comb jelly on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

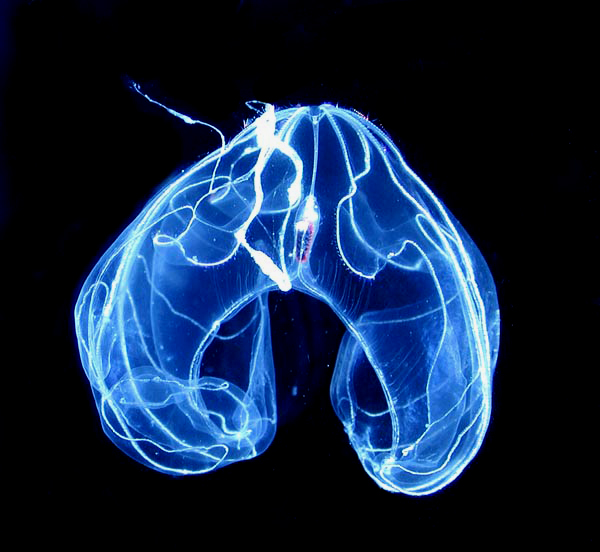

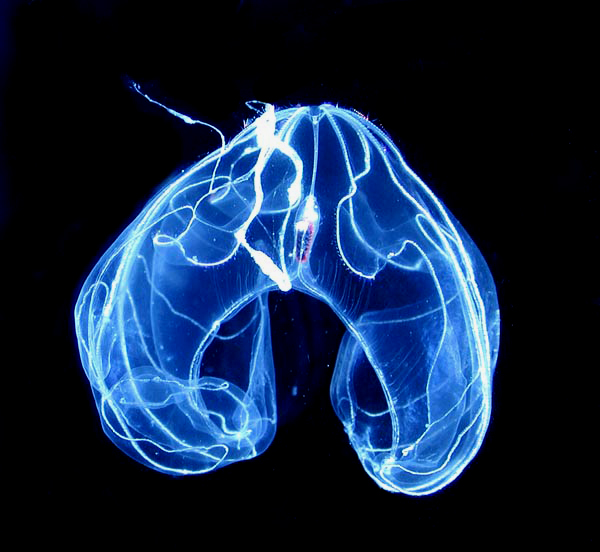

Ctenophora (; ctenophore ; ) comprise a

Like those of

Like those of

Cydippid ctenophores have bodies that are more or less rounded, sometimes nearly spherical and other times more cylindrical or egg-shaped; the common coastal "sea gooseberry", '' Pleurobrachia'', sometimes has an egg-shaped body with the mouth at the narrow end, although some individuals are more uniformly round. From opposite sides of the body extends a pair of long, slender tentacles, each housed in a sheath into which it can be withdrawn. Some species of cydippids have bodies that are flattened to various extents so that they are wider in the plane of the tentacles.

The tentacles of cydippid ctenophores are typically fringed with tentilla ("little tentacles"), although a few genera have simple tentacles without these sidebranches. The tentacles and tentilla are densely covered with microscopic

Cydippid ctenophores have bodies that are more or less rounded, sometimes nearly spherical and other times more cylindrical or egg-shaped; the common coastal "sea gooseberry", '' Pleurobrachia'', sometimes has an egg-shaped body with the mouth at the narrow end, although some individuals are more uniformly round. From opposite sides of the body extends a pair of long, slender tentacles, each housed in a sheath into which it can be withdrawn. Some species of cydippids have bodies that are flattened to various extents so that they are wider in the plane of the tentacles.

The tentacles of cydippid ctenophores are typically fringed with tentilla ("little tentacles"), although a few genera have simple tentacles without these sidebranches. The tentacles and tentilla are densely covered with microscopic

phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

of marine invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they are the largest animals to swim with the help of cilia.

Depending on the species, adult ctenophores range from a few millimeter

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the electromagnetic spectrum, measured by the metre and its derived scales. The microwave is between 1 meter to 1 millimeter.

The millimetre (American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, ...

s to in size. Only 100 to 150 species have been validated, and possibly another 25 have not been fully described and named. The textbook examples are cydippids with egg-shaped bodies and a pair of retractable tentacles fringed with tentilla

In zoology, a tentacle is a flexible, mobile, and elongated organ present in some species of animals, most of them invertebrates. In animal anatomy, tentacles usually occur in one or more pairs. Anatomically, the tentacles of animals work main ...

("little tentacles") that are covered with colloblast Colloblasts are unique, multicellular structures found in ctenophores. They are widespread in the tentacles of these animals and are used to capture prey. Colloblasts consist of a collocyte containing a coiled spiral filament, internal granules and ...

s, sticky cells that capture prey.

Their bodies consist of a mass of jelly, with a layer two cells thick on the outside, and another lining the internal cavity. The phylum has a wide range of body forms, including the egg-shaped cydippids with retractable tentacles that capture prey, the flat generally combless platyctenids, and the large-mouthed beroids, which prey on other ctenophores.

Almost all ctenophores function as predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

s, taking prey ranging from microscopic larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

Th ...

e and rotifer

The rotifers (, from the Latin , "wheel", and , "bearing"), commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John Ha ...

s to the adults of small crustacea

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

ns; the exceptions are juveniles of two species, which live as parasites on the salp

A salp (plural salps, also known colloquially as “sea grape”) or salpa (plural salpae or salpas) is a barrel-shaped, planktic tunicate. It moves by contracting, thereby pumping water through its gelatinous body, one of the most efficient ...

s on which adults of their species feed.

Despite their soft, gelatinous bodies, fossils thought to represent ctenophores appear in lagerstätten dating as far back as the early Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ( ...

, about 525 million years ago. The position of the ctenophores in the "tree of life" has long been debated in molecular phylogenetics studies. Biologists proposed that ctenophores constitute the second-earliest branching animal lineage, with sponges being the sister-group to all other multicellular animals (Porifera Sister Hypothesis). Other biologists contend that ctenophores were emerging earlier than sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through ...

s (Ctenophora Sister Hypothesis), which themselves appeared before the split between cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that th ...

ns and bilateria

The Bilateria or bilaterians are animals with bilateral symmetry as an embryo, i.e. having a left and a right side that are mirror images of each other. This also means they have a head and a tail (anterior-posterior axis) as well as a belly and ...

ns. Pisani et al. reanalyzed of the data and suggest that the computer algorithms used for analysis were misled by the presence of specific ctenophore genes that were markedly different from those of other species. Follow up analysis by Whelan et al. (2017) yielded further support for the Ctenophora Sister hypothesis, and the issue remains a matter of taxonomic dispute.

Distinguishing features

Among animal phyla, the Ctenophores are more complex thansponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through ...

s, about as complex as cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that th ...

ns (jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella ...

, sea anemone

Sea anemones are a group of predatory marine invertebrates of the order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the '' Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classified in the phylum Cnidaria ...

s, etc.), and less complex than bilateria

The Bilateria or bilaterians are animals with bilateral symmetry as an embryo, i.e. having a left and a right side that are mirror images of each other. This also means they have a head and a tail (anterior-posterior axis) as well as a belly and ...

ns (which include almost all other animals). Unlike sponges, both ctenophores and cnidarians have: cells bound by inter-cell connections and carpet-like basement membrane

The basement membrane is a thin, pliable sheet-like type of extracellular matrix that provides cell and tissue support and acts as a platform for complex signalling. The basement membrane sits between epithelial tissues including mesothelium and ...

s; muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscle ...

s; nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes t ...

s; and some have sensory organs. Ctenophores are distinguished from all other animals by having colloblast Colloblasts are unique, multicellular structures found in ctenophores. They are widespread in the tentacles of these animals and are used to capture prey. Colloblasts consist of a collocyte containing a coiled spiral filament, internal granules and ...

s, which are sticky and adhere to prey, although a few ctenophore species lack them.

Like sponges and cnidarians, ctenophores have two main layers of cells that sandwich a middle layer of jelly-like material, which is called the mesoglea

Mesoglea refers to the extracellular matrix found in cnidarians like coral or jellyfish that functions as a hydrostatic skeleton. It is related to but distinct from mesohyl, which generally refers to extracellular material found in sponges.

Desc ...

in cnidarians and ctenophores; more complex animals have three main cell layers and no intermediate jelly-like layer. Hence ctenophores and cnidarians have traditionally been labelled diploblastic

Diploblasty is a condition of the blastula in which there are two primary germ layers: the ectoderm and endoderm.

Diploblastic organisms are organisms which develop from such a blastula, and include cnidaria and ctenophora

Ctenophora (; c ...

, along with sponges. Both ctenophores and cnidarians have a type of muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscle ...

that, in more complex animals, arises from the middle cell layer,

and as a result some recent text books classify ctenophores as triploblastic

Triploblasty is a condition of the gastrula in which there are three primary germ layers: the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Germ cells are set aside in the embryo at the blastula stage, which are incorporated into the gonads during organogenes ...

, while others still regard them as diploblastic. The comb jellies have more than 80 different cell type

A cell type is a classification used to identify cells that share morphological or phenotypical features. A multicellular organism may contain cells of a number of widely differing and specialized cell types, such as muscle cells and skin cells, ...

s, exceeding the numbers from other groups like placozoans, sponges, cnidarians, and some deep-branching bilaterians.

Ranging from about to in size, ctenophores are the largest non-colonial animals that use cilia ("hairs") as their main method of locomotion. Most species have eight strips, called comb rows, that run the length of their bodies and bear comb-like bands of cilia, called "ctenes", stacked along the comb rows so that when the cilia beat, those of each comb touch the comb below. The name "ctenophora" means "comb-bearing", from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''κτείς'' (stem-form κτεν-) meaning "comb" and the Greek suffix ''-φορος'' meaning "carrying".

Description

For a phylum with relatively few species, ctenophores have a wide range of body plans. Coastal species need to be tough enough to withstand waves and swirling sediment particles, while some oceanic species are so fragile that it is very difficult to capture them intact for study. In addition, oceanic species do not preserve well, and are known mainly from photographs and from observers' notes. Hence most attention has until recently concentrated on three coastalgenera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomencl ...

– '' Pleurobrachia'', '' Beroe'' and '' Mnemiopsis''. At least two textbooks base their descriptions of ctenophores on the cydippid ''Pleurobrachia''.

Since the body of many species is ''almost'' radially symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pl ...

, the main axis is oral

The word oral may refer to:

Relating to the mouth

* Relating to the mouth, the first portion of the alimentary canal that primarily receives food and liquid

**Oral administration of medicines

** Oral examination (also known as an oral exam or ora ...

to aboral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

(from the mouth to the opposite end). However, since only two of the canals near the statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, and crustaceans. A similar structure is also found in ''Xenoturbella''. The statocyst cons ...

terminate in anal

Anal may refer to:

Related to the anus

*Related to the anus of animals:

** Anal fin, in fish anatomy

** Anal vein, in insect anatomy

** Anal scale, in reptile anatomy

*Related to the human anus:

** Anal sex, a type of sexual activity involving ...

pores, ctenophores have no mirror-symmetry, although many have rotational symmetry. In other words, if the animal rotates in a half-circle it looks the same as when it started.

Common features

The Ctenophorephylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

has a wide range of body forms, including the flattened, deep-sea platyctenids, in which the adults of most species lack combs, and the coastal beroids, which lack tentacles and prey on other ctenophores by using huge mouths armed with groups of large, stiffened cilia that act as teeth.

Body layers

cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that th ...

ns, (jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella ...

, sea anemone

Sea anemones are a group of predatory marine invertebrates of the order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the '' Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classified in the phylum Cnidaria ...

s, etc.), ctenophores' bodies consist of a relatively thick, jelly-like mesoglea

Mesoglea refers to the extracellular matrix found in cnidarians like coral or jellyfish that functions as a hydrostatic skeleton. It is related to but distinct from mesohyl, which generally refers to extracellular material found in sponges.

Desc ...

sandwiched between two epithelia

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellu ...

, layers of cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

bound by inter-cell connections and by a fibrous basement membrane

The basement membrane is a thin, pliable sheet-like type of extracellular matrix that provides cell and tissue support and acts as a platform for complex signalling. The basement membrane sits between epithelial tissues including mesothelium and ...

that they secrete 440px

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical ...

. The epithelia of ctenophores have two layers of cells rather than one, and some of the cells in the upper layer have several cilia per cell.

The outer layer of the epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water relea ...

(outer skin) consists of: sensory cells; cells that secrete mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is ...

, which protects the body; and interstitial cells, which can transform into other types of cell. In specialized parts of the body, the outer layer also contains colloblast Colloblasts are unique, multicellular structures found in ctenophores. They are widespread in the tentacles of these animals and are used to capture prey. Colloblasts consist of a collocyte containing a coiled spiral filament, internal granules and ...

s, found along the surface of tentacles and used in capturing prey, or cells bearing multiple large cilia, for locomotion. The inner layer of the epidermis contains a nerve net, and myoepithelial cells that act as muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscle ...

s.

The internal cavity forms: a mouth that can usually be closed by muscles; a pharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its struct ...

("throat"); a wider area in the center that acts as a stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

; and a system of internal canals. These branch through the mesoglea to the most active parts of the animal: the mouth and pharynx; the roots of the tentacles, if present; all along the underside of each comb row; and four branches around the sensory complex at the far end from the mouth – two of these four branches terminate in anal

Anal may refer to:

Related to the anus

*Related to the anus of animals:

** Anal fin, in fish anatomy

** Anal vein, in insect anatomy

** Anal scale, in reptile anatomy

*Related to the human anus:

** Anal sex, a type of sexual activity involving ...

pores. The inner surface of the cavity is lined with an epithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellul ...

, the gastrodermis The gastrodermis is the inner layer of cells that serves as a lining membrane of the gastrovascular cavity of Cnidarians. The term is also used for the analogous inner epithelial layer of Ctenophore

Ctenophora (; ctenophore ; ) comprise a p ...

. The mouth and pharynx have both cilia and well-developed muscles. In other parts of the canal system, the gastrodermis is different on the sides nearest to and furthest from the organ that it supplies. The nearer side is composed of tall nutritive cells that store nutrients in vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

s (internal compartments), germ cell

Germ or germs may refer to:

Science

* Germ (microorganism), an informal word for a pathogen

* Germ cell, cell that gives rise to the gametes of an organism that reproduces sexually

* Germ layer, a primary layer of cells that forms during embr ...

s that produce eggs or sperm, and photocytes

A photocyte is a cell that specializes in catalyzing enzymes to produce light (bioluminescence). Photocytes typically occur in select layers of epithelial tissue, functioning singly or in a group, or as part of a larger apparatus (a photophore). ...

that produce bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some ...

. The side furthest from the organ is covered with ciliated cells that circulate water through the canals, punctuated by ciliary rosettes, pores that are surrounded by double whorls of cilia and connect to the mesoglea.

Feeding, excretion and respiration

When prey is swallowed, it is liquefied in thepharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its struct ...

by enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. ...

s and by muscular contractions of the pharynx. The resulting slurry is wafted through the canal system by the beating of the cilia, and digested by the nutritive cells. The ciliary rosettes in the canals may help to transport nutrients to muscles in the mesoglea. The anal

Anal may refer to:

Related to the anus

*Related to the anus of animals:

** Anal fin, in fish anatomy

** Anal vein, in insect anatomy

** Anal scale, in reptile anatomy

*Related to the human anus:

** Anal sex, a type of sexual activity involving ...

pores may eject unwanted small particles, but most unwanted matter is regurgitated via the mouth.

Little is known about how ctenophores get rid of waste products produced by the cells. The ciliary rosettes in the gastrodermis The gastrodermis is the inner layer of cells that serves as a lining membrane of the gastrovascular cavity of Cnidarians. The term is also used for the analogous inner epithelial layer of Ctenophore

Ctenophora (; ctenophore ; ) comprise a p ...

may help to remove wastes from the mesoglea, and may also help to adjust the animal's buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the pr ...

by pumping water into or out of the mesoglea.

Locomotion

The outer surface bears usually eight comb rows, called swimming-plates, which are used for swimming. The rows are oriented to run from near the mouth (the "oral pole") to the opposite end (the "aboral pole"), and are spaced more or less evenly around the body, although spacing patterns vary by species and in most species the comb rows extend only part of the distance from the aboral pole towards the mouth. The "combs" (also called "ctenes" or "comb plates") run across each row, and each consists of thousands of unusually long cilia, up to . Unlike conventional cilia and flagella, which has afilament

The word filament, which is descended from Latin ''filum'' meaning " thread", is used in English for a variety of thread-like structures, including:

Astronomy

* Galaxy filament, the largest known cosmic structures in the universe

* Solar filament ...

structure arranged in a 9 + 2 pattern, these cilia are arranged in a 9 + 3 pattern, where the extra compact filament is suspected to have a supporting function. These normally beat so that the propulsion stroke is away from the mouth, although they can also reverse direction. Hence ctenophores usually swim in the direction in which the mouth is eating, unlike jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella ...

. When trying to escape predators, one species can accelerate to six times its normal speed; some other species reverse direction as part of their escape behavior, by reversing the power stroke of the comb plate cilia.

It is uncertain how ctenophores control their buoyancy, but experiments have shown that some species rely on osmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.

It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a solution to take in a pure ...

to adapt to the water of different densities. Their body fluids are normally as concentrated as seawater. If they enter less dense brackish water, the ciliary rosettes in the body cavity may pump this into the mesoglea

Mesoglea refers to the extracellular matrix found in cnidarians like coral or jellyfish that functions as a hydrostatic skeleton. It is related to but distinct from mesohyl, which generally refers to extracellular material found in sponges.

Desc ...

to increase its bulk and decrease its density, to avoid sinking. Conversely, if they move from brackish to full-strength seawater, the rosettes may pump water out of the mesoglea to reduce its volume and increase its density.

Nervous system and senses

Ctenophores have no brain orcentral nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all par ...

, but instead have a nerve net (rather like a cobweb) that forms a ring round the mouth and is densest near structures such as the comb rows, pharynx, tentacles (if present) and the sensory complex furthest from the mouth. Fossils shows that Cambrian species had a more complex nervous system, with long nerves which connected with a ring around the mouth. The only known ctenophores with long nerves today is ''Euplokamis

''Euplokamis'' is a genus of ctenophores, or comb jellies, belonging to the monotypic family Euplokamididae. Despite living for hundreds of millions of years in marine environments, there is minimal research regarding ''Euplokamis'', primarily d ...

'' in the order Cydippida. Their nerve cells arise from the same progenitor cell

A progenitor cell is a biological cell that can differentiate into a specific cell type. Stem cells and progenitor cells have this ability in common. However, stem cells are less specified than progenitor cells. Progenitor cells can only differe ...

s as the colloblasts.

The largest single sensory feature is the aboral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

organ (at the opposite end from the mouth). Its main component is a statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, and crustaceans. A similar structure is also found in ''Xenoturbella''. The statocyst cons ...

, a balance sensor consisting of a statolith, a tiny grain of calcium carbonate, supported on four bundles of cilia, called "balancers", that sense its orientation. The statocyst is protected by a transparent dome made of long, immobile cilia. A ctenophore does not automatically try to keep the statolith resting equally on all the balancers. Instead, its response is determined by the animal's "mood", in other words, the overall state of the nervous system. For example, if a ctenophore with trailing tentacles captures prey, it will often put some comb rows into reverse, spinning the mouth towards the prey.

Research supports the hypothesis that the ciliated larvae in cnidarians and bilaterians share an ancient and common origin. The larvae's apical organ is involved in the formation of the nervous system. The aboral organ of comb jellies is not homologous with the apical organ in other animals, and the formation of their nervous system has therefore a different embryonic origin.

Ctenophore nerve cells and nervous system have different biochemistry as compared to other animals. For instance, they lack the genes and enzymes required to manufacture neurotransmitters like serotonin

Serotonin () or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Its biological function is complex and multifaceted, modulating mood, cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes such as vomiting and vas ...

, dopamine

Dopamine (DA, a contraction of 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine) is a neuromodulatory molecule that plays several important roles in cells. It is an organic chemical of the catecholamine and phenethylamine families. Dopamine constitutes about 80% o ...

, nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its ch ...

, octopamine

Octopamine (molecular formula C8H11NO2; also known as OA, and also norsynephrine, ''para''-octopamine and others) is an organic chemical closely related to norepinephrine, and synthesized biologically by a homologous pathway. Octopamine is oft ...

, noradrenaline

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline (NA) or noradrenalin, is an organic chemical in the catecholamine family that functions in the brain and body as both a hormone and neurotransmitter. The name "noradrenaline" (from Latin '' ad'', ...

, and others, otherwise seen in all other animals with a nervous system, with the genes coding for the receptors for each of these neurotransmitters missing. They have been found to use L-glutamate

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; the ionic form is known as glutamate) is an α-amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that the human body can synt ...

as a neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, any main body part or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotr ...

, and have an unusually high variety of ionotropic glutamate receptors and genes for glutamate synthesis and transport compared to other metazoans. The genomic content of the nervous system genes is the smallest known of any animal, and could represent the minimum genetic requirements for a functional nervous system. Therefore, if ctenophores are the sister group to all other metazoans, nervous systems may have either been lost in sponges and placozoans, or arisen more than once among metazoans.

Cydippids

Cydippid ctenophores have bodies that are more or less rounded, sometimes nearly spherical and other times more cylindrical or egg-shaped; the common coastal "sea gooseberry", '' Pleurobrachia'', sometimes has an egg-shaped body with the mouth at the narrow end, although some individuals are more uniformly round. From opposite sides of the body extends a pair of long, slender tentacles, each housed in a sheath into which it can be withdrawn. Some species of cydippids have bodies that are flattened to various extents so that they are wider in the plane of the tentacles.

The tentacles of cydippid ctenophores are typically fringed with tentilla ("little tentacles"), although a few genera have simple tentacles without these sidebranches. The tentacles and tentilla are densely covered with microscopic

Cydippid ctenophores have bodies that are more or less rounded, sometimes nearly spherical and other times more cylindrical or egg-shaped; the common coastal "sea gooseberry", '' Pleurobrachia'', sometimes has an egg-shaped body with the mouth at the narrow end, although some individuals are more uniformly round. From opposite sides of the body extends a pair of long, slender tentacles, each housed in a sheath into which it can be withdrawn. Some species of cydippids have bodies that are flattened to various extents so that they are wider in the plane of the tentacles.

The tentacles of cydippid ctenophores are typically fringed with tentilla ("little tentacles"), although a few genera have simple tentacles without these sidebranches. The tentacles and tentilla are densely covered with microscopic colloblast Colloblasts are unique, multicellular structures found in ctenophores. They are widespread in the tentacles of these animals and are used to capture prey. Colloblasts consist of a collocyte containing a coiled spiral filament, internal granules and ...

s that capture prey by sticking to it. Colloblasts are specialized mushroom

A mushroom or toadstool is the fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting body of a fungus, typically produced above ground, on soil, or on its food source. ''Toadstool'' generally denotes one poisonous to humans.

The standard for the name "mushroom" is t ...

-shaped cells in the outer layer of the epidermis, and have three main components: a domed head with vesicles (chambers) that contain adhesive; a stalk that anchors the cell in the lower layer of the epidermis or in the mesoglea; and a spiral

In mathematics, a spiral is a curve which emanates from a point, moving farther away as it revolves around the point.

Helices

Two major definitions of "spiral" in the American Heritage Dictionary are:

In addition to colloblasts, members of the genus ''

The

The

The Beroida, also known as

The Beroida, also known as

Adults of most species can regenerate tissues that are damaged or removed, although only platyctenids reproduce by

Adults of most species can regenerate tissues that are damaged or removed, although only platyctenids reproduce by

Most ctenophores that live near the surface are mostly colorless and almost transparent. However some deeper-living species are strongly pigmented, for example the species known as "Tortugas red" (see illustration here), which has not yet been formally described. Platyctenids generally live attached to other sea-bottom organisms, and often have similar colors to these host organisms. The gut of the deep-sea genus '' Bathocyroe'' is red, which hides the

Most ctenophores that live near the surface are mostly colorless and almost transparent. However some deeper-living species are strongly pigmented, for example the species known as "Tortugas red" (see illustration here), which has not yet been formally described. Platyctenids generally live attached to other sea-bottom organisms, and often have similar colors to these host organisms. The gut of the deep-sea genus '' Bathocyroe'' is red, which hides the

Ctenophores may balance marine ecosystems by preventing an over-abundance of copepods from eating all the phytoplankton (planktonic plants), which are the dominant marine producers of organic matter from non-organic ingredients.

On the other hand, in the late 1980s the Western Atlantic ctenophore ''

Ctenophores may balance marine ecosystems by preventing an over-abundance of copepods from eating all the phytoplankton (planktonic plants), which are the dominant marine producers of organic matter from non-organic ingredients.

On the other hand, in the late 1980s the Western Atlantic ctenophore ''

The traditional classification divides ctenophores into two classes, those with tentacles (

The traditional classification divides ctenophores into two classes, those with tentacles (

"Aliens in our midst: What the ctenophore says about the evolution of intelligence"

2017, Aeon.co.

Plankton Chronicles

Short documentary films & photos

Jellyfish and Comb Jellies

overview at the Smithsonian Ocean Portal

Video of ctenophores at the National Zoo in Washington DC

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20080720150947/http://www.tafi.org.au/zooplankton/imagekey/ctenophora/index.html Australian Ctenophora Fact Sheetbr>The Jelly Connection

– striking images, including a ''Beroe'' specimen attacking another ctenophore

In Search of the First Animals

{{Authority control Bioluminescent ctenophores Articles containing video clips Animal phyla Cambrian Series 2 first appearances Extant Cambrian first appearances

Haeckelia

''Haeckelia'' is a genus of ctenophore

Ctenophora (; ctenophore ; ) comprise a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swi ...

'', which feed mainly on jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella ...

, incorporate their victims' stinging nematocyte

A cnidocyte (also known as a cnidoblast or nematocyte) is an explosive cell containing one large secretory organelle called a cnidocyst (also known as a cnida () or nematocyst) that can deliver a sting to other organisms. The presence of this ce ...

s into their own tentacles – some cnidaria-eating nudibranch

Nudibranchs () are a group of soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs which shed their shells after their larval stage. They are noted for their often extraordinary colours and striking forms, and they have been given colourful nicknames to match ...

s similarly incorporate nematocytes into their bodies for defense. The tentilla of ''Euplokamis

''Euplokamis'' is a genus of ctenophores, or comb jellies, belonging to the monotypic family Euplokamididae. Despite living for hundreds of millions of years in marine environments, there is minimal research regarding ''Euplokamis'', primarily d ...

'' differ significantly from those of other cydippids: they contain striated muscle

Striations means a series of ridges, furrows or linear marks, and is used in several ways:

* Glacial striation

* Striation (fatigue), in material

* Striation (geology), a ''striation'' as a result of a geological fault

* Striation Valley, in Anta ...

, a cell type otherwise unknown in the phylum Ctenophora; and they are coiled when relaxed, while the tentilla of all other known ctenophores elongate when relaxed. ''Euplokamis tentilla have three types of movement that are used in capturing prey: they may flick out very quickly (in 40 to 60 millisecond

A millisecond (from ''milli-'' and second; symbol: ms) is a unit of time in the International System of Units (SI) equal to one thousandth (0.001 or 10−3 or 1/1000) of a second and to 1000 microseconds.

A unit of 10 milliseconds may be called ...

s); they can wriggle, which may lure prey by behaving like small planktonic worms; and they coil round prey. The unique flicking is an uncoiling movement powered by contraction of the striated muscle

Striations means a series of ridges, furrows or linear marks, and is used in several ways:

* Glacial striation

* Striation (fatigue), in material

* Striation (geology), a ''striation'' as a result of a geological fault

* Striation Valley, in Anta ...

. The wriggling motion is produced by smooth muscles, but of a highly specialized type. Coiling around prey is accomplished largely by the return of the tentilla to their inactive state, but the coils may be tightened by smooth muscle.

There are eight rows of combs that run from near the mouth to the opposite end, and are spaced evenly round the body. The "combs" beat in a metachronal rhythm

A metachronal rhythm or metachronal wave refers to wavy movements produced by the sequential action (as opposed to synchronized) of structures such as cilia, segments of worms, or legs. These movements produce the appearance of a travelling wave. ...

rather like that of a Mexican wave

The wave (known as a Mexican wave or stadium wave outside of North America) is an example of metachronal rhythm achieved in a packed stadium when successive groups of spectators briefly stand, yell, and raise their arms. Immediately upon stre ...

. From each balancer in the statocyst a ciliary groove runs out under the dome and then splits to connect with two adjacent comb rows, and in some species runs along the comb rows. This forms a ''mechanical'' system for transmitting the beat rhythm from the combs to the balancers, via water disturbances created by the cilia.

Lobates

The

The Lobata

Lobata is an order of Ctenophora in the class Tentaculata with smaller tentacles than other ctenophores, and distinctive flattened lobes extending outwards from their bodies.

They grow up to about long.

Anatomy

The lobates have a pair of lo ...

has a pair of lobes, which are muscular, cuplike extensions of the body that project beyond the mouth. Their inconspicuous tentacles originate from the corners of the mouth, running in convoluted grooves and spreading out over the inner surface of the lobes (rather than trailing far behind, as in the Cydippida). Between the lobes on either side of the mouth, many species of lobates have four auricles, gelatinous projections edged with cilia that produce water currents that help direct microscopic prey toward the mouth. This combination of structures enables lobates to feed continuously on suspended plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

ic prey.

Lobates have eight comb-rows, originating at the aboral pole and usually not extending beyond the body to the lobes; in species with (four) auricles, the cilia edging the auricles are extensions of cilia in four of the comb rows. Most lobates are quite passive when moving through the water, using the cilia on their comb rows for propulsion, although ''Leucothea'' has long and active auricles whose movements also contribute to propulsion. Members of the lobate genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomencl ...

'' Bathocyroe'' and '' Ocyropsis'' can escape from danger by clapping their lobes, so that the jet of expelled water drives them back very quickly. Unlike cydippids, the movements of lobates' combs are coordinated by nerves rather than by water disturbances created by the cilia, yet combs on the same row beat in the same Mexican wave

The wave (known as a Mexican wave or stadium wave outside of North America) is an example of metachronal rhythm achieved in a packed stadium when successive groups of spectators briefly stand, yell, and raise their arms. Immediately upon stre ...

style as the mechanically coordinated comb rows of cydippids and beroids. This may have enabled lobates to grow larger than cydippids and to have less egg-like shapes.

An unusual species first described in 2000, ''Lobatolampea tetragona'', has been classified as a lobate, although the lobes are "primitive" and the body is medusa

In Greek mythology, Medusa (; Ancient Greek: Μέδουσα "guardian, protectress"), also called Gorgo, was one of the three monstrous Gorgons, generally described as winged human females with living venomous snakes in place of hair. Thos ...

-like when floating and disk-like when resting on the sea-bed.

Beroids

The Beroida, also known as

The Beroida, also known as Nuda

Beroidae is a family of ctenophores or comb jellies more commonly referred to as the beroids. It is the only family within the monotypic order Beroida and the class Nuda. They are distinguished from other comb jellies by the complete absence of ...

, have no feeding appendages, but their large pharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its struct ...

, just inside the large mouth and filling most of the saclike body, bears "macrocilia" at the oral end. These fused bundles of several thousand large cilia are able to "bite" off pieces of prey that are too large to swallow whole – almost always other ctenophores. In front of the field of macrocilia, on the mouth "lips" in some species of ''Beroe'', is a pair of narrow strips of adhesive epithelial cells on the stomach wall that "zip" the mouth shut when the animal is not feeding, by forming intercellular connections with the opposite adhesive strip. This tight closure streamlines the front of the animal when it is pursuing prey.

Other body forms

The Ganeshida has a pair of small oral lobes and a pair of tentacles. The body is circular rather than oval in cross-section, and the pharynx extends over the inner surfaces of the lobes. The Thalassocalycida, only discovered in 1978 and known from only one species, are medusa-like, with bodies that are shortened in the oral-aboral direction, and short comb-rows on the surface furthest from the mouth, originating from near the aboral pole. They capture prey by movements of the bell and possibly by using two short tentacles. TheCestida

Cestidae is a family of comb jellies. It is the only family in the monotypic order Cestida. Unlike other comb jellies, the body of cestids is greatly flattened, and drawn out into a long ribbon-like shape. The two tentacles are greatly shortened, ...

("belt animals") are ribbon-shaped planktonic animals, with the mouth and aboral organ aligned in the middle of opposite edges of the ribbon. There is a pair of comb-rows along each aboral edge, and tentilla emerging from a groove all along the oral edge, which stream back across most of the wing-like body surface. Cestids can swim by undulating their bodies as well as by the beating of their comb-rows. There are two known species, with worldwide distribution in warm, and warm-temperate waters: '' Cestum veneris'' ("Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

' girdle") is among the largest ctenophores – up to long, and can undulate slowly or quite rapidly. ''Velamen parallelum'', which is typically less than long, can move much faster in what has been described as a "darting motion".

Most Platyctenida have oval bodies that are flattened in the oral-aboral direction, with a pair of tentilla-bearing tentacles on the aboral surface. They cling to and creep on surfaces by everting the pharynx and using it as a muscular "foot". All but one of the known platyctenid species lack comb-rows. Platyctenids are usually cryptically colored, live on rocks, algae, or the body surfaces of other invertebrates, and are often revealed by their long tentacles with many side branches, seen streaming off the back of the ctenophore into the current.

Reproduction and development

Adults of most species can regenerate tissues that are damaged or removed, although only platyctenids reproduce by

Adults of most species can regenerate tissues that are damaged or removed, although only platyctenids reproduce by cloning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, c ...

, splitting off from the edges of their flat bodies fragments that develop into new individuals.

The last common ancestor (LCA) of the ctenophores was hermaphroditic

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have sepa ...

. Some are simultaneous hermaphrodites, which can produce both eggs and sperm at the same time, while others are sequential hermaphrodites, in which the eggs and sperm mature at different times. There is no metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation. Some insec ...

. At least three species are known to have evolved separate sexes (dioecy

Dioecy (; ; adj. dioecious , ) is a characteristic of a species, meaning that it has distinct individual organisms (unisexual) that produce male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproducti ...

); ''Ocyropsis crystallina'' and ''Ocyropsis maculata'' in the genus Ocyropsis and ''Bathocyroe fosteri'' in the genus Bathocyroe. The gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a mixed gland that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gonad, the testicle, produces sperm ...

s are located in the parts of the internal canal network under the comb rows, and eggs and sperm are released via pores in the epidermis. Fertilization is generally external, but platyctenids use internal fertilization and keep the eggs in brood chambers until they hatch. Self-fertilization has occasionally been seen in species of the genus '' Mnemiopsis'', and it is thought that most of the hermaphroditic species are self-fertile.

Development of the fertilized eggs is direct; there is no distinctive larval form. Juveniles of all groups are generally plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

ic, and most species resemble miniature adult cydippids, gradually developing their adult body forms as they grow. In the genus ''Beroe'', however, the juveniles have large mouths and, like the adults, lack both tentacles and tentacle sheaths. In some groups, such as the flat, bottom-dwelling platyctenids, the juveniles behave more like true larvae. They live among the plankton and thus occupy a different ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

from their parents, only attaining the adult form by a more radical ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...

. after dropping to the sea-floor.

At least in some species, juvenile ctenophores appear capable of producing small quantities of eggs and sperm while they are well below adult size, and adults produce eggs and sperm for as long as they have sufficient food. If they run short of food, they first stop producing eggs and sperm, and then shrink in size. When the food supply improves, they grow back to normal size and then resume reproduction. These features make ctenophores capable of increasing their populations very quickly. Members of the Lobata and Cydippida also have a reproduction form called dissogeny; two sexually mature stages, first as larva and later as juveniles and adults. During their time as larva they are capable of releasing gametes periodically. After their first reproductive period is over they will not produce more gametes again until later. A population of ''Mertensia ovum'' in the central Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

have become paedogenetic, and consist solely of sexually mature larvae less than 1.6 mm.

Colors and bioluminescence

Most ctenophores that live near the surface are mostly colorless and almost transparent. However some deeper-living species are strongly pigmented, for example the species known as "Tortugas red" (see illustration here), which has not yet been formally described. Platyctenids generally live attached to other sea-bottom organisms, and often have similar colors to these host organisms. The gut of the deep-sea genus '' Bathocyroe'' is red, which hides the

Most ctenophores that live near the surface are mostly colorless and almost transparent. However some deeper-living species are strongly pigmented, for example the species known as "Tortugas red" (see illustration here), which has not yet been formally described. Platyctenids generally live attached to other sea-bottom organisms, and often have similar colors to these host organisms. The gut of the deep-sea genus '' Bathocyroe'' is red, which hides the bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some ...

of copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s it has swallowed.

The comb rows of most planktonic ctenophores produce a rainbow effect, which is not caused by bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some ...

but by the scattering of light as the combs move. Most species are also bioluminescent, but the light is usually blue or green and can only be seen in darkness. However some significant groups, including all known platyctenids and the cydippid genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomencla ...

'' Pleurobrachia'', are incapable of bioluminescence.

When some species, including '' Bathyctena chuni'', '' Euplokamis stationis'' and '' Eurhamphaea vexilligera'', are disturbed, they produce secretions (ink) that luminesce at much the same wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tro ...

s as their bodies. Juveniles will luminesce more brightly in relation to their body size than adults, whose luminescence is diffused over their bodies. Detailed statistical investigation has not suggested the function of ctenophores' bioluminescence nor produced any correlation between its exact color and any aspect of the animals' environments, such as depth or whether they live in coastal or mid-ocean waters.

In ctenophores, bioluminescence is caused by the activation of calcium-activated proteins named photoproteins in cells called photocytes

A photocyte is a cell that specializes in catalyzing enzymes to produce light (bioluminescence). Photocytes typically occur in select layers of epithelial tissue, functioning singly or in a group, or as part of a larger apparatus (a photophore). ...

, which are often confined to the meridional canals that underlie the eight comb rows. In the genome of ''Mnemiopsis leidyi

''Mnemiopsis leidyi'', the warty comb jelly or sea walnut, is a species of tentaculate ctenophore (comb jelly). It is native to western Atlantic coastal waters, but has become established as an invasive species in European and western Asian regi ...

'' ten genes encode photoproteins. These genes are co-expressed with opsin

Animal opsins are G-protein-coupled receptors and a group of proteins made light-sensitive via a chromophore, typically retinal. When bound to retinal, opsins become Retinylidene proteins, but are usually still called opsins regardless. Most p ...

genes in the developing photocytes of ''Mnemiopsis leidyi'', raising the possibility that light production and light detection may be working together in these animals.

Ecology

Distribution

Ctenophores are found in most marine environments: from polar waters to the tropics; near coasts and in mid-ocean; from the surface waters to the ocean depths. The best-understood are thegenera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomencl ...

''Pleurobrachia'', ''Beroe'' and '' Mnemiopsis'', as these plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

ic coastal forms are among the most likely to be collected near shore. No ctenophores have been found in fresh water.

In 2013, the marine ctenophore ''Mnemiopsis leidyi

''Mnemiopsis leidyi'', the warty comb jelly or sea walnut, is a species of tentaculate ctenophore (comb jelly). It is native to western Atlantic coastal waters, but has become established as an invasive species in European and western Asian regi ...

'' was recorded in a lake in Egypt, accidentally introduced by the transport of fish (mullet) fry; this was the first record from a true lake, though other species are found in the brackish water of coastal lagoons and estuaries.

Ctenophores may be abundant during the summer months in some coastal locations, but in other places, they are uncommon and difficult to find.

In bays where they occur in very high numbers, predation by ctenophores may control the populations of small zooplanktonic organisms such as copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s, which might otherwise wipe out the phytoplankton (planktonic plants), which are a vital part of marine food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), det ...

s.

Prey and predators

Almost all ctenophores arepredator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

s – there are no vegetarians and only one genus that is partly parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

. If food is plentiful, they can eat 10 times their own weight per day. While ''Beroe'' preys mainly on other ctenophores, other surface-water species prey on zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

(planktonic animals) ranging in size from the microscopic, including mollusc and fish larvae, to small adult crustaceans such as copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s, amphipod

Amphipoda is an order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 9,900 amphipod species so far descri ...

s, and even krill

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word ', meaning "small fry of fish", which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are cons ...

. Members of the genus ''Haeckelia

''Haeckelia'' is a genus of ctenophore

Ctenophora (; ctenophore ; ) comprise a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swi ...

'' prey on jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella ...

and incorporate their prey's nematocyst

A cnidocyte (also known as a cnidoblast or nematocyte) is an explosive cell containing one large secretory organelle called a cnidocyst (also known as a cnida () or nematocyst) that can deliver a sting to other organisms. The presence of this c ...

s (stinging cells) into their own tentacles instead of colloblast Colloblasts are unique, multicellular structures found in ctenophores. They are widespread in the tentacles of these animals and are used to capture prey. Colloblasts consist of a collocyte containing a coiled spiral filament, internal granules and ...

s. Ctenophores have been compared to spider

Spiders ( order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species div ...

s in their wide range of techniques for capturing prey – some hang motionless in the water using their tentacles as "webs", some are ambush predators like Salticid jumping spider

Jumping spiders are a group of spiders that constitute the family Salticidae. As of 2019, this family contained over 600 described genera and over 6,000 described species, making it the largest family of spiders at 13% of all species. Jumping spi ...

s, and some dangle a sticky droplet at the end of a fine thread, as bolas spider

A bolas spider is a member of the orb-weaver spider (family Araneidae) that, instead of spinning a typical orb web, hunts by using one or more sticky "capture blobs" on the end of a silk line, known as a " bolas". By swinging the bolas at flying ...

s do. This variety explains the wide range of body forms in a phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

with rather few species. The two-tentacled "cydippid" ''Lampea'' feeds exclusively on salp

A salp (plural salps, also known colloquially as “sea grape”) or salpa (plural salpae or salpas) is a barrel-shaped, planktic tunicate. It moves by contracting, thereby pumping water through its gelatinous body, one of the most efficient ...

s, close relatives of sea-squirts that form large chain-like floating colonies, and juveniles of ''Lampea'' attach themselves like parasites to salps that are too large for them to swallow. Members of the cydippid genus '' Pleurobrachia'' and the lobate '' Bolinopsis'' often reach high population densities at the same place and time because they specialize in different types of prey: '' Pleurobrachias long tentacles mainly capture relatively strong swimmers such as adult copepods, while '' Bolinopsis'' generally feeds on smaller, weaker swimmers such as rotifer

The rotifers (, from the Latin , "wheel", and , "bearing"), commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John Ha ...

s and mollusc and crustacean larvae

Crustaceans may pass through a number of larval and immature stages between hatching from their eggs and reaching their adult form. Each of the stages is separated by a moult, in which the hard exoskeleton is shed to allow the animal to grow. The ...

.

Ctenophores used to be regarded as "dead ends" in marine food chains because it was thought their low ratio of organic matter to salt and water made them a poor diet for other animals. It is also often difficult to identify the remains of ctenophores in the guts of possible predators, although the combs sometimes remain intact long enough to provide a clue. Detailed investigation of chum salmon

The chum salmon (''Oncorhynchus keta''), also known as dog salmon or keta salmon, is a species of anadromous salmonid fish from the genus ''Oncorhynchus'' (Pacific salmon) native to the coastal rivers of the North Pacific and the Beringian Arcti ...

, ''Oncorhynchus keta'', showed that these fish digest ctenophores 20 times as fast as an equal weight of shrimp

Shrimp are crustaceans (a form of shellfish) with elongated bodies and a primarily swimming mode of locomotion – most commonly Caridea and Dendrobranchiata of the decapod order, although some crustaceans outside of this order are referre ...

s, and that ctenophores can provide a good diet if there are enough of them around. Beroids prey mainly on other ctenophores. Some jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella ...

and turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked t ...

s eat large quantities of ctenophores, and jellyfish may temporarily wipe out ctenophore populations. Since ctenophores and jellyfish often have large seasonal variations in population, most fish that prey on them are generalists and may have a greater effect on populations than the specialist jelly-eaters. This is underlined by an observation of herbivorous fishes deliberately feeding on gelatinous zooplankton during blooms in the Red Sea. The larvae of some sea anemone

Sea anemones are a group of predatory marine invertebrates of the order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the '' Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classified in the phylum Cnidaria ...

s are parasites on ctenophores, as are the larvae of some flatworm

The flatworms, flat worms, Platyhelminthes, or platyhelminths (from the Greek πλατύ, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") are a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegment ...

s that parasitize fish when they reach adulthood.

Ecological impacts

Most species arehermaphrodites

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have s ...

, and juveniles of at least some species are capable of reproduction before reaching the adult size and shape. This combination of hermaphroditism and early reproduction enables small populations to grow at an explosive rate.

Ctenophores may balance marine ecosystems by preventing an over-abundance of copepods from eating all the phytoplankton (planktonic plants), which are the dominant marine producers of organic matter from non-organic ingredients.

On the other hand, in the late 1980s the Western Atlantic ctenophore ''

Ctenophores may balance marine ecosystems by preventing an over-abundance of copepods from eating all the phytoplankton (planktonic plants), which are the dominant marine producers of organic matter from non-organic ingredients.

On the other hand, in the late 1980s the Western Atlantic ctenophore ''Mnemiopsis leidyi

''Mnemiopsis leidyi'', the warty comb jelly or sea walnut, is a species of tentaculate ctenophore (comb jelly). It is native to western Atlantic coastal waters, but has become established as an invasive species in European and western Asian regi ...

'' was accidentally introduced into the Black Sea and Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

via the ballast tanks of ships, and has been blamed for causing sharp drops in fish catches by eating both fish larvae and small crustaceans that would otherwise feed the adult fish. ''Mnemiopsis'' is well equipped to invade new territories (although this was not predicted until after it so successfully colonized the Black Sea), as it can breed very rapidly and tolerate a wide range of water temperatures and salinities

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal to ...

. The impact was increased by chronic overfishing, and by eutrophication

Eutrophication is the process by which an entire body of water, or parts of it, becomes progressively enriched with minerals and nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. It has also been defined as "nutrient-induced increase in phytoplan ...

that gave the entire ecosystem a short-term boost, causing the ''Mnemiopsis'' population to increase even faster than normal – and above all by the absence of efficient predators on these introduced ctenophores. ''Mnemiopsis'' populations in those areas were eventually brought under control by the accidental introduction of the ''Mnemiopsis''-eating North American ctenophore '' Beroe ovata'', and by a cooling of the local climate from 1991 to 1993, which significantly slowed the animal's metabolism. However the abundance of plankton in the area seems unlikely to be restored to pre-''Mnemiopsis'' levels.

In the late 1990s ''Mnemiopsis'' appeared in the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asi ...

. ''Beroe ovata'' arrived shortly after, and is expected to reduce but not eliminate the impact of ''Mnemiopsis'' there. ''Mnemiopsis'' also reached the eastern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

in the late 1990s and now appears to be thriving in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegia ...

and Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

.

Taxonomy

The number of known living ctenophore species is uncertain since many of those named and formally described have turned out to be identical to species known under other scientific names. Claudia Mills estimates that there about 100 to 150 valid species that are not duplicates, and that at least another 25, mostly deep-sea forms, have been recognized as distinct but not yet analyzed in enough detail to support a formal description and naming.Early classification

Early writers combined ctenophores withcnidarians

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that th ...

into a single phylum called Coelenterata

Coelenterata is a term encompassing the animal phyla Cnidaria (coral animals, true jellies, sea anemones, sea pens, and their relatives) and Ctenophora (comb jellies). The name comes , referring to the hollow body cavity common to these two ph ...

on account of morphological similarities between the two groups. Like cnidarians, the bodies of ctenophores consist of a mass of jelly, with one layer of cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...