Acceleration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Accelerations are

An object's average acceleration over a period of

An object's average acceleration over a period of

Instantaneous acceleration, meanwhile, is the limit of the average acceleration over an infinitesimal interval of time. In the terms of

Instantaneous acceleration, meanwhile, is the limit of the average acceleration over an infinitesimal interval of time. In the terms of

The velocity of a particle moving on a curved path as a

The velocity of a particle moving on a curved path as a

''Uniform'' or ''constant'' acceleration is a type of motion in which the velocity of an object changes by an equal amount in every equal time period.

A frequently cited example of uniform acceleration is that of an object in

''Uniform'' or ''constant'' acceleration is a type of motion in which the velocity of an object changes by an equal amount in every equal time period.

A frequently cited example of uniform acceleration is that of an object in

measuring 3-axis acceleration * Space travel using constant acceleration * Specific force

Acceleration Calculator

Simple acceleration unit converter

Acceleration Calculator

Acceleration Conversion calculator converts units form meter per second square, kilometer per second square, millimeter per second square & more with metric conversion. {{Authority control Dynamics (mechanics) Kinematic properties Temporal rates Vector physical quantities

vector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

quantities (in that they have magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

and direction). The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by the orientation of the ''net'' force acting on that object. The magnitude of an object's acceleration, as described by Newton's Second Law

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

, is the combined effect of two causes:

* the net balance of all external forces acting onto that object — magnitude is directly proportional

In mathematics, two sequences of numbers, often experimental data, are proportional or directly proportional if their corresponding elements have a constant ratio, which is called the coefficient of proportionality or proportionality constan ...

to this net resulting force;

* that object's mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different eleme ...

, depending on the materials out of which it is made — magnitude is inversely proportional

In mathematics, two sequences of numbers, often experimental data, are proportional or directly proportional if their corresponding elements have a constant ratio, which is called the coefficient of proportionality or proportionality constan ...

to the object's mass.

The SI unit for acceleration is metre per second squared

The metre per second squared is the unit of acceleration in the International System of Units (SI). As a derived unit, it is composed from the SI base units of length, the metre, and time, the second. Its symbol is written in several forms as m/ ...

(, ).

For example, when a vehicle

A vehicle (from la, vehiculum) is a machine that transports people or cargo. Vehicles include wagons, bicycles, motor vehicles (motorcycles, cars, trucks, buses, mobility scooters for disabled people), railed vehicles (trains, trams), ...

starts from a standstill (zero velocity, in an inertial frame of reference

In classical physics and special relativity, an inertial frame of reference (also called inertial reference frame, inertial frame, inertial space, or Galilean reference frame) is a frame of reference that is not undergoing any acceleration. ...

) and travels in a straight line at increasing speeds, it is accelerating in the direction of travel. If the vehicle turns, an acceleration occurs toward the new direction and changes its motion vector. The acceleration of the vehicle in its current direction of motion is called a linear (or tangential during circular motions) acceleration, the reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

* Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

*Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and m ...

to which the passengers on board experience as a force pushing them back into their seats. When changing direction, the effecting acceleration is called radial (or centripetal during circular motions) acceleration, the reaction to which the passengers experience as a centrifugal force. If the speed of the vehicle decreases, this is an acceleration in the opposite direction and mathematically a negative, sometimes called deceleration or retardation, and passengers experience the reaction to deceleration as an inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law ...

l force pushing them forward. Such negative accelerations are often achieved by retrorocket

A retrorocket (short for ''retrograde rocket'') is a rocket engine providing thrust opposing the motion of a vehicle, thereby causing it to decelerate. They have mostly been used in spacecraft, with more limited use in short-runway aircraft land ...

burning in spacecraft. Both acceleration and deceleration are treated the same, as they are both changes in velocity. Each of these accelerations (tangential, radial, deceleration) is felt by passengers until their relative (differential) velocity are neutralized in reference to the acceleration due to change in speed.

Definition and properties

Average acceleration

time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

is its change in velocity, , divided by the duration of the period, . Mathematically,

Instantaneous acceleration

calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithm ...

, instantaneous acceleration is the derivative

In mathematics, the derivative of a function of a real variable measures the sensitivity to change of the function value (output value) with respect to a change in its argument (input value). Derivatives are a fundamental tool of calculus. ...

of the velocity vector with respect to time:

As acceleration is defined as the derivative of velocity, , with respect to time and velocity is defined as the derivative of position, , with respect to time, acceleration can be thought of as the second derivative

In calculus, the second derivative, or the second order derivative, of a function is the derivative of the derivative of . Roughly speaking, the second derivative measures how the rate of change of a quantity is itself changing; for example, ...

of with respect to :

(Here and elsewhere, if motion is in a straight line, vector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

quantities can be substituted by scalars in the equations.)

By the fundamental theorem of calculus

The fundamental theorem of calculus is a theorem that links the concept of differentiating a function (calculating its slopes, or rate of change at each time) with the concept of integrating a function (calculating the area under its graph, or ...

, it can be seen that the integral

In mathematics, an integral assigns numbers to functions in a way that describes displacement, area, volume, and other concepts that arise by combining infinitesimal data. The process of finding integrals is called integration. Along wit ...

of the acceleration function is the velocity function ; that is, the area under the curve of an acceleration vs. time ( vs. ) graph corresponds to the change of velocity.

Likewise, the integral of the jerk function , the derivative of the acceleration function, can be used to find the change of acceleration at a certain time:

Units

Acceleration has thedimensions

In physics and mathematics, the dimension of a mathematical space (or object) is informally defined as the minimum number of coordinates needed to specify any point within it. Thus, a line has a dimension of one (1D) because only one coordin ...

of velocity (L/T) divided by time, i.e. L T−2. The SI unit of acceleration is the metre per second squared

The metre per second squared is the unit of acceleration in the International System of Units (SI). As a derived unit, it is composed from the SI base units of length, the metre, and time, the second. Its symbol is written in several forms as m/ ...

(m s−2); or "metre per second per second", as the velocity in metres per second changes by the acceleration value, every second.

Other forms

An object moving in a circular motion—such as a satellite orbiting the Earth—is accelerating due to the change of direction of motion, although its speed may be constant. In this case it is said to be undergoing ''centripetal'' (directed towards the center) acceleration. Proper acceleration, the acceleration of a body relative to a free-fall condition, is measured by an instrument called anaccelerometer

An accelerometer is a tool that measures proper acceleration. Proper acceleration is the acceleration (the rate of change of velocity) of a body in its own instantaneous rest frame; this is different from coordinate acceleration, which is acc ...

.

In classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, and astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. For objects governed by classi ...

, for a body with constant mass, the (vector) acceleration of the body's center of mass is proportional to the net force vector (i.e. sum of all forces) acting on it ( Newton’s second law):

where is the net force acting on the body, is the mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different eleme ...

of the body, and is the center-of-mass acceleration. As speeds approach the speed of light, relativistic effects become increasingly large.

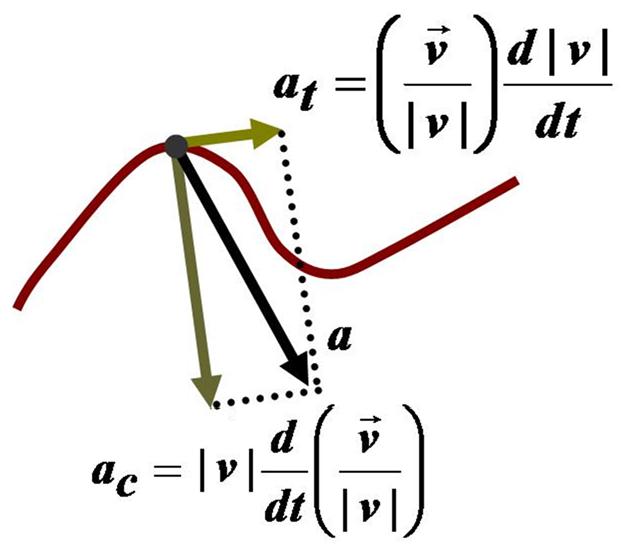

Tangential and centripetal acceleration

function

Function or functionality may refer to:

Computing

* Function key, a type of key on computer keyboards

* Function model, a structured representation of processes in a system

* Function object or functor or functionoid, a concept of object-oriente ...

of time can be written as:

with equal to the speed of travel along the path, and

a unit vector tangent to the path pointing in the direction of motion at the chosen moment in time. Taking into account both the changing speed and the changing direction of , the acceleration of a particle moving on a curved path can be written using the chain rule

In calculus, the chain rule is a formula that expresses the derivative of the composition of two differentiable functions and in terms of the derivatives of and . More precisely, if h=f\circ g is the function such that h(x)=f(g(x)) for every , ...

of differentiation for the product of two functions of time as:

where is the unit (inward) normal vector to the particle's trajectory (also called ''the principal normal''), and is its instantaneous radius of curvature

In differential geometry, the radius of curvature, , is the reciprocal of the curvature. For a curve, it equals the radius of the circular arc which best approximates the curve at that point. For surfaces, the radius of curvature is the radius o ...

based upon the osculating circle

In differential geometry of curves, the osculating circle of a sufficiently smooth plane curve at a given point ''p'' on the curve has been traditionally defined as the circle passing through ''p'' and a pair of additional points on the curve i ...

at time . These components are called the tangential acceleration and the normal or radial acceleration (or centripetal acceleration in circular motion, see also circular motion and centripetal force).

Geometrical analysis of three-dimensional space curves, which explains tangent, (principal) normal and binormal, is described by the Frenet–Serret formulas

In differential geometry, the Frenet–Serret formulas describe the kinematic properties of a particle moving along a differentiable curve in three-dimensional Euclidean space \mathbb^, or the geometric properties of the curve itself irrespective ...

.

Special cases

Uniform acceleration

''Uniform'' or ''constant'' acceleration is a type of motion in which the velocity of an object changes by an equal amount in every equal time period.

A frequently cited example of uniform acceleration is that of an object in

''Uniform'' or ''constant'' acceleration is a type of motion in which the velocity of an object changes by an equal amount in every equal time period.

A frequently cited example of uniform acceleration is that of an object in free fall

In Newtonian physics, free fall is any motion of a body where gravity is the only force acting upon it. In the context of general relativity, where gravitation is reduced to a space-time curvature, a body in free fall has no force acting on ...

in a uniform gravitational field. The acceleration of a falling body in the absence of resistances to motion is dependent only on the gravitational field strength (also called ''acceleration due to gravity''). By Newton's Second Law

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

the force acting on a body is given by:

Because of the simple analytic properties of the case of constant acceleration, there are simple formulas relating the displacement, initial and time-dependent velocities, and acceleration to the time elapsed:

where

* is the elapsed time,

* is the initial displacement from the origin,

* is the displacement from the origin at time ,

* is the initial velocity,

* is the velocity at time , and

* is the uniform rate of acceleration.

In particular, the motion can be resolved into two orthogonal parts, one of constant velocity and the other according to the above equations. As Galileo showed, the net result is parabolic motion, which describes, e. g., the trajectory of a projectile in a vacuum near the surface of Earth.

Circular motion

In uniform circular motion, that is moving with constant ''speed'' along a circular path, a particle experiences an acceleration resulting from the change of the direction of the velocity vector, while its magnitude remains constant. The derivative of the location of a point on a curve with respect to time, i.e. its velocity, turns out to be always exactly tangential to the curve, respectively orthogonal to the radius in this point. Since in uniform motion the velocity in the tangential direction does not change, the acceleration must be in radial direction, pointing to the center of the circle. This acceleration constantly changes the direction of the velocity to be tangent in the neighboring point, thereby rotating the velocity vector along the circle. * For a given speed , the magnitude of this geometrically caused acceleration (centripetal acceleration) is inversely proportional to the radius of the circle, and increases as the square of this speed: * Note that, for a given angular velocity , the centripetal acceleration is directly proportional to radius . This is due to the dependence of velocity on the radius . Expressing centripetal acceleration vector in polar components, where is a vector from the centre of the circle to the particle with magnitude equal to this distance, and considering the orientation of the acceleration towards the center, yields As usual in rotations, the speed of a particle may be expressed as an ''angular speed'' with respect to a point at the distance as Thus This acceleration and the mass of the particle determine the necessary centripetal force, directed ''toward'' the centre of the circle, as the net force acting on this particle to keep it in this uniform circular motion. The so-called ' centrifugal force', appearing to act outward on the body, is a so-called pseudo force experienced in the frame of reference of the body in circular motion, due to the body'slinear momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass a ...

, a vector tangent to the circle of motion.

In a nonuniform circular motion, i.e., the speed along the curved path is changing, the acceleration has a non-zero component tangential to the curve, and is not confined to the principal normal, which directs to the center of the osculating circle, that determines the radius for the centripetal acceleration. The tangential component is given by the angular acceleration , i.e., the rate of change of the angular speed times the radius . That is,

The sign of the tangential component of the acceleration is determined by the sign of the angular acceleration (), and the tangent is always directed at right angles to the radius vector.

Relation to relativity

Special relativity

The special theory of relativity describes the behavior of objects traveling relative to other objects at speeds approaching that of light in a vacuum. Newtonian mechanics is exactly revealed to be an approximation to reality, valid to great accuracy at lower speeds. As the relevant speeds increase toward the speed of light, acceleration no longer follows classical equations. As speeds approach that of light, the acceleration produced by a given force decreases, becoming infinitesimally small as light speed is approached; an object with mass can approach this speed asymptotically, but never reach it.General relativity

Unless the state of motion of an object is known, it is impossible to distinguish whether an observed force is due to gravity or to acceleration—gravity and inertial acceleration have identical effects.Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

called this the equivalence principle, and said that only observers who feel no force at all—including the force of gravity—are justified in concluding that they are not accelerating.Brian Greene, '' The Fabric of the Cosmos: Space, Time, and the Texture of Reality'', page 67. Vintage

Conversions

See also

* Acceleration (differential geometry) *Four-vector

In special relativity, a four-vector (or 4-vector) is an object with four components, which transform in a specific way under Lorentz transformations. Specifically, a four-vector is an element of a four-dimensional vector space considered as a ...

: making the connection between space and time explicit

* Gravitational acceleration

* Inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law ...

* Orders of magnitude (acceleration)

* Shock (mechanics)

A mechanical or physical shock is a sudden acceleration caused, for example, by impact, drop, kick, earthquake, or explosion. Shock is a transient physical excitation.

Shock describes matter subject to extreme rates of force with respect to tim ...

* Shock and vibration data loggermeasuring 3-axis acceleration * Space travel using constant acceleration * Specific force

References

External links

Acceleration Calculator

Simple acceleration unit converter

Acceleration Calculator

Acceleration Conversion calculator converts units form meter per second square, kilometer per second square, millimeter per second square & more with metric conversion. {{Authority control Dynamics (mechanics) Kinematic properties Temporal rates Vector physical quantities