Wyndham Lewis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

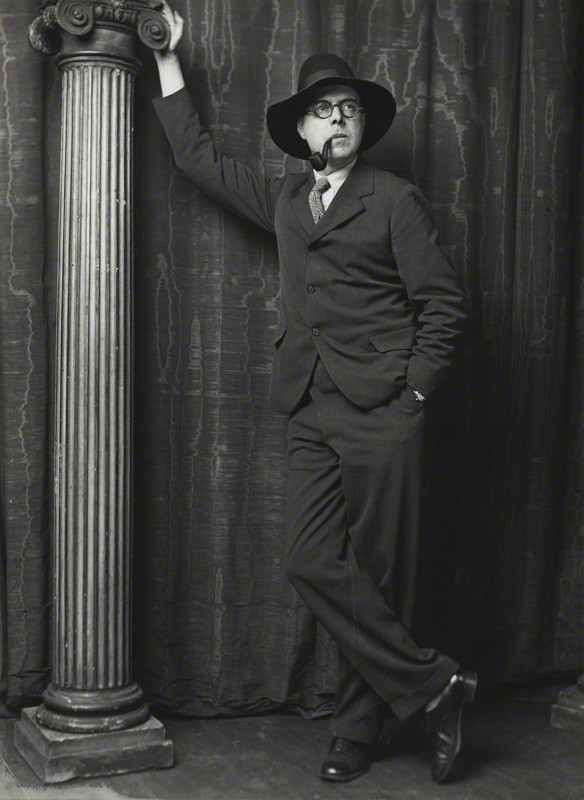

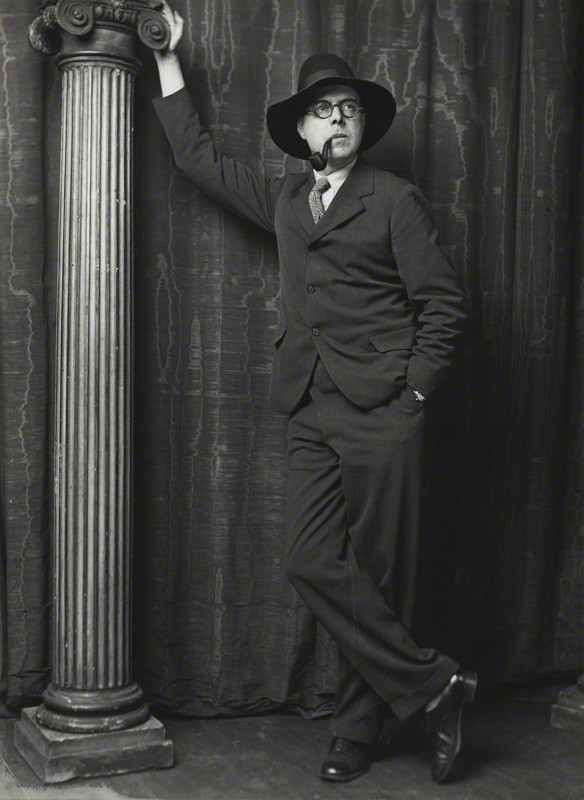

Percy Wyndham Lewis (18 November 1882 – 7 March 1957) was a British writer, painter and critic. He was a co-founder of the

"Lewis, (Percy) Wyndham (1882–1957)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. His English mother, Anne Stuart Lewis (

, FluxEuropa. In ''Blast'' Lewis formally expounded the Vorticist aesthetic in a manifesto, distinguishing it from other avant-garde practices. He also wrote and published a play, ''Enemy of the Stars''. It is a proto-absurdist,

In 1915 the Vorticists held their only British exhibition before the movement broke up, largely as a result of the

In 1915 the Vorticists held their only British exhibition before the movement broke up, largely as a result of the

In 1930 Lewis published '' The Apes of God'', a biting satirical attack on the London literary scene, including a long chapter caricaturing the Sitwell family. The writer

In 1930 Lewis published '' The Apes of God'', a biting satirical attack on the London literary scene, including a long chapter caricaturing the Sitwell family. The writer

Lewis was a

Lewis was a

] ''If Winter Comes (novel), If Winter Comes'', is absent from them."Fifty Orwell Essays

A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook In 1932 Walter Sickert sent Lewis a Telegraphy, telegram in which he said that Lewis's pencil portrait of

Hitler

' (1931) (essay) *''The Diabolical Principle and the Dithyrambic Spectator'' (1931) (essays) *''Doom of Youth'' (1932) (essays) *''Filibusters in Barbary'' (1932) (travel; later republished as ''Journey into Barbary'') *''Enemy of the Stars'' (1932) (play) *''Snooty Baronet'' (1932) (novel) *''One-Way Song'' (1933) (poetry) *''Men Without Art'' (1934) (criticism) *''Left Wings over Europe; or, How to Make a War about Nothing'' (1936) (essays) *'' Blasting and Bombardiering'' (1937) (autobiography) *''The Revenge for Love'' (1937) (novel) *''Count Your Dead: They are Alive!: Or, A New War in the Making'' (1937) (essays) *''The Mysterious Mr. Bull'' (1938) *''The Jews, Are They Human?'' (1939) (essay) *''The Hitler Cult and How it Will End'' (1939) (essay) *''America, I Presume'' (1940) (travel) *''The Vulgar Streak'' (1941) (novel) *''Anglosaxony: A League that Works'' (1941) (essay) *''America and Cosmic Man'' (1949) (essay) *''Rude Assignment'' (1950) (autobiography) *''Rotting Hill'' (1951) (short stories) *''The Writer and the Absolute'' (1952) (essay) *''Self Condemned'' (1954) (novel) *''The Demon of Progress in the Arts'' (1955) (essay) *''Monstre Gai'' (1955) (novel) *''Malign Fiesta'' (1955) (novel) *''The Red Priest'' (1956) (novel) *''The Letters of Wyndham Lewis'' (1963) (letters) *''The Roaring Queen'' (1973; written 1936 but unpublished) (novel) *''Unlucky for Pringle'' (1973) (short stories) *''Mrs Duke's Million'' (1977; written 1908–10 but unpublished) (novel) *''Creatures of Habit and Creatures of Change'' (1989) (essays)

*''The Theatre Manager'' (1909), watercolour

*''The Courtesan'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Indian Dance'' (1912), chalk and watercolour

*''Russian Madonna'' (also known as ''Russian Scene'') (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Lovers'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Mother and Child'' (1912), oil on canvas, now lost

*''The Dancers'' (study for ''Kermesse'') (1912), black ink and watercolour

*''The Theatre Manager'' (1909), watercolour

*''The Courtesan'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Indian Dance'' (1912), chalk and watercolour

*''Russian Madonna'' (also known as ''Russian Scene'') (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Lovers'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Mother and Child'' (1912), oil on canvas, now lost

*''The Dancers'' (study for ''Kermesse'') (1912), black ink and watercolour

(image

*''Composition'' (1913), pen and ink, watercolour

(image

*''Plan of War'' (1913–14), oil on canvas *''Slow Attack'' (1913–14), oil on canvas *''New York'' (1914), pen and ink, watercolour *''Argol'' (1914), pen and ink, watercolour *''The Crowd (Lewis), The Crowd'' (1914–15), oil paint and graphite on canvas

(image

*''Workshop'' (1914–15), oil on canvas

(image

*''Vorticist Composition'' (1915), gouache and chalk

(image

*''A Canadian Gun-pit'' (1919), oil on canvas

(image

*'' A Battery Shelled'' (1919), oil on canvas

(image

*''Mr Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro'' (1920–21), oil on canvas

(image

*''A Reading of Ovid (Tyros)'' (1920–21), oil on canvas

(image

*''Seated Figure'' (c. 1921

(image

*''Mrs Schiff'' (1923–24), oil on canvas

(image

*''Edith Sitwell (Lewis), Edith Sitwell'' (1923–1935), oil on canvas

(image

*''Bagdad'' (1927–28), oil on wood

(image

*''Three Veiled Figures'' (1933), oil on canvas

(image

*''Creation Myth'' (1933–1936, oil on canvas

(image

*''Red Scene'' (1933–1936), oil on canvas

(image

*''One of the Stations of the Dead'' (1933–1837), oil on canvas

(image

*''The Surrender of Barcelona'' (1934–1937), oil on canvas

(image

*''Panel for the Safe of a Great Millionaire'' (1936–37), oil on canvas

(image

*''Newfoundland'' (1936–37), oil on canvas

(image

*''Pensive Head'' (1937), oil on canvas

(image

*''Portrait of T. S. Eliot'' (1938), oil on canvas *''La Suerte'' (1938), oil on canvas

(image

*''John Macleod'' (1938), oil on canva

(image

*''

(image

*''Mrs R.J. Sainsbury (1940–41), oil on canvas

(image

*''A Canadian War Factory'' (1943), oil on canvas

(image

*''Nigel Tangye'' (1946), oil on canvas

(image

Wyndham Lewis and Modernism

Tavistock: Northcote House. * Gasiorek, Andrzej, Reeve-Tucker, Alice, and Waddell, Nathan. (2011)

Wyndham Lewis and the Cultures of Modernity

'. Aldershot: Ashgate. * Grigson, Geoffrey (1951). ''A Master of Our Time: A Study of Wyndham Lewis''. London: Methuen. * Hammer, Martin (1981) ''Out of the Vortex: Wyndham Lewis as Painter'', in ''Cencrastus'' No. 5, Summer 1981, pp. 31–33, . * Jaillant, Lise.

Rewriting Tarr Ten Years Later: Wyndham Lewis, the Phoenix Library and the Domestication of Modernism

" Journal of Wyndham Lewis Studies 5 (2014): 1–30. * Jameson, Fredric. (1979) ''Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist''. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. * Kenner, Hugh. (1954) ''Wyndham Lewis''. New York: New Directions. * Klein, Scott W. (1994) ''The Fictions of James Joyce and Wyndham Lewis: Monsters of Nature and Design.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Leavis, F.R. (1964)

"Mr. Eliot, Mr. Wyndham Lewis and Lawrence."

In ''The Common Pursuit'', New York University Press. * Michel, Walter. (1971) ''Wyndham Lewis: Paintings and Drawings''. Berkeley: University of California Press. * Meyers, Jeffrey. (1980) ''The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis.'' London and Henley: Routledge & Keegan Paul. * Morrow, Bradford and Bernard Lafourcade. (1978) ''A Bibliography of the Writings of Wyndham Lewis''. Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press. * Normand, Tom. (1993) ''Wyndham Lewis the Artist: Holding the Mirror up to Politics''. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. * O'Keeffe, Paul. (2000) ''Some Sort of Genius: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis''. London: Cape. * Orage, A.R. (1922)

"Mr. Pound and Mr. Lewis in Public."

In ''Readers and Writers (1917–1921)'', London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. * Rothenstein, John (1956)

"Wyndham Lewis."

In ''Modern English Painters. Lewis To Moore'', London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. * Rutter, Frank (1922)

"Wyndham Lewis."

In ''Some Contemporary Artists'', London: Leonard Parsons. * Rutter, Frank (1926)

''Evolution in Modern Art: A Study of Modern Painting, 1870–1925''

London: George G. Harrap. * Schenker, Daniel. (1992) ''Wyndham Lewis: Religion and Modernism''. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama Press. * Spender, Stephen (1978). ''The Thirties and After: Poetry, Politics, People (1933–1975)'', Macmillan. * Stevenson, Randall (1982), ''The Other Centenary: Wyndham Lewis, 1882–1982'', in Hearn, Sheila G. (ed.), ''Cencrastus'' No. 10, Autumn 1982, pp. 18–21, * Waddell, Nathan. (2012)

Modernist Nowheres: Politics and Utopia in Early Modernist Writing, 1900–1920

'. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. * Wagner, Geoffrey (1957)

''Wyndham Lewis: A Portrait of the Artist as the Enemy''

New Haven: Yale University Press. * Woodcock, George, ed. ''Wyndham Lewis in Canada''. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Publications, 1972.

Wyndham Lewis Society

*

Wyndham Lewis

at ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' * *

Time and Western Man

' essay by Kirsty Dootson * *

' audiobook CD

at Cornell University Library

Wyndham Lewis: Self Condemned

essay in ''The Walrus'' *

Cyril J. Fox-Wyndham Lewis collection

at the University of Victoria

Wyndham Lewis collection (1945–1956)

at the University of Victoria * *

(1914) at the Poetry Foundation

Wyndham Lewis Collection

at Clara Thomas]

Archives & Special Collections

York University * Wyndham Lewis Art Collectio

1898–1949

an

1915–1977, undated

at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin {{DEFAULTSORT:Lewis, Wyndham Wyndham Lewis, 1882 births 1957 deaths 20th-century English male writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English painters Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art British artists with disabilities British Army personnel of World War I English war artists English blind people English magazine editors English male novelists English male painters English people of American descent English satirists English satirical novelists Group X People born at sea People educated at Rugby School Post-impressionist painters Royal Artillery officers Vorticists World War I artists 20th-century British war artists

Vorticist

Vorticism was a London-based Modernism, modernist art movement formed in 1914 by the writer and artist Wyndham Lewis. The movement was partially inspired by Cubism and was introduced to the public by means of the publication of the Vorticist mani ...

movement in art and edited '' Blast'', the literary magazine of the Vorticists.

His novels include '' Tarr'' (1916–17) and ''The Human Age'' trilogy, comprising ''The Childermass'' (1928), ''Monstre Gai'' (1955) and ''Malign Fiesta'' (1955). A fourth volume, ''The Trial of Man'', remained unfinished upon his death. He wrote two autobiographical volumes: '' Blasting and Bombardiering'' (1937) and ''Rude Assignment: A Narrative of my Career Up-to-Date'' (1950).

Life and career

Early life

Percy Wyndham Lewis was born on 18 November 1882, reputedly on his father's yacht off theCanadian province

Canada has ten provinces and three territories that are sub-national administrative divisions under the jurisdiction of the Constitution of Canada, Canadian Constitution. In the 1867 Canadian Confederation, three provinces of British North Amer ...

of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

.Richard Cork"Lewis, (Percy) Wyndham (1882–1957)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. His English mother, Anne Stuart Lewis (

née

The birth name is the name of the person given upon their birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name or to the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a births registe ...

Prickett), and American father, Charles Edward Lewis, separated about 1893. His mother subsequently returned to England. Lewis was educated in England at Rugby School

Rugby School is a Public school (United Kingdom), private boarding school for pupils aged 13–18, located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire in England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independ ...

and then, from 16, the Slade School of Fine Art

The UCL Slade School of Fine Art (informally The Slade) is the art school of University College London (UCL) and is based in London, England. It has been ranked as the UK's top art and design educational institution. The school is organised as ...

, University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

, but left for Paris without finishing his course. He spent most of the 1900s travelling around Europe and studying art in Paris. Whilst there he attended lectures by Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; ; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopher who was influential in the traditions of analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, especially during the first half of the 20th century until the S ...

on process philosophy

Process philosophy (also ontology of becoming or processism) is an approach in philosophy that identifies processes, changes, or shifting relationships as the only real experience of everyday living. In opposition to the classical view of change ...

.

Early work and development of Vorticism (1908–1915)

In 1908 Lewis moved toLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England, where he would reside for much of his life. In 1909 he published his first work, accounts of his travels in Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

, in Ford Madox Ford

Ford Madox Ford (né Joseph Leopold Ford Hermann Madox Hueffer ( ); 17 December 1873 – 26 June 1939) was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor whose journals ''The English Review'' and ''The Transatlantic Review (1924), The Transatlant ...

's ''The English Review''. He was a founding member of the Camden Town Group, which brought him into close contact with the Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group was a group of associated British writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the early 20th century. Among the people involved in the group were Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Vanessa Bell, a ...

, particularly Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and art critic, critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent ...

and Clive Bell

Arthur Clive Heward Bell (16 September 1881 – 17 September 1964) was an English art critic, associated with formalism and the Bloomsbury Group. He developed the art theory known as significant form.

Biography Early life and education

Bell ...

, with whom he soon fell out.

In 1912 he exhibited his work at the second Post-Impressionist

Post-Impressionism (also spelled Postimpressionism) was a predominantly French art movement that developed roughly between 1886 and 1905, from the last Impressionist exhibition to the birth of Fauvism. Post-Impressionism emerged as a reaction a ...

exhibition: Cubo-Futurist illustrations to ''Timon of Athens

''The Life of Tymon of Athens'', often shortened to ''Timon of Athens'', is a play written by William Shakespeare and likely also Thomas Middleton in about 1606. It was published in the ''First Folio'' in 1623. Timon of Athens (person), Timon ...

'' and three major oil paintings. In 1912 he was commissioned to produce a decorative mural, a drop curtain, and more designs for The Cave of the Golden Calf, an avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

nightclub and cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, casino, hotel, restaurant, or nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining or drinking, ...

on Heddon Street.

From 1913 to 1915 Lewis developed the style of geometric abstraction

Abstraction is a process where general rules and concepts are derived from the use and classifying of specific examples, literal (reality, real or Abstract and concrete, concrete) signifiers, first principles, or other methods.

"An abstraction" ...

for which he is best known today, which his friend Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

dubbed "Vorticism

Vorticism was a London-based Modernism, modernist art movement formed in 1914 by the writer and artist Wyndham Lewis. The movement was partially inspired by Cubism and was introduced to the public by means of the publication of the Vorticist mani ...

". Lewis sought to combine the strong structure of Cubism

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement which began in Paris. It revolutionized painting and the visual arts, and sparked artistic innovations in music, ballet, literature, and architecture.

Cubist subjects are analyzed, broke ...

, which he found was not "alive", with the liveliness of Futurist

Futurists (also known as futurologists, prospectivists, foresight practitioners and horizon scanners) are people whose specialty or interest is futures studies or futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities ...

art, which lacked structure. The combination was a strikingly dramatic critique of modernity. In his early visual works Lewis may have been influenced by Bergson's process philosophy

Process philosophy (also ontology of becoming or processism) is an approach in philosophy that identifies processes, changes, or shifting relationships as the only real experience of everyday living. In opposition to the classical view of change ...

. Though he was later savagely critical of Bergson, he admitted in a letter to Theodore Weiss (19 April 1949) that he "began by embracing his evolutionary system." The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

was an equally important influence.

Lewis had a brief tenure at Roger Fry's Omega Workshops, but left after a quarrel with Fry over a commission to provide wall decorations for the Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

Ideal Home Exhibition, which Lewis believed Fry had misappropriated. He and several other Omega artists started a competing workshop called the Rebel Art Centre. The Centre operated for only four months, but it gave birth to the Vorticist group and its publication, '' Blast''."The Art and Ideas of Wyndham Lewis", FluxEuropa. In ''Blast'' Lewis formally expounded the Vorticist aesthetic in a manifesto, distinguishing it from other avant-garde practices. He also wrote and published a play, ''Enemy of the Stars''. It is a proto-absurdist,

Expressionist

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

drama. The Lewis scholar Melania Terrazas identifies it as a precursor to the plays of Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish writer of novels, plays, short stories, and poems. Writing in both English and French, his literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal, and Tragicomedy, tra ...

.

World War I (1915–1918)

In 1915 the Vorticists held their only British exhibition before the movement broke up, largely as a result of the

In 1915 the Vorticists held their only British exhibition before the movement broke up, largely as a result of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Lewis himself was posted to the Western Front and served as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

. Much of his time was spent in Forward Observation Posts looking down at apparently deserted German lines, registering targets and calling down fire from batteries massed around the rim of the Ypres Salient

The Ypres Salient, around Ypres, in Belgium, was the scene of several battles and a major part of the Western Front during World War I.

Location

Ypres lies at the junction of the Ypres–Comines Canal and the Ieperlee. The city is overlooked b ...

. He made vivid accounts of narrow misses and deadly artillery duels.

After the Third Battle of Ypres

The Third Battle of Ypres (; ; ), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele ( ), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies against the German Empire. The battle took place on the Western Front, from July to November 1917, f ...

Lewis was appointed an official war artist

A war artist is an artist either commissioned by a government or publication, or self-motivated, to document first-hand experience of war in any form of illustrative or depictive record.Imperial War Museum (IWM)header phrase, "war shapes lives" ...

for the Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

and British governments. For the Canadians he painted '' A Canadian Gun-pit'' (1918) from sketches made on Vimy Ridge

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was part of the Battle of Arras, in the Pas-de-Calais department of France, during the First World War. The main combatants were the four divisions of the Canadian Corps in the First Army, against three divisions of ...

. For the British he painted one of his best-known works, '' A Battery Shelled'' (1919), drawing on his own experience at Ypres. Lewis exhibited his war drawings and some other paintings of the war in an exhibition, "Guns", in 1918. Although the Vorticist group broke up after the war, Lewis's patron, John Quinn, organised a Vorticist exhibition at the Penguin Club in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

in 1917.

Between 1907 and 1911 Lewis had written what would be his first published novel, '' Tarr'', which was revised and expanded in 1914–15 and serialised in the London literary magazine '' The Egoist'' from April 1916 to November 1917. It was first published in book form in 1918 by Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

in New York and by ''The Egoist'' in London. It is widely regarded as one of the key texts in literary modernism

Modernist literature originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterised by a self-conscious separation from traditional ways of writing in both poetry and prose fiction writing. Modernism experimented with literary form a ...

.

Lewis later documented his experiences and opinions of this period of his life in the autobiographical ''Blasting and Bombardiering'' (1937), which covered the time up to 1926.

''Tyros'' and writing (1918–1929)

After the war Lewis resumed his career as a painter with a major exhibition, ''Tyros and Portraits'', at theLeicester Galleries

Leicester Galleries was an art gallery located in London from 1902 to 1977 that held exhibitions of modern British, French and international artists' works. Its name was acquired in 1984 by Peter Nahum, who operates "Peter Nahum at the Leiceste ...

in 1921. "Tyros" were satirical caricatures intended to comment on the culture of the "new epoch" that succeeded the First World War. ''A Reading of Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

'' and ''Mr Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro'' are the only surviving oil paintings from this series. Lewis also launched his second magazine, ''The Tyro'', of which there were only two issues. The second (1922) contained an important statement of Lewis's visual aesthetic: "Essay on the Objective of Plastic Art in our Time". It was during the early 1920s that he perfected his incisive draughtsmanship.

By the late 1920s he concentrated on writing. He launched another magazine, ''The Enemy'' (1927–1929), largely written by himself and declaring its belligerent critical stance in its title. The magazine and other theoretical and critical works he published from 1926 to 1929 mark a deliberate separation from the avant-garde and his previous associates. He believed that their work failed to show sufficient critical awareness of those ideologies that worked against truly revolutionary change in the West, and therefore became a vehicle for these pernicious ideologies. His major theoretical and cultural statement from this period is ''The Art of Being Ruled'' (1926).

''Time and Western Man'' (1927) is a cultural and philosophical discussion that includes penetrating critiques of James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

, Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris in 1903, and ...

and Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

that are still read. Lewis also attacked the process philosophy

Process philosophy (also ontology of becoming or processism) is an approach in philosophy that identifies processes, changes, or shifting relationships as the only real experience of everyday living. In opposition to the classical view of change ...

of Bergson, Samuel Alexander

Samuel Alexander (6 January 1859 – 13 September 1938) was an Australian-born British philosopher. He was the first Jewish fellow of an Oxbridge college. He is now best known as an advocate of emergentism in biology.

Early life

He was b ...

, Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, inclu ...

and others. By 1931 he was advocating the art of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

as impossible to surpass.

Fiction and political writing (1930–1936)

In 1930 Lewis published '' The Apes of God'', a biting satirical attack on the London literary scene, including a long chapter caricaturing the Sitwell family. The writer

In 1930 Lewis published '' The Apes of God'', a biting satirical attack on the London literary scene, including a long chapter caricaturing the Sitwell family. The writer Richard Aldington

Richard Aldington (born Edward Godfree Aldington; 8 July 1892 – 27 July 1962) was an English writer and poet. He was an early associate of the Imagist movement. His 50-year writing career covered poetry, novels, criticism and biography. He ed ...

, however, found it "the greatest piece of ''writing'' since '' Ulysses''", by James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

. In 1937 Lewis published ''The Revenge for Love'', set in the period leading up to the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

and regarded by many as his best novel. It is strongly critical of communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

activity in Spain and presents English intellectual fellow traveller

A fellow traveller (also fellow traveler) is a person who is intellectually sympathetic to the ideology of a political organization, and who co-operates in the organization's politics, without being a formal member. In the early history of the Sov ...

s as deluded.

Despite serious illness necessitating several operations, he was very productive as a critic and painter. He produced a book of poems, ''One-Way Song'', in 1933, and a revised version of ''Enemy of the Stars''. An important book of critical essays also belongs to this period: ''Men without Art'' (1934). It grew out of a defence of Lewis's satirical practice in ''The Apes of God'' and puts forward a theory of "non-moral", or metaphysical, satire. The book is probably best remembered for one of the first commentaries on William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for William Faulkner bibliography, his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in fo ...

and a famous essay on Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

.

Return to painting (1936–1941)

After becoming better known for his writing than his painting in the 1920s and early 1930s, he returned to more concentrated work on visual art, and paintings from the 1930s and 1940s constitute some of his best-known work. The '' Surrender of Barcelona'' (1936–37) makes a significant statement about theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

. It was included in an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1937 that Lewis hoped would re-establish his reputation as a painter. After the publication in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' of a letter of support for the exhibition, asking for something from the show to be purchased for the national collection (signed by, among others, Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed U.S. Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry ...

, W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, ...

, Geoffrey Grigson, Rebecca West

Dame Cecily Isabel Fairfield (21 December 1892 – 15 March 1983), known as Rebecca West, or Dame Rebecca West, was a British author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. An author who wrote in many genres, West reviewed books ...

, Naomi Mitchison

Naomi Mary Margaret Mitchison, Baroness Mitchison (; 1 November 1897 – 11 January 1999) was a List of Scottish novelists, Scottish novelist and poet. Often called a doyenne of Scottish literature, she wrote more than 90 books of historical an ...

, Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi-abstract art, abstract monumental Bronze sculpture, bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. Moore ...

and Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as "the greatest artist-craftsma ...

) the Tate Gallery

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the UK ...

bought the painting, ''Red Scene''. Like others from the exhibition, it shows an influence from Surrealism

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

and Giorgio de Chirico

Giuseppe Maria Alberto Giorgio de Chirico ( ; ; 10 July 1888 – 20 November 1978) was an Italian artist and writer born in Greece. In the years before World War I, he founded the art movement, which profoundly influenced the surrealists. His ...

's metaphysical painting. Lewis was highly critical of the ideology of Surrealism, but admired the visual qualities of some Surrealist art.

During this period Lewis also produced many of his most well-known portraits, including pictures of Edith Sitwell

Dame Edith Louisa Sitwell (7 September 1887 – 9 December 1964) was a British poet and critic and the eldest of the three literary Sitwells. She reacted badly to her eccentric, unloving parents and lived much of her life with her governess ...

( 1923–1936), T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

(1938

Events

January

* January 1 – state-owned enterprise, State-owned railway networks are created by merger, in France (SNCF) and the Netherlands (Nederlandse Spoorwegen – NS).

* January 20 – King Farouk of Egypt marries Saf ...

and 1949), and Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

(1939

This year also marks the start of the World War II, Second World War, the largest and deadliest conflict in human history.

Events

Events related to World War II have a "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 1

** Coming into effect in Nazi Ger ...

). His 1938 portrait of Eliot was rejected by the selection committee of the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

for their annual exhibition and caused a furore. Augustus John

Augustus Edwin John (4 January 1878 – 31 October 1961) was a Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher. For a time he was considered the most important artist at work in Britain: Virginia Woolf remarked that by 1908 the era of John Singer Sarg ...

resigned in protest.

Second World War and North America (1941–1945)

Lewis spent theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in the United States and Canada. In 1941 in Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

he produced a series of watercolour

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour ( Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin 'water'), is a painting method"Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to the ...

fantasies centred on themes of creation, crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

and bathing.

He grew to appreciate the cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Internationalism

* World citizen, one who eschews traditional geopolitical divisions derived from national citizenship

* Cosmopolitanism, the idea that all of humanity belongs to a single moral community

* Cosmopolitan ...

and "rootless" nature of the American melting pot

A melting pot is a Monoculturalism, monocultural metaphor for a wiktionary:heterogeneous, heterogeneous society becoming more wiktionary:homogeneous, homogeneous, the different elements "melting together" with a common culture; an alternative bei ...

, declaring that the greatest advantage of being American was to have "turned one's back on race, caste

A caste is a Essentialism, fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (en ...

, and all that pertains to the rooted state." He praised the contributions of African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

to American culture, and regarded Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican muralism, mural movement in Mexican art, Mexican and international art.

Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted mural ...

, David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Alfaro Siqueiros (born José de Jesús Alfaro Siqueiros; December 29, 1896 – January 6, 1974) was a Mexican social realist painter, best known for his large public murals using the latest in equipment, materials and technique. Along with ...

and José Clemente Orozco

José Clemente Orozco (November 23, 1883 – September 7, 1949) was a Mexican caricaturist and painter, who specialized in political murals that established the Mexican Mural Renaissance together with murals by Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siquei ...

as the "best North American artists," predicting that when "the Indian culture of Mexico melts into the great American mass to the North, the Indian will probably give it its art." He returned to England in 1945.

Later life and blindness (1945–1951)

By 1951 he was completely blinded by apituitary tumour

Pituitary adenomas are tumors that occur in the pituitary gland. Most pituitary tumors are benign, approximately 35% are invasive and just 0.1% to 0.2% are carcinomas.optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual system, visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve i ...

. It ended his career as a painter, but he continued writing until his death. He published several autobiographical and critical works: ''Rude Assignment'' (1950), ''Rotting Hill'' (1951), a collection of allegorical short stories about his life in "the capital of a dying empire"; ''The Writer and the Absolute'' (1952), a book of essays on writers including George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

and André Malraux

Georges André Malraux ( ; ; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and minister of cultural affairs. Malraux's novel ''La Condition Humaine'' (''Man's Fate'') (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed ...

; and the semi-autobiographical novel ''Self Condemned'' (1954).

The BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

commissioned Lewis to complete his 1928 work ''The Childermass'', which was published as ''The Human Age'' and dramatised for the BBC Third Programme

The BBC Third Programme was a national radio station produced and broadcast from 1946 until 1967, when it was replaced by BBC Radio 3. It first went on the air on 29 September 1946 and became one of the leading cultural and intellectual forces ...

in 1955. In 1956 the Tate Gallery

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the UK ...

held a major exhibition of his work, "Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism", in the catalogue to which he declared that "Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did and said at a certain period"—a statement which brought forth a series of "Vortex Pamphlets" from his fellow ''Blast'' signatory William Roberts.

Personal life

From 1918 to 1921 Lewis lived with Iris Barry, with whom he had two children. He is said to have shown little affection for them. In 1930 Lewis married Gladys Anne Hoskins (1900–1979), who was affectionately known as Froanna. They lived together for 10 years before marrying, and never had children. Lewis did not tell all of his friends about his marriage, as he was jealous of them meeting her. Froanna modelled for some of his work, and characters in his books reflect her. Lewis was a

Lewis was a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

. He died in 1957 and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. By the time of his death he had written 40 books.

Political views

In 1931, after a visit to Berlin, Lewis published ''Hitler'', a book presenting Adolf Hitler as a "man of peace", with members of his party being threatened by communist street violence. His unpopularity among liberals and Anti-fascism, anti-fascists grew, especially after Hitler came to power in 1933. Following a second visit to Germany in 1937, Lewis changed his views and began to retract his previous political comments. He recognised the reality of Nazi treatment of Jews after a visit to Berlin in 1937. In 1939 he published an attack on antisemitism titled ''The Jews, Are They Human?'', which was favourably reviewed in ''The Jewish Chronicle''. He also published ''The Hitler Cult'' (1939), which firmly revoked his earlier support for Hitler. Politically Lewis remained an isolated figure through the 1930s. In ''Letter to Lord Byron'',W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, ...

called Lewis "that lonely old volcano of the Right." Lewis thought there was what he called a "left-wing orthodoxy" in Britain in the 1930s. He believed it was against Britain's self-interest to ally with the Soviet Union, "which the newspapers most of us read tell us has slaughtered out-of-hand, only a few years ago, millions of its better fed citizens, as well as its whole imperial family."

In ''Anglosaxony: A League that Works'' (1941), Lewis reflected on his earlier support for fascism:Fascism – once I understood it – left me colder than communism. The latter at least pretended, at the start, to have something to do with helping the helpless and making the world a more decent and sensible place. It does start from the human being and his suffering. Whereas fascism glorifies bloodshed and preaches that man should model himself upon the wolf.His sense that America and Canada lacked a British-type class structure had increased his opinion of liberal democracy, and in the same pamphlet he defends liberal democracy's respect for individual freedom against its critics on both the left and right. In ''America and Cosmic Man'' (1949) Lewis argued that Franklin D. Roosevelt, the US president from 1933 to 1945, had successfully managed to reconcile individual rights with the demands of the state.

Legacy

In recent years there has been renewed critical and biographical interest in Lewis and his work, and he is now regarded as a major British artist and writer of the twentieth century. Rugby School hosted an exhibition of his works in November 2007 to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of his death. The National Portrait Gallery (London), National Portrait Gallery in London held a major retrospective of his portraits in 2008. Two years later, held at the Fundación Juan March (Madrid, Spain), a large exhibition (''Wyndham Lewis 1882–1957'') featured a comprehensive collection of Lewis's paintings and drawings. As Tom Lubbock pointed out, it was "the retrospective that Britain has never managed to get together." In 2010 Oxford World's Classics published a critical edition of the 1928 text of ''Tarr'', edited by Scott W. Klein of Wake Forest University. The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University held an exhibition entitled "Vorticism, The Vorticists: Rebel Artists in London and New York, 1914–18" from 30 September 2010 through 2 January 2011. The exhibition then travelled to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (29 January – 15 May 2011: "I Vorticisti: Artisti ribellia a Londra e New York, 1914–1918") and then to Tate Britain under the title "The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World" between 14 June and 4 September 2011. Several readings by Lewis are collected on ''The Enemy Speaks'', an audiobook published in compact disc form in 2007 and featuring extracts from "One Way Song" and ''The Apes of God'', as well as radio talks titled "When John Bull Laughs" (1938), "A Crisis of Thought" (1947) and "The Essential Purposes of Art" (1951). A blue plaque now stands on the house in Kensington, London, where Lewis lived, No. 61 Palace Gardens Terrace.

Critical reception

In his essay "Good Bad Books"George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

presents Lewis as the exemplary writer who is cerebral without being artistic. Orwell wrote, "Enough talent to set up dozens of ordinary writers has been poured into Wyndham Lewis's so-called novels… Yet it would be a very heavy labour to read one of these books right through. Some indefinable quality, a sort of literary vitamin, which exists even in a book like [1921 melodramaA Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook In 1932 Walter Sickert sent Lewis a Telegraphy, telegram in which he said that Lewis's pencil portrait of

Rebecca West

Dame Cecily Isabel Fairfield (21 December 1892 – 15 March 1983), known as Rebecca West, or Dame Rebecca West, was a British author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. An author who wrote in many genres, West reviewed books ...

proved him to be "the greatest portraitist of this or any other time."Campbell, Peter (11 September 2008). "At the National Portrait Gallery". ''London Review of Books'', p. 12.

Anti-semitism

For many years Lewis's novels have been criticised for their satirical and hostile portrayals of Jews. ''Tarr'' was revised and republished in 1928, giving a new Jewish character a key role in making sure a duel is fought. This has been interpreted as an allegorical representation of Stab-in-the-back myth, a supposed Zionist conspiracy against the West.Ayers, David. (1992) ''Wyndham Lewis and Western Man''. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan. His literary satire ''The Apes of God'' has been interpreted similarly, because many of the characters are Jewish, including the modernist author and editor Julius Ratner, a portrait which blends antisemitic stereotype with the historical literary figures John Rodker and James Joyce. A key feature of these interpretations is that Lewis is held to have kept his conspiracy theories hidden and marginalised. Since the publication of Anthony Julius's ''T. S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism, and Literary Form'' (1995), where Lewis's antisemitism is described as "essentially trivial", this view is no longer taken seriously.Books

*'' Tarr'' (1918) (novel) *''The Caliph's Design : Architects! Where is Your Vortex?'' (1919) (essay) *''The Art of Being Ruled'' (1926) (essays) *''The Wild Body: A Soldier of Humour And Other Stories'' (1927) (short stories) *''The Lion and the Fox: The Role of the Hero in the Plays of Shakespeare'' (1927) (essays) *''Time and Western Man'' (1927) (essays) *''The Childermass'' (1928) (novel) *''Paleface: The Philosophy of the Melting Pot'' (1929) (essays) *''Satire and Fiction'' (1930) (criticism) *'' The Apes of God'' (1930) (novel) *Hitler

' (1931) (essay) *''The Diabolical Principle and the Dithyrambic Spectator'' (1931) (essays) *''Doom of Youth'' (1932) (essays) *''Filibusters in Barbary'' (1932) (travel; later republished as ''Journey into Barbary'') *''Enemy of the Stars'' (1932) (play) *''Snooty Baronet'' (1932) (novel) *''One-Way Song'' (1933) (poetry) *''Men Without Art'' (1934) (criticism) *''Left Wings over Europe; or, How to Make a War about Nothing'' (1936) (essays) *'' Blasting and Bombardiering'' (1937) (autobiography) *''The Revenge for Love'' (1937) (novel) *''Count Your Dead: They are Alive!: Or, A New War in the Making'' (1937) (essays) *''The Mysterious Mr. Bull'' (1938) *''The Jews, Are They Human?'' (1939) (essay) *''The Hitler Cult and How it Will End'' (1939) (essay) *''America, I Presume'' (1940) (travel) *''The Vulgar Streak'' (1941) (novel) *''Anglosaxony: A League that Works'' (1941) (essay) *''America and Cosmic Man'' (1949) (essay) *''Rude Assignment'' (1950) (autobiography) *''Rotting Hill'' (1951) (short stories) *''The Writer and the Absolute'' (1952) (essay) *''Self Condemned'' (1954) (novel) *''The Demon of Progress in the Arts'' (1955) (essay) *''Monstre Gai'' (1955) (novel) *''Malign Fiesta'' (1955) (novel) *''The Red Priest'' (1956) (novel) *''The Letters of Wyndham Lewis'' (1963) (letters) *''The Roaring Queen'' (1973; written 1936 but unpublished) (novel) *''Unlucky for Pringle'' (1973) (short stories) *''Mrs Duke's Million'' (1977; written 1908–10 but unpublished) (novel) *''Creatures of Habit and Creatures of Change'' (1989) (essays)

Paintings

*''The Theatre Manager'' (1909), watercolour

*''The Courtesan'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Indian Dance'' (1912), chalk and watercolour

*''Russian Madonna'' (also known as ''Russian Scene'') (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Lovers'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Mother and Child'' (1912), oil on canvas, now lost

*''The Dancers'' (study for ''Kermesse'') (1912), black ink and watercolour

*''The Theatre Manager'' (1909), watercolour

*''The Courtesan'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Indian Dance'' (1912), chalk and watercolour

*''Russian Madonna'' (also known as ''Russian Scene'') (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Lovers'' (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

*''Mother and Child'' (1912), oil on canvas, now lost

*''The Dancers'' (study for ''Kermesse'') (1912), black ink and watercolour(image

*''Composition'' (1913), pen and ink, watercolour

(image

*''Plan of War'' (1913–14), oil on canvas *''Slow Attack'' (1913–14), oil on canvas *''New York'' (1914), pen and ink, watercolour *''Argol'' (1914), pen and ink, watercolour *''The Crowd (Lewis), The Crowd'' (1914–15), oil paint and graphite on canvas

(image

*''Workshop'' (1914–15), oil on canvas

(image

*''Vorticist Composition'' (1915), gouache and chalk

(image

*''A Canadian Gun-pit'' (1919), oil on canvas

(image

*'' A Battery Shelled'' (1919), oil on canvas

(image

*''Mr Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro'' (1920–21), oil on canvas

(image

*''A Reading of Ovid (Tyros)'' (1920–21), oil on canvas

(image

*''Seated Figure'' (c. 1921

(image

*''Mrs Schiff'' (1923–24), oil on canvas

(image

*''Edith Sitwell (Lewis), Edith Sitwell'' (1923–1935), oil on canvas

(image

*''Bagdad'' (1927–28), oil on wood

(image

*''Three Veiled Figures'' (1933), oil on canvas

(image

*''Creation Myth'' (1933–1936, oil on canvas

(image

*''Red Scene'' (1933–1936), oil on canvas

(image

*''One of the Stations of the Dead'' (1933–1837), oil on canvas

(image

*''The Surrender of Barcelona'' (1934–1937), oil on canvas

(image

*''Panel for the Safe of a Great Millionaire'' (1936–37), oil on canvas

(image

*''Newfoundland'' (1936–37), oil on canvas

(image

*''Pensive Head'' (1937), oil on canvas

(image

*''Portrait of T. S. Eliot'' (1938), oil on canvas *''La Suerte'' (1938), oil on canvas

(image

*''John Macleod'' (1938), oil on canva

(image

*''

Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

'' (1939), oil on canvas(image

*''Mrs R.J. Sainsbury (1940–41), oil on canvas

(image

*''A Canadian War Factory'' (1943), oil on canvas

(image

*''Nigel Tangye'' (1946), oil on canvas

(image

Notes and references

Further reading

* Ayers, David. (1992) ''Wyndham Lewis and Western Man''. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan. * Chaney, Edward (1990) "Wyndham Lewis: The Modernist as Pioneering Anti-Modernist", ''Modern Painters (magazine), Modern Painters'' (Autumn, 1990), III, no. 3, pp. 106–109. * Edwards, Paul. (2000) ''Wyndham Lewis, Painter and Writer''. New Haven and London: Yale U P. * Edwards, Paul and Humphreys, Richard. (2010) "Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957)". Madrid: Fundación Juan March * Gasiorek, Andrzej. (2004) ''Wyndham Lewis and Modernism'Wyndham Lewis and Modernism

Tavistock: Northcote House. * Gasiorek, Andrzej, Reeve-Tucker, Alice, and Waddell, Nathan. (2011)

Wyndham Lewis and the Cultures of Modernity

'. Aldershot: Ashgate. * Grigson, Geoffrey (1951). ''A Master of Our Time: A Study of Wyndham Lewis''. London: Methuen. * Hammer, Martin (1981) ''Out of the Vortex: Wyndham Lewis as Painter'', in ''Cencrastus'' No. 5, Summer 1981, pp. 31–33, . * Jaillant, Lise.

Rewriting Tarr Ten Years Later: Wyndham Lewis, the Phoenix Library and the Domestication of Modernism

" Journal of Wyndham Lewis Studies 5 (2014): 1–30. * Jameson, Fredric. (1979) ''Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist''. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. * Kenner, Hugh. (1954) ''Wyndham Lewis''. New York: New Directions. * Klein, Scott W. (1994) ''The Fictions of James Joyce and Wyndham Lewis: Monsters of Nature and Design.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Leavis, F.R. (1964)

"Mr. Eliot, Mr. Wyndham Lewis and Lawrence."

In ''The Common Pursuit'', New York University Press. * Michel, Walter. (1971) ''Wyndham Lewis: Paintings and Drawings''. Berkeley: University of California Press. * Meyers, Jeffrey. (1980) ''The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis.'' London and Henley: Routledge & Keegan Paul. * Morrow, Bradford and Bernard Lafourcade. (1978) ''A Bibliography of the Writings of Wyndham Lewis''. Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press. * Normand, Tom. (1993) ''Wyndham Lewis the Artist: Holding the Mirror up to Politics''. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. * O'Keeffe, Paul. (2000) ''Some Sort of Genius: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis''. London: Cape. * Orage, A.R. (1922)

"Mr. Pound and Mr. Lewis in Public."

In ''Readers and Writers (1917–1921)'', London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. * Rothenstein, John (1956)

"Wyndham Lewis."

In ''Modern English Painters. Lewis To Moore'', London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. * Rutter, Frank (1922)

"Wyndham Lewis."

In ''Some Contemporary Artists'', London: Leonard Parsons. * Rutter, Frank (1926)

''Evolution in Modern Art: A Study of Modern Painting, 1870–1925''

London: George G. Harrap. * Schenker, Daniel. (1992) ''Wyndham Lewis: Religion and Modernism''. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama Press. * Spender, Stephen (1978). ''The Thirties and After: Poetry, Politics, People (1933–1975)'', Macmillan. * Stevenson, Randall (1982), ''The Other Centenary: Wyndham Lewis, 1882–1982'', in Hearn, Sheila G. (ed.), ''Cencrastus'' No. 10, Autumn 1982, pp. 18–21, * Waddell, Nathan. (2012)

Modernist Nowheres: Politics and Utopia in Early Modernist Writing, 1900–1920

'. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. * Wagner, Geoffrey (1957)

''Wyndham Lewis: A Portrait of the Artist as the Enemy''

New Haven: Yale University Press. * Woodcock, George, ed. ''Wyndham Lewis in Canada''. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Publications, 1972.

External links

Wyndham Lewis Society

*

Wyndham Lewis

at ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' * *

Time and Western Man

' essay by Kirsty Dootson * *

' audiobook CD

at Cornell University Library

Wyndham Lewis: Self Condemned

essay in ''The Walrus'' *

Cyril J. Fox-Wyndham Lewis collection

at the University of Victoria

Wyndham Lewis collection (1945–1956)

at the University of Victoria * *

(1914) at the Poetry Foundation

Wyndham Lewis Collection

at Clara Thomas]

Archives & Special Collections

York University * Wyndham Lewis Art Collectio

1898–1949

an

1915–1977, undated

at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin {{DEFAULTSORT:Lewis, Wyndham Wyndham Lewis, 1882 births 1957 deaths 20th-century English male writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English painters Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art British artists with disabilities British Army personnel of World War I English war artists English blind people English magazine editors English male novelists English male painters English people of American descent English satirists English satirical novelists Group X People born at sea People educated at Rugby School Post-impressionist painters Royal Artillery officers Vorticists World War I artists 20th-century British war artists