Zachary Taylor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

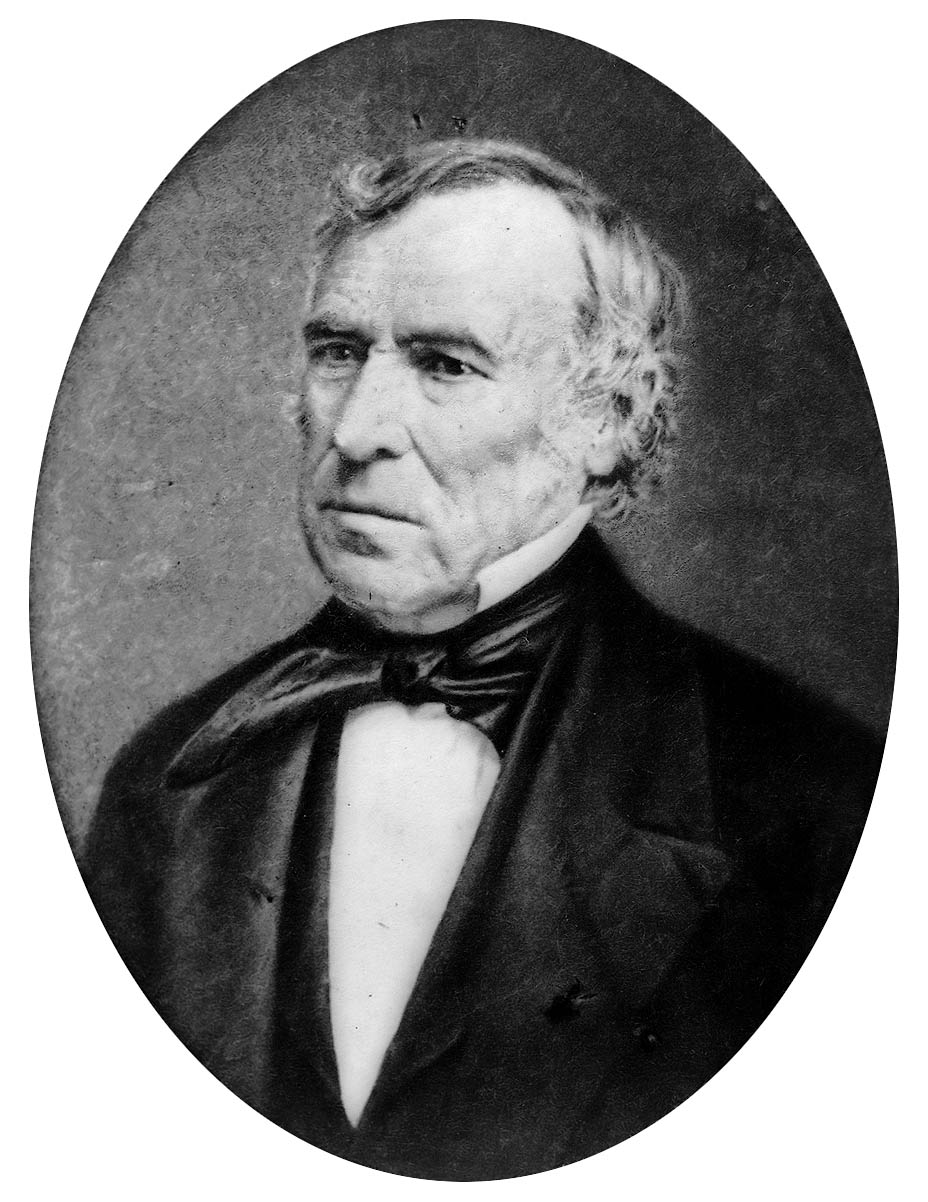

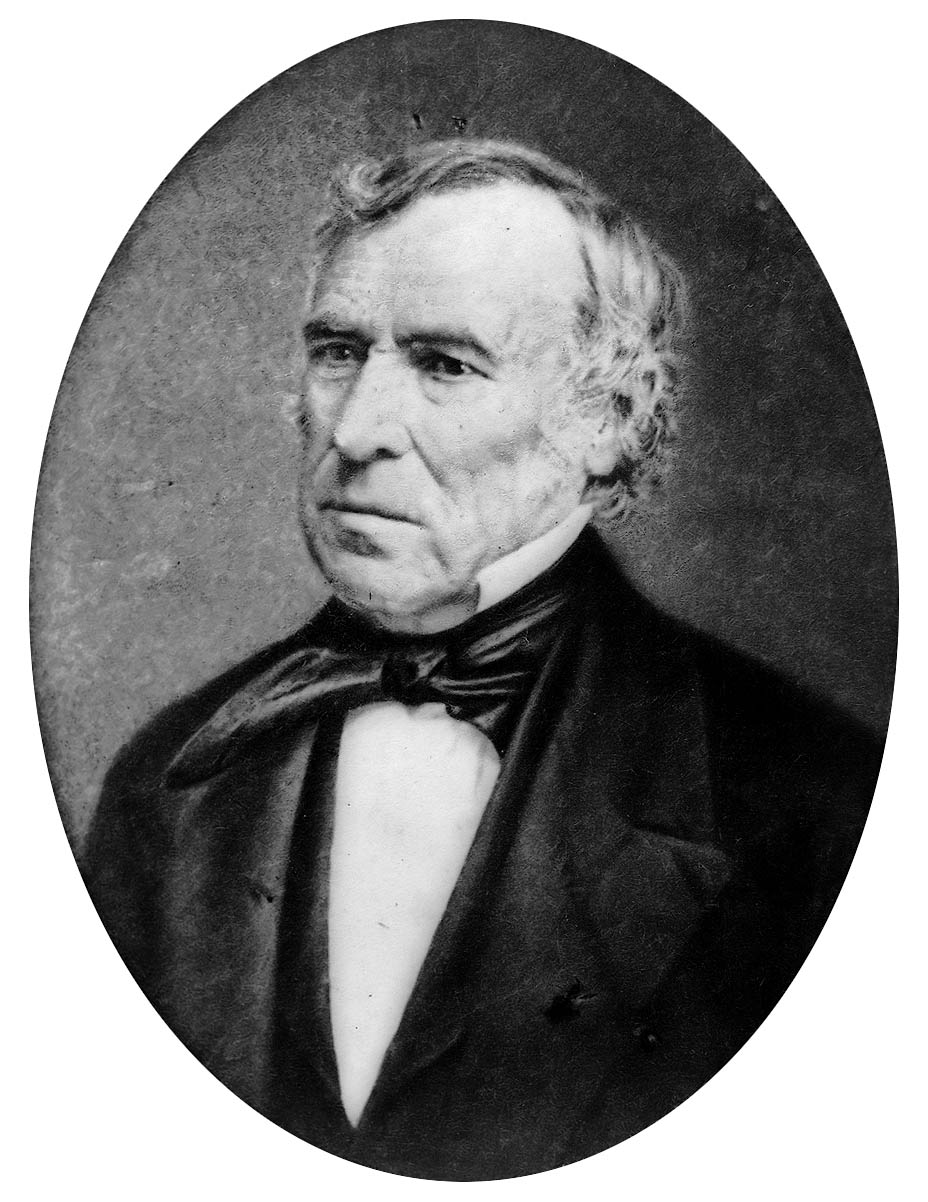

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th

Zachary Taylor was born on November 24, 1784, on a plantation in

Zachary Taylor was born on November 24, 1784, on a plantation in

File:Margaret Taylor.jpg, Margaret Smith Taylor

File:Sarah Knox Taylor.jpg, Sarah noxTaylor

File:Richard Taylor.jpg, Richard Taylor

By 1837, the Second Seminole War was underway when Taylor was directed to Florida. He built Fort Gardiner and Fort Basinger as supply depots and communication centers in support of Major General Thomas S. Jesup’s campaign to penetrate deep into Seminole territory with large forces and trap the Seminoles and their allies in order to force them to fight or surrender. He engaged in battle with the Seminole Indians in the Christmas Day Battle of Lake Okeechobee, among the largest U.S.–Indian battles of the 19th century; as a result, he was promoted to brigadier general. In May 1838, Jesup stepped down and placed Taylor in command of all American troops in Florida, a position he held for two years—his reputation as a military leader was growing and he became known as "Old Rough and Ready." Taylor was criticized for using

By 1837, the Second Seminole War was underway when Taylor was directed to Florida. He built Fort Gardiner and Fort Basinger as supply depots and communication centers in support of Major General Thomas S. Jesup’s campaign to penetrate deep into Seminole territory with large forces and trap the Seminoles and their allies in order to force them to fight or surrender. He engaged in battle with the Seminole Indians in the Christmas Day Battle of Lake Okeechobee, among the largest U.S.–Indian battles of the 19th century; as a result, he was promoted to brigadier general. In May 1838, Jesup stepped down and placed Taylor in command of all American troops in Florida, a position he held for two years—his reputation as a military leader was growing and he became known as "Old Rough and Ready." Taylor was criticized for using

When Polk's attempts to negotiate with Mexico failed, Taylor's men advanced to the Rio Grande in March 1846, and war appeared imminent. Violence broke out several weeks later, when Mexican forces attacked some of Captain Seth B. Thornton's men north of the river. Learning of the Thornton Affair, Polk told Congress in May that a war between Mexico and the U.S. had begun.

That same month, Taylor commanded American forces at the

When Polk's attempts to negotiate with Mexico failed, Taylor's men advanced to the Rio Grande in March 1846, and war appeared imminent. Violence broke out several weeks later, when Mexican forces attacked some of Captain Seth B. Thornton's men north of the river. Learning of the Thornton Affair, Polk told Congress in May that a war between Mexico and the U.S. had begun.

That same month, Taylor commanded American forces at the  Taylor remained at Monterrey until late November 1847, when he set sail for home. While he spent the following year in command of the Army's entire western division, his active military career was effectively over. In December he received a hero's welcome in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, setting the stage for the 1848 presidential election.

Ulysses S. Grant served under Taylor in this war and said of his style of leadership: "A better army, man for man, probably never faced an enemy than the one commanded by General Taylor in the earliest two engagements of the Mexican War."

Taylor remained at Monterrey until late November 1847, when he set sail for home. While he spent the following year in command of the Army's entire western division, his active military career was effectively over. In December he received a hero's welcome in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, setting the stage for the 1848 presidential election.

Ulysses S. Grant served under Taylor in this war and said of his style of leadership: "A better army, man for man, probably never faced an enemy than the one commanded by General Taylor in the earliest two engagements of the Mexican War."

In his capacity as a career officer, Taylor had never publicly revealed his political beliefs before 1848 nor voted before that time. He was

In his capacity as a career officer, Taylor had never publicly revealed his political beliefs before 1848 nor voted before that time. He was  In February 1848, Taylor again announced that he would not accept either party's presidential nomination. His reluctance to identify himself as a Whig nearly cost him the party's presidential nomination, but Senator

In February 1848, Taylor again announced that he would not accept either party's presidential nomination. His reluctance to identify himself as a Whig nearly cost him the party's presidential nomination, but Senator

As Taylor took office, Congress faced a battery of questions related to the Mexican Cession, acquired by the U.S. after the Mexican War and divided into military districts. It was unclear which districts would be established into states and which would become federal territories, while the question of their slave status threatened to bitterly divide Congress. Southerners objected to the admission of the California Territory, the New Mexico Territory, and the

As Taylor took office, Congress faced a battery of questions related to the Mexican Cession, acquired by the U.S. after the Mexican War and divided into military districts. It was unclear which districts would be established into states and which would become federal territories, while the question of their slave status threatened to bitterly divide Congress. Southerners objected to the admission of the California Territory, the New Mexico Territory, and the  The question of the New Mexico–Texas border was unsettled at the time of Taylor's inauguration. The territory newly won from Mexico was under federal jurisdiction, but the Texans claimed a swath of land north of Santa Fe and were determined to include it within their borders, despite having no significant presence there. Taylor sided with the New Mexicans' claim, initially pushing to keep it as a federal territory, but eventually supported statehood so as to further reduce the slavery debate in Congress. The Texas government, under newly instated governor P. Hansborough Bell, tried to ramp up military action in defense of the territory against the federal government, but was unsuccessful.

The Latter Day Saint settlers of modern-day Utah had established a provisional

The question of the New Mexico–Texas border was unsettled at the time of Taylor's inauguration. The territory newly won from Mexico was under federal jurisdiction, but the Texans claimed a swath of land north of Santa Fe and were determined to include it within their borders, despite having no significant presence there. Taylor sided with the New Mexicans' claim, initially pushing to keep it as a federal territory, but eventually supported statehood so as to further reduce the slavery debate in Congress. The Texas government, under newly instated governor P. Hansborough Bell, tried to ramp up military action in defense of the territory against the federal government, but was unsuccessful.

The Latter Day Saint settlers of modern-day Utah had established a provisional

Taylor and his Secretary of State, John M. Clayton, both lacked diplomatic experience and came into office at a relatively uneventful time in American–international politics. Their shared nationalism allowed Taylor to devolve foreign policy matters to Clayton with minimal oversight, although no decisive foreign policy was established under their administration. As opponents of the

Taylor and his Secretary of State, John M. Clayton, both lacked diplomatic experience and came into office at a relatively uneventful time in American–international politics. Their shared nationalism allowed Taylor to devolve foreign policy matters to Clayton with minimal oversight, although no decisive foreign policy was established under their administration. As opponents of the

Because of his short tenure, Taylor is not considered to have strongly influenced the office of the presidency or the United States. Some historians believe that he was too inexperienced with politics at a time when officials needed close ties with political operatives. Despite his shortcomings, the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty affecting relations with Great Britain in Central America is "recognized as an important step in scaling down the nation's commitment to Manifest Destiny as a policy." Although historical rankings of presidents of the United States have generally placed Taylor in the bottom quarter, most surveys tend to rank him as the most effective of the four presidents from the Whig Party.

Taylor was the last president to own slaves while in office. He was the third of four Whig presidents,This numbering includes

Because of his short tenure, Taylor is not considered to have strongly influenced the office of the presidency or the United States. Some historians believe that he was too inexperienced with politics at a time when officials needed close ties with political operatives. Despite his shortcomings, the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty affecting relations with Great Britain in Central America is "recognized as an important step in scaling down the nation's commitment to Manifest Destiny as a policy." Although historical rankings of presidents of the United States have generally placed Taylor in the bottom quarter, most surveys tend to rank him as the most effective of the four presidents from the Whig Party.

Taylor was the last president to own slaves while in office. He was the third of four Whig presidents,This numbering includes

Almost immediately after his death, rumors began to circulate that Taylor had been poisoned by pro-slavery Southerners or Catholics, and similar theories persisted into the 21st century. A few weeks after Taylor's death, Fillmore received a letter alleging that Taylor had been poisoned by a Jesuit lay official. In 1978, Hamilton Smith based his assassination theory on the timing of drugs, the lack of confirmed cholera outbreaks, and other material. summarized in Theories that Taylor had been murdered grew after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865. In 1881, John Bingham, well known for serving as the Judge Advocate General at the Lincoln assassination trial, wrote an editorial in ''

Almost immediately after his death, rumors began to circulate that Taylor had been poisoned by pro-slavery Southerners or Catholics, and similar theories persisted into the 21st century. A few weeks after Taylor's death, Fillmore received a letter alleging that Taylor had been poisoned by a Jesuit lay official. In 1978, Hamilton Smith based his assassination theory on the timing of drugs, the lack of confirmed cholera outbreaks, and other material. summarized in Theories that Taylor had been murdered grew after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865. In 1881, John Bingham, well known for serving as the Judge Advocate General at the Lincoln assassination trial, wrote an editorial in ''

online review

* Lewis, Felice Flanery. "Zachary Taylor and Monterrey: Generals as Diplomats." in ''The Routledge Handbook of American Military and Diplomatic History'' (Routledge, 2014) pp. 281–289. * * Nevins, Allan. ''Ordeal of the Union, vol. 1: Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852'' (1947), covers politics in depth

Online free to borrow

* Quist, John W. "The Election of 1848." in ''American Presidential Campaigns and Elections'' (Routledge, 2020) pp. 328–348. * *

White House biography

Zachary Taylor Presidential Papers Collection, The American Presidency Project

at the

Zachary Taylor

from the

Zachary Taylor: A Resource Guide

from the Library of Congress * *

Florida Seminole Wars Heritage Trail.

Zachary Taylor letters, 1846–1848

"Life Portrait of Zachary Taylor"

from C-SPAN's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', May 31, 1999

Zachary Taylor

a

A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War

Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington * In 1850, Anthony Philip Heinrich wrot

General Taylor's Funeral March

{{DEFAULTSORT:Taylor, Zachary 1784 births 1850 deaths 19th-century American politicians 19th-century presidents of the United States American military personnel of the Mexican–American War United States Army personnel of the War of 1812 American people of English descent American people of the Black Hawk War American people of the Seminole Wars American slave owners Burials in Kentucky Congressional Gold Medal recipients 1849 in the United States 1850 in the United States Infectious disease deaths in Washington, D.C. Kentucky Whigs Louisiana Whigs People from Barboursville, Virginia Politicians from Louisville, Kentucky People from Orange County, Virginia Presidents of the United States Southeastern Louisiana University Presidents of the United States who died while in office United States Army generals Candidates in the 1848 United States presidential election Unsolved deaths Whig Party presidents of the United States Whig Party (United States) presidential nominees

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

, rising to the rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

and becoming a national hero for his victories in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

. As a result, he won election to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

despite his vague political beliefs. His top priority as president was to preserve the Union. He died 16 months into his term from a stomach disease

Stomach diseases include gastritis, gastroparesis, Crohn's disease and various cancers.

The stomach is an important organ in the body. It plays a vital role in digestion of foods, releases various enzymes and also protects the lower intestine fr ...

, thus having the third shortest presidency in U.S. history.

Taylor was born into a prominent family of plantation owners who moved westward from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

to Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

, in his youth; he was the last president born before the adoption of the Constitution. He was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army in 1808 and made a name for himself as a captain in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

. He climbed the ranks of the military, establishing military forts along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

and entering the Black Hawk War as a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

in 1832. His success in the Second Seminole War attracted national attention and earned him the nickname "Old Rough and Ready".

In 1845, during the annexation of Texas

The Texas annexation was the 1845 annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States. Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico ...

, President James K. Polk dispatched Taylor to the Rio Grande in anticipation of a battle with Mexico over the disputed Texas–Mexico border. The Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

broke out in April 1846, and Taylor defeated Mexican troops commanded by General Mariano Arista

José Mariano Arista (26 July 1802 – 7 August 1855) was a Mexican soldier and politician.

He was in command of the Mexican forces at the opening battles of the Mexican American War: the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la P ...

at the battles of Palo Alto

Palo Alto (; Spanish for "tall stick") is a charter city in the northwestern corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

The city was es ...

and Resaca de la Palma

The Battle of Resaca de la Palma was one of the early engagements of the Mexican–American War, where the United States Army under General Zachary Taylor engaged the retreating forces of the Mexican ''Ejército del Norte'' ("Army of the North" ...

, driving Arista's troops out of Texas. Taylor then led his troops into Mexico, where they defeated Mexican troops commanded by Pedro de Ampudia at the Battle of Monterrey. Defying orders, Taylor led his troops further south and, despite being severely outnumbered, dealt a crushing blow to Mexican forces under General Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

at the Battle of Buena Vista

The Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between the US invading forces, l ...

. Taylor's troops were transferred to the command of Major General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, but Taylor retained his popularity.

The Whig Party convinced a reluctant Taylor to lead its ticket in the 1848 presidential election, despite his unclear political tenets and lack of interest in politics. At the 1848 Whig National Convention, Taylor defeated Winfield Scott and former Senator Henry Clay for the party's nomination. He won the general election alongside New York politician Millard Fillmore, defeating Democratic Party nominees Lewis Cass and William Orlando Butler, as well as a third-party effort led by former president Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

and Charles Francis Adams Sr. of the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

. Taylor became the first president to be elected without having previously held political office. As president, he kept his distance from Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

and his Cabinet, even though partisan tensions threatened to divide the Union. Debate over the status of slavery in the Mexican Cession dominated the national political agenda and led to threats of secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

from Southerners. Despite being a Southerner and a slaveholder himself, Taylor did not push for the expansion of slavery, and sought sectional harmony above all other concerns. To avoid the issue of slavery, he urged settlers in New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

and California to bypass the territorial stage and draft constitutions for statehood, setting the stage for the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

.

Taylor died suddenly of a stomach disease

Stomach diseases include gastritis, gastroparesis, Crohn's disease and various cancers.

The stomach is an important organ in the body. It plays a vital role in digestion of foods, releases various enzymes and also protects the lower intestine fr ...

on July 9, 1850, with his administration having accomplished little aside from the ratification of the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty and having made no progress on the most divisive issue in Congress and the nation: slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Vice President Fillmore assumed the presidency and served the remainder of his term. Historians and scholars have ranked Taylor in the bottom quartile of U.S. presidents, owing in part to his short term of office (16 months), though he has been described as "more a forgettable president than a failed one".

Early life

Orange County, Virginia

Orange County is a county located in the Central Piedmont region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 36,254. Its county seat is Orange. Orange County includes Montpelier, the estate of James Madison, the ...

, to a prominent family of planters of English ancestry. His birthplace may have been Hare Forest Farm, the home of his maternal grandfather William Strother, but this is uncertain. He was the third of five surviving sons in his family (a sixth died in infancy) and had three younger sisters. His mother was Sarah Dabney (Strother) Taylor. His father, Richard Taylor, served as a lieutenant colonel in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

.

Taylor was a descendant of Elder William Brewster, a Pilgrim

A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) who is on a journey to a holy place. Typically, this is a physical journey (often on foot) to some place of special significance to the adherent of ...

leader of the Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the passengers on the ...

, a '' Mayflower'' immigrant, and a signer of the Mayflower Compact; and Isaac Allerton Jr., a colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

merchant, colonel, and son of ''Mayflower'' Pilgrim Isaac Allerton

Isaac Allerton Sr. (c. 1586 – 1658/9), and his family, were passengers in 1620 on the historic voyage of the ship ''Mayflower''. Allerton was a signatory to the Mayflower Compact. In Plymouth Colony he was active in colony governmental affair ...

and Fear Brewster. Taylor's second cousin through that line was James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

, the fourth president. He was also a member of the famous Lee family of Virginia, and a third cousin once removed of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

His family forsook its exhausted Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

land, joined the westward migration and settled near future Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, on the Ohio River. Taylor grew up in a small woodland cabin until, with increased prosperity, his family moved to a brick house. As a child, he lived in a battleground of the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

, later claiming that he had seen Native Americans abduct and scalp

The scalp is the anatomical area bordered by the human face at the front, and by the neck at the sides and back.

Structure

The scalp is usually described as having five layers, which can conveniently be remembered as a mnemonic:

* S: The ski ...

his classmates while they were walking down the road together. Louisville's rapid growth was a boon for Taylor's father, who by the start of the 19th century had acquired throughout Kentucky, as well as 26 slaves to cultivate the most developed portion of his holdings. Taylor's formal education was sporadic because Kentucky's education system was just taking shape during his formative years.

Taylor's mother taught him to read and write, and he later attended a school operated by Elisha Ayer, a teacher originally from Connecticut. He also attended a Middletown, Kentucky

Middletown is an independent, home rule-class city in Jefferson County, Kentucky, United States, and a former neighborhood of Louisville. The population was 7,218 at the 2010 census.

The city is also home to the main campus of the largest ch ...

, academy run by Kean O'Hara, a classically trained scholar from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and the father of Theodore O'Hara

Theodore O'Hara (February 11, 1820 – June 6, 1867) was a poet and an officer for the United States Army in the Mexican–American War, and a Confederate colonel in the American Civil War. He is best known for the poems "Bivouac of the Dead", ...

. Ayer recalled Taylor as a patient and quick learner, but his early letters showed a weak grasp of spelling and grammar, as well as poor handwriting. All improved over time, but his handwriting remained difficult to read.

Marriage and family

In June 1810, Taylor married Margaret Mackall Smith, whom he had met the previous autumn in Louisville. "Peggy" Smith came from a prominent family ofMaryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

planters—she was the daughter of Major Walter Smith, who had served in the Revolutionary War. The couple had six children:

* Ann Mackall Taylor (1811–1875), married Robert C. Wood, a U.S. Army surgeon at Fort Snelling, in 1829. Their son John Taylor Wood

John Taylor Wood (August 13, 1830 – July 19, 1904) was an officer in the United States Navy and the Confederate Navy. He resigned from the U.S. Navy at the beginning of the American Civil War, and became a "leading Confederate naval hero" ...

served in the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

and the Confederate Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American ...

. President Taylor's two great-grandsons were:

** Zachary Taylor Wood, acting Commissioner of the North-West Mounted Police and Commissioner of Yukon Territory.

** Charles Carroll Wood, Lieutenant with the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

.

* Sarah Knox "Knoxie" Taylor (1814–1835), married Jefferson Davis in 1835, a subordinate officer she had met through her father at the end of the Black Hawk War; she died at 21 of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

in St. Francisville, Louisiana, three months after her marriage.

* Octavia Pannell Taylor (1816–1820), died in early childhood.

* Margaret Smith Taylor (1819–1820), died in infancy along with Octavia when the Taylor family was stricken with a "bilious fever."

* Mary Elizabeth "Betty" Taylor (1824–1909), married William Wallace Smith Bliss

William Wallace Smith Bliss (August 17, 1815 – August 5, 1853) was a United States Army officer and mathematics professor. A gifted mathematician, he taught at West Point and also served as a line officer.

In December 1848 Bliss married M ...

in 1848 (he died in 1853); married Philip Pendleton Dandridge in 1858.

* Richard Taylor (1826–1879), a Confederate Army general; married Louise Marie Myrthe Bringier in 1851.

Military career

Initial commissions

On May 3, 1808, Taylor joined the U.S. Army, receiving a commission from PresidentThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

as a first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

of the Kentuckian Seventh Infantry Regiment. He was among the new officers Congress commissioned in response to the ''Chesapeake–Leopard'' affair, in which the crew of a British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

warship had boarded a United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

frigate, sparking calls for war. Taylor spent much of 1809 in the dilapidated camps of and nearby Terre aux Boeufs, in the Territory of Orleans. Under James Wilkinson's command, the soldiers at Terre aux Boeufs suffered greatly from disease and lack of supplies, and Taylor was given an extended leave, returning to Louisville to recover.

Taylor was promoted to captain in November 1810. His army duties were limited at this time, and he attended to his personal finances. Over the next several years, he began to purchase a good deal of bank stock in Louisville. He also bought a plantation in Louisville, as well as the Cypress Grove Plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi Territory. These acquisitions included slaves, rising in number to more than 200.ANTI-SLAVERY REPORTER VOL III, NO XXXVI, December 1, 1848, p 194-5

In July 1811 he was called to the Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a congressional act that President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, ...

, where he assumed control of Fort Knox after the commandant fled. In a few weeks, he was able to restore order in the garrison, for which he was lauded by Governor William Henry Harrison. Taylor was temporarily called to Washington to testify for Wilkinson as a witness in a court-martial, and so did not take part in the November 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe

The Battle of Tippecanoe ( ) was fought on November 7, 1811, in Battle Ground, Indiana, between American forces led by then Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory and Native American forces associated with Shawnee leader Tecum ...

against the forces of Tecumseh, a Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

chief.

War of 1812

During theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, in which U.S. forces battled the British Empire and its Indian allies, Taylor defended Fort Harrison in Indiana Territory from an Indian attack commanded by Tecumseh. The September 1812 battle was the American forces' first land victory of the war, for which Taylor received wide praise, as well as a brevet (temporary) promotion to the rank of major. According to historian John Eisenhower

John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower (August 3, 1922 – December 21, 2013) was a United States Army officer, diplomat, and military historian. He was a son of President Dwight D. Eisenhower and First Lady Mamie Eisenhower. His military career sp ...

, this was the first brevet awarded in U.S. history. Later that year, Taylor joined General Samuel Hopkins as an aide on two expeditions—one into the Illinois Territory and one to the Tippecanoe battle site, where they were forced to retreat in the Battle of Wild Cat Creek. Taylor moved his growing family to Fort Knox after the violence subsided.

In the spring of 1814, Taylor was called back into action under Brigadier General Benjamin Howard, and after Howard fell sick, Taylor led a 430-man expedition from St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, up the Mississippi River. In the Battle of Credit Island, Taylor defeated Indian forces, but retreated after the Indians were joined by their British allies. That October he supervised the construction of Fort Johnson near present-day Warsaw, Illinois, the last toehold of the U.S. Army in the upper Mississippi River Valley. Upon Howard's death a few weeks later, Taylor was ordered to abandon the fort and retreat to St. Louis. Reduced to the rank of captain when the war ended in 1815, he resigned from the army. He reentered it a year later after gaining a commission as a major.

Command of Fort Howard

Taylor commanded Fort Howard at the Green Bay, Michigan Territory settlement for two years, then returned to Louisville and his family. In April 1819 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and dined with PresidentJames Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

and General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

. In late 1820, Taylor took the 7th Infantry to Natchitoches, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, on the Red River. He subsequently established Fort Selden at the confluence of the Sulphur River and the Red River. On the orders of General Edmund P. Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (March 20, 1777 – June 6, 1849) was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its format ...

, he later found a new post more convenient to the Sabine River frontier. By March 1822, Taylor had established Fort Jesup

Fort Jesup, also known as Fort Jesup State Historic Site or Fort Jesup or Fort Jesup State Monument, was built in 1822, west of Natchitoches, Louisiana, to protect the United States border with New Spain and to return order to the Neutral Strip. ...

at the Shield's Spring site southwest of Natchitoches.

That November (1822), Taylor was transferred to Baton Rouge on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, where he remained until February 1824. He spent the next few years on recruiting duty. In late 1826, he was called to Washington, D.C., for work on an Army committee to consolidate and improve military organization. In the meantime he acquired his first Louisiana plantation and decided to move with his family to a new home in Baton Rouge.

Black Hawk War

In May 1828, Taylor was called back to action, commanding Fort Snelling in Michigan Territory (now Minnesota) on the Upper Mississippi River for a year, and then nearbyFort Crawford

Fort Crawford was an outpost of the United States Army located in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, during the 19th century.

The army's occupation of Prairie du Chien spanned the existence of two fortifications, both of them named Fort Crawford. The ...

for a year. After some time on furlough, spent expanding his landholdings, Taylor was promoted to colonel of the 1st Infantry Regiment in April 1832, when the Black Hawk War was beginning in the West. Taylor campaigned under General Henry Atkinson to pursue and later defend against Chief Black Hawk's forces throughout the summer. The end of the war in August 1832 signaled the final Indian resistance to U.S. expansion in the area.

During this period Taylor opposed the courtship of his 17-year-old daughter Sarah Knox Taylor with Lieutenant Jefferson Davis, the future President of the Confederate States of America

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Conf ...

. He respected Davis but did not wish his daughter to become a military wife, as he knew it was a hard life for families. Davis and Sarah Taylor married in June 1835 (when she was 21), but she died three months later of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

contracted on a visit to Davis's sister's home in St. Francisville, Louisiana.

Second Seminole War

bloodhound

The bloodhound is a large scent hound, originally bred for hunting deer, wild boar and, since the Middle Ages, for tracking people. Believed to be descended from hounds once kept at the Abbey of Saint-Hubert, Belgium, in French it is called, ...

s in order to track Seminole.

After his long-requested relief was granted, Taylor spent a comfortable year touring the nation with his family and meeting with military leaders. During this period, he began to be interested in politics and corresponded with President William Henry Harrison. He was made commander of the Second Department of the Army's Western Division in May 1841. The sizable territory ran from the Mississippi River westward, south of the 37th parallel north. Stationed in Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

, Taylor enjoyed several uneventful years, spending as much time attending to his land speculation as to military matters.

Mexican–American War

In anticipation of the annexation of the Republic of Texas, which had established independence in 1836, Taylor was sent in April 1844 toFort Jesup

Fort Jesup, also known as Fort Jesup State Historic Site or Fort Jesup or Fort Jesup State Monument, was built in 1822, west of Natchitoches, Louisiana, to protect the United States border with New Spain and to return order to the Neutral Strip. ...

in Louisiana, and ordered to guard against attempts by Mexico to reclaim the territory. More senior generals in the army might have taken this important command, such as Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

and Edmund P. Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (March 20, 1777 – June 6, 1849) was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its format ...

. But both were known members of the Whig Party, and Taylor's apolitical reputation and friendly relations with Andrew Jackson made him the choice of President James K. Polk. Polk directed him to deploy into disputed territory in Texas, "on or near the Rio Grande" near Mexico. Taylor chose a spot at Corpus Christi, and his Army of Occupation encamped there until the following spring in anticipation of a Mexican attack.

Battle of Palo Alto

The Battle of Palo Alto ( es, Batalla de Palo Alto) was the first major battle of the Mexican–American War and was fought on May 8, 1846, on disputed ground five miles (8 km) from the modern-day city of Brownsville, Texas. A force of so ...

and the nearby Battle of Resaca de la Palma. Though greatly outnumbered, he defeated the Mexican "Army of the North

The Army of the North ( es, link=no, Ejército del Norte), contemporaneously called Army of Peru, was one of the armies deployed by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in the Spanish American wars of independence. Its objective was fre ...

" commanded by General Mariano Arista

José Mariano Arista (26 July 1802 – 7 August 1855) was a Mexican soldier and politician.

He was in command of the Mexican forces at the opening battles of the Mexican American War: the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la P ...

, and forced the troops back across the Rio Grande. Taylor was later praised for his humane treatment of the wounded Mexican soldiers before the prisoner exchange with Arista, giving them the same care as was given to American wounded. After tending to the wounded, he performed the last rites for the dead of both the American and Mexican soldiers killed during the battle.

These victories made him a popular hero, and in May 1846 Taylor received a brevet promotion to major general and a formal commendation from Congress. In June, he was promoted to the full rank of major general. The national press compared him to George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and Andrew Jackson, both generals who had ascended to the presidency, but Taylor denied any interest in running for office. "Such an idea never entered my head," he remarked in a letter, "nor is it likely to enter the head of any sane person."

After crossing the Rio Grande, in September Taylor inflicted heavy casualties upon the Mexicans at the Battle of Monterrey, and captured that city in three days, despite its impregnable repute. Taylor was criticized for signing a "liberal" truce rather than pressing for a large-scale surrender. Polk had hoped that the occupation of Northern Mexico

Northern Mexico ( es, el Norte de México ), commonly referred as , is an informal term for the northern cultural and geographical area in Mexico. Depending on the source, it contains some or all of the states of Baja California, Baja California ...

would induce the Mexicans to sell Alta California and New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

, but the Mexicans remained unwilling to part with so much territory. Polk sent an army under the command of Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

to besiege Veracruz, an important Mexican port city, while Taylor was ordered to remain near Monterrey. Many of Taylor's experienced soldiers were placed under Scott's command, leaving Taylor with a smaller and less effective force. Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

intercepted a letter from Scott about Taylor's smaller force, and he moved north, intent on destroying Taylor's force before confronting Scott's army.

Learning of Santa Anna's approach, and refusing to retreat despite the Mexican army's greater numbers, Taylor established a strong defensive position near the town of Saltillo. Santa Anna attacked Taylor with 20,000 men at the Battle of Buena Vista

The Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between the US invading forces, l ...

in February 1847, leaving around 700 Americans dead or wounded at a cost of over 1,500 Mexican casualties. Outmatched, the Mexican forces retreated, ensuring a "far-reaching" victory for the Americans.

In recognition of his victory at Buena Vista, on July 4, 1847, Taylor was elected an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati, the Virginia branch of which included his father as a charter member. Taylor also was made a member of the Aztec Club of 1847, Military Society of the Mexican War. He received three Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is Congress's highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The congressional pract ...

s for his service in the Mexican-American War and remains the only person to have received the medal three times.

Taylor remained at Monterrey until late November 1847, when he set sail for home. While he spent the following year in command of the Army's entire western division, his active military career was effectively over. In December he received a hero's welcome in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, setting the stage for the 1848 presidential election.

Ulysses S. Grant served under Taylor in this war and said of his style of leadership: "A better army, man for man, probably never faced an enemy than the one commanded by General Taylor in the earliest two engagements of the Mexican War."

Taylor remained at Monterrey until late November 1847, when he set sail for home. While he spent the following year in command of the Army's entire western division, his active military career was effectively over. In December he received a hero's welcome in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, setting the stage for the 1848 presidential election.

Ulysses S. Grant served under Taylor in this war and said of his style of leadership: "A better army, man for man, probably never faced an enemy than the one commanded by General Taylor in the earliest two engagements of the Mexican War."

Election of 1848

In his capacity as a career officer, Taylor had never publicly revealed his political beliefs before 1848 nor voted before that time. He was

In his capacity as a career officer, Taylor had never publicly revealed his political beliefs before 1848 nor voted before that time. He was apolitical

Apoliticism is apathy or antipathy towards all political affiliations. A person may be described as apolitical if they are uninterested or uninvolved in politics. Being apolitical can also refer to situations in which people take an unbiased po ...

and had a negative opinion of most politicians. He thought of himself as an independent, believing in a strong and sound banking system for the country, and thought that President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

should not have allowed the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

to collapse in 1836. He believed it was impractical to expand slavery into the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the We ...

, as neither cotton nor sugar (both produced in great quantities as a result of slavery) could be easily grown there through a plantation economy

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash ...

. He was also a firm American nationalist

American nationalism, is a form of civic, ethnic, cultural or economic influences

*

*

*

*

*

*

* found in the United States. Essentially, it indicates the aspects that characterize and distinguish the United States as an autonomous political co ...

, and due to his experience of seeing many people die as a result of warfare, believed that secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

was a bad way to resolve national problems.

Well before the American victory at Buena Vista, political clubs formed that supported Taylor for president. His support was drawn from an unusually broad assortment of political bands, including Whigs and Democrats, Northerners and Southerners, allies and opponents of national leaders such as Polk and Henry Clay. By late 1846, Taylor's opposition to a presidential run had weakened, and it became clear that his principles resembled Whig orthodoxy. Taylor despised both Polk and his policies, while the Whigs were considering nominating another war hero for the presidency after the success of its previous winning nominee, William Henry Harrison, in 1840.

As support for Taylor's candidacy grew, he continued to keep his distance from both parties, but made clear that he would have voted for Whig Henry Clay in 1844 had he voted. In a widely publicized September 1847 letter, Taylor stated his positions on several issues. He did not favor chartering another national bank, favored a low tariff, and believed that the president should play no role in making laws. Taylor did believe that the president could veto laws, but only when they were clearly unconstitutional.

Many southerners believed that Taylor supported slavery and its expansion into the new territory absorbed from Mexico, and some were angered when Taylor suggested that if elected president he would not veto the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, which proposed against such an expansion. This position did not enhance his support from activist antislavery elements in the Northern United States, as they wanted Taylor to speak out strongly in support of the Proviso, not simply fail to veto it. Most abolitionists did not support Taylor, since he was a slave-owner.

John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as Unite ...

of Kentucky and other supporters finally convinced Taylor to declare himself a Whig. Though Clay retained a strong following among the Whigs, Whig leaders like William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

were eager to support a war hero who could replicate the success of the party's only other successful presidential candidate, William Henry Harrison.

At the 1848 Whig National Convention, Taylor defeated Clay and Winfield Scott for the presidential nomination. For its vice-presidential nominee the convention chose Millard Fillmore, a prominent New York Whig who had chaired the House Ways and Means Committee

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other progra ...

and been a contender for the vice-presidential nominee in the 1844 election. Fillmore's selection was largely an attempt at reconciliation with northern Whigs, who were furious at the nomination of a slave-owning southerner; no faction of the party was satisfied with the final ticket. It was initially unclear whether Taylor would accept the nomination because he did not respond to the letters notifying him of the convention's outcome, because he had instructed his local post office not to deliver his mail to avoid postage fees. Taylor continued to minimize his role in the campaign, preferring not to directly meet with voters or correspond about his political views. He did little active campaigning, and may not have voted. His campaign was skillfully directed by Crittenden and bolstered by a late endorsement from Senator Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

of Massachusetts.

Democrats were even less unified than the Whigs, as former Democratic President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

broke from the party and led the anti-slavery Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

's ticket. Van Buren won the support of many Democrats and Whigs who opposed the extension of slavery into the territories, but he took more votes from Democratic nominee Lewis Cass in the crucial state of New York.

Nationally, Taylor defeated Cass and Van Buren, taking 163 of the 290 electoral votes. In the popular vote, he took 47.3%, to Cass's 42.5% and Van Buren's 10.1%. Taylor was the last Whig to be elected president and the last person elected to the presidency from neither the Democratic Party nor the Republican Party, as well as the last Southerner to win a presidential election until Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's election in 1912.Taylor was not the last Whig to serve as president, nor was he the last Southerner to serve as president prior to Woodrow Wilson. Taylor was succeeded in office by Fillmore, who was also a member of the Whig Party. Andrew Johnson, a Southerner, served as president from 1865 to 1869. However, neither Fillmore nor Johnson were directly elected to the presidency.

Taylor ignored the Whig platform, as historian Michael F. Holt explains:

Presidency (1849–1850)

Transition

As president-elect, Taylor kept his distance from Washington, not resigning his Western Division command until late January 1849. He spent the months following the election formulating his cabinet selections. He was deliberate and quiet about his decisions, to the frustration of his fellow Whigs. While he despised patronage and political games, he endured a flurry of advances from office-seekers looking to play a role in his administration. While he would appoint no Democrats, Taylor wanted his cabinet to reflect the nation's diverse interests, and so apportioned the seats geographically. He also avoided choosing prominent Whigs, sidestepping such obvious selections as Clay. He saw Crittenden as a cornerstone of his administration, offering him the crucial seat of Secretary of State, but Crittenden insisted on serving out the governorship of Kentucky to which he had just been elected. Taylor settled on Senator John M. Clayton of Delaware, a close associate of Crittenden's. With Clayton's aid, Taylor chose the six remaining members of his cabinet. One of the incoming Congress's first actions would be to establish the Department of the Interior, so Taylor would be appointing that department's inaugural secretary.Thomas Ewing

Thomas Ewing Sr. (December 28, 1789October 26, 1871) was a National Republican and Whig politician from Ohio. He served in the U.S. Senate as well as serving as the secretary of the treasury and the first secretary of the interior. He is als ...

, who had previously served as a senator from Ohio and as Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

under William Henry Harrison, accepted the patronage-rich position of Secretary of the Interior. For the position of Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

, also a center of patronage, Taylor chose Congressman Jacob Collamer of Vermont.

After Horace Binney refused appointment as Secretary of the Treasury, Taylor chose another prominent Philadelphian, William M. Meredith. George W. Crawford, a former governor of Georgia, accepted the position of Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, while Congressman William B. Preston

William Ballard Preston (November 25, 1805 – November 16, 1862) was an American politician who served as a Confederate States Senator from Virginia from February 18, 1862, until his death in November. He previously served as the 19th United S ...

of Virginia became Secretary of the Navy. Senator Reverdy Johnson

Reverdy Johnson (May 21, 1796February 10, 1876) was a statesman and jurist from Maryland. He gained fame as a defense attorney, defending notables such as Sandford of the Dred Scott case, Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter at his court-martial, and Mary ...

of Maryland accepted appointment as Attorney General, and became one of the most influential members of Taylor's cabinet. Fillmore was not in favor with Taylor, and was largely sidelined throughout Taylor's presidency.

Taylor began his trek to Washington in late January, a journey rife with bad weather, delays, injuries, sickness—and an abduction by a family friend. Taylor finally arrived in the nation's capital on February 24 and soon met with the outgoing President Polk. Polk held a low opinion of Taylor, privately deeming him "without political information" and "wholly unqualified for the station" of president. Taylor spent the next week meeting with political elites, some of whom were unimpressed with his appearance and demeanor. With less than two weeks until his inauguration, he met with Clayton and hastily finalized his cabinet.

Inauguration

Taylor's term as president began on Sunday, March 4, but his inauguration was not held until the next day out of religious concerns. His inauguration speech discussed the many tasks facing the nation, but presented a governing style of deference to Congress and sectional compromise instead of assertive executive action. His speech also emphasized the importance of following President Washington's precedent in avoiding entangling alliances. During the period after his inauguration, Taylor made time to meet with numerous office-seekers and other ordinary citizens who desired his attention. He also attended an unusual number of funerals, including services for Polk andDolley Madison

Dolley Todd Madison (née Payne; May 20, 1768 – July 12, 1849) was the wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. She was noted for holding Washington social functions in which she invited members of bo ...

. According to Eisenhower, Taylor coined the phrase " First Lady" in his eulogy for Madison. In the summer of 1849, Taylor toured the Northeastern United States to familiarize himself with a region of which he had seen little. He spent much of the trip plagued by gastrointestinal illness and returned to Washington by September.

Sectional crisis

As Taylor took office, Congress faced a battery of questions related to the Mexican Cession, acquired by the U.S. after the Mexican War and divided into military districts. It was unclear which districts would be established into states and which would become federal territories, while the question of their slave status threatened to bitterly divide Congress. Southerners objected to the admission of the California Territory, the New Mexico Territory, and the

As Taylor took office, Congress faced a battery of questions related to the Mexican Cession, acquired by the U.S. after the Mexican War and divided into military districts. It was unclear which districts would be established into states and which would become federal territories, while the question of their slave status threatened to bitterly divide Congress. Southerners objected to the admission of the California Territory, the New Mexico Territory, and the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

to the Union as free states despite California's demographic and economic growth. Additionally, Southerners had grown increasingly angry about the aid that Northerners had given to fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

after ''Prigg v. Pennsylvania

''Prigg v. Pennsylvania'', 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 539 (1842), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court held that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 precluded a Pennsylvania state law that prohibited blacks from being taken out of the free s ...

'' allowed slave catchers to capture alleged runaway slaves in free states, and that Northern authorities frequently refused to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the US Constitution ( Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which was later superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment, and to also gi ...

. At the same time, northerners demanded the abolition of the domestic slave trade

The domestic slave trade, also known as the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the term for the domestic trade of enslaved people within the United States that reallocated slaves across states during the Antebellum perio ...

in Washington DC. Finally, Texas claimed parts of eastern New Mexico and threatened to send its state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

to militarily enforce its territorial claims.

While a Southern slaveowner himself, Taylor believed that slavery was economically infeasible in the Mexican Cession, and so opposed slavery in those territories as a needless source of controversy. His major goal was sectional peace, preserving the Union through legislative compromise. As the threat of Southern secession grew, he sided increasingly with antislavery Northerners such as Senator William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

of New York, even suggesting that he would sign the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

to ban slavery in federal territories should such a bill reach his desk.

In Taylor's view, the best way forward was to admit California as a state rather than a federal territory, as it would leave the slavery question out of Congress's hands. The timing for statehood was in Taylor's favor, as the California Gold Rush was well underway at the time of his inauguration, and California's population was exploding. The administration dispatched Representative Thomas Butler King to California, to test the waters and advocate statehood, knowing that Californians were certain to adopt an anti-slavery constitution. King found that a constitutional convention was already underway, and by October 1849, the convention unanimously agreed to join the Union—and to ban slavery within their borders.

The question of the New Mexico–Texas border was unsettled at the time of Taylor's inauguration. The territory newly won from Mexico was under federal jurisdiction, but the Texans claimed a swath of land north of Santa Fe and were determined to include it within their borders, despite having no significant presence there. Taylor sided with the New Mexicans' claim, initially pushing to keep it as a federal territory, but eventually supported statehood so as to further reduce the slavery debate in Congress. The Texas government, under newly instated governor P. Hansborough Bell, tried to ramp up military action in defense of the territory against the federal government, but was unsuccessful.

The Latter Day Saint settlers of modern-day Utah had established a provisional

The question of the New Mexico–Texas border was unsettled at the time of Taylor's inauguration. The territory newly won from Mexico was under federal jurisdiction, but the Texans claimed a swath of land north of Santa Fe and were determined to include it within their borders, despite having no significant presence there. Taylor sided with the New Mexicans' claim, initially pushing to keep it as a federal territory, but eventually supported statehood so as to further reduce the slavery debate in Congress. The Texas government, under newly instated governor P. Hansborough Bell, tried to ramp up military action in defense of the territory against the federal government, but was unsuccessful.

The Latter Day Saint settlers of modern-day Utah had established a provisional State of Deseret

The State of Deseret (modern pronunciation , contemporaneously ) was a proposed state of the United States, proposed in 1849 by settlers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in Salt Lake City. The provisional stat ...

, an enormous swath of territory that had little hope of recognition by Congress. The Taylor administration considered combining the California and Utah territories but instead opted to organize the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

. To alleviate the Mormon population's concerns over religious freedom, Taylor promised they would have relative independence from Congress despite being a federal territory.

Taylor sent his only State of the Union report to Congress in December 1849. He recapped international events and suggested several adjustments to tariff policy and executive organization, but the sectional crisis facing Congress overshadowed such issues. He reported on California's and New Mexico's applications for statehood, and recommended that Congress approve them as written and "should abstain from the introduction of those exciting topics of a sectional character". The policy report was prosaic and unemotional, but ended with a sharp condemnation of secessionists. It had no effect on Southern legislators, who saw the admission of two free states as an existential threat, and Congress remained stalled.

Foreign affairs

Taylor and his Secretary of State, John M. Clayton, both lacked diplomatic experience and came into office at a relatively uneventful time in American–international politics. Their shared nationalism allowed Taylor to devolve foreign policy matters to Clayton with minimal oversight, although no decisive foreign policy was established under their administration. As opponents of the

Taylor and his Secretary of State, John M. Clayton, both lacked diplomatic experience and came into office at a relatively uneventful time in American–international politics. Their shared nationalism allowed Taylor to devolve foreign policy matters to Clayton with minimal oversight, although no decisive foreign policy was established under their administration. As opponents of the autocratic

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except per ...

European order, they vocally supported German and Hungarian liberals in the revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, although they offered little in the way of aid.

A perceived insult from the French minister Guillaume Tell Poussin nearly led to a break in diplomatic relations until Poussin was replaced, and a reparation dispute with Portugal resulted in harsh words from the Taylor administration. In a more positive effort, the administration arranged for two ships to assist in the United Kingdom's search for a team of British explorers, led by John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through t ...

, who had gotten lost in the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, N ...