Washington Irving on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "

The Irving family settled in Manhattan, and were part of the city's merchant class. Washington was born on April 3, 1783, the same week that New York City residents learned of the British ceasefire which ended the

The Irving family settled in Manhattan, and were part of the city's merchant class. Washington was born on April 3, 1783, the same week that New York City residents learned of the British ceasefire which ended the

Irving returned from Europe to study law with his legal mentor Judge

Irving returned from Europe to study law with his legal mentor Judge

Irving completed '' A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker'' (1809) while mourning the death of his 17-year-old fiancée Matilda Hoffman. It was his first major book and a satire on self-important local history and contemporary politics. Before its publication, Irving started a hoax by placing a series of missing person advertisements in New York newspapers seeking information on Diedrich Knickerbocker, a crusty Dutch historian who had allegedly gone missing from his hotel in New York City. As part of the ruse, he placed a notice from the hotel's proprietor informing readers that, if Mr. Knickerbocker failed to return to the hotel to pay his bill, he would publish a manuscript that Knickerbocker had left behind.

Unsuspecting readers followed the story of Knickerbocker and his manuscript with interest, and some New York city officials were concerned enough about the missing historian to offer a reward for his safe return. Irving then published ''A History of New York'' on December 6, 1809, under the Knickerbocker pseudonym, with immediate critical and popular success. "It took with the public", Irving remarked, "and gave me celebrity, as an original work was something remarkable and uncommon in America". The name Diedrich Knickerbocker became a nickname for Manhattan residents in general and was adopted by the

Irving completed '' A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker'' (1809) while mourning the death of his 17-year-old fiancée Matilda Hoffman. It was his first major book and a satire on self-important local history and contemporary politics. Before its publication, Irving started a hoax by placing a series of missing person advertisements in New York newspapers seeking information on Diedrich Knickerbocker, a crusty Dutch historian who had allegedly gone missing from his hotel in New York City. As part of the ruse, he placed a notice from the hotel's proprietor informing readers that, if Mr. Knickerbocker failed to return to the hotel to pay his bill, he would publish a manuscript that Knickerbocker had left behind.

Unsuspecting readers followed the story of Knickerbocker and his manuscript with interest, and some New York city officials were concerned enough about the missing historian to offer a reward for his safe return. Irving then published ''A History of New York'' on December 6, 1809, under the Knickerbocker pseudonym, with immediate critical and popular success. "It took with the public", Irving remarked, "and gave me celebrity, as an original work was something remarkable and uncommon in America". The name Diedrich Knickerbocker became a nickname for Manhattan residents in general and was adopted by the

Irving spent the next two years trying to bail out the family firm financially but eventually had to declare bankruptcy. With no job prospects, he continued writing throughout 1817 and 1818. In the summer of 1817, he visited

Irving spent the next two years trying to bail out the family firm financially but eventually had to declare bankruptcy. With no job prospects, he continued writing throughout 1817 and 1818. In the summer of 1817, he visited

With both Irving and publisher John Murray eager to follow up on the success of ''The Sketch Book'', Irving spent much of 1821 travelling in Europe in search of new material, reading widely in Dutch and German folk tales. Hampered by writer's block—and depressed by the death of his brother William—Irving worked slowly, finally delivering a completed manuscript to Murray in March 1822. The book, ''Bracebridge Hall, or The Humorists, A Medley'' (the location was based loosely on

With both Irving and publisher John Murray eager to follow up on the success of ''The Sketch Book'', Irving spent much of 1821 travelling in Europe in search of new material, reading widely in Dutch and German folk tales. Hampered by writer's block—and depressed by the death of his brother William—Irving worked slowly, finally delivering a completed manuscript to Murray in March 1822. The book, ''Bracebridge Hall, or The Humorists, A Medley'' (the location was based loosely on

With full access to the American consul's massive library of Spanish history, Irving began working on several books at once. The first offspring of this hard work, ''

With full access to the American consul's massive library of Spanish history, Irving began working on several books at once. The first offspring of this hard work, ''

Irving arrived in New York on May 21, 1832, after 17 years abroad. That September, he accompanied Commissioner on Indian Affairs Henry Leavitt Ellsworth on a surveying mission, along with companions

Irving arrived in New York on May 21, 1832, after 17 years abroad. That September, he accompanied Commissioner on Indian Affairs Henry Leavitt Ellsworth on a surveying mission, along with companions  In 1835, Irving purchased a "neglected cottage" and its surrounding riverfront property in Tarrytown, New York, which he named Sunnyside in 1841. It required constant repair and renovation over the next 20 years, with costs continually escalating, so he reluctantly agreed to become a regular contributor to '' The Knickerbocker'' magazine in 1839, writing new essays and short stories under the Knickerbocker and Crayon pseudonyms. He was regularly approached by aspiring young authors for advice or endorsement, including Edgar Allan Poe, who sought Irving's comments on " William Wilson" and "

In 1835, Irving purchased a "neglected cottage" and its surrounding riverfront property in Tarrytown, New York, which he named Sunnyside in 1841. It required constant repair and renovation over the next 20 years, with costs continually escalating, so he reluctantly agreed to become a regular contributor to '' The Knickerbocker'' magazine in 1839, writing new essays and short stories under the Knickerbocker and Crayon pseudonyms. He was regularly approached by aspiring young authors for advice or endorsement, including Edgar Allan Poe, who sought Irving's comments on " William Wilson" and "

Irving returned from Spain in September 1846, took up residence at Sunnyside, and began work on an "Author's Revised Edition" of his works for publisher

Irving returned from Spain in September 1846, took up residence at Sunnyside, and began work on an "Author's Revised Edition" of his works for publisher

Irving is largely credited as the first American Man of Letters and the first to earn his living solely by his pen. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow acknowledged Irving's role in promoting American literature in December 1859: "We feel a just pride in his renown as an author, not forgetting that, to his other claims upon our gratitude, he adds also that of having been the first to win for our country an honourable name and position in the History of Letters".

Irving perfected the American short story and was the first American writer to set his stories firmly in the United States, even as he poached from German or Dutch folklore. He is also generally credited as one of the first to write in the vernacular and without an obligation to presenting morals or being didactic in his short stories, writing stories simply to entertain rather than to enlighten. He also encouraged many would-be writers. As

Irving is largely credited as the first American Man of Letters and the first to earn his living solely by his pen. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow acknowledged Irving's role in promoting American literature in December 1859: "We feel a just pride in his renown as an author, not forgetting that, to his other claims upon our gratitude, he adds also that of having been the first to win for our country an honourable name and position in the History of Letters".

Irving perfected the American short story and was the first American writer to set his stories firmly in the United States, even as he poached from German or Dutch folklore. He is also generally credited as one of the first to write in the vernacular and without an obligation to presenting morals or being didactic in his short stories, writing stories simply to entertain rather than to enlighten. He also encouraged many would-be writers. As

Irving popularized the nickname "Gotham" for New York City, and he is credited with inventing the expression "the almighty dollar". The surname of his fictional Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker is generally associated with New York and New Yorkers, as found in New York's professional

Irving popularized the nickname "Gotham" for New York City, and he is credited with inventing the expression "the almighty dollar". The surname of his fictional Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker is generally associated with New York and New Yorkers, as found in New York's professional

The village of Dearman, New York, changed its name to " Irvington" in 1854 to honor Washington Irving, who was living in nearby Sunnyside, which is preserved as a museum. Influential residents of the village prevailed upon the Hudson River Railroad, which had reached the village by 1849,Dodsworth (1995) to change the name of the train station to "Irvington", and the village incorporated as Irvington on April 16, 1872.

The town of

The village of Dearman, New York, changed its name to " Irvington" in 1854 to honor Washington Irving, who was living in nearby Sunnyside, which is preserved as a museum. Influential residents of the village prevailed upon the Hudson River Railroad, which had reached the village by 1849,Dodsworth (1995) to change the name of the train station to "Irvington", and the village incorporated as Irvington on April 16, 1872.

The town of

Tennessee Place Names

' (Indiana University Press, 2001), p. 107.

online

* Apap, Christopher, and Tracy Hoffman. "Prospects for the Study of Washington Irving". ''Resources for American Literary Study'' 35 (2010): 3-27

online

* Bowden, Edwin T. ''Washington Irving bibliography'' (1989

online

* Brodwin, Stanley. ''The Old and New World romanticism of Washington Irving'' (1986

online

* Brooks, Van Wyck. ''The World Of Washington Irving'' (1944

online

* Burstein, Andrew. ''The Original Knickerbocker: The Life of Washington Irving''. (Basic Books, 2007). * Bowers, Claude G. ''The Spanish Adventures of Washington Irving''. (Riverside Press, 1940). * Hedges, William L. ''Washington Irving: An American Study, 1802-1832'' (Johns Hopkins UP, 2019). * Hellman, George S. ''Washington Irving, Esquire''. (Alfred A. Knopf, 1925). * Jones, Brian Jay. ''Washington Irving: An American Original''. (Arcade, 2008). * LeMenager, Stephanie. "Trading Stories: Washington Irving and the Global West". ''American Literary History'' 15.4 (2003): 683-708

online

* McGann, Jerome. "Washington Irving", A History of New York", and American History". ''Early American Literature'' 47.2 (2012): 349-376

online

* Myers, Andrew B., ed. ''A Century of commentary on the works of Washington Irving, 1860-1974'' (1975

online

* Pollard, Finn. "From beyond the grave and across the ocean: Washington Irving and the problem of being a questioning American, 1809–20". ''American Nineteenth Century History'' 8.1 (2007): 81-101. * Springer, Haskell S. ''Washington Irving: a reference guide'' (1976

online

* Williams, Stanley T. ''The Life of Washington Irving.'' 2 vols. (Oxford UP, 1935)

vol 1 online

als

vol 2 online

online

Washington Irving letters

at Lehigh University'

* ttp://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/mountholyoke/mshm083_main.html Irving letter, 1854 Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections

Washington Irving at Poets' Corner

(theOtherPages.org/poems) * "A Day with Washington Irving", published 1859 in '' Once a Week''

Washington Irving Cultural Route

in Spain *

Finding Aid for the Washington Irving Collection of Papers, 1805–1933

at the New York Public Library

Guide to Timothy Hopkins' Washington Irving collection, 1683–1839

– five 5 volumes of letters at th

a

Stanford University Libraries

Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the

Rip Van Winkle

"Rip Van Winkle" is a short story by the American author Washington Irving, first published in 1819. It follows a Dutch-American villager in colonial America named Rip Van Winkle who meets mysterious Dutchmen, imbibes their liquor and falls aslee ...

" (1819) and " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820), both of which appear in his collection ''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.

''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.'', commonly referred to as ''The Sketch Book'', is a collection of 34 essays and short stories written by the American author Washington Irving. It was published serially throughout 1819 and 1820. The co ...

'' His historical works include biographies of Oliver Goldsmith, Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

and George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, as well as several histories of 15th-century Spain that deal with subjects such as Alhambra, Christopher Columbus and the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

. Irving served as American ambassador to Spain in the 1840s.

Born and raised in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

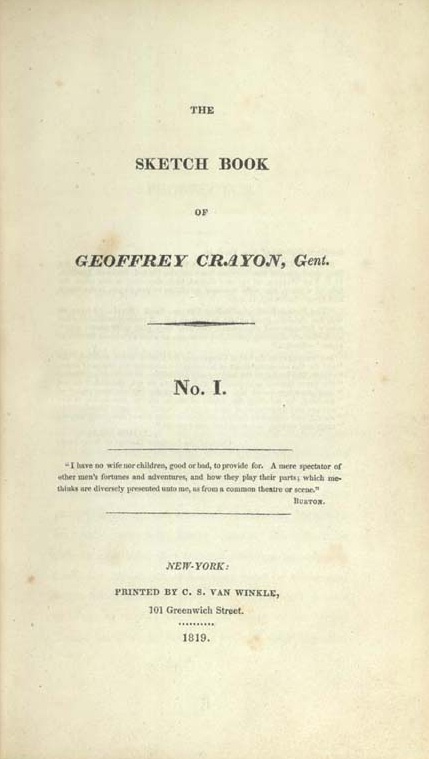

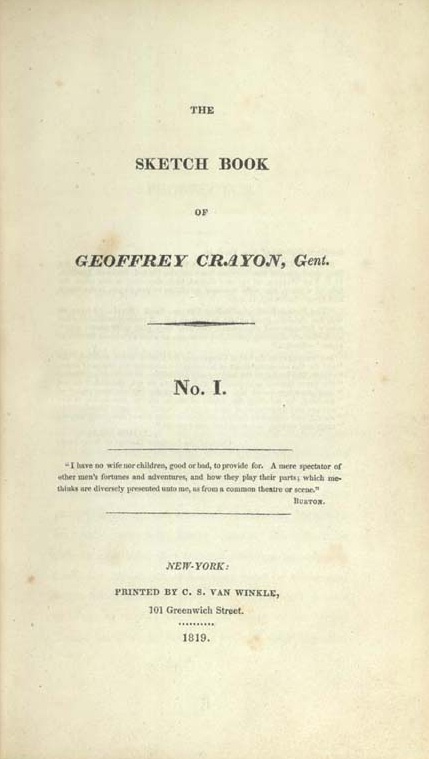

to a merchant family, Irving made his literary debut in 1802 with a series of observational letters to the ''Morning Chronicle'', written under the pseudonym Jonathan Oldstyle. He temporarily moved to England for the family business in 1815 where he achieved fame with the publication of ''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.'', serialized from 1819 to 1820. He continued to publish regularly throughout his life, and he completed a five-volume biography of George Washington just eight months before his death at age 76 in Tarrytown, New York.

Irving was one of the first American writers to earn acclaim in Europe, and he encouraged other American authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

, Herman Melville and Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wid ...

. He was also admired by some British writers, including Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

, Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (; ; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist who wrote the Gothic novel '' Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' (1818), which is considered an early example of science fiction. She also ...

, Francis Jeffrey

Francis Jeffrey, Lord Jeffrey (23 October 1773 – 26 January 1850) was a Scottish judge and literary critic.

Life

He was born at 7 Charles Street near Potterow in south Edinburgh, the son of George Jeffrey, a clerk in the Court of Session ...

and Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

. He advocated for writing as a legitimate profession and argued for stronger laws to protect American writers from copyright infringement.

Biography

Early years

Washington Irving's parents were William Irving Sr., originally of Quholm,Shapinsay

Shapinsay (, sco, Shapinsee) is one of the Orkney Islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. There is one village on the island, Balfour, from which roll-on/roll-off car ferries sail to Kirkwall on the Orkney Mainland. Balfour Castle ...

, Orkney, Scotland, and Sarah (née Saunders), originally of Falmouth, Cornwall

Falmouth ( ; kw, Aberfala) is a town, civil parish and port on the River Fal on the south coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It has a total resident population of 21,797 (2011 census).

Etymology

The name Falmouth is of English ...

, England. They married in 1761 while William was serving as a petty officer in the British Navy. They had eleven children, eight of whom survived to adulthood. Their first two sons died in infancy, both named William, as did their fourth child John. Their surviving children were William Jr. (1766), Ann (1770), Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

(1771), Catherine (1774), Ebenezer (1776), John Treat (1778), Sarah (1780), and Washington.Burstein, 7.

The Irving family settled in Manhattan, and were part of the city's merchant class. Washington was born on April 3, 1783, the same week that New York City residents learned of the British ceasefire which ended the

The Irving family settled in Manhattan, and were part of the city's merchant class. Washington was born on April 3, 1783, the same week that New York City residents learned of the British ceasefire which ended the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

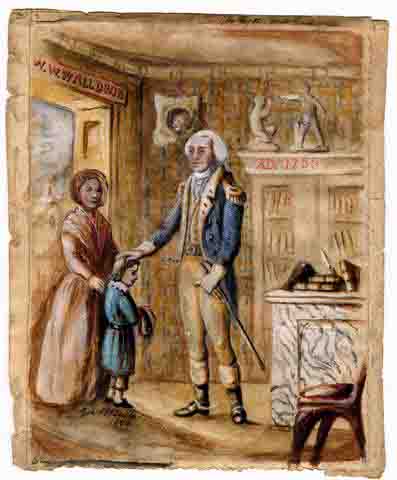

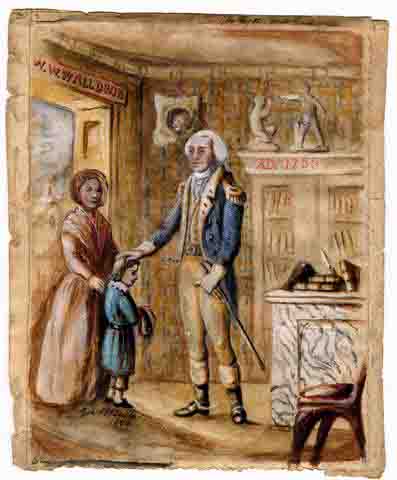

. Irving's mother named him after George Washington. Irving met his namesake at age 6 when George Washington was living in New York after his inauguration as President in 1789. The President blessed young Irving, an encounter that Irving had commemorated in a small watercolor painting which continues to hang in his home.

The Irvings lived at 131 William Street at the time of Washington's birth, but they later moved across the street to 128 William St. Several of Irving's brothers became active New York merchants; they encouraged his literary aspirations, often supporting him financially as he pursued his writing career.

Irving was an uninterested student who preferred adventure stories and drama, and he regularly sneaked out of class in the evenings to attend the theater by the time he was 14. An outbreak of yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

in Manhattan in 1798 prompted his family to send him upriver, where he stayed with his friend James Kirke Paulding in Tarrytown, New York. It was in Tarrytown he became familiar with the nearby town of Sleepy Hollow, New York, with its Dutch customs and local ghost stories. He made several other trips up the Hudson as a teenager, including an extended visit to Johnstown, New York

Johnstown is a city in and the county seat of Fulton County in the U.S. state of New York. The city was named after its founder, Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Province of New York and a major general during the Sev ...

where he passed through the Catskill Mountains region, the setting for "Rip Van Winkle

"Rip Van Winkle" is a short story by the American author Washington Irving, first published in 1819. It follows a Dutch-American villager in colonial America named Rip Van Winkle who meets mysterious Dutchmen, imbibes their liquor and falls aslee ...

". "Of all the scenery of the Hudson", Irving wrote, "the Kaatskill Mountains had the most witching effect on my boyish imagination".

Irving began writing letters to the New York ''Morning Chronicle'' in 1802 when he was 19, submitting commentaries on the city's social and theater scene under the pseudonym Jonathan Oldstyle. The name evoked his Federalist leanings and was the first of many pseudonyms he employed throughout his career. The letters bought Irving some early fame and moderate notoriety. Aaron Burr was a co-publisher of the ''Chronicle'', and was impressed enough to send clippings of the Oldstyle pieces to his daughter Theodosia. Charles Brockden Brown

Charles Brockden Brown (January 17, 1771 – February 22, 1810) was an American novelist, historian, and editor of the Early National period. He is generally regarded by scholars as the most important American novelist before James Fenimore ...

made a trip to New York to try to recruit Oldstyle for a literary magazine he was editing in Philadelphia.

Concerned for his health, Irving's brothers financed an extended tour of Europe from 1804 to 1806. He bypassed most of the sites and locations considered essential for the social development of a young man, to the dismay of his brother William who wrote that he was pleased that his brother's health was improving, but he did not like the choice to "''gallop through Italy''… leaving Florence on your left and Venice on your right".Burstein, 43. Instead, Irving honed the social and conversational skills that eventually made him one of the world's most in-demand guests. "I endeavor to take things as they come with cheerfulness", Irving wrote, "and when I cannot get a dinner to suit my taste, I endeavor to get a taste to suit my dinner". While visiting Rome in 1805, Irving struck up a friendship with painter Washington Allston and was almost persuaded into a career as a painter. "My lot in life, however, was differently cast".

First major writings

Irving returned from Europe to study law with his legal mentor Judge

Irving returned from Europe to study law with his legal mentor Judge Josiah Ogden Hoffman

Josiah Ogden Hoffman (April 14, 1766 – January 24, 1837) was an American lawyer and politician.

Early life

Josiah Ogden Hoffman was born on April 14, 1766, in Newark, New Jersey, the son of Nicholas Hoffman (1736–1800) and Sarah Ogden Hoffma ...

in New York City. By his own admission, he was not a good student and barely passed the bar examination in 1806. He began socializing with a group of literate young men whom he dubbed "The Lads of Kilkenny", and he created the literary magazine ''Salmagundi

Salmagundi (or salmagundy or sallid magundi) is a cold dish or salad made from different ingredients which may include meat, seafood, eggs, cooked vegetables, raw vegetables, fruits or pickles. In English culture, the term does not refer to a s ...

'' in January 1807 with his brother William and his friend James Kirke Paulding, writing under various pseudonyms, such as William Wizard and Launcelot Langstaff. Irving lampooned New York culture and politics in a manner similar to the 20th century ''Mad'' magazine. ''Salmagundi'' was a moderate success, spreading Irving's name and reputation beyond New York. He gave New York City the nickname "Gotham" in its 17th issue dated November 11, 1807, an Anglo-Saxon word meaning "Goat's Town".

Irving completed '' A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker'' (1809) while mourning the death of his 17-year-old fiancée Matilda Hoffman. It was his first major book and a satire on self-important local history and contemporary politics. Before its publication, Irving started a hoax by placing a series of missing person advertisements in New York newspapers seeking information on Diedrich Knickerbocker, a crusty Dutch historian who had allegedly gone missing from his hotel in New York City. As part of the ruse, he placed a notice from the hotel's proprietor informing readers that, if Mr. Knickerbocker failed to return to the hotel to pay his bill, he would publish a manuscript that Knickerbocker had left behind.

Unsuspecting readers followed the story of Knickerbocker and his manuscript with interest, and some New York city officials were concerned enough about the missing historian to offer a reward for his safe return. Irving then published ''A History of New York'' on December 6, 1809, under the Knickerbocker pseudonym, with immediate critical and popular success. "It took with the public", Irving remarked, "and gave me celebrity, as an original work was something remarkable and uncommon in America". The name Diedrich Knickerbocker became a nickname for Manhattan residents in general and was adopted by the

Irving completed '' A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker'' (1809) while mourning the death of his 17-year-old fiancée Matilda Hoffman. It was his first major book and a satire on self-important local history and contemporary politics. Before its publication, Irving started a hoax by placing a series of missing person advertisements in New York newspapers seeking information on Diedrich Knickerbocker, a crusty Dutch historian who had allegedly gone missing from his hotel in New York City. As part of the ruse, he placed a notice from the hotel's proprietor informing readers that, if Mr. Knickerbocker failed to return to the hotel to pay his bill, he would publish a manuscript that Knickerbocker had left behind.

Unsuspecting readers followed the story of Knickerbocker and his manuscript with interest, and some New York city officials were concerned enough about the missing historian to offer a reward for his safe return. Irving then published ''A History of New York'' on December 6, 1809, under the Knickerbocker pseudonym, with immediate critical and popular success. "It took with the public", Irving remarked, "and gave me celebrity, as an original work was something remarkable and uncommon in America". The name Diedrich Knickerbocker became a nickname for Manhattan residents in general and was adopted by the New York Knickerbockers

The New York Knickerbockers were one of the first organized baseball teams which played under a set of rules similar to the game today. Founded as the "Knickerbocker Base Ball Club" by Alexander Cartwright in 1845, the team remained active unti ...

basketball team.

After the success of ''A History of New York'', Irving searched for a job and eventually became an editor of '' Analectic Magazine'', where he wrote biographies of naval heroes such as James Lawrence

James Lawrence (October 1, 1781 – June 4, 1813) was an officer of the United States Navy. During the War of 1812, he commanded in a single-ship action against , commanded by Philip Broke. He is probably best known today for his last words, ...

and Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry (August 23, 1785 – August 23, 1819) was an American naval commander, born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The best-known and most prominent member

of the Perry family naval dynasty, he was the son of Sarah Wallace A ...

. He was also among the first magazine editors to reprint Francis Scott Key's poem "Defense of Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack ...

", which was immortalized as "The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the b ...

". Irving initially opposed the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

like many other merchants, but the British attack on Washington, D.C. in 1814 convinced him to enlist. He served on the staff of Daniel Tompkins

Daniel D. Tompkins (June 21, 1774 – June 11, 1825) was an American politician. He was the fifth governor of New York from 1807 to 1817, and the sixth vice president of the United States from 1817 to 1825.

Born in Scarsdale, New York, Tompkins ...

, governor of New York and commander of the New York State Militia, but he saw no real action apart from a reconnaissance mission in the Great Lakes region. The war was disastrous for many American merchants, including Irving's family, and he left for England in mid-1815 to salvage the family trading company. He remained in Europe for the next 17 years.

Life in Europe

''The Sketch Book''

Irving spent the next two years trying to bail out the family firm financially but eventually had to declare bankruptcy. With no job prospects, he continued writing throughout 1817 and 1818. In the summer of 1817, he visited

Irving spent the next two years trying to bail out the family firm financially but eventually had to declare bankruptcy. With no job prospects, he continued writing throughout 1817 and 1818. In the summer of 1817, he visited Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

, beginning a lifelong personal and professional friendship.

Irving composed the short story "Rip Van Winkle" overnight while staying with his sister Sarah and her husband, Henry van Wart in Birmingham, England

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, a place that inspired other works, as well. In October 1818, Irving's brother William secured for Irving a post as chief clerk to the United States Navy and urged him to return home. Irving turned the offer down, opting to stay in England to pursue a writing career.

In the spring of 1819, Irving sent to his brother Ebenezer in New York a set of short prose pieces that he asked be published as ''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.

''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.'', commonly referred to as ''The Sketch Book'', is a collection of 34 essays and short stories written by the American author Washington Irving. It was published serially throughout 1819 and 1820. The co ...

'' The first installment, containing "Rip Van Winkle", was an enormous success, and the rest of the work would be equally successful; it was issued in 1819–1820 in seven installments in New York, and in two volumes in London ("The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" would appear in the sixth issue of the New York edition, and the second volume of the London edition).

Like many successful authors of this era, Irving struggled against literary bootleggers. In England, some of his sketches were reprinted in periodicals without his permission, a legal practice as there was no international copyright law at the time. To prevent further piracy in Britain, Irving paid to have the first four American installments published as a single volume by John Miller in London.

Irving appealed to Walter Scott for help procuring a more reputable publisher for the remainder of the book. Scott referred Irving to his own publisher, London powerhouse John Murray, who agreed to take on ''The Sketch Book''. From then on, Irving would publish concurrently in the United States and Britain to protect his copyright, with Murray as his English publisher of choice.

Irving's reputation soared, and for the next two years, he led an active social life in Paris and Great Britain, where he was often feted as an anomaly of literature: an upstart American who dared to write English well.

''Bracebridge Hall'' and ''Tales of a Traveller''

With both Irving and publisher John Murray eager to follow up on the success of ''The Sketch Book'', Irving spent much of 1821 travelling in Europe in search of new material, reading widely in Dutch and German folk tales. Hampered by writer's block—and depressed by the death of his brother William—Irving worked slowly, finally delivering a completed manuscript to Murray in March 1822. The book, ''Bracebridge Hall, or The Humorists, A Medley'' (the location was based loosely on

With both Irving and publisher John Murray eager to follow up on the success of ''The Sketch Book'', Irving spent much of 1821 travelling in Europe in search of new material, reading widely in Dutch and German folk tales. Hampered by writer's block—and depressed by the death of his brother William—Irving worked slowly, finally delivering a completed manuscript to Murray in March 1822. The book, ''Bracebridge Hall, or The Humorists, A Medley'' (the location was based loosely on Aston Hall

Aston Hall is a Grade I listed Jacobean house in Aston, Birmingham, England, designed by John Thorpe and built between 1618 and 1635. It is a leading example of the Jacobean prodigy house.

In 1864, the house was bought by Birmingham Corpor ...

, occupied by members of the Bracebridge family, near his sister's home in Birmingham) was published in June 1822.

The format of ''Bracebridge'' was similar to that of ''The Sketch Book'', with Irving, as Crayon, narrating a series of more than 50 loosely connected short stories and essays. While some reviewers thought ''Bracebridge'' to be a lesser imitation of ''The Sketch Book'', the book was well received by readers and critics. "We have received so much pleasure from this book", wrote critic Francis Jeffrey in the ''Edinburgh Review'', "that we think ourselves bound in gratitude... to make a public acknowledgement of it". Irving was relieved at its reception, which did much to cement his reputation with European readers.

Still struggling with writer's block, Irving traveled to Germany, settling in Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

in the winter of 1822. Here he dazzled the royal family and attached himself to Amelia Foster, an American living in Dresden with her five children. Irving was particularly attracted to Foster's 18-year-old daughter Emily and vied in frustration for her hand. Emily finally refused his offer of marriage in the spring of 1823.

He returned to Paris and began collaborating with playwright John Howard Payne

John Howard Payne (June 9, 1791 – April 10, 1852) was an American actor, poet, playwright, and author who had nearly two decades of a theatrical career and success in London. He is today most remembered as the creator of "Home! Sweet Home ...

on translations of French plays for the English stage, with little success. He also learned through Payne that the novelist Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was romantically interested in him, though Irving never pursued the relationship.

In August 1824, Irving published the collection of essays '' Tales of a Traveller''—including the short story " The Devil and Tom Walker"—under his Geoffrey Crayon persona. "I think there are in it some of the best things I have ever written", Irving told his sister. But while the book sold respectably, ''Traveller'' was dismissed by critics, who panned both ''Traveller'' and its author. "The public have been led to expect better things", wrote the ''United States Literary Gazette'', while the ''New-York Mirror'' pronounced Irving "overrated". Hurt and depressed by the book's reception, Irving retreated to Paris where he spent the next year worrying about finances and scribbling down ideas for projects that never materialized.

Spanish books

While in Paris, Irving received a letter fromAlexander Hill Everett

Alexander Hill Everett (March 19, 1792 – June 28, 1847) was an American diplomat, politician, and Boston man of letters. Everett held diplomatic posts in the Netherlands, Spain, Cuba, and China. His translations of European literature, publish ...

on January 30, 1826. Everett, recently the American Minister to Spain, urged Irving to join him in Madrid, noting that a number of manuscripts dealing with the Spanish conquest of the Americas had recently been made public. Irving left for Madrid and enthusiastically began scouring the Spanish archives for colorful material.

With full access to the American consul's massive library of Spanish history, Irving began working on several books at once. The first offspring of this hard work, ''

With full access to the American consul's massive library of Spanish history, Irving began working on several books at once. The first offspring of this hard work, ''A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus

''A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus'' is a fictional biographical account of Christopher Columbus written by Washington Irving in 1828. It was published in four volumes in Britain and in three volumes in the United States. ...

'', was published in January 1828. The book was popular in the United States and in Europe and would have 175 editions published before the end of the century. It was also the first project of Irving's to be published with his own name, instead of a pseudonym, on the title page. Irving was invited to stay at the palace of the Duke of Gor, who gave him unfettered access to his library containing many medieval manuscripts.'' Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada'' was published a year later, followed by ''Voyages and Discoveries of the Companions of Columbus'' in 1831.

Irving's writings on Columbus are a mixture of history and fiction, a genre now called romantic history. Irving based them on extensive research in the Spanish archives, but also added imaginative elements aimed at sharpening the story. The first of these works is the source of the durable myth that medieval Europeans believed the Earth was flat. According to the popular book, Columbus proved the Earth was round.

In 1829, Irving was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

. That same year, he moved into Granada's ancient palace Alhambra, "determined to linger here", he said, "until I get some writings under way connected with the place". Before he could get any significant writing underway, however, he was notified of his appointment as Secretary to the American Legation in London. Worried he would disappoint friends and family if he refused the position, Irving left Spain for England in July 1829.

Secretary to the American legation in London

Arriving in London, Irving joined the staff of American Minister Louis McLane. McLane immediately assigned the daily secretary work to another man and tapped Irving to fill the role of aide-de-camp. The two worked over the next year to negotiate a trade agreement between the United States and theBritish West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

, finally reaching a deal in August 1830. That same year, Irving was awarded a medal by the Royal Society of Literature, followed by an honorary doctorate of civil law from Oxford in 1831.

Following McLane's recall to the United States in 1831 to serve as Secretary of Treasury, Irving stayed on as the legation's chargé d'affaires until the arrival of Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's nominee for British Minister. With Van Buren in place, Irving resigned his post to concentrate on writing, eventually completing ''Tales of the Alhambra

''Tales of the Alhambra'' (1832) is a collection of essays, verbal sketches and stories by American author Washington Irving (1783–1859) inspired by, and partly written during, his 1828 visit to the palace/fortress complex known as the Alhambr ...

'', which would be published concurrently in the United States and England in 1832.

Irving was still in London when Van Buren received word that the United States Senate had refused to confirm him as the new Minister. Consoling Van Buren, Irving predicted that the Senate's partisan move would backfire. "I should not be surprised", Irving said, "if this vote of the Senate goes far toward elevating him to the presidential chair".

Return to the United States

Irving arrived in New York on May 21, 1832, after 17 years abroad. That September, he accompanied Commissioner on Indian Affairs Henry Leavitt Ellsworth on a surveying mission, along with companions

Irving arrived in New York on May 21, 1832, after 17 years abroad. That September, he accompanied Commissioner on Indian Affairs Henry Leavitt Ellsworth on a surveying mission, along with companions Charles La Trobe

Charles la Trobe, CB (20 March 18014 December 1875), commonly Latrobe, was appointed in 1839 superintendent of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales and, after the establishment in 1851 of the colony of Victoria (now a state of Austra ...

and Count Albert-Alexandre de Pourtales, and they traveled deep into Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

(now the state of Oklahoma). At the completion of his western tour, Irving traveled through Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, where he became acquainted with politician and novelist John Pendleton Kennedy.

Irving was frustrated by bad investments, so he turned to writing to generate additional income, beginning with ''A Tour on the Prairies'' which related his recent travels on the frontier. The book was another popular success and also the first book written and published by Irving in the United States since ''A History of New York'' in 1809. In 1834, he was approached by fur magnate John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by History of opium in China, smuggl ...

, who convinced him to write a history of his fur trading colony in Astoria, Oregon. Irving made quick work of Astor's project, shipping the fawning biographical account '' Astoria'' in February 1836. In 1835, Irving, Astor, and a few others founded the Saint Nicholas Society in the City of New York.

During an extended stay at Astor's home, Irving met explorer Benjamin Bonneville and was intrigued with his maps and stories of the territories beyond the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

. The two men met in Washington, D.C. several months later, and Bonneville sold his maps and rough notes to Irving for $1,000. Irving used these materials as the basis for his 1837 book ''The Adventures of Captain Bonneville''. These three works made up Irving's "western" series of books and were written partly as a response to criticism that his time in England and Spain had made him more European than American. Critics such as James Fenimore Cooper and Philip Freneau

Philip Morin Freneau (January 2, 1752 – December 18, 1832) was an American poet, nationalist, polemicist, sea captain and early American newspaper editor, sometimes called the "Poet of the American Revolution". Through his newspaper, th ...

felt that he had turned his back on his American heritage in favor of English aristocracy. Irving's western books were well received in the United States, particularly ''A Tour on the Prairies'', though British critics accused him of "book-making".

The Fall of the House of Usher

"The Fall of the House of Usher" is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1839 in ''Burton's Gentleman's Magazine'', then included in the collection ''Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque'' in 1840. The short story ...

".

In 1837, a lady of Charleston, South Carolina brought to the attention of William Clancy

William Clancy (12 February 1802 – 19 June 1847) was an Irish Roman Catholic missionary in the United States and British Guiana.

Life

The son of a farmer, William Clancy was born in West Cork and educated at St. Patrick's, Carlow College in ...

, newly appointed bishop to Demerara

Demerara ( nl, Demerary, ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state ...

, a passage in ''The Crayon Miscellany'', and questioned whether it accurately reflected Catholic teaching or practice. The passage under "Newstead Abbey" read:One of the parchment scrolls thus discovered, throws rather an awkward light upon the kind of life led by the friars of Newstead. It is an indulgence granted to them for a certain number of months, in which a plenary pardon is assured in advance for all kinds of crimes, among which, several of the most gross and sensual are specifically mentioned, and the weaknesses of the flesh to which they were prone.Clancy wrote Irving, who "promptly aided the investigation into the truth, and promised to correct in future editions the misrepresentation complained of". Clancy traveled to his new posting by way of England, and bearing a letter of introduction from Irving, stopped at

Newstead Abbey

Newstead Abbey, in Nottinghamshire, England, was formerly an Augustinian priory. Converted to a domestic home following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it is now best known as the ancestral home of Lord Byron.

Monastic foundation

The prio ...

and was able to view the document to which Irving had alluded. Upon inspection, Clancy discovered that it was, in fact, not an indulgence issued to the friars from any ecclesiastical authority, but a pardon given by the king to some parties suspected of having broken "forest laws". Clancy requested the local pastor to forward his findings to Catholic periodicals in England, and upon publication, send a copy to Irving. Whether this was done is not clear as the disputed text remains in the 1849 edition.

Irving also championed America's maturing literature, advocating stronger copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, educatio ...

laws to protect writers from the kind of piracy that had initially plagued ''The Sketch Book''. Writing in the January 1840 issue of ''Knickerbocker'', he openly endorsed copyright legislation pending in Congress. "We have a young literature", he wrote, "springing up and daily unfolding itself with wonderful energy and luxuriance, which … deserves all its fostering care". The legislation, however, did not pass at that time.

In 1841, Irving was elected to the National Academy of Design

The National Academy of Design is an honorary association of American artists, founded in New York City in 1825 by Samuel Morse, Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, Martin E. Thompson, Charles Cushing Wright, Ithiel Town, and others "to promote the f ...

as an Honorary Academician. He also began a friendly correspondence with Charles Dickens and hosted Dickens and his wife at Sunnyside during Dickens's American tour in 1842.

Minister to Spain

PresidentJohn Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

appointed Irving as Minister to Spain in February 1842, after an endorsement from Secretary of State Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

. Irving wrote, "It will be a severe trial to absent myself for a time from my dear little Sunnyside, but I shall return to it better enabled to carry it on comfortably". He hoped that his position as Minister would allow him plenty of time to write, but Spain was in a state of political upheaval during most of his tenure, with a number of warring factions vying for control of the 12-year-old Queen Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successio ...

. Irving maintained good relations with the various generals and politicians, as control of Spain rotated through Espartero

Baldomero Fernández-Espartero y Álvarez de Toro (27 February 17938 January 1879) was a Spanish marshal and statesman. He served as the Regent of the Realm, three times as Prime Minister and briefly as President of the Congress of Deputies. ...

, Bravo, then Narváez. Espartero was then locked in a power struggle with the Spanish Cortes. Irving's official reports on the ensuing civil war and revolution expressed his romantic fascination with the regent as young Queen Isabella's knight protector, He wrote with an anti-republican, undiplomatic bias. Though Espartero, ousted in July 1843, remained a fallen hero in his eyes, Irving began to view Spanish affairs more realistically. However, the politics and warfare were exhausting, and Irving was both homesick and suffering from a crippling skin condition.

With the political situation relatively settled in Spain, Irving continued to closely monitor the development of the new government and the fate of Isabella. His official duties as Spanish Minister also involved negotiating American trade interests with Cuba and following the Spanish parliament's debates over the slave trade. He was also pressed into service by Louis McLane, the American Minister to the Court of St. James's in London, to assist in negotiating the Anglo-American disagreement over the Oregon border that newly elected president James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

had vowed to resolve.

Final years and death

Irving returned from Spain in September 1846, took up residence at Sunnyside, and began work on an "Author's Revised Edition" of his works for publisher

Irving returned from Spain in September 1846, took up residence at Sunnyside, and began work on an "Author's Revised Edition" of his works for publisher George Palmer Putnam

George Palmer Putnam (February 7, 1814 – December 20, 1872) was an American publisher and author. He founded the firm G. P. Putnam's Sons and '' Putnam's Magazine''. He was an advocate of international copyright reform, secretary for many yea ...

. For its publication, Irving had made a deal which guaranteed him 12 percent of the retail price of all copies sold, an agreement that was unprecedented at that time. As he revised his older works for Putnam, he continued to write regularly, publishing biographies of Oliver Goldsmith in 1849 and Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

in 1850. In 1855, he produced ''Wolfert's Roost'', a collection of stories and essays that he had written for ''The Knickerbocker'' and other publications,Williams, 2:208–209. and he began publishing a biography of his namesake George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

which he expected to be his masterpiece. Five volumes of the biography were published between 1855 and 1859.

Irving traveled regularly to Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

and Washington, D.C. for his research, and struck up friendships with Presidents Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

and Franklin Pierce. He was elected an Associate Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1855. He was hired as an executor of John Jacob Astor's estate in 1848 and appointed by Astor's will as first chairman of the Astor Library, a forerunner to the New York Public Library.

Irving continued to socialize and keep up with his correspondence well into his seventies, and his fame and popularity continued to soar. "I don't believe that any man, in any country, has ever had a more affectionate admiration for him than that given to you in America", wrote Senator William C. Preston in a letter to Irving. "I believe that we have had but one man who is so much in the popular heart". By 1859, author Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. noted that Sunnyside had become "next to Mount Vernon, the best known and most cherished of all the dwellings in our land".

Irving died of a heart attack in his bedroom at Sunnyside on November 28, 1859, age 76—only eight months after completing the final volume of his Washington biography. Legend has it that his last words were: "Well, I must arrange my pillows for another night. When will this end?" He was buried under a simple headstone at Sleepy Hollow cemetery on December 1, 1859. Irving and his grave were commemorated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

in his 1876 poem "In the Churchyard at Tarrytown", which concludes with:

Legacy

Literary reputation

Irving is largely credited as the first American Man of Letters and the first to earn his living solely by his pen. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow acknowledged Irving's role in promoting American literature in December 1859: "We feel a just pride in his renown as an author, not forgetting that, to his other claims upon our gratitude, he adds also that of having been the first to win for our country an honourable name and position in the History of Letters".

Irving perfected the American short story and was the first American writer to set his stories firmly in the United States, even as he poached from German or Dutch folklore. He is also generally credited as one of the first to write in the vernacular and without an obligation to presenting morals or being didactic in his short stories, writing stories simply to entertain rather than to enlighten. He also encouraged many would-be writers. As

Irving is largely credited as the first American Man of Letters and the first to earn his living solely by his pen. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow acknowledged Irving's role in promoting American literature in December 1859: "We feel a just pride in his renown as an author, not forgetting that, to his other claims upon our gratitude, he adds also that of having been the first to win for our country an honourable name and position in the History of Letters".

Irving perfected the American short story and was the first American writer to set his stories firmly in the United States, even as he poached from German or Dutch folklore. He is also generally credited as one of the first to write in the vernacular and without an obligation to presenting morals or being didactic in his short stories, writing stories simply to entertain rather than to enlighten. He also encouraged many would-be writers. As George William Curtis

George William Curtis (February 24, 1824 – August 31, 1892) was an American writer and public speaker born in Providence, Rhode Island. An early Republican, he spoke in favor of African-American equality and civil rights both before and after ...

noted, there "is not a young literary aspirant in the country, who, if he ever personally met Irving, did not hear from him the kindest words of sympathy, regard, and encouragement".

Edgar Allan Poe, on the other hand, felt that Irving should be given credit for being an innovator but that the writing itself was often unsophisticated. "Irving is much over-rated", Poe wrote in 1838, "and a nice distinction might be drawn between his just and his surreptitious and adventitious reputation—between what is due to the pioneer solely, and what to the writer". A critic for the ''New-York Mirror'' wrote: "No man in the Republic of Letters has been more overrated than Mr. Washington Irving". Some critics claimed that Irving catered to British sensibilities, and one critic charged that he wrote "''of'' and ''for'' England, rather than his own country".

Other critics were more supportive of Irving's style. William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

was the first to refer to Irving as the "ambassador whom the New World of Letters sent to the Old", a banner picked up by writers and critics throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. "He is the first of the American humorists, as he is almost the first of the American writers", wrote critic H.R. Hawless in 1881, "yet belonging to the New World, there is a quaint Old World flavor about him". Early critics often had difficulty separating Irving the man from Irving the writer. "The life of Washington Irving was one of the brightest ever led by an author", wrote Richard Henry Stoddard Richard Henry Stoddard (July 2, 1825May 12, 1903) was an American critic and poet.

Biography

Richard Henry Stoddard was born on July 2, 1825, in Hingham, Massachusetts. His father, a sea-captain, was wrecked and lost on one of his voyages while R ...

, an early Irving biographer. Later critics, however, began to review his writings as all style with no substance. "The man had no message", said critic Barrett Wendell

Barrett Wendell (August 23, 1855 – February 8, 1921) was an American academic known for a series of textbooks including ''English Composition,'' studies of ''Cotton Mather'' and ''William Shakespeare,'' ''A Literary History of America,'' ''The F ...

.

As a historian, Irving's reputation had fallen out of favor but then gained a resurgence. "With the advent of 'scientific' history in the generations that followed his, Irving's historical writings lapsed into disregard and disrespect. To late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historians, including John Franklin Jameson, G. P. Gooch

George Peabody Gooch (21 October 1873 – 31 August 1968) was a British journalist, historian and Liberal Party politician. A follower of Lord Acton who was independently wealthy, he never held an academic position, but knew the work of histo ...

, and others, these works were demiromances, worthy at best of veiled condescension. However, more recently several of Irving's histories and biographies have again won praise for their reliability as well as the literary skill with which they were written. Specifically, ''A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus''; ''Astoria, or Anecdotes of an Enterprise beyond the Rocky Mountains''; and ''Life of George Washington'' have earned the respect of scholars whose writings on those topics we consider authoritative in our generation: Samuel Eliot Morison

Samuel Eliot Morison (July 9, 1887 – May 15, 1976) was an American historian noted for his works of maritime history and American history that were both authoritative and popular. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912, and tau ...

, Bernard DeVoto

Bernard Augustine DeVoto (January 11, 1897 – November 13, 1955) was an American historian, conservationist, essayist, columnist, teacher, editor, and reviewer. He was the author of a series of Pulitzer-Prize-winning popular histories of the Ame ...

, Douglas Southall Freeman

Douglas Southall Freeman (May 16, 1886 – June 13, 1953) was an American historian, biographer, newspaper editor, radio commentator, and author. He is best known for his multi-volume biographies of Robert E. Lee and George Washington, for both ...

".Kime, Wayne R. "Washington Irving (3 April 1783-28 November 1859", in Clyde N. Wilson (ed.), ''American Historians, 1607-1865'', Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 30, Detroit: Gale Research, 1984, 155.

Impact on American culture

Irving popularized the nickname "Gotham" for New York City, and he is credited with inventing the expression "the almighty dollar". The surname of his fictional Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker is generally associated with New York and New Yorkers, as found in New York's professional

Irving popularized the nickname "Gotham" for New York City, and he is credited with inventing the expression "the almighty dollar". The surname of his fictional Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker is generally associated with New York and New Yorkers, as found in New York's professional basketball

Basketball is a team sport in which two teams, most commonly of five players each, opposing one another on a rectangular court, compete with the primary objective of shooting a basketball (approximately in diameter) through the defender's h ...

team The New York Knickerbockers

The New York Knickerbockers were one of the first organized baseball teams which played under a set of rules similar to the game today. Founded as the "Knickerbocker Base Ball Club" by Alexander Cartwright in 1845, the team remained active unti ...

.

One of Irving's most lasting contributions to American culture is in the way that Americans celebrate Christmas. In his 1812 revisions to ''A History of New York'', he inserted a dream sequence featuring St. Nicholas

Saint Nicholas of Myra, ; la, Sanctus Nicolaus (traditionally 15 March 270 – 6 December 343), also known as Nicholas of Bari, was an early Christian bishop of Greek descent from the maritime city of Myra in Asia Minor (; modern-day Demre ...

soaring over treetops in a flying wagon, an invention which others dressed up as Santa Claus. In his five Christmas stories in ''The Sketch Book'', Irving portrayed an idealized celebration of old-fashioned Christmas customs at a quaint English manor which depicted English Christmas festivities that he experienced while staying in England, which had largely been abandoned. He used text from ''The Vindication of Christmas'' (London 1652) of old English Christmas traditions, and the book contributed to the revival and reinterpretation of the Christmas holiday in the United States.

Irving introduced the erroneous idea that Europeans believed the world to be flat prior to the discovery of the New World in his biography of Christopher Columbus, yet the flat-Earth myth has been taught in schools as fact to many generations of Americans. American painter John Quidor

John Quidor (January 26, 1801 – December 13, 1881) was an American painter of historical and literary subjects. He has about 35 known canvases, most of which are based on Washington Irving's stories about Dutch New York, drawing inspiration fro ...

based many of his paintings on scenes from the works of Irving about Dutch New York, including such paintings as ''Ichabod Crane Flying from the Headless Horseman'' (1828), ''The Return of Rip Van Winkle'' (1849), and '' The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane'' (1858).

Memorials

The village of Dearman, New York, changed its name to " Irvington" in 1854 to honor Washington Irving, who was living in nearby Sunnyside, which is preserved as a museum. Influential residents of the village prevailed upon the Hudson River Railroad, which had reached the village by 1849,Dodsworth (1995) to change the name of the train station to "Irvington", and the village incorporated as Irvington on April 16, 1872.

The town of

The village of Dearman, New York, changed its name to " Irvington" in 1854 to honor Washington Irving, who was living in nearby Sunnyside, which is preserved as a museum. Influential residents of the village prevailed upon the Hudson River Railroad, which had reached the village by 1849,Dodsworth (1995) to change the name of the train station to "Irvington", and the village incorporated as Irvington on April 16, 1872.

The town of Knickerbocker, Texas

Knickerbocker is an unincorporated community in southwestern Tom Green County, Texas, United States. It lies along Farm to Market Road 2335, southwest of the city of San Angelo, the county seat of Tom Green County. Its elevation is 2,051 f ...

, was founded by two of Irving's nephews, who named it in honor of their uncle's literary pseudonym. The city of Irving, Texas, states that it is named for Washington Irving.

Irving Street in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

is named after him.

The Irving Park neighborhood in Chicago is named for him as well, though the original name of the subdivision was Irvington and then later Irving Park before annexation to Chicago.

Gibbons Memorial Park, located in Honesdale, Pennsylvania

Honesdale is a borough in and the county seat of Wayne County, Pennsylvania, United States. The borough's population was 4,458 at the time of the 2020 census.

Honesdale is located northeast of Scranton in a rural area that provides many recr ...

, is located on Irving Cliff, which was named after him.

The Irvington neighborhood in Indianapolis is also one of the many communities named after him.

Irving College (1838-90) in Irving College, Tennessee, was named for Irving.Larry Miller, Tennessee Place Names

' (Indiana University Press, 2001), p. 107.

Works

References

Further reading

* Aderman, Ralph M. ed. ''Critical essays on Washington Irving'' (1990online

* Apap, Christopher, and Tracy Hoffman. "Prospects for the Study of Washington Irving". ''Resources for American Literary Study'' 35 (2010): 3-27

online

* Bowden, Edwin T. ''Washington Irving bibliography'' (1989

online

* Brodwin, Stanley. ''The Old and New World romanticism of Washington Irving'' (1986

online

* Brooks, Van Wyck. ''The World Of Washington Irving'' (1944

online

* Burstein, Andrew. ''The Original Knickerbocker: The Life of Washington Irving''. (Basic Books, 2007). * Bowers, Claude G. ''The Spanish Adventures of Washington Irving''. (Riverside Press, 1940). * Hedges, William L. ''Washington Irving: An American Study, 1802-1832'' (Johns Hopkins UP, 2019). * Hellman, George S. ''Washington Irving, Esquire''. (Alfred A. Knopf, 1925). * Jones, Brian Jay. ''Washington Irving: An American Original''. (Arcade, 2008). * LeMenager, Stephanie. "Trading Stories: Washington Irving and the Global West". ''American Literary History'' 15.4 (2003): 683-708

online

* McGann, Jerome. "Washington Irving", A History of New York", and American History". ''Early American Literature'' 47.2 (2012): 349-376

online

* Myers, Andrew B., ed. ''A Century of commentary on the works of Washington Irving, 1860-1974'' (1975

online

* Pollard, Finn. "From beyond the grave and across the ocean: Washington Irving and the problem of being a questioning American, 1809–20". ''American Nineteenth Century History'' 8.1 (2007): 81-101. * Springer, Haskell S. ''Washington Irving: a reference guide'' (1976

online

* Williams, Stanley T. ''The Life of Washington Irving.'' 2 vols. (Oxford UP, 1935)

vol 1 online

als

vol 2 online

Primary sources

* Irving, Pierre M. ''Life and Letters of Washington Irving''. 4 vols. (G.P. Putnam, 1862). Cited herein as PMI. * Irving, Washington. ''The Complete Works of Washington Irving''. (Rust, ''et al.'', editors). 30 vols. (University of Wisconsin/Twayne, 1969–1986). Cited herein as ''Works''. * Irving, Washington. (1828) ''History of the Life of Christopher Columbus'', 3 volumes, 1828, G. & C. Carvill, publishers, New York, New York; as 4 volumes, 1828, John Murray, publisher, London; and as 4 volumes, 1828, Paris A. and W. Galignani, publishers, France. * Irving, Washington. (1829) ''The Life and Voyage of Christopher Columbus'', 1 volume, 1829, G. & C. & H. Carvill, publishers, New York, New York; an abridged version prepared by Irving of his 1828 work. * Irving, Washington. ''Selected writings of Washington Irving'' (Modern Library edition, 1945online

External links

* * * *Washington Irving letters

at Lehigh University'

* ttp://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/mountholyoke/mshm083_main.html Irving letter, 1854 Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections

Washington Irving at Poets' Corner

(theOtherPages.org/poems) * "A Day with Washington Irving", published 1859 in '' Once a Week''

Washington Irving Cultural Route

in Spain *

Finding Aid for the Washington Irving Collection of Papers, 1805–1933

at the New York Public Library

Guide to Timothy Hopkins' Washington Irving collection, 1683–1839

– five 5 volumes of letters at th

a

Stanford University Libraries

Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

* Washington Irving Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Irving, Washington

1783 births

1859 deaths

American biographers

American male biographers

American essayists

American satirists

American speculative fiction writers

American travel writers

American people of English descent

American people of Scottish descent

Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

New York (state) lawyers

Writers from Manhattan

Romanticism

Ambassadors of the United States to Spain

American Hispanists

Masterpiece Museum

Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

19th-century American diplomats

Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

American male dramatists and playwrights

American male short story writers

19th-century American short story writers

19th-century American dramatists and playwrights

American male essayists

Presidents of the New York Public Library

19th-century pseudonymous writers