divestment from South Africa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Disinvestment (or

"The Anti-Apartheid Movement, Britain and South Africa: Anti-Apartheid Protest vs Real Politik"

, Ph.D. Dissertation, 15 September 2000 Following this passage of this resolution the UK-based

i

Harvard Honors Nelson Mandela

. Adam A. Sofen and Alan E. Wirzbicki. Adam Soften and Alan Wirzbicki give this description:

In addition to campuses, anti-apartheid activists found concerned and sympathetic legislators in cities and states. Several states and localities did pass legislation ordering the sale of such securities, notably the City and County of

In addition to campuses, anti-apartheid activists found concerned and sympathetic legislators in cities and states. Several states and localities did pass legislation ordering the sale of such securities, notably the City and County of

While post-colonial African countries had already imposed sanctions on South Africa in solidarity with the

While post-colonial African countries had already imposed sanctions on South Africa in solidarity with the

"For U.S. Firms in South Africa, The Threat of Coercive Sullivan Principles"

"On 'Constructive Engagement' in South Africa"

''The MIT Tech''. 105(47). 5 November 1985.

"The Choice for U.S. Policy in South Africa: Reform or Vengeance"

"Misconceptions about U.S. policy toward South Africa"

US Department of State Bulletin. September 1986. * Richard Knight

''Sanctioning Apartheid'' (Africa World Press). 1990.

"Disinvestment from South Africa: They Did Well by Doing Good"

''

African Activist Archive

– more than 7,000 documents, posters, T-shirts, buttons, photos, video, and memories of activism in the U.S. to support the struggles of African peoples against apartheid, colonialism, and social injustice, 1950s–1990s. Also includes a directory of African activist organizations across the U.S.

* ttp://richardknight.homestead.com/files/useconomicinv.htm U.S. Economic Involvement with Apartheid South Africa

An Analysis of U.S. Disinvestment from South Africa: Unity, Rights, and Justice

Black South African Opinion on Disinvestment

The Crusade Against South Africa

* [http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0002vwd4 Image of UCLA students in sit-down protest with banner reading "UC Out of South Africa! Divest Now" as two UC Police officers watch Los Angeles, California, 1986.] Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles. {{DEFAULTSORT:Disinvestment From South Africa Boycotts of apartheid South Africa International sanctions South Africa–United States relations Economy of South Africa Disinvestment Library of Congress Africa Collection related Foreign trade of South Africa Investment in South Africa

divestment

In finance and economics, divestment or divestiture is the reduction of some kind of asset for financial, ethical, or political objectives or sale of an existing business by a firm. A divestment is the opposite of an investment. Divestiture is ...

) from South Africa was first advocated in the 1960s, in protest against South Africa's system of apartheid, but was not implemented on a significant scale until the mid-1980s. The disinvestment

Disinvestment refers to the use of a concerted economic boycott to pressure a government, industry, or company towards a change in policy, or in the case of governments, even regime change. The term was first used in the 1980s, most commonly in ...

campaign, after being realised in federal legislation enacted in 1986 by the United States, is credited by some as pressuring the South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

n Government to embark on negotiations

Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more people or parties to reach the desired outcome regarding one or more issues of conflict. It is an interaction between entities who aspire to agree on matters of mutual interest. The agreement ...

ultimately leading to the dismantling of the apartheid system.

United Nations campaigns

In November 1962, theUnited Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

passed Resolution 1761, a non-binding resolution establishing the United Nations Special Committee against Apartheid

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1761 was passed on 6 November 1962 in response to the racist policies of apartheid established by the South African Government.

Condemnation of apartheid

The resolution deemed apartheid and the polici ...

and called for imposing economic and other sanctions on South Africa. All Western nations were unhappy with the call for sanctions and as a result, boycotted the committee.Arianna Lisson"The Anti-Apartheid Movement, Britain and South Africa: Anti-Apartheid Protest vs Real Politik"

, Ph.D. Dissertation, 15 September 2000 Following this passage of this resolution the UK-based

Anti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-White population who were persecuted by the policie ...

(AAM) spearheaded the arrangements for an international conference on sanctions to be held in London in April 1964. According to Arianna Lisson, "The aim of the Conference was to work out the practicability of economic sanctions and their implications on the economies of South Africa, the UK, the US, and the Protectorates. Knowing that the strongest opposition to the application of sanctions came from the West (and within the West, Britain), the Committee made every effort to attract as wide and varied a number of speakers and participants as possible so that the Conference findings would be regarded as objective."

The conference was named the ''International Conference for Economic Sanctions Against South Africa''. This conference, Lisson writes,

established the necessity, the legality, and the practicability of internationally organised sanctions against South Africa, whose policies were seen to have become a direct threat to peace and security in Africa and the world. Its findings also pointed out that in order to be effective, a programme of sanctions would need the active participation of Britain and the US, who were also the main obstacle to the implementation of such a policy.

Attempts to persuade British policymakers

The conference was not successful in persuading Britain to take up economic sanctions against South Africa though. Rather, the British government "remained firm in its view that the imposition of sanctions would be unconstitutional 'because we do not accept that this situation in South Africa constitutes a threat to international peace and security and we do not, in any case, believe that sanctions would have the effect of persuading the South African Government to change its policies". The AAM tried to make sanctions an election issue in the 1964 General Election in Britain. Candidates were asked to state their position on economic sanctions and other punitive measures against the South African government. Most candidates who responded answered in the affirmative. After the Labour Party sweep to power though, commitment to the anti-apartheid cause dissipated. In short order, Labour Party leaderHarold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

told the press that his Labour Party was "not in favour of trade sanctions partly because, even if fully effective, they would harm the people we are most concerned about – the Africans and those white South Africans who are having to maintain some standard of decency there". Even so, Lisson writes that the "AAM still hoped that the new Labour Government would be more sensitive to the demands of public opinion than the previous Government." But by the end of 1964, it was clear that the election of the Labour Party had made little difference in the government's overall unwillingness to impose sanctions.

Steadfast rejection by the United Kingdom

Lisson summarizes the situation at the UN in 1964:At the UN, Britain consistently refused to accept that the situation in South Africa fell under Chapter VII of the nited NationsCharter. Instead, in collaboration with the US, it worked for a carefully worded appeal on the Rivonia and other political trials to try to appease Afro-Asian countries and public opinion at home and abroad; by early 1965 the issue of sanctions had lost momentum.According to Lisson, Britain's rejection was premised on its economic interests in South Africa, which would be put at risk if any type of meaningful economic sanctions were put in place.

1970s

In 1977, the voluntary UN arms embargo became mandatory with the passing ofUnited Nations Security Council Resolution 418

United Nations Security Council Resolution 418, adopted unanimously on 4 November 1977, imposed a mandatory arms embargo against South Africa. This resolution differed from the earlier Resolution 282, which was only voluntary. The embargo was ...

.

An oil embargo was introduced on 20 November 1987 when the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

adopted a voluntary international oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they m ...

.

United States campaign (1977–1989)

The Sullivan Principles (1977)

Richard Knight writes that the anti-apartheid movement in the U.S. found that Washington was unwilling to get involved in economically isolating South Africa. The movement responded by organized lobbying of individual businesses and institutional investors to end their involvement with or investments in the apartheid state as a matter ofcorporate social responsibility

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a form of international private business self-regulation which aims to contribute to societal goals of a philanthropic, activist, or charitable nature by engaging in or supporting volunteering or ethicall ...

. This campaign was coordinated by several faith-based institutional investors eventually leading to the creation of the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility The Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (ICCR) is an association advocating for corporate social responsibility. Its 300 member organizations comprise faith communities, asset managers, unions, pensions, NGOs and other investors. ICCR memb ...

. An array of celebrities, including singer Paul Simon

Paul Frederic Simon (born October 13, 1941) is an American musician, singer, songwriter and actor whose career has spanned six decades. He is one of the most acclaimed songwriters in popular music, both as a solo artist and as half of folk roc ...

, also participated.

The key instrument of this campaign was the so-called Sullivan Principles, authored by and named after the Rev. Dr. Leon Sullivan

Leon Howard Sullivan (October 16, 1922 – April 24, 2001) was a Baptist minister, a civil rights leader and social activist focusing on the creation of job training opportunities for African Americans, a longtime General Motors Board Member, an ...

. Leon Sullivan was an African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

preacher in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

who, in 1977, was also a board member of the corporate giant General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

. At that time, General Motors was the largest employer of Blacks in South Africa. The principles required that the corporation ensure that all employees are treated equally and in an integrated environment, both in and outside the workplace, regardless of race, as a condition of doing business. These principles directly conflicted with the mandated racial discrimination and segregation policies of apartheid-era South Africa, thus making it impossible for businesses adopting the Sullivan Principles to continue doing business there.

While the anti-Apartheid movement lobbied individual businesses to adopt and comply with the Sullivan Principles, the movement opened an additional front with institutional investors. Besides advocating that institutional investors withdraw any direct investments in South African-based companies, anti-Apartheid activists also lobbied for the divestment from all U.S.-based companies having South African interests who had not yet adopted the Sullivan Principles. Institutional investors such as public pension funds were the most susceptible to these types of lobbying efforts.

Public companies with South African interests were thus confronted on two levels: First, shareholder resolutions

With respect to public companies in the United States, a shareholder resolution is a proposal submitted by shareholders for a vote at the company's annual meeting. Typically, resolutions are opposed by the corporation's management, hence the insi ...

were submitted by concerned stockholders who, admitted, posed more of a threat to the often-cherished corporate reputations than to the stock price. Second, the companies were presented with a significant financial threat whereby one or more of their major institutional investors decides to withdraw their investments.

Achieving critical mass (1984–1989)

The disinvestment campaign in the United States, which had been in existence for quite some years, gained a critical mass following the Black political resistance to the 1983 South African constitution which included a "complex set of segregated parliaments". Richard Knight writes:In a total rejection of apartheid, black South Africans mobilized to make the townships ungovernable, black local officials resigned in droves, and the government declared a State of Emergency in 1985 and used thousands of troops to quell "unrest". Television audiences throughout the world were to watch almost nightly reports of massive resistance to apartheid, the growth of a democratic movement, and the savage police and military response.Richard KnightThe result of the widely televised South African response was "a dramatic expansion of international actions to isolate apartheid, actions that combined with the internal situation to force dramatic changes in South Africa's international economic relations".

Chapter: "Sanctions, Disinvestment, and U.S. Corporations in South Africa"

''Sanctioning Apartheid'' (Africa World Press), 1990

Higher education endowments

Students organised a demand that their colleges and universitiesdivest

In finance and economics, divestment or divestiture is the reduction of some kind of asset for financial, ethical, or political objectives or sale of an existing business by a firm. A divestment is the opposite of an investment. Divestiture is a ...

, meaning that the universities were to cease investing in companies that traded or had operations in South Africa. At many universities, many students and faculty protested in order to force action on the issue. The first organised Anti-Apartheid Organization on University Campuses in the United States was CUAA founded at the University of California Berkeley by Ramon Sevilla. Sevilla was a principal organiser that had support from Nelson Mandela, with whom Sevilla was in communication while Mandela was imprisoned at Maximum Security Prison, Robben Island

Maximum Security Prison is an inactive prison at Robben Island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometers (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, Cape Town, South Africa. It is prominent because Nobel Laureate and former President of South Africa N ...

as well as with The African National Congress (the ANC) for committing 196 acts of public violence against apartheid.

Some of the most effective actions in support of the divestment of University investments in U.S. companies doing business in South Africa took place between the years of 1976–1985, as Sevilla travelled throughout the American Continent and Europe gathering support for the overthrow of the South African Apartheid Government, which also led to his arrest at U.C. Berkeley on several occasions in the successful effort to force the University of California to divest all of their investments in companies doing business in South Africa, which also became the driving force for divestment worldwide in all companies doing business in the country of Apartheid South Africa. For example, in April 1986, 61 students were arrested after building a shantytown in front of the chancellor's office at UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant uni ...

. A South Africa divestment activist at Occidental College in Los Angeles was future US president Barack Obama.

As a result of these organised "divestment campaigns", the boards of trustees of several prominent universities voted to divest completely from South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

and companies with major South African interests.

The first of these was Hampshire College

Hampshire College is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. It was opened in 1970 as an experiment in alternative education, in association with four other colleges in the Pioneer Valley: Amherst College, Smith College, Mo ...

in 1977.

These initial successes set a pattern that was later repeated and many more campuses across the country. Activism surged in 1984 on the wave of public interest created by the wide television coverage of the then-recent resistance efforts of the black South Africans.

Overall, according to Knight's analysis, the numbers year over year for educational institutions fully or partially divesting from South Africa were:

Michigan State University

The anti-Apartheid disinvestment campaign on campuses began on the West Coast and Midwest in 1977 at Michigan State University and Stanford University. It had some early successes in 1978 at Michigan State University, which voted for total divestiture, at Columbia University; and the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Following the Michigan State University divestiture in 1978, in 1982, the State of MichiganLegislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

and Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

voted for divestiture by all of the more than 30 State of Michigan colleges and universities, an action later struck down as unconstitutional by the Michigan Court of Appeals in response to a suit against the Act by the University of Michigan.

Columbia University

The initial Columbia divestment, focused largely on bonds and financial institutions directly involved with the South African regime. It followed a year-long campaign first initiated by students who had worked together to block the appointment of former Secretary of StateHenry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

to an endowed chair at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in 1977. Broadly backed by a diverse array of student groups and many notable faculty members the Committee Against Investment in South Africa held numerous teach-ins and demonstrations through the year focused on the trustees' ties to the corporations doing business with South Africa. Trustee meetings were picketed and interrupted by demonstrations culminating in May 1978 in the takeover of the Graduate School of Business.

Smith College

Smith College

Smith College is a private liberal arts women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smith and opened in 1875. It is the largest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite women's coll ...

, in Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence and Leeds) was 29,571.

Northampton is known as an a ...

, which is connected to Hampshire College

Hampshire College is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. It was opened in 1970 as an experiment in alternative education, in association with four other colleges in the Pioneer Valley: Amherst College, Smith College, Mo ...

in Amherst, Massachusetts

Amherst () is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Connecticut River valley. As of the 2020 census, the population was 39,263, making it the highest populated municipality in Hampshire County (although the county seat ...

, through the Five College Consortium

The Five College Consortium (often referred to as simply the Five Colleges) comprises four liberal arts colleges and one university in the Connecticut River Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts: Amherst College, Hampshire College, Mount Hol ...

engaged with divesting from South Africa several years later. In the spring semester of 1986 students at Smith College protested the board of trustees' decision not to fully divest the college's endowment from companies in South Africa. Student protests included a sit-in in College Hall, the main administrative office which included nearly 100 students sleeping in overnight on 24 February 1986. The next day students staged a full blockade of the building, not allowing any staff into the building and anticipating arrest, though the president of the college at the time, Mary Maples Dunn

Mary Maples Dunn (April 6, 1931 – March 19, 2017) was an American historian. Born in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, Dunn graduated from The College of William & Mary in 1954 and received her Ph.D. from Bryn Mawr College in 1959, where she taught and ...

, refused to have the students arrested.

A comprehensive list of the demands they made throughout the demonstration was published on 28 February 1986. The "Women at College Hall" agreed to end the blockade of The Board of Trustees agreed to "issue a statement of intent to deliberate again, with a quorum, the issue of divestment" before Spring Break, and that the Investor Responsibility Committee would meet with representatives from the South African Task Force, the Ethical Investment Committee, and students from the Divestment Committee to look at "a restructuring of the investment policy". Students also demanded that the Board of Trustees "recognize the need for more dialogue with the Smith College community" and that they act on this with more meetings and transparency. In relation to the action, students demanded that a required teach-in be conducted to educate the college and the Board of Trustees on divestment, South African apartheid, and the College Hall Occupation, in addition, a booklet would be compiled by the demonstrators that would be distributed to the college to educate the community on the movement. They also demanded that the president grant amnesty to anyone who directly or indirectly participated in the occupation.

On 1 March 1986, the protest ended when negotiations with administrators led to an agreement that the trustees would re-evaluate their decision, a mandatory teach-in

A teach-in is similar to a general educational forum on any complicated issue, usually an issue involving current political affairs. The main difference between a teach-in and a seminar is the refusal to limit the discussion to a specific time fr ...

would be held, and amnesty would be granted to anyone involved in the demonstration. After student pressures, Smith College voted to divest all $39 million in stocks that they held in companies working in South Africa by 31 October 1988.

Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

only undertook a partial "divestment" from South Africa and only after significant resistance.A CONFLICTED RELATIONSHIP: Harvard supported South Africa through investments, but partially divested under protesti

Harvard Honors Nelson Mandela

. Adam A. Sofen and Alan E. Wirzbicki. Adam Soften and Alan Wirzbicki give this description:

Throughout the 1980s, Harvard professors for the most part avoided involvement with South Africa in protest of apartheid, and then president Derek C. Bok was a vocal supporter of work by the U.S. to prompt reform in South Africa. But the University was slow to pull its own investments out of companies doing business in South Africa, insisting that through its proxy votes, it could more effectively fight apartheid than by purging stocks from its portfolio. But after a decade of protests, Harvard did adopt a policy of selective divestment, and by the end of the 1980s was almost completely out of South Africa.

University of California

At the University of California Berkeley campus, student organizations focused on a campaign ofcivil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". H ...

, with 38 students arrested in 1984, a semester-long sit-in protest with 158 arrests in 1985, and a shantytown protest 1–4 April 1986 that resulted in a violent confrontation between protesters and police and 152 arrests.

The University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, University of Califor ...

, in contrast to the limited action undertaken by Harvard, authorized in 1986 the withdrawal of three billion dollars worth of investments from the apartheid state. Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

stated his belief that the University of California's massive divestment was particularly significant in abolishing white-minority rule in South Africa.

Gettysburg College

In 1989, after a three-year review by theGettysburg College

Gettysburg College is a private liberal arts college in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1832, the campus is adjacent to the Gettysburg Battlefield. Gettysburg College has about 2,600 students, with roughly equal numbers of men and women. ...

Board of Trustees and a five-month campaign by the Salaam Committee—a campus group made up of students and faculty—the college voted to divest $5.4 million from companies connected to South Africa.

States and cities

In addition to campuses, anti-apartheid activists found concerned and sympathetic legislators in cities and states. Several states and localities did pass legislation ordering the sale of such securities, notably the City and County of

In addition to campuses, anti-apartheid activists found concerned and sympathetic legislators in cities and states. Several states and localities did pass legislation ordering the sale of such securities, notably the City and County of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, which passed legislation on 5 June 1978 not to invest "in corporations and banks doing business in or with South Africa". The result was that "by the end of 1989 26 states, 22 counties and over 90 cities had taken some form of binding economic action against companies doing business in South Africa". Many public pension funds connected to these local governments were legislated to disinvestment from South African companies. These local governments also exerted pressure via enacting selective purchasing policies, "whereby cities give preference in bidding on contracts for goods and services to those companies who do not do business in South Africa".

Nebraska

Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

was the first US state to divest from South Africa. The divestment was initiated by Ernie Chambers

Ernest William Chambers (born July 10, 1937) is an American politician and civil rights activist who represented North Omaha's 11th District in the Nebraska State Legislature from 1971 to 2009 and again from 2013 to 2021. He could not run in 2 ...

, the only Black member of the Nebraska legislature

The Nebraska Legislature (also called the Unicameral) is the legislature of the U.S. state of Nebraska. The Legislature meets at the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln. With 49 members, known as "senators", the Nebraska Legislature is the sm ...

. Chambers was angered when he learned that the University of Nebraska

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United State ...

had received a donation of several hundred gold Krugerrands

The Krugerrand (; ) is a South African coin, first minted on 3 July 1967 to help market South African gold and produced by Rand Refinery and the South African Mint. The name is a compound of ''Paul Kruger'', the former President of the South Af ...

. He introduced a nonbinding resolution calling for state pension funds that had been invested directly or indirectly in South Africa to be invested elsewhere. It became state law in 1980.

According to Knight, the beginning of divestment in Nebraska caused little immediate change in business practices; David Packard

David Packard ( ; September 7, 1912 – March 26, 1996) was an American electrical engineer and co-founder, with Bill Hewlett, of Hewlett-Packard (1939), serving as president (1947–64), CEO (1964–68), and chairman of the board (1964–68 ...

of Hewlett Packard

The Hewlett-Packard Company, commonly shortened to Hewlett-Packard ( ) or HP, was an American multinational information technology company headquartered in Palo Alto, California. HP developed and provided a wide variety of hardware components ...

stated "I'd rather lose business in Nebraska than with South Africa." The impact was magnified as other US state governments took similar measures through the 1980s. Nebraska passed stronger legislation in 1984, mandating divestment of all funds from companies doing business in South Africa. This resulted in the divestment of $14.6 million in stocks from Nebraska's public employee pension funds.

Federal involvement

The activity at the state and city level set the stage for action at the federal level.Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act

This began when the Senate and House of Representatives presented Ronald Reagan with the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 which had been introduced by Congressman Ronald Dellums, supported by the members of the Congressional Black Caucus in the House, and piloted through the House by Congressman Howard Wolpe, chairman of the House Africa Subcommittee. Ronald Reagan responded by using his veto, but surprisingly and, in testament to the strength of the anti-Apartheid movement, the Republican-controlled Senate overrode his veto. Knight gives this description of the act:The Act banned new U.S. investment in South Africa, sales to the police and military, and new bank loans, except for the purpose of trade. Specific measures against trade included the prohibition of the import of agricultural goods, textiles, shellfish, steel, iron, uranium, and the products of state-owned corporations.The results of the act were mixed in economic terms according to Knight: Between 1985 and 1987, U.S. imports from South Africa declined 35%, although the trend reverses in 1988 when imports increased by 15%. Between 1985 and 1998, U.S. exports to South Africa increased by 40%. Knight attributes some of the increase in imports in 1988 to lax enforcement of the 1986 Act citing a 1989 study by the

General Accounting Office

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is a legislative branch government agency that provides auditing, evaluative, and investigative services for the United States Congress. It is the supreme audit institution of the federal gover ...

. Knight writes that a "major weakness of the Act is that it does little to prohibit exports to South Africa, even in such areas as computers and other capital goods".

Budget Reconciliation Act

A second federal measure introduced by RepresentativeCharles Rangel

Charles Bernard Rangel (, ; born June 11, 1930) is an American politician who was a U.S. representative for districts in New York from 1971 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the second-longest serving incumbent member of the Ho ...

in 1987 as an amendment to the Budget Reconciliation Act halted the ability of U.S. corporations from attaining tax reimbursements for taxes paid in South Africa. The result was that U.S. corporations operating in South Africa were subject to double taxation. According to Knight:

The sums of money involved are large. According to the Internal Revenue Service, taxes involved in 1982 were $211,593,000 on taxable income of $440,780,000. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce in South Africa has estimated that the measure increases the tax bill for U.S. companies from 57.5% to 72% of profits in South Africa.

Further legislative efforts

An additional and much harsher sanctions bill was passed by the House of Representatives (Congress) in August 1988. This bill mandated "the withdrawal of all U.S. companies from South Africa, the sale by U.S. residents of all investments in South African companies and an end to most trade, except for the import of certain strategic minerals". In the end, the bill didn't become law as wasn't able to pass the Senate. (In the United States legislative system a bill must be passed by both the Senate and the House of Representatives before it can be signed into law by the President.) Even so, the fact that such a harsh bill made any progress at all through the legislature "alerted both the South African government and U.S. business that significant further sanctions were likely to be forthcoming" if the political situation in South Africa remained unchanged.Effects on South Africa

Economic effects

While post-colonial African countries had already imposed sanctions on South Africa in solidarity with the

While post-colonial African countries had already imposed sanctions on South Africa in solidarity with the Defiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws was presented by the African National Congress (ANC) at a conference held in Bloemfontein, South Africa in December 1951. The Campaign had roots in events leading up the conference. The demonstrations, ...

, these measures had little effect because of the relatively small economies of those involved. The disinvestment campaign only impacted South Africa after the major Western nations, including the United States, got involved beginning in mid-1984. From 1984 onwards, according to Knight, because of the disinvestment campaign and the repayment of foreign loans, South Africa experienced considerable capital flight

Capital flight, in economics, occurs when assets or money rapidly flow out of a country, due to an event of economic consequence or as the result of a political event such as regime change or economic globalization. Such events could be an increa ...

. The net capital movement out of South Africa was:

* R9.2 billion in 1985

* R6.1 billion in 1986

* R3.1 billion in 1987

* R5.5 billion in 1988

The capital flight triggered a dramatic decline in the international exchange rate of the South African currency, the rand

The RAND Corporation (from the phrase "research and development") is an American nonprofit global policy think tank created in 1948 by Douglas Aircraft Company to offer research and analysis to the United States Armed Forces. It is finan ...

. The currency decline made imports more expensive which in turn caused inflation in South Africa to rise at a very steep 12–15% per year.

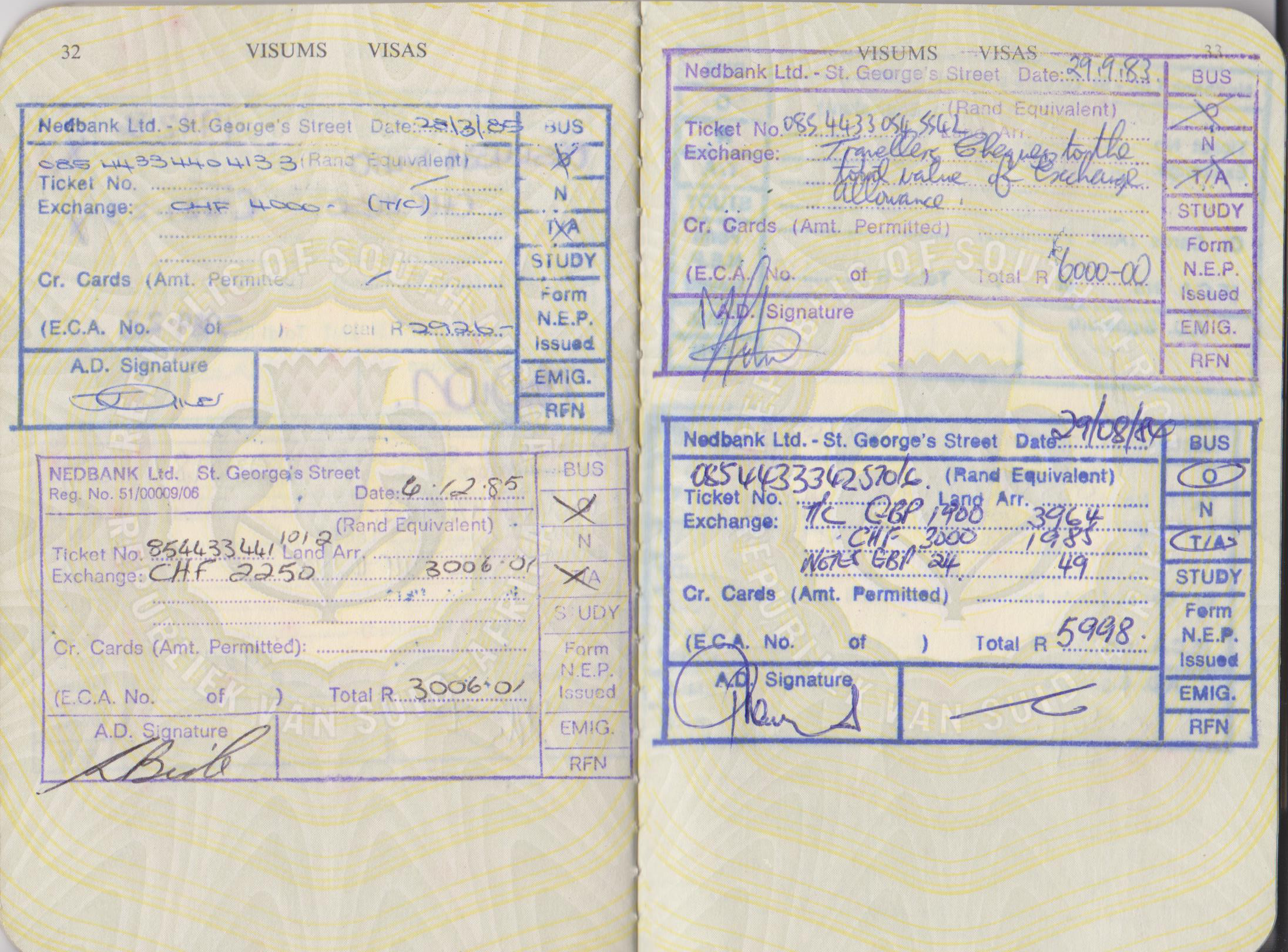

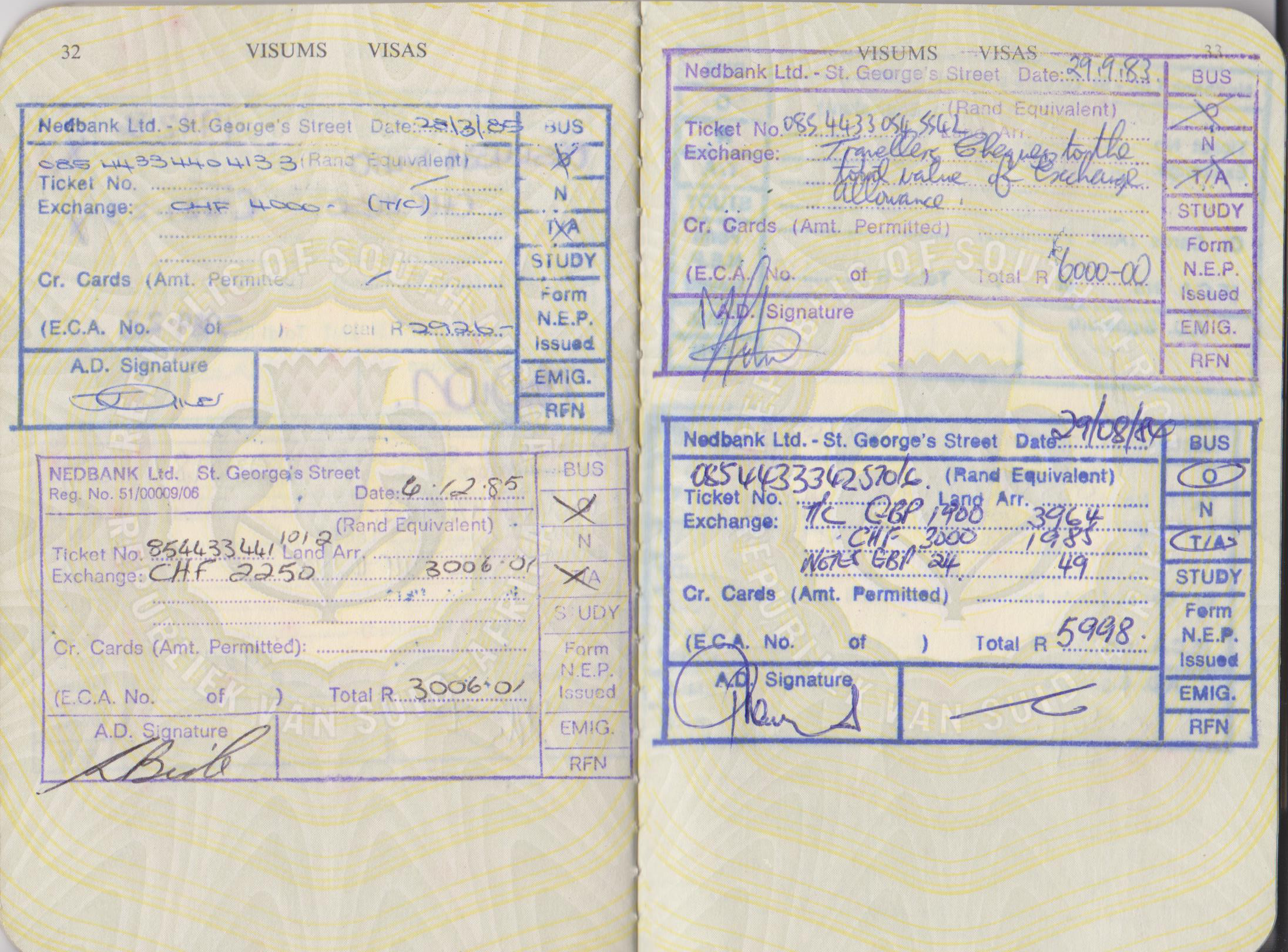

The South African government did attempt to restrict the damaging outflow of capital. Knight writes that "in September 1985 it imposed a system of exchange control and a debt repayments standstill. Under exchange control, South African residents are generally prohibited from removing capital from the country and foreign investors can only remove investments via the financial rand

The South African financial rand was the most visible part of a system of capital controls. Although the financial rand was abolished in March 1995, some capital controls remain in place. These capital controls are locally referred to as "exchang ...

, which is traded at a 20% to 40% discount compared to the commercial rand. This means companies that disinvest get significantly fewer dollars for the capital they withdraw."

Anti-apartheid opposition

While disinvestment, boycotts, and sanctions aimed at the removal of the apartheid system, there was also considerable opposition from within the anti-apartheid movement within South Africa coming from both black and white leaders.Mangosuthu Buthelezi

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi (born 27 August 1928) is a South African politician and Zulu traditional leader who is currently a Member of Parliament and the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family. He was Chief Minister of th ...

, Chief Minister of KwaZulu

KwaZulu was a semi-independent bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a homeland for the Zulu people. The capital was moved from Nongoma to Ulundi in 1980.

It was led until its abolition in 1994 by Chief Mangosuthu ...

and president of the Inkatha Freedom Party

The Inkatha Freedom Party ( zu, IQembu leNkatha yeNkululeko, IFP) is a right-wing political party in South Africa. The party has been led by Velenkosini Hlabisa since the party's 2019 National General Conference. Mangosuthu Buthelezi founde ...

slammed sanctions, stating that "They can only harm all the people of Southern Africa. They can only lead to more hardships, particularly for the blacks." Well known anti-apartheid Members of Parliament Helen Suzman

Helen Suzman, OMSG, DBE (née Gavronsky; 7 November 1917 – 1 January 2009) was a South African anti-apartheid activist and politician. She represented a series of liberal and centre-left opposition parties during her 36-year tenure in th ...

and Harry Schwarz also strongly opposed moves to disinvest from South Africa. Both politicians of the Progressive Federal Party, they argued that disinvestment would cause further economic hardships for black people, which would ultimately worsen the political climate for negotiations. Suzman described them as "self-defeating, wrecking the economy and do not assist anybody irrespective of race". Schwarz also argued that "Morality is cheap when someone else is paying."

Outside criticism

Many criticised disinvestment because of its economic impact on ordinary black South Africans, such asPrime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

, Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

, who described sanctions and disinvestment as "the way of poverty, starvation and destroying the hopes of the very people – all of them—whom you wish to help." John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament (MP) for Huntingdon, formerly Hunting ...

, then her Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwe ...

, said disinvestment would "feed white consciences outside South Africa, not black bellies within it", although in 2013, he said that the Conservative Government led by Margaret Thatcher was wrong to oppose tougher sanctions against South Africa during the apartheid era.

Many conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

opposed the disinvestment campaign, accusing its advocates of hypocrisy for not also proposing that the same sanctions be leveled on either the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

or the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

.

Libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian ...

also opposed this policy, asserting that the most-direct adverse impact of the boycott would actually be felt by the black workers in that country, and the best way to remedy the problem of apartheid was by promoting trade and the growth of free market capitalism

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any o ...

in South Africa.

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

, who was the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

during the time the disinvestment movement was at its peak, also opposed it, instead favoring a policy of "constructive engagement

Constructive engagement was the name given to the conciliatory foreign policy of the Reagan administration towards the apartheid regime in South Africa. Devised by Chester Crocker, Reagan's U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affair ...

" with the Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foothi ...

government. He opposed pressure from Congress and his own party for tougher sanctions until his veto was overridden.

See also

*Anti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-White population who were persecuted by the policie ...

* Anti-Apartheid movement in the United States

The anti-apartheid movement was a worldwide effort to end South Africa's apartheid regime and its oppressive policies of racial segregation. The movement emerged after the National Party government in South Africa won the election of 1948 and en ...

* Academic boycotts of South Africa

The academic boycott of South Africa comprised a series of boycotts of South African academic institutions and scholars initiated in the 1960s, at the request of the African National Congress, with the goal of using such international pressure ...

* Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions

Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) is a Palestinian-led movement promoting boycotts, divestments, and economic sanctions against Israel. Its objective is to pressure Israel to meet what the BDS movement describes as Israel's obligations ...

* Disinvestment

Disinvestment refers to the use of a concerted economic boycott to pressure a government, industry, or company towards a change in policy, or in the case of governments, even regime change. The term was first used in the 1980s, most commonly in ...

* Economic history of South Africa

Prior to the arrival of the European settlers in the 17th century the economy of what was to become South Africa was dominated by subsistence agriculture and hunting.

In the north, central and east of the country tribes of Bantu peoples occupi ...

* International sanctions during apartheid

As a response to South Africa's apartheid policies, the international community adopted economic sanctions as condemnation and pressure.

On 6 November 1962, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 1761, a non-binding resolution ...

* Northeast Coalition for the Liberation of Southern Africa

The Northeast Coalition for the Liberation of Southern Africa (NECLSA) was an anti-apartheid organization founded in 1977 at Yale University by members of the Black Student Alliance at Yale ( BSAY) and students at Rutgers University in response ...

* Socially responsible investing

Socially responsible investing (SRI), social investment, sustainable socially conscious, "green" or ethical investing, is any investment strategy which seeks to consider both financial return and social/environmental good to bring about soc ...

* Disinvestment from Iran

Disinvestment from Iran is a campaign primarily in the United States that aims to encourage disinvestment from the state of Iran.

Legislation Federal

The Iran Sanctions Enabling Act (H.R. 1327) was introduced in US Congress by Reps. Barney Frank ...

* Disinvestment from Israel

Disinvestment from Israel is a campaign conducted by religious and political entities which aims to use disinvestment to pressure the government of Israel to put "an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories captured during the 1967 ...

References

Further reading

"For U.S. Firms in South Africa, The Threat of Coercive Sullivan Principles"

Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (abbreviated to Heritage) is an American conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. that is primarily geared toward public policy. The foundation took a leading role in the conservative movement during the preside ...

. 12 November 1984.

"On 'Constructive Engagement' in South Africa"

''The MIT Tech''. 105(47). 5 November 1985.

"The Choice for U.S. Policy in South Africa: Reform or Vengeance"

Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (abbreviated to Heritage) is an American conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. that is primarily geared toward public policy. The foundation took a leading role in the conservative movement during the preside ...

. 25 July 1986.

"Misconceptions about U.S. policy toward South Africa"

US Department of State Bulletin. September 1986. * Richard Knight

''Sanctioning Apartheid'' (Africa World Press). 1990.

"Disinvestment from South Africa: They Did Well by Doing Good"

''

Contemporary Economic Policy

''Contemporary Economic Policy'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal published by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Western Economic Association International, along with ''Economic Inquiry''. The current editor-in-chief is Brad R. Humphreys (West ...

''. XV(1):76–86. January 1997.

* Robert Kinloch Massie, ''Loosing the Bonds: The United States and South Africa in the Apartheid Years'', Doubleday, New York, 1997.

External links

African Activist Archive

– more than 7,000 documents, posters, T-shirts, buttons, photos, video, and memories of activism in the U.S. to support the struggles of African peoples against apartheid, colonialism, and social injustice, 1950s–1990s. Also includes a directory of African activist organizations across the U.S.

* ttp://richardknight.homestead.com/files/useconomicinv.htm U.S. Economic Involvement with Apartheid South Africa

An Analysis of U.S. Disinvestment from South Africa: Unity, Rights, and Justice

Black South African Opinion on Disinvestment

The Crusade Against South Africa

* [http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0002vwd4 Image of UCLA students in sit-down protest with banner reading "UC Out of South Africa! Divest Now" as two UC Police officers watch Los Angeles, California, 1986.] Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles. {{DEFAULTSORT:Disinvestment From South Africa Boycotts of apartheid South Africa International sanctions South Africa–United States relations Economy of South Africa Disinvestment Library of Congress Africa Collection related Foreign trade of South Africa Investment in South Africa