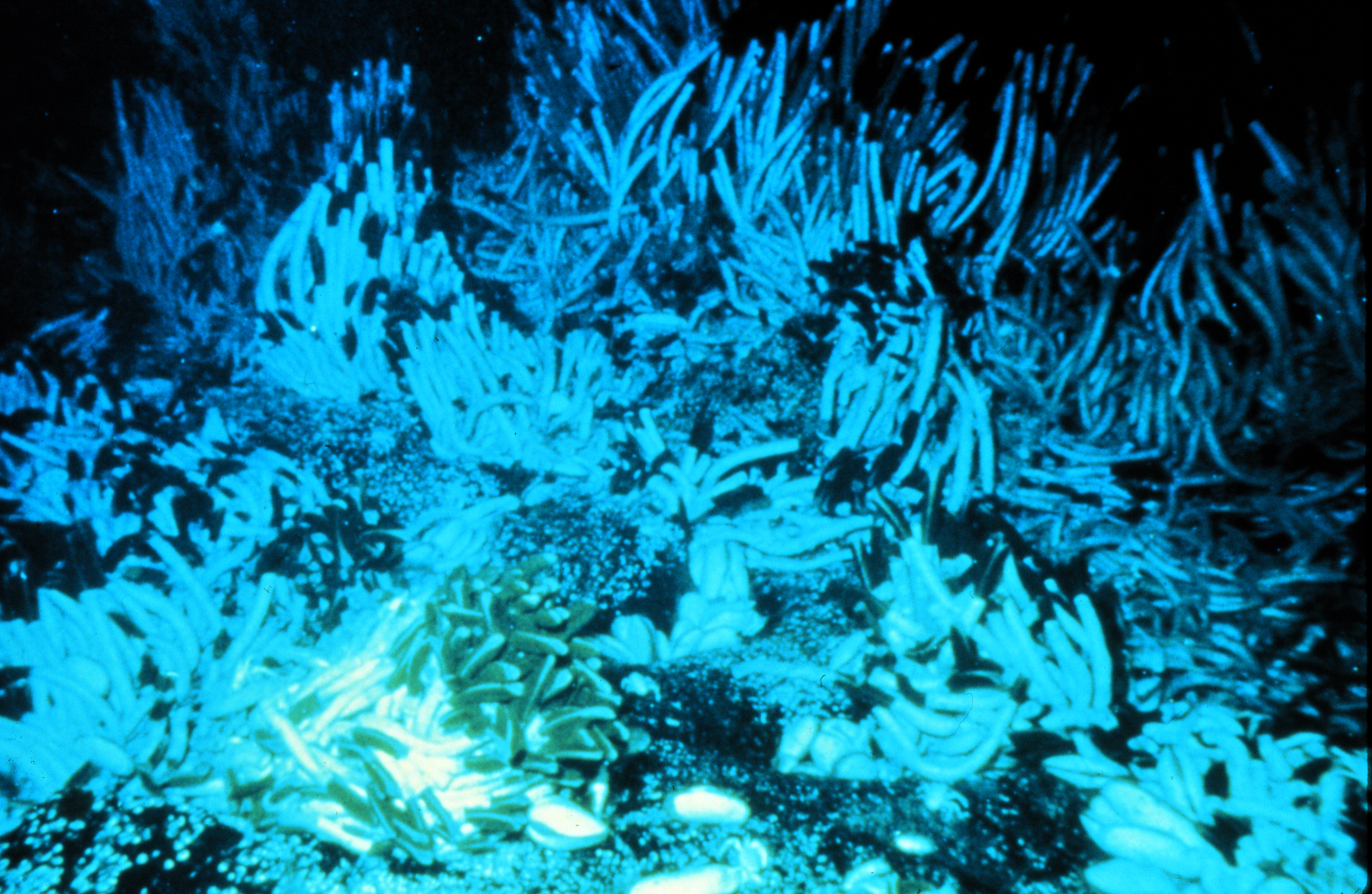

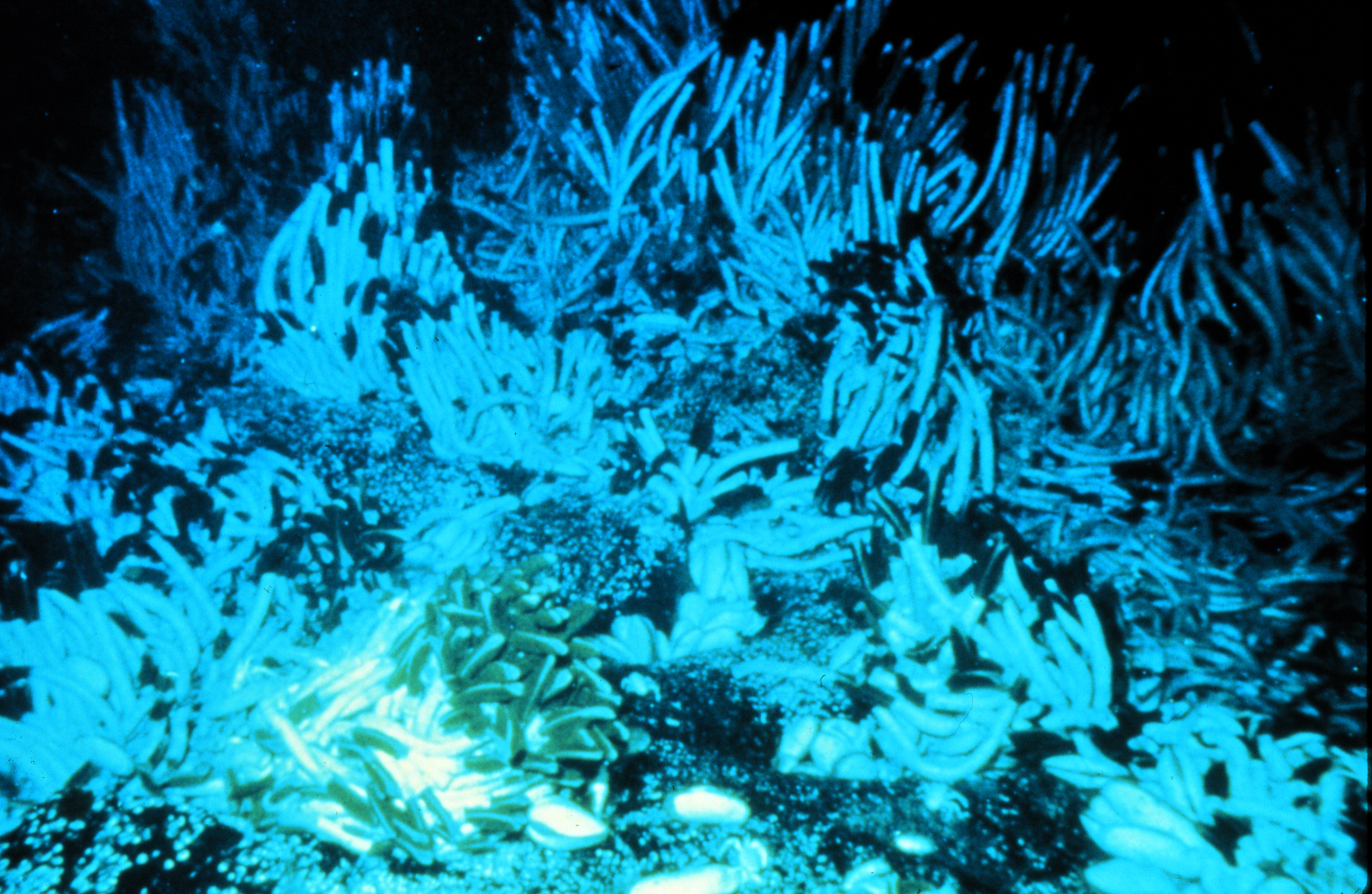

near hydrothermal vents, the vents provide a natural ambient temperature in their environment ranging from 2 to 30 °C, at the same time it can tolerate extremely high hydrogen sulfide levels. These worms can reach a length of , and their tubular bodies have a diameter of .

Its common name "giant tube worm" is, however, also applied to the largest living species of shipworm

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including ...

, ''Kuphus polythalamius

''Kuphus polythalamius'' is a species of shipworm, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Teredinidae.

Description

The tube of ''Kuphus polythalamius'' is known as a crypt and is a calcareous secretion designed to enable the animal to live in it ...

'', which despite the name "worm", is a bivalve mollusc rather than an annelid.

Discovery

''R. pachyptila'' was discovered in 1977 on an expedition of the American bathyscaphe DSV ''Alvin'' to the Galápagos Rift led by geologistJack Corliss

John B. ("Jack") Corliss is a scientist who has worked in the fields of geology, oceanography, and the origins of life.

Corliss is a University of California, San Diego Alumnus, receiving his PhD from Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the ...

. The discovery was unexpected, as the team was studying hydrothermal vents and no biologists were included in the expedition. Many of the species found living near hydrothermal vents during this expedition had never been seen before.

At the time, the presence of thermal springs near the midoceanic ridges was known. Further research uncovered aquatic life in the area, despite the high temperature (around 350–380 °C).

Many samples were collected, for example, bivalves, polychaetes, large crabs, and ''R. pachyptila''. It was the first time that species was observed.

Development

''R. pachyptila'' develops from a free-swimming,pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or w ...

, nonsymbiotic trochophore

A trochophore (; also spelled trocophore) is a type of free-swimming planktonic marine larva with several bands of cilia.

By moving their cilia rapidly, they make a water eddy, to control their movement, and to bring their food closer, to captur ...

larva, which enters juvenile (metatrochophore

A metatrochophore (;) is a type of larva developed from the trochophore larva of a polychaete annelid

The annelids (Annelida , from Latin ', "little ring"), also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant sp ...

) development, becoming sessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

, and subsequently acquiring symbiotic bacteria. The symbiotic bacteria, on which adult worms depend for sustenance, are not present in the gametes, but are acquired from the environment through the skin in a process akin to an infection. The digestive tract transiently connects from a mouth at the tip of the ventral medial process to a foregut, midgut, hindgut, and anus and was previously thought to have been the method by which the bacteria are introduced into adults. After symbionts are established in the midgut, they undergo substantial remodelling and enlargement to become the trophosome, while the remainder of the digestive tract has not been detected in adult specimens.

Body structure

Isolating the vermiform body from white chitinous tube, a small difference exists from the classic three subdivisions typical of phylum Pogonophora: the prosoma, the

Isolating the vermiform body from white chitinous tube, a small difference exists from the classic three subdivisions typical of phylum Pogonophora: the prosoma, the mesosoma

The mesosoma is the middle part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the metasoma. It bears the legs, and, in the case of winged insects, the wings.

In hymenopterans of ...

, and the metasoma

The metasoma is the posterior part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the mesosoma. In insects, it contains most of the digestive tract, respiratory system, and circul ...

.

The first body region is the

The first body region is the vascularized

Angiogenesis is the physiological process through which new blood vessels form from pre-existing vessels, formed in the earlier stage of vasculogenesis. Angiogenesis continues the growth of the vasculature by processes of sprouting and splitt ...

branchial plume, which is bright red due to the presence of hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyt ...

that contain up to 144 globin chains (each presumably including associated heme structures). These tube worm hemoglobins are remarkable for carrying oxygen in the presence of sulfide, without being inhibited by this molecule, as hemoglobins in most other species are. The plume provides essential nutrients to bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometr ...

living inside the trophosome A trophosome is a highly vascularised organ found in some animals that houses symbiotic bacteria that provide food for their host. Trophosomes are located in the coelomic cavity in the vestimentiferan tube worms (Siboglinidae, e.g. the giant tube wo ...

. If the animal perceives a threat or is touched, it retracts the plume and the tube is closed due to the obturaculum, a particular operculum that protects and isolates the animal from the external environment.

The second body region is the vestimentum, formed by muscle bands, having a winged shape, and it presents the two genital openings at the end. The heart, extended portion of dorsal vessel, enclose the vestimentum.

In the middle part, the trunk or third body region, is full of vascularized solid tissue, and includes body wall, gonads, and the coelomic

A body cavity is any space or compartment, or potential space, in an animal body. Cavities accommodate organs and other structures; cavities as potential spaces contain fluid.

The two largest human body cavities are the ventral body cavity, and ...

cavity. Here is located also the trophosome, spongy tissue where a billion symbiotic, thioautotrophic bacteria and sulfur granules are found. Since the mouth, digestive system, and anus are missing, the survival of ''R. pachyptila'' is dependent on this mutualistic symbiosis. This process, known as chemosynthesis

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

, was recognized within the trophosome by Colleen Cavanaugh.

The soluble hemoglobins, present in the tentacles, are able to bind O2 and H2S, which are necessary for chemosynthetic bacteria. Due to the capillaries, these compounds are absorbed by bacteria. During the chemosynthesis, the mitochondrial enzyme rhodanase

Rhodanese, also known as rhodanase, thiosulfate sulfurtransferase, thiosulfate cyanide transsulfurase, and thiosulfate thiotransferase, ...

catalyzes the disproportionation reaction of the thiosulfate anion S2O32- to sulfur S and sulfite SO32- . The ''R. pachyptila''’s bloodstream is responsible for absorption of the O2 and nutrients such as carbohydrates.

Nitrate and nitrite are toxic, but are required for biosynthetic processes. The chemosynthetic bacteria within the trophosome convert nitrate to ammonium ions, which then are available for production of amino acids in the bacteria, which are in turn released to the tube worm. To transport nitrate to the bacteria, ''R. pachyptila'' concentrates nitrate in its blood, to a concentration 100 times more concentrated than the surrounding water. The exact mechanism of ''R. pachyptila''’s ability to withstand and concentrate nitrate is still unknown.

In the posterior part, the fourth body region, is the opistosome, which anchors the animal to the tube and is used for the storage of waste from bacterial reactions.

Symbiosis

The discovery of bacterial invertebrate chemoautotrophic symbiosis, particularly in vestimentiferan tubeworms ''R. pachyptila'' and then in vesicomyid clams and mytilid mussels revealed the chemoautotrophic potential of the hydrothermal vent tube worm. Scientists discovered a remarkable source of nutrition that helps to sustain the conspicuous biomass of invertebrates at vents. Many studies focusing on this type of symbiosis revealed the presence of chemoautotrophic, endosymbiotic, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria mainly in ''R. pachyptila'', which inhabits extreme environments and is adapted to the particular composition of the mixed volcanic and sea waters. This special environment is filled with inorganic metabolites, essentially carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur. In its adult phase, ''R. pachyptila'' lacks a digestive system. To provide its energetic needs, it retains those dissolved inorganic nutrients (sulfide, carbon dioxide, oxygen, nitrogen) into its plume and transports them through a vascular system to the trophosome, which is suspended in paired coelomic cavities and is where the intracellular symbiotic bacteria are found. Thetrophosome A trophosome is a highly vascularised organ found in some animals that houses symbiotic bacteria that provide food for their host. Trophosomes are located in the coelomic cavity in the vestimentiferan tube worms (Siboglinidae, e.g. the giant tube wo ...

is a soft tissue that runs through almost the whole length of the tube's coelom. It retains a large number of bacteria on the order of 109 bacteria per gram of fresh weight. Bacteria in the trophosome are retained inside bacteriocytes, thereby having no contact with the external environment. Thus, they rely on ''R. pachyptila'' for the assimilation of nutrients needed for the array of metabolic reactions they employ and for the excretion of waste products of carbon fixation pathways. At the same time, the tube worm depends completely on the microorganisms for the byproducts of their carbon fixation cycles that are needed for its growth.

Initial evidence for a chemoautotrophic symbiosis in ''R. pachyptila'' came from microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded as the scale be ...

and biochemical analyses showing Gram-negative bacteria packed within a highly vascularized organ in the tubeworm trunk called the trophosome. Additional analyses involving stable isotope, enzymatic

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. ...

, and physiological characterizations confirmed that the end symbionts of ''R. pachyptila'' oxidize reduced-sulfur compounds to synthesize ATP for use in autotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Wo ...

ic carbon fixation through the Calvin cycle. The host tubeworm enables the uptake and transport of the substrates required for thioautotrophy, which are HS−, O2, and CO2, receiving back a portion of the organic matter synthesized by the symbiont population. The adult tubeworm, given its inability to feed on particulate matter and its entire dependency on its symbionts for nutrition, the bacterial population is then the primary source of carbon acquisition for the symbiosis. Discovery of bacterial–invertebrate chemoautotrophic symbioses, initially in vestimentiferan tubeworms and then in vesicomyid clams and mytilid mussels, pointed to an even more remarkable source of nutrition sustaining the invertebrates at vents.

Endosymbiosis with chemoautotrophic bacteria

A wide range of bacterial diversity is associated with symbiotic relationships with ''R. pachyptila''. Many bacteria belong to the phylumCampylobacterota

Campylobacterota are a phylum of bacteria. All species of this phylum are Gram-negative.

The Campylobacterota consist of few known genera, mainly the curved to spirilloid ''Wolinella'' spp., ''Helicobacter'' spp., and ''Campylobacter'' spp. Most ...

(formerly class Epsilonproteobacteria) as supported by the recent discovery in 2016 of the new species ''Sulfurovum riftiae'' belonging to the phylum Campylobacterota, family Helicobacteraceae isolated from ''R. pachyptila'' collected from the East Pacific Rise

The East Pacific Rise is a mid-ocean rise (termed an oceanic rise and not a mid-ocean ridge due to its higher rate of spreading that results in less elevation increase and more regular terrain), a divergent tectonic plate boundary located alon ...

. Other symbionts belong to the class Delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), a letter of the Greek alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* D ( NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta")

* Delta Air Lines, US

* Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19

Delta may also ...

-, Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria. The ''Candidatus'' Endoriftia persephone (Gammaproteobacteria) is a facultative ''R. pachyptila'' symbiont and has been shown to be a mixotroph A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comp ...

, thereby exploiting both Calvin Benson cycle and reverse TCA cycle (with an unusual ATP citrate lyase

ATP citrate synthase (also ATP citrate lyase (ACLY)) is an enzyme that in animals represents an important step in fatty acid biosynthesis. By converting citrate to acetyl-CoA, the enzyme links carbohydrate metabolism, which yields citrate as an ...

) according to availability of carbon resources and whether it is free living in the environment or inside a eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the ...

host. The bacteria apparently prefer a heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

ic lifestyle when carbon sources are available.

Evidence based on 16S rRNA 16S rRNA may refer to:

* 16S ribosomal RNA

16 S ribosomal RNA (or 16 S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome ( SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The g ...

analysis affirms that ''R. pachyptila'' chemoautotrophic bacteria belong to two different clades: Gammaproteobacteria and Campylobacterota

Campylobacterota are a phylum of bacteria. All species of this phylum are Gram-negative.

The Campylobacterota consist of few known genera, mainly the curved to spirilloid ''Wolinella'' spp., ''Helicobacter'' spp., and ''Campylobacter'' spp. Most ...

(e.g. ''Sulfurovum riftiae'') that get energy from the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

of inorganic sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S, HS−, S2-) to synthetize ATP for carbon fixation via the Calvin cycle. Unfortunately, most of these bacteria are still uncultivable. Symbiosis works so that ''R. pachyptila'' provides nutrients such as HS−, O2, CO2 to bacteria, and in turn it receives organic matter from them. Thus, because of lack of a digestive system, ''R. pachyptila'' depends entirely on its bacterial symbiont to survive.

In the first step of sulfide-oxidation, reduced sulfur (HS−) passes from the external environment into ''R. pachyptila'' blood, where, together with O2, it is bound by hemoglobin, forming the complex Hb-O2-HS− and then it is transported to the trophosome, where bacterial symbionts reside. Here, HS− is oxidized to elemental sulfur (S0) or to sulfite (SO32-).

In the second step, the symbionts make sulfite-oxidation by the "APS pathway", to get ATP. In this biochemical pathway, AMP reacts with sulfite in the presence of the enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

APS reductase, giving APS (adenosine 5'-phosphosulfate). Then, APS reacts with the enzyme ATP sulfurylase in presence of pyrophosphate

In chemistry, pyrophosphates are phosphorus oxyanions that contain two phosphorus atoms in a P–O–P linkage. A number of pyrophosphate salts exist, such as disodium pyrophosphate (Na2H2P2O7) and tetrasodium pyrophosphate (Na4P2O7), among othe ...

(PPi) giving ATP ( substrate-level phosphorylation) and sulfate (SO42-) as end products. In formulas:

* phosphoribulokinase Phosphoribulokinase (PRK) () is an essential photosynthetic enzyme that catalyzes the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of ribulose 5-phosphate (RuP) into ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP), both intermediates in the Calvin Cycle. Its main function is ...

and RubisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase, commonly known by the abbreviations RuBisCo, rubisco, RuBPCase, or RuBPco, is an enzyme () involved in the first major step of carbon fixation, a process by which atmospheric carbon dioxide is con ...

.

To support this unusual metabolism, ''R. pachyptila'' has to absorb all the substances necessary for both sulfide-oxidation and carbon fixation, that is: HS−, O2 and CO2 and other fundamental bacterial nutrients such as N and P. This means that the tubeworm must be able to access both oxic and anoxic areas.

Oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds requires the presence of oxidized reagents such as oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

and nitrate. Hydrothermal vents are characterized by conditions of high hypoxia. In hypoxic conditions, sulfur-storing organisms start producing hydrogen sulfide. Therefore, the production of in H2S in anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

* Anaerobic adhesive, a bonding a ...

conditions is common among thiotrophic symbiosis. H2S can be damaging for some physiological processes as it inhibits the activity of cytochrome c oxidase

The enzyme cytochrome c oxidase or Complex IV, (was , now reclassified as a translocasEC 7.1.1.9 is a large transmembrane protein complex found in bacteria, archaea, and mitochondria of eukaryotes.

It is the last enzyme in the respiratory elect ...

, consequentially impairing oxidative phosphorilation. In ''R. pachyptila'' the production of hydrogen sulfide starts after 24h of hypoxia. In order to avoid physiological damage some animals, including ''Riftia'' ''pachyptila'' are able to bind H2S to haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

in the blood to eventually expel it in the surrounding environment

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

.

Carbon fixation and organic carbon assimilation

Unlikemetazoans

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage in ...

, which respire carbon dioxide as a waste product, ''R. pachyptila''-symbiont association has a demand for a net uptake of CO2 instead, as a cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that ...

n-symbiont associations.

Ambient deep-sea water contains an abundant amount of inorganic carbon in the form of bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial biochem ...

HCO3−, but it is actually the chargeless form of inorganic carbon, CO2, that is easily diffusible across membranes. The low partial pressures of CO2 in the deep-sea environment is due to the seawater alkaline pH and the high solubility of CO2, yet the pCO2 of the blood of ''R. pachyptila'' may be as much as two orders of magnitude greater than the pCO2 of deep-sea water.

CO2 partial pressures are transferred to the vicinity of vent fluids due to the enriched inorganic carbon content of vent fluids and their lower pH. CO2 uptake in the worm is enhanced by the higher pH of its blood (7.3–7.4), which favors the bicarbonate ion and thus promotes a steep gradient across which CO2 diffuses into the vascular blood of the plume. The facilitation of CO2 uptake by high environmental pCO2 was first inferred based on measures of elevated blood and coelomic fluid pCO2 in tubeworms, and was subsequently demonstrated through incubations of intact animals under various pCO2 conditions.

Once CO2 is fixed by the symbionts, it must be assimilated by the host tissues. The supply of fixed carbon to the host is transported via organic molecules from the trophosome in the hemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, analogous to the blood in vertebrates, that circulates in the interior of the arthropod (invertebrate) body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which ...

, but the relative importance of translocation and symbiont digestion is not yet known. Studies proved that within 15 min, the label first appears in symbiont-free host tissues, and that indicates a significant amount of release of organic carbon immediately after fixation. After 24 h, labeled carbon is clearly evident in the epidermal tissues of the body wall. Results of the pulse-chase autoradiograph

An autoradiograph is an image on an X-ray film or nuclear emulsion produced by the pattern of decay emissions (e.g., beta particles or gamma rays) from a distribution of a radioactive substance. Alternatively, the autoradiograph is also available ...

ic experiments were also evident with ultrastructural evidence for digestion of symbionts in the peripheral regions of the trophosome lobules.

Sulfide acquisition

In deep-sea hydrothermal vents, sulfide andoxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

are present in different areas. Indeed, the reducing fluid of hydrothermal vents is rich in sulfide, but poor in oxygen, whereas sea water is richer in dissolved oxygen. Moreover, sulfide is immediately oxidized by dissolved oxygen to form partly, or totally, oxidized sulfur compounds like thiosulfate

Thiosulfate ( IUPAC-recommended spelling; sometimes thiosulphate in British English) is an oxyanion of sulfur with the chemical formula . Thiosulfate also refers to the compounds containing this anion, which are the salts of thiosulfuric acid, ...

(S2O32-) and ultimately sulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

(SO42-), respectively less, or no longer, usable for microbial oxidation metabolism. This causes the substrates to be less available for microbial activity, thus bacteria are constricted to compete with oxygen to get their nutrients. In order to avoid this issue, several microbes have evolved to make symbiosis with eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the ...

hosts. In fact, ''R. pachyptila'' is able to cover the oxic

{{Short pages monitor

Fauna of the Pacific Ocean

Animals described in 1981

Chemosynthetic symbiosis

Animals living on hydrothermal vents