deep water cycle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

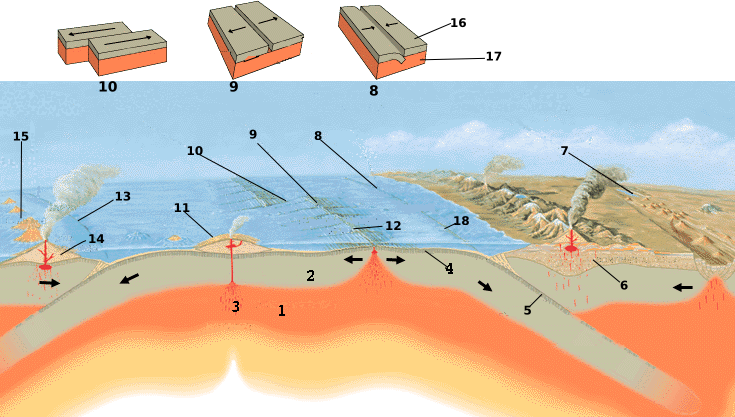

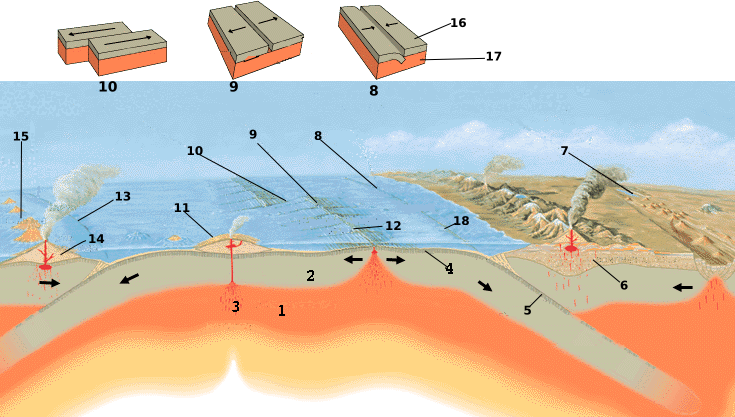

The deep water cycle, or geologic water cycle, involves exchange of water with the mantle, with water carried down by

Water is not just present as a separate phase in the ground. Seawater percolates into oceanic crust and

Water is not just present as a separate phase in the ground. Seawater percolates into oceanic crust and

An upper bound on the amount of water in the mantle can be obtained by considering the amount of water that can be carried by its minerals (their ''storage capacity''). This depends on temperature and pressure. There is a steep temperature gradient in the lithosphere where heat travels by conduction, but in the mantle the rock is stirred by convection and the temperature increases more slowly (see figure). Descending slabs have colder than average temperatures.

An upper bound on the amount of water in the mantle can be obtained by considering the amount of water that can be carried by its minerals (their ''storage capacity''). This depends on temperature and pressure. There is a steep temperature gradient in the lithosphere where heat travels by conduction, but in the mantle the rock is stirred by convection and the temperature increases more slowly (see figure). Descending slabs have colder than average temperatures.

The mantle can be divided into the upper mantle (above 410 km depth), transition zone (between 410 km and 660 km), and the lower mantle (below 660 km). Much of the mantle consists of olivine and its high-pressure polymorphs. At the top of the transition zone, it undergoes a

The mantle can be divided into the upper mantle (above 410 km depth), transition zone (between 410 km and 660 km), and the lower mantle (below 660 km). Much of the mantle consists of olivine and its high-pressure polymorphs. At the top of the transition zone, it undergoes a

Mineral samples from the transition zone and lower mantle come from inclusions found in

Mineral samples from the transition zone and lower mantle come from inclusions found in

subducting

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

oceanic plates and returning through volcanic activity, distinct from the water cycle

The water cycle, also known as the hydrologic cycle or the hydrological cycle, is a biogeochemical cycle that describes the continuous movement of water on, above and below the surface of the Earth. The mass of water on Earth remains fairly const ...

process that occurs above and on the surface of Earth. Some of the water makes it all the way to the lower mantle

The lower mantle, historically also known as the mesosphere, represents approximately 56% of Earth's total volume, and is the region from 660 to 2900 km below Earth's surface; between the transition zone and the outer core. The preliminary ...

and may even reach the outer core

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. The outer core begins approximately beneath Earth's surface at the core-mantle boundary and e ...

. Mineral physics experiments show that hydrous minerals can carry water deep into the mantle in colder slabs and even "nominally anhydrous minerals" can store several oceans' worth of water.

The process of deep water recycling involves water entering the mantle by being carried down by subducting oceanic plates (a process known as regassing) being balanced by water being released at mid-ocean ridges (degassing). This is a central concept in the understanding of the long‐term exchange of water between the earth's interior and the exosphere

The exosphere ( grc, ἔξω "outside, external, beyond", grc, σφαῖρα "sphere") is a thin, atmosphere-like volume surrounding a planet or natural satellite where molecules are gravitationally bound to that body, but where the densit ...

and the transport of water bound in hydrous minerals.

Introduction

In the conventional view of the water cycle (also known as the ''hydrologic cycle''), water moves between reservoirs in theatmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

and Earth's surface or near-surface (including the ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wor ...

, river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of wat ...

s and lake

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much larger ...

s, glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

s and polar ice cap

A polar ice cap or polar cap is a high-latitude region of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite that is covered in ice.

There are no requirements with respect to size or composition for a body of ice to be termed a polar ice cap, nor a ...

s, the biosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be ...

and groundwater). However, in addition to the surface cycle, water also plays an important role in geological processes reaching down into the crust and mantle. Water content in magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural s ...

determines how explosive a volcanic eruption is; hot water is the main conduit for economically important minerals to concentrate in hydrothermal mineral deposits; and water plays an important role in the formation and migration of petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

.

Water is not just present as a separate phase in the ground. Seawater percolates into oceanic crust and

Water is not just present as a separate phase in the ground. Seawater percolates into oceanic crust and hydrates

In chemistry, a hydrate is a substance that contains water or its constituent elements. The chemical state of the water varies widely between different classes of hydrates, some of which were so labeled before their chemical structure was underst ...

igneous rocks such as olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers quickl ...

and pyroxene

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated to ''Px'') are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe II) ...

, transforming them into hydrous minerals such as serpentines, talc

Talc, or talcum, is a clay mineral, composed of hydrated magnesium silicate with the chemical formula Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Talc in powdered form, often combined with corn starch, is used as baby powder. This mineral is used as a thickening agent ...

and brucite

Brucite is the mineral form of magnesium hydroxide, with the chemical formula Mg( OH)2. It is a common alteration product of periclase in marble; a low-temperature hydrothermal vein mineral in metamorphosed limestones and chlorite schists; and ...

. In this form, water is carried down into the mantle. In the upper mantle

The upper mantle of Earth is a very thick layer of rock inside the planet, which begins just beneath the crust (at about under the oceans and about under the continents) and ends at the top of the lower mantle at . Temperatures range from appro ...

, heat and pressure dehydrates these minerals, releasing much of it to the overlying mantle wedge

A mantle wedge is a triangular shaped piece of mantle that lies above a subducting tectonic plate and below the overriding plate. This piece of mantle can be identified using seismic velocity imaging as well as earthquake maps. Subducting oceanic ...

, triggering the melting of rock that rises to form volcanic arc

A volcanic arc (also known as a magmatic arc) is a belt of volcanoes formed above a subducting oceanic tectonic plate,

with the belt arranged in an arc shape as seen from above. Volcanic arcs typically parallel an oceanic trench, with the arc lo ...

s. However, some of the "nominally anhydrous minerals" that are stable deeper in the mantle can store small concentrations of water in the form of hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy g ...

(OH−), and because they occupy large volumes of the Earth, they are capable of storing at least as much as the world's oceans.

The conventional view of the ocean's origin is that it was filled by outgassing from the mantle in the early Archean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth during the Archea ...

and the mantle has remained dehydrated ever since. However, subduction carries water down at a rate that would empty the ocean in 1–2 billion years. Despite this, changes in the global sea level over the past 3–4 billion years have only been a few hundred metres, much smaller than the average ocean depth of 4 kilometres. Thus, the fluxes of water into and out of the mantle are expected to be roughly balanced, and the water content of the mantle steady. Water carried into the mantle eventually returns to the surface in eruptions at mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a diver ...

s and hotspots

Hotspot, Hot Spot or Hot spot may refer to:

Places

* Hot Spot, Kentucky, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Hot Spot (comics), a name for the DC Comics character Isaiah Crockett

* Hot Spot (T ...

. This circulation of water into the mantle and back is known as the ''deep water cycle'' or the ''geologic water cycle''. In .

Estimates of the amount of water in the mantle range from to 4 times the water in the ocean. There are 1.37×1018 m3 of water in the seas, therefore, this would suggest that there is between 3.4×1017 and 5.5×1018 m3 of water in the mantle. Constraints on water in the mantle come from mantle mineralogy, samples of rock from the mantle, and geophysical probes.

Storage capacity

An upper bound on the amount of water in the mantle can be obtained by considering the amount of water that can be carried by its minerals (their ''storage capacity''). This depends on temperature and pressure. There is a steep temperature gradient in the lithosphere where heat travels by conduction, but in the mantle the rock is stirred by convection and the temperature increases more slowly (see figure). Descending slabs have colder than average temperatures.

An upper bound on the amount of water in the mantle can be obtained by considering the amount of water that can be carried by its minerals (their ''storage capacity''). This depends on temperature and pressure. There is a steep temperature gradient in the lithosphere where heat travels by conduction, but in the mantle the rock is stirred by convection and the temperature increases more slowly (see figure). Descending slabs have colder than average temperatures.

The mantle can be divided into the upper mantle (above 410 km depth), transition zone (between 410 km and 660 km), and the lower mantle (below 660 km). Much of the mantle consists of olivine and its high-pressure polymorphs. At the top of the transition zone, it undergoes a

The mantle can be divided into the upper mantle (above 410 km depth), transition zone (between 410 km and 660 km), and the lower mantle (below 660 km). Much of the mantle consists of olivine and its high-pressure polymorphs. At the top of the transition zone, it undergoes a phase transition

In chemistry, thermodynamics, and other related fields, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic states o ...

to wadsleyite

Wadsleyite is an orthorhombic mineral with the formula β-(Mg,Fe)2SiO4. It was first found in nature in the Peace River meteorite from Alberta, Canada. It is formed by a phase transformation from olivine (α-(Mg,Fe)2SiO4) under increasing pressu ...

, and at about 520 km depth, wadsleyite transforms into ringwoodite

Ringwoodite is a high-pressure phase of Mg2SiO4 (magnesium silicate) formed at high temperatures and pressures of the Earth's mantle between depth. It may also contain iron and hydrogen. It is polymorphous with the olivine phase forsterite (a m ...

, which has the spinel

Spinel () is the magnesium/aluminium member of the larger spinel group of minerals. It has the formula in the cubic crystal system. Its name comes from the Latin word , which means ''spine'' in reference to its pointed crystals.

Properties

S ...

structure. At the top of the lower mantle, ringwoodite decomposes into bridgmanite

Silicate perovskite is either (the magnesium end-member is called bridgmanite) or (calcium silicate known as davemaoite) when arranged in a perovskite structure. Silicate perovskites are not stable at Earth's surface, and mainly exist in the low ...

and ferropericlase

Ferropericlase or magnesiowüstite is a magnesium/iron oxide with the chemical formula that is interpreted to be one of the main constituents of the Earth's lower mantle together with the silicate perovskite (), a magnesium/iron silicate with a ...

.

The most common mineral in the upper mantle is olivine. For a depth of 410 km, an early estimate of 0.13 percentage of water by weight (wt%) was revised upwards to 0.4 wt% and then to 1 wt%. However, the carrying capacity decreases dramatically towards the top of the mantle. Another common mineral, pyroxene, also has an estimated capacity of 1 wt% near 410 km.

In the transition zone, water is carried by wadsleyite and ringwoodite; in the relatively cold conditions of a descending slab, they can carry up to 3 wt%, while in the warmer temperatures of the surrounding mantle their storage capacity is about 0.5 wt%. The transition zone is also composed of at least 40% majorite

Majorite is a type of garnet mineral found in the mantle of the Earth. Its chemical formula is Mg3(MgSi)(SiO4)3. It is distinguished from other garnets in having Si in octahedral as well as tetrahedral coordination. Majorite was first described ...

, a high pressure phase of garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

All species of garnets possess similar physical properties and crystal forms, but differ in chemical composition. The different sp ...

; this only has capacity of 0.1 wt% or less.

The storage capacity of the lower mantle is a subject of controversy, with estimates ranging from the equivalent of 3 times to less than 3% of the ocean. Experiments have been limited to pressures found in the top 100 km of the mantle and are challenging to perform. Results may be biased upwards by hydrous mineral inclusions and downwards by a failure to maintain fluid saturation.

At high pressures, water can interact with pure iron to get FeH and FeO. Models of the outer core

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. The outer core begins approximately beneath Earth's surface at the core-mantle boundary and e ...

predict that it could hold as much as 100 oceans of water in this form, and this reaction may have dried out the lower mantle in the early history of Earth.

Water from the mantle

The carrying capacity of the mantle is only an upper bound, and there is no compelling reason to suppose that the mantle is saturated. Further constraints on the quantity and distribution of water in the mantle comes from a geochemical analysis of erupted basalts and xenoliths from the mantle.Basalts

Basalts formed atmid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a diver ...

s and hotspots originate in the mantle and are used to provide information on the composition of the mantle. Magma rising to the surface may undergo fractional crystallization Fractional crystallization may refer to:

* Fractional crystallization (chemistry), a process to separate different solutes from a solution

* Fractional crystallization (geology)

Fractional crystallization, or crystal fractionation, is one of the ...

in which components with higher melting points settle out first, and the resulting melts can have widely varying water contents; but when little separation has occurred, the water content is between about 0.07–0.6 wt%. (By comparison, basalts in back-arc basin

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic basin, found at some convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found in the western Pacific Ocean. Most of ...

s around volcanic arcs have between 1 wt% and 2.9 wt% because of the water coming off the subducting plate.)

Mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORBs) are commonly classified by the abundance of trace element

__NOTOC__

A trace element, also called minor element, is a chemical element whose concentration (or other measure of amount) is very low (a "trace amount"). They are classified into two groups: essential and non-essential. Essential trace elements ...

s that are incompatible with the minerals they inhabit. They are divided into "normal" MORB or N-MORB, with relatively low abundances of these elements, and enriched E-MORB. The enrichment of water correlates well with that of these elements. In N-MORB, the water content of the source mantle is inferred to be 0.08–0.18 wt%, while in E-MORB it is 0.2–0.95 wt%.

Another common classification, based on analyses of MORBs and ocean island basalts (OIBs) from hotspots, identifies five components. Focal zone (FOZO) basalt is considered to be closest to the original composition of the mantle. Two enriched end-members (EM-1 and EM-2) are thought to arise from recycling of ocean sediments and OIBs. HIMU stands for "high-μ", where μ is a ratio of uranium and lead isotopes (). The fifth component is depleted MORB (DMM). Because the behavior of water is very similar to that of the element cesium

Caesium (IUPAC spelling) (or cesium in American English) is a chemical element with the symbol Cs and atomic number 55. It is a soft, silvery-golden alkali metal with a melting point of , which makes it one of only five elemental metals that ar ...

, ratios of water to cesium are often used to estimate the concentration of water in regions that are sources for the components. Multiple studies put the water content of FOZO at around 0.075 wt%, and much of this water is likely "juvenile" water acquired during the accretion of Earth. DMM has only 60 ppm water. If these sources sample all the regions of the mantle, the total water depends on their proportion; including uncertainties, estimates range from 0.2 to 2.3 oceans.

Diamond inclusions

Mineral samples from the transition zone and lower mantle come from inclusions found in

Mineral samples from the transition zone and lower mantle come from inclusions found in diamond

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, ...

s. Researchers have recently discovered diamond inclusions of ice-VII in the transition zone. Ice-VII is water in a high pressure state. The presence of diamonds that formed in the transition zone and contain ice-VII inclusions suggests that water is present in the transition zone and at the top of the lower mantle. Of the thirteen ice-VII instances found, eight have pressures around 8–12 GPa, tracing the formation of inclusions to 400–550 km. Two inclusions have pressures between 24 and 25 GPa, indicating the formation of inclusions at 610–800 km. The pressures of the ice-VII inclusions provide evidence that water must have been present at the time the diamonds formed in the transition zone in order to have become trapped as inclusions. Researchers also suggest that the range of pressures at which inclusions formed implies inclusions existed as fluids rather than solids.

Another diamond was found with ringwoodite inclusions. Using techniques including infrared spectroscopy

Infrared spectroscopy (IR spectroscopy or vibrational spectroscopy) is the measurement of the interaction of infrared radiation with matter by absorption, emission, or reflection. It is used to study and identify chemical substances or function ...

, Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy () (named after Indian physicist C. V. Raman) is a spectroscopic technique typically used to determine vibrational modes of molecules, although rotational and other low-frequency modes of systems may also be observed. Raman s ...

, and x-ray diffraction

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angle ...

, scientists found that the water content of the ringwoodite was 1.4 wt% and inferred that the bulk water content of the mantle is about 1 wt%.

Geophysical evidence

Seismic

Both sudden decreases in seismic activity and electricity conduction indicate that the transition zone is able to produce hydrated ringwoodite. The USArray seismic experiment is a long-term project usingseismometer

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The outpu ...

s to chart the mantle underlying the United States. Using data from this project, seismometer measurements show corresponding evidence of melt at the bottom of the transition zone. Melt in the transition zone can be visualized through seismic velocity measurements as sharp velocity decreases at the lower mantle caused by the subduction of slabs through the transition zone. The measured decrease in seismic velocities correlates accurately with the predicted presence of 1 weight % melt of H2O.

Ultra low velocity zone

Ultra low velocity zones (ULVZs) are patches on the core-mantle boundary that have extremely low seismic velocities. The zones are mapped to be hundreds of kilometers in diameter and tens of kilometers thick. Their shear wave velocities can be up ...

s (ULVZs) have been discovered right above the core-mantle boundary (CMB). Experiments highlighting the presence of iron peroxide containing hydrogen (FeO2Hx) aligns with expectations of the ULVZs. Researchers believe that iron and water could react to form FeO2Hx in these ULVZs at the CMB. This reaction would be possible with the interaction of the subduction of minerals containing water and the extensive supply of iron in the Earth's outer core. Past research has suggested the presence of partial melting in ULVZs, but the formation of melt in the area surrounding the CMB remains contested.

Subduction

As an oceanic plate descends into the upper mantle, its minerals tend to lose water. How much water is lost and when depends on the pressure, temperature and mineralogy. Water is carried by a variety of minerals that combine various proportions ofmagnesium oxide

Magnesium oxide ( Mg O), or magnesia, is a white hygroscopic solid mineral that occurs naturally as periclase and is a source of magnesium (see also oxide). It has an empirical formula of MgO and consists of a lattice of Mg2+ ions and O2− ions ...

(MgO), silicon dioxide (SiO2), and water. At low pressures (below 5 GPa), these include antigorite

Antigorite is a lamellated, monoclinic mineral in the phylosilicate serpentine subgroup with the ideal chemical formula of (Mg,Fe2+)3Si2O5(OH)4. It is the high-pressure polymorph of serpentine and is commonly found in metamorphosed serpentinit ...

, a form of serpentine, and clinochlore

The chlorites are the group of phyllosilicate minerals common in low-grade metamorphic rocks and in altered igneous rocks. Greenschist, formed by metamorphism of basalt or other low-silica volcanic rock, typically contains significant amounts o ...

(both carrying 13 wt% water); talc

Talc, or talcum, is a clay mineral, composed of hydrated magnesium silicate with the chemical formula Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Talc in powdered form, often combined with corn starch, is used as baby powder. This mineral is used as a thickening agent ...

(4.8 wt%) and some other minerals with a lower capacity. At moderate pressure (5–7 GPa) the minerals include phlogopite

Phlogopite is a yellow, greenish, or reddish-brown member of the mica family of phyllosilicates. It is also known as magnesium mica.

Phlogopite is the magnesium endmember of the biotite solid solution series, with the chemical formula KMg3AlSi3O ...

(4.8 wt%), the 10Å phase (a high pressure product of talc and water, 10–13 wt%) and lawsonite

Lawsonite is a hydrous calcium aluminium sorosilicate mineral with formula CaAl2Si2O7(OH)2·H2O. Lawsonite crystallizes in the orthorhombic system in prismatic, often tabular crystals. Crystal twinning is common. It forms transparent to translucen ...

(11.5 wt%). At pressures above 7 GPa, there is topaz-OH (Al2SiO4(OH)2, 10 wt%), phase Egg (AlSiO3(OH), 11–18 wt%) and a collection of dense hydrous magnesium silicate (DHMS) or "alphabet" phases such as phase A (12 wt%), D (10 wt%) and E (11 wt%).

The fate of the water depends on whether these phases can maintain an unbroken series as the slab descends. At a depth of about 180 km, where the pressure is about 6 gigapascals (GPa) and the temperature around 600 °C, there is a possible "choke point" where the stability regions just meet. Hotter slabs will lose all their water while cooler slabs pass the water on to the DHMS phases. In cooler slabs, some of the released water may also be stable as Ice VII.

An imbalance in deep water recycling has been proposed as one mechanism that can affect global sea levels.

See also

* Hydrous components in nominally anhydrous minerals * Hydrous minerals of a subducting slabReferences

Further reading

* ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Refend Geological processes Water