Ancient Macedonians on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Axios in the northeastern part of mainland Greece. Essentially an ancient Greek people,; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; . they gradually expanded from their homeland along the Haliacmon valley on the northern edge of the Greek world, absorbing or driving out neighbouring non-Greek tribes, primarily Thracian and Illyrian.. They spoke Ancient Macedonian, which was perhaps a sibling

The expansion of the Macedonian kingdom has been described as a three-stage process. As a frontier kingdom on the border of the Greek world with barbarian Europe, the Macedonians first subjugated their immediate northern neighboursvarious Illyrian and Thracian tribesbefore turning against the states of

The expansion of the Macedonian kingdom has been described as a three-stage process. As a frontier kingdom on the border of the Greek world with barbarian Europe, the Macedonians first subjugated their immediate northern neighboursvarious Illyrian and Thracian tribesbefore turning against the states of

The earliest sources, Herodotus and Thucydides, called the royal family "Temenidae". In later sources (Strabo, Appian, Pausanias) the term "Argeadae" was introduced. However,

The earliest sources, Herodotus and Thucydides, called the royal family "Temenidae". In later sources (Strabo, Appian, Pausanias) the term "Argeadae" was introduced. However,

2.155–1754.8

''Odyssey''

8.5784.6

The most common connection to the royal family, as written by Herodotus, is with Peloponnesian Argos. Appian connects it with Orestian Argos. According to another tradition mentioned by Justin, the name was adopted after Caranus moved Macedonia's capital from Edessa to Aegae, thus appropriating the name of the city for its citizens. A figure, Argeas, is mentioned in the ''Iliad'' (16.417).

Taking Herodotus's lineage account as the most trustworthy, Appian said that after Perdiccas, six successive heirs ruled: Argeus, Philip, Aeropus, Alcetas, Amyntas and Alexander.

Thucydides's account gives a geographical overview of Macedonian possessions at the time of Alexander I's rule. To reconstruct a chronology of the expansion by Alexander I's predecessors is more difficult, but generally, three stages have been proposed from Thucydides' reading. The initial and most important conquest was of Pieria and Bottiaea, including the locations of Pydna and

Thucydides's account gives a geographical overview of Macedonian possessions at the time of Alexander I's rule. To reconstruct a chronology of the expansion by Alexander I's predecessors is more difficult, but generally, three stages have been proposed from Thucydides' reading. The initial and most important conquest was of Pieria and Bottiaea, including the locations of Pydna and

Present-day scholars have highlighted several inconsistencies in the traditionalist perspective first set in place by Hammond. An alternative model of state and ethnos formation, promulgated by an alliance of regional elites, which redates the creation of the Macedonian kingdom to the 6th century BC, was proposed in 2010.. According to these scholars, direct literary, archaeological, and linguistic evidence to support Hammond's contention that a distinct Macedonian ''ethnos'' had existed in the Haliacmon valley since the

Present-day scholars have highlighted several inconsistencies in the traditionalist perspective first set in place by Hammond. An alternative model of state and ethnos formation, promulgated by an alliance of regional elites, which redates the creation of the Macedonian kingdom to the 6th century BC, was proposed in 2010.. According to these scholars, direct literary, archaeological, and linguistic evidence to support Hammond's contention that a distinct Macedonian ''ethnos'' had existed in the Haliacmon valley since the  The process of state formation in Macedonia was similar to that of its neighbours in Epirus, Illyria,

The process of state formation in Macedonia was similar to that of its neighbours in Epirus, Illyria,

Macedonia had a distinct material culture by the Early Iron Age.. Typically Balkan burial, ornamental, and ceramic forms were used for most of the Iron Age. These features suggest broad cultural affinities and organizational structures analogous with Thracian, Epirote, and Illyrian regions.. This did not necessarily symbolize a shared cultural identity, or any political allegiance between these regions. In the late sixth century BC, Macedonia became open to south Greek influences, although a small but detectable amount of interaction with the south had been present since late Mycenaean times. By the 5th century BC, Macedonia was a part of the "Greek cultural milieu" according to Edward M. Anson, possessing many cultural traits typical of the southern Greek city-states.. Classical Greek objects and customs were appropriated selectively and used in peculiarly Macedonian ways.. In addition, influences from Achaemenid Persia in culture and economy are evident from the 5th century BC onward, such as the inclusion of Persian grave goods at Macedonian burial sites as well as the adoption of royal customs such as a Persian-style

Macedonia had a distinct material culture by the Early Iron Age.. Typically Balkan burial, ornamental, and ceramic forms were used for most of the Iron Age. These features suggest broad cultural affinities and organizational structures analogous with Thracian, Epirote, and Illyrian regions.. This did not necessarily symbolize a shared cultural identity, or any political allegiance between these regions. In the late sixth century BC, Macedonia became open to south Greek influences, although a small but detectable amount of interaction with the south had been present since late Mycenaean times. By the 5th century BC, Macedonia was a part of the "Greek cultural milieu" according to Edward M. Anson, possessing many cultural traits typical of the southern Greek city-states.. Classical Greek objects and customs were appropriated selectively and used in peculiarly Macedonian ways.. In addition, influences from Achaemenid Persia in culture and economy are evident from the 5th century BC onward, such as the inclusion of Persian grave goods at Macedonian burial sites as well as the adoption of royal customs such as a Persian-style

Macedonian society was dominated by aristocratic families whose main source of wealth and prestige was their herds of horses and cattle. In this respect, Macedonia was similar to Thessaly and Thrace. These aristocrats were second only to the king in terms of power and privilege, filling the ranks of his administration and serving as commanding officers in the military. It was in the more bureaucratic regimes of the

Macedonian society was dominated by aristocratic families whose main source of wealth and prestige was their herds of horses and cattle. In this respect, Macedonia was similar to Thessaly and Thrace. These aristocrats were second only to the king in terms of power and privilege, filling the ranks of his administration and serving as commanding officers in the military. It was in the more bureaucratic regimes of the

By the 5th century BC the Macedonians and the rest of the Greeks worshiped more or less the same deities of the Greek pantheon. In Macedonia, politics and religion often intertwined. For instance, the head of state for the city of Amphipolis also served as the priest of Asklepios, Greek god of medicine; a similar arrangement existed at Cassandreia, where a cult priest honoring the city's founder Cassander was the nominal municipal leader. Foreign cults from Egypt were fostered by the royal court, such as the temple of

By the 5th century BC the Macedonians and the rest of the Greeks worshiped more or less the same deities of the Greek pantheon. In Macedonia, politics and religion often intertwined. For instance, the head of state for the city of Amphipolis also served as the priest of Asklepios, Greek god of medicine; a similar arrangement existed at Cassandreia, where a cult priest honoring the city's founder Cassander was the nominal municipal leader. Foreign cults from Egypt were fostered by the royal court, such as the temple of  A notable feature of Macedonian culture was the ostentatious burials reserved for its rulers.. The Macedonian elite built lavish tombs at the time of death rather than constructing temples during life. Such traditions had been practiced throughout Greece and the central-west Balkans since the

A notable feature of Macedonian culture was the ostentatious burials reserved for its rulers.. The Macedonian elite built lavish tombs at the time of death rather than constructing temples during life. Such traditions had been practiced throughout Greece and the central-west Balkans since the

Aside from metalwork and painting,

Aside from metalwork and painting,

Perdiccas II of Macedon was able to host well-known Classical Greek intellectual visitors at his royal court, such as the lyric poet

Perdiccas II of Macedon was able to host well-known Classical Greek intellectual visitors at his royal court, such as the lyric poet

When Alexander I of Macedon petitioned to compete in the foot race of the ancient Olympic Games, the event organizers at first denied his request, explaining that only Greeks were allowed to compete. However, Alexander I produced proof of an Argead royal

When Alexander I of Macedon petitioned to compete in the foot race of the ancient Olympic Games, the event organizers at first denied his request, explaining that only Greeks were allowed to compete. However, Alexander I produced proof of an Argead royal

language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

to Ancient Greek, but more commonly thought to have been a dialect of Northwest Doric Greek; though, some have also suggested an Aeolic Greek classification. However, the prestige language of the region during the Classical era was Attic Greek, replaced by Koine Greek

Koine Greek (; Koine el, ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinè diálektos, the common dialect; ), also known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-reg ...

during the Hellenistic era. Their religious beliefs mirrored those of other Greeks, following the main deities of the Greek pantheon, although the Macedonians continued Archaic burial practices that had ceased in other parts of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

after the 6th century BC. Aside from the monarchy, the core of Macedonian society was its nobility. Similar to the aristocracy of neighboring Thessaly, their wealth was largely built on herding horses and cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

.

Although composed of various clans, the kingdom of Macedonia

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

, established around the 8th century BC, is mostly associated with the Argead dynasty and the tribe named after it. The dynasty was allegedly founded by Perdiccas I, descendant of the legendary Temenus of Argos, while the region of Macedon perhaps derived its name from Makedon, a figure of Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

. Traditionally ruled by independent families, the Macedonians seem to have accepted Argead rule by the time of Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of A ...

(). Under Philip II (), the Macedonians are credited with numerous military innovations, which enlarged their territory and increased their control over other areas extending into Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

. This consolidation of territory allowed for the exploits of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

(), the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire, the establishment of the diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

successor states, and the inauguration of the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

in West Asia, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, and the broader Mediterranean world. The Macedonians were eventually conquered by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

, which dismantled the Macedonian monarchy at the end of the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) and established the Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

of Macedonia after the Fourth Macedonian War

The Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by the pretender Andriscus, and the Roman Republic. It was the last of the Macedonian Wars, and was the last war to seriously threaten Roman control of Greece until the ...

(150–148 BC).

Authors, historians, and statesmen of the ancient world often expressed ambiguous if not conflicting ideas about the ethnic identity of the Macedonians as either Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

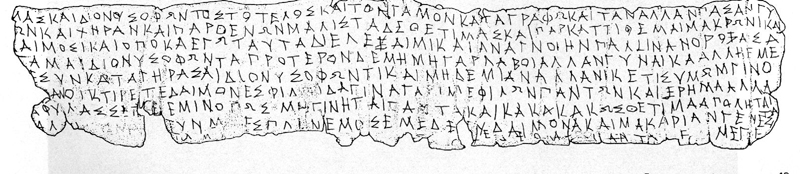

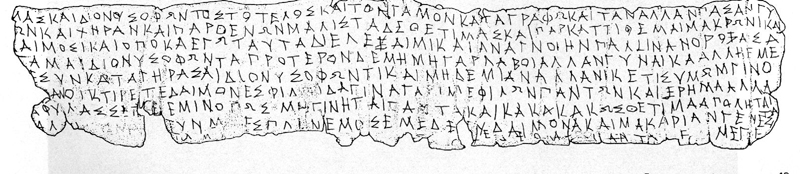

, semi-Greeks, or even barbarians. This has led to debate among modern academics about the precise ethnic identity of the Macedonians, who nevertheless embraced many aspects of contemporaneous Greek culture such as participation in Greek religious cults and athletic games, including the Ancient Olympic Games. Given the scant linguistic evidence, such as the Pella curse tablet, ancient Macedonian is regarded by most scholars as another Greek dialect, possibly related to Doric Greek or Northwestern Greek.

The ancient Macedonians participated in the production and fostering of Classical and later Hellenistic art. In terms of visual arts, they produced frescoes, mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

s, sculptures

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, and decorative metalwork. The performing arts of music and Greek theatrical dramas were highly appreciated, while famous playwrights such as Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

came to live in Macedonia. The kingdom also attracted the presence of renowned philosophers, such as Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, while native Macedonians contributed to the field of ancient Greek literature

Ancient Greek literature is literature written in the Ancient Greek language from the earliest texts until the time of the Byzantine Empire. The earliest surviving works of ancient Greek literature, dating back to the early Archaic Greece, Archa ...

, especially Greek historiography. Their sport and leisure activities included hunting, foot races, and chariot races, as well as feasting and drinking at aristocratic banquets known as '' symposia''.

Etymology

The ethnonym Μακεδόνες (''Makedónes'') stems from theAncient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

adjective μακεδνός (''makednós''), meaning "tall, slim", also the name of a people related to the Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ioni ...

(Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

). It is most likely cognate with the adjective μακρός (''makrós''), meaning "long" or "tall" in Ancient Greek. The name is believed to have originally meant either "highlanders", "the tall ones", or "high grown men".; ; Eugene N. Borza writes that the "highlanders" or "Makedones" of the mountainous regions of western Macedonia are derived from northwest Greek stock; they were akin to those who at an earlier time may have migrated south to become the historical "Dorians".

Origins, consolidation, and expansion

Historical overview

The expansion of the Macedonian kingdom has been described as a three-stage process. As a frontier kingdom on the border of the Greek world with barbarian Europe, the Macedonians first subjugated their immediate northern neighboursvarious Illyrian and Thracian tribesbefore turning against the states of

The expansion of the Macedonian kingdom has been described as a three-stage process. As a frontier kingdom on the border of the Greek world with barbarian Europe, the Macedonians first subjugated their immediate northern neighboursvarious Illyrian and Thracian tribesbefore turning against the states of southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

and central Greece

Continental Greece ( el, Στερεά Ελλάδα, Stereá Elláda; formerly , ''Chérsos Ellás''), colloquially known as Roúmeli (Ρούμελη), is a traditional geographic region of Greece. In English, the area is usually called Central ...

. Macedonia then led a pan-Hellenic military force against their primary objectivethe conquest of Persiawhich they achieved with remarkable ease. Following the death of Alexander the Great and the Partition of Babylon in 323 BC, the ''diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

'' successor states such as the Attalid, Ptolemaic and Seleucid Empires were established, ushering in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, West Asia and the Hellenized Mediterranean Basin. With Alexander's conquest of the Achaemenid Empire, Macedonians colonized territories as far east as Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

.

The Macedonians continued to rule much of Hellenistic Greece (323–146 BC), forming alliances with Greek leagues such as the Cretan League and Epirote League (and prior to this, the Kingdom of Epirus). However, they often fell into conflict with the Achaean League

The Achaean League ( Greek: , ''Koinon ton Akhaion'' "League of Achaeans") was a Hellenistic-era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea in the northwestern P ...

, Aetolian League, the city-state of Sparta, and the Ptolemaic dynasty of Hellenistic Egypt that intervened in wars of the Aegean region and mainland Greece. After Macedonia formed an alliance with Hannibal of Ancient Carthage

Carthage () was a settlement in modern Tunisia that later became a city-state and then an empire. Founded by the Phoenicians in the ninth century BC, Carthage reached its height in the fourth century BC as one of the largest metropolises in ...

in 215 BC, the rival Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

responded by fighting a series of wars against Macedonia in conjunction with its Greek allies such as Pergamon and Rhodes. In the aftermath of the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC), the Romans abolished the Macedonian monarchy under Perseus of Macedon () and replaced the kingdom with four client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

republics. A brief revival of the monarchy by the pretender Andriscus led to the Fourth Macedonian War

The Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by the pretender Andriscus, and the Roman Republic. It was the last of the Macedonian Wars, and was the last war to seriously threaten Roman control of Greece until the ...

(150–148 BC), after which Rome established the Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

of Macedonia and subjugated the Macedonians.

Prehistoric homeland

InGreek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

, Makedon is the eponymous hero of Macedonia and is mentioned in Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

's '' Catalogue of Women''. The first historical attestation of the Macedonians occurs in the works of Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

during the mid-5th century BC. The Macedonians are absent in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's '' Catalogue of Ships'' and the term "Macedonia" itself appears late. The ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

'' states that upon leaving Mount Olympus, Hera journeyed via Pieria and Emathia before reaching Athos. This is re-iterated by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...

in his ''Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

''. Nevertheless, archaeological evidence indicates that Mycenaean contact with or penetration into the Macedonian interior possibly started from the early 14th century BC.

In his ''A History of Macedonia'', Nicholas Hammond

Nicholas Hammond (born May 15, 1950) is an American-born Australian actor and writer who is best known for his roles as Friedrich von Trapp in the film ''The Sound of Music'' and as Peter Parker/Spider-Man in the 1970s television series '' The A ...

reconstructed the earliest phases of Macedonian history based on his interpretation of later literary accounts and archaeological excavations in the region of Macedonia. According to Hammond, the Macedonians are missing from early Macedonian historical accounts because they had been living in the Orestian highlands since before the Greek Dark Ages, possibly having originated from the same (proto-Greek) population pool that produced other Greek peoples. The Macedonian tribes subsequently moved down from Orestis in the upper Haliacmon to the Pierian highlands in the lower Haliacmon because of pressure from the Molossians, a related tribe who had migrated to Orestis from Pelagonia. In their new Pierian home north of Olympus, the Macedonian tribes mingled with the proto-Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ioni ...

. This might account for traditions which placed the eponymous founder, Makedon, near Pieria and Olympus.Hesiod. ''Catalogue of Women'', Fragment 7. Some traditions placed the Dorian homeland in the Pindus

The Pindus (also Pindos or Pindhos; el, Πίνδος, Píndos; sq, Pindet; rup, Pindu) is a mountain range located in Northern Greece and Southern Albania. It is roughly 160 km (100 miles) long, with a maximum elevation of 2,637 metres ...

mountain range in western Thessaly, whilst Herodotus pushed this further north to the Macedonian Pindus and claimed that the Greeks were referred to as ''Makednon'' (''Mακεδνόν'') and then as Dorians. A different, southern homeland theory also exists in traditional historiography. Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee (; 14 April 1889 – 22 October 1975) was an English historian, a philosopher of history, an author of numerous books and a research professor of international history at the London School of Economics and King's Colleg ...

asserted that the Makedones migrated north to Macedonia from central Greece

Continental Greece ( el, Στερεά Ελλάδα, Stereá Elláda; formerly , ''Chérsos Ellás''), colloquially known as Roúmeli (Ρούμελη), is a traditional geographic region of Greece. In English, the area is usually called Central ...

, placing the Dorian homeland in Phthiotis

Phthiotis ( el, Φθιώτιδα, ''Fthiótida'', ; ancient Greek and Katharevousa: Φθιῶτις) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. The capital is the city of Lamia. It is b ...

and citing the traditions of fraternity between Makedon and Magnes.

Temenids and Argeads

The Macedonian expansion is said to have been led by the ruling Temenid dynasty, known as " Argeads" or "Argives". Herodotus said thatPerdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, Περδίκκας, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to becom ...

, the dynasty's founder, was descended from the Heraclid Temenus. He left Argos with his two older brothers Aeropus and Gayanes, and travelled via Illyria to Lebaea Lebaea or Lebaie ( grc, Λεβαίη) was an ancient city in Upper Macedonia, and the residence of the early Macedonian kings, mentioned by Herodotus. The historian points out that, according to tradition, three brothers Gauanes, Aeropus and Perd ...

, a city in Upper Macedonia which certain scholars have tried to connect with the villages Alebea or Velvedos.. Here, the brothers served as shepherds for a local ruler. After a vision, the brothers fled to another region in Macedonia near the Midas Gardens by the foot of the Vermio Mountains, and then set about subjugating the rest of Macedonia.. Thucydides's account is similar to that of Herodotus, making it probable that the story was disseminated by the Macedonian court, i.e. it accounts for the belief the Macedonians had about the origin of their kingdom, if not an actual memory of this beginning.. Later historians modified the dynastic traditions by introducing variously Caranus or Archelaus, the son of Temenus, as the founding Temenid kingsalthough there is no doubt that Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

transformed ''Caranus'' to ''Archelaus'' meaning "leader of the people" in his play Archelaus, in an attempt to please Archelaus I of Macedon.

The earliest sources, Herodotus and Thucydides, called the royal family "Temenidae". In later sources (Strabo, Appian, Pausanias) the term "Argeadae" was introduced. However,

The earliest sources, Herodotus and Thucydides, called the royal family "Temenidae". In later sources (Strabo, Appian, Pausanias) the term "Argeadae" was introduced. However, Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς ''Appianòs Alexandreús''; la, Appianus Alexandrinus; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who flourished during the reigns of Emperors of Rome Trajan, Ha ...

said that the term Argeadae referred to a leading Macedonian tribe rather than the name of the ruling dynasty.Appian. ''Roman History'', 11.63.333.. The connection of the Argead name to the royal family is uncertain. The words "Argead" and "Argive" derive via Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

''Argīvus'' from grc, Ἀργεῖος (''Argeios''), meaning "of or from Argos", and is first attested in Homer, where it was also used as a collective designation for the Greeks ("Ἀργείων Δαναῶν", ''Argive Danaans

The Achaeans (; grc, Ἀχαιοί ''Akhaioí,'' "the Achaeans" or "of Achaea") is one of the names in Homer which is used to refer to the Greeks collectively.

The term "Achaean" is believed to be related to the Hittite term Ahhiyawa and t ...

'').Homer. ''Iliad''2.155–175

''Odyssey''

8.578

Amyntas I

Amyntas I (Greek: Ἀμύντας Aʹ; 498 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (c. 547 – 512 / 511 BC) and then a vassal of Darius I from 512/511 to his death 498 BC, at the time of Achaemenid Macedonia. He was a son of Alce ...

() ruled at the time of the Persian invasion Persian invasion may refer to:

* Persian invasion of Scythia, 513 BC

* Greco-Persian Wars

** First Persian invasion of Greece, 492–490 BC

** Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred duri ...

of Paeonia and when Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled ...

became a vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back t ...

of Achaemenid Persia. However, Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of A ...

() is the first truly historic figure. Based on this line of succession and an estimated average rule of 25 to 30 years, the beginnings of the Macedonian dynasty have thus been traditionally dated to 750 BC. Hammond supports the traditional view that the Temenidae did arrive from the Peloponnese and took charge of Macedonian leadership, possibly usurping rule from a native "Argead" dynasty with Illyrian help. However, other scholars doubt the veracity of their Peloponnesian origins. For example, Miltiades Hatzopoulos takes Appian's testimony to mean that the royal lineage imposed itself onto the tribes of the Middle Heliacmon from Argos Orestiko

Argos Orestiko ( el, Άργος Ορεστικό, , Orestean Argos, before 1926: Χρούπιστα - ''Chroupista''; rup, Hrupishte) is a town and a former municipality in the Kastoria regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government refo ...

n, whilst Eugene N. Borza argues that the Argeads were a family of notables hailing from Vergina.

Expansion from the core

Both Strabo and Thucydides said that Emathia and Pieria were mostly occupied by Thracians (Pieres

The Pieres ( Ancient Greek: Πίερες) were an ancient tribe that long before the archaic period in Greece occupied the narrow strip of plain land, or low hill, between the mouths of the Peneius and the HaliacmonE.C. Marchant, Commentary on Th ...

, Paeonians) and Bottiaeans, as well as some Illyrian and Epirote tribes. Herodotus states that the Bryges were cohabitants with the Macedonians before their mass migration to Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. If a group of ethnically definable Macedonian tribes were living in the Pierian highlands prior to their expansion, the first conquest was of the Pierian piedmont and coastal plain, including Vergina. The tribes may have launched their expansion from a base near Mount Bermion, according to Herodotus. Thucydides describes the Macedonian expansion specifically as a process of conquest led by the Argeads:Thucydides. ''History of the Peloponnesian War'', 2.99

Thucydides's account gives a geographical overview of Macedonian possessions at the time of Alexander I's rule. To reconstruct a chronology of the expansion by Alexander I's predecessors is more difficult, but generally, three stages have been proposed from Thucydides' reading. The initial and most important conquest was of Pieria and Bottiaea, including the locations of Pydna and

Thucydides's account gives a geographical overview of Macedonian possessions at the time of Alexander I's rule. To reconstruct a chronology of the expansion by Alexander I's predecessors is more difficult, but generally, three stages have been proposed from Thucydides' reading. The initial and most important conquest was of Pieria and Bottiaea, including the locations of Pydna and Dium

Dion ( el, Δίον; grc, Δῖον; la, Dium) is a village and municipal unit in the municipality of Dion-Olympos in the Pieria regional unit, Greece. It is located at the foot of Mount Olympus at a distance of 17 km from the capita ...

. The second stage consolidated rule in Pieria and Bottiaea, captured Methone and Pella, and extended rule over Eordaea

Eordaea ( el, Ἐορδαία) was a geographical region of upper Macedonia and later an administrative region of the kingdom of Macedon. Eordaea was located south of Lynkestis, west of Emathia, north of Elimiotis and east of Orestis.Dimitri ...

and Almopia. According to Hammond, the third stage occurred after 550 BC, when the Macedonians gained control over Mygdonia, Edonis

The B Engineering Edonis is a sports car developed in the year 2000 and manufactured by Italian automobile manufacturer B Engineering with overall engineering by Nicola Materazzi (ex Lancia, Ferrari & Bugatti) and styling by Marc Deschamps (e ...

, lower Paeonia, Bisaltia

Bisaltia ( el, Βισαλτία) or Bisaltica was an ancient country which was bordered by Sintice on the north, Crestonia on the west, Mygdonia on the south and was separated by Odomantis on the north-east and Edonis on the south-east by river ...

and Crestonia. However, the second stage might have occurred as late as 520 BC; and the third stage probably did not occur until after 479 BC, when the Macedonians capitalized on the weakened Paeonian state after the Persian withdrawal from Macedon and the rest of their mainland European territories.. Whatever the case, Thucydides' account of the Macedonian state describes its accumulated territorial extent by the rule of Perdiccas II

Perdiccas II ( gr, Περδίκκας, Perdíkkas) was a king of Macedonia from c. 448 BC to c. 413 BC. During the Peloponnesian War, he frequently switched sides between Sparta and Athens.

Family

Perdiccas II was the son of Alexander I, he ...

, Alexander I's son. Hammond has said that the early stages of Macedonian expansion were militaristic, subduing or expunging populations from a large and varied area. Pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands ( pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

and highland living could not support a very concentrated settlement density, forcing pastoralist tribes to search for more arable lowlands suitable for agriculture.

Ethnogenesis scenario

Present-day scholars have highlighted several inconsistencies in the traditionalist perspective first set in place by Hammond. An alternative model of state and ethnos formation, promulgated by an alliance of regional elites, which redates the creation of the Macedonian kingdom to the 6th century BC, was proposed in 2010.. According to these scholars, direct literary, archaeological, and linguistic evidence to support Hammond's contention that a distinct Macedonian ''ethnos'' had existed in the Haliacmon valley since the

Present-day scholars have highlighted several inconsistencies in the traditionalist perspective first set in place by Hammond. An alternative model of state and ethnos formation, promulgated by an alliance of regional elites, which redates the creation of the Macedonian kingdom to the 6th century BC, was proposed in 2010.. According to these scholars, direct literary, archaeological, and linguistic evidence to support Hammond's contention that a distinct Macedonian ''ethnos'' had existed in the Haliacmon valley since the Aegean civilizations

Aegean civilization is a general term for the Bronze Age civilizations of Greece around the Aegean Sea. There are three distinct but communicating and interacting geographic regions covered by this term: Crete, the Cyclades and the Greek mainla ...

is lacking. Hammond's interpretation has been criticized as a "conjectural reconstruction" from what appears during later, historical times.

Similarly, the historicity of migration, conquest and population expulsion have also been questioned. Thucydides's account of the forced expulsion of the Pierians and Bottiaeans could have been formed on the basis of his perceived similarity of names of the Pierians and Bottiaeans living in the Struma valley with the names of regions in Macedonia; whereas his account of Eordean extermination was formulated because such toponymic correspondences are absent. Likewise, the Argead conquest of Macedonia may be viewed as a commonly used literary topos

In classical Greek rhetoric, topos, ''pl.'' topoi, (from grc, τόπος "place", elliptical for grc, τόπος κοινός ''tópos koinós'', 'common place'), in Latin ''locus'' (from ''locus communis''), refers to a method for developing a ...

in classical Macedonian rhetoric. Tales of migration served to create complex genealogical connections between trans-regional ruling elites, while at the same time were used by the ruling dynasty to legitimize their rule, heroicize mythical ancestors and distance themselves from their subjects.

Conflict was a historical reality in the early Macedonian kingdom and pastoralist traditions allowed the potential for population mobility. Greek archaeologists have found that some of the passes linking the Macedonian highlands with the valley regions have been used for thousands of years. However, the archaeological evidence does not point to any significant disruptions between the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

and Hellenistic period in Macedonia. The general continuity of material culture,. settlement sites, and pre-Greek onomasticon contradict the alleged ethnic cleansing account of early Macedonian expansion.

The process of state formation in Macedonia was similar to that of its neighbours in Epirus, Illyria,

The process of state formation in Macedonia was similar to that of its neighbours in Epirus, Illyria, Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and Thessaly, whereby regional elites could mobilize disparate communities for the purpose of organizing land and resources. Local notables were often based in urban-like settlements, although contemporaneous historians often did not recognize them as '' poleis'' because they were not self-ruled but under the rule of a "king". From the mid-6th century, there appears a series of exceptionally rich burials throughout the regionin Trebeništa, Vergina, Sindos

Sindos ( el, Σίνδος; la, Sindus; is a suburb of Thessaloniki, Greece. It is the seat of the municipality of Delta. Sindos is home to the main campus of the Alexander Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki and the Industrial Zon ...

, Agia Paraskevi

Agia Paraskevi ( el, Αγία Παρασκευή, ''Agía Paraskeví'') is a suburb and a municipality in the northeastern part of the Athens agglomeration, Greece. It is part of the North Athens regional unit. Agia Paraskevi was named after the ...

, Pella-Archontiko, Aiani, Gevgelija

Gevgelija ( mk, Гевгелија; ) is a town with a population of 15,685 located in the very southeast of the North Macedonia along the banks of the Vardar River, situated at the country's main border with Greece (Bogorodica- Evzoni), the poi ...

, Amphipolissharing a similar burial rite and grave accompaniments, interpreted to represent the rise of a new regional ruling class sharing a common ideology, customs and religious beliefs. A common geography, mode of existence, and defensive interests might have necessitated the creation of a political confederacy among otherwise ethno-linguistically diverse communities, which led to the consolidation of a new Macedonian ethnic identity.

The traditional view that Macedonia was populated by rural ethnic groups in constant conflict is slowly changing, bridging the cultural gap between southern Epirus and the north Aegean region. Hatzopoulos's studies on Macedonian institutions have lent support to the hypothesis that Macedonian state formation occurred via an integration of regional elites, which were based in city-like centres, including the Argeadae at Vergina, the Paeonian/ Edonian peoples in Sindos, Ichnae and Pella, and the mixed Macedonian-Barbarian colonies in the Thermaic Gulf

The Thermaic Gulf (), also called the Gulf of Salonika and the Macedonian Gulf, is a gulf constituting the northwest corner of the Aegean Sea. The city of Thessaloniki is at its northeastern tip, and it is bounded by Pieria Imathia and Lariss ...

and western Chalkidiki.. The Temenidae became overall leaders of a new Macedonian state because of the diplomatic proficiency of Alexander I and the logistic centrality of Vergina itself. It has been suggested that a breakdown in traditional Balkan tribal traditions associated with adaptation of Aegean socio-political institutions created a climate of institutional flexibility in a vast, resource-rich land. Non-Argead centres increasingly became dependent allies, allowing the Argeads to gradually assert and secure their control over the lower and eastern territories of Macedonia. This control was fully consolidated by Phillip II ().

Culture and society

Macedonia had a distinct material culture by the Early Iron Age.. Typically Balkan burial, ornamental, and ceramic forms were used for most of the Iron Age. These features suggest broad cultural affinities and organizational structures analogous with Thracian, Epirote, and Illyrian regions.. This did not necessarily symbolize a shared cultural identity, or any political allegiance between these regions. In the late sixth century BC, Macedonia became open to south Greek influences, although a small but detectable amount of interaction with the south had been present since late Mycenaean times. By the 5th century BC, Macedonia was a part of the "Greek cultural milieu" according to Edward M. Anson, possessing many cultural traits typical of the southern Greek city-states.. Classical Greek objects and customs were appropriated selectively and used in peculiarly Macedonian ways.. In addition, influences from Achaemenid Persia in culture and economy are evident from the 5th century BC onward, such as the inclusion of Persian grave goods at Macedonian burial sites as well as the adoption of royal customs such as a Persian-style

Macedonia had a distinct material culture by the Early Iron Age.. Typically Balkan burial, ornamental, and ceramic forms were used for most of the Iron Age. These features suggest broad cultural affinities and organizational structures analogous with Thracian, Epirote, and Illyrian regions.. This did not necessarily symbolize a shared cultural identity, or any political allegiance between these regions. In the late sixth century BC, Macedonia became open to south Greek influences, although a small but detectable amount of interaction with the south had been present since late Mycenaean times. By the 5th century BC, Macedonia was a part of the "Greek cultural milieu" according to Edward M. Anson, possessing many cultural traits typical of the southern Greek city-states.. Classical Greek objects and customs were appropriated selectively and used in peculiarly Macedonian ways.. In addition, influences from Achaemenid Persia in culture and economy are evident from the 5th century BC onward, such as the inclusion of Persian grave goods at Macedonian burial sites as well as the adoption of royal customs such as a Persian-style throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the mon ...

during the reign of Philip II.

Economy, society, and social class

The way of life of the inhabitants of Upper Macedonia differed little from that of their neighbours in Epirus and Illyria, engaging in seasonal transhumance supplemented by agriculture. Young Macedonian men were typically expected to engage inhunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

and martial combat as a byproduct of their transhumance lifestyles of herding livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to ani ...

such as goats and sheep, while horse breeding and raising cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

were other common pursuits. In these mountainous regions, upland sites were important focal points for local communities. In these difficult terrains, competition for resources often precipitated intertribal conflict and raiding forays into the comparatively richer lowland settlements of coastal Macedonia and Thessaly. Despite the remoteness of the upper Macedonian highlands, excavations at Aiani since 1983 have discovered finds attesting to the presence of social organization since the 2nd millennium BC. The finds include the oldest pieces of black-and-white pottery, which is characteristic of the tribes of northwest Greece, discovered so far.. Found with Μycenaean sherds, they can be dated with certainty to the 14th century BC.. The finds also include some of the oldest samples of writing in Macedonia, among them inscriptions bearing Greek names like ''Θέμιδα'' (Themida). The inscriptions demonstrate that Hellenism in Upper Macedonia was at a high economic, artistic, and cultural level by the sixth century BCoverturning the notion that Upper Macedonia was culturally and socially isolated from the rest of ancient Greece.

By contrast, the alluvial plains of Lower Macedonia and Pelagonia, which had a comparative abundance of natural resources such as timber and minerals, favored the development of a native aristocracy, with a wealth that at times surpassed the classical Greek poleis. Exploitation of minerals helped expedite the introduction of coinage in Macedonia from the 5th century BC, developing under southern Greek, Thracian and Persian influences. Some Macedonians engaged in farming, often with irrigation, land reclamation, and horticulture

Horticulture is the branch of agriculture that deals with the art, science, technology, and business of plant cultivation. It includes the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, herbs, sprouts, mushrooms, algae, flowers, seaweeds and no ...

activities supported by the Macedonian state. However, the bedrock of the Macedonian economy and state finances was the twofold exploitation of the forests with logging and valuable mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s such as copper, iron, gold, and silver with mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the econom ...

. The conversion of these raw materials into finished products and their sale encouraged the growth of urban centers and a gradual shift away from the traditional rustic Macedonian lifestyle during the course of the 5th century BC..

Macedonian society was dominated by aristocratic families whose main source of wealth and prestige was their herds of horses and cattle. In this respect, Macedonia was similar to Thessaly and Thrace. These aristocrats were second only to the king in terms of power and privilege, filling the ranks of his administration and serving as commanding officers in the military. It was in the more bureaucratic regimes of the

Macedonian society was dominated by aristocratic families whose main source of wealth and prestige was their herds of horses and cattle. In this respect, Macedonia was similar to Thessaly and Thrace. These aristocrats were second only to the king in terms of power and privilege, filling the ranks of his administration and serving as commanding officers in the military. It was in the more bureaucratic regimes of the Hellenistic kingdoms

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wa ...

succeeding Alexander the Great's empire where greater social mobility for members of society seeking to join the aristocracy could be found, especially in Ptolemaic Egypt. In contrast with classical Greek poleis, the Macedonians held only few slaves.

However, unlike Thessaly, Macedonia was ruled by a monarchy from its earliest history until the Roman conquest in 167 BC. The nature of the kingship, however, remains debated. One viewpoint sees it as an autocracy, whereby the king held absolute power and was at the head of both government and society, wielding arguably unlimited authority to handle affairs of state and public policy. He was also the leader of a very personal regime with close relationships or connections to his '' hetairoi'', the core of the Macedonian aristocracy. Any other position of authority, including the army, was appointed at the whim of the king himself. The other, " constitutionalist", position argues that there was an evolution from a society of many minor "kings" – each of equal authority – to a sovereign military state whereby an army of citizen soldiers supported a central king against a rival class of nobility. Kingship was hereditary along the paternal line, yet it is unclear if primogeniture was strictly observed as an established custom.

During the Late Bronze Age (circa 15th-century BC), the ancient Macedonians developed distinct, matt-painted wares that evolved from Middle Helladic pottery traditions originating in central and southern Greece. The Macedonians continued to use an individualized form of material culturealbeit showing analogies in ceramic, ornamental and burial forms with the so-called Lausitz culture between 1200 and 900 BCand that of the Glasinac culture after circa 900 BC. While some of these influences persisted beyond the sixth century BC, a more ubiquitous presence of items of an Aegean-Mediterranean character is seen from the latter sixth century BC, as Greece recovered from its Dark Ages. Southern Greek impulses penetrated Macedonia via trade with north Aegean colonies such as Methone and those in the Chalcidice, neighbouring Thessaly, and from the Ionic colonies of Asia Minor. Ionic influences were later supplanted by those of Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

provenance. Thus, by the latter sixth century, local elites could acquire exotic Aegean items such as Athenian red figure pottery, fine tablewares, olive oil and wine amphorae, fine ceramic perfume flasks, glass, marble and precious metal ornamentsall of which would serve as status symbols. By the 5th century BC, these items became widespread in Macedonia and in much of the central Balkans.

Macedonian settlements have a strong continuity dating from the Bronze Age, maintaining traditional construction techniques for residential architecture. While settlement numbers appeared to drop in central and southern Greece after 1000 BC, there was a dramatic increase of settlements in Macedonia. These settlements seemed to have developed along raised promontories near river flood plains called '' tells'' (Greek: τύμβοι). Their ruins are most commonly found in western Macedonia between Florina and Lake Vergoritis, the upper and middle Haliacmon River, and Bottiaea. They can also be found on either side of the Axios and in the Chalcidice in eastern Macedonia.

Religion and funerary practices

By the 5th century BC the Macedonians and the rest of the Greeks worshiped more or less the same deities of the Greek pantheon. In Macedonia, politics and religion often intertwined. For instance, the head of state for the city of Amphipolis also served as the priest of Asklepios, Greek god of medicine; a similar arrangement existed at Cassandreia, where a cult priest honoring the city's founder Cassander was the nominal municipal leader. Foreign cults from Egypt were fostered by the royal court, such as the temple of

By the 5th century BC the Macedonians and the rest of the Greeks worshiped more or less the same deities of the Greek pantheon. In Macedonia, politics and religion often intertwined. For instance, the head of state for the city of Amphipolis also served as the priest of Asklepios, Greek god of medicine; a similar arrangement existed at Cassandreia, where a cult priest honoring the city's founder Cassander was the nominal municipal leader. Foreign cults from Egypt were fostered by the royal court, such as the temple of Sarapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian deity. The cult of Serapis was promoted during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his r ...

at Thessaloniki, while Macedonian kings Philip III of Macedon

Philip III Arrhidaeus ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος Ἀρριδαῖος ; c. 359 BC – 25 December 317 BC) reigned as king of Macedonia an Ancient Greek Kingdom in northern Greece from after 11 June 323 BC until his death. He was a son of King P ...

and Alexander IV of Macedon

Alexander IV (Greek: ; 323/322– 309 BC), sometimes erroneously called Aegus in modern times, was the son of Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) and Princess Roxana of Bactria.

Birth

Alexander IV was the son of Alexander th ...

made votive offerings to the internationally esteemed Samothrace temple complex of the Cabeiri mystery cult

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates ''(mystai)''. The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy as ...

.. This was also the same location where Perseus of Macedon fled and received sanctuary following his defeat by the Romans at the Battle of Pydna

The Battle of Pydna took place in 168 BC between Rome and Macedon during the Third Macedonian War. The battle saw the further ascendancy of Rome in the Hellenistic world and the end of the Antigonid line of kings, whose power traced back ...

in 168 BC. The main sanctuary of Zeus was maintained at Dion, while another at Veria was dedicated to Herakles and received particularly strong patronage from Demetrius II Aetolicus () when he intervened in the affairs of the municipal government at the behest of the cult's main priest.

The ancient Macedonians worshipped the Twelve Olympians, especially Zeus, Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified with ...

, Heracles, and Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; grc, wikt:Διόνυσος, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstas ...

. Evidence of this worship exists from the beginning of the 4th century BC onwards, but little evidence of Macedonian religious practices from earlier times exists.. From an early period, Zeus was the single most important deity in the Macedonian pantheon. Makedon, the mythical ancestor of the Macedonians, was held to be a son of Zeus, and Zeus features prominently in Macedonian coinage. The most important centre of worship of Zeus was at Dion in Pieria, the spiritual centre of the Macedonians, where beginning in 400 BC King Archelaus established an annual festival, which in honour of Zeus featured lavish sacrifices and athletic contests. Worship of Zeus's son Heracles was also prominent; coins featuring Heracles appear from the 5th century BC onwards. This was in large part because the Argead kings of Macedon traced their lineage to Heracles, making sacrifices to him in the Macedonian capitals of Vergina and Pella. Numerous votive reliefs and dedications also attest to the importance of the worship of Artemis.. Artemis was often depicted as a huntress and served as a tutelary goddess for young girls entering the coming-of-age process, much as Heracles Kynagidas (Hunter) did for young men who had completed it. By contrast, some deities popular elsewhere in the Greek worldnotably Poseidon and Hephaestuswere largely ignored by the Macedonians.

Other deities worshipped by the ancient Macedonians were part of a local pantheon which included Thaulos (god of war equated with Ares), Gyga (later equated with Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of v ...

), Gozoria (goddess of hunting equated with Artemis), Zeirene (goddess of love equated with Aphrodite

Aphrodite ( ; grc-gre, Ἀφροδίτη, Aphrodítē; , , ) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess . Aphrodite's major symbols incl ...

) and Xandos (god of light). A notable influence on Macedonian religious life and worship was neighbouring Thessaly; the two regions shared many similar cultural institutions. The Macedonians also worshiped non-Greek gods, such as the " Thracian horseman", Orpheus and Bendis, and other figures from Paleo-Balkan mythology. They were tolerant of, and open to, incorporating foreign religious influences such as the sun worship of the Paeonians. By the 4th century BC, there had been a significant fusion of Macedonian and common Greek religious identity,. but Macedonia was nevertheless characterized by an unusually diverse religious life. This diversity extended to the belief in magic, as evidenced by curse tablets. It was a significant but secret aspect of Greek cultural practice.

A notable feature of Macedonian culture was the ostentatious burials reserved for its rulers.. The Macedonian elite built lavish tombs at the time of death rather than constructing temples during life. Such traditions had been practiced throughout Greece and the central-west Balkans since the

A notable feature of Macedonian culture was the ostentatious burials reserved for its rulers.. The Macedonian elite built lavish tombs at the time of death rather than constructing temples during life. Such traditions had been practiced throughout Greece and the central-west Balkans since the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

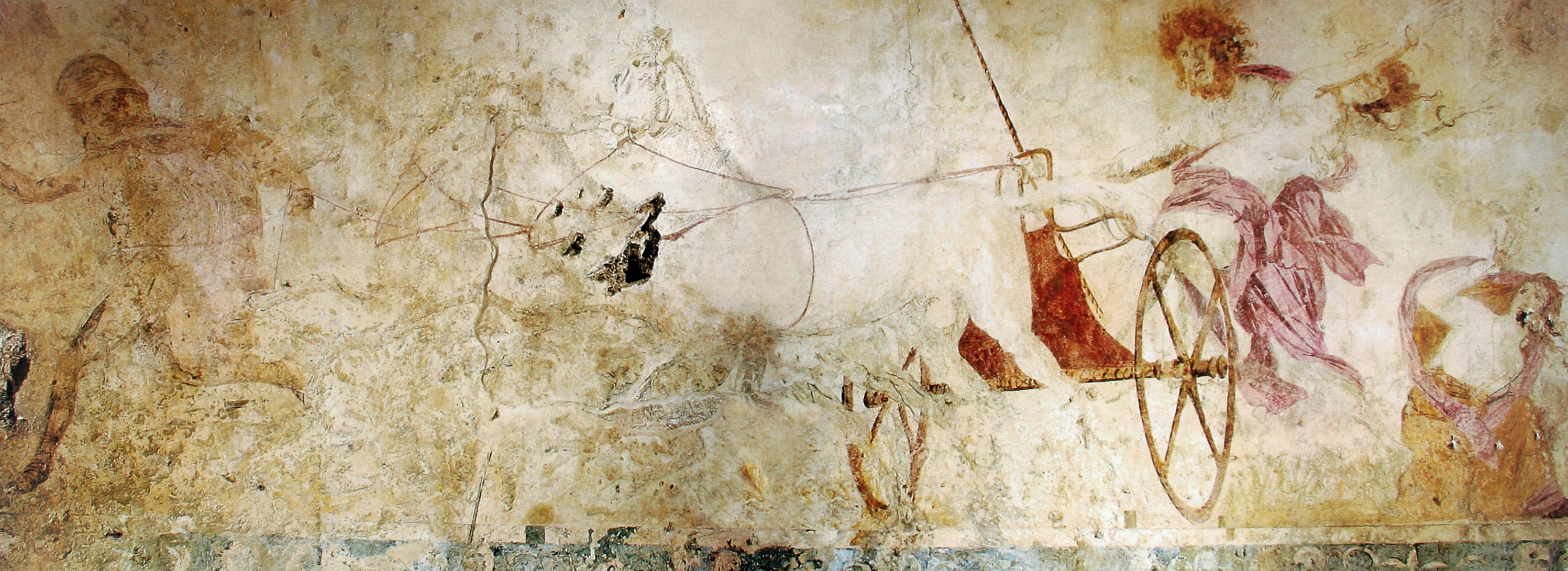

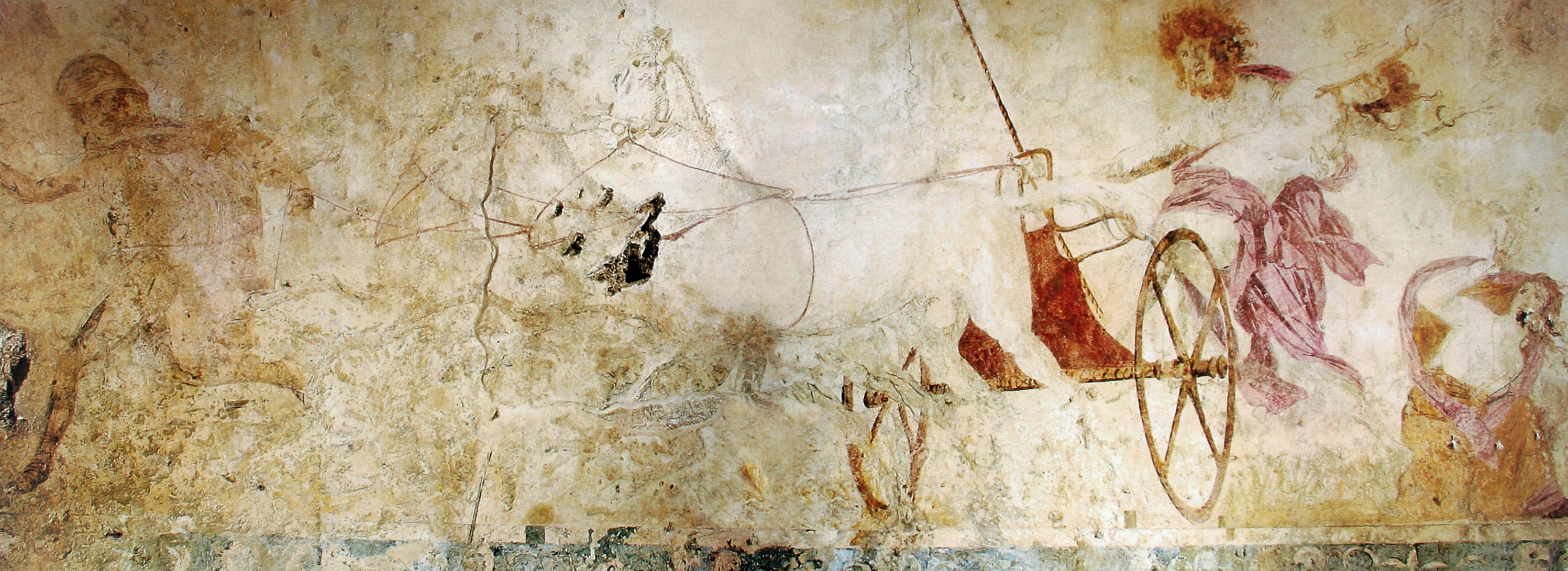

. Macedonian burials contain items similar to those at Mycenae, such as burial with weapons, gold death masks etc. From the sixth century, Macedonian burials became particularly lavish, displaying a rich variety of Greek imports reflecting the incorporation of Macedonia into a wider economic and political network centred on the Aegean city-states. Burials contained jewellery and ornaments of unprecedented wealth and artistic style. This zenith of Macedonian "warrior burial" style closely parallels those of sites in south-central Illyria and western Thrace, creating a '' koinon'' of elite burials. Lavish warrior burials had been discontinued in southern and central Greece from the seventh century onwards, where offerings at sanctuaries and the erection of temples became the norm.. From the sixth century BC, cremation replaced the traditional inhumation rite for elite Macedonians. One of the most lavish tombs dating from the 4th century BC, believed to be that of Phillip II, is at Vergina. It contains extravagant grave goods, highly sophisticated artwork depicting hunting scenes and Greek cultic figures, and a vast array of weaponry. This demonstrates a continuing tradition of the warrior society rather than a focus on religious piety and technology of the intellect, which had become paramount facets of central Greek society in the Classical Period. In the three royal tombs at Vergina, professional painters decorated the walls with a mythological scene of Hades abducting Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone ( ; gr, Περσεφόνη, Persephónē), also called Kore or Cora ( ; gr, Κόρη, Kórē, the maiden), is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld aft ...

(Tomb 1) and royal hunting scenes (Tomb 2), while lavish grave goods including weapons, armor, drinking vessels and personal items were housed with the dead, whose bones were burned before burial in decorated gold coffins. Some grave goods and decorations were common in other Macedonian tombs, yet some items found at Vergina were distinctly tied to royalty, including a diadem, luxurious goods, and arms and armor. Scholars have debated about the identity of the tomb occupants since the discovery of their remains in 1977–1978, yet recent research and forensic examination have concluded with certainty that at least one of the persons buried was Philip II (Tomb 2). Located near Tomb 1 are the above-ground ruins of a '' heroon'', a shrine for cult worship of the dead. In 2014, the ancient Macedonian Kasta Tomb, the largest ancient tomb found in Greece (as of 2017), was discovered outside of Amphipolis, a city that was incorporated into the Macedonian realm after its capture by Philip II in 357 BC... The identity of the tomb's occupant is unknown, but archaeologists have speculated that it may be Alexander's close friend Hephaestion.

The deification of Macedonian monarchs perhaps began with the death of Philip II, yet it was his son Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

who unambiguously claimed to be a living god. As pharaoh of the Egyptians, he was already entitled as Son of Ra

A son is a male offspring; a boy or a man in relation to his parents. The female counterpart is a daughter. From a biological perspective, a son constitutes a first degree relative.

Social issues

In pre-industrial societies and some current co ...

and considered the living incarnation of Horus by his Egyptian subjects (a belief that the Ptolemaic successors of Alexander would foster for their own dynasty in Egypt). However, following his visit to the oracle of Didyma in 334 BC that suggested his divinity, he traveled to the Oracle of Zeus Ammon

Amun (; also ''Amon'', ''Ammon'', ''Amen''; egy, jmn, reconstructed as (Old Egyptian and early Middle Egyptian) → (later Middle Egyptian) → (Late Egyptian), cop, Ⲁⲙⲟⲩⲛ, Amoun) romanized: ʾmn) was a major ancient Egyptian ...

(the Greek equivalent of the Egyptian Amun-Ra) at the Siwa Oasis of the Libyan Desert

The Libyan Desert (not to be confused with the Libyan Sahara) is a geographical region filling the north-eastern Sahara Desert, from eastern Libya to the Western Desert of Egypt and far northwestern Sudan. On medieval maps, its use predates ...

in 332 BC to confirm his divine status. After the priest there convinced him that Philip II was merely his mortal father and Zeus his actual father, Alexander began styling himself as the 'Son of Zeus', which brought him into contention with some of his Greek subjects who adamantly believed that living men could not be immortals. Although the Seleucid and Ptolemaic ''diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

'' successor states cultivated their own ancestral cults and deification of the rulers as part of state ideology, a similar cult did not exist in the Kingdom of Macedonia.

Visual arts

By the reign of Archelaus I of Macedon, the Macedonian elite started importing significantly greater customs, artwork, and art traditions from other regions of Greece. However, they still retained more archaic, perhapsHomer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

ic funerary rites connected with the symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

and drinking rites that were typified with items such as decorative metal kraters that held the ashes of deceased Macedonian nobility in their tombs.. Among these is the large bronze Derveni Krater

The Derveni Krater is a volute krater, the most elaborate of its type, discovered in 1962 in a tomb at Derveni, not far from Thessaloniki, and displayed at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Weighing 40 kg, it is made of a bronze wi ...

from a 4th-century BC tomb of Thessaloniki, decorated with scenes of the Greek god Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; grc, wikt:Διόνυσος, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstas ...

and his entourage and belonging to an aristocrat who had a military career. Macedonian metalwork usually followed Athenian styles of vase shapes from the 6th century BC onward, with drinking vessels, jewellery, containers, crowns, diadems, and coins among the many metal objects found in Macedonian tombs..

Surviving Macedonian painted artwork includes frescoes and mural

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' is a Spanis ...

s on walls, but also decoration on sculpted artwork such as statues and relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

s. For instance, trace colors still exist on the bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

s of the Alexander Sarcophagus. Macedonian paintings have allowed historians to investigate the clothing fashions as well as military gear worn by ancient Macedonians, such as the brightly-colored tomb paintings of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki

Agios Athanasios ( gr, Άγιος Αθανάσιος,) is a town and a former municipality in the Thessaloniki regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Chalkidona, of which it is a municipal un ...

showing figures wearing headgear ranging from feathered helmets to '' kausia'' and '' petasos'' caps.

Aside from metalwork and painting,

Aside from metalwork and painting, mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

s serve as another significant form of surviving Macedonian artwork, especially those discovered at Pella dating to the 4th century BC. The Stag Hunt Mosaic of Pella, with its three dimensional qualities and illusionist style, show clear influence from painted artwork and wider Hellenistic art trends, although the rustic theme of hunting was tailored for Macedonian tastes.. The similar Lion Hunt Mosaic of Pella illustrates either a scene of Alexander the Great with his companion Craterus

Craterus or Krateros ( el, Κρατερός; c. 370 BC – 321 BC) was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great and one of the Diadochi. Throughout his life he was a loyal royalist and supporter of Alexander the Great.Anson, Edward M. (20 ...

, or simply a conventional illustration of the generic royal diversion of hunting. Mosaics with mythological themes include scenes of Dionysus riding a panther and Helen of Troy being abducted by Theseus, the latter of which employs illusionist qualities and realistic shading similar to Macedonian paintings. Common themes of Macedonian paintings and mosaics include warfare, hunting and aggressive masculine sexuality (i.e. abduction of women for rape or marriage). In some instances these themes are combined within the same work, indicating a metaphorical connection that seems to be affirmed by later Byzantine Greek literature.

Theatre, music and performing arts

Philip II was assassinated by his bodyguard Pausanias of Orestis in 336 BC at thetheatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

of Aigai, Macedonia

Aegae or Aigai ( grc, Αἰγαί), also Aegeae or Aigeai (Αἰγέαι) was the original capital of the Macedonians, an ancient kingdom in Emathia in northern Greece.

The city was also the burial-place of the Macedonian kings, the dynasty whi ...

amid games and spectacles held inside that celebrated the marriage of his daughter Cleopatra of Macedon.. Alexander the Great was allegedly a great admirer of both theatre and music. He was especially fond of the plays by Classical Athenian tragedians Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Gree ...

, Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

, and Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

, whose works formed part of a proper Greek education for his new eastern subjects alongside studies in the Greek language and epics of Homer