William of Ockam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

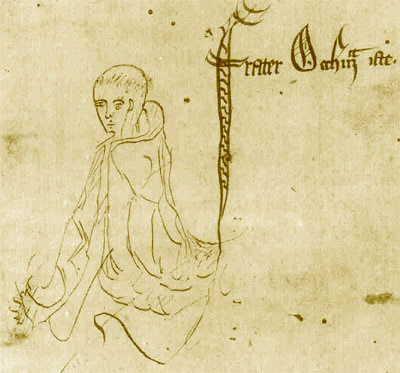

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic

''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. He was one of the first medieval authors to advocate a form of church/state separation, and was important for the early development of the notion of property rights. His political ideas are regarded as "natural" or "secular", holding for a secular absolutism. The views on monarchical accountability espoused in his ''Dialogus'' (written between 1332 and 1347) greatly influenced the

The standard edition of the philosophical and theological works is: ''William of Ockham: '', Gedeon Gál, et al., eds. 17 vols. St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1967–1988.

The seventh volume of the contains the doubtful and spurious works.

The political works, all but the , have been edited in H. S. Offler, et al., eds. , 4 vols., 1940–1997, Manchester: Manchester University Press ols. 1–3 Oxford: Oxford University Press ol. 4

Abbreviations: OT = vol. 1–10; OP = vol. 1–7.

The standard edition of the philosophical and theological works is: ''William of Ockham: '', Gedeon Gál, et al., eds. 17 vols. St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1967–1988.

The seventh volume of the contains the doubtful and spurious works.

The political works, all but the , have been edited in H. S. Offler, et al., eds. , 4 vols., 1940–1997, Manchester: Manchester University Press ols. 1–3 Oxford: Oxford University Press ol. 4

Abbreviations: OT = vol. 1–10; OP = vol. 1–7.

Mediaeval Logic and Philosophy

maintained by Paul Vincent Spade *

William of Ockham

at the

William of Ockham biography

at University of St Andrews, Scotland

at British Academy, UK

with an annotated bibliography

Richard Utz and Terry Barakat, "Medieval Nominalism and the Literary Questions: Selected Studies." ''Perspicuitas ''

* The Myth of Occam's Razor by William M. Thorburn (1918)

BBC Radio 4 'In Our Time' programme on Ockham

Download and listen * * * {{Use dmy dates, date=May 2020 1287 births 1347 deaths 14th-century English writers 14th century in science 14th-century writers in Latin 14th-century English mathematicians 14th-century English philosophers Alumni of the University of Oxford Catholic clergy scientists Empiricists English Roman Catholics English Franciscans English logicians English Christian theologians Latin commentators on Aristotle Occamism People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from the Borough of Guildford English philosophers of language Catholic philosophers Scholastic philosophers Anglican saints Nominalists

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, apologist

Apologetics (from Greek ) is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and recommended their fa ...

, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of the 14th century. He is commonly known for Occam's razor

In philosophy, Occam's razor (also spelled Ockham's razor or Ocham's razor; ) is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle o ...

, the methodological principle that bears his name, and also produced significant works on logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

and theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

. William is remembered in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

with a commemoration

Commemoration may refer to:

*Commemoration (Anglicanism), a religious observance in Churches of the Anglican Communion

*Commemoration (liturgy), insertion in one liturgy of portions of another

*Memorialization

*"Commemoration", a song by the 3rd a ...

corresponding to the commonly ascribed date of his death on 10 April.

Life

William of Ockham was born inOckham, Surrey

Ockham ( ) is a Rural area, rural and semi-rural village in the borough of Guildford in Surrey, England. The village starts immediately east of the A3 road, A3 but the lands extend to the River Wey in the west where it has a large mill-house. O ...

, around 1287. He received his elementary education in the London House of the Greyfriars. It is believed that he then studied theology at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

Spade, Paul Vincent (ed.). ''The Cambridge Companion to Ockham''. Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 20.He has long been claimed as a Merton alumnus, but there is no contemporary evidence to support this claim and as a Franciscan, he would have been ineligible for fellowships at Merton (see G. H. Martin and J. R. L. Highfield, ''A History of Merton College'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 53). The claim that he was a pupil of Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( ; , "Duns the Scot"; – 8 November 1308) was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher and theologian. He is considered one of the four most important Christian philosopher-t ...

at Oxford is also disputed (see Philip Hughes, ''History of the Church: Volume 3: The Revolt Against The Church: Aquinas To Luther'', Sheed and Ward, 1979, p. 119 n. 2). from 1309 to 1321, but while he completed all the requirements for a master's degree in theology, he was never made a regent master. Because of this he acquired the honorific title , or "Venerable Beginner" (an was a student formally admitted to the ranks of teachers by the university authorities).

During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, theologian Peter Lombard

Peter Lombard (also Peter the Lombard, Pierre Lombard or Petrus Lombardus; 1096 – 21/22 August 1160) was an Italian scholasticism, scholastic theologian, Bishop of Paris, and author of ''Sentences, Four Books of Sentences'' which became the s ...

's ''Sentences

The ''Sentences'' (. ) is a compendium of Christian theology written by Peter Lombard around 1150. It was the most important religious textbook of the Middle Ages.

Background

The sentence genre emerged from works like Prosper of Aquitaine's ...

'' (1150) had become a standard work of theology, and many ambitious theological scholars wrote commentaries on it.Olson, Roger E. (1999). ''The Story of Christian Theology'', p. 350. William of Ockham was among these scholarly commentators. However, William's commentary was not well received by his colleagues, or by the Church authorities. In 1324, his commentary was condemned as unorthodox and he was ordered to Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, France, to defend himself before the papal court.

An alternative understanding, recently proposed by George Knysh, suggests that he was initially appointed in Avignon as a professor of philosophy in the Franciscan school, and that his disciplinary difficulties did not begin until 1327. It is generally believed that these charges were levied by Oxford chancellor John Lutterell. The Franciscan Minister General, Michael of Cesena

Michael of Cesena (Michele di Cesena or Michele Fuschi) ( 1270 – 29 November 1342) was an Italian Franciscans, Franciscan, Minister general (Franciscan), minister general of that order, and theologian. His advocacy of Apostolic poverty, ev ...

, had been summoned to Avignon, to answer charges of heresy. A theological commission had been asked to review his ''Commentary on the Sentences'', and it was during this that William of Ockham found himself involved in a different debate. Michael of Cesena had asked William to review arguments surrounding Apostolic poverty

Apostolic poverty is a Christian doctrine professed in the thirteenth century by the newly formed religious orders, known as the mendicant orders, in direct response to calls for reform in the Roman Catholic Church. In this, these orders attempt ...

. The Franciscans believed that Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

and his apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary. The word is derived from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", itself derived from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to se ...

owned no property either individually or in common, and the Rule of Saint Francis

Francis of Assisi founded three orders and gave each of them a special rule. Here, only the rule of the first order is discussed, i.e., that of the Order of Friars Minor.

Origin and contents of the rule

Origin

Whether St. Francis wrote several ...

commanded members of the order to follow this practice. This brought them into conflict with Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Papacy, Avignon Pope, elected by ...

.

Because of the pope's attack on the Rule of Saint Francis, William of Ockham, Michael of Cesena

Michael of Cesena (Michele di Cesena or Michele Fuschi) ( 1270 – 29 November 1342) was an Italian Franciscans, Franciscan, Minister general (Franciscan), minister general of that order, and theologian. His advocacy of Apostolic poverty, ev ...

and other leading Franciscans fled Avignon on 26 May 1328, and eventually took refuge in the court of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Louis IV of Bavaria

Louis IV (; 1 April 1282 – 11 October 1347), called the Bavarian (, ), was King of the Romans from 1314, King of Italy from 1327, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1328 until his death in 1347.

Louis' election as king of Germany in 1314 was cont ...

, who was also engaged in dispute with the papacy, and became William's patron. After studying the works of John XXII and previous papal statements, William agreed with the Minister General. In return for protection and patronage William wrote treatises that argued for Emperor Louis to have supreme control over church and state in the Holy Roman Empire. "On June 6, 1328, William was officially excommunicated for leaving Avignon without permission", and William argued that John XXII was a heretic for attacking the doctrine of Apostolic poverty and the Rule of Saint Francis, which had been endorsed by previous popes. William of Ockham's philosophy was never officially condemned as heretical.

He spent much of the remainder of his life writing about political issues, including the relative authority and rights of the spiritual and temporal powers. After Michael of Cesena

Michael of Cesena (Michele di Cesena or Michele Fuschi) ( 1270 – 29 November 1342) was an Italian Franciscans, Franciscan, Minister general (Franciscan), minister general of that order, and theologian. His advocacy of Apostolic poverty, ev ...

's death in 1342, William became the leader of the small band of Franciscan dissidents living in exile with Louis IV. William of Ockham died (prior to the outbreak of the plague) on either 9 or 10 April 1347.

Philosophical thought

Inscholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

, William of Ockham advocated reform in both method and content, the aim of which was simplification. William incorporated much of the work of some previous theologians, especially Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( ; , "Duns the Scot"; – 8 November 1308) was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher and theologian. He is considered one of the four most important Christian philosopher-t ...

. From Duns Scotus, William of Ockham derived his view of divine omnipotence, his view of grace and justification, much of his epistemology and ethical convictions. However, he also reacted to and against Scotus in the areas of predestination, penance, his understanding of universals, his formal distinction (that is, "as applied to created things"), and his view of parsimony which became known as Occam's razor

In philosophy, Occam's razor (also spelled Ockham's razor or Ocham's razor; ) is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle o ...

.

Faith and reason

William of Ockham espousedfideism

Fideism ( ) is a standpoint or an epistemological theory which maintains that faith is independent of reason, or that reason and faith are hostile to each other and faith is superior at arriving at particular truths (see natural theology). The ...

, stating that "only faith gives us access to theological truths. The ways of God are not open to reason, for God has freely chosen to create a world and establish a way of salvation within it apart from any necessary laws that human logic or rationality can uncover." He believed that science was a matter of discovery and saw God as the only ontological necessity. His importance is as a theologian with a strongly developed interest in logical method, and whose approach was critical rather than system building.''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'', 6th ed. Edited by Margaret Drabble

Dame Margaret Drabble, Lady Holroyd, (born 5 June 1939) is an English biographer, novelist and short story writer.

Drabble's books include '' The Millstone'' (1965), which won the following year's John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize, and '' Je ...

, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 735.

Nominalism

William of Ockham was a pioneer ofnominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

, and some consider him the father of modern epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

, because of his strongly argued position that only individuals exist, rather than supra-individual universals

In metaphysics, a universal is what particular things have in common, namely characteristics or qualities. In other words, universals are repeatable or recurrent entities that can be instantiated or exemplified by many particular things. For exa ...

, essences, or forms, and that universals are the products of abstraction from individuals by the human mind and have no extra-mental existence. He denied the real existence of metaphysical universals and advocated the reduction of ontology

Ontology is the philosophical study of existence, being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of realit ...

.

William of Ockham is sometimes considered an advocate of conceptualism

In metaphysics, conceptualism is a theory that explains universality of particulars as conceptualized frameworks situated within the thinking mind. Intermediate between nominalism and realism, the conceptualist view approaches the metaphysical ...

rather than nominalism, for whereas nominalists held that universals were merely names, i.e. words rather than extant realities, conceptualists held that they were mental concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, ...

s, i.e. the names were names of concepts, which do exist, although only in the mind. Therefore, the universal concept has for its object, not a reality existing in the world outside us, but an internal representation which is a product of the understanding itself and which "supposes" in the mind the things to which the mind attributes it; that is, it holds, for the time being, the place of the things which it represents. It is the term of the reflective act of the mind. Hence the universal is not a mere word, as Roscelin taught, nor a ''sermo'', as Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard (12 February 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, teacher, musician, composer, and poet. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

In philos ...

held, namely the word as used in the sentence, but the mental substitute for real things, and the term of the reflective process. For this reason William has sometimes also been called a " Terminist", to distinguish him from a nominalist or a conceptualist.

Efficient reasoning

One important contribution that he made to modern science and modern intellectual culture was efficient reasoning with the principle of parsimony in explanation and theory building that came to be known asOccam's razor

In philosophy, Occam's razor (also spelled Ockham's razor or Ocham's razor; ) is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle o ...

. This maxim, as interpreted by Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, states that if one can explain a phenomenon without assuming this or that hypothetical entity, there is no ground for assuming it, i.e. that one should always opt for an explanation in terms of the fewest possible causes, factors, or variables. He turned this into a concern for ontological parsimony; the principle says that one should not multiply entities beyond necessity——although this well-known formulation of the principle is not to be found in any of William's extant writings. He formulates it as: "For nothing ought to be posited without a reason given, unless it is self-evident (literally, known through itself) or known by experience or proved by the authority of Sacred Scripture." For William of Ockham, the only truly necessary entity is God; everything else is contingent. He thus does not accept the principle of sufficient reason

The principle of sufficient reason states that everything must have a Reason (argument), reason or a cause. The principle was articulated and made prominent by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, with many antecedents, and was further used and developed by ...

, rejects the distinction between essence and existence, and opposes the Thomistic doctrine of active and passive intellect. His scepticism to which his ontological parsimony request leads appears in his doctrine that human reason can prove neither the immortality of the soul; nor the existence, unity, and infinity of God. These truths, he teaches, are known to us by revelation alone.

Natural philosophy

William wrote a great deal onnatural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

, including a long commentary on Aristotle's ''Physics''. According to the principle of ontological parsimony, he holds that we do not need to allow entities in all ten of Aristotle's categories; we thus do not need the category of quantity, as the mathematical entities are not "real". Mathematics must be applied to other categories, such as the categories of substance or qualities, thus anticipating modern scientific renaissance while violating Aristotelian prohibition of ''metabasis''.

Theory of knowledge

In the theory of knowledge, William rejected the scholastic theory of species, as unnecessary and not supported by experience, in favour of a theory of abstraction. This was an important development in late medievalepistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

. He also distinguished between intuitive and abstract cognition; intuitive cognition depends on the existence or non-existence of the object, whereas abstractive cognition "abstracts" the object from the existence predicate. Interpreters are, as yet, undecided about the roles of these two types of cognitive activities.

Political theory

William of Ockham is also increasingly being recognized as an important contributor to the development of Western constitutional ideas, especially those of government with limited responsibility."William of Ockham"''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. He was one of the first medieval authors to advocate a form of church/state separation, and was important for the early development of the notion of property rights. His political ideas are regarded as "natural" or "secular", holding for a secular absolutism. The views on monarchical accountability espoused in his ''Dialogus'' (written between 1332 and 1347) greatly influenced the

Conciliar movement

Conciliarism was a movement in the 14th-, 15th- and 16th-century Catholic Church which held that supreme authority in the Church resided with an ecumenical council, apart from, or even against, the pope.

The movement emerged in response to the We ...

. This tract on heresy had the ultimate purpose to establish the possibility of papal heresy and to consider what action should be taken against a pope who had become a heretic.

William argued for complete separation of spiritual rule and earthly rule. He thought that the pope and churchmen have no right or grounds at all for secular rule like having property, citing 2 Timothy 2:4. That belongs solely to earthly rulers, who may also accuse the pope of crimes, if need be.Virpi Mäkinen, ''Keskiajan aatehistoria'', Atena Kustannus Oy, Jyväskylä, 2003, . pp. 160, 167–168, 202, 204, 207–209.

After the Fall he believed God had given humanity, including non-Christians, two powers: private ownership and the right to set their rulers, who should serve the interest of the people, not some special interests. Thus he preceded Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

in formulating social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

theory along with earlier scholars.

William of Ockham said that the Franciscans avoided both private and common ownership by using commodities, including food and clothes, without any rights, with mere , the ownership still belonging to the donor of the item or to the pope. Their opponents such as Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Papacy, Avignon Pope, elected by ...

wrote that use without any ownership cannot be justified: "It is impossible that an external deed could be just if the person has no right to do it."

Thus the disputes on the heresy of Franciscans led William of Ockham and others to formulate some fundamentals of economic theory and the theory of ownership.

According to John Kilcullen, "Ockham's Utilitarian theory of property, his defence of civil and (within limits) religious liberty, and his emphasis on the inevitability of exceptions to rules and the need to adapt institutions to changing circumstances, anticipate J.S. Mill" (via Aristotle).

Logic

Inlogic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, William of Ockham wrote down in words the formulae that would later be called De Morgan's laws

In propositional calculus, propositional logic and Boolean algebra, De Morgan's laws, also known as De Morgan's theorem, are a pair of transformation rules that are both Validity (logic), valid rule of inference, rules of inference. They are nam ...

, and he pondered ternary logic

In logic, a three-valued logic (also trinary logic, trivalent, ternary, or trilean, sometimes abbreviated 3VL) is any of several many-valued logic systems in which there are three truth values indicating ''true'', ''false'', and some third value ...

, that is, a logical system

A formal system is an abstract structure and formalization of an axiomatic system used for deducing, using rules of inference, theorems from axioms.

In 1921, David Hilbert proposed to use formal systems as the foundation of knowledge in math ...

with three truth values

In logic and mathematics, a truth value, sometimes called a logical value, is a value indicating the relation of a proposition to truth, which in classical logic has only two possible values (''true'' or '' false''). Truth values are used in co ...

; a concept that would be taken up again in the mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of Logic#Formal logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory (also known as computability theory). Research in mathematical logic com ...

of the 19th and 20th centuries. His contributions to semantics

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

, especially to the maturing theory of supposition, are still studied by logicians. William of Ockham was probably the first logician to treat empty terms in Aristotelian syllogistic effectively; he devised an empty term semantics that exactly fit the syllogistic. Specifically, an argument is valid according to William's semantics if and only if it is valid according to ''Prior Analytics''.

Philosophy of Time

William of Ockham believed thateternity

Eternity, in common parlance, is an Infinity, infinite amount of time that never ends or the quality, condition or fact of being everlasting or eternal. Classical philosophy, however, defines eternity as what is timeless or exists outside tim ...

was exclusive to God. He rejected the concept of the aevum as a special measure of duration of for angels. He also said it is not proper to call eternity a measure of duration. In William's view, there was only one measure of duration, time, which was shared by all creation.

Theological thought

Church authority

William of Ockham deniedpapal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a Dogma in the Catholic Church, dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Saint Peter, Peter, the Pope when he speaks is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "in ...

and often went into conflict with the pope. As a result, some theologians have viewed him as a proto-Protestant. However, despite his conflicts with the papacy he did not renounce the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Ockham also held that councils of the Church were fallible, he held that any individual could err on matters of faith, and councils being composed of multiple fallible individuals could err. He thus foreshadowed some elements of Luther's view of sola scriptura

(Latin for 'by scripture alone') is a Christian theological doctrine held by most Protestant Christian denominations, in particular the Lutheran and Reformed traditions, that posits the Bible as the sole infallible source of authority for ...

.

Church and State

Ockham taught theseparation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

, believing that the pope and emperor should be separate.

Ockham adversed papal ''plenitudo potestatis

''Plenitudo potestatis'' (fullness of power) was a term employed by medieval canonists to describe the jurisdictional power of the papacy. In the thirteenth century, the canonists used the term ''plenitudo potestatis'' to characterize the pow ...

'': even the famous allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

of the Sun-Pope/Moon-Emperor is contradicted by Our Lord, who, while admitting the greater/lower opposition (Occkham holds spiritual power and the Church's own functions in the highest esteem; in this sense, and only in this sense, does he consider them of greater importance), does not concede to the Curialists, defenders of the fullness of papal power, the argument that the Moon originated from the Sun.

According to Ockham, the Pope obtains his power from the Council and, therefore, from the whole of all believers. In the same way, the elected Emperor is depositary of a power whose origin lies in the people who are always the authentic sovereign.

Occkham developed in canon law the theories that Marsilius of Padua

Marsilius of Padua (; born ''Marsilio Mainardi'', ''Marsilio de i Mainardini'' or ''Marsilio Mainardini''; – ) was an Italian scholar, trained in medicine, who practiced a variety of professions. He was also an important 14th-century pol ...

had promoted in civil law (e.g. popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

).

Apostolic poverty

Ockham advocated for voluntary poverty.Soul

Ockham opposed Pope John XXII on the question of the Beatific Vision. John had proposed that the souls of Christians did not instantly get to enjoy the vision of God, rather such vision would be postponed until the last judgement.Voluntarism

William of Ockham was a theological voluntarist who believed that if God had wanted to, he could have become incarnate as a donkey or an ox, or even as both a donkey and a man at the same time. He was criticized for this belief by his fellow theologians and philosophers.Literary Ockhamism/nominalism

William of Ockham and his works have been discussed as a possible influence on several late medieval literary figures and works, especiallyGeoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

, but also Jean Molinet

Jean Molinet (1435 – 23 August 1507) was a French poet, chronicler, and composer. He is best remembered for his prose translation of '' Roman de la rose''.

Born in Desvres, which is now part of France, he studied in Paris. He entered th ...

, the ''Gawain'' poet, François Rabelais

François Rabelais ( , ; ; born between 1483 and 1494; died 1553) was a French writer who has been called the first great French prose author. A Renaissance humanism, humanist of the French Renaissance and Greek scholars in the Renaissance, Gr ...

, John Skelton, Julian of Norwich

Julian of Norwich ( – after 1416), also known as Juliana of Norwich, the Lady Julian, Dame Julian or Mother Julian, was an English anchoress of the Middle Ages. Her writings, now known as ''Revelations of Divine Love'', are the earli ...

, the York and Townely Plays, and Renaissance romances. Only in very few of these cases is it possible to demonstrate direct links to William of Ockham or his texts. Correspondences between Ockhamist and Nominalist philosophy/theology and literary texts from medieval to postmodern times have been discussed within the scholarly paradigm of literary nominalism. Erasmus, in his ''Praise of Folly'', criticized him together with Duns Scotus as fuelling unnecessary controversies inside the Church.

Works

The standard edition of the philosophical and theological works is: ''William of Ockham: '', Gedeon Gál, et al., eds. 17 vols. St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1967–1988.

The seventh volume of the contains the doubtful and spurious works.

The political works, all but the , have been edited in H. S. Offler, et al., eds. , 4 vols., 1940–1997, Manchester: Manchester University Press ols. 1–3 Oxford: Oxford University Press ol. 4

Abbreviations: OT = vol. 1–10; OP = vol. 1–7.

The standard edition of the philosophical and theological works is: ''William of Ockham: '', Gedeon Gál, et al., eds. 17 vols. St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1967–1988.

The seventh volume of the contains the doubtful and spurious works.

The political works, all but the , have been edited in H. S. Offler, et al., eds. , 4 vols., 1940–1997, Manchester: Manchester University Press ols. 1–3 Oxford: Oxford University Press ol. 4

Abbreviations: OT = vol. 1–10; OP = vol. 1–7.

Philosophical writings

* (''Sum of Logic

The ''Summa Logicae'' ("Sum of Logic") is a textbook on logic by William of Ockham. It was written around 1323.

Systematically, it resembles other works of medieval logic, organised under the basic headings of the Aristotelian Predicables, Ca ...

'') (c. 1323, OP 1).

* , 1321–1324, OP 2).

* , 1321–1324, OP 2).

* , 1321–1324, OP 2).

* , 1321–1324, OP 2).

* (''Treatise on Predestination and God's Foreknowledge with respect to Future Contingents'', 1322–1324, OP 2).

* (''Exposition of Aristotle's Sophistic refutations'', 1322–1324, OP 3).

* (''Exposition of Aristotle's Physics'') (1322–1324, OP 4).

* (''Exposition of Aristotle's Physics'') (1322–1324, OP 5).

* (''Brief Summa of the Physics'', 1322–23, OP 6).

* (''Little Summa of Natural Philosophy'', 1319–1321, OP 6).

* (''Questions on Aristotle's Books of the Physics'', before 1324, OP 6).

Theological writings

* (''Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard''). ** Book I () completed shortly after July 1318 (OT 1–4). ** Books II–IV () 1317–18 (transcription of the lectures; OT 5–7). * (OT 8). * (before 1327) (OT 9). * (1323–24. OT 10). * (1323–24, OT 10).Political writings

* (1332–1334). * (1334). * (before 1335). * XII(1335). * II(1337–38). * (1340–41). * (1341–42). * (1341–42). * lso known as (1346–47).Doubtful writings

* (''Lesser Treatise on logic'') (1340–1347?, OP 7). * (''Primer of logic'') (1340–1347?, OP 7).Spurious writings

* (OP 7). * (OP 7). * (OP 7). * (OP 7).Translations

Philosophical works

*''Philosophical Writings'', tr. P. Boehner, rev. S. Brown (Indianapolis, Indiana, 1990) *''Ockham's Theory of Terms: Part I of the '', translated by Michael J. Loux (Notre Dame; London: University of Notre Dame Press, 1974) ranslation of , part 1*''Ockham's Theory of Propositions: Part II of the '', translated by Alfred J. Freddoso and Henry Schuurman (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1980) ranslation of , part 2*''Demonstration and Scientific Knowledge in William of Ockham: a Translation of III-II, , and Selections from the Prologue to the '', translated by John Lee Longeway (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame, 2007) *''Falacies: Part 3, Book 4 of '', translated by Richard Robinson (Sunny Lou Publishing, 2025.) *''Ockham on Aristotle's Physics: A Translation of Ockham's '', translated by Julian Davies (St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1989) *Kluge, Eike-Henner W., "William of Ockham's Commentary on Porphyry: Introduction and English Translation", ''Franciscan Studies'' 33, pp. 171–254, , and 34, pp. 306–382, (1973–74) *''Predestination, God's Foreknowledge, and Future Contingents'', translated by Marilyn McCord Adams and Norman Kretzmann (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1969) ranslation of *''Quodlibetal Questions'', translated by Alfred J. Freddoso and Francis E. Kelley, 2 vols (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1991) (translation of ) * Paul Spade, ''Five Texts on the Mediaeval Problem of Universals: Porphyry, Boethius, Abelard, Duns Scotus, Ockham'' (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett, 1994) ive questions on Universals from His d. 2 qq. 4–8Theological works

*''The of William of Ockham'', translated by T. Bruce Birch (Burlington, Iowa: Lutheran Literary Board, 1930) ranslation of ''Treatise on Quantity'' and ''On the Body of Christ''Political works

*, translated Cary J. Nederman, in ''Political thought in early fourteenth-century England: treatises by Walter of Milemete, William of Pagula, and William of Ockham'' (Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2002) *''A translation of William of Ockham's Work of Ninety Days'', translated by John Kilcullen and John Scott (Lewiston, New York: E. Mellen Press, 2001) ranslation of *, translated in ''A compendium of Ockham's teachings: a translation of the '', translated by Julian Davies (St. Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute, St. Bonaventure University, 1998) *''On the Power of Emperors and Popes'', translated by Annabel S. Brett (Bristol, 1998) *Rega Wood, ''Ockham on the Virtues'' (West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 1997) ncludes translation of ''On the Connection of the Virtues''*''A Letter to the Friars Minor, and Other Writings'', translated by John Kilcullen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995) ncludes translation of *''A Short Discourse on the Tyrannical Government'', translated by John Kilcullen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992) ranslation of * William of Ockham, uestion One of''Eight Questions on the Power of the Pope'', translated by Jonathan RobinsonIn fiction

William of Occam served as an inspiration for the creation of William of Baskerville, the main character ofUmberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian Medieval studies, medievalist, philosopher, Semiotics, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular ...

's novel ''The Name of the Rose

''The Name of the Rose'' ( ) is the 1980 debut novel by Italian author Umberto Eco. It is a historical fiction, historical murder mystery set in an Italian monastery in the year 1327, and an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in fiction, ...

'', and is the main character of '' La Abadía del Crimen'' (''The Abbey of Crime''), a video game based upon said novel.

See also

* Gabriel Biel * Philotheus Boehner * List of Catholic clergy scientists * List of scholastic philosophers * Ernest Addison Moody * Ockham algebra * Oxford Franciscan school *Rule according to higher law

The rule according to a higher law is a philosophical concept that no law may be enforced by the government unless it conforms with certain universal principles (written or unwritten) of fairness, morality, and justice. Thus, ''the rule accordin ...

* Terminism

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Mediaeval Logic and Philosophy

maintained by Paul Vincent Spade *

William of Ockham

at the

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''IEP'') is a scholarly online encyclopedia with around 900 articles about philosophy, philosophers, and related topics. The IEP publishes only peer review, peer-reviewed and blind-refereed original p ...

William of Ockham biography

at University of St Andrews, Scotland

at British Academy, UK

with an annotated bibliography

Richard Utz and Terry Barakat, "Medieval Nominalism and the Literary Questions: Selected Studies." ''Perspicuitas ''

* The Myth of Occam's Razor by William M. Thorburn (1918)

BBC Radio 4 'In Our Time' programme on Ockham

Download and listen * * * {{Use dmy dates, date=May 2020 1287 births 1347 deaths 14th-century English writers 14th century in science 14th-century writers in Latin 14th-century English mathematicians 14th-century English philosophers Alumni of the University of Oxford Catholic clergy scientists Empiricists English Roman Catholics English Franciscans English logicians English Christian theologians Latin commentators on Aristotle Occamism People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from the Borough of Guildford English philosophers of language Catholic philosophers Scholastic philosophers Anglican saints Nominalists