X-ray crystallography is the experimental science of determining the atomic and molecular structure of a

crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident

X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

s to

diffract in specific directions. By measuring the angles and intensities of the

X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the waves. ...

, a

crystallographer can produce a three-dimensional picture of the density of

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s within the crystal and the positions of the atoms, as well as their

chemical bond

A chemical bond is the association of atoms or ions to form molecules, crystals, and other structures. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds or through the sharing of electrons a ...

s,

crystallographic disorder, and other information.

X-ray crystallography has been fundamental in the development of many scientific fields. In its first decades of use, this method determined the size of

atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

s, the lengths and types of chemical bonds, and the atomic-scale differences between various materials, especially minerals and

alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which in most cases at least one is a metal, metallic element, although it is also sometimes used for mixtures of elements; herein only metallic alloys are described. Metallic alloys often have prop ...

s. The method has also revealed the structure and function of many biological molecules, including

vitamin

Vitamins are Organic compound, organic molecules (or a set of closely related molecules called vitamer, vitamers) that are essential to an organism in small quantities for proper metabolism, metabolic function. Nutrient#Essential nutrients, ...

s, drugs,

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s and

nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s such as

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

. X-ray crystallography is still the primary method for characterizing the atomic structure of materials and in differentiating materials that appear similar in other experiments. X-ray

crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat ...

s can also help explain unusual

electronic or

elastic

Elastic is a word often used to describe or identify certain types of elastomer, Elastic (notion), elastic used in garments or stretch fabric, stretchable fabrics.

Elastic may also refer to:

Alternative name

* Rubber band, ring-shaped band of rub ...

properties of a material, shed light on chemical interactions and processes, or serve as the basis for

designing pharmaceuticals against diseases.

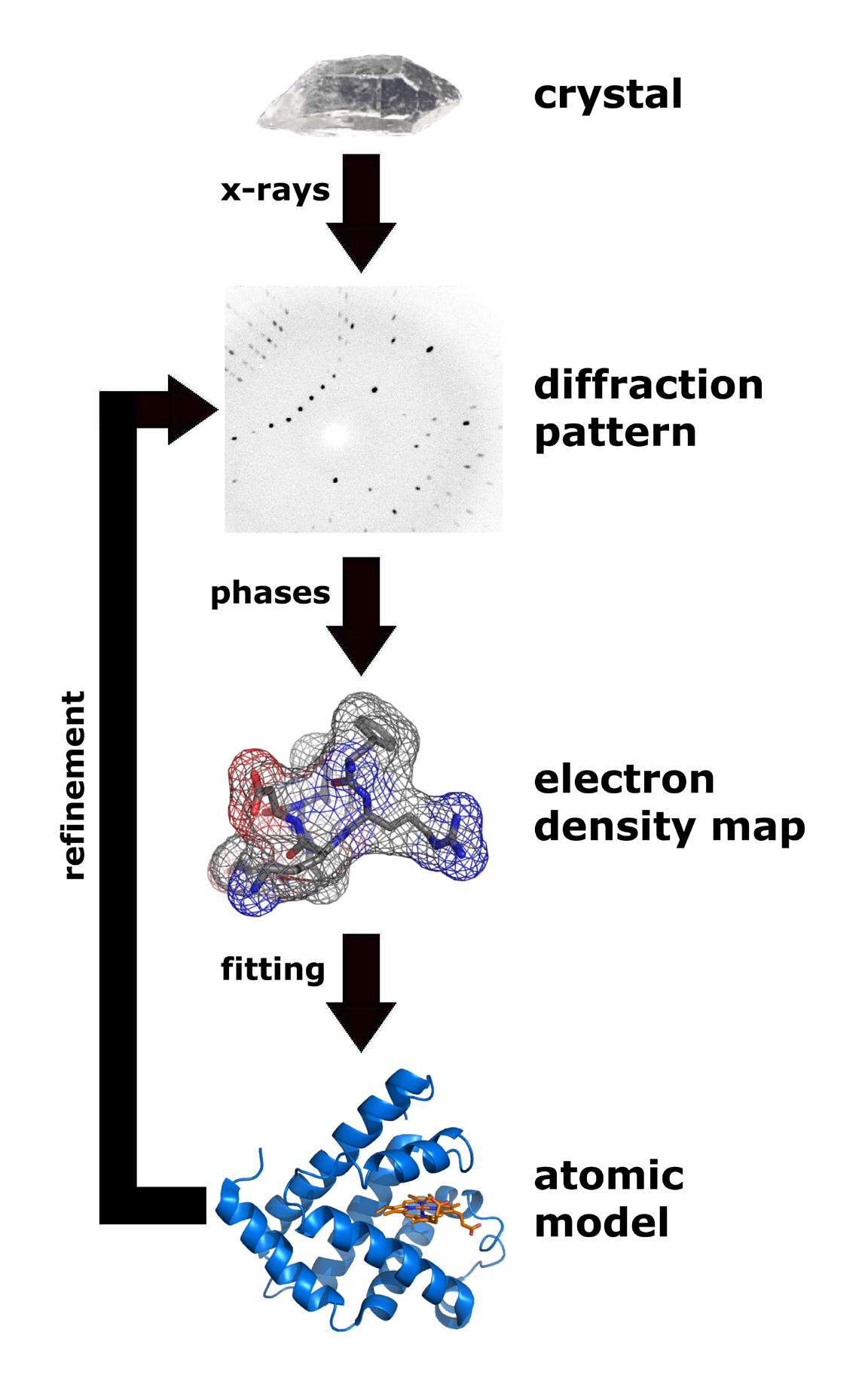

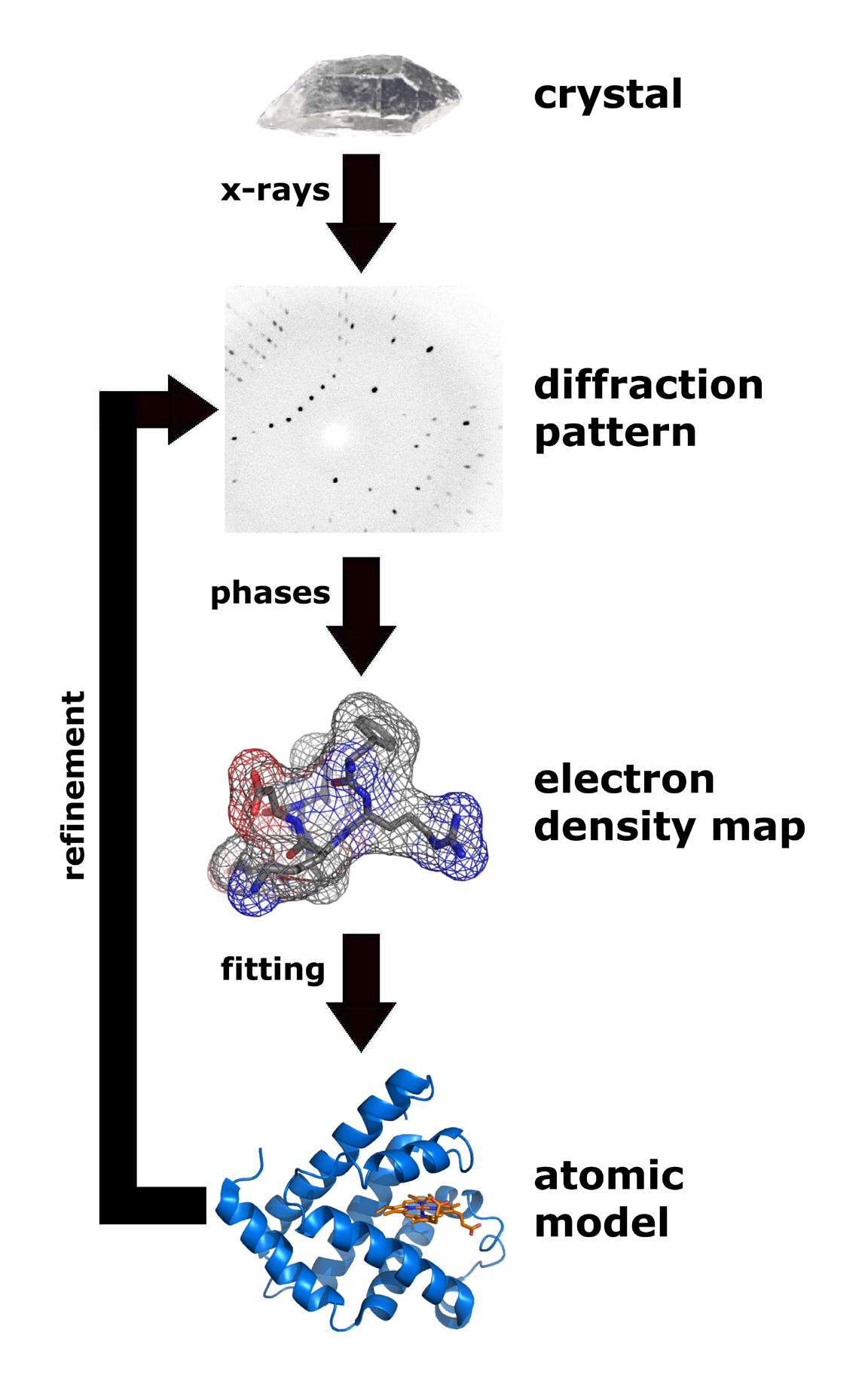

Modern work involves a number of steps all of which are important. The preliminary steps include preparing good quality samples, careful recording of the diffracted intensities, and processing of the data to remove artifacts. A variety of different methods are then used to obtain an estimate of the atomic structure, generically called direct methods. With an initial estimate further computational techniques such as those involving difference maps are used to complete the structure. The final step is a numerical refinement of the atomic positions against the experimental data, sometimes assisted by ''ab-initio'' calculations. In almost all cases new structures are deposited in databases available to the international community.

History

Crystals, though long admired for their regularity and

symmetry

Symmetry () in everyday life refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, the term has a more precise definition and is usually used to refer to an object that is Invariant (mathematics), invariant und ...

, were not investigated scientifically until the 17th century.

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

hypothesized in his work ''Strena seu de Nive Sexangula'' (A New Year's Gift of Hexagonal Snow) (1611) that the hexagonal symmetry of

snowflake crystals was due to a regular packing of spherical water particles. The Danish scientist

Nicolas Steno

Niels Steensen (; Latinized to Nicolas Steno or Nicolaus Stenonius; 1 January 1638 – 25 November 1686 ) was a Danish scientist, a pioneer in both anatomy and geology who became a Catholic bishop in his later years. He has been beatified ...

(1669) pioneered experimental investigations of crystal symmetry. Steno showed that the angles between the faces are the same in every exemplar of a particular type of crystal (

law of constancy of interfacial angles

The law of constancy of interfacial angles (; ) is an Empirical research, empirical law in the fields of crystallography and mineralogy concerning the shape, or morphology, of crystals. The law states that the angles between adjacent corresponding ...

).

René Just Haüy

René Just Haüy () FRS MWS FRSE (28 February 1743 – 1 June 1822) was a French priest and mineralogist, commonly styled the Abbé Haüy after he was made an honorary canon of Notre-Dame de Paris, Notre Dame. Due to his innovative work on cryst ...

(1784) discovered that every face of a crystal can be described by simple stacking patterns of blocks of the same shape and size (

law of decrements). Hence,

William Hallowes Miller

Prof William Hallowes Miller FRS HFRSE LLD DCL (6 April 180120 May 1880) was a Welsh mineralogist and laid the foundations of modern crystallography.

Miller indices are named after him, the method having been described in his ''Treatise on Cr ...

in 1839 was able to give each face a unique label of three small integers, the

Miller indices

Miller indices form a notation system in crystallography for lattice planes in crystal (Bravais) lattices.

In particular, a family of lattice planes of a given (direct) Bravais lattice is determined by three integers ''h'', ''k'', and ''� ...

which remain in use for identifying crystal faces. Haüy's study led to the idea that crystals are a regular three-dimensional array (a

Bravais lattice

In geometry and crystallography, a Bravais lattice, named after , is an infinite array of discrete points generated by a set of discrete translation operations described in three dimensional space by

: \mathbf = n_1 \mathbf_1 + n_2 \mathbf_2 ...

) of atoms and

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

s; a single

unit cell

In geometry, biology, mineralogy and solid state physics, a unit cell is a repeating unit formed by the vectors spanning the points of a lattice. Despite its suggestive name, the unit cell (unlike a unit vector

In mathematics, a unit vector i ...

is repeated indefinitely along three principal directions. In the 19th century, a complete catalog of the possible symmetries of a crystal was worked out by

Johan Hessel,

Auguste Bravais,

Evgraf Fedorov

Evgraf Stepanovich Fedorov (, – 21 May 1919) was a Russian mathematician, crystallographer and mineralogist.

Fedorov was born in the Russian city of Orenburg. His father was a topographical engineer. The family later moved to Saint Petersb ...

,

Arthur Schönflies and (belatedly)

William Barlow (1894). Barlow proposed several crystal structures in the 1880s that were validated later by X-ray crystallography; however, the available data were too scarce in the 1880s to accept his models as conclusive.

Wilhelm Röntgen

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (; 27 March 1845 – 10 February 1923), sometimes Transliteration, transliterated as Roentgen ( ), was a German physicist who produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range known as X-rays. As ...

discovered X-rays in 1895.

Physicists were uncertain of the nature of X-rays, but suspected that they were waves of

electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

. The

Maxwell

Maxwell may refer to:

People

* Maxwell (surname), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

** James Clerk Maxwell, mathematician and physicist

* Justice Maxwell (disambiguation)

* Maxwell baronets, in the Baronetage of N ...

theory of

electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

was well accepted, and experiments by

Charles Glover Barkla

Charles Glover Barkla (7 June 1877 – 23 October 1944) was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1917 for his discovery of characteristic X-rays.

Life

Barkla was born in Widnes, England, to John Martin Barkla, a sec ...

showed that X-rays exhibited phenomena associated with electromagnetic waves, including transverse

polarization and

spectral line

A spectral line is a weaker or stronger region in an otherwise uniform and continuous spectrum. It may result from emission (electromagnetic radiation), emission or absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption of light in a narrow frequency ...

s akin to those observed in the visible wavelengths. Barkla created the x-ray notation for sharp spectral lines, noting in 1909 two separate energies, at first naming them "A" and "B" and then supposing that there may be lines prior to "A", he started an alphabet numbering beginning with "K."

[Michael Eckert, Disputed discovery: the beginnings of X-ray diffraction in crystals in 1912 and its repercussions, January 2011, Acta crystallographica. Section A, Foundations of crystallography 68(1):30–39 This Laue centennial article has also been published in Zeitschrift für Kristallographie ckert (2012). Z. Kristallogr. 227, 27–35] Single-slit experiments in the laboratory of

Arnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in Atomic physics, atomic and Quantum mechanics, quantum physics, and also educated and ...

suggested that X-rays had a

wavelength

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same ''phase (waves ...

of about 1

angstrom

The angstrom (; ) is a unit of length equal to m; that is, one ten-billionth of a metre, a hundred-millionth of a centimetre, 0.1 nanometre, or 100 picometres. The unit is named after the Swedish physicist Anders Jonas Ångström (1814–18 ...

. X-rays are not only waves but also have particle properties causing Sommerfeld to coin the name

Bremsstrahlung

In particle physics, bremsstrahlung (; ; ) is electromagnetic radiation produced by the deceleration of a charged particle when deflected by another charged particle, typically an electron by an atomic nucleus. The moving particle loses kinetic ...

for the continuous spectra when they were formed when electrons bombarded a material.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

introduced the photon concept in 1905, but it was not broadly accepted until 1922, when

Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American particle physicist who won the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radiati ...

confirmed it by the scattering of X-rays from electrons. The particle-like properties of X-rays, such as their ionization of gases, had prompted

William Henry Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist and X-ray crystallographer who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nobel Prize (in any fiel ...

to argue in 1907 that X-rays were ''not'' electromagnetic radiation. Bragg's view proved unpopular and the observation of

X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the waves. ...

by

Max von Laue

Max Theodor Felix von Laue (; 9 October 1879 – 24 April 1960) was a German physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 "for his discovery of the X-ray diffraction, diffraction of X-rays by crystals".

In addition to his scientifi ...

in 1912

confirmed that X-rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation.

The idea that crystals could be used as a

diffraction grating

In optics, a diffraction grating is an optical grating with a periodic structure that diffraction, diffracts light, or another type of electromagnetic radiation, into several beams traveling in different directions (i.e., different diffractio ...

for

X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

s arose in 1912 in a conversation between

Paul Peter Ewald and

Max von Laue

Max Theodor Felix von Laue (; 9 October 1879 – 24 April 1960) was a German physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 "for his discovery of the X-ray diffraction, diffraction of X-rays by crystals".

In addition to his scientifi ...

in the

English Garden

The English landscape garden, also called English landscape park or simply the English garden (, , , , ), is a style of "landscape" garden which emerged in England in the early 18th century, and spread across Europe, replacing the more formal ...

in Munich. Ewald had proposed a resonator model of crystals for his thesis, but this model could not be validated using

visible light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm ...

, since the wavelength was much larger than the spacing between the resonators. Von Laue realized that electromagnetic radiation of a shorter wavelength was needed, and suggested that X-rays might have a wavelength comparable to the unit-cell spacing in crystals. Von Laue worked with two technicians,

Walter Friedrich and his assistant Paul Knipping, to shine a beam of X-rays through a

copper sulfate Copper sulfate may refer to:

* Copper(II) sulfate, CuSO4, a common, greenish blue compound used as a fungicide and herbicide

* Copper(I) sulfate, Cu2SO4, an unstable white solid which is uncommonly used

{{chemistry index

Copper compounds ...

crystal and record its diffraction on a

photographic plate

Photographic plates preceded film as the primary medium for capturing images in photography. These plates, made of metal or glass and coated with a light-sensitive emulsion, were integral to early photographic processes such as heliography, d ...

. After being developed, the plate showed a large number of well-defined spots arranged in a pattern of intersecting circles around the spot produced by the central beam. The results were presented to the

Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities

The Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities () is an independent public institution, located in Munich. It appoints scholars whose research has contributed considerably to the increase of knowledge within their subject. The general goal of th ...

in June 1912 as "Interferenz-Erscheinungen bei Röntgenstrahlen" (Interference phenomena in X-rays).

Von Laue developed a law that connects the scattering angles and the size and orientation of the unit-cell spacings in the crystal, for which he was awarded the

Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

in 1914.

After Von Laue's pioneering research, the field developed rapidly, most notably by physicists

William Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist who shared the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics with his father William Henry Bragg "for their services in the analysis of crystal structure by ...

and his father

William Henry Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist and X-ray crystallographer who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nobel Prize (in any fiel ...

. In 1912–1913, the younger Bragg developed

Bragg's law, which connects the scattering with evenly spaced planes within a crystal.

The Braggs, father and son, shared the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work in crystallography. The earliest structures were generally simple; as computational and experimental methods improved over the next decades, it became feasible to deduce reliable atomic positions for more complicated arrangements of atoms.

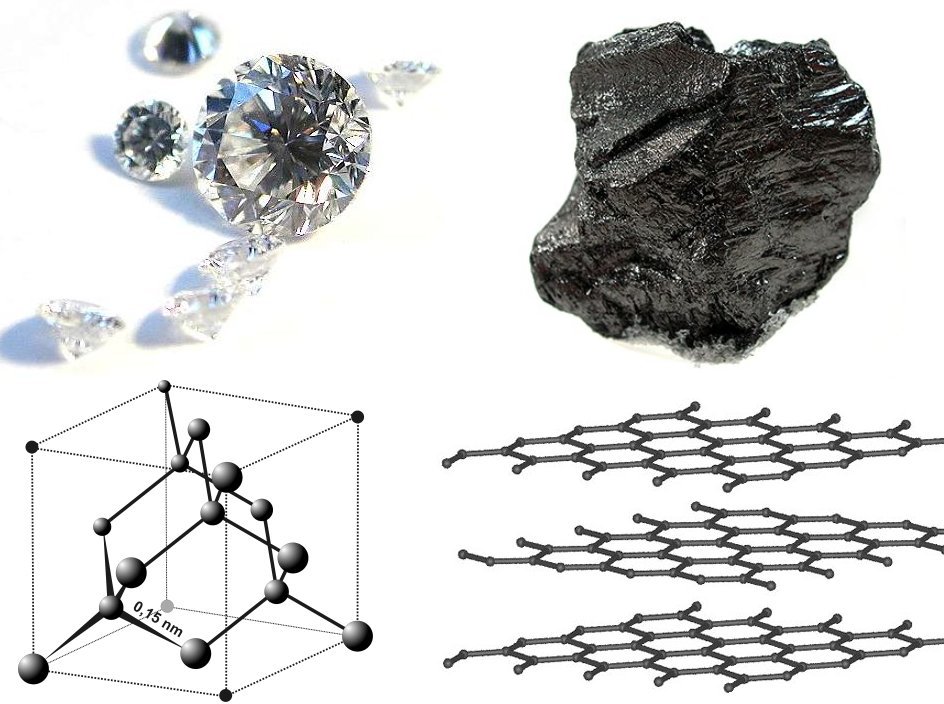

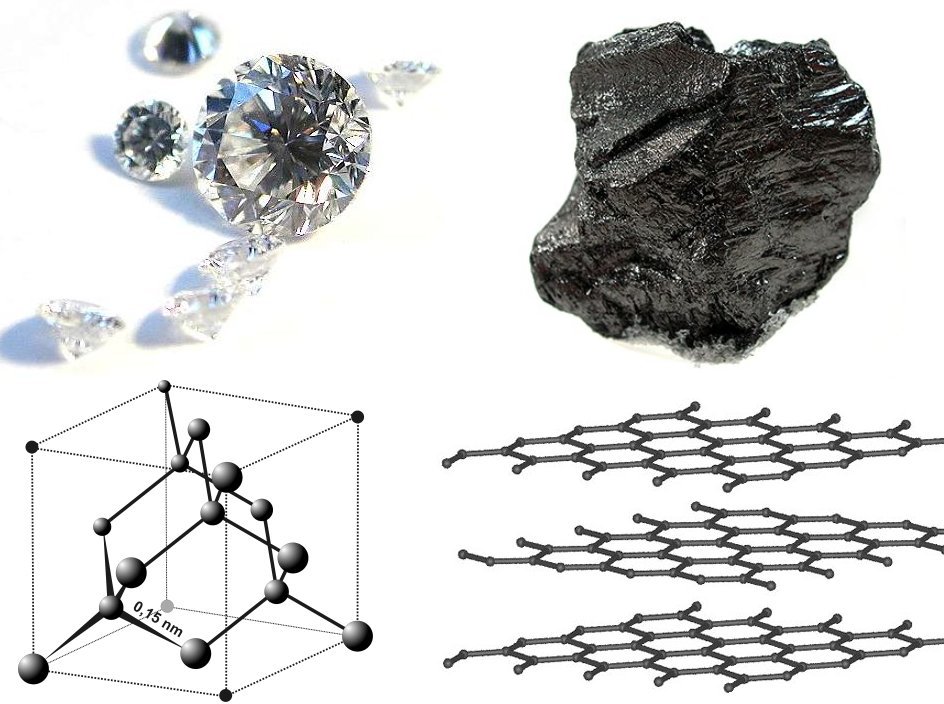

The earliest structures were simple inorganic crystals and minerals, but even these revealed fundamental laws of physics and chemistry. The first atomic-resolution structure to be "solved" (i.e., determined) in 1914 was that of

table salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as ro ...

. The distribution of electrons in the table-salt structure showed that crystals are not necessarily composed of

covalently bonded molecules, and proved the existence of

ionic compound

In chemistry, a salt or ionic compound is a chemical compound consisting of an assembly of positively charged ions (Cation, cations) and negatively charged ions (Anion, anions), which results in a compound with no net electric charge (electrica ...

s. The structure of diamond was solved in the same year,

proving the tetrahedral arrangement of its chemical bonds and showing that the length of C–C single bond was about 1.52 angstroms. Other early structures included copper,

calcium fluoride

Calcium fluoride is the inorganic compound of the elements calcium and fluorine with the formula CaF2. It is a white solid that is practically insoluble in water. It occurs as the mineral fluorite (also called fluorspar), which is often deeply col ...

(CaF

2, also known as ''fluorite''),

calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

(CaCO

3) and

pyrite

The mineral pyrite ( ), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue ...

(FeS

2)

in 1914;

spinel

Spinel () is the magnesium/aluminium member of the larger spinel group of minerals. It has the formula in the cubic crystal system. Its name comes from the Latin word , a diminutive form of ''spine,'' in reference to its pointed crystals.

Prop ...

(MgAl

2O

4) in 1915; the

rutile

Rutile is an oxide mineral composed of titanium dioxide (TiO2), the most common natural form of TiO2. Rarer polymorphs of TiO2 are known, including anatase, akaogiite, and brookite.

Rutile has one of the highest refractive indices at vis ...

and

anatase

Anatase is a metastable mineral form of titanium dioxide (TiO2) with a Tetragonal crystal system, tetragonal crystal structure. Although colorless or white when pure, anatase in nature is usually a black solid due to impurities. Three other Pol ...

forms of

titanium dioxide

Titanium dioxide, also known as titanium(IV) oxide or titania , is the inorganic compound derived from titanium with the chemical formula . When used as a pigment, it is called titanium white, Pigment White 6 (PW6), or Colour Index Internationa ...

(TiO

2) in 1916;

pyrochroite (Mn(OH)

2) and, by extension,

brucite

Brucite is the mineral form of magnesium hydroxide, with the chemical formula Magnesium, Mg(hydroxyl, OH)2. It is a common alteration product of periclase in marble; a low-temperature hydrothermal Vein (geology), vein mineral in metamorphosed li ...

(Mg(OH)

2) in 1919. Also in 1919,

sodium nitrate

Sodium nitrate is the chemical compound with the chemical formula, formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt (chemistry), salt is also known as Chile saltpeter (large deposits of which were historically mined in Chile) to distinguish it from ordi ...

(NaNO

3) and caesium dichloroiodide (CsICl

2) were determined by

Ralph Walter Graystone Wyckoff, and the

wurtzite

Wurtzite is a zinc and iron sulfide mineral with the chemical formula , a less frequently encountered Polymorphism (materials science), structural polymorph form of sphalerite. The iron content is variable up to eight percent.Palache, Charles, H ...

(hexagonal ZnS) structure was determined in 1920.

The structure of

graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

was solved in 1916 by the related method of

powder diffraction

Powder diffraction is a scientific technique using X-ray, neutron, or electron diffraction on powder or microcrystalline samples for structural characterization of materials. An instrument dedicated to performing such powder measurements is ca ...

, which was developed by

Peter Debye

Peter Joseph William Debye ( ; born Petrus Josephus Wilhelmus Debije, ; March 24, 1884 – November 2, 1966) was a Dutch-American physicist and physical chemist, and Nobel laureate in Chemistry.

Biography

Early life

Born in Maastricht, Neth ...

and

Paul Scherrer and, independently, by

Albert Hull in 1917. The structure of graphite was determined from single-crystal diffraction in 1924 by two groups independently. Hull also used the powder method to determine the structures of various metals, such as iron and magnesium.

Contributions in different areas

Chemistry

X-ray crystallography has led to a better understanding of

chemical bond

A chemical bond is the association of atoms or ions to form molecules, crystals, and other structures. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds or through the sharing of electrons a ...

s and

non-covalent interactions

In chemistry, a non-covalent interaction differs from a covalent bond in that it does not involve the sharing of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions between molecules or within a molecule. The ...

. The initial studies revealed the typical radii of atoms, and confirmed many theoretical models of chemical bonding, such as the tetrahedral bonding of carbon in the diamond structure,

the octahedral bonding of metals observed in ammonium hexachloroplatinate (IV), and the resonance observed in the planar carbonate group

and in aromatic molecules.

's 1928 structure of

hexamethylbenzene established the hexagonal symmetry of

benzene

Benzene is an Organic compound, organic chemical compound with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar hexagonal Ring (chemistry), ring with one hyd ...

and showed a clear difference in bond length between the aliphatic C–C bonds and aromatic C–C bonds; this finding led to the idea of

resonance

Resonance is a phenomenon that occurs when an object or system is subjected to an external force or vibration whose frequency matches a resonant frequency (or resonance frequency) of the system, defined as a frequency that generates a maximu ...

between chemical bonds, which had profound consequences for the development of chemistry. Her conclusions were anticipated by

William Henry Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist and X-ray crystallographer who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nobel Prize (in any fiel ...

, who published models of

naphthalene

Naphthalene is an organic compound with formula . It is the simplest polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, and is a white Crystal, crystalline solid with a characteristic odor that is detectable at concentrations as low as 0.08 Parts-per notation ...

and

anthracene

Anthracene is a solid polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) of formula C14H10, consisting of three fused benzene rings. It is a component of coal tar. Anthracene is used in the production of the red dye alizarin and other dyes, as a scintil ...

in 1921 based on other molecules, an early form of

molecular replacement

Molecular replacement (MR) is a method of solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography. MR relies upon the existence of a previously solved protein structure which is similar to our unknown structure from which the diffraction data is deriv ...

.

The first structure of an organic compound,

hexamethylenetetramine

Hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), also known as 1,3,5,7-tetraazaadamantane, is a heterocyclic organic compound with diverse applications. It has the chemical formula (CH2)6N4 and is a white crystalline compound that is highly soluble in water and p ...

, was solved in 1923. This was rapidly followed by several studies of different long-chain

fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s, which are an important component of

biological membranes. In the 1930s, the structures of much larger molecules with two-dimensional complexity began to be solved. A significant advance was the structure of

phthalocyanine

Phthalocyanine () is a large, aromatic, macrocyclic, organic compound with the formula and is of theoretical or specialized interest in chemical dyes and photoelectricity.

It is composed of four isoindole units linked by a ring of nitrogen ato ...

, a large planar molecule that is closely related to

porphyrin molecules important in biology, such as

heme

Heme (American English), or haem (Commonwealth English, both pronounced /Help:IPA/English, hi:m/ ), is a ring-shaped iron-containing molecule that commonly serves as a Ligand (biochemistry), ligand of various proteins, more notably as a Prostheti ...

,

corrin

Corrin is a heterocyclic compound. Although not known to exist on its own, the molecule is of interest as the parent macrocycle related to the cofactor and chromophore in vitamin B12. Its name reflects that it is the "core" of vitamin B12 (co ...

and

chlorophyll

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (, "pale green") and (, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy ...

.

In the 1920s,

Victor Moritz Goldschmidt and later

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

developed rules for eliminating chemically unlikely structures and for determining the relative sizes of atoms. These rules led to the structure of

brookite

Brookite is the Orthorhombic crystal system, orthorhombic variant of titanium dioxide (TiO2), which occurs in four known natural Polymorphism (materials science), polymorphic forms (minerals with the same composition but different structure). The ...

(1928) and an understanding of the relative stability of the

rutile

Rutile is an oxide mineral composed of titanium dioxide (TiO2), the most common natural form of TiO2. Rarer polymorphs of TiO2 are known, including anatase, akaogiite, and brookite.

Rutile has one of the highest refractive indices at vis ...

,

brookite

Brookite is the Orthorhombic crystal system, orthorhombic variant of titanium dioxide (TiO2), which occurs in four known natural Polymorphism (materials science), polymorphic forms (minerals with the same composition but different structure). The ...

and

anatase

Anatase is a metastable mineral form of titanium dioxide (TiO2) with a Tetragonal crystal system, tetragonal crystal structure. Although colorless or white when pure, anatase in nature is usually a black solid due to impurities. Three other Pol ...

forms of

titanium dioxide

Titanium dioxide, also known as titanium(IV) oxide or titania , is the inorganic compound derived from titanium with the chemical formula . When used as a pigment, it is called titanium white, Pigment White 6 (PW6), or Colour Index Internationa ...

.

The distance between two bonded atoms is a sensitive measure of the bond strength and its

bond order

In chemistry, bond order is a formal measure of the multiplicity of a covalent bond between two atoms. As introduced by Gerhard Herzberg, building off of work by R. S. Mulliken and Friedrich Hund, bond order is defined as the difference between t ...

; thus, X-ray crystallographic studies have led to the discovery of even more exotic types of bonding in

inorganic chemistry

Inorganic chemistry deals with chemical synthesis, synthesis and behavior of inorganic compound, inorganic and organometallic chemistry, organometallic compounds. This field covers chemical compounds that are not carbon-based, which are the subj ...

, such as metal-metal double bonds, metal-metal quadruple bonds, and

three-center, two-electron bonds. X-ray crystallography—or, strictly speaking, an inelastic

Compton scattering

Compton scattering (or the Compton effect) is the quantum theory of high frequency photons scattering following an interaction with a charged particle, usually an electron. Specifically, when the photon hits electrons, it releases loosely bound e ...

experiment—has also provided evidence for the partly covalent character of

hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s. In the field of

organometallic chemistry

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and so ...

, the X-ray structure of

ferrocene

Ferrocene is an organometallic chemistry, organometallic compound with the formula . The molecule is a Cyclopentadienyl complex, complex consisting of two Cyclopentadienyl anion, cyclopentadienyl rings sandwiching a central iron atom. It is an o ...

initiated scientific studies of

sandwich compounds, while that of

Zeise's salt

Zeise's salt, potassium trichloro(ethylene)platinate(II) hydrate, is the chemical compound with the formula K platinum.html" ;"title="/nowiki>platinum">PtCl3(C2H4)�H2O. The anion of this air-stable, yellow, coordination complex contains an hapt ...

stimulated research into "back bonding" and metal-pi complexes. Finally, X-ray crystallography had a pioneering role in the development of

supramolecular chemistry

Supramolecular chemistry refers to the branch of chemistry concerning Chemical species, chemical systems composed of a integer, discrete number of molecules. The strength of the forces responsible for spatial organization of the system range from w ...

, particularly in clarifying the structures of the

crown ether

In organic chemistry, crown ethers are cyclic chemical compounds that consist of a ring containing several ether groups (). The most common crown ethers are cyclic oligomers of ethylene oxide, the repeating unit being ethyleneoxy, i.e., . Impor ...

s and the principles of

host–guest chemistry

In supramolecular chemistry, host–guest chemistry describes inclusion compound, complexes that are composed of two or more molecules or ions that are held together in unique structural relationships by forces other than those of full covalent bo ...

.

Materials science and mineralogy

The application of X-ray crystallography to

mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

began with the structure of

garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

Garnet minerals, while sharing similar physical and crystallographic properties, exhibit a wide range of chemical compositions, de ...

, which was determined in 1924 by Menzer. A systematic X-ray crystallographic study of the

silicate

A silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is also used ...

s was undertaken in the 1920s. This study showed that, as the

Si/

O ratio is altered, the silicate crystals exhibit significant changes in their atomic arrangements. Machatschki extended these insights to minerals in which aluminium substitutes for the

silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

atoms of the silicates. The first application of X-ray crystallography to

metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

also occurred in the mid-1920s. Most notably,

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

's structure of the alloy Mg

2Sn led to his theory of the stability and structure of complex ionic crystals. Many complicated

inorganic

An inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bondsthat is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as '' inorganic chemistry''.

Inor ...

and

organometallic

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and so ...

systems have been analyzed using single-crystal methods, such as

fullerene

A fullerene is an allotropes of carbon, allotrope of carbon whose molecules consist of carbon atoms connected by single and double bonds so as to form a closed or partially closed mesh, with fused rings of five to six atoms. The molecules may ...

s,

metalloporphyrins, and other complicated compounds. Single-crystal diffraction is also used in the

pharmaceutical industry

The pharmaceutical industry is a medical industry that discovers, develops, produces, and markets pharmaceutical goods such as medications and medical devices. Medications are then administered to (or self-administered by) patients for curing ...

. The

Cambridge Structural Database

The Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) is both a repository and a validated and curated resource for the three-dimensional structural data of molecules generally containing at least carbon and hydrogen, comprising a wide range of organic, metal ...

contains over 1,000,000 structures as of June 2019; most of these structures were determined by X-ray crystallography.

On October 17, 2012, the

Curiosity rover

''Curiosity'' is a car-sized Mars rover Space exploration, exploring Gale (crater), Gale crater and Mount Sharp on Mars as part of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission. ''Curiosity'' was launched from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station ...

on the

planet Mars at "

Rocknest" performed the first X-ray diffraction analysis of

Martian soil. The results from the rover's

CheMin analyzer revealed the presence of several minerals, including

feldspar

Feldspar ( ; sometimes spelled felspar) is a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagiocl ...

,

pyroxenes

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated Px) are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents ions of calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe( ...

and

olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron Silicate minerals, silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of Nesosilicates, nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle, it is a com ...

, and suggested that the Martian soil in the sample was similar to the "weathered

basaltic soils" of

Hawaiian volcanoes.

Biological macromolecular crystallography

X-ray crystallography of biological molecules took off with

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, who solved the structures of

cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

(1937),

penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

(1946) and

vitamin B12 (1956), for which she was awarded the

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

in 1964. In 1969, she succeeded in solving the structure of

insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

, on which she worked for over thirty years.

Crystal structures of proteins (which are irregular and hundreds of times larger than cholesterol) began to be solved in the late 1950s, beginning with the structure of

sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle, skeletal Muscle, muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compar ...

by

Sir John Cowdery Kendrew, for which he shared the

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

with

Max Perutz

Max Ferdinand Perutz (19 May 1914 – 6 February 2002) was an Austrian-born British molecular biologist, who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with John Kendrew, for their studies of the structures of haemoglobin and myoglobin. He went ...

in 1962. Since that success, 190,000 X-ray crystal structures of proteins, nucleic acids and other biological molecules have been determined. The nearest competing method in number of structures analyzed is

nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, which has resolved less than one tenth as many. Crystallography can solve structures of arbitrarily large molecules, whereas solution-state NMR is restricted to relatively small ones (less than 70 k

Da). X-ray crystallography is used routinely to determine how a pharmaceutical drug interacts with its protein target and what changes might improve it. However, intrinsic

membrane protein

Membrane proteins are common proteins that are part of, or interact with, biological membranes. Membrane proteins fall into several broad categories depending on their location. Integral membrane proteins are a permanent part of a cell membrane ...

s remain challenging to crystallize because they require detergents or other

denaturants to solubilize them in isolation, and such detergents often interfere with crystallization. Membrane proteins are a large component of the

genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, and include many proteins of great physiological importance, such as

ion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by Gating (electrophysiol ...

s and

receptors

Receptor may refer to:

*Sensory receptor, in physiology, any neurite structure that, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and responds ...

.

Helium cryogenics are used to prevent radiation damage in protein crystals.

Methods

Overview

Two limiting cases of X-ray crystallography—"small-molecule" (which includes continuous inorganic solids) and "macromolecular" crystallography—are often used. Small-molecule crystallography typically involves crystals with fewer than 100 atoms in their

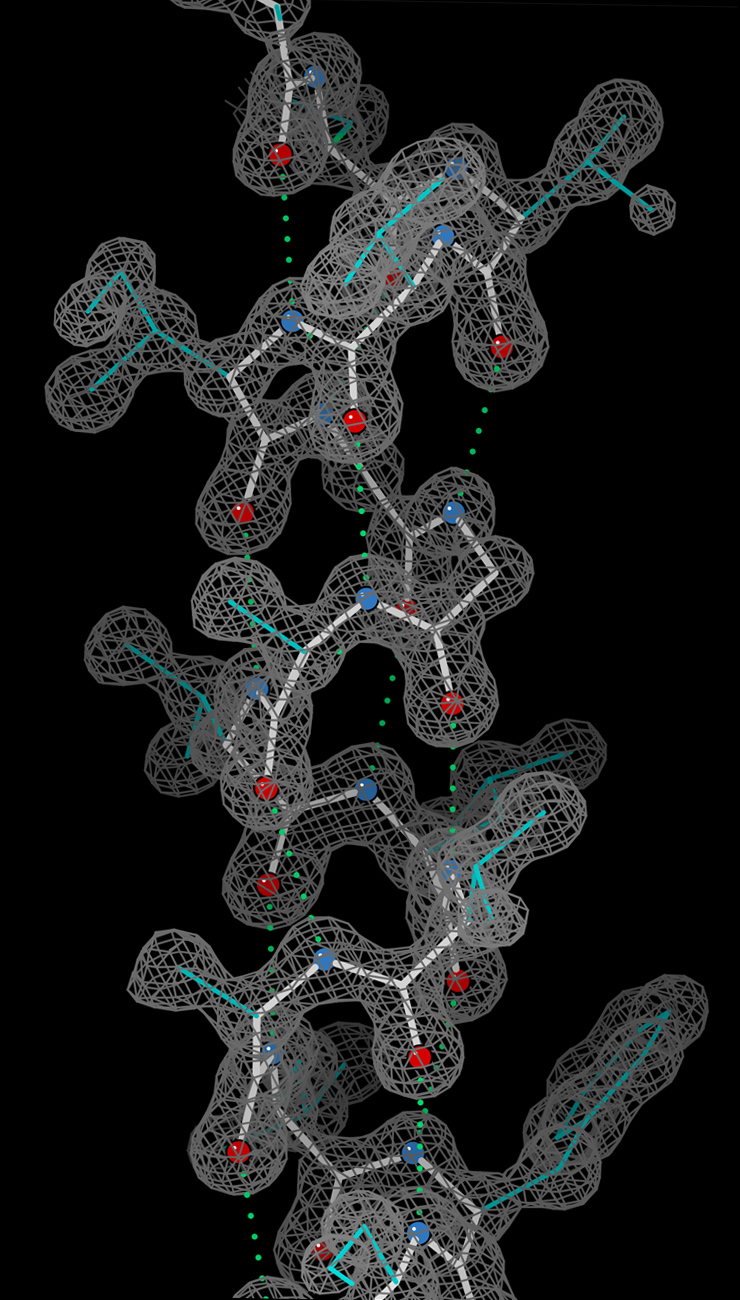

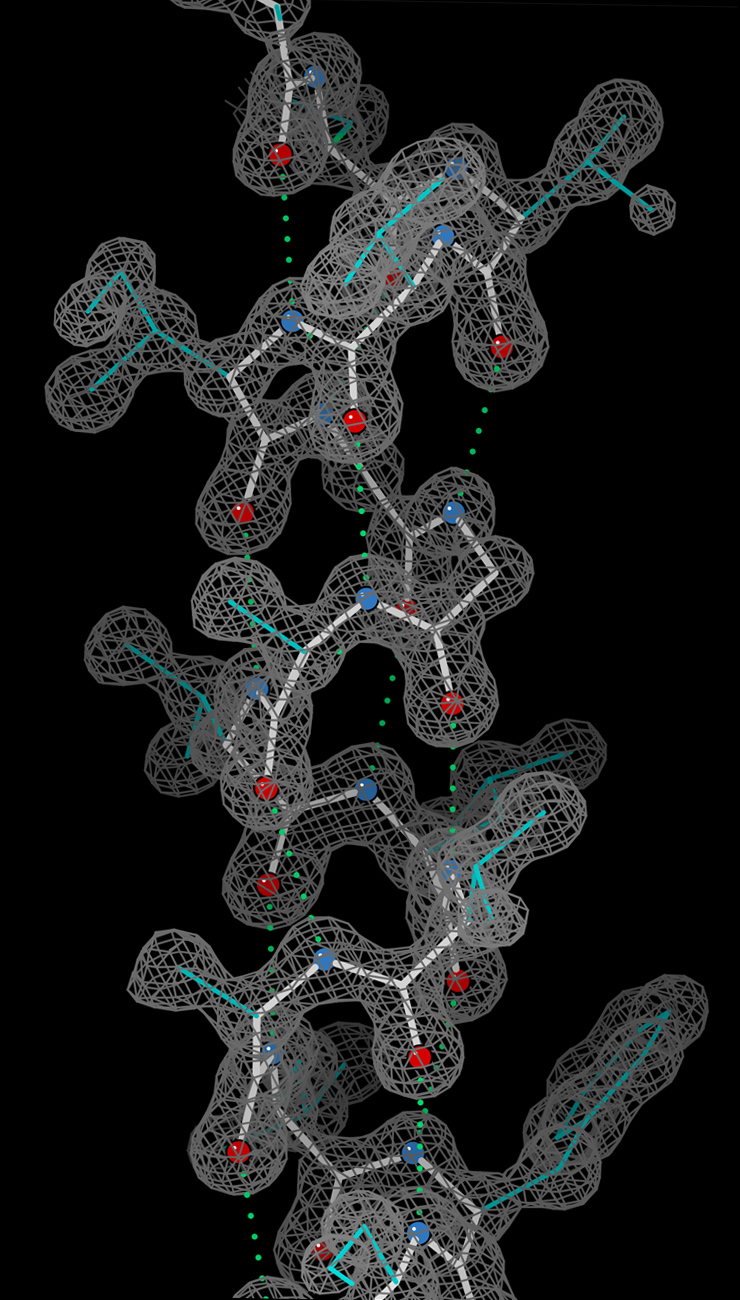

asymmetric unit; such crystal structures are usually so well resolved that the atoms can be discerned as isolated "blobs" of electron density. In contrast, macromolecular crystallography often involves tens of thousands of atoms in the unit cell. Such crystal structures are generally less well-resolved; the atoms and chemical bonds appear as tubes of electron density, rather than as isolated atoms. In general, small molecules are also easier to crystallize than macromolecules; however, X-ray crystallography has proven possible even for viruses and proteins with hundreds of thousands of atoms, through improved crystallographic imaging and technology.

The technique of single-crystal X-ray crystallography has three basic steps. The first—and often most difficult—step is to obtain an adequate crystal of the material under study. The crystal should be sufficiently large (typically larger than 0.1 mm in all dimensions), pure in composition and regular in structure, with no significant internal

imperfections such as cracks or

twinning.

In the second step, the crystal is placed in an intense beam of X-rays, usually of a single wavelength (''monochromatic X-rays''), producing the regular pattern of reflections. The angles and intensities of diffracted X-rays are measured, with each compound having a unique diffraction pattern. As the crystal is gradually rotated, previous reflections disappear and new ones appear; the intensity of every spot is recorded at every orientation of the crystal. Multiple data sets may have to be collected, with each set covering slightly more than half a full rotation of the crystal and typically containing tens of thousands of reflections.

In the third step, these data are combined computationally with complementary chemical information to produce and refine a model of the arrangement of atoms within the crystal. The final, refined model of the atomic arrangement—now called a ''

crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat ...

''—is usually stored in a public database.

Crystallization

Although crystallography can be used to characterize the disorder in an impure or irregular crystal, crystallography generally requires a pure crystal of high regularity to solve the structure of a complicated arrangement of atoms. Pure, regular crystals can sometimes be obtained from natural or synthetic materials, such as samples of metals, minerals or other macroscopic materials. The regularity of such crystals can sometimes be improved with macromolecular crystal

annealing and other methods. However, in many cases, obtaining a diffraction-quality crystal is the chief barrier to solving its atomic-resolution structure.

Small-molecule and macromolecular crystallography differ in the range of possible techniques used to produce diffraction-quality crystals. Small molecules generally have few degrees of conformational freedom, and may be crystallized by a wide range of methods, such as

chemical vapor deposition

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) is a vacuum deposition method used to produce high-quality, and high-performance, solid materials. The process is often used in the semiconductor industry to produce thin films.

In typical CVD, the wafer (electro ...

and

recrystallization. By contrast, macromolecules generally have many degrees of freedom and their crystallization must be carried out so as to maintain a stable structure. For example, proteins and larger

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

molecules cannot be crystallized if their tertiary structure has been

unfolded; therefore, the range of crystallization conditions is restricted to solution conditions in which such molecules remain folded.

Protein crystals are almost always grown in solution. The most common approach is to lower the solubility of its component molecules very gradually; if this is done too quickly, the molecules will precipitate from solution, forming a useless dust or amorphous gel on the bottom of the container. Crystal growth in solution is characterized by two steps: ''nucleation'' of a microscopic crystallite (possibly having only 100 molecules), followed by ''growth'' of that crystallite, ideally to a diffraction-quality crystal. The solution conditions that favor the first step (nucleation) are not always the same conditions that favor the second step (subsequent growth). The solution conditions should ''disfavor'' the first step (nucleation) but ''favor'' the second (growth), so that only one large crystal forms per droplet. If nucleation is favored too much, a shower of small crystallites will form in the droplet, rather than one large crystal; if favored too little, no crystal will form whatsoever. Other approaches involve crystallizing proteins under oil, where aqueous protein solutions are dispensed under liquid oil, and water evaporates through the layer of oil. Different oils have different evaporation permeabilities, therefore yielding changes in concentration rates from different percipient/protein mixture.

It is difficult to predict good conditions for nucleation or growth of well-ordered crystals. In practice, favorable conditions are identified by ''screening''; a very large batch of the molecules is prepared, and a wide variety of crystallization solutions are tested. Hundreds, even thousands, of solution conditions are generally tried before finding the successful one. The various conditions can use one or more physical mechanisms to lower the solubility of the molecule; for example, some may change the pH, some contain salts of the

Hofmeister series

The Hofmeister series or lyotropic series is a classification of ions in order of their lyotrophic properties, which is the ability to salt out or salt in proteins. The effects of these changes were first worked out by Franz Hofmeister, who s ...

or chemicals that lower the dielectric constant of the solution, and still others contain large polymers such as

polyethylene glycol

Polyethylene glycol (PEG; ) is a polyether compound derived from petroleum with many applications, from industrial manufacturing to medicine. PEG is also known as polyethylene oxide (PEO) or polyoxyethylene (POE), depending on its molecular wei ...

that drive the molecule out of solution by entropic effects. It is also common to try several temperatures for encouraging crystallization, or to gradually lower the temperature so that the solution becomes supersaturated. These methods require large amounts of the target molecule, as they use high concentration of the molecule(s) to be crystallized. Due to the difficulty in obtaining such large quantities (

milligrams

The kilogram (also spelled kilogramme) is the base unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI), equal to one thousand grams. It has the unit symbol kg. The word "kilogram" is formed from the combination of the metric prefix kilo- (m ...

) of crystallization-grade protein, robots have been developed that are capable of accurately dispensing crystallization trial drops that are in the order of 100

nanoliters in volume. This means that 10-fold less protein is used per experiment when compared to crystallization trials set up by hand (in the order of 1

microliter).

Several factors are known to inhibit crystallization. The growing crystals are generally held at a constant temperature and protected from shocks or vibrations that might disturb their crystallization. Impurities in the molecules or in the crystallization solutions are often inimical to crystallization. Conformational flexibility in the molecule also tends to make crystallization less likely, due to entropy. Molecules that tend to self-assemble into regular helices are often unwilling to assemble into crystals. Crystals can be marred by

twinning, which can occur when a unit cell can pack equally favorably in multiple orientations; although recent advances in computational methods may allow solving the structure of some twinned crystals. Having failed to crystallize a target molecule, a crystallographer may try again with a slightly modified version of the molecule; even small changes in molecular properties can lead to large differences in crystallization behavior.

Data collection

Mounting the crystal

The crystal is mounted for measurements so that it may be held in the X-ray beam and rotated. There are several methods of mounting. In the past, crystals were loaded into glass capillaries with the crystallization solution (the

mother liquor

The mother liquor (or spent liquor) is the Solution (chemistry), solution remaining after a component has been removed by a process such as filtration or more commonly crystallization. It is encountered in chemical processes including sugar refini ...

). Crystals of small molecules are typically attached with oil or glue to a glass fiber or a loop, which is made of nylon or plastic and attached to a solid rod. Protein crystals are scooped up by a loop, then flash-frozen with

liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen (LN2) is nitrogen in a liquid state at cryogenics, low temperature. Liquid nitrogen has a boiling point of about . It is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquid air. It is a colorless, mobile liquid whose vis ...

. This freezing reduces the radiation damage of the X-rays, as well as thermal motion (the Debye-Waller effect). However, untreated protein crystals often crack if flash-frozen; therefore, they are generally pre-soaked in a cryoprotectant solution before freezing. This pre-soak may itself cause the crystal to crack, ruining it for crystallography. Generally, successful cryo-conditions are identified by trial and error.

The capillary or loop is mounted on a

goniometer

A goniometer is an instrument that either measures an angle or allows an object to be rotated to a precise angular position. The term goniometry derives from two Greek words, γωνία (''gōnía'') 'angle' and μέτρον (''métron'') ' me ...

, which allows it to be positioned accurately within the X-ray beam and rotated. Since both the crystal and the beam are often very small, the crystal must be centered within the beam to within ~25 micrometers accuracy, which is aided by a camera focused on the crystal. The most common type of goniometer is the "kappa goniometer", which offers three angles of rotation: the ω angle, which rotates about an axis perpendicular to the beam; the κ angle, about an axis at ~50° to the ω axis; and, finally, the φ angle about the loop/capillary axis. When the κ angle is zero, the ω and φ axes are aligned. The κ rotation allows for convenient mounting of the crystal, since the arm in which the crystal is mounted may be swung out towards the crystallographer. The oscillations carried out during data collection (mentioned below) involve the ω axis only. An older type of goniometer is the four-circle goniometer, and its relatives such as the six-circle goniometer.

Recording the reflections

The relative intensities of the reflections provides information to determine the arrangement of molecules within the crystal in atomic detail. The intensities of these reflections may be recorded with

photographic film

Photographic film is a strip or sheet of transparent film base coated on one side with a gelatin photographic emulsion, emulsion containing microscopically small light-sensitive silver halide crystals. The sizes and other characteristics of the ...

, an area detector (such as a

pixel detector) or with a

charge-coupled device

A charge-coupled device (CCD) is an integrated circuit containing an array of linked, or coupled, capacitors. Under the control of an external circuit, each capacitor can transfer its electric charge to a neighboring capacitor. CCD sensors are a ...

(CCD) image sensor. The peaks at small angles correspond to low-resolution data, whereas those at high angles represent high-resolution data; thus, an upper limit on the eventual resolution of the structure can be determined from the first few images. Some measures of diffraction quality can be determined at this point, such as the

mosaicity

In crystallography, mosaicity is a measure of the spread of crystal plane orientations. A mosaic crystal is an idealized model of an imperfect crystal, imagined to consist of numerous small perfect crystals (crystallites) that are to some extent ra ...

of the crystal and its overall disorder, as observed in the peak widths. Some pathologies of the crystal that would render it unfit for solving the structure can also be diagnosed quickly at this point.

One set of spots is insufficient to reconstruct the whole crystal; it represents only a small slice of the full three dimensional set. To collect all the necessary information, the crystal must be rotated step-by-step through 180°, with an image recorded at every step; actually, slightly more than 180° is required to cover

reciprocal space

Reciprocal lattice is a concept associated with solids with translational symmetry which plays a major role in many areas such as X-ray diffraction, X-ray and Electron diffraction, electron diffraction as well as the Electronic band structure, e ...

, due to the curvature of the

Ewald sphere. However, if the crystal has a higher symmetry, a smaller angular range such as 90° or 45° may be recorded. The rotation axis should be changed at least once, to avoid developing a "blind spot" in reciprocal space close to the rotation axis. It is customary to rock the crystal slightly (by 0.5–2°) to catch a broader region of reciprocal space.

Multiple data sets may be necessary for certain

phasing

A phaser is an electronic sound processor used to filter a signal by creating a series of peaks and troughs in the frequency spectrum. The position of the peaks and troughs of the waveform being affected is typically modulated by an intern ...

methods. For example,

multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing requires that the scattering be recorded at least three (and usually four, for redundancy) wavelengths of the incoming X-ray radiation. A single crystal may degrade too much during the collection of one data set, owing to radiation damage; in such cases, data sets on multiple crystals must be taken.

Crystal symmetry, unit cell, and image scaling

The recorded series of two-dimensional diffraction patterns, each corresponding to a different crystal orientation, is converted into a three-dimensional set. Data processing begins with ''indexing'' the reflections. This means identifying the dimensions of the unit cell and which image peak corresponds to which position in reciprocal space. A byproduct of indexing is to determine the symmetry of the crystal, i.e., its ''

space group

In mathematics, physics and chemistry, a space group is the symmetry group of a repeating pattern in space, usually in three dimensions. The elements of a space group (its symmetry operations) are the rigid transformations of the pattern that ...

''. Some space groups can be eliminated from the beginning. For example, reflection symmetries cannot be observed in chiral molecules; thus, only 65 space groups of 230 possible are allowed for protein molecules which are almost always chiral. Indexing is generally accomplished using an ''autoindexing'' routine. Having assigned symmetry, the data is then ''integrated''. This converts the hundreds of images containing the thousands of reflections into a single file, consisting of (at the very least) records of the

Miller index

Miller indices form a notation system in crystallography for lattice planes in crystal (Bravais) lattices.

In particular, a family of lattice planes of a given (direct) Bravais lattice is determined by three integers ''h'', ''k'', and ''� ...

of each reflection, and an intensity for each reflection (at this state the file often also includes error estimates and measures of partiality (what part of a given reflection was recorded on that image)).

A full data set may consist of hundreds of separate images taken at different orientations of the crystal. These have to be merged and scaled using peaks that appear in two or more images (''merging'') and scaling so there is a consistent intensity scale. Optimizing the intensity scale is critical because the relative intensity of the peaks is the key information from which the structure is determined. The repetitive technique of crystallographic data collection and the often high symmetry of crystalline materials cause the diffractometer to record many symmetry-equivalent reflections multiple times. This allows calculating the symmetry-related

R-factor, a reliability index based upon how similar are the measured intensities of symmetry-equivalent reflections, thus assessing the quality of the data.

Initial phasing

The intensity of each diffraction 'spot' is proportional to the modulus squared of the

structure factor

In condensed matter physics and crystallography, the static structure factor (or structure factor for short) is a mathematical description of how a material scatters incident radiation. The structure factor is a critical tool in the interpretation ...

. The structure factor is a

complex number

In mathematics, a complex number is an element of a number system that extends the real numbers with a specific element denoted , called the imaginary unit and satisfying the equation i^= -1; every complex number can be expressed in the for ...

containing information relating to both the

amplitude

The amplitude of a periodic variable is a measure of its change in a single period (such as time or spatial period). The amplitude of a non-periodic signal is its magnitude compared with a reference value. There are various definitions of am ...

and

phase

Phase or phases may refer to:

Science

*State of matter, or phase, one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist

*Phase (matter), a region of space throughout which all physical properties are essentially uniform

*Phase space, a mathematica ...

of a

wave

In physics, mathematics, engineering, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance (change from List of types of equilibrium, equilibrium) of one or more quantities. ''Periodic waves'' oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium ...

. In order to obtain an interpretable ''electron density map'', both amplitude and phase must be known (an electron density map allows a crystallographer to build a starting model of the molecule). The phase cannot be directly recorded during a diffraction experiment: this is known as the

phase problem

In physics, the phase problem is the problem of loss of information concerning the phase that can occur when making a physical measurement. The name comes from the field of X-ray crystallography, where the phase problem has to be solved for the de ...

. Initial phase estimates can be obtained in a variety of ways:

* ''

Ab initio

( ) is a Latin term meaning "from the beginning" and is derived from the Latin ("from") + , ablative singular of ("beginning").

Etymology

, from Latin, literally "from the beginning", from ablative case of "entrance", "beginning", related t ...

'' phasing or

direct methods – This is usually the method of choice for small molecules (<1000 non-hydrogen atoms), and has been used successfully to solve the phase problems for small proteins. If the resolution of the data is better than 1.4 Å (140

pm),

direct methods can be used to obtain phase information, by exploiting known phase relationships between certain groups of reflections.

*

Molecular replacement

Molecular replacement (MR) is a method of solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography. MR relies upon the existence of a previously solved protein structure which is similar to our unknown structure from which the diffraction data is deriv ...

– if a related structure is known, it can be used as a search model in molecular replacement to determine the orientation and position of the molecules within the unit cell. The phases obtained this way can be used to generate electron density maps.

*

Anomalous X-ray scattering (''

MAD or

SAD phasing'') – the X-ray wavelength may be scanned past an absorption edge of an atom, which changes the scattering in a known way. By recording full sets of reflections at three different wavelengths (far below, far above and in the middle of the absorption edge) one can solve for the substructure of the anomalously diffracting atoms and hence the structure of the whole molecule. The most popular method of incorporating anomalous scattering atoms into proteins is to express the protein in a

methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans.

As the precursor of other non-essential amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine play ...

auxotroph (a host incapable of synthesizing methionine) in a media rich in seleno-methionine, which contains

selenium

Selenium is a chemical element; it has symbol (chemistry), symbol Se and atomic number 34. It has various physical appearances, including a brick-red powder, a vitreous black solid, and a grey metallic-looking form. It seldom occurs in this elem ...

atoms. A multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) experiment can then be conducted around the absorption edge, which should then yield the position of any methionine residues within the protein, providing initial phases.

* Heavy atom methods (

multiple isomorphous replacement) – If electron-dense metal atoms can be introduced into the crystal,

direct methods or

Patterson-space methods can be used to determine their location and to obtain initial phases. Such heavy atoms can be introduced either by soaking the crystal in a heavy atom-containing solution, or by co-crystallization (growing the crystals in the presence of a heavy atom). As in multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing, the changes in the scattering amplitudes can be interpreted to yield the phases. Although this is the original method by which protein crystal structures were solved, it has largely been superseded by multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing with selenomethionine.

Model building and phase refinement

Having obtained initial phases, an initial model can be built. The atomic positions in the model and their respective

Debye-Waller factors (or B-factors, accounting for the thermal motion of the atom) can be refined to fit the observed diffraction data, ideally yielding a better set of phases. A new model can then be fit to the new electron density map and successive rounds of refinement are carried out. This iterative process continues until the correlation between the diffraction data and the model is maximized. The agreement is measured by an

''R''-factor defined as

:

where ''F'' is the

structure factor

In condensed matter physics and crystallography, the static structure factor (or structure factor for short) is a mathematical description of how a material scatters incident radiation. The structure factor is a critical tool in the interpretation ...

. A similar quality criterion is ''R''

free, which is calculated from a subset (~10%) of reflections that were not included in the structure refinement. Both ''R'' factors depend on the resolution of the data. As a rule of thumb, ''R''

free should be approximately the resolution in angstroms divided by 10; thus, a data-set with 2 Å resolution should yield a final ''R''

free ~ 0.2. Chemical bonding features such as stereochemistry, hydrogen bonding and distribution of bond lengths and angles are complementary measures of the model quality. In iterative model building, it is common to encounter phase bias or model bias: because phase estimations come from the model, each round of calculated map tends to show density wherever the model has density, regardless of whether there truly is a density. This problem can be mitigated by maximum-likelihood weighting and checking using ''omit maps''.

It may not be possible to observe every atom in the asymmetric unit. In many cases,

crystallographic disorder smears the electron density map. Weakly scattering atoms such as hydrogen are routinely invisible. It is also possible for a single atom to appear multiple times in an electron density map, e.g., if a protein sidechain has multiple (<4) allowed conformations. In still other cases, the crystallographer may detect that the covalent structure deduced for the molecule was incorrect, or changed. For example, proteins may be cleaved or undergo post-translational modifications that were not detected prior to the crystallization.

Disorder

A common challenge in refinement of crystal structures results from crystallographic disorder. Disorder can take many forms but in general involves the coexistence of two or more species or conformations. Failure to recognize disorder results in flawed interpretation. Pitfalls from improper modeling of disorder are illustrated by the discounted hypothesis of

bond stretch isomerism. Disorder is modelled with respect to the relative population of the components, often only two, and their identity. In structures of large molecules and ions, solvent and counterions are often disordered.

Applied computational data analysis

The use of computational methods for the powder X-ray diffraction data analysis is now generalized. It typically compares the experimental data to the simulated diffractogram of a model structure, taking into account the instrumental parameters, and refines the structural or microstructural parameters of the model using

least squares

The method of least squares is a mathematical optimization technique that aims to determine the best fit function by minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed values and the predicted values of the model. The me ...

based minimization algorithm. Most available tools allowing phase identification and structural refinement are based on the

Rietveld method, some of them being open and free software such as FullProf Suite, Jana2006, MAUD, Rietan, GSAS, etc. while others are available under commercial licenses such as Diffrac.Suite TOPAS, Match!, etc. Most of these tools also allow

Le Bail refinement (also referred to as profile matching), that is, refinement of the cell parameters based on the Bragg peaks positions and peak profiles, without taking into account the crystallographic structure by itself. More recent tools allow the refinement of both structural and microstructural data, such as the FAULTS program included in the FullProf Suite, which allows the refinement of structures with planar defects (e.g. stacking faults, twinnings, intergrowths).

Deposition of the structure

Once the model of a molecule's structure has been finalized, it is often deposited in a

crystallographic database such as the

Cambridge Structural Database

The Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) is both a repository and a validated and curated resource for the three-dimensional structural data of molecules generally containing at least carbon and hydrogen, comprising a wide range of organic, metal ...

(for small molecules), the

Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) (for inorganic compounds) or the

Protein Data Bank

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) is a database for the three-dimensional structural data of large biological molecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, which is overseen by the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB). This structural data is obtained a ...

(for protein and sometimes nucleic acids). Many structures obtained in private commercial ventures to crystallize medicinally relevant proteins are not deposited in public crystallographic databases.

Contribution of women to X-ray crystallography

A number of women were pioneers in X-ray crystallography at a time when they were excluded from most other branches of physical science.

Kathleen Lonsdale was a research student of

William Henry Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist and X-ray crystallographer who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nobel Prize (in any fiel ...

, who had 11 women research students out of a total of 18. She is known for both her experimental and theoretical work. Lonsdale joined his crystallography research team at the

Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

in London in 1923, and after getting married and having children, went back to work with Bragg as a researcher. She confirmed the structure of the benzene ring, carried out studies of diamond, was one of the first two women to be elected to the

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1945, and in 1949 was appointed the first female tenured professor of chemistry and head of the Department of crystallography at

University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

. Lonsdale always advocated greater participation of women in science and said in 1970: "Any country that wants to make full use of all its potential scientists and technologists could do so, but it must not expect to get the women quite so simply as it gets the men.... It is utopian, then, to suggest that any country that really wants married women to return to a scientific career, when her children no longer need her physical presence, should make special arrangements to encourage her to do so?". During this period, Lonsdale began a collaboration with William T. Astbury on a set of 230 space group tables which was published in 1924 and became an essential tool for crystallographers.

In 1932

Dorothy Hodgkin