Walt Disney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film producer, he holds the record for most Academy Awards earned and nominations by an individual, having won 22 Oscars from 59 nominations. He was presented with two Golden Globe Special Achievement Awards and an Emmy Award, among other honors. Several of his films are included in the

Disney was born on December 5, 1901, at 1249 Tripp Avenue, in Chicago's Hermosa neighborhood. He was the fourth son of Elias Disneyborn in the

Disney was born on December 5, 1901, at 1249 Tripp Avenue, in Chicago's Hermosa neighborhood. He was the fourth son of Elias Disneyborn in the

In January 1920, as Pesmen-Rubin's revenue declined after Christmas, Disney, aged 18, and Iwerks were laid off. They started their own business, the short-lived Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists. Failing to attract many customers, Disney and Iwerks agreed that Disney should leave temporarily to earn money at the Kansas City Film Ad Company, run by A. V. Cauger; the following month Iwerks, who was not able to run their business alone, also joined. The company produced commercials using the

In January 1920, as Pesmen-Rubin's revenue declined after Christmas, Disney, aged 18, and Iwerks were laid off. They started their own business, the short-lived Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists. Failing to attract many customers, Disney and Iwerks agreed that Disney should leave temporarily to earn money at the Kansas City Film Ad Company, run by A. V. Cauger; the following month Iwerks, who was not able to run their business alone, also joined. The company produced commercials using the  In 1926, the first official ''Walt Disney Studio'' was established at 2725 Hyperion Avenue, demolished in 1940.

By 1926, Winkler's role in the distribution of the ''Alice'' series had been handed over to her husband, the film producer Charles Mintz, although the relationship between him and Disney was sometimes strained. The series ran until July 1927, by which time Disney had begun to tire of it and wanted to move away from the mixed format to all animation. After Mintz requested new material to distribute through

In 1926, the first official ''Walt Disney Studio'' was established at 2725 Hyperion Avenue, demolished in 1940.

By 1926, Winkler's role in the distribution of the ''Alice'' series had been handed over to her husband, the film producer Charles Mintz, although the relationship between him and Disney was sometimes strained. The series ran until July 1927, by which time Disney had begun to tire of it and wanted to move away from the mixed format to all animation. After Mintz requested new material to distribute through

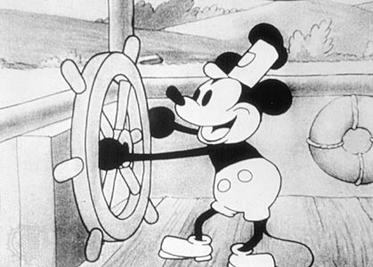

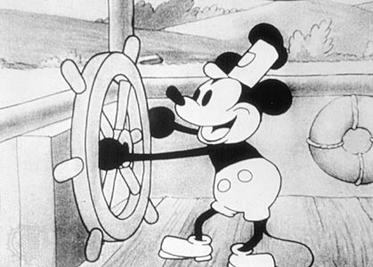

Mickey Mouse first appeared in May 1928 as a single test screening of the short ''

Mickey Mouse first appeared in May 1928 as a single test screening of the short '' With the loss of Powers as distributor, Disney studios signed a contract with

With the loss of Powers as distributor, Disney studios signed a contract with

By 1934, Disney had become dissatisfied with producing formulaic cartoon shorts, and believed a feature-length cartoon would be more profitable. The studio began the four-year production of ''

By 1934, Disney had become dissatisfied with producing formulaic cartoon shorts, and believed a feature-length cartoon would be more profitable. The studio began the four-year production of ''

Shortly after the release of ''Dumbo'' in October 1941, the U.S. entered World War II. Disney formed the Walt Disney Training Films Unit within the company to produce instruction films for the military such as ''Four Methods of Flush Riveting'' and ''Aircraft Production Methods''. Disney also met with Henry Morgenthau Jr., the

Shortly after the release of ''Dumbo'' in October 1941, the U.S. entered World War II. Disney formed the Walt Disney Training Films Unit within the company to produce instruction films for the military such as ''Four Methods of Flush Riveting'' and ''Aircraft Production Methods''. Disney also met with Henry Morgenthau Jr., the

For several years Disney had been considering building a theme park. When he visited

For several years Disney had been considering building a theme park. When he visited  Despite the demands wrought by non-studio projects, Disney continued to work on film and television projects. In 1955, he was involved in "

Despite the demands wrought by non-studio projects, Disney continued to work on film and television projects. In 1955, he was involved in "

Disney had been a heavy smoker since World War I. He did not use cigarettes with

Disney had been a heavy smoker since World War I. He did not use cigarettes with  Disney's plans for the futuristic city of EPCOT did not come to fruition. After Disney's death, his brother Roy deferred his retirement to take full control of the Disney companies. He changed the focus of the project from a town to an attraction. At the inauguration in 1971, Roy dedicated Walt Disney World to his brother. Walt Disney World expanded with the opening of

Disney's plans for the futuristic city of EPCOT did not come to fruition. After Disney's death, his brother Roy deferred his retirement to take full control of the Disney companies. He changed the focus of the project from a town to an attraction. At the inauguration in 1971, Roy dedicated Walt Disney World to his brother. Walt Disney World expanded with the opening of

In 1949, Disney and his family moved to a new home in the

In 1949, Disney and his family moved to a new home in the

Views of Disney and his work have changed over the decades, and there have been polarized opinions. Mark Langer, in the ''American Dictionary of National Biography'', writes that "Earlier evaluations of Disney hailed him as a patriot, folk artist, and popularizer of culture. More recently, Disney has been regarded as a paradigm of

Views of Disney and his work have changed over the decades, and there have been polarized opinions. Mark Langer, in the ''American Dictionary of National Biography'', writes that "Earlier evaluations of Disney hailed him as a patriot, folk artist, and popularizer of culture. More recently, Disney has been regarded as a paradigm of

National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception ...

by the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

and have also been named as some of the greatest films ever by the American Film Institute. Disney was the first person to be nominated for Academy Awards in six different categories.

Born in Chicago in 1901, Disney developed an early interest in drawing. He took art classes as a boy and got a job as a commercial illustrator at the age of 18. He moved to California in the early 1920s and set up the Disney Brothers Studio with his brother Roy

Roy is a masculine given name and a family surname with varied origin.

In Anglo-Norman England, the name derived from the Norman ''roy'', meaning "king", while its Old French cognate, ''rey'' or ''roy'' (modern ''roi''), likewise gave rise to ...

. With Ub Iwerks

Ubbe Ert Iwwerks (March 24, 1901 – July 7, 1971), known as Ub Iwerks ( ), was an American animator, cartoonist, character designer, inventor, and special effects technician. Born in Kansas City, Missouri, Iwerks grew up with a contentiou ...

, he developed the character Mickey Mouse in 1928, his first highly popular success; he also provided the voice for his creation in the early years. As the studio grew, he became more adventurous, introducing synchronized sound, full-color three-strip Technicolor

Technicolor is a series of Color motion picture film, color motion picture processes, the first version dating back to 1916, and followed by improved versions over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black and white films ...

, feature-length

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

cartoons and technical developments in cameras. The results, seen in features such as ''Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

"Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" is a 19th-century German fairy tale that is today known widely across the Western world. The Brothers Grimm published it in 1812 in the first edition of their collection ''Grimms' Fairy Tales'' and numbered as T ...

'' (1937), ''Pinocchio

Pinocchio ( , ) is a fictional character and the protagonist of the children's novel '' The Adventures of Pinocchio'' (1883) by Italian writer Carlo Collodi of Florence, Tuscany. Pinocchio was carved by a woodcarver named Geppetto in a Tuscan ...

'', '' Fantasia'' (both 1940), ''Dumbo

''Dumbo'' is a 1941 American animated fantasy film produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by RKO Radio Pictures. The fourth Disney animated feature film, it is based upon the storyline written by Helen Aberson and Harold Pearl, ...

'' (1941), and ''Bambi

''Bambi'' is a 1942 American animated drama film directed by David Hand (supervising a team of sequence directors), produced by Walt Disney and based on the 1923 book ''Bambi, a Life in the Woods'' by Austrian author and hunter Felix Salten ...

'' (1942), furthered the development of animated film. New animated and live-action film

Live action (or live-action) is a form of cinematography or videography that uses photography instead of animation. Some works combine live-action with animation to create a live-action animated film. Live-action is used to define film, video ga ...

s followed after World War II, including the critically successful ''Cinderella

"Cinderella",; french: link=no, Cendrillon; german: link=no, Aschenputtel) or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsi ...

'' (1950), ''Sleeping Beauty

''Sleeping Beauty'' (french: La belle au bois dormant, or ''The Beauty in the Sleeping Forest''; german: Dornröschen, or ''Little Briar Rose''), also titled in English as ''The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods'', is a fairy tale about a princess cu ...

'' (1959) and '' Mary Poppins'' (1964), the last of which received five Academy Awards.

In the 1950s, Disney expanded into the amusement park industry, and in July 1955 he opened Disneyland

Disneyland is a theme park in Anaheim, California. Opened in 1955, it was the first theme park opened by The Walt Disney Company and the only one designed and constructed under the direct supervision of Walt Disney. Disney initially envision ...

in Anaheim, California

Anaheim ( ) is a city in northern Orange County, California, part of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. As of the 2020 United States Census, the city had a population of 346,824, making it the most populous city in Orange County, the 10th-most ...

. To fund the project he diversified into television programs, such as '' Walt Disney's Disneyland'' and ''The Mickey Mouse Club

''The Mickey Mouse Club'' is an American variety television show that aired intermittently from 1955 to 1996 and returned to social media in 2017. Created by Walt Disney and produced by Walt Disney Productions, the program was first televised ...

''. He was also involved in planning the 1959 Moscow Fair, the 1960 Winter Olympics, and the 1964 New York World's Fair. In 1965, he began development of another theme park, Disney World

The Walt Disney World Resort, also called Walt Disney World or Disney World, is an entertainment resort complex in Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista, Florida, United States, near the cities of Orlando and Kissimmee. Opened on October 1, 1971, th ...

, the heart of which was to be a new type of city, the " Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow" (EPCOT). Disney was a heavy smoker throughout his life and died of lung cancer in December 1966 before either the park or the EPCOT project were completed.

Disney was a shy, self-deprecating and insecure man in private but adopted a warm and outgoing public persona. He had high standards and high expectations of those with whom he worked. Although there have been accusations that he was racist or antisemitic, they have been contradicted by many who knew him. Historiography of Disney has taken a variety of perspectives, ranging from views of him as a purveyor of homely patriotic values to being a representative of American imperialism

American imperialism refers to the expansion of American political, economic, cultural, and media influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conques ...

. He remains an important figure in the history of animation and in the cultural history of the United States, where he is considered a national cultural icon

A cultural icon is a person or an artifact that is identified by members of a culture as representative of that culture. The process of identification is subjective, and "icons" are judged by the extent to which they can be seen as an authentic ...

. His film work continues to be shown and adapted, and the Disney theme parks have grown in size and number to attract visitors in several countries.

Early life

Disney was born on December 5, 1901, at 1249 Tripp Avenue, in Chicago's Hermosa neighborhood. He was the fourth son of Elias Disneyborn in the

Disney was born on December 5, 1901, at 1249 Tripp Avenue, in Chicago's Hermosa neighborhood. He was the fourth son of Elias Disneyborn in the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on th ...

, to Irish parentsand Flora ( Call), an American of German and English descent. Aside from Walt, Elias and Flora's sons were Herbert, Raymond and Roy

Roy is a masculine given name and a family surname with varied origin.

In Anglo-Norman England, the name derived from the Norman ''roy'', meaning "king", while its Old French cognate, ''rey'' or ''roy'' (modern ''roi''), likewise gave rise to ...

; and the couple had a fifth child, Ruth, in December 1903. In 1906, when Disney was four, the family moved to a farm in Marceline, Missouri

Marceline is a city in Chariton and Linn counties in the U.S. state of Missouri. The population was 2,123 at the 2020 census.

History

Marceline was laid out in 1887, and named after the wife of a railroad man. A post office called Marceline h ...

, where his uncle Robert had just purchased land. In Marceline, Disney developed his interest in drawing when he was paid to draw the horse of a retired neighborhood doctor. Elias was a subscriber to the '' Appeal to Reason'' newspaper, and Disney practiced drawing by copying the front-page cartoons of Ryan Walker. He also began to develop an ability to work with watercolors and crayons. He lived near the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway , often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the larger railroads in the United States. The railroad was chartered in February 1859 to serve the cities of Atchison, Kansas, Atchison and Top ...

line and became enamored with trains. He and his younger sister Ruth started school at the same time at the Park School in Marceline in late 1909. The Disney family were active members of a Congregational church.

In 1911, the Disneys moved to Kansas City, Missouri. There, Disney attended the Benton Grammar School, where he met fellow-student Walter Pfeiffer, who came from a family of theatre fans and introduced him to the world of vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

and motion pictures. Before long, Disney was spending more time at the Pfeiffers' house than at home. Elias had purchased a newspaper delivery route for ''The Kansas City Star

''The Kansas City Star'' is a newspaper based in Kansas City, Missouri. Published since 1880, the paper is the recipient of eight Pulitzer Prizes. ''The Star'' is most notable for its influence on the career of President Harry S. Truman and a ...

'' and ''Kansas City Times

The ''Kansas City Times'' was a morning newspaper in Kansas City, Missouri, published from 1867 to 1990. The morning ''Kansas City Times'', under ownership of the afternoon '' Kansas City Star'', won two Pulitzer Prizes and was bigger than its p ...

''. Disney and his brother Roy woke up at 4:30 every morning to deliver the ''Times'' before school and repeated the round for the evening ''Star'' after school. The schedule was exhausting, and Disney often received poor grades after falling asleep in class, but he continued his paper route for more than six years. He attended Saturday courses at the Kansas City Art Institute

The Kansas City Art Institute (KCAI) is a private art school in Kansas City, Missouri. The college was founded in 1885 and is an accredited by the National Association of Schools of Art and Design and Higher Learning Commission. It has approx ...

and also took a correspondence course

Distance education, also known as distance learning, is the education of students who may not always be physically present at a school, or where the learner and the teacher are separated in both time and distance. Traditionally, this usually in ...

in cartooning.

In 1917, Elias bought stock in a Chicago jelly producer, the O-Zell Company, and moved back to the city with his family. Disney enrolled at McKinley High School and became the cartoonist of the school newspaper, drawing patriotic pictures about World War I; he also took night courses at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) is a private art school associated with the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) in Chicago, Illinois. Tracing its history to an art students' cooperative founded in 1866, which grew into the museum an ...

. In mid-1918, he attempted to join the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

to fight the Germans, but he was rejected as too young. After forging the date of birth on his birth certificate, he joined the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

in September 1918 as an ambulance driver. He was shipped to France but arrived in November, after the armistice. He drew cartoons on the side of his ambulance for decoration and had some of his work published in the army newspaper '' Stars and Stripes''. He returned to Kansas City in October 1919, where he worked as an apprentice artist at the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio, where he drew commercial illustrations for advertising, theater programs and catalogs, and befriended fellow artist Ub Iwerks

Ubbe Ert Iwwerks (March 24, 1901 – July 7, 1971), known as Ub Iwerks ( ), was an American animator, cartoonist, character designer, inventor, and special effects technician. Born in Kansas City, Missouri, Iwerks grew up with a contentiou ...

.

Career

Early career: 1920–1928

In January 1920, as Pesmen-Rubin's revenue declined after Christmas, Disney, aged 18, and Iwerks were laid off. They started their own business, the short-lived Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists. Failing to attract many customers, Disney and Iwerks agreed that Disney should leave temporarily to earn money at the Kansas City Film Ad Company, run by A. V. Cauger; the following month Iwerks, who was not able to run their business alone, also joined. The company produced commercials using the

In January 1920, as Pesmen-Rubin's revenue declined after Christmas, Disney, aged 18, and Iwerks were laid off. They started their own business, the short-lived Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists. Failing to attract many customers, Disney and Iwerks agreed that Disney should leave temporarily to earn money at the Kansas City Film Ad Company, run by A. V. Cauger; the following month Iwerks, who was not able to run their business alone, also joined. The company produced commercials using the cutout animation

Cutout animation is a form of stop-motion animation using flat characters, props and backgrounds cut from materials such as paper, card, stiff fabric or photographs. The props would be cut out and used as puppets for stop motion. The world's e ...

technique. Disney became interested in animation, although he preferred drawn cartoons such as ''Mutt and Jeff

''Mutt and Jeff'' was a long-running and widely popular American newspaper comic strip created by cartoonist Bud Fisher in 1907 about "two mismatched tinhorns". It is commonly regarded as the first daily comic strip. The concept of a newspape ...

'' and Max Fleischer

Max Fleischer (born Majer Fleischer ; July 19, 1883 – September 25, 1972) was an American animator, inventor, film director and producer, and studio founder and owner. Born in Kraków, Fleischer immigrated to the United States where he became ...

's ''Out of the Inkwell

''Out of the Inkwell'' is an American major animated series of the silent era produced by Max Fleischer from 1918 to 1929.

History

The series was the result of three short experimental films that Max Fleischer independently produced from 191 ...

''. With the assistance of a borrowed book on animation and a camera, he began experimenting at home. He came to the conclusion that cel animation

Traditional animation (or classical animation, cel animation, or hand-drawn animation) is an animation technique in which each frame is drawn by hand. The technique was the dominant form of animation in cinema until computer animation.

Proc ...

was more promising than the cutout method. Unable to persuade Cauger to try cel

A cel, short for celluloid, is a transparent sheet on which objects are drawn or painted for traditional, hand-drawn animation. Actual celluloid (consisting of cellulose nitrate and camphor) was used during the first half of the 20th century, bu ...

animation at the company, Disney opened a new business with a co-worker from the Film Ad Co, Fred Harman

Fred Charles Harman II (February 9, 1902 - January 2, 1982) was an American cartoonist, best known for his popular ''Red Ryder'' comic strip, which he drew for 25 years, reaching 40 million readers through 750 newspapers. Harman sometimes used th ...

. Their main client was the local Newman Theater, and the short cartoons they produced were sold as "Newman's Laugh-O-Grams". Disney studied Paul Terry's ''Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller believed to have lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to ...

'' as a model, and the first six "Laugh-O-Grams" were modernized fairy tales.

In May 1921, the success of the "Laugh-O-Grams" led to the establishment of Laugh-O-Gram Studio

The Laugh-O-Gram Studio (also called Laugh-O-Gram Studios) was a short-lived film studio located on the second floor of the McConahay Building at 1127 East 31st in Kansas City, Missouri that operated from June 28, 1921 to November 20, 1923. ...

, for which he hired more animators, including Fred Harman's brother Hugh, Rudolf Ising

Rudolf Carl Ising (August 7, 1903 – July 18, 1992) was an American animator best known for collaborating with Hugh Harman to establish the Warner Bros. and MGM Cartoon studios during the early years of the golden age of American animation. I ...

and Iwerks. The Laugh-O-Grams cartoons did not provide enough income to keep the company solvent, so Disney started production of ''Alice's Wonderland

''Alice's Wonderland'' is a 1923 Walt Disney short silent film, produced in Kansas City, Missouri by Laugh-O-Gram Studio. The black-and-white short was the first in a series of Walt Disney's famous ''Alice Comedies'' and had a working title o ...

''based on ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creature ...

''which combined live action with animation; he cast Virginia Davis

Virginia Davis (December 31, 1918 – August 15, 2009) was an American child actress in films. She is best known for working with Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks on the animated short series Alice Comedies, in which she portrayed the protagonist Alic ...

in the title role. The result, a 12-and-a-half-minute, one-reel film, was completed too late to save Laugh-O-Gram Studio, which went into bankruptcy in 1923.

Disney moved to Hollywood in July 1923 at 21 years old. Although New York was the center of the cartoon industry, he was attracted to Los Angeles because his brother Roy was convalescing from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

there, and he hoped to become a live-action film director. Disney's efforts to sell ''Alice's Wonderland'' were in vain until he heard from New York film distributor Margaret J. Winkler

Margaret J. Winkler Mintz (April 22, 1895 – June 21, 1990) was a key figure in silent animation history, having a crucial role to play in the histories of Max and Dave Fleischer, Pat Sullivan, Otto Messmer, and Walt Disney. She was the fir ...

. She was losing the rights to both the ''Out of the Inkwell'' and ''Felix the Cat

Felix the Cat is a cartoon character created in 1919 by Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer during the silent film era. An anthropomorphic black cat with white eyes, a black body, and a giant grin, he was one of the most recognized cartoon characte ...

'' cartoons, and needed a new series. In October, they signed a contract for six ''Alice'' comedies, with an option for two further series of six episodes each. Disney and his brother Roy formed the Disney Brothers Studiowhich later became The Walt Disney Company

The Walt Disney Company, commonly known as Disney (), is an American multinational mass media and entertainment industry, entertainment conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios (Burbank), Walt Disney Stud ...

to produce the films; they persuaded Davis and her family to relocate to Hollywood to continue production, with Davis on contract at $100 a month. In July 1924, Disney also hired Iwerks, persuading him to relocate to Hollywood from Kansas City.

In 1926, the first official ''Walt Disney Studio'' was established at 2725 Hyperion Avenue, demolished in 1940.

By 1926, Winkler's role in the distribution of the ''Alice'' series had been handed over to her husband, the film producer Charles Mintz, although the relationship between him and Disney was sometimes strained. The series ran until July 1927, by which time Disney had begun to tire of it and wanted to move away from the mixed format to all animation. After Mintz requested new material to distribute through

In 1926, the first official ''Walt Disney Studio'' was established at 2725 Hyperion Avenue, demolished in 1940.

By 1926, Winkler's role in the distribution of the ''Alice'' series had been handed over to her husband, the film producer Charles Mintz, although the relationship between him and Disney was sometimes strained. The series ran until July 1927, by which time Disney had begun to tire of it and wanted to move away from the mixed format to all animation. After Mintz requested new material to distribute through Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

, Disney and Iwerks created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit (also known as Oswald the Rabbit or Oswald Rabbit) is a cartoon character created in 1927 by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks for Universal Pictures. He starred in several animated short films released to theaters from 1927 to 1 ...

, a character Disney wanted to be "peppy, alert, saucy and venturesome, keeping him also neat and trim".

In February 1928, Disney hoped to negotiate a larger fee for producing the ''Oswald'' series, but found Mintz wanting to reduce the payments. Mintz had also persuaded many of the artists involved to work directly for him, including Harman, Ising, Carman Maxwell

Carman Griffin Maxwell (December 27, 1902 – September 22, 1987) was an American animator and voice actor.

Maxwell was born in Siloam Springs, Arkansas, and later moved to Kansas City, Missouri. He began his career at Walt Disney, where Maxwel ...

and Friz Freleng. Disney also found out that Universal owned the intellectual property rights

Intellectual property (IP) is a category of property that includes intangible creations of the human intellect. There are many types of intellectual property, and some countries recognize more than others. The best-known types are patents, cop ...

to Oswald. Mintz threatened to start his own studio and produce the series himself if Disney refused to accept the reductions. Disney declined Mintz's ultimatum and lost most of his animation staff, except Iwerks, who chose to remain with him.

Creation of Mickey Mouse to the first Academy Awards: 1928–1933

To replace Oswald, Disney and Iwerks developed Mickey Mouse, possibly inspired by a pet mouse that Disney had adopted while working in his Laugh-O-Gram studio, although the origins of the character are unclear. Disney's original choice of name was Mortimer Mouse, but his wife Lillian thought it too pompous, and suggested Mickey instead. Iwerks revised Disney's provisional sketches to make the character easier to animate. Disney, who had begun to distance himself from the animation process, provided Mickey's voice until 1947. In the words of one Disney employee, "Ub designed Mickey's physical appearance, but Walt gave him his soul." Mickey Mouse first appeared in May 1928 as a single test screening of the short ''

Mickey Mouse first appeared in May 1928 as a single test screening of the short ''Plane Crazy

''Plane Crazy'' is a 1928 American animated short film directed by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks. The cartoon, released by the Walt Disney Studios, was the first Mickey Mouse film produced, and was originally a silent film. It was given a test sc ...

'', but it, and the second feature, ''The Gallopin' Gaucho

''The Gallopin' Gaucho'' is the second short film featuring Mickey Mouse to be produced, following ''Plane Crazy'' and preceding ''Steamboat Willie''. The Disney studios completed the silent version in August 1928, but did not release it in orde ...

'', failed to find a distributor. Following the 1927 sensation ''The Jazz Singer

''The Jazz Singer'' is a 1927 American musical drama film directed by Alan Crosland. It is the first feature-length motion picture with both synchronized recorded music score as well as lip-synchronous singing and speech (in several isolate ...

'', Disney used synchronized sound on the third short, ''Steamboat Willie

''Steamboat Willie'' is a 1928 American animated short film directed by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks. It was produced in black and white by Walt Disney Studios and was released by Pat Powers, under the name of Celebrity Productions. The cartoon ...

'', to create the first post-produced sound cartoon. After the animation was complete, Disney signed a contract with the former executive of Universal Pictures, Pat Powers, to use the "Powers Cinephone" recording system; Cinephone became the new distributor for Disney's early sound cartoons, which soon became popular.

To improve the quality of the music, Disney hired the professional composer and arranger Carl Stalling, on whose suggestion the ''Silly Symphony

''Silly Symphony'' is an American animated series of 75 musical short films produced by Walt Disney Productions from 1929 to 1939. As the series name implies, the ''Silly Symphonies'' were originally intended as whimsical accompaniments to pieces ...

'' series was developed, providing stories through the use of music; the first in the series, ''The Skeleton Dance

''The Skeleton Dance'' is a 1929 ''Silly Symphony'' animated short subject produced and directed by Walt Disney and animated by Ub Iwerks. In the film, four human skeletons dance and make music around a spooky graveyard—a modern film example ...

'' (1929), was drawn and animated entirely by Iwerks. Also hired at this time were several local artists, some of whom stayed with the company as core animators; the group later became known as the Nine Old Men

Disney's Nine Old Men were Walt Disney Productions' core animators, some of whom later became directors, who created some of Disney's most famous animated cartoons, from '' Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'' (1937) onward to ''The Rescuers'' (197 ...

. Both the Mickey Mouse and ''Silly Symphonies'' series were successful, but Disney and his brother felt they were not receiving their rightful share of profits from Powers. In 1930, Disney tried to trim costs from the process by urging Iwerks to abandon the practice of animating every separate cel in favor of the more efficient technique of drawing key poses and letting lower-paid assistants sketch the poses. Disney asked Powers for an increase in payments for the cartoons. Powers refused and signed Iwerks to work for him; Stalling resigned shortly afterwards, thinking that without Iwerks, the Disney Studio would close. Disney had a nervous breakdown in October 1931which he blamed on the machinations of Powers and his own overworkso he and Lillian took an extended holiday to Cuba and a cruise to Panama to recover.

With the loss of Powers as distributor, Disney studios signed a contract with

With the loss of Powers as distributor, Disney studios signed a contract with Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. is an American film production studio that is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group, a division of Sony Pictures Entertainment, which is one of the Big Five studios and a subsidiary of the mu ...

to distribute the Mickey Mouse cartoons, which became increasingly popular, including internationally. Disney and his crew would also introduce new cartoon stars like Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Sun. It is the largest ...

in 1930, Goofy in 1932 and Donald Duck in 1934. Always keen to embrace new technology and encouraged by his new contract with United Artists

United Artists Corporation (UA), currently doing business as United Artists Digital Studios, is an American digital production company. Founded in 1919 by D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, the stud ...

, Disney filmed ''Flowers and Trees

''Flowers and Trees'' is a 1932 '' Silly Symphonies'' cartoon produced by Walt Disney, directed by Burt Gillett, and released to theatres by United Artists on July 30, 1932. It was the first commercially released film to be produced in the full- ...

'' (1932) in full-color three-strip Technicolor

Technicolor is a series of Color motion picture film, color motion picture processes, the first version dating back to 1916, and followed by improved versions over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black and white films ...

; he was also able to negotiate a deal giving him the sole right to use the three-strip process until August 31, 1935. All subsequent ''Silly Symphony'' cartoons were in color. ''Flowers and Trees'' was popular with audiences and won the inaugural Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

for best Short Subject (Cartoon) at the 1932 ceremony. Disney had been nominated for another film in that category, ''Mickey's Orphans

''Mickey's Orphans'' is a 1931 American animated short film produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by Columbia Pictures. The cartoon takes place during Christmas time and stars Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, and Pluto, who take in a group ...

'', and received an Honorary Award "for the creation of Mickey Mouse".

In 1933, Disney produced ''The Three Little Pigs

"The Three Little Pigs" is a fable about three pigs who build three houses of different materials. A Big Bad Wolf blows down the first two pigs' houses which made of straw and sticks respectively, but is unable to destroy the third pig's house t ...

'', a film described by the media historian Adrian Danks as "the most successful short animation of all time". The film won Disney another Academy Award in the Short Subject (Cartoon) category. The film's success led to a further increase in the studio's staff, which numbered nearly 200 by the end of the year. Disney realized the importance of telling emotionally gripping stories that would interest the audience, and he invested in a "story department" separate from the animators, with storyboard artist

A storyboard artist (sometimes called a story artist or visualizer) creates storyboards for advertising agencies and film productions.

Work

A storyboard artist visualizes stories and sketches frames of the story. Quick pencil drawings and mark ...

s who would detail the plots of Disney's films.

Golden age of animation: 1934–1941

By 1934, Disney had become dissatisfied with producing formulaic cartoon shorts, and believed a feature-length cartoon would be more profitable. The studio began the four-year production of ''

By 1934, Disney had become dissatisfied with producing formulaic cartoon shorts, and believed a feature-length cartoon would be more profitable. The studio began the four-year production of ''Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

"Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" is a 19th-century German fairy tale that is today known widely across the Western world. The Brothers Grimm published it in 1812 in the first edition of their collection ''Grimms' Fairy Tales'' and numbered as T ...

'', based on the fairy tale. When news leaked out about the project, many in the film industry predicted it would bankrupt the company; industry insiders nicknamed it "Disney's Folly". The film, which was the first animated feature made in full color and sound, cost $1.5 million to producethree times over budget. To ensure the animation was as realistic as possible, Disney sent his animators on courses at the Chouinard Art Institute

The Chouinard Art Institute was a professional art school founded in 1921 by Nelbert Murphy Chouinard (1879–1969) in the Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. In 1961, Walt and Roy Disney guided the merger of the Chouinard Art I ...

; he brought animals into the studio and hired actors so that the animators could study realistic movement. To portray the changing perspective of the background as a camera moved through a scene, Disney's animators developed a multiplane camera

The multiplane camera is a motion-picture camera that was used in the traditional animation process that moves a number of pieces of artwork past the camera at various speeds and at various distances from one another. This creates a sense of par ...

which allowed drawings on pieces of glass to be set at various distances from the camera, creating an illusion of depth. The glass could be moved to create the impression of a camera passing through the scene. The first work created on the cameraa ''Silly Symphony'' called ''The Old Mill

''The Old Mill'' is a 1937 ''Silly Symphonies'' cartoon produced by Walt Disney Productions, directed by Wilfred Jackson, scored by Leigh Harline, and released theatrically to theatres by RKO Radio Pictures on November 5, 1937. The film depicts ...

'' (1937)won the Academy Award for Animated Short Film because of its impressive visual power. Although ''Snow White'' had been largely finished by the time the multiplane camera had been completed, Disney ordered some scenes be re-drawn to use the new effects.

''Snow White'' premiered in December 1937 to high praise from critics and audiences. The film became the most successful motion picture of 1938 and by May 1939 its total gross of $6.5 million made it the most successful sound film made to that date. Disney won another Honorary Academy Award, which consisted of one full-sized and seven miniature Oscar statuettes. The success of ''Snow White'' heralded one of the most productive eras for the studio; the Walt Disney Family Museum calls the following years "the 'Golden Age of Animation'". With work on ''Snow White'' finished, the studio began producing ''Pinocchio

Pinocchio ( , ) is a fictional character and the protagonist of the children's novel '' The Adventures of Pinocchio'' (1883) by Italian writer Carlo Collodi of Florence, Tuscany. Pinocchio was carved by a woodcarver named Geppetto in a Tuscan ...

'' in early 1938 and '' Fantasia'' in November of the same year. Both films were released in 1940, and neither performed well at the box officepartly because revenues from Europe had dropped following the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

in 1939. The studio made a loss on both pictures and was deeply in debt by the end of February 1941.

In response to the financial crisis, Disney and his brother Roy started the company's first public stock offering in 1940, and implemented heavy salary cuts. The latter measure, and Disney's sometimes high-handed and insensitive manner of dealing with staff, led to a 1941 animators' strike which lasted five weeks. While a federal mediator from the National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an independent agency of the federal government of the United States with responsibilities for enforcing U.S. labor law in relation to collective bargaining and unfair labor practices. Under the Na ...

negotiated with the two sides, Disney accepted an offer from the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs

The Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, later known as the Office for Inter-American Affairs, was a United States agency promoting inter-American cooperation (Pan-Americanism) during the 1940s, especially in commercial and econ ...

to make a goodwill trip to South America, ensuring he was absent during a resolution he knew would be unfavorable to the studio. As a result of the strikeand the financial state of the companyseveral animators left the studio, and Disney's relationship with other members of staff was permanently strained as a result. The strike temporarily interrupted the studio's next production, ''Dumbo

''Dumbo'' is a 1941 American animated fantasy film produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by RKO Radio Pictures. The fourth Disney animated feature film, it is based upon the storyline written by Helen Aberson and Harold Pearl, ...

'' (1941), which Disney produced in a simple and inexpensive manner; the film received a positive reaction from audiences and critics alike.

World War II and beyond: 1941–1950

Shortly after the release of ''Dumbo'' in October 1941, the U.S. entered World War II. Disney formed the Walt Disney Training Films Unit within the company to produce instruction films for the military such as ''Four Methods of Flush Riveting'' and ''Aircraft Production Methods''. Disney also met with Henry Morgenthau Jr., the

Shortly after the release of ''Dumbo'' in October 1941, the U.S. entered World War II. Disney formed the Walt Disney Training Films Unit within the company to produce instruction films for the military such as ''Four Methods of Flush Riveting'' and ''Aircraft Production Methods''. Disney also met with Henry Morgenthau Jr., the Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

, and agreed to produce short Donald Duck cartoons to promote war bonds

War bonds (sometimes referred to as Victory bonds, particularly in propaganda) are debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war without raising taxes to an unpopular level. They are a ...

. Disney also produced several propaganda productions, including shorts such as ''Der Fuehrer's Face

''Der Fuehrer's Face'' (originally titled ''A Nightmare in Nutziland'' or ''Donald Duck in Nutziland'' ) is a 1943 American animated anti-Nazi propaganda short film produced by Walt Disney Productions, created in 1942 and released on January 1, ...

''which won an Academy Awardand the 1943 feature film ''Victory Through Air Power

''Victory Through Air Power'' is a 1942 non-fiction book by Alexander P. de Seversky. It was made into a 1943 Walt Disney animated feature film of the same name.

Theories

De Seversky began his military life at a young age. After serving in ...

''.

The military films generated only enough revenue to cover costs, and the feature film ''Bambi

''Bambi'' is a 1942 American animated drama film directed by David Hand (supervising a team of sequence directors), produced by Walt Disney and based on the 1923 book ''Bambi, a Life in the Woods'' by Austrian author and hunter Felix Salten ...

''which had been in production since 1937underperformed on its release in April 1942, and lost $200,000 at the box office. On top of the low earnings from ''Pinocchio'' and ''Fantasia'', the company had debts of $4 million with the Bank of America

The Bank of America Corporation (often abbreviated BofA or BoA) is an American multinational investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered at the Bank of America Corporate Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. The bank ...

in 1944. At a meeting with Bank of America executives to discuss the future of the company, the bank's chairman and founder, Amadeo Giannini

Amadeo Pietro Giannini (), also known as Amadeo Peter Giannini or A. P. Giannini (May 6, 1870 – June 3, 1949) was an American banker who founded the Bank of Italy, which became Bank of America. Giannini is credited as the inventor of many modern ...

, told his executives, "I've been watching the Disneys' pictures quite closely because I knew we were lending them money far above the financial risk. ... They're good this year, they're good next year, and they're good the year after. ... You have to relax and give them time to market their product." Disney's production of short films decreased in the late 1940s, coinciding with increasing competition in the animation market from Warner Bros.

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (commonly known as Warner Bros. or abbreviated as WB) is an American film and entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California, and a subsidiary of Warner Bros. D ...

and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 ...

. Roy Disney, for financial reasons, suggested more combined animation and live-action productions. In 1948, Disney initiated a series of popular live-action nature films, titled ''True-Life Adventures

''True-Life Adventures'' is a series of short and full-length nature documentary films released by Walt Disney Productions between the years 1948 and 1960. The first seven films released were thirty-minute shorts, with the subsequent seven films ...

'', with '' Seal Island'' the first; the film won the Academy Award in the Best Short Subject (Two-Reel) category.

Theme parks, television and other interests: 1950–1966

In early 1950, Disney produced ''Cinderella

"Cinderella",; french: link=no, Cendrillon; german: link=no, Aschenputtel) or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsi ...

'', his studio's first animated feature in eight years. It was popular with critics and theater audiences. Costing $2.2 million to produce, it earned nearly $8 million in its first year. Disney was less involved than he had been with previous pictures because of his involvement in his first entirely live-action feature, ''Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure no ...

'' (1950), which was shot in Britain, as was ''The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men

''The Story of Robin Hood'' is a 1952 action-adventure film produced by RKO- Walt Disney British Productions, based on the Robin Hood legend, made in Technicolor and filmed in Buckinghamshire, England. It was written by Lawrence Edward Watkin and ...

'' (1952). Other all-live-action features followed, many of which had patriotic themes. He continued to produce full-length animated features too, including '' Alice in Wonderland'' (1951) and ''Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a fictional character created by Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie. A free-spirited and mischievous young boy who can fly and never grows up, Peter Pan spends his never-ending childhood having adventures on the mythi ...

'' (1953). From the early to mid-1950s, Disney began to devote less attention to the animation department, entrusting most of its operations to his key animators, the Nine Old Men, although he was always present at story meetings. Instead, he started concentrating on other ventures. Around the same time, Disney would establish his own film distribution chain Buena Vista Buena Vista, meaning "good view" in Spanish, may refer to:

Places Canada

*Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador, with the name being originally derived from “Buena Vista”

*Buena Vista, Saskatchewan

*Buena Vista, Saskatoon, a neighborhood in ...

, replacing his most recent distributor RKO Pictures.

For several years Disney had been considering building a theme park. When he visited

For several years Disney had been considering building a theme park. When he visited Griffith Park

Griffith Park is a large municipal park at the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains, in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. The park includes popular attractions such as the Los Angeles Zoo, the Autry Museum of the Ameri ...

in Los Angeles with his daughters, he wanted to be in a clean, unspoiled park, where both children and their parents could have fun. He visited the Tivoli Gardens

Tivoli Gardens, also known simply as Tivoli, is an amusement park and pleasure garden in Copenhagen, Denmark. The park opened on 15 August 1843 and is the third-oldest operating amusement park in the world, after Dyrehavsbakken in nearby Klam ...

in Copenhagen, Denmark, and was heavily influenced by the cleanliness and layout of the park. In March 1952 he received zoning permission to build a theme park in Burbank, near the Disney studios. This site proved too small, and a larger plot in Anaheim, south of the studio, was purchased. To distance the project from the studiowhich might attract the criticism of shareholdersDisney formed WED Enterprises (now Walt Disney Imagineering

Walt Disney Imagineering Research & Development, Inc., commonly referred to as Imagineering, is the research and development arm of The Walt Disney Company, responsible for the creation, design, and construction of Disney theme parks and attra ...

) and used his own money to fund a group of designers and animators to work on the plans; those involved became known as "Imagineers". After obtaining bank funding he invited other stockholders, American Broadcasting-Paramount Theatres

American Broadcasting-Paramount Theatres, Inc. (originally United Paramount Theatres, later the American Broadcasting Companies and ABC Television) was the post-merger parent company of the American Broadcasting Company and United Paramount Thea ...

part of American Broadcasting Company

The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcast television network. It is the flagship property of the ABC Entertainment Group division of The Walt Disney Company. The network is headquartered in Burbank, Cali ...

(ABC)and Western Printing and Lithographing Company. In mid-1954, Disney sent his Imagineers to every amusement park in the U.S. to analyze what worked and what pitfalls or problems there were in the various locations and incorporated their findings into his design. Construction work started in July 1954, and Disneyland

Disneyland is a theme park in Anaheim, California. Opened in 1955, it was the first theme park opened by The Walt Disney Company and the only one designed and constructed under the direct supervision of Walt Disney. Disney initially envision ...

opened in July 1955; the opening ceremony was broadcast on ABC, which reached 70 million viewers. The park was designed as a series of themed lands, linked by the central Main Street, U.S.A.

Main Street, U.S.A. is the first "themed land" inside the main entrance of the many theme parks operated or licensed by The Walt Disney Company around the world. Main Street, U.S.A. is themed to resemble American small towns during the early 20t ...

a replica of the main street in his hometown of Marceline. The connected themed areas were Adventureland, Frontierland

Frontierland is one of the "themed lands" at the many Disneyland-style parks run by Disney around the world. Themed to the American Frontier of the 19th century, Frontierlands are home to cowboys and pioneers, saloons, red rock buttes and gol ...

, Fantasyland

Fantasyland is one of the "themed lands" at all of the Magic Kingdom-style parks run by The Walt Disney Company around the world. It is themed after Disney's animated fairy tale films. Each Fantasyland has a castle, as well as several gentle ri ...

and Tomorrowland

Tomorrowland is one of the many themed lands featured at all of the Magic Kingdom styled Disney theme parks around the world owned or licensed by The Walt Disney Company. Each version of the land is different and features numerous attractions t ...

. The park also contained the narrow gauge

A narrow-gauge railway (narrow-gauge railroad in the US) is a railway with a track gauge narrower than standard . Most narrow-gauge railways are between and .

Since narrow-gauge railways are usually built with tighter curves, smaller structu ...

Disneyland Railroad

The Disneyland Railroad (DRR), formerly known as the Santa Fe & Disneyland Railroad, is a 3-foot () narrow-gauge heritage railroad and attraction in the Disneyland theme park of the Disneyland Resort in Anaheim, California, in the United St ...

that linked the lands; around the outside of the park was a high berm

A berm is a level space, shelf, or raised barrier (usually made of compacted soil) separating areas in a vertical way, especially partway up a long slope. It can serve as a terrace road, track, path, a fortification line, a border/ separation ...

to separate the park from the outside world. An editorial in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' considered that Disney had "tastefully combined some of the pleasant things of yesterday with fantasy and dreams of tomorrow". Although there were early minor problems with the park, it was a success, and after a month's operation, Disneyland was receiving over 20,000 visitors a day; by the end of its first year, it attracted 3.6 million guests.

The money from ABC was contingent on Disney television programs. The studio had been involved in a successful television special on Christmas Day 1950 about the making of ''Alice in Wonderland''. Roy believed the program added millions to the box office takings. In a March 1951 letter to shareholders, he wrote that "television can be a most powerful selling aid for us, as well as a source of revenue. It will probably be on this premise that we enter television when we do". In 1954, after the Disneyland funding had been agreed, ABC broadcast '' Walt Disney's Disneyland'', an anthology consisting of animated cartoons, live-action features and other material from the studio's library. The show was successful in terms of ratings and profits, earning an audience share of over 50%. In April 1955, ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'' called the series an "American institution". ABC was pleased with the ratings, leading to Disney's first daily television program, ''The Mickey Mouse Club

''The Mickey Mouse Club'' is an American variety television show that aired intermittently from 1955 to 1996 and returned to social media in 2017. Created by Walt Disney and produced by Walt Disney Productions, the program was first televised ...

'', a variety show catering specifically to children. The program was accompanied by merchandising through various companies (Western Printing, for example, had been producing coloring books and comics for over 20 years, and produced several items connected to the show). One of the segments of ''Disneyland'' consisted of the five-part miniseries '' Davy Crockett'' which, according to Gabler, "became an overnight sensation". The show's theme song, "The Ballad of Davy Crockett

"The Ballad of Davy Crockett" is a song with music by George Bruns and lyrics by Thomas W. Blackburn. It was introduced on ABC's television series ''Disneyland'', in the premiere episode of October 27, 1954. Fess Parker is shown performing the ...

", became internationally popular, and ten million records were sold. As a result, Disney formed his own record production and distribution entity, Disneyland Records

Walt Disney Records is an American record label of the Disney Music Group. The label releases soundtrack albums from The Walt Disney Company's motion picture studios, television series, theme parks, and traditional studio albums produced by its r ...

.

As well as the construction of Disneyland, Disney worked on other projects away from the studio. He was consultant to the 1959 American National Exhibition

The American National Exhibition (July 25 to Sept. 4, 1959) was an exhibition of American art, fashion, cars, capitalism, model homes and futuristic kitchens that attracted 3 million visitors to its Sokolniki Park, Moscow venue during its six-wee ...

in Moscow; Disney Studios' contribution was ''America the Beautiful

"America the Beautiful" is a patriotic American song. Its lyrics were written by Katharine Lee Bates and its music was composed by church organist and choirmaster Samuel A. Ward at Grace Episcopal Church in Newark, New Jersey. The two neve ...

'', a 19-minute film in the 360-degree Circarama theater that was one of the most popular attractions. The following year he acted as the chairman of the Pageantry Committee for the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley, California, where he designed the opening, closing and medal ceremonies. He was one of twelve investors in the Celebrity Sports Center

Celebrity Sports Center (CSC or Celebrity's) was a family-oriented entertainment business and landmark in metropolitan Denver. Celebrity's was located in Glendale, Colorado at 888 South Colorado Boulevard near East Kentucky Avenue. It opened in ...

, which opened in 1960 in Glendale, Colorado

The City of Glendale is a home rule municipality located in an exclave of Arapahoe County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 4,613 at the 2020 United States Census. Glendale is an enclave of the City and County of Denver and is ...

; he and Roy bought out the others in 1962, making the Disney company the sole owner.

Despite the demands wrought by non-studio projects, Disney continued to work on film and television projects. In 1955, he was involved in "

Despite the demands wrought by non-studio projects, Disney continued to work on film and television projects. In 1955, he was involved in "Man in Space

"Man in Space" is an episode of the American television series ''Disneyland'' which originally aired on March 9, 1955. It was directed by Disney animator Ward Kimball. This ''Disneyland'' episode (set in Tomorrowland), was narrated partly by Kimb ...

", an episode of the ''Disneyland'' series, which was made in collaboration with NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

rocket designer Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

. Disney also oversaw aspects of the full-length features ''Lady and the Tramp

''Lady and the Tramp'' is a 1955 American animated musical romance film produced by Walt Disney and released by Buena Vista Film Distribution. The 15th Disney animated feature film, it was directed by Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, and ...

'' (the first animated film in CinemaScope) in 1955, ''Sleeping Beauty

''Sleeping Beauty'' (french: La belle au bois dormant, or ''The Beauty in the Sleeping Forest''; german: Dornröschen, or ''Little Briar Rose''), also titled in English as ''The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods'', is a fairy tale about a princess cu ...

'' (the first animated film in Technirama

__NOTOC__

Technirama is a screen process that has been used by some film production houses as an alternative to CinemaScope. It was first used in 1957 but fell into disuse in the mid-1960s. The process was invented by Technicolor and is an anamor ...

70 mm film

70 mm film (or 65 mm film) is a wide high-resolution film gauge for motion picture photography, with a negative area nearly 3.5 times as large as the standard 35 mm motion picture film format. As used in cameras, the film is wid ...

) in 1959, ''One Hundred and One Dalmatians

''One Hundred and One Dalmatians'' (also simply known as ''101 Dalmatians'') is a 1961 American animated adventure comedy film produced by Walt Disney Productions and based on the 1956 novel '' The Hundred and One Dalmatians'' by Dodie Smith. Th ...

'' (the first animated feature film to use Xerox cels) in 1961, and '' The Sword in the Stone'' in 1963.

In 1964, Disney produced '' Mary Poppins'', based on the book series by P. L. Travers; he had been trying to acquire the rights to the story since the 1940s. It became the most successful Disney film of the 1960s, although Travers disliked the film intensely and regretted having sold the rights. The same year he also became involved in plans to expand the California Institute of the Arts

The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) is a private art university in Santa Clarita, California. It was incorporated in 1961 as the first degree-granting institution of higher learning in the US created specifically for students of both ...

(colloquially called CalArts), and had an architect draw up blueprints for a new building.

Disney provided four exhibits for the 1964 New York World's Fair, for which he obtained funding from selected corporate sponsors. For PepsiCo, who planned a tribute to UNICEF

UNICEF (), originally called the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund in full, now officially United Nations Children's Fund, is an agency of the United Nations responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid to ...

, Disney developed It's a Small World

"It's a Small World" is a water-based boat ride located in the Fantasyland area at various Disney theme parks worldwide, including Disneyland Park in Anaheim, California; Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida; Tokyo D ...

, a boat ride with audio-animatronic dolls depicting children of the world; Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln

''Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln'' is a stage show featuring an Audio-Animatronic representation of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, best known for being presented at Disneyland since 1965. It was originally showcased as the prime feature of t ...

contained an animatronic Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

giving excerpts from his speeches; Carousel of Progress

Walt Disney's Carousel of Progress is a rotating theater audio-animatronic stage show attraction in Tomorrowland at the Magic Kingdom theme park at the Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida just outside of Orlando, Florida. Created ...

promoted the importance of electricity; and Ford's Magic Skyway portrayed the progress of mankind. Elements of all four exhibitsprincipally concepts and technologywere re-installed in Disneyland, although It's a Small World is the ride that most closely resembles the original.

During the early to mid-1960s, Disney developed plans for a ski resort

A ski resort is a resort developed for skiing, snowboarding, and other winter sports. In Europe, most ski resorts are towns or villages in or adjacent to a ski area – a mountainous area with pistes (ski trails) and a ski lift system. In Nort ...

in Mineral King, a glacial valley in California's Sierra Nevada. He hired experts such as the renowned Olympic ski coach and ski-area designer Willy Schaeffler

Wilhelm Josef "Willy" Schaeffler (13 December 1915 – 9 April 1988) was a German-American skiing champion, winning coach, and ski resort developer. In skiing, he is best known to the public for his intensive training programs that led the U.S. S ...

. With income from Disneyland accounting for an increasing proportion of the studio's income, Disney continued to look for venues for other attractions. In 1963 he presented a project to create a theme park in downtown St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Missouri; he initially reached an agreement with the Civic Center Redevelopment Corp, which controlled the land, but the deal later collapsed over funding. In late 1965, he announced plans to develop another theme park to be called "Disney World" (now Walt Disney World

The Walt Disney World Resort, also called Walt Disney World or Disney World, is an entertainment resort complex in Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista, Florida, United States, near the cities of Orlando and Kissimmee. Opened on October 1, 1971, ...

), a few miles southwest of Orlando, Florida. Disney World was to include the "Magic Kingdom"a larger and more elaborate version of Disneylandplus golf courses and resort hotels. The heart of Disney World was to be the "Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow" (EPCOT

Epcot, stylized in all uppercase as EPCOT, is a theme park at the Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida. It is owned and operated by The Walt Disney Company through its Parks, Experiences and Products division. Inspired by an unreal ...

), which he described as:

an experimental prototype community of tomorrow that will take its cue from the new ideas and new technologies that are now emerging from the creative centers of American industry. It will be a community of tomorrow that will never be completed, but will always be introducing and testing and demonstrating new materials and systems. And EPCOT will always be a showcase to the world for the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise.During 1966, Disney cultivated businesses willing to sponsor EPCOT. He received a story credit in the 1966 film ''

Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N.

''Lt. Robin Crusoe U.S.N.'' is a 1966 American comedy film released and scripted by Walt Disney,Zibart, Eve : "Today in History Disney", Emmis Books, 2006, and starring Dick Van Dyke as a U.S. Navy pilot who becomes a castaway on a tropical islan ...

'' as Retlaw Yensid, his name spelt backwards. He increased his involvement in the studio's films, and was heavily involved in the story development of ''The Jungle Book

''The Jungle Book'' (1894) is a collection of stories by the English author Rudyard Kipling. Most of the characters are animals such as Shere Khan the tiger and Baloo the bear, though a principal character is the boy or "man-cub" Mowgli, w ...

'', the live-action musical feature ''The Happiest Millionaire

''The Happiest Millionaire'' is a 1967 American musical film starring Fred MacMurray, based upon the true story of Philadelphia millionaire Anthony Drexel Biddle. The film, featuring music by the Sherman Brothers, was nominated for an Academy A ...

'' (both 1967) and the animated short ''Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day

''Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day'' is a 1968 American animated featurette based on the third, fifth, ninth, and tenth chapters of ''Winnie-the-Pooh'' and the second, eighth, and ninth chapters from ''The House at Pooh Corner'' by A. A. Milne ...

'' (1968).

Illness, death and aftermath

filters

Filter, filtering or filters may refer to:

Science and technology

Computing

* Filter (higher-order function), in functional programming

* Filter (software), a computer program to process a data stream

* Filter (video), a software component tha ...

and had smoked a pipe as a young man. In early November 1966, he was diagnosed with lung cancer and was treated with cobalt therapy

Cobalt therapy is the medical use of gamma rays from the radioisotope cobalt-60 to treat conditions such as cancer. Beginning in the 1950s, cobalt-60 was widely used in external beam radiotherapy (teletherapy) machines, which produced a beam ...

. On November 30, he felt unwell and was taken by ambulance from his home to St. Joseph Hospital where, on December 15, 1966, aged 65, he died of circulatory collapse

Shock is the state of insufficient blood flow to the tissues of the body as a result of problems with the circulatory system. Initial symptoms of shock may include weakness, fast heart rate, fast breathing, sweating, anxiety, and increased thi ...

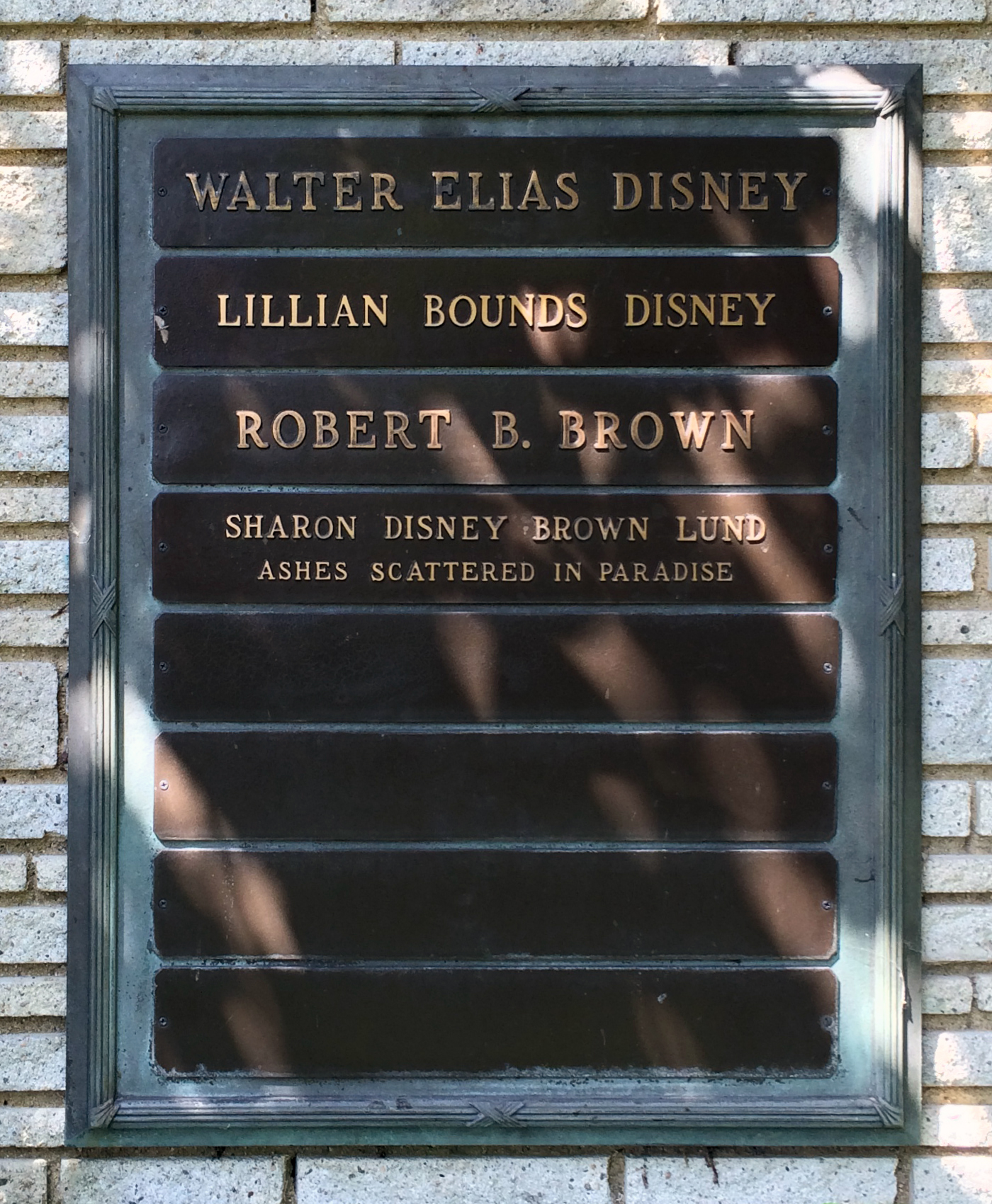

caused by the cancer. His remains were cremated two days later and his ashes interred at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

The release of ''The Jungle Book'' and ''The Happiest Millionaire'' in 1967 raised the total number of feature films that Disney had been involved in to 81. When ''Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day'' was released in 1968, it earned Disney an Academy Award in the Short Subject (Cartoon) category, awarded posthumously. After Disney's death, his studios continued to produce live-action films prolifically but largely abandoned animation until the late 1980s, after which there was what ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' describes as the "Disney Renaissance

The Disney Renaissance was the period from 1989 to 1999 during which Walt Disney Feature Animation returned to producing critically and commercially successful animated films that were mostly musical adaptations of well-known stories, much ...

" that began with ''The Little Mermaid

"The Little Mermaid" ( da, Den lille havfrue) is a literary fairy tale written by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen. The story follows the journey of a young mermaid who is willing to give up her life in the sea as a mermaid to gain a ...

'' (1989). Disney's companies continue to produce successful film, television and stage entertainment.

Disney's plans for the futuristic city of EPCOT did not come to fruition. After Disney's death, his brother Roy deferred his retirement to take full control of the Disney companies. He changed the focus of the project from a town to an attraction. At the inauguration in 1971, Roy dedicated Walt Disney World to his brother. Walt Disney World expanded with the opening of

Disney's plans for the futuristic city of EPCOT did not come to fruition. After Disney's death, his brother Roy deferred his retirement to take full control of the Disney companies. He changed the focus of the project from a town to an attraction. At the inauguration in 1971, Roy dedicated Walt Disney World to his brother. Walt Disney World expanded with the opening of Epcot Center

Epcot, stylized in all uppercase as EPCOT, is a theme park at the Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida. It is owned and operated by The Walt Disney Company through its Parks, Experiences and Products division. Inspired by an unreal ...

in 1982; Walt Disney's vision of a functional city was replaced by a park more akin to a permanent world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

. In 2009, the Walt Disney Family Museum, designed by Disney's daughter Diane and her son Walter E. D. Miller, opened in the Presidio of San Francisco. Thousands of artifacts from Disney's life and career are on display, including numerous awards that he received. In 2014, the Disney theme parks around the world hosted approximately 134 million visitors.

Personal life and character

Early in 1925, Disney hired an ink artist, Lillian Bounds. They married in July of that year, at her brother's house in her hometown of Lewiston, Idaho. The marriage was generally happy, according to Lillian, although according to Disney's biographerNeal Gabler

Neal Gabler (born 1950) is an American journalist, writer and film critic.

Gabler graduated from Lane Tech High School in Chicago, Illinois, class of 1967, and was inducted into the National Honor Society. He graduated ''summa cum laude'' from t ...

she did not "accept Walt's decisions meekly or his status unquestionably, and she admitted that he was always telling people 'how henpecked he is'." Lillian had little interest in films or the Hollywood social scene and she was, in the words of the historian Steven Watts, "content with household management and providing support for her husband". Their marriage produced two daughters, Diane (born December 1933) and Sharon (adopted in December 1936, born six weeks previously). Within the family, neither Disney nor his wife hid the fact Sharon had been adopted, although they became annoyed if people outside the family raised the point. The Disneys were careful to keep their daughters out of the public eye as much as possible, particularly in the light of the Lindbergh kidnapping

On March 1, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. (born June 22, 1930), the 20-month-old son of aviators Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, was abducted from his crib in the upper floor of the Lindberghs' home, Highfields, in East Am ...

; Disney took steps to ensure his daughters were not photographed by the press.

In 1949, Disney and his family moved to a new home in the

In 1949, Disney and his family moved to a new home in the Holmby Hills