William Walker (filibuster) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Walker (May 8, 1824September 12, 1860) was an American

On October 15, 1853, Walker set out with forty-five men to conquer the Mexican territories of

On October 15, 1853, Walker set out with forty-five men to conquer the Mexican territories of

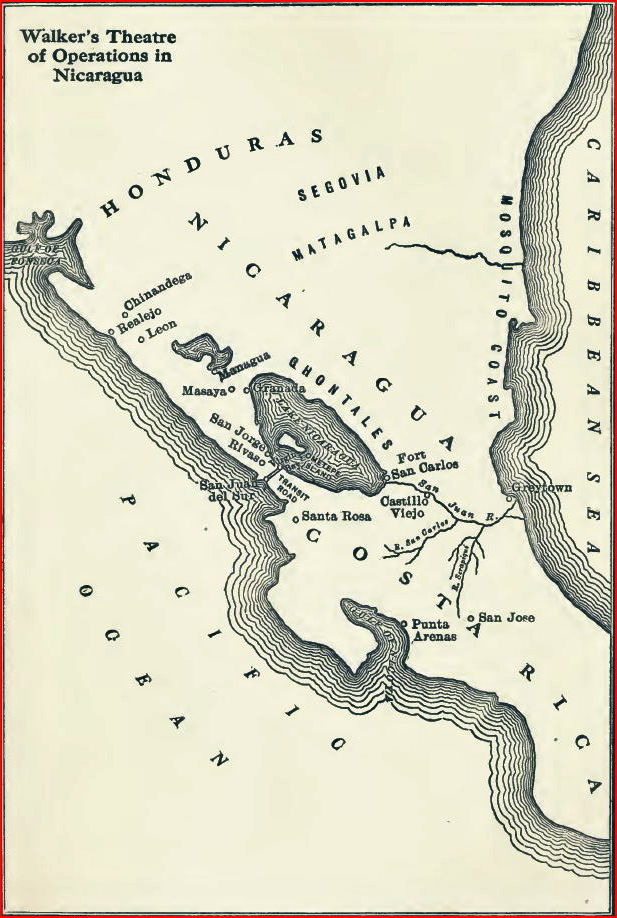

Since there was no inter-oceanic route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at the time, and the

Since there was no inter-oceanic route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at the time, and the

After writing an account of his Central American campaign (published in 1860 as ''War in Nicaragua''), Walker once again returned to the region. British colonists in

After writing an account of his Central American campaign (published in 1860 as ''War in Nicaragua''), Walker once again returned to the region. British colonists in

Before the end of the

Before the end of the

Walker's campaigns in Lower California and Nicaragua are the subject of a historical novel by Alfred Neumann, published in German as ''Der Pakt'' (1949), and translated in English as ''Strange Conquest'' (a previous UK edition was published as ''Look Upon This Man'').

Walker's campaign in Nicaragua has inspired two films, both of which take considerable liberties with his story: ''

Walker's campaigns in Lower California and Nicaragua are the subject of a historical novel by Alfred Neumann, published in German as ''Der Pakt'' (1949), and translated in English as ''Strange Conquest'' (a previous UK edition was published as ''Look Upon This Man'').

Walker's campaign in Nicaragua has inspired two films, both of which take considerable liberties with his story: ''

''The War in Nicaragua''

New York (NY): S.H. Goetzel, 1860.

excerpt and text search

* * * Gobat, Michel. ''Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America'' (Harvard UP, 2018

roundtable evaluation by scholars at H-Diplo

* Juda, Fanny. ''California Filibusters: A History of their Expeditions into Hispanic America'' * * * * * Moore, J. Preston. "Pierre Soule: Southern Expansionist and Promoter," ''Journal of Southern History'' 21:2 (May, 1955), 208 & 214. * Norvell, John Edward, "How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857: The Norvell Family origins of the Grey Eyed Man of Destiny," ''The Middle Tennessee Journal of Genealogy and History'', Vol XXV, No. 4, Spring 2012 * "1855: American Conquistador," ''American Heritage'', October 2005. * Recko, Corey. "Murder on the White Sands." University of North Texas Press. 2007 *

"William Walker"

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 28 Oct. 2008.

''William Walker and the Imperial Self in American Literature''

Athens, Ga.:

The Legacy of the Filibuster War: National Identity and Collective Memory in Central America

" Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2019. . * Deville, Patrick, ''Pura Vida: Vie et mort de William Walker'',

''Filibusters and Financiers: the Story of William Walker and his Associates''

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1916.

from the ''Vanderbilt Register''

from the ''Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco'' * Fuchik, Do

The California Native Newsletter

''Walker''

the 1987

"How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857 The Norvell family origins of The Grey Eyed Man of Destiny"

The memory palace podcast episode about William Walker.

* Walker, William

The War in Nicaragua

at

Brief recount of William Walker trying to conquer Baja California

* ttp://omniatlas.com/maps/northamerica/18570402/ Maps of North America and the Caribbean showing Walker's expeditions at omniatlas.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Walker, William 1824 births 1860 deaths People from Nashville, Tennessee Executed presidents American filibusters (military) American duellists Leaders who took power by coup Presidents of Nicaragua American people of Scottish descent University of Nashville alumni Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania alumni Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Medical School American people executed abroad People executed by Honduras by firing squad Executed Nicaraguan people 19th-century executions of American people Executed revolutionaries Executed people from Tennessee 19th-century Nicaraguan people 19th-century American journalists American male journalists American shooting survivors Norvell family 19th-century American male writers American proslavery activists Prisoners and detainees of the British military People who were court-martialed

physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

, lawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

, journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

, and mercenary

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rather t ...

. In the era of the expansion of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, driven by the doctrine of "manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

", Walker organized unauthorized military expeditions into Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

with the intention of establishing colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

. Such an enterprise was known at the time as "filibustering

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

".

After settling in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, motivated by an earlier filibustering project of Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon

Charles René Gaston Gustave de Raousset-Boulbon (May 5, 1817 – August 13, 1854) was a French adventurer, filibuster and entrepreneur and, by some accounts a pirate, and a theoretician of colonialism.

Early life

Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon was ...

, Walker attempted in 1853–54 to take Baja California

Baja California, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California, is a state in Mexico. It is the northwesternmost of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. Before becoming a state in 1952, the area was known as the North Territory of B ...

and Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into Municipalities of Sonora, 72 ...

. He declared those territories to be an independent Republic of Sonora, but he was soon driven back to California by the Mexican forces. Walker then went to Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

in 1855 as leader of a mercenary army employed by the Nicaraguan Democratic Party in its civil war against the Legitimists

The Legitimists () are royalists who adhere to the rights of dynastic succession to the French crown of the descendants of the eldest branch of the House of Bourbon, Bourbon dynasty, which was overthrown in the 1830 July Revolution. They reject ...

. He took control of the Nicaraguan government and in July 1856 set himself up as the country's president.

Walker's regime was recognized as the legitimate government of Nicaragua by US President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

, and it initially enjoyed the support of some important sectors within Nicaraguan society. However, Walker antagonized the powerful Wall Street tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

by expropriating Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company, which operated one of the main routes for the transport of passengers going from New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

to San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. The British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

saw Walker as a threat to its interests in the possible construction of a Nicaragua Canal. As ruler of Nicaragua, Walker re-legalized slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, although this measure was never enforced, and threatened the independence of neighboring Central American republics. A military coalition led by Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

defeated Walker and forced him to resign the presidency of Nicaragua on May 1, 1857.

Walker then tried to re-launch his filibustering project and in 1860 published a book, ''The War in Nicaragua'', which cast his efforts to conquer Central America as tied to the geographical expansion of slavery. In that way, Walker sought to gain renewed support from pro-slavery forces in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

on the eve of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. The same year, Walker returned to Central America but was arrested by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, who handed him over to the Honduran government, which executed him.

Early life

William Walker was born inNashville, Tennessee

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

, in 1824 to James Walker and his wife Mary Norvell. His father was an English settler. His mother was the daughter of Lipscomb Norvell, an American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

officer from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. One of Walker's maternal uncles was John Norvell, a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

from Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

and founder of ''The Philadelphia Inquirer

''The Philadelphia Inquirer'', often referred to simply as ''The Inquirer'', is a daily newspaper headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded on June 1, 1829, ''The Philadelphia Inquirer'' is the third-longest continuously operating da ...

''. Walker was engaged to Ellen Martin, but she died of yellow fever before they could be married, and he died without children.

Walker graduated ''summa cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sout ...

'' from the University of Nashville

University of Nashville was a private university in Nashville, Tennessee. It was established in 1806 as Cumberland College. It existed as a distinct entity until 1909; operating at various times a medical school, a four-year military college, a ...

at the age of 14. In 1843, at the age of 19, he received a medical degree

A medical degree is a professional degree admitted to those who have passed coursework in the fields of medicine and/or surgery from an accredited medical school. Obtaining a degree in medicine allows for the recipient to continue on into special ...

from the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

. Walker then continued his medical studies at Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

and Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

. He practiced medicine briefly in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, but soon moved to New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

where he studied law privately.

Walker practiced law for a short time, then quit to become co-owner and editor of the ''New Orleans Crescent'' newspaper. In 1849, he moved to San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, where he worked as editor of the '' San Francisco Herald'' and fought three duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapons.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and later the small sword), but beginning in ...

s; he was wounded in two of them. Walker then conceived the idea of conquering vast regions of Central America and creating new slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

s to join those already part of the Union. These campaigns were known as filibustering

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

, or freebooting, and were supported by the Southern expansionist secret society

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ag ...

, the Knights of the Golden Circle

The Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC) was a secret society founded in 1854 by American George W. L. Bickley, the objective of which was to create a new country known as the Golden Circle (), where slavery would be legal. The country would have ...

.

Duel with William Hicks Graham

Walker gained national attention by dueling withlaw clerk

A law clerk, judicial clerk, or judicial assistant is a person, often a lawyer, who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by Legal research, researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial ...

William Hicks Graham on January 12, 1851. Walker criticized Graham and his colleagues in the ''Herald'', which angered Graham and prompted him to challenge Walker to a duel. Graham was a notorious gunman, having taken part in a number of duels and shootouts in the Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West, and popularly known as the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that bega ...

. Walker, on the other hand, had experience dueling with single-shot pistol

A pistol is a type of handgun, characterised by a gun barrel, barrel with an integral chamber (firearms), chamber. The word "pistol" derives from the Middle French ''pistolet'' (), meaning a small gun or knife, and first appeared in the Englis ...

s at one time, but his duel with Graham was fought with revolver

A revolver is a repeating handgun with at least one barrel and a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold six cartridges before needing to be reloaded, ...

s.Chamberlain, Ryan. ''Pistols, Politics and the Press: Dueling in 19th Century American Journalism''. McFarland (2008). p. 92.

The combatants met at Mission Dolores Dolores, Spanish for "pain; grief", most commonly refers to:

* Our Lady of Sorrows or La Virgen María de los Dolores

* Dolores (given name), including list of people and fictional characters with the name

Dolores may also refer to:

Film

* '' ...

, where each was given a Colt Dragoon with five shots. They stood face to face at ten paces, and each aimed and fired at the signal of a referee. Graham managed to fire two bullets, hitting Walker in his pantaloons and his thigh, seriously wounding him. Walker tried a number of times to shoot his weapon, but he failed to land even a single shot and Graham was left unscathed. The duel ended when Walker conceded. Graham was arrested but was quickly released. The duel was recorded in ''The Daily Alta California

The ''Alta California'' or ''Daily Alta California'' (often miswritten ''Alta Californian'' or ''Daily Alta Californian'') was a 19th-century San Francisco newspaper.

''California Star''

The ''Daily Alta California'' descended from the first ...

''.

Invasion of Mexico

After a failed attempt to invade the Mexican Province ofSonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into Municipalities of Sonora, 72 ...

from the state of Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

, In the summer of 1853, Walker traveled to Guaymas

Guaymas () is a city in Guaymas Municipality, in the southwest part of the List of states of Mexico, state of Sonora, in northwestern Mexico. The city is south of the state capital of Hermosillo, and from the Mexico – United States border, U.S. ...

in Mexico, seeking a grant from the Mexican government

The Federal government of Mexico (alternately known as the Government of the Republic or ' or ') is the national government of the United Mexican States, the central government established by its constitution to share sovereignty over the republ ...

to establish a colony. He proposed that his colony would serve as a fortified frontier, protecting U.S. soil from Indian raids. Mexico refused, and Walker returned to San Francisco determined to obtain his colony regardless of Mexico's position. He began recruiting American supporters of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and of the Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

doctrine, mostly inhabitants of Tennessee and Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

. Walker's plans then expanded from forming a buffer colony to establishing an independent Republic of Sonora, which might eventually take its place as a part of the Union (as the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

had done in 1845). He funded his project by "selling scrip

A scrip (or ''wikt:chit#Etymology 3, chit'' in India) is any substitute for legal tender. It is often a form of credit (finance), credit. Scrips have been created and used for a variety of reasons, including exploitative payment of employees un ...

s which were redeemable in lands of Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into Municipalities of Sonora, 72 ...

".

Baja California Territory

Baja California Territory (Territorio de Baja California) was a federal territory of Mexico that existed from 1824 to 1853, and 1854 to 1931; it encompassed the Baja California peninsula of present-day northwestern part of the country. It re ...

and Sonora State. He succeeded in capturing La Paz

La Paz, officially Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Aymara language, Aymara: Chuqi Yapu ), is the seat of government of the Bolivia, Plurinational State of Bolivia. With 755,732 residents as of 2024, La Paz is the List of Bolivian cities by populati ...

, the capital of sparsely populated Baja California

Baja California, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California, is a state in Mexico. It is the northwesternmost of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. Before becoming a state in 1952, the area was known as the North Territory of B ...

, which he declared the capital of a new " Republic of Lower California" (declared November 3, 1853), with himself as president and his former law partner, Henry P. Watkins, as vice president. Walker then put the region under the laws of the American state of Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, which made slavery legal. Whether Walker at this stage intended to tie his filibustering expedition to the cause of slavery is a matter of dispute.

Fearful of attacks by Mexico, Walker moved his headquarters twice over the next three months, first to Cabo San Lucas

Cabo San Lucas (, "Luke the Evangelist, Saint Luke Cape (geography), Cape"), also known simply as Cabo, is a Resort town, resort city at the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula, in the Mexican Political divisions of Mexico, state of Baja ...

, and then further north to Ensenada to maintain a more secure base of operations. Although he never gained control of Sonora, he pronounced Baja California part of the larger Republic of Sonora. Lack of supplies, severe aridity of Baja California and strong resistance by the Mexican government quickly forced Walker to retreat.

Back in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, Walker was indicted by a federal grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

for waging an illegal war in violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794

The Neutrality Act of 1794 was a Law of the United States#Federal law, United States law which made it illegal for a United States citizen to wage war against any country at peace with the United States. The Act declares in part:

If any person ...

. However, in the era of Manifest Destiny, Walker's filibustering project had popular support in the southern and western U.S. Walker was tried before Judge I. S. K. Ogier in the US District Court for the Southern District of California. Although two of Walker's associates had already been convicted of similar charges and Judge Ogier summarized the evidence against Walker for the jury, the jury deliberated for only eight minutes before acquitting Walker.

Invasion of Nicaragua

transcontinental railway

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks may be via the tracks of a single railroad ...

did not yet exist, a major trade route between New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and San Francisco ran through southern Nicaragua. Ships from New York entered the San Juan River from the Atlantic and sailed across Lake Nicaragua

Lake Nicaragua or Cocibolca or Granada (, , or ) is a freshwater lake in Nicaragua. Of tectonic origin and with an area of , it is the largest fresh water lake in Central America, the List of lakes by area, 19th largest lake in the world (by are ...

. People and goods were then transported by stagecoach across a narrow strip of land near the city of Rivas, before reaching the Pacific and ships to San Francisco. The commercial exploitation of this route had been granted by Nicaragua to the Accessory Transit Company, controlled by shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

.

In 1854, a civil war erupted in Nicaragua between the Legitimist Party (also called the Conservative Party), based in the city of Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

, and the Democratic Party (also called the Liberal Party), based in León. The Democratic Party sought military support from Walker who, to circumvent U.S. neutrality laws, obtained a contract from Democratic president Francisco Castellón

Francisco Castellón Sanabria (18158 September 1855) was president of "Democratic" Nicaragua from 1854 to 1855 during the Granada-León civil war.

Castellón was a lawyer from León. He was prime minister (''ministro general'') under Patricio ...

to bring as many as three hundred "colonists" to Nicaragua. These mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

received the right to bear arms in the service of the Democratic government. Walker sailed from San Francisco on May 3, 1855, with approximately sixty men. Upon landing, the force was reinforced by 110 locals. With Walker's expeditionary force was the well-known explorer and journalist Charles Wilkins Webber, as well as Belgian-born adventurer Charles Frederick Henningsen, a veteran of the First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Monarchy of Spain, Spanish monarchy: the conservative a ...

, the Hungarian Revolution, and the war in Circassia. Besides Henningsen, three members of Walker's forces who became Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

officers were Birkett D. Fry, Robert C. Tyler

Robert Charles Tyler (December 4, 1832 – April 16, 1865) was a Confederate States of America, Confederate Brigadier General during the American Civil War. He was the last general killed in the conflict.

He commanded the 15th Tennessee Infantry ...

, and Chatham Roberdeau Wheat.

With Castellón's consent, Walker attacked the Legitimists in Rivas, near the trans-isthmian route. He was driven off, but not without inflicting heavy casualties. In this First Battle of Rivas, a schoolteacher called Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio (1834–1872) burned the Filibuster headquarters. On September 3, during the Battle of La Virgen, Walker defeated the Legitimist army. On October 13, he conquered Granada and took effective control of the country. Initially, as commander of the army, Walker ruled Nicaragua through provisional President Patricio Rivas

Patricio Rivas (1810 – July 12, 1867) was a wealthy liberal Nicaraguan lawyer and politician, member of the Democratic Party (Nicaragua), Democratic Party, who served as Acting President of Nicaragua, Supreme Director of Nicaragua from June 30, ...

. U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

recognized Walker's regime as the legitimate government of Nicaragua on May 20, 1856, and on June 3 the Democratic national convention expressed support of the effort to "regenerate" Nicaragua. However, Walker's first ambassadorial appointment, Colonel Parker H. French, was refused recognition. On September 22, Walker repealed Nicaraguan laws prohibiting slavery, in an attempt to gain support from the Southern states.

Walker's actions in the region caused concern in neighboring countries and potential U.S. and European investors who feared he would pursue further military conquests in Central America. C. K. Garrison and Charles Morgan, subordinates of Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company, provided financial and logistical support to the Filibusters in exchange for Walker, as ruler of Nicaragua, seizing the company's property (on the pretext of a charter violation) and turning it over to Garrison and Morgan. Outraged, Vanderbilt dispatched two secret agents to the Costa Rican government with plans to fight Walker. They would help regain control of Vanderbilt's steamboats which had become a logistical lifeline for Walker's army.

Concerned about Walker's intentions in the region, Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras

Juan Rafael Mora Porras (8 February 1814, San José, Costa Rica – 30 September 1860) was President of Costa Rica from 1849 to 1859.

Life and career

Mora first assumed the presidency upon the resignation of his younger brother, Miguel Mor ...

rejected his diplomatic overtures and began preparing the country's military for a potential conflict. Walker organized a battalion of four companies, of which one was composed of Germans, a second of Frenchmen, and the other two of Americans, totaling 240 men placed under the command of Colonel Schlessinger to invade Costa Rica in a preemptive action. This advance force was defeated at the Battle of Santa Rosa on March 20, 1856.

The most important strategic defeat of Walker came during the Campaign of 1856–57 when the Costa Rican army, led by Porras, General José Joaquín Mora Porras

José Joaquín Mora Porras (1818–1860) was a Costa Rican politician. He was the younger brother of the presidents of that country, Juan Rafael Mora Porras

Juan Rafael Mora Porras (8 February 1814, San José, Costa Rica – 30 Septembe ...

(the president's brother), and General José María Cañas (1809–1860), defeated the Filibusters in Rivas on April 11, 1856 (the Second Battle of Rivas). It was in this battle that the soldier and drummer Juan Santamaría

Juan Santamaría Rodríguez (August 29, 1831 – April 11, 1856) was a Drummer (military), drummer in the Costa Rican army, officially recognized as the Hero (title), national hero of his country for his actions in the 1856 Second Battle of ...

sacrificed himself by setting the Filibuster stronghold on fire. In parallel with Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio in Nicaragua, Santamaría would become Costa Rica's national hero. Walker deliberately contaminated the water wells of Rivas with corpses. Later, a cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic spread to the Costa Rican troops and the civilian population of Rivas. Within a few months nearly 10,000 civilians had died, almost ten percent of the population of Costa Rica.

From the north, President José Santos Guardiola sent Honduran troops under the leadership of the Xatruch brothers, who joined Salvadoran troops to fight Walker. Florencio Xatruch

Florencio Xatruch (October 21, 1811 – February 15, 1893) was a general who led the Honduran expeditionary force against William Walker in Nicaragua in 1856.

Life

Florencio Xatruch was born in San Antonio de Oriente, Honduras. His fathe ...

led his troops against Walker and the filibusters in la Puebla, Rivas. Later, because of the opposition of other Central American armies, José Joaquín Mora Porras was made Commandant General-in-Chief of the Allied Armies of Central America in the Third Battle of Rivas (April 1857).

During this civil war, Honduras and El Salvador recognized Xatruch as brigade and division general. On June 12, 1857, after Walker surrendered, Xatruch made a triumphant entrance to Comayagua

Comayagua () is a city, municipality and old capital of Honduras, located northwest of Tegucigalpa on the highway to San Pedro Sula and above sea level.

The accelerated growth experienced by the city of Comayagua led the municipal authoriti ...

, which was then the capital of Honduras. Both the nickname by which Hondurans are known today, Catracho, and the more infamous nickname for Salvadorans, "Salvatrucho", are derived from Xatruch's figure and successful campaign as leader of the allied armies of Central America, as the troops of El Salvador and Honduras were national heroes, fighting side by side as Central American brothers against William Walker's troops.

As the general and his soldiers returned from battle, some Nicaraguans affectionately yelled out ("Here come Xatruch's boys!") However, Nicaraguans had trouble pronouncing the general's Catalan name, so they altered the phrase to "los catruches" and ultimately to "los catrachos".

A key role was played by the Costa Rican Army in unifying the other Central American armies to fight against Filibusters. The "Campaign of the Transit" (1857) is the name given by Costa Rican historians to the groups of several battles fought by the Costa Rican Army, supervised by Colonel Salvador Mora, and led by Colonel Blanco and Colonel Salazar at the San Juan River. By establishing control of this bi-national river at its border with Nicaragua, Costa Rica prevented military reinforcements from reaching Walker and his Filibuster troops via the Caribbean Sea. Also, Costa Rican diplomacy neutralized U.S. official support for Walker by taking advantage of the dispute between the magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

and William Walker.

Walker took up residence in Granada and set himself up as President of Nicaragua, after conducting a fraudulent election. He was inaugurated on July 12, 1856, and soon launched an Americanization program, reinstating slavery, declaring English an official language, and reorganizing currency and fiscal policy to encourage emigration from the United States. Realizing that his position was becoming precarious, he sought support from the Southerners in the U.S. by recasting his campaign as a fight to spread the institution of black slavery, which was the basis of the Southern agrarian economy. With this in mind, Walker revoked Nicaragua's emancipation edict of 1821. This move increased Walker's popularity among Southern whites and attracted the attention of Pierre Soulé, an influential New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

politician, who campaigned to raise support for Walker's war. Nevertheless, Walker's army was weakened by massive defections and an epidemic of cholera and was finally defeated by the Central American coalition led by Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras

Juan Rafael Mora Porras (8 February 1814, San José, Costa Rica – 30 September 1860) was President of Costa Rica from 1849 to 1859.

Life and career

Mora first assumed the presidency upon the resignation of his younger brother, Miguel Mor ...

(1814–1860).

On October 12, 1856, Guatemalan Colonel José Víctor Zavala crossed the square of the city to the house where Walker's soldiers took shelter. Under heavy fire, he reached the enemy's flag and carried it back with him, shouting to his men that the Filibuster bullets did not kill.

On December 14, 1856, as Granada was surrounded by 4,000 troops from Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, along with independent Nicaraguan allies, Charles Frederick Henningsen, one of Walker's generals, ordered his men to set the city ablaze before escaping and fighting their way to Lake Nicaragua. When retreating from Granada, the oldest Spanish colonial city in Nicaragua, he left a detachment with orders to level it in order to instill, as he put it, "a salutary dread of American justice". It took them over two weeks to smash, burn and flatten the city; all that remained were inscriptions on the ruins that read ("Here was Granada").

On May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to Commander Charles Henry Davis

Charles Henry Davis ( – ) was a Autodidacticism, self-educated American astronomer and Rear admiral (United States), rear admiral of the United States Navy. While working for the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, United States Coast ...

of the United States Navy under the pressure of Costa Rica and the Central American armies and was repatriated. Upon disembarking in New York City, he was greeted as a hero, but he alienated public opinion when he blamed his defeat on the U.S. Navy. Within six months, he set off on another expedition, but he was arrested by the U.S. Navy Home Squadron

The Home Squadron was part of the United States Navy in the mid-19th century. Organized as early as 1838, ships were assigned to protect coastal commerce, aid ships in distress, suppress piracy and the Atlantic slave trade, make coastal surveys ...

under the command of Commodore Hiram Paulding and once again returned to the U.S. amid considerable public controversy over the legality of the navy's actions.

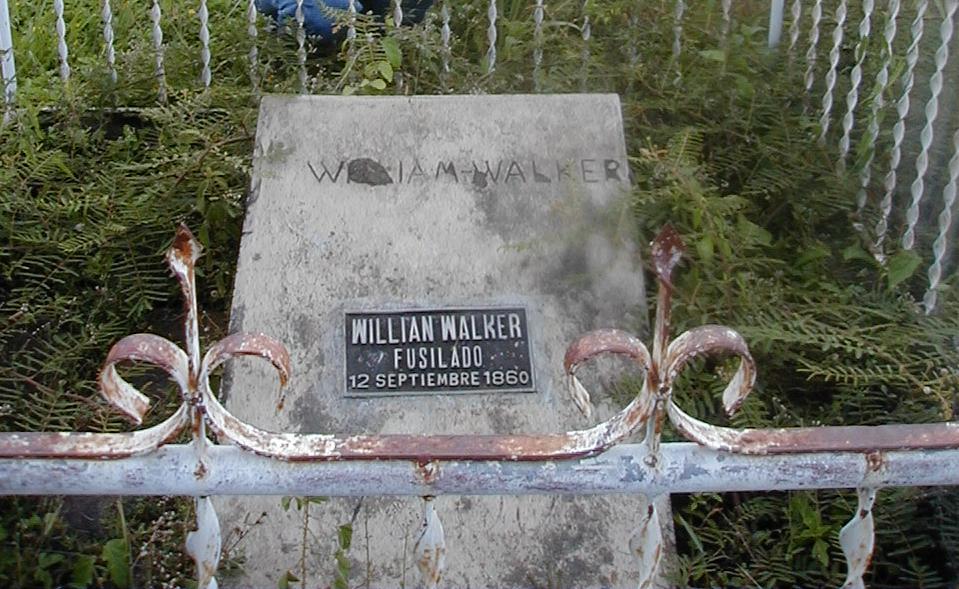

Conviction and execution

Roatán

Roatán () is an island in the Caribbean, about off the northern coast of Honduras. The largest of the Bay Islands Department, Bay Islands of Honduras, it is located between the islands of Utila and Guanaja. It is approximately long, and le ...

, Bay Islands, fearing that the Honduran government would move to assert its control over them, approached Walker with an offer to help him in establishing an independent, English-speaking administration over the islands. Walker disembarked in the port city of Trujillo but was arrested by Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

officer Nowell Salmon. Britain, which maintained control over nearby British Honduras

British Honduras was a Crown colony on the east coast of Central America — specifically located on the southern edge of the Yucatan Peninsula from 1783 to 1964, then a self-governing colony — renamed Belize from June 1973

and the Mosquito Coast

The Mosquito Coast, also known as Mosquitia, is a historical and Cultural area, geo-cultural region along the western shore of the Caribbean Sea in Central America, traditionally described as extending from Cabo Camarón, Cape Camarón to the C ...

and planned on constructing an inter-oceanic canal through Central America, regarded Walker as a threat to its own affairs in the region.

Salmon sailed to Trujillo and handed Walker over to the Honduran government along with his chief of staff, A. F. Rudler. Both men were tried by a Honduran military court on charges of piracy and "filibusterism". In his defense, Walker argued that piracy could not be committed on land and "filibusterism" wasn't a word. Rudler was sentenced to four years of hard labor in Honduran mines, but Walker was sentenced to be executed by firing squad, which was carried out near the site of the present-day hospital, on September 12, 1860. William Walker was 36 years old. He is buried in the "Old Cemetery", Trujillo, Colón, Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

.

Influence and reputation

William Walker convinced many Southerners of the desirability of creating a slave-holding empire in tropical Latin America. In 1861, when U.S. Senator John J. Crittenden proposed that the 36°30' parallel north be declared as a line of demarcation between free and slave territories, some Republicans denounced such an arrangement, with New York congressmanRoscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

saying that it "would amount to a perpetual covenant of war against every people, tribe, and State owning a foot of land between here and Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South America, South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan.

The archipelago consists of the main is ...

".

Before the end of the

Before the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Walker's memory enjoyed great popularity in the southern and western United States, where he was known as "General Walker" and as the "gray-eyed man of destiny". Northerners, on the other hand, generally regarded him as a pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

. Despite his intelligence and personal charm, Walker consistently proved to be a limited military and political leader . Unlike men of similar ambition, such as Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, Walker's grandiose scheming ultimately failed.

In Central American countries, the successful military campaign of 1856–1857 against William Walker became a source of national pride and identity, and it was later promoted by local historians and politicians as substitute for the war of independence that Central America had not experienced. April 11 is a Costa Rican national holiday in memory of Walker's defeat at Rivas. Juan Santamaría

Juan Santamaría Rodríguez (August 29, 1831 – April 11, 1856) was a Drummer (military), drummer in the Costa Rican army, officially recognized as the Hero (title), national hero of his country for his actions in the 1856 Second Battle of ...

, who played a key role in that battle, is honored as one of two Costa Rican national heroes, the other one being Juan Rafael Mora himself. The main airport serving San José (in Alajuela

Alajuela () is a district in the Alajuela (canton), Alajuela canton of the Alajuela Province of Costa Rica. As the seat of the Municipality of Alajuela canton, it is awarded the status of city. By virtue of being the city of the first canton of ...

) is named in Santamaría's honor.

To this day, a sense of Central American "coalition" among the nations of Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, along with independent Nicaraguan allies, is remembered and celebrated as a unifying shared history.

Cultural legacy

Walker's campaigns in Lower California and Nicaragua are the subject of a historical novel by Alfred Neumann, published in German as ''Der Pakt'' (1949), and translated in English as ''Strange Conquest'' (a previous UK edition was published as ''Look Upon This Man'').

Walker's campaign in Nicaragua has inspired two films, both of which take considerable liberties with his story: ''

Walker's campaigns in Lower California and Nicaragua are the subject of a historical novel by Alfred Neumann, published in German as ''Der Pakt'' (1949), and translated in English as ''Strange Conquest'' (a previous UK edition was published as ''Look Upon This Man'').

Walker's campaign in Nicaragua has inspired two films, both of which take considerable liberties with his story: ''Burn!

''Burn!'' (original title: ''Queimada'', Spanish and Portuguese for "Burnt" or "Burned") is a 1969 historical war drama film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo. Set in the mid-19th century, the film stars Marlon Brando as a British ''agent provoca ...

'' (1969) directed by Gillo Pontecorvo

Gilberto Pontecorvo (; 19 November 1919 – 12 October 2006) was an Italian filmmaker associated with the political cinema movement of the 1960s and 1970s. He is best known for directing the landmark war docudrama '' The Battle of Algiers'' (19 ...

, starring Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Widely regarded as one of the greatest cinema actors of the 20th century,''Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia''

, and ''Walker

Walker or The Walker may refer to:

People

*Walker (given name)

*Walker (surname)

*Walker (Brazilian footballer) (born 1982), Brazilian footballer

Places

In the United States

*Walker, Arizona, in Yavapai County

*Walker, Mono County, California

* ...

'' (1987) directed by Alex Cox

Alexander B. H. Cox (born 15 December 1954) is an English film director, screenwriter, actor, non-fiction author and broadcaster. Cox experienced success early in his career with ''Repo Man (film), Repo Man'' (1984) and ''Sid and Nancy'' (1986 ...

, starring Ed Harris

Edward Allen Harris (born November 28, 1950) is an American actor and filmmaker. His performances in '' Apollo 13'' (1995), '' The Truman Show'' (1998), '' Pollock'' (2000), and '' The Hours'' (2002) earned him critical acclaim and Academy Awa ...

. Walker's name is used for the main character in ''Burn!'', though the character is not meant to represent the historical William Walker and is portrayed as British. On the other hand, Alex Cox's ''Walker'' incorporates into its surrealist narrative many of the signposts of William Walker's life and exploits, including his original excursions into northern Mexico to his trial and acquittal on breaking the neutrality act to the triumph of his assault on Nicaragua and his execution.

In Part Five, Chapter 48, of ''Gone with the Wind Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind ...

'', Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell (November 8, 1900 – August 16, 1949) was an American novelist and journalist. Mitchell wrote only one novel that was published during her lifetime, the American Civil War-era novel ''Gone With the Wind (novel), Gone ...

cites William Walker, "and how he died against a wall in Truxillo", as a topic of conversation between Rhett Butler

Rhett Butler (born 1828) is a fictional character in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell and in the 1939 film adaptation Gone with the Wind (film), of the same name. It is one of Clark Gable's ...

and his filibustering acquaintances, while Rhett and Scarlett O'Hara

Katie Scarlett O'Hara is the protagonist of Margaret Mitchell's 1936 in literature, 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' and the 1939 Gone with the Wind (film), film of the same name, where she is portrayed by Vivien Le ...

are on honeymoon in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

.

A poem written by Nicaraguan Catholic priest and minister of culture from 1979 to 1987 during the Sandinista period Ernesto Cardenal

Ernesto Cardenal Martínez (20 January 1925 – 1 March 2020) was a Nicaraguan Catholic priest, poet, and politician. He was a liberation theologian and the founder of the primitivist art community in the Solentiname Islands, where he lived fo ...

, ''Con Walker En Nicaragua,'' translated as ''With Walker in Nicaragua'', gives a historical treatment of the affair from the Nicaraguan perspective.

The villain of the Nantucket series

The Nantucket series (also known as the Nantucket trilogy or the Islander trilogy) is a set of alternate history novels written by S. M. Stirling.

The novels focus on the island of Nantucket in Massachusetts which was transported back in time t ...

, by science fiction writer S. M. Stirling, is a 20th-century American mercenary named William Walker, who is time-displaced from 1998 CE to 1250 BCE. Walker demonstrates a similar personality to his historical namesake, leading a filibuster force to Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainla ...

and initiating a version of the Trojan War

The Trojan War was a legendary conflict in Greek mythology that took place around the twelfth or thirteenth century BC. The war was waged by the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans (Ancient Greece, Greeks) against the city of Troy after Paris (mytho ...

with firearms.

John Neal

John Neal (August 25, 1793 – June 20, 1876) was an American writer, critic, editor, lecturer, and activist. Considered both eccentric and influential, he delivered speeches and published essays, novels, poems, and short stories between the 1 ...

's 1859 novel ''True Womanhood'' includes a character who travels from the US to Nicaragua. When he returns, it turns out he has been involved in Walker's campaign there. This may be based on his son James or his friend's son, Appleton Oaksmith, both of whom made the trip and were involved with Walker in that country.

Works

* Walker, William''The War in Nicaragua''

New York (NY): S.H. Goetzel, 1860.

See also

*Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon

Charles René Gaston Gustave de Raousset-Boulbon (May 5, 1817 – August 13, 1854) was a French adventurer, filibuster and entrepreneur and, by some accounts a pirate, and a theoretician of colonialism.

Early life

Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon was ...

* Knights of the Golden Circle

The Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC) was a secret society founded in 1854 by American George W. L. Bickley, the objective of which was to create a new country known as the Golden Circle (), where slavery would be legal. The country would have ...

, a secret society interested in annexing territories in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to be added to the United States as slave states

* Nicaragua Canal

* Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

* Florencio Xatruch

Florencio Xatruch (October 21, 1811 – February 15, 1893) was a general who led the Honduran expeditionary force against William Walker in Nicaragua in 1856.

Life

Florencio Xatruch was born in San Antonio de Oriente, Honduras. His fathe ...

* Granada, Nicaragua

Granada () is a city in western Nicaragua and the capital of the Granada Department. With an estimated population of 105,862 (2022), it is Nicaragua's ninth most populous city. Granada is historically one of Nicaragua's most important cities, econ ...

, the colonial city that William Walker destroyed

Notes

References

Secondary sources

* Carr, Albert Z. ''The World and William Walker'', 1963. * Dando-Collins, Stephen. ''Tycoon's War: How Cornelius Vanderbilt Invaded a Country to Overthrow America's Most Famous Military Adventurer'' (2008excerpt and text search

* * * Gobat, Michel. ''Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America'' (Harvard UP, 2018

roundtable evaluation by scholars at H-Diplo

* Juda, Fanny. ''California Filibusters: A History of their Expeditions into Hispanic America'' * * * * * Moore, J. Preston. "Pierre Soule: Southern Expansionist and Promoter," ''Journal of Southern History'' 21:2 (May, 1955), 208 & 214. * Norvell, John Edward, "How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857: The Norvell Family origins of the Grey Eyed Man of Destiny," ''The Middle Tennessee Journal of Genealogy and History'', Vol XXV, No. 4, Spring 2012 * "1855: American Conquistador," ''American Heritage'', October 2005. * Recko, Corey. "Murder on the White Sands." University of North Texas Press. 2007 *

"William Walker"

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 28 Oct. 2008.

Primary sources

* Doubleday, C.W. ''Reminiscences of the Filibuster War in Nicaragua''. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1886. * Jamison, James Carson. ''With Walker in Nicaragua: Reminiscences of an Officer of the American Phalanx''. Columbia, MO: E.W. Stephens, 1909. * Wight, Samuel F. ''Adventures in California and Nicaragua: a Truthful Epic''. Boston: Alfred Mudge & Son, 1860. * Fayssoux Collection. Tulane University. Latin American Library. * ''United States Magazine''. Sept., 1856. Vol III No. 3. pp. 266–72 * "Filibustering", ''Putnam's Monthly Magazine'' (New York), April 1857, 425–35. * "Walker's Reverses in Nicaragua," ''Anti-Slavery Bugle'', November 17, 1856. * "The Lesson" ''National Era'', June 4, 1857, 90. * "The Administration and Commodore Paulding," ''National Era'', January 7, 1858. * "Wanted – A Few Filibusters," ''Harper's Weekly'', January 10, 1857. * "Reception of Gen. Walker," ''New Orleans Picayune'', May 28, 1857. * "Arrival of Walker," ''New Orleans Picayune'', May 28, 1857. * "Our Influence in the Isthmus," ''New Orleans Picayune'', February 17, 1856. * ''New Orleans Sunday Delta'', June 27, 1856. * "Nicaragua and President Walker," ''Louisville Times'', December 13, 1856. * "Le Nicaragua et les Filibustiers," ''Opelousas Courier'', May 10, 1856. * "What is to Become of Nicaragua?," ''Harper's Weekly'', June 6, 1857. * "The Late General Walker," ''Harper's Weekly'', October 13, 1860. * "What General Walker is Like," ''Harper's Weekly'', September, 1856. * "Message of the President to the Senate in Reference to the Late Arrest of Gen. Walker," ''Louisville Courier'', January 12, 1858. * "The Central American Question – What Walker May Do," ''New York Times'', January 1, 1856. * "A Serious Farce," ''New York Times'', December 14, 1853. * 1856–57 ''New York Herald''Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

editorials.

Further reading

* Harrison, Brady''William Walker and the Imperial Self in American Literature''

Athens, Ga.:

University of Georgia Press

The University of Georgia Press or UGA Press is the university press of the University of Georgia, a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Athens, Georgia. It is the oldest and largest publishing house in Georgia and a me ...

, 2004. .

* Cabrera Geserick, Marco.The Legacy of the Filibuster War: National Identity and Collective Memory in Central America

" Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2019. . * Deville, Patrick, ''Pura Vida: Vie et mort de William Walker'',

Seuil

Seuil () is a commune in the Ardennes department in northern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Ardennes department

The following is a list of the 447 communes of the Ardennes department of France

France, officially ...

, Paris, 2004

* Scroggs, William O., Ph.D., Professor of Economics and Sociology in Louisiana State University''Filibusters and Financiers: the Story of William Walker and his Associates''

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1916.

External links

*from the ''Vanderbilt Register''

from the ''Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco'' * Fuchik, Do

The California Native Newsletter

''Walker''

the 1987

Alex Cox

Alexander B. H. Cox (born 15 December 1954) is an English film director, screenwriter, actor, non-fiction author and broadcaster. Cox experienced success early in his career with ''Repo Man (film), Repo Man'' (1984) and ''Sid and Nancy'' (1986 ...

movie, ''Walker

Walker or The Walker may refer to:

People

*Walker (given name)

*Walker (surname)

*Walker (Brazilian footballer) (born 1982), Brazilian footballer

Places

In the United States

*Walker, Arizona, in Yavapai County

*Walker, Mono County, California

* ...

'', featuring Ed Harris

Edward Allen Harris (born November 28, 1950) is an American actor and filmmaker. His performances in '' Apollo 13'' (1995), '' The Truman Show'' (1998), '' Pollock'' (2000), and '' The Hours'' (2002) earned him critical acclaim and Academy Awa ...

as William Walker, at the Internet Movie Database

IMDb, historically known as the Internet Movie Database, is an online database of information related to films, television series, podcasts, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and biograp ...

"How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857 The Norvell family origins of The Grey Eyed Man of Destiny"

The memory palace podcast episode about William Walker.

* Walker, William

The War in Nicaragua

at

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical charac ...

Brief recount of William Walker trying to conquer Baja California

* ttp://omniatlas.com/maps/northamerica/18570402/ Maps of North America and the Caribbean showing Walker's expeditions at omniatlas.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Walker, William 1824 births 1860 deaths People from Nashville, Tennessee Executed presidents American filibusters (military) American duellists Leaders who took power by coup Presidents of Nicaragua American people of Scottish descent University of Nashville alumni Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania alumni Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Medical School American people executed abroad People executed by Honduras by firing squad Executed Nicaraguan people 19th-century executions of American people Executed revolutionaries Executed people from Tennessee 19th-century Nicaraguan people 19th-century American journalists American male journalists American shooting survivors Norvell family 19th-century American male writers American proslavery activists Prisoners and detainees of the British military People who were court-martialed