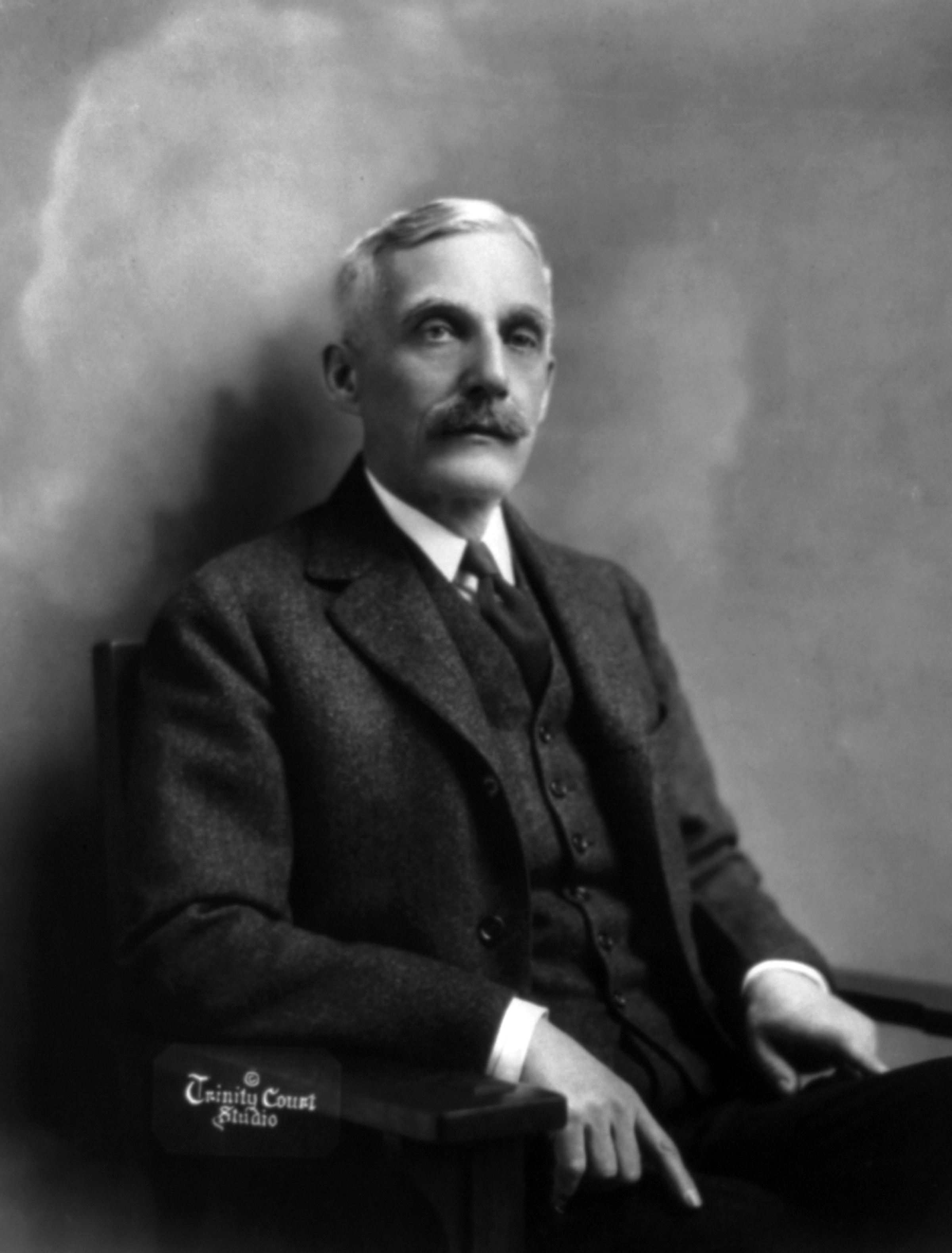

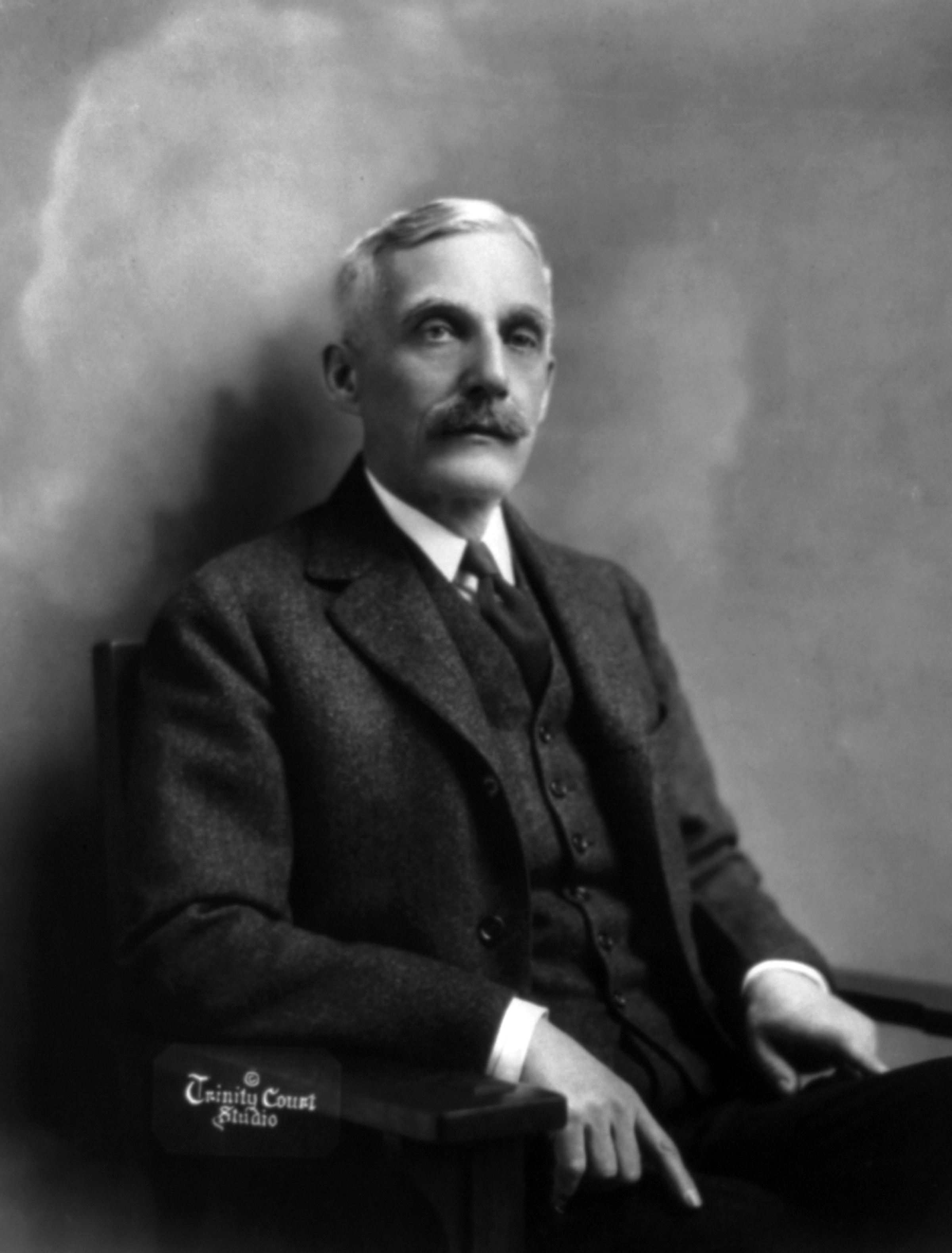

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the

Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents while in office. After his death, a number of scandals were exposed, including

Teapot Dome, as well as an extramarital affair with

Nan Britton, which damaged his reputation.

Harding lived in rural

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

all his life, except when political service took him elsewhere. As a young man, he bought ''

The Marion Star'' and built it into a successful newspaper. Harding served in the

Ohio State Senate from 1900 to 1904, and was

lieutenant governor for two years. He was defeated for governor in

1910, but was elected to the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

in

1914—the state's first direct election for that office. Harding ran for the Republican nomination for president in 1920, but was considered a long shot before the

convention. When the leading candidates could not garner a majority, and the convention deadlocked, support for Harding increased, and he was nominated on the tenth ballot. He conducted a

front porch campaign, remaining mostly in Marion and allowing people to come to him. He promised a

return to normalcy of the pre–

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

period, and defeated

Democratic nominee

James M. Cox in a

landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, rockslips or rockslides, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, mudflows, shallow or deep-seated slope failures and debris flows. Landslides ...

to become the first sitting senator elected president.

Harding appointed a number of respected figures to his

cabinet, including

Andrew Mellon at

Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry; in a business context, corporate treasury.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be ...

,

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

at

Commerce

Commerce is the organized Complex system, system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions that directly or indirectly contribute to the smooth, unhindered large-scale exchange (distribution through Financial transaction, transactiona ...

, and

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

at the

State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

. A major foreign policy achievement came with the

Washington Naval Conference of 1921–1922, in which the world's major naval powers agreed on a naval limitations program that lasted a decade. Harding released political prisoners who had been arrested for their

opposition to World War I

Opposition to World War I was widespread during the conflict and included socialists, such as anarchists, syndicalists, and Marxists, as well as Christian pacifists, anti-colonial nationalists, feminists, Intellectual, intellectuals, and the w ...

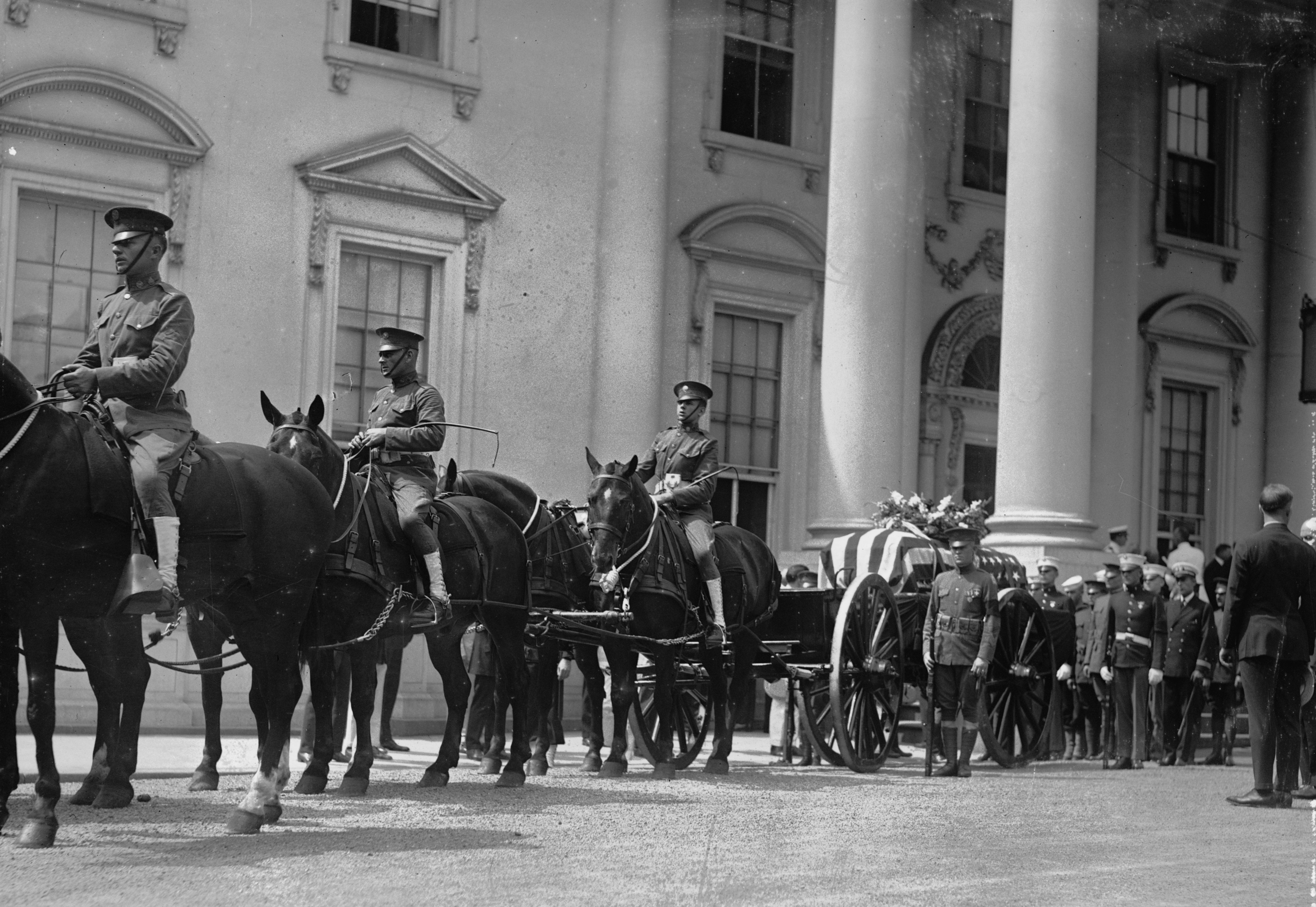

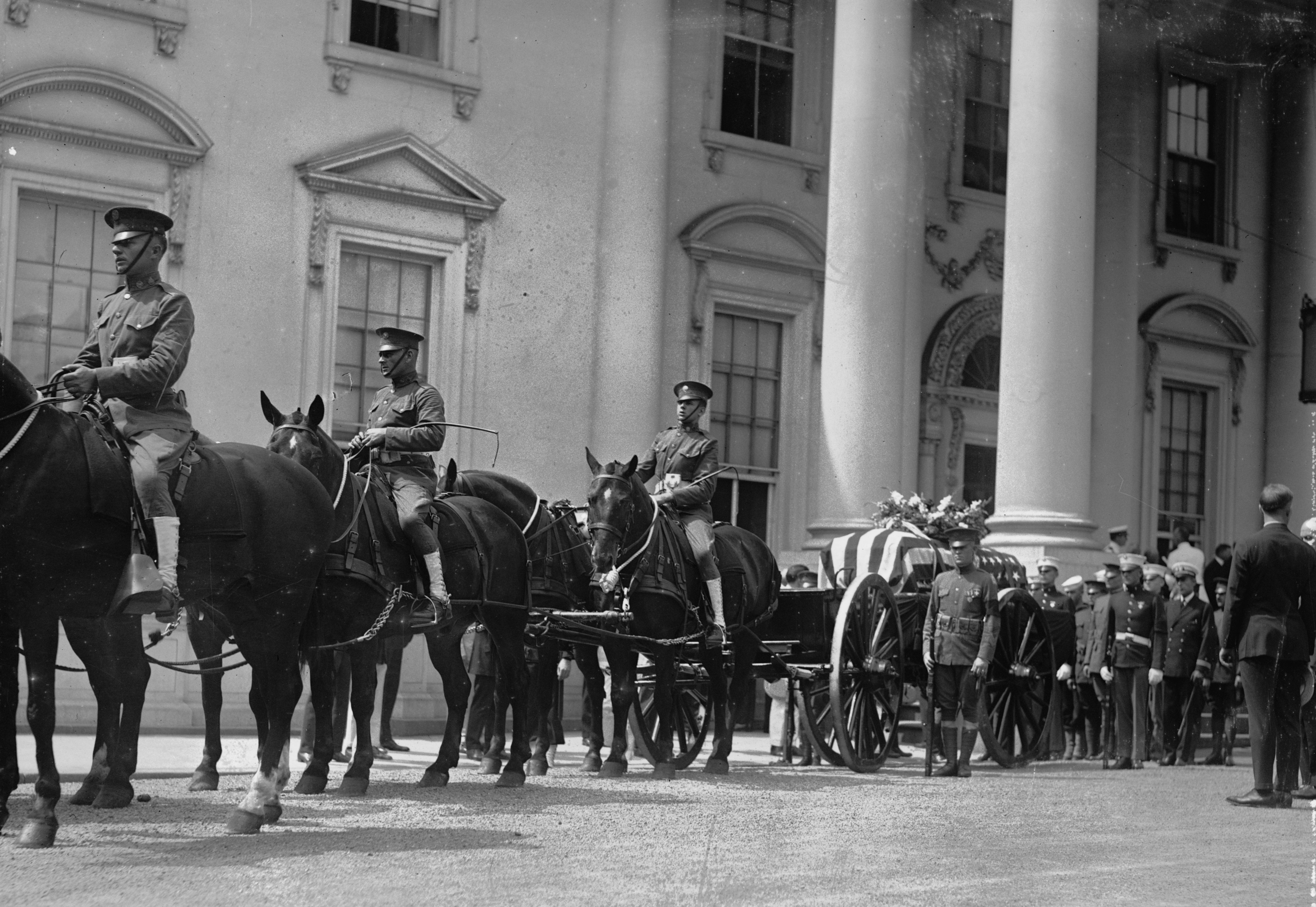

. In 1923, Harding died of a heart attack in San Francisco while on a western tour, and was succeeded by Vice President

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

.

Harding died as one of the most popular presidents in history. The subsequent exposure of scandals eroded his popular regard, as did revelations of extramarital affairs. Harding's interior secretary,

Albert B. Fall, and his

attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

,

Harry Daugherty, were each later tried for corruption in office; Fall was convicted while Daugherty was not, and these trials greatly damaged Harding's posthumous reputation. In

historical rankings of U.S. presidents during the decades after his term in office, Harding was often rated among the worst. In the subsequent decades, some historians have begun to reassess the conventional views of Harding's historical record in office.

Early life and career

Childhood and education

Warren Harding was born on November 2, 1865, in

Blooming Grove, Ohio. Nicknamed "Winnie" as a small child, he was the eldest of eight children born to

George Tryon Harding (usually known as Tryon) and Phoebe Elizabeth (née Dickerson) Harding. Phoebe was a state-licensed

midwife

A midwife (: midwives) is a health professional who cares for mothers and Infant, newborns around childbirth, a specialisation known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughou ...

. Tryon farmed and taught school near

Mount Gilead. Through apprenticeship, study, and a year of medical school, Tryon became a doctor and started a small practice. Harding's first ancestor in the Americas was Richard Harding, who arrived from

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

to

Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its northern and sout ...

around 1624. Harding also had ancestors from Wales and Scotland, and some of his maternal ancestors were Dutch, including the wealthy Van Kirk family.

It was rumored by a political opponent in Blooming Grove that one of Harding's great-grandmothers was

African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

.

His great-great-grandfather Amos Harding claimed that a thief, who had been caught in the act by the family, started the rumor in an attempt at extortion or revenge. In 2015,

genetic testing

Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, or ...

of Harding's descendants determined, with more than a 95% chance of accuracy, that he lacked sub-Saharan African forebears within four generations.

In 1870, the Harding family, who were

abolitionists,

[ moved to Caledonia, where Tryon acquired ''The Argus'', a local weekly newspaper. At ''The Argus'', Harding, from the age of 11, learned the basics of the newspaper business. In late 1879, at age 14, he enrolled at his father's ''alma mater''— Ohio Central College in ]Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

—where he proved an adept student. He and a friend put out a small newspaper, the ''Iberia Spectator'', during their final year at Ohio Central, intended to appeal to both the college and the town. During his final year, the Harding family moved to Marion, about from Caledonia, and when he graduated in 1882, he joined them there.

On May 6, 1883, Harding joined the Free Baptist Church in Marion, where he later served as a trustee for 25 years and of which he remained a member until his death.

Editor

In Harding's youth, most of the U.S. population still lived on farms and in small towns. Harding spent much of his life in Marion, a small city in rural central Ohio, and became closely associated with it. When he rose to high office, he made clear his love of Marion and its way of life, telling of the many young Marionites who had left and enjoyed success elsewhere, while suggesting that the man, once the "pride of the school", who had remained behind and become a janitor, was "the happiest one of the lot".

Upon graduating, Harding had stints as a teacher and as an insurance man, and made a brief attempt at studying law. He then raised $300 () in partnership with others to purchase a failing newspaper, '' The Marion Star'', the weakest of the growing city's three papers and its only daily. The 18-year-old Harding used the railroad pass that came with the paper to attend the 1884 Republican National Convention, where he hobnobbed with better-known journalists and supported the presidential nominee, former Secretary of State James G. Blaine. Harding returned from Chicago to find that the sheriff had reclaimed the paper. During the election campaign, Harding worked for the Marion ''Democratic Mirror'' and was annoyed at having to praise the Democratic presidential nominee, New York Governor Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

, who won the election. Afterward, with his father's financial help, Harding gained ownership of the paper.

Through the later years of the 1880s, Harding built the ''Star''. The city of Marion tended to vote Republican (as did Ohio), but Marion County was Democratic. Accordingly, Harding adopted a tempered editorial stance, declaring the daily ''Star'' nonpartisan and circulating a weekly edition that was moderately Republican. This policy attracted advertisers and put the town's Republican weekly out of business. According to his biographer, Andrew Sinclair:

The population of Marion grew from 4,000 in 1880 to twice that in 1890, and to 12,000 by 1900. This growth helped the ''Star'', and Harding did his best to promote the city, purchasing stock in many local enterprises. A few of these turned out badly, but he was generally successful as an investor, leaving an estate of $850,000 in 1923 (equivalent to $ million in ). According to Harding biographer John Dean, Harding's "civic influence was that of an activist who used his editorial page to effectively keep his nose—and a prodding voice—in all the town's public business". To date, Harding is the only U.S. president to have had full-time journalism experience. He became an ardent supporter of Governor Joseph B. Foraker, a Republican.

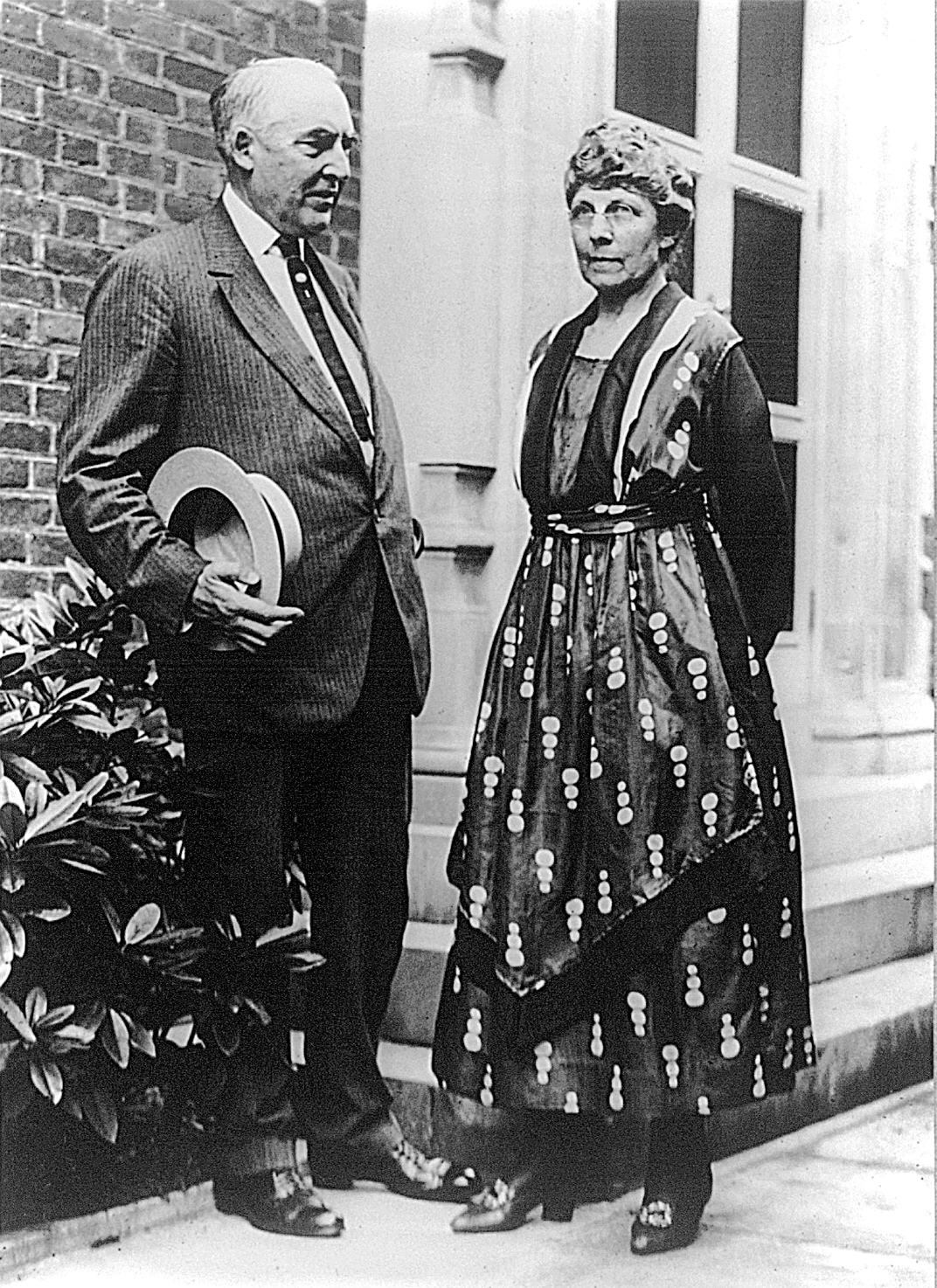

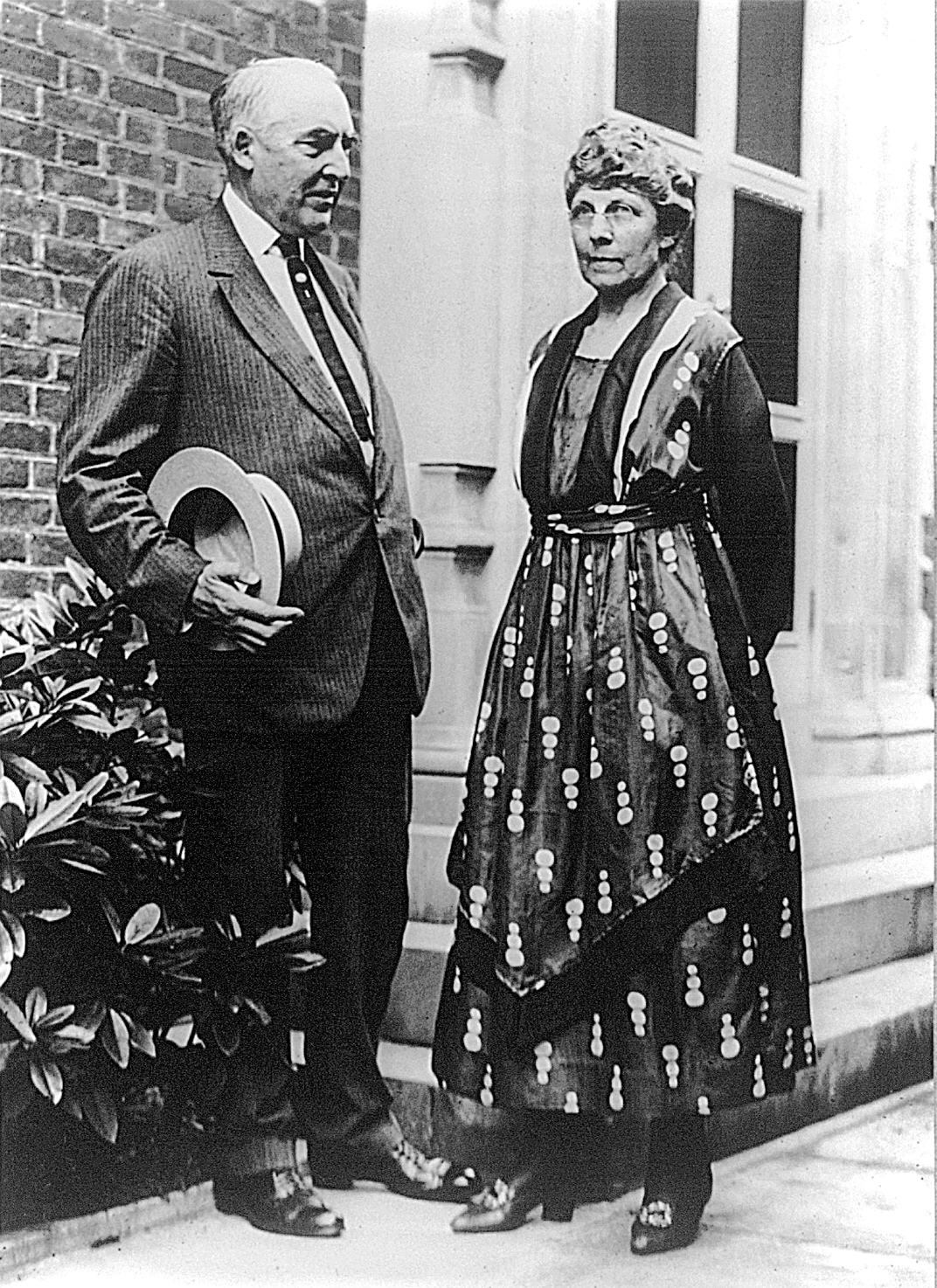

Harding first came to know Florence Kling, five years older than he, as the daughter of a local banker and developer. Amos Kling was a man accustomed to getting his way, but Harding attacked him relentlessly in the paper. Amos involved Florence in all his affairs, taking her to work from the time she could walk. As hard-headed as her father, Florence came into conflict with him after returning from music college. After she eloped with Pete deWolfe, and returned to Marion without deWolfe and with an infant called Marshall, Amos agreed to raise the boy, but would not support Florence, who made a living as a piano teacher. One of her students was Harding's sister Charity. By 1886, Florence Kling had obtained a divorce, and she and Harding were courting, though who was pursuing whom is uncertain.[ When Harding found out what Kling was doing, he warned Kling "that he would beat the tar out of the little man if he didn't cease."

The Hardings married on July 8, 1891, at their new home on Mount Vernon Avenue in Marion, which they had designed together in the Queen Anne style.]The New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative Online newspaper, news website and former newspaper based in Manhattan, Manhattan, New York. From 2009 to 2021, it operated as an (occasional and erratic) onlin ...

'' who kept a close eye on "the Duke" and their money.

Florence Harding became deeply involved in her husband's career, both at the ''Star'' and after he entered politics.

Start in politics

Soon after purchasing the ''Star'', Harding turned his attention to politics, supporting Foraker in his first successful bid for governor in 1885. Foraker was part of the war generation that challenged older Ohio Republicans, such as Senator John Sherman, for control of state politics. Harding, always a party loyalist, supported Foraker in the complex internecine warfare that was Ohio Republican politics. Harding was willing to tolerate Democrats as necessary to a two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually referr ...

, but had only contempt for those who bolted the Republican Party to join third-party movements. He was a delegate to the Republican state convention in 1888, at the age of 22, representing Marion County, and would be elected a delegate in most years until becoming president.

Harding's success as an editor took a toll on his health. Five times between 1889 (when he was 23) and 1901, he spent time at the Battle Creek Sanitorium for reasons Sinclair described as "fatigue, overstrain, and nervous illnesses". Dean ties these visits to early occurrences of the heart ailment that would kill Harding in 1923. During one such absence from Marion, in 1894, the ''Stars business manager quit. Florence Harding took his place. She became her husband's top assistant at the ''Star'' on the business side, maintaining her role until the Hardings moved to Washington in 1915. Her competence allowed Harding to travel to make speeches—his use of the free railroad pass increased greatly after his marriage. Florence Harding practiced strict economy and wrote of Harding, "he does well when he listens to me and poorly when he does not."

In 1892, Harding traveled to Washington, where he met Democratic Nebraska Congressman William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

, and listened to the "Boy Orator of the Platte" speak on the floor of the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

. Harding traveled to Chicago's Columbian Exposition in 1893. Both visits were without Florence. Democrats generally won Marion County's offices; when Harding ran for auditor

An auditor is a person or a firm appointed by a company to execute an audit.Practical Auditing, Kul Narsingh Shrestha, 2012, Nabin Prakashan, Nepal To act as an auditor, a person should be certified by the regulatory authority of accounting an ...

in 1895, he lost, but did better than expected. The following year, Harding was one of many orators who spoke across Ohio as part of the campaign of the Republican presidential candidate, that state's former governor, William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

. According to Dean, "while working for McKinley ardingbegan making a name for himself through Ohio".

Rising politician (1897–1919)

State senator

Harding wished to try again for elective office. Though a longtime admirer of Foraker (by then a U.S. senator), he had been careful to maintain good relations with the party faction led by the state's other U.S. senator, Mark Hanna, McKinley's political manager and chairman of the

Harding wished to try again for elective office. Though a longtime admirer of Foraker (by then a U.S. senator), he had been careful to maintain good relations with the party faction led by the state's other U.S. senator, Mark Hanna, McKinley's political manager and chairman of the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is the primary committee of the Republican Party of the United States. Its members are chosen by the state delegations at the national convention every four years. It is responsible for developing and pr ...

(RNC). Both Foraker and Hanna supported Harding for state Senate in 1899; he gained the Republican nomination and was easily elected to a two-year term.

Harding began his four years as a state senator as a political unknown; he ended them as one of the most popular figures in the Ohio Republican Party. He always appeared calm and displayed humility, characteristics that endeared him to fellow Republicans even as he passed them in his political rise. Legislative leaders consulted him on difficult problems. It was usual at that time for state senators in Ohio to serve only one term, but Harding gained renomination in 1901. After the assassination of McKinley in September (he was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

), much of the appetite for politics was temporarily lost in Ohio. In November, Harding won a second term, more than doubling his margin of victory to 3,563 votes.

During this period, Harding became a Freemason. In 1901, he was initiated into Marion Lodge No. 7.

Like most politicians of his time, Harding accepted that patronage and graft would be used to repay political favors. He arranged for his sister Mary (who was legally blind) to be appointed as a teacher at the Ohio School for the Blind

Ohio State School for the Blind (OSSB or OSB) is a school located in Columbus, Ohio, United States. It is run by the Ohio Department of Education for Blindness, blind and visually impaired students across Ohio. It was established in 1837, making ...

, although there were better-qualified candidates. In another trade, he offered publicity in his newspaper in exchange for free railroad passes for himself and his family. According to Sinclair, "it is doubtful that Harding ever thought there was anything dishonest in accepting the perquisites of position or office. Patronage and favors seemed the normal reward for party service in the days of Hanna."

Soon after Harding's initial election as senator, he met Harry M. Daugherty, who would take a major role in his political career. A perennial candidate for office who served two terms in the state House of Representatives in the early 1890s, Daugherty had become a political fixer and lobbyist in the state capital of Columbus. After first meeting and talking with Harding, Daugherty commented, "Gee, what a great-looking President he'd make."

Ohio state leader

In early 1903, Harding announced he would run for Governor of Ohio, prompted by the withdrawal of the leading candidate, Congressman Charles W. F. Dick. Hanna and George Cox felt that Harding was not electable due to his work with Foraker—as the Progressive Era commenced, the public was starting to take a dimmer view of the trading of political favors and of bosses such as Cox. Accordingly, they persuaded Cleveland banker Myron T. Herrick, a friend of McKinley's, to run. Herrick was also better-placed to take votes away from the likely Democratic candidate, reforming Cleveland Mayor Tom L. Johnson. With little chance at the gubernatorial nomination, Harding sought nomination as lieutenant governor, and both Herrick and Harding were nominated by acclamation. Foraker and Hanna (who died of typhoid fever in February 1904) both campaigned for what was dubbed the Four-H ticket. Herrick and Harding won by overwhelming margins.

Once he and Harding were inaugurated, Herrick made ill-advised decisions that turned crucial Republican constituencies against him, alienating farmers by opposing the establishment of an agricultural college. On the other hand, according to Sinclair, "Harding had little to do, and he did it very well". His responsibility to preside over the state Senate allowed him to increase his growing network of political contacts. Harding and others envisioned a successful gubernatorial run in 1905, but Herrick refused to stand aside. In early 1905, Harding announced he would accept nomination as governor if offered, but faced with the anger of leaders such as Cox, Foraker and Dick (Hanna's replacement in the Senate), announced he would seek no office in 1905. Herrick was defeated, but his new running mate, Andrew L. Harris, was elected, and succeeded as governor after five months in office on the death of Democrat John M. Pattison. One Republican official wrote to Harding, "Aren't you sorry Dick wouldn't let you run for Lieutenant Governor?"

In early 1903, Harding announced he would run for Governor of Ohio, prompted by the withdrawal of the leading candidate, Congressman Charles W. F. Dick. Hanna and George Cox felt that Harding was not electable due to his work with Foraker—as the Progressive Era commenced, the public was starting to take a dimmer view of the trading of political favors and of bosses such as Cox. Accordingly, they persuaded Cleveland banker Myron T. Herrick, a friend of McKinley's, to run. Herrick was also better-placed to take votes away from the likely Democratic candidate, reforming Cleveland Mayor Tom L. Johnson. With little chance at the gubernatorial nomination, Harding sought nomination as lieutenant governor, and both Herrick and Harding were nominated by acclamation. Foraker and Hanna (who died of typhoid fever in February 1904) both campaigned for what was dubbed the Four-H ticket. Herrick and Harding won by overwhelming margins.

Once he and Harding were inaugurated, Herrick made ill-advised decisions that turned crucial Republican constituencies against him, alienating farmers by opposing the establishment of an agricultural college. On the other hand, according to Sinclair, "Harding had little to do, and he did it very well". His responsibility to preside over the state Senate allowed him to increase his growing network of political contacts. Harding and others envisioned a successful gubernatorial run in 1905, but Herrick refused to stand aside. In early 1905, Harding announced he would accept nomination as governor if offered, but faced with the anger of leaders such as Cox, Foraker and Dick (Hanna's replacement in the Senate), announced he would seek no office in 1905. Herrick was defeated, but his new running mate, Andrew L. Harris, was elected, and succeeded as governor after five months in office on the death of Democrat John M. Pattison. One Republican official wrote to Harding, "Aren't you sorry Dick wouldn't let you run for Lieutenant Governor?"

In addition to helping pick a president, Ohio voters in 1908 were to choose the legislators who would decide whether to re-elect Foraker. The senator had quarreled with President Roosevelt over the Brownsville Affair. Though Foraker had little chance of winning, he sought the Republican presidential nomination against his fellow Cincinnatian, Secretary of War

In addition to helping pick a president, Ohio voters in 1908 were to choose the legislators who would decide whether to re-elect Foraker. The senator had quarreled with President Roosevelt over the Brownsville Affair. Though Foraker had little chance of winning, he sought the Republican presidential nomination against his fellow Cincinnatian, Secretary of War William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, who was Roosevelt's chosen successor. On January 6, 1908, Harding's ''Star'' endorsed Foraker and upbraided Roosevelt for trying to destroy the senator's career over a matter of conscience. On January 22, Harding in the ''Star'' reversed course and declared for Taft, deeming Foraker defeated. According to Sinclair, Harding's change to Taft "was not ... because he saw the light but because he felt the heat". Jumping on the Taft bandwagon allowed Harding to survive his patron's disaster—Foraker failed to gain the presidential nomination, and was defeated for a third term as senator. Also helpful in saving Harding's career was that he was popular with, and had done favors for, the more progressive forces that now controlled the Ohio Republican Party.

Harding sought and gained the 1910 Republican gubernatorial nomination. At that time, the party was deeply divided between progressive and conservative wings, and could not defeat the united Democrats; he lost the election to incumbent Judson Harmon. Harry Daugherty managed Harding's campaign, but the defeated candidate did not hold the loss against him. Despite the growing rift between them, both President Taft and former president Roosevelt came to Ohio to campaign for Harding, but their quarrels split the Republican Party and helped assure Harding's defeat.

The party split grew, and in 1912, Taft and Roosevelt were rivals for the Republican nomination. The 1912 Republican National Convention

The 1912 Republican National Convention was held at the Chicago Coliseum, Chicago, Illinois, from June 18 to June 22, 1912. The party nominated President of the United States, President William Howard Taft and Vice President of the United States, ...

was bitterly divided. At Taft's request, Harding gave a speech nominating the president, but the angry delegates were not receptive to Harding's oratory. Taft was renominated, but Roosevelt supporters bolted the party. Harding, as a loyal Republican, supported Taft. The Republican vote was split between Taft, the party's official candidate, and Roosevelt, running under the label of the Progressive Party. This allowed the Democratic candidate, New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, to be elected.

U.S. Senator

Election of 1914

Congressman Theodore Burton had been elected as senator by the state legislature in Foraker's place in 1909, and announced that he would seek a second term in the 1914 elections. By this time, the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution had been ratified, giving the people the right to elect senators, and Ohio had instituted primary elections for the office. Foraker and former congressman Ralph D. Cole also entered the Republican primary. When Burton withdrew, Foraker became the favorite, but his Old Guard Republicanism was deemed outdated, and Harding was urged to enter the race. Daugherty claimed credit for persuading Harding to run: "I found him like a turtle sunning himself on a log, and I pushed him into the water." According to Harding biographer Randolph Downes, "he put on a campaign of such sweetness and light as would have won the plaudits of the angels. It was calculated to offend nobody except Democrats." Although Harding did not attack Foraker, his supporters had no such scruples. Harding won the primary by 12,000 votes over Foraker.

Harding's general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

opponent was Ohio Attorney General Timothy Hogan, who had risen to statewide office despite widespread prejudice against Roman Catholics in rural areas. In 1914, the start of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the prospect of a Catholic senator from Ohio increased nativist sentiment. Propaganda sheets with names like ''The Menace'' and ''The Defender'' contained warnings that Hogan was the vanguard in a plot led by Pope Benedict XV through the Knights of Columbus to control Ohio. Harding did not attack Hogan (an old friend) on this or most other issues, but he did not denounce the nativist hatred for his opponent.

Harding's conciliatory campaigning style aided him; one Harding friend deemed the candidate's stump speech during the 1914 fall campaign as "a rambling, high-sounding mixture of platitudes, patriotism, and pure nonsense". Dean notes, "Harding used his oratory to good effect; it got him elected, making as few enemies as possible in the process." Harding won by over 100,000 votes in a landslide that also swept into office a Republican governor, Frank B. Willis.

Junior senator

When Harding joined the U.S. Senate, the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, and were led by President Wilson. As a junior senator in the minority, Harding received unimportant committee assignments, but carried out those duties assiduously. He was a safe, conservative, Republican vote. As during his time in the Ohio Senate, Harding came to be widely liked.

On two issues, women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

, and the prohibition of alcohol, where picking the wrong side would have damaged his presidential prospects in 1920, he prospered by taking nuanced positions. As senator-elect, he indicated that he could not support votes for women until Ohio did. Increased support for suffrage there and among Senate Republicans meant that by the time Congress voted on the issue, Harding was a firm supporter. Harding, who drank, initially voted against banning alcohol. He voted for the Eighteenth Amendment, which imposed prohibition, after successfully moving to modify it by placing a time limit on ratification, which was expected to kill it. Once it was ratified anyway, Harding voted to override Wilson's veto of the Volstead Bill, which implemented the amendment, assuring the support of the Anti-Saloon League.

Harding, as a politician respected by both Republicans and Progressives, was asked to be temporary chairman of the 1916 Republican National Convention and to deliver the keynote address. He urged delegates to stand as a united party. The convention nominated Justice Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. Harding reached out to Roosevelt once the former president declined the 1916 Progressive nomination, a refusal that effectively scuttled that party. In the November 1916 presidential election, despite increasing Republican unity, Hughes was narrowly defeated by Wilson.

Harding spoke and voted in favor of the resolution of war requested by Wilson in April 1917 that plunged the United States into World War I. In August, Harding argued for giving Wilson almost dictatorial powers, stating that democracy had little place in time of war. Harding voted for most war legislation, including the Espionage Act of 1917, which restricted civil liberties, though he opposed the excess profits tax as anti-business. In May 1918, Harding, less enthusiastic about Wilson, opposed a bill to expand the president's powers.

In the 1918 midterm congressional elections, held just before the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

, Republicans narrowly took control of the Senate. Harding was appointed to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Wilson took no senators with him to the Paris Peace Conference, confident that he could force what became the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

through the Senate by appealing to the people. When he returned with a single treaty establishing both peace and a League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

, the country was overwhelmingly on his side. Many senators disliked Article X of the League Covenant, that committed signatories to the defense of any member nation that was attacked, seeing it as forcing the United States to war without the assent of Congress. Harding was one of 39 senators who signed a round-robin letter opposing the League. When Wilson invited the Foreign Relations Committee to the White House to informally discuss the treaty, Harding ably questioned Wilson about Article X; the president evaded his inquiries. The Senate debated Versailles in September 1919, and Harding made a major speech against it. By then, Wilson had suffered a stroke while on a speaking tour. With an incapacitated president in the White House and less support in the country, the treaty was defeated.

Presidential election of 1920

Primary campaign

With most Progressives having rejoined the Republican Party, their former leader, Theodore Roosevelt, was deemed likely to make a third run for the White House in 1920, and was the overwhelming favorite for the Republican nomination. These plans ended when Roosevelt suddenly died on January 6, 1919. A number of candidates quickly emerged, including General Leonard Wood, Illinois Governor Frank Lowden, California Senator Hiram Johnson

Hiram Warren Johnson (September 2, 1866August 6, 1945) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 23rd governor of California from 1911 to 1917 and represented California in the U.S. Senate for five terms from 1917 to 1945. Johns ...

, and a host of relatively minor possibilities such as Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

(renowned for his World War I relief work), Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

, and General John J. Pershing.

Harding, while he wanted to be president, was as much motivated in entering the race by his desire to keep control of Ohio Republican politics, enabling his re-election to the Senate in 1920. Among those coveting Harding's seat were former governor Willis (he had been defeated by James M. Cox in 1916) and Colonel William Cooper Procter (head of Procter & Gamble

The Procter & Gamble Company (P&G) is an American multinational consumer goods corporation headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was founded in 1837 by William Procter and James Gamble. It specializes in a wide range of personal health/con ...

). On December 17, 1919, Harding made a low-key announcement of his presidential candidacy. Leading Republicans disliked Wood and Johnson, both of the progressive faction of the party, and Lowden, who had an independent streak, was deemed little better. Harding was far more acceptable to the "Old Guard" leaders of the party.

Daugherty, who became Harding's campaign manager, was sure none of the other candidates could garner a majority. His strategy was to make Harding an acceptable choice to delegates once the leaders faltered. Daugherty established a "Harding for President" campaign office in Washington (run by his confidant, Jess Smith), and worked to manage a network of Harding friends and supporters, including Frank Scobey of Texas (clerk of the Ohio State Senate during Harding's years there). Harding worked to shore up his support through incessant letter-writing. Despite the candidate's work, according to Russell, "without Daugherty's Mephistophelean efforts, Harding would never have stumbled forward to the nomination."

There were only 16 presidential primary states in 1920, of which the most crucial to Harding was Ohio. Harding had to have some loyalists at the convention to have any chance of nomination, and the Wood campaign hoped to knock Harding out of the race by taking Ohio. Wood campaigned in the state, and his supporter, Procter, spent large sums; Harding spoke in the non-confrontational style he had adopted in 1914. Harding and Daugherty were so confident of sweeping Ohio's 48 delegates that the candidate went on to the next state, Indiana, before the April 27 Ohio primary. Harding carried Ohio by only 15,000 votes over Wood, taking less than half the total vote, and won only 39 of 48 delegates. In Indiana, Harding finished fourth, with less than ten percent of the vote, and failed to win a single delegate. He was willing to give up and have Daugherty file his re-election papers for the Senate, but Florence Harding grabbed the phone from his hand, "Warren Harding, what are you doing? Give up? Not until the convention is over. Think of your friends in Ohio!" On learning that Daugherty had left the phone line, the future First Lady retorted, "Well, you tell Harry Daugherty for me that we're in this fight until Hell freezes over."

After he recovered from the shock of the poor results, Harding traveled to Boston, where he delivered a speech that according to Dean, "would resonate throughout the 1920 campaign and history." There, he said that "America's present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration." Dean notes, "Harding, more than the other aspirants, was reading the nation's pulse correctly."

Convention

The 1920 Republican National Convention opened at the Chicago Coliseum on June 8, 1920, assembling delegates who were bitterly divided, most recently over the results of a Senate investigation into campaign spending, which had just been released. That report found that Wood had spent $1.8 million (equivalent to $ million in ), lending substance to Johnson's claims that Wood was trying to buy the presidency. Some of the $600,000 that Lowden had spent had wound up in the pockets of two convention delegates. Johnson had spent $194,000, and Harding $113,000. Johnson was deemed to be behind the inquiry, and the rage of the Lowden and Wood factions put an end to any possible compromise among the frontrunners. Of the almost 1,000 delegates, 27 were women—the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, guaranteeing women the vote, was within one state of ratification, and would pass before the end of August. The convention had no boss, most uninstructed delegates voted as they pleased, and with a Democrat in the White House, the party's leaders could not use patronage to get their way.

Reporters deemed Harding unlikely to be nominated due to his poor showing in the primaries, and relegated him to a place among the dark horses. Harding, who like the other candidates was in Chicago supervising his campaign, had finished sixth in the final public opinion poll, behind the three main candidates as well as former Justice Hughes and Herbert Hoover, and only slightly ahead of Coolidge.

After the convention dealt with other matters, the nominations for president opened on the morning of Friday, June 11. Harding had asked Willis to place his name in nomination, and the former governor responded with a speech popular among the delegates, both for its folksiness and for its brevity in the intense Chicago heat. Reporter Mark Sullivan, who was present, called it a splendid combination of "oratory, grand opera, and hog calling." Willis confided, leaning over the podium railing, "Say, boys—and girls too—why not name Warren Harding?" The laughter and applause that followed created a warm feeling for Harding.

Four ballots were taken on the afternoon of June 11, and they revealed a deadlock. With 493 votes needed to nominate, Wood was the closest with 314; Lowden had 289. The best Harding had done was 65. Chairman Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, the Senate Majority Leader, adjourned the convention about 7 p.m.

The night of June 11–12, 1920 would become famous in political history as the night of the " smoke-filled room", in which, legend has it, party elders agreed to force the convention to nominate Harding. Historians have focused on the session held in the suite of Republican National Committee (RNC) Chairman Will Hays at the Blackstone Hotel, at which senators and others came and went, and numerous possible candidates were discussed. Utah Senator Reed Smoot, before his departure early in the evening, backed Harding, telling Hays and the others that as the Democrats were likely to nominate Governor Cox, they should pick Harding to win Ohio. Smoot also told ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' that there had been an agreement to nominate Harding, but that it would not be done for several ballots yet. This was not true: a number of participants backed Harding (others supported his rivals), but there was no pact to nominate him, and the senators had little power to enforce any agreement. Two other participants in the smoke-filled room discussions, Kansas Senator Charles Curtis and Colonel George Brinton McClellan Harvey, a close friend of Hays, predicted to the press that Harding would be nominated because of the liabilities of the other candidates.

Headlines in the morning newspapers suggested intrigue. Historian Wesley M. Bagby wrote, "Various groups actually worked along separate lines to bring about the nomination—without combination and with very little contact." Bagby said that the key factor in Harding's nomination was his wide popularity among the rank and file of the delegates.

The reassembled delegates had heard rumors that Harding was the choice of a cabal of senators. Although this was not true, delegates believed it, and sought a way out by voting for Harding. When balloting resumed on the morning of June 12, Harding gained votes on each of the next four ballots, rising to 133 as the two front runners saw little change. Lodge then declared a three-hour recess, to the outrage of Daugherty, who raced to the podium, and confronted him, "You cannot defeat this man this way! The motion was not carried! You cannot defeat this man!" Lodge and others used the break to try to stop the Harding momentum and make RNC Chairman Hays the nominee, a scheme Hays refused to have anything to do with. The ninth ballot, after some initial suspense, saw delegation after delegation break for Harding, who took the lead with 374 votes to 249 for Wood and 121 for Lowden (Johnson had 83). Lowden released his delegates to Harding, and the tenth ballot, held at 6 p.m., was a mere formality, with Harding finishing with 672 votes to 156 for Wood. The nomination was made unanimous. The delegates, desperate to leave town before they incurred more hotel expenses, then proceeded to the vice presidential nomination. Harding wanted Senator Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin, who was unwilling to run, but before Lenroot's name could be withdrawn and another candidate decided on, Oregon delegate Wallace McCamant proposed Governor Coolidge and received a roar of approval. Coolidge, popular for his role in breaking the Boston police strike of 1919, was nominated for vice president, receiving two and a fraction votes more than Harding had. James Morgan wrote in ''The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe,'' also known locally as ''the Globe'', is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes. ''The Boston Globe'' is the oldest and largest daily new ...

'': "The delegates would not listen to remaining in Chicago over Sunday ... the President makers did not have a clean shirt. On such things, Rollo, turns the destiny of nations."

General election campaign

The Harding/Coolidge ticket was quickly backed by Republican newspapers, but those of other viewpoints expressed disappointment. The '' New York World'' found Harding the least-qualified candidate since

The Harding/Coolidge ticket was quickly backed by Republican newspapers, but those of other viewpoints expressed disappointment. The '' New York World'' found Harding the least-qualified candidate since James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, deeming the Ohio senator a "weak and mediocre" man who "never had an original idea." The Hearst newspapers called Harding "the flag-bearer of a new Senatorial autocracy." ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' described the Republican presidential candidate as "a very respectable Ohio politician of the second class."

The Democratic National Convention opened in San Francisco on June 28, 1920, under a shadow cast by Woodrow Wilson, who wished to be nominated for a third term. Delegates were convinced Wilson's health would not permit him to serve, and looked elsewhere for a candidate. Former Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo was a major contender, but he was Wilson's son-in-law, and refused to consider a nomination so long as the president wanted it. Many at the convention voted for McAdoo anyway, and a deadlock ensued with Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. On the 44th ballot, the Democrats nominated Governor Cox for president, with his running mate Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. As Cox was a newspaper owner and editor, this placed two Ohio editors against each other for the presidency, and some complained there was no real political choice as both Cox and Harding were seen as economic conservatives. But ideologically, the candidates were distinctly different, with Cox a liberal and Harding a conservative.

Harding elected to conduct a front porch campaign, like McKinley in 1896. Some years earlier, Harding had had his front porch remodeled to resemble McKinley's, which his neighbors felt signified presidential ambitions. The candidate remained at home in Marion, and gave addresses to visiting delegations. In the meantime, Cox and Roosevelt stumped the nation, giving hundreds of speeches. Coolidge spoke in the Northeast, later on in the South, and was not a significant factor in the election.

In Marion, Harding ran his campaign. As a newspaperman himself, he fell into easy camaraderie with the press covering him, enjoying a relationship few presidents have equaled. His " return to normalcy" theme was aided by the atmosphere that Marion provided, an orderly place that induced nostalgia in many voters. The front porch campaign allowed Harding to avoid mistakes, and as time dwindled towards the election, his strength grew. The travels of the Democratic candidates eventually caused Harding to make several short speaking tours, but for the most part, he remained in Marion. The United States had no need for another Wilson, Harding argued, appealing for a president "near the normal".

Harding elected to conduct a front porch campaign, like McKinley in 1896. Some years earlier, Harding had had his front porch remodeled to resemble McKinley's, which his neighbors felt signified presidential ambitions. The candidate remained at home in Marion, and gave addresses to visiting delegations. In the meantime, Cox and Roosevelt stumped the nation, giving hundreds of speeches. Coolidge spoke in the Northeast, later on in the South, and was not a significant factor in the election.

In Marion, Harding ran his campaign. As a newspaperman himself, he fell into easy camaraderie with the press covering him, enjoying a relationship few presidents have equaled. His " return to normalcy" theme was aided by the atmosphere that Marion provided, an orderly place that induced nostalgia in many voters. The front porch campaign allowed Harding to avoid mistakes, and as time dwindled towards the election, his strength grew. The travels of the Democratic candidates eventually caused Harding to make several short speaking tours, but for the most part, he remained in Marion. The United States had no need for another Wilson, Harding argued, appealing for a president "near the normal".

Harding's vague oratory irritated some; McAdoo described a typical Harding speech as "an army of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea. Sometimes these meandering words actually capture a straggling thought and bear it triumphantly, a prisoner in their midst, until it died of servitude and over work." H. L. Mencken concurred, "it reminds me of a string of wet sponges, it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights. It is so bad that a kind of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm ... of pish, and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of tosh. It is rumble and bumble. It is balder and dash." ''The New York Times'' took a more positive view of Harding's speeches, writing that in them the majority of people could find "a reflection of their own indeterminate thoughts."

Wilson had said that the 1920 election would be a "great and solemn referendum" on the League of Nations, making it difficult for Cox to maneuver on the issue—although Roosevelt strongly supported the League, Cox was less enthusiastic. Harding opposed entry into the League of Nations as negotiated by Wilson, but favored an "association of nations,"

Harding's vague oratory irritated some; McAdoo described a typical Harding speech as "an army of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea. Sometimes these meandering words actually capture a straggling thought and bear it triumphantly, a prisoner in their midst, until it died of servitude and over work." H. L. Mencken concurred, "it reminds me of a string of wet sponges, it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights. It is so bad that a kind of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm ... of pish, and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of tosh. It is rumble and bumble. It is balder and dash." ''The New York Times'' took a more positive view of Harding's speeches, writing that in them the majority of people could find "a reflection of their own indeterminate thoughts."

Wilson had said that the 1920 election would be a "great and solemn referendum" on the League of Nations, making it difficult for Cox to maneuver on the issue—although Roosevelt strongly supported the League, Cox was less enthusiastic. Harding opposed entry into the League of Nations as negotiated by Wilson, but favored an "association of nations,"The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

. This was general enough to satisfy most Republicans, and only a few bolted the party over this issue. By October, Cox had realized there was widespread public opposition to Article X, and said that reservations to the treaty might be necessary; this shift allowed Harding to say no more on the subject.

The RNC hired Albert Lasker

Albert Davis Lasker (May 1, 1880 – May 30, 1952) was an American businessman who played a major role in shaping modern advertising. He was raised in Galveston, Texas, where his father was the president of several banks. Moving to Chicago, he b ...

, an advertising executive from Chicago, to publicize Harding, and Lasker unleashed a broad-based advertising campaign that used many now-standard advertising techniques for the first time in a presidential campaign. Lasker's approach included newsreels and sound recordings. Visitors to Marion had their photographs taken with Senator and Mrs. Harding, and copies were sent to their hometown newspapers. Billboard posters, newspapers and magazines were employed in addition to motion pictures. Telemarketers were used to make phone calls with scripted dialogues to promote Harding.

During the campaign, opponents spread old rumors that Harding's great-great-grandfather was a West Indian black person and that other blacks might be found in his family tree. Harding's campaign manager rejected the accusations. Wooster College professor William Estabrook Chancellor publicized the rumors, based on supposed family research, but perhaps reflecting no more than local gossip.

By Election Day, November 2, 1920, few had any doubts that the Republican ticket would win. Harding received 60.2 percent of the popular vote, the highest percentage since the evolution of the

By Election Day, November 2, 1920, few had any doubts that the Republican ticket would win. Harding received 60.2 percent of the popular vote, the highest percentage since the evolution of the two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually referr ...

, and 404 electoral votes. Cox received 34 percent of the national vote and 127 electoral votes. Campaigning from a federal prison where he was serving a sentence for opposing the war, Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

Eugene V. Debs received 3 percent of the national vote. The Republicans greatly increased their majority in each house of Congress.

Presidency (1921–1923)

Inauguration and appointments

Harding was inaugurated on March 4, 1921, in the presence of his wife and father. Harding preferred a subdued inauguration without the customary parade, leaving only the actual ceremony and a brief reception at the White House. In his inaugural address, he declared, "Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it."

After the election, Harding announced that no decisions about appointments would be made until he returned from a vacation in December. He traveled to Texas, where he fished and played golf with his friend Frank Scobey (soon to be director of the Mint) and then sailed for the

Harding was inaugurated on March 4, 1921, in the presence of his wife and father. Harding preferred a subdued inauguration without the customary parade, leaving only the actual ceremony and a brief reception at the White House. In his inaugural address, he declared, "Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it."

After the election, Harding announced that no decisions about appointments would be made until he returned from a vacation in December. He traveled to Texas, where he fished and played golf with his friend Frank Scobey (soon to be director of the Mint) and then sailed for the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a International zone#Concessions, concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area gene ...

. He visited Washington when Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

opened in early December, and he was afforded a hero's welcome as the first sitting senator to be elected to the White House. Back in Ohio, Harding planned to consult with the country's best minds, who visited Marion to offer their counsel regarding appointments.

Harding chose pro-League Charles Evans Hughes as Secretary of State, ignoring the advice of Senator Lodge and others. After Charles G. Dawes declined the Treasury position, he chose Pittsburgh banker Andrew W. Mellon, one of the richest people in the country. He appointed Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce. RNC chairman Will Hays was made Postmaster General, then a cabinet post; he left after a year in the position to become chief censor to the motion-picture industry.

The two Harding cabinet appointees who darkened the reputation of his administration by their involvement in scandal were Harding's Senate friend Albert B. Fall of New Mexico, the Interior Secretary, and Daugherty, the attorney general. Fall was a Western rancher and former miner who favored development. He was opposed by conservationists such as Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsyl ...

, who wrote, "it would have been possible to pick a worse man for Secretary of the Interior, but not altogether easy." ''The New York Times'' mocked the Daugherty appointment, writing that rather than selecting one of the best minds, Harding had been content "to choose merely a best friend." Eugene P. Trani and David L. Wilson, in their volume on Harding's presidency, suggest that the appointment made sense then, as Daugherty was "a competent lawyer well-acquainted with the seamy side of politics ... a first-class political troubleshooter and someone Harding could trust."

Foreign policy

European relations and formally ending the war

Harding made it clear when he appointed Hughes as Secretary of State that the former justice would run foreign policy, a change from Wilson's hands-on management of international affairs. Hughes had to work within some broad outlines; after taking office, Harding hardened his stance on the League of Nations, deciding the U.S. would not join even a scaled-down version of the League. With the Treaty of Versailles unratified by the Senate, the U.S. remained technically at war with Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

. Peacemaking began with the Knox–Porter Resolution, declaring the U.S. at peace and reserving any rights granted under Versailles. Treaties with Germany, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, each containing many of the non-League provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, were ratified in 1921.

This still left the question of relations between the U.S. and the League. Hughes' State Department initially ignored communications from the League, or tried to bypass it through direct contacts with member nations. By 1922, though, the U.S., through its consul in Geneva, was dealing with the League, and though the U.S. refused to participate in any meeting with political implications, it sent observers to sessions on technical and humanitarian matters.

By the time Harding took office, there were calls from foreign governments for reduction of the massive war debt owed to the United States, and the German government sought to reduce the reparations that it was required to pay. The U.S. refused to consider any multilateral settlement. Harding sought passage of a plan proposed by Mellon to give the administration broad authority to reduce war debts in negotiation, but Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, in 1922, passed a more restrictive bill. Hughes negotiated an agreement for Britain to pay off its war debt over 62 years at low interest, reducing the present value

In economics and finance, present value (PV), also known as present discounted value (PDV), is the value of an expected income stream determined as of the date of valuation. The present value is usually less than the future value because money ha ...

of the obligations. This agreement, approved by Congress in 1923, served as a model for negotiations with other nations. Talks with Germany on reduction of reparations payments resulted in the Dawes Plan of 1924.

A pressing issue not resolved by Wilson was U.S. policy towards Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

Russia. The U.S. had been among the nations that sent troops there after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

. Afterwards, Wilson refused to recognize the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

. Harding's Commerce Secretary Hoover, with considerable experience in Russian affairs, took the lead on policy. When famine struck Russia in 1921, Hoover had the American Relief Administration

American Relief Administration (ARA) was an American Humanitarian aid, relief mission to Europe and later Russian Civil War, post-revolutionary Russia after World War I. Herbert Hoover, future president of the United States, was the program dire ...

, which he had headed, negotiate with the Russians to provide aid. Leaders of the U.S.S.R. (established in 1922) hoped in vain that the agreement would lead to recognition. Hoover supported trade with the Soviets, fearing U.S. companies would be frozen out of the Soviet market, but Hughes opposed this, and the matter was not resolved under Harding's presidency.

Disarmament

Harding urged disarmament and lower defense costs during the campaign, but it had not been a major issue. He gave a speech to a joint session of Congress in April 1921, setting out his legislative priorities. Among the few foreign policy matters he mentioned was disarmament; he said the government could not "be unmindful of the call for reduced expenditure" on defense.

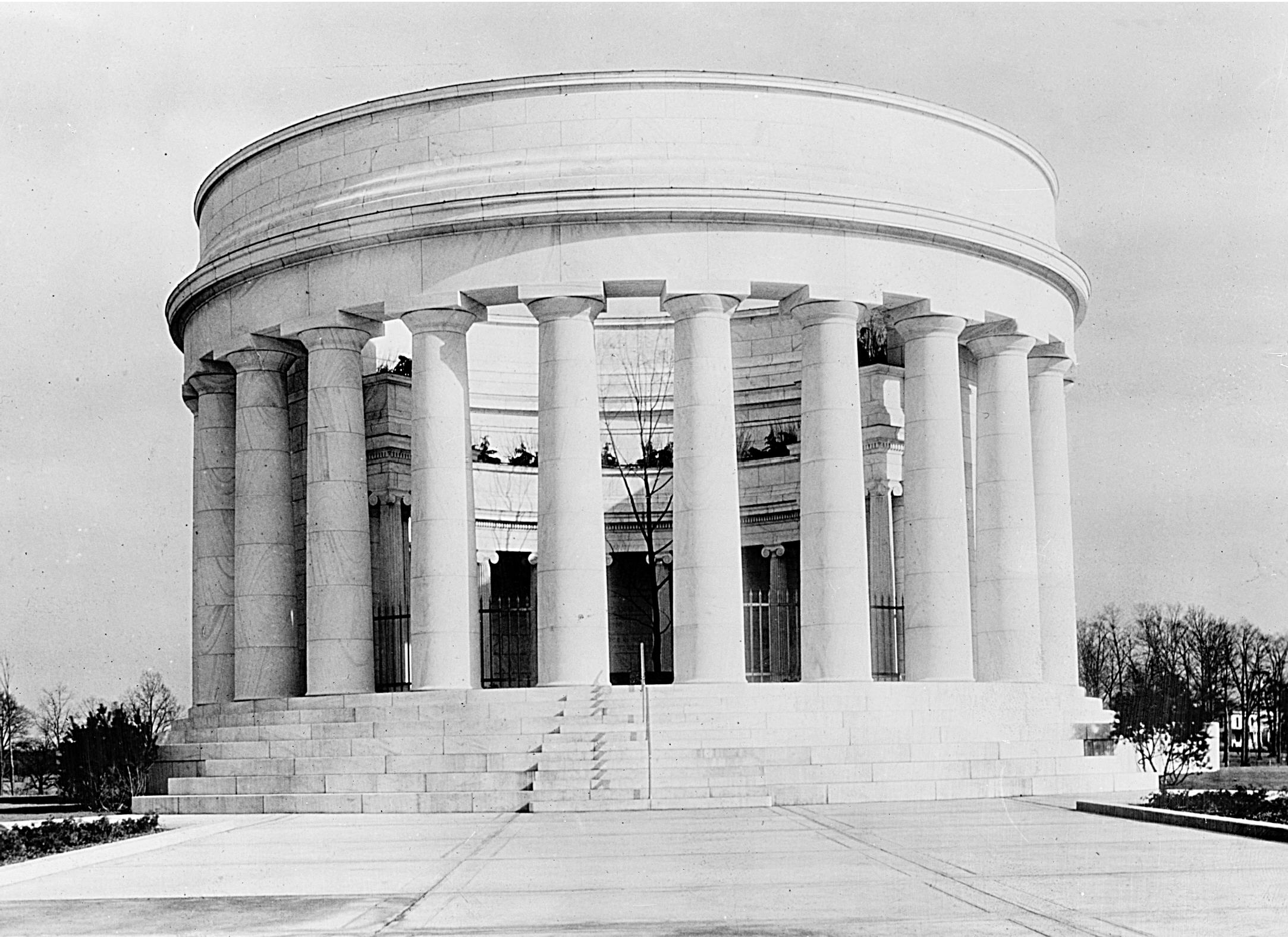

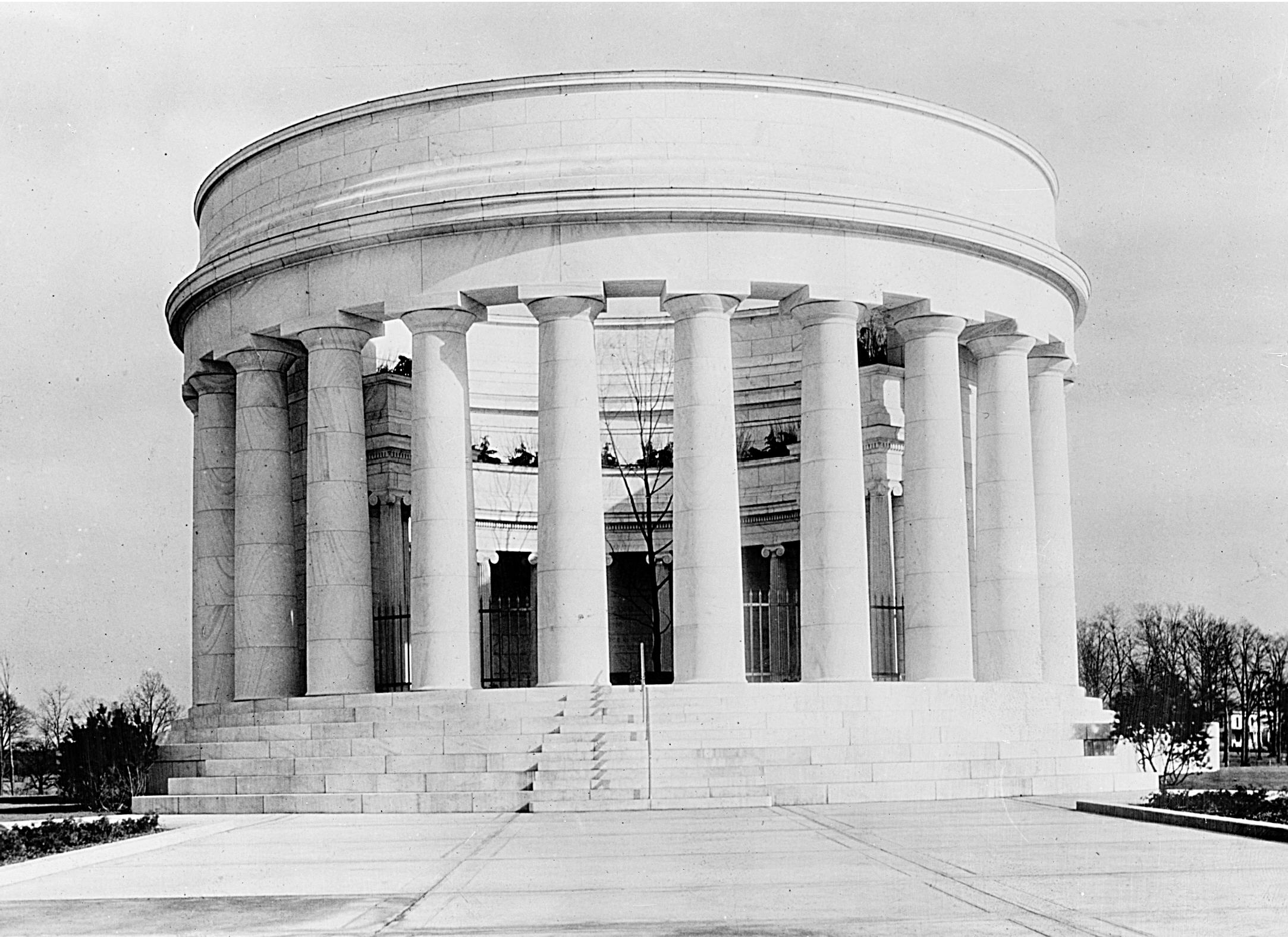

Idaho Senator William Borah had proposed a conference at which the major naval powers, the U.S., Britain, and Japan, would agree to cuts in their fleets. Harding concurred, and after diplomatic discussions, representatives of nine nations convened in Washington in November 1921. Most of the diplomats first attended Armistice Day ceremonies at

Harding urged disarmament and lower defense costs during the campaign, but it had not been a major issue. He gave a speech to a joint session of Congress in April 1921, setting out his legislative priorities. Among the few foreign policy matters he mentioned was disarmament; he said the government could not "be unmindful of the call for reduced expenditure" on defense.

Idaho Senator William Borah had proposed a conference at which the major naval powers, the U.S., Britain, and Japan, would agree to cuts in their fleets. Harding concurred, and after diplomatic discussions, representatives of nine nations convened in Washington in November 1921. Most of the diplomats first attended Armistice Day ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

, where Harding spoke at the entombment of the Unknown Soldier of World War I, whose identity, "took flight with his imperishable soul. We know not whence he came, only that his death marks him with the everlasting glory of an American dying for his country."

Hughes, in his speech at the opening session of the conference on November 12, 1921, made the American proposal—the U.S. would decommission or not build 30 warships if Great Britain did likewise for 19 vessels, and Japan for 17. Hughes was generally successful, with agreements reached on this and other points, including settlement of disputes over islands in the Pacific, and limitations on the use of poison gas. The naval agreement applied only to battleships, and to some extent aircraft carriers, and ultimately did not prevent rearmament. Nevertheless, Harding and Hughes were widely applauded in the press for their work. Senator Lodge and the Senate Minority Leader, Alabama's Oscar Underwood

Oscar Wilder Underwood (May 6, 1862 – January 25, 1929) was an United States of America, American lawyer and politician from Alabama, and also a candidate for President of the United States in 1912 and 1924. He was the first formally designa ...

, were part of the U.S. delegation, and they helped ensure the treaties made it through the Senate mostly unscathed, though that body added reservations to some.

The U.S. had acquired over a thousand vessels during World War I, and still owned most of them when Harding took office. Congress had authorized their disposal in 1920, but the Senate would not confirm Wilson's nominees to the Shipping Board. Harding appointed Albert Lasker as its chairman; the advertising executive undertook to run the fleet as profitably as possible until it could be sold. Few ships were marketable at anything approaching the government's cost. Lasker recommended a large subsidy to the merchant marine to facilitate sales, and Harding repeatedly urged Congress to enact it. The resulting bill was unpopular in the Midwest, and though it passed the House, it was defeated by a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

in the Senate, and most government ships were eventually scrapped.

Latin America

Intervention in Latin America had been a minor campaign issue, though Harding spoke against Wilson's decision to send U.S. troops to the Dominican Republic and Haiti, and attacked the Democratic vice presidential candidate, Franklin Roosevelt, for his role in the Haitian intervention. Once Harding was sworn in, Hughes worked to improve relations with Latin American countries who were wary of the American use of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

to justify intervention; at the time of Harding's inauguration, the U.S. also had troops in Cuba and Nicaragua. The troops stationed in Cuba were withdrawn in 1921, but U.S. forces remained in the other three nations throughout Harding's presidency. In April 1921, Harding gained the ratification of the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty with Colombia, granting that nation $25 million (equivalent to $ million in ) as settlement for the U.S.-provoked Panamanian revolution of 1903. The Latin American nations were not fully satisfied, as the U.S. refused to renounce interventionism, though Hughes pledged to limit it to nations near the Panama Canal, and to make it clear what the U.S. aims were.

The U.S. had intervened repeatedly in Mexico under Wilson, and had withdrawn diplomatic recognition, setting conditions for reinstatement. The Mexican government under President Álvaro Obregón wanted recognition before negotiations, but Wilson and his final Secretary of State, Bainbridge Colby, refused. Both Hughes and Fall opposed recognition; Hughes instead sent a draft treaty to the Mexicans in May 1921, which included pledges to reimburse Americans for losses in Mexico since the 1910 revolution there. Obregón was unwilling to sign a treaty before being recognized, and worked to improve the relationship between American business and Mexico, reaching agreement with creditors, and mounting a public relations campaign in the United States. This had its effect, and by mid-1922, Fall was less influential than he had been, lessening the resistance to recognition. The two presidents appointed commissioners to reach a deal, and the U.S. recognized the Obregón government on August 31, 1923, just under a month after Harding's death, substantially on the terms proffered by Mexico.

Domestic policy

Postwar recession and recovery

When Harding took office on March 4, 1921, the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline. At the suggestion of legislative leaders, Harding called a special session of Congress, to convene April 11. When Harding addressed the joint session the following day, he urged the reduction of income taxes (raised during the war), an increase in tariffs on agricultural goods to protect the American farmer, as well as more wide-ranging reforms, such as support for highways, aviation, and radio. It was not until May 27 that Congress passed an emergency tariff increase on agricultural products. An act authorizing a Bureau of the Budget followed on June 10, and Harding appointed Charles Dawes as bureau director with a mandate to cut expenditures.

Mellon's tax cuts

Treasury Secretary Mellon also recommended that Congress cut income tax rates, and that the corporate excess profits tax be abolished. The House Ways and Means Committee endorsed Mellon's proposals, but some congressmen wanting to raise corporate tax rates fought the measure. Harding was unsure what side to endorse, telling a friend, "I can't make a damn thing out of this tax problem. I listen to one side, and they seem right, and then—God!—I talk to the other side, and they seem just as right." Harding tried compromise, and gained passage of a bill in the House after the end of the excess profits tax was delayed a year. In the Senate, the bill became entangled in efforts to vote World War I veterans a soldier's bonus. Frustrated by the delays, on July 12, Harding appeared before the Senate to urge passage of the tax legislation without the bonus. It was not until November that the revenue bill finally passed, with higher rates than Mellon had proposed.

In opposing the veterans' bonus, Harding argued in his Senate address that much was already being done for them by a grateful nation, and that the bill would "break down our Treasury, from which so much is later on to be expected". The Senate sent the bonus bill back to committee, but the issue returned when Congress reconvened in December 1921. A bill providing a bonus, though unfunded, was passed by both houses in September 1922, but Harding's veto was narrowly sustained. A non-cash bonus for soldiers passed over Coolidge's veto in 1924.

In his first annual message to Congress, Harding sought the power to adjust tariff rates. The passage of the tariff bill in the Senate, and in conference committee became a feeding frenzy of lobby interests. When Harding signed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act on September 21, 1922, he made a brief statement, praising the bill only for giving him some power to change rates. According to Trani and Wilson, the bill was "ill-considered. It wrought havoc in international commerce and made the repayment of war debts more difficult."

Mellon ordered a study that demonstrated historically that, as income tax rates were increased, money was driven underground or abroad, and he concluded that lower rates would increase tax revenues. Based on his advice, Harding's revenue bill cut taxes, starting in 1922. The top marginal rate was reduced annually in four stages from 73% in 1921 to 25% in 1925. Taxes were cut for lower incomes starting in 1923, and the lower rates substantially increased the money flowing to the treasury. They also pushed massive deregulation, and federal spending as a share of GDP fell from 6.5% to 3.5%. By late 1922, the economy began to turn around. Unemployment was pared from its 1921 high of 12% to an average of 3.3% for the remainder of the decade. The misery index, a combined measure of unemployment and inflation, had its sharpest decline in U.S. history under Harding. Wages, profits, and productivity all made substantial gains; annual GDP increases averaged at over 5% during the 1920s. Libertarian historians Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen argue that, "Mellon's tax policies set the stage for the most amazing growth yet seen in America's already impressive economy."