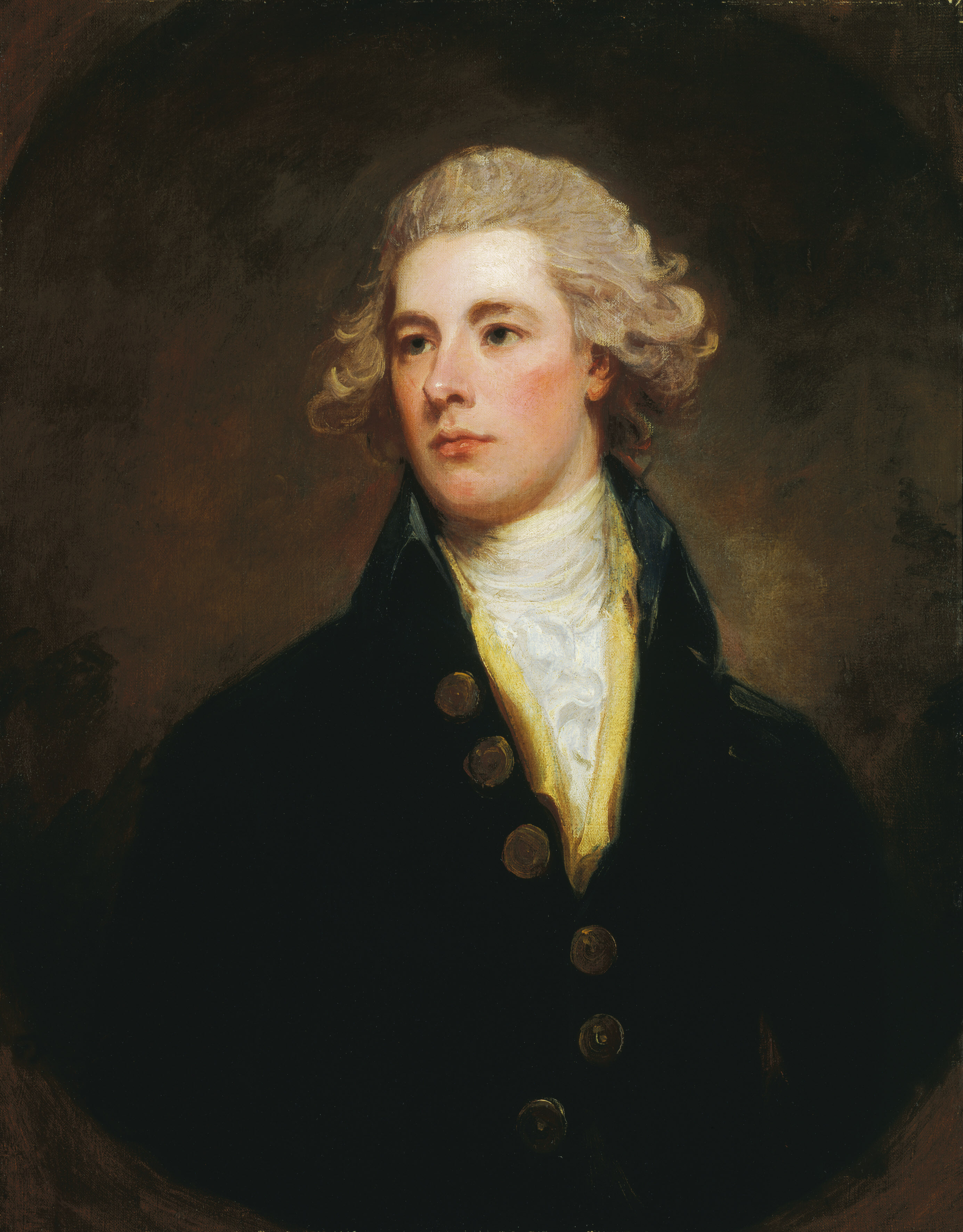

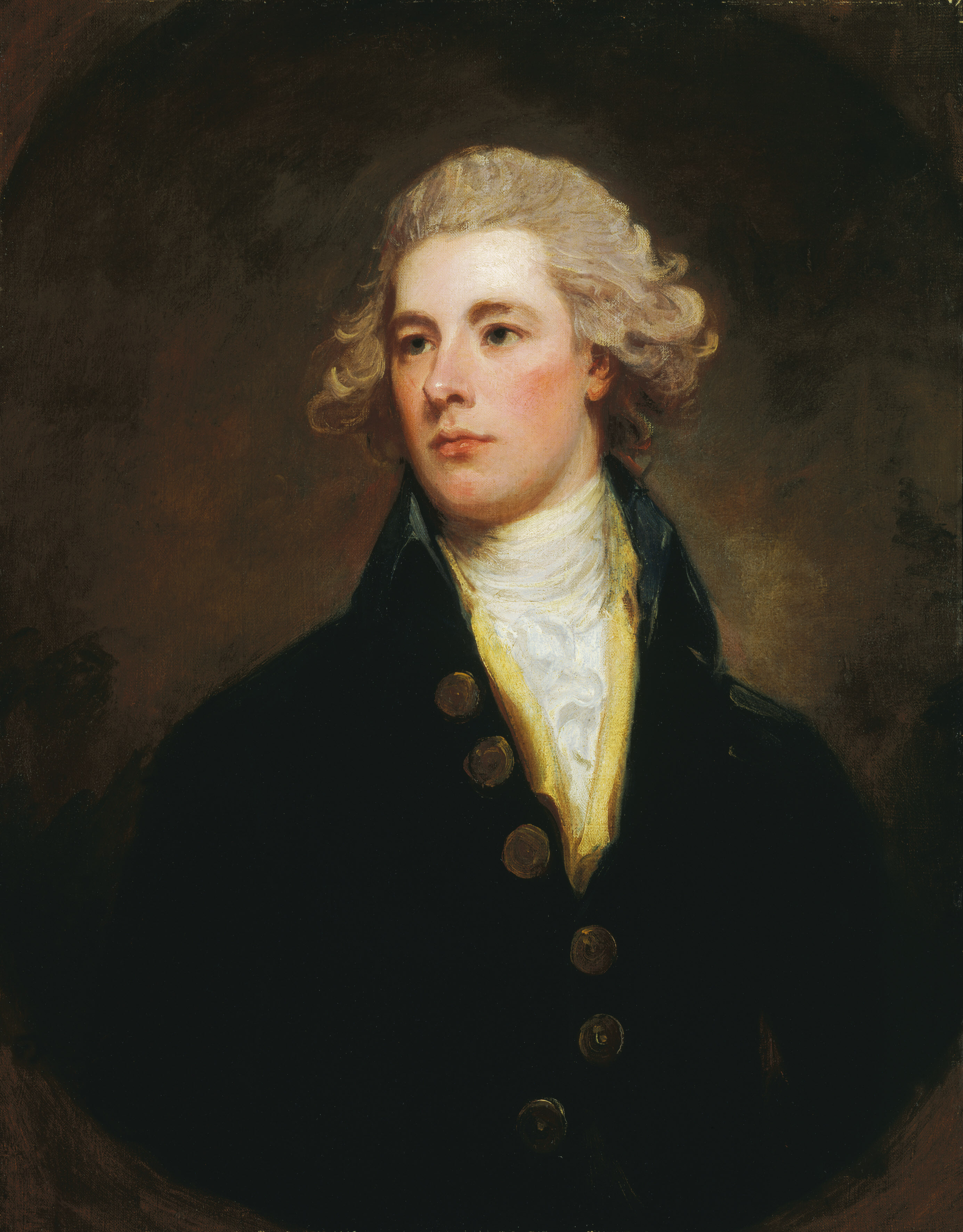

William Pitt (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman who served as the last prime minister of

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

from 1783 until the

Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of G ...

, and then first

prime minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

from January 1801. He left office in March 1801, but served as prime minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806. He was also

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

for all of his time as prime minister. He is known as "Pitt the Younger" to distinguish him from his father,

William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British Whig statesman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him "Chatham" or "Pitt the Elder" to distinguish him from his son ...

, who had also previously served as prime minister.

Pitt's prime ministerial tenure, which came during the reign of King

George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

, was dominated by major political events in Europe, including the

French Revolution and the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. Pitt, although often referred to as a

Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

, or "new Tory", called himself an "independent

Whig" and was generally opposed to the development of a strict partisan political system.

Pitt was regarded as an outstanding administrator who worked for efficiency and reform, bringing in a new generation of competent administrators. He increased taxes to pay for the great war against France and cracked down on radicalism. To counter the threat of Irish support for France, he engineered the

Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of G ...

and tried (but failed) to secure

Catholic emancipation as part of the Union. He created the "new Toryism", which revived the Tory Party and enabled it to stay in power for the next quarter-century.

The historian

Asa Briggs

Asa Briggs, Baron Briggs (7 May 1921 – 15 March 2016) was an English historian. He was a leading specialist on the Victorian era, and the foremost historian of broadcasting in Britain. Briggs achieved international recognition during his lon ...

argues that his personality did not endear itself to the British mind, for Pitt was too solitary and too colourless, and too often exuded an attitude of superiority. His greatness came in the war with France. Pitt reacted to become what

Lord Minto called "the

Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

of our reeling globe".

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

said, "For personal purity, disinterestedness and love of this country, I have never known his equal." Historian

Charles Petrie concludes that he was one of the greatest prime ministers "if on no other ground than that he enabled the country to pass from the old order to the new without any violent upheaval ... He understood the new Britain." For this he is

ranked highly amongst all British prime ministers in multiple surveys.

Pitt served as prime minister for a total of eighteen years, 343 days, making him the second-longest-serving British prime minister of all time, after

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

. At age 24, Pitt is the youngest prime minister in British history and is the youngest ever person to hold the position of prime minister in world history.

Early life

Family

William Pitt, the second son of

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British people, British British Whig Party, Whig politician, statesman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him "Chatham" or "Pit ...

, was born on 28 May 1759 at Hayes Place in the village of

Hayes,

Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

. He was from a political family on both sides, as his mother,

Hester Grenville, was sister of former prime minister

George Grenville

George Grenville (14 October 1712 – 13 November 1770) was a British Whig statesman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain, during the early reign of the young George III. He served for only two years (1763-1765), and attempted to solv ...

. According to biographer

John Ehrman, Pitt exhibited the brilliance and dynamism of his father's line, and the determined, methodical nature of the Grenvilles.

Education

Suffering from occasional poor health as a boy, he was educated at home by the Reverend Edward Wilson. An intelligent child, Pitt quickly became proficient in

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

. He was admitted to

Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 students and fellows. It is one of the university's larger colleges, with buildings from ...

, on 26 April 1773, a month before turning fourteen, going up to Cambridge in October 1773. He studied political philosophy,

classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, mathematics,

trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics concerned with relationships between angles and side lengths of triangles. In particular, the trigonometric functions relate the angles of a right triangle with ratios of its side lengths. The fiel ...

,

chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

and history. At Cambridge, Pitt was tutored by

George Pretyman Tomline, also at Pembroke College, who became a close personal friend and looked after Pitt whilst at University. Pitt later appointed Pretyman

Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of Nort ...

, then

Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

, and drew upon his advice throughout his political career. While at Cambridge, he befriended the young

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

, who became a lifelong friend and political ally in Parliament. Pitt tended to socialise only with fellow students and others already known to him, rarely venturing outside the university grounds. Yet he was described as charming and friendly. According to Wilberforce, Pitt had an exceptional wit along with an endearingly gentle sense of humour: "no man ... ever indulged more freely or happily in that playful facetiousness which gratifies all without wounding any." An example of Pitt's innocent wit was recorded by Sir John Sinclair. In the early years of Pitt's ministry there was great interest in the new young First minister. Sinclair was required to write an account of Pitt to satisfy foreign curiosity when he was abroad. At the end of a long description of Britain's eminent leader he added: ‘Of all the places where you have been, where did you fare best?’ My answer was, ‘In Poland; for the nobility live there with uncommon taste and splendour; their cooks are French,- their confectioners Italian, - and their wine Tokey.’ He immediately observed, ‘I have heard before of The Polish diet.’

In 1776, Pitt, plagued by poor health, took advantage of a little-used privilege available only to the sons of noblemen, and chose to graduate without having to pass examinations. Pitt's father was said to have insisted that his son spontaneously translate passages of classical literature orally into English, and declaim impromptu upon unfamiliar topics in an effort to develop his oratorical skills. Pitt's father, who had by then been raised to the peerage as Earl of Chatham, died in 1778. As the younger son, Pitt received only a small inheritance.In the months following the death of the Earl of Chatham, Pitt was forced to defend his father's reputation. This came about when the Bute family made claims that the late Lord had sought out the Earl of Bute with the desire to form a political coalition. Pitt although just over nineteen years of age publicly argued that this was not the case. Faced with Pitt's arguments the Bute family backed off and ceased making their claims. He acquired his legal education at

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

and was

called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in the summer of 1780.

Early political career (1780–1783)

Member of Parliament

During the general elections of September 1780, at the age of 21, Pitt contested the

University of Cambridge seat, but lost, coming bottom of the poll of the five candidates. Pitt had campaigned on his own merit, not as part of any group or with prominent backers. He explained to a friend that 'I do not wish to be thought inlisted

icin any party or to call myself anything but the Independent Whig, which in words is hardly a distinction, as every one alike pretends to it.' intent on entering Parliament, Pitt secured the patronage of

James Lowther, later 1st Earl Lowther, with the help of his university friend,

Charles Manners, 4th Duke of Rutland

Charles Manners, 4th Duke of Rutland (15 March 175424 October 1787) was a British politician and nobleman, the eldest legitimate son of John Manners, Marquess of Granby. He was styled Lord Roos from 1760 until 1770, and Marquess of Granby from ...

. Lowther effectively controlled the

pocket borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act of 1832, which had a very small electo ...

of

Appleby; a by-election in that constituency sent Pitt to the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

in January 1781. Pitt's entry into parliament is somewhat ironic as he later railed against the very same

pocket and rotten boroughs that had given him his seat.

In Parliament, the youthful Pitt cast aside his tendency to be withdrawn in public, emerging as a noted debater right from his

maiden speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

. Pitt's first speech made a dramatic impression. Sir John Sinclair, member of Parliament for Lostwithiel, thought that Pitt's first speech was never surpassed and ‘rarely equalled by any ever delivered in that assembly.’ When Pitt resumed his seat after finishing speaking there was thunderous applause. Sinclair noted that there was ‘utter astonishment … by an audience accustomed to the most splendid efforts of eloquence.’ Pitt originally aligned himself with prominent

Whigs such as

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a British British Whig Party, Whig politician and statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centurie ...

. With the Whigs, Pitt denounced the continuation of the

American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, as his father strongly had. Instead he proposed that the prime minister,

Lord North, make peace with the rebellious American colonies. Pitt also supported parliamentary reform measures, including a proposal that would have checked electoral corruption. He renewed his friendship with William Wilberforce, now

MP for

Hull, with whom he frequently met in the gallery of the House of Commons.

Chancellorship

After Lord North's ministry collapsed in 1782, the Whig

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham (13 May 1730 – 1 July 1782), styled The Honourable Charles Watson-Wentworth before 1739, Viscount Higham between 1739 and 1746, Earl of Malton between 1746 and 1750, and the Marquess of R ...

, was appointed prime minister. Pitt was offered the minor post of

Vice-Treasurer of Ireland, but he refused, considering the post overly subordinate. Lord Rockingham died only three months after coming to power; he was succeeded by another Whig,

William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (2 May 17377 May 1805), known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history, was an Anglo-Irish Whig (British political party), Whig states ...

. Many Whigs who had formed a part of the Rockingham ministry, including Fox, now refused to serve under Lord Shelburne, the new prime minister. Pitt, however, was comfortable with Shelburne, and thus joined his government; he was appointed

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

.

Fox, who became Pitt's lifelong political rival, then joined a coalition with Lord North, with whom he collaborated to bring about the defeat of the Shelburne administration. When Lord Shelburne resigned in 1783, King

George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

, who despised Fox, offered to appoint Pitt to the office of prime minister. But Pitt wisely declined, for he knew he would be incapable of securing the support of the House of Commons. The

Fox–North coalition rose to power in a government nominally headed by

William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland (14 April 173830 October 1809) was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig and then a Tories (British political party), Tory politician during the late Georgian era. He s ...

.

Pitt, who had been stripped of his post as Chancellor of the Exchequer, joined the

Opposition. He raised the issue of parliamentary reform in order to strain the uneasy Fox–North coalition, which included both supporters and detractors of reform. He did not advocate an expansion of the electoral franchise, but he did seek to address bribery and rotten boroughs. Though his proposal failed, many reformers in Parliament came to regard him as their leader, instead of Charles James Fox.

Effects of the American War of Independence

Losing the war and the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

was a shock to the British system. The war revealed the limitations of Britain's

fiscal-military state

A fiscal-military state is a state that bases its economic model on the sustainment of its armed forces, usually in times of prolonged or severe conflict. Characteristically, fiscal-military states will subject citizens to high taxation for this ...

when it had powerful enemies and no allies, depended on extended and vulnerable transatlantic lines of communication, and was faced for the first time since the 17th century by both Protestant and Catholic foes. The defeat heightened dissension and escalated political antagonism to the king's ministers. Inside parliament, the primary concern changed from fears of an over-mighty monarch to the issues of representation, parliamentary reform, and government retrenchment. Reformers sought to destroy what they saw as widespread

institutional corruption. The result was a crisis from 1776 to 1783. The peace in 1783 left France financially prostrate, while the British economy boomed due to the return of American business. That crisis ended in 1784 as a result of the king's shrewdness in outwitting Fox and renewed confidence in the system engendered by the leadership of Pitt. Historians conclude that the loss of the American colonies enabled Britain to deal with the

French Revolution with more unity and organisation than would otherwise have been the case. Britain turned towards Asia, the Pacific, and later Africa with subsequent exploration leading to the rise of the

Second British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts establish ...

.

First Premiership (1783–1801)

Rise to power

The Fox–North Coalition fell in December 1783, after Fox had introduced

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

's bill to reform the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

to gain the patronage he so greatly lacked while the king refused to support him. Fox stated the bill was necessary to save the company from bankruptcy. Pitt responded that: "Necessity is the plea for every infringement of human freedom. It is the argument of tyrants; it is the creed of slaves." The king was opposed to the bill; when it passed in the House of Commons, he secured its defeat in the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

by threatening to regard anyone who voted for it as his enemy. Following the bill's failure in the Upper House, George III dismissed the coalition government and finally entrusted the premiership to William Pitt, after having offered the position to him three times previously.

Appointment

A constitutional crisis arose when the king dismissed the Fox–North coalition government and named Pitt to replace it. Though faced with a hostile majority in Parliament, Pitt was able to solidify his position within a few months. Some historians argue that his success was inevitable given the decisive importance of monarchical power; others argue that the king gambled on Pitt and that both would have failed but for a run of good fortune.

Pitt, at the age of 24, became Great Britain's youngest prime minister ever. The contemporary satire ''

The Rolliad'' ridiculed him for his youth:

Many saw Pitt as a stop-gap appointment until some more senior statesman took on the role. However, although it was widely predicted that the new "mince-pie administration" would not outlast the Christmas season, it survived for seventeen years.

So as to reduce the power of the

Opposition, Pitt offered Charles James Fox and his allies posts in the Cabinet; Pitt's refusal to include Lord North, however, thwarted his efforts. The new government was immediately on the defensive and in January 1784 was defeated on a

motion of no confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fi ...

. Pitt, however, took the unprecedented step of refusing to resign, despite this defeat. He retained the support of the king, who would not entrust the reins of power to the Fox–North Coalition. He also received the support of the House of Lords, which passed supportive motions, and many messages of support from the country at large, in the form of petitions approving of his appointment which influenced some

Members

Member may refer to:

* Military jury, referred to as "Members" in military jargon

* Element (mathematics), an object that belongs to a mathematical set

* In object-oriented programming, a member of a class

** Field (computer science), entries in ...

to switch their support to Pitt. At the same time, he was granted the Freedom of the

City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

. When he returned from the ceremony to mark this, men of the City pulled Pitt's coach home themselves, as a sign of respect. When passing a Whig club, the coach came under attack from a group of men who tried to assault Pitt. When news of this spread, it was assumed Fox and his associates had tried to bring down Pitt by any means.

Electoral victory

Pitt gained great popularity with the public at large as "Honest Billy" who was seen as a refreshing change from the dishonesty, corruption and lack of principles widely associated with both Fox and North. Despite a series of defeats in the House of Commons, Pitt defiantly remained in office, watching the Coalition's majority shrink as some Members of Parliament left the Opposition to abstain.

In March 1784, Parliament was dissolved, and a

general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

ensued. An electoral defeat for the government was out of the question because Pitt enjoyed the support of King

George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

.

Patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

and bribes paid by the Treasury were normally expected to be enough to secure the government a comfortable majority in the House of Commons, but on this occasion, the government reaped much popular support as well. In most popular constituencies, the election was fought between candidates clearly representing either Pitt or Fox and North. Early returns showed a massive swing to Pitt with the result that many Opposition Members who still had not faced election either defected, stood down, or made deals with their opponents to avoid expensive defeats.

A notable exception came in Fox's own constituency of

Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, which contained one of the largest electorates in the country. In a contest estimated to have cost a quarter of the total spending in the entire country, Fox bitterly fought against two

Pittite

The Tories were a loosely organised political faction and later a political party, in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. They first emerged during the 1679 Exclusion Crisis, when they opposed ...

candidates to secure one of the two seats for the constituency. Great legal wranglings ensued, including the examination of every single vote cast, which dragged on for more than a year. Meanwhile, Fox sat for the Scottish pocket borough of

Tain Burghs. Many saw the dragging out of the result as being unduly vindictive on the part of Pitt and eventually the examinations were abandoned with Fox declared elected. Elsewhere, Pitt won a personal triumph when he was elected a

Member for the University of Cambridge, a constituency he had long coveted and which he would continue to represent for the remainder of his life. Pitt's new constituency suited him perfectly as he was able to act independently. Sir James Lowther's pocket borough of Appleby, which had been Pitt's previous constituency, had strings attached. Now Pitt could really be the 'independent Whig' he identified as.

First government

In domestic politics, Pitt concerned himself with the cause of

parliamentary reform

The Reform Acts (or Reform Bills, before they were passed) are legislation enacted in the United Kingdom in the 19th and 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the U ...

. In 1785, he introduced a bill to remove the representation of thirty-six

rotten and pocket boroughs

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act of 1832, which had a very small electo ...

, and to extend, in a small way, the electoral franchise to more individuals. Pitt's support for the bill, however, was not strong enough to prevent its defeat in the House of Commons. The bill of 1785 was the last parliamentary reform proposal introduced by Pitt to British legislators.

Colonial reform

His administration secure, Pitt could begin to enact his agenda. His first major piece of legislation as prime minister was the

India Act 1784, which re-organised the

British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

and kept a watch over corruption. The India Act created a new

Board of Control to oversee the affairs of the East India Company. It differed from Fox's failed India Bill 1783 and specified that the board would be appointed by the king. Pitt was appointed, along with

Lord Sydney, who was appointed

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

. The act centralised British rule in India by reducing the power of the governors of

Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

and

Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

and by increasing that of

Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805) was a British Army officer, Whig politician and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom, he is best known as one of the leading Britis ...

. Further augmentations and clarifications of the governor-general's authority were made in 1786, presumably by Lord Sydney, and presumably as a result of the company's setting up of

Penang

Penang is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia along the Strait of Malacca. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay Peninsula. Th ...

with their own superintendent (governor), Captain

Francis Light

Francis Light ( – 21 October 1794) was a British sailor and explorer best known for founding the colony of Penang and its capital city of George Town in 1786. Light was the father of William Light, who founded the city of Adelaide in South A ...

, in 1786.

Convicts were originally transported to the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

in North America, but after the

American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

ended in 1783, the newly formed United States refused to accept further convicts. Pitt's government took the decision to settle what is now

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

and found the penal colony in August 1786. The

First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

of 11 vessels carried over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts. The

Colony of New South Wales

The Colony of New South Wales was a colony of the British Empire from 1788 to 1901, when it became a State of the Commonwealth of Australia. At its greatest extent, the colony of New South Wales included the present-day Australian states of New ...

was formally proclaimed by Governor

Arthur Phillip

Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New South Wales, governor of the Colony of New South Wales.

Phillip was educated at Royal Hospital School, Gree ...

on 7 February 1788 at Sydney.

Finances

Another important domestic issue with which Pitt had to concern himself was the national debt, which had doubled to £243 million during the American war. Every year, a third of the budget of £24 million went to pay interest. Pitt sought to reduce the national debt by imposing new taxes. In 1786, he instituted a

sinking fund

A sinking fund is a fund established by an economic entity by setting aside revenue over a period of time to fund a future capital expense, or repayment of a long-term debt.

In North America and elsewhere where it is common for government entiti ...

so that £1 million a year was added to a fund so that it could accumulate interest; eventually, the money in the fund was to be used to pay off the national debt. Pitt had learned of the idea of the 'Sinking Fund' from his father in 1772. Earl Chatham had been informed of the Welshman, Sir Richard Price's idea, Pitt approved of the idea and adopted it when he was in office. By 1792, the debt had fallen to £170 million.

Pitt always paid careful attention to financial issues. A fifth of Britain's imports were smuggled in without paying taxes. He made it easier for honest merchants to import goods by lowering tariffs on easily smuggled items such as tea, wine, spirits, and tobacco. This policy raised customs revenues by nearly £2 million a year.

In 1797, Pitt was forced to protect the kingdom's gold reserves by preventing individuals from exchanging banknotes for gold. Great Britain would continue to use paper money for over two decades. Pitt also introduced Great Britain's first-ever

income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

. The new tax helped offset losses in indirect tax revenue, which had been caused by a decline in trade. Pitt's two policies of suspending cash payments and introducing Income Tax were later cited by the French Minister of Finance as being 'genius'. As they had stopped the French from destroying Britain's economy.

Foreign affairs

Pitt sought European alliances to restrict French influence, forming the

Triple Alliance with

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

and

Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

in 1788. During the

Nootka Sound Controversy in 1790, Pitt took advantage of the alliance to force Spain to give up its claim to exclusive control over the western coast of North and South America. The Alliance, however, failed to produce any other important benefits for Great Britain.

Pitt was alarmed at Russian expansion in the 1780s at the expense of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. The relations between Russia and Britain were disturbed during the

Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 by Pitt's subscription to the view of the Prussian government that the Triple Alliance could not with impunity allow the

balance of power in Eastern Europe to be disturbed. In peace talks with the Ottomans, Russia refused to return the key

Ochakov fortress. Pitt wanted to threaten military retaliation. However Russia's ambassador

Semyon Vorontsov

Count Semyon Romanovich Vorontsov (or Woronzow; ; 9 July 1832) was a Russian diplomat from the aristocratic Vorontsov family. He resided in Britain for the last 47 years of his life, from 1785 until his death in 1832, during which time he was the ...

organised Pitt's enemies and launched a public opinion campaign. Pitt had become alarmed at the opposition to his Russian policy in parliament,

Burke

Burke (; ) is a Normans in Ireland, Norman-Irish surname, deriving from the ancient Anglo-Norman and Hiberno-Norman noble dynasty, the House of Burgh. In Ireland, the descendants of William de Burgh (''circa'' 1160–1206) had the surname'' de B ...

and

Fox both uttering powerful speeches against the restoration of Ochakov to the Turks. Pitt won the vote so narrowly that he gave up. The outbreak of the

French Revolution and its attendant wars temporarily united Britain and Russia in an ideological alliance against French republicanism.

The king's condition

In 1788, Pitt faced a major crisis when the king fell victim to a mysterious illness, a form of mental disorder that incapacitated him. If the sovereign was incapable of fulfilling his constitutional duties, Parliament would need to appoint a regent to rule in his place. All factions agreed that the only viable candidate was the king's eldest son and

heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

,

George, Prince of Wales. The Prince, however, was a supporter of Charles James Fox. Had the Prince come to power, he would almost surely have dismissed Pitt. He did not have such an opportunity, however, as Parliament spent months debating legal technicalities relating to the regency. Fortunately for Pitt, the king recovered in February 1789, just after a

Regency Bill had been introduced and passed in the House of Commons.

The general elections of 1790 resulted in a majority for the government, and Pitt continued as prime minister. In 1791, he proceeded to address one of the problems facing the growing

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

: the future of

British Canada

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and cultur ...

. By the

Constitutional Act of 1791, the

province of Quebec

Quebec is Canada's largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast and a coastal border ...

was divided into two separate provinces: the predominantly French

Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada () was a British colonization of the Americas, British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence established in 1791 and abolished in 1841. It covered the southern portion o ...

and the predominantly English

Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

. In August 1792, coincident with the

capture of Louis XVI by the French revolutionaries, George III appointed Pitt as

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is the name of a ceremonial post in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but it may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the ...

, a position whose incumbent was responsible for the coastal defences of the realm. The king had in 1791 offered him a

Knighthood of the Garter, but he suggested the honour go to his

elder brother, the second Earl of Chatham.

French Revolution

An early favourable response to the French Revolution encouraged many in Great Britain to reopen the issue of parliamentary reform, which had been dormant since Pitt's reform bill was defeated in 1785. The reformers, however, were quickly labelled as radicals and associates of the French revolutionaries. Pitt, due to economic reasons, wanted to remain aloof from War with France. However, this option was taken away from him by an ultimatum from King George III. Pitt could either resign or go to war. Committed to making Britain financially stable Pitt agreed, albeit very reluctantly, to go to war against the French Revolutionaries. Though France's declaration of hostilities against Britain meant that Britain was forced into war. Subsequently, in 1794, Pitt's administration

tried three of them for treason but lost. Parliament began to enact repressive legislation in order to silence the reformers. Individuals who published

seditious material were punished, and, in 1794, the writ of

habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

was suspended. Other repressive measures included the

Seditious Meetings Act 1795, which restricted the right of individuals to assemble publicly, and the

Combination Acts, which restricted the formation of societies or organisations that favoured political reforms. Problems manning the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

also led to Pitt to introduce the

Quota System in 1795 in addition to the existing system of

impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is a type of conscription of people into a military force, especially a naval force, via intimidation and physical coercion, conducted by an organized group (hence "gang"). European nav ...

.

The war with France was extremely expensive, straining Great Britain's finances. Unlike in the latter stages of the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, at this point Britain had only a very small standing army, and thus contributed to the war effort mainly through sea power and by supplying funds to other coalition members facing France.

Ideological struggle

Throughout the 1790s, the war against France was presented as an ideological struggle between French republicanism vs. British monarchism with the British government seeking to mobilise public opinion in support of the war. The Pitt government waged a vigorous propaganda campaign contrasting the ordered society of Britain dominated by the aristocracy and the gentry vs. the "anarchy" of the French revolution and always sought to associate British "radicals" with the revolution in France. Some of the writers the British government subsidized (often from Secret Service funds) included

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

,

William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an Agrarianism, agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restr ...

,

William Playfair

William Playfair (22 September 1759 – 11 February 1823) was a Scottish engineer and political economist. The founder of graphical methods of statistics, Playfair invented several types of diagrams: in 1786 he introduced the line, area and ...

,

John Reeves, and

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

(the last through the pension granted him in 1762).

Though the Pitt government did drastically reduce civil liberties and created a nationwide spy network with ordinary people being encouraged to denounce any "radicals" that might be in their midst, the historian

Eric J. Evans argued the picture of Pitt's "reign of terror" as portrayed by the Marxist historian

E.P. Thompson is incorrect, stating there is much evidence of a "popular conservative movement" that rallied in defence of King and Country. Evans wrote that there were about 200 prosecutions of "radicals" suspected of sympathy with the French revolution in British courts in the 1790s, which was much less than the prosecutions of suspected Jacobites after the rebellions of 1715 and 1745.

However, the spy network maintained by the government was efficient. In

Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

's novel ''

Northanger Abbey

''Northanger Abbey'' ( ) is a coming-of-age novel and a satire of Gothic fiction, Gothic novels written by the English author Jane Austen. Although the title page is dated 1818 and the novel was published posthumously in 1817 with ''Persuasio ...

'', which was written in the 1790s, but not published until 1817, one of the characters remarks that it is not possible for a family to keep secrets in these modern times when spies for the government were lurking everywhere. This comment captures well the tense, paranoid atmosphere of the 1790s, when people were being encouraged to report "radicals" to the authorities.

Saint-Domingue

In 1793, Pitt approved plans to capture the French colony of

Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

, which had been in a state of unrest since a

1791 slave rebellion. Its capture would provide a bargaining chip for future negotiations with France and prevent similar unrest in the

British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British Empire, British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barb ...

. Planters in the British West Indies were greatly disturbed by events in Saint-Domingue, and many pressured the Pitt ministry to invade the colony. On 20 September 1793, a British invasion force sent from

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

landed in

Jérémie

Jérémie (; ) is a commune and capital city of the Grand'Anse department in Haiti. It had a population of about 134,317 at the 2015 census. It is relatively isolated from the rest of the country. The Grande-Anse River flows near the city.

...

, where they were greeted with cheers by the city's white population. Two days later, another British force under Commodore

John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), better known as John Ford, was an American film director and producer. He is regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers during the Golden Age of Hollywood, and w ...

took

Môle-Saint-Nicolas without a fight. However, British attempts to expand into the rest of the colony were frustrated by a lack of troops and

yellow fever. As commissioners sent by the French Republic to Saint-Domingue had abolished slavery, an institution legal in areas of the colony under British occupation, most of Saint-Domingue's Black inhabitants rallied to the Republican cause. An undeterred Pitt launched what he called the "great push" in 1795, sending out an even larger expedition.

In November 1795, some 218 ships left Portsmouth for Saint-Domingue. After the failure of the

Quiberon expedition earlier in 1795, when the British landed a force of French royalists on the coast of France who were annihilated by the

French Revolutionary Army

The French Revolutionary Army () was the French land force that fought the French Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1802. In the beginning, the French armies were characterised by their revolutionary fervour, their poor equipment and their great nu ...

, Pitt had decided it was crucial for Britain to take Saint-Domingue, no matter what the cost in lives and money, to improve Britain's negotiating hand when it came time to make peace with the French Republic. British historian Michael Duffy argued that since Pitt committed far more manpower and money to the Caribbean expeditions, especially the one to Saint-Domingue, than he ever did to Europe in the years 1793–1798, it is proper to view the West Indies as Britain's main theatre of war and Europe as more of a sideshow. By 1795, half of the British Army was in the West Indies (with the largest contingent in Saint-Domingue), with the rest being divided among Europe, India and North America.

As the British death toll, largely caused by yellow fever, continued to climb, Pitt was criticised in the House of Commons. Several MPs suggested it might be better to abandon the expedition, but Pitt insisted that Britain had given its word of honour that it would protect allied French colonists in Saint-Domingue. In 1797, Colonel

Thomas Maitland arrived in Saint-Domingue and quickly realised the British position there was untenable. He negotiated a withdrawal with Governor-General

Toussaint Louverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (, ) also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda (20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803), was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louvertu ...

and the last British troops left the colony on 31 August 1798. The invasion had cost the British treasury 4 million pounds (roughly £ million in ) and resulted in the deaths of roughly 50,000 soldiers and sailors in British service, mostly through disease, with another 50,000 no longer fit for service. British historian Sir

John William Fortescue wrote that Pitt and his cabinet had tried to destroy French power "in these pestilent islands ... only to discover, when it was too late, that they practically destroyed the British army". Fortescue wrote that the British troops who served in Saint-Domingue were "victims of imbecility".

Ireland

Pitt maintained close control over Ireland. The Lord Lieutenants were to follow his policy of Protestant control and very little reform for the Catholic majority. When the opposition Portland group joined Pitt's ministry, splitting the Foxite opposition, Pitt was put in a difficult situation. He wanted to replace his friend Westmorland, who was Lord Lieutenant, with Lord Camden, whom he could trust. However, one of Portland's group, Earl Fitzwilliam, wanted the position. Pitt, to keep Portland on side, appointed Fitzwilliam but allowed the new Lord Lieutenant to believe that he had free range to reform the government in Ireland. Thus, when Fitzwilliam's reforms became public in London he was quickly recalled and Camden replaced him. This ensured Pitt had his man in Dublin Castle, whilst also retaining Portland and his group. The unfortunate effect was to produce optimism amongst Irish Catholics who wanted political reform. In May 1798, the long-simmering unrest in Ireland exploded into outright rebellion with the

United Irishmen Society launching a revolt to win independence for Ireland. Pitt took an extremely repressive approach to the United Irishmen with the Crown executing about 1,500 United Irishmen after the revolt. The revolt of 1798 destroyed Pitt's faith in the governing competence of the Dublin parliament (dominated by

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy (also known as the Ascendancy) was the sociopolitical and economical domination of Ireland between the 17th and early 20th centuries by a small Anglicanism, Anglican ruling class, whose members consisted of landowners, ...

families). Thinking a less sectarian and more conciliatory approach would have avoided the uprising, Pitt

sought an Act of Union that would make Ireland an official part of the United Kingdom and end the "

Irish Question". The French expeditions to Ireland in 1796 and 1798 (to support the United Irishmen) were regarded by Pitt as near-misses that might have provided an Irish base for French attacks on Britain, thus making the "Irish Question" a national security matter. As the

Dublin parliament did not wish to disband, Pitt made generous use of what would now be called "

pork barrel politics

''Pork barrel'', or simply ''pork'', is a metaphor for Appropriation (law), allocating government spending to localized projects in the representative's district or for securing direct expenditures primarily serving the sole interests of the r ...

" to bribe Irish MPs to vote for the Act of Union.

Throughout the 1790s, the popularity of the

Society of United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

grew. Influenced by the American and French revolutions, this movement demanded independence and republicanism for Ireland. The United Irishmen Society was very anti-clerical, being equally opposed to the "superstitions" promoted by both the Church of England and the Roman Catholic church, which caused the latter to support the Crown. Realising that the Catholic church was an ally in the struggle against the French Revolution, Pitt had tried fruitlessly to persuade the Dublin parliament to loosen the anti-Catholic laws to "keep things quiet in Ireland". Pitt's efforts to soften the anti-Catholic laws failed in the face of determined resistance from the families of the

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy (also known as the Ascendancy) was the sociopolitical and economical domination of Ireland between the 17th and early 20th centuries by a small Anglicanism, Anglican ruling class, whose members consisted of landowners, ...

in Ireland, who forced Pitt to recall

Earl Fitzwilliam as

Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British Dublin Castle administration, administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretar ...

in 1795, when the latter had indicated he would support a bill for Catholic relief. In fact, the actions of Fitzwilliam had been encouraged by Pitt who wanted an excuse to remove Fitzwilliam and replace him with the Earl of Camden, however, Pitt had managed this feat without witnesses. Pitt was very much opposed to Catholic relief and the repeal of their political disabilities which were contained in the Test and Corporation Laws. In much of rural Ireland, law and order had broken down as an economic crisis further impoverished the already poor Irish peasantry, and a sectarian war with many atrocities on both sides had begun in 1793 between Catholic "

Defenders

Defender(s) or The Defender(s) may refer to:

* Defense (military)

* Defense (sports)

** Defender (association football)

Arts and entertainment Film, television, and theatre Film

* ''The Defender'' (1989 film), a Canadian documentary

* ''The D ...

" versus Protestant "

Peep o' Day Boys". A section of the Peep o'Day Boys who had renamed themselves the

Loyal Orange Order in September 1795 were fanatically committed to upholding Protestant supremacy in Ireland at "almost any cost". In December 1796, a French invasion of Ireland led by General

Lazare Hoche

Louis Lazare Hoche (; 24 June 1768 – 19 September 1797) was a French military leader of the French Revolutionary Wars. He won a victory over Royalist forces in Brittany. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on ...

(scheduled to coordinate with a rising of the United Irishmen) was only

thwarted by bad weather. To crush the United Irishmen, Pitt sent

General Lake to

Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

in 1797 to call out

Protestant Irish militiamen and organised an intelligence network of spies and informers.

Spithead mutiny

In April 1797, the

mutiny of the entire Spithead fleet shook the government (sailors demanded a pay increase to match inflation). This mutiny occurred at the same moment that the Franco-Dutch alliance were preparing an invasion of Britain. To regain control of the fleet, Pitt agreed to navy pay increases and had

George III pardon the mutineers. By contrast, the more political "floating republic"

naval mutiny at the Nore in June 1797 led by

Richard Parker was handled more repressively. Pitt refused to negotiate with Parker, whom he wanted to see hanged as a mutineer. In response to the 1797 mutinies, Pitt passed the

Incitement to Mutiny Act 1797 making it unlawful to advocate breaking oaths to the Crown. In 1798, he passed the Defence of the Realm act, which further restricted civil liberties. Despite the major concerns to Britain's defences when the navy mutinied Pitt remained calm and in control. He was confident that the matter would be resolved. Lord Spencer, the First Lord of the Admiralty recalled how calm Pitt was. Very late one evening after visiting the Minister with desperate news of the fleet, as Spencer proceeded away from Downing Street, he remembered he had some more information to give to Pitt. He immediately returned to Number 10 only to be informed that Pitt was fast asleep. Henry Dundas, who was President of the Board of Control, Treasurer of the Navy, Secretary at War and a close friend of Pitt, envied the First Minister for his ability to sleep well in all crcumstances.

Failure

Despite Pitt's efforts, the French continued to defeat the

First Coalition, which collapsed in 1798. A

Second Coalition, consisting of Great Britain,

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

,

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, was formed, but it, too, failed to overcome the French. The fall of the Second Coalition with the defeat of the Austrians at the

Battle of Marengo (14 June 1800) and at the

Battle of Hohenlinden

The Battle of Hohenlinden was fought on 3 December 1800 during the French Revolutionary Wars. A French First Republic, French army under Jean Victor Marie Moreau won a decisive victory over an Habsburg monarchy, Austrian and Electorate of Bavar ...

(3 December 1800) left Great Britain facing France alone.

Resignation

Following the

Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of G ...

, Pitt sought to inaugurate the new

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

by granting concessions to Roman Catholics, who formed a 75% majority of the population in Ireland, by abolishing various political restrictions under which they suffered. The king was strongly opposed to

Catholic emancipation; he argued that to grant additional liberty would violate

his coronation oath, in which he had promised to protect the established

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. Pitt, unable to change the king's strong views, resigned on 16 February 1801 so as to allow

Henry Addington

Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth (30 May 175715 February 1844) was a British Tories (British political party), Tory statesman who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1804 and as Speaker of the House of Commons (U ...

, his political friend, to form a new administration. At about the same time, however, the king suffered a renewed bout of madness, with the consequence that Addington could not receive his formal appointment. Though he had resigned, Pitt temporarily continued to discharge his duties; on 18 February 1801, he brought forward the annual budget. Power was transferred from Pitt to Addington on 14 March, when the king recovered.

Opposition (1801–1804)

Backbencher

Shortly after leaving office, Pitt supported the new administration under Addington, but with little enthusiasm; he frequently absented himself from Parliament, preferring to remain in his

Lord Warden's residence of

Walmer Castle

Walmer Castle is an artillery fort originally constructed by Henry VIII in Walmer, Kent, between 1539 and 1540. It formed part of the King's Device Forts, Device programme to protect against invasion from France and the Holy Roman Empire, and ...

—before 1802 usually spending an annual late-summer holiday there, and later often present from the spring until the autumn.

From the castle, he helped organise a local

Volunteer Corps in anticipation of a French invasion, acted as colonel of a battalion raised by

Trinity House—he was also a Master of Trinity House—and encouraged the construction of

Martello tower

Martello towers are small defensive forts that were built across the British Empire during the 19th century, from the time of the French Revolutionary Wars onwards. Most were coastal forts.

They stand up to high (with two floors) and typica ...

s and the

Royal Military Canal in

Romney Marsh

Romney Marsh is a sparsely populated wetland area in the counties of Kent and East Sussex in the south-east of England. It covers about . The Marsh has been in use for centuries, though its inhabitants commonly suffered from malaria until the ...

. He rented land abutting the Castle to farm on which to lay out trees and walks. His niece

Lady Hester Stanhope

Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope (12 March 1776 – 23 June 1839) was a British adventurer, writer, antiquarian, and one of the most famous travellers of her age. Her excavation of Ascalon in 1815 is considered the first to use modern Archaeology ...

designed and managed the gardens and acted as his hostess.

The

Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France, the Spanish Empire, and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it set t ...

in 1802 between France and Britain marked the end of the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

. Everyone expected it to be only a short truce. By 1803, war had broken out again with French Consulate, France under Napoleon Bonaparte. Although Addington had previously invited him to join the Cabinet, Pitt preferred to join the Opposition, becoming increasingly critical of the government's policies. Addington, unable to face the combined opposition of Pitt and Fox, saw his majority gradually evaporate and resigned in late April 1804.

Second premiership (1804–1806)

Reappointment

Pitt finally returned to the premiership on 10 May 1804. He had originally planned to form a broad coalition government, with both the Tories and Whigs under one government.

But Pitt faced the opposition of George III to the inclusion of Fox, due to the king's dislike. Moreover, many of Pitt's former supporters, including the allies of Addington, joined the Opposition. Thus, Pitt's second ministry was considerably weaker than his first.

Nevertheless, Pitt formed Second Pitt ministry, a second government which consisted of largely Tories (British political faction), Tory members with some former ministers of the previous ministry. These include John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, Lord Eldon as Lord Chancellor, former Foreign Secretary Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, Lord Hawkesbury as Secretary of State for the Home Department, Home Secretary, Dudley Ryder, 1st Earl of Harrowby, Lord Harrowby as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (UK), Foreign Secretary, former prime ministers William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, Duke of Portland and Addington as Lord Privy Seal and Lord President of the Council, with Pitt's prominent allies Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, the Viscount Melville and Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, Lord Castlereagh as First Lord of the Admiralty and Secretary of State for the Colonies, respectively.

Second government

Resuming war

By the time Pitt became prime minister in 1804, the war in Europe had been escalating for sometime since the Treaty of Amiens, peace of Amiens in 1801 and in 1803 the War of the Third Coalition began.

Pitt's new government resumed the war effort yet again to confront the French and to defeat Napoleon. Pitt had initially allied Britain with

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

,

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

and

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and now renewed the alliance with Austria Prussia and Russia against Napoleonic France and its allies.

The British government began placing pressure on the French Emperor, Napoleon I. By imposing sanctions, putting up a blockade across the English Channel and undermining French naval activities, Pitt's efforts proved a success and thanks to his efforts, the United Kingdom joined the Third Coalition, an alliance that included Austria, Russia, and Sweden.

In October 1805, the British Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, won a crushing victory in the Battle of Trafalgar, ensuring British naval supremacy for the remainder of the war. At the annual Lord Mayor of London, Lord Mayor's Banquet toasting him as "the Saviour of Europe", Pitt responded in a few words that became the most famous speech of his life:

Nevertheless, the Coalition collapsed, having suffered significant defeats at the Battle of Ulm (October 1805) and the Battle of Austerlitz (December 1805). After hearing the news of Austerlitz, Pitt referred to a map of Europe, "Roll up that map; it will not be wanted these ten years."

Finances

Pitt was an expert in finance and served as chancellor of the exchequer. Critical to his success in confronting Napoleon was using Britain's superior economic resources. He was able to mobilise the nation's industrial and financial resources and apply them to defeating France.

With a population of 16 million, the United Kingdom was barely half the size of France, which had a population of 30 million. In terms of soldiers, however, the French numerical advantage was offset by British subsidies that paid for a large proportion of the Austrian and Russian soldiers, peaking at about 450,000 in 1813.

Britain used its economic power to expand the Royal Navy, doubling the number of frigates and increasing the number of the larger ships of the line by 50%, while increasing the roster of sailors from 15,000 to 133,000 in eight years after the war began in 1793. The British national output remained strong, and the well-organised business sector channelled products into what the military needed. France, meanwhile, saw its navy shrink by more than half. The system of smuggling finished products into the continent undermined French efforts to ruin the British economy by cutting off markets.

By 1814, the budget that Pitt in his last years had largely shaped had expanded to £66 million, including £10 million for the Navy, £40 million for the Army, £10 million for the Allies, and £38 million as interest on the national debt. The national debt soared to £679 million, more than Debt-to-GDP ratio, double the GDP. It was willingly supported by hundreds of thousands of investors and tax payers, despite the higher taxes on land and a new income tax.

The whole cost of the war came to £831 million. The French financial system was inadequate and Napoleon's forces had to rely in part on requisitions from conquered lands.

Death

The setbacks took a toll on Pitt's health. He had long suffered from poor health, beginning in childhood, and was plagued with gout and "biliousness", which was worsened by a fondness for port wine, port that began when he was advised to consume it to deal with his chronic ill health. On 23 January 1806, Pitt died at Bowling Green House on Putney, Putney Heath, probably from peptic ulceration of his stomach or duodenum; he was unmarried and left no children.

Pitt's debts amounted to £40,000 () when he died, but Parliament agreed to pay them on his behalf.

A motion was made to honour him with a public funeral and a monument; it passed despite some opposition. Pitt's body was buried in Westminster Abbey on 22 February, having lain in state for two days in the Palace of Westminster.

Pitt was succeeded as prime minister by his first cousin William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, who headed the Ministry of All the Talents, a coalition which included Charles James Fox.

Personal life

Pitt became known as a "three-bottle man" in reference to his heavy consumption of port wine. Each of these bottles would be around in volume.

At one point rumours emerged of an intended marriage to Eleanor Eden, to whom Pitt had grown close. Pitt broke off the potential marriage in 1797, writing to her father, William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland, Lord Auckland, "I am compelled to say that I find the obstacles to it decisive and insurmountable".

Of his social relationships, biographer William Hague writes:

Pitt was happiest among his Cambridge companions or family. He had no social ambitions, and it was rare for him to set out to make a friend. The talented collaborators of his first 18 months in office—Beresford, Wyvil and Twining—passed in and out of his mind along with their areas of expertise. Pitt's lack of interest in enlarging his social circle meant that it did not grow to encompass any women outside his own family, a fact that produced a good deal of rumour. From late 1784, a series of satirical verses appeared in ''The Morning Herald'' drawing attention to Pitt's lack of knowledge of women: "Tis true, indeed, we oft abuse him,/Because he bends to no man;/But slander's self dares not accuse him/Of stiffness to a woman."