William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth

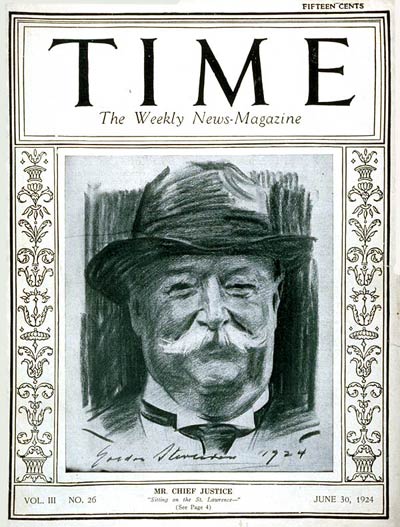

chief justice of the United States

The chief justice of the United States is the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States and is the highest-ranking officer of the U.S. federal judiciary. Appointments Clause, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution g ...

from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices.

Taft was born in

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Ohio. His father,

Alphonso Taft, was a

U.S. attorney general and

secretary of war

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. Taft attended

Yale and joined

Skull and Bones, of which his father was a founding member. After becoming a lawyer, Taft was appointed a judge while still in his twenties. He continued a rapid rise, being named

solicitor general and a judge of the

Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. In 1901, President

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

appointed Taft

civilian governor of the Philippines. In 1904, President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

made him Secretary of War, and he became Roosevelt's hand-picked successor. Despite his personal ambition to become chief justice, Taft declined repeated offers of appointment to the

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

, believing his political work to be more important.

With Roosevelt's help, Taft had little opposition for the Republican nomination for president in 1908 and easily defeated

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

for the presidency in that November's

election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

. As president, he

focused on East Asia more than European affairs and repeatedly intervened to prop up or remove Latin American governments. Taft sought reductions to trade

tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

s, then a major source of governmental income, but the resulting bill was heavily influenced by special interests. His administration was filled with conflict between the Republican Party's conservative wing, with which Taft often sympathized, and its progressive wing, toward which Roosevelt moved more and more. Controversies

over conservation and

antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

cases filed by the Taft administration served to further separate the two men. The

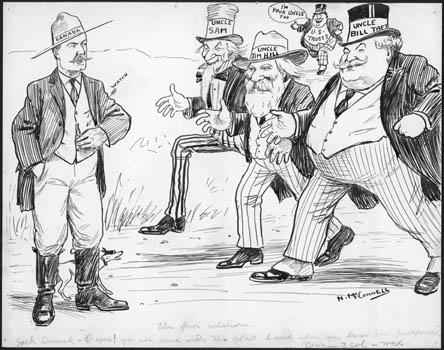

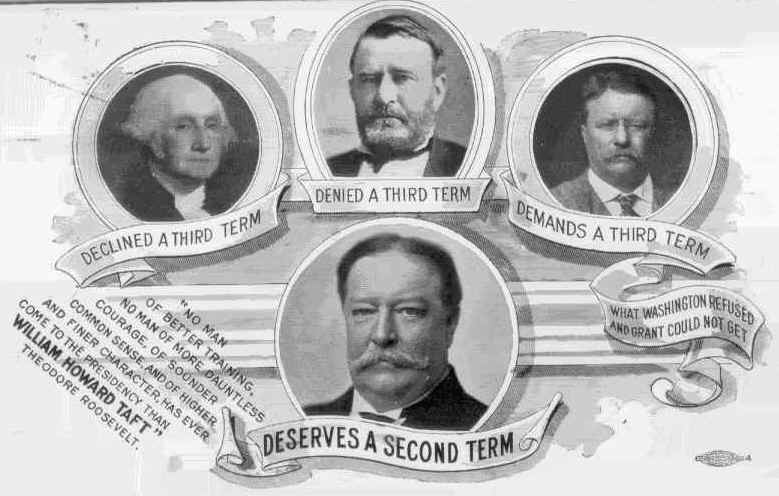

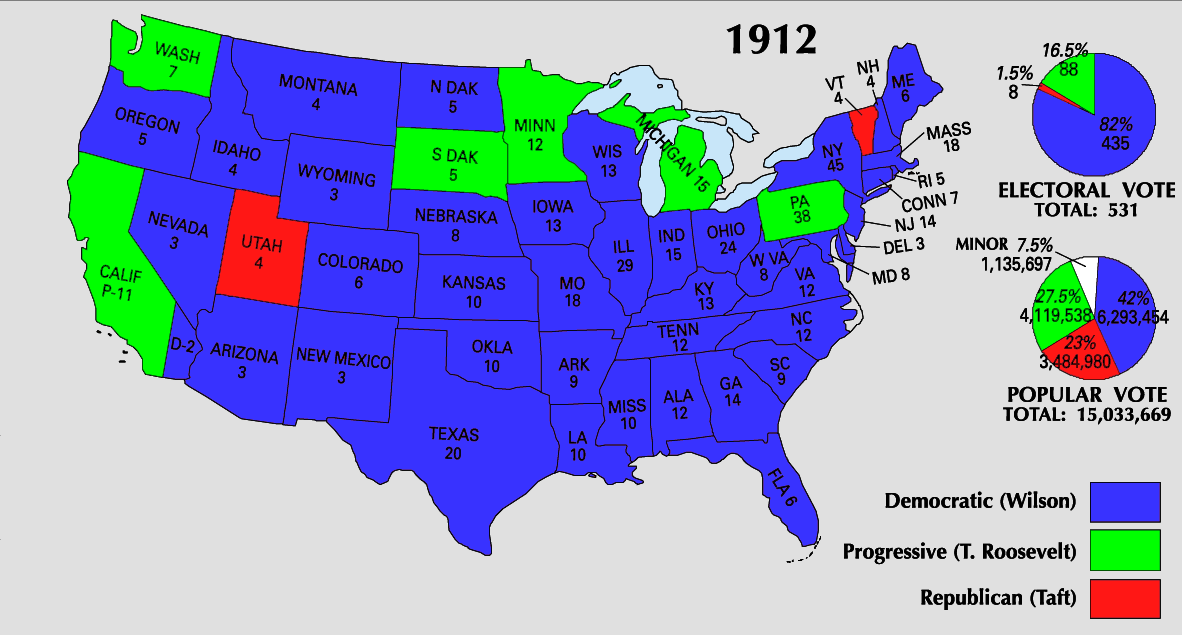

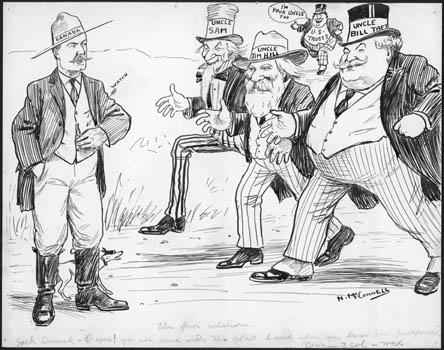

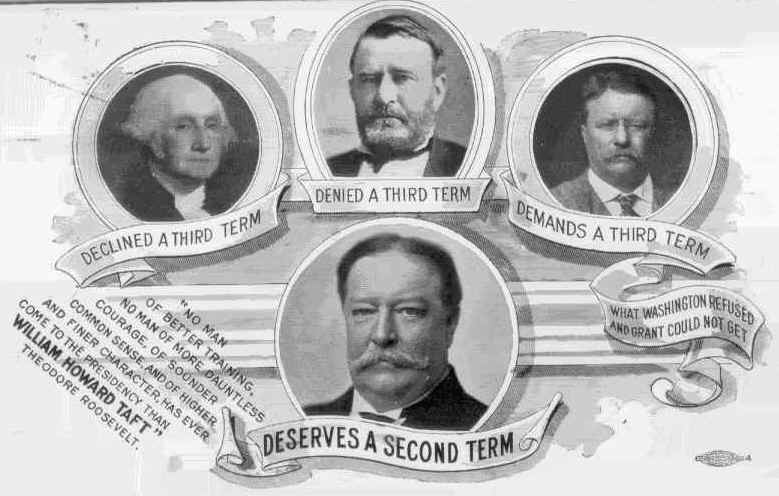

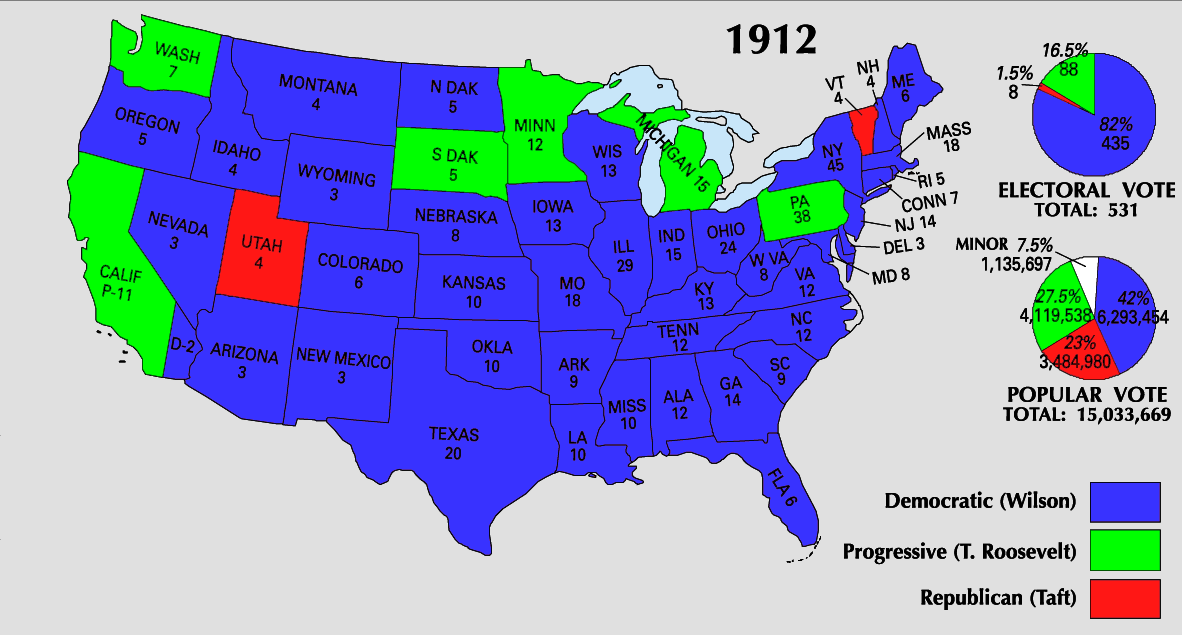

1912 presidential election was a three-way race, as Roosevelt challenged Taft for renomination. Taft used his control of the party machinery to gain a bare majority of delegates and Roosevelt bolted the party. The split left Taft with little chance of reelection, and he took only Utah and Vermont in his loss to Democratic nominee

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

.

After leaving office, Taft returned to Yale as a professor, continuing his political activity and working against war through the

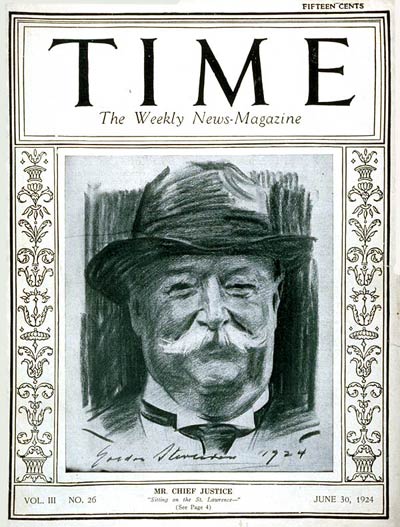

League to Enforce Peace. In 1921, President

Warren G. Harding appointed Taft chief justice, an office he had long sought. Chief Justice Taft was a conservative on business issues, and under him there were advances in individual rights. In poor health, he resigned in February 1930, and died the following month. He was buried at

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

, the first president and first Supreme Court justice to be interred there. Taft is generally listed near the middle in

historians' rankings of U.S. presidents.

Early life and education

William Howard Taft was born September 15, 1857, in

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Ohio, to

Alphonso Taft and

Louise Torrey.

The

Taft family lived in the suburb of

Mount Auburn. Alphonso served as a judge and an ambassador, and was

U.S. Secretary of War and

Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

under President

Ulysses S. Grant.

William Taft was not seen as brilliant as a child, but was a hard worker; his demanding parents pushed him and his four brothers toward success, tolerating nothing less. He attended

Woodward High School in Cincinnati. At

Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

, which he entered in 1874, the heavyset, jovial Taft was popular and an intramural heavyweight wrestling champion. One classmate said he succeeded through hard work rather than by being the smartest, and had integrity. He was elected a member of

Skull and Bones, the Yale secret society co-founded by his father, one of three future presidents (with

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

and

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

) to be a member. In 1878, Taft graduated second in his class of 121.

He attended

Cincinnati Law School, and graduated with a

Bachelor of Laws

A Bachelor of Laws (; LLB) is an undergraduate law degree offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree and serves as the first professional qualification for legal practitioners. This degree requires the study of core legal subje ...

in 1880. While in law school, he worked on ''The Cincinnati Commercial'' newspaper,

edited by

Murat Halstead. Taft was assigned to cover the local courts, and also spent time

reading law in his father's office; both activities gave him practical knowledge of the law that was not taught in class. Shortly before graduating from law school, Taft went to

Columbus to take the

bar examination

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associat ...

and easily passed.

Rise in government (1880–1908)

Ohio lawyer and judge

After admission to the

Ohio bar, Taft devoted himself to his job at the ''Commercial'' full-time. Halstead was willing to take him on permanently at an increased salary if he would give up the law, but Taft declined. In October 1880, Taft was appointed assistant prosecutor for

Hamilton County, Ohio, where Cincinnati is. He took office in January 1881. Taft served for a year as assistant prosecutor, trying his share of routine cases. He resigned in January 1882 after President

Chester A. Arthur appointed him Collector of Internal Revenue for Ohio's First District, an area centered on Cincinnati. Taft refused to dismiss competent employees who were politically out of favor, and resigned effective in March 1883, writing to Arthur that he wished to begin private practice in Cincinnati. In 1884, Taft campaigned for the Republican candidate for president, Maine Senator

James G. Blaine, who lost to New York Governor

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

.

In 1887, Taft, then aged 29, was appointed to a vacancy on the Superior Court of Cincinnati by Governor

Joseph B. Foraker. The appointment was good for just over a year, after which he would have to face the voters, and in April 1888, he sought election for the first of three times in his lifetime, the other two being for the presidency. He was elected to a full five-year term. Some two dozen of Taft's opinions as a state judge survive, the most significant being ''Moores & Co. v. Bricklayers' Union No. 1'' (1889) if only because it was used against him when he ran for president in 1908. The case involved bricklayers who refused to work for any firm that dealt with a company called Parker Brothers, with which they were in dispute. Taft ruled that the union's action amounted to a

secondary boycott, which was illegal.

It is not clear when Taft met

Helen Herron (often called Nellie), but it was no later than 1880, when she mentioned in her diary receiving an invitation to a party from him. By 1884, they were meeting regularly, and in 1885, after an initial rejection, she agreed to marry him. The wedding took place at the Herron home on June 19, 1886. William Taft remained devoted to his wife throughout their almost 44 years of marriage. Nellie Taft pushed her husband much as his parents had, and she could be very frank with her criticisms. The couple had three children, of whom the eldest,

Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, prais ...

, became a U.S. senator.

Solicitor General

There was a seat vacant on the

U.S. Supreme Court in 1889, and Governor Foraker suggested President Harrison appoint Taft to fill it. Taft was 32 and his professional goal was always a seat on the Supreme Court. He actively sought the appointment, writing to Foraker to urge the governor to press his case, while stating to others it was unlikely he would get it. Instead, in 1890, Harrison appointed him

Solicitor General of the United States. When Taft arrived in Washington in February 1890, the office had been vacant for two months, with the work piling up. He worked to eliminate the backlog, while simultaneously educating himself on federal law and procedure he had not needed as an Ohio state judge.

New York Senator

William M. Evarts, a former Secretary of State, had been a classmate of Alphonso Taft at Yale. Evarts called to see his friend's son as soon as Taft took office, and William and Nellie Taft were launched into Washington society. Nellie Taft was ambitious for herself and her husband, and was annoyed when the people he socialized with most were mainly Supreme Court justices, rather than the arbiters of Washington society such as

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

,

John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a Secretary to the President of the United States, private secretary for Abraha ...

,

Henry Cabot Lodge and their wives.

In 1891, Taft introduced a new policy:

confession of error, by which the U.S. government would concede a case in the Supreme Court that it had won in the court below but that the solicitor general thought it should have lost. At Taft's request, the Supreme Court reversed a murder conviction that Taft said had been based on inadmissible evidence. The policy continues to this day.

Although Taft was successful as Solicitor General, winning 15 of the 18 cases he argued before the Supreme Court,

he was glad when in March 1891, the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

created a new judgeship for each of the

United States Courts of Appeal and Harrison appointed him to the

Sixth Circuit, based in Cincinnati. In March 1892, Taft resigned as Solicitor General to resume his judicial career.

Federal judge

Taft's

federal judgeship was a lifetime appointment, and one from which promotion to the Supreme Court might come. Taft's older half-brother

Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

, successful in business, supplemented Taft's government salary, allowing William and Nellie Taft and their family to live in comfort. Taft's duties involved hearing trials in the circuit, which included Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and participating with Supreme Court Justice

John Marshall Harlan, the

circuit justice, and judges of the Sixth Circuit in hearing appeals. Taft spent these years, from 1892 to 1900, in personal and professional contentment.

According to historian Louis L. Gould, "while Taft shared the fears about social unrest that dominated the middle classes during the 1890s, he was not as conservative as his critics believed. He supported the right of labor to organize and strike, and he ruled against employers in several negligence cases."

Among these was ''Voight v. Baltimore & Ohio Southwestern Railway Co.'' Taft's decision for a worker injured in a railway accident violated the contemporary doctrine of

liberty of contract, and he was reversed by the Supreme Court. On the other hand, Taft's opinion in ''

United States v. Addyston Pipe and Steel Co.'' was upheld unanimously by the high court. Taft's opinion, in which he held that a pipe manufacturers' association had violated the

Sherman Antitrust Act, was described by

Henry Pringle, his biographer, as having "definitely and specifically revived" that legislation.

In 1896, Taft became dean and Professor of

Property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, re ...

at his ''alma mater'', the Cincinnati Law School, a post that required him to prepare and give two hour-long lectures each week. He was devoted to his law school, and was deeply committed to legal education, introducing the

case method to the curriculum. As a federal judge, Taft could not involve himself with politics, but followed it closely, remaining a Republican supporter. He watched with some disbelief as

the campaign of Ohio Governor

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

developed in 1894 and 1895, writing "I cannot find anybody in Washington who wants him". By March 1896, Taft realized that McKinley would likely be nominated, and was lukewarm in his support. He landed solidly in McKinley's camp after former Nebraska representative

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

in July stampeded the

1896 Democratic National Convention with his

Cross of Gold speech. Bryan, both in that address and in

his campaign, strongly advocated

free silver, a policy that Taft saw as economic radicalism. Taft feared that people would hoard gold in anticipation of a Bryan victory, but he could do nothing but worry. McKinley

was elected; when a place on the Supreme Court opened in 1898, the only one under McKinley, the president named

Joseph McKenna.

From the 1890s until his death, Taft played a major role in the international legal community. He was active in many organizations, was a leader in the worldwide

arbitration movement, and taught international law at the Yale Law School. Taft advocated the establishment of a world court of arbitration supported by an international police force and is considered a major proponent of "world peace through law" movement. One of the reasons for his bitter break with Roosevelt in 1910–12 was Roosevelt's insistence that arbitration was naïve and that only war could decide major international disputes.

Philippine years

In January 1900, Taft was called to Washington to meet with McKinley. Taft hoped a Supreme Court appointment was in the works, but instead McKinley wanted to place Taft on

the commission to organize a civilian government in the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. The appointment would require Taft's resignation from the bench; the president assured him that if he fulfilled this task, McKinley would appoint him to the next vacancy on the high court. Taft accepted on condition he was made head of the commission, with responsibility for success or failure; McKinley agreed, and Taft sailed for the islands in April 1900.

The American takeover meant the

Philippine Revolution

The Philippine Revolution ( or ; or ) was a war of independence waged by the revolutionary organization Katipunan against the Spanish Empire from 1896 to 1898. It was the culmination of the 333-year History of the Philippines (1565–1898), ...

bled into the

Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

, as Filipinos fought for their independence, but U.S. forces, led by military governor General

Arthur MacArthur Jr. had the upper hand by 1900. MacArthur felt the commission was a nuisance, and their mission a quixotic attempt to impose self-government on a people unready for it. The general was forced to co-operate with Taft, as McKinley had given the commission control over the islands' military budget. The commission took executive power in the Philippines on September 1, 1900; on July 4, 1901, Taft became civilian

governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

. MacArthur, until then the military governor, was relieved by General

Adna Chaffee, who was designated only as commander of American forces. As Governor-General, Taft oversaw the final months of the primary phase of the Philippine–American War. He approved of General

James Franklin Bell's use of

concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

s in the provinces of

Batangas and

Laguna, and accepted the surrender of Filipino general

Miguel Malvar on April 16, 1902.

Taft sought to make the Filipinos partners in a venture that would lead to their self-government; he saw independence as something decades off. Many Americans in the Philippines viewed the locals as racial inferiors, but Taft wrote soon before his arrival, "we propose to banish this idea from their minds". Taft did not impose

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

at official events, and treated the Filipinos as social equals. Nellie Taft recalled that "neither politics nor race should influence our hospitality in any way".

McKinley was

assassinated in September 1901, and was succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt. Taft and Roosevelt had first become friends around 1890 while Taft was Solicitor General and Roosevelt a member of the

United States Civil Service Commission. Taft had, after McKinley's election, urged the appointment of Roosevelt as

Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and watched as Roosevelt became a war hero,

Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor ...

, and

Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

. They met again when Taft went to Washington in January 1902 to recuperate after two operations caused by an infection. There, Taft testified before the

Senate Committee on the Philippines. Taft wanted Filipino farmers to have a stake in the new government through land ownership, but much of the arable land was held by

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

religious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

s of mostly Spanish priests, which were often resented by the Filipinos. Roosevelt had Taft go to Rome to negotiate with

Pope Leo XIII, to purchase the lands and to arrange the withdrawal of the Spanish priests, with Americans replacing them and training locals as clergy. Taft did not succeed in resolving these issues on his visit to Rome, but an agreement on both points was made in 1903.

Secretary of War

In late 1902, Taft had heard from Roosevelt that a seat on the Supreme Court would soon fall vacant on the resignation of Justice

George Shiras, and Roosevelt desired that Taft fill it. Although this was Taft's professional goal, he refused as he felt his work as governor was not yet done. The following year, Roosevelt asked Taft to become

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. As the War Department administered the Philippines, Taft would remain responsible for the islands, and

Elihu Root, the incumbent, was willing to postpone his departure until 1904, allowing Taft time to wrap up his work in Manila. After consulting with his family, Taft agreed, and sailed for the United States in December 1903.

When Taft took office as

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

in January 1904, he was not called upon to spend much time administering the army, which the president was content to do himself—Roosevelt wanted Taft as a

troubleshooter in difficult situations, as a legal adviser, and to be able to give campaign speeches as he sought election in his own right. Taft strongly defended Roosevelt's record in his addresses, and wrote of the president's successful but strenuous efforts to gain election, "I would not run for president if you guaranteed the office. It is awful to be afraid of one's shadow."

Between 1905 and 1907, Taft came to terms with the likelihood he would be the next Republican nominee for president, though he did not plan to actively campaign for it. When Justice

Henry Billings Brown resigned in 1906, Taft would not accept the seat although Roosevelt offered it, a position Taft held to when another seat opened in 1906.

Edith Roosevelt, the

First Lady, disliked the growing closeness between the two men, feeling that they were too much alike and that the president did not gain much from the advice of someone who rarely contradicted him.

Alternatively, Taft wanted to be chief justice, and kept a close eye on the health of the aging incumbent,

Melville Fuller, who turned 75 in 1908. Taft believed Fuller likely to live many years. Roosevelt had indicated he was likely to appoint Taft if the opportunity came to fill the court's center seat, but some considered Attorney General

Philander Knox a better candidate. In any event, Fuller remained chief justice throughout Roosevelt's presidency.

Through the 1903

separation of Panama from Colombia and the

Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, the United States had secured rights to build

a canal in the

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

. Legislation authorizing construction did not specify which government department would be responsible, and Roosevelt designated the Department of War. Taft journeyed to Panama in 1904, viewing the canal site and meeting with Panamanian officials. The

Isthmian Canal Commission had trouble keeping a chief engineer, and when in February 1907

John F. Stevens submitted his resignation, Taft recommended an army engineer,

George W. Goethals. Under Goethals, the project moved ahead smoothly.

Another colony lost by Spain in 1898 was Cuba, but as freedom for Cuba had been a major purpose of the war, it was not annexed by the U.S., but was, after a period of occupation, given independence in 1902. Election fraud and corruption followed, as did factional conflict. In September 1906, President

Tomás Estrada Palma asked for U.S. intervention. Taft traveled to Cuba with a small American force, and on September 29, 1906, under the terms of the

Cuban–American Treaty of Relations of 1903, declared himself Provisional Governor of Cuba, a post he held for two weeks before being succeeded by

Charles Edward Magoon. In his time in Cuba, Taft worked to persuade Cubans that the U.S. intended stability, not occupation.

Taft remained involved in Philippine affairs. During Roosevelt's election campaign in 1904, he urged that Philippine agricultural products be admitted to the U.S. without duty. This caused growers of U.S. sugar and tobacco to complain to Roosevelt, who remonstrated with his Secretary of War. Taft expressed unwillingness to change his position, and threatened to resign; Roosevelt hastily dropped the matter. Taft returned to the islands in 1905, leading a delegation of congressmen, and again in 1907, to open the first

Philippine Assembly.

On both of his Philippine trips as

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, Taft went to Japan, and met with officials there. The meeting in July 1905 came a month before the

Portsmouth Peace Conference, which would end the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

with the

Treaty of Portsmouth. Taft met with Japanese Prime Minister

Katsura Tarō. After that meeting, the two signed

a memorandum. It contained nothing new but instead reaffirmed official positions: Japan had no intention to invade the Philippines, and the U.S. that it did not object to

Japanese control of Korea. There were U.S. concerns about the number of Japanese laborers coming to the American West Coast, and during Taft's second visit, in September 1907,

Tadasu Hayashi, the foreign minister, informally

agreed to issue fewer passports to them.

Presidential election of 1908

Gaining the nomination

Roosevelt had served almost three and a half years of McKinley's term. On the night of his own election in 1904, Roosevelt publicly declared that he would not run for reelection

in 1908, a pledge he quickly regretted. But he felt bound by his word. Roosevelt believed Taft was his logical successor, although the War Secretary had initially been reluctant to run. Roosevelt used his control of the party machinery to aid his heir apparent. On pain of the loss of their jobs, political appointees were required to support Taft or remain silent.

A number of Republican politicians, such as

Treasury Secretary George Cortelyou, tested the waters for a run but chose to stay out. New York Governor

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

ran, but when he made a major policy speech, Roosevelt the same day sent a special message to Congress warning in strong terms against

corporate corruption. The resulting coverage of the presidential message relegated Hughes to the back pages. Roosevelt reluctantly deterred repeated attempts to draft him for another term.

Assistant

Postmaster General Frank H. Hitchcock resigned from his office in February 1908 to lead the Taft effort. In April, Taft made a speaking tour, traveling as far west as

Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

before being recalled to straighten out a contested election in

Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

. He had no serious opposition at the

1908 Republican National Convention in Chicago in June, and gained a first-ballot victory. Yet Taft did not have things his own way: he had hoped his running mate would be a midwestern progressive like Iowa Senator

Jonathan Dolliver, but instead the convention named Congressman

James S. Sherman

James Schoolcraft Sherman (October 24, 1855 – October 30, 1912) was the 27th vice president of the United States, serving from 1909 until his death in 1912, under President William Howard Taft. A member of the Republican Party (United States), ...

of New York, a conservative. Taft resigned as Secretary of War on June 30 to devote himself full-time to the campaign.

General election campaign

Taft's opponent in the general election was

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

, the Democratic nominee for the third time in four presidential elections. As many of Roosevelt's reforms stemmed from proposals by Bryan, the Democrat argued that he was the true heir to Roosevelt's mantle. Corporate contributions to federal political campaigns had been outlawed by the 1907

Tillman Act, and Bryan proposed that contributions by officers and directors of corporations be similarly banned, or at least disclosed when made. Taft was only willing to see the contributions disclosed after the election, and tried to ensure that officers and directors of corporations litigating with the government were not among his contributors.

Taft began the campaign on the wrong foot, fueling the arguments of those who said he was not his own man by traveling to Roosevelt's home at

Sagamore Hill for advice on his acceptance speech, saying that he needed "the President's judgment and criticism". Taft supported most of Roosevelt's policies. He argued that labor had a right to organize, but not boycott, and that corporations and the wealthy must also obey the law. Bryan wanted the railroads to be owned by the government, but Taft preferred that they remain in the private sector, with their maximum rates set by the

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later Trucking industry in the United States, truc ...

, subject to

judicial review

Judicial review is a process under which a government's executive, legislative, or administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. In a judicial review, a court may invalidate laws, acts, or governmental actions that are in ...

. Taft attributed blame for the recent recession, the

Panic of 1907, to stock speculation and other abuses, and felt some reform of the currency (the U.S. was on the

gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

) was needed to allow flexibility in the government's response to poor economic times, that specific legislation on

trusts was needed to supplement the

Sherman Antitrust Act, and that

the constitution should be amended to allow for an income tax, thus overruling decisions of the Supreme Court striking such a tax down. Roosevelt's expansive use of executive power had been controversial; Taft proposed to continue his policies, but place them on more solid legal underpinnings through the passage of legislation.

Taft upset some progressives by choosing

Frank Harris Hitchcock as chairman of the

Republican National Committee (RNC), placing him in charge of the presidential campaign. Hitchcock was quick to bring in men closely allied with big business. Taft took an August vacation in

Hot Springs, Virginia, where he irritated political advisors by spending more time on golf than strategy. After seeing a newspaper photo of Taft taking a large swing at a golf ball, Roosevelt warned him against candid shots.

Roosevelt, frustrated by his own relative inaction, showered Taft with advice, fearing that the electorate would not appreciate Taft's qualities, and that Bryan would win. Roosevelt's supporters spread rumors that the president was in effect running Taft's campaign. This annoyed Nellie Taft, who never trusted the Roosevelts. Nevertheless, Roosevelt supported the Republican nominee with such enthusiasm that humorists suggested "TAFT" stood for "Take advice from Theodore".

Bryan urged a system of bank guarantees, so that depositors could be repaid if banks failed, but Taft opposed this, offering a

postal savings system instead. The issue of prohibition of alcohol entered the campaign when in mid-September,

Carrie Nation called on Taft and demanded to know his views. Taft and Roosevelt had agreed the party platform would take no position on the matter, and Nation left indignant, to allege that Taft was irreligious and against temperance. Taft, at Roosevelt's advice, ignored the issue.

In the end, Taft won by a comfortable margin. Taft defeated Bryan by 321 electoral votes to 162; however, he garnered just 51.6 percent of the popular vote. Nellie Taft said regarding the campaign, "There was nothing to criticize, except his not knowing or caring about the way the game of politics is played." Longtime White House usher

Ike Hoover recalled that Taft came often to see Roosevelt during the campaign, but seldom between the election and Inauguration Day, March 4, 1909.

On February 18, 1909, after his election but before his inauguration, Taft was recognized as a

Mason at sight at the Scottish Rite Cathedral in Cincinnati.

Presidency (1909–1913)

Inauguration and appointments

Taft was

sworn in as president on March 4, 1909. Due to a winter storm that coated Washington with ice, Taft was inaugurated within the Senate Chamber rather than outside the Capitol as is customary. The new president stated in his inaugural address that he had been honored to have been "one of the advisers of my distinguished predecessor" and to have had a part "in the reforms he has initiated. I should be untrue to myself, to my promises, and to the declarations of the party platform on which I was elected if I did not make the maintenance and enforcement of those reforms a most important feature of my administration". He pledged to make those reforms long-lasting, ensuring that honest businessmen did not suffer uncertainty through change of policy. He spoke of the need to reduce the 1897 Dingley tariff, of the need for antitrust reform, and for continued advancement of the Philippines toward full self-government. Roosevelt left office with regret that his tenure in the position he enjoyed so much was over and, to keep out of Taft's way, arranged for a year-long hunting trip to Africa.

Soon after the Republican convention, Taft and Roosevelt had discussed which cabinet officers would stay on. Taft kept only

Agriculture Secretary James Wilson and Postmaster General

George von Lengerke Meyer (who was transferred to the Navy Department). Others appointed to the Taft cabinet included

Philander Knox, who had served under McKinley and Roosevelt as Attorney General, as the new Secretary of State, and

Franklin MacVeagh as

Treasury Secretary.

Taft did not enjoy the easy relationship with the press that Roosevelt had, choosing not to offer himself for interviews or photo opportunities as often as his predecessor had.

His administration marked a change in style from the charismatic leadership of Roosevelt to Taft's quieter passion for the rule of law.

First Lady's illness

Early in Taft's term, in May 1909, his wife Nellie had a severe

stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

that left her paralysed in one arm and one leg and deprived her of the power of speech. Taft spent several hours each day looking after her and teaching her to speak again, which took a year.

Foreign policy

Organization and principles

Taft made it a priority to restructure the

State Department, noting, "it is organized on the basis of the needs of the government in 1800 instead of 1900." The department was for the first time organized into geographical divisions, including desks for the Far East, Latin America and Western Europe. The department's first in-service training program was established, and appointees spent a month in Washington before going to their posts. Taft and Secretary of State Knox had a strong relationship, and the president listened to his counsel on matters foreign and domestic. According to historian Paolo E. Coletta, Knox was not a good diplomat, and had poor relations with the Senate, press, and many foreign leaders, especially those from Latin America.

There was broad agreement between Taft and Knox on major foreign policy goals; the U.S. would not interfere in European affairs, and would use force if necessary to enforce the

Monroe Doctrine in the Americas. The defense of the Panama Canal, which was under construction throughout Taft's term (it opened in 1914), guided

United States foreign policy in the Caribbean and Central America. Previous administrations had made efforts to promote American business interests overseas, but Taft went a step further and used the web of American diplomats and consuls abroad to further trade. Such ties, Taft hoped, would promote world peace. Taft pushed for arbitration treaties with Great Britain and France, but the Senate was not willing to yield to arbitrators its constitutional prerogative to approve treaties.

Tariffs and reciprocity

At the time of Taft's presidency,

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations ...

through the use of tariffs was a fundamental position of the Republican Party. The

Dingley Act tariff had been enacted to protect American industry from foreign competition. The 1908 party platform had supported unspecified revisions to the Dingley Act, and Taft interpreted this to mean reduction. Taft called a special session of Congress to convene on March 15, 1909, to deal with the tariff question.

Sereno E. Payne, chairman of the

House Ways and Means Committee, had held hearings in late 1908, and sponsored the resulting draft legislation. On balance, the bill reduced tariffs slightly, but when it passed the House in April 1909 and reached the Senate, the chairman of the

Senate Finance Committee, Rhode Island Senator

Nelson W. Aldrich, attached many amendments raising rates. This outraged progressives such as Wisconsin's

Robert M. La Follette, who urged Taft to say that the bill was not in accord with the party platform. Taft refused, angering them. Taft insisted that most imports from the Philippines be free of duty, and according to Anderson, showed effective leadership on a subject he was knowledgeable on and cared about.

When opponents sought to modify the tariff bill to allow for an income tax, Taft opposed it on the ground that the Supreme Court would likely strike it down as unconstitutional, as it had before. Instead, they proposed a constitutional amendment, which passed both houses in early July, was sent to the states, and by 1913 was ratified as the

Sixteenth Amendment. In the

conference committee, Taft won some victories, such as limiting the tax on lumber. The conference report passed both houses, and Taft signed it on August 6, 1909. The

Payne-Aldrich tariff was immediately controversial. According to Coletta, "Taft had lost the initiative, and the wounds inflicted in the acrid tariff debate never healed".

In Taft's

annual message sent to Congress in December 1910, he urged a

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

accord with Canada. Britain at that time still handled Canada's foreign relations, and Taft found the British and Canadian governments willing. Many in Canada opposed an accord, fearing the U.S. would dump it when it became inconvenient, as it had the 1854

Elgin-Marcy Treaty in 1866, and farm and fisheries interests in the United States were also opposed. After talks with Canadian officials in January 1911, Taft had the agreement, which was not a treaty, introduced into Congress. It passed in late July. The

Parliament of Canada

The Parliament of Canada () is the Canadian federalism, federal legislature of Canada. The Monarchy of Canada, Crown, along with two chambers: the Senate of Canada, Senate and the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons, form the Bicameral ...

led by Prime Minister Sir

Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier (November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and Liberal politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadians, French ...

had deadlocked over the issue. Canadians turned Laurier out of office in the

September 1911 election and

Robert Borden became the new prime minister. No cross-border agreement was concluded, and the debate deepened divisions within the Republican Party.

Latin America

Taft and his Secretary of State, Philander Knox, instituted a policy of

Dollar Diplomacy toward Latin America, believing U.S. investment would benefit all involved, while diminishing European influence in regions where the

Monroe Doctrine applied. The policy was unpopular among Latin American states that did not wish to become financial protectorates of the United States, as well as in the U.S. Senate, many of whose members believed the U.S. should not interfere abroad. No foreign affairs controversy tested Taft's policy more than the collapse of the Mexican regime and subsequent turmoil of the

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

.

When Taft entered office, Mexico was increasingly restless under the grip of longtime dictator

Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori (; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915) was a General (Mexico), Mexican general and politician who was the dictator of Mexico from 1876 until Mexican Revolution, his overthrow in 1911 seizing power in a Plan ...

. Many Mexicans backed his opponent,

Francisco Madero. There were a number of incidents in which Mexican rebels crossed the U.S. border to obtain horses and weapons; Taft sought to prevent this by ordering the

US Army to the border areas for maneuvers. Taft told his military aide,

Archibald Butt, that "I am going to sit on the lid and it will take a great deal to pry me off". He showed his support for Díaz by meeting with him at

El Paso, Texas

El Paso (; ; or ) is a city in and the county seat of El Paso County, Texas, United States. The 2020 United States census, 2020 population of the city from the United States Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the List of ...

, and

Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, the first meeting between a U.S. and a Mexican president and also the first time an American president visited Mexico. The day of the summit,

Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

and a

Texas Ranger captured and disarmed an assassin holding a

palm pistol only a few feet from the two presidents. Before the election in Mexico, Díaz jailed opposition candidate

Francisco I. Madero, whose supporters took up arms. This resulted in both the ousting of Díaz and

a revolution that would continue for another ten years. In the U.S.'s

Arizona Territory, two citizens were killed and almost a dozen injured, some as a result of gunfire across the border. Taft was against an aggressive response and so instructed the territorial governor.

Nicaragua's president,

José Santos Zelaya, wanted to revoke commercial concessions granted to American companies, and American diplomats quietly favored rebel forces under

Juan Estrada. Nicaragua was in debt to foreign powers, and the U.S. was unwilling to let an alternate canal route fall into the hands of Europeans. Zelaya's elected successor,

José Madriz, could not put down the rebellion as U.S. forces interfered, and in August 1910, the Estrada forces took

Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

, the capital. The U.S. compelled Nicaragua to accept a loan, and sent officials to ensure it was repaid from government revenues. The country remained unstable, and after another coup in 1911 and more disturbances in 1912, Taft sent troops to begin the

United States occupation of Nicaragua, which lasted until 1933.

Treaties among Panama, Colombia, and the United States to resolve disputes arising from the Panamanian Revolution of 1903 had been signed by the lame-duck Roosevelt administration in early 1909, and were approved by the Senate and also ratified by Panama. Colombia, however, declined to ratify the treaties, and after the 1912 elections, Knox offered $10 million to the Colombians (later raised to $25 million). The Colombians felt the amount inadequate, and requested arbitration; the matter was not settled under the Taft administration.

East Asia

Due to his years in the Philippines, Taft was keenly interested as president in East Asian affairs. Taft considered relations with Europe relatively unimportant, but because of the potential for trade and investment, Taft ranked the post of minister to China as most important in the Foreign Service. Knox did not agree, and declined a suggestion that he go to

Peking to view the facts on the ground. Taft considered Roosevelt's minister there,

William W. Rockhill, as uninterested in the China trade, and replaced him with

William J. Calhoun, whom McKinley and Roosevelt had sent on several foreign missions. Knox did not listen to Calhoun on policy, and there were often conflicts. Taft and Knox tried unsuccessfully to extend John Hay's

Open Door Policy to

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

.

In 1898, an American company had gained a concession for a railroad between

Hakou and

Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

, but the Chinese revoked the agreement in 1904 after the company (which was indemnified for the revocation) breached the agreement by selling a majority stake outside the United States. The Chinese imperial government got the money for the indemnity from the British Hong Kong government, on condition British subjects would be favored if foreign capital was needed to build the railroad line, and in 1909, a British-led consortium began negotiations. This came to Knox's attention in May of that year, and he demanded that U.S. banks be allowed to participate. Taft appealed personally to the Prince Regent,

Zaifeng, Prince Chun, and was successful in gaining U.S. participation, though agreements were not signed until May 1911. However, the Chinese decree authorizing the agreement also required the nationalization of local railroad companies in the affected provinces. Inadequate compensation was paid to the shareholders, and these grievances were among those which touched off the

Chinese Revolution of 1911.

After the revolution broke out, the revolt's leaders chose

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

as provisional president of what became the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, overthrowing the

Manchu dynasty, Taft was reluctant to recognize the new government, although American public opinion was in favor of it. The U.S. House of Representatives in February 1912 passed a resolution supporting a Chinese republic, but Taft and Knox felt recognition should come as a concerted action by Western powers. Taft in his final

annual message to Congress in December 1912 indicated that he was moving toward recognition once the republic was fully established, but by then he had been defeated for reelection and he did not follow through.

Taft continued the policy against immigration from China and Japan as under Roosevelt. A revised treaty of friendship and navigation entered into by the U.S. and Japan in 1911 granted broad reciprocal rights to Japanese people in America and Americans in Japan, but were premised on the continuation of the Gentlemen's Agreement. There was objection on the West Coast when the treaty was submitted to the Senate, but Taft informed politicians that there was no change in immigration policy.

Europe

Taft was opposed to the traditional practice of rewarding wealthy supporters with key ambassadorial posts, preferring that diplomats not live in a lavish lifestyle and selecting men who, as Taft put it, would recognize an American when they saw one. High on his list for dismissal was the ambassador to France,

Henry White, whom Taft knew and disliked from his visits to Europe. White's ousting caused other career State Department employees to fear that their jobs might be lost to politics. Taft also wanted to replace the Roosevelt-appointed ambassador in London,

Whitelaw Reid, but Reid, owner of the ''

New-York Tribune'', had backed Taft during the campaign, and both William and Nellie Taft enjoyed his gossipy reports. Reid remained in place until his 1912 death.

Taft was a supporter of settling international disputes by arbitration, and he negotiated treaties with Great Britain and with France providing that differences be arbitrated. These were signed in August 1911. Neither Taft nor Knox (a former senator) consulted with members of the Senate during the negotiating process. By then many Republicans were opposed to Taft and the president felt that lobbying too hard for the treaties might cause their defeat. He made some speeches supporting the treaties in October, but the Senate added amendments Taft could not accept, killing the agreements.

Although no general arbitration treaty was entered into, Taft's administration settled several disputes with Great Britain by peaceful means, often involving arbitration. These included a settlement of the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick, a long-running dispute over seal hunting in the

Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

that also involved Japan, and a similar disagreement regarding fishing off Newfoundland. The sealing convention remained in force until abrogated by Japan in 1940.

Domestic policies and politics

Antitrust

Taft continued and expanded Roosevelt's efforts to break up business combinations through lawsuits brought under the

Sherman Antitrust Act, bringing 70 cases in four years (Roosevelt had brought 40 in seven years). Suits brought against the

Standard Oil Company and the

American Tobacco Company, initiated under Roosevelt, were decided in favor of the government by the Supreme Court in 1911. In June 1911, the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives began hearings into

United States Steel (U.S. Steel). That company had been expanded under Roosevelt, who had supported its acquisition of the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company as a means of preventing the deepening of the

Panic of 1907, a decision the former president defended when testifying at the hearings. Taft, as Secretary of War, had praised the acquisitions. Historian Louis L. Gould suggested that Roosevelt was likely deceived into believing that U.S. Steel did not want to purchase the Tennessee company, but it was in fact a bargain. For Roosevelt, questioning the matter went to his personal honesty.

In October 1911, Taft's Justice Department brought suit against U.S. Steel, demanding that over a hundred of its subsidiaries be granted corporate independence, and naming as defendants many prominent business executives and financiers. The pleadings in the case had not been reviewed by Taft, and alleged that Roosevelt "had fostered monopoly, and had been duped by clever industrialists". Roosevelt was offended by the references to him and his administration in the pleadings, and felt that Taft could not evade command responsibility by saying he did not know of them.

Taft sent a special message to Congress on the need for a revamped antitrust statute when it convened its regular session in December 1911, but it took no action. Another antitrust case that had political repercussions for Taft was that brought against the

International Harvester Company, the large manufacturer of farm equipment, in early 1912. As Roosevelt's administration had investigated International Harvester, but had taken no action (a decision Taft had supported), the suit became caught up in Roosevelt's challenge for the Republican presidential nomination. Supporters of Taft alleged that Roosevelt had acted improperly; the former president blasted Taft for waiting three and a half years, and until he was under challenge, to reverse a decision he had supported.

Ballinger–Pinchot affair

Roosevelt was an ardent conservationist, assisted in this by like-minded appointees, including Interior Secretary

James R. Garfield and Chief Forester

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsyl ...

. Taft agreed with the need for conservation, but felt it should be accomplished by legislation rather than executive order. He did not retain Garfield, an Ohioan, as secretary, choosing instead a westerner, former Seattle mayor

Richard A. Ballinger. Roosevelt was surprised at the replacement, believing that Taft had promised to keep Garfield, and this change was one of the events that caused Roosevelt to realize that Taft would choose different policies.

Roosevelt had withdrawn much land from the public domain, including some in Alaska thought rich in coal. In 1902, Clarence Cunningham, an Idaho entrepreneur, had found coal deposits in Alaska, and made mining claims, and the government investigated their legality. This dragged on for the remainder of the Roosevelt administration, including during the year (1907–1908) when Ballinger served as head of the

United States General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States government responsible for Public domain (land), public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 ...

. A special agent for the Land Office,

Louis Glavis, investigated the Cunningham claims, and when Secretary Ballinger in 1909 approved them, Glavis broke governmental protocol by going outside the Interior Department to seek help from Pinchot.

In September 1909, Glavis made his allegations public in a magazine article, disclosing that Ballinger had acted as an attorney for Cunningham between his two periods of government service. This violated conflict of interest rules forbidding a former government official from advocacy on a matter he had been responsible for. On September 13, 1909, Taft dismissed Glavis from government service, relying on a report from Attorney General

George W. Wickersham dated two days previously. Pinchot was determined to dramatize the issue by forcing his own dismissal, which Taft tried to avoid, fearing that it might cause a break with Roosevelt (still overseas). Taft asked

Elihu Root (by then a senator) to look into the matter, and Root urged the firing of Pinchot.

Taft had ordered government officials not to comment on the fracas. In January 1910, Pinchot forced the issue by sending a letter to Iowa Senator Dolliver alleging that but for the actions of the Forestry Service, Taft would have approved a fraudulent claim on public lands. According to Pringle, this "was an utterly improper appeal from an executive subordinate to the legislative branch of the government and an unhappy president prepared to separate Pinchot from public office". Pinchot was dismissed, much to his delight, and he sailed for Europe to lay his case before Roosevelt. A congressional investigation followed, which cleared Ballinger by majority vote, but the administration was embarrassed when Glavis' attorney,

Louis D. Brandeis, proved that the Wickersham report had been backdated, which Taft belatedly admitted. The Ballinger–Pinchot affair caused progressives and Roosevelt loyalists to feel that Taft had turned his back on Roosevelt's agenda.

Civil rights

Taft announced in his inaugural address that he would not appoint African Americans to federal jobs, such as postmaster, where this would cause racial friction. This differed from Roosevelt, who would not remove or replace black officeholders with whom local whites would not deal. Termed Taft's "Southern Policy", this stance effectively invited white protests against black appointees. Taft followed through, removing most black office holders in the South, and made few appointments of African Americans in the North.

At the time Taft was inaugurated, the way forward for African Americans was debated by their leaders.

Booker T. Washington felt that most blacks should be trained for industrial work, with only a few seeking higher education;

W. E. B. DuBois took a more militant stand for equality. Taft tended toward Washington's approach. According to Coletta, Taft let the African-American "be 'kept in his place' ... He thus failed to see or follow the humanitarian mission historically associated with the Republican party, with the result that Negroes both North and South began to drift toward the Democratic party."

Taft, a

Unitarian, was a leader in the early 20th century of the favorable reappraisal of Catholicism's historic role. It tended to neutralize anti-Catholic sentiments, especially in the Far West where Protestantism was a weak force. In 1904 Taft gave a speech at the

University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac (known simply as Notre Dame; ; ND) is a Private university, private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, United States. Founded in 1842 by members of the Congregation of Holy Cross, a Cathol ...

. He praised the "enterprise, courage, and fidelity to duty that distinguished those heroes of Spain who braved the then frightful dangers of the deep to carry Christianity and European civilization into" the Philippines. In 1909 he praised

Junípero Serra as an "apostle, legislator,

ndbuilder" who advanced "the beginning of civilization in California."

A supporter of free immigration, Taft vetoed a bill passed by Congress and supported by labor unions that would have restricted unskilled laborers by imposing a literacy test.

Judicial appointments

Taft made six appointments to the Supreme Court; only

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

and

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

made more. The death of Justice

Rufus Peckham in October 1909 gave Taft his first opportunity. He chose an old friend and colleague from the Sixth Circuit,

Horace H. Lurton of Georgia; he had in vain urged Theodore Roosevelt to appoint Lurton to the high court. Attorney General Wickersham objected that Lurton, a former Confederate soldier and a Democrat, was aged 65. Taft named Lurton anyway on December 13, 1909, and the Senate confirmed him by voice vote a week later. Lurton is still the oldest person to be made an associate justice. Lurie suggested that Taft, already beset by the tariff and conservation controversies, desired to perform an official act which gave him pleasure, especially since he thought Lurton deserved it.

Justice

David Josiah Brewer's death on March 28, 1910, gave Taft a second opportunity to fill a seat on the high court; he chose New York Governor

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. Taft told Hughes that should the chief justiceship fall vacant during his term, Hughes would be his likely choice for the center seat. The Senate quickly confirmed Hughes, but then Chief Justice Fuller died on July 4, 1910. Taft took five months to replace Fuller, and when he did, it was with Justice

Edward Douglass White, who became the first associate justice to be promoted to chief justice. According to Lurie, Taft, who still had hopes of being chief justice, may have been more willing to appoint an older man than he (White) than a younger one (Hughes), who might outlive him, as indeed Hughes did. To fill White's seat as associate justice, Taft appointed

Willis Van Devanter of Wyoming, a federal appeals judge. By the time Taft nominated White and Van Devanter in December 1910, he had another seat to fill due to

William Henry Moody's retirement because of illness; he named a Louisiana Democrat,

Joseph R. Lamar, whom he had met while playing golf, and had subsequently learned had a good reputation as a judge.

With the death of Justice Harlan in October 1911, Taft got to fill a sixth seat on the Supreme Court. After Secretary Knox declined appointment, Taft named

Chancellor of New Jersey Mahlon Pitney, the last person appointed to the Supreme Court who did not attend law school. Pitney had a stronger anti-labor record than Taft's other appointments, and was the only one to meet opposition, winning confirmation by a Senate vote of 50–26.

Taft appointed 13 judges to the federal courts of appeal and 38 to the

United States district courts. He also appointed judges to various specialized courts, including the first five appointees each to the

United States Commerce Court and the

United States Court of Customs Appeals. The Commerce Court, created in 1910, stemmed from a Taft proposal for a specialized court to hear appeals from the Interstate Commerce Commission. There was considerable opposition to its establishment, which grew only when one of its judges,

Robert W. Archbald, was in 1912

impeached for corruption and removed by the Senate the following January. Taft vetoed a bill to abolish the court, but the respite was short-lived as

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

signed similar legislation in October 1913.

1912 presidential campaign and election

Moving apart from Roosevelt

During Roosevelt's fifteen months beyond the Atlantic, from March 1909 to June 1910, neither man wrote much to the other. Taft biographer Lurie suggested that each expected the other to make the first move to re-establish their relationship on a new footing. Upon Roosevelt's triumphant return, Taft invited him to stay at the White House. The former president declined, and in private letters to friends expressed dissatisfaction at Taft's performance. Taft and Roosevelt met twice in 1910; the meetings, though outwardly cordial, did not display their former closeness. Nevertheless, he wrote that he expected Taft to be renominated by the Republicans in 1912, and did not speak of himself as a candidate.

Roosevelt gave a series of speeches in the West in the late summer and early fall of 1910 in which he severely criticized the nation's judiciary. He not only attacked the

Supreme Court's 1905 decision ''

Lochner v. New York'', he accused the federal courts of undermining democracy, branding the suspect jurists "fossilized judges", and comparing their tendency to strike down progressive reform legislation to Justice

Roger Taney's ruling in ''

Dred Scott v. Sandford'' (1857). To ensure that the constitution served the public interest, Roosevelt joined other progressives, including the Democrat

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

, in calling for "judicial recall", which would theoretically enable popular majorities to remove judges from office by referendum and, in some cases, reverse unpopular judicial decisions. This attack horrified Taft, who, though he privately agreed that ''Lochner'' and other decisions had been poorly decided, adamantly believed in the importance of judicial authority to constitutional government. His personal horror was shared by other prominent members of the nation's elite legal community, like

Elihu Root and

Alton B. Parker, and solidified in Taft's mind that Roosevelt must not be permitted to regain the presidency, whatever the cost.

In addition to the judicial issue, Roosevelt called for "elimination of corporate expenditures for political purposes, physical valuation of railroad properties, regulation of industrial combinations, establishment of an export tariff commission, a graduated income tax", and "workmen's compensation laws, state and national legislation to regulate the

aborof women and children, and complete publicity of campaign expenditure". According to John Murphy, "As Roosevelt began to move to the left, Taft veered to the right."

During the 1910 midterm election campaign, Roosevelt involved himself in New York politics. With donations and influence, Taft meanwhile tried to secure the election of Ohio's Republican gubernatorial nominee, former lieutenant governor

Warren G. Harding. The Republicans suffered losses in the 1910 elections as the Democrats took control of the House and slashed the Republican majority in the Senate. In New Jersey, Democrat

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

was elected governor, and Harding lost in Ohio.

After the election, Roosevelt continued to promote progressive ideals, a

New Nationalism, much to Taft's dismay. Roosevelt attacked his successor's administration, arguing that its guiding principles were not those of the party of

Lincoln, but those of the

Gilded Age. The feud continued on and off through 1911, a year in which there were few elections of significance. Senator

Robert La Follette announced a presidential run as a Republican, and was backed by a convention of progressives. Roosevelt began to move into a position for a run in late 1911, writing that the tradition that presidents not run for a third term applied only to consecutive terms.

Roosevelt received many letters from supporters urging him to run, and Republican office-holders were organizing on his behalf. Thwarted on many policies by an unwilling Congress and courts in his full term in the White House, he saw manifestations of public support he believed would sweep him to the White House with a mandate for progressive policies that would brook no opposition. In February, Roosevelt announced he would accept the Republican nomination if it was offered to him. Taft felt that if he lost in November, it would be a repudiation of the party, but if he lost renomination, it would be a rejection of himself. He was reluctant to oppose Roosevelt, who helped make him president, but having become president, he was determined to be president, and that meant not standing aside to allow Roosevelt to gain another term.

Primaries and convention

As Roosevelt became more radical in his progressivism, Taft was hardened in his resolve to achieve re-nomination, as he was convinced that the progressives threatened the very foundation of the government. One blow to Taft was the loss of

Archibald Butt, one of the last links between the previous and present presidents, as Butt had formerly served Roosevelt. Ambivalent between his loyalties, Butt went to Europe on vacation; he died in the

sinking of the RMS ''Titanic''.

Roosevelt dominated the primaries, winning 278 of the 362 delegates to

the Republican National Convention in Chicago decided in that manner. Taft had control of the party machinery, and it came as no surprise that he gained the bulk of the delegates decided at district or state conventions. Taft did not have a majority, but was likely to have one once southern delegations committed to him. Roosevelt challenged the election of these delegates, but the RNC overruled most objections. Roosevelt's sole remaining chance was with a friendly convention chairman, who might make rulings on the seating of delegates that favored his side. Taft followed custom and remained in Washington, but Roosevelt went to Chicago to run his campaign and told his supporters in a speech, "we stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord".