The history of life on

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

traces the processes by which living and

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s evolved, from the earliest

emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for ''

gigaannum

A year or annus is the orbital period of a planetary body, for example, the Earth, moving in its orbit around the Sun. Due to the Earth's axial tilt, the course of a year sees the passing of the seasons, marked by change in weather, the ho ...

'') and evidence suggests that life emerged prior to 3.7 Ga.

Although there is some evidence of life as early as 4.1 to 4.28 Ga, it remains controversial due to the possible non-biological formation of the purported fossils.

The similarities among all known present-day

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

indicate that they have diverged through the process of

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

from a

common ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal comm ...

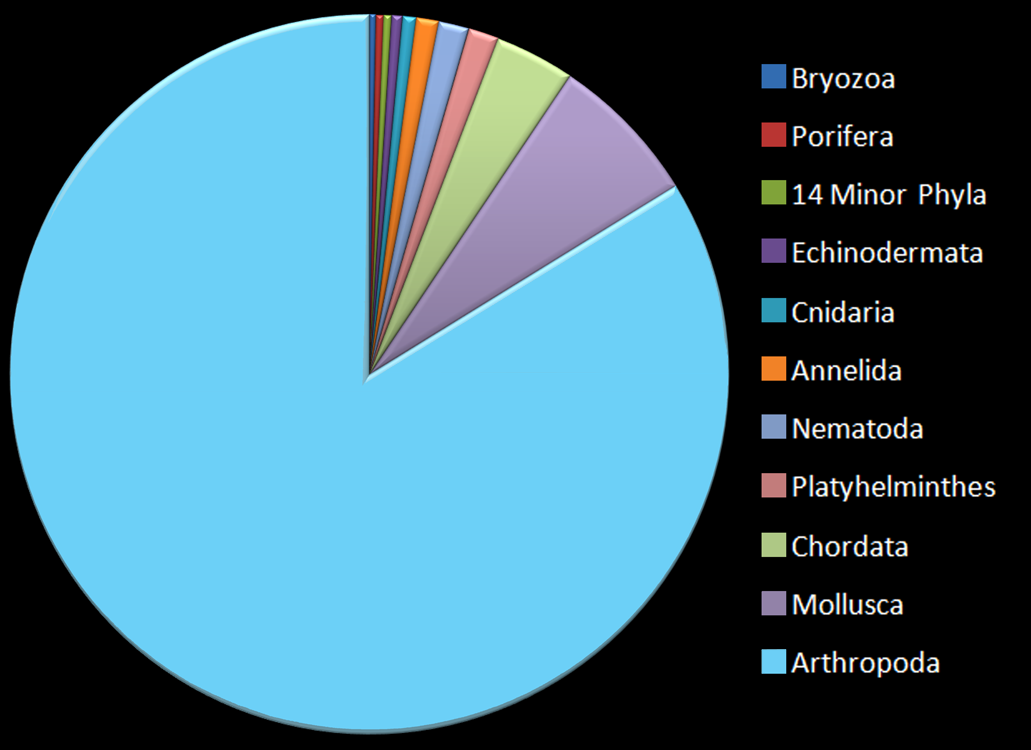

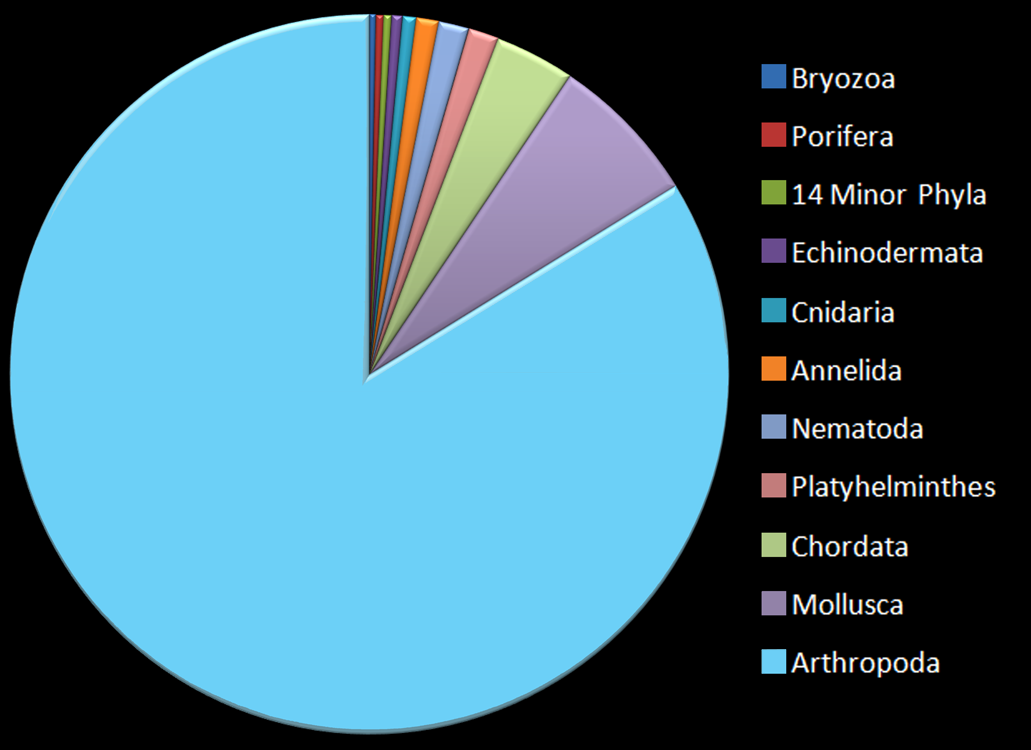

. Only a very small percentage of species have been identified: one estimate claims that Earth may have 1 trillion species.

[

*] However, only 1.75–1.8 million have been named

[ "A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 9, 2014, Section SR, Page 6 of the New York edition with the headline: Prehistory's Brilliant Future."] and 1.8 million documented in a central database.

These currently living species represent less than one percent of all species that have ever lived on Earth.

The earliest evidence of life comes from

biogenic carbon signatures and

stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations ( microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). T ...

fossils discovered in 3.7 billion-year-old

metasediment

In geology, metasedimentary rock is a type of metamorphic rock. Such a rock was first formed through the deposition and solidification of sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and e ...

ary rocks from western

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

. In 2015, possible "remains of

biotic life" were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in

Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

.

In March 2017, putative evidence of possibly the oldest forms of life on Earth was reported in the form of fossilized

microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s discovered in

hydrothermal vent precipitates in the

Nuvvuagittuq Belt of Quebec, Canada, that may have lived as early as 4.28 billion years ago, not long after the

oceans formed 4.4 billion years ago, and not long after the

formation of the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surface ...

4.54 billion years ago.

[ "A version of this article appears in print on March 2, 2017, Section A, Page 9 of the New York edition with the headline: Artful Squiggles in Rocks May Be Earth's Oldest Fossils."]

Microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet of microorganisms, mainly bacteria and archaea, or bacteria alone. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few survive in deserts ...

s of coexisting

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometr ...

and

archaea were the dominant form of life in the early

Archean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth during the Arc ...

Epoch and many of the major steps in early evolution are thought to have taken place in this environment.

The evolution of

photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

, around 3.5 Ga, eventually led to a buildup of its waste product,

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

, in the atmosphere, leading to the

great oxygenation event, beginning around 2.4 Ga.

The earliest evidence of

eukaryotes (complex

cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

s with

organelles) dates from 1.85 Ga,

and while they may have been present earlier, their diversification accelerated when they started using oxygen in their

metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run c ...

. Later, around 1.7 Ga,

multicellular organisms began to appear, with

differentiated cell

Cellular differentiation is the process in which a stem cell alters from one type to a differentiated one. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation happens multiple times during the development of a multicellular ...

s performing specialised functions.

Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote th ...

, which involves the fusion of male and female reproductive cells (

gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

s) to create a

zygote

A zygote (, ) is a eukaryotic cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes. The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individual organism.

In multicell ...

in a process called

fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

is, in contrast to

asexual reproduction, the primary method of reproduction for the vast majority of macroscopic organisms, including almost all

eukaryotes (which includes

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s and

plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclu ...

s). However the origin and

evolution of sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is an adaptive feature which is common to almost all multicellular organisms and various unicellular organisms, with some organisms being incapable of asexual reproduction. Currently the adaptive advantage of sexual reprod ...

remain a puzzle for biologists though it did evolve from a common ancestor that was a single celled eukaryotic species.

[

*

*] Bilateria, animals having a left and a right side that are mirror images of each other, appeared by 555 Ma (million years ago).

Algae-like multicellular land plants are dated back even to about 1 billion years ago, although evidence suggests that

microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s formed the earliest

terrestrial ecosystem

Terrestrial ecosystems are ecosystems which are found on land. Examples include tundra, taiga, temperate deciduous forest, tropical rain forest, grassland, deserts.

Terrestrial ecosystems differ from aquatic ecosystems by the predominant pres ...

s, at least 2.7 Ga. Microorganisms are thought to have paved the way for the inception of land plants in the

Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

T ...

period. Land plants were so successful that they are thought to have contributed to the

Late Devonian extinction event

The Late Devonian extinction consisted of several extinction events in the Late Devonian Epoch, which collectively represent one of the five largest mass extinction events in the history of life on Earth. The term primarily refers to a major ex ...

.

(The long causal chain implied seems to involve (1) the success of early tree

archaeopteris drew down CO

2 levels, leading to

global cooling

Global cooling was a conjecture, especially during the 1970s, of imminent cooling of the Earth culminating in a period of extensive glaciation, due to the cooling effects of aerosols or orbital forcing.

Some press reports in the 1970s specula ...

and lowered sea levels, (2) roots of archeopteris fostered soil development which ''increased'' rock weathering, and the subsequent nutrient run-off may have triggered

algal bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in freshwater or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompass ...

s resulting in

anoxic event

Oceanic anoxic events or anoxic events ( anoxia conditions) describe periods wherein large expanses of Earth's oceans were depleted of dissolved oxygen (O2), creating toxic, euxinic (anoxic and sulfidic) waters. Although anoxic events have not ...

s which caused marine-life die-offs. Marine species were the primary victims of the Late Devonian extinction.)

Ediacara biota

The Ediacaran (; formerly Vendian) biota is a taxonomic period classification that consists of all life forms that were present on Earth during the Ediacaran Period (). These were composed of enigmatic tubular and frond-shaped, mostly sessil ...

appear during the

Ediacaran period, while

vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with c ...

s, along with most other modern

phyla originated about during the

Cambrian explosion.

During the

Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last ...

period,

synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

s, including the ancestors of

mammals, dominated the land, but most of this group became extinct in the

Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, as ...

. During the recovery from this catastrophe,

archosaurs became the most abundant land vertebrates;

one archosaur group, the

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s, dominated the

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

and

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

periods. After the

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With the ...

killed off the non-avian dinosaurs, mammals

increased rapidly in size and diversity. Such

mass extinction

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. I ...

s may have accelerated evolution by providing opportunities for new groups of organisms to diversify.

Earliest history of Earth

The oldest

meteorite fragments found on Earth are about 4.54 billion years old; this, coupled primarily with the dating of ancient

lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

deposits, has put the estimated age of Earth at around that time.

[

*

*] The

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

has the same composition as Earth's

crust but does not contain an

iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

-rich

core

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber), the signal-carrying portion of an optical fiber

* Core, the centra ...

like the Earth's. Many scientists think that about 40 million years after the formation of Earth, it collided with

a body the size of Mars, throwing crust material into the orbit that formed the Moon. Another

hypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obse ...

is that the Earth and Moon started to coalesce at the same time but the Earth, having much stronger

gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

than the early Moon, attracted almost all the iron particles in the area.

Until 2001, the oldest rocks found on Earth were about 3.8 billion years old,

leading scientists to estimate that the Earth's surface had been molten until then. Accordingly, they named this part of Earth's history the

Hadean.

However, analysis of

zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of t ...

s formed 4.4 Ga indicates that Earth's crust solidified about 100 million years after the planet's formation and that the planet quickly acquired oceans and an

atmosphere, which may have been capable of supporting life.

Evidence from the Moon indicates that from 4 to 3.8 Ga it suffered a

Late Heavy Bombardment

The Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB), or lunar cataclysm, is a hypothesized event thought to have occurred approximately 4.1 to 3.8 billion years (Ga) ago, at a time corresponding to the Neohadean and Eoarchean eras on Earth. According to the hypot ...

by debris that was left over from the formation of the

Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

, and the Earth should have experienced an even heavier bombardment due to its stronger gravity.

While there is no direct evidence of conditions on Earth 4 to 3.8 Ga, there is no reason to think that the Earth was not also affected by this late heavy bombardment. This event may well have stripped away any previous atmosphere and oceans; in this case

gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

es and water from

comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ...

impacts may have contributed to their replacement, although

outgassing

Outgassing (sometimes called offgassing, particularly when in reference to indoor air quality) is the release of a gas that was dissolved, trapped, frozen, or absorbed in some material. Outgassing can include sublimation and evaporation (which ...

from

volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the Crust (geology), crust of a Planet#Planetary-mass objects, planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and volcanic gas, gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Ear ...

es on Earth would have supplied at least half. However, if subsurface microbial life had evolved by this point, it would have survived the bombardment.

Earliest evidence for life on Earth

The earliest identified organisms were minute and relatively featureless, and their fossils look like small rods that are very difficult to tell apart from structures that arise through abiotic physical processes. The oldest undisputed evidence of life on Earth, interpreted as fossilized bacteria, dates to 3 Ga.

Other finds in rocks dated to about 3.5 Ga have been interpreted as bacteria, with

geochemical evidence also seeming to show the presence of life 3.8 Ga. However, these analyses were closely scrutinized, and non-biological processes were found which could produce all of the "signatures of life" that had been reported.

While this does not prove that the structures found had a non-biological origin, they cannot be taken as clear evidence for the presence of life. Geochemical signatures from rocks deposited 3.4 Ga have been interpreted as evidence for life,

although these statements have not been thoroughly examined by critics.

Evidence for fossilized microorganisms considered to be 3.77 billion to 4.28 billion years old was found in the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt in Quebec, Canada,

although the evidence is disputed as inconclusive.

Origins of life on Earth

Biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

s reason that all living organisms on Earth must share a single

last universal ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; th ...

, because it would be virtually impossible that two or more separate lineages could have independently developed the many complex biochemical mechanisms common to all living organisms.

Independent emergence on Earth

Life on Earth is based on

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon mak ...

and

water

Water (chemical formula ) is an Inorganic compound, inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living ...

. Carbon provides stable frameworks for complex chemicals and can be easily extracted from the environment, especially from

carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

.

There is no other chemical element whose properties are similar enough to carbon's to be called an analogue;

silicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic ta ...

, the element directly below carbon on the

periodic table, does not form very many complex stable molecules, and because most of its compounds are water-insoluble and because

silicon dioxide

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

is a hard and abrasive solid in contrast to

carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

at temperatures associated with living things, it would be more difficult for organisms to extract. The elements

boron and

phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

have more complex chemistries, but suffer from other limitations relative to carbon. Water is an excellent

solvent

A solvent (s) (from the Latin '' solvō'', "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for ...

and has two other useful properties: the fact that ice floats enables aquatic organisms to survive beneath it in winter; and its molecules have

electrically negative and positive ends, which enables it to form a wider range of compounds than other solvents can. Other good solvents, such as

ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

, are liquid only at such low temperatures that chemical reactions may be too slow to sustain life, and lack water's other advantages. Organisms based on

alternative biochemistry may, however, be possible on other planets.

Research on how life might have emerged from non-living chemicals focuses on three possible starting points:

self-replication

Self-replication is any behavior of a dynamical system that yields construction of an identical or similar copy of itself. Biological cells, given suitable environments, reproduce by cell division. During cell division, DNA is replicated and c ...

, an organism's ability to produce offspring that are very similar to itself; metabolism, its ability to feed and repair itself; and external

cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

s, which allow food to enter and waste products to leave, but exclude unwanted substances. Research on abiogenesis still has a long way to go, since theoretical and

empirical approaches are only beginning to make contact with each other.

Replication first: RNA world

Even the simplest members of the

three modern domains of life use

DNA to record their "recipes" and a complex array of

RNA and

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

molecules to "read" these instructions and use them for growth, maintenance and self-replication. The discovery that some RNA molecules can

catalyze

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

both their own replication and the construction of proteins led to the hypothesis of earlier life-forms based entirely on RNA. These

ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozymes demons ...

s could have formed an

RNA world

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existen ...

in which there were individuals but no species, as

mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA replication, DNA or viral repl ...

s and

horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

s would have meant that offspring were likely to have different

genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding g ...

s from their parents, and

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

occurred at the level of genes rather than organisms.

RNA would later have been replaced by DNA, which can build longer, more stable genomes, strengthening heritability and expanding the capabilities of individual organisms.

Ribozymes remain as the main components of

ribosomes, the "protein factories" in modern cells. Evidence suggests the first RNA molecules formed on Earth prior to 4.17 Ga.

Although short self-replicating RNA molecules have been artificially produced in laboratories, doubts have been raised about whether natural non-biological synthesis of RNA is possible.

[

*

*] The earliest "ribozymes" may have been formed of simpler

nucleic acids such as

PNA,

TNA or

GNA, which would have been replaced later by RNA.

In 2003, it was proposed that porous metal sulfide

precipitates would assist RNA synthesis at about and ocean-bottom pressures near

hydrothermal vents. Under this hypothesis,

lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids includ ...

membranes would be the last major cell components to appear and, until then, the

protocell

A protocell (or protobiont) is a self-organized, endogenously ordered, spherical collection of lipids proposed as a stepping-stone toward the origin of life. A central question in evolution is how simple protocells first arose and how they could ...

s would be confined to the pores.

Metabolism first: Iron–sulfur world

A series of experiments starting in 1997 showed that early stages in the formation of proteins from inorganic materials including

carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

and

hydrogen sulfide could be achieved by using

iron sulfide

Iron sulfide or Iron sulphide can refer to range of chemical compounds composed of iron and sulfur.

Minerals

By increasing order of stability:

* Iron(II) sulfide, FeS

* Greigite, Fe3S4 (cubic)

* Pyrrhotite, Fe1−xS (where x = 0 to 0.2) (monocli ...

and

nickel sulfide

Nickel sulfide is any inorganic compound with the formula NiSx. They range in color from bronze (Ni3S2) to black (NiS2). The nickel sulfide with simplest stoichiometry is NiS, also known as the mineral millerite. From the economic perspective, ...

as

catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

s. Most of the steps required temperatures of about and moderate pressures, although one stage required and a pressure equivalent to that found under of rock. Hence it was suggested that self-sustaining synthesis of proteins could have occurred near hydrothermal vents.

Membranes first: Lipid world

It has been suggested that double-walled "bubbles" of lipids like those that form the external membranes of cells may have been an essential first step. Experiments that simulated the conditions of the early Earth have reported the formation of lipids, and these can spontaneously form

liposome

A liposome is a small artificial Vesicle (biology and chemistry), vesicle, spherical in shape, having at least one lipid bilayer. Due to their hydrophobicity and/or hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, particle size and many other properties, lipo ...

s, double-walled "bubbles," and then reproduce themselves.

Although they are not intrinsically information-carriers as nucleic acids are, they would be subject to

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

for longevity and reproduction. Nucleic acids such as RNA might then have formed more easily within the liposomes than outside.

The clay hypothesis

RNA is complex and there are doubts about whether it can be produced non-biologically in the wild.

Some

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

s, notably

montmorillonite

Montmorillonite is a very soft phyllosilicate group of minerals that form when they precipitate from water solution as microscopic crystals, known as clay. It is named after Montmorillon in France. Montmorillonite, a member of the smectite gro ...

, have properties that make them plausible accelerators for the emergence of an RNA world: they grow by self-replication of their

crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macro ...

line pattern; they are subject to an analogue of natural selection, as the clay "species" that grows fastest in a particular environment rapidly becomes dominant; and they can catalyze the formation of RNA molecules. Although this idea has not become the scientific consensus, it still has active supporters.

Research in 2003 reported that montmorillonite could also accelerate the conversion of

fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, ...

s into "bubbles," and that the "bubbles" could encapsulate RNA attached to the clay. These "bubbles" can then grow by absorbing additional lipids and then divide. The formation of the earliest cells may have been aided by similar processes.

A similar hypothesis presents self-replicating iron-rich clays as the progenitors of

nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecule ...

s, lipids and

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

s.

Prebiotic environments

Geothermal springs

Wet-dry cycles at geothermal springs are shown to solve the problem of hydrolysis and promote the polymerization and vesicle encapsulation of biopolymers.

The temperatures of geothermal springs are suitable for biomolecules. Silica minerals and metal sulfides at these environments have photocatalytic properties to catalyze biomolecules. Solar UV exposure also promotes the synthesis of biomolecules like RNA nucleotides.

An analysis of hydrothermal veins at a 3.5 Gya geothermal spring setting were found to have elements required for the origin of life, which are potassium, boron, hydrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, zinc, nitrogen, and oxygen. Mulkidjanian and colleagues find that such environments have identical ionic concentrations to the cytoplasm of modern cells.

Fatty acids in acidic or slightly alkaline geothermal springs assemble into vesicles after wet-dry cycles as there is a lower concentration of ionic solutes at geothermal springs since they are freshwater environments, in contrast to seawater which has a higher concentration of ionic solutes. For organic compounds to be present at geothermal springs, they would have likely been transported by carbonaceous meteors. The molecules that fell from the meteors were then accumulated in geothermal springs. As for the evolutionary implications, freshwater heterotrophic cells that depended upon synthesized organic compounds later evolved photosynthesis because of the continuous exposure to sunlight as well as their cell walls with ion pumps to maintain their intracellular metabolism after they entered the oceans.

Deep sea hydrothermal vents

Catalytic mineral particles at these environments likely catalyzed organic compounds. Scientists simulated laboratory conditions that were identical to white smokers and successfully oligomerized RNA, measured to be 4 units long. Another experiment that replicated conditions also similar white smokers, with phospholipids present resulted in the assembly of vesicles. Exergonic reactions at hydrothermal vents are suggested to have been a source of free energy that promoted chemical reactions, synthesis of organic molecules, and are inducive to chemical gradients. In small rock pore systems, membranous structures between alkaline seawater and the acidic ocean would be conducive to proton gradients. Small mineral cavities or mineral gels could have been a compartment for abiogenic processes. A genomic analysis supports this hypothesis as they found 355 genes that likely traced to

LUCA

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; th ...

upon 6.1 million sequenced prokaryotic genes. They reconstruct LUCA as a thermophilic anaerobe with a Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, implying an origin of life at white smokers.

Life "seeded" from elsewhere

The Panspermia hypothesis does not explain how life arose originally, but simply examines the possibility of it coming from somewhere other than Earth. The idea that life on Earth was "seeded" from elsewhere in the Universe dates back at least to the Greek philosopher

Anaximander in the sixth century

BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

. In the twentieth century it was proposed by the

physical chemist

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

Svante Arrhenius

Svante August Arrhenius ( , ; 19 February 1859 – 2 October 1927) was a Swedish scientist. Originally a physicist, but often referred to as a chemist, Arrhenius was one of the founders of the science of physical chemistry. He received the Nob ...

,

by the

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either ...

s

Fred Hoyle

Sir Fred Hoyle FRS (24 June 1915 – 20 August 2001) was an English astronomer who formulated the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis and was one of the authors of the influential B2FH paper. He also held controversial stances on other sci ...

and

Chandra Wickramasinghe,

and by

molecular biologist

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interact ...

Francis Crick and chemist

Leslie Orgel

Leslie Eleazer Orgel FRS (12 January 1927 – 27 October 2007) was a British chemist. He is known for his theories on the origin of life.

Biography

Leslie Orgel was born in London, England, on . He received his Bachelor of Arts degree in chemi ...

.

There are three main versions of the "seeded from elsewhere" hypothesis: from elsewhere in our Solar System via fragments knocked into space by a large

meteor

A meteoroid () is a small rocky or metallic body in outer space.

Meteoroids are defined as objects significantly smaller than asteroids, ranging in size from grains to objects up to a meter wide. Objects smaller than this are classified as mi ...

impact, in which case the most credible sources are

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

and

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

; by

alien visitors, possibly as a result of accidental

contamination

Contamination is the presence of a constituent, impurity, or some other undesirable element that spoils, corrupts, infects, makes unfit, or makes inferior a material, physical body, natural environment, workplace, etc.

Types of contamination

...

by microorganisms that they brought with them;

and from outside the Solar System but by natural means.

Experiments in low Earth orbit, such as

EXOSTACK

NASA's Long Duration Exposure Facility, or LDEF (pronounced "eldef"), was a school bus-sized cylindrical facility designed to provide long-term experimental data on the outer space environment and its effects on space systems, materials, operatio ...

, have demonstrated that some microorganism

spores can survive the shock of being catapulted into space and some can survive exposure to outer space radiation for at least 5.7 years.

Scientists are divided over the likelihood of life arising independently on Mars, or on other planets in our

galaxy.

Environmental and evolutionary impact of microbial mats

Microbial mats are multi-layered, multi-species colonies of bacteria and other organisms that are generally only a few millimeters thick, but still contain a wide range of chemical environments, each of which favors a different set of microorganisms.

To some extent each mat forms its own

food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

, as the by-products of each group of microorganisms generally serve as "food" for adjacent groups.

Stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations ( microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). T ...

s are stubby pillars built as microorganisms in mats slowly migrate upwards to avoid being smothered by sediment deposited on them by water.

There has been vigorous debate about the validity of alleged stromatolite fossils from before 3 Ga, with critics arguing that they could have been formed by non-biological processes.

In 2006, another find of stromatolites was reported from the same part of Australia, in rocks dated to 3.5 Ga.

In modern underwater mats the top layer often consists of photosynthesizing

cyanobacteria which create an oxygen-rich environment, while the bottom layer is oxygen-free and often dominated by hydrogen sulfide emitted by the organisms living there.

Oxygen is toxic to organisms that are not adapted to it, but greatly increases the

metabolic efficiency of oxygen-adapted organisms;

by bacteria in mats increased biological productivity by a factor of between 100 and 1,000. The source of hydrogen atoms used by oxygenic photosynthesis is water, which is much more plentiful than the geologically produced

reducing agents

In chemistry, a reducing agent (also known as a reductant, reducer, or electron donor) is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an (called the , , , or ).

Examples of substances that are commonly reducing agents include the Earth meta ...

required by the earlier non-oxygenic photosynthesis.

From this point onwards life itself produced significantly more of the resources it needed than did geochemical processes.

Oxygen became a significant component of Earth's atmosphere about 2.4 Ga. Although eukaryotes may have been present much earlier,

the oxygenation of the atmosphere was a prerequisite for the evolution of the most complex eukaryotic cells, from which all multicellular organisms are built.

The boundary between oxygen-rich and oxygen-free layers in microbial mats would have moved upwards when photosynthesis shut down overnight, and then downwards as it resumed on the next day. This would have created

selection pressure

Any cause that reduces or increases reproductive success in a portion of a population potentially exerts evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of ...

for organisms in this intermediate zone to acquire the ability to tolerate and then to use oxygen, possibly via

endosymbiosis

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within ...

, where one organism lives inside another and both of them benefit from their association.

Cyanobacteria have the most complete biochemical "toolkits" of all the mat-forming organisms. Hence they are the most self-sufficient, well-adapted to strike out on their own both as floating mats and as the first of the

phytoplankton, providing the basis of most marine food chains.

Diversification of eukaryotes

One possible family tree of eukaryotes

[

*]

Chromatin, nucleus, endomembrane system, and mitochondria

Eukaryotes may have been present long before the oxygenation of the atmosphere,

but most modern eukaryotes require oxygen, which is used by their

mitochondria to fuel the production of

ATP, the internal energy supply of all known cells.

In the 1970s, a vigorous debate concluded that eukaryotes emerged as a result of a sequence of endosymbiosis between

prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Conne ...

s. For example: a

predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

y microorganism invaded a large prokaryote, probably an

archaean, but instead of killing its prey, the attacker took up residence and evolved into mitochondria; one of these

chimera

Chimera, Chimaera, or Chimaira (Greek for " she-goat") originally referred to:

* Chimera (mythology), a fire-breathing monster of Ancient Lycia said to combine parts from multiple animals

* Mount Chimaera, a fire-spewing region of Lycia or Cilici ...

s later tried to swallow a photosynthesizing cyanobacterium, but the victim survived inside the attacker and the new combination became the ancestor of

plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclu ...

s; and so on. After each endosymbiosis, the partners eventually eliminated unproductive duplication of genetic functions by re-arranging their genomes, a process which sometimes involved transfer of genes between them. Another hypothesis proposes that mitochondria were originally

sulfur- or

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

-metabolising endosymbionts, and became oxygen-consumers later. On the other hand, mitochondria might have been part of eukaryotes' original equipment.

There is a debate about when eukaryotes first appeared: the presence of

steranes in Australian

shales may indicate eukaryotes at 2.7 Ga;

however, an analysis in 2008 concluded that these chemicals infiltrated the rocks less than 2.2 Ga and prove nothing about the origins of eukaryotes. Fossils of the

algae ''

Grypania

''Grypania'' is an early, tube-shaped fossil from the Proterozoic eon. The organism, with a size over one centimeter and consistent form, could have been a giant bacterium, a bacterial colony, or a eukaryotic alga. The oldest probable ''Grypania' ...

'' have been reported in 1.85 billion-year-old rocks (originally dated to 2.1 Ga but later revised

), indicating that eukaryotes with organelles had already evolved. A diverse collection of fossil algae were found in rocks dated between 1.5 and 1.4 Ga. The earliest known fossils of

fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

date from 1.43 Ga.

Plastids

Plastids, the superclass of

organelles of which

chloroplasts are the best-known exemplar, are thought to have originated from

endosymbiotic

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within ...

cyanobacteria. The symbiosis evolved around 1.5 Ga and enabled eukaryotes to carry out

oxygenic photosynthesis.

Three evolutionary lineages of photosynthetic plastids have since emerged: chloroplasts in

green algae and plants,

rhodoplast

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), are one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta also comprises one of the largest phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 currently recognized species with taxonomic revisions ongoing. The majority ...

s in

red algae and

cyanelles in the

glaucophyte

The glaucophytes, also known as glaucocystophytes or glaucocystids, are a small group of unicellular algae found in freshwater and moist terrestrial environments, less common today than they were during the Proterozoic. The stated number of speci ...

s. Not long after this primary endosymbiosis of plastids, rhodoplasts and chloroplasts were passed down to other

bikont

A bikont ("two flagella") is any of the eukaryotic organisms classified in the group Bikonta. Many single-celled members of the group, and the presumed ancestor, have two flagella.

Enzymes

Another shared trait of bikonts is the fusion of two ge ...

s, establishing an eukaryotic assemblage of phytoplankton by the end of the

Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is prec ...

Eon.

Sexual reproduction and multicellular organisms

Evolution of sexual reproduction

The defining characteristics of

sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote th ...

in eukaryotes are

meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately r ...

and

fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

, resulting in

genetic recombination, giving offspring 50% of their genes from each parent.

By contrast, in

asexual reproduction there is no recombination, but occasional

horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

. Bacteria also exchange DNA by

bacterial conjugation, enabling the spread of resistance to

antibiotics and other

toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849 ...

s, and the ability to utilize new

metabolites. However, conjugation is not a means of reproduction, and is not limited to members of the same species – there are cases where bacteria transfer DNA to plants and animals.

On the other hand, bacterial

transformation

Transformation may refer to:

Science and mathematics

In biology and medicine

* Metamorphosis, the biological process of changing physical form after birth or hatching

* Malignant transformation, the process of cells becoming cancerous

* Tran ...

is clearly an adaptation for transfer of DNA between bacteria of the same species. This is a complex process involving the products of numerous bacterial genes and can be regarded as a bacterial form of sex. This process occurs naturally in at least 67 prokaryotic species (in seven different phyla). Sexual reproduction in eukaryotes may have evolved from bacterial transformation.

The disadvantages of sexual reproduction are well-known: the genetic reshuffle of recombination may break up favorable combinations of genes; and since males do not directly increase the number of offspring in the next generation, an asexual population can out-breed and displace in as little as 50 generations a sexual population that is equal in every other respect.

Nevertheless, the great majority of animals, plants, fungi and

protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the exc ...

s reproduce sexually. There is strong evidence that sexual reproduction arose early in the history of eukaryotes and that the genes controlling it have changed very little since then. How sexual reproduction evolved and survived is an unsolved puzzle.

The

Red Queen hypothesis

The Red Queen hypothesis is a hypothesis in evolutionary biology proposed in 1973, that species must constantly adapt, evolve, and proliferate in order to survive while pitted against ever-evolving opposing species. The hypothesis was intended ...

suggests that sexual reproduction provides protection against

parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s, because it is easier for parasites to evolve means of overcoming the defenses of genetically identical

clones than those of sexual species that present moving targets, and there is some experimental evidence for this. However, there is still doubt about whether it would explain the survival of sexual species if multiple similar clone species were present, as one of the clones may survive the attacks of parasites for long enough to out-breed the sexual species.

Furthermore, contrary to the expectations of the Red Queen hypothesis, Kathryn A. Hanley et al. found that the prevalence, abundance and mean intensity of mites was significantly higher in sexual geckos than in asexuals sharing the same habitat. In addition, biologist Matthew Parker, after reviewing numerous genetic studies on plant disease resistance, failed to find a single example consistent with the concept that pathogens are the primary selective agent responsible for sexual reproduction in the host.

Alexey Kondrashov

Alexey Simonovich Kondrashov (russian: Алексе́й Си́монович Кондрашо́в) (born April 11, 1957) worked on a variety of subjects in evolutionary genetics. He is best known for the ''deterministic mutation hypothesis''Kondr ...

's ''deterministic mutation hypothesis'' (DMH) assumes that each organism has more than one harmful mutation and the combined effects of these mutations are more harmful than the sum of the harm done by each individual mutation. If so, sexual recombination of genes will reduce the harm that bad mutations do to offspring and at the same time eliminate some bad mutations from the

gene pool by isolating them in individuals that perish quickly because they have an above-average number of bad mutations. However, the evidence suggests that the DMH's assumptions are shaky because many species have on average less than one harmful mutation per individual and no species that has been investigated shows evidence of

synergy between harmful mutations.

The random nature of recombination causes the relative abundance of alternative traits to vary from one generation to another. This

genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

is insufficient on its own to make sexual reproduction advantageous, but a combination of genetic drift and natural selection may be sufficient. When chance produces combinations of good traits, natural selection gives a large advantage to lineages in which these traits become genetically linked. On the other hand, the benefits of good traits are neutralized if they appear along with bad traits. Sexual recombination gives good traits the opportunities to become linked with other good traits, and mathematical models suggest this may be more than enough to offset the disadvantages of sexual reproduction.

Other combinations of hypotheses that are inadequate on their own are also being examined.

The adaptive function of sex remains a major unresolved issue in biology. The competing models to explain it were reviewed by John A. Birdsell and

Christopher Wills. The hypotheses discussed above all depend on the possible beneficial effects of random genetic variation produced by genetic recombination. An alternative view is that sex arose and is maintained as a process for repairing DNA damage, and that the genetic variation produced is an occasionally beneficial byproduct.

Multicellularity

The simplest definitions of "multicellular," for example "having multiple cells," could include

colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

cyanobacteria like ''

Nostoc

''Nostoc'', also known as star jelly, troll’s butter, spit of moon, fallen star, witch's butter (not to be confused with the fungi commonly known as witches' butter), and witch’s jelly, is the most common genus of cyanobacteria found in var ...

''. Even a technical definition such as "having the same genome but different types of cell" would still include some

genera of the green algae

Volvox

''Volvox'' is a polyphyletic genus of chlorophyte green algae in the family Volvocaceae. It forms spherical colonies of up to 50,000 cells. They live in a variety of freshwater habitats, and were first reported by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 170 ...

, which have cells that specialize in reproduction. Multicellularity evolved independently in organisms as diverse as

sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throug ...

s and other animals, fungi, plants,

brown algae

Brown algae (singular: alga), comprising the class Phaeophyceae, are a large group of multicellular algae, including many seaweeds located in colder waters within the Northern Hemisphere. Brown algae are the major seaweeds of the temperate and p ...

, cyanobacteria,

slime mold

Slime mold or slime mould is an informal name given to several kinds of unrelated eukaryotic organisms with a life cycle that includes a free-living single-celled stage and the formation of spores. Spores are often produced in macroscopic mul ...

s and

myxobacteria

The myxobacteria ("slime bacteria") are a group of bacteria that predominantly live in the soil and feed on insoluble organic substances. The myxobacteria have very large genomes relative to other bacteria, e.g. 9–10 million nucleotides except ...

.

For the sake of brevity, this article focuses on the organisms that show the greatest specialization of cells and variety of cell types, although this approach to the

evolution of biological complexity

The evolution of biological complexity is one important outcome of the process of evolution. Evolution has produced some remarkably complex organisms – although the actual level of complexity is very hard to define or measure accurately in biolo ...

could be regarded as "rather

anthropocentric

Anthropocentrism (; ) is the belief that human beings are the central or most important entity in the universe. The term can be used interchangeably with humanocentrism, and some refer to the concept as human supremacy or human exceptionalism. ...

."

The initial advantages of multicellularity may have included: more efficient sharing of nutrients that are digested outside the cell,

increased resistance to predators, many of which attacked by engulfing; the ability to resist currents by attaching to a firm surface; the ability to reach upwards to filter-feed or to obtain sunlight for photosynthesis;

the ability to create an internal environment that gives protection against the external one;

and even the opportunity for a group of cells to behave "intelligently" by sharing information.

These features would also have provided opportunities for other organisms to diversify, by creating more varied environments than flat microbial mats could.

Multicellularity with differentiated cells is beneficial to the organism as a whole but disadvantageous from the point of view of individual cells, most of which lose the opportunity to reproduce themselves. In an asexual multicellular organism, rogue cells which retain the ability to reproduce may take over and reduce the organism to a mass of undifferentiated cells. Sexual reproduction eliminates such rogue cells from the next generation and therefore appears to be a prerequisite for complex multicellularity.

The available evidence indicates that eukaryotes evolved much earlier but remained inconspicuous until a rapid diversification around 1 Ga. The only respect in which eukaryotes clearly surpass bacteria and archaea is their capacity for variety of forms, and sexual reproduction enabled eukaryotes to exploit that advantage by producing organisms with multiple cells that differed in form and function.

By comparing the composition of transcription factor families and regulatory network motifs between unicellular organisms and multicellular organisms, scientists found there are many novel transcription factor families and three novel types of regulatory network motifs in multicellular organisms, and novel family transcription factors are preferentially wired into these novel network motifs which are essential for multicullular development. These results propose a plausible mechanism for the contribution of novel-family transcription factors and novel network motifs to the origin of multicellular organisms at transcriptional regulatory level.

Fossil evidence

The

Francevillian biota

The Francevillian biota (also known as Gabon macrofossils or Gabonionta) is a group of 2.1-billion-year-old Palaeoproterozoic, macroscopic organisms known from fossils found in Gabon in the Palaeoproterozoic Francevillian B Formation, a black shal ...

fossils, dated to 2.1 Ga, are the earliest known fossil organisms that are clearly multicellular.

They may have had differentiated cells.

Another early multicellular fossil, ''

Qingshania'', dated to 1.7 Ga, appears to consist of virtually identical cells. The red algae called ''

Bangiomorpha'', dated at 1.2 Ga, is the earliest known organism that certainly has differentiated, specialized cells, and is also the oldest known sexually reproducing organism.

The 1.43 billion-year-old fossils interpreted as fungi appear to have been multicellular with differentiated cells.

The "string of beads" organism ''

Horodyskia

''Horodyskia'' is a fossilised organism found in rocks dated from to . Its shape has been described as a "string of beads" connected by a very fine thread. It is considered one of the oldest known eukaryotes.

Biology

Comparisons of differe ...

'', found in rocks dated from 1.5 Ga to 900 Ma, may have been an early metazoan;

however, it has also been interpreted as a colonial

foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

n.

Emergence of animals

A family tree of the animals

Animals are multicellular eukaryotes,

Myxozoa

Myxozoa (etymology: Greek: μύξα ''myxa'' "slime" or "mucus" + thematic vowel o + ζῷον ''zoon'' "animal") is a subphylum of aquatic cnidarian animals – all obligate parasites. It contains the smallest animals ever known to have lived. O ...

were thought to be an exception, but are now thought to be heavily modified members of the Cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that ...

. and are distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking

cell walls. All animals are

motile

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Definitions

Motility, the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy, can be contrasted with sessility, the state of organisms th ...

, if only at certain life stages. All animals except sponges have bodies differentiated into separate

tissues, including

muscles, which move parts of the animal by contracting, and

nerve tissue

Nervous tissue, also called neural tissue, is the main tissue component of the nervous system. The nervous system regulates and controls body functions and activity. It consists of two parts: the central nervous system (CNS) comprising the brain ...

, which transmits and processes signals. In November 2019, researchers reported the discovery of ''

Caveasphaera

''Caveasphaera'' is a multicellular organism found in 609-million-year-old rocks laid down during the Ediacaran period in the Guizhou Province of South China. The organism is not easily defined as an animal or non-animal. The organism is notable ...

'', a

multicellular organism found in 609-million-year-old rocks, that is not easily defined as an animal or non-animal, which may be related to one of the earliest instances of

animal evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

.

Fossil studies of ''Caveasphaera'' have suggested that animal-like embryonic development arose much earlier than the oldest clearly defined animal fossils.

and may be consistent with studies suggesting that animal evolution may have begun about 750 million years ago.

Nonetheless, the earliest widely accepted animal fossils are the rather modern-looking

cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that ...

ns (the group that includes

jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrell ...

,

sea anemones and ''

Hydra''), possibly from around , although fossils from the

Doushantuo Formation

The Doushantuo Formation (formerly transcribed as Toushantuo or Toushantou, from ) is a geological formation in western Hubei, eastern Guizhou, southern Shaanxi, central Jiangxi, and other localities in China. It is known for the fossil Lagerst ...

can only be dated approximately. Their presence implies that the cnidarian and

bilaterian lineages had already diverged.

The Ediacara biota, which flourished for the last 40 million years before the start of the

Cambrian,

were the first animals more than a very few centimetres long. Many were flat and had a "quilted" appearance, and seemed so strange that there was a proposal to classify them as a separate

kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

,

Vendozoa

Vendobionts or Vendozoans (Vendobionta) are a proposed very high-level, extinct clade of benthic organisms that made up of the majority of the organisms that were part of the Ediacaran biota. It is a hypothetical group and at the same time, it ...

.

Others, however, have been interpreted as early

molluscs (''

Kimberella

''Kimberella'' is an extinct genus of bilaterian known only from rocks of the Ediacaran period. The slug-like organism fed by scratching the microbial surface on which it dwelt in a manner similar to the gastropods, although its affinity with t ...

''

),

echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the s ...

s (''

Arkarua''), and

arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s (''

Spriggina

''Spriggina'' is a genus of early bilaterian animals whose relationship to living animals is unclear. Fossils of ''Spriggina'' are known from the late Ediacaran period in what is now South Australia. ''Spriggina floundersi'' is the official fo ...

'', ''

Parvancorina''). There is still debate about the classification of these specimens, mainly because the diagnostic features which allow taxonomists to classify more recent organisms, such as similarities to living organisms, are generally absent in the Ediacarans. However, there seems little doubt that ''Kimberella'' was at least a

triploblastic

Triploblasty is a condition of the gastrula in which there are three primary germ layers: the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Germ cells are set aside in the embryo at the blastula stage, which are incorporated into the gonads during organo ...

bilaterian animal, in other words, an animal significantly more complex than the cnidarians.

The

small shelly fauna

The small shelly fauna, small shelly fossils (SSF), or early skeletal fossils (ESF) are mineralized fossils, many only a few millimetres long, with a nearly continuous record from the latest stages of the Ediacaran to the end of the Early Cambri ...

are a very mixed collection of fossils found between the Late Ediacaran and

Middle Cambrian

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek ...

periods. The earliest, ''

Cloudina'', shows signs of successful defense against predation and may indicate the start of an

evolutionary arms race