Cinchona on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cinchona'' (pronounced or ) is a

Selected Rubiaceae Tribes and Genera. Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden.

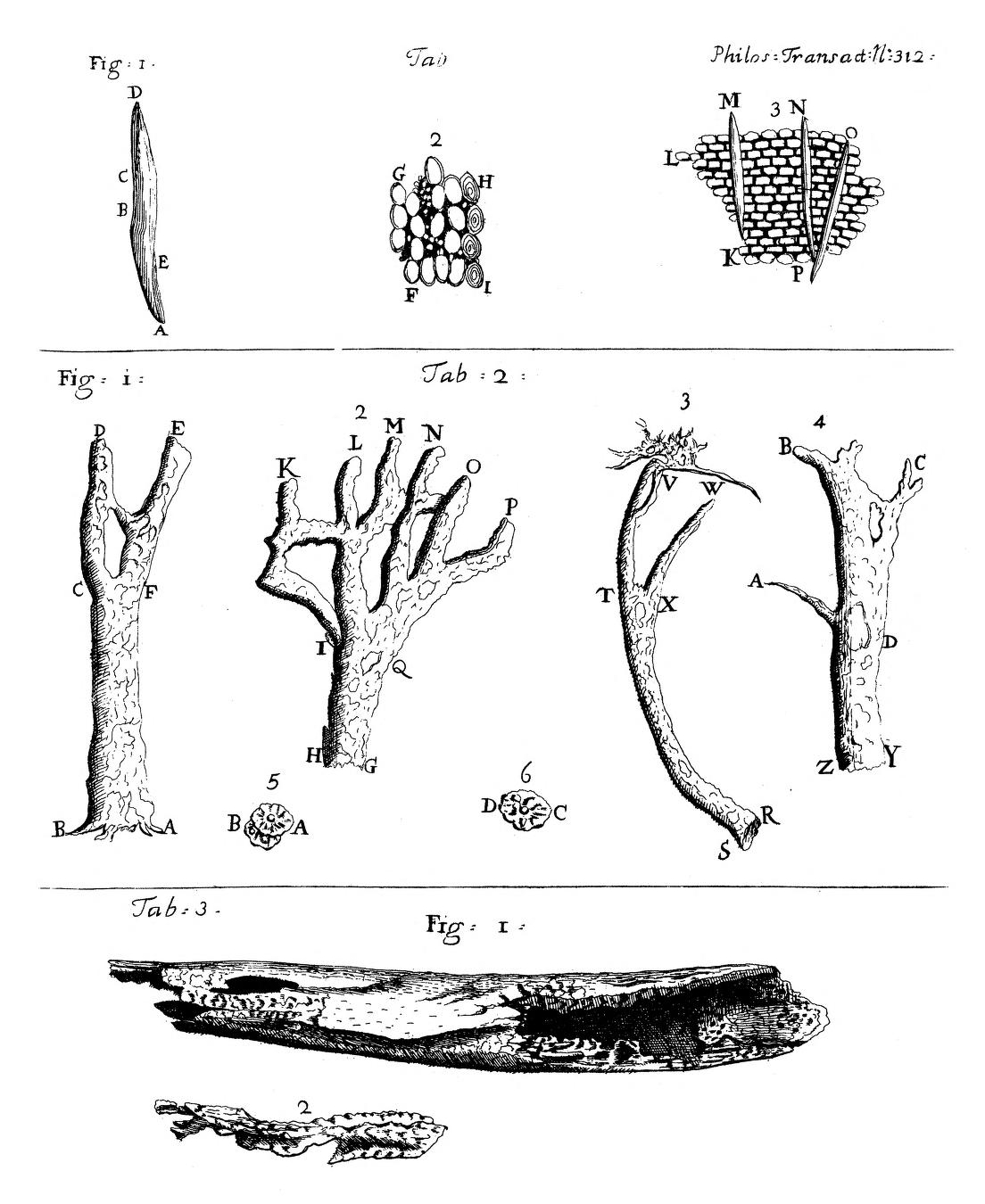

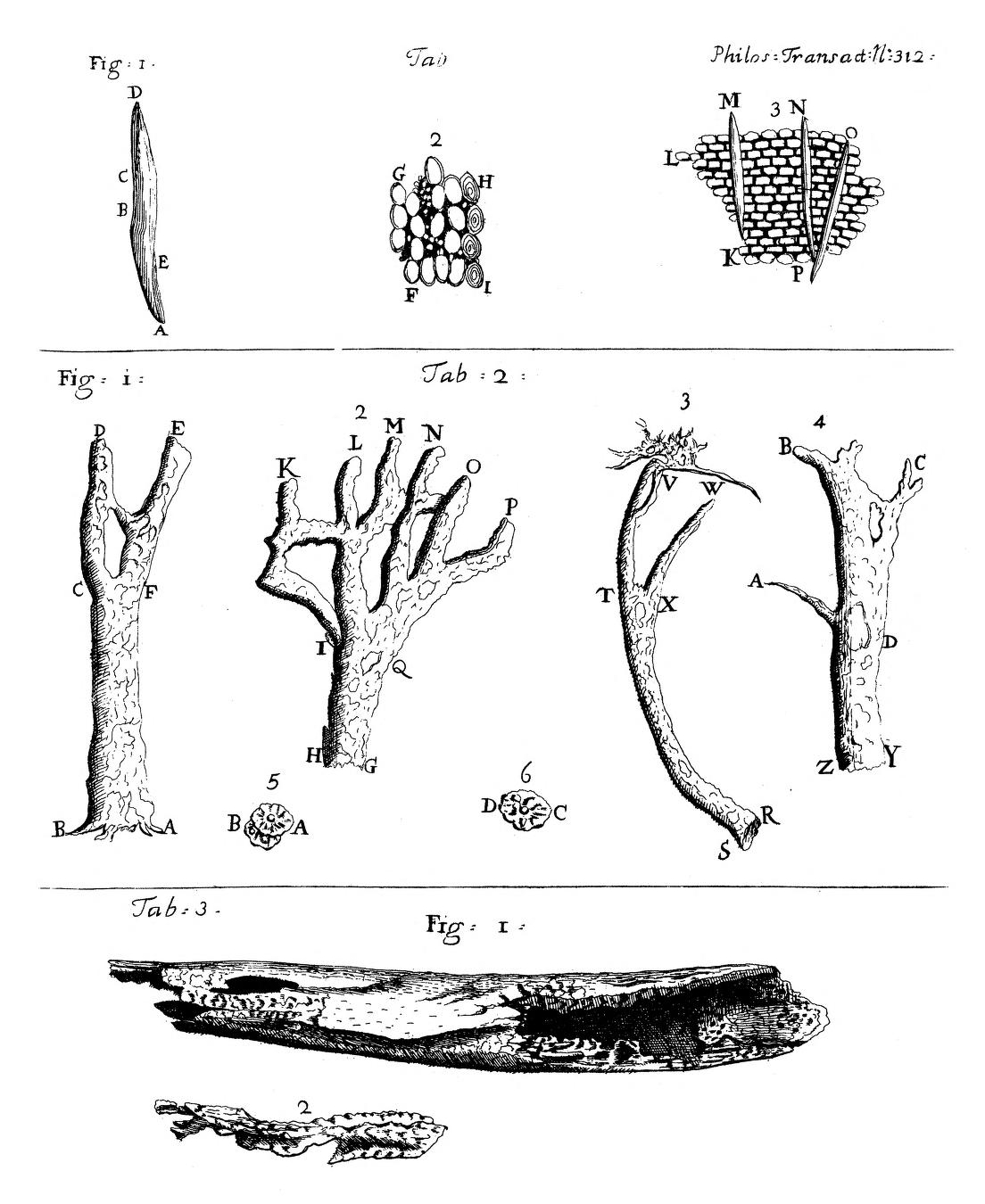

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by the astronomer

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by the astronomer

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in

The bark of trees in this genus is the source of a variety of

The bark of trees in this genus is the source of a variety of

Cinchona Bark.

University of Minnesota Libraries.

Botany Global Issues Map. McGraw Hill.

Cinchona Project Field Books, 1938-1965

from the

"The tree that changed the world map

" By Vittoria Traverso,28 May 2020, bbc.com. {{Authority control Rubiaceae genera Medicinal plants of South America Quinine Antimalarial agents Tropical flora Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae containing at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. All are native to the tropical Andean forests of western South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

. A few species are reportedly naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

in Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, French Polynesia

)Territorial motto: ( en, "Great Tahiti of the Golden Haze")

, anthem =

, song_type = Regional anthem

, song = "Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui"

, image_map = French Polynesia on the globe (French Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of French ...

, Sulawesi

Sulawesi (), also known as Celebes (), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the world's eleventh-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Mindanao and the Sulu ...

, Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constit ...

in the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe a ...

, and São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe (; pt, São Tomé e Príncipe (); English: " Saint Thomas and Prince"), officially the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe ( pt, República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe), is a Portuguese-speaking ...

off the coast of tropical Africa, and others have been cultivated in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, where they have formed hybrids.

''Cinchona'' has been historically sought after for its medicinal value, as the bark of several species yields quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

and other alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of simila ...

s. These were the only effective treatments against malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

during the height of European colonialism

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense began ...

, which made them of great economic and political importance. Trees in the genus are also known as fever trees because of their anti-malarial properties.

The artificial synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

* Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

**Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organ ...

of quinine in 1944, an increase in resistant forms of malaria, and the emergence of alternate therapies eventually ended large-scale economic interest in cinchona cultivation. Cinchona alkaloids show promise in treating ''falciparum'' malaria, which has evolved resistance to synthetic drugs. Cinchona plants continue to be revered for their historical legacy; the national tree of Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

is in the genus ''Cinchona''.

Etymology and common names

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

named the genus in 1742, based on a claim that the plant had cured the wife of the Count of Chinchón

Count of Chinchón ( es, Conde de Chinchón) is a title of Spanish nobility. It was initially created on 9 May 1520 by King Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (Charles I of Spain), who granted the title to Fernando de Cabrera y Bobadilla.

History

...

, a Spanish viceroy in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

, in the 1630s, though the veracity of this story has been disputed. Linnaeus used the Italian spelling ''Cinchona'', but the name Chinchón (pronounced in Spanish) led to Clements Markham and others proposing a correction of the spelling to ''Chinchona'', and some prefer the pronunciation for the common name of the plant. Traditional medicine

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) comprises medical aspects of traditional knowledge that developed over generations within the folk beliefs of various societies, including indigenous peoples, before the ...

uses from South America known as Jesuit's bark and Jesuit's powder have been traced to ''Cinchona''.

Description

''Cinchona'' plants belong to the family Rubiaceae and are largeshrub

A shrub (often also called a bush) is a small-to-medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from tree ...

s or small tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are ...

s with evergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant which has foliage that remains green and functional through more than one growing season. This also pertains to plants that retain their foliage only in warm climates, and contrasts with deciduous plants, whic ...

foliage, growing in height. The leaves are opposite, rounded to lanceolate, and 10–40 cm long. The flower

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Angiospermae). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechanis ...

s are white, pink, or red, and produced in terminal panicle

A panicle is a much-branched inflorescence. (softcover ). Some authors distinguish it from a compound spike inflorescence, by requiring that the flowers (and fruit) be pedicellate (having a single stem per flower). The branches of a panicle are of ...

s. The fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

is a small capsule containing numerous seed

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiosper ...

s. A key character of the genus is that the flowers have marginally hairy corolla lobes. The tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confl ...

Cinchoneae includes the genera ''Cinchonopsis'', ''Jossia'', ''Ladenbergia'', ''Remijia'', ''Stilpnophyllum'', and ''Ciliosemina''. In South America, natural populations of ''Cinchona'' species have geographically distinct distributions. During the 19th century, the introduction of several species into cultivation in the same areas of India and Java, by the English and Dutch East India Company, respectively, led to the formation of hybrids.

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

described the genus based on the species ''Cinchona officinalis'', which is found only in a small region of Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

and is of little medicinal significance. Nearly 300 species were later described and named in the genus, but a revision of the genus in 1998 identified only 23 distinct species.''Cinchona''.Selected Rubiaceae Tribes and Genera. Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden.

History

Early references

The febrifugal properties of bark from trees now known to be in the genus ''Cinchona'' were used by many South American cultures prior to European contact, butmalaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

is an Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

disease that was introduced into the Americas by Europeans only after 1492. The origins and claims to the use of febrifugal barks and powders in Europe, especially those used against malaria, were disputed even in the 17th century. Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

played a key role in the transfer of remedies from the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

.

The traditional story connecting cinchona with malaria treatment was first recorded by the Italian physician Sebastiano Bado in 1663. It tells of the wife of Luis Jerónimo de Cabrera, 4th Count of Chinchón

Luis Jerónimo Fernández de Cabrera Bobadilla Cerda y Mendoza, 4th Count of Chinchón, also known as Luis Xerónimo Fernandes de Cabrera Bobadilla y Mendoza, (1589 in Madrid – October 28, 1647 in Madrid) was a Spanish nobleman, Comendador ...

and Viceroy of Peru, who fell ill in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

with a tertian fever. A Spanish governor advised a traditional remedy, which resulted in a miraculous and rapid cure. The Countess then supposedly ordered a large quantity of the bark and took it back to Europe. Bado claimed to have received this information from an Italian named Antonius Bollus who was a merchant in Peru. Clements Markham identified the Countess as Ana de Osorio, but this was shown to be incorrect by Haggis. Ana de Osorio married the Count of Chinchón in August 1621 and died in 1625, several years before the Count was appointed Viceroy of Peru in 1628. It was his second wife, Francisca Henriques de Ribera, who accompanied him to Peru. Haggis further examined the Count's diaries and found no mention of the Countess suffering from fever, although the Count himself had many malarial attacks. Because of these and numerous other discrepancies, Bado's story has been generally rejected as little more than a legend.

Quina bark was mentioned by Fray Antonio de La Calancha in 1638 as coming from a tree in Loja (Loxa). He noted that bark powder weighing about two coins was cast into water and drunk to cure fevers and "tertians". Jesuit Father Bernabé Cobo (1582–1657) also wrote on the "fever tree" in 1653. The legend was popularized in English literature by Markham, and in 1874 he also published a "plea for the correct spelling of the genus ''Chinchona''". Spanish physician and botanist Nicolás Monardes wrote of a New World bark powder used in Spain in 1574, and another physician, Juan Fragoso, wrote of bark powder from an unknown tree in 1600 that was used for treating various ills. Both identify the sources as trees that do not bear fruit and have heart-shaped leaves; it has been suggested that they were referring to ''Cinchona'' species.

The name quina-quina or quinquina was suggested as an old name for cinchona used in Europe and based on the native name used by the Quechua people

Quechua people (, ; ) or Quichua people, may refer to any of the aboriginal people of South America who speak the Quechua languages, which originated among the Indigenous people of Peru. Although most Quechua speakers are native to Peru, the ...

. Italian sources spelt ''quina'' as "cina" which was a source of confusion with '' Smilax'' from China. Haggis argued that Qina and Jesuit's bark actually referred to ''Myroxylon peruiferum'', or Peruvian balsam, and that this was an item of importance in Spanish trade in the 1500s. Over time, the bark of ''Myroxylon'' may have been adulterated with the similar-looking bark of what we now know as ''Cinchona''. Gradually the adulterant became the main product that was the key therapeutic ingredient used in malarial therapy. The bark was included as ''Cortex Peruanus'' in the London Pharmacopoeia

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (from the obsolete typography ''pharmacopœia'', meaning "drug-making"), in its modern technical sense, is a book containing directions for the identification of compound medicines, and published by ...

in 1677.

Economic Significance

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by the astronomer

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by the astronomer Charles Marie de la Condamine

Charles Marie de La Condamine (28 January 1701 – 4 February 1774) was a French explorer, geographer, and mathematician. He spent ten years in territory which is now Ecuador, measuring the length of a degree of latitude at the equator and p ...

, who visited Quito in 1735 on a quest to measure an arc of the meridian

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve between two points on the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a segment of the meridian, or to its length.

The purpose of measuring meridian arcs is t ...

. The species he described, ''Cinchona officinalis'', was, however, found to be of little therapeutic value. The first living plants seen in Europe were ''C. calisaya'' plants grown at the ''Jardin des Plantes'' from seeds collected by Hugh Algernon Weddell from Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

in 1846. José Celestino Mutis, physician to the Viceroy of Nueva Granada, Pedro Messia de la Cerda, gathered information on cinchona in Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the ...

from 1760 and wrote a manuscript, ''El Arcano de la Quina'' (1793), with illustrations. He proposed a Spanish expedition to search for plants of commercial value, which was approved in 1783 and was continued after his death in 1808 by his nephew Sinforoso Mutis. As demand for the bark increased, the trees in the forests began to be destroyed. To maintain their monopoly on cinchona bark, Peru and surrounding countries began outlawing the export of cinchona seeds and saplings beginning in the early 19th century.

The colonial European powers eventually considered growing the plant in other parts of the tropics. The French mission of 1743, of which de la Condamine was a member, lost their cinchona plants when a wave took them off their ship. The Dutch sent Justus Hasskarl, who brought plants that were then cultivated in Java from 1854. The English explorer Clements Markham went to collect plants that were introduced in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and the Nilgiris of southern India in 1860. The main species introduced were ''Cinchona succirubra

''Cinchona pubescens'', also known as red cinchona and quina (Kina) ( ''Cascarilla, cinchona''; ''quina-do-amazonas, quineira''), is native to Central and South America. It is known as a medicinal plant for its bark's high quinine content- and ...

'', or red bark, (now ''C. pubescens'') as its sap turned red on contact with air, and '' Cinchona calisaya''. The alkaloids quinine and cinchonine were extracted by Pierre Joseph Pelletier

Pierre-Joseph Pelletier (, , ; 22 March 1788 – 19 July 1842) was a French chemist and pharmacist who did notable research on vegetable alkaloids, and was the co-discoverer with Joseph Bienaimé Caventou of quinine, caffeine, and strychnine. ...

and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou in 1820. Two more key alkaloids, quinidine and cinchonidine, were later identified and it became a routine in quinology to examine the contents of these components in assays. The yields of quinine in the cultivated trees were low and it took a while to develop sustainable methods to extract bark.

In the meantime, Charles Ledger and his native assistant Manuel collected another species from Bolivia. Manuel was caught and beaten by Bolivian officials, leading to his death, but Ledger obtained seeds of high quality. These seeds were offered to the British, who were uninterested, leading to the rest being sold to the Dutch. The Dutch saw their value and multiplied the stock. The species later named ''Cinchona ledgeriana'' yielded 8 to 13 percent quinine in bark grown in Dutch Indonesia, which effectively out-competed the British Indian production. It was only later that the English saw the value and sought to obtain the seeds of ''C. ledgeriana'' from the Dutch.

Francesco Torti used the response of fevers to treatment with cinchona as a system of classification of fevers or a means for diagnosis. The use of cinchona in the effective treatment of malaria brought an end to treatment by bloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) is the withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily f ...

and long-held ideas of humorism

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

from Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

. For his part in obtaining and helping the establishment of cinchona in British India, Clements Markham was knighted. For his role in establishing cinchona in Indonesia, Hasskarl was knighted with the Dutch order of the Lion.

Ecology

''Cinchona'' species are used as food plants by thelarva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

...

e of some Lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) is an order of insects that includes butterflies and moths (both are called lepidopterans). About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera are described, in 126 families and 46 superfamilies, 10 percent of the total described speci ...

species, including the engrailed, the commander, and members of the genus '' Endoclita'', including '' E. damor'', '' E. purpurescens'', and '' E. sericeus''.

''Cinchona pubescens'' has grown uncontrolled on some islands, such as the Galapagos, where it has posed the risk of out-competing native plant species.

Traditional medicine

It is unclear if cinchona bark was used in any traditional medicines within Andean Indigenous groups when it first came to notice by Europeans. Since its first confirmed medicinal record in the early seventeenth century, it has been used as a treatment for malaria. This use was popularised in Europe by the Spanish colonisers of South America. The bark containsalkaloids

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

, including quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

and quinidine. Cinchona is the only economically practical source of quinine, a drug that is still recommended for the treatment of ''falciparum'' malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

.

Europe

The Italian botanistPietro Castelli

Pietro Castelli (1574–1662) was an Italian physician and botanist.

Born at Rome, he was graduated in 1617 and studied under the botanist Andrea Cesalpino (1519–1603). He was professor at Rome from 1597 until 1634, when he went to Messina. H ...

wrote a pamphlet noteworthy as being the first Italian publication to mention the cinchona. By the 1630s (or 1640s, depending on the reference), the bark was being exported to Europe. In the late 1640s, the method of use of the bark was noted in the '' Schedula Romana.'' The Royal Society of London published in its first year (1666) "An account of Dr. Sydenham's book, entitled, Methodus curandi febres . . ."

English King Charles II called upon Robert Talbor, who had become famous for his miraculous malaria cure. Because at that time the bark was in religious controversy, Talbor gave the king the bitter bark decoction in great secrecy. The treatment gave the king complete relief from the malaria fever. In return, Talbor was offered membership of the prestigious Royal College of Physicians.

In 1679, Talbor was called by the King of France, Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

, whose son was suffering from malaria fever. After a successful treatment, Talbor was rewarded by the king with 3,000 gold crowns and a lifetime pension for this prescription. Talbor was asked to keep the entire episode secret. After Talbor's death, the French king published this formula: seven grams of rose leaves, two ounces of lemon juice and a strong decoction of the cinchona bark served with wine. Wine was used because some alkaloids of the cinchona bark are not soluble in water, but are soluble in the ethanol in wine. In 1681 '' Água de Inglaterra'' was introduced into Portugal from England by Dr. Fernando Mendes who, similarly, "received a handsome gift from ( King Pedro) on condition that he should reveal to him the secret of its composition and withhold it from the public".

In 1738, ''Sur l'arbre du quinquina'', a paper written by Charles Marie de La Condamine

Charles Marie de La Condamine (28 January 1701 – 4 February 1774) was a French explorer, geographer, and mathematician. He spent ten years in territory which is now Ecuador, measuring the length of a degree of latitude at the equator and p ...

, lead member of the expedition, along with Pierre Godin and Louis Bouger that was sent to Ecuador to determine the length of a degree of the 1/4 of meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve between two points on the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a segment of the meridian, or to its length.

The purpose of measuring meridian arcs is to ...

in the neighbourhood of the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can also ...

, was published by the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at ...

. In it he identified three separate species.

Homeopathy

The birth ofhomeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a d ...

was based on cinchona bark testing. The founder of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, when translating William Cullen

William Cullen FRS FRSE FRCPE FPSG (; 15 April 17105 February 1790) was a Scottish physician, chemist and agriculturalist, and professor at the Edinburgh Medical School. Cullen was a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment: He was ...

's '' Materia medica'', noticed Cullen had written that Peruvian bark was known to cure intermittent fevers. Hahnemann took daily a large, rather than homeopathic, dose of Peruvian bark. After two weeks, he said he felt malaria-like symptoms. This idea of "like cures like" was the starting point of his writings on homeopathy. Hahnemann's symptoms have been suggested by researchers, both homeopaths and skeptics, as being an indicator of his hypersensitivity to quinine.

Widespread cultivation

The bark was very valuable to Europeans in expanding their access to and exploitation of resources in distant colonies and at home. Bark gathering was often environmentally destructive, destroying huge expanses of trees for their bark, with difficult conditions for low wages that did not allow the indigenous bark gatherers to settle debts even upon death. Further exploration of theAmazon Basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Boli ...

and the economy of trade in various species of the bark in the 18th century is captured by Lardner Gibbon:

... this bark was first gathered in quantities in 1849, though known for many years. The best quality is not quite equal to that of Yungas, but only second to it. There are four other classes of inferior bark, for some of which the bank pays fifteen dollars per quintal. The best, by law, is worth fifty-four dollars. The freight to Arica is seventeen dollars the mule load of three quintals. Six thousand quintals of bark have already been gathered from Yuracares. The bank was established in the year 1851. Mr. haddäusHaenke mentioned the existence of cinchona bark on his visit to Yuracares in 1796 :— ''Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon'', by Lieut.It was estimated that the British Empire incurred direct losses of 52 to 62 million pounds a year due to malaria sickness each year. It was therefore of great importance to secure the supply of the cure. In 1860, a British expedition to South America led by Clements Markham smuggled back cinchona seeds and plants, which were introduced in several areas of British India and Sri Lanka. In India, it was planted in Ootacamund by William Graham McIvor. In Sri Lanka, it was planted in the Hakgala Botanical Garden in January 1861.Lardner Gibbon ''Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon'' is a two volume publication by two young USN lieutenants William Lewis Herndon (vol. 1) and Lardner A. Gibbon (vol. 2). Gibbon's dates: Aug. 13, 1820 - Jan. 10, 1910. Herndon split the main party in ..., USN. Vol. II, Ch. 6, pp. 146–47.

James Taylor

James Vernon Taylor (born March 12, 1948) is an American singer-songwriter and guitarist. A six-time Grammy Award winner, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000. He is one of the List of best-selling music artists, best-sell ...

, the pioneer of tea planting in Sri Lanka, was one of the pioneers of cinchona cultivation. By 1883, about were in cultivation in Sri Lanka, with exports reaching a peak of 15 million pounds in 1886. The cultivation (initially of ''Cinchona succirubra'' (now ''C. pubescens'') and later of ''C. calisaya'') was extended through the work of George King George King may refer to:

Politics

* George King (Australian politician) (1814–1894), New South Wales and Queensland politician

* George King, 3rd Earl of Kingston (1771–1839), Irish nobleman and MP for County Roscommon

* George Clift King (184 ...

and others into the hilly terrain of Darjeeling District

Darjeeling District is the northernmost district of the state of West Bengal in eastern India in the foothills of the Himalayas. The district is famous for its hill station and Darjeeling tea. Darjeeling is the district headquarters.

Ku ...

of Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

. Cinchona factories were established at Naduvattam in the Nilgiris and at Mungpoo

Mungpoo (also referred to as Mangpu Cinchona Plantation, or rendered Mungpoo) is a village in the Kurseong 24 Bidhan Sabha Constituency Rangli Rangliot (community development block) in the Kurseong subdivision of the Darjeeling district in the st ...

, Darjeeling, West Bengal. Quinologists were appointed to oversee the extraction of alkaloids with John Broughton in the Nilgiris and C.H. Wood at Darjeeling. Others in the position included David Hooper and John Eliot Howard.

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

by Matthew Fontaine Maury, a former Confederate in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. Postwar Confederates were enticed there by Maury, now the "Imperial Commissioner of Immigration" for Emperor Maximillian of Mexico, and Archduke of Habsburg. All that survives of those two colonies are the flourishing groves of ''cinchonas'' established by Maury using seeds purchased from England. These seeds were the first to be introduced into Mexico.

The cultivation of cinchona led from the 1890s to a decline in the price of quinine, but the quality and production of raw bark by the Dutch in Indonesia led them to dominate world markets. The producers of processed drugs in Europe (especially Germany), however, bargained and caused fluctuations in prices, which led to a Dutch-led Cinchona Agreement in 1913 that ensured a fixed price for producers. A ''Kina Bureau'' in Amsterdam regulated this trade.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the Japanese conquered Java and the United States lost access to the cinchona plantations that supplied war-critical quinine medication. Botanical expeditions called Cinchona Missions were launched between 1942 and 1944 to explore promising areas of South America in an effort to locate cinchona species that contained quinine and could be harvested for quinine production. As well as being ultimately successful in their primary aim, these expeditions also identified new species of plants and created a new chapter in international relations between the United States and other nations in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

.

Chemistry

Cinchona alkaloids

alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of simila ...

s, the most familiar of which is quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, an antipyretic (antifever) agent especially useful in treating malaria. For a while the extraction of a mixture of alkaloids from the cinchona bark, known in India as the cinchona febrifuge, was used. The alkaloid mixture or its sulphated form mixed in alcohol and sold quinetum was however very bitter and caused nausea, among other side effects.

Cinchona alkaloids include:

* cinchonine and cinchonidine ( stereoisomers with R1 = vinyl, R2 = hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

)

* quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

and quinidine ( stereoisomers with R1 = vinyl, R2 = methoxy)

* dihydroquinine

Dihydroquinine, also known as hydroquinine, is an organic compound and as a cinchona alkaloid closely related to quinine. The specific rotation is −148° in ethanol. A derivative of this molecule is used as chiral ligand in the AD-mix for Sh ...

and dihydroquinidine

Dihydroquinidine (also called hydroquinidine) is an organic compound, a cinchona alkaloid closely related to quinine. The specific rotation is +226° in ethanol at 2g/100 ml. A derivative of this molecule is used as chiral ligand in the AD-mix ...

(stereoisomers with R1 = ethyl, R2 = methoxy)

They find use in organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J ...

as organocatalysts in asymmetric synthesis

Enantioselective synthesis, also called asymmetric synthesis, is a form of chemical synthesis. It is defined by IUPAC as "a chemical reaction (or reaction sequence) in which one or more new elements of chirality are formed in a substrate molecu ...

.

Other chemicals

Alongside the alkaloids, many cinchona barks containcinchotannic acid

Cinchotannic acid is a tannin contained in many cinchona barks, which by oxidation rapidly yields a dark-coloured phlobaphen

Phlobaphenes (or phlobaphens, CAS No.:71663-19-9) are reddish, alcohol-soluble and water-insoluble phenolic substances. Th ...

, a particular tannin, which by oxidation rapidly yields a dark-coloured phlobaphene called red cinchonic, cinchono-fulvic acid, or cinchona red.

In 1934, efforts to make malaria drugs cheap and effective for use across countries led to the development of a standard called "totaquina" proposed by the Malaria Commission of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

. Totaquina required a minimum of 70% crystallizable alkaloids, of which at least 15% was to be quinine with not more than 20% amorphous alkaloids.

Species

There are at least 24 species of ''Cinchona'' recognized by botanists. There are likely several unnamed species and many intermediate forms that have arisen due to the plants' tendency to hybridize. * '' Cinchona anderssonii'' Maldonado * '' Cinchona antioquiae'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona asperifolia'' Wedd. * '' Cinchona barbacoensis'' H.Karst. * '' Cinchona calisaya'' Wedd. * '' Cinchona capuli'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona fruticosa'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona glandulifera'' Ruiz & Pav. * '' Cinchona hirsuta'' Ruiz & Pav. * '' Cinchona krauseana'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona lancifolia'' Mutis * '' Cinchona lucumifolia'' Pav. ex Lindl. * '' Cinchona macrocalyx'' Pav. ex DC. * '' Cinchona micrantha'' Ruiz & Pav. * '' Cinchona mutisii'' Lamb. * '' Cinchona nitida'' Ruiz & Pav. * '' Cinchona officinalis'' L. * '' Cinchona parabolica'' Pav. in J.E.Howard * '' Cinchona pitayensis'' (Wedd.) Wedd. * ''Cinchona pubescens

''Cinchona pubescens'', also known as red cinchona and quina (Kina) ( ''Cascarilla, cinchona''; ''quina-do-amazonas, quineira''), is native to Central and South America. It is known as a medicinal plant for its bark's high quinine content- and ...

'' Vahl

* '' Cinchona pyrifolia'' L.Andersson

* '' Cinchona rugosa'' Pav. in J.E.Howard

* '' Cinchona scrobiculata'' Humb. & Bonpl.

* '' Cinchona villosa'' Pav. ex Lindl.

See also

*History of malaria

The history of malaria extendes from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent e ...

* Cinchonism

Cinchonism is a pathological condition caused by an overdose of quinine or its natural source, cinchona bark. Quinine and its derivatives are used medically to treat malaria and lupus erythematosus. In much smaller amounts, quinine is an ingredie ...

Notes

References

* * * * *External links

* Burba, JCinchona Bark.

University of Minnesota Libraries.

Botany Global Issues Map. McGraw Hill.

Cinchona Project Field Books, 1938-1965

from the

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an institutional archives and library system comprising 21 branch libraries serving the various Smithsonian Institution museums and research centers. The Libraries and Archives serve Smithsonian Instituti ...

Articles

"The tree that changed the world map

" By Vittoria Traverso,28 May 2020, bbc.com. {{Authority control Rubiaceae genera Medicinal plants of South America Quinine Antimalarial agents Tropical flora Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus