Wildlife of Antarctica on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The wildlife of Antarctica are

The wildlife of Antarctica are

Around 98% of continental Antarctica is covered in ice up to thick. Antarctica's icy deserts have extremely low temperatures, high solar radiation, and extreme dryness. Any precipitation that does fall usually falls as snow, and is restricted to a band around from the coast. Some areas receive as little as of precipitation annually. The coldest temperature recorded on Earth was at Vostok Station on the

Around 98% of continental Antarctica is covered in ice up to thick. Antarctica's icy deserts have extremely low temperatures, high solar radiation, and extreme dryness. Any precipitation that does fall usually falls as snow, and is restricted to a band around from the coast. Some areas receive as little as of precipitation annually. The coldest temperature recorded on Earth was at Vostok Station on the

The rocky shores of mainland Antarctica and its offshore islands provide nesting space for over 100 million birds every spring. These nesters include species of

The rocky shores of mainland Antarctica and its offshore islands provide nesting space for over 100 million birds every spring. These nesters include species of

Cod icefish (Nototheniidae), as well as several other families, are part of the

Cod icefish (Nototheniidae), as well as several other families, are part of the

Six

Six

Most terrestrial

Most terrestrial

Many aquatic

Many aquatic

The red Antarctic sea urchin (''Sterechinus neumayeri'') has been used in several studies and has become a

The red Antarctic sea urchin (''Sterechinus neumayeri'') has been used in several studies and has become a

The greatest

The greatest  The

The

Human activity poses significant risk for Antarctic wildlife, causing problems such as pollution, habitat destruction, and wildlife disturbance. These problems are especially acute around research stations.

Human activity poses significant risk for Antarctic wildlife, causing problems such as pollution, habitat destruction, and wildlife disturbance. These problems are especially acute around research stations.

The wildlife of Antarctica are

The wildlife of Antarctica are extremophiles

An extremophile () is an organism that is able to live (or in some cases thrive) in extreme environments, i.e., environments with conditions approaching or stretching the limits of what known life can adapt to, such as extreme temperature, pres ...

, having adapted to the dryness, low temperatures, and high exposure common in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

. The extreme weather of the interior contrasts to the relatively mild conditions on the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

and the subantarctic islands, which have warmer temperatures and more liquid water. Much of the ocean around the mainland is covered by sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

. The oceans themselves are a more stable environment for life, both in the water column

The (oceanic) water column is a concept used in oceanography to describe the physical (temperature, salinity, light penetration) and chemical ( pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrient salts) characteristics of seawater at different depths for a defined ...

and on the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

.

There is relatively little diversity in Antarctica compared to much of the rest of the world. Terrestrial life is concentrated in areas near the coast. Flying birds nest on the milder shores of the Peninsula and the subantarctic islands. Eight species of penguins

Penguins are a group of aquatic flightless birds from the family Spheniscidae () of the order Sphenisciformes (). They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. Only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is equatorial, with a sm ...

inhabit Antarctica and its offshore islands. They share these areas with seven pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant families Odobenidae (whose onl ...

species. The Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

around Antarctica is home to 10 cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s, many of them migratory. There are very few terrestrial invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s on the mainland, although the species that do live there have high population densities. High densities of invertebrates also live in the ocean, with Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') is a species of krill found in the Antarctica, Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000� ...

forming dense and widespread swarms during the summer. Benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

animal communities also exist around the continent.

Over 1000 fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

species have been found on and around Antarctica. Larger species are restricted to the subantarctic islands, and the majority of species discovered have been terrestrial. Plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s are similarly restricted mostly to the subantarctic islands, and the western edge of the Peninsula. Some moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

es and lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

s however can be found even in the dry interior. Many algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

are found around Antarctica, especially phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

, which form the basis of many of Antarctica's food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Position in the food web, or trophic level, is used in ecology to broadly classify organisms as autotrophs or he ...

s.

Human activity has caused introduced species

An introduced species, alien species, exotic species, adventive species, immigrant species, foreign species, non-indigenous species, or non-native species is a species living outside its native distributional range, but which has arrived ther ...

to gain a foothold in the area, threatening the native wildlife. A history of overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing Fish stocks, fish stock), resu ...

and hunting

Hunting is the Human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products (fur/hide (sk ...

has left many species with greatly reduced numbers. Pollution, habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss or habitat reduction) occurs when a natural habitat is no longer able to support its native species. The organisms once living there have either moved elsewhere, or are dead, leading to a decrease ...

, and climate change pose great risks to the environment. The Antarctic Treaty System

The Antarctic Treaty and related agreements, collectively known as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), regulate international relations with respect to Antarctica, Earth's only continent without a native human population. It was the first arms ...

is a global treaty designed to preserve Antarctica as a place of research, and measures from this system are used to regulate human activity in Antarctica.

Environmental conditions

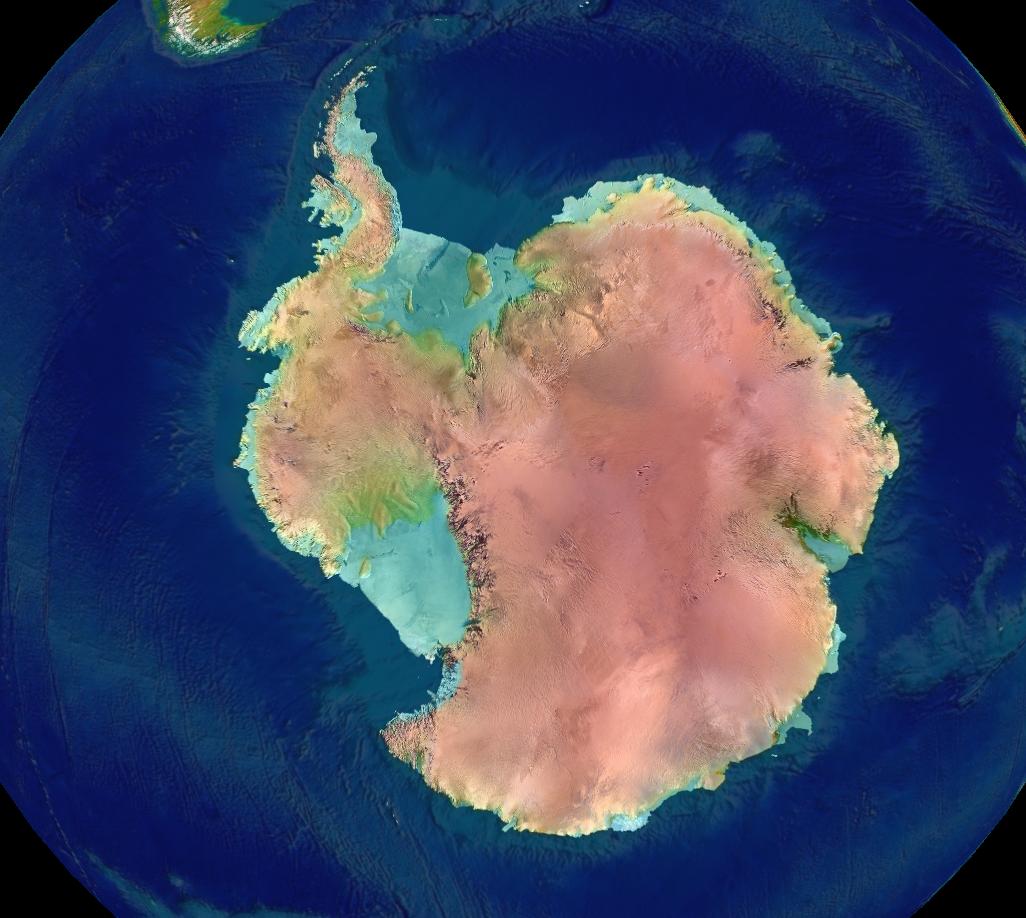

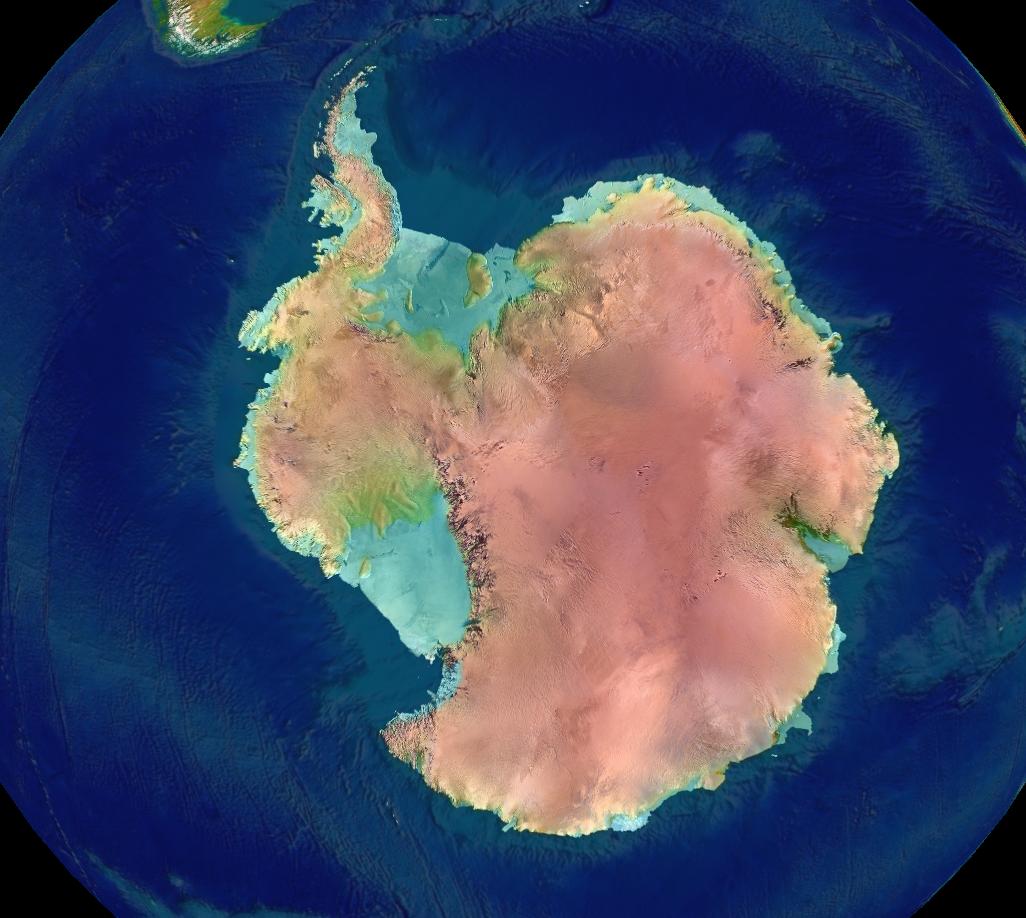

Around 98% of continental Antarctica is covered in ice up to thick. Antarctica's icy deserts have extremely low temperatures, high solar radiation, and extreme dryness. Any precipitation that does fall usually falls as snow, and is restricted to a band around from the coast. Some areas receive as little as of precipitation annually. The coldest temperature recorded on Earth was at Vostok Station on the

Around 98% of continental Antarctica is covered in ice up to thick. Antarctica's icy deserts have extremely low temperatures, high solar radiation, and extreme dryness. Any precipitation that does fall usually falls as snow, and is restricted to a band around from the coast. Some areas receive as little as of precipitation annually. The coldest temperature recorded on Earth was at Vostok Station on the Antarctic Plateau

The Antarctic Plateau, Polar Plateau or King Haakon VII Plateau is a large area of East Antarctica that extends over a diameter of about , and includes the region of the geographic South Pole and the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station. Thi ...

. Organisms that survive in Antarctica are often extremophile

An extremophile () is an organism that is able to live (or in some cases thrive) in extreme environments, i.e., environments with conditions approaching or stretching the limits of what known life can adapt to, such as extreme temperature, press ...

s.

The dry interior of the continent is climatically different from the western Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

and the subantarctic islands. The Peninsula and the islands are far more habitable; some areas of the peninsula can receive of precipitation a year, including rain, and the northern Peninsula is the only area on the mainland where temperatures are expected to go above in summer. The subantarctic islands have a milder temperature and more water, and so are more conducive to life.

The surface temperature of the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

varies very little, ranging from to . During the summer sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

covers of ocean. The continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

surrounding the mainland is wide. The depth of the seafloor in this area ranges from , with an average of . After the shelf, the continental slope descends to abyssal plains

An abyssal plain is an underwater plain on the deep ocean floor, usually found at depths between . Lying generally between the foot of a continental rise and a mid-ocean ridge, abyssal plains cover more than 50% of the Earth's surface. They ...

at deep. In all these areas, 90% of the seafloor is made up of soft sediments, such as sand, mud, and gravel.

Ozone depletion

Ozone depletion consists of two related events observed since the late 1970s: a lowered total amount of ozone in Earth, Earth's upper atmosphere, and a much larger springtime decrease in stratospheric ozone (the ozone layer) around Earth's polar ...

and the presence of a seasonal ozone hole above Antarctica exposes the area to high levels of ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

radiation, although the hole is usually largest when snow and ice is more widespread, reducing overall impact.

Animals

At least 235 marine species are found in both Antarctica and the Arctic, ranging in size from whales and birds to small marine snails, sea cucumbers, and mud-dwelling worms. The large animals often migrate between the two, and smaller animals are expected to be able to spread via underwater currents. However, among smaller marine animals generally assumed to be the same in the Antarctica and the Arctic, more detailed studies of each population have often—but not always—revealed differences, showing that they are closely relatedcryptic species

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

rather than a single bipolar species. Antarctic animals have adapted to reduce heat loss, with mammals developing warm windproof coats and layers of blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of Blood vessel, vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians. It was present in many marine reptiles, such as Ichthyosauria, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

Description ...

.

Antarctica's cold deserts have some of the least diverse fauna in the world. Terrestrial vertebrates are limited to subantarctic islands, and even then they are limited in number. Antarctica, including the subantarctic islands, has no natural fully terrestrial mammals, reptiles, or amphibians. Human activity has however led to the introduction in some areas of foreign species, such as rats, mice, chickens, rabbits, cats, pigs, sheep, cattle, reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

, and various fish. Invertebrates, such as beetle species, have also been introduced.

The benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

communities of the seafloor are diverse and dense, with up to 155,000 animals found in . As the seafloor environment is very similar all around the Antarctic, hundreds of species can be found all the way around the mainland, which is a uniquely wide distribution for such a large community. Polar and deep-sea gigantism

In zoology, deep-sea gigantism or abyssal gigantism is the tendency for species of deep-sea dwelling animals to be larger than their shallower-water relatives across a large taxonomic range. Proposed explanations for this type of gigantism incl ...

, where invertebrates are considerably larger than their warmer-water relatives, is common in this habitat. These two similar types of gigantism are believed to be related to the cold water, which can contain high levels of oxygen, combined with the low metabolic rates ("slow life") of animals living in such cold environments.

Birds

The rocky shores of mainland Antarctica and its offshore islands provide nesting space for over 100 million birds every spring. These nesters include species of

The rocky shores of mainland Antarctica and its offshore islands provide nesting space for over 100 million birds every spring. These nesters include species of albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Paci ...

es, petrel

Petrels are tube-nosed seabirds in the phylogenetic order Procellariiformes.

Description

Petrels are a monophyletic group of marine seabirds, sharing a characteristic of a nostril arrangement that results in the name "tubenoses". Petrels enco ...

s, skua

The skuas are a group of predatory seabirds with seven species forming the genus ''Stercorarius'', the only genus in the family Stercorariidae. The three smaller skuas, the Arctic skua, the long-tailed skua, and the pomarine skua, are called ...

s, gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the subfamily Larinae. They are most closely related to terns and skimmers, distantly related to auks, and even more distantly related to waders. Until the 21st century, most gulls were placed ...

s and tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae, subfamily Sterninae, that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated in eleven genera in a subgroup of the family Laridae, which also ...

s. The insectivorous South Georgia pipit is endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to South Georgia

South Georgia is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean that is part of the British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It lies around east of the Falkland Islands. ...

and some smaller surrounding islands. Ducks, the South Georgia pintail and Eaton's pintail, inhabit South Georgia, Kerguelen and Crozet.

The flightless penguin

Penguins are a group of aquatic flightless birds from the family Spheniscidae () of the order Sphenisciformes (). They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. Only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is equatorial, with a sm ...

s are almost all located in the Southern Hemisphere (the only exception is the equatorial Galapagos penguin), with the greatest concentration located on and around Antarctica. Four of the eighteen penguin species live and breed on the mainland and its close offshore islands. Another four species live on the subantarctic islands. Emperor penguins have four overlapping layers of feathers, keeping them warm. They also reduce heat loss with countercurrent heat exchange systems throughout their body to cool blood as it reaches extremities like the feet. They are the only Antarctic animal to breed during the winter.

Fish

Compared to other major oceans, there are few fish species in fewfamilies

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

in the Southern Ocean. The most species-rich family are the snailfish (Liparidae), followed by the cod icefish (Nototheniidae) and eelpouts (Zoarcidae). Together the snailfish, eelpouts and notothenioids (which includes cod icefish and several other families) account for almost of the more than 320 described fish species in the Southern Ocean. Tens of undescribed species

In taxonomy, an undescribed taxon is a taxon (for example, a species) that has been discovered, but not yet formally described and named. The various Nomenclature Codes specify the requirements for a new taxon to be validly described and named. U ...

also occur in the region, especially among the snailfish. If strictly counting fish species of the Antarctic continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

and upper slope, there are more than 220 species and notothenioids dominate, both in number of species (more than 100) and biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

(more than 90%). Southern Ocean snailfish and eelpouts are generally found in deep waters, while the icefish also are common in shallower waters. In addition to the relatively species-rich families, the region is home to a few species from other families: hagfish

Hagfish, of the Class (biology), class Myxini (also known as Hyperotreti) and Order (biology), order Myxiniformes , are eel-shaped Agnatha, jawless fish (occasionally called slime eels). Hagfish are the only known living Animal, animals that h ...

(Myxinidae), lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are a group of Agnatha, jawless fish comprising the order (biology), order Petromyzontiformes , sole order in the Class (biology), class Petromyzontida. The adult lamprey is characterize ...

(Petromyzontidae), skates (Rajidae), pearlfish (Carapidae), morid cods (Moridae), eel cods (Muraenolepididae), gadid cods (Gadidae), horsefish (Congiopodidae), Antarctic sculpins (Bathylutichthyidae), triplefins (Tripterygiidae) and southern flounders (Achiropsettidae). Among fish found south of the Antarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence or Antarctic Polar Front is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. The line separate ...

, almost 90% of the species are endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to the region.

Icefish

Cod icefish (Nototheniidae), as well as several other families, are part of the

Cod icefish (Nototheniidae), as well as several other families, are part of the Notothenioidei

Notothenioidei is one of 19 suborders of the order Perciformes. The group is found mainly in Antarctic and Subantarctic waters, with some species ranging north to southern Australia and southern South America. Notothenioids constitute approximat ...

suborder, collectively sometimes referred to as icefish. The suborder contains many species with antifreeze protein

Antifreeze proteins (AFPs) or ice structuring proteins refer to a class of polypeptides produced by certain animals, plants, fungi and bacteria that permit their survival in temperatures below the freezing point of water. AFPs bind to small ...

s in their blood and tissue, allowing them to live in water that is around or slightly below . Antifreeze proteins are also known from Southern Ocean snailfish and eelpouts.

There are two icefish species from the genus '' Dissostichus'', the Antarctic toothfish (''D. mawsoni'') and the Patagonian toothfish (''D. eleginoides''), which by far are the largest fish in the Southern Ocean. These two species live on the seafloor from relatively shallow water to depths of , and can grow to around long weighing up to , living up to 45 years. The Antarctic toothfish lives close to the Antarctic mainland, whereas the Patagonian toothfish lives in the relatively warmer subantarctic waters. Toothfish are commercially fished, and illegal overfishing has reduced toothfish populations.

Another abundant icefish group is the genus '' Notothenia'', which like the Antarctic toothfish have antifreeze in their bodies.

An unusual species of icefish is the Antarctic silverfish (''Pleuragramma antarcticum''), which is the only truly pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean and can be further divided into regions by depth. The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or water column between the sur ...

fish in the waters near Antarctica.

Mammals

Six

Six pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant families Odobenidae (whose onl ...

species inhabit Antarctica. The largest, the Southern elephant seal

The southern elephant seal (''Mirounga leonina'') is one of two species of elephant seals. It is the largest member of the clade Pinnipedia and the order Carnivora, as well as the largest extant marine mammal that is not a cetacean. It gets its ...

(''Mirounga leonina''), can reach up to and over long, while females of the smallest, the Antarctic fur seal (''Arctophoca'' ''gazella''), reach only . These two species live north of the sea ice, and breed in harems

A harem is a domestic space that is reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A harem may house a man's wife or wives, their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic Domestic worker, servants, and other un ...

on beaches. The other four species can live on the sea ice. Crabeater seal

The crabeater seal (''Lobodon carcinophaga''), also known as the krill-eater seal, is a true seal with a circumpolar distribution around the coast of Antarctica. They are the only member of the genus ''Lobodon''. They are medium- to large-sized ( ...

s (''Lobodon carcinophagus'') and Weddell seal

The Weddell seal (''Leptonychotes weddellii'') is a relatively large and abundant Earless seal, true seal with a Subantarctic, circumpolar distribution surrounding Antarctica. The Weddell seal was discovered and named in the 1820s during expediti ...

s (''Leptonychotes weddellii'') form breeding colonies, whereas leopard seal

The leopard seal (''Hydrurga leptonyx''), also referred to as the sea leopard, is the second largest species of seal in the Antarctic (after the southern elephant seal). It is a top order predator, feeding on a wide range of prey including cep ...

s (''Hydrurga leptonyx'') and Ross seals (''Ommatophoca rossii'') live solitary lives. Although these species hunt underwater, they breed on land or ice and spend a great deal of time there, as they have no terrestrial predators.

The four species that inhabit sea ice are thought to make up 50% of the total biomass of the world's seals. Crabeater seals have a population of around 15 million, making them one of the most numerous large animals on the planet. The New Zealand sea lion (''Phocarctos hookeri''), one of the rarest and most localized pinnipeds, breeds almost exclusively on the subantarctic Auckland Islands

The Auckland Islands ( Māori: ''Motu Maha'' "Many islands" or ''Maungahuka'' "Snowy mountains") are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying , is surrounded by smaller Adams Island ...

, although historically it had a wider range. Out of all permanent mammalian residents, the Weddell seals live the furthest south.

There are 10 cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

species found in the Southern Ocean; six baleen whale

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the order (biology), parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankt ...

s, and four toothed whale

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed wha ...

s. The largest of these, the blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

(''Balaenoptera musculus''), grows to long weighing 84 tonnes. Many of these species are migratory, and travel to tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

waters during the Antarctic winter. Orca

The orca (''Orcinus orca''), or killer whale, is a toothed whale and the largest member of the oceanic dolphin family. The only extant species in the genus '' Orcinus'', it is recognizable by its black-and-white-patterned body. A cosmopol ...

s, which do not migrate, nonetheless regularly travel to warmer waters, possibly to relieve the stress the temperature has on their skin.

Land invertebrates

Most terrestrial

Most terrestrial invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s are restricted to the subantarctic islands. Although there are very few species, those that do inhabit Antarctica have high population densities. In the more extreme areas of the mainland, such as the cold deserts, food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Position in the food web, or trophic level, is used in ecology to broadly classify organisms as autotrophs or he ...

s are sometimes restricted to three nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

species, only one of which is a predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

. Many invertebrates on the subantarctic islands can live in subzero temperatures without freezing, whereas those on the mainland can survive being frozen.

Mites

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods) of two large orders, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari. However, most recent genetic analyses do not recover the two as eac ...

and springtail

Springtails (class Collembola) form the largest of the three lineages of modern Hexapoda, hexapods that are no longer considered insects. Although the three lineages are sometimes grouped together in a class called Entognatha because they have in ...

s make up most terrestrial arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

species, although various spiders, beetles, and flies can be found. Several thousand individuals from various mite and springtail species can be found in . Beetles and flies are the most species rich insect groups on the islands. Insects play an important role in recycling dead plant material.

The mainland of Antarctica has no macro-arthropods. Micro-arthropods are restricted to areas with vegetation and nutrients provided by the presence of vertebrates, and where liquid water can be found. ''Belgica antarctica

''Belgica antarctica'', the Antarctic midge, is a species of flightless midge, endemic to the continent of Antarctica. At long, it is the largest purely terrestrial animal native to the continent. It also has the smallest known insect genome as ...

'', a wingless midge

A midge is any small fly, including species in several family (biology), families of non-mosquito nematoceran Diptera. Midges are found (seasonally or otherwise) on practically every land area outside permanently arid deserts and the frigid ...

, is the only true insect found on the mainland. With sizes ranging from , it is the mainland's largest terrestrial animal.

There are also several lakes where various species of planktonic crustaceans live.

Many terrestrial earthworms and molluscs, along with micro-invertebrates, such as nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

s, tardigrade

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who called them . In 1776, th ...

s, and rotifer

The rotifers (, from Latin 'wheel' and 'bearing'), sometimes called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic Coelom#Pseudocoelomates, pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first describ ...

s, are also found. Earthworms, along with insects, are important decomposer

Decomposers are organisms that break down dead organisms and release the nutrients from the dead matter into the environment around them. Decomposition relies on chemical processes similar to digestion in animals; in fact, many sources use the word ...

s.

The springtail

Springtails (class Collembola) form the largest of the three lineages of modern Hexapoda, hexapods that are no longer considered insects. Although the three lineages are sometimes grouped together in a class called Entognatha because they have in ...

'' Gomphiocephalus hodgsoni'' is endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

and restricted to southern Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78th parallel south, 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Ant ...

between Mt. George Murray (75°55′S) and Minna Bluff (78°28′S) and to the adjacent nearshore islands. Insects endemic to Antarctica include:

*'' Belgica albipes'', a midge

*''Belgica antarctica

''Belgica antarctica'', the Antarctic midge, is a species of flightless midge, endemic to the continent of Antarctica. At long, it is the largest purely terrestrial animal native to the continent. It also has the smallest known insect genome as ...

'', a midge

*'' Siphlopteryx antarctica'', a fly

Springtail

Springtails (class Collembola) form the largest of the three lineages of modern Hexapoda, hexapods that are no longer considered insects. Although the three lineages are sometimes grouped together in a class called Entognatha because they have in ...

species identified in recent research:

*'' Antarcticinella monoculata''

*'' Cryptopygus antarcticus''

*'' Desoria klovstadi''

*'' Friesea grisea''

*'' Gomphiocephalus hodgsoni''

*'' Gressittacantha terranova''

*'' Cryptopygus nivicolus''

Mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods) of two large orders, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari. However, most recent genetic analyses do not recover the two as eac ...

species identified in recent research:

*'' Coccorhagidia keithi''

*'' Nanorchestes antarcticus''

*'' Stereotydeus mollis''

*'' Tydeus setsukoae''

Marine invertebrates

Arthropods

Five species ofkrill

Krill ''(Euphausiids)'' (: krill) are small and exclusively marine crustaceans of the order (biology), order Euphausiacea, found in all of the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian language, Norwegian word ', meaning "small ...

, small free-swimming crustaceans

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of Arthropod, arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquat ...

, are found in the Southern Ocean. The Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') is a species of krill found in the Antarctica, Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000� ...

(''Euphausia superba'') is one of the most abundant animal species on earth, with a biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

of around 500 million tonnes. Each individual is long and weighs over . The swarms that form can stretch for kilometres, with up to 30,000 individuals per , turning the water red. Swarms usually remain in deep water during the day, ascending during the night to feed on plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

. Many larger animals depend on krill for their own survival. During the winter when food is scarce, adult Antarctic krill can revert to a smaller juvenile stage, using their own body as nutrition.

Many benthic crustaceans have a non-seasonal breeding cycle, and some raise their eggs and young in a brood pouch (they lack a pelagic larvae stage). ''Glyptonotus antarcticus

''Glyptonotus antarcticus'' is a benthic marine isopod crustacean in the suborder Valvifera. This relatively large isopod is found in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. It was first described by James Eights in 1852 and the type locality is ...

'' at up to in length and in weight, and '' Ceratoserolis trilobitoides'' at up to in length are unusually large benthic isopod

Isopoda is an Order (biology), order of crustaceans. Members of this group are called isopods and include both Aquatic animal, aquatic species and Terrestrial animal, terrestrial species such as woodlice. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons ...

s and examples of Polar gigantism. Amphipods

Amphipoda () is an order (biology), order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods () range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 10,700 amphip ...

are abundant in soft sediments, eating a range of items, from algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

to other animals. The amphipods are highly diverse with more than 600 recognized species found south of the Antarctic Convergence and there are indications that many undescribed species remain. Among these are several "giants", such as the iconic epimeriids that are up to long.

Crabs have traditionally not been recognized as part of the fauna in the Antarctic region, but studies in the last few decades have found a few species (mostly king crabs) in deep water. This initially led to fears (frequently quoted in the mainstream media) that they were invading from more northern regions because of global warming

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes ...

and possibly could cause serious damage to the native fauna, but more recent studies show they too are native and formerly simply had been overlooked. Nevertheless, many species from these southern oceans are extremely vulnerable to temperature changes, being unable to survive even a small warming of the water. Although a few specimens of the non-native great spider crab (''Hyas araneus'') were captured at the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

in 1986, there have been no further records from the region.

Slow moving sea spider

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the class (biology), class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after ''Pycnogonum'', the type genus; with the suffix '). The class includes the only now-living order (biology), order P ...

s are common, sometimes growing up to about in leg span (another example of Polar gigantism). Roughly 20% of the sea spider species in the world are from Antarctic waters. They feed on the coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

s, sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s, and bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary Colony (biology), colonies. Typically about long, they have a spe ...

ns that litter the seabed.

Mollusks

Many aquatic

Many aquatic mollusk

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The ...

s are present in Antarctica. Bivalves

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified exoskeleton consis ...

such as '' Adamussium colbecki'' move around on the seafloor, while others such as '' Laternula elliptica'' live in burrows filtering

Filtration is a physical process that separates solid matter and fluid from a mixture.

Filter, filtering, filters or filtration may also refer to:

Science and technology

Computing

* Filter (higher-order function), in functional programming

* Fil ...

the water above. There are around 70 cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

species in the Southern Ocean, the largest of which is the colossal squid (''Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni''), which at up to is among the largest invertebrates in the world. Squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

make up most of the diet of some animals, such as gray-headed albatrosses and sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

s, and the warty squid (''Moroteuthis ingens'') is one of the subantarctic's most preyed upon species by vertebrates.

Other marine invertebrates

The red Antarctic sea urchin (''Sterechinus neumayeri'') has been used in several studies and has become a

The red Antarctic sea urchin (''Sterechinus neumayeri'') has been used in several studies and has become a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

. This is by far the best-known sea urchin of the region, but not the only species. Among others, the Southern Ocean is also home to the genus '' Abatus'' that burrow through the sediment eating the nutrients they find in it. Several species of brittle star

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids (; ; referring to the serpent-like arms of the brittle star) are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomot ...

s and sea stars live in Antarctic waters, including the ecologically important '' Odontaster validus'' and the long-armed ''Labidiaster annulatus

''Labidiaster annulatus'', the Antarctic sun starfish or wolftrap starfish is a species of starfish in the Family (biology), family Heliasteridae. It is found in the cold waters around Antarctica and has a large number of slender, flexible rays.

...

''.

Two species of salp

A salp (: salps, also known colloquially as “sea grape”) or salpa (: salpae or salpas) is a barrel-shaped, Plankton, planktonic tunicate in the family Salpidae. The salp moves by contracting its gelatinous body in order to pump water thro ...

s are common in Antarctic waters, '' Salpa thompsoni'' and '' Ihlea racovitzai''. ''Salpa thompsoni'' is found in ice-free areas, whereas ''Ihlea racovitzai'' is found in the high latitude areas near ice. Due to their low nutritional value, they are normally only eaten by fish, with larger animals such as birds and marine mammals only eating them when other food is scarce.

Several species of marine worms are found in the Southern Ocean, including '' Parborlasia corrugatus'' and '' Eulagisca gigantea'', which at lengths up to and respectively are examples of Polar gigantism.

Like several other marine species of the region, Antarctic sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s are long-lived. They are sensitive to environmental changes due to the specificity of the symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

microbial communities within them. As a result, they function as indicators of environmental health. The largest is the whitish or dull yellowish '' Anoxycalyx joubini'', sometimes called the giant volcano sponge in reference to its shape. It can reach a height of and is an important habitat for several smaller organisms. Long-term observation of individuals of this locally common glass sponge

Hexactinellid sponges are sponges with a skeleton made of four- and/or six-pointed silica, siliceous spicule (sponge), spicules, often referred to as glass sponges. They are usually biological classification, classified along with other sponges i ...

revealed no growth, leading to suggestions of a huge age, perhaps up to 15,000 years (making it one of the longest-lived organisms). However, more recent observations have revealed a highly variable growth rate where individuals seemingly could lack any visible growth for decades, but another was observed to increase its size by almost 30% in only two years and one reached a weight of in about 20 years or less.

Jellyfish are also found there, with 2 examples being the Ross Sea jellyfish and the cobweb jellyfish or giant Antarctic jellyfish. The former is small, at in diameter, while the latter can have 1 metre bell diameter and 5-metre-long tentacles.

Fungi

Fungal

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one of the tradit ...

diversity in Antarctica is lower than in the rest of the world. Individual niches, determined by environmental factors, are filled by very few species. Roughly 1150 fungi species have been identified. Lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

s account for 400 of these, while 750 are non-lichenized. Only around 20 species of fungi are macroscopic.

The non-lichenized species come from 416 different genera, representing all major fungi phyla. The first fungi identified from the subantarctic islands was '' Peziza kerguelensis'', which was described in 1847. In 1898 the first species from the mainland, '' Sclerotium antarcticum'', was sampled. Far more terrestrial species have been identified than marine species. Larger species are restricted to the subantarctic islands and the Antarctic Peninsula. Parasitic species have been found in ecological situations different from the one they are associated with elsewhere, such as infecting a different type of host. Less than 2-3% of species are thought to be endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

. Many species are shared with areas of the Arctic. Most fungi are thought to have arrived in Antarctica via airborne currents or birds. The genus '' Thelebolus'' for example, arrived on birds some times ago, but have since evolved local strains. Of the non-lichenized species of fungi and closer relatives of fungi discovered, 63% are ascomycota

Ascomycota is a phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, forms the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi or ascomycetes. It is the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species. The def ...

, 23% are basidiomycota

Basidiomycota () is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Basi ...

, 5% are zygomycota

Zygomycota, or zygote fungi, is a former phylum, division or phylum of the kingdom Fungi. The members are now part of two Phylum, phyla: the Mucoromycota and Zoopagomycotina, Zoopagomycota. Approximately 1060 species are known. They are mostly t ...

, and 3% are chytridiomycota

Chytridiomycota are a division of zoosporic organisms in the kingdom Fungi, informally known as chytrids. The name is derived from the Ancient Greek ('), meaning "little pot", describing the structure containing unreleased zoospores. Chytrid ...

. The myxomycota and oomycota make up 1% each, although they are not true fungi.

The desert surface is hostile to microscopic fungi due to large fluctuations in temperature on the surface of rocks, which range from 2 °C below the air temperature in the winter to 20 °C above air temperature in the summer. However, the more stable nanoenvironments inside the rocks allow microbial populations to develop. Most communities consist of only a few species. The most studied community occurs in sandstone, and different species arrange themselves in bands at different depths from the rock surface. Microscopic fungi, especially yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

s, have been found in all Antarctic environments.

Antarctica has around 400 lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

species, plants and fungi living symbiotically. They are highly adapted, and can be divided into three main types; crustose

Crustose is a Habit (biology), habit of some types of algae and lichens in which the organism grows tightly appressed to a substrate, forming a biological layer. ''Crustose'' adheres very closely to the Substrate (biology), substrates at all poin ...

lichens, forming thin crusts on the surface, foliose

A foliose lichen is a lichen with flat, leaf-like , which are generally not firmly bonded to the substrate on which it grows. It is one of the three most common lichen growth forms, growth forms of lichens. It typically has distinct upper and lo ...

lichens, forming leaf-like lobes, and fruticose lichens, which grow like shrubs. Species are generally divided between those found on the subantarctic islands, those found on the Peninsula, those found elsewhere on the mainland, and those with disjointed distribution. The furthest south a lichen has been identified is 86°30'. Growth rates range from every 100 years in the more favourable areas to every 1000 years in the more inhospitable areas, and usually occurs when the lichen are protected from the elements with a thin layer of snow, which they can often absorb water vapour from.

Lichens

Macrolichens (e.g., '' Usnea sphacelata'', '' U. antarctica'', '' Umbilicaria decussate'', and '' U. aprina'') and communities of weakly or non-nitrophilous lichens (e.g., '' Pseudephebe minuscula'', '' Rhizocarpon superficial'', and '' R. geographicum'', and several species of '' Acarospora'' and ''Buellia

''Buellia'' is a genus of mostly lichen-forming fungi in the family Caliciaceae. The fungi are usually part of a crustose lichen. In this case, the lichen species is given the same name as the fungus. But members may also grow as parasites on lic ...

'') are relatively widespread in coastal ice-free areas. Sites with substrates influenced by seabirds are colonized by well-developed communities of nitrophilous lichen species such as '' Caloplaca athallina'', '' C. citrina'', '' Candelariella flava'', '' Lecanora expectans'', '' Physcia caesia'', '' Rhizoplaca melanophthalma'', '' Xanthoria elegans'', and '' X. mawsonii''. In the Dry Valleys the normally epilithic lichen species ('' Acarospora gwynnii'', '' Buellia frigida'', '' B. grisea'', '' B. pallida'', '' Carbonea vorticosa'', '' Lecanora fuscobrunnea'', '' L. cancriformis'', and '' Lecidella siplei'') are found primarily in protected niches beneath the rock surface occupying a cryptoendolithic ecological niche.

Lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

species identified in recent research:

*'' Acarospora'' spp.

**'' Acarospora gwynnii''

*''Buellia

''Buellia'' is a genus of mostly lichen-forming fungi in the family Caliciaceae. The fungi are usually part of a crustose lichen. In this case, the lichen species is given the same name as the fungus. But members may also grow as parasites on lic ...

'' spp.

**'' Buellia frigida''

**'' Buellia grisea''

**'' Buellia pallida''

*'' Caloplaca athallina''

*''Caloplaca citrina

''Caloplaca'' is a lichen genus comprising a number of distinct species. Members of the genus are List of common names of lichen genera, commonly called firedot lichen, jewel lichen.Field Guide to California Lichens, Stephen Sharnoff, Yale Unive ...

''

*'' Candelariella flava''

*'' Carbonea vorticosa'' (form. '' Carbonea capsulata'')

*'' Lecanora cancriformis''

*'' Lecanora expectans''

*'' Lecanora fuscobrunnea''

*'' Lecidella siplei'' (form. '' Lecidea siplei'')

*'' Physcia caesia''

*'' Pseudephebe minuscula''

*''Rhizocarpon geographicum

''Rhizocarpon geographicum'' (the map lichen) is a species of lichen, which grows on rocks in mountainous areas of low air pollution. Each lichen is a flat patch bordered by a black line of fungal hyphae. These patches grow adjacent to each other ...

''

*'' Rhizocarpon superficial''

*'' Rhizoplaca melanophthalma''

*'' Umbilicaria aprina''

*'' Umbilicaria decussate''

*'' Usnea antarctica''

*'' Usnea sphacelata''

*'' Xanthoria elegans''

*'' Xanthoria mawsonii''

Plants

The greatest

The greatest plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

diversity is found on the western edge of the Antarctic Peninsula. Coastal algal blooms can cover up to of the peninsula. Well-adapted moss and lichen can be found in rocks throughout the continent. The subantarctic islands are a more favourable environment for plant growth than the mainland. Human activities, especially whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales for their products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that was important in the Industrial Revolution. Whaling was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16t ...

and sealing, have caused many introduced species to gain a foothold on the islands, some quite successfully.

Some plant communities exist around fumarole

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or another rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

s, vents emitting steam and gas that can reach at around below the surface. This produces a warmer environment with liquid water due to melting snow and ice. The active volcano Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the southernmost active volcano on Earth, located on Ross Island in the Ross Dependency in Antarctica. With a summit elevation of , it is the second most prominent mountain in Antarctica (after Mount Vinson) and the second ...

and the dormant Mount Melbourne

Mount Melbourne is a ice-covered stratovolcano in Victoria Land, Antarctica, between Wood Bay and Terra Nova Bay. It is an elongated mountain with a summit caldera filled with ice with numerous parasitic vents; a volcanic field surrounds th ...

, both in the continent's interior, each host a fumarole. Two fumaroles also exist on the subantarctic islands, one caused by a dormant volcano on Deception Island

Deception Island is in the South Shetland Islands close to the Antarctic Peninsula with a large and usually "safe" natural harbour, which is occasionally affected by the underlying active volcano. This island is the caldera of an active volc ...

in the South Shetland Islands and one on the South Sandwich Islands

The South Sandwich Islands () are a chain of uninhabited volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. They are administered as part of the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The chain lies in the sub-A ...

. The fumarole on Deception Island also supports moss species found nowhere else in Antarctica.

The

The bryophytes

Bryophytes () are a group of land plants ( embryophytes), sometimes treated as a taxonomic division referred to as Bryophyta '' sensu lato'', that contains three groups of non-vascular land plants: the liverworts, hornworts, and mosses. In t ...

of Antarctica consist of 100 species of moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

es, and about 25 species of liverwort

Liverworts are a group of non-vascular land plants forming the division Marchantiophyta (). They may also be referred to as hepatics. Like mosses and hornworts, they have a gametophyte-dominant life cycle, in which cells of the plant carry ...

s. While not being as widespread as lichens, they remain ubiquitous wherever plants can grow, with '' Ceratodon purpureus'' being found as far south as 84°30' on Mount Kyffin. Unlike most bryophytes, a majority of Antarctic bryophytes do not enter a diploid sporophyte

A sporophyte () is one of the two alternation of generations, alternating multicellular organism, multicellular phases in the biological life cycle, life cycles of plants and algae. It is a diploid multicellular organism which produces asexual Spo ...

stage, instead they reproduce asexually or have sex organs on their gametophyte

A gametophyte () is one of the two alternating multicellular phases in the life cycles of plants and algae. It is a haploid multicellular organism that develops from a haploid spore that has one set of chromosomes. The gametophyte is the se ...

stage. Only 30% of bryophytes on the Peninsular and subantarctic islands have a sporophyte stage, and only 25% of those on the rest of the mainland produce sporophytes. The Mount Melbourne fumarole supports the only Antarctic population of '' Campylopus pyriformis'', which is otherwise found in Europe and South Africa.

Subantarctic flora is dominated by the coastal tussock grass, that can grow up to . Only two flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (). The term angiosperm is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek words (; 'container, vessel') and (; 'seed'), meaning that the seeds are enclosed with ...

s inhabit continental Antarctica, the Antarctic hair grass (''Deschampsia antarctica'') and the Antarctic pearlwort

''Colobanthus quitensis'', also known as the Antarctic pearlwort, is one of two native flowering plants found in the Antarctic region, the other being Deschampsia antarctica, Antarctic hair grass. It has yellow flowers and grows about tall, givi ...

(''Colobanthus quitensis''). Both are found only on the western edge of the Antarctic Peninsula and on two nearby island groups, the South Orkney Islands

The South Orkney Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands, islands in the Southern Ocean, about north-east of the tip of the Antarctic PeninsulaSouth Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

.

Mosses

The moss species '' Campylopus pyriformis'' is restricted to geothermal sites.Moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

species identified in recent research:

*'' Anomobryum subrotundifolium''

*'' Bryoerythrophyllum recurvirostre''

*'' Bryum anomobryum''

*'' Bryum pseudotriquetrum''

*'' Campylopus pyriformis''

*'' Cephaloziella varians''

*'' Ceratodon purpureus''

*'' Didymodon brachyphyllus''

*'' Grimmia plagiopodia''

*'' Hennediella heimii''

*'' Pohlia nutans''

*'' Sarconeurum glaciale''

*'' Schistidium antarctici'' (form. '' Grimmia antarctici'')

*'' Syntrichia princeps''

Others

Bacteria have been revived from Antarctic snow hundreds of years old. They have also been found deep under the ice, in Lake Whillans, part of a network ofsubglacial lake

A subglacial lake is a lake that is found under a glacier, typically beneath an ice cap or ice sheet. Subglacial lakes form at the boundary between ice and the underlying bedrock, where liquid water can exist above the lower melting point of ic ...

s that sunlight does not reach.

A wide variety of algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

are found in Antarctica, often forming the base of food webs. About 400 species of single-celled phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

that float in the water column of the Southern Ocean have been identified. These plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

bloom annually in the spring and summer as day length increases and sea ice retreats, before lowering in number during the winter.

Other algae live in or on the sea ice, often on its underside, or on the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

in shallow areas. Over 700 seaweed species have been identified, of which 35% are endemic. Outside of the ocean many algae are found in freshwater both on the continent and on the subantarctic islands. Terrestrial algae, such as snow algae, have been found living in soil as far south as 86° 29'. Most are single-celled. In summer algal blooms can cause snow and ice to appear red, green, orange, or gray. These blooms can reach about 106 cells per mL. The dominant group of snow algae is chlamydomonas

''Chlamydomonas'' ( ) is a genus of green algae consisting of about 150 species of unicellular organism, unicellular flagellates, found in stagnant water and on damp soil, in freshwater, seawater, and even in snow as "snow algae". ''Chlamydom ...

, a type of green algae

The green algae (: green alga) are a group of chlorophyll-containing autotrophic eukaryotes consisting of the phylum Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister group that contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants ...

.

The largest marine algae are kelp

Kelps are large brown algae or seaweeds that make up the order (biology), order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genus, genera. Despite its appearance and use of photosynthesis in chloroplasts, kelp is technically not a plant but a str ...

species, which include bull kelp (''Durvillaea antarctica

''Durvillaea antarctica'', also known as ' and ', is a large, robust species of southern bull kelp found on the coasts of Chile, southern New Zealand, and Macquarie Island.Smith, J.M.B. and Bayliss-Smith, T.P. (1998). Kelp-plucking: coastal eros ...

''), which can reach over long and is thought to be the strongest kelp in the world. As many as 47 individual plants can live on , and they can grow at a day. Kelp that is broken off its anchor provides a valuable food source for many animals, as well as providing a method of oceanic dispersal

Oceanic dispersal is a type of biological dispersal that occurs when Terrestrial animal, terrestrial organisms transfer from one land mass to another by way of a sea crossing. Island hopping is the crossing of an ocean by a series of shorter jour ...

for animals such as invertebrates to travel across the Southern Ocean by riding floating kelp.

Conservation

Human activity poses significant risk for Antarctic wildlife, causing problems such as pollution, habitat destruction, and wildlife disturbance. These problems are especially acute around research stations.

Human activity poses significant risk for Antarctic wildlife, causing problems such as pollution, habitat destruction, and wildlife disturbance. These problems are especially acute around research stations. Climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

and its associated effects pose significant risk to the future of Antarctica's natural environment.

Due to the historical isolation of Antarctic wildlife, they are easily outcompeted and threatened by introduced species

An introduced species, alien species, exotic species, adventive species, immigrant species, foreign species, non-indigenous species, or non-native species is a species living outside its native distributional range, but which has arrived ther ...

, also brought by human activity. Many introduced species have already established themselves, with rats a particular threat, especially to nesting seabirds whose eggs they eat. Illegal fishing

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) is an issue around the world. Fishing industry observers believe IUU occurs in most fisheries, and accounts for up to 30% of total catches in some important fisheries.

Illegal fishing takes pl ...

remains an issue, as overfishing poses a great threat to krill and toothfish populations. Toothfish, slow-growing, long-lived fish that have previously suffered from overfishing, are particularly at risk. Illegal fishing also brings further risks through the use of techniques banned in regulated fishing, such as gillnetting

Gillnetting is a fishing method that uses gillnets: vertical panels of netting that hang from a line with regularly spaced floaters that hold the line on the surface of the water. The floats are sometimes called "corks" and the line with corks is ...

and longline fishing

Longline fishing, or longlining, is a commercial fishing angling technique that uses a long ''main line'' with baited hooks attached at intervals via short branch lines called ''snoods'' or ''gangions''.bycatch

Bycatch (or by-catch), in the fishing industry, is a fish or other marine species that is caught unintentionally while fishing for specific species or sizes of wildlife. Bycatch is either the wrong species, the wrong sex, or is undersized or juve ...

of animals such as albatrosses.

Subantarctic islands fall under the jurisdiction of national governments, with environmental regulation following the laws of those countries. Some islands are in addition protected through obtaining the status of a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

. The Antarctic Treaty System

The Antarctic Treaty and related agreements, collectively known as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), regulate international relations with respect to Antarctica, Earth's only continent without a native human population. It was the first arms ...

regulates all activity in latitudes south of 60°S, and designates Antarctica as a natural reserve for science. Under this system all activity must be assessed for its environmental impact. Part of this system, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, also known as the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, and CCAMLR, is part of the Antarctic Treaty System.

The convention was opened for s ...

, regulates fishing and protects marine areas.

References

Further reading

* {{AntarcticaAntarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...