early medieval Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scotland was divided into a series of kingdoms in the early

As the first half of the period is largely

As the first half of the period is largely

The confederation of Pictish tribes that developed north of the

The confederation of Pictish tribes that developed north of the

The Gaelic overkingdom of Dál Riata was on the western coast of modern Scotland, with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. It probably ruled from the fortress of Dunadd, now near Kilmartin in

The Gaelic overkingdom of Dál Riata was on the western coast of modern Scotland, with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. It probably ruled from the fortress of Dunadd, now near Kilmartin in

''Alt Clut'' (named after the Brythonic name for Dumbarton Rock, the Medieval capital of the

''Alt Clut'' (named after the Brythonic name for Dumbarton Rock, the Medieval capital of the

The Brythonic successor states of what is now the modern Anglo-Scottish border region are referred to by Welsh scholars as part of ''Yr

The Brythonic successor states of what is now the modern Anglo-Scottish border region are referred to by Welsh scholars as part of ''Yr

The balance between rival kingdoms was transformed in 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain. Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. The king of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the king of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, were among the dead after a major defeat by the Vikings in 839. A mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement into south-west Scotland produced the Gall-Gaidel, the ''Norse Irish'', from which the region gets the modern name

The balance between rival kingdoms was transformed in 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain. Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. The king of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the king of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, were among the dead after a major defeat by the Vikings in 839. A mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement into south-west Scotland produced the Gall-Gaidel, the ''Norse Irish'', from which the region gets the modern name

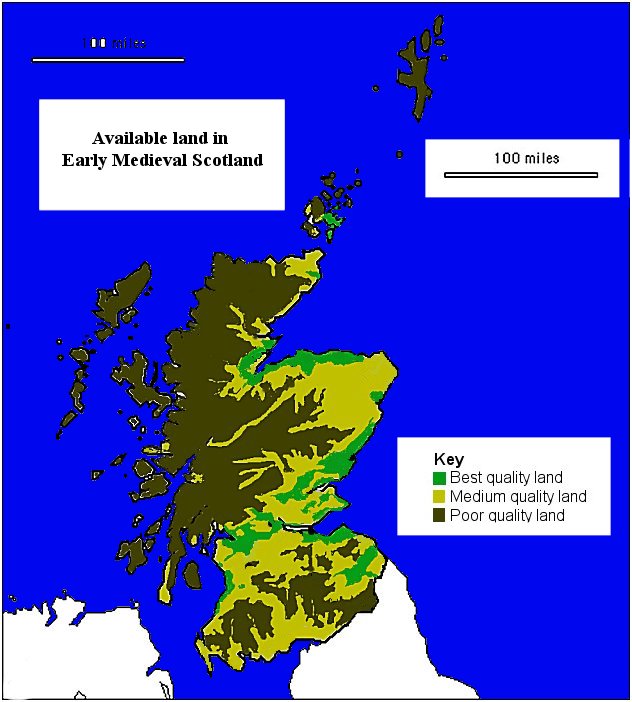

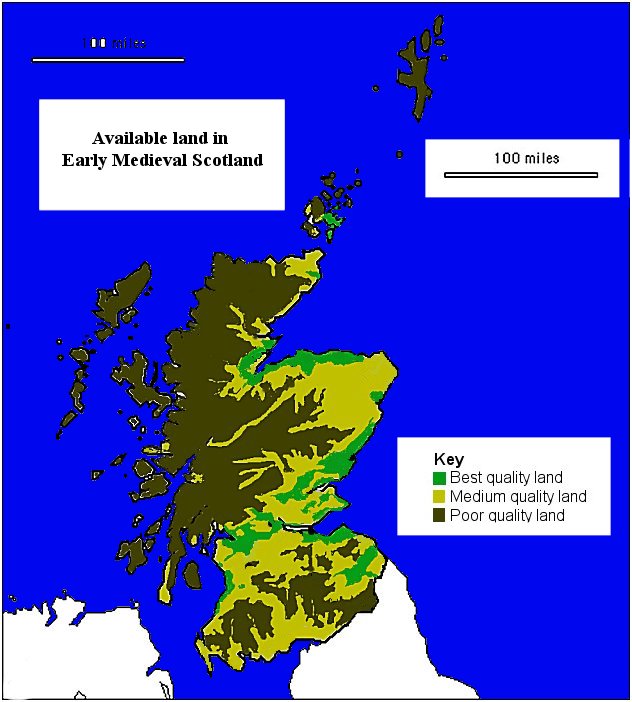

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it has roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles. Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 metres above sea level. Its east Atlantic position means that it experiences heavy rainfall, especially in the west. This encouraged the spread of blanket

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it has roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles. Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 metres above sea level. Its east Atlantic position means that it experiences heavy rainfall, especially in the west. This encouraged the spread of blanket

This period saw dramatic changes in the geography of language. Modern linguists divide the Celtic languages into two major groups, the

This period saw dramatic changes in the geography of language. Modern linguists divide the Celtic languages into two major groups, the

Lacking the urban centres created under the Romans in the rest of Britain, the economy of Scotland in the early Middle Ages was overwhelmingly agricultural. Without significant transport links and wider markets, most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by

Lacking the urban centres created under the Romans in the rest of Britain, the economy of Scotland in the early Middle Ages was overwhelmingly agricultural. Without significant transport links and wider markets, most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by

The primary unit of social organisation in Germanic and Celtic Europe was the kin group.C. Haigh, ''The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), , pp. 82–4. The mention of descent through the female line in the ruling families of the Picts in later sources and the recurrence of leaders clearly from outside of Pictish society, has led to the conclusion that their system of descent was

The primary unit of social organisation in Germanic and Celtic Europe was the kin group.C. Haigh, ''The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), , pp. 82–4. The mention of descent through the female line in the ruling families of the Picts in later sources and the recurrence of leaders clearly from outside of Pictish society, has led to the conclusion that their system of descent was

In the early Medieval period, British kingship was not inherited in a direct line from previous kings, as would be the case in the late Middle Ages. There were instead a number of candidates for kingship, who usually needed to be a member of a particular dynasty and to claim descent from a particular ancestor. Kingship could be multi-layered and very fluid. The Pictish kings of Fortriu were probably acting as overlords of other Pictish kings for much of this period and occasionally were able to assert an overlordship over non-Pictish kings, but occasionally themselves had to acknowledge the overlordship of external rulers, both Anglian and British. Such relationships may have placed obligations to pay tribute or to supply armed forces. After a victory, sub-kings may have received rewards in return for this service. Interaction with and intermarriage into the ruling families of subject kingdoms may have opened the way to absorption of such sub-kingdoms and, although there might be later overturnings of these mergers, it is likely that a complex process by which kingship was gradually monopolised by a handful of the most powerful dynasties was taking place.B. Yorke, "Kings and kingship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 76–90.

The primary role of the king was to act as a war leader, reflected in the very small number of minority or female reigning monarchs in the period. Kings organised the defence of their people's lands, property and persons and negotiated with other kings to secure these things. If they failed to do so, the settlements might be raided, destroyed or annexed, and the populations killed or taken into slavery. Kings also engaged in the low-level warfare of raiding and the more ambitious full-scale warfare that led to conflicts of large armies and alliances, and which could be undertaken over relatively large distances, such as the expedition to Orkney by Dál Riata in 581 or the Northumbrian attack on Ireland in 684.

Kingship had its ritual aspects. The kings of Dál Riata were inaugurated by putting their foot in a footprint carved in stone, signifying that they would follow in the footsteps of their predecessors.J. Haywood, ''The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age'' (London: Pearson Education, 2004), , p. 125. The kingship of the unified kingdom of Alba had

In the early Medieval period, British kingship was not inherited in a direct line from previous kings, as would be the case in the late Middle Ages. There were instead a number of candidates for kingship, who usually needed to be a member of a particular dynasty and to claim descent from a particular ancestor. Kingship could be multi-layered and very fluid. The Pictish kings of Fortriu were probably acting as overlords of other Pictish kings for much of this period and occasionally were able to assert an overlordship over non-Pictish kings, but occasionally themselves had to acknowledge the overlordship of external rulers, both Anglian and British. Such relationships may have placed obligations to pay tribute or to supply armed forces. After a victory, sub-kings may have received rewards in return for this service. Interaction with and intermarriage into the ruling families of subject kingdoms may have opened the way to absorption of such sub-kingdoms and, although there might be later overturnings of these mergers, it is likely that a complex process by which kingship was gradually monopolised by a handful of the most powerful dynasties was taking place.B. Yorke, "Kings and kingship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 76–90.

The primary role of the king was to act as a war leader, reflected in the very small number of minority or female reigning monarchs in the period. Kings organised the defence of their people's lands, property and persons and negotiated with other kings to secure these things. If they failed to do so, the settlements might be raided, destroyed or annexed, and the populations killed or taken into slavery. Kings also engaged in the low-level warfare of raiding and the more ambitious full-scale warfare that led to conflicts of large armies and alliances, and which could be undertaken over relatively large distances, such as the expedition to Orkney by Dál Riata in 581 or the Northumbrian attack on Ireland in 684.

Kingship had its ritual aspects. The kings of Dál Riata were inaugurated by putting their foot in a footprint carved in stone, signifying that they would follow in the footsteps of their predecessors.J. Haywood, ''The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age'' (London: Pearson Education, 2004), , p. 125. The kingship of the unified kingdom of Alba had

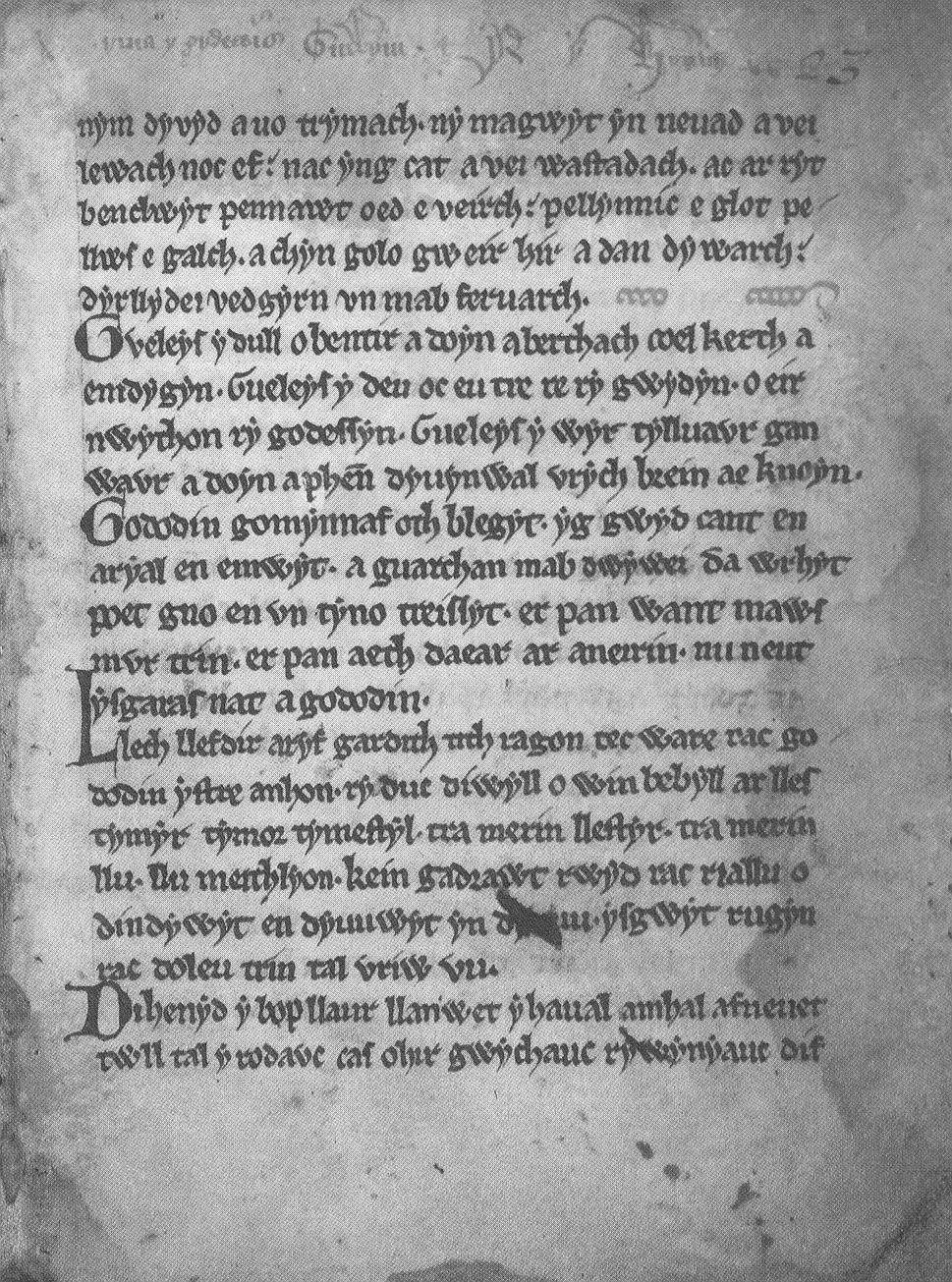

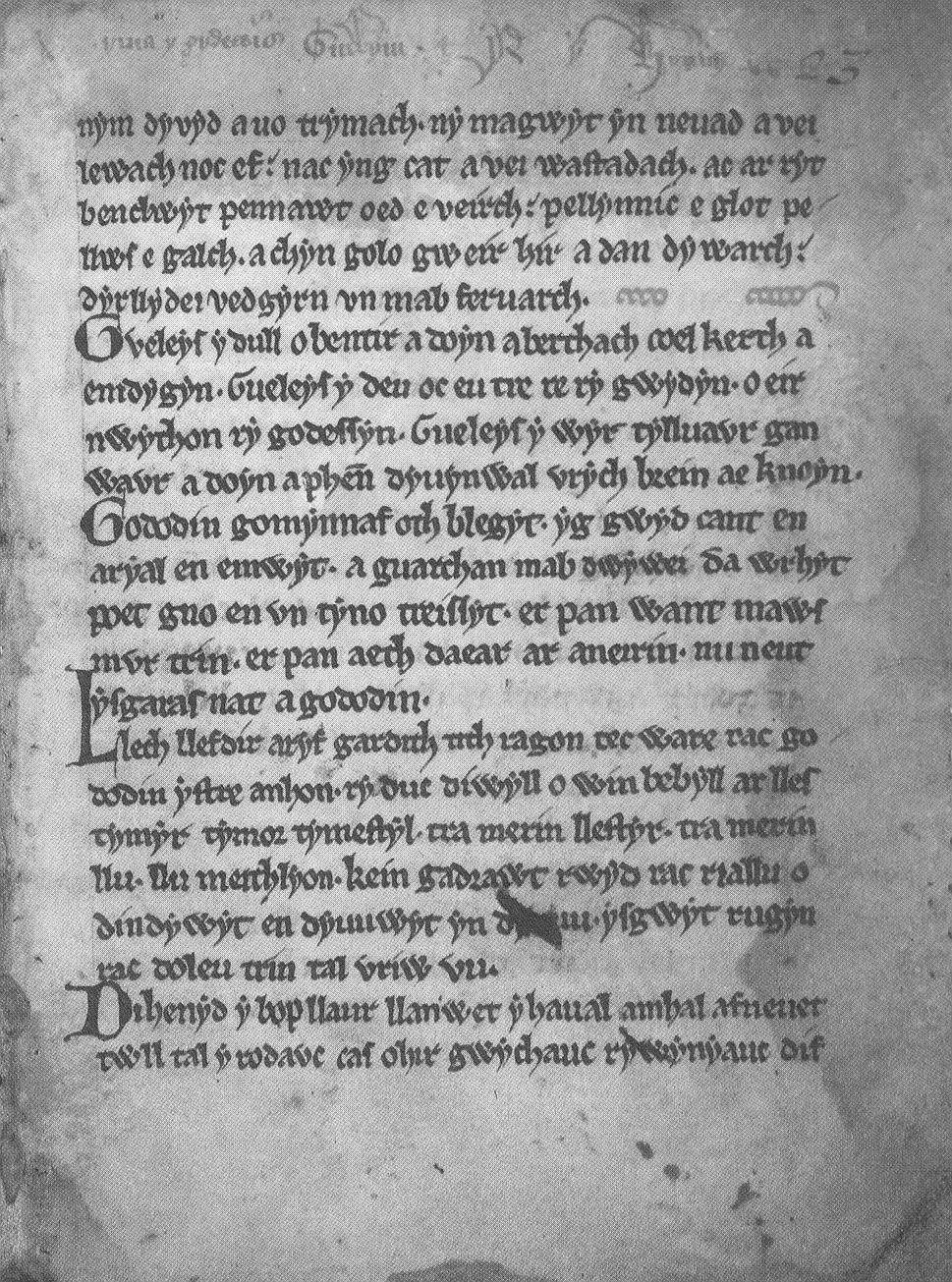

At the most basic level, a king's power rested on the existence of his bodyguard or war-band. In the British language, this was called the ''teulu'', as in ''teulu Dewr'' (the "War-band of Deira"). In Latin the word is either ''comitatus'' or ''tutores'', or even ''familia''; ''tutores'' is the most common word in this period, and derives for the Latin verb ''tueor'', meaning "defend, preserve from danger". The war-band functioned as an extension of the ruler's legal person, and was the core of the larger armies that were mobilised from time to time for campaigns of significant size. In peacetime, the war-band's activity was centred on the "Great Hall". Here, in both Germanic and Celtic cultures, the feasting, drinking and other forms of male bonding that kept up the war-band's integrity would take place. In the epic poem

At the most basic level, a king's power rested on the existence of his bodyguard or war-band. In the British language, this was called the ''teulu'', as in ''teulu Dewr'' (the "War-band of Deira"). In Latin the word is either ''comitatus'' or ''tutores'', or even ''familia''; ''tutores'' is the most common word in this period, and derives for the Latin verb ''tueor'', meaning "defend, preserve from danger". The war-band functioned as an extension of the ruler's legal person, and was the core of the larger armies that were mobilised from time to time for campaigns of significant size. In peacetime, the war-band's activity was centred on the "Great Hall". Here, in both Germanic and Celtic cultures, the feasting, drinking and other forms of male bonding that kept up the war-band's integrity would take place. In the epic poem

The roots of Christianity in Scotland can probably be found among the soldiers, notably Saint Kessog, son of the king of Cashel, and ordinary Roman citizens in the vicinity of Hadrian's Wall. The archaeology of the Roman period indicates that the northern parts of the Roman province of

The roots of Christianity in Scotland can probably be found among the soldiers, notably Saint Kessog, son of the king of Cashel, and ordinary Roman citizens in the vicinity of Hadrian's Wall. The archaeology of the Roman period indicates that the northern parts of the Roman province of

Celtic Christianity differed in some in respects from that based on Rome, most importantly on the issues of how Easter was calculated and the method of

Celtic Christianity differed in some in respects from that based on Rome, most importantly on the issues of how Easter was calculated and the method of

From the 5th to the mid-9th centuries the art of the Picts is primarily known through stone sculpture, and a smaller number of pieces of metalwork, often of very high quality. After the conversion of the Picts and the cultural assimilation of Pictish culture into that of the Scots and Angles, elements of Pictish art became incorporated into the style known as

From the 5th to the mid-9th centuries the art of the Picts is primarily known through stone sculpture, and a smaller number of pieces of metalwork, often of very high quality. After the conversion of the Picts and the cultural assimilation of Pictish culture into that of the Scots and Angles, elements of Pictish art became incorporated into the style known as

Metalwork has been found throughout Pictland; the Picts appear to have had a considerable amount of silver available, probably from raiding further south, or the payment of subsidies to keep them from doing so. The very large hoard of late Roman

Metalwork has been found throughout Pictland; the Picts appear to have had a considerable amount of silver available, probably from raiding further south, or the payment of subsidies to keep them from doing so. The very large hoard of late Roman

"Citadel of the first Scots"

''British Archaeology'', 62, December 2001. Retrieved 2 December 2010. In the 8th and 9th centuries the Pictish elite adopted true penannular

Insular art, or Hiberno-Saxon art, is the name given to the common style produced in Scotland, Britain and Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon forms. Surviving examples of Insular art are found in metalwork, carving, but mainly in

Insular art, or Hiberno-Saxon art, is the name given to the common style produced in Scotland, Britain and Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon forms. Surviving examples of Insular art are found in metalwork, carving, but mainly in

Early chapels tended to have square-ended converging walls, similar to Irish chapels of this period.T. W. West, ''Discovering Scottish Architecture'' (Botley: Osprey, 1985), , p. 8. Medieval parish church architecture in Scotland was typically much less elaborate than in England, with many churches remaining simple oblongs, without

Early chapels tended to have square-ended converging walls, similar to Irish chapels of this period.T. W. West, ''Discovering Scottish Architecture'' (Botley: Osprey, 1985), , p. 8. Medieval parish church architecture in Scotland was typically much less elaborate than in England, with many churches remaining simple oblongs, without

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, i.e. between the end of Roman authority in southern and central Britain from around 400 CE and the rise of the kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba ( la, Scotia; sga, Alba) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the ...

in 900 CE. Of these, the four most important to emerge were the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

, the Gaels of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is no ...

, the Britons of Alt Clut

Dumbarton Castle ( gd, Dùn Breatainn, ; ) has the longest recorded history of any stronghold in Scotland. It sits on a volcanic plug of basalt known as Dumbarton Rock which is high and overlooks the Scottish town of Dumbarton.

History

Dumba ...

, and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia ( ang, Bernice, Bryneich, Beornice; la, Bernicia) was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was appr ...

. After the arrival of the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

in the late 8th century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established on the islands and along parts of the coasts. In the 9th century, the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpínid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from the advent of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed ...

combined the lands of the Scots and Picts to form a single kingdom which constituted the basis of the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

.

Scotland has an extensive coastline and vast areas of difficult terrain and poor agricultural land. In this period, more land became marginal due to climate change, resulting in relatively light human settlement, particularly in the interior and Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

* So ...

. Northern Britain lacked urban centres and settlements were based on farmsteads and around fortified positions such as broch

A broch is an Iron Age drystone hollow-walled structure found in Scotland. Brochs belong to the classification "complex Atlantic roundhouse" devised by Scottish archaeologists in the 1980s. Their origin is a matter of some controversy.

Origin ...

s, with mixed-farming primarily based on self-sufficiency. In this period, changes in settlement and colonisation meant that the Pictish and Brythonic languages

The Brittonic languages (also Brythonic or British Celtic; cy, ieithoedd Brythonaidd/Prydeinig; kw, yethow brythonek/predennek; br, yezhoù predenek) form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family; the other is Goidelic. ...

began to be subsumed by Gaelic, Scots, and, at the end of the period, by Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

. Life expectancy was relatively low, leading to a young population, with a ruling aristocracy, freemen, and relatively large numbers of slaves. Kingship was multi-layered, with different kings surrounded by their warbands that made up the most important elements of armed forces, and who engaged in both low-level raiding and occasional longer-range, major campaigns.

Some highly distinctive monumental and ornamental art, culminating in the development of the Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

style, are common across Britain and Ireland. The most impressive structures included nucleated hill forts and, after the introduction of Christianity, churches and monasteries. The period also saw the beginnings of Scottish literature

Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes works in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin, Norn or other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

The e ...

in British, Old English, Gaelic and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

languages.

Sources

As the first half of the period is largely

As the first half of the period is largely prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

, archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

plays an important part in studies of early Medieval Scotland. There are no significant contemporary internal sources for the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

, although evidence has been gleaned from lists of kings, annal

Annals ( la, annāles, from , "year") are a concise historical record in which events are arranged chronologically, year by year, although the term is also used loosely for any historical record.

Scope

The nature of the distinction between ann ...

s preserved in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in 2 ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

and from sources written down much later, which may draw on oral traditions or earlier sources. From the 7th century there is documentary evidence from Latin sources including the lives of saints, such as Adomnán

Adomnán or Adamnán of Iona (, la, Adamnanus, Adomnanus; 624 – 704), also known as Eunan ( ; from ), was an abbot of Iona Abbey ( 679–704), hagiographer, statesman, canon jurist, and saint. He was the author of the '' Life of Co ...

's ''Life of St. Columba'', and Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

's ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People

The ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' ( la, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum), written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict be ...

''. Archaeological sources include settlements, art, and surviving everyday objects.L. R. Laing, ''The Archaeology of Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. AD 400–1200'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), , pp. 14–15. Other aids to understanding in this period include onomastics (the study of names) – divided into toponymy

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

(place-names), showing the movement of languages, and the sequence in which different languages were spoken in an area, and anthroponymy

Anthroponymy (also anthroponymics or anthroponomastics, from Ancient Greek ἄνθρωπος ''anthrōpos'' / 'human', and ὄνομα ''onoma'' / 'name') is the study of ''anthroponyms'', the proper names of human beings, both individual and c ...

(personal names), which can offer clues to relationships and origins.

History

By the time of Bede and Adomnán, in the late seventh century and early eighth century, four major circles of influence had emerged in northern Britain. In the east were the Picts, whose kingdoms eventually stretched from the river Forth to Shetland. In the west were the Gaelic (Goidelic

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historicall ...

)-speaking people of Dál Riata with their royal fortress at Dunadd

Dunadd (Scottish Gaelic ''Dún Ad'', "fort on the iverAdd") is a hillfort in Argyll and Bute, Scotland, dating from the Iron Age and early medieval period and is believed to be the capital of the ancient kingdom of Dál Riata. Dal Riata was a kin ...

in Argyll, with close links with the island of Ireland, from which they brought with them the name "Scots", originally a term for the inhabitants of Ireland. In the south was the British ( Brythonic) Kingdom of Alt Clut

Dumbarton Castle ( gd, Dùn Breatainn, ; ) has the longest recorded history of any stronghold in Scotland. It sits on a volcanic plug of basalt known as Dumbarton Rock which is high and overlooks the Scottish town of Dumbarton.

History

Dumba ...

, descendants of the peoples of the Roman-influenced kingdoms of " The Old North". Finally, there were the English or "Angles", Germanic invaders who had overrun much of southern Britain and held the Kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia ( ang, Bernice, Bryneich, Beornice; la, Bernicia) was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was appr ...

(later the northern part of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

), in the south-east, and who brought with them Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

.

Picts

The confederation of Pictish tribes that developed north of the

The confederation of Pictish tribes that developed north of the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meanin ...

may have stretched up as far as Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) nort ...

. It probably developed out of the tribes of the Caledonii

The Caledonians (; la, Caledones or '; grc-gre, Καληδῶνες, ''Kalēdōnes'') or the Caledonian Confederacy were a Brittonic-speaking ( Celtic) tribal confederacy in what is now Scotland during the Iron Age and Roman eras.

The Gr ...

(whose name continued to be used for at least part of the confederation), perhaps as a response to the pressure exerted by the presence of the Romans to the south. They first appear in Roman records at the end of the 3rd century as the ''picti'' (the painted people: possibly a reference to their habit of tattooing their bodies) when Roman forces campaigned against them. The first identifiable king of the Picts, who seems to have exerted a superior and wide-ranging authority, was Bridei mac Maelchon (). His power was based in the kingdom of Fidach, and his base was at the fort of Craig Phadrig, near modern Inverness

Inverness (; from the gd, Inbhir Nis , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness"; sco, Innerness) is a city in the Scottish Highlands. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands. Histori ...

.J. Haywood, ''The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age'' (London: Pearson Education, 2004), , p. 116. After his death, leadership seems to have shifted to the Fortriu

Fortriu ( la, Verturiones; sga, *Foirtrinn; ang, Wærteras; xpi, *Uerteru) was a Pictish kingdom that existed between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is ...

, whose lands were centred on Moray

Moray () gd, Moireibh or ') is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland.

Between 1975 ...

and Easter Ross

Easter Ross ( gd, Ros an Ear) is a loosely defined area in the east of Ross, Highland, Scotland.

The name is used in the constituency name Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross, which is the name of both a British House of Commons constitue ...

and who raided along the eastern coast into modern England. Christian missionaries from Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though ther ...

appear to have begun the conversion of the Picts to Christianity from 563.

In the 7th century, the Picts acquired Bridei map Beli (671–693) as a king, perhaps imposed by the kingdom of Alt Clut, where his father Beli I and then his brother Eugein I ruled.A. P. Smyth, ''Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , pp. 63–4. At this point the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia was expanding northwards, and the Picts were probably tributary to them until, in 685, Bridei defeated them at the Battle of Dunnichen in Angus, killing their king, Ecgfrith. In the reign of Óengus mac Fergusa (729–761), the Picts appear to have reached the height of their influence, defeating the forces of Dál Riata (and probably making them a tributary), invading Alt Clut and Northumbria, and making the first known peace treaties with the English. Succeeding Pictish kings may have been able to dominate Dál Riata, with Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820) perhaps placing his son Domnall on the throne from 811.

Dál Riata

The Gaelic overkingdom of Dál Riata was on the western coast of modern Scotland, with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. It probably ruled from the fortress of Dunadd, now near Kilmartin in

The Gaelic overkingdom of Dál Riata was on the western coast of modern Scotland, with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. It probably ruled from the fortress of Dunadd, now near Kilmartin in Argyll and Bute

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020) ...

. In the late 6th and early 7th centuries, it encompassed roughly what is now Argyll and Bute and Lochaber

Lochaber ( ; gd, Loch Abar) is a name applied to a part of the Scottish Highlands. Historically, it was a provincial lordship consisting of the parishes of Kilmallie and Kilmonivaig, as they were before being reduced in extent by the creation ...

in Scotland, and also County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population of ...

in Ireland.M. Lynch, ed., ''Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press), , pp. 161–2. Dál Riata is commonly viewed as having been an Irish Gaelic colony in Scotland, although some archaeologists have recently argued against this. The inhabitants of Dál Riata are often referred to as Scots, from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''scotti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

'', a name used by Latin writers for the inhabitants of Ireland. Its original meaning is uncertain, but it later refers to Gaelic-speakers, whether from Ireland or elsewhere.

In 563, a mission from Ireland under St. Columba founded the monastery of Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though ther ...

off the west coast of Scotland, and probably began the conversion of the region to Christianity.A. P. Smyth, ''Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , pp. 43–6. The kingdom reached its height under Áedán mac Gabráin

Áedán mac Gabráin (pronounced in Old Irish; ga, Aodhán mac Gabhráin, lang), also written as Aedan, was a king of Dál Riata from 574 until c. 609 AD. The kingdom of Dál Riata was situated in modern Argyll and Bute, Scotland, and par ...

(r. 574–608), but its expansion was checked at the Battle of Degsastan

The Battle of Degsastan was fought around 603 between king Æthelfrith of Bernicia and the Gaels under Áedán mac Gabráin, king of Dál Riada. Æthelfrith's smaller army won a decisive victory, although his brother Theodbald was killed. Very ...

in 603 by Æthelfrith of Northumbria

Æthelfrith (died c. 616) was King of Bernicia from c. 593 until his death. Around 604 he became the first Bernician king to also rule the neighboring land of Deira, giving him an important place in the development of the later kingdom of North ...

. Serious defeats in Ireland and Scotland in the time of Domnall Brecc

Domnall Brecc (Welsh: ''Dyfnwal Frych''; English: ''Donald the Freckled'') (died 642 in Strathcarron) was king of Dál Riata, in modern Scotland, from about 629 until 642. He was the son of Eochaid Buide. He was counted as Donald II of Scotland b ...

(d. 642) ended Dál Riata's golden age, and the kingdom became a client of Northumbria, then a subject to the Picts. There is disagreement over the fate of the kingdom from the late 8th century onwards. Some scholars argue that Dál Riata underwent a revival under king Áed Find (736–78), before the arrival of the Vikings.

Alt Clut

''Alt Clut'' (named after the Brythonic name for Dumbarton Rock, the Medieval capital of the

''Alt Clut'' (named after the Brythonic name for Dumbarton Rock, the Medieval capital of the Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Gaelic, meaning "strath (valley) of the River Clyde") was one of nine former local government regions of Scotland created in 1975 by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 and abolished in 1996 by the Local Government et ...

region) may have had its origins with the Damnonii

The Damnonii (also referred to as Damnii) were a Brittonic people of the late 2nd century who lived in what became the Kingdom of Strathclyde by the Early Middle Ages, and is now southern Scotland. They are mentioned briefly in Ptolemy's ''Ge ...

people of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's ''Geographia

The ''Geography'' ( grc-gre, Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις, ''Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis'', "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the ' and the ', is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, com ...

''. Two kings are known from near-contemporary sources in this early period. The first is Coroticus or Ceretic (Ceredig), known as the recipient of a letter from Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, Pádraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

, and stated by a 7th-century biographer to have been king of the Height of the Clyde, Dumbarton Rock, placing him in the second half of the 5th century. From Patrick's letter it is clear that Ceretic was a Christian, and it is likely that the ruling class of the area were also Christians, at least in name.A. Macquarrie, "The kings of Strathclyde, c. 400–1018", in G. W. S. Barrow, A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, ''Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), , p. 2. His descendant Rhydderch Hael

Rhydderch Hael ( en, Rhydderch the Generous), Riderch I of Alt Clut, or Rhydderch of Strathclyde, ( ''fl.'' 580 – c. 614) was a ruler of Alt Clut, a Brittonic kingdom in the ''Hen Ogledd'' or "Old North" of Britain. He was one of the most famo ...

is named in Adomnán

Adomnán or Adamnán of Iona (, la, Adamnanus, Adomnanus; 624 – 704), also known as Eunan ( ; from ), was an abbot of Iona Abbey ( 679–704), hagiographer, statesman, canon jurist, and saint. He was the author of the '' Life of Co ...

's ''Life of Saint Columba''.

After 600, information on the Britons of Alt Clut becomes more common in the sources. In 642, led by Eugein son of Beli, they defeated the men of Dál Riata and killed Domnall Brecc

Domnall Brecc (Welsh: ''Dyfnwal Frych''; English: ''Donald the Freckled'') (died 642 in Strathcarron) was king of Dál Riata, in modern Scotland, from about 629 until 642. He was the son of Eochaid Buide. He was counted as Donald II of Scotland b ...

, grandson of Áedán, at Strathcarron. The kingdom suffered a number of attacks from the Picts under Óengus, and later the Picts' Northumbrian allies between 744 and 756. They lost the region of Kyle in the southwest of modern Scotland to Northumbria, and the last attack may have forced the king Dumnagual III to submit to his neighbours. After this, little is heard of Alt Clut or its kings until Alt Clut was burnt and probably destroyed in 780, although by whom and what in what circumstances is not known, Historians have traditionally identified Alt Clut with the later Kingdom of Strathclyde, but J. E. Fraser points to the fact there is no contemporary evidence that the heartland of Alt Clut was in Clydesdale Clydesdale is an archaic name for Lanarkshire, a traditional county in Scotland. The name may also refer to:

Sports

* Clydesdale F.C., a former football club in Glasgow

* Clydesdale RFC, Glasgow, a former rugby union club

* Clydesdale RFC, Sout ...

and the Kingdom of Strathclyde may have arisen after Alt Clut's decline.

Bernicia

The Brythonic successor states of what is now the modern Anglo-Scottish border region are referred to by Welsh scholars as part of ''Yr

The Brythonic successor states of what is now the modern Anglo-Scottish border region are referred to by Welsh scholars as part of ''Yr Hen Ogledd

Yr Hen Ogledd (), in English the Old North, is the historical region which is now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands that was inhabited by the Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its population spo ...

'' ("The Old North"). This included the kingdoms of Bryneich, which may have had its capital at modern Bamburgh

Bamburgh ( ) is a village and civil parish on the coast of Northumberland, England. It had a population of 454 in 2001, decreasing to 414 at the 2011 census.

The village is notable for the nearby Bamburgh Castle, a castle which was the seat of ...

in Northumberland, and Gododdin

The Gododdin () were a Brittonic people of north-eastern Britannia, the area known as the Hen Ogledd or Old North (modern south-east Scotland and north-east England), in the sub-Roman period. Descendants of the Votadini, they are best known a ...

, centred on Din Eidyn

Eidyn was the region around modern Edinburgh in Britain's sub-Roman and early medieval periods, approximately the 5th–7th centuries. It centred on the stronghold of Din Eidyn, thought to have been at Castle Rock, now the site of Edinburgh Cas ...

(what is now Edinburgh) and stretching across modern Lothian

Lothian (; sco, Lowden, Loudan, -en, -o(u)n; gd, Lodainn ) is a region of the Scottish Lowlands, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills and the Moorfoot Hills. The principal settlement is the Scot ...

. Some "Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ' ...

" may have been employed as mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

along Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall ( la, Vallum Aelium), also known as the Roman Wall, Picts' Wall, or ''Vallum Hadriani'' in Latin, is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian. ...

during the late Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

period. Others are thought to have migrated north (by sea) from Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/Cumbric: ''Deywr'' or ''Deifr''; ang, Derenrice or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic *''daru ...

( ang, Derenrice or ''Dere'') in the early 6th century. At some point the Angles took control of Bryneich, which became the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia ( ang, Beornice). The first Anglo-Saxon king in the historical record is Ida, who is said to have obtained the throne around 547. Around 600, the Gododdin raised a force of about 300 men to assault the Anglo-Saxon stronghold of Catraeth, perhaps Catterick, North Yorkshire. The battle, which ended disastrously for the Britons, was memorialised in the poem ''Y Gododdin

''Y Gododdin'' () is a medieval Welsh poem consisting of a series of elegies to the men of the Brittonic kingdom of Gododdin and its allies who, according to the conventional interpretation, died fighting the Angles of Deira and Bernicia at ...

''.

Ida's grandson, Æthelfrith

Æthelfrith (died c. 616) was King of Bernicia from c. 593 until his death. Around 604 he became the first Bernician king to also rule the neighboring land of Deira, giving him an important place in the development of the later kingdom of North ...

, united Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/Cumbric: ''Deywr'' or ''Deifr''; ang, Derenrice or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic *''daru ...

with his own kingdom, killing its king Æthelric to form Northumbria around 604. Ætherlric's son returned to rule both kingdoms after Æthelfrith had been defeated and killed by the East Anglians in 616, presumably bringing with him the Christianity to which he had converted while in exile. After his defeat and death at the hands of the Welsh and Mercians at the Battle of Hatfield Chase

The Battle of Hatfield Chase ( ang, Hæðfeld; owl, Meigen) was fought on 12 October 633 at Hatfield Chase near Doncaster (today part of South Yorkshire, England). It pitted the Northumbrians against an alliance of Gwynedd and Mercia. The Nor ...

on 12 October 633, Northumbria again was divided into two kingdoms under pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. In ...

kings. Oswald Oswald may refer to:

People

*Oswald (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Oswald (surname), including a list of people with the name

Fictional characters

*Oswald the Reeve, who tells a tale in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''The Canterbu ...

(r. 634–42), (another son of Æthelfrith) defeated the Welsh and appears to have been recognised by both Bernicians and Deirans as king of a united Northumbria. He had converted to Christianity while in exile in Dál Riata and looked to Iona for missionaries, rather than to Canterbury. The island monastery of Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important ...

was founded in 635 by the Irish monk Saint Aidan

Aidan of Lindisfarne ( ga, Naomh Aodhán; died 31 August 651) was an Irish monk and missionary credited with converting the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity in Northumbria. He founded a monastic cathedral on the island of Lindisfarne, known as Li ...

, who had been sent from Iona at the request of King Oswald. It became the seat of the Bishop of Lindisfarne, which stretched across Northumbria. In 638 Edinburgh was attacked by the English and at this point, or soon after, the Gododdin territories in Lothian and around Stirling came under the rule of Bernicia.A. P. Smyth, ''Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , p. 31. After Oswald's death fighting the Mercians, the two kingdoms were divided again, with Deira possibly having sub-kings under Bernician authority, but from this point the English kings were Christian and after the Synod of Whitby

In the Synod of Whitby in 664, King Oswiu of Northumbria ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Rome rather than the customs practiced by Irish monks at Iona and its satellite ins ...

in 664, the Northumbrian kings accepted the primacy of Canterbury and Rome. In the late 7th century, the Northumbrians extended their influence north of the Forth, until they were defeated by the Picts at the Battle of Nechtansmere in 685.

Vikings and the Kingdom of Alba

The balance between rival kingdoms was transformed in 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain. Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. The king of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the king of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, were among the dead after a major defeat by the Vikings in 839. A mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement into south-west Scotland produced the Gall-Gaidel, the ''Norse Irish'', from which the region gets the modern name

The balance between rival kingdoms was transformed in 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain. Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. The king of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the king of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, were among the dead after a major defeat by the Vikings in 839. A mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement into south-west Scotland produced the Gall-Gaidel, the ''Norse Irish'', from which the region gets the modern name Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

. Sometime in the 9th century, the beleaguered kingdom of Dál Riata lost the Hebrides to the Vikings, when Ketil Flatnose is said to have founded the Kingdom of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles consisted of the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Firth of Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the , or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the or Nor ...

. These threats may have speeded a long-term process of gaelicisation of the Pictish kingdoms, which adopted Gaelic language and customs. There was also a merger of the Gaelic and Pictish crowns, although historians debate whether it was a Pictish takeover of Dál Riata, or the other way around. This culminated in the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, which brought to power the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpínid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from the advent of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed ...

, who became the leaders of a combined Gaelic-Pictish kingdom.B. Yorke, ''The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800'' (Pearson Education, 2006), , p. 54. In 867 the Vikings seized Northumbria, forming the Kingdom of York

Scandinavian York ( non, Jórvík) Viking Yorkshire or Norwegian York is a term used by historians for the south of Northumbria (modern-day Yorkshire) during the period of the late 9th century and first half of the 10th century, when it was do ...

;D. W. Rollason, ''Northumbria, 500–1100: Creation and Destruction of a Kingdom'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), , p. 212. three years later they stormed the Briton fortress of Dumbarton and subsequently conquered much of England except for a reduced Kingdom of Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, leaving the new combined Pictish and Gaelic kingdom almost encircled.

The immediate descendants of Cináed were styled either as ''King of the Picts'' or ''King of Fortriu

Fortriu ( la, Verturiones; sga, *Foirtrinn; ang, Wærteras; xpi, *Uerteru) was a Pictish kingdom that existed between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is ...

''. They were ousted in 878 when Áed mac Cináeda

Áed mac Cináeda ( Modern Scottish Gaelic: ''Aodh mac Choinnich''; ; Anglicized: Hugh; died 878) was a son of Cináed mac Ailpín. He became king of the Picts in 877, when he succeeded his brother Constantín mac Cináeda. He was nicknamed Á ...

was killed by Giric mac Dúngail, but returned again on Giric's death in 889. When Cínaed's eventual successor Domnall mac Causantín died at Dunnottar in 900, he was the first man to be recorded as ''rí Alban'' (i.e. ''King of Alba''). Such an apparent innovation in the Gaelic chronicles is occasionally taken to spell the birth of Scotland, but there is nothing extant from or about his reign that might confirm this. Known in Gaelic as "Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingdom ...

", in Latin as "Scotia

Scotia is a Latin placename derived from ''Scoti'', a Latin name for the Gaels, first attested in the late 3rd century.Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 The Romans referred to Ireland as "Scotia" around ...

", and in English as "Scotland", his kingdom was the nucleus from which the Scottish kingdom would expand as the Viking influence waned, just as in the south the Kingdom of Wessex expanded to become the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 12 ...

.

Geography

Physical geography

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it has roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles. Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 metres above sea level. Its east Atlantic position means that it experiences heavy rainfall, especially in the west. This encouraged the spread of blanket

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it has roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles. Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 metres above sea level. Its east Atlantic position means that it experiences heavy rainfall, especially in the west. This encouraged the spread of blanket peat bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

, the acidity of which, combined with high level of wind and salt spray, made most of the islands treeless. The existence of hills, mountains, quicksands and marshes made internal communication and conquest extremely difficult and may have contributed to the fragmented nature of political power. The early Middle Ages was a period of climate deterioration, with a drop in temperature and an increase in rainfall, resulting in more land becoming unproductive.

Settlement

Roman influence beyond Hadrian's Wall does not appear to have had a major impact on settlement patterns, withIron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ap ...

hill fort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Rom ...

s and promontory forts continuing to be occupied through the early Medieval period. These often had defences of dry stone or timber laced walls, sometimes with a palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a fence or defensive wall made from iron or wooden stakes, or tree trunks, and used as a defensive structure or enclosure. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymology

''Palisade'' ...

.K. J. Edwards and I. Ralston, ''Scotland after the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC — AD 1000'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), , pp. 224–5. The large numbers of these forts has been taken to suggest peripatetic monarchies and aristocracies, moving around their domains to control and administer them. In the Northern and Western Isles the sites of Iron Age Brochs and wheel houses continued to be occupied, but were gradually replaced with less imposing cellular houses. There are a handful of major timber halls in the south, comparable to those excavated in Anglo-Saxon England and dated to the 7th century. In the areas of Scandinavian settlement in the islands and along the coast a lack of timber meant that native materials had to be adopted for house building, often combining layers of stone with turf.

Place-name evidence, particularly the use of the prefix "pit", meaning land or a field, suggests that the heaviest areas of Pictish settlement were in modern Fife, Perthshire

Perthshire (locally: ; gd, Siorrachd Pheairt), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, ...

, Angus

Angus may refer to:

Media

* ''Angus'' (film), a 1995 film

* ''Angus Og'' (comics), in the ''Daily Record''

Places Australia

* Angus, New South Wales

Canada

* Angus, Ontario, a community in Essa, Ontario

* East Angus, Quebec

Scotland

* An ...

, Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

and around the Moray Firth

The Moray Firth (; Scottish Gaelic: ''An Cuan Moireach'', ''Linne Mhoireibh'' or ''Caolas Mhoireibh'') is a roughly triangular inlet (or firth) of the North Sea, north and east of Inverness, which is in the Highland council area of north of ...

, although later Gaelic migration may have erased some Pictish names from the record. Early Gaelic settlement appears to have been in the regions of the western mainland of Scotland between Cowal

Cowal ( gd, Còmhghall) is a peninsula in Argyll and Bute, in the west of Scotland, that extends into the Firth of Clyde.

The northern part of the peninsula is covered by the Argyll Forest Park managed by Forestry and Land Scotland. The Arroch ...

and Ardnamurchan, and the adjacent islands, later extending up the West coast in the 8th century.B. Yorke, ''The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800'' (Pearson Education, 2006), , p. 53. There is place name and archaeological evidence of Anglian settlement in south-east Scotland reaching into West Lothian

West Lothian ( sco, Wast Lowden; gd, Lodainn an Iar) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, and was one of its historic counties. The county was called Linlithgowshire until 1925. The historic county was bounded geographically by the Av ...

, and to a lesser extent into south-western Scotland. Later Norse settlement was probably most extensive in Orkney and Shetland, with lighter settlement in the western islands, particularly the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebr ...

and on the mainland in Caithness, stretching along fertile river valleys through Sutherland

Sutherland ( gd, Cataibh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in the Highlands of Scotland. Its county town is Dornoch. Sutherland borders Caithness and Moray Firth to the east, Ross-shire and Cromartyshire (later c ...

and into Ross Ross or ROSS may refer to:

People

* Clan Ross, a Highland Scottish clan

* Ross (name), including a list of people with the surname or given name Ross, as well as the meaning

* Earl of Ross, a peerage of Scotland

Places

* RoSS, the Republic of Sout ...

. There was also extensive Viking settlement in Bernicia, the Northern part of Northumbria, which stretched into the modern Borders

A border is a geographical boundary.

Border, borders, The Border or The Borders may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Film and television

* ''Border'' (1997 film), an Indian Hindi-language war film

* ''Border'' (2018 Swedish film), ...

and Lowlands

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of p ...

.

Language

This period saw dramatic changes in the geography of language. Modern linguists divide the Celtic languages into two major groups, the

This period saw dramatic changes in the geography of language. Modern linguists divide the Celtic languages into two major groups, the P-Celtic

The Gallo-Brittonic languages, also known as the P-Celtic languages, are a subdivision of the Celtic languages of Ancient Gaul (both '' celtica'' and '' belgica'') and Celtic Britain, which share certain features. Besides common linguistic in ...

, from which Welsh, Breton and Cornish derive and the Q-Celtic

The Celtic languages ( usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

, from which comes Irish, Manx and Gaelic. The Pictish language remains enigmatic, since the Picts had no written script of their own and all that survives are place names and some isolated inscriptions in Irish ogham

Ogham (Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langua ...

script. Most modern linguists accept that, although the nature and unity of Pictish language is unclear, it belonged to the former group. Historical sources, as well as place-name evidence, indicate the ways in which the Pictish language in the north and Cumbric languages in the south were overlaid and replaced by Gaelic, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and later Norse in this period.

Economy

Lacking the urban centres created under the Romans in the rest of Britain, the economy of Scotland in the early Middle Ages was overwhelmingly agricultural. Without significant transport links and wider markets, most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by

Lacking the urban centres created under the Romans in the rest of Britain, the economy of Scotland in the early Middle Ages was overwhelmingly agricultural. Without significant transport links and wider markets, most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by hunter-gather

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

ing. Limited archaeological evidence indicates that throughout Northern Britain farming was based around a single homestead or a small cluster of three or four homes, each probably containing a nuclear family, with relationships likely to be common among neighbouring houses and settlements, reflecting the partition of land through inheritance.A. Woolf, ''From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 17–20. Farming became based around a system that distinguished between the infield around the settlement, where crops were grown every year and the outfield, further away and where crops were grown and then left fallow in different years, in a system that would continue until the 18th century. The evidence of bones indicates that cattle were by far the most important domesticated animal, followed by pigs, sheep and goats, while domesticated fowl were rare. Imported goods found in archaeological sites of the period include ceramics and glass, while many sites indicate iron and precious metal working.

Demography

There are almost no written sources from which to re-construct the demography of early Medieval Scotland. Estimates have been made of a population of 10,000 inhabitants in Dál Riata and 80–100,000 for Pictland.L. R. Laing, ''The Archaeology of Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. AD 400–1200'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), , pp. 21–2. It is likely that the 5th and 6th centuries saw higher mortality rates due to the appearance of bubonic plague, which may have reduced net population.P. Fouracre and R. McKitterick, eds, ''The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 500-c. 700'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), , p. 234. The known conditions have been taken to suggest it was a high fertility, high mortality society, similar to many developing countries in the modern world, with a relatively young demographic profile, and perhaps early childbearing, and large numbers of children for women. This would have meant that there were a relatively small proportion of available workers to the number of mouths to feed. This would have made it difficult to produce a surplus that would allow demographic growth and more complex societies to develop.Society

The primary unit of social organisation in Germanic and Celtic Europe was the kin group.C. Haigh, ''The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), , pp. 82–4. The mention of descent through the female line in the ruling families of the Picts in later sources and the recurrence of leaders clearly from outside of Pictish society, has led to the conclusion that their system of descent was

The primary unit of social organisation in Germanic and Celtic Europe was the kin group.C. Haigh, ''The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), , pp. 82–4. The mention of descent through the female line in the ruling families of the Picts in later sources and the recurrence of leaders clearly from outside of Pictish society, has led to the conclusion that their system of descent was matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance o ...

. However, this has been challenged by a number of historians who argue that the clear evidence of awareness of descent through the male line suggests that this more likely to indicate a bilateral

Bilateral may refer to any concept including two sides, in particular:

*Bilateria, bilateral animals

*Bilateralism, the political and cultural relations between two states

*Bilateral, occurring on both sides of an organism ( Anatomical terms of l ...

system of descent, where descent was counted through both male and female lines.A. P. Smyth, ''Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , pp. 57–8.

Scattered evidence, including the records in Irish annals and the images of warriors like those depicted on the Pictish stone slabs at Aberlemno, Forfarshire

Angus ( sco, Angus; gd, Aonghas) is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland, a registration county and a lieutenancy area. The council area borders Aberdeenshire, Dundee City and Perth and Kinross. Main industries include agr ...

and Hilton of Cadboll

Hilton of Cadboll, or simply Hilton, ( gd, Baile a' Chnuic) is a village about southeast of Tain in Easter Ross, in the Scottish council area of Highland. It is famous for the Hilton of Cadboll Stone.

Hilton of Cadboll, Balintore, and Shandwi ...

in Easter Ross, suggest that in Northern Britain, as in Anglo-Saxon England, society was dominated by a military aristocracy, whose status was dependent in a large part on their ability and willingness to fight. Below the level of the aristocracy it is assumed that there were non-noble freemen, working their own small farms or holding lands as free tenants. There are no surviving law codes from Scotland in this period,D. E. Thornton, "Communities and kinship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 98. but codes in Ireland and Wales indicate that freemen had the right to bear arms, represent themselves in law and to receive compensation for murdered kinsmen.

Indications are that society in North Britain contained relatively large numbers of slaves, often taken in war and raids, or bought, as St. Patrick indicated the Picts were doing from the Britons in Southern Scotland. Slavery probably reached relatively far down in society, with most rural households containing some slaves. Because they were taken relatively young and were usually racially indistinguishable from their masters, many slaves would have been more integrated into their societies of capture than their societies of origin, in terms of both culture and language. Living and working beside their owners they in practice may have become members of a household without the inconvenience of the partible inheritance rights that divided estates. Where there is better evidence from England and elsewhere, it was common for such slaves who survived to middle age to gain their freedom, with such freedmen often remaining clients of the families of their former masters.

Kingship

In the early Medieval period, British kingship was not inherited in a direct line from previous kings, as would be the case in the late Middle Ages. There were instead a number of candidates for kingship, who usually needed to be a member of a particular dynasty and to claim descent from a particular ancestor. Kingship could be multi-layered and very fluid. The Pictish kings of Fortriu were probably acting as overlords of other Pictish kings for much of this period and occasionally were able to assert an overlordship over non-Pictish kings, but occasionally themselves had to acknowledge the overlordship of external rulers, both Anglian and British. Such relationships may have placed obligations to pay tribute or to supply armed forces. After a victory, sub-kings may have received rewards in return for this service. Interaction with and intermarriage into the ruling families of subject kingdoms may have opened the way to absorption of such sub-kingdoms and, although there might be later overturnings of these mergers, it is likely that a complex process by which kingship was gradually monopolised by a handful of the most powerful dynasties was taking place.B. Yorke, "Kings and kingship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 76–90.

The primary role of the king was to act as a war leader, reflected in the very small number of minority or female reigning monarchs in the period. Kings organised the defence of their people's lands, property and persons and negotiated with other kings to secure these things. If they failed to do so, the settlements might be raided, destroyed or annexed, and the populations killed or taken into slavery. Kings also engaged in the low-level warfare of raiding and the more ambitious full-scale warfare that led to conflicts of large armies and alliances, and which could be undertaken over relatively large distances, such as the expedition to Orkney by Dál Riata in 581 or the Northumbrian attack on Ireland in 684.

Kingship had its ritual aspects. The kings of Dál Riata were inaugurated by putting their foot in a footprint carved in stone, signifying that they would follow in the footsteps of their predecessors.J. Haywood, ''The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age'' (London: Pearson Education, 2004), , p. 125. The kingship of the unified kingdom of Alba had

In the early Medieval period, British kingship was not inherited in a direct line from previous kings, as would be the case in the late Middle Ages. There were instead a number of candidates for kingship, who usually needed to be a member of a particular dynasty and to claim descent from a particular ancestor. Kingship could be multi-layered and very fluid. The Pictish kings of Fortriu were probably acting as overlords of other Pictish kings for much of this period and occasionally were able to assert an overlordship over non-Pictish kings, but occasionally themselves had to acknowledge the overlordship of external rulers, both Anglian and British. Such relationships may have placed obligations to pay tribute or to supply armed forces. After a victory, sub-kings may have received rewards in return for this service. Interaction with and intermarriage into the ruling families of subject kingdoms may have opened the way to absorption of such sub-kingdoms and, although there might be later overturnings of these mergers, it is likely that a complex process by which kingship was gradually monopolised by a handful of the most powerful dynasties was taking place.B. Yorke, "Kings and kingship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 76–90.

The primary role of the king was to act as a war leader, reflected in the very small number of minority or female reigning monarchs in the period. Kings organised the defence of their people's lands, property and persons and negotiated with other kings to secure these things. If they failed to do so, the settlements might be raided, destroyed or annexed, and the populations killed or taken into slavery. Kings also engaged in the low-level warfare of raiding and the more ambitious full-scale warfare that led to conflicts of large armies and alliances, and which could be undertaken over relatively large distances, such as the expedition to Orkney by Dál Riata in 581 or the Northumbrian attack on Ireland in 684.

Kingship had its ritual aspects. The kings of Dál Riata were inaugurated by putting their foot in a footprint carved in stone, signifying that they would follow in the footsteps of their predecessors.J. Haywood, ''The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age'' (London: Pearson Education, 2004), , p. 125. The kingship of the unified kingdom of Alba had Scone

A scone is a baked good, usually made of either wheat or oatmeal with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often slightly sweetened and occasionally glazed with egg wash. The scone is a basic component of t ...

and its sacred stone at the heart of its coronation ceremony, which historians presume was inherited from Pictish practices. Iona, the early centre of Scottish Christianity, became the burial site of the early kings of Scotland until the eleventh century, when the House of Canmore adopted Dunfermline

Dunfermline (; sco, Dunfaurlin, gd, Dùn Phàrlain) is a city, parish and former Royal Burgh, in Fife, Scotland, on high ground from the northern shore of the Firth of Forth. The city currently has an estimated population of 58,508. Acco ...

, closer to Scone.

Warfare

At the most basic level, a king's power rested on the existence of his bodyguard or war-band. In the British language, this was called the ''teulu'', as in ''teulu Dewr'' (the "War-band of Deira"). In Latin the word is either ''comitatus'' or ''tutores'', or even ''familia''; ''tutores'' is the most common word in this period, and derives for the Latin verb ''tueor'', meaning "defend, preserve from danger". The war-band functioned as an extension of the ruler's legal person, and was the core of the larger armies that were mobilised from time to time for campaigns of significant size. In peacetime, the war-band's activity was centred on the "Great Hall". Here, in both Germanic and Celtic cultures, the feasting, drinking and other forms of male bonding that kept up the war-band's integrity would take place. In the epic poem

At the most basic level, a king's power rested on the existence of his bodyguard or war-band. In the British language, this was called the ''teulu'', as in ''teulu Dewr'' (the "War-band of Deira"). In Latin the word is either ''comitatus'' or ''tutores'', or even ''familia''; ''tutores'' is the most common word in this period, and derives for the Latin verb ''tueor'', meaning "defend, preserve from danger". The war-band functioned as an extension of the ruler's legal person, and was the core of the larger armies that were mobilised from time to time for campaigns of significant size. In peacetime, the war-band's activity was centred on the "Great Hall". Here, in both Germanic and Celtic cultures, the feasting, drinking and other forms of male bonding that kept up the war-band's integrity would take place. In the epic poem Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The ...