Wolfgang Pauli on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

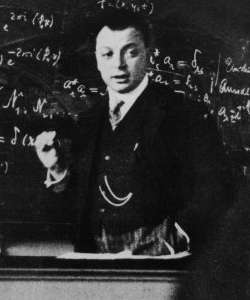

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli ( ; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian

Pauli spent a year at the

Pauli spent a year at the

The Pauli effect was named after his anecdotal bizarre ability to break experimental equipment simply by being in its vicinity. Pauli was aware of his reputation and was delighted whenever the Pauli effect manifested. These strange occurrences were in line with his controversial investigations into the legitimacy of

The Pauli effect was named after his anecdotal bizarre ability to break experimental equipment simply by being in its vicinity. Pauli was aware of his reputation and was delighted whenever the Pauli effect manifested. These strange occurrences were in line with his controversial investigations into the legitimacy of

Wolfgang Pauli, Carl Jung, and the Acausal Connecting Principle: A Case Study in Transdisciplinarity

'' Disciplines in Dialogue. Pauli and Jung held that this reality was governed by common principles ("

Vol 1: ''Electrodynamics''

Vol 2: ''Optics and the Theory of Electrons''

Vol 3: ''Thermodynamics and the Kinetic Theory of Gases''

Vol 4: ''Statistical Mechanics''

Vol 5: ''Wave Mechanics''

Vol 6: ''Selected Topics in Field Quantization'' *Pauli W, ''Meson Theory of Nuclear Forces'', 2nd ed, Interscience Publishers, 1948. *Pauli W, ''Theory of Relativity'',

Pauli bio

at the University of St Andrews, Scotland

at "Nobel Prize Winners"

* ttp://alsos.wlu.edu/qsearch.aspx?browse=people/Pauli,+Wolfgang Annotated bibliography for Wolfgang Pauli from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Pauli Archives

at CERN Document Server

at ETH-Bibliothek, Zürich

– ''Linus Pauling and the Nature of the Chemical Bond: A Documentary History''

Pauli's letter (December 1930)

, the hypothesis of the neutrino (online and analyzed, for English version click 'Télécharger')

Pauli exclusion principle

with

''Schrödinger in Oxford''

World Scientific Publishing. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Pauli, Wolfgang 1900 births 1958 deaths Nobel laureates in Physics Austrian Nobel laureates Nobel laureates from Austria-Hungary Jewish Nobel laureates 20th-century Austrian physicists Jewish emigrants from Austria after the Anschluss to the United States Deaths from pancreatic cancer in Switzerland Academic staff of ETH Zurich Foreign members of the Royal Society Institute for Advanced Study visiting scholars Jewish American physicists Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Naturalised citizens of Switzerland Lorentz Medal winners Mathematical physicists Quantum physicists Scientists from Vienna Theoretical physicists Thermodynamicists Academic staff of the University of Göttingen Winners of the Max Planck Medal Carl Jung Recipients of the Matteucci Medal Swiss Nobel laureates Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Academic staff of the University of Hamburg Recipients of Franklin Medal

theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain, and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experi ...

and a pioneer of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

"for the discovery of the Exclusion Principle, also called the Pauli Principle

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli exclusion principle (German: Pauli-Ausschlussprinzip) states that two or more identical particles with half-integer spins (i.e. fermions) cannot simultaneously occupy the same quantum state within a system that o ...

". The discovery involved spin theory, which is the basis of a theory of the structure of matter. To preserve the conservation of energy

The law of conservation of energy states that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant; it is said to be Conservation law, ''conserved'' over time. In the case of a Closed system#In thermodynamics, closed system, the principle s ...

in beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

, he posited the existence of a small neutral particle, dubbed the neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is an elementary particle that interacts via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is so small ('' -ino'') that i ...

by Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

. The neutrino was detected in 1956.

Early life

Pauli was born inVienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

to a chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

, (''né'' Wolf Pascheles, 1869–1955), and his wife, Bertha Camilla Schütz; his sister was Hertha Pauli, a writer and actress. Pauli's middle name was given in honor of his godfather, physicist Ernst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach ( ; ; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the understanding of the physics of shock waves. The ratio of the speed of a flow or object to that of ...

. Pauli's paternal grandparents were from prominent Jewish families of Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

; his great-grandfather was the Jewish publisher Wolf Pascheles. Pauli's mother, Bertha Schütz, was raised in her mother's Roman Catholic religion; her father was Jewish writer Friedrich Schütz. Pauli was raised as a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

.

Pauli attended the Döbling

Döbling () is the 19th Districts of Vienna, district in the city of Vienna, Austria (). It is located in the north of Vienna, north of the districts Alsergrund and Währing. Döbling has some heavily populated urban areas with many residential bui ...

er- Gymnasium in Vienna, graduating with distinction in 1918. Two months later, he published his first paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, Textile, rags, poaceae, grasses, Feces#Other uses, herbivore dung, or other vegetable sources in water. Once the water is dra ...

, on Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

's theory of general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of grav ...

. He attended the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich, LMU or LMU Munich; ) is a public university, public research university in Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Originally established as the University of Ingolstadt in 1472 by Duke ...

, working under Arnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in Atomic physics, atomic and Quantum mechanics, quantum physics, and also educated and ...

, where he received his PhD in July 1921 for his thesis on the quantum theory of ionized diatomic hydrogen ().

Career

Sommerfeld asked Pauli to review thetheory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

for the ''Encyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften'' (''Encyclopedia of Mathematical Sciences''). Two months after receiving his doctorate, Pauli completed the article, which came to 237 pages. Einstein praised it; published as a monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

, it remains a standard reference on the subject.

Pauli spent a year at the

Pauli spent a year at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen (, commonly referred to as Georgia Augusta), is a Public university, public research university in the city of Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1734 ...

as the assistant to Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German-British theoretical physicist who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics, and supervised the work of a ...

, and the next year at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

(later the Niels Bohr Institute

The Niels Bohr Institute () is a research institute of the University of Copenhagen. The research of the institute spans astronomy, geophysics, nanotechnology, particle physics, quantum mechanics, and biophysics.

Overview

The institute was foun ...

). From 1923 to 1928, he was a professor at the University of Hamburg

The University of Hamburg (, also referred to as UHH) is a public university, public research university in Hamburg, Germany. It was founded on 28 March 1919 by combining the previous General Lecture System ('':de:Allgemeines Vorlesungswesen, ...

. During this period, Pauli was instrumental in the development of the modern theory of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

. In particular, he formulated the exclusion principle and the theory of nonrelativistic spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spin (physics) or particle spin, a fundamental property of elementary particles

* Spin quantum number, a number which defines the value of a particle's spin

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thr ...

.

In 1928, Pauli was appointed Professor of Theoretical Physics at ETH Zurich

ETH Zurich (; ) is a public university in Zurich, Switzerland. Founded in 1854 with the stated mission to educate engineers and scientists, the university focuses primarily on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. ETH Zurich ran ...

in Switzerland. He was awarded the Lorentz Medal

Lorentz Medal is a distinction awarded every four years by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. It was established in 1925 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the doctorate of Hendrik Lorentz. The medal is given for imp ...

in 1930. He held visiting professorships at the University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

in 1931 and the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry located in Princeton, New Jersey. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholars, including Albert Ein ...

in Princeton in 1935.

Jung

At the end of 1930, shortly after his postulation of theneutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is an elementary particle that interacts via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is so small ('' -ino'') that i ...

and immediately after his divorce and his mother's suicide, Pauli experienced a personal crisis. In January 1932 he consulted psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the school of analytical psychology. A prolific author of Carl Jung publications, over 20 books, illustrator, and corr ...

, who also lived near Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

. Jung immediately began interpreting Pauli's deeply archetypal

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, History of psychology#Emergence of German experimental psychology, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a stat ...

dreams and Pauli became a collaborator of Jung's. He soon began to critique the epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

of Jung's theory scientifically, and this contributed to a certain clarification of Jung's ideas, especially about synchronicity

Synchronicity () is a concept introduced by Carl Jung, founder of analytical psychology, to describe events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection. Jung held that this was a healthy fu ...

. A great many of these discussions are documented in the Pauli/Jung letters, today published as ''Atom and Archetype''. Jung's elaborate analysis of more than 400 of Pauli's dreams is documented in '' Psychology and Alchemy''. In 1933 Pauli published the second part of his book on physics, ''Handbuch der Physik'', which was considered the definitive book on the new field of quantum physics. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

called it "the only adult introduction to quantum mechanics."

The German annexation of Austria in 1938 made Pauli a German citizen, which became a problem for him in 1939 after World War II broke out. In 1940, he tried in vain to obtain Swiss citizenship, which would have allowed him to remain at the ETH.

United States and Switzerland

In 1940, Pauli moved to the United States, where he was employed as a professor of theoretical physics at theInstitute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry located in Princeton, New Jersey. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholars, including Albert Ein ...

. In 1946, after the war, he became a naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

U.S. citizen and returned to Zürich, where he mostly remained for the rest of his life. In 1949, he was granted Swiss citizenship.

In 1958, Pauli was awarded the Max Planck medal

The Max Planck Medal is the highest award of the German Physical Society , the world's largest organization of physicists, for extraordinary achievements in theoretical physics. The prize has been awarded annually since 1929, with few exceptions ...

. The same year, he fell ill with pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cell (biology), cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a Neoplasm, mass. These cancerous cells have the malignant, ability to invade other parts of ...

. When his last assistant, Charles Enz, visited him at the Rotkreuz hospital in Zürich, Pauli asked him, "Did you see the room number?" It was 137. Throughout his life, Pauli had been preoccupied with the question of why the fine-structure constant

In physics, the fine-structure constant, also known as the Sommerfeld constant, commonly denoted by (the Alpha, Greek letter ''alpha''), is a Dimensionless physical constant, fundamental physical constant that quantifies the strength of the el ...

, a dimensionless

Dimensionless quantities, or quantities of dimension one, are quantities implicitly defined in a manner that prevents their aggregation into units of measurement. ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0. Typically expressed as ratios that align with another sy ...

fundamental constant, has a value nearly equal to 1/137. Pauli died in that room on 15 December 1958."By a 'cabalistic' coincidence, Wolfgang Pauli died in room 137 of the Red-Cross hospital at Zurich on 15 December 1958." – Of Mind and Spirit, Selected Essays of Charles Enz, Charles Paul Enz, World Scientific, 2009, , p. 95.

Scientific research

Pauli made many important contributions as a physicist, primarily in the field ofquantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

. He seldom published papers, preferring lengthy correspondences with colleagues such as Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

from the University of Copenhagen

The University of Copenhagen (, KU) is a public university, public research university in Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Founded in 1479, the University of Copenhagen is the second-oldest university in Scandinavia, after Uppsala University.

...

in Denmark and Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg (; ; 5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist, one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics and a principal scientist in the German nuclear program during World War II.

He pub ...

, with whom he had close friendships. Many of his ideas and results were never published and appeared only in his letters, which were often copied and circulated by their recipients. In 1921 Pauli worked with Bohr to create the Aufbau Principle

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, the Aufbau principle (, from ), also called the Aufbau rule, states that in the ground state of an atom or ion, electrons first fill Electron shell#Subshells, subshells of the lowest available energy, the ...

, which described building up electrons in shells based on the German word for building up, as Bohr was also fluent in German.

Pauli proposed in 1924 a new quantum degree of freedom (or quantum number

In quantum physics and chemistry, quantum numbers are quantities that characterize the possible states of the system.

To fully specify the state of the electron in a hydrogen atom, four quantum numbers are needed. The traditional set of quantu ...

) with two possible values, to resolve inconsistencies between observed molecular spectra and the developing theory of quantum mechanics. He formulated the Pauli exclusion principle, perhaps his most important work, which stated that no two electrons could exist in the same quantum state, identified by four quantum numbers including his new two-valued degree of freedom. The idea of spin originated with Ralph Kronig. A year later, George Uhlenbeck

George Eugene Uhlenbeck (December 6, 1900 – October 31, 1988) was a Dutch-American theoretical physicist, known for his significant contributions to quantum mechanics and statistical mechanics. He co-developed the concept of electron spin, alo ...

and Samuel Goudsmit

Samuel Abraham Goudsmit (July 11, 1902 – December 4, 1978) was a Dutch-American physicist famous for jointly proposing the concept of electron spin with George Eugene Uhlenbeck in 1925.

Life and career

Goudsmit was born in The Hague, Ne ...

identified Pauli's new degree of freedom as electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spin (physics) or particle spin, a fundamental property of elementary particles

* Spin quantum number, a number which defines the value of a particle's spin

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thr ...

, in which Pauli for a very long time wrongly refused to believe.

In 1926, shortly after Heisenberg published the matrix theory

In mathematics, a matrix (: matrices) is a rectangular array or table of numbers, symbols, or expressions, with elements or entries arranged in rows and columns, which is used to represent a mathematical object or property of such an object. ...

of modern quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

, Pauli used it to derive the observed spectrum

A spectrum (: spectra or spectrums) is a set of related ideas, objects, or properties whose features overlap such that they blend to form a continuum. The word ''spectrum'' was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of co ...

of the hydrogen atom

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral hydrogen atom contains a single positively charged proton in the nucleus, and a single negatively charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb for ...

. This result was important in securing credibility for Heisenberg's theory.

Pauli introduced the 2×2 Pauli matrices

In mathematical physics and mathematics, the Pauli matrices are a set of three complex matrices that are traceless, Hermitian, involutory and unitary. Usually indicated by the Greek letter sigma (), they are occasionally denoted by tau () ...

as a basis of spin operators, thus solving the nonrelativistic theory of spin. This work, including the Pauli equation

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli equation or Schrödinger–Pauli equation is the formulation of the Schrödinger equation for spin-1/2 particles, which takes into account the interaction of the particle's spin with an external electromagnetic f ...

, is sometimes said to have influenced Paul Dirac

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac ( ; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English mathematician and Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who is considered to be one of the founders of quantum mechanics. Dirac laid the foundations for bot ...

in his creation of the Dirac equation

In particle physics, the Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation derived by British physicist Paul Dirac in 1928. In its free form, or including electromagnetic interactions, it describes all spin-1/2 massive particles, called "Dirac ...

for the relativistic electron, though Dirac said that he invented these same matrices himself independently at the time. Dirac invented similar but larger (4x4) spin matrices for use in his relativistic treatment of fermionic spin.

In 1930, Pauli considered the problem of beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

. In a letter of 4 December to Lise Meitner

Elise Lise Meitner ( ; ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission.

After completing her doctoral research in 1906, Meitner became the second woman ...

''et al.'', beginning, " Dear radioactive ladies and gentlemen", he proposed the existence of a hitherto unobserved neutral particle with a small mass, no greater than 1% the mass of a proton, to explain the continuous spectrum of beta decay. In 1934, Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

incorporated the particle, which he called a neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is an elementary particle that interacts via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is so small ('' -ino'') that i ...

, "little neutral one" in Fermi's native Italian, into his theory of beta decay. The neutrino was first confirmed experimentally in 1956 by Frederick Reines

Frederick Reines ( ; March 16, 1918 – August 26, 1998) was an American physicist. He was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physics for his co-detection of the neutrino with Clyde Cowan in the neutrino experiment. He may be the only scientist in ...

and Clyde Cowan

Clyde Lorrain Cowan Jr (December 6, 1919 – May 24, 1974) was an American physicist and the co-discoverer of the neutrino along with Frederick Reines. The discovery was made in 1956 in the neutrino experiment. Reines received the Nobel Prize in ...

, two and a half years before Pauli's death. On receiving the news, he replied by telegram: "Thanks for message. Everything comes to him who knows how to wait. Pauli."

In 1940, Pauli re-derived the spin-statistics theorem, a critical result of quantum field theory that states that particles with half-integer spin are fermion

In particle physics, a fermion is a subatomic particle that follows Fermi–Dirac statistics. Fermions have a half-integer spin (spin 1/2, spin , Spin (physics)#Higher spins, spin , etc.) and obey the Pauli exclusion principle. These particles i ...

s, while particles with integer spin are boson

In particle physics, a boson ( ) is a subatomic particle whose spin quantum number has an integer value (0, 1, 2, ...). Bosons form one of the two fundamental classes of subatomic particle, the other being fermions, which have half odd-intege ...

s.

In 1949, he published a paper on Pauli–Villars regularization: regularization is the term for techniques that modify infinite mathematical integrals to make them finite during calculations, so that one can identify whether the intrinsically infinite quantities in the theory (mass, charge, wavefunction) form a finite and hence calculable set that can be redefined in terms of their experimental values, which criterion is termed renormalization

Renormalization is a collection of techniques in quantum field theory, statistical field theory, and the theory of self-similar geometric structures, that is used to treat infinities arising in calculated quantities by altering values of the ...

, and which removes infinities from quantum field theories

In theoretical physics, quantum field theory (QFT) is a theoretical framework that combines field theory and the principle of relativity with ideas behind quantum mechanics. QFT is used in particle physics to construct physical models of subatom ...

, but also importantly allows the calculation of higher-order corrections in perturbation theory.

Pauli made repeated criticisms of the modern synthesis of evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes such as natural selection, common descent, and speciation that produced the diversity of life on Earth. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biolo ...

, and his contemporary admirers point to modes of epigenetic inheritance as supporting his arguments.

Paul Drude in 1900 proposed the first theoretical model for a classical electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

moving through a metallic solid. Drude's classical model was also augmented by Pauli and other physicists. Pauli realized that the free electrons in metal must obey the Fermi–Dirac statistics

Fermi–Dirac statistics is a type of quantum statistics that applies to the physics of a system consisting of many non-interacting, identical particles that obey the Pauli exclusion principle. A result is the Fermi–Dirac distribution of part ...

. Using this idea, he developed the theory of paramagnetism

Paramagnetism is a form of magnetism whereby some materials are weakly attracted by an externally applied magnetic field, and form internal, induced magnetic fields in the direction of the applied magnetic field. In contrast with this behavior, ...

in 1926. Pauli said, "Festkörperphysik ist eine Schmutzphysik"—solid-state physics is the physics of dirt.

Pauli was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1953 and president of the Swiss Physical Society

The Swiss Physical Society (SPS) (German: Schweizerische Physikalische Gesellschaft / SPG, French: Société Suisse de Physique / SSP) is a Swiss professional society promoting physics in Switzerland. It was founded in May 1908. SPS is involved in ...

in 1955 for two years. In 1958 he became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (, KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed in the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam.

In addition to various advisory a ...

.

Personality and friendships

The Pauli effect was named after his anecdotal bizarre ability to break experimental equipment simply by being in its vicinity. Pauli was aware of his reputation and was delighted whenever the Pauli effect manifested. These strange occurrences were in line with his controversial investigations into the legitimacy of

The Pauli effect was named after his anecdotal bizarre ability to break experimental equipment simply by being in its vicinity. Pauli was aware of his reputation and was delighted whenever the Pauli effect manifested. These strange occurrences were in line with his controversial investigations into the legitimacy of parapsychology

Parapsychology is the study of alleged psychic phenomena (extrasensory perception, telepathy, teleportation, precognition, clairvoyance, psychokinesis (also called telekinesis), and psychometry (paranormal), psychometry) and other paranormal cla ...

, particularly his collaboration with C. G. Jung on synchronicity

Synchronicity () is a concept introduced by Carl Jung, founder of analytical psychology, to describe events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection. Jung held that this was a healthy fu ...

. Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German-British theoretical physicist who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics, and supervised the work of a ...

considered Pauli "only comparable to Einstein himself... perhaps even greater". Einstein declared Pauli his "spiritual heir".

Pauli was famously a perfectionist. This extended not just to his own work, but also to that of his colleagues. As a result, he became known in the physics community as the "conscience of physics", the critic to whom his colleagues were accountable. He could be scathing in his dismissal of any theory he found lacking, often labelling it ''ganz falsch'', "utterly wrong".

But this was not his most severe criticism, which he reserved for theories or theses so unclearly presented as to be untestable or unevaluatable and thus not properly belonging within the realm of science, even though posing as such. They were worse than wrong because they could not be proved wrong. Famously, he once said of such an unclear paper: "It is not even wrong

"Not even wrong" is a phrase used to describe pseudoscience or bad science. It describes an argument or explanation that purports to be scientific but uses faulty reasoning or speculative premises, which can be neither affirmed nor denied and th ...

!"

His supposed remark when meeting another leading physicist, Paul Ehrenfest

Paul Ehrenfest (; 18 January 1880 – 25 September 1933) was an Austrian Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who made major contributions to statistical mechanics and its relation to quantum physics, quantum mechanics, including the theory ...

, illustrates this notion of an arrogant Pauli. The two met at a conference for the first time. Ehrenfest was familiar with Pauli's papers and quite impressed with them. After a few minutes of conversation, Ehrenfest remarked, "I think I like your Encyclopedia article n relativity theory

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages, and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

better than I like you," to which Pauli retorted, "That's strange. With me, regarding you, it is just the opposite." The two became very good friends from then on.

A somewhat warmer picture emerges from this story, which appears in the article on Dirac:

Werner HeisenbergMany of Pauli's ideas and results were never published and appeared only in his letters, which were often copied and circulated by their recipients. Pauli may have been unconcerned that much of his work thus went uncredited, but when it came to Heisenberg's world-renowned 1958 lecture at Göttingen on their joint work on a unified field theory, and the press release calling Pauli a mere "assistant to Professor Heisenberg", Pauli became offended, denouncing Heisenberg's physics prowess. The deterioration of their relationship resulted in Heisenberg ignoring Pauli's funeral, and writing in his autobiography that Pauli's criticisms were overwrought, though ultimately the field theory was proved untenable, validating Pauli's criticisms.n ''Physics and Beyond'', 1971 N, or n, is the fourteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages, and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''. History ...recollects a friendly conversation among young participants at the 1927Solvay Conference The Solvay Conferences () have been devoted to preeminent unsolved problems in both physics and chemistry. They began with the historic invitation-only 1911 Solvay Conference on Physics, considered a turning point in the world of physics, and ar ..., about Einstein and Planck's views on religion. Wolfgang Pauli, Heisenberg, and Dirac took part in it. Dirac's contribution was a poignant and clear criticism of the political manipulation of religion, that was much appreciated for its lucidity by Bohr, when Heisenberg reported it to him later. Among other things, Dirac said: "I cannot understand why we idle discussing religion. If we are honest – and as scientists honesty is our precise duty – we cannot help but admit that any religion is a pack of false statements, deprived of any real foundation. The very idea of God is a product of human imagination. ... I do not recognize any religious myth, at least because they contradict one another. ... Heisenberg's view was tolerant. Pauli had kept silent, after some initial remarks. But when finally he was asked for his opinion, jokingly he said: "Well, I'd say that also our friend Dirac has got a religion and the first commandment of this religion is 'God does not exist and Paul Dirac is his prophet'". Everybody burst into laughter, including Dirac.

George Gamow

George Gamow (sometimes Gammoff; born Georgiy Antonovich Gamov; ; 4 March 1904 – 19 August 1968) was a Soviet and American polymath, theoretical physicist and cosmologist. He was an early advocate and developer of Georges Lemaître's Big Ba ...

wrote that "it is just as difficult to find the branch of modern physics in which the Pauli Principle is not used as to find a man as gifted, amiable, and amusing as Wolfgang Pauli was."

Philosophy

In his discussions withCarl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the school of analytical psychology. A prolific author of Carl Jung publications, over 20 books, illustrator, and corr ...

, Pauli developed an ontological theory that has been dubbed the "Pauli–Jung Conjecture" and has been seen as a kind of dual-aspect theory. The theory holds that there is "a psychophysically neutral reality" and that mental and physical aspects are derivative of this reality. Pauli thought that elements of quantum physics pointed to a deeper reality that might explain the mind/matter gap and wrote, "we must postulate a cosmic order of nature beyond our control to which ''both'' the outward material objects ''and'' the inward images are subject."Burns, Charlene (2011). Wolfgang Pauli, Carl Jung, and the Acausal Connecting Principle: A Case Study in Transdisciplinarity

'' Disciplines in Dialogue. Pauli and Jung held that this reality was governed by common principles ("

archetype

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main mo ...

s") that appear as psychological phenomena or as physical events.Atmanspacher, Harald and Primas, Hans (1995) ''The Hidden Side of Wolfgang Pauli.'' Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3, No. 2, 1996, pp. 112–26. They also held that synchronicities might reveal some of this underlying reality's workings.

Beliefs

He is considered to have been adeist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

and a mystic. In ''No Time to Be Brief: A Scientific Biography of Wolfgang Pauli'' he is quoted as writing to science historian Shmuel Sambursky

Shmuel Sambursky, or Samuel Sambursky (; 1900-1990) was a German, Palestinian, and Israeli physicist, professor, and author during the respective epochs of his country —Germany, Mandatory Palestine, and Israel.

Early life and migration

Sambursk ...

, "In opposition to the monotheist religions – but in unison with the mysticism of all peoples, including the Jewish mysticism – I believe that the ultimate reality is not personal."

Personal life

In 1929, Pauli married Käthe Margarethe Deppner, a cabaret dancer. The marriage was unhappy, ending in divorce after less than a year. He married again in 1934 to Franziska Bertram (1901–1987). They had no children.Death

Pauli died of pancreatic cancer on 15 December 1958, at age 58.Publications

*Pauli W, ''General Principles of Quantum Mechanics'',Springer

Springer or springers may refer to:

Publishers

* Springer Science+Business Media, aka Springer International Publishing, a worldwide publishing group founded in 1842 in Germany formerly known as Springer-Verlag.

** Springer Nature, a multinationa ...

, 1980.

*Pauli W, ''Lectures on Physics'', 6 vols, Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

, 2000.Vol 1: ''Electrodynamics''

Vol 2: ''Optics and the Theory of Electrons''

Vol 3: ''Thermodynamics and the Kinetic Theory of Gases''

Vol 4: ''Statistical Mechanics''

Vol 5: ''Wave Mechanics''

Vol 6: ''Selected Topics in Field Quantization'' *Pauli W, ''Meson Theory of Nuclear Forces'', 2nd ed, Interscience Publishers, 1948. *Pauli W, ''Theory of Relativity'',

Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

, 1981.

Bibliography

* *See also

* List of Jewish Nobel laureatesReferences

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * Remo, F. Roth: ''Return of the World Soul, Wolfgang Pauli, C.G. Jung and the Challenge of Psychophysical Reality nus mundus Part 1: The Battle of the Giants''. Pari Publishing, 2011, . * Remo, F. Roth: ''Return of the World Soul, Wolfgang Pauli, C.G. Jung and the Challenge of Psychophysical Reality nus mundus Part 2: A Psychophysical Theory''. Pari Publishing, 2012, .External links

* *Pauli bio

at the University of St Andrews, Scotland

at "Nobel Prize Winners"

* ttp://alsos.wlu.edu/qsearch.aspx?browse=people/Pauli,+Wolfgang Annotated bibliography for Wolfgang Pauli from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Pauli Archives

at CERN Document Server

at ETH-Bibliothek, Zürich

– ''Linus Pauling and the Nature of the Chemical Bond: A Documentary History''

Pauli's letter (December 1930)

, the hypothesis of the neutrino (online and analyzed, for English version click 'Télécharger')

Pauli exclusion principle

with

Melvyn Bragg

Melvyn Bragg, Baron Bragg (born 6 October 1939) is an English broadcaster, author and parliamentarian. He is the editor and presenter of ''The South Bank Show'' (1978–2010, 2012–2023), and the presenter of the BBC Radio 4 documentary series ...

, Frank Close, Michela Massimi, Graham Farmelo "In Our Time 6 April 2017"

* Clary, David C. (2022)''Schrödinger in Oxford''

World Scientific Publishing. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Pauli, Wolfgang 1900 births 1958 deaths Nobel laureates in Physics Austrian Nobel laureates Nobel laureates from Austria-Hungary Jewish Nobel laureates 20th-century Austrian physicists Jewish emigrants from Austria after the Anschluss to the United States Deaths from pancreatic cancer in Switzerland Academic staff of ETH Zurich Foreign members of the Royal Society Institute for Advanced Study visiting scholars Jewish American physicists Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Naturalised citizens of Switzerland Lorentz Medal winners Mathematical physicists Quantum physicists Scientists from Vienna Theoretical physicists Thermodynamicists Academic staff of the University of Göttingen Winners of the Max Planck Medal Carl Jung Recipients of the Matteucci Medal Swiss Nobel laureates Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Academic staff of the University of Hamburg Recipients of Franklin Medal