Virginia v. West Virginia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Virginia v. West Virginia'', 78 U.S. (11 Wall.) 39 (1871), is a 6–3 ruling by the

The new Reorganized Governor,

The new Reorganized Governor,  The West Virginia constitutional convention had not adjourned ''sine die'' but was rather subject to recall. Every county except Webster and Monroe Counties sent representatives to the session that convened on February 12, 1863 with Abraham D. Soper as its president. After spirited debate concerning compensation for slaveowners whose slaves were freed (the matter ultimately being tabled), the convention amended the state's constitution on February 17 to include the congressionally-required slave freedom provisions and adjourned ''sine die'' on February 20.. The state's voters ratified the slave freedom amendment on March 26, 1863. On April 20, Lincoln announced that West Virginia would become a state in 60 days.

Since they were then under the military control of the Confederacy, Berkeley, Frederick, and Jefferson Counties never held votes on secession or the new West Virginia state constitution. On January 31, 1863, the

The West Virginia constitutional convention had not adjourned ''sine die'' but was rather subject to recall. Every county except Webster and Monroe Counties sent representatives to the session that convened on February 12, 1863 with Abraham D. Soper as its president. After spirited debate concerning compensation for slaveowners whose slaves were freed (the matter ultimately being tabled), the convention amended the state's constitution on February 17 to include the congressionally-required slave freedom provisions and adjourned ''sine die'' on February 20.. The state's voters ratified the slave freedom amendment on March 26, 1863. On April 20, Lincoln announced that West Virginia would become a state in 60 days.

Since they were then under the military control of the Confederacy, Berkeley, Frederick, and Jefferson Counties never held votes on secession or the new West Virginia state constitution. On January 31, 1863, the

as/nowiki> conclusive as to the result."''Virginia v. West Virginia'', 78 U.S. 39, 62. Were the votes fair and regular? The Virginia Assembly, Miller noted, made only "indefinite and vague" allegations about vote fraud, and unspecified charges that somehow, Governor Pierpont must have been "misled and deceived" by others into believing the voting was fair and regular.

Miller pointedly observed that not a single person was charged with fraud, no specific act of fraud was stated, and no legal wrongs asserted. The Virginia Assembly also did not claim that West Virginia had interfered in the elections. Absent such allegations, Virginia's accusations cannot be sustained, Miller concluded. However, even if that aspect of Virginia's argument was ignored, Miller wrote, the Reorganized legislature had delegated all its power to certify to the election to Governor Pierpont, and he had certified it. That alone laid to rest Virginia's allegations. " he/nowiki> must be bound by what she had done. She can have no right, years after all this has been settled, to come into a court of chancery to charge that her own conduct has been a wrong and a fraud; that her own subordinate agents have misled her governor, and that her solemn act transferring these counties shall be set aside, against the will of the State of West Virginia, and without consulting the wishes of the people of those counties."

When ''Virginia v. West Virginia'' first came to the Supreme Court in 1867, there were only eight Justices on the bench because of the death of Justice

When ''Virginia v. West Virginia'' first came to the Supreme Court in 1867, there were only eight Justices on the bench because of the death of Justice

/ref>

Jameson, John Alexander. ''The Constitutional Convention: Its History, Powers, and Modes of Proceeding.'' New York: C. Scribner and Co., 1867.

* * *Lesser, W. Hunter. ''Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Nation Divided.'' Naperville, Ill.: Sourcebooks, 2004. *McGregor, James C. ''The Disruption of Virginia.'' New York: MacMillan Co., 1922. * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. * *Randall, James G. ''Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln.'' Rev. ed. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1951. * *

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

that held that if a governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

has discretion in the conduct of the election, the legislature is bound by his action and cannot undo the results based on fraud. The Court implicitly affirmed that the breakaway Virginia counties had received the necessary consent of both the Commonwealth of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

to become a separate U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

. The Court also explicitly held that Berkeley County and Jefferson County were part of the new State of West Virginia.

Background

When theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

started, Virginia seceded

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal is the c ...

from the United States in 1861 over slavery, but many of the northwestern counties of Virginia were decidedly pro-Union.McPherson, ''Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era,'' 1988, p. 298. At a convention called by the governor and authorized by the legislature, delegates voted on April 17, 1861 to approve Virginia's secession from the United States.. Although the resolution required approval from voters at an election scheduled for May 23, 1861, Virginia's governor entered into a treaty of alliance with the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

on April 24, elected delegates to the Confederate Congress

The Confederate States Congress was both the provisional and permanent legislative assembly/legislature of the Confederate States of America that existed from February 1861 to April/June 1865, during the American Civil War. Its actions were, ...

on April 29, and formally entered the Confederacy on May 7. For US President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, those actions proved that rebels had taken over the state and turned the machinery of the state toward insurrection. The individuals had not acted with popular support and thus Lincoln later felt justified in recognizing the Reorganized Government.

Unionist sentiment was so high in the northwestern counties that civil government began to disintegrate, and the '' Wheeling Intelligencer'' newspaper called for a convention of delegates to meet in the city of Wheeling to consider secession from the Commonwealth of Virginia. Delegates duly assembled, and at the First Wheeling Convention (also known as the May Convention), held May 13 to 15, the delegates voted to hold off on secession from Virginia until the state had formally seceded from the United States..Randall, ''Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln,'' 1951, p. 438-439. Concerned that the irregular nature of the First Wheeling Convention might not democratically represent the will of the people, formal elections were scheduled for June 4 to elect delegates to a second convention, if necessary.

Virginians voted to approve secession on May 23. On June 4, elections were held and delegates to an elected Second Wheeling Convention. Those elections were irregular as well. Some were held under military pressure, some counties sent no delegates, some delegates never appeared, and voter turnout varied significantly.. On June 19, the Second Wheeling Convention declared the offices of all government officials who had voted for secession vacant and reconstituted the executive and legislative branches of the Virginia government from their own ranks. The Second Wheeling Convention adjourned on June 25 with the intent of reconvening on August 6..

The new Reorganized Governor,

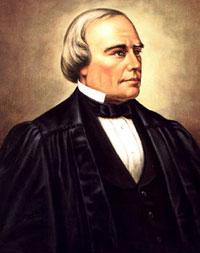

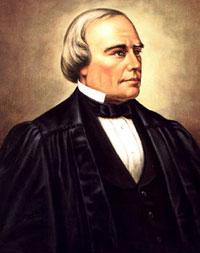

The new Reorganized Governor, Francis Harrison Pierpont

Francis Harrison Pierpont (January 25, 1814March 24, 1899), called the "Father of West Virginia," was an American lawyer and politician who achieved prominence during the American Civil War. During the conflict's first two years, Pierpont served ...

, asked Lincoln for military assistance, and Lincoln recognized the new government. The region elected new US Senators, and its two existing US Representatives took their old seats in the House, which effectively gave congressional recognition to the Reorganized Government as well.

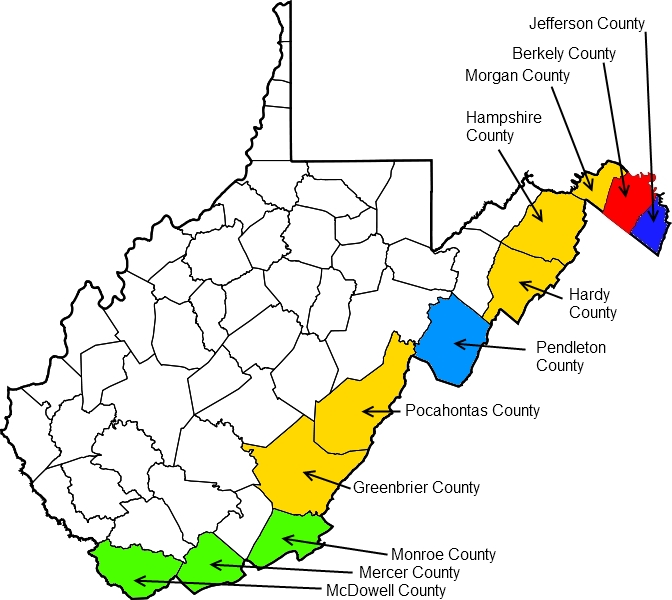

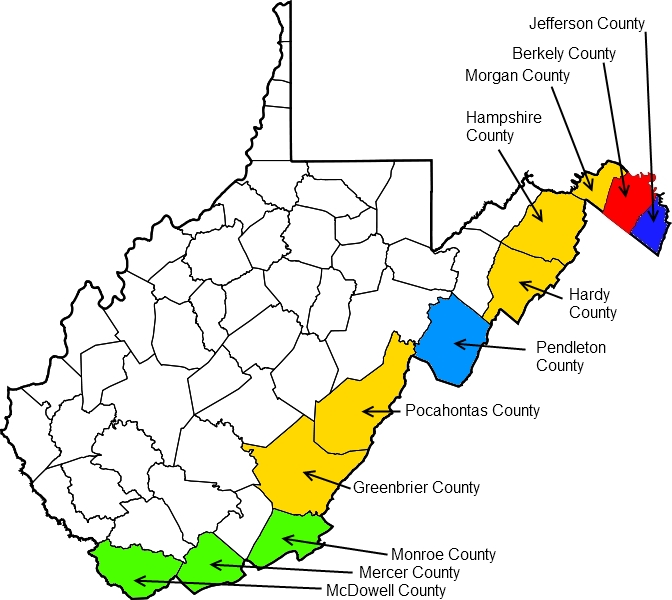

After reconvening on August 6, the Second Wheeling Convention again debated secession from Virginia. The delegates adopted a resolution authorizing the secession of 39 counties, with Berkeley, Greenbrier, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

, Hardy

Hardy may refer to:

People

* Hardy (surname)

* Hardy (given name)

* Hardy (singer), American singer-songwriter Places Antarctica

* Mount Hardy, Enderby Land

* Hardy Cove, Greenwich Island

* Hardy Rocks, Biscoe Islands

Australia

* Hardy, ...

, Jefferson, Morgan, and Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

Counties to be added if their voters approved, and it authorized any counties contiguous with them to join the new state if they so voted as well. On October 24, 1861, voters in the 39 counties, as well as voters in Hampshire and Hardy Counties, voted to secede from the Commonwealth of Virginia. In eleven counties, voter participation was less than 20%, and Raleigh

Raleigh ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most populous city in the state (after Charlotte, North Carolina, Charlotte) ...

and Braxton Counties had a voter turnout of only 5% and 2%.Curry, Richard O., ''A House Divided, Statehood Politics & The Copperhead Movement in West Virginia'', Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1964, pgs. 149-151 The ballot also allowed voters to choose delegates to a constitutional convention, which met from November 26, 1861 to February 18, 1862.

The convention chose the name "West Virginia" but then engaged in lengthy and acrimonious debate over whether to extend the state's boundaries to other counties that had not voted to secede. Added to the new state were McDowell, Mercer, and Monroe

Monroe or Monroes may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Monroe (surname)

* Monroe (given name)

* James Monroe, 5th President of the United States

* Marilyn Monroe, actress and model

Places United States

* Monroe, Arkansas, an unincorp ...

Counties.. Berkeley, Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Given name

Nobility

= Anhalt-Harzgerode =

* Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

= Austria =

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria fro ...

, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, Morgan, and Pendleton Counties were again offered the chance to join, which all but Frederick County accepted. Eight counties, Greenbrier, Logan, McDowell, Mercer, Monroe

Monroe or Monroes may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Monroe (surname)

* Monroe (given name)

* James Monroe, 5th President of the United States

* Marilyn Monroe, actress and model

Places United States

* Monroe, Arkansas, an unincorp ...

, Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

, Webster, and Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

Counties, never participated in any of the polls initiated by the Wheeling government, but they were still included in the new state. A new constitution for West Virginia was adopted on February 18, 1862 and was approved by voters on April 4..

Governor Pierpont recalled the Reorganized state legislature, which voted on May 13 to approve the secession and to include Berkeley, Frederick, and Jefferson Counties if they approved the new West Virginia constitution as well. After much debate over whether Virginia had truly given its consent to the formation of the new state, the US Congress adopted a statehood bill on July 14, 1862, which contained the proviso of freeing all blacks in the new state under the age of 21 on July 4, 1863. Lincoln was unsure of the bill's constitutionality, but pressed by northern senators, he signed the legislation on December 31, 1862.

The West Virginia constitutional convention had not adjourned ''sine die'' but was rather subject to recall. Every county except Webster and Monroe Counties sent representatives to the session that convened on February 12, 1863 with Abraham D. Soper as its president. After spirited debate concerning compensation for slaveowners whose slaves were freed (the matter ultimately being tabled), the convention amended the state's constitution on February 17 to include the congressionally-required slave freedom provisions and adjourned ''sine die'' on February 20.. The state's voters ratified the slave freedom amendment on March 26, 1863. On April 20, Lincoln announced that West Virginia would become a state in 60 days.

Since they were then under the military control of the Confederacy, Berkeley, Frederick, and Jefferson Counties never held votes on secession or the new West Virginia state constitution. On January 31, 1863, the

The West Virginia constitutional convention had not adjourned ''sine die'' but was rather subject to recall. Every county except Webster and Monroe Counties sent representatives to the session that convened on February 12, 1863 with Abraham D. Soper as its president. After spirited debate concerning compensation for slaveowners whose slaves were freed (the matter ultimately being tabled), the convention amended the state's constitution on February 17 to include the congressionally-required slave freedom provisions and adjourned ''sine die'' on February 20.. The state's voters ratified the slave freedom amendment on March 26, 1863. On April 20, Lincoln announced that West Virginia would become a state in 60 days.

Since they were then under the military control of the Confederacy, Berkeley, Frederick, and Jefferson Counties never held votes on secession or the new West Virginia state constitution. On January 31, 1863, the Restored Government of Virginia

The Restored (or Reorganized) Government of Virginia was the Unionist government of Virginia during the American Civil War (1861–1865) in opposition to the government which had approved Virginia's seceding from the United States and join ...

passed legislation authorizing the reorganized governor to hold elections in Berkeley County on whether or not to join West Virginia. The Reorganized legislature similarly approved on February 4, 1863 an election for Jefferson County and others. The elections were held, voters approved secession, and Berkeley and Jefferson Counties were admitted to West Virginia.

On December 5, 1865, the Virginia Assembly in Richmond passed legislation repealing all the acts of the reorganized government regarding secession of the 39 counties and the admission of Berkeley and Jefferson Counties to Virginia.

On March 10, 1866, Congress passed a resolution acknowledging the transfer of the two counties to West Virginia from Virginia.

Virginia sued, arguing that no action had taken place under the act of May 13, 1862, requiring elections, and that the elections in 1863 had been fraudulent and irregular. West Virginia filed a demurrer

A demurrer is a pleading in a lawsuit that objects to or challenges a pleading filed by an opposing party. The word ''demur'' means "to object"; a ''demurrer'' is the document that makes the objection. Lawyers informally define a demurrer as a ...

, which alleged that the Supreme Court lacked jurisdiction over the case because it was of a purely political nature.

Decision

Majority holding

Associate Justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

Samuel Freeman Miller

Samuel Freeman Miller (April 5, 1816 – October 13, 1890) was an American lawyer and physician who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, U.S. Supreme ...

wrote the decision for the majority, joined by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States from 1864 to his death in 1873. Chase served as the 23rd governor of Ohio from 1856 to 1860, r ...

and Associate Justices Samuel Nelson

Samuel Nelson (November 10, 1792 – December 13, 1873) was an American attorney and appointed as judge of New York State courts. He was appointed as a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1872. He concu ...

, Noah Haynes Swayne, William Strong, and Joseph P. Bradley

Joseph Philo Bradley (March 14, 1813 – January 22, 1892) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1870 to 1892. He ...

.

Justice Miller first disposed of the demurrer. He concluded that the demurrer could not be granted "without reversing the settled course of decision in this court and overturning the principles on which several well-considered cases have been decided." He noted that the court had asserted its jurisdiction in several cases before, including '' The State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations v. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts'', 37 U.S. 657 (1838); '' State of Missouri v. State of Iowa'', 48 U.S. 660 (1849); '' Florida v. Georgia'', 58 U.S. 478 (1854); and '' State of Alabama v. State of Georgia'', 64 U.S. 505 (1860).

Justice Miller then posed three questions for the Court to answer: :"1. Did the State of Virginia ever give a consent to this proposition which became obligatory on her? 2. Did the Congress give such consent as rendered the agreement valid? 3. If both these are answered affirmatively, it may be necessary to inquire whether the circumstances alleged in this bill, authorized Virginia to withdraw her consent, and justify us in setting aside the contract, and restoring the two counties to that State." Justice Miller then reviewed the various acts taken to reorganize the government of Virginia in 1861 and the various acts that the Reorganized Government and the United States took to create the state of West Virginia and extend its jurisdiction over the counties in question.

In answering the first question, Miller wrote, "Now, we have here, on two different occasions, the emphatic legislative proposition of Virginia that these counties might become part of West Virginia; and we have the constitution of West Virginia agreeing to accept them and providing for their place in the new-born State." There was no question, in the mind of the majority, that Virginia had given its consent. Although the elections had been postponed because of a "hostile" environment, the majority concluded that the Reorganized Government of Virginia had acted in "good faith" to carry out its electoral duties in the two counties.

In regard to the second question, Miller pondered the nature of congressional consent. Congress could not be expected to give its explicit consent to every single aspect of the proposed state constitution, Miller argued. Clearly, Congress had intensively considered the proposed state constitution, which contained provisions for accession of the two counties in question, because Congress had seriously considered the slavery question regarding the admission of the new state and required changes in the proposed constitution before statehood could be granted. That debate could lead the Court to only a single conclusion, Miller stated: "It is, therefore, an inference clear and satisfactory that Congress by that statute, intended to consent to the admission of the State with the contingent boundaries provided for in its constitution and in the statute of Virginia, which prayed for its admission on those terms, and that in so doing it necessarily consented to the agreement of those States on that subject. There was then a valid agreement between the two States consented to by Congress, which agreement made the accession of these counties dependent on the result of a popular vote in favor of that proposition."

Miller then considered the third question. The majority held that although the language of the two statutes of January 31, 1863 and February 4, 1863, were different, they had the same legal intent and force.''Virginia v. West Virginia'', 78 U.S. 39, 61. Virginia showed "good faith" in holding the elections, Miller asserted. That the Reorganized Virginia legislature did not require vote totals to be reported to it and delegated the transmission of the vote totals to West Virginia was not at issue, according to Miller. That gave the Reorganized Governor discretion as to when, where, and how to hold the votes to certify them. The legislature acted within its power to delegate these duties to the Reorganized Governor, "and his decision Dissenting opinion

Associate Justice David Davis wrote a dissent, joined by Associate JusticesNathan Clifford

Nathan Clifford (August 18, 1803 – July 25, 1881) was an American statesman, diplomat and jurist.

Clifford is one of the few people who have held a constitutional office in each of the three branches of the U.S. federal government. He ...

and Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field (November 4, 1816 – April 9, 1899) was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897, the second longest tenure of any justice. Prior to this ap ...

.

Davis concluded that Congress had never given its consent to the transfer of Berkeley and Jefferson Counties to West Virginia.''Virginia v. West Virginia'', 78 U.S. 39, 63. By the time that Congress did so, on March 10, 1866, the Legislature of Virginia had already withdrawn its consent to the transfer of the two counties.

Davis disagreed with the majority's view that Congress had consented to the transfer of the two counties by debating the proposed West Virginia constitution. There was nothing in the debates to ever suggest that, Davis wrote.''Virginia v. West Virginia'', 78 U.S. 39, 64. Congress agreed to that the two counties should be offered the chance to join West Virginia by the time of the new state's admission to union with the United States. The conditions had not been met by the time of admission and thus no transfer could be constitutionally made. Congress had not agreed to additional legislative acts of transfer and thus they could not be made without Virginia's assent, which had since been withdrawn.

Assessment

When ''Virginia v. West Virginia'' first came to the Supreme Court in 1867, there were only eight Justices on the bench because of the death of Justice

When ''Virginia v. West Virginia'' first came to the Supreme Court in 1867, there were only eight Justices on the bench because of the death of Justice James Moore Wayne

James Moore Wayne (1790 – July 5, 1867) was an American attorney, judge and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1835 to 1867. He previously served as the sixteenth mayor of Savanna ...

on July 5, 1867. The Court would not have nine Justices again until the resignation of Justice Robert Cooper Grier on January 31, 1870 and that year's confirmation of Justices William Strong in February and Joseph P. Bradley in March. During those three years, the Supreme Court was divided 4-4 as to whether it had jurisdiction over the case.; . Chief Justice Chase delayed taking up the case until a majority had emerged in favor of affirming the Court's original jurisdiction, rather than seeking a ruling on the issue. The acceptance of original jurisdiction in that matter is now considered one of the most significant jurisdictional cases in Supreme Court history..

It is noteworthy that former Associate Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis

Benjamin Robbins Curtis (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an American lawyer and judge who served as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1851 to 1857. Curtis was the only Whig justice of the Supreme C ...

argued unsuccessfully the case on behalf of Virginia before the Court. Curtis, as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, had dissented from the holding in '' Dred Scott v. Sandford''.

Many in Congress questioned both the legality of the Reorganized Virginia government and the constitutionality of the creation of West Virginia.Davis and Robertson, ''Virginia at War,'' Kentucky, 2005, p. 151. Many scholars since have questioned the democratic nature of the Second Wheeling Convention, the legal and moral legitimacy of the Reorganized Government, and the constitutionality of the creation of West Virginia. However, most lengthy scholarly treatments of the issue assert the legality of the Reorganized government. In '' Luther v. Borden'', 48 U.S. 1 (1849), the Supreme Court held that only the federal government could determine what constituted a "republican form of government" in a state, as provided for in the Guarantee Clause of Article Four of the United States Constitution

Article Four of the United States Constitution outlines the relationship between the various states, as well as the relationship between each state and the United States federal government. It also empowers Congress to admit new states and admi ...

.

Virginia was not alone in having two governments, one unionist, one rebel, with the union government recognized by the United States. The Supreme Court had held in ''Luther v. Borden'', "Under this article of the Constitution it rests with Congress to decide what government is the established one in a State." As both the President and Congress had recognized the Reorganized government, that provision was met and so the entire process was legal.

There were precedents for such action as well. As one legal scholar has noted, Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

was admitted to the union after irregular elections for three unauthorized constitutional conventions led to a request for statehood being eventually granted by Congress in 1837.Jameson, ''The Constitutional Convention: Its History, Powers, and Modes of Proceeding,'' 1867, p. 186-207./ref>

Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

, despite undergoing a highly irregular statehood process marked by violence, mass meetings masquerading as legislative assemblies, and allegations of vote fraud, was also admitted to the Union. One widely-cited legal analysis concluded that "the process of West Virginia statehood was hyper-legal." Indeed, denying the legality of the Reorganized government would create significant problems, two legal scholars have argued since it "follows, we submit, that 'Virginia' validly consented to the creation of West Virginia with its borders. Indeed, one can deny this conclusion only if one denies one of Lincoln's twin premises: the unlawfulness of secession; or the power of the national government, under the Guarantee Clause, to recognize alternative State governments created by loyal citizens in resistance to insurrectionary regimes that have taken over the usual governing machinery of their States."

Although the US Supreme Court never ruled on the constitutionality of the state's creation, decisions such as those in ''Virginia v. West Virginia'' have led to a ''de facto'' recognition of the state that is now considered unassailable. West Virginia's first constitution explicitly agreed to pay a portion of Virginia's debt in helping build roads, canals, railroads, and other public improvements in the new state. However, the debts were never paid, and Virginia sued to recover them. In the case, ''Virginia v. West Virginia

''Virginia v. West Virginia'', 78 U.S. (11 Wall.) 39 (1871), is a 6–3 ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that if a governor (United States), governor has discretion in the conduct of the election, the legislature is boun ...

'', 220 U.S. 1 (1911), Virginia admitted in its briefings the legality of the secession of West Virginia.Ebenroth and Kemner, "The Enduring Political Nature of Questions of State Succession and Secession and the Quest for Objective Standards," ''University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law,'' Fall 1996, p. 786-787. A second constitutional question arises as to whether the Constitution permits states to be carved out of existing states, whether consent is given or not. Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1, of the US Constitution states:

Should the phrase between the first and the second semicolons be read as absolutely barring the creation of a state within the jurisdiction of an existing state, or should it be read in conjunction with the following clause, which permits such creation with the consent of the existing state? If the former interpretation is adopted, not only West Virginia but also Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, and possibly Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

were also created unconstitutionally.

''Virginia v. West Virginia'' was also one of the first cases to establish the principle that Congress may give implied consent, which may be inferred from the context in which action was taken. It was not the first time the Court had so ruled (it had done so in '' Poole v. Fleeger'', 36 U.S. 185, (1837) and '' Green v. Biddle'', 21 U.S. 1 (1823)). However, the statement in ''Virginia v. West Virginia'' is the one most cited by the court in its subsequent rulings in '' Virginia v. Tennessee'', 148 U.S. 503 (1893); '' Wharton v. Wise'', 153 U.S. 155 (1894); '' Arizona v. California'', 292 U.S. 341 (1934); '' James v. Dravo Contracting Co.'', 302 U.S. 134 (1937); and '' De Veau v. Braisted'', 363 U.S. 144 (1960).

References

Notes Bibliography *Barnes, Johnny. "Towards Equal Footing: Responding to the Perceived Constitutional, Legal and Practical Impediments to Statehood for the District of Columbia." ''University of the District of Columbia Law Review.'' 13:1 (Spring 2010). *Cohen, Stan. ''The Civil War in West Virginia: A Pictorial History.'' Charleston, W. Va.: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1996. *Curry, Richard O. ''A House Divided, Statehood Politics & the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia'', University of Pittsburgh Press, 1964. *Davis, William C. and Robertson, James I. ''Virginia at War.'' Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 2005. *Donald, David Herbert. ''Lincoln.'' Paperback ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. *Ebenroth, Carsten Thomas and Kemner, Matthew James. "The Enduring Political Nature of Questions of State Succession and Secession and the Quest for Objective Standards." ''University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law.'' 17:753 (Fall 1996). * * * *Freehling, William W. ''The Road to Disunion: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. *Glatthaar, Joseph T. ''General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse.'' New York: Simon and Schuster, 2009. * * *Hoar, Roger Sherman. ''Constitutional Conventions: Their Nature, Powers, and Limitations.'' Littleton, Colo.: F.B. Rothman, 1987.Jameson, John Alexander. ''The Constitutional Convention: Its History, Powers, and Modes of Proceeding.'' New York: C. Scribner and Co., 1867.

* * *Lesser, W. Hunter. ''Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Nation Divided.'' Naperville, Ill.: Sourcebooks, 2004. *McGregor, James C. ''The Disruption of Virginia.'' New York: MacMillan Co., 1922. * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. * *Randall, James G. ''Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln.'' Rev. ed. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1951. * *

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Virginia v. West Virginia United States Constitution Article One case law United States Supreme Court cases United States Supreme Court cases of the Chase Court United States Constitution Article Four case law United States Supreme Court original jurisdiction cases 1871 in United States case law Internal territorial disputes of the United States Legal history of West Virginia Borders of Virginia 1871 in Virginia 1871 in West Virginia Berkeley County, West Virginia History of Jefferson County, West Virginia Borders of West Virginia