Deep Biosphere on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The deep biosphere is the part of the

Most biologists dismissed the subsurface microbes as contamination, especially after the submersible ''Alvin'' sank in 1968 and the scientists escaped, leaving their lunches behind. When ''Alvin'' was recovered, the lunches showed no sign of microbial decay. This reinforced a view of the deep sea (and by extension the subsurface) as a lifeless desert. The study of the deep biosphere was dormant for decades, except for some Soviet microbiologists who began to refer to themselves as geomicrobiologists.

Interest in subsurface life was renewed when the

Most biologists dismissed the subsurface microbes as contamination, especially after the submersible ''Alvin'' sank in 1968 and the scientists escaped, leaving their lunches behind. When ''Alvin'' was recovered, the lunches showed no sign of microbial decay. This reinforced a view of the deep sea (and by extension the subsurface) as a lifeless desert. The study of the deep biosphere was dormant for decades, except for some Soviet microbiologists who began to refer to themselves as geomicrobiologists.

Interest in subsurface life was renewed when the

The ocean floor is sampled by drilling boreholes and collecting cores. The methods must be adapted to different types of rock, and the cost of drilling limits the number of holes that can be drilled. Microbiologists have made use of scientific drilling programs: the

The ocean floor is sampled by drilling boreholes and collecting cores. The methods must be adapted to different types of rock, and the cost of drilling limits the number of holes that can be drilled. Microbiologists have made use of scientific drilling programs: the

Atmospheric pressure is 101

Atmospheric pressure is 101

Life has been found at depths of 5 km in continents and 10.5 km below the ocean surface. In 1992,

Life has been found at depths of 5 km in continents and 10.5 km below the ocean surface. In 1992,

Ocean crust forms at

Ocean crust forms at

One species of Bacteria, " ''Candidatus'' Desulforudis audaxviator", is the first known to comprise a complete ecosystem by itself. It was found 2.8 kilometers below the surface in a gold mine near

One species of Bacteria, " ''Candidatus'' Desulforudis audaxviator", is the first known to comprise a complete ecosystem by itself. It was found 2.8 kilometers below the surface in a gold mine near

IMDb

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Refend

Census of Deep LifeCenter for Dark Energy Biosphere InvestigationsDeep Biosphere map on 3D globe

(GPlates Portal) Biological systems Geomicrobiology

biosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also ...

that resides below the first few meters of the surface. It extends down at least 5 kilometers below the continental surface and 10.5 kilometers below the sea surface, at temperatures that may reach beyond 120 °C, which is comparable to the maximum temperature where a metabolically active organism has been found. It includes all three domains of life and the genetic diversity rivals that on the surface.

The first indications of deep life came from studies of oil fields in the 1920s, but it was not certain that the organisms were indigenous until methods were developed in the 1980s to prevent contamination from the surface. Samples are now collected in deep mines and scientific drilling

Scientific drilling into the Earth is a way for scientists to probe the Earth's sediments, crust, and upper mantle. In addition to rock samples, drilling technology can unearth samples of connate fluids and of the subsurface biosphere, mostly micr ...

programs in the ocean and on land. Deep observatories have been established for more extended studies.

Near the surface, living organisms consume organic matter and breathe oxygen. Lower down, these are not available, so they make use of "edibles" (electron donors

In chemistry, an electron donor is a chemical entity that donates electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process.

Typical reducing agents undergo permanent chemi ...

) such as hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

(released from rocks by various chemical processes), methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane ...

(CH4), reduced sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

compounds and ammonium

The ammonium cation is a positively-charged polyatomic ion with the chemical formula or . It is formed by the protonation of ammonia (). Ammonium is also a general name for positively charged or protonated substituted amines and quaterna ...

(NH4). They "breathe" electron acceptors

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ). In other words, an oxid ...

such as nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insolu ...

s and nitrite

The nitrite ion has the chemical formula . Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name nitrite also ...

s, manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of ...

and iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of wh ...

s, oxidized sulfur compounds and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

(CO2). There is very little energy at greater depths, so metabolisms are up to a million times slower than at the surface. Cells may live for thousands of years before dividing and there is no known limit to their age.

The subsurface accounts for about 90% of the biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bio ...

in two domains of life, Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeba ...

and Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, and 15% of the total for the biosphere. Eukarya are also found, including some multicellular life fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

, and animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage in ...

(nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant- parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a bro ...

s, flatworm

The flatworms, flat worms, Platyhelminthes, or platyhelminths (from the Greek πλατύ, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") are a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegmen ...

s, rotifer

The rotifers (, from the Latin , "wheel", and , "bearing"), commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John H ...

s, annelid

The annelids (Annelida , from Latin ', "little ring"), also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecol ...

s, and arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s). Viruses are also present and infect the microbes.

Definition

The deep biosphere is an ecosystem of organisms and their living space in the deep subsurface. For the seafloor, an operational definition of ''deep subsurface'' is the region that is not bioturbated by animals; this is generally about a meter or more below the surface. On continents, it is below a few meters, not including soils. The organisms in this zone are sometimes referred to as ''intraterrestrials''.History

At theUniversity of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

in the 1920s, geologist Edson Bastin enlisted the help of microbiologist Frank Greer in an effort to explain why water extracted from oil fields contained hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The under ...

and bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial biochemi ...

s. These chemicals are normally created by bacteria, but the water came from a depth where the heat and pressure were considered too great to support life. They were able to culture anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacteria

Sulfate-reducing microorganisms (SRM) or sulfate-reducing prokaryotes (SRP) are a group composed of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and sulfate-reducing archaea (SRA), both of which can perform anaerobic respiration utilizing sulfate () as termina ...

from the water, demonstrating that the chemicals had a bacterial origin.

Also in the 1920s, Charles Lipman

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

, a microbiologist at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant un ...

, noticed that bacteria that had been sealed in bottles for 40 years could be reanimated – a phenomenon now known as anhydrobiosis

Cryptobiosis or anabiosis is a metabolic state of life entered by an organism in response to adverse environmental conditions such as desiccation, freezing, and oxygen deficiency. In the cryptobiotic state, all measurable metabolic processes sto ...

. He wondered whether the same was true of bacteria in coal seams. He sterilized samples of coal, wetted them, crushed them and then succeeded in culturing bacteria from the coal dust. One sterilization procedure, baking the coal at 160 degrees Celsius for up to 50 hours, actually encouraged their growth. He published the results in 1931.

The first studies of subsurface life were conducted by Claude E. Zobell, the "father of marine microbiology", in the late 1930s to the 1950s. Although the coring depth was limited, microbes were found wherever the sediments were sampled.

With increasing depth, aerobes gave way to anaerobes.

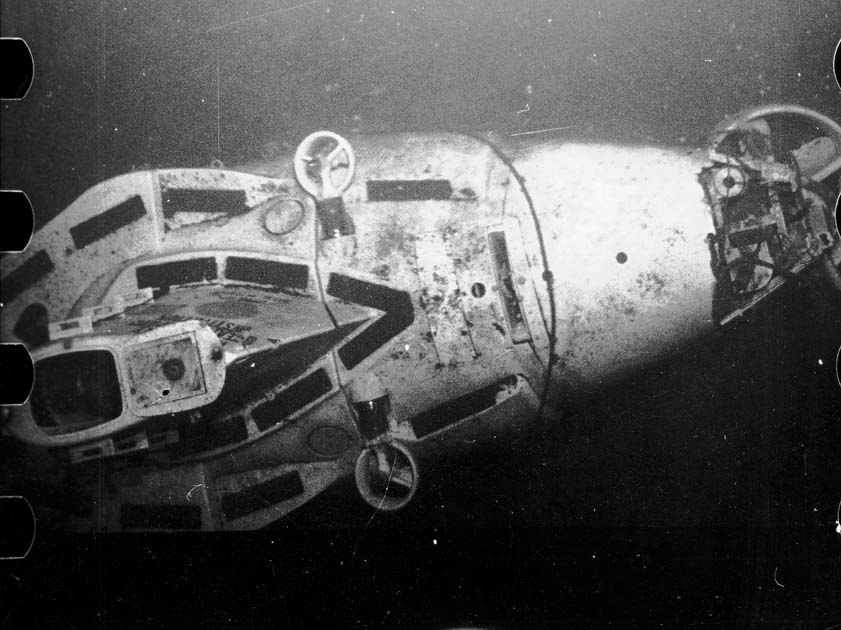

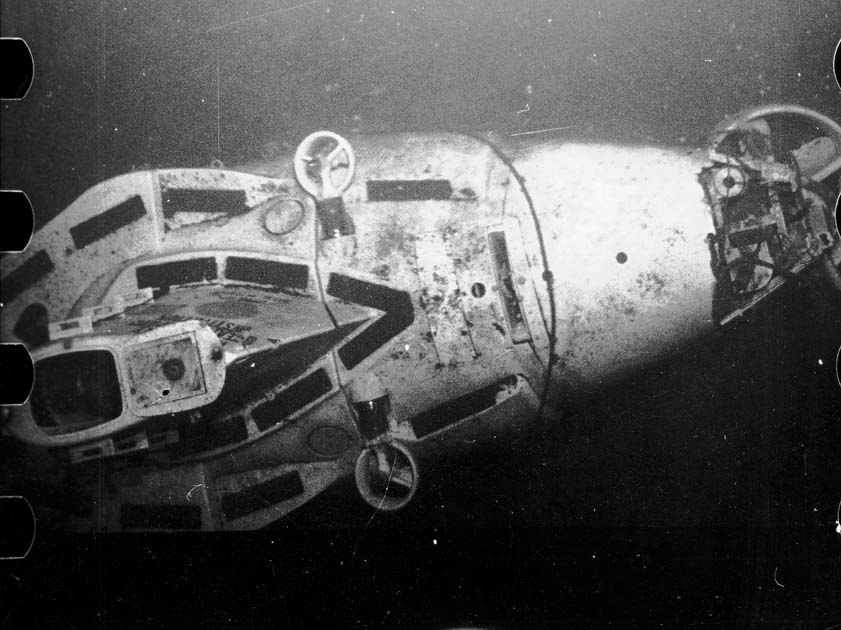

Most biologists dismissed the subsurface microbes as contamination, especially after the submersible ''Alvin'' sank in 1968 and the scientists escaped, leaving their lunches behind. When ''Alvin'' was recovered, the lunches showed no sign of microbial decay. This reinforced a view of the deep sea (and by extension the subsurface) as a lifeless desert. The study of the deep biosphere was dormant for decades, except for some Soviet microbiologists who began to refer to themselves as geomicrobiologists.

Interest in subsurface life was renewed when the

Most biologists dismissed the subsurface microbes as contamination, especially after the submersible ''Alvin'' sank in 1968 and the scientists escaped, leaving their lunches behind. When ''Alvin'' was recovered, the lunches showed no sign of microbial decay. This reinforced a view of the deep sea (and by extension the subsurface) as a lifeless desert. The study of the deep biosphere was dormant for decades, except for some Soviet microbiologists who began to refer to themselves as geomicrobiologists.

Interest in subsurface life was renewed when the United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United States ...

was looking for a safe way of burying nuclear waste, and Frank J. Wobber realized that microbes below the surface could either help by degrading the buried waste or hinder by breaching the sealed containers. He formed the Subsurface Science Program to study deep life. To address the problem of contamination, special equipment was designed to minimize contact between a core sample and the drilling fluid

In geotechnical engineering, drilling fluid, also called drilling mud, is used to aid the drilling of boreholes into the earth. Often used while drilling oil and natural gas wells and on exploration drilling rigs, drilling fluids are als ...

that lubricates the drill bit

Drill bits are cutting tools used in a drill to remove material to create holes, almost always of circular cross-section. Drill bits come in many sizes and shapes and can create different kinds of holes in many different materials. In order ...

. In addition, tracers were added to the fluid to indicate whether it penetrated the core. In 1987, several borehole

A borehole is a narrow shaft bored in the ground, either vertically or horizontally. A borehole may be constructed for many different purposes, including the extraction of water ( drilled water well and tube well), other liquids (such as petrol ...

s were drilled near the Savannah River Site

The Savannah River Site (SRS) is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) reservation in the United States in the state of South Carolina, located on land in Aiken, Allendale, and Barnwell counties adjacent to the Savannah River, southeast of August ...

, and microorganisms were found to be plentiful and diverse at least 500 metres below the surface.

From 1983 until now, microbiologists analyze cell abundances in drill cores from the Ocean Drilling Program

The Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) was a multinational effort to explore and study the composition and structure of the Earth's oceanic basins. ODP, which began in 1985, was the successor to the Deep Sea Drilling Project initiated in 1968 by th ...

(now the International Ocean Discovery Program

The International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) is an international marine research collaboration dedicated to advancing scientific understanding of the Earth through drilling, coring, and monitoring the subseafloor. The research enabled by IODP ...

). A group led by John Parkes of the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

reported concentrations of 104 to 108 cells per gram of sediment down to depths of 500 metres (agricultural soils contain about 109 cells per gram). This was initially met with skepticism and it took them four years to publish their results. In 1998, William Whitman and colleagues published a summary of twelve years of data in the ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America'' (often abbreviated ''PNAS'' or ''PNAS USA'') is a peer-reviewed multidisciplinary scientific journal. It is the official journal of the National Academy of S ...

''. They estimated that up to 95% of all prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

s (archaea and bacteria) live in the deep subsurface, with 55% in the marine subsurface and 39% in the terrestrial subsurface. In 2002, Ocean Drilling Program Leg 201 was the first to be motivated by a search for deep life. Most of the previous exploration was on continental margins, so the goal was to drill in the open ocean for comparison. In 2016, International Ocean Discovery Program Leg 370 drilled into the marine sediment of the Nankai Accretionary Prism

An accretionary wedge or accretionary prism forms from sediments accreted onto the non-subducting tectonic plate at a convergent plate boundary. Most of the material in the accretionary wedge consists of marine sediments scraped off from the do ...

and observed 102 vegetative cells at 118 °C.

Understanding of microbial life at depth was extended beyond the realm of oceanography to earth sciences (and even astrobiology) in 1992 when Thomas Gold

Thomas Gold (May 22, 1920 – June 22, 2004) was an Austrian-born American astrophysicist, a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and a Fellow of the Royal Society (London). Gold was ...

published a paper in '' The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences'' that was titled "The Deep, Hot Biosphere", followed seven years later by his book, ''The Deep Hot Biosphere''. A 1993 article by journalist William Broad

William J. Broad (born March 7, 1951) is an American science journalist, author and a Senior Writer at ''The New York Times''.

Education

Broad earned a master's degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1977.The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' and titled "Strange New Microbes Hint at a Vast Subterranean World," carried Gold's thesis to public attention. The article began, "New forms of microbial life are being discovered in such abundance deep inside the Earth that some scientists are beginning to suspect that the planet has a hidden biosphere extending miles down whose total mass may rival or exceed that of all surface life. If a deep biosphere does exist, scientists say, its discovery will rewrite textbooks while shedding new light on the mystery of life's origins. Even skeptics say the thesis is intriguing enough to warrant new studies of the subterranean realm."

The 1993 article also features how Gold's thesis expands possibilities for astrobiology

Astrobiology, and the related field of exobiology, is an interdisciplinary scientific field that studies the origins, early evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. Astrobiology is the multidisciplinary field that invest ...

research: "Dr. Thomas Gold, an astrophysicist at Cornell University known for bold theorizing, has speculated that subterranean life may dot the cosmos, secluded beneath the surfaces of planets and moons and energized by geological processes, with no need for the warming radiation of nearby stars. He wrote in ''The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences'' last year that the solar system might harbor at least 10 deep biospheres. 'Such life may be widely disseminated in the universe,' he said, 'since planetary type bodies with similar subsurface conditions may be common as solitary objects in space, as well as in other solar-type systems.'"

Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

wrote the foreword to Gold's 1999 book, where he concluded, "Gold's theories are always original, always important, usually controversial — and usually right. It is my belief, based on fifty years of observation of Gold as a friend and colleague, that the deep hot biosphere is all of the above: original, important, controversial — and right."

Dyson also delivered a eulogy at Gold's memorial service in 2004, a segment of which pertaining to the deep hot biosphere theory is posted on youtube.

Following Gold's death, scientific discoveries amplified and also shifted understanding of the deep biosphere. A term Gold coined in his 1999 book, however, carries forward and is a reminder of the worldview shift he advocated. The term is " surface chauvinism". Gold wrote, "In retrospect, it is not hard to understand why the scientific community has typically sought only ''surface'' life in the heavens. Scientists have been hindered by a sort of 'surface chauvinism.'".

Scientific methods

The present understanding of subsurface biology was made possible by numerous advances in technology for sample collection, field analysis, molecular science, cultivation, imaging and computation.Sample collection

The ocean floor is sampled by drilling boreholes and collecting cores. The methods must be adapted to different types of rock, and the cost of drilling limits the number of holes that can be drilled. Microbiologists have made use of scientific drilling programs: the

The ocean floor is sampled by drilling boreholes and collecting cores. The methods must be adapted to different types of rock, and the cost of drilling limits the number of holes that can be drilled. Microbiologists have made use of scientific drilling programs: the Ocean Drilling Program

The Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) was a multinational effort to explore and study the composition and structure of the Earth's oceanic basins. ODP, which began in 1985, was the successor to the Deep Sea Drilling Project initiated in 1968 by th ...

(ODP), which used the JOIDES ''Resolution'' drilling platform, and the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program

The Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) was an international marine research program. The program used heavy drilling equipment mounted aboard ships to monitor and sample sub-seafloor environments. With this research, the IODP documented e ...

(IODP), which used the Japanese ship ''Chikyū

is a Japanese scientific drilling ship built for the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP). The vessel is designed to ultimately drill beneath the seabed, where the Earth's crust is much thinner, and into the Earth's mantle, deeper than any ...

''.

Deep underground mines, for example South African gold mines and the Pyhäsalmi copper and zinc mine in Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

, have provided opportunities to sample the deep biosphere. The deep subsurface has also been sampled at chosen or proposed nuclear waste repository sites (e.g. Yucca Mountain

Yucca Mountain is a mountain in Nevada, near its border with California, approximately northwest of Las Vegas. Located in the Great Basin, Yucca Mountain is east of the Amargosa Desert, south of the Nevada Test and Training Range and in the ...

and the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, or WIPP, is the world's third deep geological repository (after Germany's Repository for radioactive waste Morsleben and the Schacht Asse II salt mine) licensed to store transuranic radioactive waste for 10,00 ...

in the United States, Äspö and surrounding areas in Sweden, Onkalo

"Onkalo" is a maxi single released by the J-pop singer Eiko Shimamiya (ETB-0161). Released 21 June 2012, it is her first single after her retirement from I've Sound in April 2011. The single features two new songs; Onkalo and Unison.

Track list ...

and surrounding areas in Finland, Mont Terri in Switzerland). Scientific drilling of continental deep subsurface has been promoted by the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program

The International Continental Scientific Drilling Program is a multinational program to further and fund geosciences in the field of Continental Scientific Drilling. Scientific drilling is a critical tool in understanding of Earth processes and s ...

(ICDP).

To allow continuous underground sampling, various kinds of observatories have been developed. On the ocean floor, the Circulation Obviation Retrofit Kit (CORK) seals a borehole to cut off the influx of seawater. An advanced version of CORK is able to seal off multiple sections of a drill hole using ''packers'', rubber tubes that inflate to seal the space between the drill string

A drill string on a drilling rig is a column, or string, of drill pipe that transmits drilling fluid (via the mud pumps) and torque (via the kelly drive or top drive) to the drill bit. The term is loosely applied to the assembled collecti ...

and the wall of the borehole. In sediments, the Simple Cabled Instrument for Measuring Parameters In-Situ (SCIMPI) is designed to remain and take measurements after a borehole has collapsed.

Packers are also used in the continental subsurface, along with devices such as the flow-through reactor (FTISR). Various methods are used to extract fluids from these sites, including passive gas samplers, U-tube systems and osmotic

Osmosis (, ) is the spontaneous net movement or diffusion of solvent molecules through a selectively-permeable membrane from a region of high water potential (region of lower solute concentration) to a region of low water potential (region ...

gas samplers. In narrow (less than 50 mm) holes, polyamide

A polyamide is a polymer with repeating units linked by amide bonds.

Polyamides occur both naturally and artificially. Examples of naturally occurring polyamides are proteins, such as wool and silk. Artificially made polyamides can be made th ...

tubes with a back-pressure valve can be lowered to sample an entire column of fluid.

Field analysis and manipulation

Some methods analyze microbes rather than extract them. In biogeophysics, the effects of microbes on properties of geological materials are remotely probed using electrical signals. Microbes can be tagged using a stable isotope such ascarbon-13

Carbon-13 (13C) is a natural, stable isotope of carbon with a nucleus containing six protons and seven neutrons. As one of the environmental isotopes, it makes up about 1.1% of all natural carbon on Earth.

Detection by mass spectrometry

A mas ...

and then re-injected in the ground to see where they go. A "push-pull" method involves injection of a fluid into an aquifer and extraction of a mixture of injected fluid with the ground water; the latter can then be analyzed to determine what chemical reactions occurred.

Molecular methods and cultivation

Methods from modern molecular biology allow the extraction of nucleic acids, lipids and proteins from cells,DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. T ...

, and the physical and chemical analysis of molecules using mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is u ...

and flow cytometry

Flow cytometry (FC) is a technique used to detect and measure physical and chemical characteristics of a population of cells or particles.

In this process, a sample containing cells or particles is suspended in a fluid and injected into the flow ...

. A lot can be learned about the microbial communities using these methods even when the individuals cannot be cultivated. For example, at the Richmond Mine in California, scientists used shotgun sequencing

In genetics, shotgun sequencing is a method used for sequencing random DNA strands. It is named by analogy with the rapidly expanding, quasi-random shot grouping of a shotgun.

The chain-termination method of DNA sequencing ("Sanger sequencing ...

to identify four new species of bacteria, three new species of archaea (known as the Archaeal Richmond Mine acidophilic nanoorganisms), and 572 proteins unique to the bacteria.

Geochemical methods

Deep microorganisms change the chemistry of their surroundings. They consume nutrients and product wastes frommetabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

. Therefore we can estimate the activities of the deep microorganisms by measuring the chemical compositions in the subseafloor samples. Complementary techniques include measuring the isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass num ...

compositions of the chemicals or the related mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s.

Conditions for life

For life to have metabolic activity, it must be able to take advantage of a thermodynamic disequilibrium in the environment. This can occur when rocks from the mantle that are rich in the mineralolivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers qui ...

are exposed to seawater and react with it to form serpentine minerals and magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

. Non-equilibrium conditions are also associated with hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspo ...

s, volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

, and geothermal activity. Other processes that might provide habitats for life include roll front development in ore bodies, subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

, methane clathrate

Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) or (8CH4·46H2O), also called methane hydrate, hydromethane, methane ice, fire ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate, is a solid clathrate compound (more specifically, a clathrate hydrate) in which a large amou ...

formation and decomposition, permafrost

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface ...

thawing, infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of Light, visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from ...

radiation and seismic activity. Humans also create new habitats for life, particularly through remediation of contaminants in the subsurface.

Energy sources

Life requires enough energy to constructadenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms ...

(ATP). Where there is sunlight, the main processes for capturing energy are photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

(which harnesses the energy in sunlight by converting carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

into organic molecules

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

) and respiration

Respiration may refer to:

Biology

* Cellular respiration, the process in which nutrients are converted into useful energy in a cell

** Anaerobic respiration, cellular respiration without oxygen

** Maintenance respiration, the amount of cellul ...

(which consumes those molecules and releases carbon dioxide). Below the surface, the main source of energy is from chemical redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or ...

(reduction-oxidation) reactions. This requires electron donor

In chemistry, an electron donor is a chemical entity that donates electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process.

Typical reducing agents undergo permanent chemi ...

s (compounds that can be oxidized) and electron acceptor

An electron acceptor is a chemical entity that accepts electrons transferred to it from another compound. It is an oxidizing agent that, by virtue of its accepting electrons, is itself reduced in the process. Electron acceptors are sometimes mista ...

s (compounds that can be reduced). An example of such a reaction is methane oxidation:

:CH4 + O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O

Here CH4 is the donor and O2 is the acceptor. Donors can be considered "edibles" and acceptors "breathables".

The amount of energy that is released in a metabolic reaction depends on the redox potential of the chemicals involved. Electron donors have negative potentials. From highest to lowest redox potential, some common donors available in the subsurface are organic matter, hydrogen, methane, reduced sulfur compounds, reduced iron compounds and ammonium. From most negative to least, some acceptors are oxygen, nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insolu ...

s and nitrite

The nitrite ion has the chemical formula . Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name nitrite also ...

s, manganese and iron oxides, oxidized sulfur compounds, and carbon dioxide.

Of electron donors, organic matter has the most negative redox potential. It can consist of deposits from regions where sunlight is available or produced by local organisms. Fresh material is more easily utilized than aged. Terrestrial organic matter (mainly from plants) is typically harder to process than marine (phytoplankton). Some organisms break down organic compounds using fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

and hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysi ...

, making it possible for others to convert it back to carbon dioxide. Hydrogen is a good energy source, but competition tends to make it scarce. It is particularly rich in hydrothermal fluids where it is produced by serpentinization. Multiple species can combine fermentation with methanogenesis

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane coupled to energy conservation by microbes known as methanogens. Organisms capable of producing methane for energy conservation have been identified only from the domain Archaea, a group ...

and iron oxidation with hydrogen consumption. Methane is mostly found in marine sediments, in gaseous form (dissolved or free) or in methane hydrates

Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) or (8CH4·46H2O), also called methane hydrate, hydromethane, methane ice, fire ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate, is a solid clathrate compound (more specifically, a clathrate hydrate) in which a large amou ...

. About 20% comes from abiotic sources (breakdown of organic matter or serpentinization) and 80% from biotic sources (which reduce organic compounds such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and acetate

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called ...

). Over 90% of methane is oxidized by microbes before it reaches the surface; this activity is "one of the most important controls on greenhouse gas emissions and climate on Earth." Reduced sulfur compounds such as elemental sulfur, hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The under ...

(H2S) and pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Iron, FeSulfur, S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic Luster (mineralogy), lust ...

(FeS2) are found in hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspo ...

s in basaltic crust, where they precipitate out when metal-rich fluids contact seawater. Reduced iron compounds in sediments are mainly deposited or produced by anaerobic reduction of iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of wh ...

s.

The electron acceptor with the highest redox potential is oxygen. Produced by photosynthesis, it is transported to the ocean floor. There, it is quickly taken up if there is a lot of organic material, and may only be present in the top few centimeters. In organic-poor sediments it can be found at greater depths, even to the oceanic crust. Nitrate can be produced by degradation of organic matter or nitrogen fixation. Oxygen and nitrate are derived from photosynthesis, so underground communities that utilize them are not truly independent of the surface.

Nutrients

All life requires carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and some trace elements such as nickel,molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element with the symbol Mo and atomic number 42 which is located in period 5 and group 6. The name is from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'', which is based on Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ...

and vanadium

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( pass ...

. Over 99.9% of Earth's carbon is stored in the crust and its overlying sediments, but the availability of this carbon can depend on the oxidation state of the environment. Organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus are primarily found in terrestrial sediments, which accumulate mainly in continental margins. Organic carbon is mainly produced at the surface of the oceans with photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

or washed into oceans with terrestrial sediments. Only a small fraction is produced in the deep seas with chemosynthesis

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

. When organic carbon sinks from the surface of the ocean to the seafloor, most of the organic carbon is consumed by organisms in seawater. Only a small fraction of this sinking organic carbon can reach the seafloor and be available to the deep biosphere. Deeper in the marine sediment

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mai ...

s, the organic content drops further. Phosphorus is taken up by iron oxyhydroxides when basalts and sulfide rocks are weathered, limiting its availability. The availability of nutrients are limiting the deep biosphere, determining where and what type of deep organisms can thrive.

Pressure

Atmospheric pressure is 101

Atmospheric pressure is 101 kilopascals

The pascal (symbol: Pa) is the unit of pressure in the International System of Units, International System of Units (SI), and is also used to quantify internal pressure, stress (physics), stress, Young's modulus, and ultimate tensile strength. T ...

(kPa). In the ocean, the pressure increases at a rate of 10.5 kPa per m of depth, so at a typical depth of the sea floor (3800 m) the pressure is 38 megapascals (MPa). At these depths, the boiling point of water is over 400 °C. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the pressure is 110 MPa. In the lithosphere, the pressure increases by 22.6 kPa/m. The deep biosphere withstands pressures much higher than the pressure at the surface of the Earth.

An increased pressure compresses lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids in ...

s, making membranes less fluid. In most chemical reactions, the products occupy more volume than the reactants, so the reactions are inhibited by pressure. Nevertheless, some studies claim that cells from the surface are still active at a pressure of 1 gigapascal (GPa), about 10,000 times the standard atmospheric pressure. There are also piezophile A piezophile (from Greek "piezo-" for pressure and "-phile" for loving) is an organism with optimal growth under high hydrostatic pressure i.e. an organism that has its maximum rate of growth at a hydrostatic pressure equal to or above 10 MPa (= 99 ...

s for which optimal growth occurs at pressures over 100 MPa, and some do not grow in pressures less than 50 MPa.

As of 2019, most sampling of organisms from the deep ocean and subsurface undergo decompression when they are removed to the surface. This can harm the cells in a variety of ways, and experiments at surface pressures produce an inaccurate picture of microbial activity in the deep biosphere. A Pressurized Underwater Sampler Handler (PUSH50) has been developed to maintain pressure during sampling and afterwards in the laboratory.

Temperature

High temperatures stress organisms, increasing the rates of processes that damage important molecules such as DNA andamino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s. It also increases the energy requirements for repairing these molecules. However, cells can respond by changing the structure of these molecules to stabilize them.

Microbes can survive at temperatures above 100 °C if the pressure is high enough to keep the water from boiling. The highest temperature at which an organism has been cultured in a laboratory is 122 °C, under pressures of 20 MPa and 40 MPa. Theoretical estimates for the highest temperature that can sustain life are around 150 °C. The 120 °C isotherm can be less than 10 m deep at mid-ocean ridges and seamounts, but in other environments such as deep-sea trenches it can be kilometers deep. About 39% by volume of ocean sediment

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mai ...

s is at temperatures between 40 °C and 120 °C. Thermochronology data of Precambrian cratons suggest that habitable temperature conditions of the subsurface in these setting range back to about a billion years maximum.

The record-setting thermophile, '' Methanopyrus kandlerii'', was isolated from a hydrothermal vent. Hydrothermal vents provide abundant energy and nutrients. Several groups of Archaea and Bacteria thrive in the shallow seafloor at temperatures between 80 °C and 105 °C. As the environment becomes more energy-limited, such as being deeper, bacteria can survive but their number decreases. Although microorganisms have been detected at temperatures up to 118 °C in cored sediments, attempts to isolate the organisms have failed. There can also be depth intervals with less cells than the deeper part of the location. Reasons for such 'low- or no-cell intervals' are still unknown but may be related to the underground flow of hot fluid. In deep oil reservoirs, no microbial activity has been seen hotter than 80 °C.

Living with energy limitation

In most of the subsurface, organisms live in conditions of extreme energy and nutrient limitation. This is far from the conditions in which cells are cultured in labs. A lab culture goes through a series of predictable phases. After a short lag phase, there is a period of exponential growth in which the population can double in as little as 20 minutes. A death phase follows in which almost all the cells die off. The remainder enter an extended stationary phase in which they can last for years without further input of substrate. However, each live cell has 100 to 1000 dead cells to feed on, so they still have abundant nutrients compared to the subsurface. In the subsurface, cells catabolize (break down molecules for energy or building materials) 10,000 to one million times slower than at the surface. Biomass may take centuries or millennia toturn over

''Turn Over'' is the first live album of the Japanese rock group Show-Ya. It is a collection of live songs recorded during concerts from the "Date Line Tour" and "Immigration Tour" in 1987, and from the "Tour of the Immigrant" in 1988. The album ...

. There is no known limit to the age that cells could reach. The viruses that are present could kill cells and there may be grazing by eukaryotes, but there is no evidence of that.

It is difficult to establish clear limits on the energy needed to keep cells alive but not growing. They need energy to perform certain basic functions like the maintenance of osmotic pressure and maintenance of macromolecules such as enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s and RNA (e.g., proofreading

Proofreading is the reading of a galley proof or an electronic copy of a publication to find and correct reproduction errors of text or art. Proofreading is the final step in the editorial cycle before publication.

Professional

Traditional ...

and synthesis). However, laboratory estimates of the energy needed are several orders of magnitude greater than the energy supply that appears to sustain life underground.

It was thought, at first, that most underground cells are dormant. However, some extra energy is required to come out of dormancy. This is not a good strategy in an environment where the energy sources are stable over millions of years but decreasing slowly. The available evidence suggests that most cells in the subsurface are active and viable.

A low-energy environment favors cells with minimal self-regulation, because there are no changes in the environment that they need to respond to. There could be low-energy specialists. However, there is unlikely to be strong evolutionary pressure

Any cause that reduces or increases reproductive success in a portion of a population potentially exerts evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of ...

for such organisms to evolve because of the low turnover and because the environment is a dead end.

Diversity

Thebiomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bio ...

in the deep subsurface is about 15% of the total for the biosphere. Life from all three domains (Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeba ...

, Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, and Eukarya) have been found in the deep subsurface; indeed, the deep subsurface accounts for about 90% of all the biomass in Archaea and Bacteria. The genetic diversity is at least as great as that on the surface.

In the ocean, plankton species are distributed globally and are constantly being deposited almost everywhere. Quite different communities are found even in the top of ocean floor, and species diversity decreases with depth. However, there are still some taxa that are widespread in the subsurface. In marine sediment

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mai ...

s, the main bacterial phyla

Bacterial phyla constitute the major lineages of the domain ''Bacteria''. While the exact definition of a bacterial phylum is debated, a popular definition is that a bacterial phylum is a monophyletic lineage of bacteria whose 16S rRNA genes s ...

are "''Candidatus'' Atribacteria" (formerly OP9 and JS1), Pseudomonadota

Pseudomonadota (synonym Proteobacteria) is a major phylum of Gram-negative bacteria. The renaming of phyla in 2021 remains controversial among microbiologists, many of whom continue to use the earlier names of long standing in the literature. Th ...

, Chloroflexota

The Chloroflexota are a phylum of bacteria containing isolates with a diversity of phenotypes, including members that are aerobic thermophiles, which use oxygen and grow well in high temperatures; anoxygenic phototrophs, which use light for p ...

, and Planctomycetota

The Planctomycetota are a phylum of widely distributed bacteria, occurring in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats. They play a considerable role in global carbon and nitrogen cycles, with many species of this phylum capable of anaerobic ammoniu ...

. Members of Archaea were first identified using metagenomic analysis; some of them have since been cultured and they have acquired new names. The Deep Sea Archaeal Group (DSAG) became the Marine Benthic Group B (MBG-B) and is now a proposed phylum " Lokiarchaeota". Along with the former Ancient Archaeal Group (AAG) and Marine Hydrothermal Vent Group (MHVG), "Lokiarchaeota" is part of a candidate superphylum, Asgard

In Nordic mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr'' ; "enclosure of the Æsir") is a location associated with the gods. It appears in a multitude of Old Norse sagas and mythological texts. It is described as the fortified home of the Æsir ...

. Other phyla are "Bathyarchaeota

TACK is a group of archaea acronym for Thaumarchaeota (now Nitrososphaerota), Aigarchaeota, Crenarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), and Korarchaeota, the first groups discovered. They are found in different environments ranging from acidophilic th ...

" (formerly the Miscellaneous Chrenarchaeotal Group), '' Nitrososphaerota'' (formerly Thaumarchaeota or Marine Group I), and Euryarchaeota

Euryarchaeota (from Ancient Greek ''εὐρύς'' eurús, "broad, wide") is a phylum of archaea. Euryarchaeota are highly diverse and include methanogens, which produce methane and are often found in intestines, halobacteria, which survive extr ...

(including "Hadesarchaea

Hadesarchaea, formerly called the South-African Gold Mine Miscellaneous Euryarchaeal Group, are a class of thermophile microorganisms that have been found in deep mines, hot springs, marine sediments and other subterranean environments.

Nomencla ...

", Archaeoglobales

Archaeoglobaceae are a family of the Archaeoglobales. All known genera within the Archaeoglobaceae are hyperthermophilic and can be found near undersea hydrothermal vents. Archaeoglobaceae are the only family in the order ''Archaeoglobales'', w ...

and Thermococcales). A related clade, anaerobic methanotrophic archaea (ANME), is also represented. Other bacterial phyla include Thermotogota

The Thermotogota are a phylum of the domain Bacteria. The phylum Thermotogota is composed of Gram-negative staining, anaerobic, and mostly thermophilic and hyperthermophilic bacteria.Gupta, RS (2014) The Phylum Thermotogae. The Prokaryotes 989-10 ...

.

In the continental subsurface, the main bacterial groups are Pseudomonadota and Bacillota

The Bacillota (synonym Firmicutes) are a phylum of bacteria, most of which have gram-positive cell wall structure. The renaming of phyla such as Firmicutes in 2021 remains controversial among microbiologists, many of whom continue to use the earl ...

while the Archaea are mainly Methanomicrobia

In the taxonomy of microorganisms, the Methanomicrobia are a class of the Euryarchaeota.

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) and National Center for Biotech ...

and Nitrososphaerota. Other phyla include "Bathyarchaeota" and "Aigarchaeota

The "Aigarchaeota" are a proposed archaeal phylum of which the main representative is '' Caldiarchaeum subterraneum''.. It is not yet clear if this represents a new phylum or a and order of the Nitrososphaerota, since the genome of ''Caldiarchae ...

", while bacterial phyla include Aquificota

The ''Aquificota'' phylum is a diverse collection of bacteria that live in harsh environmental settings. The name ''Aquificota'' was given to this phylum based on an early genus identified within this group, '' Aquifex'' (“water maker”), whic ...

and Nitrospirota

Nitrospirota is a phylum of bacteria. It includes multiple genera, such as '' Nitrospira'', the largest. The first member of this phylum, '' Nitrospira marina'', was discovered in 1985. The second member, '' Nitrospira moscoviensis'', was discove ...

.

The eukarya in the deep biosphere include some multicellular life. In 2009 a species of nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant- parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a bro ...

, '' Halicephalobus mephisto'', was discovered in rock fissures more than a kilometer down a South African gold mine. Nicknamed the "devil worm", it may have been forced down along with pore water by earthquakes. Other multicellular organisms have since been found, including fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

, Platyhelminthes

The flatworms, flat worms, Platyhelminthes, or platyhelminths (from the Greek πλατύ, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") are a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegm ...

(flatworms), Rotifera, Annelida (ringed worms) and Arthropoda

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chitin ...

. However, their range may be limited because sterol

Sterol is an organic compound with formula , whose molecule is derived from that of gonane by replacement of a hydrogen atom in position 3 by a hydroxyl group. It is therefore an alcohol of gonane. More generally, any compounds that contain the go ...

s, needed to construct membranes in eukarya, are not easily made in anaerobic conditions.

Viruses are also present in large numbers and infect a diverse range of microbes in the deep biosphere. They may contribute significantly to cell turnover and transfer of genetic information between cells.

Habitats

Life has been found at depths of 5 km in continents and 10.5 km below the ocean surface. In 1992,

Life has been found at depths of 5 km in continents and 10.5 km below the ocean surface. In 1992, Thomas Gold

Thomas Gold (May 22, 1920 – June 22, 2004) was an Austrian-born American astrophysicist, a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and a Fellow of the Royal Society (London). Gold was ...

calculated that if the estimated pore space of the terrestrial land mass down to 5 km depth was filled with water, and if 1% of this volume were microbial biomass, it would be enough living matter to cover Earth's land surface with a 1.5 m thick layer. The estimated volume of the deep biosphere is 2–2.3 billion cubic kilometers, about twice the volume of the oceans.

Ocean floor

The main types of habitat below the seafloor are sediments andigneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma o ...

. The latter may be partially altered and coexist with its alteration products such as sulfides and carbonates. In rock, chemicals are mainly carried through an aquifer

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing, permeable rock, rock fractures, or unconsolidated materials ( gravel, sand, or silt). Groundwater from aquifers can be extracted using a water well. Aquifers vary greatly in their characte ...

system that cycles all of the ocean's water every 200,000 years. In sediments below the top few centimeters, chemicals mainly spread by the much slower process of diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical ...

.

Sediments

Nearly all of the seafloor is covered by marine sediments. They can vary in thickness from centimeters near ocean ridges to over 10 kilometers in deeptrenches

A trench is a type of excavation or in the ground that is generally deeper than it is wide (as opposed to a wider gully, or ditch), and narrow compared with its length (as opposed to a simple hole or pit).

In geology, trenches result from erosi ...

. In the mid-ocean, coccolith

Coccoliths are individual plates or scales of calcium carbonate formed by coccolithophores (single-celled phytoplankton such as '' Emiliania huxleyi'') and cover the cell surface arranged in the form of a spherical shell, called a ''coccosphere' ...

s and shells settling down from the surface form oozes, while near shore sediment is carried from the continents by rivers. Minerals from hydrothermal vents and wind-blown particles also contribute. As organic matter is deposited and buried, the more easily utilized compounds are depleted by microbial oxidation, leaving the more recalcitrant compounds. Thus, the energy available for life declines. In the top few meters, metabolic rates decline by 2 to 3 orders of magnitude, and throughout the sediment column cell numbers decline with depth.

Sediments form layers with different conditions for life. In the top 5–10 centimeters, animals burrow, reworking the sediment and extending the sediment-water interface. The water carries oxygen, fresh organic matter and dissolved metabolite

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, ...

s, resulting in a heterogenous environment with abundant nutrients. Below the burrowed layer is a layer dominated by sulfate reduction. Below that, the anaerobic reduction of methane is facilitated by sulfate in the sulfate-methane transition zone (SMTZ). Once the sulfates are depleted, methane formation takes over. The depth of the chemical zones depends on the rate that organic matter is deposited. Where it is rapid, oxygen is taken up rapidly as organic matter is consumed; where slow, oxygen can persist much deeper because of the lack of nutrients to oxidize.

Ocean sediment habitats can be divided into subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

zones, abyssal plain

An abyssal plain is an underwater plain on the deep ocean floor, usually found at depths between and . Lying generally between the foot of a continental rise and a mid-ocean ridge, abyssal plains cover more than 50% of the Earth's surface ...

s, and passive margin

A passive margin is the transition between oceanic and continental lithosphere that is not an active plate margin. A passive margin forms by sedimentation above an ancient rift, now marked by transitional lithosphere. Continental rifting cre ...

s. At a subduction zone, where one plate is diving under another, a thick wedge of sediment tends to form. At first the sediment has 50 to 60 percent porosity

Porosity or void fraction is a measure of the void (i.e. "empty") spaces in a material, and is a fraction of the volume of voids over the total volume, between 0 and 1, or as a percentage between 0% and 100%. Strictly speaking, some tests measur ...

; as it is compressed, fluids are expelled to form cold seep

A cold seep (sometimes called a cold vent) is an area of the ocean floor where hydrogen sulfide, methane and other hydrocarbon-rich fluid seepage occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. ''Cold'' does not mean that the temperature of the see ...

s or gas hydrates

Clathrate hydrates, or gas hydrates, clathrates, hydrates, etc., are crystalline water-based solids physically resembling ice, in which small non-polar molecules (typically gases) or polar molecules with large hydrophobic moieties are trapped i ...

.

Abyssal plains are the region between continental margin

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges. The continental margin ...

s and mid-ocean ridges, usually at depths below 4 kilometers. The ocean surface is very poor in nutrients such as nitrate, phosphate and iron, limiting the growth of phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

...

; this results in low sedimentation rates. The sediment tends to be very poor in nutrients, so not all the oxygen is consumed; oxygen has been found all the way down to the underlying rock. In such environments, cells are mostly either strictly aerobic or facultative anaerobic

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

(using oxygen where available but able to switch to other electron acceptors in its absence) and they are heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

ic (not primary producers). They include Pseudomonadota, Chloroflexota, Marine Group II archaea and lithoautotrophs in the Nitrososphaerota phylum. Fungi are diverse, including members of the Ascomycota

Ascomycota is a phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, forms the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi or ascomycetes. It is the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species. The defi ...

and Basidiomycota

Basidiomycota () is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Bas ...

phyla as well as yeasts

Passive margins (continental shelves and slopes) are under relatively shallow water. Upwelling brings nutrient-rich water to the surface, stimulating abundant growth of phytoplankton, which then settles to the bottom (a phenomenon known as the biological pump

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments.Sigman DM & GH ...

). Thus, there is a lot of organic material in the sediments, and all the oxygen is used up in its consumption. They have very stable temperature and pressure profiles. The population of microbes is orders of magnitude greater than in the abyssal plains. It includes strict anaerobes including members of the Chloroflexi phylum, "''Ca.'' Atribacteria", sulfate-reducing bacteria

Sulfate-reducing microorganisms (SRM) or sulfate-reducing prokaryotes (SRP) are a group composed of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and sulfate-reducing archaea (SRA), both of which can perform anaerobic respiration utilizing sulfate () as termina ...

, and fermenters, methanogen

Methanogens are microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct in hypoxic conditions. They are prokaryotic and belong to the domain Archaea. All known methanogens are members of the archaeal phylum Euryarchaeota. Methanogens are c ...

s and methanotrophs in the Archaea. Fungi are less diverse than in abyssal plains, mainly including Ascomycota and yeasts. Viruses in the ''Inoviridae

Filamentous bacteriophage is a family of viruses (''Inoviridae'') that infect bacteria. The phages are named for their filamentous shape, a worm-like chain (long, thin and flexible, reminiscent of a length of cooked spaghetti), about 6 nm ...

'', '' Siphoviridae'', and '' Lipothrixviridae'' families have been identified.

Rocks

Ocean crust forms at

Ocean crust forms at mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a div ...

s and is removed by subduction. The top half kilometer or so is a series of basaltic flows, and only this layer has enough porosity and permeability to allow fluid flow. Less suitable for life are the layers of sheeted dikes and gabbro

Gabbro () is a phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling of magnesium-rich and iron-rich magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ...

s underneath.

Mid-ocean ridges are a hot, rapidly changing environment with a steep vertical temperature gradient, so life can only exist in the top few meters. High-temperature interactions between water and rock reduce sulfates, producing abundant sulfides that serve as energy sources; they also strip the rock of metals that can be sources of energy or toxic. Along with degassing from magma, water interactions also produce a lot of methane and hydrogen. No drilling has yet been accomplished, so information on microbes comes from samples of hydrothermal fluids coming out of vents.

About 5 kilometers off the ridge axis, when the crust is about 1 million years old, ridge flanks begin. Characterized by hydrothermal circulation, they extend to about 80 million years in age. This circulation is driven by latent heat from the cooling of crust, which heats seawater and drives it up through more permeable rock. Energy sources come from alteration of the rock, some of which is mediated by living organisms. In the younger crust, there is a lot of iron and sulfur cycling. Sediment cover slows the cooling and reduces the flow of water. There is little evidence of microbe activity in older (more than 10 million year old) crust.

Near subduction zones, volcanoes can form in island arc

Island arcs are long chains of active volcanoes with intense seismic activity found along convergent tectonic plate boundaries. Most island arcs originate on oceanic crust and have resulted from the descent of the lithosphere into the mantle alon ...

s and back-arc

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic basin, found at some convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found in the western Pacific Ocean. Most of ...

regions. The subducting plate releases volatiles and solutes to these volcanoes, resulting in acidic fluids with higher concentrations of gases and metals than in the mid-ocean ridge. It also releases water that can mix with mantle material to form serpentinite. When hotspot volcanoes occur in the middle of oceanic plates, they create permeable and porous basalts with higher concentrations of gas than at mid-ocean ridges. Hydrothermal fluids are cooler and have a lower sulfide content. Iron-oxidizing bacteria create extensive deposits of iron oxides.

Porewater

Microorganisms live in the cracks, holes and empty space inside sediments and rocks. Such empty space provides water and dissolved nutrients to the microorganisms. Note that as the depth increases, there are less nutrients in the porewater as nutrients are continuously consumed by microorganisms. As the depth increases, the sediment is morecompact

Compact as used in politics may refer broadly to a pact or treaty; in more specific cases it may refer to:

* Interstate compact

* Blood compact, an ancient ritual of the Philippines

* Compact government, a type of colonial rule utilized in Britis ...

and there is less space between mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

grains. As a result, there is less porewater per volume. The environment gets drier and drier when sediments are transitioned into rocks. At this stage, water can also be a limiting factor to the deep biosphere.

Continents

Continents have a complex history and a great variety of rocks, sediments and soils; the climate on the surface, temperature profiles and hydrology also vary. Most of the information on subsurface life comes from a small number of sampling sites that are mainly in North America. With the exception of ice cores, densities of cells decline steeply with depth, decreasing by several orders of magnitude. In the top one or two meters of soils, organisms depend on oxygen and areheterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

s, depending on the breakdown of organic carbon for their nutrition, and their decline in density parallels that of the organic material. Below that, there is no correlation, although both cell density and organic content declines by a further five orders of magnitude

An order of magnitude is an approximation of the logarithm of a value relative to some contextually understood reference value, usually 10, interpreted as the base of the logarithm and the representative of values of magnitude one. Logarithmic dis ...