Enzyme Inhibitor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An enzyme inhibitor is a

An enzyme inhibitor is a

Animals and plants have evolved to synthesise a vast array of poisonous products including

Animals and plants have evolved to synthesise a vast array of poisonous products including

The most common uses for enzyme inhibitors are as drugs to treat disease. Many of these inhibitors target a human enzyme and aim to correct a pathological condition. For instance,

The most common uses for enzyme inhibitors are as drugs to treat disease. Many of these inhibitors target a human enzyme and aim to correct a pathological condition. For instance,

Drugs are also used to inhibit enzymes needed for the survival of pathogens. For example, bacteria are surrounded by a thick cell wall made of a net-like polymer called

Drugs are also used to inhibit enzymes needed for the survival of pathogens. For example, bacteria are surrounded by a thick cell wall made of a net-like polymer called

New drugs are the products of a long drug development process, the first step of which is often the discovery of a new enzyme inhibitor. There are two principle approaches of discovering these inhibitors.

The first general method is rational drug design based on mimicking the

New drugs are the products of a long drug development process, the first step of which is often the discovery of a new enzyme inhibitor. There are two principle approaches of discovering these inhibitors.

The first general method is rational drug design based on mimicking the

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

that binds to an enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

and blocks its activity. Enzymes are protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s that speed up chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the IUPAC nomenclature for organic transformations, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the pos ...

s necessary for life, in which substrate molecules are converted into product

Product may refer to:

Business

* Product (business), an item that serves as a solution to a specific consumer problem.

* Product (project management), a deliverable or set of deliverables that contribute to a business solution

Mathematics

* Produ ...

s. An enzyme facilitates a specific chemical reaction by binding the substrate to its active site, a specialized area on the enzyme that accelerates the most difficult step of the reaction.

An enzyme inhibitor stops ("inhibits") this process, either by binding to the enzyme's active site (thus preventing the substrate itself from binding) or by binding to another site on the enzyme such that the enzyme's catalysis

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

of the reaction is blocked. Enzyme inhibitors may bind reversibly or irreversibly. Irreversible inhibitors form a chemical bond

A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between atoms or ions that enables the formation of molecules and crystals. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds, or through the sharing of ...

with the enzyme such that the enzyme is inhibited until the chemical bond is broken. By contrast, reversible inhibitors bind non-covalently and may spontaneously leave the enzyme, allowing the enzyme to resume its function. Reversible inhibitors produce different types of inhibition depending on whether they bind to the enzyme, the enzyme-substrate complex, or both.

Enzyme inhibitors play an important role in all cells, since they are generally specific to one enzyme and serve to control that enzyme's activity. For example, enzymes in a metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell. The reactants, products, and intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are modified by a sequence of chemical reac ...

may be inhibited by molecules produced later in the pathway, thus curtailing the production of molecules that are no longer needed. This type of negative feedback is an important way to maintain balance

Balance or balancing may refer to:

Common meanings

* Balance (ability) in biomechanics

* Balance (accounting)

* Balance or weighing scale

* Balance as in equality or equilibrium

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Balance'' (1983 film), a Bulgaria ...

in a cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

. Enzyme inhibitors also control essential enzymes such as protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s or nucleases that, if left unchecked, may damage a cell. Many poisons produced by animals or plants are enzyme inhibitors that block the activity of crucial enzymes in prey or predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

s.

Many drug molecules are enzyme inhibitors that inhibit an aberrant human enzyme or an enzyme critical for the survival of a pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

such as a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsk ...

, bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were amon ...

or parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

. Examples include methotrexate (used in chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated to chemo and sometimes CTX or CTx) is a type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs ( chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) as part of a standardized chemotherapy regimen. Chemothe ...

and in treating rheumatic arthritis) and the protease inhibitors

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are medications that act by interfering with enzymes that cleave proteins. Some of the most well known are antiviral drugs widely used to treat HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. These protease inhibitors prevent viral replicat ...

used to treat HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ...

. Since anti-pathogen inhibitors generally target only one enzyme, such drugs are highly specific

Specific may refer to:

* Specificity (disambiguation)

* Specific, a cure or therapy for a specific illness

Law

* Specific deterrence, focussed on an individual

* Specific finding, intermediate verdict used by a jury in determining the fina ...

and generally produce few side effects in humans, provided that no analogous

Analogy (from Greek ''analogia'', "proportion", from ''ana-'' "upon, according to" lso "against", "anew"+ ''logos'' "ratio" lso "word, speech, reckoning" is a cognitive process of transferring information or meaning from a particular subject ...

enzyme is found in humans. (This is often the case, since such pathogens and humans are genetically distant.) Medicinal enzyme inhibitors often have low dissociation constants, meaning that only a minute amount of the inhibitor is required to inhibit the enzyme. A low concentration of the enzyme inhibitor reduces the risk for liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it ...

and kidney damage and other adverse drug reaction

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is a harmful, unintended result caused by taking medication. ADRs may occur following a single dose or prolonged administration of a drug or result from the combination of two or more drugs. The meaning of this term ...

s in humans. Hence the discovery and refinement of enzyme inhibitors is an active area of research in biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

and pharmacology.

Structural classes

Enzyme inhibitors are a chemically diverse set of substances that range in size from organicsmall molecule

Within the fields of molecular biology and pharmacology, a small molecule or micromolecule is a low molecular weight (≤ 1000 daltons) organic compound that may regulate a biological process, with a size on the order of 1 nm. Many drugs ...

s to macromolecular protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s.

Small molecule inhibitors include essential primary metabolites that inhibit upstream enzymes that produce those metabolites. This provides a negative feedback loop that prevents over production of metabolites and thus maintains cellular homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British also homoeostasis) (/hɒmɪə(ʊ)ˈsteɪsɪs/) is the state of steady internal, physical, and chemical conditions maintained by living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and ...

(steady internal conditions). Small molecule enzyme inhibitors also include secondary metabolite

Secondary metabolites, also called specialised metabolites, toxins, secondary products, or natural products, are organic compounds produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria, fungi, animals, or plants, which are not directly involved in the norma ...

s, which are not essential to the organism that produces them, but provide the organism with a evolutionary advantage, in that they can be used to repel predators or competing organisms or immobilize prey. In addition, many drugs are small molecule enzyme inhibitors that target either disease-modifying enzymes in the patient or enzymes in pathogens which are required for the growth and reproduction of the pathogen.

In addition to small molecules, some proteins act as enzyme inhibitors. The most prominent example are serpin

Serpins are a superfamily of proteins with similar structures that were first identified for their protease inhibition activity and are found in all kingdoms of life. The acronym serpin was originally coined because the first serpins to be id ...

s (serine protease inhibitors) which are produced by animals to protect against inappropriate enzyme activation and by plants to prevent predation. Another class of inhibitor proteins is the ribonuclease inhibitor

Ribonuclease inhibitor (RI) is a large (~450 residues, ~49 kDa), acidic (pI ~4.7), leucine-rich repeat protein that forms extremely tight complexes with certain ribonucleases. It is a major cellular protein, comprising ~0.1% of all cellular pr ...

s, which bind to ribonuclease

Ribonuclease (commonly abbreviated RNase) is a type of nuclease that catalyzes the degradation of RNA into smaller components. Ribonucleases can be divided into endoribonucleases and exoribonucleases, and comprise several sub-classes within ...

s in one of the tightest known protein–protein interaction

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are physical contacts of high specificity established between two or more protein molecules as a result of biochemical events steered by interactions that include electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding and th ...

s. A special case of protein enzyme inhibitors are zymogen

In biochemistry, a zymogen (), also called a proenzyme (), is an inactive precursor of an enzyme. A zymogen requires a biochemical change (such as a hydrolysis reaction revealing the active site, or changing the configuration to reveal the activ ...

s that contain an autoinhibitory N-terminal peptide that binds to the active site of enzyme that intramolecularly blocks its activity as a protective mechanism against uncontrolled catalysis. The N-terminal peptide is cleaved (split) from the zymogen enzyme precursor by another enzyme to release an active enzyme.

The binding site

In biochemistry and molecular biology, a binding site is a region on a macromolecule such as a protein that binds to another molecule with specificity. The binding partner of the macromolecule is often referred to as a ligand. Ligands may includ ...

of inhibitors on enzymes is most commonly the same site that binds the substrate of the enzyme. These active site inhibitors are known as orthosteric ("regular" orientation) inhibitors. The mechanism of orthosteric inhibition is simply to prevent substrate binding to the enzyme through direct competition which in turn prevents the enzyme from catalysing the conversion of substrates into products. Alternatively, the inhibitor can bind to a site remote from the enzyme active site. These are known as allosteric ("alternative" orientation) inhibitors. The mechanism of allosteric inhibition are varied and include changing the conformation (shape) of the enzyme such that it can no longer bind substrate ( kinetically indistinguishable from competitive orthosteric inhibition) or alternatively stabilise binding of substrate to the enzyme but lock the enzyme in a conformation which is no longer catalytically active.

Reversible inhibitors

Reversible inhibitors attach to enzymes with non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds,hydrophobic interaction

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, t ...

s and ionic bond

Ionic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that involves the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions, or between two atoms with sharply different electronegativities, and is the primary interaction occurring in ionic compounds ...

s. Multiple weak bonds between the inhibitor and the enzyme active site combine to produce strong and specific binding.

In contrast to irreversible inhibitors, reversible inhibitors generally do not undergo chemical reactions when bound to the enzyme and can be easily removed by dilution or dialysis. A special case are covalent reversible inhibitors that form a chemical bond with the enzyme, but the bond can be cleaved so the inhibition is fully reversible.

Reversible inhibitors are generally categorized into four types, as introduced by Cleland Cleland may refer to:

Places

* Cleland, South Australia, a suburb

** Cleland National Park, a protected area in South Australia

***Cleland Wildlife Park, a zoo within the area of Cleland National Park

* Cleland, North Lanarkshire, a small village ...

in 1963. They are classified according to the effect of the inhibitor on the ''Vmax'' (maximum reaction rate catalysed by the enzyme) and ''Km'' (the concentration of substrate resulting in half maximal enzyme activity) as the concentration of the enzyme's substrate is varied.

Competitive

Incompetitive inhibition

Competitive inhibition is interruption of a chemical pathway owing to one chemical substance inhibiting the effect of another by competing with it for binding or bonding. Any metabolic or chemical messenger system can potentially be affected b ...

, the substrate and inhibitor cannot bind to the enzyme at the same time. This usually results from the inhibitor having an affinity for the active site of an enzyme where the substrate also binds; the substrate and inhibitor ''compete'' for access to the enzyme's active site. This type of inhibition can be overcome by sufficiently high concentrations of substrate (''Vmax'' remains constant), i.e., by out-competing the inhibitor. However, the apparent ''Km'' will increase as it takes a higher concentration of the substrate to reach the ''Km'' point, or half the ''Vmax''. Competitive inhibitors are often similar in structure to the real substrate (see for example the "methotrexate versus folate" figure in the "Drugs" section).

Uncompetitive

Inuncompetitive inhibition

Uncompetitive inhibition, also known as anti-competitive inhibition, takes place when an enzyme inhibitor binds only to the complex formed between the enzyme and the substrate (biochemistry), substrate (the E-S complex). Uncompetitive inhibition ...

, the inhibitor binds only to the enzyme-substrate complex. This type of inhibition causes ''Vmax'' to decrease (maximum velocity decreases as a result of removing activated complex) and ''Km'' to decrease (due to better binding efficiency as a result of Le Chatelier's principle and the effective elimination of the ES complex thus decreasing the ''Km'' which indicates a higher binding affinity). Uncompetitive inhibition is rare.

Non-competitive

In non-competitive inhibition, the binding of the inhibitor to the enzyme reduces its activity but does not affect the binding of substrate. As a result, the extent of inhibition depends only on the concentration of the inhibitor. ''Vmax'' will decrease due to the inability for the reaction to proceed as efficiently, but ''Km'' will remain the same as the actual binding of the substrate, by definition, will still function properly.Mixed

In mixed inhibition, the inhibitor may bind to the enzyme whether or not the substrate has already bound. Hence mixed inhibition is a combination of competitive and noncompetitive inhibition. Furthermore, the affinity of the inhibitor for the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex may differ. By increasing concentrations of substrate this type of inhibition can be reduced (due to the competitive contribution), but not entirely overcome (due to the noncompetitive component). Although it is possible for mixed-type inhibitors to bind in the active site, this type of inhibition generally results from an allosteric effect where the inhibitor binds to a different site on an enzyme. Inhibitor binding to thisallosteric site

In biochemistry, allosteric regulation (or allosteric control) is the regulation of an enzyme by binding an effector molecule at a site other than the enzyme's active site.

The site to which the effector binds is termed the ''allosteric site ...

changes the conformation (that is, the tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may i ...

or three-dimensional shape) of the enzyme so that the affinity of the substrate for the active site is reduced.

These four types of inhibition can also be distinguished by the effect of increasing the substrate concentration on the degree of inhibition caused by a given amount of inhibitor. For competitive inhibition the degree of inhibition is reduced by increasing for noncompetitive inhibition the degree of inhibition is unchanged, and for uncompetitive (also called anticompetitive) inhibition the degree of inhibition increases with

Quantitative description

Reversible inhibition can be described quantitatively in terms of the inhibitor's binding to the enzyme and to the enzyme-substrate complex, and its effects on the kinetic constants of the enzyme. In the classic Michaelis-Menten scheme (shown in the "inhibition mechanism schematic" diagram), an enzyme (E) binds to its substrate (S) to form the enzyme–substrate complex ES. Upon catalysis, this complex breaks down to release product P and free enzyme. The inhibitor (I) can bind to either E or ES with the dissociation constants ''K''i or ''K''i', respectively. * Competitive inhibitors can bind to E, but not to ES. Competitive inhibition increases ''K''m (i.e., the inhibitor interferes with substrate binding), but does not affect ''V''max (the inhibitor does not hamper catalysis in ES because it cannot bind to ES). *Uncompetitive inhibitors bind to ES. Uncompetitive inhibition decreases both ''K''m and ''V''max. The inhibitor affects substrate binding by increasing the enzyme's affinity for the substrate (decreasing ''K''m) as well as hampering catalysis (decreases ''V''max). * Non-competitive inhibitors have identical affinities for E and ES (''K''i = ''K''i'). Non-competitive inhibition does not change ''K''m (i.e., it does not affect substrate binding) but decreases ''V''max (i.e., inhibitor binding hampers catalysis). * Mixed-type inhibitors bind to both E and ES, but their affinities for these two forms of the enzyme are different (''K''i ≠ ''K''i'). Thus, mixed-type inhibitors affect substrate binding (increase or decrease ''K''m) and hamper catalysis in the ES complex (decrease ''V''max). When an enzyme has multiple substrates, inhibitors can show different types of inhibition depending on which substrate is considered. This results from the active site containing two different binding sites within the active site, one for each substrate. For example, an inhibitor might compete with substrate A for the first binding site, but be a non-competitive inhibitor with respect to substrate B in the second binding site. Traditionally reversible enzyme inhibitors have been classified as competitive, uncompetitive, or non-competitive, according to their effects on ''K''m and ''V''max. These three types of inhibition result respectively from the inhibitor binding only to the enzyme E in the absence of substrate S, to the enzyme–substrate complex ES, or to both. The division of these classes arises from a problem in their derivation and results in the need to use two different binding constants for one binding event. It is further assumed that binding of the inhibitor to the enzyme results in 100% inhibition and fails to consider the possibility of partial inhibition. The common form of the inhibitory term also obscures the relationship between the inhibitor binding to the enzyme and its relationship to any other binding term be it the Michaelis–Menten equation or a dose response curve associated with ligand receptor binding. To demonstrate the relationship the following rearrangement can be made: : This rearrangement demonstrates that similar to the Michaelis–Menten equation, the maximal rate of reaction depends on the proportion of the enzyme population interacting with its substrate. fraction of the enzyme population bound by substrate : fraction of the enzyme population bound by inhibitor : the effect of the inhibitor is a result of the percent of the enzyme population interacting with inhibitor. The only problem with this equation in its present form is that it assumes absolute inhibition of the enzyme with inhibitor binding, when in fact there can be a wide range of effects anywhere from 100% inhibition of substrate turn over to no inhibition. To account for this the equation can be easily modified to allow for different degrees of inhibition by including a delta ''V''max term. : or : This term can then define the residual enzymatic activity present when the inhibitor is interacting with individual enzymes in the population. However the inclusion of this term has the added value of allowing for the possibility of activation if the secondary ''V''max term turns out to be higher than the initial term. To account for the possibly of activation as well the notation can then be rewritten replacing the inhibitor "I" with a modifier term (stimulator or inhibitor) denoted here as "X". : While this terminology results in a simplified way of dealing with kinetic effects relating to the maximum velocity of the Michaelis–Menten equation, it highlights potential problems with the term used to describe effects relating to the ''K''m. The ''K''m relating to the affinity of the enzyme for the substrate should in most cases relate to potential changes in the binding site of the enzyme which would directly result from enzyme inhibitor interactions. As such a term similar to the delta ''V''max term proposed above to modulate ''V''max should be appropriate in most situations: :Dissociation constants

An enzyme inhibitor is characterised by its dissociation constant ''K''i, the concentration at which the inhibitor half occupies the enzyme. In non-competitive inhibition, the inhibitor can also bind to the enzyme-substrate complex, and the presence of bound substrate can change the affinity of the inhibitor for the enzyme, resulting in a second dissociation constant ''K''i'. Hence ''K''i and ''K''i' are the dissociation constants of the inhibitor for the enzyme and to the enzyme-substrate complex, respectively. The enzyme-inhibitor constant ''K''i can be measured directly by various methods; one especially accurate method isisothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) is a physical technique used to determine the thermodynamic parameters of interactions in solution. It is most often used to study the binding of small molecules (such as medicinal compounds) to larger macro ...

, in which the inhibitor is titrated into a solution of enzyme and the heat released or absorbed is measured. However, the other dissociation constant ''K''i' is difficult to measure directly, since the enzyme-substrate complex is short-lived and undergoing a chemical reaction to form the product. Hence, ''K''i' is usually measured indirectly, by observing the enzyme activity

Enzyme assays are laboratory methods for measuring enzymatic activity. They are vital for the study of enzyme kinetics and enzyme inhibition.

Enzyme units

The quantity or concentration of an enzyme can be expressed in molar amounts, as with a ...

under various substrate and inhibitor concentrations, and fitting the data via nonlinear regression

In statistics, nonlinear regression is a form of regression analysis in which observational data are modeled by a function which is a nonlinear combination of the model parameters and depends on one or more independent variables. The data are fi ...

to a modified Michaelis–Menten equation.

:

where the modifying factors α and α' are defined by the inhibitor concentration and its two dissociation constants

:

:

Thus, in the presence of the inhibitor, the enzyme's effective ''K''m and ''V''max become (α/α')''K''m and (1/α')''V''max, respectively. However, the modified Michaelis-Menten equation assumes that binding of the inhibitor to the enzyme has reached equilibrium, which may be a very slow process for inhibitors with sub-nanomolar dissociation constants. In these cases, the inhibition becomes effectively irreversible, hence it is more practical to treat such tight-binding inhibitors as irreversible (see below).

The effects of different types of reversible enzyme inhibitors on enzymatic activity can be visualised using graphical representations of the Michaelis–Menten equation, such as Lineweaver–Burk, Eadie-Hofstee or Hanes-Woolf plots. An illustration is provided by the three Lineweaver–Burk plots depicted in the ''Lineweaver–Burk diagrams'' figure. In the top diagram, the competitive inhibition lines intersect on the ''y''-axis, illustrating that such inhibitors do not affect ''V''max. In the bottom diagram, the non-competitive inhibition lines intersect on the ''x''-axis, showing these inhibitors do not affect ''K''m. However, since it can be difficult to estimate ''K''i and ''K''i' accurately from such plots, it is advisable to estimate these constants using more reliable nonlinear regression methods.

Special cases

Partially competitive

The mechanism of partially competitive inhibition is similar to that of non-competitive, except that the EIS complex has catalytic activity, which may be lower or even higher (partially competitive activation) than that of the enzyme–substrate (ES) complex. This inhibition typically displays a lower ''V''max, but an unaffected ''K''m value.Substrate or product

Substrate or product inhibition is where either an enzymes substrate or product also act as an inhibitor. This inhibition may follow the competitive, uncompetitive or mixed patterns. In substrate inhibition there is a progressive decrease in activity at high substrate concentrations, potentially from an enzyme having two competing substrate-binding sites. At low substrate, the high-affinity site is occupied and normal kinetics are followed. However, at higher concentrations, the second inhibitory site becomes occupied, inhibiting the enzyme. Product inhibition (either the enzyme's own product, or a product to an enzyme downstream in its metabolic pathway) is often a regulatory feature in metabolism and can be a form of negative feedback.Slow-tight

Slow-tight inhibition occurs when the initial enzyme–inhibitor complex EI undergoesconformational isomerism

In chemistry, conformational isomerism is a form of stereoisomerism in which the isomers can be interconverted just by rotations about formally single bonds (refer to figure on single bond rotation). While any two arrangements of atoms in a mo ...

(a change in shape) to a second more tightly held complex, EI*, but the overall inhibition process is reversible. This manifests itself as slowly increasing enzyme inhibition. Under these conditions, traditional Michaelis–Menten kinetics give a false value for ''K''i, which is time–dependent. The true value of ''K''i can be obtained through more complex analysis of the on (''k''on) and off (''k''off) rate constants for inhibitor association with kinetics similar to irreversible inhibition.

Multi-substrate analogues

Multi-substrate analogue inhibitors are high affinity selective inhibitors that can be prepared for enzymes that catalyse reactions with more than one substrate by capturing the binding energy of each of those substrate into one molecule. For example, in the formyl transfer reactions of purine biosynthesis, a potent Multi-substrate Adduct Inhibitor (MAI) to glycinamide ribonucleotide (GAR) TFase was prepared synthetically by linking analogues of the GAR substrate and the N-10-formyl tetrahydrofolate cofactor together to produce thioglycinamide ribonucleotide dideazafolate (TGDDF), or enzymatically from the natural GAR substrate to yield GDDF. Here the subnanomolar dissociation constant (KD) of TGDDF was greater than predicted presumably due toentropic

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynam ...

advantages gained and/or positive interactions acquired through the atoms linking the components. MAIs have also been observed to be produced in cells by reactions of pro-drugs such as isoniazid

Isoniazid, also known as isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH), is an antibiotic used for the treatment of tuberculosis. For active tuberculosis it is often used together with rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and either streptomycin or ethambutol. For la ...

or enzyme inhibitor ligands (for example, PTC124) with cellular cofactors such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms o ...

(ATP) respectively.

Examples

As enzymes have evolved to bind their substrates tightly, and most reversible inhibitors bind in the active site of enzymes, it is unsurprising that some of these inhibitors are strikingly similar in structure to the substrates of their targets. Inhibitors of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) are prominent examples. Other examples of these substrate mimics are theprotease inhibitors

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are medications that act by interfering with enzymes that cleave proteins. Some of the most well known are antiviral drugs widely used to treat HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. These protease inhibitors prevent viral replicat ...

, a therapeutically effective class of antiretroviral drug

The management of HIV/AIDS normally includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs as a strategy to control HIV infection. There are several classes of antiretroviral agents that act on different stages of the HIV life-cycle. The use of multi ...

s used to treat HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ...

. The structure of ritonavir

Ritonavir, sold under the brand name Norvir, is an antiretroviral drug used along with other medications to treat HIV/AIDS. This combination treatment is known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Ritonavir is a protease inhibitor ...

, a peptidomimetic

A peptidomimetic is a small protein-like chain designed to mimic a peptide. They typically arise either from modification of an existing peptide, or by designing similar systems that mimic peptides, such as peptoids and β-peptides. Irrespective ...

(peptide mimic) protease inhibitor containing three peptide bonds, as shown in the "competitive inhibitor examples" figure. As this drug resembles the peptide that is the substrate of the HIV protease, it competes with the substrate in the enzyme's active site.

Enzyme inhibitors are often designed to mimic the transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked ...

or intermediate of an enzyme-catalysed reaction. This ensures that the inhibitor exploits the transition state stabilising effect of the enzyme, resulting in a better binding affinity (lower ''K''i) than substrate-based designs. An example of such a transition state inhibitor is the antiviral drug oseltamivir; this drug mimics the planar nature of the ring oxonium ion

In chemistry, an oxonium ion is any cation containing an oxygen atom that has three bonds and 1+ formal charge. The simplest oxonium ion is the hydronium ion ().

Alkyloxonium

Hydronium is one of a series of oxonium ions with the formula R''n' ...

in the reaction of the viral enzyme neuraminidase

Exo-α-sialidase (EC 3.2.1.18, sialidase, neuraminidase; systematic name acetylneuraminyl hydrolase) is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

: Hydrolysis of α-(2→3)-, α-(2→6)-, α-(2→8)- glyc ...

.

However, not all inhibitors are based on the structures of substrates. For example, the structure of another HIV protease inhibitor tipranavir is not based on a peptide and has no obvious structural similarity to a protein substrate. These non-peptide inhibitors can be more stable than inhibitors containing peptide bonds, because they will not be substrates for peptidase

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the for ...

s and are less likely to be degraded.

In drug design it is important to consider the concentrations of substrates to which the target enzymes are exposed. For example, some protein kinase

A protein kinase is a kinase which selectively modifies other proteins by covalently adding phosphates to them (phosphorylation) as opposed to kinases which modify lipids, carbohydrates, or other molecules. Phosphorylation usually results in a fu ...

inhibitors have chemical structures that are similar to ATP, one of the substrates of these enzymes. However, drugs that are simple competitive inhibitors will have to compete with the high concentrations of ATP in the cell. Protein kinases can also be inhibited by competition at the binding sites where the kinases interact with their substrate proteins, and most proteins are present inside cells at concentrations much lower than the concentration of ATP. As a consequence, if two protein kinase inhibitors both bind in the active site with similar affinity, but only one has to compete with ATP, then the competitive inhibitor at the protein-binding site will inhibit the enzyme more effectively.

Irreversible inhibitors

Types

Irreversible inhibitorscovalent

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

ly bind to an enzyme, and this type of inhibition can therefore not be readily reversed. Irreversible inhibitors often contain reactive functional groups such as nitrogen mustards, aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

s, haloalkanes, alkene

In organic chemistry, an alkene is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond.

Alkene is often used as synonym of olefin, that is, any hydrocarbon containing one or more double bonds.H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, an ...

s, Michael acceptor

In organic chemistry, the Michael reaction or Michael addition is a reaction between a Michael donor (an enolate or other nucleophile) and a Michael acceptor (usually an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl) to produce a Michael adduct by creating a carbo ...

s, phenyl sulfonates, or fluorophosphonates. These electrophilic groups react with amino acid side chains to form covalent adduct

An adduct (from the Latin ''adductus'', "drawn toward" alternatively, a contraction of "addition product") is a product of a direct addition of two or more distinct molecules, resulting in a single reaction product containing all atoms of all co ...

s. The residues modified are those with side chains containing nucleophiles such as hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydro ...

or sulfhydryl groups; these include the amino acids serine (that reacts with DFP, see the "DFP reaction" diagram), and also cysteine, threonine, or tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the G ...

.

Irreversible inhibition is different from irreversible enzyme inactivation. Irreversible inhibitors are generally specific for one class of enzyme and do not inactivate all proteins; they do not function by destroying protein structure

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monom ...

but by specifically altering the active site of their target. For example, extremes of pH or temperature usually cause denaturation of all protein structure, but this is a non-specific effect. Similarly, some non-specific chemical treatments destroy protein structure: for example, heating in concentrated hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbol ...

will hydrolyse the peptide bonds holding proteins together, releasing free amino acids.

Irreversible inhibitors display time-dependent inhibition and their potency therefore cannot be characterised by an IC50 value. This is because the amount of active enzyme at a given concentration of irreversible inhibitor will be different depending on how long the inhibitor is pre-incubated with the enzyme. Instead, ''k''obs/ 'I''values are used, where ''k''obs is the observed pseudo-first order rate of inactivation (obtained by plotting the log of % activity versus time) and 'I''is the concentration of inhibitor. The ''k''obs/ 'I''parameter is valid as long as the inhibitor does not saturate binding with the enzyme (in which case ''k''obs = ''k''inact) where ''k''inact is the rate of inactivation.

Measuring

Irreversible inhibitors first form a reversible non-covalent complex with the enzyme (EI or ESI). Subsequently a chemical reaction occurs between the enzyme and inhibitor to produce the covalently modified "dead-end complex" EI* (an irreversible covalent complex). The rate at which EI* is formed is called the inactivation rate or ''k''inact. Since formation of EI may compete with ES, binding of irreversible inhibitors can be prevented by competition either with substrate or with a second, reversible inhibitor. This protection effect is good evidence of a specific reaction of the irreversible inhibitor with the active site. The binding and inactivation steps of this reaction are investigated by incubating the enzyme with inhibitor and assaying the amount of activity remaining over time. The activity will be decreased in a time-dependent manner, usually following exponential decay. Fitting these data to arate equation

In chemistry, the rate law or rate equation for a reaction is an equation that links the initial or forward reaction rate with the concentrations or pressures of the reactants and constant parameters (normally rate coefficients and partial reac ...

gives the rate of inactivation at this concentration of inhibitor. This is done at several different concentrations of inhibitor. If a reversible EI complex is involved the inactivation rate will be saturable and fitting this curve will give ''k''inact and ''K''i.

Another method that is widely used in these analyses is mass spectrometry. Here, accurate measurement of the mass of the unmodified native enzyme and the inactivated enzyme gives the increase in mass caused by reaction with the inhibitor and shows the stoichiometry of the reaction. This is usually done using a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer. In a complementary technique, peptide mass fingerprinting involves digestion of the native and modified protein with a protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

such as trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the d ...

. This will produce a set of peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

...

s that can be analysed using a mass spectrometer. The peptide that changes in mass after reaction with the inhibitor will be the one that contains the site of modification.

Slow binding

Not all irreversible inhibitors form covalent adducts with their enzyme targets. Some reversible inhibitors bind so tightly to their target enzyme that they are essentially irreversible. These tight-binding inhibitors may show kinetics similar to covalent irreversible inhibitors. In these cases, some of these inhibitors rapidly bind to the enzyme in a low-affinity EI complex and this then undergoes a slower rearrangement to a very tightly bound EI* complex (see the "irreversible inhibition mechanism" diagram). This kinetic behaviour is called slow-binding. This slow rearrangement after binding often involves a conformational change as the enzyme "clamps down" around the inhibitor molecule. Examples of slow-binding inhibitors include some important drugs, such methotrexate,allopurinol

Allopurinol is a medication used to decrease high blood uric acid levels. It is specifically used to prevent gout, prevent specific types of kidney stones and for the high uric acid levels that can occur with chemotherapy. It is taken by mouth ...

, and the activated form of acyclovir

Aciclovir (ACV), also known as acyclovir, is an antiviral medication. It is primarily used for the treatment of herpes simplex virus infections, chickenpox, and shingles. Other uses include prevention of cytomegalovirus infections following t ...

.

Some examples

Diisopropylfluorophosphate

Diisopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP) or Isoflurophate is an oily, colorless liquid with the chemical formula C6H14FO3P. It is used in medicine and as an organophosphorus insecticide. It is stable, but undergoes hydrolysis when subjected to moisture ...

(DFP) is an example of an irreversible protease inhibitor (see the "DFP reaction" diagram). The enzyme hydrolyses the phosphorus–fluorine bond, but the phosphate residue remains bound to the serine in the active site, deactivating it. Similarly, DFP also reacts with the active site of acetylcholine esterase

Acetylcholinesterase (HGNC symbol ACHE; EC 3.1.1.7; systematic name acetylcholine acetylhydrolase), also known as AChE, AChase or acetylhydrolase, is the primary cholinesterase in the body. It is an enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of acet ...

in the synapses of neurons, and consequently is a potent neurotoxin, with a lethal dose of less than 100 mg.

Suicide inhibition

In biochemistry, suicide inhibition, also known as suicide inactivation or mechanism-based inhibition, is an irreversible form of enzyme inhibition that occurs when an enzyme binds a substrate analog and forms an irreversible complex with it th ...

is an unusual type of irreversible inhibition where the enzyme converts the inhibitor into a reactive form in its active site. An example is the inhibitor of polyamine biosynthesis, α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), which is an analogue of the amino acid ornithine

Ornithine is a non-proteinogenic amino acid that plays a role in the urea cycle. Ornithine is abnormally accumulated in the body in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. The radical is ornithyl.

Role in urea cycle

L-Ornithine is one of the produ ...

, and is used to treat African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Ornithine decarboxylase

The enzyme ornithine decarboxylase (, ODC) catalyzes the decarboxylation of ornithine (a product of the urea cycle) to form putrescine. This reaction is the committed step in polyamine synthesis. In humans, this protein has 461 amino acids a ...

can catalyse the decarboxylation of DFMO instead of ornithine (see the "DFMO inhibitor mechanism" diagram). However, this decarboxylation reaction is followed by the elimination of a fluorine atom, which converts this catalytic intermediate into a conjugated imine

In organic chemistry, an imine ( or ) is a functional group or organic compound containing a carbon–nitrogen double bond (). The nitrogen atom can be attached to a hydrogen or an organic group (R). The carbon atom has two additional single bon ...

, a highly electrophilic species. This reactive form of DFMO then reacts with either a cysteine or lysine residue in the active site to irreversibly inactivate the enzyme.

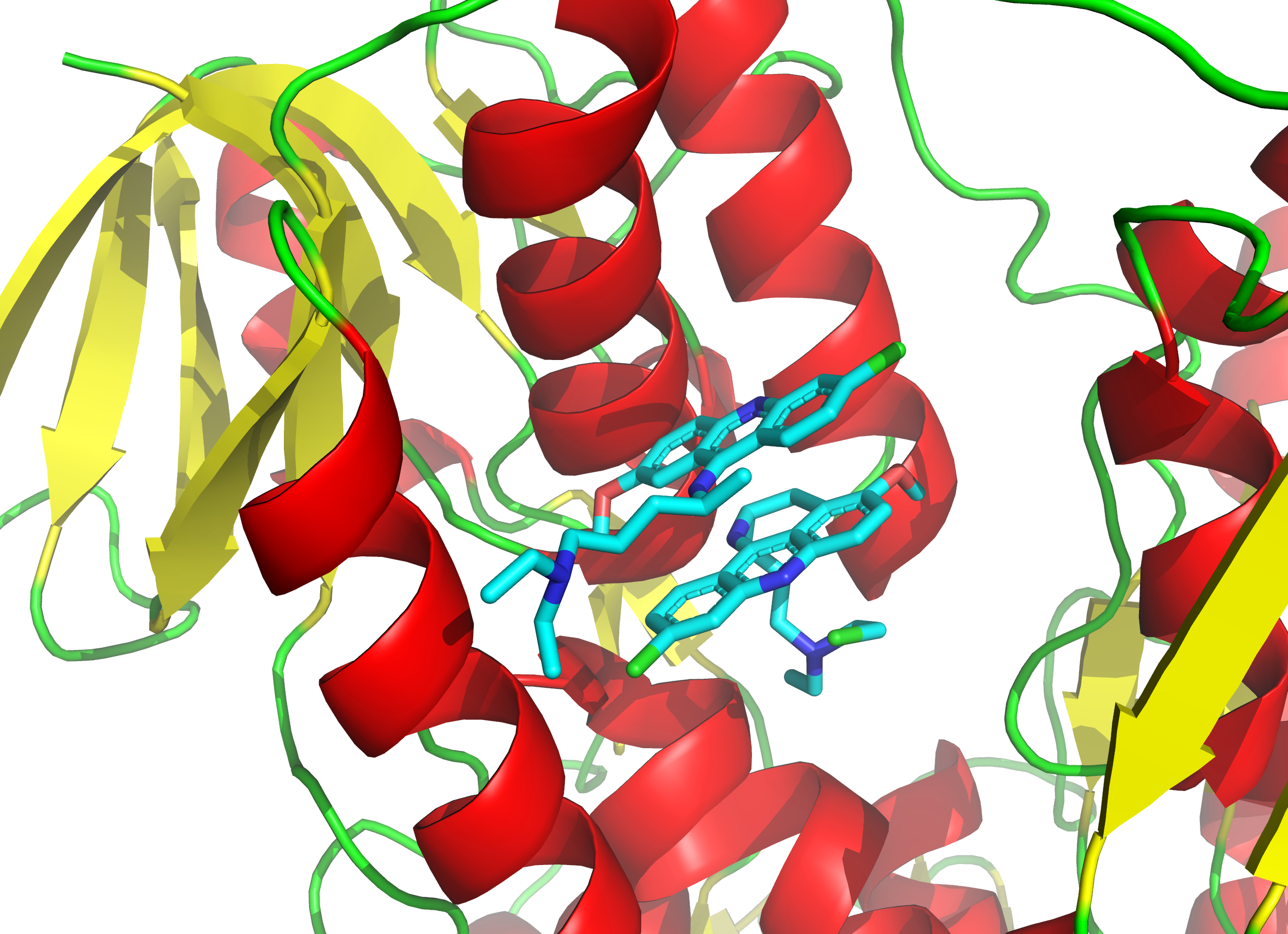

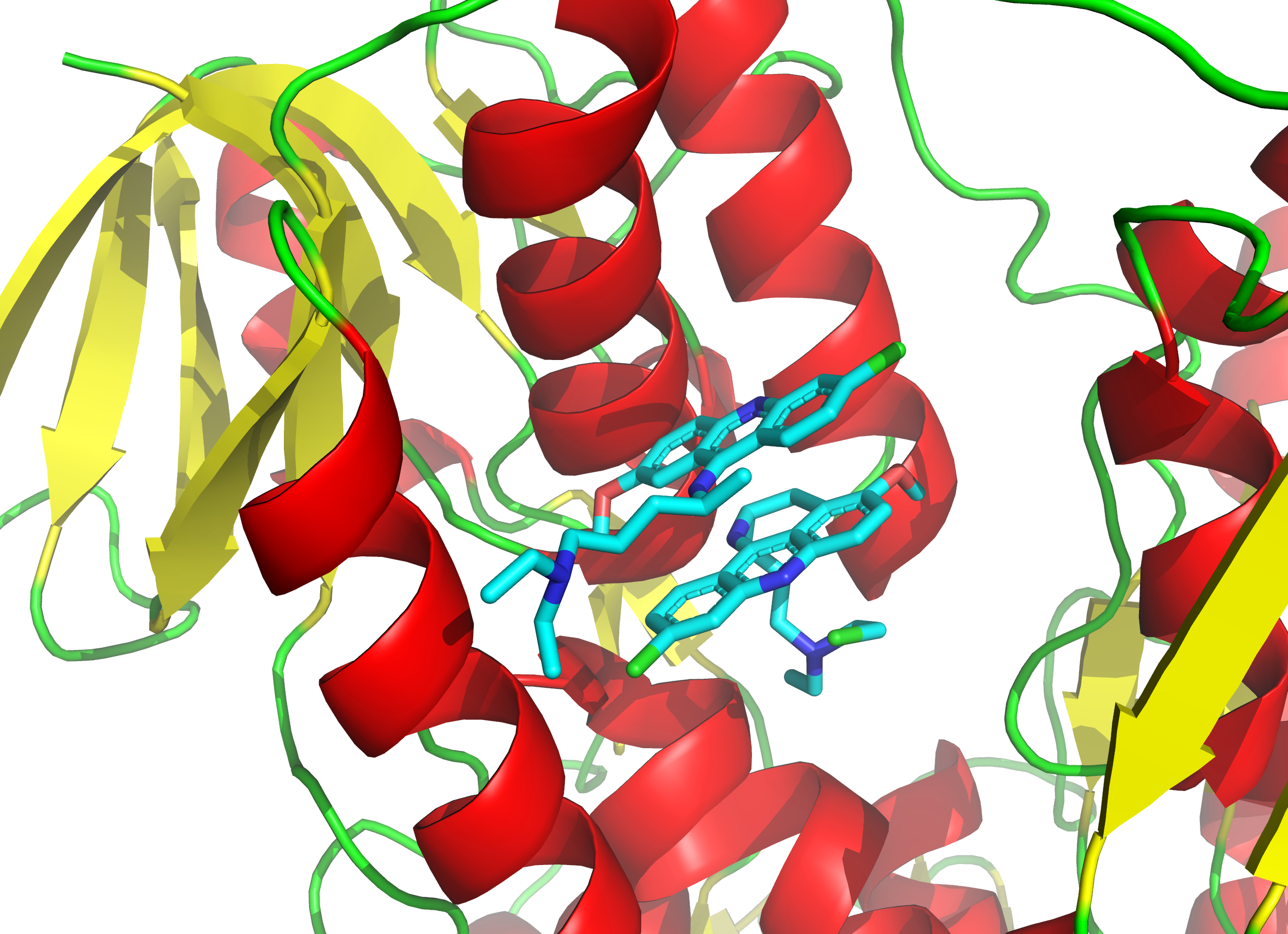

Since irreversible inhibition often involves the initial formation of a non-covalent enzyme inhibitor (EI) complex, it is sometimes possible for an inhibitor to bind to an enzyme in more than one way. For example, in the figure showing trypanothione reductase from the human protozoan parasite ''Trypanosoma cruzi

''Trypanosoma cruzi'' is a species of parasitic euglenoids. Among the protozoa, the trypanosomes characteristically bore tissue in another organism and feed on blood (primarily) and also lymph. This behaviour causes disease or the likelihood o ...

'', two molecules of an inhibitor called ''quinacrine mustard'' are bound in its active site. The top molecule is bound reversibly, but the lower one is bound covalently as it has reacted with an amino acid residue through its nitrogen mustard group.

Applications

Enzyme inhibitors are found in nature and also produced artificially in the laboratory. Naturally occurring enzyme inhibitors regulate many metabolic processes and are essential for life. In addition, naturally produced poisons are often enzyme inhibitors that have evolved for use as toxic agents against predators, prey, and competing organisms. These natural toxins include some of the most poisonous substances known. Artificial inhibitors are often used as drugs, but can also be insecticides such as malathion, herbicides such asglyphosate

Glyphosate (IUPAC name: ''N''-(phosphonomethyl)glycine) is a broad-spectrum systemic herbicide and crop desiccant. It is an organophosphorus compound, specifically a phosphonate, which acts by inhibiting the plant enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshik ...

, or disinfectants

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than st ...

such as triclosan

Triclosan (sometimes abbreviated as TCS) is an antibacterial and antifungal agent present in some consumer products, including toothpaste, soaps, detergents, toys, and surgical cleaning treatments. It is similar in its uses and mechanism of ac ...

. Other artificial enzyme inhibitors block acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme which breaks down acetylcholine, and are used as nerve agent

Nerve agents, sometimes also called nerve gases, are a class of organic chemicals that disrupt the mechanisms by which nerves transfer messages to organs. The disruption is caused by the blocking of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme that ...

s in chemical warfare.

Metabolic regulation

Enzyme inhibition is a common feature ofmetabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell. The reactants, products, and intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are modified by a sequence of chemical reac ...

control in cells. Metabolic flux through a pathway is often regulated by a pathway's metabolites

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, ...

acting as inhibitors and enhancers for the enzymes in that same pathway. The glycolytic pathway

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvic acid, pyruvate (). The Thermodynamic free energy, free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and NADH, red ...

is a classic example. This catabolic pathway consumes glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

and produces ATP, NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an aden ...

and pyruvate. A key step for the regulation of glycolysis is an early reaction in the pathway catalysed by phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK1). When ATP levels rise, ATP binds an allosteric site in PFK1 to decrease the rate of the enzyme reaction; glycolysis is inhibited and ATP production falls. This negative feedback control helps maintain a steady concentration of ATP in the cell. However, metabolic pathways are not just regulated through inhibition since enzyme activation is equally important. With respect to PFK1, fructose 2,6-bisphosphate and ADP are examples of metabolites that are allosteric activators.

Physiological enzyme inhibition can also be produced by specific protein inhibitors. This mechanism occurs in the pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an en ...

, which synthesises many digestive precursor enzymes known as zymogen

In biochemistry, a zymogen (), also called a proenzyme (), is an inactive precursor of an enzyme. A zymogen requires a biochemical change (such as a hydrolysis reaction revealing the active site, or changing the configuration to reveal the activ ...

s. Many of these are activated by the trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the d ...

protease, so it is important to inhibit the activity of trypsin in the pancreas to prevent the organ from digesting itself. One way in which the activity of trypsin is controlled is the production of a specific and potent trypsin inhibitor A trypsin inhibitor (TI) is a protein and a type of serine protease inhibitor (serpin) that reduces the biological activity of trypsin by controlling the activation and catalytic reactions of proteins. Trypsin is an enzyme involved in the breakdown ...

protein in the pancreas. This inhibitor binds tightly to trypsin, preventing the trypsin activity that would otherwise be detrimental to the organ. Although the trypsin inhibitor is a protein, it avoids being hydrolysed as a substrate by the protease by excluding water from trypsin's active site and destabilising the transition state. Other examples of physiological enzyme inhibitor proteins include the barstar

Barstar is a small protein synthesized by the bacterium ''Bacillus amyloliquefaciens''. Its function is to inhibit the ribonuclease activity of its binding partner barnase

Barnase (a portmanteau of "BActerial" "RiboNucleASE") is a bacterial pr ...

inhibitor of the bacterial ribonuclease barnase

Barnase (a portmanteau of "BActerial" "RiboNucleASE") is a bacterial protein that consists of 110 amino acids and has ribonuclease activity. It is synthesized and secreted by the bacterium '' Bacillus amyloliquefaciens'', but is lethal to the cel ...

.

Natural poisons

Animals and plants have evolved to synthesise a vast array of poisonous products including

Animals and plants have evolved to synthesise a vast array of poisonous products including secondary metabolite

Secondary metabolites, also called specialised metabolites, toxins, secondary products, or natural products, are organic compounds produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria, fungi, animals, or plants, which are not directly involved in the norma ...

s, peptides and proteins that can act as inhibitors. Natural toxins are usually small organic molecules and are so diverse that there are probably natural inhibitors for most metabolic processes. The metabolic processes targeted by natural poisons encompass more than enzymes in metabolic pathways and can also include the inhibition of receptor, channel and structural protein functions in a cell. For example, paclitaxel

Paclitaxel (PTX), sold under the brand name Taxol among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of types of cancer. This includes ovarian cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical canc ...

(taxol), an organic molecule found in the Pacific yew tree, binds tightly to tubulin

Tubulin in molecular biology can refer either to the tubulin protein superfamily of globular proteins, or one of the member proteins of that superfamily. α- and β-tubulins polymerize into microtubules, a major component of the eukaryotic cytoske ...

dimers and inhibits their assembly into microtubules in the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is com ...

.

Many natural poisons act as neurotoxins that can cause paralysis leading to death and function for defence against predators or in hunting and capturing prey. Some of these natural inhibitors, despite their toxic attributes, are valuable for therapeutic uses at lower doses. An example of a neurotoxin are the glycoalkaloid

Glycoalkaloids are a family of chemical compounds derived from alkaloids to which sugar groups are appended. Several are potentially toxic, most notably the poisons commonly found in the plant species ''Solanum dulcamara'' (bittersweet nightshade) ...

s, from the plant species in the family Solanaceae (includes potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

, tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

and eggplant), that are acetylcholinesterase inhibitor

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) also often called cholinesterase inhibitors, inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase from breaking down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into choline and acetate, thereby increasing both the level and ...

s. Inhibition of this enzyme causes an uncontrolled increase in the acetylcholine neurotransmitter, muscular paralysis and then death. Neurotoxicity can also result from the inhibition of receptors; for example, atropine from deadly nightshade ('' Atropa belladonna'') that functions as a competitive antagonist of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.

Although many natural toxins are secondary metabolites, these poisons also include peptides and proteins. An example of a toxic peptide is alpha-amanitin, which is found in relatives of the death cap mushroom. This is a potent enzyme inhibitor, in this case preventing the RNA polymerase II

RNA polymerase II (RNAP II and Pol II) is a multiprotein complex that transcribes DNA into precursors of messenger RNA (mRNA) and most small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and microRNA. It is one of the three RNAP enzymes found in the nucleus of eukaryo ...

enzyme from transcribing DNA. The algal toxin microcystin

Microcystins—or cyanoginosins—are a class of toxins produced by certain freshwater cyanobacteria, commonly known as blue-green algae. Over 250 different microcystins have been discovered so far, of which microcystin-LR is the most common. C ...

is also a peptide and is an inhibitor of protein phosphatases. This toxin can contaminate water supplies after algal bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in freshwater or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompass ...

s and is a known carcinogen that can also cause acute liver haemorrhage and death at higher doses.

Proteins can also be natural poisons or antinutrient

Antinutrients are natural or synthetic compounds that interfere with the absorption of nutrients. Nutrition studies focus on antinutrients commonly found in food sources and beverages. Antinutrients may take the form of drugs, chemicals that natur ...

s, such as the trypsin inhibitor A trypsin inhibitor (TI) is a protein and a type of serine protease inhibitor (serpin) that reduces the biological activity of trypsin by controlling the activation and catalytic reactions of proteins. Trypsin is an enzyme involved in the breakdown ...

s (discussed in the "metabolic regulation" section above) that are found in some legumes. A less common class of toxins are toxic enzymes: these act as irreversible inhibitors of their target enzymes and work by chemically modifying their substrate enzymes. An example is ricin, an extremely potent protein toxin found in castor oil beans. This enzyme is a glycosidase that inactivates ribosomes. Since ricin is a catalytic irreversible inhibitor, this allows just a single molecule of ricin to kill a cell.

Drugs

aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

is a widely used drug that acts as a suicide inhibitor of the cyclooxygenase

Cyclooxygenase (COX), officially known as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (PTGS), is an enzyme (specifically, a family of isozymes, ) that is responsible for formation of prostanoids, including thromboxane and prostaglandins such as pr ...

enzyme. This inhibition in turn suppresses the production of proinflammatory prostaglandins and thus aspirin may be used to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation.

an estimated 29% of approved drugs are enzyme inhibitors of which approximately one-fifth are kinase inhibitors. A notable class of kinase drug targets is the receptor tyrosine kinase

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are the high- affinity cell surface receptors for many polypeptide growth factors, cytokines, and hormones. Of the 90 unique tyrosine kinase genes identified in the human genome, 58 encode receptor tyrosine kin ...

s which are essential enzymes that regulate cell growth; their over-activation may result in cancer. Hence kinase inhibitors such as imatinib are frequently used to treat malignancies. Janus kinase

Janus kinase (JAK) is a family of intracellular, non-receptor tyrosine kinases that transduce cytokine-mediated signals via the JAK-STAT pathway. They were initially named "just another kinase" 1 and 2 (since they were just two of many discoveries ...

s are another notable example of drug enzyme targets. Inhibitors of Janus kinases block the production of inflammatory cytokine An inflammatory cytokine or proinflammatory cytokine is a type of signaling molecule (a cytokine) that is secreted from immune cells like helper T cells (Th) and macrophages, and certain other cell types that promote inflammation. They include int ...

s and hence these inhibitors are used to treat a variety of inflammatory disease

Inflammation (from la, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels, and molec ...

s in including arthritis, asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, co ...

, and Crohn's disease.

An example of the structural similarity of some inhibitors to the substrates of the enzymes they target is seen in the figure comparing the drug methotrexate to folic acid

Folate, also known as vitamin B9 and folacin, is one of the B vitamins. Manufactured folic acid, which is converted into folate by the body, is used as a dietary supplement and in food fortification as it is more stable during processing and ...

. Folic acid is the oxidised form of the substrate of dihydrofolate reductase, an enzyme that is potently inhibited by methotrexate. Methotrexate blocks the action of dihydrofolate reductase and thereby halts thymidine

Thymidine (symbol dT or dThd), also known as deoxythymidine, deoxyribosylthymine, or thymine deoxyriboside, is a pyrimidine deoxynucleoside. Deoxythymidine is the DNA nucleoside T, which pairs with deoxyadenosine (A) in double-stranded DNA. ...

biosynthesis. This block of nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecule ...

biosynthesis is selectively toxic to rapidly growing cells, therefore methotrexate is often used in cancer chemotherapy.

A common treatment for erectile dysfunction is sildenafil (Viagra). This compound is a potent inhibitor of cGMP specific phosphodiesterase type 5, the enzyme that degrades the signalling molecule cyclic guanosine monophosphate

Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) is a cyclic nucleotide derived from guanosine triphosphate (GTP). cGMP acts as a second messenger much like cyclic AMP. Its most likely mechanism of action is activation of intracellular protein kinases in r ...

. This signalling molecule triggers smooth muscle relaxation and allows blood flow into the corpus cavernosum, which causes an erection. Since the drug decreases the activity of the enzyme that halts the signal, it makes this signal last for a longer period of time.

Antibiotics

Drugs are also used to inhibit enzymes needed for the survival of pathogens. For example, bacteria are surrounded by a thick cell wall made of a net-like polymer called

Drugs are also used to inhibit enzymes needed for the survival of pathogens. For example, bacteria are surrounded by a thick cell wall made of a net-like polymer called peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like peptidoglycan layer outside the plasma membrane, the rigid cell wall (murein sacculus) characteristic of most ba ...

. Many antibiotics such as penicillin and vancomycin

Vancomycin is a glycopeptide antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections. It is recommended intravenously as a treatment for complicated skin infections, bloodstream infections, endocarditis, bone and joint infections, ...

inhibit the enzymes that produce and then cross-link the strands of this polymer together. This causes the cell wall to lose strength and the bacteria to burst. In the figure, a molecule of penicillin (shown in a ball-and-stick form) is shown bound to its target, the transpeptidase from the bacteria ''Streptomyces'' R61 (the protein is shown as a ribbon diagram).

Antibiotic drug design

Drug design, often referred to as rational drug design or simply rational design, is the inventive process of finding new medications based on the knowledge of a biological target. The drug is most commonly an organic small molecule that acti ...

is facilitated when an enzyme that is essential to the pathogen's survival is absent or very different in humans. Humans do not make peptidoglycan, therefore antibiotics that inhibit this process are selectively toxic to bacteria. Selective toxicity is also produced in antibiotics by exploiting differences in the structure of the ribosomes in bacteria, or how they make fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, ...

s.

Antivirals

Drugs that inhibit enzymes needed for the replication of viruses are effective in treating viral infections. Antiviral drugs includeprotease inhibitors

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are medications that act by interfering with enzymes that cleave proteins. Some of the most well known are antiviral drugs widely used to treat HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. These protease inhibitors prevent viral replicat ...

used to treat HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ...

and Hepatitis C, reverse-transcriptase inhibitors targeting HIV/AIDS, neuraminidase inhibitors targeting influenza, and terminase inhibitors targeting human cytomegalovirus.

Pesticides

Many pesticides are enzyme inhibitors. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is an enzyme found in animals, from insects to humans. It is essential to nerve cell function through its mechanism of breaking down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into its constituents, acetate andcholine Choline is an essential nutrient for humans and many other animals. Choline occurs as a cation that forms various salts (X− in the depicted formula is an undefined counteranion). Humans are capable of some ''de novo synthesis'' of choline but r ...

. This is somewhat unusual among neurotransmitters as most, including serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline (NA) or noradrenalin, is an organic chemical in the catecholamine family that functions in the brain and body as both a hormone and neurotransmitter. The name "noradrenaline" (from Latin '' ad' ...

, are absorbed from the synaptic cleft

Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow neurons to form circuits within the central nervous syste ...

rather than cleaved. A large number of AChE inhibitors are used in both medicine and agriculture. Reversible competitive inhibitors, such as edrophonium, physostigmine

Physostigmine (also known as eserine from ''éséré'', the West African name for the Calabar bean) is a highly toxic parasympathomimetic alkaloid, specifically, a reversible cholinesterase inhibitor. It occurs naturally in the Calabar bean a ...

, and neostigmine

Neostigmine, sold under the brand name Bloxiverz, among others, is a medication used to treat myasthenia gravis, Ogilvie syndrome, and urinary retention without the presence of a blockage. It is also used in anaesthesia to end the effects of n ...

, are used in the treatment of myasthenia gravis and in anaesthesia to reverse muscle blockade. The carbamate pesticides are also examples of reversible AChE inhibitors. The organophosphate pesticides such as malathion, parathion, and chlorpyrifos

Chlorpyrifos (CPS), also known as Chlorpyrifos ethyl, is an organophosphate pesticide that has been used on crops, animals, and buildings, and in other settings, to kill several pests, including insects and worms. It acts on the nervous systems ...

irreversibly inhibit acetylcholinesterase.

Herbicides

The herbicideglyphosate

Glyphosate (IUPAC name: ''N''-(phosphonomethyl)glycine) is a broad-spectrum systemic herbicide and crop desiccant. It is an organophosphorus compound, specifically a phosphonate, which acts by inhibiting the plant enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshik ...

is an inhibitor of 3-phosphoshikimate 1-carboxyvinyltransferase, other herbicides, such as the sulfonylureas inhibit the enzyme acetolactate synthase

The acetolactate synthase (ALS) enzyme (also known as acetohydroxy acid or acetohydroxyacid synthase, abbr. AHAS) is a protein found in plants and micro-organisms. ALS catalyzes the first step in the synthesis of the branched-chain amino acids ( ...

. Both enzymes are needed for plants to make branched-chain amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

s. Many other enzymes are inhibited by herbicides, including enzymes needed for the biosynthesis of lipids and carotenoids and the processes of photosynthesis and oxidative phosphorylation.

Discovery and design of inhibitors

New drugs are the products of a long drug development process, the first step of which is often the discovery of a new enzyme inhibitor. There are two principle approaches of discovering these inhibitors.

The first general method is rational drug design based on mimicking the

New drugs are the products of a long drug development process, the first step of which is often the discovery of a new enzyme inhibitor. There are two principle approaches of discovering these inhibitors.

The first general method is rational drug design based on mimicking the transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked ...

of the chemical reaction catalysed by the enzyme. The designed inhibitor often closely resembles the substrate, except that the portion of the substrate that undergoes chemical reaction is replaced a chemically stable functional group that resembles the transition state. Since the enzyme has evolved to stabilise the transition state, transition state analogues generally possess higher affinity for the enzyme compared to the substrate, and therefore are effective inhibitors.

The second way of discovering new enzyme inhibitors is high-throughput screening of large libraries of structurally diverse compounds to identify hit molecules that bind to the enzyme. This method has been extended to include virtual screening of databases of diverse molecules using computers, which are then followed by experimental confirmation of binding of the virtual screening hits. Complementary approaches that can provide new starting points for inhibitors include fragment-based lead discovery and screening of DNA-encoded chemical library, DNA-encoded chemical libraries.

Hits from any of the above approaches can be Hit to lead, optimised to high affinity binders that efficiently inhibit the enzyme. Drug design, Computer-based methods for predicting the binding orientation and affinity of an inhibitor for an enzyme such as Docking (molecular), molecular docking and molecular mechanics can be used to assist in the optimisation process. New inhibitors are used to obtain X-ray crystallography#Biological macromolecular crystallography, crystallographic structures of the enzyme in an inhibitor/enzyme complex to show how the molecule is binding to the active site, allowing changes to be made to the inhibitor to optimise binding in a process known as Drug design#Structure-based, structure-based drug design. This test and improve cycle is repeated until a sufficiently potent inhibitor is produced.

See also

* Activity-based proteomics – a branch of proteomics that uses covalent enzyme inhibitors as reporters to monitor enzyme activity. * Antimetabolite – an enzyme inhibitor that is used to interfere with cell growth and division * Transition state analogue – a type of enzyme inhibitor that mimics the transition state of the chemical reaction catalysed by the enzymeReferences

External links

* , Database of enzymes giving lists of known inhibitors for each entry * Database of drugs and enzyme inhibitors * Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry (NC-IUB) on enzyme inhibition terminology {{Enzymes Medicinal chemistry Metabolism Enzyme inhibitors,