Walter Abel Heurtley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Abel Heurtley (24 October 1882 – 2 January 1955) was a British classical archaeologist. The son of a Church of England vicar, he was educated at

After the war, Heurtley moved to

After the war, Heurtley moved to

Uppingham School

Uppingham School is a public school (English fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils 13–18) in Uppingham, Rutland, England, founded in 1584 by Robert Johnson, the Archdeacon of Leicester, who also established Oakham School. ...

and read classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, commonly known as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348 by Edmund Gonville, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and ...

, on a scholarship. Upon leaving Cambridge, he worked as a teacher at The Oratory School

The Oratory School () is an HMC co-educational Private schools in the United Kingdom, private Catholic Church, Catholic boarding and day school for pupils aged 11–18 located in Woodcote, north-west of Reading, Berkshire, Reading, England. F ...

, and became a reserve officer in the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

. He served in the East Lancashire Regiment

The East Lancashire Regiment was, from 1881 to 1958, a Line infantry, line infantry regiment of the British Army. The regiment was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 30th (Cambridgeshire) Regiment of Foot and 59t ...

during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, where he was mentioned in dispatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

three times and acted as deputy governor of the British military prison at Salonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

in Greece.

After the war, Heurtley studied classical archaeology at Oriel College, Oxford

Oriel College () is Colleges of the University of Oxford, a constituent college of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. Located in Oriel Square, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title for ...

, under Percy Gardner and with Stanley Casson, the assistant director of the British School at Athens

The British School at Athens (BSA; ) is an institute for advanced research, one of the eight British International Research Institutes supported by the British Academy, that promotes the study of Greece in all its aspects. Under UK law it is a reg ...

(BSA). Heurtley followed Casson to the BSA, excavating in 1921 with him in Macedonia, and with the school's director, Alan Wace, at Mycenae. In 1923, Heurtley succeeded Casson as the BSA's assistant director, and also assumed the role of its librarian; he held both posts until his dismissal, on financial grounds, in 1932. He subsequently became the librarian of the Department of Antiquities of the Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British Empire, British administration of the territories of Mandatory Palestine, Palestine and Emirate of Transjordan, Transjordanwhich had been Ottoman Syria, part of the Ottoman ...

, a position he held until 1939, and ended his career as bursar

A bursar (derived from ''wikt:bursa, bursa'', Latin for 'Coin purse, purse') is a professional Administrator of the government, administrator in a school or university often with a predominantly financial role. In the United States, bursars usual ...

of The Oratory School.

Heurtley was elected as a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1936. He excavated widely in northern Greece during the 1920s and 1930s, and published his monograph, ''Prehistoric Macedonia'', in 1939. He also excavated on the island of Ithaca between 1930 and 1932, and spent a season at Troy

Troy (/; ; ) or Ilion (; ) was an ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey. It is best known as the setting for the Greek mythology, Greek myth of the Trojan War. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destina ...

under Carl Blegen

Carl William Blegen (January 27, 1887 – August 24, 1971) was an American archaeologist who worked at the site of Pylos in Greece and Troy in modern-day Turkey. He directed the University of Cincinnati excavations of the mound of Hisarlik, th ...

in 1932. He was often accompanied on his excavations by his wife, Eileen, who cooked for his excavators. He retired to her ancestral home in County Kerry

County Kerry () is a Counties of Ireland, county on the southwest coast of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is bordered by two other countie ...

in 1945, and died of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

in 1955.

Early life and education

Walter Abel Heurtley was born on 24 October 1882, inAshington

Ashington is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, with a population of 27,864 at the 2011 Census. It was once a centre of the coal mining industry. The town is north of Newcastle upon Tyne, west of the A189 and bordered to the ...

in Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

. His mother was Mary Elizabeth Heurtley (). His father was Charles Abel Heurtley, a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

vicar at Ashington, a descendant of French Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

, and the son of the theologian and Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

professor Charles Abel Heurtley.

Heurtley was educated at Uppingham School

Uppingham School is a public school (English fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils 13–18) in Uppingham, Rutland, England, founded in 1584 by Robert Johnson, the Archdeacon of Leicester, who also established Oakham School. ...

, a public school in Rutland

Rutland is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Leicestershire to the north and west, Lincolnshire to the north-east, and Northamptonshire to the south-west. Oakham is the largest town and county town.

Rutland has a ...

, and won a scholarship from there to read classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, commonly known as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348 by Edmund Gonville, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and ...

. He matriculated

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term ''matriculation'' is seldom used now ...

on 1 October 1902, and graduated with a second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

in 1905. He joined the part-time Volunteer Force

The Volunteer Force was a citizen army of part-time rifle, artillery and engineer corps, created as a Social movement, popular movement throughout the British Empire in 1859. Originally highly autonomous, the units of volunteers became increa ...

of the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

in 1906, as a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

. From 1907, Heurtley taught at The Oratory School

The Oratory School () is an HMC co-educational Private schools in the United Kingdom, private Catholic Church, Catholic boarding and day school for pupils aged 11–18 located in Woodcote, north-west of Reading, Berkshire, Reading, England. F ...

, a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

boarding school then based in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

.

During the First World War, Heurtley joined the East Lancashire Regiment

The East Lancashire Regiment was, from 1881 to 1958, a Line infantry, line infantry regiment of the British Army. The regiment was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 30th (Cambridgeshire) Regiment of Foot and 59t ...

and served in Macedonia. On 21 November 1914, he was made a temporary lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

in the regiment's ninth battalion. He rose to the rank of temporary major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

, was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

three times, and was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

in 1919 for his service, from May 1917, as deputy governor of the British military prison at Salonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

in Greece. According to A. W. Lawrence, who later knew Heurtley at the British School at Athens

The British School at Athens (BSA; ) is an institute for advanced research, one of the eight British International Research Institutes supported by the British Academy, that promotes the study of Greece in all its aspects. Under UK law it is a reg ...

(BSA), he first acquired an interest in archaeology during his time in Salonika. He relinquished the post of deputy governor in February 1919.

Archaeological career

After the war, Heurtley moved to

After the war, Heurtley moved to Oriel College, Oxford

Oriel College () is Colleges of the University of Oxford, a constituent college of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. Located in Oriel Square, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title for ...

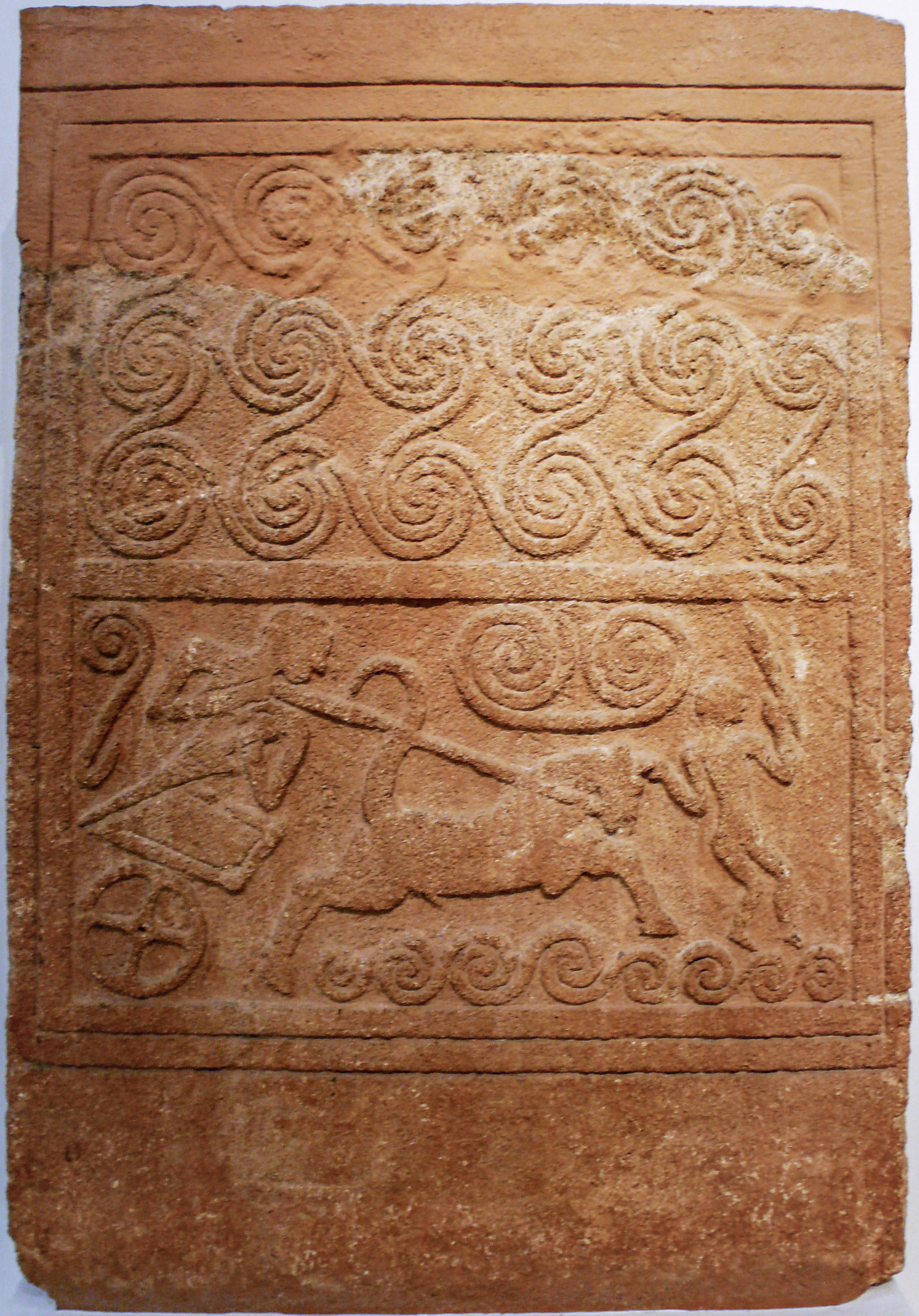

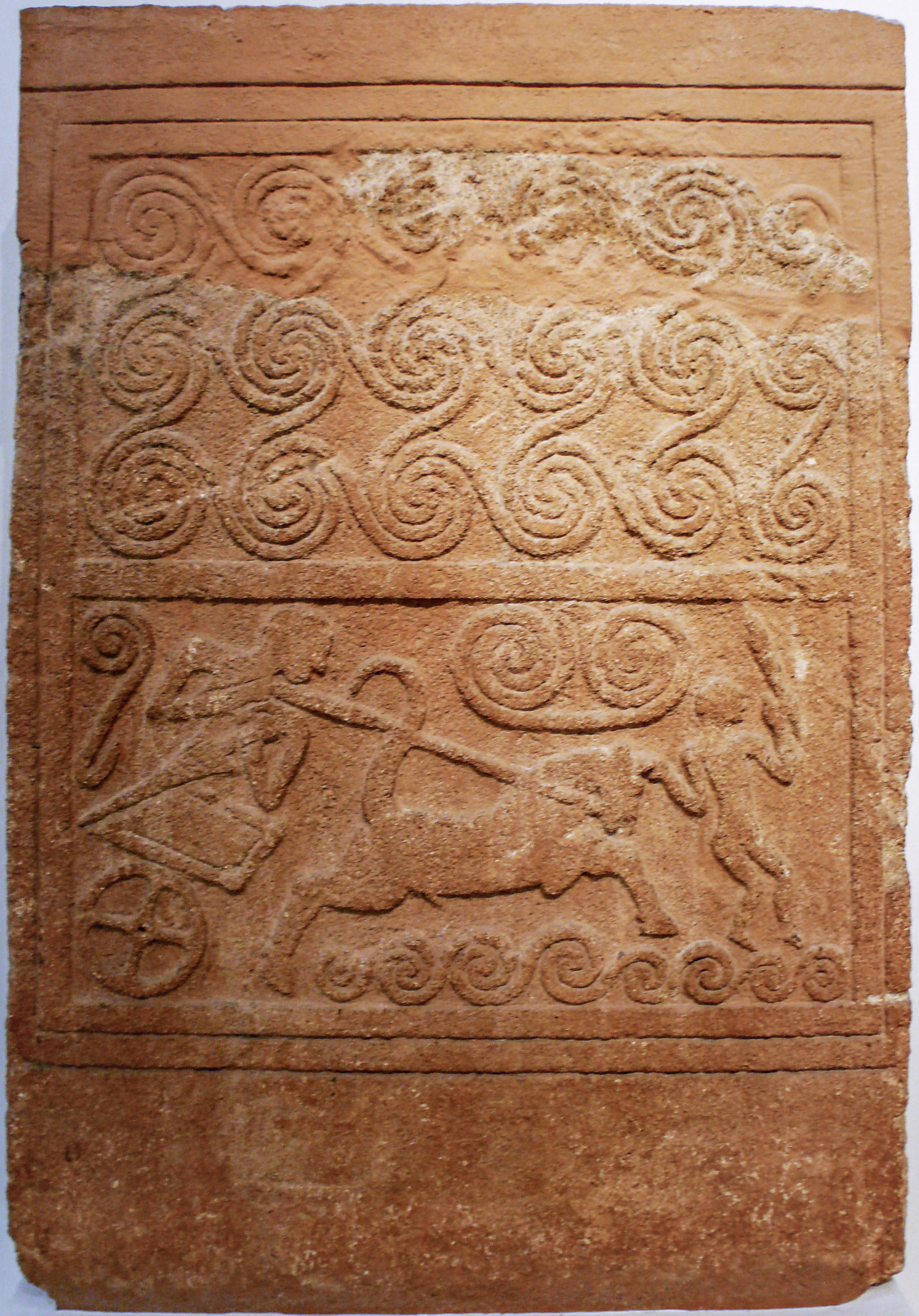

, to take a diploma in classical archaeology, studying under Percy Gardner and with Stanley Casson, the assistant director of the BSA and another former officer of the East Lancashire Regiment. Heurtley joined the BSA in 1921 on an Oxford studentship. He excavated in Macedonia with Casson in the spring of that year, at the site of Chauchitza, which had been discovered and hastily studied in December 1917 during the construction of wartime dugouts. Later in 1921, he joined the excavations of the BSA's director, Alan Wace, at the Bronze Age site of Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; ; or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines, Greece, Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos, Peloponnese, Argos; and sou ...

. At Mycenae, Heurtley worked alongside Winifred Lamb, a curator from Cambridge's Fitzwilliam Museum

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities University museum, museum of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Trumpington Street opposite Fitzwilliam Street in central Cambridge. It was founded in 1816 under the will of Richard ...

. Heurtley was tasked with preparing the initial scholarly publication of the found in the prehistoric cemetery designated Grave Circle A.

Oxford University's Craven Committee awarded Heurtley a grant to carry out excavations in Macedonia during the 1922–1923 digging season. Towards the end of the summer of 1922, Heurtley made a journey by sailboat from Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

along the southern coast of Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

and Phokis, investigating the trade routes across the Gulf of Corinth

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf (, ) is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea, separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece. It is bounded in the east by the Isthmus of Corinth which includes the shipping-designed Corinth Canal and ...

during the Mycenaean period: he later published his findings in '' The Annual of the British School at Athens''. He carried out a survey in 1923 with his fellow Craven student William Linsdell Cuttle to find possible excavation sites in western Macedonia and the Chalkidiki

Chalkidiki (; , alternatively Halkidiki), also known as Chalcidice, is a peninsula and regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the geographic region of Macedonia in Northern Greece. The autonomous Mount Athos reg ...

peninsula.

Casson resigned as the BSA's assistant director in 1922; Heurtley was the favoured choice of Wace, who felt that his experience as a schoolmaster and prison governor would be helpful in managing the school's hostel, and that Heurtley's wife Eileen would also be a "great help" in the administration of the school. Heurtley was accordingly given, in 1923, the assistant directorship and the role of librarian, on an annual salary of £200 () and free accommodation in the BSA's hostel. His work at the BSA included organising the school's collection of potsherds

This page is a glossary of archaeology, the study of the human past from material remains.

A

B

C

D

E

F

...

and responsibility for the building of a monument to the poet Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke (3 August 1887 – 23 April 1915The date of Brooke's death and burial under the Julian calendar that applied in Greece at the time was 10 April. The Julian calendar was 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar.) was an En ...

on the island of Skyros

Skyros (, ), in some historical contexts Romanization of Greek, Latinized Scyros (, ), is an island in Greece. It is the southernmost island of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC, the island was known as ...

, where Brooke had died in 1915.

Heurtley continued to excavate in Macedonia until 1931, working at sites including Servia, Kritsana and Amenochori. In June 1924, he excavated a prehistoric toumba (the local name for a tell) in the Vardar

The Vardar (; , , ) or Axios (, ) is the longest river in North Macedonia and a major river in Greece, where it reaches the Aegean Sea at Thessaloniki. It is long, out of which are in Greece, and drains an area of around . The maximum depth of ...

valley, near Karasouli. Winifred Lamb joined Heurtley's excavations at the tell of Vardaroftsa near Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

in March 1925, where the excavation team lived in tents, supported by Heurtley's wife Eileen and her sister, who cooked for them. Eileen Heurtley would accompany and cater for several of her husband's excavations throughout his career. The Vardaroftsa team included Greek-speaking refugees from Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

, resettled in Greece following the Turkish invasion of their homeland in 1922. Heurtley returned to Vardaroftsa with a smaller team, consisting of Richard Wyatt Hutchinson and William Linsdell Cuttle, in March 1926.

Among Heurtley's excavators in the 1927–1928 season in the Chalkidiki was Sylvia Benton, then a student at the BSA, who later worked with him at several Macedonian sites and at Ithaca: the archaeologist Catherine Morgan describes her as Heurtley's "protégé". In the spring of 1928, Heurtley excavated with Ralegh Radford as his assistant director at Hagios Mamas and Molyvopyrgo in the Chalkidiki, directing four students of the BSA including John Pendlebury

John Devitt Stringfellow Pendlebury (12 October 1904 – 22 May 1941) was a British archaeologist who worked for British intelligence during World War II. He was captured and Summary execution, summarily executed by German troops during the ...

. Heurtley subsequently worked at Sarátse, alongside Lamb and Benton, in March 1929. In 1930, he excavated tombs at Marmariani in Thessaly, alongside Theodore Cressy Skeat, then a student at the BSA. In the same year, he worked at Vinča-Belo Brdo

Vinča-Belo Brdo () is an archaeological site in Vinča, a suburb of Belgrade, Serbia. The Tell (archaeology), tell of Belo Brdo ('White Hill') is almost entirely made up of the remains of human settlement, and was occupied several times from th ...

in Yugoslavia, under the site's discoverer, Miloje Vasić, and on his own excavations at Ithaca, which he conducted from August to October with funding from the diplomat, poet and politician Rennell Rodd. He continued to dig at Ithaca until 1932.

The BSA announced in November 1931 that Heurtley's position as Assistant Director would be abolished, owing to financial constraints brought on by the Greek economic crisis of the early 1930s. His employment continued until the end of the summer excavation season in 1932; Heurtley worked that season at Troy

Troy (/; ; ) or Ilion (; ) was an ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey. It is best known as the setting for the Greek mythology, Greek myth of the Trojan War. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destina ...

, under the American archaeologist Carl Blegen

Carl William Blegen (January 27, 1887 – August 24, 1971) was an American archaeologist who worked at the site of Pylos in Greece and Troy in modern-day Turkey. He directed the University of Cincinnati excavations of the mound of Hisarlik, th ...

. In 1933, he took a post with the British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem and was appointed as librarian of the Department of Antiquities of the Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British Empire, British administration of the territories of Mandatory Palestine, Palestine and Emirate of Transjordan, Transjordanwhich had been Ottoman Syria, part of the Ottoman ...

, a position he held until 1939. His assistant in the library was the Palestinian intellectual Stephan Hanna Stephan. Heurtley also edited the quarterly journal of the Department of Antiquities. While in Palestine, Heurtley researched Philistine

Philistines (; Septuagint, LXX: ; ) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that the Philist ...

material culture; he argued that Philistine pottery had been manufactured in Palestine to satisfy a demand for Mycenaean-style wares among incomers displaced from the Aegean by the Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a period of societal collapse in the Mediterranean basin during the 12th century BC. It is thought to have affected much of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East, in particular Egypt, Anatolia, the Aegea ...

.

Heurtley left Palestine in 1939, and was bursar

A bursar (derived from ''wikt:bursa, bursa'', Latin for 'Coin purse, purse') is a professional Administrator of the government, administrator in a school or university often with a predominantly financial role. In the United States, bursars usual ...

of The Oratory School, by then based in Oxfordshire, during the Second World War. Following the publication of his 1939 monograph, ''Prehistoric Macedonia'', he was awarded a doctor of letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or '), also termed Doctor of Literature in some countries, is a terminal degree in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. In the United States, at universities such as Drew University, the degree ...

degree by Cambridge University in 1940. He retired in 1945, and moved to his wife's ancestral home of Derrynane House in County Kerry

County Kerry () is a Counties of Ireland, county on the southwest coast of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is bordered by two other countie ...

, Ireland. Derrynane had been the home of Daniel O'Connell

Daniel(I) O’Connell (; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilisation of Catholic Irelan ...

, the nineteenth-century Irish Catholic leader known as "the Liberator", who was Eileen Heurtley's great-grandfather.

Personal life, honours and death

Heurtley's elder brother, Archibald Charles, was born in 1872 and went up toChrist Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, to read classics in 1890; another brother, Claud, was born in 1874. Shortly before the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Heurtley travelled to County Kerry to study the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

, where he met Eileen Mary O'Connell; the two married in 1914. They had no children. Heurtley converted to Catholicism, his wife's religion: he was later accused of doing so in order to marry her, but explained his decision as a result of being impressed by the beauty of the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

churches of Austria, where he had holidayed before the First World War. When publishing the results of his excavations at Ithaca, Heurtley insisted that the word "Madonna

Madonna Louise Ciccone ( ; born August 16, 1958) is an American singer, songwriter, record producer, and actress. Referred to as the "Queen of Pop", she has been recognized for her continual reinvention and versatility in music production, ...

" be removed from the description of an ivory figurine of a monkey found at the site.

Heurtley travelled widely, both with Eileen and alone, and generally spent his summer holidays visiting museums and archaeological sites in Eastern Europe. These journeys provided material for his 1939 monograph ''Prehistoric Macedonia'', still considered current by Heurtley's biographer, Rachel Hood, in 1998. Eileen Heurtley went with her husband on one journey through the Erymanthos Valley to Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

, mostly without the aid of modern roads, though he ascended Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (, , ) is an extensive massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia, between the regional units of Larissa (regional unit), Larissa and Pieria (regional ...

and Mount Smolikas

Mount Smolikas (; ) is a mountain in the Ioannina (regional unit), Ioannina regional unit, northwestern Greece. At a height of 2,637 metres above sea level, it is the highest of the Pindus Mountains, and the second highest mountain in Greece afte ...

without her.

In 1925, Heurtley was awarded the Order of the Redeemer

The Order of the Redeemer (), also known as the Order of the Saviour, is an order of merit of Greece. The Order of the Redeemer is the oldest and highest decoration awarded by the modern Greek state.

Establishment

The establishment of the Orde ...

, Greece's highest order of merit. He also received the Order of St. Sava from Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

in 1931. He was elected as a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London

The Society of Antiquaries of London (SAL) is a learned society of historians and archaeologists in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1707, received its royal charter in 1751 and is a Charitable organization, registered charity. It is based ...

in 1936, and was also made a fellow of the German Archaeological Institute

The German Archaeological Institute (, ''DAI'') is a research institute in the field of archaeology (and other related fields). The DAI is a "federal agency" under the Federal Foreign Office, Federal Foreign Office of Germany.

Status, tasks and ...

and an honorary citizen of Stavros on Ithaca. He suffered from bouts of malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, the first in 1924, and died of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

in Dublin on 2 January 1955.

Selected works

As sole author

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *As co-author

* * * * * * *Footnotes

Explanatory notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* (Photograph of the Tomb of Aegisthus, taken by Heurtley in 1922.) * (Digital archive of Heurtley's notebooks and letters) {{DEFAULTSORT:Heurtley, Walter Abel 1882 births 1955 deaths 19th-century British archaeologists 20th-century British archaeologists British schoolteachers People educated at Uppingham School Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge Alumni of Oriel College, Oxford Archaeologists of the Bronze Age Aegean Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of London Recipients of the Order of St. Sava British classical archaeologists