electrical telegraphy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point

From early studies of electricity, electrical phenomena were known to travel with great speed, and many experimenters worked on the application of electricity to communications at a distance. All the known effects of electricity—such as sparks,

From early studies of electricity, electrical phenomena were known to travel with great speed, and many experimenters worked on the application of electricity to communications at a distance. All the known effects of electricity—such as sparks,

The first working telegraph was built by the English inventor

The first working telegraph was built by the English inventor  The Schilling telegraph, invented by Baron Schilling von Canstatt in 1832, was an early

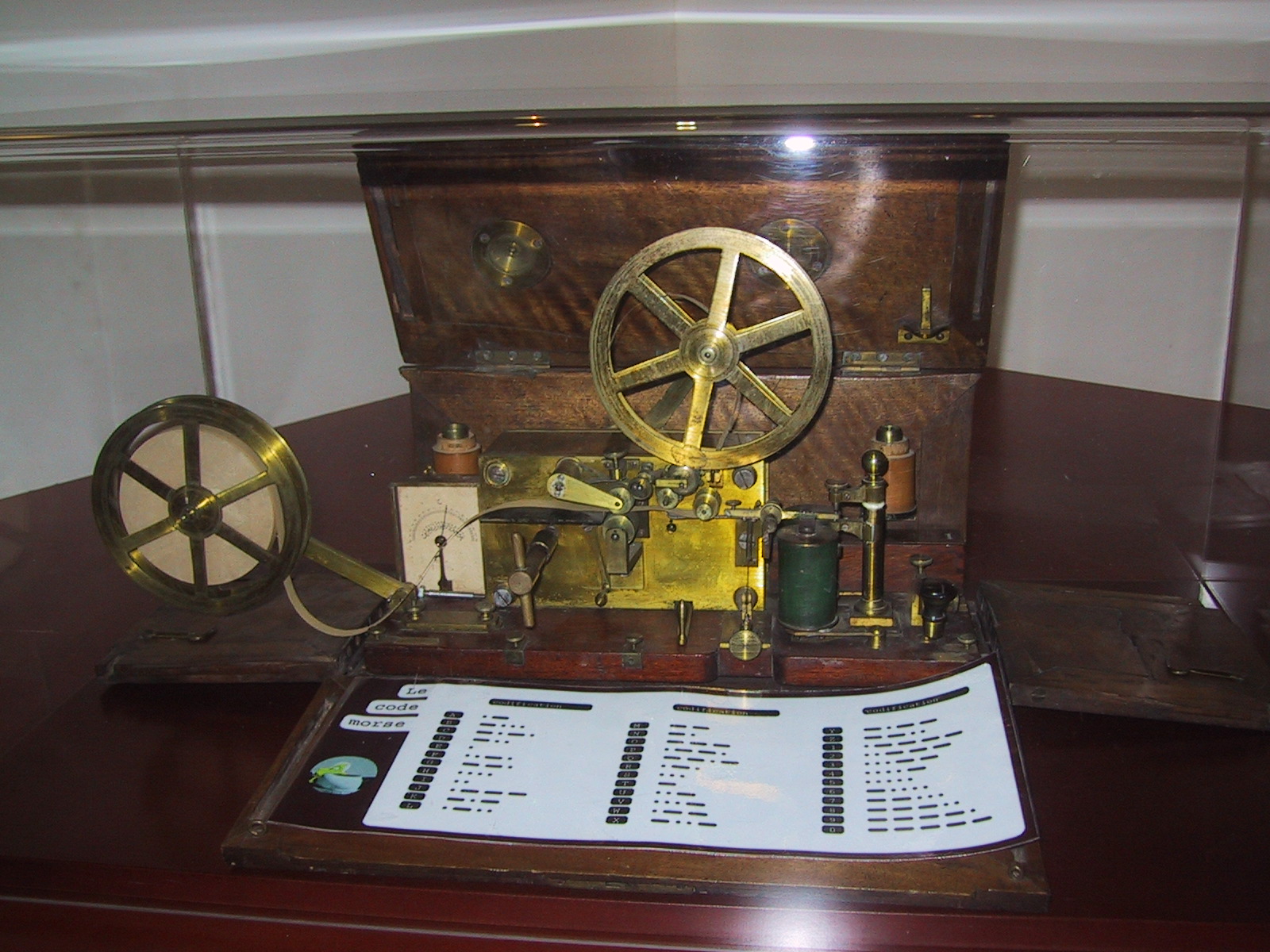

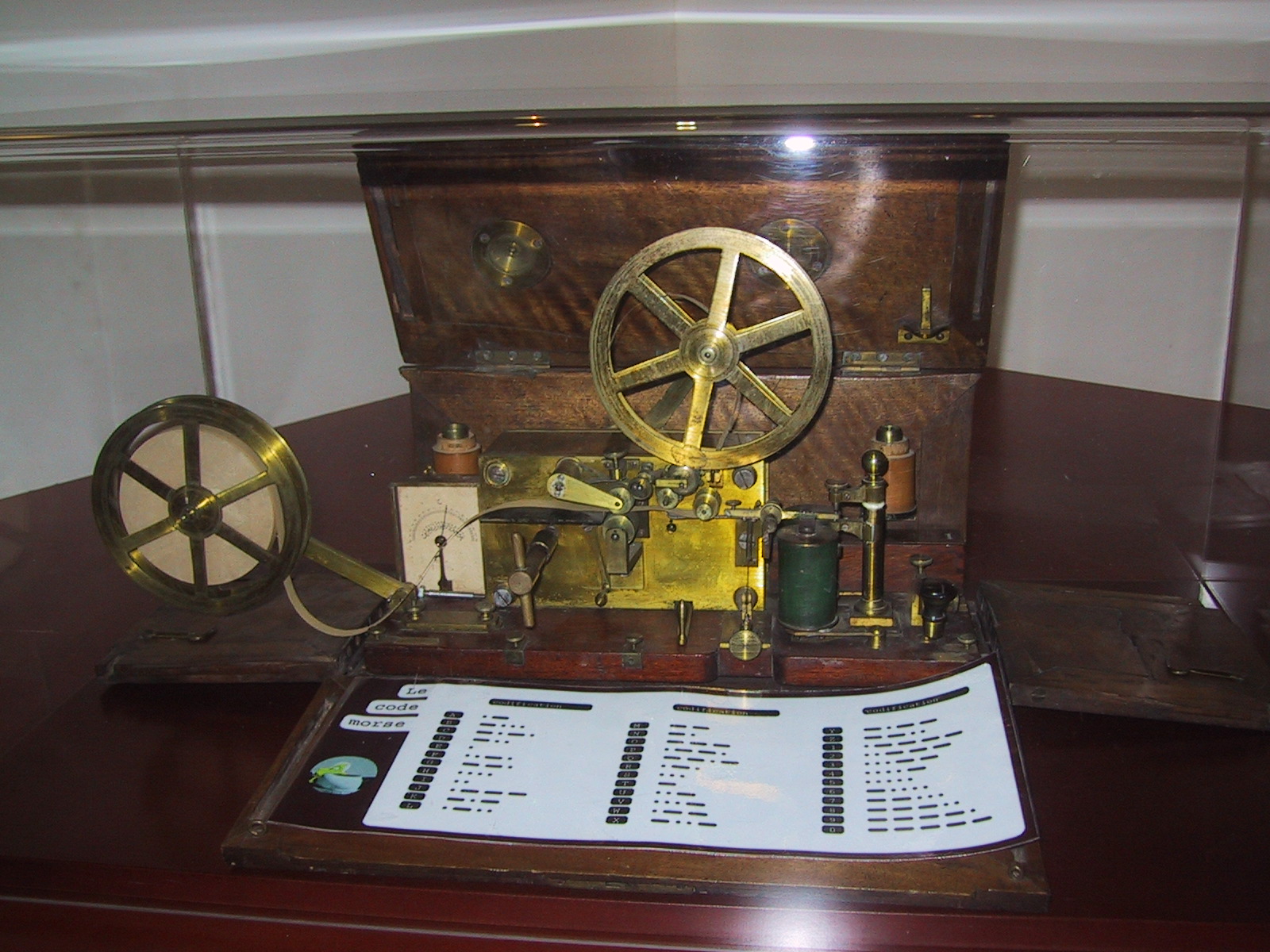

The Schilling telegraph, invented by Baron Schilling von Canstatt in 1832, was an early  At first, Gauss and Weber used the telegraph to coordinate time, but soon they developed other signals and finally, their own alphabet. The alphabet was encoded in a binary code that was transmitted by positive or negative voltage pulses which were generated by means of moving an induction coil up and down over a permanent magnet and connecting the coil with the transmission wires by means of the commutator. The page of Gauss' laboratory notebook containing both his code and the first message transmitted, as well as a replica of the telegraph made in the 1850s under the instructions of Weber are kept in the faculty of physics at the

At first, Gauss and Weber used the telegraph to coordinate time, but soon they developed other signals and finally, their own alphabet. The alphabet was encoded in a binary code that was transmitted by positive or negative voltage pulses which were generated by means of moving an induction coil up and down over a permanent magnet and connecting the coil with the transmission wires by means of the commutator. The page of Gauss' laboratory notebook containing both his code and the first message transmitted, as well as a replica of the telegraph made in the 1850s under the instructions of Weber are kept in the faculty of physics at the

The first commercial electrical telegraph was the Cooke and Wheatstone system. A demonstration four-needle system was installed on the Euston to

The first commercial electrical telegraph was the Cooke and Wheatstone system. A demonstration four-needle system was installed on the Euston to

Wheatstone developed a practical alphabetical system in 1840 called the A.B.C. System, used mostly on private wires. This consisted of a "communicator" at the sending end and an "indicator" at the receiving end. The communicator consisted of a circular dial with a pointer and the 26 letters of the alphabet (and four punctuation marks) around its circumference. Against each letter was a key that could be pressed. A transmission would begin with the pointers on the dials at both ends set to the start position. The transmitting operator would then press down the key corresponding to the letter to be transmitted. In the base of the communicator was a

Wheatstone developed a practical alphabetical system in 1840 called the A.B.C. System, used mostly on private wires. This consisted of a "communicator" at the sending end and an "indicator" at the receiving end. The communicator consisted of a circular dial with a pointer and the 26 letters of the alphabet (and four punctuation marks) around its circumference. Against each letter was a key that could be pressed. A transmission would begin with the pointers on the dials at both ends set to the start position. The transmitting operator would then press down the key corresponding to the letter to be transmitted. In the base of the communicator was a

The Morse system uses a single wire between offices. At the sending station, an operator taps on a switch called a

The Morse system uses a single wire between offices. At the sending station, an operator taps on a switch called a

France was slow to adopt the electrical telegraph, because of the extensive

France was slow to adopt the electrical telegraph, because of the extensive

An early successful

An early successful

Soon after the first successful telegraph systems were operational, the possibility of transmitting messages across the sea by way of

Soon after the first successful telegraph systems were operational, the possibility of transmitting messages across the sea by way of

Cable & Wireless was a British telecommunications company that traced its origins back to the 1860s, with Sir

Cable & Wireless was a British telecommunications company that traced its origins back to the 1860s, with Sir

World War II revived the 'cable war' of 1914–1918. In 1939, German-owned cables across the Atlantic were cut once again, and, in 1940, Italian cables to South America and Spain were cut in retaliation for Italian action against two of the five British cables linking Gibraltar and Malta.

World War II revived the 'cable war' of 1914–1918. In 1939, German-owned cables across the Atlantic were cut once again, and, in 1940, Italian cables to South America and Spain were cut in retaliation for Italian action against two of the five British cables linking Gibraltar and Malta.

Roots of Interconnection: Communications, Transportation and Phases of the Industrial Revolution

International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering Background Reading, Version 1; February 2008. * Steinheil, C.A., ''Ueber Telegraphie'', München 1838. * Yates, JoAnne

The Telegraph's Effect on Nineteenth Century Markets and Firms

Morse Telegraph Club, Inc.

(The Morse Telegraph Club is an international non-profit organization dedicated to the perpetuation of the knowledge and traditions of telegraphy.) * https://web.archive.org/web/20050829153213/http://collections.ic.gc.ca/canso/index.htm

Shilling's telegraph

an exhibit of the A.S. Popov Central Museum of Communications

History of electromagnetic telegraph

article in ''PCWeek'', Russian edition.

Distant Writing

– The History of the Telegraph Companies in Britain between 1838 and 1868

NASA 6 May 2008

How Cables Unite The World

– a 1902 article about telegraph networks and technology from the magazine '' The World's Work'' *

Indiana telegraph and telephone collection

Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library *

Wonders of electricity and the elements, being a popular account of modern electrical and magnetic discoveries, magnetism and electric machines, the electric telegraph and the electric light, and the metal bases, salt, and acids

' fro

Science History Institute Digital Collections

*

The electro magnetic telegraph: with an historical account of its rise, progress, and present condition

' fro

Science History Institute Digital Collections

{{Authority control Telegraphy Russian inventions 19th-century inventions

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging

Text messaging, or texting, is the act of composing and sending electronic messages, typically consisting of alphabetic and numeric characters, between two or more users of mobile devices, desktops/laptops, or another type of compatible comput ...

systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications

Telecommunication is the transmission of information by various types of technologies over wire, radio, optical, or other electromagnetic systems. It has its origin in the desire of humans for communication over a distance greater than that fe ...

system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems called ''telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

s'', that were devised to communicate text messages quicker than physical transportation. Electrical telegraphy can be considered to be the first example of electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

.

Text telegraphy consisted of two or more geographically separated stations, called telegraph office

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

s. The offices were connected by wires, usually supported overhead on utility pole

A utility pole is a column or post typically made out of wood used to support overhead power lines and various other public utilities, such as electrical cable, optical fiber, fiber optic cable, and related equipment such as Distribution transfor ...

s. Many different electrical telegraph systems were invented, but the ones that became widespread fit into two broad categories. The first category consists of needle telegraphs in which a needle pointer is made to move electromagnetically with an electric current

An electric current is a stream of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is measured as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface or into a control volume. The moving pa ...

sent down the telegraph line. Early systems used multiple needles requiring multiple wires. The first commercial system, and the most widely used needle telegraph, was the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph

The Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph was an early electrical telegraph system dating from the 1830s invented by English inventor William Fothergill Cooke and English scientist Charles Wheatstone. It was a form of needle telegraph, and the first t ...

, invented in 1837. The second category consists of armature systems in which the current activates a telegraph sounder

A telegraph sounder is an antique electromechanical device used as a receiver on electrical telegraph lines during the 19th century. It was invented by Alfred Vail after 1850 to replace the previous receiving device, the cumbersome Morse regist ...

which makes a click. The archetype of this category was the Morse system, invented by Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

in 1838. In 1865, the Morse system became the standard for international communication using a modified code developed for German railways.

Electrical telegraphs were used by the emerging railway companies to develop train control systems, minimizing the chances of trains colliding with each other. This was built around the signalling block system

Signalling block systems enable the safe and efficient operation of railways by preventing collisions between trains. The basic principle is that a track is broken up into a series of sections or "blocks". Only one train may occupy a block at a ...

with signal boxes along the line communicating with their neighbouring boxes by telegraphic sounding of single-stroke bells and three-position needle telegraph

A needle telegraph is an electrical telegraph that uses indicating needles moved electromagnetically as its means of displaying messages. It is one of the two main types of electromagnetic telegraph, the other being the armature system, as exem ...

instruments.

In the 1840s, the electrical telegraph superseded optical telegraph

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and ...

systems, becoming the standard way to send urgent messages. By the latter half of the century, most developed nations

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

had created commercial telegraph networks with local telegraph offices in most cities and towns, allowing the public to send messages called telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

s addressed to any person in the country, for a fee.

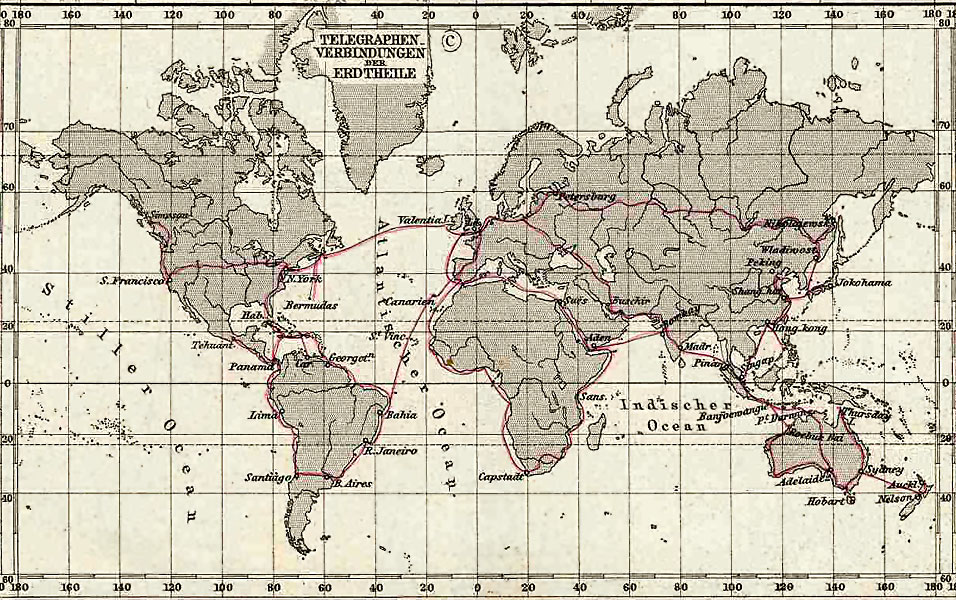

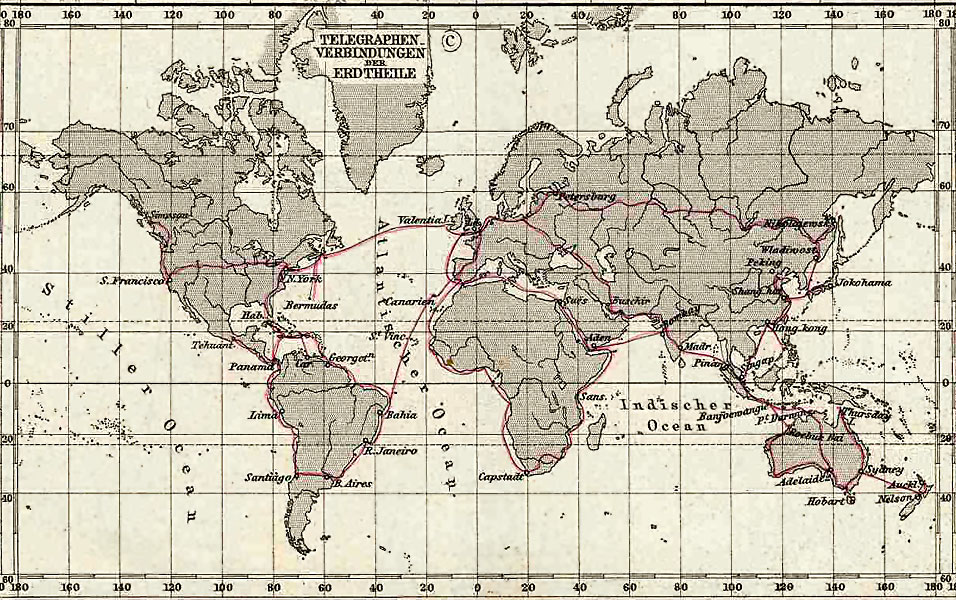

Beginning in 1850, submarine telegraph cables allowed for the first rapid communication between continents. Electrical telegraph networks permitted people and commerce to transmit messages across both continents and oceans almost instantly, with widespread social and economic impacts. Circa 1894, the electric telegraph led to Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italian inventor and electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based wireless telegraph system. This led to Marconi bei ...

's invention of wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for t ...

, the first means of radiowave

Radio waves are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies of 300 gigahertz (GHz) and below. At 300 GHz, the corresponding wavelength is 1 mm (short ...

telecommunication.

In the early 20th century, manual telegraphy was slowly replaced by teleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initi ...

networks. Increasing use of the telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into el ...

pushed telegraphy into a few specialist uses. Use by the general public was mainly special occasion telegram greetings. The rise of the internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

and usage of email

Electronic mail (email or e-mail) is a method of exchanging messages ("mail") between people using electronic devices. Email was thus conceived as the electronic (digital) version of, or counterpart to, mail, at a time when "mail" meant ...

in the 1990s largely put an end to dedicated telegraphy networks.

History

Precursors

Prior to the electric telegraph,semaphore

Semaphore (; ) is the use of an apparatus to create a visual signal transmitted over distance. A semaphore can be performed with devices including: fire, lights, flags, sunlight, and moving arms. Semaphores can be used for telegraphy when arra ...

systems were used, including beacons

A beacon is an intentionally conspicuous device designed to attract attention to a specific location. A common example is the lighthouse, which draws attention to a fixed point that can be used to navigate around obstacles or into port. More mode ...

, smoke signal

The smoke signal is one of the oldest forms of long-distance communication. It is a form of visual communication used over a long distance. In general smoke signals are used to transmit news, signal danger, or to gather people to a common area ...

s, flag semaphore

Flag semaphore (from the Ancient Greek () 'sign' and - (-) '-bearer') is a semaphore system conveying information at a distance by means of visual signals with hand-held flags, rods, disks, paddles, or occasionally bare or gloved hands. Inform ...

, and optical telegraph

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and ...

s for visual signals to communicate over distances of land.

An auditory predecessor was West African talking drums. In the 19th century, Yoruba drummers used talking drums to mimic human tonal language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

to communicate complex messages - usually regarding news of birth, ceremonies, and military conflict - over 4-5 mile distances.

Early work

From early studies of electricity, electrical phenomena were known to travel with great speed, and many experimenters worked on the application of electricity to communications at a distance. All the known effects of electricity—such as sparks,

From early studies of electricity, electrical phenomena were known to travel with great speed, and many experimenters worked on the application of electricity to communications at a distance. All the known effects of electricity—such as sparks, electrostatic attraction

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that quantifies the amount of force between two stationary, electrically charged particles. The electric force between charged bodies at rest is conventio ...

, chemical change

Chemical changes occur when a substance combines with another to form a new substance, called chemical synthesis or, alternatively, chemical decomposition into two or more different substances. These processes are called chemical reactions and, ...

s, electric shocks, and later electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of ...

—were applied to the problems of detecting controlled transmissions of electricity at various distances.

In 1753, an anonymous writer in the ''Scots Magazine

''The Scots Magazine'' is a magazine containing articles on subjects of Scottish interest. It claims to be the oldest magazine in the world still in publication, although there have been several gaps in its publication history. It has reported on ...

'' suggested an electrostatic telegraph. Using one wire for each letter of the alphabet, a message could be transmitted by connecting the wire terminals in turn to an electrostatic machine, and observing the deflection of pith

Pith, or medulla, is a tissue in the stems of vascular plants. Pith is composed of soft, spongy parenchyma cells, which in some cases can store starch. In eudicotyledons, pith is located in the center of the stem. In monocotyledons, it ext ...

balls at the far end. The writer has never been positively identified, but the letter was signed C.M. and posted from Renfrew

Renfrew (; sco, Renfrew; gd, Rinn Friù) is a town west of Glasgow in the west central Lowlands of Scotland. It is the historic county town of Renfrewshire (historic), Renfrewshire. Called the "Cradle of the House of Stewart, Royal Stewarts" ...

leading to a Charles Marshall of Renfrew being suggested. Telegraphs employing electrostatic attraction were the basis of early experiments in electrical telegraphy in Europe, but were abandoned as being impractical and were never developed into a useful communication system.

In 1774, Georges-Louis Le Sage

Georges-Louis Le Sage (; 13 June 1724 – 9 November 1803) was a Genevan physicist and is most known for his theory of gravitation, for his invention of an electric telegraph and his anticipation of the kinetic theory of gases. Furthermore, he ...

realised an early electric telegraph. The telegraph had a separate wire for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letter (alphabet), letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character ...

and its range was only between two rooms of his home.

In 1800, Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (, ; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian physicist, chemist and lay Catholic who was a pioneer of electricity and power who is credited as the inventor of the electric battery and the ...

invented the voltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. The copper and zinc discs were separated by cardboard or felt spacers soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the bottom, ...

, providing a continuous current of electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

for experimentation. This became a source of a low-voltage current that could be used to produce more distinct effects, and which was far less limited than the momentary discharge of an electrostatic machine

An electrostatic generator, or electrostatic machine, is an electrical generator that produces ''static electricity'', or electricity at high voltage and low continuous current. The knowledge of static electricity dates back to the earliest civi ...

, which with Leyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, sometimes Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It typi ...

s were the only previously known man-made sources of electricity.

Another very early experiment in electrical telegraphy was an "electrochemical telegraph" created by the German physician, anatomist and inventor Samuel Thomas von Sömmering

Samuel ''Šəmūʾēl'', Tiberian: ''Šămūʾēl''; ar, شموئيل or صموئيل '; el, Σαμουήλ ''Samouḗl''; la, Samūēl is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the bib ...

in 1809, based on an earlier, less robust design of 1804 by Spanish polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

and scientist Francisco Salva Campillo

Francisco Salva Campillo ( Catalan: Francesc Salvà i Campillo, July 12, 1751 – February 13, 1828) was a Spanish Catalan prominent late-Enlightenment period scientist known for working as a physician, physicist, meteorologist.

Early life and ...

. Both their designs employed multiple wires (up to 35) to represent almost all Latin letters and numerals. Thus, messages could be conveyed electrically up to a few kilometers (in von Sömmering's design), with each of the telegraph receiver's wires immersed in a separate glass tube of acid. An electric current was sequentially applied by the sender through the various wires representing each letter of a message; at the recipient's end, the currents electrolysed the acid in the tubes in sequence, releasing streams of hydrogen bubbles next to each associated letter or numeral. The telegraph receiver's operator would watch the bubbles and could then record the transmitted message. This is in contrast to later telegraphs that used a single wire (with ground return).

Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted ( , ; often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 17779 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricity ...

discovered in 1820 that an electric current produces a magnetic field that will deflect a compass needle. In the same year Johann Schweigger invented the galvanometer

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely.

A galvano ...

, with a coil of wire around a compass, that could be used as a sensitive indicator for an electric current. Also that year, André-Marie Ampère

André-Marie Ampère (, ; ; 20 January 177510 June 1836) was a French physicist and mathematician who was one of the founders of the science of classical electromagnetism, which he referred to as "electrodynamics". He is also the inventor of nu ...

suggested that telegraphy could be achieved by placing small magnets under the ends of a set of wires, one pair of wires for each letter of the alphabet. He was apparently unaware of Schweigger's invention at the time, which would have made his system much more sensitive. In 1825, Peter Barlow tried Ampère's idea but only got it to work over and declared it impractical. In 1830 William Ritchie improved on Ampère's design by placing the magnetic needles inside a coil of wire connected to each pair of conductors. He successfully demonstrated it, showing the feasibility of the electromagnetic telegraph, but only within a lecture hall.

In 1825, William Sturgeon

William Sturgeon (22 May 1783 – 4 December 1850) was an English physicist and inventor who made the first electromagnets, and invented the first practical British electric motor.

Early life

Sturgeon was born on 22 May 1783 in Whittington, ...

invented the electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in the ...

, with a single winding of uninsulated wire on a piece of varnished iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in fr ...

, which increased the magnetic force produced by electric current. Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smith ...

improved it in 1828 by placing several windings of insulated wire around the bar, creating a much more powerful electromagnet which could operate a telegraph through the high resistance of long telegraph wires. During his tenure at The Albany Academy

The Albany Academy is an independent college preparatory day school for boys in Albany, New York, USA, enrolling students from Preschool (age 3) to Grade 12. It was established in 1813 by a charter signed by Mayor Philip Schuyler Van Renssela ...

from 1826 to 1832, Henry first demonstrated the theory of the 'magnetic telegraph' by ringing a bell through of wire strung around the room in 1831.

In 1835, Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smith ...

and Edward Davy independently invented the mercury dipping electrical relay, in which a magnetic needle is dipped into a pot of mercury when an electric current passes through the surrounding coil. In 1837, Davy invented the much more practical metallic make-and-break relay which became the relay of choice in telegraph systems and a key component for periodically renewing weak signals. Davy demonstrated his telegraph system in Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies of high ground in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the Borough of Camden (and historically betwe ...

in 1837 and was granted a patent on 4 July 1838. Davy also invented a printing telegraph which used the electric current from the telegraph signal to mark a ribbon of calico infused with potassium iodide

Potassium iodide is a chemical compound, medication, and dietary supplement. It is a medication used for treating hyperthyroidism, in radiation emergencies, and for protecting the thyroid gland when certain types of radiopharmaceuticals are us ...

and calcium hypochlorite.

First working systems

The first working telegraph was built by the English inventor

The first working telegraph was built by the English inventor Francis Ronalds

Sir Francis Ronalds FRS (21 February 17888 August 1873) was an English scientist and inventor, and arguably the first electrical engineer. He was knighted for creating the first working electric telegraph over a substantial distance. In 1816 h ...

in 1816 and used static electricity. At the family home on Hammersmith Mall, he set up a complete subterranean system in a long trench as well as an long overhead telegraph. The lines were connected at both ends to revolving dials marked with the letters of the alphabet and electrical impulses sent along the wire were used to transmit messages. Offering his invention to the Admiralty in July 1816, it was rejected as "wholly unnecessary". His account of the scheme and the possibilities of rapid global communication in ''Descriptions of an Electrical Telegraph and of some other Electrical Apparatus'' was the first published work on electric telegraphy and even described the risk of signal retardation due to induction. Elements of Ronalds' design were utilised in the subsequent commercialisation of the telegraph over 20 years later.

The Schilling telegraph, invented by Baron Schilling von Canstatt in 1832, was an early

The Schilling telegraph, invented by Baron Schilling von Canstatt in 1832, was an early needle telegraph

A needle telegraph is an electrical telegraph that uses indicating needles moved electromagnetically as its means of displaying messages. It is one of the two main types of electromagnetic telegraph, the other being the armature system, as exem ...

. It had a transmitting device that consisted of a keyboard with 16 black-and-white keys. These served for switching the electric current. The receiving instrument consisted of six galvanometer

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely.

A galvano ...

s with magnetic needles, suspended from silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the co ...

threads. The two stations of Schilling's telegraph were connected by eight wires; six were connected with the galvanometers, one served for the return current and one for a signal bell. When at the starting station the operator pressed a key, the corresponding pointer was deflected at the receiving station. Different positions of black and white flags on different disks gave combinations which corresponded to the letters or numbers. Pavel Schilling subsequently improved its apparatus by reducing the number of connecting wires from eight to two.

On 21 October 1832, Schilling managed a short-distance transmission of signals between two telegraphs in different rooms of his apartment. In 1836, the British government attempted to buy the design but Schilling instead accepted overtures from Nicholas I of Russia. Schilling's telegraph was tested on a experimental underground and underwater cable, laid around the building of the main Admiralty in Saint Petersburg and was approved for a telegraph between the imperial palace at Peterhof and the naval base at Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for "crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

. However, the project was cancelled following Schilling's death in 1837. Schilling was also one of the first to put into practice the idea of the binary

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two digits (0 and 1)

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical operation that ta ...

system of signal transmission. His work was taken over and developed by Moritz von Jacobi

Moritz Hermann or Boris Semyonovich (von) Jacobi (russian: Борис Семёнович Якоби; 21 September 1801, Potsdam – 10 March 1874, Saint Petersburg) was a Prussian and Russian Imperial engineer and physicist of Jewish descent. Ja ...

who invented telegraph equipment that was used by Tsar Alexander III to connect the Imperial palace at Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the cen ...

and Kronstadt Naval Base.

In 1833, Carl Friedrich Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gauß ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refer ...

, together with the physics professor Wilhelm Weber in Göttingen

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The or ...

installed a wire above the town's roofs. Gauss combined the Poggendorff-Schweigger multiplicator with his magnetometer to build a more sensitive device, the galvanometer

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely.

A galvano ...

. To change the direction of the electric current, he constructed a commutator

In mathematics, the commutator gives an indication of the extent to which a certain binary operation fails to be commutative. There are different definitions used in group theory and ring theory.

Group theory

The commutator of two elements, ...

of his own. As a result, he was able to make the distant needle move in the direction set by the commutator on the other end of the line.

At first, Gauss and Weber used the telegraph to coordinate time, but soon they developed other signals and finally, their own alphabet. The alphabet was encoded in a binary code that was transmitted by positive or negative voltage pulses which were generated by means of moving an induction coil up and down over a permanent magnet and connecting the coil with the transmission wires by means of the commutator. The page of Gauss' laboratory notebook containing both his code and the first message transmitted, as well as a replica of the telegraph made in the 1850s under the instructions of Weber are kept in the faculty of physics at the

At first, Gauss and Weber used the telegraph to coordinate time, but soon they developed other signals and finally, their own alphabet. The alphabet was encoded in a binary code that was transmitted by positive or negative voltage pulses which were generated by means of moving an induction coil up and down over a permanent magnet and connecting the coil with the transmission wires by means of the commutator. The page of Gauss' laboratory notebook containing both his code and the first message transmitted, as well as a replica of the telegraph made in the 1850s under the instructions of Weber are kept in the faculty of physics at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded i ...

, in Germany.

Gauss was convinced that this communication would be a help to his kingdom's towns. Later in the same year, instead of a Voltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. The copper and zinc discs were separated by cardboard or felt spacers soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the bottom, ...

, Gauss used an induction pulse, enabling him to transmit seven letters a minute instead of two. The inventors and university did not have the funds to develop the telegraph on their own, but they received funding from Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

. Carl August Steinheil in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

was able to build a telegraph network within the city in 1835–1836. He installed a telegraph line along the first German railroad in 1835. Steinheil built a telegraph along the Nuremberg - Fürth railway line in 1838, the first earth-return telegraph

Earth-return telegraph is the system whereby the return path for the electric current of a telegraph circuit is provided by connection to the earth through an earth electrode. Using earth return saves a great deal of money on installation co ...

put into service.

By 1837, William Fothergill Cooke

Sir William Fothergill Cooke (4 May 1806 – 25 June 1879) was an English inventor. He was, with Charles Wheatstone, the co-inventor of the Cooke-Wheatstone electrical telegraph, which was patented in May 1837. Together with John Ricardo he fo ...

and Charles Wheatstone

Sir Charles Wheatstone FRS FRSE DCL LLD (6 February 1802 – 19 October 1875), was an English scientist and inventor of many scientific breakthroughs of the Victorian era, including the English concertina, the stereoscope (a device for dis ...

had co-developed a telegraph system which used a number of needles on a board that could be moved to point to letters of the alphabet. Any number of needles could be used, depending on the number of characters it was required to code. In May 1837 they patented their system. The patent recommended five needles, which coded twenty of the alphabet's 26 letters.

Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

independently developed and patented a recording electric telegraph in 1837. Morse's assistant Alfred Vail

Alfred Lewis Vail (September 25, 1807 – January 18, 1859) was an American machinist and inventor. Along with Samuel Morse, Vail was central in developing and commercializing American telegraphy between 1837 and 1844.

Vail and Morse were the f ...

developed an instrument that was called the register for recording the received messages. It embossed dots and dashes on a moving paper tape by a stylus which was operated by an electromagnet. Morse and Vail developed the Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

signalling alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letter (alphabet), letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character ...

. The first telegram in the United States was sent by Morse on 11 January 1838, across of wire at Speedwell Ironworks

Speedwell Ironworks was an ironworks in Speedwell Village, on Speedwell Avenue (part of U.S. Route 202), just north of downtown Morristown, in Morris County, New Jersey, United States. At this site Alfred Vail and Samuel Morse first demonstrated ...

near Morristown, New Jersey, although it was only later, in 1844, that he sent the message " WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT" over the from the Capitol

A capitol, named after the Capitoline Hill in Rome, is usually a legislative building where a legislature meets and makes laws for its respective political entity.

Specific capitols include:

* United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

* Numerou ...

in Washington to the old Mt. Clare Depot in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

.

Commercial telegraphy

Cooke and Wheatstone system

The first commercial electrical telegraph was the Cooke and Wheatstone system. A demonstration four-needle system was installed on the Euston to

The first commercial electrical telegraph was the Cooke and Wheatstone system. A demonstration four-needle system was installed on the Euston to Camden Town

Camden Town (), often shortened to Camden, is a district of northwest London, England, north of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Camden, and identified in the London Plan as o ...

section of Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father. R ...

's London and Birmingham Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom, in operation from 1833 to 1846, when it became part of the London and North Western Railway (L&NWR).

The railway line which the company opened in 1838, betw ...

in 1837 for signalling rope-hauling of locomotives. It was rejected in favour of pneumatic whistles.Bowers, page 129 Cooke and Wheatstone had their first commercial success with a system installed on the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and r ...

over the from Paddington station

Paddington, also known as London Paddington, is a Central London railway terminus and London Underground station complex, located on Praed Street in the Paddington area. The site has been the London terminus of services provided by the Great We ...

to West Drayton

West Drayton is a suburban town in the London Borough of Hillingdon. It was an ancient parish in the county of Middlesex and from 1929 was part of the Yiewsley and West Drayton Urban District, which became part of Greater London in 1965. The s ...

in 1838. This was a five-needle, six-wire system. A major advantage of this system was it displayed the letter being sent so operators did not need to learn a code. This system suffered from failing insulation on the underground cables. When the line was extended to Slough

Slough () is a town and unparished area in the unitary authority of the same name in Berkshire, England, bordering west London. It lies in the Thames Valley, west of central London and north-east of Reading, at the intersection of the M4, ...

in 1843, the telegraph was converted to a one-needle, two-wire system with uninsulated wires on poles. The cost of installing wires was ultimately more economically significant than the cost of training operators. The one-needle telegraph proved highly successful on British railways, and 15,000 sets were still in use at the end of the nineteenth century. Some remained in service in the 1930s. The Electric Telegraph Company

The Electric Telegraph Company (ETC) was a British telegraph company founded in 1846 by William Fothergill Cooke and John Ricardo. It was the world's first public telegraph company. The equipment used was the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, ...

, the world's first public telegraphy company was formed in 1845 by financier John Lewis Ricardo

John Lewis Ricardo (1812 – 2 August 1862) was a British businessman and politician.

He was the son of Jacob Ricardo and nephew of the economist David Ricardo. In 1841 he married Catherine Duff (c.1820 – 1869), the daughter of General Sir A ...

and Cooke.

Wheatstone ABC telegraph

Wheatstone developed a practical alphabetical system in 1840 called the A.B.C. System, used mostly on private wires. This consisted of a "communicator" at the sending end and an "indicator" at the receiving end. The communicator consisted of a circular dial with a pointer and the 26 letters of the alphabet (and four punctuation marks) around its circumference. Against each letter was a key that could be pressed. A transmission would begin with the pointers on the dials at both ends set to the start position. The transmitting operator would then press down the key corresponding to the letter to be transmitted. In the base of the communicator was a

Wheatstone developed a practical alphabetical system in 1840 called the A.B.C. System, used mostly on private wires. This consisted of a "communicator" at the sending end and an "indicator" at the receiving end. The communicator consisted of a circular dial with a pointer and the 26 letters of the alphabet (and four punctuation marks) around its circumference. Against each letter was a key that could be pressed. A transmission would begin with the pointers on the dials at both ends set to the start position. The transmitting operator would then press down the key corresponding to the letter to be transmitted. In the base of the communicator was a magneto

A magneto is an electrical generator that uses permanent magnets to produce periodic pulses of alternating current. Unlike a dynamo, a magneto does not contain a commutator to produce direct current. It is categorized as a form of alternator ...

actuated by a handle on the front. This would be turned to apply an alternating voltage to the line. Each half cycle of the current would advance the pointers at both ends by one position. When the pointer reached the position of the depressed key, it would stop and the magneto would be disconnected from the line. The communicator's pointer was geared to the magneto mechanism. The indicator's pointer was moved by a polarised electromagnet whose armature was coupled to it through an escapement

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to ...

. Thus the alternating line voltage moved the indicator's pointer on to the position of the depressed key on the communicator. Pressing another key would then release the pointer and the previous key, and re-connect the magneto to the line. These machines were very robust and simple to operate, and they stayed in use in Britain until well into the 20th century.

Morse system

The Morse system uses a single wire between offices. At the sending station, an operator taps on a switch called a

The Morse system uses a single wire between offices. At the sending station, an operator taps on a switch called a telegraph key

A telegraph key is a specialized electrical switch used by a trained operator to transmit text messages in Morse code in a telegraphy system. Keys are used in all forms of electrical telegraph systems, including landline (also called wire) t ...

, spelling out text messages in Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

. Originally, the armature was intended to make marks on paper tape, but operators learned to interpret the clicks and it was more efficient to write down the message directly.

In 1851, a conference in Vienna of countries in the German-Austrian Telegraph Union (which included many central European countries) adopted the Morse telegraph as the system for international communications. The international Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

adopted was considerably modified from the original American Morse code

American Morse Code — also known as Railroad Morse—is the latter-day name for the original version of the Morse Code developed in the mid-1840s, by Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail for their electric telegraph. The "American" qualifier was added ...

, and was based on a code used on Hamburg railways ( Gerke, 1848). A common code was a necessary step to allow direct telegraph connection between countries. With different codes, additional operators were required to translate and retransmit the message. In 1865, a conference in Paris adopted Gerke's code as the International Morse code and was henceforth the international standard. The US, however, continued to use American Morse code internally for some time, hence international messages required retransmission in both directions.

In the United States, the Morse/Vail telegraph was quickly deployed in the two decades following the first demonstration in 1844. The overland telegraph

The Australian Overland Telegraph Line was a telegraphy system to send messages over long distances using cables and electric signals. It spanned between Darwin, in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia, and Adelaide, the capital o ...

connected the west coast of the continent to the east coast by 24 October 1861, bringing an end to the Pony Express

The Pony Express was an American express mail service that used relays of horse-mounted riders. It operated from April 3, 1860, to October 26, 1861, between Missouri and California. It was operated by the Central Overland California and Pi ...

.

Foy–Breguet system

France was slow to adopt the electrical telegraph, because of the extensive

France was slow to adopt the electrical telegraph, because of the extensive optical telegraph

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and ...

system built during the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislativ ...

. There was also serious concern that an electrical telegraph could be quickly put out of action by enemy saboteurs, something that was much more difficult to do with optical telegraphs which had no exposed hardware between stations. The Foy-Breguet telegraph was eventually adopted. This was a two-needle system using two signal wires but displayed in a uniquely different way to other needle telegraphs. The needles made symbols similar to the Chappe optical system symbols, making it more familiar to the telegraph operators. The optical system was decommissioned starting in 1846, but not completely until 1855. In that year the Foy-Breguet system was replaced with the Morse system.

Expansion

As well as the rapid expansion of the use of the telegraphs along the railways, they soon spread into the field of mass communication with the instruments being installed inpost office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional servi ...

s. The era of mass personal communication had begun. Telegraph networks were expensive to build, but financing was readily available, especially from London bankers. By 1852, National systems were in operation in major countries:

The New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company, for example, was created in 1852 in Rochester, New York and eventually became the Western Union Telegraph Company

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

. Although many countries had telegraph networks, there was no ''worldwide'' interconnection. Message by post was still the primary means of communication to countries outside Europe.

Telegraphy was introduced in Central Asia during the 1870s.

Telegraphic improvements

A continuing goal in telegraphy was to reduce the cost per message by reducing hand-work, or increasing the sending rate. There were many experiments with moving pointers, and various electrical encodings. However, most systems were too complicated and unreliable. A successful expedient to reduce the cost per message was the development oftelegraphese

Telegram style, telegraph style, telegraphic style, or telegraphese is a clipped way of writing which abbreviates words and packs information into the smallest possible number of words or characters. It originated in the telegraph age when telecom ...

.

The first system that did not require skilled technicians to operate was Charles Wheatstone's ABC system in 1840 in which the letters of the alphabet were arranged around a clock-face, and the signal caused a needle to indicate the letter. This early system required the receiver to be present in real time to record the message and it reached speeds of up to 15 words a minute.

In 1846, Alexander Bain patented a chemical telegraph in Edinburgh. The signal current moved an iron pen across a moving paper tape soaked in a mixture of ammonium nitrate and potassium ferrocyanide, decomposing the chemical and producing readable blue marks in Morse code. The speed of the printing telegraph was 16 and a half words per minute, but messages still required translation into English by live copyists. Chemical telegraphy came to an end in the US in 1851, when the Morse group defeated the Bain patent in the US District Court.

For a brief period, starting with the New York–Boston line in 1848, some telegraph networks began to employ sound operators, who were trained to understand Morse code aurally. Gradually, the use of sound operators eliminated the need for telegraph receivers to include register and tape. Instead, the receiving instrument was developed into a "sounder", an electromagnet that was energized by a current and attracted a small iron lever. When the sounding key was opened or closed, the sounder lever struck an anvil. The Morse operator distinguished a dot and a dash by the short or long interval between the two clicks. The message was then written out in long-hand.

Royal Earl House

Royal Earl House (9 September 181425 February 1895) was the inventor of the first printing telegraph, which is now kept in the Smithsonian Institution. His nephew Henry Alonzo House is also a noted early American inventor.

Royal Earl House spen ...

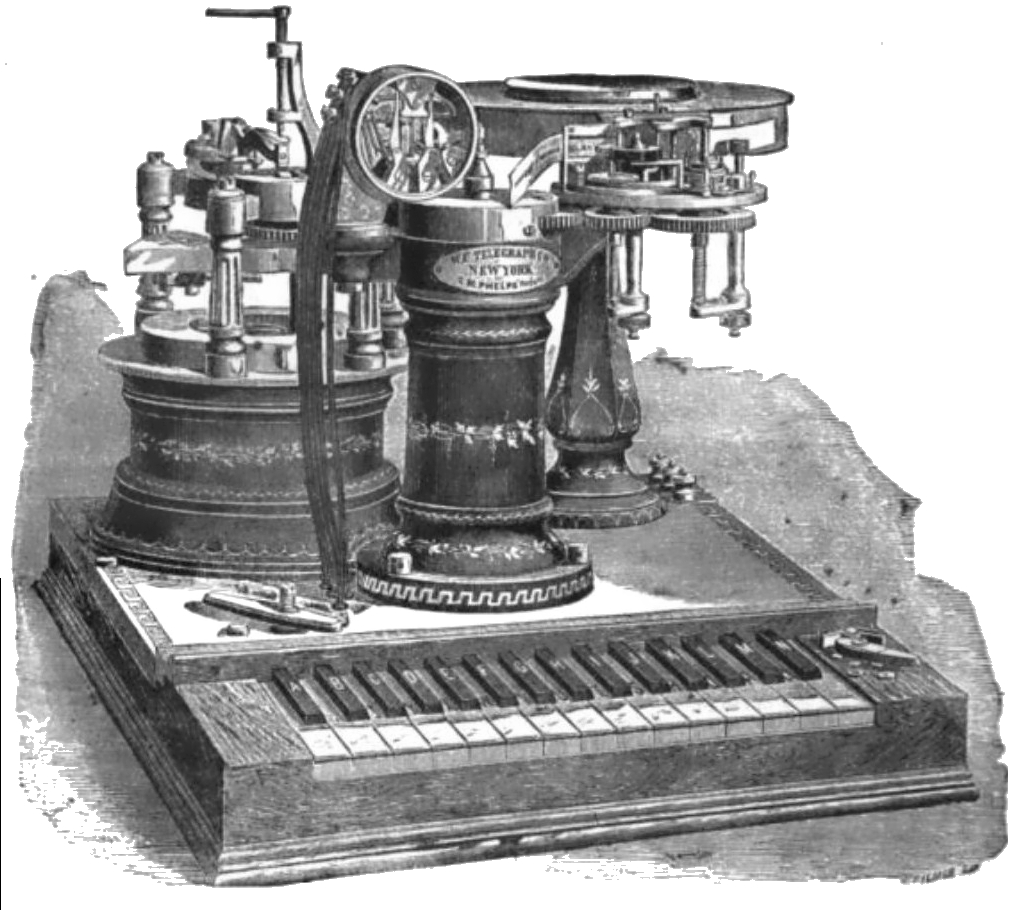

developed and patented a letter-printing telegraph system in 1846 which employed an alphabetic keyboard for the transmitter and automatically printed the letters on paper at the receiver, and followed this up with a steam-powered version in 1852. Advocates of printing telegraphy said it would eliminate Morse operators' errors. The House machine was used on four main American telegraph lines by 1852. The speed of the House machine was announced as 2600 words an hour.

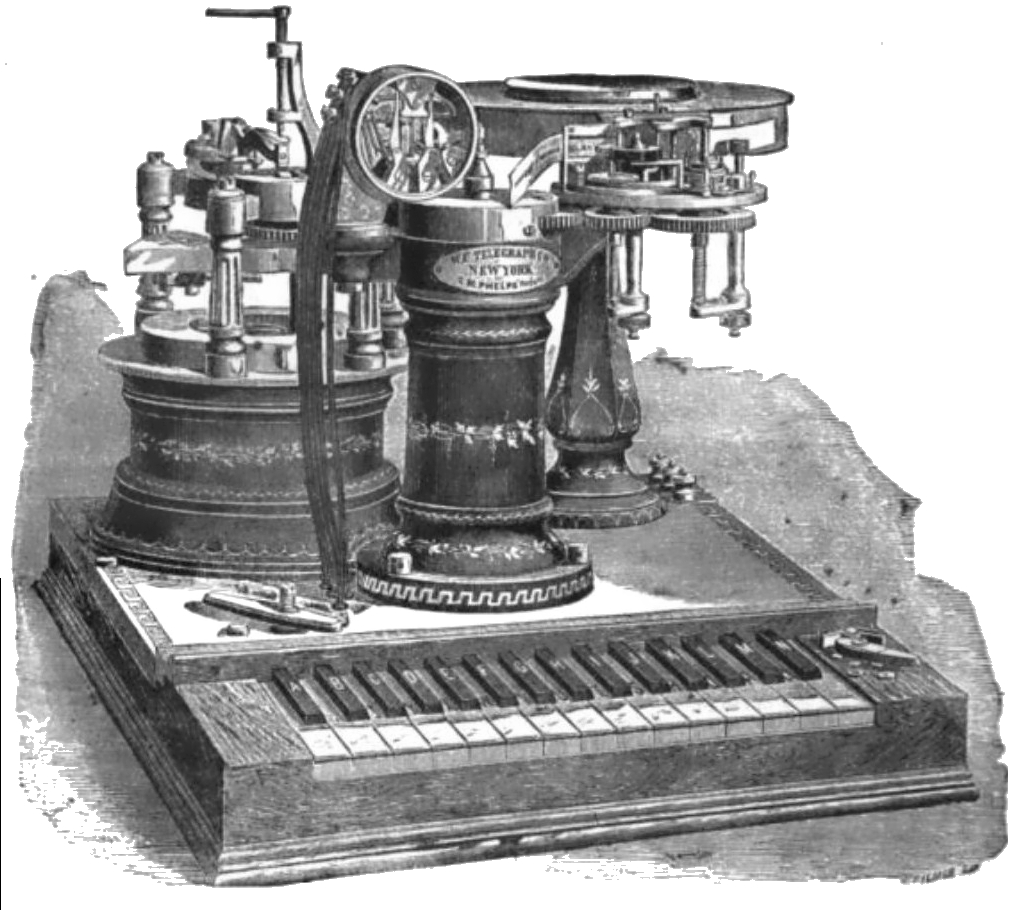

David Edward Hughes

David Edward Hughes (16 May 1830 – 22 January 1900), was a British-American inventor, practical experimenter, and professor of music known for his work on the printing telegraph and the microphone. He is generally considered to have bee ...

invented the printing telegraph in 1855; it used a keyboard of 26 keys for the alphabet and a spinning type wheel that determined the letter being transmitted by the length of time that had elapsed since the previous transmission. The system allowed for automatic recording on the receiving end. The system was very stable and accurate and became accepted around the world.

The next improvement was the Baudot code

The Baudot code is an early character encoding for telegraphy invented by Émile Baudot in the 1870s. It was the predecessor to the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), the most common teleprinter code in use until the advent of ASCII. ...

of 1874. French engineer Émile Baudot

Jean-Maurice-Émile Baudot (; 11 September 1845 – 28 March 1903), French telegraph engineer and inventor of the first means of digital communication Baudot code, was one of the pioneers of telecommunications. He invented a multiplexed print ...

patented a printing telegraph in which the signals were translated automatically into typographic characters. Each character was assigned a five-bit code, mechanically interpreted from the state of five on/off switches. Operators had to maintain a steady rhythm, and the usual speed of operation was 30 words per minute.

By this point, reception had been automated, but the speed and accuracy of the transmission were still limited to the skill of the human operator. The first practical automated system was patented by Charles Wheatstone. The message (in Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

) was typed onto a piece of perforated tape using a keyboard-like device called the 'Stick Punch'. The transmitter automatically ran the tape through and transmitted the message at the then exceptionally high speed of 70 words per minute.

Teleprinters

An early successful

An early successful teleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initi ...

was invented by Frederick G. Creed Frederick George Creed (6 October 1871 – 11 December 1957) was a Canadian inventor, who spent most of his adult life in Britain. He worked in the field of telecommunications, and is particularly remembered as a key figure in the development of the ...

. In Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

he created his first keyboard perforator, which used compressed air to punch the holes. He also created a reperforator (receiving perforator) and a printer. The reperforator punched incoming Morse signals onto paper tape and the printer decoded this tape to produce alphanumeric characters on plain paper. This was the origin of the Creed High Speed Automatic Printing System, which could run at an unprecedented 200 words per minute. His system was adopted by the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publis ...

'' for daily transmission of the newspaper contents.

With the invention of the teletypewriter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initia ...

, telegraphic encoding became fully automated. Early teletypewriters used the ITA-1 Baudot code

The Baudot code is an early character encoding for telegraphy invented by Émile Baudot in the 1870s. It was the predecessor to the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), the most common teleprinter code in use until the advent of ASCII. ...

, a five-bit code. This yielded only thirty-two codes, so it was over-defined into two "shifts", "letters" and "figures". An explicit, unshared shift code prefaced each set of letters and figures. In 1901, Baudot's code was modified by Donald Murray.

In the 1930s, teleprinters were produced by Teletype

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initia ...

in the US, Creed in Britain and Siemens in Germany.

By 1935, message routing was the last great barrier to full automation. Large telegraphy providers began to develop systems that used telephone-like rotary dialling to connect teletypewriters. These resulting systems were called "Telex" (TELegraph EXchange). Telex machines first performed rotary-telephone-style pulse dialling

Pulse dialing is a signaling technology in telecommunications in which a direct current local loop circuit is interrupted according to a defined coding system for each signal transmitted, usually a digit. This lends the method the often used name ...

for circuit switching

Circuit switching is a method of implementing a telecommunications network in which two network nodes establish a dedicated communications channel ( circuit) through the network before the nodes may communicate. The circuit guarantees the full ...

, and then sent data by ITA2

The Baudot code is an early character encoding for telegraphy invented by Émile Baudot in the 1870s. It was the predecessor to the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), the most common teleprinter code in use until the advent of ASCII. ...

. This "type A" Telex routing functionally automated message routing.

The first wide-coverage Telex network was implemented in Germany during the 1930s as a network used to communicate within the government.

At the rate of 45.45 (±0.5%) baud

In telecommunication and electronics, baud (; symbol: Bd) is a common unit of measurement of symbol rate, which is one of the components that determine the speed of communication over a data channel.

It is the unit for symbol rate or modulation ...

– considered speedy at the time – up to 25 telex channels could share a single long-distance telephone channel by using '' voice frequency telegraphy multiplexing

In telecommunications and computer networking, multiplexing (sometimes contracted to muxing) is a method by which multiple analog or digital signals are combined into one signal over a shared medium. The aim is to share a scarce resource - a ...

'', making telex the least expensive method of reliable long-distance communication.

Automatic teleprinter exchange service was introduced into Canada by CPR Telegraphs

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

and CN Telegraph

The Canadian National Railway Company (french: Compagnie des chemins de fer nationaux du Canada) is a Canadian Class I freight railway headquartered in Montreal, Quebec, which serves Canada and the Midwestern and Southern United States.

CN i ...

in July 1957 and in 1958, Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

started to build a Telex network in the United States.

The harmonic telegraph

The most expensive aspect of a telegraph system was the installation – the laying of the wire, which was often very long. The costs would be better covered by finding a way to send more than one message at a time through the single wire, thus increasing revenue per wire. Early devices included the duplex and the quadruplex which allowed, respectively, one or two telegraph transmissions in each direction. However, an even greater number of channels was desired on the busiest lines. In the latter half of the 1800s, several inventors worked towards creating a method for doing just that, including Charles Bourseul,Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These invent ...

, Elisha Gray

Elisha Gray (August 2, 1835 – January 21, 1901) was an American electrical engineer who co-founded the Western Electric Manufacturing Company. Gray is best known for his development of a telephone prototype in 1876 in Highland Park, Illinois ...

, and Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and T ...

.

One approach was to have resonators of several different frequencies act as carriers of a modulated on-off signal. This was the harmonic telegraph, a form of frequency-division multiplexing

In telecommunications, frequency-division multiplexing (FDM) is a technique by which the total bandwidth (signal processing), bandwidth available in a communication channel, communication medium is divided into a series of non-overlapping freque ...

. These various frequencies, referred to as harmonics, could then be combined into one complex signal and sent down the single wire. On the receiving end, the frequencies would be separated with a matching set of resonators.

With a set of frequencies being carried down a single wire, it was realized that the human voice itself could be transmitted electrically through the wire. This effort led to the invention of the telephone

The invention of the telephone was the culmination of work done by more than one individual, and led to an array of lawsuits relating to the patent claims of several individuals and numerous companies.

Early development

The concept of the ...

. (While the work toward packing multiple telegraph signals onto one wire led to telephony, later advances would pack multiple voice signals onto one wire by increasing the bandwidth by modulating frequencies much higher than human hearing. Eventually, the bandwidth was widened much further by using laser light signals sent through fiber optic cables. Fiber optic transmission can carry 25,000 telephone signals simultaneously down a single fiber.)

Oceanic telegraph cables

Soon after the first successful telegraph systems were operational, the possibility of transmitting messages across the sea by way of

Soon after the first successful telegraph systems were operational, the possibility of transmitting messages across the sea by way of submarine communications cable

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the sea bed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean and sea. The first submarine communications cables laid beginning in the 1850s carried tel ...

s was first proposed. One of the primary technical challenges was to sufficiently insulate the submarine cable to prevent the electric current from leaking out into the water. In 1842, a Scottish surgeon William Montgomerie

William Montgomerie (1797–1856) was a Scottish military doctor with the East India Company, and later head of the medical department at Singapore. He is best known for promoting the use of gutta-percha in Europe. This material was an import ...

introduced gutta-percha

Gutta-percha is a tree of the genus ''Palaquium'' in the family Sapotaceae. The name also refers to the rigid, naturally biologically inert, resilient, electrically nonconductive, thermoplastic latex derived from the tree, particularly from ' ...

, the adhesive juice of the ''Palaquium gutta

''Palaquium gutta'' is a tree in the family Sapotaceae. The specific epithet ' is from the Malay word ''getah'' meaning "sap or latex". It is known in Indonesia as ''karet oblong''.

Description

''Palaquium gutta'' grows up to tall. The bark i ...

'' tree, to Europe. Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic induction, ...

and Wheatstone soon discovered the merits of gutta-percha as an insulator, and in 1845, the latter suggested that it should be employed to cover the wire which was proposed to be laid from Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidston ...

to Calais. Gutta-percha was used as insulation on a wire laid across the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, sour ...

between Deutz and Cologne. In 1849, C. V. Walker, electrician to the South Eastern Railway, submerged a wire coated with gutta-percha off the coast from Folkestone, which was tested successfully.

John Watkins Brett

John Watkins Brett (1805–1863) was an English telegraph engineer.

Life

Brett was the son of a cabinetmaker, William Brett of Bristol, and was born in that city in 1805. Brett is known as the founder of submarine telegraphy. He formed the Sub ...

, an engineer from Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, sought and obtained permission from Louis-Philippe

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary War ...

in 1847 to establish telegraphic communication between France and England. The first undersea cable was laid in 1850, connecting the two countries and was followed by connections to Ireland and the Low Countries.

The Atlantic Telegraph Company

The Atlantic Telegraph Company was a company formed on 6 November 1856 to undertake and exploit a commercial telegraph cable across the Atlantic ocean, the first such telecommunications link.

History

Cyrus Field, American businessman and financ ...

was formed in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

in 1856 to undertake to construct a commercial telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean. It was successfully completed on 18 July 1866 by the ship SS ''Great Eastern'', captained by Sir James Anderson, after many mishaps along the away. John Pender, one of the men on the Great Eastern, later founded several telecommunications companies primarily laying cables between Britain and Southeast Asia. Earlier transatlantic submarine cables Submarine cable is any electrical cable that is laid on the seabed, although the term is often extended to encompass cables laid on the bottom of large freshwater bodies of water.

Examples include:

*Submarine communications cable

*Submarine power ...

installations were attempted in 1857, 1858 and 1865. The 1857 cable only operated intermittently for a few days or weeks before it failed. The study of underwater telegraph cables accelerated interest in mathematical analysis of very long transmission line

In electrical engineering, a transmission line is a specialized cable or other structure designed to conduct electromagnetic waves in a contained manner. The term applies when the conductors are long enough that the wave nature of the transmis ...

s. The telegraph lines from Britain to India were connected in 1870. (Those several companies combined to form the ''Eastern Telegraph Company'' in 1872.) The HMS ''Challenger'' expedition in 1873–1876 mapped the ocean floor for future underwater telegraph cables.

Australia was first linked to the rest of the world in October 1872 by a submarine telegraph cable at Darwin. This brought news reports from the rest of the world. The telegraph across the Pacific was completed in 1902, finally encircling the world.

From the 1850s until well into the 20th century, British submarine cable systems dominated the world system. This was set out as a formal strategic goal, which became known as the All Red Line

The All Red Line was a system of electrical telegraphs that linked much of the British Empire. It was inaugurated on 31 October 1902. The informal name derives from the common practice of colouring the territory of the British Empire red or ...

. In 1896, there were thirty cable laying ships in the world and twenty-four of them were owned by British companies. In 1892, British companies owned and operated two-thirds of the world's cables and by 1923, their share was still 42.7 percent.

Cable and Wireless Company

Cable & Wireless was a British telecommunications company that traced its origins back to the 1860s, with Sir

Cable & Wireless was a British telecommunications company that traced its origins back to the 1860s, with Sir John Pender

Sir John Pender KCMG GCMG FSA FRSE (10 September 1816 – 7 July 1896) was a Scottish submarine communications cable pioneer and politician.

Early life

He was born in the Vale of Leven, Scotland, the son of James Pender and his wife, Marion M ...

as the founder, although the name was only adopted in 1934. It was formed from successive mergers including:

*The Falmouth, Malta, Gibraltar Telegraph Company

*The British Indian Submarine Telegraph Company

*The Marseilles, Algiers and Malta Telegraph Company

*The Eastern Telegraph Company

*The Eastern Extension Australasia and China Telegraph Company

*The Eastern and Associated Telegraph Companies

Telegraphy and longitude

Main article § Section: . The telegraph was very important for sending time signals to determine longitude, providing greater accuracy than previously available. Longitude was measured by comparing local time (for example local noon occurs when the sun is at its highest above the horizon) with absolute time (a time that is the same for an observer anywhere on earth). If the local times of two places differ by one hour, the difference in longitude between them is 15° (360°/24h). Before telegraphy, absolute time could be obtained from astronomical events, such aseclipses

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three c ...

, occultations or lunar distances, or by transporting an accurate clock (a chronometer) from one location to the other.

The idea of using the telegraph to transmit a time signal for longitude determination was suggested by François Arago