dirigible on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of  In early dirigibles, the lifting gas used was

In early dirigibles, the lifting gas used was

"Piece by piece, Goodyear's new airship arrives at Wingfoot hangar,"

September 6, 2012, updated September 7, 2012, '' Akron Beacon Journal,''

Short History of Brazilian Aeronautics

(PDF), 44th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada, 9–12 January 2006. In 1874,

In 1874,  In 1897, an airship with an aluminum envelope was built by the Hungarian- Croatian engineer David Schwarz. It made its first flight at Tempelhof field in Berlin after Schwarz had died. His widow, Melanie Schwarz, was paid 15,000 marks by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin to release the industrialist Carl Berg from his exclusive contract to supply Schwartz with

In 1897, an airship with an aluminum envelope was built by the Hungarian- Croatian engineer David Schwarz. It made its first flight at Tempelhof field in Berlin after Schwarz had died. His widow, Melanie Schwarz, was paid 15,000 marks by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin to release the industrialist Carl Berg from his exclusive contract to supply Schwartz with

In July 1900, the Luftschiff

In July 1900, the Luftschiff

/ref> Others, such as In 1902 the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo published details of an innovative airship design in Spain and France. With a non-rigid body and internal bracing wires, it overcame the flaws of these types of aircraft as regards both rigid structure (zeppelin type) and flexibility, providing the airships with more stability during flight, and the capability of using heavier engines and a greater passenger load. In 1905, helped by Captain A. Kindelán, he built the airship "España" at the

In 1902 the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo published details of an innovative airship design in Spain and France. With a non-rigid body and internal bracing wires, it overcame the flaws of these types of aircraft as regards both rigid structure (zeppelin type) and flexibility, providing the airships with more stability during flight, and the capability of using heavier engines and a greater passenger load. In 1905, helped by Captain A. Kindelán, he built the airship "España" at the

Luftschiff

/ref> and Italian Enrico Forlanini's firm had built and flown the first two

The British Army had abandoned airship development in favour of aeroplanes before the start of the war, but the Royal Navy had recognized the need for small airships to counteract the submarine and mine threat in coastal waters. Beginning in February 1915, they began to develop the SS (Sea Scout) class of blimp. These had a small envelope of and at first used aircraft

The British Army had abandoned airship development in favour of aeroplanes before the start of the war, but the Royal Navy had recognized the need for small airships to counteract the submarine and mine threat in coastal waters. Beginning in February 1915, they began to develop the SS (Sea Scout) class of blimp. These had a small envelope of and at first used aircraft

Britain, the United States and Germany built rigid airships between the two world wars. Italy and France made limited use of Zeppelins handed over as war reparations. Italy, the Soviet Union, the United States and Japan mainly operated semi-rigid airships.

Under the terms of the

Britain, the United States and Germany built rigid airships between the two world wars. Italy and France made limited use of Zeppelins handed over as war reparations. Italy, the Soviet Union, the United States and Japan mainly operated semi-rigid airships.

Under the terms of the

America then started constructing the , designed by the

America then started constructing the , designed by the  The U.S. Navy experimented with the use of airships as airborne aircraft carriers, developing an idea pioneered by the British. The USS ''Los Angeles'' was used for initial experiments, and the and , the world's largest at the time, were used to test the principle in naval operations. Each carried four F9C Sparrowhawk

The U.S. Navy experimented with the use of airships as airborne aircraft carriers, developing an idea pioneered by the British. The USS ''Los Angeles'' was used for initial experiments, and the and , the world's largest at the time, were used to test the principle in naval operations. Each carried four F9C Sparrowhawk  By the mid-1930s, only Germany still pursued airship development. The Zeppelin company continued to operate the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on passenger service between Frankfurt and

By the mid-1930s, only Germany still pursued airship development. The Zeppelin company continued to operate the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on passenger service between Frankfurt and

Only ''K''- and ''TC''-class airships were suitable for combat and they were quickly pressed into service against Japanese and German

Only ''K''- and ''TC''-class airships were suitable for combat and they were quickly pressed into service against Japanese and German  In the years 1942–44, approximately 1,400 airship pilots and 3,000 support crew members were trained in the military airship crew training program and the airship military personnel grew from 430 to 12,400. The U.S. airships were produced by the Goodyear factory in

In the years 1942–44, approximately 1,400 airship pilots and 3,000 support crew members were trained in the military airship crew training program and the airship military personnel grew from 430 to 12,400. The U.S. airships were produced by the Goodyear factory in  Some Navy blimps saw action in the European war theater. In 1944–45, the U.S. Navy moved an entire squadron of eight Goodyear K class blimps (K-89, K-101, K-109, K-112, K-114, K-123, K-130, & K-134) with flight and maintenance crews from Weeksville Naval Air Station in North Carolina to

Some Navy blimps saw action in the European war theater. In 1944–45, the U.S. Navy moved an entire squadron of eight Goodyear K class blimps (K-89, K-101, K-109, K-112, K-114, K-123, K-130, & K-134) with flight and maintenance crews from Weeksville Naval Air Station in North Carolina to  Navy blimps of Fleet Airship Wing Five, (ZP-51) operated from bases in

Navy blimps of Fleet Airship Wing Five, (ZP-51) operated from bases in

Although airships are no longer used for major cargo and passenger transport, they are still used for other purposes such as

Although airships are no longer used for major cargo and passenger transport, they are still used for other purposes such as  The Switzerland-based Skyship 600 has also played other roles over the years. For example, it was flown over

The Switzerland-based Skyship 600 has also played other roles over the years. For example, it was flown over

The U.S. government has funded two major projects in the high altitude arena. The Composite Hull High Altitude Powered Platform (CHHAPP) is sponsored by

The U.S. government has funded two major projects in the high altitude arena. The Composite Hull High Altitude Powered Platform (CHHAPP) is sponsored by

In the 1990s, the successor of the original Zeppelin company in

In the 1990s, the successor of the original Zeppelin company in

Several companies, such as Cameron Balloons in

Several companies, such as Cameron Balloons in

File:Aerosail.jpg, Aerosail

File:Mlle Louise ballon dirigeable à propulsion humaine.jpg, Mlle Louise pedal Airship by Stephane Rousson

File:Zeppy Piloté par Stephane Belgrand Rousson à Villefranche sur Mer.jpg, Zeppy 3 by Stephane Rousson

File:Zeppy Base Nature Frejus.jpg, Zeppy One

Today, with large, fast, and more cost-efficient

Today, with large, fast, and more cost-efficient

Airships have been proposed as a potential cheap alternative to surface rocket launches for achieving Earth orbit. JP Aerospace have proposed the Airship to Orbit project, which intends to float a multi-stage airship up to mesospheric altitudes of 55 km (180,000 ft) and then use

Airships have been proposed as a potential cheap alternative to surface rocket launches for achieving Earth orbit. JP Aerospace have proposed the Airship to Orbit project, which intends to float a multi-stage airship up to mesospheric altitudes of 55 km (180,000 ft) and then use

High Safety Level (page 5) and Structural Vulnerability Tests (page 7)

World Skycat. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

''USS Los Angeles: The Navy's Venerable Airship and Aviation Technology''

2003, *Ausrotas, R. A., "Basic Relationships for LTA Technical Analysis," ''Proceedings of the Interagency Workshop on Lighter-Than-Air Vehicles'', Massachusetts Institute of Technology Flight Transportation Library, 1975 *Archbold, Rich and Ken Marshall, ''Hindenburg, an Illustrated History'', 1994 *Bailey, D. B., and Rappoport, H. K., ''Maritime Patrol Airship Study'', Naval Air Development Center, 1980 *Botting, Douglas, ''Dr. Eckener's Dream Machine''. New York Henry Hold and Company, 2001, * * *Burgess, Charles P., ''Airship Design'', (1927) 2004 * Cross, Wilbur, ''Disaster at the Pole'', 2002 *Dick, Harold G., with Robinson, Douglas H., ''Graf Zeppelin & Hindenburg'', Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985, ISBN * *Ege, L.; ''Balloons and Airships'', Blandford (1973). *Frederick, Arthur, et al., ''Airship saga: The history of airships seen through the eyes of the men who designed, built, and flew them'', 1982, *Griehl, Manfred and Joachim Dressel, ''Zeppelin! The German Airship Story'', 1990, *Higham, Robin, ''The British Rigid Airship, 1908–1931: A study in weapons policy'', London, G. T. Foulis, 1961, *Keirns, Aaron J, "America's Forgotten Airship Disaster: The Crash of the USS Shenandoah", Howard, Little River Publishing, 1998, . *Khoury, Gabriel Alexander (Editor), ''Airship Technology (Cambridge Aerospace Series)'', 2004, * * * *McKee, Alexander, ''Ice crash'', 1980, * *Morgala, Andrzej, ''Sterowce w II Wojnie Światowej'' (Airships in the Second World War), Lotnictwo, 1992 *Mowthorpe, Ces, ''Battlebags: British Airships of the First World War'', 1995 * *Robinson, Douglas H., ''Giants in the Sky'', University of Washington Press, 1973, *Robinson, Douglas H., ''The Zeppelin in Combat: A history of the German Naval Airship Division, 1912–1918'', Atglen, PA, Shiffer Publications, 1994, *Smith, Richard K. ''The Airships Akron & Macon: flying aircraft carriers of the United States Navy'', Annapolis MD, US Naval Institute Press, 1965, *Shock, James R., Smith, David R., ''The Goodyear Airships'', Bloomington, Illinois, Airship International Press, 2002, *Sprigg, C., ''The Airship: Its design, history, operation and future'', London 1931, Samson Low, Marston and Company. * *Toland, John, ''Ships in the Sky'', New York, Henry Hold; London, Muller, 1957, *Vaeth, J. Gordon, ''Blimps & U-Boats'', Annapolis, Maryland, US Naval Institute Press, 1992, *Ventry, Lord; Kolesnik, Eugene, ''Jane's Pocket Book 7: Airship Development'', 1976 *Ventry, Lord; Koesnik, Eugene M., ''Airship Saga'', Poole, Dorset, Blandford Press, 1982, p. 97 *Winter, Lumen; Degner, Glenn, ''Minute Epics of Flight'', New York, Grosset & Dunlap, 1933. *US War Department, ''Airship Aerodynamics: Technical Manual'', (1941) 2003,

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat

An aerostat (, via French) is a lighter-than-air aircraft that gains its lift through the use of a buoyant gas. Aerostats include unpowered balloons and powered airships. A balloon may be free-flying or tethered. The average density of the c ...

or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas

A lifting gas or lighter-than-air gas is a gas that has a density lower than normal atmospheric gases and rises above them as a result. It is required for aerostats to create buoyancy, particularly in lighter-than-air aircraft, which include free ...

that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early dirigibles, the lifting gas used was

In early dirigibles, the lifting gas used was hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

, due to its high lifting capacity and ready availability. Helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic ta ...

gas has almost the same lifting capacity and is not flammable, unlike hydrogen, but is rare and relatively expensive. Significant amounts were first discovered in the United States and for a while helium was only available for airships in that country. Most airships built since the 1960s have used helium, though some have used hot air.A few airships after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

used hydrogen. The first British airship to use helium was the ''Chitty Bang Bang'' of 1967.

The envelope of an airship may form the gasbag, or it may contain a number of gas-filled cells. An airship also has engines, crew, and optionally also payload accommodation, typically housed in one or more gondolas suspended below the envelope.

The main types of airship are non-rigid, semi-rigid, and rigid. Non-rigid airships, often called "blimps", rely on internal pressure to maintain their shape. Semi-rigid airships maintain the envelope shape by internal pressure, but have some form of supporting structure, such as a fixed keel, attached to it. Rigid airships have an outer structural framework that maintains the shape and carries all structural loads, while the lifting gas is contained in one or more internal gasbags or cells. Rigid airships were first flown by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin and the vast majority of rigid airships built were manufactured by the firm he founded, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin

Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH is a German aircraft manufacturing company. It is perhaps best known for its leading role in the design and manufacture of rigid airships, commonly referred to as ''Zeppelins'' due to the company's prominence. The name ...

. As a result, rigid airships are often called zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

s.

Airships were the first aircraft capable of controlled powered flight, and were most commonly used before the 1940s; their use decreased as their capabilities were surpassed by those of aeroplanes. Their decline was accelerated by a series of high-profile accidents, including the 1930 crash and burning of the British R101

R101 was one of a pair of British rigid airships completed in 1929 as part of a British government programme to develop civil airships capable of service on long-distance routes within the British Empire. It was designed and built by an Air M ...

in France, the 1933 and 1935 storm-related crashes of the twin airborne aircraft carrier U.S. Navy helium-filled rigids, the and USS ''Macon'' respectively, and the 1937 burning of the German hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

-filled '' Hindenburg''. From the 1960s, helium airships have been used where the ability to hover for a long time outweighs the need for speed and manoeuvrability, such as advertising, tourism, camera platforms, geological surveys and aerial observation.

Terminology

Airship

During the pioneer years of aeronautics, terms such as "airship", "air-ship", "air ship" and "ship of the air" meant any kind of navigable or dirigible flying machine. In 1919 Frederick Handley Page was reported as referring to "ships of the air," with smaller passenger types as "air yachts." In the 1930s, large intercontinental flying boats were also sometimes referred to as "ships of the air" or "flying-ships". Nowadays the term "airship" is used only for powered, dirigible balloons, with sub-types being classified as rigid, semi-rigid or non-rigid. Semi-rigid architecture is the more recent, following advances in deformable structures and the exigency of reducing weight and volume of the airships. They have a minimal structure that keeps the shape jointly with overpressure of the gas envelope.Aerostat

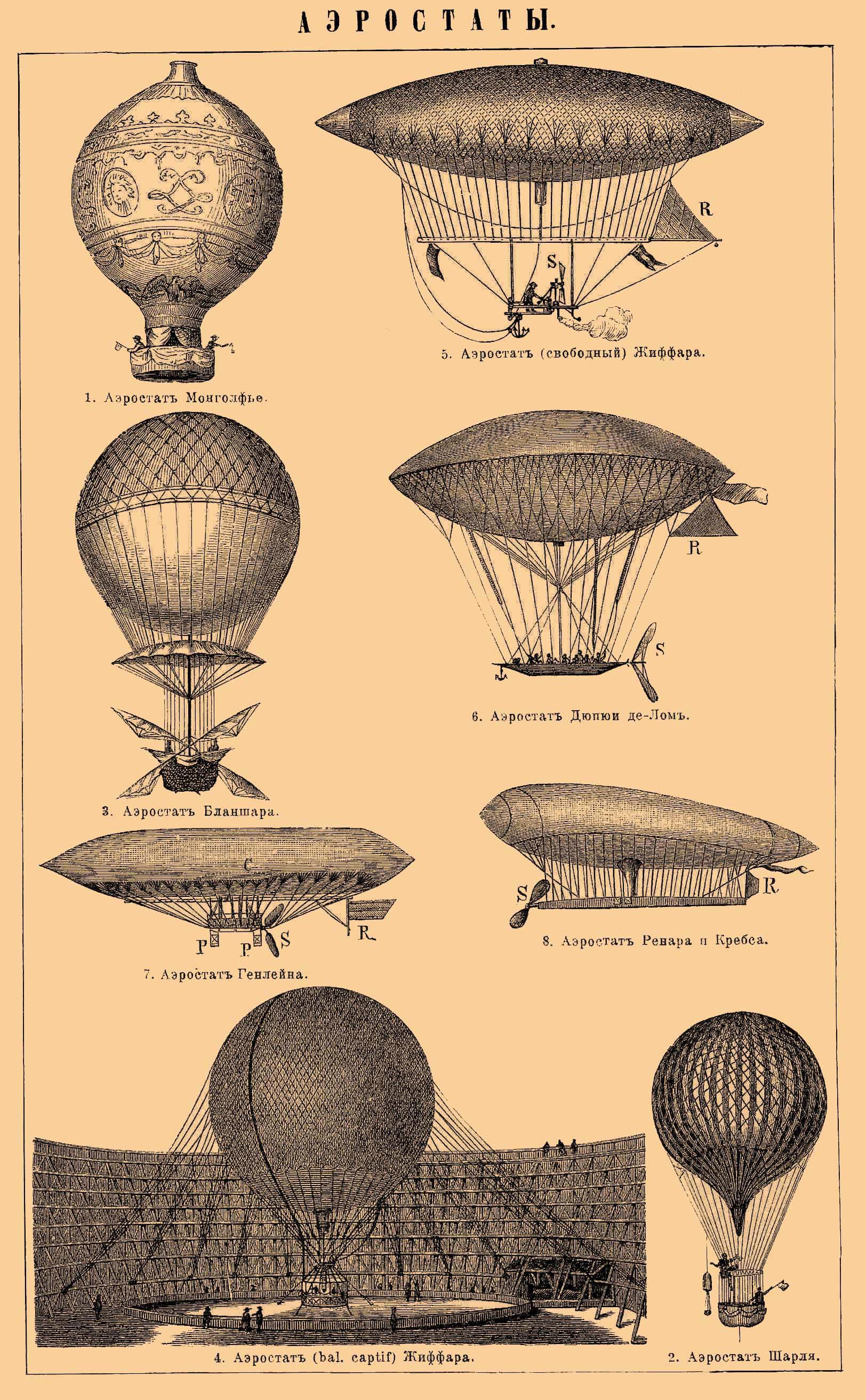

Anaerostat

An aerostat (, via French) is a lighter-than-air aircraft that gains its lift through the use of a buoyant gas. Aerostats include unpowered balloons and powered airships. A balloon may be free-flying or tethered. The average density of the c ...

is an aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or by using the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in ...

that remains aloft using buoyancy or static lift, as opposed to the aerodyne, which obtains lift by moving through the air. Airships are a type of aerostat.Ege (1973). The term ''aerostat'' has also been used to indicate a tethered or moored balloon

A tethered, moored or captive balloon is a balloon that is restrained by one or more tethers attached to the ground and so it cannot float freely. The base of the tether is wound around the drum of a winch, which may be fixed or mounted on a vehic ...

as opposed to a free-floating balloon. Aerostats today are capable of lifting a payload of to an altitude of more than above sea level. They can also stay in the air for extended periods of time, particularly when powered by an on-board generator or if the tether contains electrical conductors. Due to this capability, aerostats can be used as platforms for telecommunication services. For instance, Platform Wireless International Corporation announced in 2001 that it would use a tethered airborne payload to deliver cellular phone service to a region in Brazil. The European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

's ABSOLUTE project was also reportedly exploring the use of tethered aerostat stations to provide telecommunications during disaster response.

Dirigible

Airships were originally called ''dirigible balloons'', from theFrench

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

''ballon dirigeable'' often shortened to ''dirigeable'' (meaning "steerable", from the French ''diriger'' – to direct, guide or steer). This was the name that inventor Henri Giffard gave to his machine that made its first flight on 24 September 1852.

Blimp

A blimp is a non-rigid aerostat. In British usage it refers to any non-rigid aerostat, includingbarrage balloon

A barrage balloon is a large uncrewed tethered balloon used to defend ground targets against aircraft attack, by raising aloft steel cables which pose a severe collision risk to aircraft, making the attacker's approach more difficult. Early barra ...

s and other kite balloons, having a streamlined shape and stabilising tail fins. Some blimps may be powered dirigibles, as in early versions of the Goodyear Blimp. Later Goodyear dirigibles, though technically ''semi-rigid airships,'' have still been called "blimps" by the company.Mackinnon, Jim"Piece by piece, Goodyear's new airship arrives at Wingfoot hangar,"

September 6, 2012, updated September 7, 2012, '' Akron Beacon Journal,''

Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 Census, the city ...

(Goodyear blimps' base), at Ohio.com, retrieved June 28, 2021

Zeppelin

The term zeppelin originally referred to airships manufactured by the German Zeppelin Company, which built and operated the first rigid airships in the early years of the twentieth century. The initials LZ, for (German for "Zeppelin airship"), usually prefixed their craft's serial identifiers. Streamlined rigid (or semi-rigid) airships are often referred to as "Zeppelins", because of the fame that this company acquired due to the number of airships it produced.Hybrid airship

Hybrid airships fly with a positive aerostatic contribution, usually equal to the empty weight of the system, and the variable payload is sustained by propulsion or aerodynamic contribution.Classification

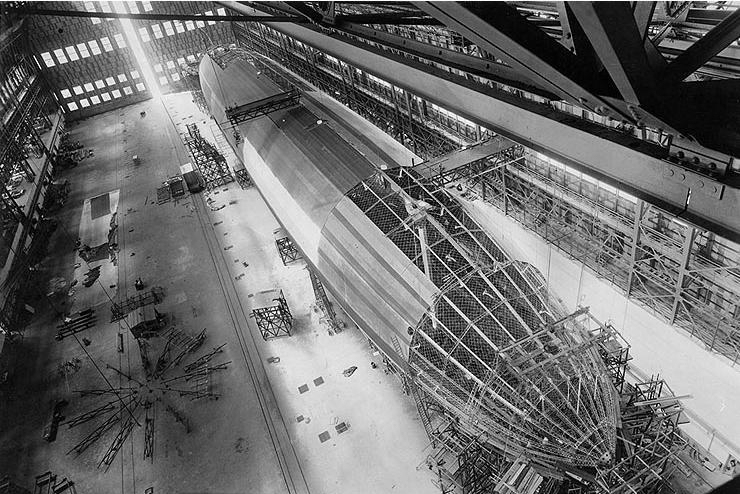

Airships are classified according to their method of construction into rigid, semi-rigid and non-rigid types.Rigid airships

A rigid airship has a rigid framework covered by an outer skin or envelope. The interior contains one or more gasbags, cells or balloons to provide lift. Rigid airships are typically unpressurised and can be made to virtually any size. Most, but not all, of the GermanZeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

airships have been of this type.

Semi-rigid airships

A semi-rigid airship has some kind of supporting structure but the main envelope is held in shape by the internal pressure of the lifting gas. Typically the airship has an extended, usually articulated keel running along the bottom of the envelope to stop it kinking in the middle by distributing suspension loads into the envelope, while also allowing lower envelope pressures.Non-rigid airships

Non-rigid airships are often called "blimps". Most, but not all, of the American Goodyear airships have been blimps. A non-rigid airship relies entirely on internal gas pressure to retain its shape during flight. Unlike the rigid design, the non-rigid airship's gas envelope has no compartments. It typically has smaller internal bags or "ballonets". At sea level, these are filled with air. As altitude is increased, the lifting gas expands and air from the ballonets is expelled through valves to maintain the hull's shape. To return to sea level, the process is reversed: air is forced back into the ballonets by scooping air from the engine exhaust and using auxiliary blowers.Construction

Envelope

The envelope itself is the structure, including textiles that contain the buoyant gas. Internally two ballonets placed in the front part and in the rear part of the hull contains air. The problem of the exact determination of the pressure on an airship envelope is still problematic and has fascinated major scientists such as Theodor Von Karman. A few airships have been metal-clad, with rigid and nonrigid examples made. Each kind used a thin gastight metal envelope, rather than the usual rubber-coated fabric envelope. Only four metal-clad ships are known to have been built, and only two actually flew: Schwarz's first aluminum rigid airship of 1893 collapsed, Dooley, A.185-A.186 citing Robinson, pp.2–3 collapsed on inflation while his second flew; the nonrigid ZMC-2 built for the U.S. Navy flew from 1929 to 1941 when it was scrapped as too small for operational use on anti-submarine patrols; while the 1929 nonrigid Slate Aircraft Corporation ''City of Glendale'' collapsed on its first flight attempt.Lifting gas

Thermal airships use a heated lifting gas, usually air, in a fashion similar to hot air balloons. The first to do so was flown in 1973 by the British company Cameron Balloons.Gondola

Propulsion and control

Small airships carry their engine(s) in their gondola. Where there were multiple engines on larger airships, these were placed in separate nacelles, termed ''power cars'' or ''engine cars''. To allow asymmetric thrust to be applied for maneuvering, these power cars were mounted towards the sides of the envelope, away from the center line gondola. This also raised them above the ground, reducing the risk of a propeller strike when landing. Widely spaced power cars were also termed ''wing cars'', from the use of "wing" to mean being on the side of something, as in a theater, rather than the aerodynamic device. These engine cars carried a crew during flight who maintained the engines as needed, but who also worked the engine controls, throttle etc., mounted directly on the engine. Instructions were relayed to them from the pilot's station by a telegraph system, as on a ship.Environmental benefits

The main advantage of airships with respect to any other vehicle is of environmental nature. They require less energy to remain in flight, if compared to any other air vehicle. The proposed Varialift airship, powered by a mixture of solar-powered engines and conventional jet engines, would use only an estimated 8 percent of the fuel required byjet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by jet engines.

Whereas the engines in propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much lower speeds and altitudes, jet ...

. Furthermore, utilizing the jet stream could allow for a faster and more energy-efficient cargo transport alternative to maritime shipping

Maritime transport (or ocean transport) and hydraulic effluvial transport, or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people (passengers) or goods (cargo) via waterways. Freight transport by sea has been widely used throug ...

. This is one of the reasons why China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

has embraced their use recently.

History

Early pioneers

17th–18th centuries

In 1670, the Jesuit Father Francesco Lana de Terzi, sometimes referred to as the "Father of Aeronautics", published a description of an "Aerial Ship" supported by four copper spheres from which the air was evacuated. Although the basic principle is sound, such a craft was unrealizable then and remains so to the present day, since external air pressure would cause the spheres to collapse unless their thickness was such as to make them too heavy to be buoyant. A hypothetical craft constructed using this principle is known as a '' vacuum airship''. In 1709, the Brazilian-Portuguese Jesuit priestBartolomeu de Gusmão

Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão (December 1685 – 18 November 1724) was a Brazilian-born Portuguese priest and naturalist, who was a pioneer of lighter-than-air airship design.

Early life

Gusmão was born at Santos, then part of the Portugues ...

made a hot air balloon, the Passarola, ascend to the skies, before an astonished Portuguese court. It would have been on August 8, 1709, when Father Bartolomeu de Gusmão held, in the courtyard of the Casa da Índia

The Casa da Índia (, English: ''India House'' or ''House of India'') was a Portuguese state-run commercial organization during the Age of Discovery. It regulated international trade and the Portuguese Empire's territories, colonies, and factor ...

, in the city of Lisbon, the first Passarola demonstration. The balloon caught fire without leaving the ground, but, in a second demonstration, it rose to 95 meters in height. It was a small balloon of thick brown paper, filled with hot air, produced by the "fire of material contained in a clay bowl embedded in the base of a waxed wooden tray". The event was witnessed by King John V of Portugal

Dom John V ( pt, João Francisco António José Bento Bernardo; 22 October 1689 – 31 July 1750), known as the Magnanimous (''o Magnânimo'') and the Portuguese Sun King (''o Rei-Sol Português''), was King of Portugal from 9 December 17 ...

and the future Pope Innocent XIII.

A more practical dirigible airship was described by Lieutenant Jean Baptiste Marie Meusnier in a paper entitled "''Mémoire sur l’équilibre des machines aérostatiques''" (Memorandum on the equilibrium of aerostatic machines) presented to the French Academy on 3 December 1783. The 16 water-color drawings published the following year depict a streamlined envelope with internal ballonets that could be used for regulating lift: this was attached to a long carriage that could be used as a boat if the vehicle was forced to land in water. The airship was designed to be driven by three propellers and steered with a sail-like aft rudder. In 1784, Jean-Pierre Blanchard

Jean-Pierre rançoisBlanchard (4 July 1753 – 7 March 1809) was a French inventor, best known as a pioneer of gas balloon flight, who distinguished himself in the conquest of the air in a balloon, in particular the first crossing of the Engli ...

fitted a hand-powered propeller to a balloon, the first recorded means of propulsion carried aloft. In 1785, he crossed the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

in a balloon equipped with flapping wings for propulsion and a birdlike tail for steering.

19th century

The 19th century saw continued attempts to add methods of propulsion to balloons. The Australian William Bland sent designs for his "Atomic Airship" to the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851, where a model was displayed. This was an elongated balloon with a steam engine driving twin propellers suspended underneath. The lift of the balloon was estimated as 5 tons and the car with the fuel as weighing 3.5 tons, giving a payload of 1.5 tons. Bland believed that the machine could be driven at and could fly from Sydney to London in less than a week. In 1852, Henri Giffard became the first person to make an engine-powered flight when he flew in a steam-powered airship. Airships would develop considerably over the next two decades. In 1863, Solomon Andrews flew his aereon design, an unpowered, controllable dirigible in Perth Amboy, New Jersey and offered the device to the U.S. Military during the Civil War. He flew a later design in 1866 around New York City and as far as Oyster Bay, New York. This concept used changes in lift to provide propulsive force, and did not need a powerplant. In 1872, the French naval architect Dupuy de Lome launched a large navigable balloon, which was driven by a large propeller turned by eight men. It was developed during the Franco-Prussian war and was intended as an improvement to the balloons used for communications between Paris and the countryside during the siege of Paris, but was completed only after the end of the war. In 1872,Paul Haenlein

Paul Haenlein (17 October 1835 in Cologne – 27 January 1905 in Mainz) was a German engineer and flight pioneer. He flew in a semi-rigid-frame dirigible. His family belonged to the ''Citoyens notables'', those notabilities who led the econom ...

flew an airship with an internal combustion engine running on the coal gas used to inflate the envelope, the first use of such an engine to power an aircraft.Bento S. MattosShort History of Brazilian Aeronautics

(PDF), 44th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada, 9–12 January 2006.

Charles F. Ritchel

Charles Frances Ritchel (December 22, 1844 – January 21, 1911) was an American inventor of a successful dirigible design, the fun house mirror, a mechanical toy bank, and the holder of more than 150 other patented inventions.

Biography

Charl ...

made a public demonstration flight in 1878 of his hand-powered one-man rigid airship, and went on to build and sell five of his aircraft.

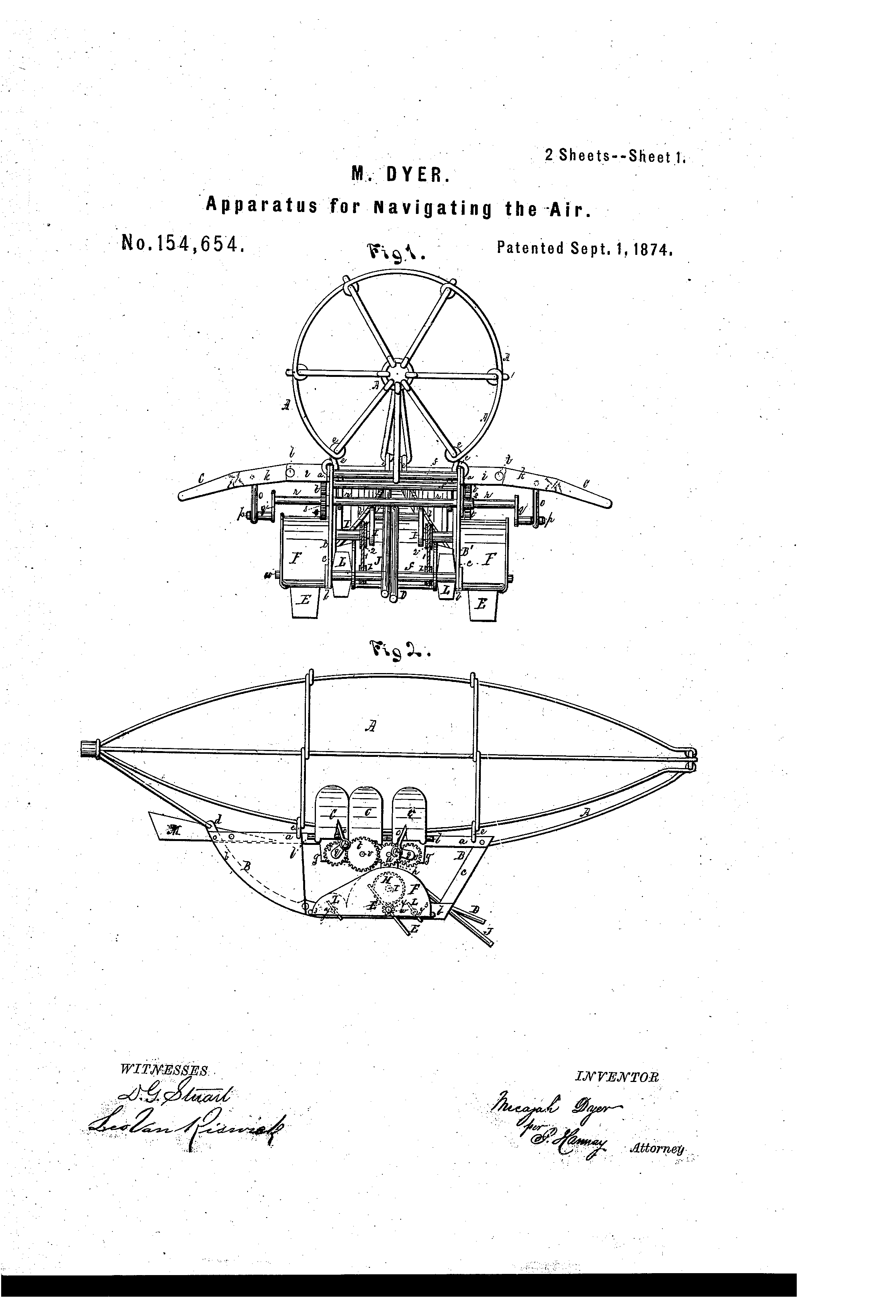

In 1874,

In 1874, Micajah Clark Dyer Micajah is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

People

* Micajah Autry (1794–1836), American merchant, poet and lawyer who died in the Texas Revolution at the Battle of the Alamo

* Micajah Burnett (1791–1879), American Shaker a ...

filed U.S. Patent 154,654 "Apparatus for Navigating the Air". It is believed successful trial flights were made between 1872–1874, but detailed dates are not available. The apparatus used a combination of wings and paddle wheels for navigation and propulsion.

More details can be found in the book about his life.

In 1883, the first electric-powered flight was made by Gaston Tissandier

Gaston Tissandier (November 21, 1843 – August 30, 1899) was a French chemist, meteorologist, aviator, and editor. He escaped besieged Paris by balloon in September 1870. He founded and edited the scientific magazine ''La Nature'' and wrote s ...

, who fitted a Siemens

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

The principal divisions of the corporation are ''Industry'', ''E ...

electric motor to an airship.

The first fully controllable free flight was made in 1884 by Charles Renard

Charles Renard (1847–1905) born in Damblain, Vosges, was a French military engineer.

Airships

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 he started work on the design of airships at the French army aeronautical department. Together with A ...

and Arthur Constantin Krebs in the French Army

History

Early history

The first permanent army, paid with regular wages, instead of feudal levies, was established under Charles VII of France, Charles VII in the 1420 to 1430s. The Kings of France needed reliable troops during and after the ...

airship '' La France''. La France made the first flight of an airship that landed where it took off; the long, airship covered in 23 minutes with the aid of an electric motor, and a battery. It made seven flights in 1884 and 1885.

In 1888, the design of the Campbell Air Ship, designed by Professor Peter C. Campbell, was submitted to aeronautic engineer Carl Edgar Myers

Carl Edgar Myers ( – ) was an American businessman, scientist, inventor, meteorologist, balloonist, and aeronautical engineer. He invented many types of hydrogen balloon airships and related equipment. His business of making passenger airshipb ...

for examination. After his approval it was built by the Novelty Air Ship Company. It was lost at sea in 1889 while being flown by Professor Hogan during an exhibition flight.

From 1888 to 1897, Friedrich Wölfert built three airships powered by Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft

Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (abbreviated as DMG, also known as ''Daimler Motors Corporation'') was a German engineering company and later automobile manufacturer, in operation from 1890 until 1926. Founded by Gottlieb Daimler (1834–1900) and ...

-built petrol engines, the last of which caught fire in flight and killed both occupants in 1897. The 1888 version used a single cylinder Daimler engine and flew from Canstatt

Bad Cannstatt, also called Cannstatt (until July 23, 1933) or Kannstadt (until 1900), is one of the outer stadtbezirke, or city boroughs, of Stuttgart in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Bad Cannstatt is the oldest and most populous of Stuttgart's bo ...

to Kornwestheim

Kornwestheim ( Swabian: ) is a town in the district of Ludwigsburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated about north of Stuttgart, and south of Ludwigsburg.

History

Origins and Development

Kornwestheim can look back at a history ...

.

In 1897, an airship with an aluminum envelope was built by the Hungarian- Croatian engineer David Schwarz. It made its first flight at Tempelhof field in Berlin after Schwarz had died. His widow, Melanie Schwarz, was paid 15,000 marks by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin to release the industrialist Carl Berg from his exclusive contract to supply Schwartz with

In 1897, an airship with an aluminum envelope was built by the Hungarian- Croatian engineer David Schwarz. It made its first flight at Tempelhof field in Berlin after Schwarz had died. His widow, Melanie Schwarz, was paid 15,000 marks by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin to release the industrialist Carl Berg from his exclusive contract to supply Schwartz with aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It ha ...

.

From 1897 to 1899, Konstantin Danilewsky, medical doctor and inventor from Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

(now Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, then Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

), built four muscle-powered airships, of gas volume . About 200 ascents were made within a framework of experimental flight program, at two locations, with no significant incidents.

Early 20th century

In July 1900, the Luftschiff

In July 1900, the Luftschiff Zeppelin LZ1

The Zeppelin ''LZ 1'' was the first successful experimental rigid airship. It was first flown from a floating hangar on Lake Constance, near Friedrichshafen in southern Germany, on 2 July 1900.Lueger, Otto: Lexikon der gesamten Technik und ihre ...

made its first flight. This led to the most successful airships of all time: the Zeppelins, named after Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin who began working on rigid airship designs in the 1890s, leading to the flawed LZ1 in 1900 and the more successful LZ2 in 1906. The Zeppelin airships had a framework composed of triangular lattice girders covered with fabric that contained separate gas cells. At first multiplane tail surfaces were used for control and stability: later designs had simpler cruciform tail __NOTOC__

The cruciform tail is an aircraft empennage configuration which, when viewed from the aircraft's front or rear, looks much like a cross. The usual arrangement is to have the horizontal stabilizer intersect the vertical tail somewhere ...

surfaces. The engines and crew were accommodated in "gondolas" hung beneath the hull driving propellers attached to the sides of the frame by means of long drive shafts. Additionally, there was a passenger compartment (later a bomb bay

The bomb bay or weapons bay on some military aircraft is a compartment to carry bombs, usually in the aircraft's fuselage, with "bomb bay doors" which open at the bottom. The bomb bay doors are opened and the bombs are dropped when over t ...

) located halfway between the two engine compartments.

Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont ( Palmira, 20 July 1873 — Guarujá, 23 July 1932) was a Brazilian aeronaut, sportsman, inventor, and one of the few people to have contributed significantly to the early development of both lighter-than-air and heavie ...

was a wealthy young Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

ian who lived in France and had a passion for flying. He designed 18 balloons and dirigibles before turning his attention to fixed-winged aircraft.

On 19 October 1901 he flew his airship '' Number 6'', from the Parc Saint Cloud to and around the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed ...

and back in under thirty minutes. This feat earned him the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize of 100,000 franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

s. Many inventors were inspired by Santos-Dumont's small airships. Many airship pioneers, such as the American Thomas Scott Baldwin

Thomas Scott Baldwin (June 30, 1854 – May 17, 1923) was a pioneer balloonist and U.S. Army major during World War I. He was the first American to descend from a balloon by parachute.

Early career

Thomas Scott Baldwin was born on June 30, 185 ...

, financed their activities through passenger flights and public demonstration flights. Stanley Spencer

Sir Stanley Spencer, CBE RA (30 June 1891 – 14 December 1959) was an English painter. Shortly after leaving the Slade School of Art, Spencer became well known for his paintings depicting Biblical scenes occurring as if in Cookham, the sma ...

built the first British airship with funds from advertising baby food on the sides of the envelope.Papers Past – Christchurch Star, 31 December 1903, ''WAYS OF AIRSHIPS'' (p. 2)/ref> Others, such as

Walter Wellman

Walter E. Wellman (November 3, 1858 – January 31, 1934) was an American journalist, explorer, and aëronaut.

Biographical background

Walter Wellman was born in Mentor, Ohio, in 1858. He was the sixth son of Alonzo Wellman and the fourth by ...

and Melvin Vaniman, set their sights on loftier goals, attempting two polar flights in 1907 and 1909, and two trans-Atlantic flights in 1910 and 1912.

In 1902 the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo published details of an innovative airship design in Spain and France. With a non-rigid body and internal bracing wires, it overcame the flaws of these types of aircraft as regards both rigid structure (zeppelin type) and flexibility, providing the airships with more stability during flight, and the capability of using heavier engines and a greater passenger load. In 1905, helped by Captain A. Kindelán, he built the airship "España" at the

In 1902 the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo published details of an innovative airship design in Spain and France. With a non-rigid body and internal bracing wires, it overcame the flaws of these types of aircraft as regards both rigid structure (zeppelin type) and flexibility, providing the airships with more stability during flight, and the capability of using heavier engines and a greater passenger load. In 1905, helped by Captain A. Kindelán, he built the airship "España" at the Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Mexico, while the Guadalaj ...

military base. Next year he patented his design without attracting official interest. In 1909 he patented an improved design that he offered to the French Astra company, who started mass-producing it in 1911 as the Astra-Torres airship

The Astra-Torres airships were non-rigid airships built by Société Astra in France between about 1908 and 1922 to a design by the Spaniard Leonardo Torres Quevedo. They had a highly-characteristic tri-lobed cross-section rather than the more usu ...

. The distinctive three-lobed design was widely used during the Great War by the Entente powers. To find a resolution to the slew of problems faced by airship engineers to dock dirigibles, Torres y Quevedo also drew up designs of a ‘docking station’ and made alterations to airship designs. In 1910, Torres y Quevedo proposed the idea of attaching an airships nose to a mooring mast and allowing the airship to weathervane with changes of wind direction. The use of a metal column erected on the ground, the top of which the bow or stem would be directly attached to (by a cable) would allow a dirigible to be moored at any time, in the open, regardless of wind speeds. Additionally, Torres y Quevedo's design called for the improvement and accessibility of temporary landing sites, where airships were to be moored for the purpose of disembarkation of passengers. The final patent was presented in February 1911.

Other airship builders were also active before the war: from 1902 the French company Lebaudy Frères specialized in semirigid airships such as the '' Patrie'' and the '' République'', designed by their engineer Henri Julliot, who later worked for the American company Goodrich; the German firm Schütte-Lanz built the wooden-framed SL series from 1911, introducing important technical innovations; another German firm Luft-Fahrzeug-Gesellschaft built the '' Parseval-Luftschiff'' (PL) series from 1909, Lueger 1920, pp.404–412Luftschiff

/ref> and Italian Enrico Forlanini's firm had built and flown the first two

Forlanini airships

This is a complete list of Forlanini airships designed and built by the Italian pioneer Enrico Forlanini from 1900 to 1931 (posthumously). Lapini, Gian Luca These, like the German Groß-Basenach semi-rigid airships, were the first to have the gon ...

. Ligugnana, Sandro

On May 12, 1902, the inventor and Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

ian aeronaut Augusto Severo de Albuquerque Maranhao

Augusto is an Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish given name or surname. Notable people with the name include:

* Augusto Aníbal

*Augusto dos Anjos

* Augusto Arbizo

*Augusto Barbera (born 1938), Italian law professor, politician and judge

* Augusto B ...

and his French mechanic, Georges Saché, died when they were flying over Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in the airship called Pax. A marble plaque at number 81 of the Avenue du Maine in Paris, commemorates the location of Augusto Severo accident. The Catastrophe of the Balloon "Le Pax" is a 1902 short silent film recreation of the catastrophe, directed by Georges Méliès

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès (; ; 8 December 1861 – 21 January 1938) was a French illusionist, actor, and film director. He led many technical and narrative developments in the earliest days of cinema.

Méliès was well known for the use of ...

.

In Britain, the Army built their first dirigible, the ''Nulli Secundus'', in 1907. The Navy ordered the construction of an experimental rigid in 1908. Officially known as His Majesty's Airship No. 1 and nicknamed the ''Mayfly'', it broke its back in 1911 before making a single flight. Work on a successor did not start until 1913.

German airship passenger service known as DELAG

DELAG, acronym for ''Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft'' (German for "German Airship Travel Corporation"), was the world's first airline to use an aircraft in revenue service. It operated a fleet of zeppelin rigid airships manufacture ...

(Deutsche-Luftschiffahrts AG) was established in 1910.

In 1910 Walter Wellman

Walter E. Wellman (November 3, 1858 – January 31, 1934) was an American journalist, explorer, and aëronaut.

Biographical background

Walter Wellman was born in Mentor, Ohio, in 1858. He was the sixth son of Alonzo Wellman and the fourth by ...

unsuccessfully attempted an aerial crossing of the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

in the airship ''America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

''.

World War I

The prospect of airships as bombers had been recognized in Europe well before the airships were up to the task. H. G. Wells' ''The War in the Air

''The War in the Air: And Particularly How Mr. Bert Smallways Fared While It Lasted'' is a military science fiction novel written by H. G. Wells.

The novel was written in four months in 1907, and was serialized and published in 1908 in '' ...

'' (1908) described the obliteration of entire fleets and cities by airship attack. The Italian forces became the first to use dirigibles for a military purpose during the Italo–Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

, the first bombing mission being flown on 10 March 1912. World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

marked the airship's real debut as a weapon. The Germans, French, and Italians all used airships for scouting and tactical bombing roles early in the war, and all learned that the airship was too vulnerable for operations over the front. The decision to end operations in direct support of armies was made by all in 1917.

Many in the German military believed they had found the ideal weapon with which to counteract British naval superiority and strike at Britain itself, while more realistic airship advocates believed the zeppelin's value was as a long range scout/attack craft for naval operations. Raids on England began in January 1915 and peaked in 1916: following losses to the British defenses only a few raids were made in 1917–18, the last in August 1918. Zeppelins proved to be terrifying but inaccurate weapons. Navigation, target selection and bomb-aiming proved to be difficult under the best of conditions, and the cloud cover that was frequently encountered by the airships reduced accuracy even further. The physical damage done by airships over the course of the war was insignificant, and the deaths that they caused amounted to a few hundred. Nevertheless, the raid caused a significant diversion of British resources to defense efforts. The airships were initially immune to attack by aircraft and anti-aircraft guns: as the pressure in their envelopes was only just higher than ambient air, holes had little effect. But following the introduction of a combination of incendiary and explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

ammunition in 1916, their flammable hydrogen lifting gas made them vulnerable to the defending aeroplanes. Several were shot down in flames by British defenders, and many others destroyed in accidents. New designs capable of reaching greater altitude were developed, but although this made them immune from attack it made their bombing accuracy even worse.

Countermeasures by the British included sound detection equipment, searchlights and anti-aircraft artillery, followed by night fighters in 1915. One tactic used early in the war, when their limited range meant the airships had to fly from forward bases and the only zeppelin production facilities were in Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''K ...

, was the bombing of airship sheds by the British Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

. Later in the war, the development of the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

led to the first successful carrier-based air strike in history: on the morning of 19 July 1918, seven Sopwith 2F.1 Camels were launched from and struck the airship base at Tønder, destroying zeppelins L 54 and L 60.

fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

s without the wing and tail surfaces as control cars. Later, more advanced blimps with purpose-built gondolas were used. The NS class (North Sea) were the largest and most effective non-rigid airships in British service, with a gas capacity of , a crew of 10 and an endurance of 24 hours. Six bombs were carried, as well as three to five machine guns. British blimps were used for scouting, mine clearance, and convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

patrol duties. During the war, the British operated over 200 non-rigid airships. Several were sold to Russia, France, the United States, and Italy. The large number of trained crews, low attrition rate and constant experimentation in handling techniques meant that at the war's end Britain was the world leader in non-rigid airship technology.

The Royal Navy continued development of rigid airships until the end of the war. Eight rigid airships had been completed by the armistice, (No. 9r

HMA ''No. 9r'' was a rigid airship designed and built by Vickers at Walney Island just off Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria. It was ordered in 1913 but did not fly until 27 November 1916 when it became the first British rigid airship to do so. It w ...

, four 23 Class, two R23X Class and one R31 Class), although several more were in an advanced state of completion by the war's end. Both France and Italy continued to use airships throughout the war. France preferred the non-rigid type, whereas Italy flew 49 semi-rigid airships in both the scouting and bombing roles.

Aeroplanes had essentially replaced airships as bombers by the end of the war, and Germany's remaining zeppelins were destroyed by their crews, scrapped or handed over to the Allied powers as war reparations. The British rigid airship program, which had mainly been a reaction to the potential threat of the German airships, was wound down.

The interwar period

Britain, the United States and Germany built rigid airships between the two world wars. Italy and France made limited use of Zeppelins handed over as war reparations. Italy, the Soviet Union, the United States and Japan mainly operated semi-rigid airships.

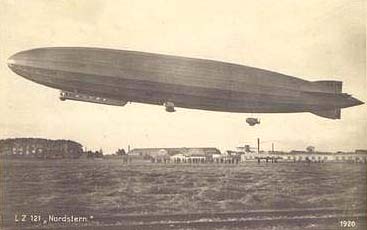

Under the terms of the

Britain, the United States and Germany built rigid airships between the two world wars. Italy and France made limited use of Zeppelins handed over as war reparations. Italy, the Soviet Union, the United States and Japan mainly operated semi-rigid airships.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, Germany was not allowed to build airships of greater capacity than a million cubic feet. Two small passenger airships, LZ 120 ''Bodensee'' and its sister ship LZ 121 ''Nordstern'', were built immediately after the war but were confiscated following the sabotage of the wartime Zeppelins that were to have been handed over as war reparations: ''Bodensee'' was given to Italy and ''Nordstern'' to France. On May 12, 1926, the Italian built semi-rigid airship ''Norge

Norge is Norwegian (bokmål), Danish and Swedish for Norway.

It may also refer to:

People

* Kaare Norge (born 1963), Danish guitarist

* Norge Luis Vera (born 1971), Cuban baseball player

Places

* 11871 Norge, asteroid

Toponyms:

*Norge, Okla ...

'' was the first aircraft to fly over the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

.

The British R33 and R34 were near-identical copies of the German L 33, which had come down almost intact in Yorkshire on 24 September 1916. Despite being almost three years out of date by the time they were launched in 1919, they became two of the most successful airships in British service. The creation of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) in early 1918 created a hybrid British airship program. The RAF was not interested in airships while the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

was, so a deal was made where the Admiralty would design any future military airships and the RAF would handle manpower, facilities and operations.Higham (1961), p. 176. On 2 July 1919, R34 began the first double crossing of the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

by an aircraft. It landed at Mineola, Long Island

Mineola is a village in and the county seat of Nassau County, on Long Island, in New York, United States. The population was 18,799 at the 2010 census. The name is derived from an Algonquin Chief, Miniolagamika, which means "pleasant village".

...

on 6 July after 108 hours in the air; the return crossing began on 8 July and took 75 hours. This feat failed to generate enthusiasm for continued airship development, and the British airship program was rapidly wound down.

During World War One, the U.S. Navy acquired its first airship, the DH-1, but it was destroyed while being inflated shortly after delivery to the Navy. After the war, the U.S. Navy contracted to buy the R 38, which was being built in Britain, but before it was handed over it was destroyed because of a structural failure during a test flight.

America then started constructing the , designed by the

America then started constructing the , designed by the Bureau of Aeronautics

The Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) was the U.S. Navy's material-support organization for naval aviation from 1921 to 1959. The bureau had "cognizance" (''i.e.'', responsibility) for the design, procurement, and support of naval aircraft and relate ...

and based on the Zeppelin L 49. Assembled in Hangar No. 1 and first flown on 4 September 1923 at Lakehurst, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

, it was the first airship to be inflated with the noble gas

The noble gases (historically also the inert gases; sometimes referred to as aerogens) make up a class of chemical elements with similar properties; under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases with very low ch ...

helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic ta ...

, which was then so scarce that the ''Shenandoah'' contained most of the world's supply. A second airship, , was built by the Zeppelin company as compensation for the airships that should have been handed over as war reparations according to the terms of the Versailles Treaty but had been sabotaged by their crews. This construction order saved the Zeppelin works from the threat of closure. The success of the ''Los Angeles'', which was flown successfully for eight years, encouraged the U.S. Navy to invest in its own, larger airships. When the ''Los Angeles'' was delivered, the two airships had to share the limited supply of helium, and thus alternated operating and overhauls.

In 1922, Sir Dennistoun Burney suggested a plan for a subsidised air service throughout the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

using airships (the Burney Scheme). Following the coming to power of Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

's Labour government in 1924, the scheme was transformed into the Imperial Airship Scheme

The British Imperial Airship Scheme was a 1920s project to improve communication between Britain and the distant countries of the British Empire by establishing air routes using airships. The first phase was the construction of two large and t ...

, under which two airships were built, one by a private company and the other by the Royal Airship Works

Cardington Airfield, previously RAF Cardington, is a former Royal Air Force station in Bedfordshire, England, with a long and varied history, particularly in relation to airships and balloons.

Most of the former RAF station is in the parish o ...

under Air Ministry control. The two designs were radically different. The "capitalist" ship, the '' R100'', was more conventional, while the "socialist" ship, the R101

R101 was one of a pair of British rigid airships completed in 1929 as part of a British government programme to develop civil airships capable of service on long-distance routes within the British Empire. It was designed and built by an Air M ...

, had many innovative design features. Construction of both took longer than expected, and the airships did not fly until 1929. Neither airship was capable of the service intended, though the R100 did complete a proving flight to Canada and back in 1930. On 5 October 1930, the R101, which had not been thoroughly tested after major modifications, crashed on its maiden voyage to India at Beauvais in France killing 48 of the 54 people aboard. Among the dead were the craft's chief designer and the Secretary of State for Air. The disaster ended British interest in airships.

The Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties were seven agreements negotiated at Locarno, Switzerland, during 5 to 16 October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central a ...

of 1925 lifted the restrictions on German airship construction, and the Zeppelin company started construction of the ''Graf Zeppelin'' (LZ 127), the largest airship that could be built in the company's existing shed, and intended to stimulate interest in passenger airships. The ''Graf Zeppelin'' burned ''blau gas

Blau gas (german: Blaugas) is an artificial illuminating gas, similar to propane, named after its inventor, Hermann Blau of Augsburg, Germany. Not or rarely used or produced today, it was manufactured by decomposing mineral oils in retorts by ...

'', similar to propane

Propane () is a three-carbon alkane with the molecular formula . It is a gas at standard temperature and pressure, but compressible to a transportable liquid. A by-product of natural gas processing and petroleum refining, it is commonly used as ...

, stored in large gas bags below the hydrogen cells, as fuel. Since its density was similar to that of air, it avoided the weight change as fuel was used, and thus the need to valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fitting ...

hydrogen. The ''Graf Zeppelin'' had an impressive safety record, flying over (including the first circumnavigation of the globe by airship) without a single passenger injury.  The U.S. Navy experimented with the use of airships as airborne aircraft carriers, developing an idea pioneered by the British. The USS ''Los Angeles'' was used for initial experiments, and the and , the world's largest at the time, were used to test the principle in naval operations. Each carried four F9C Sparrowhawk

The U.S. Navy experimented with the use of airships as airborne aircraft carriers, developing an idea pioneered by the British. The USS ''Los Angeles'' was used for initial experiments, and the and , the world's largest at the time, were used to test the principle in naval operations. Each carried four F9C Sparrowhawk fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

in its hangar, and could carry a fifth on the trapeze. The idea had mixed results. By the time the Navy started to develop a sound doctrine for using the ZRS-type airships, the last of the two built, USS ''Macon'', had been wrecked. Meanwhile, the seaplane had become more capable, and was considered a better investment.

Eventually, the U.S. Navy lost all three U.S.-built rigid airships to accidents. USS ''Shenandoah'' flew into a severe thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorms are somet ...

over Noble County, Ohio

Noble County is a county located in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,115, making it the fourth-least populous county in Ohio. Its county seat is Caldwell. The county is named for Rep. Warren P. Noble of the ...

while on a poorly planned publicity flight on 3 September 1925. It broke into pieces, killing 14 of its crew. USS ''Akron'' was caught in a severe storm and flown into the surface of the sea off the shore of New Jersey on 3 April 1933. It carried no life boats and few life vests, so 73 of its crew of 76 died from drowning or hypothermia. USS ''Macon'' was lost after suffering a structural failure offshore near Point Sur Lighthouse

Point Sur Lighthouse is a lightstation at Point Sur south of Monterey, California at the peak of the rock at the head of the point. It was established in 1889 and is part of Point Sur State Historic Park. The light house is tall and above ...

on 12 February 1935. The failure caused a loss of gas, which was made much worse when the aircraft was driven over pressure height causing it to lose too much helium to maintain flight. Only two of its crew of 83 died in the crash thanks to the inclusion of life jackets and inflatable rafts after the ''Akron'' disaster.

The Empire State Building

The Empire State Building is a 102-story Art Deco skyscraper in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The building was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and built from 1930 to 1931. Its name is derived from " Empire State", the nickname of the ...

was completed in 1931 with a dirigible mast, in anticipation of future passenger airship service, but no airship ever used the mast. Various entrepreneurs experimented with commuting and shipping freight via airship.

In the 1930s, the German Zeppelins successfully competed with other means of transport. They could carry significantly more passengers than other contemporary aircraft while providing amenities similar to those on ocean liners, such as private cabins, observation decks, and dining rooms. Less importantly, the technology was potentially more energy-efficient than heavier-than-air designs. Zeppelins were also faster than ocean liners. On the other hand, operating airships was quite involved. Often the crew would outnumber passengers, and on the ground large teams were necessary to assist mooring and very large hangars were required at airports.

By the mid-1930s, only Germany still pursued airship development. The Zeppelin company continued to operate the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on passenger service between Frankfurt and

By the mid-1930s, only Germany still pursued airship development. The Zeppelin company continued to operate the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on passenger service between Frankfurt and Recife

That it may shine on all (Matthew 5:15)

, image_map = Brazil Pernambuco Recife location map.svg

, mapsize = 250px

, map_caption = Location in the state of Pernambuco

, pushpin_map = Brazil#South Am ...

in Brazil, taking 68 hours. Even with the small ''Graf Zeppelin'', the operation was almost profitable. In the mid-1930s, work began on an airship designed specifically to operate a passenger service across the Atlantic. The ''Hindenburg'' (LZ 129) completed a successful 1936 season, carrying passengers between Lakehurst, New Jersey

Lakehurst is a borough in Ocean County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the borough's population was 2,654,mooring mast

A mooring mast, or mooring tower, is a structure designed to allow for the docking of an airship outside of an airship hangar or similar structure. More specifically, a mooring mast is a mast or tower that contains a fitting on its top that allo ...

minutes before landing on 6 May 1937, the ''Hindenburg'' suddenly burst into flames and crashed to the ground. Of the 97 people aboard, 35 died: 13 passengers, 22 aircrew, along with one American ground-crewman. The disaster happened before a large crowd, was filmed and a radio news reporter was recording the arrival. This was a disaster that theater goers could see and hear in newsreels

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a cinema, newsreels were a source of current affairs, inform ...

. The ''Hindenburg'' disaster shattered public confidence in airships, and brought a definitive end to their "golden age". The day after the ''Hindenburg'' disaster, the ''Graf Zeppelin'' landed safely in Germany after its return flight from Brazil. This was the last international passenger airship flight.

''Hindenburg''s identical sister ship, the ''Graf Zeppelin II'' (LZ 130), could not carry commercial passengers without helium, which the United States refused to sell to Germany. The ''Graf Zeppelin'' made several test flights and conducted some electronic espionage until 1939 when it was grounded due to the beginning of the war. The two ''Graf Zeppelins'' were scrapped in April, 1940.

Development of airships continued only in the United States, and to a lesser extent, the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union had several semi-rigid and non-rigid airships. The semi-rigid dirigible SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM

SSSR-V6 ''OSOAVIAKhIM'' (russian: СССР-В6 Осоавиахим) was a semi-rigid airship designed by Italian engineer and airship designer Umberto Nobile and constructed as a part of the Soviet airship program. The airship was named after th ...

was among the largest of these craft, and it set the longest endurance flight at the time of over 130 hours. It crashed into a mountain in 1938, killing 13 of the 19 people on board. While this was a severe blow to the Soviet airship program, they continued to operate non-rigid airships until 1950.

World War II

While Germany determined that airships were obsolete for military purposes in the coming war and concentrated on the development of aeroplanes, the United States pursued a program of military airship construction even though it had not developed a clearmilitary doctrine

Military doctrine is the expression of how military forces contribute to campaigns, major operations, battles, and engagements.

It is a guide to action, rather than being hard and fast rules. Doctrine provides a common frame of reference acros ...

for airship use. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, bringing the United States into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the U.S. Navy had 10 nonrigid airships:

*4 ''K''-class: ''K-2'', ''K-3'', ''K-4'' and ''K-5'' designed as patrol ships, all built in 1938.

*3 ''L''-class: ''L-1'', ''L-2'' and ''L-3'' as small training ships, produced in 1938.

*1 ''G''-class, built in 1936 for training.

*2 ''TC''-class that were older patrol airships designed for land forces, built in 1933. The U.S. Navy acquired both from the United States Army in 1938.

Only ''K''- and ''TC''-class airships were suitable for combat and they were quickly pressed into service against Japanese and German

Only ''K''- and ''TC''-class airships were suitable for combat and they were quickly pressed into service against Japanese and German submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, which were then sinking American shipping within visual range of the American coast. U.S. Navy command, remembering airship's anti-submarine success in World War I, immediately requested new modern antisubmarine airships and on 2 January 1942 formed the ZP-12 patrol unit based in Lakehurst from the four ''K'' airships. The ZP-32 patrol unit was formed from two ''TC'' and two ''L'' airships a month later, based at NAS Moffett Field

Moffett Federal Airfield , also known as Moffett Field, is a joint civil-military airport located in an unincorporated part of Santa Clara County, California, United States, between northern Mountain View and northern Sunnyvale. On November 10, ...

in Sunnyvale, California

Sunnyvale () is a city located in the Santa Clara Valley in northwest Santa Clara County in the U.S. state of California.

Sunnyvale lies along the historic El Camino Real and Highway 101 and is bordered by portions of San Jose to the nor ...

. An airship training base was created there as well. The status of submarine-hunting Goodyear airships in the early days of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

has created significant confusion. Although various accounts refer to airships ''Resolute'' and ''Volunteer'' as operating as "privateers" under a Letter of Marque, Congress never authorized a commission, nor did the President sign one.

In the years 1942–44, approximately 1,400 airship pilots and 3,000 support crew members were trained in the military airship crew training program and the airship military personnel grew from 430 to 12,400. The U.S. airships were produced by the Goodyear factory in

In the years 1942–44, approximately 1,400 airship pilots and 3,000 support crew members were trained in the military airship crew training program and the airship military personnel grew from 430 to 12,400. The U.S. airships were produced by the Goodyear factory in Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 Census, the city ...