algebraic variety on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in algebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics which uses abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, to solve geometry, geometrical problems. Classically, it studies zero of a function, zeros of multivariate polynomials; th ...

, a sub-field of mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

. Classically, an algebraic variety is defined as the set of solutions of a system of polynomial equations

A system of polynomial equations (sometimes simply a polynomial system) is a set of simultaneous equations where the are polynomials in several variables, say , over some Field (mathematics), field .

A ''solution'' of a polynomial system is a se ...

over the real or complex number

In mathematics, a complex number is an element of a number system that extends the real numbers with a specific element denoted , called the imaginary unit and satisfying the equation i^= -1; every complex number can be expressed in the for ...

s. Modern definitions generalize this concept in several different ways, while attempting to preserve the geometric intuition behind the original definition.

Conventions regarding the definition of an algebraic variety differ slightly. For example, some definitions require an algebraic variety to be irreducible, which means that it is not the union of two smaller sets that are closed in the Zariski topology

In algebraic geometry and commutative algebra, the Zariski topology is a topology defined on geometric objects called varieties. It is very different from topologies that are commonly used in real or complex analysis; in particular, it is not ...

. Under this definition, non-irreducible algebraic varieties are called algebraic sets. Other conventions do not require irreducibility.

The fundamental theorem of algebra

The fundamental theorem of algebra, also called d'Alembert's theorem or the d'Alembert–Gauss theorem, states that every non-constant polynomial, constant single-variable polynomial with Complex number, complex coefficients has at least one comp ...

establishes a link between algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract systems, known as algebraic structures, and the manipulation of expressions within those systems. It is a generalization of arithmetic that introduces variables and algebraic ope ...

and geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

by showing that a monic polynomial

In algebra, a monic polynomial is a non-zero univariate polynomial (that is, a polynomial in a single variable) in which the leading coefficient (the nonzero coefficient of highest degree) is equal to 1. That is to say, a monic polynomial is one ...

(an algebraic object) in one variable with complex number coefficients is determined by the set of its roots

A root is the part of a plant, generally underground, that anchors the plant body, and absorbs and stores water and nutrients.

Root or roots may also refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''The Root'' (magazine), an online magazine focusin ...

(a geometric object) in the complex plane

In mathematics, the complex plane is the plane (geometry), plane formed by the complex numbers, with a Cartesian coordinate system such that the horizontal -axis, called the real axis, is formed by the real numbers, and the vertical -axis, call ...

. Generalizing this result, Hilbert's Nullstellensatz

In mathematics, Hilbert's Nullstellensatz (German for "theorem of zeros", or more literally, "zero-locus-theorem") is a theorem that establishes a fundamental relationship between geometry and algebra. This relationship is the basis of algebraic ge ...

provides a fundamental correspondence between ideals of polynomial ring

In mathematics, especially in the field of algebra, a polynomial ring or polynomial algebra is a ring formed from the set of polynomials in one or more indeterminates (traditionally also called variables) with coefficients in another ring, ...

s and algebraic sets. Using the ''Nullstellensatz'' and related results, mathematicians have established a strong correspondence between questions on algebraic sets and questions of ring theory. This correspondence is a defining feature of algebraic geometry.

Many algebraic varieties are differentiable manifold

In mathematics, a differentiable manifold (also differential manifold) is a type of manifold that is locally similar enough to a vector space to allow one to apply calculus. Any manifold can be described by a collection of charts (atlas). One ...

s, but an algebraic variety may have singular points while a differentiable manifold cannot. Algebraic varieties can be characterized by their dimension

In physics and mathematics, the dimension of a mathematical space (or object) is informally defined as the minimum number of coordinates needed to specify any point within it. Thus, a line has a dimension of one (1D) because only one coo ...

. Algebraic varieties of dimension one are called ''algebraic curve

In mathematics, an affine algebraic plane curve is the zero set of a polynomial in two variables. A projective algebraic plane curve is the zero set in a projective plane of a homogeneous polynomial in three variables. An affine algebraic plane cu ...

s'' and algebraic varieties of dimension two are called ''algebraic surface

In mathematics, an algebraic surface is an algebraic variety of dimension two. In the case of geometry over the field of complex numbers, an algebraic surface has complex dimension two (as a complex manifold, when it is non-singular) and so of di ...

s''.

In the context of modern scheme theory, an algebraic variety over a field is an integral (irreducible and reduced) scheme over that field whose structure morphism is separated and of finite type.

Overview and definitions

An ''affine variety'' over analgebraically closed field

In mathematics, a field is algebraically closed if every non-constant polynomial in (the univariate polynomial ring with coefficients in ) has a root in . In other words, a field is algebraically closed if the fundamental theorem of algebra ...

is conceptually the easiest type of variety to define, which will be done in this section. Next, one can define projective and quasi-projective varieties in a similar way. The most general definition of a variety is obtained by patching together smaller quasi-projective varieties. It is not obvious that one can construct genuinely new examples of varieties in this way, but Nagata gave an example of such a new variety in the 1950s.

Affine varieties

For an algebraically closed field and anatural number

In mathematics, the natural numbers are the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, and so on, possibly excluding 0. Some start counting with 0, defining the natural numbers as the non-negative integers , while others start with 1, defining them as the positive in ...

, let be an affine -space over , identified to through the choice of an affine coordinate system. The polynomials in the ring can be viewed as ''K''-valued functions on by evaluating at the points in , i.e. by choosing values in ''K'' for each ''xi''. For each set ''S'' of polynomials in , define the zero-locus ''Z''(''S'') to be the set of points in on which the functions in ''S'' simultaneously vanish, that is to say

:

A subset ''V'' of is called an affine algebraic set if ''V'' = ''Z''(''S'') for some ''S''. A nonempty affine algebraic set ''V'' is called irreducible if it cannot be written as the union of two proper algebraic subsets. An irreducible affine algebraic set is also called an affine variety. (Some authors use the phrase ''affine variety'' to refer to any affine algebraic set, irreducible or not.Hartshorne, p.xv, Harris, p.3)

Affine varieties can be given a natural topology by declaring the closed set

In geometry, topology, and related branches of mathematics, a closed set is a Set (mathematics), set whose complement (set theory), complement is an open set. In a topological space, a closed set can be defined as a set which contains all its lim ...

s to be precisely the affine algebraic sets. This topology is called the Zariski topology.

Given a subset ''V'' of , we define ''I''(''V'') to be the ideal of all polynomial functions vanishing on ''V'':

:

For any affine algebraic set ''V'', the coordinate ring or structure ring of ''V'' is the quotient

In arithmetic, a quotient (from 'how many times', pronounced ) is a quantity produced by the division of two numbers. The quotient has widespread use throughout mathematics. It has two definitions: either the integer part of a division (in th ...

of the polynomial ring by this ideal.

Projective varieties and quasi-projective varieties

Let be an algebraically closed field and let be the projective ''n''-space over . Let in be ahomogeneous polynomial

In mathematics, a homogeneous polynomial, sometimes called quantic in older texts, is a polynomial whose nonzero terms all have the same degree. For example, x^5 + 2 x^3 y^2 + 9 x y^4 is a homogeneous polynomial of degree 5, in two variables ...

of degree ''d''. It is not well-defined to evaluate on points in in homogeneous coordinates

In mathematics, homogeneous coordinates or projective coordinates, introduced by August Ferdinand Möbius in his 1827 work , are a system of coordinates used in projective geometry, just as Cartesian coordinates are used in Euclidean geometry. ...

. However, because is homogeneous, meaning that , it ''does'' make sense to ask whether vanishes at a point . For each set ''S'' of homogeneous polynomials, define the zero-locus of ''S'' to be the set of points in on which the functions in ''S'' vanish:

:

A subset ''V'' of is called a projective algebraic set if ''V'' = ''Z''(''S'') for some ''S''. An irreducible projective algebraic set is called a projective variety.

Projective varieties are also equipped with the Zariski topology by declaring all algebraic sets to be closed.

Given a subset ''V'' of , let ''I''(''V'') be the ideal generated by all homogeneous polynomials vanishing on ''V''. For any projective algebraic set ''V'', the coordinate ring

In algebraic geometry, an affine variety or affine algebraic variety is a certain kind of algebraic variety that can be described as a subset of an affine space.

More formally, an affine algebraic set is the set of the common zeros over an algeb ...

of ''V'' is the quotient of the polynomial ring by this ideal.

A quasi-projective variety In mathematics, a quasi-projective variety in algebraic geometry is a locally closed subset of a projective variety, i.e., the intersection inside some projective space of a Zariski-open and a Zariski topology, Zariski-closed subset. A similar defin ...

is a Zariski open subset of a projective variety. Notice that every affine variety is quasi-projective. Notice also that the complement of an algebraic set in an affine variety is a quasi-projective variety; in the context of affine varieties, such a quasi-projective variety is usually not called a variety but a constructible set.

Abstract varieties

In classical algebraic geometry, all varieties were by definition quasi-projective varieties, meaning that they were open subvarieties of closed subvarieties of aprojective space

In mathematics, the concept of a projective space originated from the visual effect of perspective, where parallel lines seem to meet ''at infinity''. A projective space may thus be viewed as the extension of a Euclidean space, or, more generally ...

. For example, in Chapter 1 of Hartshorne a ''variety'' over an algebraically closed field is defined to be a quasi-projective variety In mathematics, a quasi-projective variety in algebraic geometry is a locally closed subset of a projective variety, i.e., the intersection inside some projective space of a Zariski-open and a Zariski topology, Zariski-closed subset. A similar defin ...

, but from Chapter 2 onwards, the term variety (also called an abstract variety) refers to a more general object, which locally is a quasi-projective variety, but when viewed as a whole is not necessarily quasi-projective; i.e. it might not have an embedding into projective space

In mathematics, the concept of a projective space originated from the visual effect of perspective, where parallel lines seem to meet ''at infinity''. A projective space may thus be viewed as the extension of a Euclidean space, or, more generally ...

. So classically the definition of an algebraic variety required an embedding into projective space, and this embedding was used to define the topology on the variety and the regular function

In algebraic geometry, a morphism between algebraic varieties is a function between the varieties that is given locally by polynomials. It is also called a regular map. A morphism from an algebraic variety to the affine line is also called a reg ...

s on the variety. The disadvantage of such a definition is that not all varieties come with natural embeddings into projective space. For example, under this definition, the product is not a variety until it is embedded into a larger projective space; this is usually done by the Segre embedding. Furthermore, any variety that admits one embedding into projective space admits many others, for example by composing the embedding with the Veronese embedding In mathematics, the Veronese surface is an algebraic surface in five-dimensional projective space, and is realized by the Veronese embedding, the embedding of the projective plane given by the complete linear system of conics. It is named after Giu ...

; thus many notions that should be intrinsic, such as that of a regular function, are not obviously so.

The earliest successful attempt to define an algebraic variety abstractly, without an embedding, was made by André Weil

André Weil (; ; 6 May 1906 – 6 August 1998) was a French mathematician, known for his foundational work in number theory and algebraic geometry. He was one of the most influential mathematicians of the twentieth century. His influence is du ...

. In his ''Foundations of Algebraic Geometry

''Foundations of Algebraic Geometry'' is a book by that develops algebraic geometry over field (mathematics), fields of any characteristic (algebra), characteristic. In particular it gives a careful treatment of intersection theory by defining th ...

,'' using valuations. Claude Chevalley

Claude Chevalley (; 11 February 1909 – 28 June 1984) was a French mathematician who made important contributions to number theory, algebraic geometry, class field theory, finite group theory and the theory of algebraic groups. He was a found ...

made a definition of a scheme, which served a similar purpose, but was more general. However, Alexander Grothendieck

Alexander Grothendieck, later Alexandre Grothendieck in French (; ; ; 28 March 1928 – 13 November 2014), was a German-born French mathematician who became the leading figure in the creation of modern algebraic geometry. His research ext ...

's definition of a scheme is more general still and has received the most widespread acceptance. In Grothendieck's language, an abstract algebraic variety is usually defined to be an integral

In mathematics, an integral is the continuous analog of a Summation, sum, which is used to calculate area, areas, volume, volumes, and their generalizations. Integration, the process of computing an integral, is one of the two fundamental oper ...

, separated scheme of finite type over an algebraically closed field, although some authors drop the irreducibility or the reducedness or the separateness condition or allow the underlying field to be not algebraically closed.Liu, Qing. ''Algebraic Geometry and Arithmetic Curves'', p. 55 Definition 2.3.47, and p. 88 Example 3.2.3 Classical algebraic varieties are the quasiprojective integral separated finite type schemes over an algebraically closed field.

Existence of non-quasiprojective abstract algebraic varieties

One of the earliest examples of a non-quasiprojective algebraic variety were given by Nagata. Nagata's example was not complete (the analog of compactness), but soon afterwards he found an algebraic surface that was complete and non-projective. Since then other examples have been found: for example, it is straightforward to constructtoric varieties

In algebraic geometry, a toric variety or torus embedding is an algebraic variety containing an algebraic torus as an open dense subset, such that the action of the torus on itself extends to the whole variety. Some authors also require it to be ...

that are not quasi-projective but complete.

Examples

Subvariety

A subvariety is a subset of a variety that is itself a variety (with respect to the topological structure induced by the ambient variety). For example, every open subset of a variety is a variety. See also closed immersion.Hilbert's Nullstellensatz

In mathematics, Hilbert's Nullstellensatz (German for "theorem of zeros", or more literally, "zero-locus-theorem") is a theorem that establishes a fundamental relationship between geometry and algebra. This relationship is the basis of algebraic ge ...

says that closed subvarieties of an affine or projective variety are in one-to-one correspondence with the prime ideals or non-irrelevant homogeneous prime ideals of the coordinate ring of the variety.

Affine variety

Example 1

Let , and A2 be the two-dimensionalaffine space

In mathematics, an affine space is a geometric structure that generalizes some of the properties of Euclidean spaces in such a way that these are independent of the concepts of distance and measure of angles, keeping only the properties relat ...

over C. Polynomials in the ring C 'x'', ''y''can be viewed as complex valued functions on A2 by evaluating at the points in A2. Let subset ''S'' of C 'x'', ''y''contain a single element :

:

The zero-locus of is the set of points in A2 on which this function vanishes: it is the set of all pairs of complex numbers (''x'', ''y'') such that ''y'' = 1 − ''x''. This is called a line in the affine plane. (In the classical topology coming from the topology on the complex numbers, a complex line is a real manifold of dimension two.) This is the set :

:

Thus the subset of A2 is an algebraic set

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in algebraic geometry, a sub-field of mathematics. Classically, an algebraic variety is defined as the set of solutions of a system of polynomial equations over the real or complex numbers. ...

. The set ''V'' is not empty. It is irreducible, as it cannot be written as the union of two proper algebraic subsets. Thus it is an affine algebraic variety.

Example 2

Let , and A2 be the two-dimensional affine space over C. Polynomials in the ring C 'x'', ''y''can be viewed as complex valued functions on A2 by evaluating at the points in A2. Let subset ''S'' of C 'x'', ''y''contain a single element ''g''(''x'', ''y''): : The zero-locus of ''g''(''x'', ''y'') is the set of points in A2 on which this function vanishes, that is the set of points (''x'',''y'') such that ''x''2 + ''y''2 = 1. As ''g''(''x'', ''y'') is anabsolutely irreducible In mathematics, a multivariate polynomial defined over the rational numbers is absolutely irreducible if it is irreducible over the complex field.. For example, x^2+y^2-1 is absolutely irreducible, but while x^2+y^2 is irreducible over the integ ...

polynomial, this is an algebraic variety. The set of its real points (that is the points for which ''x'' and ''y'' are real numbers), is known as the unit circle

In mathematics, a unit circle is a circle of unit radius—that is, a radius of 1. Frequently, especially in trigonometry, the unit circle is the circle of radius 1 centered at the origin (0, 0) in the Cartesian coordinate system in the Eucli ...

; this name is also often given to the whole variety.

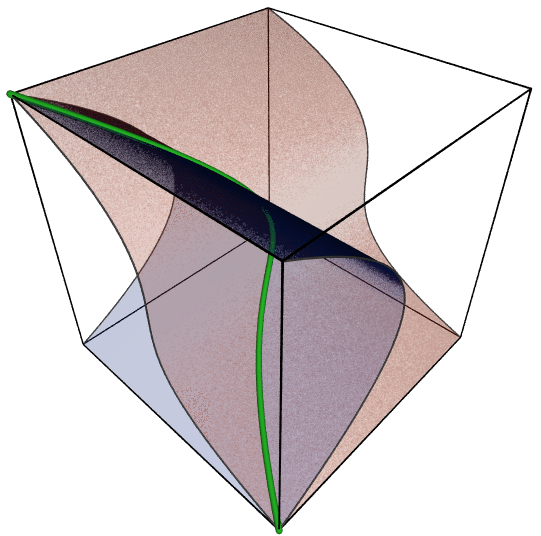

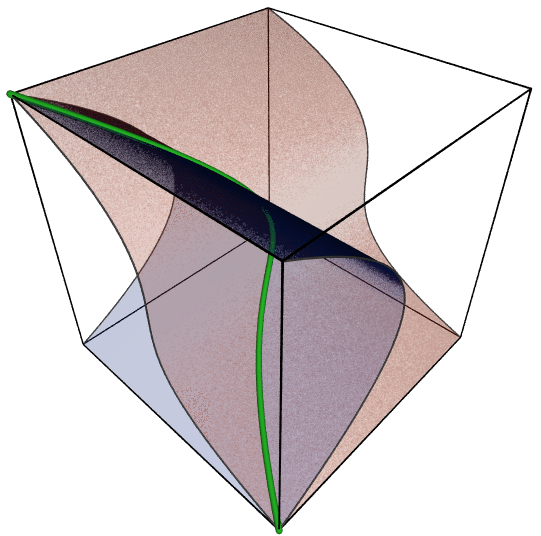

Example 3

The following example is neither ahypersurface

In geometry, a hypersurface is a generalization of the concepts of hyperplane, plane curve, and surface. A hypersurface is a manifold or an algebraic variety of dimension , which is embedded in an ambient space of dimension , generally a Euclidea ...

, nor a linear space, nor a single point. Let A3 be the three-dimensional affine space over C. The set of points (''x'', ''x''2, ''x''3) for ''x'' in C is an algebraic variety, and more precisely an algebraic curve that is not contained in any plane.Harris, p.9; that it is irreducible is stated as an exercise in Hartshorne p.7 It is the twisted cubic shown in the above figure. It may be defined by the equations

:

The irreducibility of this algebraic set needs a proof. One approach in this case is to check that the projection (''x'', ''y'', ''z'') → (''x'', ''y'') is injective

In mathematics, an injective function (also known as injection, or one-to-one function ) is a function that maps distinct elements of its domain to distinct elements of its codomain; that is, implies (equivalently by contraposition, impl ...

on the set of the solutions and that its image is an irreducible plane curve.

For more difficult examples, a similar proof may always be given, but may imply a difficult computation: first a Gröbner basis

In mathematics, and more specifically in computer algebra, computational algebraic geometry, and computational commutative algebra, a Gröbner basis is a particular kind of generating set of an ideal in a polynomial ring K _1,\ldots,x_n/math> ove ...

computation to compute the dimension, followed by a random linear change of variables (not always needed); then a Gröbner basis

In mathematics, and more specifically in computer algebra, computational algebraic geometry, and computational commutative algebra, a Gröbner basis is a particular kind of generating set of an ideal in a polynomial ring K _1,\ldots,x_n/math> ove ...

computation for another monomial order

In mathematics, a monomial order (sometimes called a term order or an admissible order) is a total order on the set of all ( monic) monomials in a given polynomial ring, satisfying the property of respecting multiplication, i.e.,

* If u \leq v an ...

ing to compute the projection and to prove that it is generically injective and that its image is a hypersurface

In geometry, a hypersurface is a generalization of the concepts of hyperplane, plane curve, and surface. A hypersurface is a manifold or an algebraic variety of dimension , which is embedded in an ambient space of dimension , generally a Euclidea ...

, and finally a polynomial factorization

In mathematics and computer algebra, factorization of polynomials or polynomial factorization expresses a polynomial with coefficients in a given field or in the integers as the product of irreducible factors with coefficients in the same doma ...

to prove the irreducibility of the image.

General linear group

The set of ''n''-by-''n'' matrices over the base field ''k'' can be identified with the affine ''n''2-space with coordinates such that is the (''i'', ''j'')-th entry of the matrix . Thedeterminant

In mathematics, the determinant is a Scalar (mathematics), scalar-valued function (mathematics), function of the entries of a square matrix. The determinant of a matrix is commonly denoted , , or . Its value characterizes some properties of the ...

is then a polynomial in and thus defines the hypersurface in . The complement of is then an open subset of that consists of all the invertible ''n''-by-''n'' matrices, the general linear group

In mathematics, the general linear group of degree n is the set of n\times n invertible matrices, together with the operation of ordinary matrix multiplication. This forms a group, because the product of two invertible matrices is again inve ...

. It is an affine variety, since, in general, the complement of a hypersurface in an affine variety is affine. Explicitly, consider where the affine line is given coordinate ''t''. Then amounts to the zero-locus in of the polynomial in :

:

i.e., the set of matrices ''A'' such that has a solution. This is best seen algebraically: the coordinate ring of is the localization , which can be identified with .

The multiplicative group k* of the base field ''k'' is the same as and thus is an affine variety. A finite product of it is an algebraic torus

In mathematics, an algebraic torus, where a one dimensional torus is typically denoted by \mathbf G_, \mathbb_m, or \mathbb, is a type of commutative affine algebraic group commonly found in Projective scheme, projective algebraic geometry and tor ...

, which is again an affine variety.

A general linear group is an example of a linear algebraic group

In mathematics, a linear algebraic group is a subgroup of the group of invertible n\times n matrices (under matrix multiplication) that is defined by polynomial equations. An example is the orthogonal group, defined by the relation M^TM = I_n ...

, an affine variety that has a structure of a group

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic iden ...

in such a way the group operations are morphism of varieties.

Characteristic variety

Let ''A'' be a not-necessarily-commutative algebra over a field ''k''. Even if ''A'' is not commutative, it can still happen that ''A'' has a -filtration so that the associated ring is commutative, reduced and finitely generated as a ''k''-algebra; i.e., is the coordinate ring of an affine (reducible) variety ''X''. For example, if ''A'' is theuniversal enveloping algebra

In mathematics, the universal enveloping algebra of a Lie algebra is the unital associative algebra whose representations correspond precisely to the representations of that Lie algebra.

Universal enveloping algebras are used in the representa ...

of a finite-dimensional Lie algebra

In mathematics, a Lie algebra (pronounced ) is a vector space \mathfrak g together with an operation called the Lie bracket, an alternating bilinear map \mathfrak g \times \mathfrak g \rightarrow \mathfrak g, that satisfies the Jacobi ident ...

, then is a polynomial ring (the PBW theorem); more precisely, the coordinate ring of the dual vector space .

Let ''M'' be a filtered module over ''A'' (i.e., ). If is fintiely generated as a -algebra, then the support of in ''X''; i.e., the locus where does not vanish is called the characteristic variety of ''M''. The notion plays an important role in the theory of ''D''-modules.

Projective variety

Aprojective variety

In algebraic geometry, a projective variety is an algebraic variety that is a closed subvariety of a projective space. That is, it is the zero-locus in \mathbb^n of some finite family of homogeneous polynomials that generate a prime ideal, th ...

is a closed subvariety of a projective space. That is, it is the zero locus of a set of homogeneous polynomials

In mathematics, a homogeneous polynomial, sometimes called quantic in older texts, is a polynomial whose nonzero terms all have the same degree. For example, x^5 + 2 x^3 y^2 + 9 x y^4 is a homogeneous polynomial of degree 5, in two variables ...

that generate a prime ideal

In algebra, a prime ideal is a subset of a ring (mathematics), ring that shares many important properties of a prime number in the ring of Integer#Algebraic properties, integers. The prime ideals for the integers are the sets that contain all th ...

.

Example 1

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The projective line

In projective geometry and mathematics more generally, a projective line is, roughly speaking, the extension of a usual line by a point called a '' point at infinity''. The statement and the proof of many theorems of geometry are simplified by the ...

P1 is an example of a projective curve; it can be viewed as the curve in the projective plane defined by . For another example, first consider the affine cubic curve

:

in the 2-dimensional affine space (over a field of characteristic not two). It has the associated cubic homogeneous polynomial equation:

:

which defines a curve in P2 called an elliptic curve

In mathematics, an elliptic curve is a smooth, projective, algebraic curve of genus one, on which there is a specified point . An elliptic curve is defined over a field and describes points in , the Cartesian product of with itself. If the ...

. The curve has genus one (genus formula

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial spec ...

); in particular, it is not isomorphic to the projective line P1, which has genus zero. Using genus to distinguish curves is very basic: in fact, the genus is the first invariant one uses to classify curves (see also the construction of moduli of algebraic curves).

Example 2: Grassmannian

Let ''V'' be a finite-dimensional vector space. The Grassmannian variety ''Gn''(''V'') is the set of all ''n''-dimensional subspaces of ''V''. It is a projective variety: it is embedded into a projective space via thePlücker embedding

In mathematics, the Plücker map embeds the Grassmannian \mathrm(k,V), whose elements are ''k''-Dimension (vector space), dimensional Linear subspace, subspaces of an ''n''-dimensional vector space ''V'', either real or complex, in a projective sp ...

:

:

where ''bi'' are any set of linearly independent vectors in ''V'', is the ''n''-th exterior power

In mathematics, the exterior algebra or Grassmann algebra of a vector space V is an associative algebra that contains V, which has a product, called exterior product or wedge product and denoted with \wedge, such that v\wedge v=0 for every vector ...

of ''V'', and the bracket 'w''means the line spanned by the nonzero vector ''w''.

The Grassmannian variety comes with a natural vector bundle

In mathematics, a vector bundle is a topological construction that makes precise the idea of a family of vector spaces parameterized by another space X (for example X could be a topological space, a manifold, or an algebraic variety): to eve ...

(or locally free sheaf

In mathematics, especially in algebraic geometry and the theory of complex manifolds, coherent sheaves are a class of sheaves closely linked to the geometric properties of the underlying space. The definition of coherent sheaves is made with refer ...

in other terminology) called the tautological bundle, which is important in the study of characteristic class

In mathematics, a characteristic class is a way of associating to each principal bundle of ''X'' a cohomology class of ''X''. The cohomology class measures the extent to which the bundle is "twisted" and whether it possesses sections. Characterist ...

es such as Chern class

In mathematics, in particular in algebraic topology, differential geometry and algebraic geometry, the Chern classes are characteristic classes associated with complex vector bundles. They have since become fundamental concepts in many branches ...

es.

Jacobian variety and abelian variety

Let ''C'' be a smooth complete curve and thePicard group

In mathematics, the Picard group of a ringed space ''X'', denoted by Pic(''X''), is the group of isomorphism classes of invertible sheaves (or line bundles) on ''X'', with the group operation being tensor product. This construction is a global ver ...

of it; i.e., the group of isomorphism classes of line bundles on ''C''. Since ''C'' is smooth, can be identified as the divisor class group

In algebraic geometry, divisors are a generalization of codimension-1 subvarieties of algebraic varieties. Two different generalizations are in common use, Cartier divisors and Weil divisors (named for Pierre Cartier and André Weil by David Mumf ...

of ''C'' and thus there is the degree homomorphism . The Jacobian variety

In mathematics, the Jacobian variety ''J''(''C'') of a non-singular algebraic curve ''C'' of genus ''g'' is the moduli space of degree 0 line bundles. It is the connected component of the identity in the Picard group of ''C'', hence an abelia ...

of ''C'' is the kernel of this degree map; i.e., the group of the divisor classes on ''C'' of degree zero. A Jacobian variety is an example of an abelian variety

In mathematics, particularly in algebraic geometry, complex analysis and algebraic number theory, an abelian variety is a smooth Algebraic variety#Projective variety, projective algebraic variety that is also an algebraic group, i.e., has a group ...

, a complete variety with a compatible abelian group

In mathematics, an abelian group, also called a commutative group, is a group in which the result of applying the group operation to two group elements does not depend on the order in which they are written. That is, the group operation is commu ...

structure on it (the name "abelian" is however not because it is an abelian group). An abelian variety turns out to be projective (in short, algebraic theta function

In mathematics, theta functions are special functions of several complex variables. They show up in many topics, including Abelian varieties, moduli spaces, quadratic forms, and solitons. Theta functions are parametrized by points in a tube ...

s give an embedding into a projective space. See equations defining abelian varieties In mathematics, the concept of abelian variety is the higher-dimensional generalization of the elliptic curve. The equations defining abelian varieties are a topic of study because every abelian variety is a projective variety. In dimension ''d'' � ...

); thus, is a projective variety. The tangent space to at the identity element is naturally isomorphic to hence, the dimension of is the genus of .

Fix a point on . For each integer , there is a natural morphism

: