Chemosynthetic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or

In 1890,

In 1890,

Chemosynthetic Communities in the Gulf of Mexico

{{modelling ecosystems Biological processes Metabolism Environmental microbiology Ecosystems

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on ...

) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxi ...

gas, hydrogen sulfide) or ferrous

In chemistry, the adjective Ferrous indicates a compound that contains iron(II), meaning iron in its +2 oxidation state, possibly as the divalent cation Fe2+. It is opposed to "ferric" or iron(III), meaning iron in its +3 oxidation state, such a ...

ions as a source of energy, rather than sunlight, as in photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

. Chemoautotrophs, organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells ( cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and fung ...

s that obtain carbon from carbon dioxide through chemosynthesis, are phylogenetically diverse. Groups that include conspicuous or biogeochemically-important taxa include the sulfur-oxidizing Gammaproteobacteria

Gammaproteobacteria is a class of bacteria in the phylum Pseudomonadota (synonym Proteobacteria). It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genera-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scientifically im ...

, the Campylobacterota

Campylobacterota are a phylum of bacteria. All species of this phylum are Gram-negative.

The Campylobacterota consist of few known genera, mainly the curved to spirilloid ''Wolinella'' spp., ''Helicobacter'' spp., and '' Campylobacter'' spp. Mos ...

, the Aquificota, the methanogen

Methanogens are microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct in hypoxic conditions. They are prokaryotic and belong to the domain Archaea. All known methanogens are members of the archaeal phylum Euryarchaeota. Methanogens are c ...

ic archaea, and the neutrophilic iron-oxidizing bacteria.

Many microorganisms in dark regions of the oceans use chemosynthesis to produce biomass from single-carbon molecules. Two categories can be distinguished. In the rare sites where hydrogen molecules (H2) are available, the energy available from the reaction between CO2 and H2 (leading to production of methane, CH4) can be large enough to drive the production of biomass. Alternatively, in most oceanic environments, energy for chemosynthesis derives from reactions in which substances such as hydrogen sulfide or ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

are oxidized. This may occur with or without the presence of oxygen.

Many chemosynthetic microorganisms are consumed by other organisms in the ocean, and symbiotic

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasi ...

associations between chemosynthesizers and respiring heterotrophs are quite common. Large populations of animals can be supported by chemosynthetic secondary production

In ecology, the term productivity refers to the rate of generation of biomass in an ecosystem, usually expressed in units of mass per volume (unit surface) per unit of time, such as grams per square metre per day (g m−2 d−1). The unit of mas ...

at hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

s, methane clathrate

Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) or (8CH4·46H2O), also called methane hydrate, hydromethane, methane ice, fire ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate, is a solid clathrate compound (more specifically, a clathrate hydrate) in which a large amou ...

s, cold seeps, whale fall

A whale fall occurs when the carcass of a whale has fallen onto the ocean floor at a depth greater than , in the bathyal or abyssal zones. On the sea floor, these carcasses can create complex localized ecosystems that supply sustenance to de ...

s, and isolated cave water.

It has been hypothesized that anaerobic chemosynthesis may support life below the surface of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin atmosp ...

, Jupiter's moon Europa, and other planets. Chemosynthesis may have also been the first type of metabolism that evolved on Earth, leading the way for cellular respiration and photosynthesis to develop later.

Hydrogen sulfide chemosynthesis process

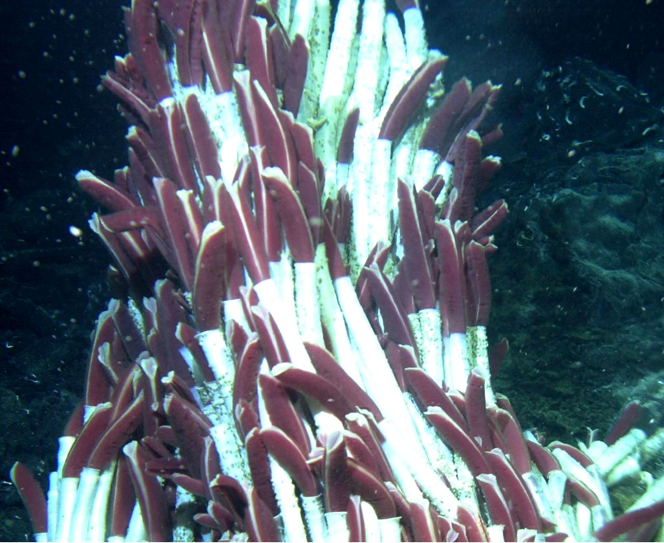

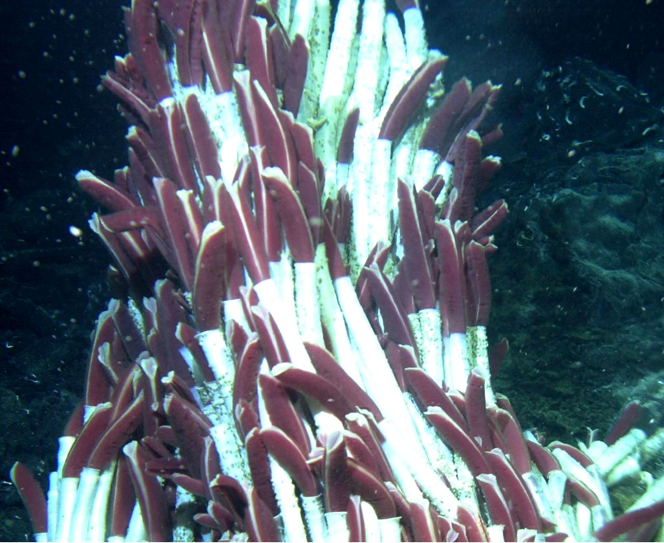

Giant tube worm

''Riftia pachyptila'', commonly known as the giant tube worm and less commonly known as the Giant beardworm, is a marine invertebrate in the phylum Annelida (formerly grouped in phylum Pogonophora and Vestimentifera) related to tube worms ...

s use bacteria in their trophosome A trophosome is a highly vascularised organ found in some animals that houses symbiotic bacteria that provide food for their host. Trophosomes are located in the coelomic cavity in the vestimentiferan tube worms ( Siboglinidae, e.g. the giant tube ...

to fix carbon dioxide (using hydrogen sulfide as their energy source) and produce sugars and amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s.

Some reactions produce sulfur:

:hydrogen sulfide chemosynthesis:

::18H2S + 6CO2 + 3O2 → C6H12O6 ( carbohydrate) + 12H2O + 18S

Instead of releasing oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as well ...

gas while fixing carbon dioxide as in photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

, hydrogen sulfide chemosynthesis produces solid globules of sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

in the process. In bacteria capable of chemoautotrophy (a form a chemosynthesis), such as purple sulfur bacteria

The purple sulfur bacteria (PSB) are part of a group of Pseudomonadota capable of photosynthesis, collectively referred to as purple bacteria. They are anaerobic or microaerophilic, and are often found in stratified water environments including h ...

, yellow globules of sulfur are present and visible in the cytoplasm.

Discovery

In 1890,

In 1890, Sergei Winogradsky

Sergei Nikolaievich Winogradsky (or Vinohradsky; published under the name of Sergius Winogradsky or M. S. Winogradsky from Ukrainian Mykolayovych Serhiy; uk, Сергій Миколайович Виноградський; 1 September 1856 – ...

proposed a novel type of life process called "anorgoxydant". His discovery suggested that some microbes could live solely on inorganic matter and emerged during his physiological research in the 1880s in Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label= Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

and Zürich

Zürich () is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 43 ...

on sulfur, iron, and nitrogen bacteria.

In 1897, Wilhelm Pfeffer

Wilhelm Friedrich Philipp Pfeffer (9 March 1845 – 31 January 1920) was a German botanist and plant physiologist born in Grebenstein.

Academic career

He studied chemistry and pharmacy at the University of Göttingen, where his instructors inc ...

coined the term "chemosynthesis" for the energy production by oxidation of inorganic substances, in association with autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation—what would be named today as chemolithoautotrophy. Later, the term would be expanded to include also chemoorganoautotrophs, which are organisms that use organic energy substrates in order to assimilate carbon dioxide. Thus, chemosynthesis can be seen as a synonym of chemoautotrophy

A Chemotroph is an organism that obtains energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic (chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic ( chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph designation is in contrast to pho ...

.

The term " chemotrophy", less restrictive, would be introduced in the 1940s by André Lwoff

André — sometimes transliterated as Andre — is the French and Portuguese form of the name Andrew, and is now also used in the English-speaking world. It used in France, Quebec, Canada and other French-speaking countries. It is a variation ...

for the production of energy by the oxidation of electron donors, organic or not, associated with auto- or heterotrophy.

Hydrothermal vents

The suggestion of Winogradsky was confirmed nearly 90 years later, when hydrothermalocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wor ...

vents were predicted to exist in the 1970s. The hot springs and strange creatures were discovered by '' Alvin'', the world's first deep-sea submersible, in 1977 at the Galapagos Rift. At about the same time, then-graduate student Colleen Cavanaugh proposed chemosynthetic bacteria that oxidize sulfides or elemental sulfur as a mechanism by which tube worms could survive near hydrothermal vents. Cavanaugh later managed to confirm that this was indeed the method by which the worms could thrive, and is generally credited with the discovery of chemosynthesis.

A 2004 television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, e ...

series hosted by Bill Nye named chemosynthesis as one of the 100 greatest scientific discoveries of all time.

Oceanic crust

In 2013, researchers reported their discovery of bacteria living in the rock of theoceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic c ...

below the thick layers of sediment, and apart from the hydrothermal vents that form along the edges of the tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

s. Preliminary findings are that these bacteria subsist on the hydrogen produced by chemical reduction of olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers quickl ...

by seawater circulating in the small veins that permeate the basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% of a ...

that comprises oceanic crust. The bacteria synthesize methane by combining hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

Chemosynthesis as an innovation for researches

Despite the fact that the process of chemosynthesis has been known for more than a hundred years, its significance and importance are still relevant today in the transformation of chemical elements in biogeochemical cycles. Today, the vital processes of nitrifying bacteria, which lead to the oxidation of ammonia to nitric acid, require scientific substantiation and additional research. The ability of bacteria to convert inorganic substances into organic ones suggests that chemosynthetics can accumulate valuable resources for human needs. Chemosynthetic communities in different environments are important biological systems in terms of their ecology, evolution and biogeography, as well as their potential as indicators of the availability of permanent hydrocarbon- based energy sources. In the process of chemosynthesis, bacteria produce organic matter where photosynthesis is impossible. Isolation of thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria ''Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii'' and other types of chemosynthetics provides prospects for further research. Thus, the importance of chemosynthesis remains relevant for use in innovative technologies, conservation of ecosystems, human life in general. The role of Sergey Winogradsky in discovering the phenomenon of chemosynthesis is underestimated and needs further research and popularization.See also

*Primary nutritional groups

Primary nutritional groups are groups of organisms, divided in relation to the nutrition mode according to the sources of energy and carbon, needed for living, growth and reproduction. The sources of energy can be light or chemical compounds; the ...

* Autotroph

* Heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

* Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

* Movile Cave

Movile Cave () is a cave near Mangalia, Constanța County, Romania discovered in 1986 by Cristian Lascu a few kilometers from the Black Sea coast. It is notable for its unique groundwater ecosystem abundant in hydrogen sulfide and carbon diox ...

References

External links

Chemosynthetic Communities in the Gulf of Mexico

{{modelling ecosystems Biological processes Metabolism Environmental microbiology Ecosystems