Gaseous diffusion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce

U.S. DOE Gaseous Diffusion Plant

''Operation of the GDP by USEC ceased operation in 2013'' The only other such facility in the United States, the Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Ohio, ceased enrichment activities in 2001. Since 2010, the Ohio site is now used mainly by AREVA, a French conglomerate, for the conversion of depleted UF6 to

Annotated references on gaseous diffusion from the Alsos Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gaseous Diffusion Isotope separation Uranium Membrane technology

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through semipermeable membrane

Semipermeable membrane is a type of biological or synthetic, polymeric membrane that will allow certain molecules or ions to pass through it by osmosis. The rate of passage depends on the pressure, concentration, and temperature of the molecul ...

s. This produces a slight separation between the molecules containing uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

(235U) and uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

(238U). By use of a large cascade

Cascade, Cascades or Cascading may refer to:

Science and technology Science

* Cascade waterfalls, or series of waterfalls

* Cascade, the CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defense (a protein complex)

* Cascade (grape), a type of fruit

* Bioc ...

of many stages, high separations can be achieved. It was the first process to be developed that was capable of producing enriched uranium in industrially useful quantities, but is nowadays considered obsolete, having been superseded by the more-efficient gas centrifuge

A gas centrifuge is a device that performs isotope separation of gases. A centrifuge relies on the principles of centrifugal force accelerating molecules so that particles of different masses are physically separated in a gradient along the radiu ...

process.

Gaseous diffusion was devised by Francis Simon

Sir Francis Simon (2 July 1893 – 31 October 1956), was a German and later British physical chemist and physicist who devised the gaseous diffusion method, and confirmed its feasibility, of separating the isotope Uranium-235 and thus made a m ...

and Nicholas Kurti at the Clarendon Laboratory

The Clarendon Laboratory, located on Parks Road within the Science Area in Oxford, England (not to be confused with the Clarendon Building, also in Oxford), is part of the Department of Physics at Oxford University. It houses the atomic and ...

in 1940, tasked by the MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was a British scientific working group formed during the Second World War. It was established to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible. The name MAUD came from a strange line in a telegram fro ...

with finding a method for separating uranium-235 from uranium-238 in order to produce a bomb for the British Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the ...

project. The prototype gaseous diffusion equipment itself was manufactured by Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

(MetroVick) at Trafford Park

Trafford Park is an area of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, Greater Manchester, England, opposite Salford Quays on the southern side of the Manchester Ship Canal, southwest of Manchester city centre and north of Stretford. Until the l ...

, Manchester, at a cost of £150,000 for four units, for the M. S. Factory, Valley

The M.S. (Ministry of Supply) Factory, Valley was a Second World War site in Rhydymwyn, Flintshire, Wales, that was used for the storage and production of mustard gas. It was later also used in the development of the UK's atomic bomb project. Mor ...

. This work was later transferred to the United States when the Tube Alloys project became subsumed by the later Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

.

Background

Of the 33 known radioactive primordial nuclides, two (235U and 238U) areisotopes of uranium

Uranium (92U) is a naturally occurring radioactive element that has no stable isotope. It has two primordial isotopes, uranium-238 and uranium-235, that have long half-lives and are found in appreciable quantity in the Earth's crust. The d ...

. These two isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass num ...

s are similar in many ways, except that only 235U is fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be t ...

(capable of sustaining a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

with thermal neutrons

The neutron detection temperature, also called the neutron energy, indicates a free neutron's kinetic energy, usually given in electron volts. The term ''temperature'' is used, since hot, thermal and cold neutrons are moderated in a medium wi ...

). In fact, 235U is the only naturally occurring fissile nucleus. Because natural uranium

Natural uranium (NU or Unat) refers to uranium with the same isotopic ratio as found in nature. It contains 0.711% uranium-235, 99.284% uranium-238, and a trace of uranium-234 by weight (0.0055%). Approximately 2.2% of its radioactivity comes ...

is only about 0.72% 235U by mass, it must be enriched to a concentration of 2–5% to be able to support a continuous nuclear chain reaction when normal water is used as the moderator. The product of this enrichment process is called enriched uranium.

Technology

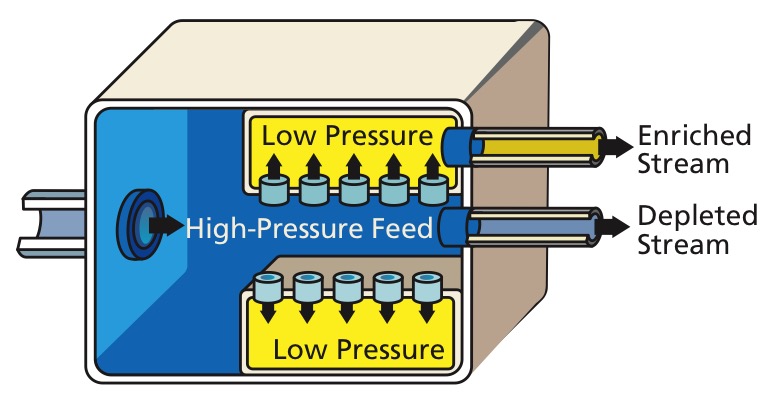

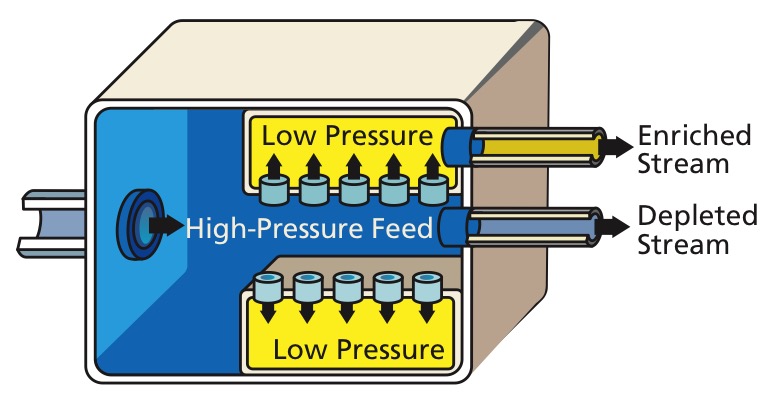

;Scientific basis Gaseous diffusion is based onGraham's law

Graham's law of effusion (also called Graham's law of diffusion) was formulated by Scottish physical chemist Thomas Graham in 1848.Keith J. Laidler and John M. Meiser, ''Physical Chemistry'' (Benjamin/Cummings 1982), pp. 18–19 Graham found ...

, which states that the rate of effusion

In physics and chemistry, effusion is the process in which a gas escapes from a container through a hole of diameter considerably smaller than the mean free path of the molecules. Such a hole is often described as a ''pinhole'' and the escap ...

of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of its molecular mass

The molecular mass (''m'') is the mass of a given molecule: it is measured in daltons (Da or u). Different molecules of the same compound may have different molecular masses because they contain different isotopes of an element. The related quant ...

. For example, in a box with a semi-permeable membrane containing a mixture of two gases, the lighter molecules will pass out of the container more rapidly than the heavier molecules. The gas leaving the container is somewhat enriched in the lighter molecules, while the residual gas is somewhat depleted. A single container wherein the enrichment process takes place through gaseous diffusion is called a diffuser

Diffuser may refer to:

Aerodynamics

* Diffuser (automotive), a shaped section of a car's underbody which improves the car's aerodynamic properties

* Part of a jet engine air intake, especially when operated at supersonic speeds

* The channel bet ...

.

;Uranium hexafluoride

UF6 is the only compound of uranium sufficiently volatile to be used in the gaseous diffusion process. Fortunately, fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element with the symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at standard conditions as a highly toxic, pale yellow diatomic gas. As the most electronegative reactive element, it is extremely reactiv ...

consists of only a single isotope 19F, so that the 1% difference in molecular weights between 235UF6 and 238UF6 is due only to the difference in weights of the uranium isotopes. For these reasons, UF6 is the only choice as a feedstock

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feeds ...

for the gaseous diffusion process. UF6, a solid at room temperature, sublimes at 56.5 °C (133 °F) at 1 atmosphere. The triple point

In thermodynamics, the triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium.. It is that temperature and pressure at which the ...

is at 64.05 °C and 1.5 bar. Applying Graham's Law to uranium hexafluoride:

:

where:

:''Rate1'' is the rate of effusion of 235UF6.

:''Rate2'' is the rate of effusion of 238UF6.

:''M1'' is the molar mass

In chemistry, the molar mass of a chemical compound is defined as the mass of a sample of that compound divided by the amount of substance which is the number of moles in that sample, measured in moles. The molar mass is a bulk, not molecular, ...

of 235UF6 = 235.043930 + 6 × 18.998403 = 349.034348 g·mol−1

:''M2'' is the molar mass of 238UF6 = 238.050788 + 6 × 18.998403 = 352.041206 g·mol−1

This explains the 0.4% difference in the average velocities of 235UF6 molecules over that of 238UF6 molecules.

UF6 is a highly corrosive substance

A corrosive substance is one that will damage or destroy other substances with which it comes into contact by means of a chemical reaction.

Etymology

The word ''corrosive'' is derived from the Latin verb ''corrodere'', which means ''to gnaw'', ...

. It is an oxidant

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ). In other words, an oxi ...

and a Lewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

which is able to bind to fluoride

Fluoride (). According to this source, is a possible pronunciation in British English. is an inorganic, monatomic anion of fluorine, with the chemical formula (also written ), whose salts are typically white or colorless. Fluoride salts ty ...

, for instance the reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

* Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

*Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and m ...

of copper(II) fluoride with uranium hexafluoride in acetonitrile

Acetonitrile, often abbreviated MeCN (methyl cyanide), is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . This colourless liquid is the simplest organic nitrile ( hydrogen cyanide is a simpler nitrile, but the cyanide anion is not clas ...

is reported to form copper(II) heptafluorouranate(VI), Cu(UF7)2. It reacts with water to form a solid compound, and is very difficult to handle on an industrial scale. As a consequence, internal gaseous pathways must be fabricated from austenitic stainless steel

Austenitic stainless steel is one of the five classes of stainless steel by crystalline structure (along with ''ferritic'', '' martensitic, duplex and precipitation hardened''). Its primary crystalline structure is austenite (face-centered cubic ...

and other heat-stabilized metals. Non-reactive fluoropolymer

A fluoropolymer is a fluorocarbon-based polymer with multiple carbon–fluorine bonds. It is characterized by a high resistance to solvents, acids, and bases. The best known fluoropolymer is polytetrafluoroethylene under the brand name "Tefl ...

s such as Teflon

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is a synthetic fluoropolymer of tetrafluoroethylene that has numerous applications. It is one of the best-known and widely applied PFAS. The commonly known brand name of PTFE-based composition is Teflon by Chemo ...

must be applied as a coating

A coating is a covering that is applied to the surface of an object, usually referred to as the substrate. The purpose of applying the coating may be decorative, functional, or both. Coatings may be applied as liquids, gases or solids e.g. Pow ...

to all valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fitting ...

s and seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

in the system.

;Barrier materials

Gaseous diffusion plants typically use aggregate barriers (porous membranes) constructed of sintered

Clinker nodules produced by sintering

Sintering or frittage is the process of compacting and forming a solid mass of material by pressure or heat without melting it to the point of liquefaction.

Sintering happens as part of a manufacturing ...

nickel or aluminum

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It ha ...

, with a pore size of 10–25 nanometers

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the molecular scale.

The nanometre (international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: nm) or nanometer (American and British English spelling differences#-re ...

(this is less than one-tenth the mean free path

In physics, mean free path is the average distance over which a moving particle (such as an atom, a molecule, or a photon) travels before substantially changing its direction or energy (or, in a specific context, other properties), typically as ...

of the UF6 molecule). They may also use film-type barriers, which are made by boring pores through an initially nonporous medium. One way this can be done is by removing one constituent in an alloy, for instance using hydrogen chloride

The compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colourless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hydrogen chlorid ...

to remove the zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

from silver-zinc (Ag-Zn).

;Energy requirements

Because the molecular weights of 235UF6 and 238UF6 are nearly equal, very little separation of the 235U and 238U occurs in a single pass through a barrier, that is, in one diffuser. It is therefore necessary to connect a great many diffusers together in a sequence of stages, using the outputs of the preceding stage as the inputs for the next stage. Such a sequence of stages is called a ''cascade''. In practice, diffusion cascades require thousands of stages, depending on the desired level of enrichment.

All components of a diffusion plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

must be maintained at an appropriate temperature and pressure to assure that the UF6 remains in the gaseous phase. The gas must be compressed at each stage to make up for a loss in pressure across the diffuser. This leads to compression heating of the gas, which then must be cooled before entering the diffuser. The requirements for pumping and cooling make diffusion plants enormous consumers of electric power

Electric power is the rate at which electrical energy is transferred by an electric circuit. The SI unit of power is the watt, one joule per second. Standard prefixes apply to watts as with other SI units: thousands, millions and billions ...

. Because of this, gaseous diffusion is the most expensive method currently used for producing enriched uranium.

History

Workers working on the Manhattan Project inOak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's popu ...

, developed several different methods for the separation of isotopes of uranium. Three of these methods were used sequentially at three different plants in Oak Ridge to produce the 235U for "Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

" and other early nuclear weapons. In the first step, the S-50 uranium enrichment facility used the thermal diffusion process to enrich the uranium from 0.7% up to nearly 2% 235U. This product was then fed into the gaseous diffusion process at the K-25 plant, the product of which was around 23% 235U. Finally, this material was fed into calutron

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was deri ...

s at the Y-12. These machines (a type of mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is us ...

) employed electromagnetic isotope separation

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derived ...

to boost the final 235U concentration to about 84%.

The preparation of UF6 feedstock for the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant was the first ever application for commercially produced fluorine, and significant obstacles were encountered in the handling of both fluorine and UF6. For example, before the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant could be built, it was first necessary to develop non-reactive chemical compound

A chemical compound is a chemical substance composed of many identical molecules (or molecular entities) containing atoms from more than one chemical element held together by chemical bonds. A molecule consisting of atoms of only one element ...

s that could be used as coatings, lubricant

A lubricant (sometimes shortened to lube) is a substance that helps to reduce friction between surfaces in mutual contact, which ultimately reduces the heat generated when the surfaces move. It may also have the function of transmitting forces, t ...

s and gasket

Some seals and gaskets

A gasket is a mechanical seal which fills the space between two or more mating surfaces, generally to prevent leakage from or into the joined objects while under compression. It is a deformable material that is used to ...

s for the surfaces that would come into contact with the UF6 gas (a highly reactive and corrosive substance). Scientists of the Manhattan Project recruited William T. Miller

William Taylor Miller (August 24, 1911 – November 15, 1998) was an American professor of organic chemistry at Cornell University. His experimental research included investigations into the mechanism of addition of halogens, especially flu ...

, a professor of organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J ...

at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

, to synthesize and develop such materials, because of his expertise in organofluorine chemistry

Organofluorine chemistry describes the chemistry of the organofluorines, organic compounds that contain the carbon–fluorine bond. Organofluorine compounds find diverse applications ranging from oil and water repellents to pharmaceuticals, r ...

. Miller and his team developed several novel non-reactive chlorofluorocarbon

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are fully or partly halogenated hydrocarbons that contain carbon (C), hydrogen (H), chlorine (Cl), and fluorine (F), produced as volatile derivatives of methane, ethane, and p ...

polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

s that were used in this application.

Calutrons were inefficient and expensive to build and operate. As soon as the engineering obstacles posed by the gaseous diffusion process had been overcome and the gaseous diffusion cascades began operating at Oak Ridge in 1945, all of the calutrons were shut down. The gaseous diffusion technique then became the preferred technique for producing enriched uranium.

At the time of their construction in the early 1940s, the gaseous diffusion plants were some of the largest buildings ever constructed. Large gaseous diffusion plants were constructed by the United States, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

(including a plant that is now in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

), the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

. Most of these have now closed or are expected to close, unable to compete economically with newer enrichment techniques. However some of the technology used in pumps and membranes still remains top secret, and some of the materials that were used remain subject to export controls, as a part of the continuing effort to control nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

.

Current status

In 2008, gaseous diffusion plants in the United States and France still generated 33% of the world's enriched uranium. However, the French plant definitively closed in May 2012, and the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Kentucky operated by the United States Enrichment Corporation (USEC) (the last fully functioning uranium enrichment facility in the United States to employ the gaseous diffusion process) ceased enrichment in 2013.''Operation of the GDP by USEC ceased operation in 2013''

uranium oxide

Uranium oxide is an oxide of the element uranium.

The metal uranium forms several oxides:

* Uranium dioxide or uranium(IV) oxide (UO2, the mineral uraninite or pitchblende)

* Diuranium pentoxide or uranium(V) oxide (U2O5)

* Uranium trioxide o ...

.

As existing gaseous diffusion plants became obsolete, they were replaced by second generation gas centrifuge technology, which requires far less electric power to produce equivalent amounts of separated uranium. AREVA replaced its Georges Besse gaseous diffusion plant with the Georges Besse II centrifuge plant.

See also

* Capenhurst * Fick's laws of diffusion * K-25 * Lanzhou *Marcoule

Marcoule Nuclear Site (french: Site nucléaire de Marcoule) is a nuclear facility in the Chusclan and Codolet communes, near Bagnols-sur-Cèze in the Gard department of France, which is in the tourist, wine and agricultural Côtes-du-Rhône r ...

* Molecular diffusion

Molecular diffusion, often simply called diffusion, is the thermal motion of all (liquid or gas) particles at temperatures above absolute zero. The rate of this movement is a function of temperature, viscosity of the fluid and the size (mass) of ...

* Nuclear fuel cycle

The nuclear fuel cycle, also called nuclear fuel chain, is the progression of nuclear fuel through a series of differing stages. It consists of steps in the ''front end'', which are the preparation of the fuel, steps in the ''service period'' in w ...

* Thomas Graham (chemist)

Thomas Graham (21 December 1805 – 16 September 1869) was a British chemist known for his pioneering work in dialysis and the diffusion of gases. He is regarded as one of the founders of colloid chemistry.

Life

Graham was born in Glasgow, an ...

* Tomsk

References

External links

Annotated references on gaseous diffusion from the Alsos Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gaseous Diffusion Isotope separation Uranium Membrane technology