Xerxes I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the fourth

According to the Greek dialogue First Alcibiades, which describes typical upbringing and education of Persian princes, they were raised by

According to the Greek dialogue First Alcibiades, which describes typical upbringing and education of Persian princes, they were raised by

Darius died while in the process of preparing a second army to invade the Greek mainland, leaving to his son the task of punishing the

Darius died while in the process of preparing a second army to invade the Greek mainland, leaving to his son the task of punishing the

At the

At the

VIII, 97

/ref> Another cause of the retreat might have been that the continued unrest in

By queen Amestris:

* Darius, the first born son, murdered by

By queen Amestris:

* Darius, the first born son, murdered by

Later generations' fascination with ancient Sparta, particularly the

Later generations' fascination with ancient Sparta, particularly the

King of Kings

King of Kings, ''Mepet mepe''; , group="n" was a ruling title employed primarily by monarchs based in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. Commonly associated with History of Iran, Iran (historically known as name of Iran, Persia ...

of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was the son of Darius the Great

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

and Atossa

Atossa (Old Persian: ''Utauθa'', or Old Iranian: ''Hutauθa''; 550–475 BC) was an Achaemenid empress. She was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the sister of Cambyses II, the wife of Darius the Great, the mother of Xerxes the Great and the gr ...

, a daughter of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

.

In Western history, Xerxes is best known for his invasion of Greece in 480 BC, which ended in Persian defeat. Xerxes was designated successor by Darius over his elder brother Artobazan and inherited a large, multi-ethnic empire upon his father's death. He consolidated his power by crushing revolts in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

, and renewed his father's campaign to subjugate Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and punish Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and its allies for their interference in the Ionian Revolt. In 480 BC, Xerxes personally led a large army and crossed the Hellespont

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey t ...

into Europe. He achieved victories at Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

and Artemisium before capturing and razing Athens. His forces gained control of mainland Greece north of the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

until their defeat at the Battle of Salamis. Fearing that the Greeks might trap him in Europe, Xerxes retreated with the greater part of his army back to Asia, leaving behind Mardonius to continue his campaign. Mardonius was defeated at Plataea

Plataea (; , ''Plátaia'') was an ancient Greek city-state situated in Boeotia near the frontier with Attica at the foot of Mt. Cithaeron, between the mountain and the river Asopus, which divided its territory from that of Thebes. Its inhab ...

the following year, effectively ending the Persian invasion.

After returning to Persia, Xerxes dedicated himself to large-scale construction projects, many of which had been left unfinished by his father. He oversaw the completion of the Gate of All Nations

The Gate of All Nations ( ), also known as the Gate of Xerxes, is located in the ruins of the ancient city of Persepolis, Iran.

The construction of the Stairs of All Nations and the Gate of All Nations was ordered by the Achaemenid king Xerxes I ...

, the Apadana

Apadana (, or ) is a large hypostyle hall in Persepolis, Iran. It belongs to the oldest building phase of the city of Persepolis, in the first half of the 5th century BC, as part of the original design by Darius I, Darius the Great. Its cons ...

and the Tachara at Persepolis

Persepolis (; ; ) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by the southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian cultural heritage sites and ...

, and continued the construction of the Palace of Darius at Susa

Susa ( ) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh River, Karkheh and Dez River, Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital o ...

. He also maintained the Royal Road built by his father. In 465 BC, Xerxes and his heir Darius were assassinated by Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard. He was succeeded by his third son, who took the throne as Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, ; ) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "Long-handed" ( ''Makrókheir''; ), allegedly because his ri ...

.

Etymology

''Xérxēs'' () is theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

(''Xerxes'', ''Xerses'') transliteration of the Old Iranian

The Iranian languages, also called the Iranic languages, are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European language family that are spoken natively by the Iranian peoples, predominantly in the Iranian Plateau.

The Iranian language ...

''Xšaya-ṛšā'' ("ruling over heroes"), which can be seen by the first part ''xšaya'', meaning "ruling", and the second ''ṛšā'', meaning "hero, man".; The name of Xerxes was known in Akkadian as ''Ḫi-ši-ʾ-ar-šá'' and in Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

as ''ḥšyʾrš''. Xerxes would become a popular name among the rulers of the Achaemenid Empire.

Early life

Parentage and birth

Xerxes' father wasDarius the Great

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

(), the incumbent monarch of the Achaemenid Empire, albeit himself not a member of the family of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

, the founder of the empire. Xerxes' mother was Atossa

Atossa (Old Persian: ''Utauθa'', or Old Iranian: ''Hutauθa''; 550–475 BC) was an Achaemenid empress. She was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the sister of Cambyses II, the wife of Darius the Great, the mother of Xerxes the Great and the gr ...

, a daughter of Cyrus. Darius and Atossa married in 522 BC, and Xerxes was born around 518 BC.

Upbringing and education

According to the Greek dialogue First Alcibiades, which describes typical upbringing and education of Persian princes, they were raised by

According to the Greek dialogue First Alcibiades, which describes typical upbringing and education of Persian princes, they were raised by eunuchs

A eunuch ( , ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function. The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2 ...

. Starting at the age of seven, they learned how to ride and hunt; after reaching the age of fourteen, they were each taught by four teachers from aristocratic backgrounds, who taught them how to be "wise, just, prudent, and brave." Persian princes also learned the basics of the Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, Zoroaster ( ). Among the wo ...

religion, and were taught to be truthful, to be courageous, and to have self-restraint. The dialogue further added that "fear, for a Persian, is the equivalent of slavery." At the age of 16 or 17, they began their mandatory 10 years of national service, which included practicing archery and javelin, competing for prizes, and hunting. Afterwards, they served in the military for around 25 years, after which they were elevated to the status of elders and advisers to the king. Families in this time, including Xerxes', would intermarry.

This account of education among the Persian elite is supported by Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

's description of the 5th-century BC Achaemenid prince Cyrus the Younger

Cyrus the Younger ( ''Kūruš''; ; died 401 BC) was an Achaemenid prince and general. He ruled as satrap of Lydia and Ionia from 408 to 401 BC. Son of Darius II and Parysatis, he died in 401 BC in battle during a failed attempt to oust his ...

, with whom he was well-acquainted. Stoneman suggests that this was the type of upbringing and education that Xerxes experienced. It is unknown if Xerxes ever learned to read or write, with the Persians favoring oral history over written literature. Stoneman suggests that Xerxes' upbringing and education was possibly not much different from that of the later Iranian kings, such as Abbas the Great

Abbas I (; 27 January 1571 – 19 January 1629), commonly known as Abbas the Great (), was the fifth Safavid Iran, Safavid shah of Iran from 1588 to 1629. The third son of Mohammad Khodabanda, Shah Mohammad Khodabanda, he is generally considered ...

, king of the Safavid Empire

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the begi ...

in the 17th-century AD. Starting from 498 BC, Xerxes resided in the royal palace of Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

.

Accession to the throne

While Darius was preparing for another war against Greece, a revolt began in Egypt in 486 BC due to heavy taxes and the deportation of craftsmen to build the royal palaces at Susa and Persepolis. The king was required by Persian law to choose a successor before setting out on dangerous expeditions; when Darius decided to leave for Egypt (487–486 BC), he prepared his tomb atNaqsh-e Rustam

Naqsh-e Rostam (; , ) is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 13 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into the face of the mountain and the mountain ...

(five kilometers from his royal palace at Persepolis) and appointed Xerxes, his eldest son by Atossa

Atossa (Old Persian: ''Utauθa'', or Old Iranian: ''Hutauθa''; 550–475 BC) was an Achaemenid empress. She was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the sister of Cambyses II, the wife of Darius the Great, the mother of Xerxes the Great and the gr ...

, as his successor. However, Darius could not lead the campaign due to his failing health; he died in October 486 BC at the age of 64.

Artobazan claimed that he should take the crown as the eldest of all Darius' children, while Xerxes argued for his own claim on the grounds that he was the son of Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus, and that Cyrus had won the Persians their freedom. Xerxes' claim was supported by a Spartan king in exile who was present in Persia at the time, the Eurypontid king Demaratus, who also argued that the eldest son did not universally have the best claim to the crown, citing Spartan law, which stated that the first son born while the father is king was the heir to the kingship. Some modern scholars also view the unusual decision of Darius to give the throne to Xerxes as a result of his consideration of the particular prestige that Cyrus the Great and his daughter Atossa enjoyed. Artobazan was born to "Darius the subject", while Xerxes was the eldest son " born in the purple" after Darius' rise to the throne. Furthermore, while Artobazan's mother was a commoner, Xerxes' mother was the daughter of the founder of the Achaemenid Empire.

Xerxes was crowned and succeeded his father in October–December 486 BC ''The Cambridge History of Iran'' vol. 2. p. 509. when he was about 32 years old. The transition of power to Xerxes was smooth, due again in part to the great authority of AtossaSchmitt, R. "Atossa

Atossa (Old Persian: ''Utauθa'', or Old Iranian: ''Hutauθa''; 550–475 BC) was an Achaemenid empress. She was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the sister of Cambyses II, the wife of Darius the Great, the mother of Xerxes the Great and the gr ...

". In ''Encyclopaedia Iranica

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles or entries that are arranged alphabetically by artic ...

''. and his accession to royal power was not challenged by any person at court or in the Achaemenian family, or by any subject nation.

Consolidation of power

At the time of Xerxes' accession, trouble was brewing in some of his domains. A revolt occurred inEgypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, which seemed dangerous enough for Xerxes to personally lead the army to restore order (which also gave him the opportunity to begin his reign with a military campaign). Xerxes suppressed the revolt in January 484 BC and appointed his full-brother Achaemenes as satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

of Egypt, replacing the previous satrap Pherendates, who was reportedly killed during the revolt. The suppression of the Egyptian revolt expended the army, which had been mobilized by Darius over the previous three years. Xerxes, therefore, had to raise another army for his expedition into Greece, which took another four years. There was also unrest in Babylon, which revolted at least twice against Xerxes during his reign. The first revolt broke out in June or July of 484 BC and was led by a rebel of the name Bel-shimanni. Bel-shimmani's revolt was short-lived; Babylonian documents written during his reign only account for a period of two weeks.

Two years later, Babylon produced another rebel leader, Shamash-eriba. Beginning in the summer of 482 BC, Shamash-eriba seized Babylon itself and other nearby cities, such as Borsippa

Borsippa (Sumerian language, Sumerian: BAD.SI.(A).AB.BAKI or Birs Nimrud, having been identified with Nimrod) is an archeological site in Babylon Governorate, Iraq, built on both sides of a lake about southwest of Babylon on the east bank of th ...

and Dilbat

Dilbat (modern Tell ed-Duleim or Tell al-Deylam) was an ancient Near Eastern city located 25 kilometers south of Babylon on the eastern bank of the Western Euphrates in modern-day Babil Governorate, Iraq. It lies 15 kilometers southeast of the an ...

, and was only defeated in March 481 BC after a lengthy siege of Babylon. The precise cause of the unrest in Babylon is uncertain. It may have been due to tax increases. Prior to these revolts, Babylon had occupied a special position within the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

; the Achaemenid kings had held the titles of "King of Babylon

The king of Babylon ( Akkadian: , later also ) was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon and its kingdom, Babylonia, which existed as an independent realm from the 19th century BC to its fall in the 6th century BC. For the majority ...

" and " King of the Lands," implying that they perceived Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

as a somewhat separate entity within their empire, united with their own kingdom in a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

. After the revolts, however, Xerxes dropped "King of Babylon" from his titulature and divided the previously large Babylonian satrapy (accounting for most of the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to ancient Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC a ...

's territory) into smaller sub-units.

Based on texts written by classical authors, it is often assumed that Xerxes enacted a brutal vengeance on Babylon following the two revolts. According to ancient writers, Xerxes destroyed Babylon's fortifications and damaged the temples in the city. The Esagila was allegedly subject to great damage, and Xerxes allegedly carried the statue of Marduk away from the city, possibly bringing it to Iran and melting it down (classical authors hold that the statue was made entirely of gold, which would have made melting it down possible). Modern historian Amélie Kuhrt considers it unlikely that Xerxes destroyed the temples, but believes that the story of him doing so may derive from an anti-Persian sentiment among the Babylonians. It is doubtful if the statue was removed from Babylon at all and some have even suggested that Xerxes did remove a statue from the city, but that this was the golden statue of a man rather than the statue of the god Marduk

Marduk (; cuneiform: Dingir, ᵈAMAR.UTU; Sumerian language, Sumerian: "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) is a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of Babylon who eventually rose to prominence in the 1st millennium BC. In B ...

. Though mentions of it are lacking considerably compared to earlier periods, contemporary documents suggest that the Babylonian New Year's Festival continued in some form during the Achaemenid period. Because the change in rulership from the Babylonians themselves to the Persians and due to the replacement of the city's elite families by Xerxes following its revolt, it is possible that the festival's traditional rituals and events had changed considerably.

Campaigns

Invasion of the Greek mainland

Darius died while in the process of preparing a second army to invade the Greek mainland, leaving to his son the task of punishing the

Darius died while in the process of preparing a second army to invade the Greek mainland, leaving to his son the task of punishing the Athenians

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, Naxians, and Eretria

Eretria (; , , , , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th century BC, mentioned by many famous writers ...

ns for their interference in the Ionian Revolt, the burning of Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

, and their victory over the Persians at Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

. From 483 BC, Xerxes prepared his expedition: The Xerxes Canal was dug through the isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

of the peninsula of Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; ) is a mountain on the Athos peninsula in northeastern Greece directly on the Aegean Sea. It is an important center of Eastern Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox monasticism.

The mountain and most of the Athos peninsula are governed ...

, provisions were stored in the stations on the road through Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

, and two pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, is a bridge that uses float (nautical), floats or shallow-draft (hull), draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the support ...

s later known as Xerxes' Pontoon Bridges were built across the Hellespont

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey t ...

. Soldiers of many nationalities served in the armies of Xerxes from all over his multi-ethnic massive sized empire and beyond, including the Medes

The Medes were an Iron Age Iranian peoples, Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media (region), Media between western Iran, western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, they occupied the m ...

, Saka

The Saka, Old Chinese, old , Pinyin, mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit (Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples, Eastern Iranian peoples who lived in the Eurasian ...

, Elamites, Assyrians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

, Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns, Babylonians

Babylonia (; , ) was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as an Akkadian-populated but Amorite-ru ...

, Egyptians

Egyptians (, ; , ; ) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian identity is closely tied to Geography of Egypt, geography. The population is concentrated in the Nile Valley, a small strip of cultivable land stretchi ...

, Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, Arabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

ians, Thracians

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared betwee ...

, Paeonians, Achaean Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, Ionian Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, Aegean Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, Aeolian Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, Greeks from Pontus, Colchians

In classical antiquity and Greco-Roman geography, Colchis (; ) was an exonym for the Georgian polity of Egrisi ( ka, ეგრისი) located on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, centered in present-day western Georgia.

Its population, the ...

, Sindhis

Sindhis are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group originating from and native to Sindh, a region of Pakistan, who share a common Sindhi culture, history, ancestry, and language. The historical homeland of Sindhis is bordered by southeastern Balochi ...

and many more.

According to the Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, Xerxes's first attempt to bridge the Hellespont ended in failure when a storm destroyed the flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. In 2022, France produced 75% of t ...

and papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

cables of the bridges. In retaliation, Xerxes ordered the Hellespont (the strait itself) whipped three hundred times, and had fetters thrown into the water. Xerxes's second attempt to bridge the Hellespont was successful. The Carthaginian invasion of Sicily deprived Greece of the support of the powerful monarchs of Syracuse and Agrigentum; ancient sources assume Xerxes was responsible, modern scholarship is skeptical. Many smaller Greek states, moreover, took the side of the Persians, especially Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

, Thebes and Argos. Xerxes was victorious during the initial battles.

Xerxes set out in the spring of 480 BC from Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

with a fleet and army which Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

estimated was roughly one million strong along with 10,000 elite warriors named the Immortals. More recent estimates place the Persian force at around 60,000 combatants.

Battle of Thermopylae and destruction of Athens

At the

At the Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ) was fought in 480 BC between the Achaemenid Empire, Achaemenid Persian Empire under Xerxes I and an alliance of Polis, Greek city-states led by Sparta under Leonidas I. Lasting over the course of three days, it wa ...

, a small force of Greek warriors led by King Leonidas of Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

resisted the much larger Persian forces, but were ultimately defeated. According to Herodotus, the Persians broke the Spartan phalanx

The phalanx (: phalanxes or phalanges) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together. The term is particularly used t ...

after a Greek man called Ephialtes betrayed his country by telling the Persians of another pass around the mountains. At Artemisium, large storms had destroyed ships from the Greek side and so the battle stopped prematurely as the Greeks received news of the defeat at Thermopylae and retreated.

After Thermopylae, Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

was captured. Most of the Athenians had abandoned the city and fled to the island of Salamis before Xerxes arrived. A small group attempted to defend the Athenian Acropolis, but they were defeated. Xerxes ordered the Destruction of Athens and burnt the city, leaving an archaeologically attested destruction layer, known as the Perserschutt. The Persians thus gained control of all of mainland Greece to the north of the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

.

Battles of Salamis and Plataea

Xerxes was induced, by the message ofThemistocles

Themistocles (; ; ) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As a politician, Themistocles was a populist, having th ...

(against the advice of Artemisia of Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus ( ; Latin: ''Halicarnassus'' or ''Halicarnāsus''; ''Halikarnāssós''; ; Carian language, Carian: 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 ''alos k̂arnos'') was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia.

), to attack the Greek fleet under unfavourable conditions, rather than sending a part of his ships to the Peloponnesus

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the ...

and awaiting the dissolution of the Greek armies. The Battle of Salamis (September, 480 BC) was won by the Greek fleet, after which Xerxes set up a winter camp in Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

.

According to Herodotus, fearing that the Greeks might attack the bridges across the Hellespont

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey t ...

and trap his army in Europe, Xerxes decided to retreat back to Asia, taking the greater part of the army with him.HerodotuVIII, 97

/ref> Another cause of the retreat might have been that the continued unrest in

Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

, a key province of the empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

, required the king's personal attention.

He left behind a contingent in Greece to finish the campaign under Mardonius, who according to Herodotus had suggested the retreat in the first place. This force was defeated the following year at Plataea

Plataea (; , ''Plátaia'') was an ancient Greek city-state situated in Boeotia near the frontier with Attica at the foot of Mt. Cithaeron, between the mountain and the river Asopus, which divided its territory from that of Thebes. Its inhab ...

by the combined forces of the Greek city states, ending the Persian offensive on Greece for good.

Construction projects

After his military blunders in Greece, Xerxes returned to Persia and oversaw the completion of the many construction projects left unfinished by his father atSusa

Susa ( ) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh River, Karkheh and Dez River, Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital o ...

and Persepolis

Persepolis (; ; ) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by the southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian cultural heritage sites and ...

. He oversaw the building of the Gate of All Nations

The Gate of All Nations ( ), also known as the Gate of Xerxes, is located in the ruins of the ancient city of Persepolis, Iran.

The construction of the Stairs of All Nations and the Gate of All Nations was ordered by the Achaemenid king Xerxes I ...

and the Hall of a Hundred Columns at Persepolis, which are the largest and most imposing structures of the palace. He oversaw the completion of the Apadana

Apadana (, or ) is a large hypostyle hall in Persepolis, Iran. It belongs to the oldest building phase of the city of Persepolis, in the first half of the 5th century BC, as part of the original design by Darius I, Darius the Great. Its cons ...

, the Tachara (Palace of Darius) and the Treasury, all started by Darius, as well as having his own palace built which was twice the size of his father's. His taste in architecture was similar to that of Darius, though on an even more gigantic scale. He had colorful enameled brick laid on the exterior face of the Apadana

Apadana (, or ) is a large hypostyle hall in Persepolis, Iran. It belongs to the oldest building phase of the city of Persepolis, in the first half of the 5th century BC, as part of the original design by Darius I, Darius the Great. Its cons ...

. He also maintained the Royal Road built by his father and completed the Susa Gate and built a palace in Susa.

Death and succession

In August 465 BC, Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard and the most powerful official in the Persian court, assassinated Xerxes with the help of aeunuch

A eunuch ( , ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function. The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2 ...

, Aspamitres. Although the Hyrcanian Artabanus bore the same name as the famed uncle of Xerxes, his rise to prominence was due to his popularity in religious quarters of the court and harem intrigues. He put his seven sons in key positions and had a plan to dethrone the Achaemenids

The Achaemenid dynasty ( ; ; ; ) was a royal house that ruled the Achaemenid Empire, which eventually stretched from Egypt and Thrace in the west to Central Asia and the Indus Valley in the east.

Origins

The history of the Achaemenid dy ...

.

Greek historians give differing accounts of events. According to Ctesias

Ctesias ( ; ; ), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fifth century BC, was physician to the Acha ...

(in Persica 20), Artabanus then accused the Crown Prince Darius, Xerxes's eldest son, of the murder and persuaded another of Xerxes's sons, Artaxerxes, to avenge the patricide by killing Darius. But according to Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

(in Politics 5.1311b), Artabanus killed Darius first and then killed Xerxes. After Artaxerxes discovered the murder, he killed Artabanus and his sons. Participating in these intrigues was the general Megabyzus, whose decision to switch sides probably saved the Achaemenids from losing their control of the Persian throne.

Religion

While there is no general consensus in scholarship as to whether Xerxes and his predecessors had been influenced byZoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zoroaster, Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, ...

, it is well established that Xerxes was a firm believer in Ahura Mazda

Ahura Mazda (; ; or , ),The former is the New Persian rendering of the Avestan form, while the latter derives from Middle Persian. also known as Horomazes (),, is the only creator deity and Sky deity, god of the sky in the ancient Iranian ...

, whom he saw as the supreme deity. However, Ahura Mazda was also worshipped by adherents of the (Indo-)Iranian religious tradition. On his treatment of other religions, Xerxes followed the same policy as his predecessors: he appealed to local religious scholars, made sacrifices to local deities, and destroyed temples in cities and countries that caused disorder.

Wives and children

By queen Amestris:

* Darius, the first born son, murdered by

By queen Amestris:

* Darius, the first born son, murdered by Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, ; ) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "Long-handed" ( ''Makrókheir''; ), allegedly because his ri ...

or Artabanus.

* Hystaspes, murdered by Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, ; ) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "Long-handed" ( ''Makrókheir''; ), allegedly because his ri ...

.

* Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, ; ) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "Long-handed" ( ''Makrókheir''; ), allegedly because his ri ...

* Rhodogune

* Amytis, wife of Megabyzus.

By unknown wives or mistresses:

* Artarius, satrap of Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

.

* Tithraustes

Tithraustes (Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ) was the Persian satrap of Sardis for several years in the early 4th century BC. Due to scanty historical records, little is known of the man or his activities. He was sent out from Susa to replace ...

* Parysatis

Parysatis (; , ; 5th-century BC) was a Persian queen, consort of Darius II and had a large influence during the reign of Artaxerxes II.

Biography

Parysatis was the daughter of King of Kings Artaxerxes I of Persia and Andria of Babylon. She wa ...

* Ratashah

Reception

Xerxes' presentation in Greek and Roman sources is largely negative and this set the tone for most subsequent depictions of him within the western tradition. Xerxes is a central character ofAeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

' play ''The Persians

''The Persians'' (, ''Persai'', Latinised as ''Persae'') is an ancient Greek tragedy written during the Classical period of Ancient Greece by the Greek tragedian Aeschylus. It is the second and only surviving part of a now otherwise lost trilog ...

'', first performed in Athens in 472 BC, only seven years after his invasion of Greece. The play presents him as an effeminate figure and his hubristic effort to bring both Asia and Europe under his control leads to the ruin of both himself and his kingdom.

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

's ''Histories'', written later in the fifth century BC, centre on the Persian Wars, with Xerxes as a major figure. Some of Herodotus' information is spurious. Pierre Briant has accused him of presenting a stereotyped and biased portrayal of the Persians. Richard Stoneman regards his portrayal of Xerxes as nuanced and tragic, compared to the vilification that he suffered at the hands of the Macedonian king Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

().

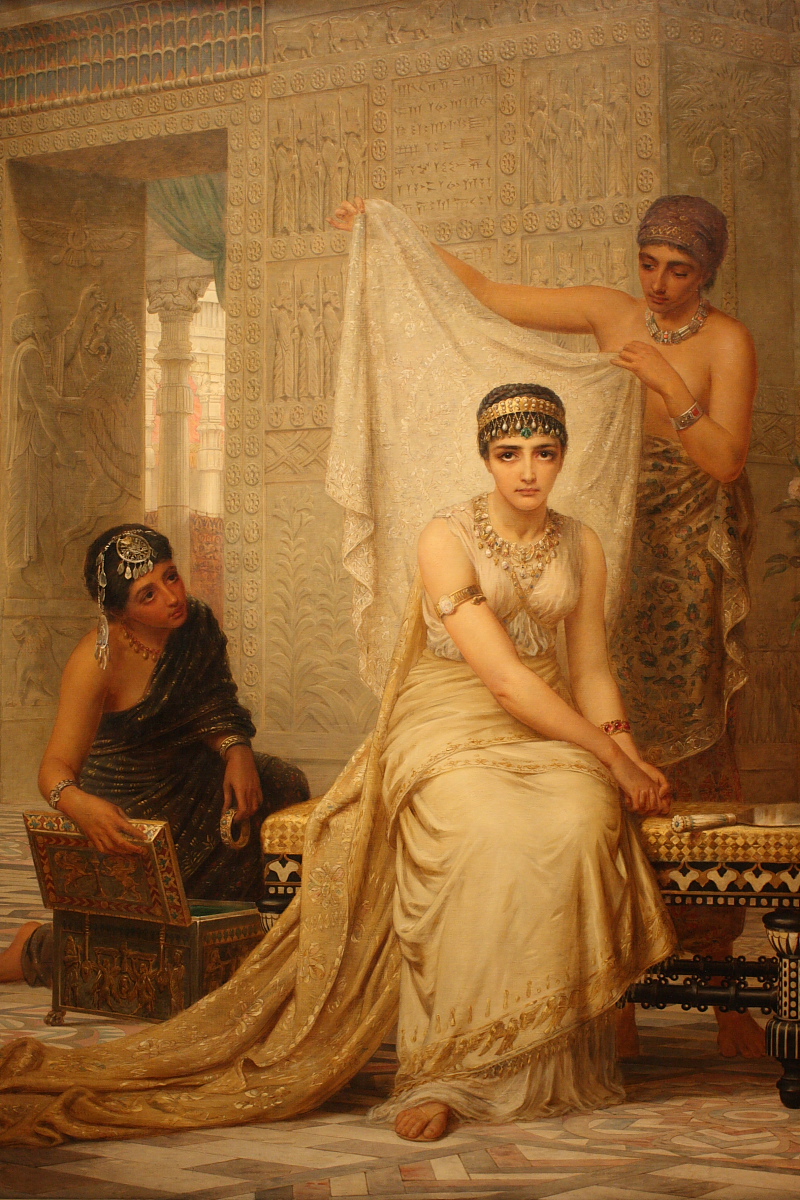

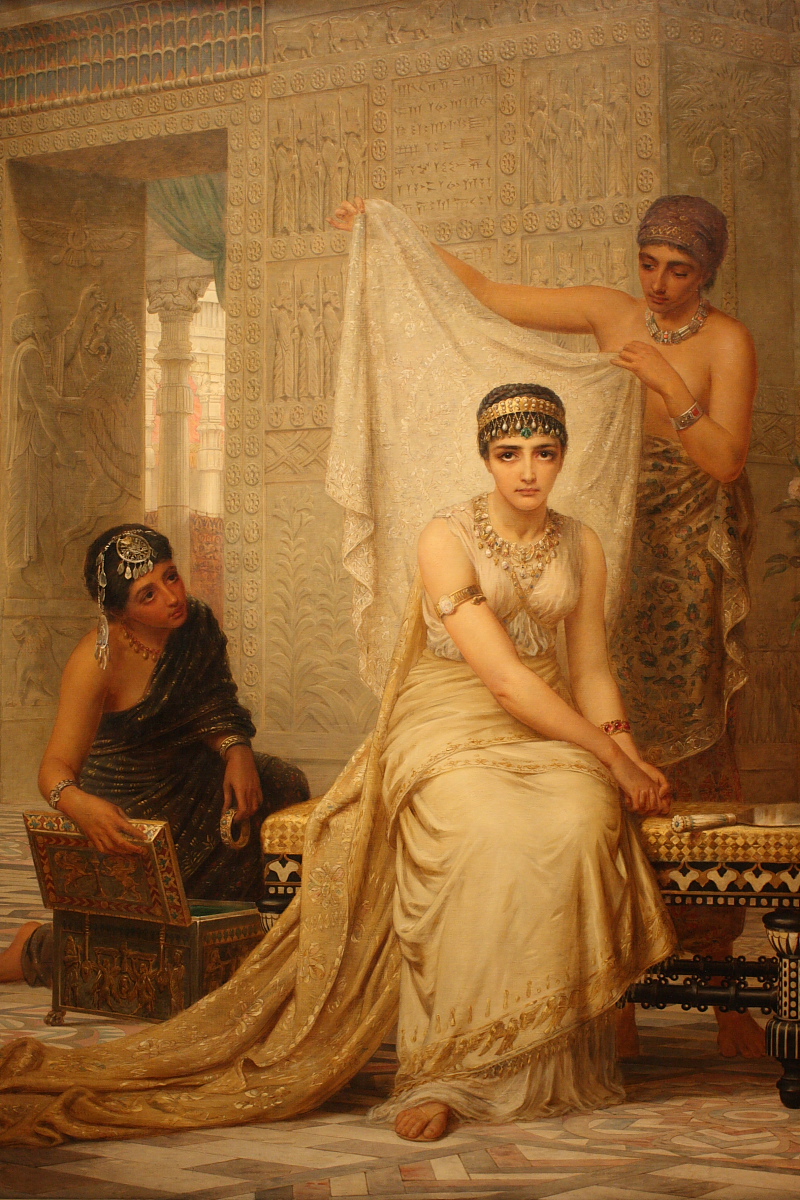

Xerxes is identified with the king Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

in the biblical Book of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the wikt:מגילה, Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Megillot, Five Scrolls () in the Hebr ...

, which some scholars, including Eduard Schwartz, William Rainey Harper, and Michael V. Fox

Michael V. Fox (1940–2025) was an American-Israeli biblical scholar. He was the Halls-Bascom Professor Emeritus in the Department of Hebrew and Semitic Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Fox was described as a "highly re ...

, consider to be historical romance. There is nothing close to a consensus, however, as to what historical event provided the basis for the story.

Xerxes is the protagonist of the opera ''Serse

''Serse'' (; English title: ''Xerxes''; HWV 40) is an opera seria in three acts by George Frideric Handel. It was first performed in London on 15 April 1738. The Italian libretto was adapted by an unknown hand from that by Silvio Stampiglia (16 ...

'' by the German-English Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

composer George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( ; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti.

Born in Halle, Germany, H ...

. It was first performed in the King's Theatre London on 15 April 1738. The famous aria

In music, an aria (, ; : , ; ''arias'' in common usage; diminutive form: arietta, ; : ariette; in English simply air (music), air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrument (music), instrumental or orchestral accompan ...

opens the opera.

The murder of Xerxes by Artabanus (''Artabano''), execution of crown prince Darius (''Dario''), revolt by Megabyzus (''Megabise''), and subsequent succession of Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, ; ) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "Long-handed" ( ''Makrókheir''; ), allegedly because his ri ...

is romanticised by the Italian poet Metastasio

Pietro Antonio Domenico Trapassi (3 January 1698 – 12 April 1782), better known by his pseudonym of Pietro Metastasio (), was an Italian poet and librettist, considered the most important writer of ''opera seria'' libretti.

Early life

Met ...

in his opera libretto '' Artaserse'' (1730), which was first set to music by Leonardo Vinci, and subsequently by other composers such as Johann Adolf Hasse and Johann Christian Bach

Johann Christian Bach (5 September 1735 – 1 January 1782) was a German composer of the Classical era, the youngest son of Johann Sebastian Bach. He received his early musical training from his father, and later from his half-brother, Carl ...

.

The historical novel ''Xerxes of de Hoogmoed'' (1919) by Dutch writer Louis Couperus

Louis Marie-Anne Couperus (10 June 1863 – 16 July 1923) was a Dutch novelist and poet. His oeuvre contains a wide variety of genres: lyric poetry, psychological fiction, psychological and historical fiction, historical novels, novellas, short ...

describes the Persian wars from the perspective of Xerxes. Though the account is fictionalised, Couperus nevertheless based himself on an extensive study of Herodotus. The English translation ''Arrogance: The Conquests of Xerxes'' by Frederick H. Martens appeared in 1930.

Later generations' fascination with ancient Sparta, particularly the

Later generations' fascination with ancient Sparta, particularly the Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ) was fought in 480 BC between the Achaemenid Empire, Achaemenid Persian Empire under Xerxes I and an alliance of Polis, Greek city-states led by Sparta under Leonidas I. Lasting over the course of three days, it wa ...

, has led to Xerxes' portrayal in works of popular culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of cultural practice, practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art

. He was played by David Farrar in the film '' The 300 Spartans'' (1962), where he is portrayed as a cruel, power-crazed despot and an inept commander. He also features prominently in the graphic novels ''f. pop art

F is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet.

F may also refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* F or f, the number 15 (number), 15 in hexadecimal and higher positional systems

* ''p'F'q'', the hypergeometric function

* F-distributi ...

or mass art, sometimes contraste ...300

__NOTOC__

Year 300 ( CCC) was a leap year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Constantius and Valerius (or, less frequently, year 1053 ''Ab urbe condita''). The denomination 300 ...

'' and '' Xerxes: The Fall of the House of Darius and the Rise of Alexander'' by Frank Miller, as well as the film adaptation ''300

__NOTOC__

Year 300 ( CCC) was a leap year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Constantius and Valerius (or, less frequently, year 1053 ''Ab urbe condita''). The denomination 300 ...

'' (2007) and its sequel '' 300: Rise of an Empire'' (2014), as portrayed by Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

ian actor Rodrigo Santoro

Rodrigo Junqueira Reis Santoro (; born 22 August 1975) is a Brazilian actor. He is known in Brazil for his appearance on local telenovelas and internationally for his portrayal of Persian King Xerxes I of Persia, Xerxes in the film ''300 (film), ...

, in which he is represented as a giant man with androgynous qualities, who claims to be a god-king. This portrayal attracted controversy, especially in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. Ken Davitian plays Xerxes in '' Meet the Spartans'', a parody of the first ''300'' movie replete with sophomoric humour and deliberate anachronisms

An anachronism (from the Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time periods. The most common type ...

. Similarly, a highly satirized depiction of Xerxes based on his portrayal in ''300'' appears in the ''South Park

''South Park'' is an American animated sitcom created by Trey Parker and Matt Stone, and developed by Brian Graden for Comedy Central. The series revolves around four boysStan Marsh, Kyle Broflovski, Eric Cartman, and Kenny McCormickand the ...

'' episode " D-Yikes!"

Other works dealing with the Persian Empire or the Biblical story of Esther

Esther (; ), originally Hadassah (; ), is the eponymous heroine of the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical narrative, which is set in the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Ahasuerus falls in love with Esther and ma ...

have also featured or alluded to Xerxes, such as the video game ''Assassin's Creed Odyssey

''Assassin's Creed Odyssey'' is a 2018 action role-playing game developed by Ubisoft Quebec and published by Ubisoft. It is the eleventh major installment in the ''Assassin's Creed'' series and the successor to ''Assassin's Creed Origins'' (2 ...

'' and the film ''One Night with the King

''One Night with the King'' is a 2006 American religious epic film produced by Matthew Crouch, Matt Crouch and Laurie Crouch of Gener8Xion Entertainment, directed by Michael O. Sajbel, and starring Peter O'Toole, Tiffany Dupont, John Rhys-Davies, a ...

'' (2006), in which Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

(Xerxes) was portrayed by British actor Luke Goss. He is the leader of the Persian Empire in the video game '' Civilization II'' and '' III'' (along with Scheherazade

Scheherazade () is a major character and the storyteller in the frame story, frame narrative of the Middle Eastern collection of tales known as the ''One Thousand and One Nights''.

Name

According to modern scholarship, the name ''Scheherazade ...

), although ''Civilization IV

''Civilization IV'' (also known as ''Sid Meier's Civilization IV'') is a 2005 4X turn-based strategy video game developed by Firaxis Games and published by 2K. It is the fourth installment of the ''Civilization'' series and was designed by S ...

'' replaces him with Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

and Darius I

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

. He reappears as a Leader in ''Civilization VII

''Sid Meier's Civilization VII'' is a 4X turn-based strategy video game developed by Firaxis Games and published by 2K. The game was released on February 11, 2025, for Windows, macOS, Linux, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Xbox One ...

''. In the ''Age of Empires

''Age of Empires'' is a series of historical real-time strategy video games, originally developed by Ensemble Studios and published by Xbox Game Studios.

The first title in the series, ''Age of Empires'', focused on events in Europe, Afri ...

'', Xerxes featured as a short swordsman.

Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal ( ; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his acerbic epigrammatic wit. His novels and essays interrogated the Social norm, social and sexual ...

, in his historical fiction novel '' Creation'' (1981), describes at length the rise of the Achaemenids, especially Darius I, and presents the life and death circumstances of Xerxes. Vidal's version of the Persian Wars, which diverges from the orthodoxy of the Greek histories, is told through the invented character of Cyrus Spitama, a half-Greek, half-Persian, and grandson of the prophet Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

. Thanks to his family connection, Cyrus is brought up in the Persian court after the murder of Zoroaster, becoming the boyhood friend of Xerxes, and later a diplomat who is sent to India, and later to Greece, and who is thereby able to gain privileged access to many leading historical figures of the period.Gore Vidal, ''Creation: A Novel'' (Random House, 1981)

Xerxes (Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

) is portrayed by Richard Egan in the 1960 film '' Esther and the King'' and by Joel Smallbone in the 2013 film, '' The Book of Esther''. In at least one of these films, the events of the Book of Esther are depicted as taking place upon Xerxes' return from Greece.

Xerxes plays an important background role (never making an appearance) in two short works of alternate history

Alternate history (also referred to as alternative history, allohistory, althist, or simply A.H.) is a subgenre of speculative fiction in which one or more historical events have occurred but are resolved differently than in actual history. As ...

taking place generations after his complete victory over Greece. These are: "Counting Potsherds" by Harry Turtledove

Harry Norman Turtledove (born June 14, 1949) is an American author who is best known for his work in the genres of alternate history, historical fiction, fantasy, science fiction, and mystery fiction. He is a student of history and completed his ...

in his anthology '' Departures'' and "The Craft of War" by Lois Tilton

Lois Tilton is an American science fiction, fantasy, alternate history, and horror writer who has won the Sidewise Award and been a finalist for the Nebula Award. She has also written a number of innovative vampire stories."Critical Mass" by Do ...

in ''Alternate Generals'' volume 1 (edited by Turtledove).

See also

* List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sourcesNotes

References

Bibliography

Ancient sources

* *Modern sources

* * * * * * Bridges, Emma (2014). Imagining Xerxes: Ancient Perspectives on a Persian King. Bloomsbury. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Use dmy dates, date=April 2021 510s BC births 465 BC deaths 5th-century BC Kings of the Achaemenid Empire 5th-century BC murdered monarchs 5th-century BC pharaohs Book of Esther Battle of Salamis Battle of Thermopylae Family of Darius the Great Kings of the Achaemenid Empire Murdered Persian monarchs Persian people of the Greco-Persian Wars Pharaohs of the Achaemenid dynasty of Egypt Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt Year of birth uncertain