An elf () is a type of

humanoid supernatural being in

Germanic mythology and

folklore. Elves appear especially in

North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in

Snorri Sturluson's

Icelandic

Prose Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been ...

. He distinguishes "light elves" and "dark elves". The dark elves create new blond hair for Thor's wife

Sif after

Loki had shorn off Sif's long hair.

In medieval

Germanic-speaking cultures, elves generally seem to have been thought of as beings with magical powers and supernatural beauty, ambivalent towards everyday people and capable of either helping or hindering them. However, the details of these beliefs have varied considerably over time and space and have flourished in both pre-Christian and

Christian cultures.

Sometimes elves are, like dwarfs, associated with craftmanship.

Wayland the Smith embodies this feature. He is known under many names, depending on the language in which the stories were distributed. The names include ''Völund'' in Old Norse, ''Wēland'' in Anglo-Saxon and ''Wieland'' in German. The story of Wayland is also to be found in the ''Prose Edda''.

The word ''elf'' is found throughout the

Germanic languages and seems originally to have meant 'white being'. However, reconstructing the early concept of an elf depends largely on texts written by Christians, in

Old

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

*Old, Northamptonshire, England

* Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, M ...

and

Middle English, medieval German, and

Old Norse. These associate elves variously with the gods of

Norse mythology, with causing illness, with magic, and with beauty and seduction.

After the medieval period, the word ''elf'' tended to become less common throughout the Germanic languages, losing out to alternative native terms like ''

Zwerg

James Zwerg (born November 28, 1939) is an American retired minister who was involved with the Freedom Riders in the early 1960s.

Early life

Zwerg was born in Appleton, Wisconsin where he lived with his parents and older brother, Charles. His ...

'' ('

dwarf

Dwarf or dwarves may refer to:

Common uses

*Dwarf (folklore), a being from Germanic mythology and folklore

* Dwarf, a person or animal with dwarfism

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Dwarf (''Dungeons & Dragons''), a humanoid ...

') in German and ''

huldra'' ('hidden being') in

North Germanic languages, and to loan-words like ''

fairy'' (borrowed from French into most of the Germanic languages). Still, beliefs in elves persisted in the

early modern period, particularly in Scotland and Scandinavia, where elves were thought of as magically powerful people living, usually invisibly, alongside everyday human communities. They continued to be associated with causing illnesses and with sexual threats. For example, several early modern ballads in the

British Isles and Scandinavia, originating in the medieval period, describe elves attempting to seduce or abduct human characters.

With urbanisation and industrialisation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, beliefs in elves declined rapidly (though Iceland has some claim to continued popular belief in elves). However, elves started to be prominent in the literature and art of educated elites from the early modern period onwards. These literary elves were imagined as tiny, playful beings, with

William Shakespeare's ''

A Midsummer Night's Dream'' being a key development of this idea. In the eighteenth century, German

Romantic writers were influenced by this notion of the elf and re-imported the English word ''elf'' into the German language.

From the Romantic idea of elves came the elves of popular culture that emerged in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The "

Christmas elves" of contemporary popular culture are a relatively recent creation, popularized during the late nineteenth century in the United States. Elves entered the twentieth-century

high fantasy genre in the wake of works published by authors such as

J. R. R. Tolkien; these re-popularised the idea of elves as human-sized and humanlike beings. Elves

remain a prominent feature of fantasy media today.

Relationship with reality

Reality and perception

From a scientific viewpoint, elves are not considered

objectively real. However, elves have in many times and places been

believed

''Believed'' is the third and final album by American pop singer-songwriter, actor Jamie Walters with his band, Elco. It was released through indie label Leisure Records.

Track listing

#"Evilyn" (Jamie Walters

James Leland Walters Jr. (born Ju ...

to be real beings. Where enough people have believed in the reality of elves that those beliefs then had real effects in the world, they can be understood as part of people's

worldview, and as a

social reality: a thing which, like the exchange value of a dollar bill or the sense of pride stirred up by a national flag, is real because of people's beliefs rather than as an objective reality. Accordingly, beliefs about elves and their social functions have varied over time and space.

Even in the twenty-first century, fantasy stories about elves have been argued both to reflect and to shape their audiences' understanding of the real world,

and traditions about Santa Claus and his elves relate to

Christmas.

Over time, people have attempted to

demythologise or

rationalise beliefs in elves in various ways.

Integration into Christian cosmologies

Beliefs about elves have their origins before the

conversion to Christianity and associated

Christianization of northwest Europe. For this reason, belief in elves has, from the Middle Ages through into recent scholarship, often been labelled "

pagan" and a "

superstition." However, almost all surviving textual sources about elves were produced by Christians (whether Anglo-Saxon monks, medieval Icelandic poets, early modern ballad-singers, nineteenth-century folklore collectors, or even twentieth-century fantasy authors). Attested beliefs about elves, therefore, need to be understood as part of

Germanic-speakers' Christian culture and not merely a relic of their

pre-Christian religion. Accordingly, investigating the relationship between beliefs in elves and

Christian cosmology

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρισ ...

has been a preoccupation of scholarship about elves both in early times and modern research.

Historically, people have taken three main approaches to integrate elves into Christian cosmology, all of which are found widely across time and space:

* Identifying elves with the

demons of Judaeo-Christian-Mediterranean tradition. For example:

** In English-language material: in the

Royal Prayer Book

The Royal Prayer Book (London, British Library Royal MS 2.A.XX) is a collection of prayers believed to have been copied in the late eighth century or the early ninth century. It was written in West Mercia, likely either in or around Wor ...

from c. 900, ''elf'' appears as a

gloss for "Satan". In the late-fourteenth-century ''

Wife of Bath's Tale'',

Geoffrey Chaucer equates male elves with

incubi

An incubus is a demon in male form in folklore that seeks to have sexual intercourse with sleeping women; the corresponding spirit in female form is called a succubus. In medieval Europe, union with an incubus was supposed by some to result in t ...

(demons which rape sleeping women). In the

early modern Scottish witchcraft trials, witnesses' descriptions of encounters with elves were often interpreted by prosecutors as encounters with the

Devil.

** In medieval Iceland,

Snorri Sturluson wrote in his ''

Prose Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been ...

'' of

''ljósálfar'' and ''dökkálfar'' ('light-elves and dark-elves'), the ''ljósálfar'' living in the heavens and the ''dökkálfar'' under the earth. The consensus of modern scholarship is that Snorri's elves are based on angels and demons of Christian cosmology.

[; ; ; .]

** Elves appear as demonic forces widely in medieval and early modern English, German, and Scandinavian prayers.

[

* Viewing elves as being more or less like people and more or less outside Christian cosmology. The Icelanders who copied the '' Poetic Edda'' did not explicitly try to integrate elves into Christian thought. Likewise, the early modern Scottish people who confessed to encountering elves seem not to have thought of themselves as having dealings with the Devil. Nineteenth-century Icelandic folklore about elves mostly presents them as a human agricultural community parallel to the visible human community, which may or may not be Christian.][ It is possible that stories were sometimes told from this perspective as a political act, to subvert the dominance of the Church.

* Integrating elves into Christian cosmology without identifying them as demons. The most striking examples are serious theological treatises: the Icelandic ''Tíðfordrif'' (1644) by Jón Guðmundsson lærði or, in Scotland, Robert Kirk's ''Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns, and Fairies'' (1691). This approach also appears in the Old English poem '' Beowulf'', which lists elves among the races springing from Cain's murder of Abel. The late thirteenth-century '']South English Legendary

South English legendaries are compilations of versified saints' lives written in southern dialects of Middle English from the late 13th to 15th centuries. At least fifty of these manuscripts survive, preserving nearly three hundred hagiographic wo ...

'' and some Icelandic folktales explain elves as angels that sided neither with Lucifer nor with God and were banished by God to earth rather than hell. One famous Icelandic folktale explains elves as the lost children of Eve.

Demythologising elves as indigenous peoples

Some nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars attempted to rationalise beliefs in elves as folk memories of lost indigenous peoples. Since belief in supernatural beings is ubiquitous in human cultures, scholars no longer believe such explanations are valid. Research has shown, however, that stories about elves have often been used as a way for people to think metaphorically about real-life ethnic others.

Demythologising elves as people with illness or disability

Scholars have at times also tried to explain beliefs in elves as being inspired by people suffering certain kinds of illnesses (such as Williams syndrome). Elves were certainly often seen as a cause of illness, and indeed the English word ''oaf'' seems to have originated as a form of ''elf'': the word ''elf'' came to mean ' changeling left by an elf' and then, because changelings were noted for their failure to thrive, to its modern sense 'a fool, a stupid person; a large, clumsy man or boy'. However, it again seems unlikely that the origin of beliefs in elves itself is to be explained by people's encounters with objectively real people affected by disease.

Etymology

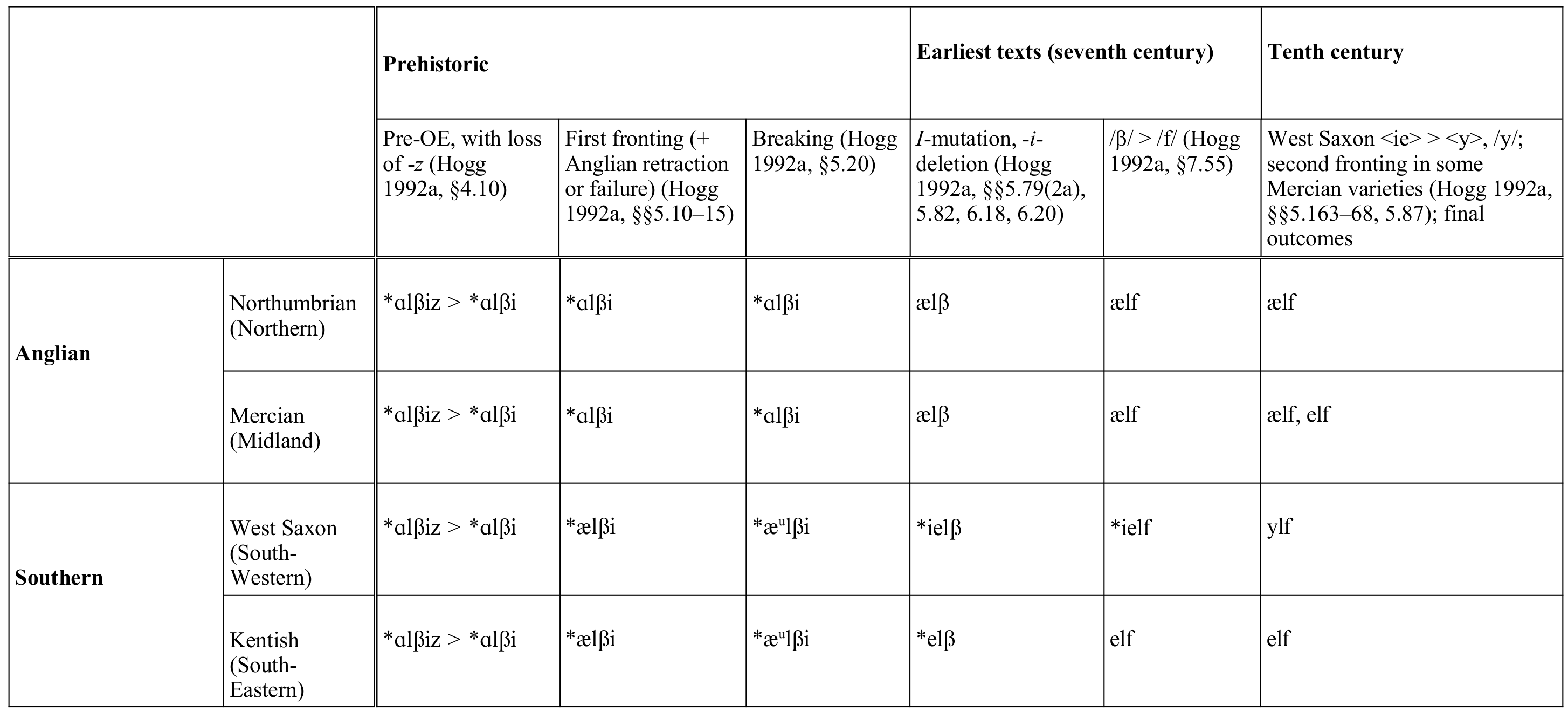

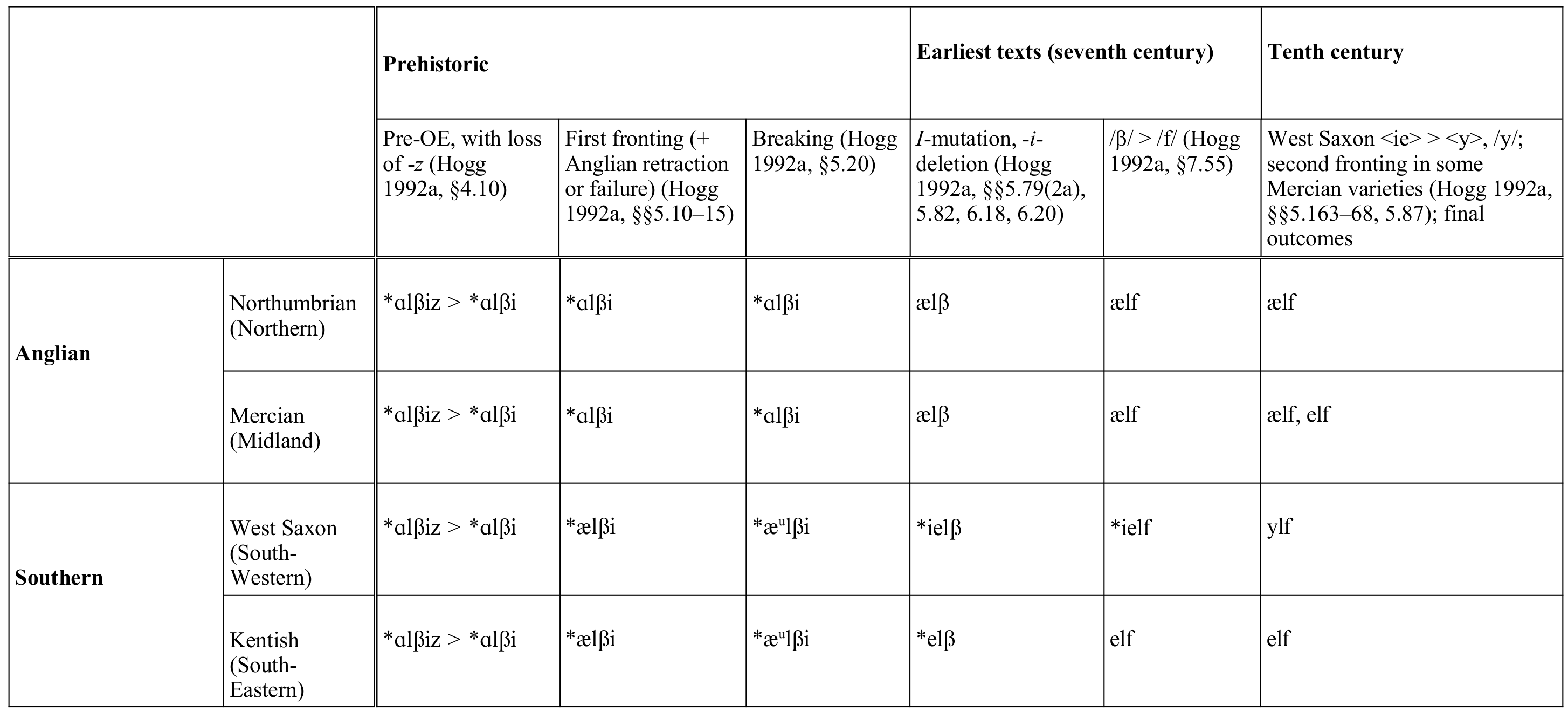

The English word '' elf'' is from the Old English word most often attested as (whose plural would have been *). Although this word took a variety of forms in different Old English dialects, these converged on the form ''elf'' during the Middle English period. During the Old English period, separate forms were used for female elves (such as , putatively from Proto-Germanic *''ɑlβ(i)innjō''), but during the Middle English period the word ''elf'' routinely came to include female beings.

The Old English forms are cognates – linguistic siblings stemming from a common origin – with medieval Germanic terms such as Old Norse ('elf'; plural ), Old High German ('evil spirit'; pl. , ; feminine ), Burgundian *''alfs'' ('elf'), and Middle Low German ' ('evil spirit'). These words must come from Proto-Germanic, the ancestor-language of the attested Germanic languages; the Proto-Germanic forms are reconstructed as *''ɑlβi-z'' and *''ɑlβɑ-z''.

Germanic '' *ɑlβi-z~*ɑlβɑ-z'' is generally agreed to be a cognate with Latin ''albus'' ('(matt) white'), Old Irish ''ailbhín'' ('flock'), Ancient Greek ἀλφός (''alphós''; 'whiteness, white leprosy';), and Albanian ''elb'' ('barley'); and the Germanic word for 'swan' reconstructed as ''*albit-'' (compare Modern Icelandic ''álpt'') is often thought to be derived from it. These all come from an Proto-Indo-European root ''*h₂elbʰ-'', and seem to be connected by the idea of whiteness. The Germanic word presumably originally meant 'white one', perhaps as a euphemism. Jakob Grimm thought whiteness implied positive moral connotations, and, noting Snorri Sturluson's '' ljósálfar'', suggested that elves were divinities of light. This is not necessarily the case, however. For example, because the cognates suggest matt white rather than shining white, and because in medieval Scandinavian texts whiteness is associated with beauty,

The English word '' elf'' is from the Old English word most often attested as (whose plural would have been *). Although this word took a variety of forms in different Old English dialects, these converged on the form ''elf'' during the Middle English period. During the Old English period, separate forms were used for female elves (such as , putatively from Proto-Germanic *''ɑlβ(i)innjō''), but during the Middle English period the word ''elf'' routinely came to include female beings.

The Old English forms are cognates – linguistic siblings stemming from a common origin – with medieval Germanic terms such as Old Norse ('elf'; plural ), Old High German ('evil spirit'; pl. , ; feminine ), Burgundian *''alfs'' ('elf'), and Middle Low German ' ('evil spirit'). These words must come from Proto-Germanic, the ancestor-language of the attested Germanic languages; the Proto-Germanic forms are reconstructed as *''ɑlβi-z'' and *''ɑlβɑ-z''.

Germanic '' *ɑlβi-z~*ɑlβɑ-z'' is generally agreed to be a cognate with Latin ''albus'' ('(matt) white'), Old Irish ''ailbhín'' ('flock'), Ancient Greek ἀλφός (''alphós''; 'whiteness, white leprosy';), and Albanian ''elb'' ('barley'); and the Germanic word for 'swan' reconstructed as ''*albit-'' (compare Modern Icelandic ''álpt'') is often thought to be derived from it. These all come from an Proto-Indo-European root ''*h₂elbʰ-'', and seem to be connected by the idea of whiteness. The Germanic word presumably originally meant 'white one', perhaps as a euphemism. Jakob Grimm thought whiteness implied positive moral connotations, and, noting Snorri Sturluson's '' ljósálfar'', suggested that elves were divinities of light. This is not necessarily the case, however. For example, because the cognates suggest matt white rather than shining white, and because in medieval Scandinavian texts whiteness is associated with beauty, Alaric Hall

Alaric Hall (born 1979) is a British philologist who is an associate professor of English and director of the Institute for Medieval Studies at the University of Leeds. He has, since 2009, been the editor of the academic journal ''Leeds Studies ...

has suggested that elves may have been called 'the white people' because whiteness was associated with (specifically feminine) beauty. Some scholars have argued that the names Albion and Alps may also be related (possibly through Celtic).

A completely different etymology, making ''elf'' a cognate with the '' Ṛbhus'', semi-divine craftsmen in Indian mythology, was suggested by Adalbert Kuhn

Franz Felix Adalbert Kuhn (19 November 1812 – 5 May 1881) was a German philologist and folklorist.

Kuhn was born in Königsberg in Brandenburg's Neumark region. From 1841 he was connected with the Köllnisches Gymnasium at Berlin, of w ...

in 1855.[; .] In this case, *''ɑlβi-z'' would connote the meaning 'skillful, inventive, clever', and could be a cognate with Latin ''labor'', in the sense of 'creative work'. While often mentioned, this etymology is not widely accepted.

In proper names

Throughout the medieval Germanic languages, ''elf'' was one of the nouns used in personal names

A personal name, or full name, in onomastic terminology also known as prosoponym (from Ancient Greek πρόσωπον / ''prósōpon'' - person, and ὄνομα / ''onoma'' - name), is the set of names by which an individual person is know ...

, almost invariably as a first element. These names may have been influenced by Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

names beginning in ''Albio-'' such as '' Albiorix''.

Personal names provide the only evidence for ''elf'' in

Personal names provide the only evidence for ''elf'' in Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

, which must have had the word * (plural *). The most famous name of this kind is ''Alboin

Alboin (530s – 28 June 572) was king of the Lombards from about 560 until 572. During his reign the Lombards ended their migrations by settling in Italy, the northern part of which Alboin conquered between 569 and 572. He had a lasting eff ...

''. Old English names in ''elf''- include the cognate of ''Alboin'' Ælfwine (literally "elf-friend", m.), Ælfric ("elf-powerful", m.), Ælfweard ("elf-guardian", m.), and Ælfwaru ("elf-care", f.). A widespread survivor of these in modern English is Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*'' Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interl ...

(Old English ''Ælfrēd'', "elf-advice"). Also surviving are the English surname Elgar (''Ælfgar'', "elf-spear") and the name of St Alphege (''Ælfhēah'', "elf-tall"). German examples are '' Alberich'', '' Alphart'' and ''Alphere'' (father of Walter of Aquitaine)[ and Icelandic examples include ''Álfhildur''. These names suggest that elves were positively regarded in early Germanic culture. Of the many words for supernatural beings in Germanic languages, the only ones regularly used in personal names are ''elf'' and words denoting pagan gods, suggesting that elves were considered similar to gods.

In later Old Icelandic, ("elf") and the personal name which in Common Germanic had been * both coincidentally became .][

Elves appear in some place names, though it is difficult to be sure how many of other words, including personal names, can appear similar to ''elf''. The clearest English examples are '' Elveden'' ("elves' hill", Suffolk) and '']Elvendon

Elvendon is a small settlement in Oxfordshire and the Chiltern Hills, near Goring-on-Thames, Goring. It includes the grade II listed building Elvendon Priory.

Etymology

The first element of the name is agreed to be the word ''elf'', either in s ...

'' ("elves' valley", Oxfordshire);[Ann Cole, 'Two Chiltern Place-names Reconsidered: Elvendon and Misbourne', ''Journal of the English Place-name Society'', 50 (2018), 65-74 (p. 67).] other examples may be ''Eldon Hill

Eldon Hill is a hill in the Peak District National Park in the county of Derbyshire, England, southwest of the village of Castleton. It is a limestone hill whose pastureland is used for rough grazing, although a large proportion has been ...

'' ("Elves' hill", Derbyshire); and ''Alden Valley

The Alden Valley is a small valley on the eastern edge of the West Pennine Moors, west of Helmshore in Rossendale, Lancashire, England. In the 14th century it was part of the Earl of Lincoln's hunting park. By 1840 it was home to about twenty farm ...

'' ("elves' valley", Lancashire). These seem to associate elves fairly consistently with woods and valleys.

In medieval texts and post-medieval folk belief

Medieval English-language sources

As causes of illnesses

The earliest surviving manuscripts mentioning elves in any Germanic language are from Anglo-Saxon England. Medieval English evidence has, therefore, attracted quite extensive research and debate. In Old English, elves are most often mentioned in medical texts which attest to the belief that elves might afflict humans and livestock with illnesses: apparently mostly sharp, internal pains and mental disorders. The most famous of the medical texts is the metrical charm ''Wið færstice "Wið færstice" is an Old English medical text surviving in the collection known now as ''Lacnunga'' in the British Library. ''Wið fǣrstiċe'' means 'against a sudden/violent stabbing pain'; and according to Felix Grendon, whose collection of A ...

'' ("against a stabbing pain"), from the tenth-century compilation '' Lacnunga'', but most of the attestations are in the tenth-century ''Bald's Leechbook'' and ''Leechbook III''. This tradition continues into later English-language traditions too: elves continue to appear in Middle English medical texts.[; ; .]

Beliefs in elves causing illnesses remained prominent in early modern Scotland, where elves were viewed as supernaturally powerful people who lived invisibly alongside everyday rural people. Thus, elves were often mentioned in the early modern Scottish witchcraft trials: many witnesses in the trials believed themselves to have been given healing powers or to know of people or animals made sick by elves.[ Throughout these sources, elves are sometimes associated with the succubus-like supernatural being called the ''mare''.

While they may have been thought to cause diseases with magical weapons, elves are more clearly associated in Old English with a kind of magic denoted by Old English ''sīden'' and ''sīdsa'', a cognate with the Old Norse '' seiðr'', and also paralleled in the Old Irish '' Serglige Con Culainn''. By the fourteenth century, they were also associated with the arcane practice of alchemy.]

"Elf-shot"

In one or two Old English medical texts, elves might be envisaged as inflicting illnesses with projectiles. In the twentieth century, scholars often labelled the illnesses elves caused as " elf-shot", but work from the 1990s onwards showed that the medieval evidence for elves' being thought to cause illnesses in this way is slender; debate about its significance is ongoing.

The noun ''elf-shot'' is first attested in a Scots poem, "Rowlis Cursing," from around 1500, where "elf schot" is listed among a range of curses to be inflicted on some chicken thieves. The term may not always have denoted an actual projectile: ''shot'' could mean "a sharp pain" as well as "projectile." But in early modern Scotland, ''elf-schot'' and other terms like ''elf-arrowhead'' are sometimes used of neolithic arrow-heads, apparently thought to have been made by elves. In a few witchcraft trials, people attest that these arrow-heads were used in healing rituals and occasionally alleged that witches (and perhaps elves) used them to injure people and cattle. Compare with the following excerpt from a 1749–50 ode by William Collins:

In one or two Old English medical texts, elves might be envisaged as inflicting illnesses with projectiles. In the twentieth century, scholars often labelled the illnesses elves caused as " elf-shot", but work from the 1990s onwards showed that the medieval evidence for elves' being thought to cause illnesses in this way is slender; debate about its significance is ongoing.

The noun ''elf-shot'' is first attested in a Scots poem, "Rowlis Cursing," from around 1500, where "elf schot" is listed among a range of curses to be inflicted on some chicken thieves. The term may not always have denoted an actual projectile: ''shot'' could mean "a sharp pain" as well as "projectile." But in early modern Scotland, ''elf-schot'' and other terms like ''elf-arrowhead'' are sometimes used of neolithic arrow-heads, apparently thought to have been made by elves. In a few witchcraft trials, people attest that these arrow-heads were used in healing rituals and occasionally alleged that witches (and perhaps elves) used them to injure people and cattle. Compare with the following excerpt from a 1749–50 ode by William Collins:[, i 68, stanza II. 1749 date of composition is given on p. 63.]

Size, appearance, and sexuality

Because of elves' association with illness, in the twentieth century, most scholars imagined that elves in the Anglo-Saxon tradition were small, invisible, demonic beings, causing illnesses with arrows. This was encouraged by the idea that "elf-shot" is depicted in the Eadwine Psalter, in an image which became well known in this connection.[ However, this is now thought to be a misunderstanding: the image proves to be a conventional illustration of God's arrows and Christian demons. Rather, twenty-first century scholarship suggests that Anglo-Saxon elves, like elves in Scandinavia or the Irish '' Aos Sí'', were regarded as people.

] Like words for gods and men, the word ''elf'' is used in personal names where words for monsters and demons are not. Just as ''álfar'' is associated with '' Æsir'' in Old Norse, the Old English ''Wið færstice'' associates elves with ''ēse''; whatever this word meant by the tenth century, etymologically it denoted pagan gods. In Old English, the plural (attested in ''Beowulf'') is grammatically an ethnonym (a word for an ethnic group), suggesting that elves were seen as people.

Like words for gods and men, the word ''elf'' is used in personal names where words for monsters and demons are not. Just as ''álfar'' is associated with '' Æsir'' in Old Norse, the Old English ''Wið færstice'' associates elves with ''ēse''; whatever this word meant by the tenth century, etymologically it denoted pagan gods. In Old English, the plural (attested in ''Beowulf'') is grammatically an ethnonym (a word for an ethnic group), suggesting that elves were seen as people.[ As well as appearing in medical texts, the Old English word ''ælf'' and its feminine derivative ''ælbinne'' were used in glosses to translate Latin words for nymphs. This fits well with the word ''ælfscȳne'', which meant "elf-beautiful" and is attested describing the seductively beautiful Biblical heroines Sarah and Judith.

Likewise, in Middle English and early modern Scottish evidence, while still appearing as causes of harm and danger, elves appear clearly as humanlike beings. They became associated with medieval chivalric romance traditions of fairies and particularly with the idea of a Fairy Queen. A propensity to seduce or rape people becomes increasingly prominent in the source material. Around the fifteenth century, evidence starts to appear for the belief that elves might steal human babies and replace them with changelings.

]

Decline in the use of the word ''elf''

By the end of the medieval period, ''elf'' was increasingly being supplanted by the French loan-word ''fairy''. An example is Geoffrey Chaucer's satirical tale '' Sir Thopas'', where the title character sets out in a quest for the "elf-queen", who dwells in the "countree of the Faerie".

Old Norse texts

Mythological texts

Evidence for elf beliefs in medieval Scandinavia outside Iceland is sparse, but the Icelandic evidence is uniquely rich. For a long time, views about elves in Old Norse mythology were defined by Snorri Sturluson's ''

Evidence for elf beliefs in medieval Scandinavia outside Iceland is sparse, but the Icelandic evidence is uniquely rich. For a long time, views about elves in Old Norse mythology were defined by Snorri Sturluson's ''Prose Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been ...

'', which talks about '' svartálfar'', ''dökkálfar'' and ''ljósálfar'' ("black elves", "dark elves", and "light elves"). However, these words are attested only in the Prose Edda and texts based on it. It is now agreed that they reflect traditions of dwarves, demons, and angels, partly showing Snorri's "paganisation" of a Christian cosmology learned from the ''Elucidarius

''Elucidarium'' (also ''Elucidarius'', so called because it "elucidates the obscurity of various things") is an encyclopedic work or ''summa'' about medieval Christian theology and folk belief, originally written in the late 11th century by Hono ...

'', a popular digest of Christian thought.Wið færstice "Wið færstice" is an Old English medical text surviving in the collection known now as ''Lacnunga'' in the British Library. ''Wið fǣrstiċe'' means 'against a sudden/violent stabbing pain'; and according to Felix Grendon, whose collection of A ...

'' and in the Germanic personal name system; moreover, in Skaldic verse the word ''elf'' is used in the same way as words for gods. Sigvatr Þórðarson's skaldic travelogue '' Austrfaravísur'', composed around 1020, mentions an ''álfablót

The Álfablót or the Elven sacrifice is a pagan Scandinavian sacrifice to the elves towards the end of autumn, when the crops had been harvested and the animals were most fat. Unlike the great blóts at Uppsala and Mære, the álfablót was a loca ...

'' ('elves' sacrifice') in Edskogen in what is now southern Sweden. There does not seem to have been any clear-cut distinction between humans and gods; like the Æsir, then, elves were presumably thought of as being humanlike and existing in opposition to the giants. Many commentators have also (or instead) argued for conceptual overlap between elves and dwarves in Old Norse mythology, which may fit with trends in the medieval German evidence.

There are hints that the god Freyr was associated with elves. In particular, '' Álfheimr'' (literally "elf-world") is mentioned as being given to Freyr in '' Grímnismál''. Snorri Sturluson identified Freyr as one of the Vanir. However, the term ''Vanir'' is rare in Eddaic verse, very rare in Skaldic verse, and is not generally thought to appear in other Germanic languages. Given the link between Freyr and the elves, it has therefore long been suspected that ''álfar'' and ''Vanir'' are, more or less, different words for the same group of beings.[ However, this is not uniformly accepted.

A kenning (poetic metaphor) for the sun, '' álfröðull'' (literally "elf disc"), is of uncertain meaning but is to some suggestive of a close link between elves and the sun.][

Although the relevant words are of slightly uncertain meaning, it seems fairly clear that Völundr is described as one of the elves in '' Völundarkviða''. As his most prominent deed in the poem is to rape ]Böðvildr

Böðvildr, Beadohild, Bodil or Badhild was a princess, the daughter of the evil king Níðuðr/Niðhad/Niðung who appears in Germanic legends, such as ''Deor'', ''Völundarkviða'' and '' Þiðrekssaga''. Initially, she appears to have been a t ...

, the poem associates elves with being a sexual threat to maidens. The same idea is present in two post-classical Eddaic poems, which are also influenced by chivalric romance or Breton ''lais'', ''Kötludraumur'' and ''Gullkársljóð

''Gullkársljóð'' ('the poem of Gullkár') is an Old Icelandic Eddaic poem in the ''fornyrðislag'' metre.

Although in Eddaic metre and attested in post-medieval manuscripts of the Poetic Edda, the poem has not been included in the canon of Edd ...

''. The idea also occurs in later traditions in Scandinavia and beyond, so it may be an early attestation of a prominent tradition. Elves also appear in a couple of verse spells, including the Bergen rune-charm from among the Bryggen inscriptions.

Other sources

The appearance of elves in sagas is closely defined by genre. The Sagas of Icelanders

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early el ...

, Bishops' sagas, and contemporary sagas, whose portrayal of the supernatural is generally restrained, rarely mention ''álfar'', and then only in passing. But although limited, these texts provide some of the best evidence for the presence of elves in everyday beliefs in medieval Scandinavia. They include a fleeting mention of elves seen out riding in 1168 (in '' Sturlunga saga''); mention of an ''álfablót'' ("elves' sacrifice") in ''Kormáks saga

''Kormáks saga'' () is one of the Icelanders' sagas. The saga was probably written during the first part of the 13th century.

Though the saga is believed to have been among the earliest sagas composed it is well preserved. The unknown author cle ...

''; and the existence of the euphemism ''ganga álfrek'' ('go to drive away the elves') for "going to the toilet" in '' Eyrbyggja saga''.

The Kings' sagas include a rather elliptical but widely studied account of an early Swedish king being worshipped after his death and being called Ólafr Geirstaðaálfr ('Ólafr the elf of Geirstaðir'), and a demonic elf at the beginning of '' Norna-Gests þáttr''.

The legendary sagas tend to focus on elves as legendary ancestors or on heroes' sexual relations with elf-women. Mention of the land of Álfheimr is found in '' Heimskringla'' while '' Þorsteins saga Víkingssonar'' recounts a line of local kings who ruled over Álfheim, who since they had elven blood were said to be more beautiful than most men.[ According to '' Hrólfs saga kraka'', Hrolfr Kraki's half-sister Skuld was the half-elven child of King Helgi and an elf-woman (''álfkona''). Skuld was skilled in witchcraft (''seiðr''). Accounts of Skuld in earlier sources, however, do not include this material. The '' Þiðreks saga'' version of the Nibelungen (Niflungar) describes Högni as the son of a human queen and an elf, but no such lineage is reported in the Eddas, '' Völsunga saga'', or the '' Nibelungenlied''. The relatively few mentions of elves in the ]chivalric sagas

The ''riddarasögur'' (literally 'sagas of knights', also known in English as 'chivalric sagas', 'romance-sagas', 'knights' sagas', 'sagas of chivalry') are Norse prose Norse saga, sagas of the romance (heroic literature), romance genre. Starting ...

tend even to be whimsical.

In his ''Rerum Danicarum fragmenta'' (1596) written mostly in Latin with some Old Danish and Old Icelandic passages, Arngrímur Jónsson explains the Scandinavian and Icelandic belief in elves (called ''Allffuafolch'').[

Both Continental Scandinavia and Iceland have a scattering of mentions of elves in medical texts, sometimes in Latin and sometimes in the form of amulets, where elves are viewed as a possible cause of illness. Most of them have Low German connections.][

]

Medieval and early modern German texts

The Old High German word ''alp'' is attested only in a small number of glosses. It is defined by the ''Althochdeutsches Wörterbuch'' as a "nature-god or nature-demon, equated with the Fauns of Classical mythology... regarded as eerie, ferocious beings... As the mare he messes around with women". Accordingly, the German word ''Alpdruck'' (literally "elf-oppression") means "nightmare". There is also evidence associating elves with illness, specifically epilepsy.

In a similar vein, elves are in Middle High German most often associated with deceiving or bewildering people in a phrase that occurs so often it would appear to be proverbial: ("the elves/elf are/is deceiving me"). The same pattern holds in Early Modern German. This deception sometimes shows the seductive side apparent in English and Scandinavian material: most famously, the early thirteenth-century Heinrich von Morungen's fifth '' Minnesang'' begins "Von den elben wirt entsehen vil manic man / Sô bin ich von grôzer liebe entsên" ("full many a man is bewitched by elves / thus I too am bewitched by great love"). ''Elbe'' was also used in this period to translate words for nymphs.

In later medieval prayers, Elves appear as a threatening, even demonic, force. For example, some prayers invoke God's help against nocturnal attacks by ''Alpe''. Correspondingly, in the early modern period, elves are described in north Germany doing the evil bidding of witches; Martin Luther believed his mother to have been afflicted in this way.

As in Old Norse, however, there are few characters identified as elves. It seems likely that in the German-speaking world, elves were to a significant extent conflated with dwarves ( gmh, ). Thus, some dwarves that appear in German heroic poetry have been seen as relating to elves. In particular, nineteenth-century scholars tended to think that the dwarf Alberich, whose name etymologically means "elf-powerful," was influenced by early traditions of elves.

The Old High German word ''alp'' is attested only in a small number of glosses. It is defined by the ''Althochdeutsches Wörterbuch'' as a "nature-god or nature-demon, equated with the Fauns of Classical mythology... regarded as eerie, ferocious beings... As the mare he messes around with women". Accordingly, the German word ''Alpdruck'' (literally "elf-oppression") means "nightmare". There is also evidence associating elves with illness, specifically epilepsy.

In a similar vein, elves are in Middle High German most often associated with deceiving or bewildering people in a phrase that occurs so often it would appear to be proverbial: ("the elves/elf are/is deceiving me"). The same pattern holds in Early Modern German. This deception sometimes shows the seductive side apparent in English and Scandinavian material: most famously, the early thirteenth-century Heinrich von Morungen's fifth '' Minnesang'' begins "Von den elben wirt entsehen vil manic man / Sô bin ich von grôzer liebe entsên" ("full many a man is bewitched by elves / thus I too am bewitched by great love"). ''Elbe'' was also used in this period to translate words for nymphs.

In later medieval prayers, Elves appear as a threatening, even demonic, force. For example, some prayers invoke God's help against nocturnal attacks by ''Alpe''. Correspondingly, in the early modern period, elves are described in north Germany doing the evil bidding of witches; Martin Luther believed his mother to have been afflicted in this way.

As in Old Norse, however, there are few characters identified as elves. It seems likely that in the German-speaking world, elves were to a significant extent conflated with dwarves ( gmh, ). Thus, some dwarves that appear in German heroic poetry have been seen as relating to elves. In particular, nineteenth-century scholars tended to think that the dwarf Alberich, whose name etymologically means "elf-powerful," was influenced by early traditions of elves.[

]

Post-medieval folklore

Britain

From around the Late Middle Ages, the word ''elf'' began to be used in English as a term loosely synonymous with the French loan-word ''fairy''; in elite art and literature, at least, it also became associated with diminutive supernatural beings like Puck, hobgoblins, Robin Goodfellow, the English and Scots brownie, and the Northumbrian English hob.

However, in Scotland and parts of northern England near the Scottish border, beliefs in elves remained prominent into the nineteenth century. James VI of Scotland and Robert Kirk discussed elves seriously; elf beliefs are prominently attested in the Scottish witchcraft trials, particularly the trial of Issobel Gowdie; and related stories also appear in folktales, There is a significant corpus of ballads narrating stories about elves, such as ''Thomas the Rhymer'', where a man meets a female elf; '' Tam Lin'', ''

From around the Late Middle Ages, the word ''elf'' began to be used in English as a term loosely synonymous with the French loan-word ''fairy''; in elite art and literature, at least, it also became associated with diminutive supernatural beings like Puck, hobgoblins, Robin Goodfellow, the English and Scots brownie, and the Northumbrian English hob.

However, in Scotland and parts of northern England near the Scottish border, beliefs in elves remained prominent into the nineteenth century. James VI of Scotland and Robert Kirk discussed elves seriously; elf beliefs are prominently attested in the Scottish witchcraft trials, particularly the trial of Issobel Gowdie; and related stories also appear in folktales, There is a significant corpus of ballads narrating stories about elves, such as ''Thomas the Rhymer'', where a man meets a female elf; '' Tam Lin'', ''The Elfin Knight

"The Elfin Knight" () is a traditional Scottish folk ballad of which there are many versions, all dealing with supernatural occurrences, and the commission to perform impossible tasks. The ballad has been collected in different parts of England, S ...

'', and '' Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight'', in which an Elf-Knight rapes, seduces, or abducts a woman; and '' The Queen of Elfland's Nourice'', a woman is abducted to be a wet-nurse to the elf queen's baby, but promised that she might return home once the child is weaned.

Scandinavia

Terminology

In Scandinavian folklore

Nordic folklore is the folklore of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland and the Faroe Islands. It has common roots with, and has been mutually influenced by, folklore in England, Germany, the Low Countries, the Baltic countries, Finland an ...

, many humanlike supernatural beings are attested, which might be thought of as elves and partly originate in medieval Scandinavian beliefs. However, the characteristics and names of these beings have varied widely across time and space, and they cannot be neatly categorised. These beings are sometimes known by words descended directly from the Old Norse ''álfr''. However, in modern languages, traditional terms related to ''álfr'' have tended to be replaced with other terms. Things are further complicated because when referring to the elves of Old Norse mythology, scholars have adopted new forms based directly on the Old Norse word ''álfr''. The following table summarises the situation in the main modern standard languages of Scandinavia.[

]

Appearance and behaviour

The elves of Norse mythology have survived into folklore mainly as females, living in hills and mounds of stones.

The elves of Norse mythology have survived into folklore mainly as females, living in hills and mounds of stones.fairy ring

A fairy ring, also known as fairy circle, elf circle, elf ring or pixie ring, is a naturally occurring ring or arc of mushrooms. They are found mainly in forested areas, but also appear in grasslands or rangelands. Fairy rings are detectable b ...

s consisting of a ring of small mushrooms, but there was also another kind of elf circle. In the words of the local historian Anne Marie Hellström:

In ballads

Elves have a prominent place in several closely related ballads, which must have originated in the Middle Ages but are first attested in the early modern period. Many of these ballads are first attested in Karen Brahes Folio

Karen Brahes Folio (Odense, Landsarkivet for Fyn, Karen Brahe E I,1, also known as Karen Brahes Foliohåndskrift) is a manuscript collection of Danish ballads dating from c. 1583. The manuscript contains the following names, presumed to be of its o ...

, a Danish manuscript from the 1570s, but they circulated widely in Scandinavia and northern Britain. They sometimes mention elves because they were learned by heart, even though that term had become archaic in everyday usage. They have therefore played a major role in transmitting traditional ideas about elves in post-medieval cultures. Indeed, some of the early modern ballads are still quite widely known, whether through school syllabuses or contemporary folk music. They, therefore, give people an unusual degree of access to ideas of elves from older traditional culture.

The ballads are characterised by sexual encounters between everyday people and humanlike beings referred to in at least some variants as elves (the same characters also appear as mermen, dwarves, and other kinds of supernatural beings). The elves pose a threat to the everyday community by lure people into the elves' world. The most famous example is ''Elveskud

"Elveskud" or "Elverskud" (; Danish for "Elf-shot") is the Danish, and most widely used, name for one of the most popular ballads in Scandinavia (''The Types of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballad'' A 63 'Elveskud — Elf maid causes man's sicknes ...

'' and its many variants (paralleled in English as '' Clerk Colvill''), where a woman from the elf world tries to tempt a young knight to join her in dancing, or to live among the elves; in some versions he refuses, and in some he accepts, but in either case he dies, tragically. As in ''Elveskud'', sometimes the everyday person is a man and the elf a woman, as also in '' Elvehøj'' (much the same story as ''Elveskud,'' but with a happy ending), '' Herr Magnus og Bjærgtrolden'', '' Herr Tønne af Alsø'', '' Herr Bøsmer i elvehjem'', or the Northern British ''Thomas the Rhymer

Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, better remembered as Thomas the Rhymer (fl. c. 1220 – 1298), also known as Thomas Learmont or True Thomas, was a Scottish laird and reputed prophet from Earlston (then called "Erceldoune") in the Borders. Thomas ...

''. Sometimes the everyday person is a woman, and the elf is a man, as in the northern British '' Tam Lin'', ''The Elfin Knight

"The Elfin Knight" () is a traditional Scottish folk ballad of which there are many versions, all dealing with supernatural occurrences, and the commission to perform impossible tasks. The ballad has been collected in different parts of England, S ...

'', and '' Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight'', in which the Elf-Knight bears away Isabel to murder her, or the Scandinavian ''Harpans kraft

Harpens kraft (Danish) or Harpans kraft, meaning "The Power of the Harp", is the title of a supernatural ballad type, attested in Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Icelandic variants.

In ''The Types of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballad'' it is catal ...

''. In '' The Queen of Elfland's Nourice'', a woman is abducted to be a wet nurse to the elf-queen's baby, but promised that she might return home once the child is weaned.

As causes of illness

In folk stories, Scandinavian elves often play the role of disease spirits. The most common, though the also most harmless case was various irritating skin rashes, which were called ''älvablåst'' (elven puff) and could be cured by a forceful counter-blow (a handy pair of bellows was most useful for this purpose). ''Skålgropar'', a particular kind of petroglyph (pictogram on a rock) found in Scandinavia, were known in older times as ''älvkvarnar'' (elven mills), because it was believed elves had used them. One could appease the elves by offering a treat (preferably butter) placed into an elven mill.

In folk stories, Scandinavian elves often play the role of disease spirits. The most common, though the also most harmless case was various irritating skin rashes, which were called ''älvablåst'' (elven puff) and could be cured by a forceful counter-blow (a handy pair of bellows was most useful for this purpose). ''Skålgropar'', a particular kind of petroglyph (pictogram on a rock) found in Scandinavia, were known in older times as ''älvkvarnar'' (elven mills), because it was believed elves had used them. One could appease the elves by offering a treat (preferably butter) placed into an elven mill.[

In order to protect themselves and their livestock against malevolent elves, Scandinavians could use a so-called Elf cross (''Alfkors'', ''Älvkors'' or ''Ellakors''), which was carved into buildings or other objects.][The article ]

Alfkors

' in ''Nordisk familjebok'' (1904). It existed in two shapes, one was a pentagram, and it was still frequently used in early 20th-century Sweden as painted or carved onto doors, walls, and household utensils to protect against elves.

Modern continuations

In Iceland, expressing belief in the ''huldufólk'' ("hidden people"), elves that dwell in rock formations, is still relatively common. Even when Icelanders do not explicitly express their belief, they are often reluctant to express disbelief. A 2006 and 2007 study by the University of Iceland's Faculty of Social Sciences revealed that many would not rule out the existence of elves and ghosts, a result similar to a 1974 survey by Erlendur Haraldsson

Erlendur Haraldsson (November 3, 1931 – November 22, 2020) was a professor emeritus of psychology on the faculty of social science at the University of Iceland. He published in various psychology and psychiatry journals. In addition, he publis ...

. The lead researcher of the 2006–2007 study, Terry Gunnell, stated: "Icelanders seem much more open to phenomena like dreaming the future, forebodings, ghosts and elves than other nations". Whether significant numbers of Icelandic people do believe in elves or not, elves are certainly prominent in national discourses. They occur most often in oral narratives and news reporting in which they disrupt house- and road-building. In the analysis of Valdimar Tr. Hafstein, "narratives about the insurrections of elves demonstrate supernatural sanction against development and urbanization; that is to say, the supernaturals protect and enforce religious values and traditional rural culture. The elves fend off, with more or less success, the attacks, and advances of modern technology, palpable in the bulldozer."[ Elves are also prominent, in similar roles, in contemporary Icelandic literature.

Folk stories told in the nineteenth century about elves are still told in modern Denmark and Sweden. Still, they now feature ethnic minorities in place of elves in essentially racist discourse. In an ethnically fairly homogeneous medieval countryside, supernatural beings provided the Other through which everyday people created their identities; in cosmopolitan industrial contexts, ethnic minorities or immigrants are used in storytelling to similar effect.][

]

Post-medieval elite culture

Early modern elite culture

Early modern Europe saw the emergence for the first time of a distinctive elite culture: while the Reformation encouraged new skepticism and opposition to traditional beliefs, subsequent Romanticism encouraged the fetishisation of such beliefs by intellectual elites. The effects of this on writing about elves are most apparent in England and Germany, with developments in each country influencing the other. In Scandinavia, the Romantic movement was also prominent, and literary writing was the main context for continued use of the word ''elf,'' except in fossilised words for illnesses. However, oral traditions about beings like elves remained prominent in Scandinavia into the early twentieth century.

Elves entered early modern elite culture most clearly in the literature of Elizabethan England. Here Edmund Spenser's '' Faerie Queene'' (1590–) used ''fairy'' and ''elf'' interchangeably of human-sized beings, but they are complex, imaginary and allegorical figures. Spenser also presented his own explanation of the origins of the ''Elfe'' and ''Elfin kynd'', claiming that they were created by Prometheus. Likewise, William Shakespeare, in a speech in '' Romeo and Juliet'' (1592) has an "elf-lock" (tangled hair) being caused by

Early modern Europe saw the emergence for the first time of a distinctive elite culture: while the Reformation encouraged new skepticism and opposition to traditional beliefs, subsequent Romanticism encouraged the fetishisation of such beliefs by intellectual elites. The effects of this on writing about elves are most apparent in England and Germany, with developments in each country influencing the other. In Scandinavia, the Romantic movement was also prominent, and literary writing was the main context for continued use of the word ''elf,'' except in fossilised words for illnesses. However, oral traditions about beings like elves remained prominent in Scandinavia into the early twentieth century.

Elves entered early modern elite culture most clearly in the literature of Elizabethan England. Here Edmund Spenser's '' Faerie Queene'' (1590–) used ''fairy'' and ''elf'' interchangeably of human-sized beings, but they are complex, imaginary and allegorical figures. Spenser also presented his own explanation of the origins of the ''Elfe'' and ''Elfin kynd'', claiming that they were created by Prometheus. Likewise, William Shakespeare, in a speech in '' Romeo and Juliet'' (1592) has an "elf-lock" (tangled hair) being caused by Queen Mab

Queen Mab is a fairy referred to in William Shakespeare's play ''Romeo and Juliet'', where "she is the fairies' midwife". Later, she appears in other poetry and literature, and in various guises in drama and cinema. In the play, her activity i ...

, who is referred to as "the fairies' midwife".[; "Rom. & Jul. I, iv, 90 Elf-locks" is the oldest example of the use of the phrase given by the OED.] Meanwhile, '' A Midsummer Night's Dream'' promoted the idea that elves were diminutive and ethereal. The influence of Shakespeare and Michael Drayton made the use of ''elf'' and ''fairy'' for very small beings the norm, and had a lasting effect seen in fairy tales about elves, collected in the modern period.[

]

The Romantic movement

Early modern English notions of elves became influential in eighteenth-century Germany. The Modern German ''Elf'' (m) and ''Elfe'' (f) was introduced as a loan-word from English in the 1740s and was prominent in

Early modern English notions of elves became influential in eighteenth-century Germany. The Modern German ''Elf'' (m) and ''Elfe'' (f) was introduced as a loan-word from English in the 1740s and was prominent in Christoph Martin Wieland

Christoph Martin Wieland (; 5 September 1733 – 20 January 1813) was a German poet and writer. He is best-remembered for having written the first ''Bildungsroman'' (''Geschichte des Agathon''), as well as the epic ''Oberon'', which formed the ba ...

's 1764 translation of ''A Midsummer Night's Dream''.["Die aufnahme des Wortes knüpft an Wielands Übersetzung von Shakespeares Sommernachtstraum 1764 und and Herders Voklslieder 1774 (Werke 25, 42) an"; ]

As German Romanticism got underway and writers started to seek authentic folklore, Jacob Grimm rejected ''Elf'' as a recent Anglicism, and promoted the reuse of the old form ''Elb'' (plural ''Elbe'' or ''Elben''). In the same vein, Johann Gottfried Herder translated the Danish ballad ''Elveskud

"Elveskud" or "Elverskud" (; Danish for "Elf-shot") is the Danish, and most widely used, name for one of the most popular ballads in Scandinavia (''The Types of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballad'' A 63 'Elveskud — Elf maid causes man's sicknes ...

'' in his 1778 collection of folk songs, ', as "" ("The Erl-king's Daughter"; it appears that Herder introduced the term ''Erlkönig'' into German through a mis-Germanisation of the Danish word for ''elf''). This in turn inspired Goethe's poem ''Der Erlkönig

Der or DER may refer to:

Places

* Darkənd, Azerbaijan

* Dearborn (Amtrak station) (station code), in Michigan, US

* Der (Sumer), an ancient city located in modern-day Iraq

* d'Entrecasteaux Ridge, an oceanic ridge in the south-west Pacific Ocean ...

''. Goethe's poem then took on a life of its own, inspiring the Romantic concept of the Erlking

In European folklore and myth, the Erlking is a sinister elf who lingers in the woods. He stalks children who stay in the woods for too long, and kills them by a single touch.

The name "Erlking" (german: Erlkönig, lit=alder-king) is a name u ...

, which was influential on literary images of elves from the nineteenth century on.

In Scandinavia too, in the nineteenth century, traditions of elves were adapted to include small, insect-winged fairies. These are often called "elves" (''älvor'' in modern Swedish, ''alfer'' in Danish, ''álfar'' in Icelandic), although the more formal translation in Danish is ''feer''. Thus, the ''alf'' found in the fairy tale ''The Elf of the Rose'' by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen is so tiny he can have a rose blossom for home, and "wings that reached from his shoulders to his feet". Yet Andersen also wrote about ''elvere'' in ''The Elfin Hill''. The elves in this story are more alike those of traditional Danish folklore, who were beautiful females, living in hills and boulders, capable of dancing a man to death. Like the ''huldra'' in Norway and Sweden, they are hollow when seen from the back.

In Scandinavia too, in the nineteenth century, traditions of elves were adapted to include small, insect-winged fairies. These are often called "elves" (''älvor'' in modern Swedish, ''alfer'' in Danish, ''álfar'' in Icelandic), although the more formal translation in Danish is ''feer''. Thus, the ''alf'' found in the fairy tale ''The Elf of the Rose'' by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen is so tiny he can have a rose blossom for home, and "wings that reached from his shoulders to his feet". Yet Andersen also wrote about ''elvere'' in ''The Elfin Hill''. The elves in this story are more alike those of traditional Danish folklore, who were beautiful females, living in hills and boulders, capable of dancing a man to death. Like the ''huldra'' in Norway and Sweden, they are hollow when seen from the back.[

English and German literary traditions both influenced the British Victorian image of elves, which appeared in illustrations as tiny men and women with pointed ears and stocking caps. An example is Andrew Lang's fairy tale ''Princess Nobody'' (1884), illustrated by Richard Doyle, where fairies are tiny people with butterfly wings. In contrast, elves are small people with red stocking caps. These conceptions remained prominent in twentieth-century children's literature, for example Enid Blyton's ]The Faraway Tree

''The Faraway Tree'' is a series of popular novels for children by British author Enid Blyton. The titles in the series are ''The Enchanted Wood'' (1939), ''The Magic Faraway Tree'' (1943), ''The Folk of the Faraway Tree'' (1946) and ''Up the ...

series, and were influenced by German Romantic literature. Accordingly, in the Brothers Grimm fairy tale '' Die Wichtelmänner'' (literally, "the little men"), the title protagonists are two tiny naked men who help a shoemaker in his work. Even though ''Wichtelmänner'' are akin to beings such as kobold

A kobold (occasionally cobold) is a mythical sprite. Having spread into Europe with various spellings including " goblin" and "hobgoblin", and later taking root and stemming from Germanic mythology, the concept survived into modern times in G ...

s, dwarves and brownies, the tale was translated into English by Margaret Hunt in 1884 as '' The Elves and the Shoemaker''. This shows how the meanings of ''elf'' had changed and was in itself influential: the usage is echoed, for example, in the house-elf of J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter stories. In his turn, J. R. R. Tolkien recommended using the older German form ''Elb'' in translations of his works, as recorded in his ''Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings

Translations of J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'' have been made, with varying degrees of success, into dozens of languages from the original English. Tolkien, an expert in Germanic philology, scrutinized those that were under preparati ...

'' (1967). ''Elb, Elben'' was consequently introduced in 1972 German translation of ''The Lord of the Rings'', repopularising the form in German.

In popular culture

Christmas elf

With industrialisation and mass education, traditional folklore about elves waned, but as the phenomenon of popular culture emerged, elves were re-imagined, in large part based on Romantic literary depictions and associated medievalism.

As American Christmas traditions crystallized in the nineteenth century, the 1823 poem " A Visit from St. Nicholas" (widely known as "'Twas the Night before Christmas") characterized St Nicholas himself as "a right jolly old elf." However, it was his little helpers, inspired partly by folktales like ''The Elves and the Shoemaker'', who became known as "Santa's elves"; the processes through which this came about are not well-understood, but one key figure was a Christmas-related publication by the German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast.

With industrialisation and mass education, traditional folklore about elves waned, but as the phenomenon of popular culture emerged, elves were re-imagined, in large part based on Romantic literary depictions and associated medievalism.

As American Christmas traditions crystallized in the nineteenth century, the 1823 poem " A Visit from St. Nicholas" (widely known as "'Twas the Night before Christmas") characterized St Nicholas himself as "a right jolly old elf." However, it was his little helpers, inspired partly by folktales like ''The Elves and the Shoemaker'', who became known as "Santa's elves"; the processes through which this came about are not well-understood, but one key figure was a Christmas-related publication by the German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast.

Fantasy fiction

The fantasy genre in the twentieth century grew out of nineteenth-century Romanticism, in which nineteenth-century scholars such as Andrew Lang and the Grimm brothers collected fairy stories from folklore and in some cases retold them freely.

A pioneering work of the fantasy genre was ''The King of Elfland's Daughter'', a 1924 novel by Lord Dunsany. The Elf (Middle-earth), Elves of Middle-earth played a central role in Tolkien's legendarium, notably ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''; this legendarium was enormously influential on subsequent fantasy writing. Tolkien's writing had such influence that in the 1960s and afterwards, elves speaking an elvish language similar to those in Tolkien's novels became staple non-human characters in high fantasy works and in fantasy role-playing games. Tolkien also appears to be the first author to have introduced the notion that elves are Immortality, immortal. Post-Tolkien fantasy elves (which feature not only in novels but also in role-playing games such as ''Dungeons & Dragons'') are often portrayed as being wiser and more beautiful than humans, with sharper senses and perceptions as well. They are said to be gifted in magic in fiction, magic, mentally sharp and lovers of nature, art, and song. They are often skilled archers. A hallmark of many fantasy elves is their pointed ears.

In works where elves are the main characters, such as ''The Silmarillion'' or Wendy and Richard Pini's comic book series ''Elfquest'', elves exhibit a similar range of behaviour to a human cast, distinguished largely by their superhuman physical powers. However, where narratives are more human-centered, as in ''The Lord of the Rings'', elves tend to sustain their role as powerful, sometimes threatening, outsiders. Despite the obvious fictionality of fantasy novels and games, scholars have found that elves in these works continue to have a subtle role in shaping the real-life identities of their audiences. For example, elves can function to encode real-world racial others in video games,

The fantasy genre in the twentieth century grew out of nineteenth-century Romanticism, in which nineteenth-century scholars such as Andrew Lang and the Grimm brothers collected fairy stories from folklore and in some cases retold them freely.

A pioneering work of the fantasy genre was ''The King of Elfland's Daughter'', a 1924 novel by Lord Dunsany. The Elf (Middle-earth), Elves of Middle-earth played a central role in Tolkien's legendarium, notably ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''; this legendarium was enormously influential on subsequent fantasy writing. Tolkien's writing had such influence that in the 1960s and afterwards, elves speaking an elvish language similar to those in Tolkien's novels became staple non-human characters in high fantasy works and in fantasy role-playing games. Tolkien also appears to be the first author to have introduced the notion that elves are Immortality, immortal. Post-Tolkien fantasy elves (which feature not only in novels but also in role-playing games such as ''Dungeons & Dragons'') are often portrayed as being wiser and more beautiful than humans, with sharper senses and perceptions as well. They are said to be gifted in magic in fiction, magic, mentally sharp and lovers of nature, art, and song. They are often skilled archers. A hallmark of many fantasy elves is their pointed ears.

In works where elves are the main characters, such as ''The Silmarillion'' or Wendy and Richard Pini's comic book series ''Elfquest'', elves exhibit a similar range of behaviour to a human cast, distinguished largely by their superhuman physical powers. However, where narratives are more human-centered, as in ''The Lord of the Rings'', elves tend to sustain their role as powerful, sometimes threatening, outsiders. Despite the obvious fictionality of fantasy novels and games, scholars have found that elves in these works continue to have a subtle role in shaping the real-life identities of their audiences. For example, elves can function to encode real-world racial others in video games,[ or to influence gender norms through literature.

]

Equivalents in non-Germanic traditions

Beliefs in humanlike supernatural beings are widespread in human cultures, and many such beings may be referred to as ''elves'' in English.

Beliefs in humanlike supernatural beings are widespread in human cultures, and many such beings may be referred to as ''elves'' in English.

Europe

Elfish beings appear to have been a common characteristic within Proto-Indo-European mythology, Indo-European mythologies. In the Celtic-speaking regions of north-west Europe, the beings most similar to elves are generally referred to with the Irish language, Gaelic term '' Aos Sí''. The equivalent term in modern Welsh is ''Tylwyth Teg''. In the Romance languages, Romance-speaking world, beings comparable to elves are widely known by words derived from Latin ''Moirai, fata'' ('fate'), which came into English as ''fairy''. This word became partly synonymous with ''elf'' by the early modern period. Other names also abound, however, such as the Sicilian ''Donas de fuera'' ('ladies from outside'), or French ''bonnes dames'' ('good ladies'). In the Finnic languages, Finnic-speaking world, the term usually thought most closely equivalent to ''elf'' is ''haltija'' (in Finnish) or ''haldaja'' (Estonian). Meanwhile, an example of an equivalent in the Slavic languages, Slavic-speaking world is the ''Supernatural beings in Slavic religion, vila'' (plural ''vile'') of Serbo-Croatian (and, partly, Slovene) Slavic paganism, folklore. Elves bear some resemblances to the satyrs of Greek mythology, who were also regarded as woodland-dwelling mischief-makers.

Asia and Oceania

Some scholarship draws parallels between the Arabian tradition of ''jinn'' with the elves of medieval Germanic-language cultures. Some of the comparisons are quite precise: for example, the root of the word ''jinn'' was used in medieval Arabic terms for madness and possession in similar ways to the Old English word ''ylfig'', which was derived from ''elf'' and also denoted prophetic states of mind implicitly associated with elfish possession.

Khmer culture in Cambodia includes the ''Mrenh kongveal'', elfish beings associated with guarding animals.

In the animistic precolonial beliefs of the Philippines, the world can be divided into the material world and the spirit world. All objects, animate or inanimate, have a spirit called ''anito''. Non-human ''anito'' are known as ''anito#Nature spirits and deities, diwata'', usually euphemistically referred to as ''dili ingon nato'' ('those unlike us'). They inhabit natural features like mountains, forests, old trees, caves, reefs, etc., as well as personify abstract concepts and natural phenomena. They are similar to elves in that they can be helpful or hateful but are usually indifferent to mortals. They can be mischievous and cause unintentional harm to humans, but they can also deliberately cause illnesses and misfortunes when disrespected or angered. Spanish colonizers equated them with elves and fairy folklore.

See also

* Svartálfar

* Dökkálfar and Ljósálfar

Footnotes

Citations

References

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Jacob Grimm, Grimm, Jacob (1835), ''Deutsche Mythologie''.

*

*

*

*

*

*

Eprints.whiterose.ac.uk

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Vol.2

* .

*

*

*

*

*.

* .

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

* Goodrich, Jean N. "Fairy, Elves and the Enchanted Otherworld". In: ''Handbook of Medieval Culture'' Volume 1. Edited by Albrecht Classen. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015. pp. 431-464. https://doi-org.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1515/9783110267303-022

External links

{{Authority control

Elves,

An elf () is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in Snorri Sturluson's Icelandic

An elf () is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in Snorri Sturluson's Icelandic  The English word '' elf'' is from the Old English word most often attested as (whose plural would have been *). Although this word took a variety of forms in different Old English dialects, these converged on the form ''elf'' during the Middle English period. During the Old English period, separate forms were used for female elves (such as , putatively from Proto-Germanic *''ɑlβ(i)innjō''), but during the Middle English period the word ''elf'' routinely came to include female beings.

The Old English forms are cognates – linguistic siblings stemming from a common origin – with medieval Germanic terms such as Old Norse ('elf'; plural ), Old High German ('evil spirit'; pl. , ; feminine ), Burgundian *''alfs'' ('elf'), and Middle Low German ' ('evil spirit'). These words must come from Proto-Germanic, the ancestor-language of the attested Germanic languages; the Proto-Germanic forms are reconstructed as *''ɑlβi-z'' and *''ɑlβɑ-z''.

Germanic '' *ɑlβi-z~*ɑlβɑ-z'' is generally agreed to be a cognate with Latin ''albus'' ('(matt) white'), Old Irish ''ailbhín'' ('flock'), Ancient Greek ἀλφός (''alphós''; 'whiteness, white leprosy';), and Albanian ''elb'' ('barley'); and the Germanic word for 'swan' reconstructed as ''*albit-'' (compare Modern Icelandic ''álpt'') is often thought to be derived from it. These all come from an Proto-Indo-European root ''*h₂elbʰ-'', and seem to be connected by the idea of whiteness. The Germanic word presumably originally meant 'white one', perhaps as a euphemism. Jakob Grimm thought whiteness implied positive moral connotations, and, noting Snorri Sturluson's '' ljósálfar'', suggested that elves were divinities of light. This is not necessarily the case, however. For example, because the cognates suggest matt white rather than shining white, and because in medieval Scandinavian texts whiteness is associated with beauty,

The English word '' elf'' is from the Old English word most often attested as (whose plural would have been *). Although this word took a variety of forms in different Old English dialects, these converged on the form ''elf'' during the Middle English period. During the Old English period, separate forms were used for female elves (such as , putatively from Proto-Germanic *''ɑlβ(i)innjō''), but during the Middle English period the word ''elf'' routinely came to include female beings.

The Old English forms are cognates – linguistic siblings stemming from a common origin – with medieval Germanic terms such as Old Norse ('elf'; plural ), Old High German ('evil spirit'; pl. , ; feminine ), Burgundian *''alfs'' ('elf'), and Middle Low German ' ('evil spirit'). These words must come from Proto-Germanic, the ancestor-language of the attested Germanic languages; the Proto-Germanic forms are reconstructed as *''ɑlβi-z'' and *''ɑlβɑ-z''.

Germanic '' *ɑlβi-z~*ɑlβɑ-z'' is generally agreed to be a cognate with Latin ''albus'' ('(matt) white'), Old Irish ''ailbhín'' ('flock'), Ancient Greek ἀλφός (''alphós''; 'whiteness, white leprosy';), and Albanian ''elb'' ('barley'); and the Germanic word for 'swan' reconstructed as ''*albit-'' (compare Modern Icelandic ''álpt'') is often thought to be derived from it. These all come from an Proto-Indo-European root ''*h₂elbʰ-'', and seem to be connected by the idea of whiteness. The Germanic word presumably originally meant 'white one', perhaps as a euphemism. Jakob Grimm thought whiteness implied positive moral connotations, and, noting Snorri Sturluson's '' ljósálfar'', suggested that elves were divinities of light. This is not necessarily the case, however. For example, because the cognates suggest matt white rather than shining white, and because in medieval Scandinavian texts whiteness is associated with beauty,  Personal names provide the only evidence for ''elf'' in

Personal names provide the only evidence for ''elf'' in  In one or two Old English medical texts, elves might be envisaged as inflicting illnesses with projectiles. In the twentieth century, scholars often labelled the illnesses elves caused as " elf-shot", but work from the 1990s onwards showed that the medieval evidence for elves' being thought to cause illnesses in this way is slender; debate about its significance is ongoing.

The noun ''elf-shot'' is first attested in a Scots poem, "Rowlis Cursing," from around 1500, where "elf schot" is listed among a range of curses to be inflicted on some chicken thieves. The term may not always have denoted an actual projectile: ''shot'' could mean "a sharp pain" as well as "projectile." But in early modern Scotland, ''elf-schot'' and other terms like ''elf-arrowhead'' are sometimes used of neolithic arrow-heads, apparently thought to have been made by elves. In a few witchcraft trials, people attest that these arrow-heads were used in healing rituals and occasionally alleged that witches (and perhaps elves) used them to injure people and cattle. Compare with the following excerpt from a 1749–50 ode by William Collins:, i 68, stanza II. 1749 date of composition is given on p. 63.

In one or two Old English medical texts, elves might be envisaged as inflicting illnesses with projectiles. In the twentieth century, scholars often labelled the illnesses elves caused as " elf-shot", but work from the 1990s onwards showed that the medieval evidence for elves' being thought to cause illnesses in this way is slender; debate about its significance is ongoing.

The noun ''elf-shot'' is first attested in a Scots poem, "Rowlis Cursing," from around 1500, where "elf schot" is listed among a range of curses to be inflicted on some chicken thieves. The term may not always have denoted an actual projectile: ''shot'' could mean "a sharp pain" as well as "projectile." But in early modern Scotland, ''elf-schot'' and other terms like ''elf-arrowhead'' are sometimes used of neolithic arrow-heads, apparently thought to have been made by elves. In a few witchcraft trials, people attest that these arrow-heads were used in healing rituals and occasionally alleged that witches (and perhaps elves) used them to injure people and cattle. Compare with the following excerpt from a 1749–50 ode by William Collins:, i 68, stanza II. 1749 date of composition is given on p. 63.

Like words for gods and men, the word ''elf'' is used in personal names where words for monsters and demons are not. Just as ''álfar'' is associated with '' Æsir'' in Old Norse, the Old English ''Wið færstice'' associates elves with ''ēse''; whatever this word meant by the tenth century, etymologically it denoted pagan gods. In Old English, the plural (attested in ''Beowulf'') is grammatically an ethnonym (a word for an ethnic group), suggesting that elves were seen as people. As well as appearing in medical texts, the Old English word ''ælf'' and its feminine derivative ''ælbinne'' were used in glosses to translate Latin words for nymphs. This fits well with the word ''ælfscȳne'', which meant "elf-beautiful" and is attested describing the seductively beautiful Biblical heroines Sarah and Judith.

Likewise, in Middle English and early modern Scottish evidence, while still appearing as causes of harm and danger, elves appear clearly as humanlike beings. They became associated with medieval chivalric romance traditions of fairies and particularly with the idea of a Fairy Queen. A propensity to seduce or rape people becomes increasingly prominent in the source material. Around the fifteenth century, evidence starts to appear for the belief that elves might steal human babies and replace them with changelings.