Witold Pilecki on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Witold Pilecki (; 13 May 190125 May 1948), known by the codenames ''Roman Jezierski'', ''Tomasz Serafiński'', ''Druh'' and ''Witold'', was a Polish

While in various slave labor '' kommandos'' and surviving

While in various slave labor '' kommandos'' and surviving

In July 1945, Pilecki joined the

In July 1945, Pilecki joined the

File:Witold pilecki pomnik park jordana krakow.jpg, Monument to Pilecki in Kraków

File:2017 Pomnik Witolda Pileckiego w Warszawie.jpg, Monument to Witold Pilecki in Warsaw

''A Captain's Portrait Witold Pilecki – Martyr for Truth''

Freedom Publishing Books, Melbourne Australia, 2018. .

at the

Witold Pilecki's report from Auschwitz in Polish

()

() *

''The man who volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz'', a short film about Pilecki, BBC Reel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pilecki, Witold 1901 births 1948 deaths Auschwitz concentration camp prisoners Auschwitz concentration camp survivors Auschwitz concentration camp Burials at Powązki Cemetery Commanders of the Order of Polonia Restituta Cursed soldiers killed in action Escapees from Auschwitz Executed military personnel Executed Polish people Home Army officers People executed by the Polish People's Republic by firearm People from Olonets People from Olonetsky Uyezd People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Polish Army officers Polish military personnel of World War II Polish people of the Polish–Soviet War Polish prisoners of war Polish Roman Catholics Polish Scouts and Guides Polish September Campaign participants Polish torture victims Recipients of the Auschwitz Cross Recipients of the Cross of Valour (Poland) Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Recipients of the Silver Cross of Merit (Poland) Vilnius University alumni Warsaw Uprising insurgents World War II prisoners of war held by Germany

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

cavalry officer, intelligence agent

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ''e ...

, and resistance leader.

As a youth, Pilecki joined Polish underground scouting; in the aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw far-reaching and wide-ranging cultural, economic, and social change across Europe, Asia, Africa, and in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were a ...

, he joined the Polish militia and, later, the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the Army, land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 110,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military histor ...

. He participated in the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

, which ended in 1921. In 1939, he participated in the unsuccessful defense of Poland against the invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, the Slovak Republic

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's ...

, and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Shortly afterward, he joined the Polish resistance, co-founding the Secret Polish Army resistance movement. In 1940, Pilecki volunteered to allow himself to be captured by the occupying Germans in order to infiltrate the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

. At Auschwitz, he organized a resistance movement that eventually included hundreds of inmates, and he secretly drew up reports detailing German atrocities at the camp, which were smuggled out to Home Army

The Home Army (, ; abbreviated AK) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) established in the ...

headquarters and shared with the Western Allies

Western Allies was a political and geographic grouping among the Allied Powers of the Second World War. It primarily refers to the leading Anglo-American Allied powers, namely the United States and the United Kingdom, although the term has also be ...

. After escaping from Auschwitz in April 1943, Pilecki fought in the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

of August–October 1944. Following its suppression, he was interned in a German prisoner-of-war camp. After the communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

takeover of Poland, he remained loyal to the London-based Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile (), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent Occupation ...

. In 1945, he returned to Poland to report the situation in Poland back to the government-in-exile. Before returning, Pilecki compiled his previous reports into '' Witold's Report'' to detail his Auschwitz experiences, anticipating that he might be killed by Poland's new communist authorities. In 1947, he was arrested by the secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

on charges of working for "foreign imperialism" and, after being subjected to torture and a show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

, was executed in 1948.

His story, inconvenient to the Polish communist authorities, remained mostly unknown for several decades; one of the first accounts of Pilecki's mission to Auschwitz was given by Polish historian Józef Garliński, himself a former Auschwitz inmate who emigrated to Britain after the war, in '' Fighting Auschwitz: The Resistance Movement in the Concentration Camp'' (1975). Several monographs appeared in subsequent years, particularly after the fall of communism in Poland

Autumn, also known as fall (especially in US & Canada), is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( Southern Hemispher ...

facilitated research into his life by Polish historians.

Early life and education

Witold Pilecki was born on 13 May 1901 in the town ofOlonets

Olonets (; , ; ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Olonetsky District of the Republic of Karelia, Russia, located on the Olonka River to the east of Lake Ladoga.

Geography

Olonets is located ...

, Karelia

Karelia (; Karelian language, Karelian and ; , historically Коре́ла, ''Korela'' []; ) is an area in Northern Europe of historical significance for Russia (including the Soviet Union, Soviet era), Finland, and Sweden. It is currentl ...

, in the Russian Empire. He was a descendant of a Polish-speaking noble family (szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

) of the Leliwa coat of arms

Leliwa is a Polish coat of arms. It was used by several hundred szlachta families during the existence of the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and remains in use today by many of the descendants of these families. The ...

. His ancestors had been deported to Russia from their home in Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

(former Nowogródek Voivodeship region, now in Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

) for participating in the January 1863–64 Uprising, for which a major part of their estate was confiscated. Witold was one of five children of forest inspector Julian Pilecki and Ludwika Osiecimska.

In 1910, Witold moved with his mother and siblings to Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

, to attend a Polish school there, while his father remained in Olonets. In Vilnius, Pilecki attended a local school and joined the underground Polish Scouting and Guiding Association (''Związek Harcerstwa Polskiego'', ''ZHP'').

Following the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, in 1916 Pilecki was sent by his mother to a school in the Russian city of Oryol

Oryol ( rus, Орёл, , ɐˈrʲɵl, a=ru-Орёл.ogg, links=y, ), also transliterated as Orel or Oriol, is a Classification of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast, Russia, situated on the Oka Rive ...

, located safer in the East than Vilnius. There he attended a gymnasium (secondary school) and founded a local chapter of the ''ZHP''.

Early military career

Polish–Soviet War

In 1918, following the outbreak of theRussian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

and the defeat of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

in World War I, Pilecki returned to Vilnius, then outside the control of the Polish government, and joined the ZHP section of the Self-Defence of Lithuania and Belarus, a paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

formation under Major General Władysław Wejtko. The militia disarmed the passing German troops and took up positions to defend the city from a looming attack by the Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of Peop ...

. After Vilnius fell to Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

forces on 5 January 1919, Pilecki and his unit resorted to partisan warfare behind Soviet lines. He and his comrades then retreated to Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the List of cities and towns in Poland, tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Biał ...

, where Pilecki enlisted as a '' szeregowy'' (private) in Poland's newly-established Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

. He fought in the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

of 1919–1920, serving under Captain Jerzy Dąbrowski and being involved in the Vilna offensive. He fought in the Kiev offensive (1920)

The 1920 Kiev offensive (or Kiev expedition, ) was a major part of the Polish–Soviet War. It was an attempt by the armed forces of the recently established Second Polish Republic led by Józef Piłsudski, in alliance with the Ukrainian People ...

and as part of a cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

unit defending the then-Polish city of Grodno

Grodno, or Hrodna, is a city in western Belarus. It is one of the oldest cities in Belarus. The city is located on the Neman, Neman River, from Minsk, about from the Belarus–Poland border, border with Poland, and from the Belarus–Lithua ...

. On 5 August 1920, Pilecki joined the and fought in the crucial Battle of Warsaw and then in the Rūdninkai Forest. Pilecki later was involved in the Polish–Lithuanian War as a member of the October 1920 Żeligowski's Mutiny

Żeligowski's Mutiny (, also , ) was a Polish false flag operation led by General Lucjan Żeligowski in October 1920, which resulted in the creation of the Republic of Central Lithuania. Józef Piłsudski, the Chief of State of Poland, surreptit ...

where Polish troops occupied Vilnius in a false-flag operation.

Interwar years

By the conclusion of Polish-Soviet War in March 1921, Pilecki was promoted to the rank of ''plutonowy

Plutonowy (literally ''Platoon-man'') is an Non-commissioned officer, NCO rank in the Polish Armed Forces rank insignia system, located between the ranks of Corporal, Senior Corporal and Sergeant. As one of two OR-4 ranks in the Polish Army (the o ...

'' (corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The rank is usually the lowest ranking non-commissioned officer. In some militaries, the rank of corporal nominally corr ...

), becoming a non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is an enlisted rank, enlisted leader, petty officer, or in some cases warrant officer, who does not hold a Commission (document), commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority b ...

. Shortly afterward, Pilecki was transferred to the army reserves, completing courses required for a non-commissioned officer rank at the Cavalry Reserve Officers' Training School in Grudziądz

Grudziądz (, ) is a city in northern Poland, with 92,552 inhabitants (2021). Located on the Vistula River, it lies within the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship and is the fourth-largest city in its province.

Grudziądz is one of the oldest citie ...

. He went on to complete his secondary education

Secondary education is the education level following primary education and preceding tertiary education.

Level 2 or ''lower secondary education'' (less commonly ''junior secondary education'') is considered the second and final phase of basic e ...

(''matura

or its translated terms (''mature'', ''matur'', , , , , ', ) is a Latin name for the secondary school exit exam or "maturity diploma" in various European countries, including Albania, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech ...

'') later that same year. He briefly enrolled with the Faculty of Fine Arts

Faculty or faculties may refer to:

Academia

* Faculty (academic staff), professors, researchers, and teachers of a given university or college (North American usage)

* Faculty (division), a large department of a university by field of study (us ...

at Stefan Batory University but was forced to abandon his studies in 1924 due to both financial issues and the declining health of his father. In July 1925, Pilecki was assigned to the 26th Lancer Regiment with the rank of ''Chorąży

A standard-bearer ( Polish: ''Chorąży'' ; Russian and ; , chorunžis; ) is a military rank in Poland, Ukraine and some neighboring countries. A ''chorąży'' was once a knight who bore an ensign, the emblem of an armed troops, a voivodship, a l ...

'' (ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

). Pilecki would be promoted to '' podporucznik'' (second lieutenant, with seniority from 1923) the following year. Also in September 1926, Pilecki became the owner of his family's ancestral estate, Sukurcze, in the Lida District of the Nowogródek Voivodeship. In 1931, he married . They had two children, born in Vilnius over the next two years: Andrzej and . Pilecki actively supported the local farming community. He was also an amateur poet and painter. He organized the ''Krakus'' Military Horsemen Training program in 1932 and was appointed to command the 1st Lida Military Training Squadron, which in 1937 was placed under the Polish 19th Infantry Division. In 1938, Pilecki received the Silver Cross of Merit for his activities.

World War II

Polish September Campaign

With Polish–German tensions growing in mid-1939, Pilecki was mobilized as a cavalry platoon commander on 26 August 1939. He was assigned to the 19th Infantry Division under Major General Józef Kwaciszewski, part of the Army Prusy and his unit took part in heavy fighting against the advancing Germans during theinvasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

. The 19th Division was almost completely destroyed following a clash with the German forces on the night of 5/6 September at the Battle of Piotrków Trybunalski. Its remains were incorporated into the 41st Infantry Division, which was withdrawn to the southeast toward Lwów (now Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, Ukraine) and the Romanian bridgehead. In the 41st Division, Pilecki served as divisional second-in-command of its cavalry detachment, under Major Jan Włodarkiewicz. He and his men destroyed seven German tanks, shot down one aircraft, and destroyed two more on the ground. On 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland, which worsened the already desperate situation of the Polish forces. On 22 September, the 41st Division suffered a major defeat and capitulated. Włodarkiewicz and Pilecki were among the many soldiers who did not follow the order of Commander-in-Chief General Edward Śmigły-Rydz to retreat through Romania to France, instead opting to stay underground in Poland.

Resistance

On 9 November 1939 in Warsaw, Major Włodarkiewicz, Second Lieutenant Pilecki, Second Lieutenant Jerzy Maringe, Jerzy Skoczyński, and brothers Jan and Stanisław Dangel founded the Secret Polish Army (', ''TAP''), one of the first underground organizations in Poland. Włodarkiewicz became its leader, while Pilecki became TAP's organizational head as it expanded to cover Warsaw,Siedlce

Siedlce () ( ) is a city in the Masovian Voivodeship in eastern Poland with 77,354 inhabitants ().

The city is situated between two small rivers, the Muchawka and the Helenka, and lies along the European route E30, around east of Warsaw. It is ...

, Radom

Radom is a city in east-central Poland, located approximately south of the capital, Warsaw. It is situated on the Mleczna River in the Masovian Voivodeship. Radom is the fifteenth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in its province w ...

, Lublin

Lublin is List of cities and towns in Poland, the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the centre of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin i ...

, and other major cities in central Poland. As cover, Pilecki worked as manager of a cosmetics storehouse. From 25 November 1939 until May 1940, he was TAP's inspector and chief of staff. From August 1940, he headed its 1st branch (organization and mobilization).

TAP was based on Christian ideological values. While Pilecki wanted to avert a religious mission so as not to alienate potential allies, Włodarkiewicz blamed Poland's defeat on its failure to create a Catholic nation and wanted to remake the country by appealing to right-wing groups. In the spring of 1940, Pilecki saw that Włodarkiewicz's views had become more anti-semitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

and that he had put ultranationalist

Ultranationalism, or extreme nationalism, is an extremist form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its specific ...

dogma into their newsletter, '; Włodarkiewicz had also entered into talks about a merger with the far-right underground, including a group that had offered Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

a Polish puppet government

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its ord ...

. To stop him, Pilecki went to Colonel Stefan Rowecki, chief of a rival resistance group, the Union of Armed Struggle (''Związek Walki Zbrojnej'', ''ZWZ''), which called for equal rights for Jews, gathered intelligence on German atrocities, and delivered it by courier to the Western Allies in an attempt to gain their involvement. The ZWZ had alerted the Polish Government-in-Exile that the Germans were inciting Polish hatred against the Jews, and that this might lead to the rise of a Polish Quisling

''Quisling'' (, ) is a term used in Scandinavian languages and in English to mean a citizen or politician of an occupied country who collaborates with an enemy occupying force; it may also be used more generally as a synonym for ''traitor'' or ...

.

Pilecki called for TAP to submit to Rowecki's authority, but Włodarkiewicz refused and issued a manifesto that the future Poland had to be Christian, based on national identity, and that those who opposed the idea should be "removed from our lands". Pilecki refused to swear the proposed oath. In August, Włodarkiewicz announced at a TAP meeting that they would, after all, join the mainstream underground with Rowecki – and that it has been proposed that Pilecki should infiltrate the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

. Little was known about how the Germans ran the then-new camp, which was thought to be an internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without Criminal charge, charges or Indictment, intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects ...

camp or large prison rather than a death camp. Włodarkiewicz said it was not an order but an invitation to volunteer, though Pilecki saw it as a punishment for refusing to back Włodarkiewicz's ideology. Nevertheless he agreed, which years later led to him being described in many sources as having volunteered to infiltrate Auschwitz.

Auschwitz

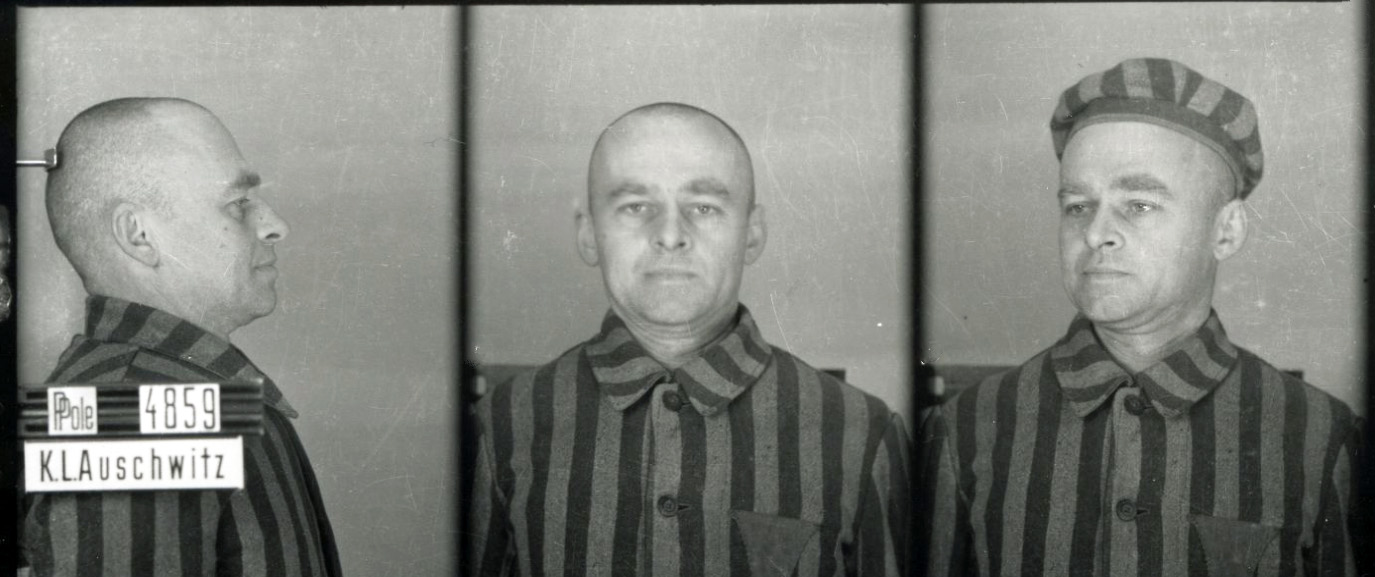

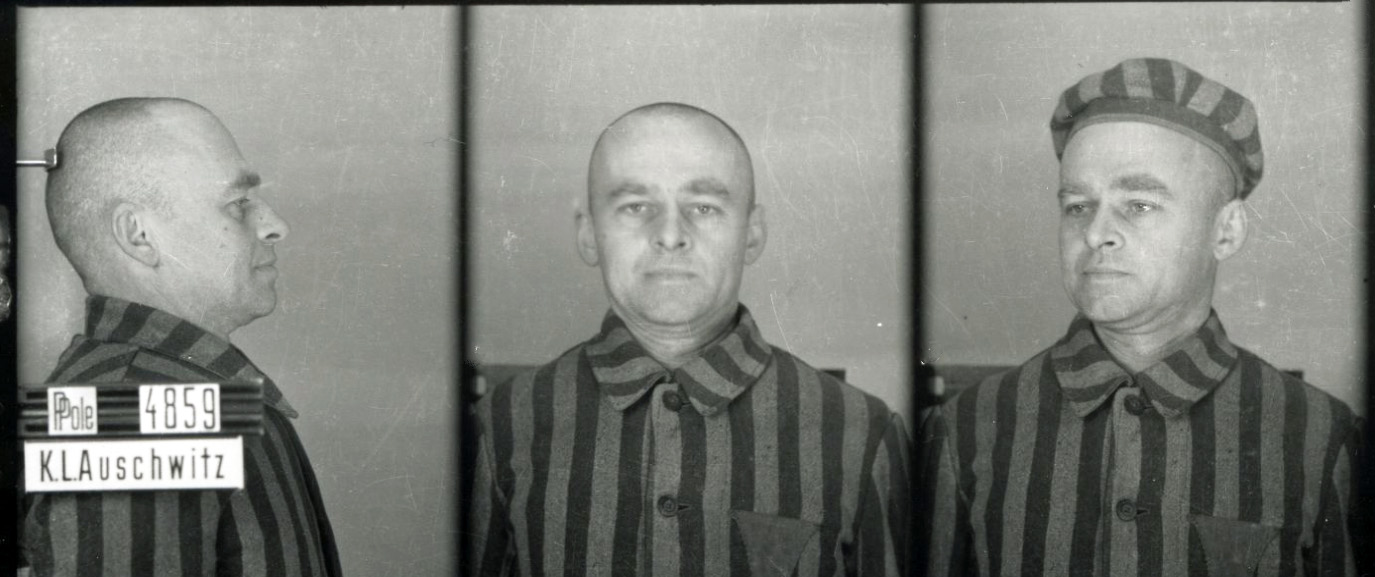

Pilecki was one of 2,000 men arrested on 19 September 1940. He used the identity documents of Tomasz Serafiński, who had been mistakenly assumed to be dead. Two backstories exist purporting to explain how Pilecki actually found himself in Auschwitz. In one version, he allowed himself to be captured by the occupying Germans in one of their Warsaw street round-ups, in order to infiltrate the camp. In the second version, he did that in the apartment of Eleonora Ostrowska, at ''ulica'' Wojska Polskiego (Polish Army Street) during a building search. Afterward, along with 1,705 other prisoners, between 21 and 22 September 1940, Pilecki reached Auschwitz where, under Serafiński's name, he was assigned prisoner number 4859. In autumn of 1941 he learnt that he had been promoted to '' porucznik'' (first lieutenant) by people "far away in the outside world in Warsaw". While in various slave labor '' kommandos'' and surviving

While in various slave labor '' kommandos'' and surviving pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

at Auschwitz, Pilecki organized an underground Military Organization Union (''Związek Organizacji Wojskowej'', ''ZOW''). Its tasks were to improve the morale of the inmates, provide news from outside the camp, distribute extra food and clothing to its members, set up intelligence networks, and train detachments to take over the camp in the event of a relief attack. ''ZOW'' was organized as secret cells, each of five members. Over time, many smaller underground organizations at Auschwitz eventually merged with ''ZOW''.

As part of his duties, Pilecki secretly drew up reports

A report is a document or a statement that presents information in an organized format for a specific audience and purpose. Although summaries of reports may be delivered orally, complete reports are usually given in the form of written documen ...

and sent them to Home Army

The Home Army (, ; abbreviated AK) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) established in the ...

headquarters with the help of inmates that had been released or escapees. The first dispatch, delivered in October 1940, described the camp and the ongoing extermination of inmates via starvation and brutal punishments; it was used as the basis of a Home Army report on "The terror and lawlessness of the occupiers". Further dispatches of Pilecki's were likewise smuggled out by inmates who managed to escape from Auschwitz. The reports' purpose may have been to get the Home Army command's permission for ''ZOW'' to stage an uprising to liberate the camp; however, no such response came from the Home Army. In 1942, Pilecki's resistance movement was also using a home-made radio transmitter to broadcast details on the number of arrivals and deaths in the camp and the conditions of the inmates. The secret radio station was built over seven months using smuggled parts. It broadcast from the camp until the autumn of 1942, when it was dismantled by Pilecki's men after concerns that the Germans might discover its location because of "one of our fellows' big mouth". The information provided by Pilecki was a principal source of intelligence on Auschwitz for the Western Allies. Pilecki hoped that either the Allies would drop arms or troops into the camp, or that the Home Army would organize an assault on it from outside.

The Camp Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

under SS-Untersturmführer Maximilian Grabner

Maximilian Grabner (2 October 1905 – 24 January 1948) was an Austrian Gestapo chief in Auschwitz. At Auschwitz he was in command of the torture chamber Block 11, where he gained a reputation of brutality. He was executed for crimes aga ...

redoubled its efforts to ferret out ''ZOW'' members, killing many of them. To avoid the worst outcome, Pilecki decided to break out of the camp with the hope of convincing Home Army leaders that a rescue attempt was a valid option. On the night of 26–27 April 1943 Pilecki was assigned to a night shift at a camp bakery outside the fence, and he and two comrades managed to force open a metal door, overpower a guard, cut the telephone line, and escape outside the camp perimeter. They left the SS guards in the woodshed, barricaded from outside. Before escaping they cut an alarm wire. They headed east, and after several hours crossed into the General Government

The General Government (, ; ; ), formally the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (), was a German zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Slovakia and the Soviet ...

, taking with them documents stolen from the Germans. The men fled on foot to the village of Alwernia where they were helped by a priest, and then on to Tyniec

Tyniec is a historic village in Poland on the Vistula river, since 1973 a part of the city of Kraków (currently in the district of Dębniki). Tyniec is notable for its Benedictine abbey founded by King Casimir the Restorer in 1044.

Etymology

...

where locals assisted them. Later, they reached the Polish resistance safe house

A safe house (also spelled safehouse) is a dwelling place or building whose unassuming appearance makes it an inconspicuous location where one can hide out, take shelter, or conduct clandestine activities.

Historical usage

It may also refer to ...

near Bochnia

Bochnia is a town on the river Raba in southern Poland, administrative seat of Bochnia County in Lesser Poland Voivodeship. The town lies approximately halfway between Tarnów (east) and the regional capital Kraków (west). Bochnia is most noted ...

, owned, coincidentally, by commander Tomasz Serafiński—the very man whose identity Pilecki had adopted for his cover in Auschwitz. At one point during the journey, German soldiers attempted to stop Pilecki, firing at him as he fled; several bullets passed through his clothing, while one wounded him without hitting either bones or vital organs.

Outside Auschwitz

After several days as a fugitive, Pilecki made contact with units of the Home Army. In June 1943, in Nowy Wiśnicz, Pilecki drafted a report on the situation in Auschwitz. It was buried at the farm where he was staying and was only revealed after his death. In August 1943, back in Warsaw, Pilecki started preparing Witold's Report (''Raport W''), which focused on the Auschwitz underground. It covered three main topics: ''ZOW'' and its members; Pilecki's experiences; and to a lesser extent, the extermination of prisoners, including Jews. Pilecki's intent in writing it was to persuade the Home Army to liberate the camp's prisoners. However, the Home Army command judged such an attack would fail. Even if the initial attack were successful, the resistance lacked sufficient transport capabilities, supplies, and the shelter that would be required for the rescued inmates. The SovietRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, despite being within attacking distance of the camp, showed no interest in a joint effort with the Home Army and the ''ZOW'' to free it.

Shortly after rejoining the resistance, Pilecki became a member of the '' Kedyw'' sabotage unit, using the pseudonym ''Roman Jezierski''. He also joined a secret anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

organization, '' NIE''. On 19 February 1944 he was promoted to cavalry captain (''rotmistrz

Rittmaster () is usually a commissioned officer military rank used in a few armies, usually equivalent to Captain. Historically it has been used in Germany, Austria-Hungary, Scandinavia, and some other countries.

A is typically in charge of a s ...

''). Until becoming involved in the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

, Pilecki continued coordinating ''ZOW'' and Home Army activities and providing ''ZOW'' with what limited support he could.

In Auschwitz, Pilecki had met the author Igor Newerly, whose Jewish wife, Barbara, was hiding in Warsaw. The Newerlys had been working with Janusz Korczak

Janusz Korczak, the pen name of Henryk Goldszmit (22 July 1878 or 1879 – 7 August 1942), was a Polish Jewish pediatrician, educator, children's author and pedagogue known as ''Pan Doktor'' ("Mr. Doctor") or ''Stary Doktor'' ("Old Doctor"). He ...

to try to save Jewish lives. Pilecki gave Barbara Newerly money from the Polish resistance, which she passed on to several Jewish families whom she and her husband protected. He also gave her money to pay off her own '' szmalcownik'', or blackmailer, who said he was Jewish and threatened to report her to the Gestapo. The blackmailer disappeared, with Jack Fairweather concluding that "it is likely that Witold arranged for his execution".

Warsaw Uprising

When the Warsaw Uprising broke out on 1 August 1944, Pilecki volunteered for service with of Kedyw's Chrobry II Battalion. Initially, he served as a common soldier in the northern city centre, without revealing his rank to his superiors. After many officers were killed in the early days of the uprising, Pilecki revealed his true identity and accepted command of the 1st "Warszawianka" Company deployed in Warsaw's '' Śródmieście'' (downtown) district. After the fall of the uprising, which ended on 2 October that year, he was captured and taken prisoner by the Germans. He was sent to Oflag VII-A, a prison-of-war camp for Polish officers located north of Murnau,Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

, where he remained until the prisoners were liberated on 29 April 1945.

After the war

In July 1945, Pilecki joined the

In July 1945, Pilecki joined the military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

division of the Polish II Corps under Lieutenant General Władysław Anders

Władysław Albert Anders (11 August 1892 – 12 May 1970) was a Polish military officer and politician, and prominent member of the Polish government-in-exile in London.

Born in Krośniewice-Błonie, then part of the Russian Empire, he serv ...

in Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

, Italy. In October 1945, as relations between the government-in-exile and the Soviet-backed regime of Bolesław Bierut

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a Polish communist activist and politician, leader of History of Poland (1945–1989), communist-ruled Poland from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council from 1944 ...

kept deteriorating, Pilecki was ordered by Anders and his intelligence chief, Lieutenant Colonel Stanisław Kijak, to return to Poland and report on the prevailing military and political situation under Soviet occupation. By December 1945 he had arrived in Warsaw and begun organizing an intelligence gathering network

An intelligence gathering network is a system through which information about a particular entity is collected for the benefit of another through the use of more than one, inter-related source. Such information may be gathered by a military inte ...

. As the NIE organization had been disbanded, Pilecki recruited former ''ZOW'' and ''TAP'' members and continued sending information to the government-in-exile.

To maintain his cover identity, Pilecki lived under various assumed names and changed jobs frequently. He worked as a jewelry salesman, a bottle label painter, and as the night manager of a construction warehouse. However, in July 1946 he was informed that his identity had been uncovered by the Ministry of Public Security

Ministry of Public Security can refer to:

* Ministry of Justice and Public Security (Brazil)

* Ministry of Public Security of Burundi

* Ministry of Public Security (Chile)

* Ministry of Public Security (China)

* Ministry of Public Security of Co ...

. Anders ordered him to leave Poland, but Pilecki was reluctant to comply because he had a family in the country and his wife was unwilling to emigrate with their children, as well as due to a lack of a suitable replacement. In early 1947, his superiors rescinded the order.

Arrested on 8 May 1947 by the communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

authorities, Pilecki was tortured, but in order to protect other operatives, he did not reveal any sensitive information. His case was supervised by Colonel Roman Romkowski. A show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

, chaired by Lieutenant Colonel , took place on 3 March 1948. Pilecki was charged with illegal border crossings, use of forged documents, failure to enlist in the military, the carrying of illegal firearms, espionage for Anders, espionage for "foreign imperialism" (government-in-exile

A government-in-exile (GiE) is a political group that claims to be the legitimate government of a sovereign state or semi-sovereign state, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile usu ...

), and assassination plots against several officials of the Ministry of Public Security. Pilecki denied the assassination charges, as well as espionage, although he admitted to passing information to the II Corps, of which he considered himself an officer and thus claimed that he was not breaking any laws. He pleaded guilty to the other charges. He was sentenced to death on 15 May with three of his comrades. Pleas for pardon from a number of Auschwitz survivors were ignored; one of their recipients was Polish prime minister Józef Cyrankiewicz

Józef Adam Zygmunt Cyrankiewicz (; 23 April 1911 – 20 January 1989) was a Polish Socialist (PPS) and after 1948 Communist politician. He served as premier of the Polish People's Republic between 1947 and 1952, and again for 16 years between 1 ...

, also an Auschwitz survivor. Cyrankiewicz, who had already testified at the trial, instead wrote that Pilecki must be treated harshly as an "enemy of the state". Subsequently, on 25 May 1948, Pilecki was executed by Piotr Śmietański with a shot to the back of the head at the Mokotów Prison

Mokotów Prison (, also known as ''Rakowiecka Prison'') is a prison in Warsaw's borough of Mokotów, Poland, located at 37 Rakowiecka Street. It was built by the Russians in the final years of the foreign Partitions of Poland. During the Nazi Ge ...

in Warsaw. Several of Pilecki's affiliates were also arrested and tried around the same time, with at least three executed as well; a number of others received death sentences that commuted to prison sentences. Pilecki's burial place has never been found, though it is thought to be in Warsaw's Powązki Cemetery

Powązki Cemetery (; ), also known as Stare Powązki (), is a historic necropolis located in Wola district, in the western part of Warsaw, Poland. It is the most famous cemetery in the city and one of the oldest, having been established in 179 ...

.

Legacy

Pilecki's life has been a subject of severalmonograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

s. The first in English was Józef Garliński's ''Fighting Auschwitz: The Resistance Movement in the Concentration Camp'' (1975), followed by M. R. D. Foot

Michael Richard Daniell Foot, (14 December 1919 – 18 February 2012) was a British political and military historian, and former British Army intelligence officer with the Special Operations Executive during the Second World War. Foot was the a ...

's ''Six Faces of Courage'' (1978). The first in Polish was the ''Rotmistrz Pilecki'' (1995) by Wiesław Jan Wysocki, followed by ''Ochotnik do Auschwitz. Witold Pilecki 1901–1948'' (2000) by Adam Cyra. In 2010, Italian historian Marco Patricelli wrote a book about Witold Pilecki, ''Il volontario'' (2010), which received the Acqui Award of History that year. In 2012, Pilecki's Auschwitz diary was translated into English by Garliński and published under the title '' The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery''. Poland's Chief Rabbi, Michael Schudrich, wrote in the foreword to a 2012 English translation of Pilecki's report: "When God created the human being, God had in mind that we should all be like Captain Witold Pilecki, of blessed memory." Historian Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a British and Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Profes ...

wrote in the introduction to the same translation: "If there was an Allied hero who deserved to be remembered and celebrated, this was a person with few peers." More recently Pilecki was the subject of Adam J. Koch's 2018 book ''A Captain’s Portrait: Witold Pilecki – Martyr for Truth'' and Jack Fairweather's 2019 book '' The Volunteer: The True Story of the Resistance Hero Who Infiltrated Auschwitz'', the latter a winner of the Costa Book Award''.''

From the 1990s, following the fall of communism in Poland

Autumn, also known as fall (especially in US & Canada), is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( Southern Hemispher ...

and Pilecki's subsequent rehabilitation, he has been a subject of popular discourse. A number of institutions, monuments, and streets in Poland have been named after him. In 1995, he was awarded the Order of Polonia Restituta

The Order of Polonia Restituta (, ) is a Polish state decoration, state Order (decoration), order established 4 February 1921. It is conferred on both military and civilians as well as on alien (law), foreigners for outstanding achievements in ...

, and in 2006, the highest Polish decoration, the Order of the White Eagle. On 6 September 2013, the Minister of National Defence announced his promotion to colonel. In 2012, Powązki Cemetery was partly excavated in an unsuccessful effort to find his remains.

In 2016, ''The Pilecki Family House Museum'' (''Dom Rodziny Pileckich'') was established in Ostrów Mazowiecka

Ostrów Mazowiecka (; ) is a town in eastern Poland with 23,486 inhabitants (2004). It is the capital of Ostrów Mazowiecka County in Masovian Voivodeship.

History

Ostrów was granted town rights in 1434 by Duke Bolesław IV of Warsaw. Its name ...

; it opened officially in 2019, but its permanent exhibition is still being prepared, with public opening planned for May 2022. The year 2017 saw the founding of the Pilecki Institute, a Polish government institution commemorating persons who helped Polish victims of war crimes and crimes against peace or humanity in the years 1917–1990.

The 2006 film ' ("The Death of Cavalry Captain Pilecki"), directed by Ryszard Bugajski, presents Pilecki as an ethically flawless man facing unfounded accusations. The narrative structure is reminiscent of a saint's martyrology

A martyrology is a catalogue or list of martyrs and other saints and beati arranged in the calendar order of their anniversaries or feasts. Local martyrologies record exclusively the custom of a particular Church. Local lists were enriched by na ...

, with belief in God replaced by belief in Country.

In 2014, the Swedish band Sabaton

A sabaton or solleret is part of a knight's body armour, body armor that covers the foot.

History

Sabatons from the 14th and 15th centuries typically end in a tapered point well past the actual toes of the wearer's foot, following poulaines, f ...

recorded a song about him, "Inmate 4859", on the album ''Heroes''.

A 2015 film, ', by Marcin Kwaśny, portrays Pilecki as an independence-movement saint. The sacralization is achieved by recounting verified historical facts, along with dramatized scenes. The film shows Pilecki performing deeds impossible for an ordinary man, while keeping faith with his country even under the direst torture.

References

Further reading

* * * Gawron, W. ''Ochotnik do Oświęcimia'' 'Volunteer for Auschwitz'' Calvarianum: Auschwitz Museum, 1992. * Adam J. Koch''A Captain's Portrait Witold Pilecki – Martyr for Truth''

Freedom Publishing Books, Melbourne Australia, 2018. .

External links

at the

Warsaw Uprising Museum

The Warsaw Rising Museum (), in the Wola district of Warsaw, Poland, is dedicated to the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. The institution of the museum was established in 1983, but no construction work took place for many years. It opened on July 31, 20 ...

Witold Pilecki's report from Auschwitz in Polish

()

() *

''The man who volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz'', a short film about Pilecki, BBC Reel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pilecki, Witold 1901 births 1948 deaths Auschwitz concentration camp prisoners Auschwitz concentration camp survivors Auschwitz concentration camp Burials at Powązki Cemetery Commanders of the Order of Polonia Restituta Cursed soldiers killed in action Escapees from Auschwitz Executed military personnel Executed Polish people Home Army officers People executed by the Polish People's Republic by firearm People from Olonets People from Olonetsky Uyezd People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Polish Army officers Polish military personnel of World War II Polish people of the Polish–Soviet War Polish prisoners of war Polish Roman Catholics Polish Scouts and Guides Polish September Campaign participants Polish torture victims Recipients of the Auschwitz Cross Recipients of the Cross of Valour (Poland) Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Recipients of the Silver Cross of Merit (Poland) Vilnius University alumni Warsaw Uprising insurgents World War II prisoners of war held by Germany