Van Buren (grape) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

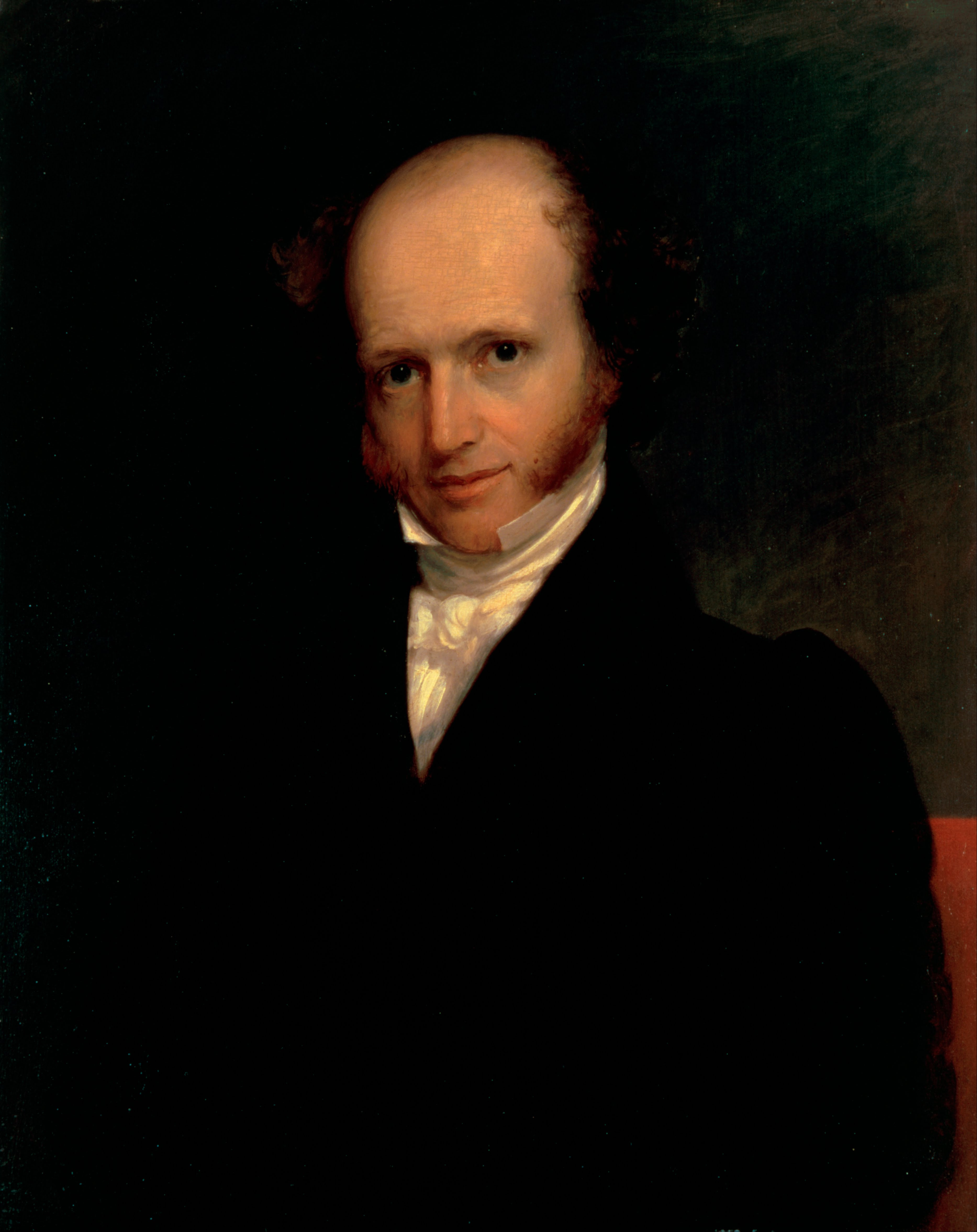

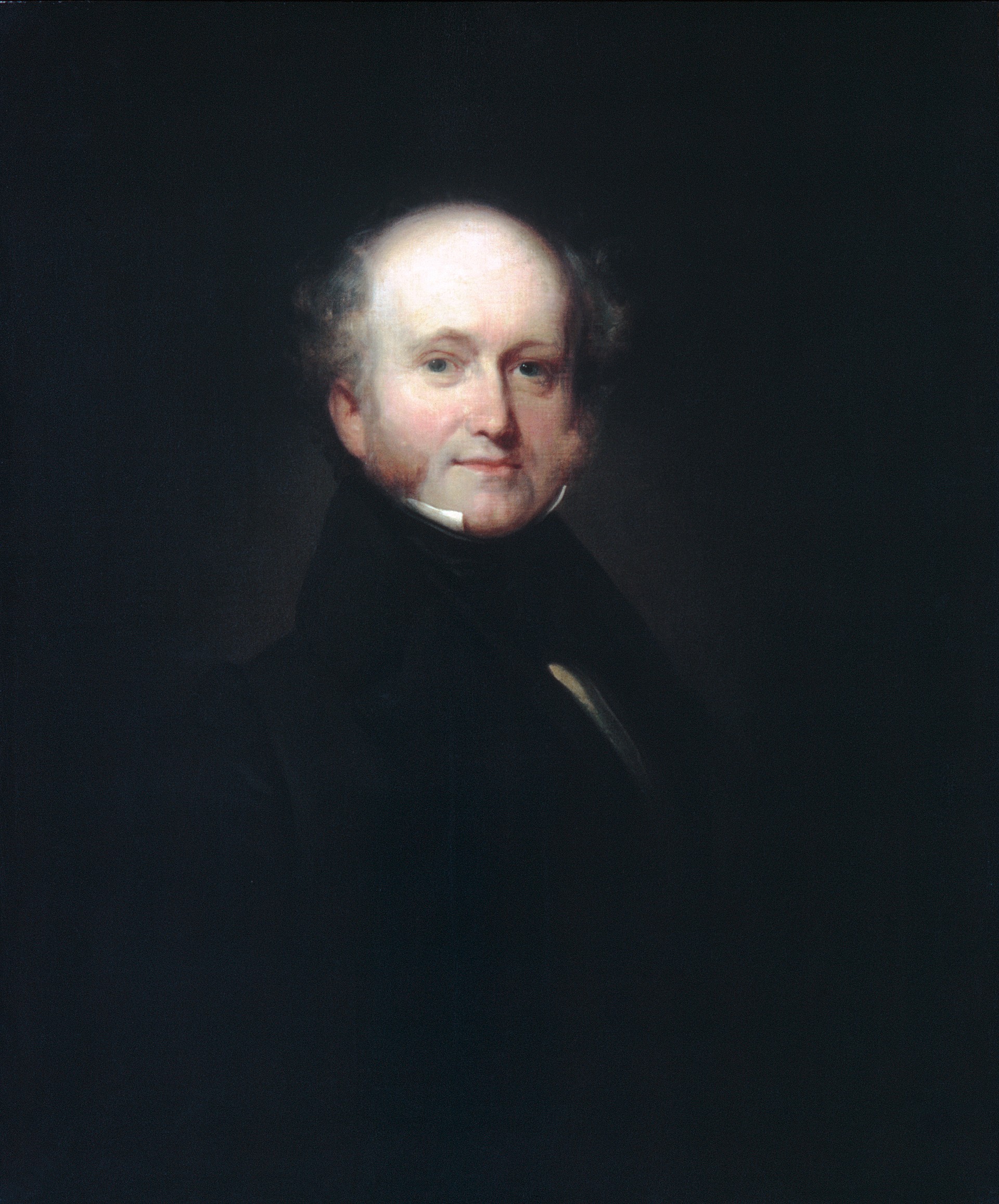

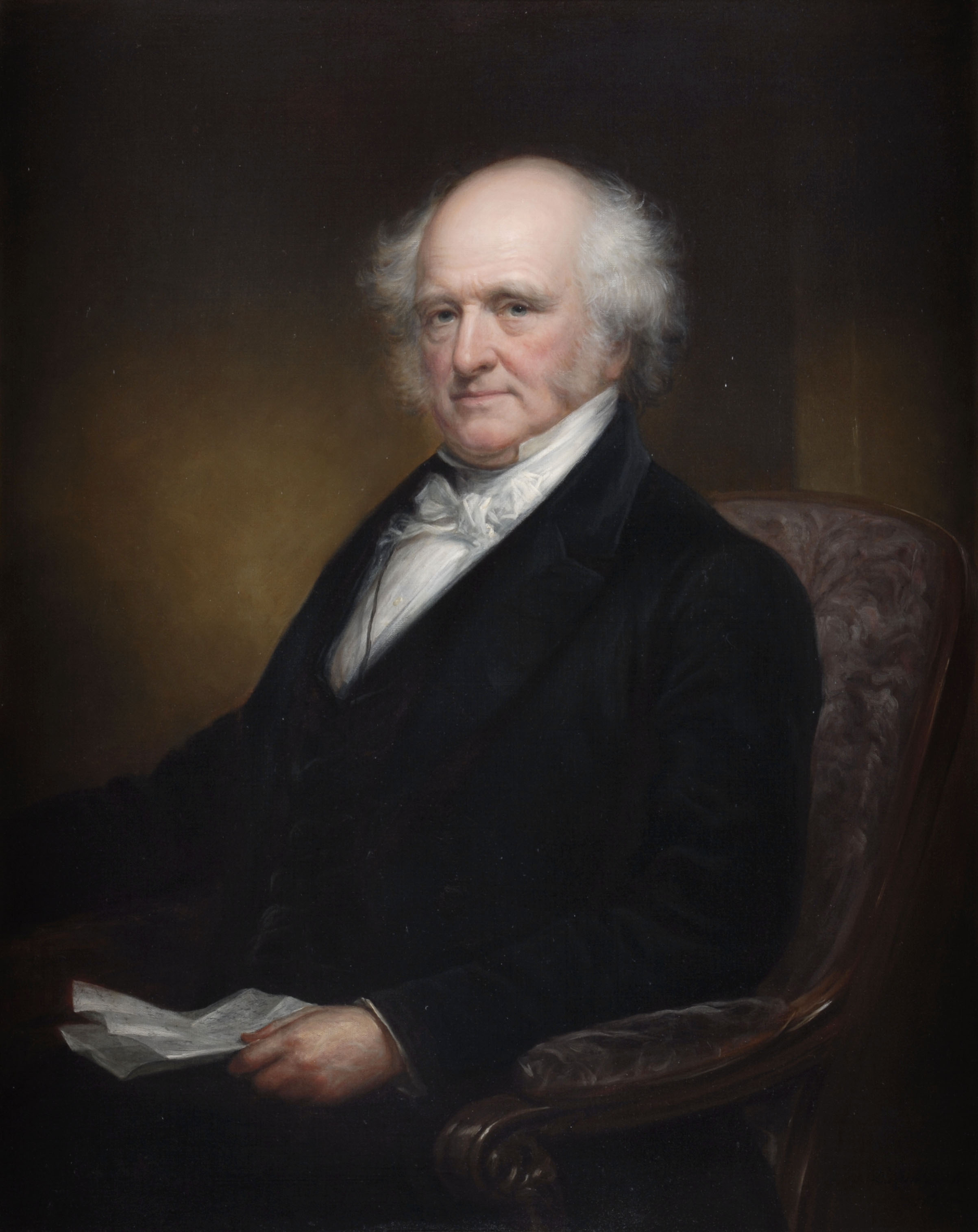

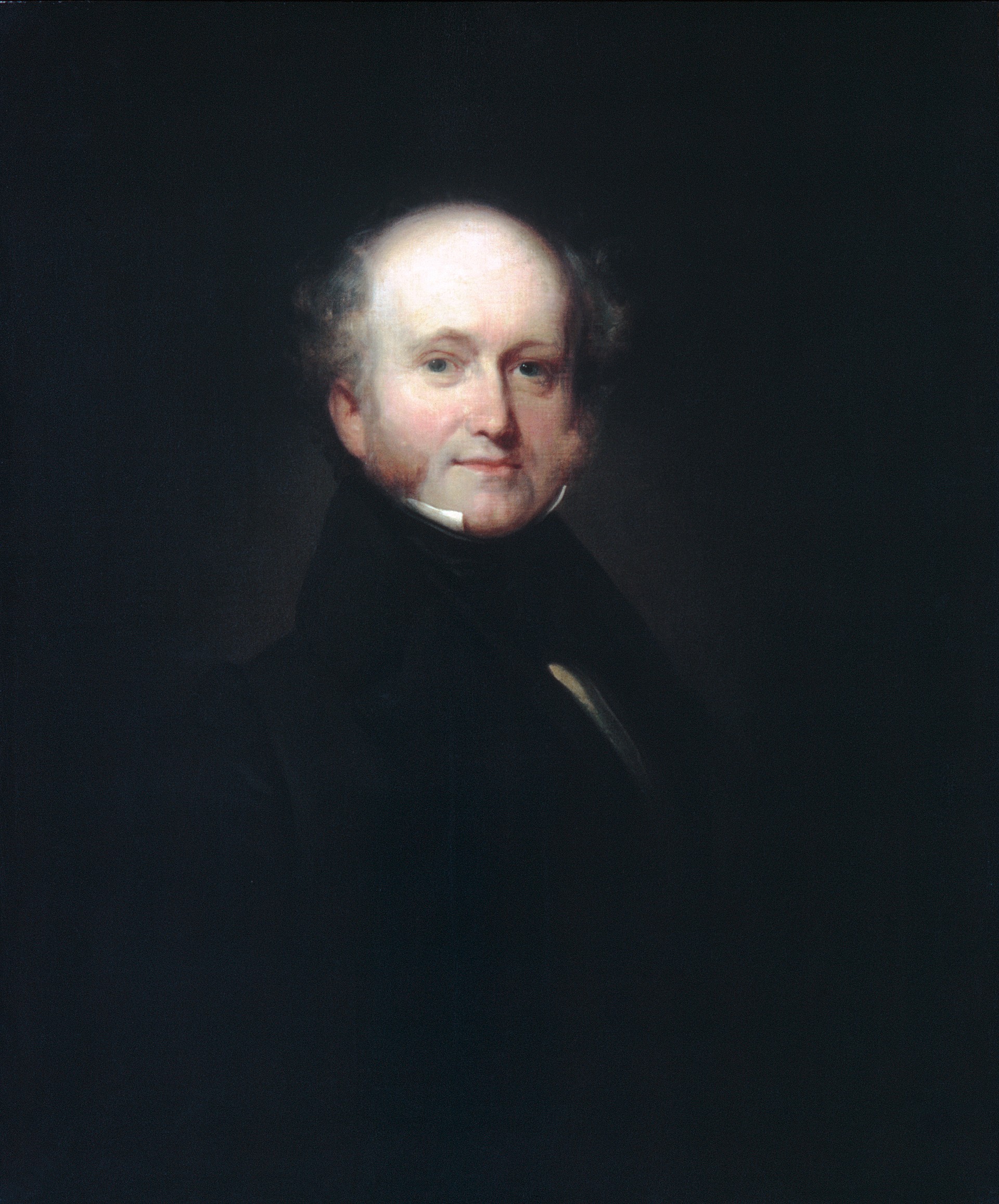

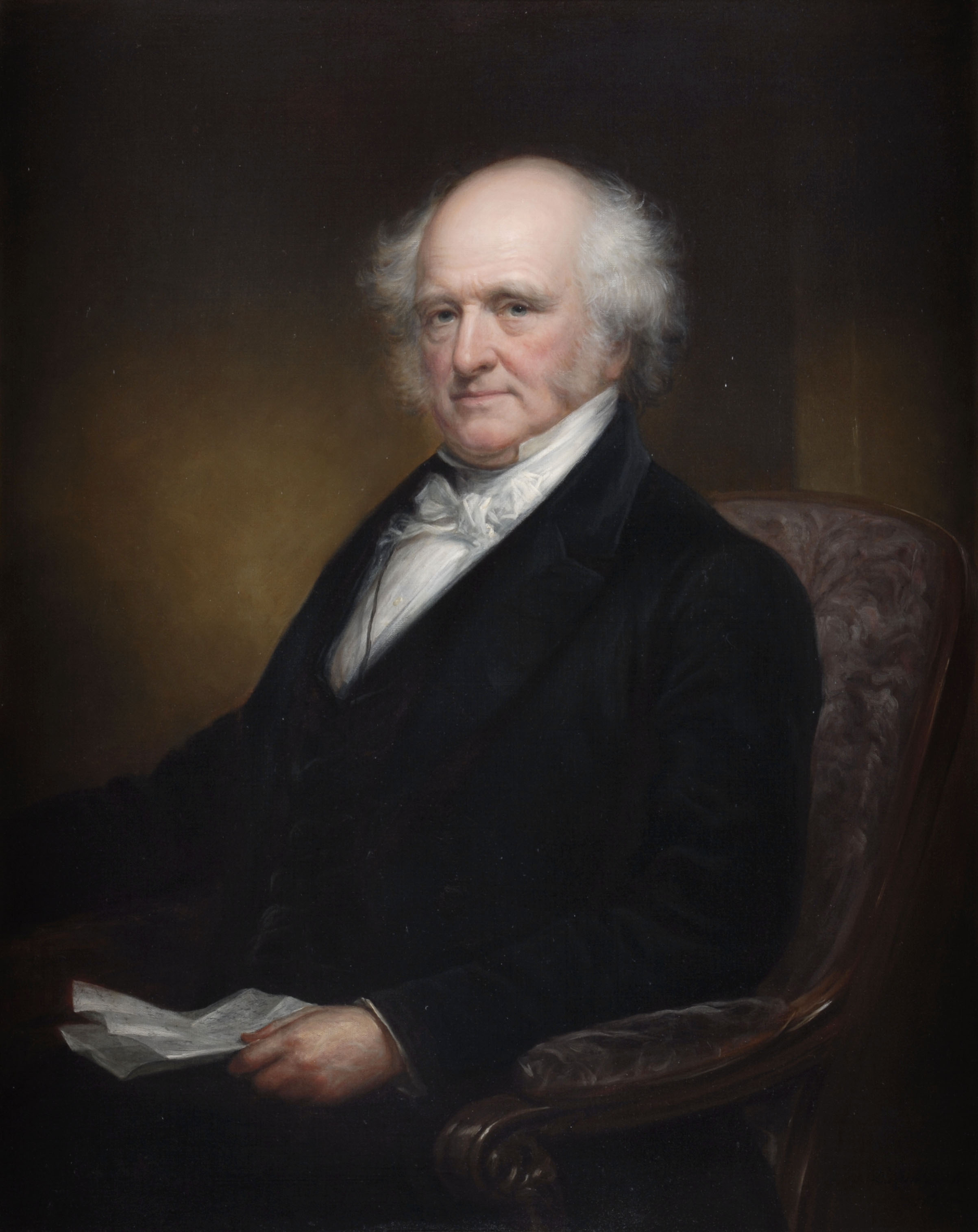

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth

Van Buren married Hannah Hoes (or Goes) in

Van Buren married Hannah Hoes (or Goes) in

Upon returning to Kinderhook in 1803, Van Buren formed a law partnership with his half-brother, James Van Alen, and became financially secure enough to increase his focus on politics. Van Buren had been active in politics from age 18, if not before. In 1801, he attended a

Upon returning to Kinderhook in 1803, Van Buren formed a law partnership with his half-brother, James Van Alen, and became financially secure enough to increase his focus on politics. Van Buren had been active in politics from age 18, if not before. In 1801, he attended a

In February 1829, Jackson wrote to Van Buren to ask him to become Secretary of State. Van Buren quickly agreed, and he resigned as governor the following month; his tenure of forty-three days is the shortest of any Governor of New York. No serious diplomatic crises arose during Van Buren's tenure as Secretary of State, but he achieved several notable successes, such as settling long-standing claims against France and winning reparations for property that had been seized during the

In February 1829, Jackson wrote to Van Buren to ask him to become Secretary of State. Van Buren quickly agreed, and he resigned as governor the following month; his tenure of forty-three days is the shortest of any Governor of New York. No serious diplomatic crises arose during Van Buren's tenure as Secretary of State, but he achieved several notable successes, such as settling long-standing claims against France and winning reparations for property that had been seized during the

In August 1831, Jackson gave Van Buren a

In August 1831, Jackson gave Van Buren a

Van Buren's competitors in the election of 1836 were three members of the Whig Party, which remained a loose coalition bound by mutual opposition to Jackson's anti-bank policies. Lacking the party unity or organizational strength to field a single ticket or define a single platform, the Whigs ran several regional candidates in hopes of sending the election to the House of Representatives. The three candidates were

Van Buren's competitors in the election of 1836 were three members of the Whig Party, which remained a loose coalition bound by mutual opposition to Jackson's anti-bank policies. Lacking the party unity or organizational strength to field a single ticket or define a single platform, the Whigs ran several regional candidates in hopes of sending the election to the House of Representatives. The three candidates were

When Van Buren entered office, the nation's economic health had taken a turn for the worse and the prosperity of the early 1830s was over. Two months into his presidency, on May 10, 1837, some important state banks in New York, running out of hard currency reserves, refused to convert paper money into gold or silver, and other financial institutions throughout the nation quickly followed suit. This

When Van Buren entered office, the nation's economic health had taken a turn for the worse and the prosperity of the early 1830s was over. Two months into his presidency, on May 10, 1837, some important state banks in New York, running out of hard currency reserves, refused to convert paper money into gold or silver, and other financial institutions throughout the nation quickly followed suit. This

The administration also contended with the

The administration also contended with the

British subjects in

British subjects in

Findlaw, accessed March 30, 2013 Van Buren viewed abolitionism as the greatest threat to the nation's unity, and he resisted the slightest interference with slavery in the states where it existed. His administration supported the Spanish government's demand that the ship and its cargo (including the Africans) be turned over to them. A federal district court judge ruled that the Africans were legally free and should be transported home, but Van Buren's administration appealed the case to the Supreme Court. In February 1840, former president

Van Buren easily won renomination for a second term at the

Van Buren easily won renomination for a second term at the

Though he had previously helped maintain a balance between the

Though he had previously helped maintain a balance between the

Van Buren never sought public office again after the 1848 election, but he continued to closely follow national politics. He was deeply troubled by the stirrings of secessionism in the South and welcomed the

Van Buren never sought public office again after the 1848 election, but he continued to closely follow national politics. He was deeply troubled by the stirrings of secessionism in the South and welcomed the  After the election of

After the election of

However, his presidency is considered to be average, at best, by historians. He was blamed for the Panic of 1837 and defeated for reelection. His tenure was dominated by the economic conditions caused by the panic, and historians have split on the adequacy of the Independent Treasury as a response. Some historians disagree with these negative assessments. For example,

However, his presidency is considered to be average, at best, by historians. He was blamed for the Panic of 1837 and defeated for reelection. His tenure was dominated by the economic conditions caused by the panic, and historians have split on the adequacy of the Independent Treasury as a response. Some historians disagree with these negative assessments. For example,

online

* * * *

online

* * * * *

online

* * Duncan, Jason K. "" Plain Catholics of the North": Martin Van Buren and the Politics of Religion, 1807–1836." ''U.S. Catholic Historian'' 38.1 (2020): 25-48. * * * Lucas, M. Philip. "Martin Van Buren as Party Leader and at Andrew Jackson's Right Hand." in ''A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861'' (2014): 107-129 * * McBride, Spencer W. "When Joseph Smith Met Martin Van Buren: Mormonism and the Politics of Religious Liberty in Nineteenth-Century America." ''Church History'' 85.1 (2016). * * Mushkat, Jerome. ''Martin Van Buren : law, politics, and the shaping of Republican ideology'' (1997

online

* * Remini, Robert V. "The Albany Regency." ''New York History'' 39.4 (1958): 341+. * * * * *

White House biography

*

Martin Van Buren: A Resource Guide

at the

The Papers of Martin Van Buren

at

The American Presidency Project – The Papers of Martin Van Buren

(Online Collection) at

American President: Martin Van Buren (1782–1862)

at the

Inaugural Address (March 4, 1837)

at the Miller Center

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site (Lindenwald)

"Life Portrait of Martin Van Buren"

from C-SPAN's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', May 3, 1999 * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Van Buren, Martin * 1782 births 1862 deaths 18th-century American people 18th-century Calvinist and Reformed Christians 19th-century American diplomats 19th-century vice presidents of the United States 19th-century Calvinist and Reformed Christians 19th-century presidents of the United States 1820 United States presidential electors 1824 United States vice-presidential candidates 1832 United States vice-presidential candidates Candidates in the 1836 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1840 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1844 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1848 United States presidential election Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law American abolitionists American members of the Dutch Reformed Church American people of Dutch descent American political party founders American slave owners Burials in New York (state) Claverack College alumni Respiratory disease deaths in New York (state) Deaths from asthma Democratic Party presidents of the United States Democratic Party governors of New York (state) Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees Democratic Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Democratic Party United States senators from New York (state) Democratic Party vice presidents of the United States Democratic-Republican Party United States senators Governors of New York (state) Jackson administration cabinet members Leaders of Tammany Hall New York State Attorneys General New York (state) Democratic-Republicans New York (state) Democrats New York (state) Free Soilers New York (state) lawyers New York (state) state senators People from Kinderhook, New York Presidents of the United States Reformed Church in America members United States Secretaries of State

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, he served as New York's attorney general, U.S. senator, then briefly as the ninth governor of New York before joining Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's administration as the tenth United States secretary of state

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, minister to the United Kingdom, and ultimately the eighth vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

when named Jackson's running mate for the 1832 election. Van Buren won the presidency in 1836

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Queen Maria II of Portugal marries Prince Ferdinand Augustus Francis Anthony of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

* January 5 – Davy Crockett arrives in Texas.

* January 12

** , with Charles Darwin on board, re ...

, lost re-election in 1840, and failed to win the Democratic nomination in 1844. Later in his life, Van Buren emerged as an elder statesman

A statesman or stateswoman typically is a politician who has had a long and respected political career at the national or international level.

Statesman or Statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

* ''The Statesman'' (Oregon), a n ...

and an important anti-slavery leader who led the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

ticket in the 1848 presidential election.

Van Buren was born in Kinderhook, New York, where most residents were of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

descent and spoke Dutch as their primary language. He was the first president to have been born after the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

— in which his father served as a patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American Revolution

* Patriot m ...

— and is the only president to have spoken English as a second language. Trained as a lawyer, he entered politics as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

, won a seat in the New York State Senate, and was elected to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

in 1821. As the leader of the Bucktails

The Bucktails (1818–1826) were the faction of the Democratic-Republican Party in New York State opposed to Governor DeWitt Clinton. It was influenced by the Tammany Society. The name derives from a Tammany insignia, a deer's tail worn in the ha ...

faction, Van Buren emerged as the most influential politician from New York in the 1820s and established a political machine known as the Albany Regency

The Albany Regency was a group of politicians who controlled the New York state government between 1822 and 1838. Originally called the "Holy Alliance", it was instituted by Martin Van Buren, who remained its dominating spirit for many years. The ...

.

Following the 1824 presidential election, Van Buren sought to re-establish a two-party system with partisan differences based on ideology rather than personalities or sectional differences; he supported Andrew Jackson's candidacy in the 1828 presidential election with this goal in mind. He ran successfully for governor of New York to support Jackson's campaign but resigned shortly after Jackson was inaugurated so he could accept appointment as Jackson's secretary of state. In the cabinet, Van Buren was a key Jackson advisor and built the organizational structure for the coalescing Democratic Party. He ultimately resigned to help resolve the Petticoat affair

The Petticoat affair (also known as the Eaton affair) was a political scandal involving members of President Andrew Jackson's Cabinet and their wives, from 1829 to 1831. Led by Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun, these wo ...

and briefly served as the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom. At Jackson's behest, the 1832 Democratic National Convention nominated Van Buren for vice president, and he took office after the Democratic ticket won the 1832 presidential election.

With Jackson's strong support and the organizational strength of the Democratic Party, Van Buren successfully ran for president in the 1836 presidential election, defeating several Whig opponents. However, his popularity soon eroded because of his response to the Panic of 1837, which centered on his Independent Treasury

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6, ...

system, a plan under which the federal government of the United States would store its funds in vaults rather than in banks; more conservative Democrats and Whigs in Congress ultimately delayed his plan from being implemented until 1840. His presidency was further marred by the costly Second Seminole War (a result of continuing Jackson's Indian removal policy); and his refusal to admit Texas to the Union as a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

as an attempt to avoid heightened sectional tensions. In 1840, Van Buren lost his re-election bid

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

to William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, the nominee of the anti- Jacksonian Whig Party.

Van Buren was initially the leading candidate for the Democratic Party's nomination again in 1844, but his continued opposition to the annexation of Texas

The Texas annexation was the 1845 annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States. Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico ...

angered Southern Democrats, leading to the nomination of James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

. Van Buren was the newly formed Free Soil Party's presidential nominee in 1848, and his candidacy helped Whig nominee Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

defeat Democrat Lewis Cass. Van Buren returned to the Democratic Party after 1848, but grew increasingly opposed to slavery, and became one of the party's outspoken abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. He supported the policies of President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, a Republican, during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. He died of asthma at his home in Kinderhook, New York, on Thursday, July 24, 1862, aged 79.

In historical rankings, historians and political scientists often rank Van Buren as an average or below-average U.S. president, due to his handling of the Panic of 1837.

Early life and education

Van Buren was born as Maarten Van Buren on December 5, 1782, in Kinderhook, New York, about south of Albany in theHudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

valley.

His father, Abraham Van Buren, was a descendant of Cornelis Maessen, a native of Buurmalsen, Netherlands who had emigrated to New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

in 1631 and purchased a plot of land on Manhattan Island. Van Buren was the first U.S President without any British ancestry. Abraham Van Buren had been a Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American Revolution

* Patriot m ...

during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, and he later joined the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

. He owned an inn and tavern in Kinderhook and served as Kinderhook's town clerk for several years. In 1776, he married Maria Hoes (or Goes) Van Alen (1746-1818) in the town of Kinderhook, also of Dutch extraction and the widow of Johannes Van Alen (1744-c. 1773). She had three children from her first marriage, including future U.S. Representative James I. Van Alen. Her second marriage produced five children, of which Martin was the third.

Van Buren received a basic education at the village schoolhouse, and briefly studied Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

at the Kinderhook Academy

Kinderhook is a Administrative divisions of New York#Town, town in the northern part of Columbia County, New York, Columbia County, New York (state), New York, United States. The population was 8,330 at the 2020 census, making it the most populous ...

and at Washington Seminary in Claverack. Van Buren was raised speaking primarily Dutch and learned English while attending school; he is the only president of the United States whose first language was not English. Also during his childhood, Van Buren learned at his father's inn how to interact with people from varied ethnic, income, and societal groups, which he used to his advantage as a political organizer. His formal education ended in 1796, when he began reading law at the office of Peter Silvester and his son Francis.

Van Buren, at tall, was small in stature, and affectionately nicknamed "Little Van". When he began his legal studies he wore rough, homespun clothing, causing the Silvesters to admonish him to pay greater heed to his clothing and personal appearance as an aspiring lawyer. He accepted their advice, and subsequently emulated the Silvesters' clothing, appearance, bearing, and conduct. The lessons he learned from the Silvesters were reflected in his career as a lawyer and politician, in which Van Buren was known for his amiability and fastidious appearance. Despite Kinderhook's strong affiliation with the Federalist Party, of which the Silvesters were also strong supporters, Van Buren adopted his father's Democratic-Republican leanings. The Silvesters and Democratic-Republican political figure John Peter Van Ness

Johannes Petrus "John Peter" Van Ness (November 4, 1769 – March 7, 1846) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative from New York from 1801 to 1803 and Mayor of Washington, D.C. from 1830 to 1834.

Early life

Van Nes ...

suggested that Van Buren's political leanings constrained him to complete his education with a Democratic-Republican attorney, so he spent a final year of apprenticeship in the New York City office of John Van Ness's brother William P. Van Ness

William Peter Van Ness (February 13, 1778 – September 6, 1826) was a United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of New York and the United States District Court for the Souther ...

, a political lieutenant of Aaron Burr. Van Ness introduced Van Buren to the intricacies of New York state politics, and Van Buren observed Burr's battles for control of the state Democratic-Republican party against George Clinton and Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

. He returned to Kinderhook in 1803, after his admission to the New York bar.

Van Buren married Hannah Hoes (or Goes) in

Van Buren married Hannah Hoes (or Goes) in Catskill, New York

Catskill is a town in the southeastern section of Greene County, New York, United States. The population was 11,298 at the 2020 census, the largest town in the county. The western part of the town is in the Catskill Park. The town contains a v ...

, on February 21, 1807. She was his childhood sweetheart, and a daughter of his maternal first cousin, Johannes Dircksen Hoes. She grew up in Valatie, and like Van Buren her home life was primarily Dutch; she spoke Dutch as her first language, and spoke English with a marked accent. The couple had six children, four of whom lived to adulthood: unnamed daughter (stillborn around 1807); Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

(1807–1873), John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

(1810–1866), Martin Jr. (1812–1855), Winfield Scott (born and died in 1814), and Smith Thompson (1817–1876). Hannah contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

, and died in Kinderhook on February 5, 1819, at age 35. Van Buren never remarried.

Early political career

Upon returning to Kinderhook in 1803, Van Buren formed a law partnership with his half-brother, James Van Alen, and became financially secure enough to increase his focus on politics. Van Buren had been active in politics from age 18, if not before. In 1801, he attended a

Upon returning to Kinderhook in 1803, Van Buren formed a law partnership with his half-brother, James Van Alen, and became financially secure enough to increase his focus on politics. Van Buren had been active in politics from age 18, if not before. In 1801, he attended a Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

convention in Troy, New York

Troy is a city in the U.S. state of New York and the county seat of Rensselaer County. The city is located on the western edge of Rensselaer County and on the eastern bank of the Hudson River. Troy has close ties to the nearby cities of Albany ...

, where he worked successfully to secure for John Peter Van Ness the party nomination in a special election for the 6th Congressional District seat. Upon returning to Kinderhook, Van Buren broke with the Burr faction, becoming an ally of both DeWitt Clinton and Daniel D. Tompkins

Daniel D. Tompkins (June 21, 1774 – June 11, 1825) was an American politician. He was the fifth governor of New York from 1807 to 1817, and the sixth vice president of the United States from 1817 to 1825.

Born in Scarsdale, New York, Tompkins ...

. After the faction led by Clinton and Tompkins dominated the 1807 elections, Van Buren was appointed Surrogate of Columbia County, New York

Columbia County is a county located in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 61,570. The county seat is Hudson. The name comes from the Latin feminine form of the name of Christopher Columbus, which was at th ...

. Seeking a better base for his political and legal career, Van Buren and his family moved to the town of Hudson, the seat of Columbia County, in 1808. Van Buren's legal practice continued to flourish, and he traveled all over the state to represent various clients.

In 1812, Van Buren won his party's nomination for a seat in the New York State Senate. Though several Democratic-Republicans, including John Peter Van Ness, joined with the Federalists to oppose his candidacy, Van Buren won election to the state senate in mid-1812. Later in the year, the United States entered the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

against Great Britain, while Clinton launched an unsuccessful bid to defeat President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

in the 1812 presidential election. After the election, Van Buren became suspicious that Clinton was working with the Federalist Party, and he broke from his former political ally.

During the War of 1812, Van Buren worked with Clinton, Governor Tompkins, and Ambrose Spencer

Ambrose Spencer (December 13, 1765March 13, 1848) was an American lawyer and politician.

Early life

Ambrose Spencer was born on December 13, 1765 in Salisbury in the Connecticut Colony. He was the son of Philip Spencer and Mary ( née Moore) S ...

to support the Madison administration's prosecution of the war. In addition, he was a special judge advocate appointed to serve as a prosecutor of William Hull

William Hull (June 24, 1753 – November 29, 1825) was an American soldier and politician. He fought in the American Revolutionary War and was appointed as Governor of Michigan Territory (1805–13), gaining large land cessions from several Am ...

during Hull's court-martial following the surrender

Surrender may refer to:

* Surrender (law), the early relinquishment of a tenancy

* Surrender (military), the relinquishment of territory, combatants, facilities, or armaments to another power

Film and television

* ''Surrender'' (1927 film), an ...

of Detroit. Anticipating another military campaign, he collaborated with Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

on ways to reorganize the New York Militia in the winter of 1814–1815, but the end of the war halted their work in early 1815. Van Buren was so favorably impressed by Scott that he named his fourth son after him. Van Buren's strong support for the war boosted his standing, and in 1815, he was elected to the position of New York Attorney General

The attorney general of New York is the chief legal officer of the U.S. state of New York and head of the Department of Law of the state government. The office has been in existence in some form since 1626, under the Dutch colonial government o ...

. Van Buren moved from Hudson to the state capital of Albany, where he established a legal partnership with Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is ...

, and shared a house with political ally Roger Skinner

Roger Skinner (June 1, 1773 – August 19, 1825) was an attorney and government official from New York. He was most notable for his service as United States district judge for the Northern District of New York from 1819 to 1825.

A native of ...

. In 1816, Van Buren won re-election to the state senate, and he would continue to simultaneously serve as both state senator and as the state's attorney general. In 1819, he played an active part in prosecuting the accused murderers of Richard Jennings, the first murder-for-hire case in the state of New York.

Albany regency

After Tompkins was elected as vice president in the 1816 presidential election, Clinton defeated Van Buren's preferred candidate,Peter Buell Porter

Peter Buell Porter (August 14, 1773 – March 20, 1844) was an American lawyer, soldier and politician who served as United States Secretary of War from 1828 to 1829.

Early life

Porter was born on August 14, 1773, one of six children born to Dr. ...

, in the 1817 New York gubernatorial election. Clinton threw his influence behind the construction of the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

, an ambitious project designed to connect Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also h ...

to the Atlantic Ocean. Though many of Van Buren's allies urged him to block Clinton's Erie Canal bill, Van Buren believed that the canal would benefit the state. His support for the bill helped it win approval from the New York legislature. Despite his support for the Erie Canal, Van Buren became the leader of an anti-Clintonian faction in New York known as the "Bucktails

The Bucktails (1818–1826) were the faction of the Democratic-Republican Party in New York State opposed to Governor DeWitt Clinton. It was influenced by the Tammany Society. The name derives from a Tammany insignia, a deer's tail worn in the ha ...

".

The Bucktails succeeded in emphasizing party loyalty and used it to capture and control many patronage posts throughout New York. Through his use of patronage, loyal newspapers, and connections with local party officials and leaders, Van Buren established what became known as the "Albany Regency

The Albany Regency was a group of politicians who controlled the New York state government between 1822 and 1838. Originally called the "Holy Alliance", it was instituted by Martin Van Buren, who remained its dominating spirit for many years. The ...

", a political machine that emerged as an important factor in New York politics. The Regency relied on a coalition of small farmers, but also enjoyed support from the Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

machine in New York City. During this era, Van Buren largely determined Tammany Hall's political policy for New York's Democratic-Republicans.

A New York state referendum that expanded state voting rights to all white men in 1821, and which further increased the power of Tammany Hall, was guided by Van Buren. Although Governor Clinton remained in office until late 1822, Van Buren emerged as the leader of the state's Democratic-Republicans after the 1820 elections. Van Buren was a member of the 1820 state constitutional convention, where he favored expanded voting rights, but opposed universal suffrage and tried to maintain property requirements for voting.

Entry into national politics

In February 1821, the state legislatureelected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

Van Buren to represent New York in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

. Van Buren arrived in Washington during the "Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fed ...

", a period in which partisan distinctions at the national level had faded. Van Buren quickly became a prominent figure in Washington, D.C., befriending Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

, among others. Though not an exceptional orator, Van Buren frequently spoke on the Senate floor, usually after extensively researching the subject at hand. Despite his commitments as a father and state party leader, Van Buren remained closely engaged in his legislative duties, and during his time in the Senate he served as the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Finance (or, less formally, Senate Finance Committee) is a standing committee of the United States Senate. The Committee concerns itself with matters relating to taxation and other revenue measures general ...

and the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

. As he gained renown, Van Buren earned monikers like "Little Magician" and "Sly Fox".

Van Buren chose to back Crawford over John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, and Henry Clay in the presidential election of 1824. Crawford shared Van Buren's affinity for Jeffersonian principles of states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

and limited government, and Van Buren believed that Crawford was the ideal figure to lead a coalition of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia's " Richmond Junto". Van Buren's support for Crawford aroused strong opposition in New York in the form of the People's party, which drew support from Clintonians, Federalists, and others opposed to Van Buren. Nonetheless, Van Buren helped Crawford win the Democratic-Republican party's presidential nomination at the February 1824 congressional nominating caucus The congressional nominating caucus is the name for informal meetings in which American congressmen would agree on whom to nominate for the Presidency and Vice Presidency from their political party.

History

The system was introduced after George W ...

. The other Democratic-Republican candidates in the race refused to accept the poorly attended caucus's decision, and as the Federalist Party had all but ceased to function as a national party, the 1824 campaign became a competition among four candidates of the same party. Though Crawford suffered a severe stroke that left him in poor health, Van Buren continued to support his chosen candidate. Van Buren met with Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

in May 1824 in an attempt to bolster Crawford's candidacy, and though he was unsuccessful in gaining a public endorsement for Crawford, he nonetheless cherished the chance to meet with his political hero.

The 1824 elections dealt a severe blow to the Albany Regency, as Clinton returned to the governorship with the support of the People's party. By the time the state legislature convened to choose the state's presidential electors

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia appo ...

, results from other states had made it clear that no individual would win a majority of the electoral vote, necessitating a contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. While Adams and Jackson finished in the top three and were eligible for selection in the contingent election, New York's electors would help determine whether Clay or Crawford would finish third. Though most of the state's electoral votes went to Adams, Crawford won one more electoral vote than Clay in the state, and Clay's defeat in Louisiana left Crawford in third place. With Crawford still in the running, Van Buren lobbied members of the House to support him. He hoped to engineer a Crawford victory on the second ballot of the contingent election, but Adams won on the first ballot with the help of Clay and Stephen Van Rensselaer, a Congressman from New York. Despite his close ties with Van Buren, Van Rensselaer cast his vote for Adams, thus giving Adams a narrow majority of New York's delegation and a victory in the contingent election.

After the House contest, Van Buren shrewdly kept out of the controversy which followed, and began looking forward to 1828. Jackson was angered to see the presidency go to Adams despite having won more popular votes than he had, and he eagerly looked forward to a rematch. Jackson's supporters accused Adams and Clay of having made a " corrupt bargain" in which Clay helped Adams win the contingent election in return for Clay's appointment as Secretary of State. Van Buren was always courteous in his treatment of opponents and showed no bitterness toward either Adams or Clay, and he voted to confirm Clay's nomination to the cabinet. At the same time, Van Buren opposed the Adams-Clay plans for internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

like roads and canals and declined to support U.S. participation in the Congress of Panama

The Congress of Panama (also referred to as the Amphictyonic Congress, in homage to the Amphictyonic League of Ancient Greece) was a congress organized by Simón Bolívar in 1826 with the goal of bringing together the new republics of Latin Americ ...

. Van Buren considered Adams's proposals to represent a return to the Hamiltonian

Hamiltonian may refer to:

* Hamiltonian mechanics, a function that represents the total energy of a system

* Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics), an operator corresponding to the total energy of that system

** Dyall Hamiltonian, a modified Hamiltonian ...

economic model favored by Federalists, which he strongly opposed. Despite his opposition to Adams's public policies, Van Buren easily secured re-election in his divided home state in 1827.

1828 elections

Van Buren's overarching goal at the national level was to restore a two-party system with party cleavages based on philosophical differences, and he viewed the old divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans as beneficial to the nation. Van Buren believed that these national parties helped ensure that elections were decided on national, rather than sectional or local, issues; as he put it, "party attachment in former times furnished a complete antidote for sectional prejudices". After the 1824 election, Van Buren was initially somewhat skeptical of Jackson, who had not taken strong positions on most policy issues. Nonetheless, he settled on Jackson as the one candidate who could beat Adams in the 1828 presidential election, and he worked to bring Crawford's former backers into line behind Jackson. He also forged alliances with other members of Congress opposed to Adams, including Vice President John C. Calhoun, Senator Thomas Hart Benton, and Senator John Randolph. Seeking to solidify his standing in New York and bolster Jackson's campaign, Van Buren helped arrange the passage of theTariff of 1828

The Tariff of 1828 was a very high protective tariff that became law in the United States in May 1828. It was a bill designed to not pass Congress because it was seen by free trade supporters as hurting both industry and farming, but surprising ...

, which opponents labeled as the "Tariff of Abominations". The tariff satisfied many who sought protection

Protection is any measure taken to guard a thing against damage caused by outside forces. Protection can be provided to physical objects, including organisms, to systems, and to intangible things like civil and political rights. Although th ...

from foreign competition, but angered Southern cotton interests and New Englanders. Because Van Buren believed that the South would never support Adams, and New England would never support Jackson, he was willing to alienate both regions through passage of the tariff.

Meanwhile, Clinton's death from a heart attack in 1828 dramatically shook up the politics of Van Buren's home state, while the Anti-Masonic Party emerged as an increasingly important factor. After some initial reluctance, Van Buren chose to run for Governor of New York in the 1828 election. Hoping that a Jackson victory would lead to his elevation to Secretary of State or Secretary of the Treasury, Van Buren chose Enos T. Throop

Enos Thompson Throop ( ; August 21, 1784 – November 1, 1874) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat who was the tenth Governor of New York from 1829 to 1832.

Early life and career

Throop was born in Johnstown, New York on August 21 ...

as his running mate and preferred successor. Van Buren's candidacy was aided by the split between supporters of Adams, who had adopted the label of National Republicans

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John Q ...

, and the Anti-Masonic Party.

Reflecting his public association with Jackson, Van Buren accepted the gubernatorial nomination on a ticket that called itself "Jacksonian-Democrat". He campaigned on local as well as national issues, emphasizing his opposition to the policies of the Adams administration. Van Buren ran ahead of Jackson, winning the state by 30,000 votes compared to a margin of 5,000 for Jackson. Nationally, Jackson defeated Adams by a wide margin, winning nearly every state outside of New England. After the election, Van Buren resigned from the Senate to start his term as governor, which began on January 1, 1829. While his term as governor was short, he did manage to pass the Bank Safety Fund Law, an early form of deposit insurance, through the legislature. He also appointed several key supporters, including William L. Marcy and Silas Wright

Silas Wright Jr. (May 24, 1795 – August 27, 1847) was an American attorney and Democratic politician. A member of the Albany Regency, he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York State Comptroller, United Stat ...

, to important state positions.

Jackson administration (1829–1837)

Secretary of State

In February 1829, Jackson wrote to Van Buren to ask him to become Secretary of State. Van Buren quickly agreed, and he resigned as governor the following month; his tenure of forty-three days is the shortest of any Governor of New York. No serious diplomatic crises arose during Van Buren's tenure as Secretary of State, but he achieved several notable successes, such as settling long-standing claims against France and winning reparations for property that had been seized during the

In February 1829, Jackson wrote to Van Buren to ask him to become Secretary of State. Van Buren quickly agreed, and he resigned as governor the following month; his tenure of forty-three days is the shortest of any Governor of New York. No serious diplomatic crises arose during Van Buren's tenure as Secretary of State, but he achieved several notable successes, such as settling long-standing claims against France and winning reparations for property that had been seized during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. He reached an agreement with the British to open trade with the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

colonies and concluded a treaty with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

that gained American merchants access to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

. Items on which he did not achieve success included settling the Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

-New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

boundary dispute with Great Britain, gaining settlement of the U.S. claim to the Oregon Country, concluding a commercial treaty with Russia, and persuading Mexico to sell Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

.

In addition to his foreign policy duties, Van Buren quickly emerged as an important advisor to Jackson on major domestic issues like the tariff and internal improvements. The Secretary of State was instrumental in convincing Jackson to issue the Maysville Road veto The Maysville Road veto occurred on May 27, 1830, when United States President Andrew Jackson vetoed a bill that would allow the federal government to purchase stock in the Maysville, Washington, Paris, and Lexington Turnpike Road Company, which had ...

, which both reaffirmed limited government principles and also helped prevent the construction of infrastructure projects that could potentially compete with New York's Erie Canal. He also became involved in a power struggle with Calhoun over appointments and other issues, including the Petticoat Affair

The Petticoat affair (also known as the Eaton affair) was a political scandal involving members of President Andrew Jackson's Cabinet and their wives, from 1829 to 1831. Led by Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun, these wo ...

. The Petticoat Affair arose because Peggy Eaton

Margaret O'Neill (or O'Neale) Timberlake Eaton (December 3, 1799 – November 8, 1879), was the wife of John Henry Eaton, a United States senator from Tennessee and United States Secretary of War, and a confidant of Andrew Jackson. Their mar ...

, wife of Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John H. Eaton, was ostracized by the other cabinet wives due to the circumstances of her marriage.

Led by Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John Calhoun, the other cabinet wives refused to pay courtesy calls to the Eatons, receive them as visitors, or invite them to social events. As a widower, Van Buren was unaffected by the position of the cabinet wives. Van Buren initially sought to mend the divide in the cabinet, but most of the leading citizens in Washington continued to snub the Eatons. Jackson was close to Eaton, and he came to the conclusion that the allegations against Eaton arose from a plot against his administration led by Henry Clay. The Petticoat Affair, combined with a contentious debate over the tariff and Calhoun's decade-old criticisms of Jackson's actions in the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

, contributed to a split between Jackson and Calhoun. As the debate over the tariff and the proposed ability of South Carolina to nullify federal law consumed Washington, Van Buren increasingly emerged as Jackson's likely successor.

The Petticoat affair was finally resolved when Van Buren offered to resign. In April 1831, Jackson accepted and reorganized his cabinet by asking for the resignations of the anti-Eaton cabinet members. Postmaster General William T. Barry

William Taylor Barry (February 5, 1784 – August 30, 1835) was an American slave owner, statesman and jurist. He served as Postmaster General for most of the administration of President Andrew Jackson and was the only Cabinet member not to resi ...

, who had sided with the Eatons in the Petticoat Affair, was the lone cabinet member to remain in office. The cabinet reorganization removed Calhoun's allies from the Jackson administration, and Van Buren had a major role in shaping the new cabinet. After leaving office, Van Buren continued to play a part in the Kitchen Cabinet

Kitchen cabinets are the built-in furniture installed in many kitchens for storage of food, cooking equipment, and often silverware and dishes for table service. Appliances such as refrigerators, dishwashers, and ovens are often integrated ...

, Jackson's informal circle of advisors.

Ambassador to Britain and vice-presidency

In August 1831, Jackson gave Van Buren a

In August 1831, Jackson gave Van Buren a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

as the ambassador to Britain, and Van Buren arrived in London in September. He was cordially received, but in February 1832, he learned that the Senate had rejected his nomination. The rejection of Van Buren was essentially the work of Calhoun. When the vote on Van Buren's nomination was taken, enough pro-Calhoun Jacksonians refrained from voting to produce a tie, which allowed Calhoun to cast the deciding vote against Van Buren.

Calhoun was elated, convinced that he had ended Van Buren's career. "It will kill him dead, sir, kill him dead. He will never kick, sir, never kick", Calhoun exclaimed to a friend. Calhoun's move backfired; by making Van Buren appear the victim of petty politics, Calhoun raised Van Buren in both Jackson's regard and the esteem of others in the Democratic Party. Far from ending Van Buren's career, Calhoun's action gave greater impetus to Van Buren's candidacy for vice president.

Seeking to ensure that Van Buren would replace Calhoun as his running mate, Jackson had arranged for a national convention of his supporters. The May 1832 Democratic National Convention subsequently nominated Van Buren to serve as the party's vice presidential nominee. Van Buren won the nomination over Philip P. Barbour (Calhoun's favored candidate) and Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780 – November 19, 1850) was an American lawyer, military officer and politician who served as the ninth vice president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841 under President Martin Van Buren ...

due to the support of Jackson and the strength of the Albany Regency. Upon Van Buren's return from Europe in July 1832, he became involved in the Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its re ...

, a struggle over the renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

.

Van Buren had long been distrustful of banks, and he viewed the Bank as an extension of the Hamiltonian economic program, so he supported Jackson's veto of the Bank's re-charter. Henry Clay, the presidential nominee of the National Republicans, made the struggle over the Bank the key issue of the presidential election of 1832. The Jackson–Van Buren ticket won the 1832 election by a landslide, and Van Buren took office as vice president in March 1833. During the Nullification Crisis, Van Buren counseled Jackson to pursue a policy of conciliation with South Carolina leaders. He played little direct role in the passage of the Tariff of 1833

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was ...

, but he quietly hoped that the tariff would help bring an end to the Nullification Crisis, which it did.

As Vice President, Van Buren continued to be one of Jackson's primary advisors and confidants, and accompanied Jackson on his tour of the northeastern United States in 1833. Jackson's struggle with the Second Bank of the United States continued, as the president sought to remove federal funds from the Bank. Though initially apprehensive of the removal due to congressional support for the Bank, Van Buren eventually came to support Jackson's policy. He also helped undermine a fledgling alliance between Jackson and Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

, a senator from Massachusetts who could have potentially threatened Van Buren's project to create two parties separated by policy differences rather than personalities. During Jackson's second term, the president's supporters began to refer to themselves as members of the Democratic Party. Meanwhile, those opposed to Jackson, including Clay's National Republicans, followers of Calhoun and Webster, and many members of the Anti-Masonic Party, coalesced into the Whig Party.

Presidential election of 1836

PresidentAndrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

declined to seek another term in the 1836 presidential election, but he remained influential within the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

as his second term came to an end. Jackson was determined to help elect Van Buren in 1836 so that the latter could continue the Jackson administration's policies. The two men—the charismatic "Old Hickory" and the efficient "Sly Fox"—had entirely different personalities but had become an effective team in eight years in office together. With Jackson's support, Van Buren won the presidential nomination of the 1835 Democratic National Convention

The 1835 Democratic National Convention was held from May 20 to May 22, 1835, in Baltimore, Maryland. It was the second presidential nominating convention held in the history of the Democratic Party, following the 1832 Democratic National Conven ...

without opposition. Two names were put forward for the vice-presidential nomination: Representative Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky, and former Senator William Cabell Rives

William Cabell Rives (May 4, 1793April 25, 1868) was an American lawyer, planter, politician and diplomat from Virginia. Initially a Jackson Democrat as well as member of the First Families of Virginia, Rives served in the Virginia House of Deleg ...

of Virginia. Southern Democrats, and Van Buren himself, strongly preferred Rives. Jackson, on the other hand, strongly preferred Johnson. Again, Jackson's considerable influence prevailed, and Johnson received the required two-thirds vote after New York Senator Silas Wright

Silas Wright Jr. (May 24, 1795 – August 27, 1847) was an American attorney and Democratic politician. A member of the Albany Regency, he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York State Comptroller, United Stat ...

prevailed upon non-delegate Edward Rucker to cast the 15 votes of the absent Tennessee delegation in Johnson's favor.

Hugh Lawson White

Hugh Lawson White (October 30, 1773April 10, 1840) was a prominent American politician during the first third of the 19th century. After filling in several posts particularly in Tennessee's judiciary and state legislature since 1801, thereunder ...

of Tennessee, Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, and William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

of Indiana. Besides endorsing internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

and a national bank, the Whigs tried to tie Democrats to abolitionism and sectional tension, and attacked Jackson for "acts of aggression and usurpation of power".

Southern voters represented the biggest potential impediment to Van Buren's quest for the presidency, as many were apprehensive at the prospect of a Northern president. Van Buren moved to obtain their support by assuring them that he opposed abolitionism and supported maintaining slavery in states where it already existed. To demonstrate consistency regarding his opinions on slavery, Van Buren cast the tie-breaking Senate vote for a bill to subject abolitionist mail to state laws, thus ensuring that its circulation would be prohibited in the South. Van Buren considered slavery to be immoral but sanctioned by the Constitution.

Van Buren won the election with 764,198 popular votes, 50.9% of the total, and 170 electoral votes. Harrison led the Whigs with 73 electoral votes, White receiving 26, and Webster 14. Willie Person Mangum

Willie Person Mangum (; May 10, 1792September 7, 1861) was a U.S. Senator from the state of North Carolina between 1831 and 1836 and between 1840 and 1853. He was one of the founders and leading members of the Whig party, and was a candidate for ...

received South Carolina's 11 electoral votes, which were awarded by the state legislature. Van Buren's victory resulted from a combination of his attractive political and personal qualities, Jackson's popularity and endorsement, the organizational power of the Democratic Party, and the inability of the Whig Party to muster an effective candidate and campaign. Virginia's presidential electors voted for Van Buren for president, but voted for William Smith for vice president, leaving Johnson one electoral vote short of election. In accordance with the Twelfth Amendment, the Senate elected Johnson vice president in a contingent vote.

The election of 1836 marked an important turning point in American political history because it saw the establishment of the Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

. In the early 1830s, the political party structure was still changing, rapidly, and factional and personal leaders continued to play a major role in politics. By the end of the campaign of 1836, the new party system was almost complete, as nearly every faction had been absorbed by either the Democrats or the Whigs.

Presidency (1837–1841)

Cabinet

Van Buren retained much of Jackson's cabinet and lower-level appointees, as he hoped that the retention of Jackson's appointees would stop Whig momentum in the South and restore confidence in the Democrats as a party of sectional unity. The cabinet holdovers represented the different regions of the country: Secretary of the TreasuryLevi Woodbury

Levi Woodbury (December 22, 1789September 4, 1851) was an American attorney, jurist, and Democratic politician from New Hampshire. During a four-decade career in public office, Woodbury served as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U ...

came from New England, Attorney General Benjamin F. Butler and Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson

Mahlon Dickerson (April 17, 1770 – October 5, 1853) was a justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey, the seventh governor of New Jersey, United States Senator from New Jersey, the 10th United States Secretary of the Navy and a United States ...

hailed from mid-Atlantic states, Secretary of State John Forsyth represented the South, and Postmaster General Amos Kendall

Amos Kendall (August 16, 1789 – November 12, 1869) was an American lawyer, journalist and politician. He rose to prominence as editor-in-chief of the '' Argus of Western America'', an influential newspaper in Frankfort, the capital of the U.S. ...

of Kentucky represented the West.

For the lone open position of Secretary of War, Van Buren first approached William Cabell Rives, who had sought the vice presidency in 1836. After Rives declined to join the cabinet, Van Buren appointed Joel Roberts Poinsett

Joel Roberts Poinsett (March 2, 1779December 12, 1851) was an American physician, diplomat and botanist. He was the first U.S. agent in South America, a member of the South Carolina legislature and the United States House of Representatives, the ...

, a South Carolinian who had opposed secession during the Nullification Crisis. Van Buren's cabinet choices were criticized by Pennsylvanians such as James Buchanan, who argued that their state deserved a cabinet position as well as some Democrats who argued that Van Buren should have used his patronage powers to augment his power. However, Van Buren saw value in avoiding contentious patronage battles, and his decision to retain Jackson's cabinet made it clear that he intended to continue the policies of his predecessor. Additionally, Van Buren had helped select Jackson's cabinet appointees and enjoyed strong working relationships with them.

Van Buren held regular formal cabinet meetings and discontinued the informal gatherings of advisors that had attracted so much attention during Jackson's presidency. He solicited advice from department heads, tolerated open and even frank exchanges between cabinet members, perceiving himself as "a mediator, and to some extent an umpire between the conflicting opinions" of his counselors. Such detachment allowed the president to reserve judgment and protect his prerogative for making final decisions. These open discussions gave cabinet members a sense of participation and made them feel part of a functioning entity, rather than isolated executive agents. Van Buren was closely involved in foreign affairs and matters pertaining to the Treasury Department; but the Post Office, War Department, and Navy Department had significant autonomy under their respective cabinet secretaries.

Panic of 1837

When Van Buren entered office, the nation's economic health had taken a turn for the worse and the prosperity of the early 1830s was over. Two months into his presidency, on May 10, 1837, some important state banks in New York, running out of hard currency reserves, refused to convert paper money into gold or silver, and other financial institutions throughout the nation quickly followed suit. This

When Van Buren entered office, the nation's economic health had taken a turn for the worse and the prosperity of the early 1830s was over. Two months into his presidency, on May 10, 1837, some important state banks in New York, running out of hard currency reserves, refused to convert paper money into gold or silver, and other financial institutions throughout the nation quickly followed suit. This financial crisis

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and man ...

would become known as the Panic of 1837. The Panic was followed by a five-year depression in which banks failed and unemployment reached record highs.

Van Buren blamed the economic collapse on greedy American and foreign business and financial institutions, as well as the over-extension of credit by U.S. banks. Whig leaders in Congress blamed the Democrats, along with Andrew Jackson's economic policies, specifically his 1836 Specie Circular

The Specie Circular is a United States presidential executive order issued by President Andrew Jackson in 1836 pursuant to the Coinage Act. It required payment for government land to be in gold and silver.

History

The Specie Circular was a rea ...

. Cries of "rescind the circular!" went up and former president Jackson sent word to Van Buren asking him not to rescind the order, believing that it had to be given enough time to work. Others, like Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

, believed that Jackson's dismantling of the Bank of the United States was directly responsible for the irresponsible creation of paper money by the state banks which had precipitated this panic. The Panic of 1837 loomed large over the 1838 election cycle, as the carryover effects of the economic downturn led to Whig gains in both the U.S. House and Senate. The state elections in 1837 and 1838 were also disastrous for the Democrats, and the partial economic recovery in 1838 was offset by a second commercial crisis later that year.

To address the crisis, the Whigs proposed rechartering the national bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

. The president countered by proposing the establishment of an independent U.S. treasury, which he contended would take the politics out of the nation's money supply. Under the plan, the government would hold its money in gold or silver, and would be restricted from printing paper money

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

at will; both measures were designed to prevent inflation. The plan would permanently separate the government from private banks by storing government funds in government vaults rather than in private banks. Van Buren announced his proposal in September 1837, but an alliance of conservative Democrats and Whigs prevented it from becoming law until 1840. As the debate continued, conservative Democrats like Rives defected to the Whig Party, which itself grew more unified in its opposition to Van Buren. The Whigs would abolish the Independent Treasury system in 1841, but it was revived in 1846, and remained in place until the passage of the Federal Reserve Act

The Federal Reserve Act was passed by the 63rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913. The law created the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States.

The Pani ...

in 1913. More important for Van Buren's immediate future, the depression would be a major issue in his upcoming re-election campaign.

Indian removal

Federal policy under Jackson had sought to move Indian tribes to lands west of theMississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

through the Indian Removal Act of 1830

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

, and the federal government negotiated 19 treaties with Indian tribes during Van Buren's presidency. The 1835 Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established ter ...

signed by government officials and representatives of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

tribe had established terms under which the Cherokees ceded their territory in the southeast and agreed to move west to Oklahoma. In 1838, Van Buren directed General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

to forcibly move all those who had not yet complied with the treaty.

The Cherokees were herded violently into internment camp