Zhang Guotao on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

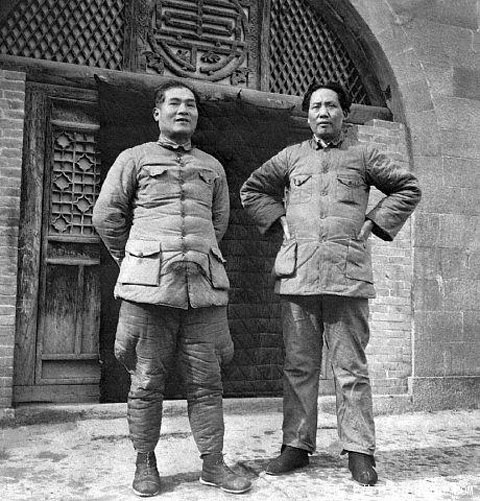

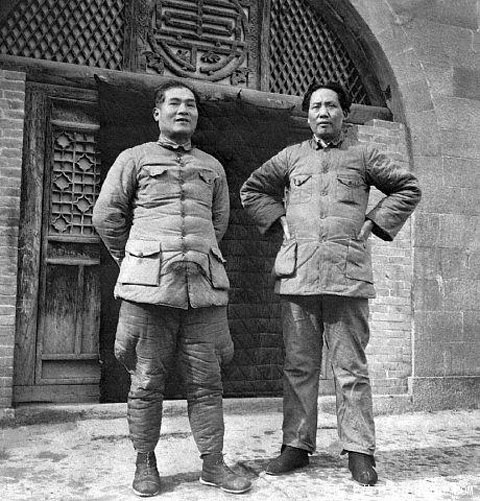

Zhang Guotao (November 26, 1897 – December 3, 1979), or Chang Kuo-tao, was a founding member of the

"The man who could have been Mao"

''The Toronto Star'', Sep 26, 2009.Short, Philip. Mao: A Life. New York: John Macrae / Owl Book, 2001. Print. Zhang acted as the CCP's top party official at the first

When Zhang reached the new CCP base at

When Zhang reached the new CCP base at High Tide of Terror

Mar. 5, 1956, ''

"The man who could have been Mao"

''The Toronto Star'', September 26, 2009. Useful summary of Zhang's life based largely on Chang Jung, Jon Halliday, '' Mao The Unknown Story'' (2005). {{DEFAULTSORT:Zhang, Guotao 1897 births 1979 deaths Chinese Christians Converts to Christianity Chinese Communist Party politicians from Jiangxi National University of Peking alumni Politicians from Pingxiang People of the Chinese Civil War Republic of China politicians from Jiangxi Chinese communists Members of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party Members of the 2nd Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Communist Party Politicians from Toronto People from Scarborough, Toronto Chinese emigrants to Canada Chinese exiles Chinese Civil War refugees Members of the 4th Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Communist Party Members of the 6th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party

Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

(CCP) and rival to Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

. During the 1920s he studied in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and became a key contact with the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

, organizing the CCP labor movement in the United Front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

with the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

. In 1931, after the Party had been driven from the cities, he established the E- Yu- Wan Soviet. When his armies were driven from the region, he joined the Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

but lost a contentious struggle for party leadership to Mao Zedong. Zhang's armies then took a different route from Mao's and were badly beaten by local muslim Ma clique forces in Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

. When his depleted forces finally arrived to join Mao in Yan'an

Yan'an (; ), alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several counties, including Zhidan (formerly Bao'an) ...

, Zhang continued his losing challenge to Mao, and left the party in 1938. Zhang eventually retired to Canada, in 1968. He became a Christian shortly before his death in Scarborough, Ontario (a suburb of Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

), in 1979. His memoirs provide valuable and vivid information on his life and party history.

Early and student life

Born in Pingxiang County,Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

, Zhang was involved in revolutionary activities during his youth. Zhang studied Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

thought under Li Dazhao while attending Peking University

Peking University (PKU; ) is a public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education.

Peking University was established as the Imperial University of Peking in 1898 when it received its royal charte ...

in 1916. After his active role in the May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chin ...

in 1919, Zhang became one of the most prominent student leaders and later joined the early organization of the CCP in October 1920. At the same time, Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

was a librarian working at Peking University; the two knew each other.Schiller, Bill"The man who could have been Mao"

''The Toronto Star'', Sep 26, 2009.Short, Philip. Mao: A Life. New York: John Macrae / Owl Book, 2001. Print. Zhang acted as the CCP's top party official at the first

National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

The National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (; literally: Chinese Communist Party National Representatives Congress) is a party congress that is held every five years. The National Congress is theoretically the highest body within t ...

in 1921 and was elected a member of the Central Bureau of the CCP in charge of organizing the work of Professional revolutionaries

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishm ...

. After the congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, Zhang held the position of Director of Secretariat of the China Labor Union and Chief Editor of ''Labor Weekly'', from which he became an expert in labor unions and mobilization. He led several major strikes of railway and textile workers, which made him a pioneer of the labor movement in China along with such figures as Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi ( ; 24 November 189812 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary, politician, and theorist. He was Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee from 1954 to 1959, First Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party from 1956 to 1966 and ...

and Li Lisan.

Communist Party career

In 1924 Zhang attended the First National Congress of theKuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

(KMT) during the policy of alliance between the Communists and the Kuomintang and was elected as Substitute Commissioner of Central Executive Committee. This was despite the fact that Zhang had opposed the alliance with Kuomintang in the Third National Congress of the CCP and had been reprimanded. In 1925 in the Fourth National Congress of the CCP, Zhang was elected Commissioner of Central Committee of CCP and Director of Labor & Peasant Work Department. In 1926 Zhang was the General Secretary of Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The p ...

Division of CCP, and in 1927 he was Commissioner of Interim Central Committee of the CCP after the failure of the CCP uprising. Zhang with Li Lisan and Qu Qiubai

Qu Qiubai (; 29 January 1899 – 18 June 1935) was a leader of the Chinese Communist Party in the late 1920s. He was born in Changzhou, Jiangsu, China.

Early life

Qu was born in Changzhou, Jiangsu. His family lived in Tianxiang Lou () l ...

were the acting leaders of the CCP. At that time Mao only led a small number of troops in Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

and Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

. In 1928 Zhang was elected as a member of the politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

of the CCP in the Sixth National Congress held in Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and then as a delegate of the CCP in Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

. But because of his disagreements with the Soviet Union and Comintern policies on the Chinese revolution, in the 1920s Zhang was taken into custody and punished in order to correct his mistakes. However, due to his fame and popularity in the communist world, he wasn't exiled like other dissidents were at that time.

In 1931 Zhang expressed his repentance and was sent back to China by the Comintern to clean up the mess left by the power struggle between the 28 Bolsheviks, Li Lisan, and other old CCP members. Zhang used his fame and popularity to correct their extremism and appeased the old CCP members. But the damage done by the power struggle was so great that it was too difficult for the CCP to survive in the cities governed by the Kuomintang. Therefore, Zhang and other acting CCP leaders decided to move their groups to bases in the countryside. Zhang was assigned to lead the daily operation of E- Yu- Wan Revolutionary Base at the border of Hubei, Henan, and Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

provinces as General Secretary and chairman of the military committee, and then Vice Chairman of the Interim Central Government of the Chinese Soviet Republic

The Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) was an East Asian proto-state in China, proclaimed on 7 November 1931 by Chinese communist leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De in the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. The discontiguous territories of t ...

when Mao was the chairman. Possibly influenced by life in Stalin's Soviet Union, Zhang carried out strict purges to persecute dissidents.

Military leadership

In 1932 Zhang led the 4th Red Army intoSichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

and set up another base. Slowly he turned it into a prosperous autonomous region by way of land reform and enlisting the support of locals, establishing the Northwest Chinese Soviet Federation. However, once the prosperity was in reach, Zhang repeated the Stalinist style purges again, as a result, he and the Red Army lost the popular support, and was driven from the Red base. In 1935 Zhang and his army of more than 80,000 reunited with Mao's 10,000 troops during the Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

. It was not long before Mao and Zhang were locked in disagreements over issues of strategy and tactics, causing a split in the Red Army. The main disagreement was Zhang's insistence on moving southward to establish a new base in the region of Sichuan that was populated by ethnic minorities. Mao pointed out the flaws of such a move, pointing out the difficulties to establish any communist base in regions where the general populace was hostile, and insisted on moving northward to reach the communist base in Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

. Zhang tried to have Mao and his followers arrested and killed if needed, but his plan was foiled by his own staff members Ye Jianying and Yang Shangkun, who fled to Mao's headquarters to inform Mao about Zhang's plot, taking the all of the codebooks and maps with them. As a result, Mao immediately moved his troop northward and thus escaped arrest and possible death.

Zhang decided to carry out his plan on his own, with disastrous results: over 75% of his original 80,000 + troops were lost in his adventure. Zhang was forced to admit defeat and retreat to the communist base in Shaanxi. More disastrous than losing most of his troops, the failure discredited Zhang among his own followers, who turned to Mao. Furthermore, because all of the codebooks were obtained by Mao, Zhang lost contact with Comintern while Mao was able to establish the link, this coupled with the fact of Zhang's disastrous defeat, discredited Zhang within Comintern, which begun to give greater support for Mao.

Zhang's remaining troops of 21,800 were later annihilated in 1936 by the superior force of more than 100,000 combined troops of warlords Ma Bufang

Ma Bufang (1903 – 31 July 1975) (, Xiao'erjing: ) was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general.

General Ma started an industrialization pro ...

, Ma Hongbin and Ma Zhongying during efforts to cross the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan Ha ...

and conquer Ma's territory. Zhang lost the power and influence to be able to challenge Mao and had to accept his failure as a result of the disaster which only left him 427 surviving troops from the original 21,800.

In 2006, the writer and producer, Sun Shuyun, provided an account of the Long March that took exception to various ways in which the event has been propagandized. Although critical of Zhang Guotao, she argued that there was no evidence of a so-called "secret telegram" that had been intercepted by Mao in which Zhang intended to use force against the Central Committee. Moreover, she shows that the official History of the Chinese Communist Party was revised in 2002 to say that Zhang Guotao did not order the Western Legion into Gansu in order to build up his own power base. Rather, all orders originated from the Central Committee .

End of CCP career and exile

When Zhang reached the new CCP base at

When Zhang reached the new CCP base at Yan'an

Yan'an (; ), alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several counties, including Zhidan (formerly Bao'an) ...

, he had fallen from power and became an easy target for Mao. Zhang kept the now figurehead position of Chairman of Yan'an Frontier Area and was frequently subjected to humiliation by Mao and his allies. Zhang was too proud to ally with Wang Ming

Wang may refer to:

Names

* Wang (surname) (王), a common Chinese surname

* Wāng (汪), a less common Chinese surname

* Titles in Chinese nobility

* A title in Korean nobility

* A title in Mongolian nobility

Places

* Wang River in Thaila ...

, who had recently come back from Moscow and was acting as the Comintern's representative in China. Zhang's popularity in the Comintern might have given him another chance of returning to power if he had allied with Wang. Another reason why Zhang did not ally with Wang was that Wang boasted that it was under his order that five senior CCP leaders (Yu Xiusong, Huang Chao, Li Te and two others—all opponents of Wang) had been arrested, and now worked for warlord Sheng Shicai in Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

under the direction of the CCP. All five were tortured and executed in a prison under the control of Sheng Shicai, having been labeled as Trotskyists. However, Sheng Shicai was acting under direction from the CCP under Wang Ming. After that incident, Zhang despised Wang and would never consider supporting him.

Without any supporters, Zhang was purged in 1937 at the Extended Meeting of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party, after which he defected to the Kuomintang in 1938. But without any power, resources, and support, Zhang never held any important positions afterward and only did research on the CCP for Dai Li. After the defeat of the Kuomintang in 1949 he went into exile in Hong Kong. He emigrated to Canada with his wife Tzi Li Young in 1968 to join their two sons who were already living in Toronto.

He gave his only interview in 1974, when he told a Canadian Press

The Canadian Press (CP; french: La Presse canadienne, ) is a Canadian national news agency headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. Established in 1917 as a vehicle for the time's Canadian newspapers to exchange news and information, The Canadian Pre ...

reporter, "I have washed my hands of politics". In 1978, he converted to Christianity under the influence of a Chinese scholar, Zhang Li Sang. After suffering several strokes, he died in a Scarborough, Ontario, nursing home on December 3, 1979, at the age of 82. He is buried in the Pine Hills Cemetery in Scarborough.

Zhang was highly critical of the proceedings of the first PRC Police leader Luo Ruiqing

Luo Ruiqing (; May 31, 1906 – August 3, 1978), formerly romanized as Lo Jui-ch'ing, was a Chinese army officer and politician, general of the People's Liberation Army. He created the People's Republic of China's security and police appar ...

during the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

.Mar. 5, 1956, ''

Time Magazine

''Time'' (stylized in all caps) is an American news magazine based in New York City. For nearly a century, it was published weekly, but starting in March 2020 it transitioned to every other week. It was first published in New York City on Ma ...

''

See also

*Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

*Wang Ming

Wang may refer to:

Names

* Wang (surname) (王), a common Chinese surname

* Wāng (汪), a less common Chinese surname

* Titles in Chinese nobility

* A title in Korean nobility

* A title in Mongolian nobility

Places

* Wang River in Thaila ...

References

Further reading

* Chang Kuo-t'ao, ''The Rise of the Chinese Communist Party'' (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1971). * Tony Saich, ed. with a contribution from Benjamin Yang, ''The Rise to Power of the Chinese Communist Party: Documents and Analysis'' (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1996 ). Extensive commentary and primary documents. * Sun Shuyun, ''The Long March'' (London: Harper Collins, 2006). * Benjamin Yang (Bingzhang Yang), ''From Revolution to Politics: Chinese Communists on the Long March''. (Boulder: Westview, 1990; 338p. ). Detailed analysis of the conflict with Mao after the Zunyi Conference. * Bill Schiller"The man who could have been Mao"

''The Toronto Star'', September 26, 2009. Useful summary of Zhang's life based largely on Chang Jung, Jon Halliday, '' Mao The Unknown Story'' (2005). {{DEFAULTSORT:Zhang, Guotao 1897 births 1979 deaths Chinese Christians Converts to Christianity Chinese Communist Party politicians from Jiangxi National University of Peking alumni Politicians from Pingxiang People of the Chinese Civil War Republic of China politicians from Jiangxi Chinese communists Members of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party Members of the 2nd Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Communist Party Politicians from Toronto People from Scarborough, Toronto Chinese emigrants to Canada Chinese exiles Chinese Civil War refugees Members of the 4th Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Communist Party Members of the 6th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party