Wilmot Proviso on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the

The Whigs faced a different scenario. The victory of James K. Polk (Democrat) over

The Whigs faced a different scenario. The victory of James K. Polk (Democrat) over

With the approval of the treaty, the issue moved from one of abstraction to one involving practical matters. The nature of the Constitution, slavery, the value of free labor, political power, and ultimately political realignment were all involved in the debate. Historian Michael Morrison argues that from 1820 to 1846 a combination of "racism and veneration of the Union" had prevented a direct Northern attack on slavery. While the original Southern response to the Wilmot Proviso was measured, it soon became clear to the South that this long postponed attack on slavery had finally occurred. Rather than simply discuss the politics of the issue, historian William Freehling noted, "Most Southerners raged primarily because David Wilmot's holier-than-thou stance was so insulting."

In the North, the most immediate repercussions involved

With the approval of the treaty, the issue moved from one of abstraction to one involving practical matters. The nature of the Constitution, slavery, the value of free labor, political power, and ultimately political realignment were all involved in the debate. Historian Michael Morrison argues that from 1820 to 1846 a combination of "racism and veneration of the Union" had prevented a direct Northern attack on slavery. While the original Southern response to the Wilmot Proviso was measured, it soon became clear to the South that this long postponed attack on slavery had finally occurred. Rather than simply discuss the politics of the issue, historian William Freehling noted, "Most Southerners raged primarily because David Wilmot's holier-than-thou stance was so insulting."

In the North, the most immediate repercussions involved

Wilmot Proviso

* {{Cite NIE, wstitle=Wilmot Proviso, , short=x Slavery in the United States Legal history of the United States Mexican–American War 1846 in the United States History of United States expansionism United States federal territory and statehood legislation Origins of the American Civil War Expansion of slavery in the United States

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.

Congressman David Wilmot

David Wilmot (January 20, 1814 – March 16, 1868) was an American politician and judge. He served as Representative and a Senator for Pennsylvania and as a judge of the Court of Claims. He is best known for being the prime sponsor and ep ...

of Pennsylvania first introduced the proviso in the House of Representatives on August 8, 1846, as a rider on a $2,000,000 appropriations bill intended for the final negotiations to resolve the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

(this was only three months into the two-year war). It passed the House but failed in the Senate, where the South had greater representation. It was reintroduced in February 1847 and again passed the House and failed in the Senate. In 1848, an attempt to make it part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

also failed. Sectional political disputes over slavery in the Southwest continued until the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

.

Background

After an earlier attempt to acquireTexas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

by treaty had failed to receive the necessary two-thirds approval of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

annexed the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas ( es, República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, that bordered Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840 (another breakaway republic from Me ...

by a joint resolution of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

that required simply a majority vote in each house of Congress. President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

signed the bill on March 1, 1845, a few days before his term ended. As many expected, the annexation led to war with Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. After the Capture of New Mexico and California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

in the first phases of the war, the political focus shifted to how much territory would be acquired from Mexico. The key to this was the determination of the future status of slavery in any new territory.

Both major political parties had labored long to keep divisive slavery issues out of national politics. The Democrats had generally been successful in portraying those within their party attempting to push a purely sectional issue as extremists that were well outside the normal scope of traditional politics. However, midway through Polk

Polk may refer to:

People

* James K. Polk, 11th president of the United States

* Polk (name), other people with the name

Places

* Polk (CTA), a train station in Chicago, Illinois

* Polk, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Polk, Missour ...

's term, Democratic dissatisfaction with the administration was growing within the Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, or Barnburner, wing of the Democratic Party over other issues. Many felt that Van Buren had been unfairly denied the party's nomination in 1844 when southern delegates resurrected a convention rule, last used in 1832, requiring that the nominee had to receive two-thirds of the delegate votes. Many in the North were also upset with the Walker tariff

The Walker Tariff was a set of tariff rates adopted by the United States in 1846. Enacted by the Democrats, it made substantial cuts in the high rates of the "Black Tariff" of 1842, enacted by the Whigs. It was based on a report by Secretary of ...

which reduced the tariff rates; others were opposed to Polk's veto of a popular river and harbor improvements bill, and still others were upset over the Oregon settlement with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

where it appeared that Polk did not pursue the northern territory with the same vigor he used to acquire Texas. Polk was seen more and more as enforcing strict party loyalty primarily to serve southern interests.

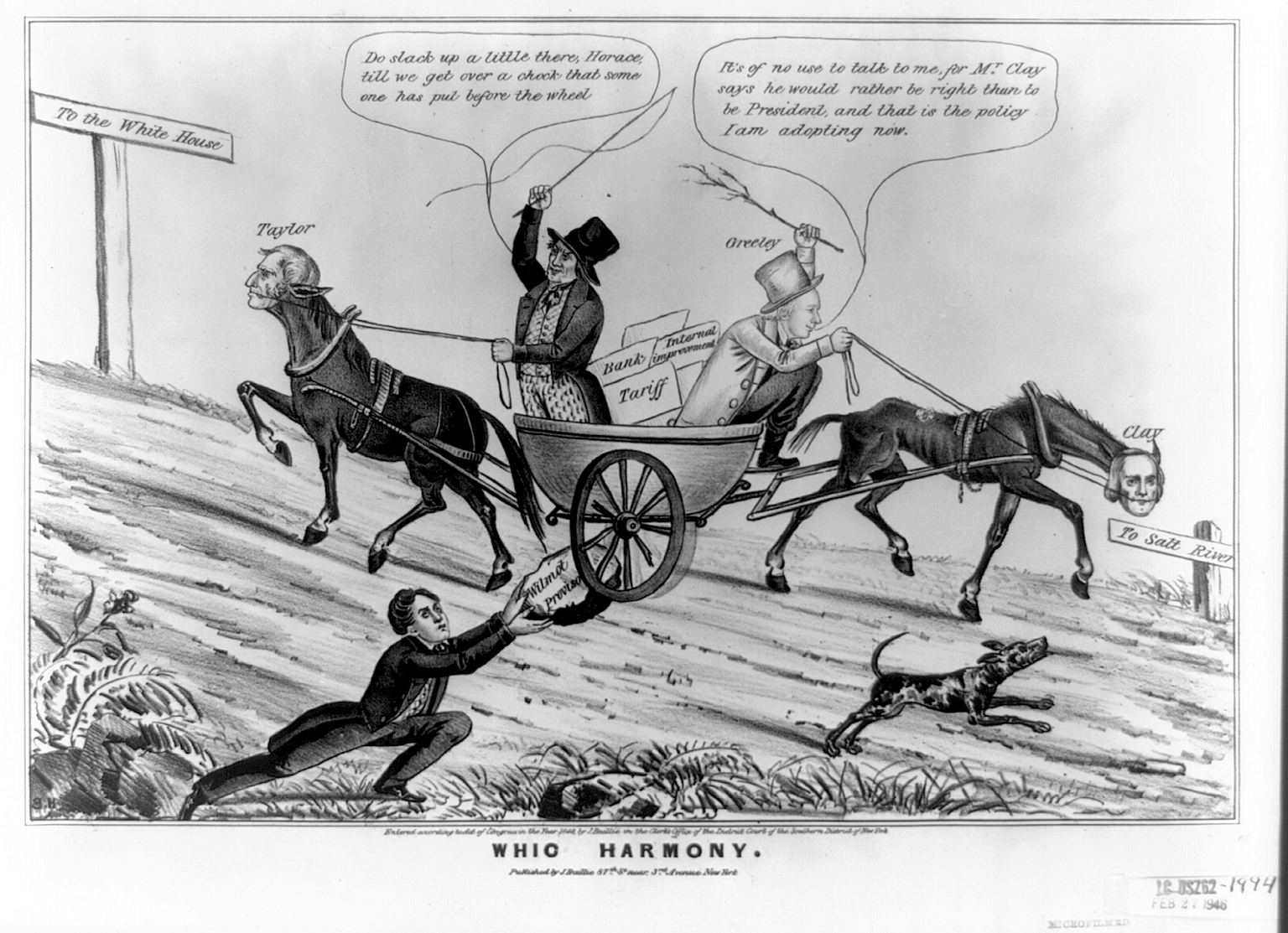

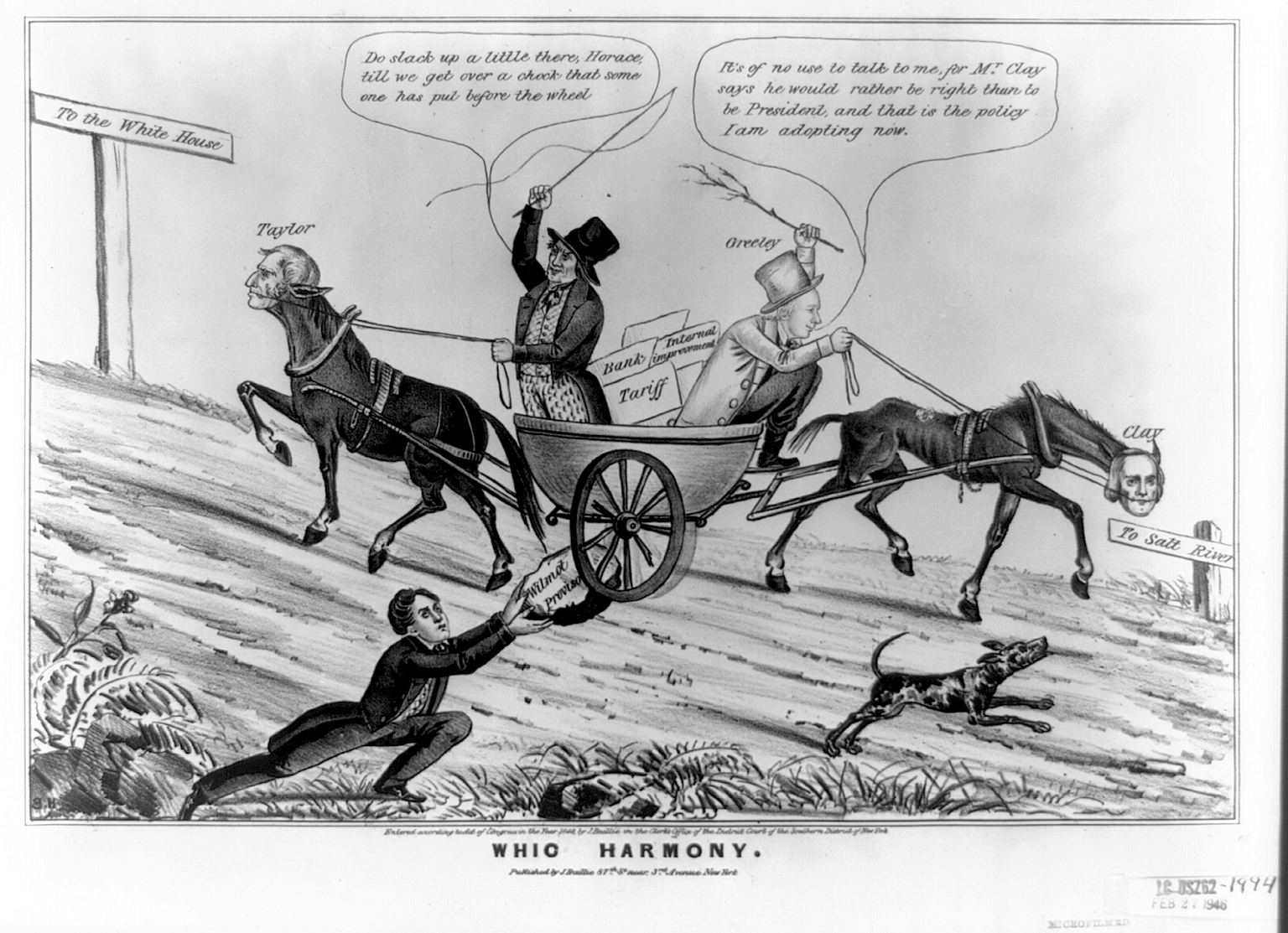

The Whigs faced a different scenario. The victory of James K. Polk (Democrat) over

The Whigs faced a different scenario. The victory of James K. Polk (Democrat) over Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

(Whig) in the 1844 presidential election had caught the Southern Whigs by surprise. The key element of this defeat, which carried over into the congressional and local races in 1845 and 1846 throughout the South, was the party's failure to take a strong stand favoring Texas annexation. Southern Whigs were reluctant to repeat their mistakes on Texas, but, at the same time, Whigs from both sections realized that victory and territorial acquisition would again bring out the issue of slavery and the territories. In the South in particular, there was already the realization, or perhaps fear, that the old economic issues that had defined the Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

were already dead. Their political goal was to avoid any sectional debate over slavery which would expose the sectional divisions within the party.

The Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

was seen by many as an effort to gain more territory for the establishment of slave states. It was popular in the South, and much less so in the North, where opposition took many forms. For example, Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and h ...

refused to pay his poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

, arguing that the money would be used to prosecute the war and gain slave territory.

Introduction and debate on the proviso

On Saturday, August 8, 1846, PresidentPolk

Polk may refer to:

People

* James K. Polk, 11th president of the United States

* Polk (name), other people with the name

Places

* Polk (CTA), a train station in Chicago, Illinois

* Polk, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Polk, Missour ...

submitted to Congress a request for $2,000,000 in order to facilitate negotiations with Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

over the final settlement of the war. The request came with no public warning after Polk had failed to arrange for approval of the bill with no Congressional debate. With Congress scheduled to adjourn that Monday, Democratic leadership arranged for the bill to be immediately considered in a special night session. The debate was to be limited to two hours with no individual speech to last more than ten minutes.

David Wilmot

David Wilmot (January 20, 1814 – March 16, 1868) was an American politician and judge. He served as Representative and a Senator for Pennsylvania and as a judge of the Court of Claims. He is best known for being the prime sponsor and ep ...

, a Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and a group of other Barnburner Democrats including Preston King and Timothy Jenkins of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Hannibal Hamlin

Hannibal Hamlin (August 27, 1809 – July 4, 1891) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 15th vice president of the United States from 1861 to 1865, during President Abraham Lincoln's first term. He was the first Republic ...

of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

, Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

, and Jacob Brinkerhoff of Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

, had already been meeting in early August strategy meetings. Wilmot had a strong record of supporting the Polk Administration and was close to many Southerners. With the likelihood that Wilmot would have no trouble gaining the floor in the House debate, he was chosen to present the amendment to the appropriations bill that would carry his name. Wilmot offered the following to the House in language modeled after the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

of 1787:

Provided, That, as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty which may be negotiated between them, and to the use by the Executive of the moneys herein appropriated, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall first be duly convicted.

William W. Wick

William W. Wick (February 23, 1796 – May 19, 1868) was a U.S. Representative from Indiana and Secretary of State of Indiana. He was a lawyer and over his career he was a judge for 15 years. President Franklin Pierce appointed him Postmaster of ...

, Democrat of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, attempted to eliminate total restriction of slavery by proposing an amendment that the Missouri Compromise line

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas to th ...

of latitude 36°30' simply be extended west to the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

. This was voted down 89–54. The vote to add the proviso to the bill was then called, and it passed by 83–64. A last-ditch effort by southerners to table the entire bill was defeated by 94–78, and then the entire bill was approved 85–80. These votes fell overwhelmingly along sectional rather than party lines.

The Senate took up the bill late in its Monday session. Southern Democrats hoped to reject the Wilmot Proviso and send the bill back to the House for a quick approval of the bill without the restrictions on slavery. Whig John Davis of Massachusetts attempted to forestall this effort by holding the floor until it would be too late to return the bill to the House, forcing the Senate to accept or reject the appropriation with the proviso intact. However, before he could call the vote, due to an eight-minute difference in the official House and Senate clocks, the House had adjourned and the Congress was officially out of session.

The issue resurfaced at the end of the year when Polk, in his annual message to Congress, renewed his request with the amount needed increasing to three million dollars. Polk argued that, while the original intent of the war had never been to acquire territory (a view hotly contested by his opponents), an honorable peace required territorial compensation to the United States.

Morrison (1997), p. 53. The Three Million Dollar Bill, as it was called, was the sole item of business in the House from February 8, 1847, until February 15. Preston King reintroduced the Wilmot Proviso, but this time the exclusion of slavery was expanded beyond merely the Mexican territory to include "any territory on the continent of America which shall hereafter be acquired". This time Representative Stephen Douglas, Democrat of Illinois, reintroduced the proposal to simply extend the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

line to the west coast, and this was again defeated 109–82. The Three Million Dollar Bill with the proviso was then passed by the House 115–106. In the Senate, led by Thomas Hart Benton (Democrat), the bill was passed without the proviso. When the bill was returned to the House the Senate bill prevailed; every Northern Whig still supported the proviso, but 22 Northern Democrats voted with the South.

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

ending the war was submitted to the Senate for approval. Douglas, now in the Senate, was among those who joined with the South to defeat an effort to attach the Wilmot Proviso to the treaty. In the prior year's debate in the House, Douglas had argued that all of the debate over slavery in the territories was premature; the time to deal with that issue was when the territory was actually organized by Congress. Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

(Democrat) in December 1847, in his famous letter to A. O. P. Nicholson in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, further defined the concept of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

which would soon evolve as the mainstream Democratic alternative to the Wilmot Proviso:

Leave it to the people, who will be affected by this question to adjust it upon their own responsibility, and in their own manner, and we shall render another tribute to the original principles of our government, and furnish another for its permanence and prosperity.

Aftermath

With the approval of the treaty, the issue moved from one of abstraction to one involving practical matters. The nature of the Constitution, slavery, the value of free labor, political power, and ultimately political realignment were all involved in the debate. Historian Michael Morrison argues that from 1820 to 1846 a combination of "racism and veneration of the Union" had prevented a direct Northern attack on slavery. While the original Southern response to the Wilmot Proviso was measured, it soon became clear to the South that this long postponed attack on slavery had finally occurred. Rather than simply discuss the politics of the issue, historian William Freehling noted, "Most Southerners raged primarily because David Wilmot's holier-than-thou stance was so insulting."

In the North, the most immediate repercussions involved

With the approval of the treaty, the issue moved from one of abstraction to one involving practical matters. The nature of the Constitution, slavery, the value of free labor, political power, and ultimately political realignment were all involved in the debate. Historian Michael Morrison argues that from 1820 to 1846 a combination of "racism and veneration of the Union" had prevented a direct Northern attack on slavery. While the original Southern response to the Wilmot Proviso was measured, it soon became clear to the South that this long postponed attack on slavery had finally occurred. Rather than simply discuss the politics of the issue, historian William Freehling noted, "Most Southerners raged primarily because David Wilmot's holier-than-thou stance was so insulting."

In the North, the most immediate repercussions involved Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

and the state of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. The Barnburners were successfully opposed by their conservative opposition, the Hunkers, in their efforts to send a pro-proviso batch of delegates to the 1848 Democratic National Convention. The Barnburners held their own separate convention and sent their own slate of delegates to the convention in Baltimore. Both delegations were seated with the state's total votes split between them. When the convention rejected a pro-proviso plank and selected Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

as the nominee, the Barnburners again bolted and were the nucleus of forming the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

. Historian Leonard Richards writes of these disaffected Democrats:

Overall, then, Southern Democrats during the 1840s lost the hard core of their original doughface support. No longer could they count on New England and New York Democrats to provide them with winning margins in the House. ...Historian

To them ree Soil Democratsthe movement to acquire Texas, and the fight over the Wilmot Proviso, marked the turning point, when aggressive slavemasters stole the heart and soul of the Democratic Party and began dictating the course of the nation's destiny.

William Cooper William Cooper may refer to:

Business

*William Cooper (accountant) (1826–1871), founder of Cooper Brothers

* William Cooper (businessman) (1761–1840), Canadian businessman

*William Cooper (co-operator) (1822–1868), English co-operator

* Will ...

presents the exactly opposite Southern perspective:

Southern Democrats, for whom slavery had always been central, had little difficulty in perceiving exactly what the proviso meant for them and their party. In the first place the mere existence of the proviso meant the sectional strains that had plagued the Whigs on Texas now beset the Democrats on expansion, the issue the Democrats themselves had chosen as their own. The proviso also announced to southerners that they had to face the challenge of certain northern Democrats who indicated their unwillingness to follow any longer the southern lead on slavery. That circumstance struck at the very roots of the southern conception of party. The southerners had always felt that their Northern colleagues must toe the southern line on all slavery-related issues.In

Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, with no available candidate sufficiently opposed to the proviso, William L. Yancey

William Lowndes Yancey (August 10, 1814July 27, 1863) was an American journalist, politician, orator, diplomat and an American leader of the Southern secession movement. A member of the group known as the Fire-Eaters, Yancey was one of the mo ...

secured the adoption by the state Democratic convention of the so-called " Alabama Platform", which was endorsed by the legislatures of Alabama and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and by Democratic state conventions in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

. The platform called for no federal restrictions of slavery in the territories, no restrictions on slavery by territorial governments until the point where they were drafting a state constitution in order to petition Congress for statehood, opposition to any candidates supporting either the proviso or popular sovereignty, and positive federal legislation overruling Mexican anti-slavery laws in the Mexican Cession. However, the same Democratic Convention that had refused to endorse the proviso also rejected incorporating the Yancey proposal into the national platform by a 216–36 vote. Unlike the Barnburner walkout, however, only Yancey and one other Alabama delegate left the convention. Yancey's efforts to stir up a third party movement in the state failed.

Southerner Whigs looked hopefully to slaveholder and war hero General Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

as the solution to the widening sectional divide even though he took no public stance on the Wilmot Proviso. However, Taylor, once nominated and elected, showed that he had his own plans. Taylor hoped to create a new non-partisan coalition that would once again remove slavery from the national stage. He expected to be able to accomplish this by freezing slavery at its 1849 boundaries and by immediately bypassing the territory stage and creating two new states out of the Mexican Cession.

The opening salvo in a new level of sectional conflict occurred on December 13, 1848, when John G. Palfrey (Whig) of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

introduced a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle (Washington, D.C.), Logan Circle, Jefferson Memoria ...

. Throughout 1849 in the South "the rhetoric of resistance to the North escalated and spread". The potentially secessionist Nashville Convention {{Events leading to US Civil War

The Nashville Convention was a political meeting held in Nashville, Tennessee, on June 3–11, 1850. Delegates from nine slave states met to consider secession, if the United States Congress decided to ban slavery ...

was scheduled for June 1850. When President Taylor in his December 1849 message to Congress urged the admission of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

as a free state, a state of crisis was further aggravated. Historian Allan Nevins sums up the situation which had been created by the Wilmot Proviso:

Thus the contest was joined on the central issue which was to dominate all American history for the next dozen years, the disposition of the Territories. Two sets of extremists had arisen: Northerners who demanded no new slave territories under any circumstances, and Southerners who demanded free entry for slavery into all territories, the penalty for denial to be secession. For the time being, moderates who hoped to find a way of compromise and to repress the underlying issue of slavery itself – its toleration or non-toleration by a great free Christian state – were overwhelmingly in the majority. But history showed that in crises of this sort the two sets of extremists were almost certain to grow in power, swallowing up more and more members of the conciliatory center.Combined with other slavery-related issues, the Wilmot Proviso led to the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

, which helped buy another uncertain decade of peace. Radical secessionists were temporarily at bay as the Nashville Convention failed to endorse secession. Moderates rallied around the Compromise as the final solution to the sectional issues involving slavery and the territories. At the same time, however, the language of the Georgia Platform The Georgia Platform was a statement executed by a Georgia Convention in Milledgeville, Georgia on December 10, 1850, in response to the Compromise of 1850. Supported by Unionists, the document affirmed the acceptance of the Compromise as a final ...

, widely accepted throughout the South, made it clear that the South's commitment to Union was not unqualified; they fully expected the North to adhere to their part of the agreement.

In regard to the territory the Proviso would have covered, California had a brief period of slavery due to slave owning settlers arriving during the 1848 California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

. Since there were no slave patrol

Slave patrols—also known as patrollers, patterrollers, pattyrollers or paddy rollersVerner D. Mitchell, Cynthia Davis (2019). ''Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement''. p. 323. Rowman & Littlefield—were organized groups of armed men who m ...

s or laws protecting slavery in the territory, slave escapes were quite common. Ultimately, California decided to ban slavery in their 1849 constitution and was admitted to the Union as a free state in 1850. Nevada would never have legal slavery and was admitted to the Union as a free state in 1864. The territories of Utah and New Mexico would have slavery from the time they were acquired by America in 1848 until July 1862, when the United States banned slavery in all federal territories. However, Utah's experience with slavery was minimal, as the 1860 census recorded only 30 slaves in the entire state.

See also

*Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the c ...

s

* Proviso Township, Illinois, named for the Wilmot Proviso

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Wilmot Proviso

* {{Cite NIE, wstitle=Wilmot Proviso, , short=x Slavery in the United States Legal history of the United States Mexican–American War 1846 in the United States History of United States expansionism United States federal territory and statehood legislation Origins of the American Civil War Expansion of slavery in the United States