Varlam Shalamov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

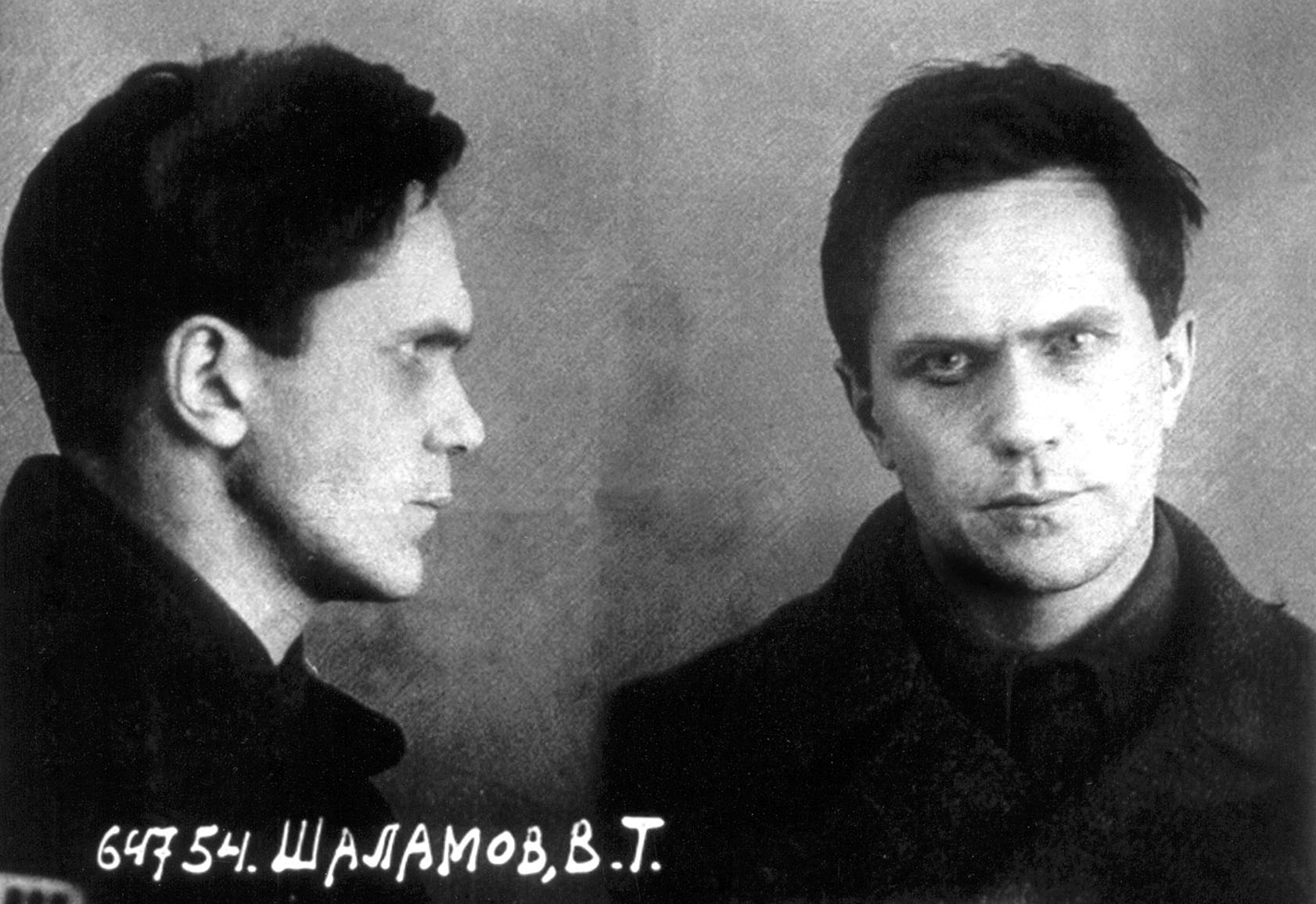

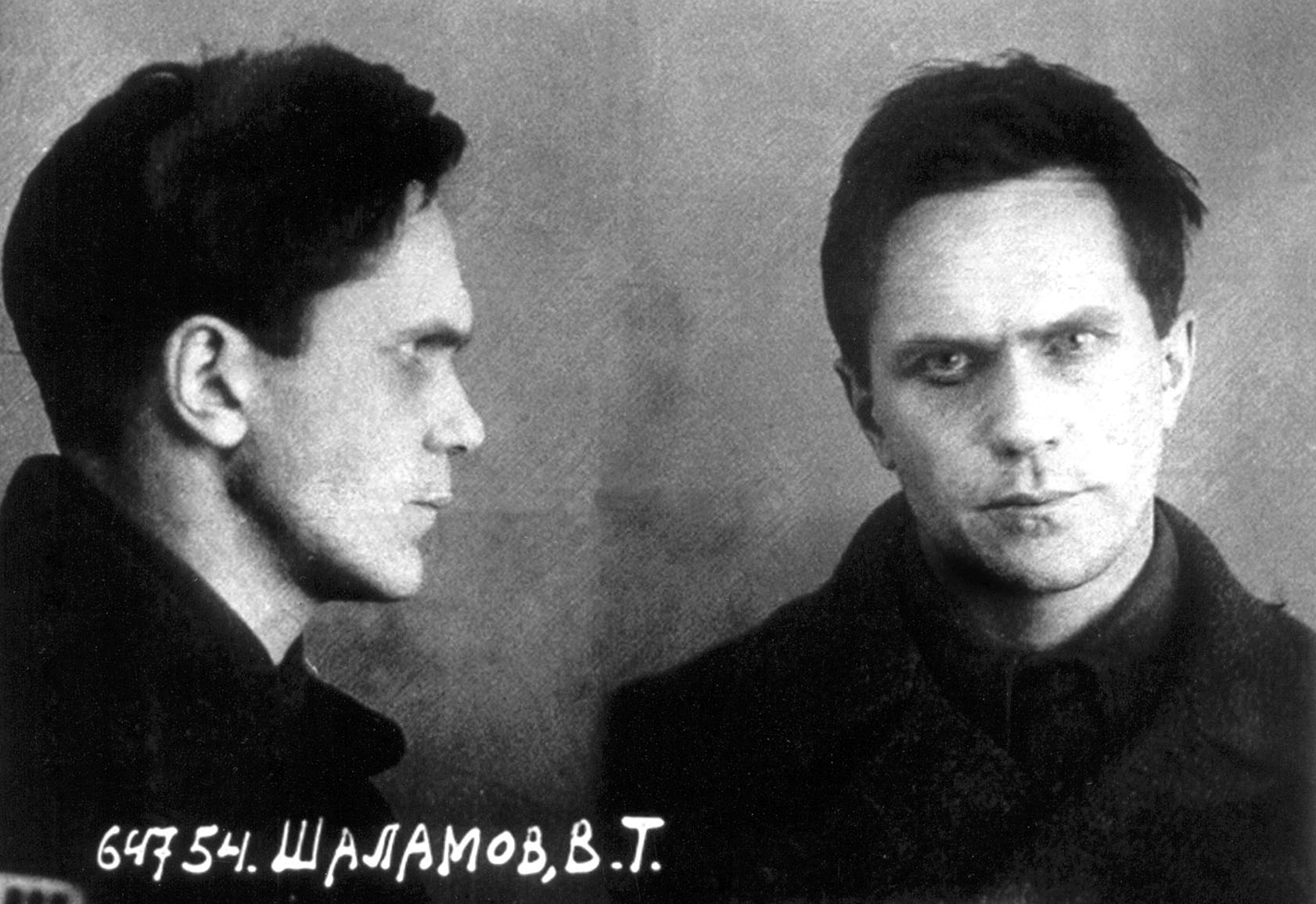

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov (; 18 June 1907 – 17 January 1982), baptized as Varlaam, was a Russian writer, journalist, poet and

Varlam Shalamov was born in

Varlam Shalamov was born in

Shalamov joined a

Shalamov joined a

At the outset of the

At the outset of the

Database of the Memorial Society.

Завещание Ленина

, based on ''Kolyma Tales''. ALetter

songs by Elena Frolova and there are audio records of Shalamov reading his own poetry

Varlam Shalamov official site

Russian series "Lenin's Testament", based on Kolyma Tales (online)

* Fil

My Several Lives (1991)

Varlam Shalamov official site

Varlam Shalamov on Lib.ru

Varlam Shalamov. Poetry

Grave site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shalamov, Varlam 1907 births 1982 deaths People from Vologda People from Vologodsky Uyezd Soviet short story writers 20th-century Russian short story writers Russian male short story writers Stalinism-era scholars and writers 20th-century Russian poets Russian male poets Soviet Trotskyists Russian socialists Russian Trotskyists Moscow State University alumni Gulag detainees Soviet rehabilitations Burials at Kuntsevo Cemetery

Gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

survivor. He spent much of the period from 1937 to 1951 imprisoned in forced-labor camps in the Arctic region of Kolyma

Kolyma (, ) or Kolyma Krai () is a historical region in the Russian Far East that includes the basin of Kolyma River and the northern shores of the Sea of Okhotsk, as well as the Kolyma Mountains (the watershed of the two). It is bounded to ...

, due in part to his support of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

and praise of writer Ivan Bunin

Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin ( or ; rus, Ива́н Алексе́евич Бу́нин, p=ɪˈvan ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪdʑ ˈbunʲɪn, a=Ivan Alyeksyeyevich Bunin.ru.vorb.oga; – 8 November 1953)Kolyma Tales

''Kolyma Tales'' or ''Kolyma Stories'' (, ''Kolymskiye rasskazy'') is the name given to six collections of short stories by Russian author Varlam Shalamov, about labour camp life in the Soviet Union. Most stories are documentaries and reflect the ...

''. These books were initially published in the West, in English translation, starting in the 1960s; they were eventually published in the original Russian, but only became officially available in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in 1987, in the post-glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

era. ''The Kolyma Tales'' are considered Shalamov's masterpiece, and "the definitive chronicle" of life in the labor camps.

Early life

Varlam Shalamov was born in

Varlam Shalamov was born in Vologda

Vologda (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Vologda Oblast, Russia, located on the river Vologda (river), Vologda within the watershed of the Northern Dvina. Population:

The city serves as ...

, Vologda Governorate

Vologda Governorate (), also known as the Government of Vologda, was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Russian Empire and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR, which existed from 1796 until 1929. ...

, a Russian city with a rich culture famous for its wooden architecture, to the family of a hereditary Russian Orthodox

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

priest and teacher, Father Tikhon Nikolayevich Shalamov, a graduate of the . At first young Shalamov was named and baptized after the patron of Vologda, Saint Varlaam of Khutyn (1157–1210); Shalamov later changed his name to the more common Varlam. Shalamov's mother, Nadezhda (Nadia) Aleksandrovna, was a teacher as well. She also enjoyed poetry, and Varlam speculated that she could have become a poet if not for her family. His father worked as a missionary in Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

for 12 years from 1892, and Varlam's older brother, Sergei, grew up there (he volunteered for World War I and was killed in action in 1917); they returned as events were heating up in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

by 1905. In 1914, Varlam entered the gymnasium of St. Alexander's and graduated in 1923. Although he was a son of a priest, he used to say that he lost faith and became an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

at the age of 13. His father was of very progressive views and even supported the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

in a way.

Upon his graduation it became clear that the Regional Department of People's Education (RONO, ''Regionalnoe Otdelenie Narodnogo Obrazovania'') would not support his further education because Varlam was a son of a priest. Therefore, he found a job as a tanner at the leather factory in the settlement of Kuntsevo (a suburb of Moscow, since 1960 part of the Moscow city). In 1926, after having worked for two years, he was accepted into the department of Soviet Law at Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

through open competition. While studying there Varlam was intrigued by the oratory skills displayed during the debates between Anatoly Lunacharsky

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (, born ''Anatoly Aleksandrovich Antonov''; – 26 December 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and the first Soviet People's Commissariat for Education, People's Commissar (minister) of Education, as well ...

and Metropolitan Alexander Vvedensky. At that time Shalamov was convinced that he would become a literature specialist. His literary tastes included Modernist literature

Modernist literature originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterised by a self-conscious separation from traditional ways of writing in both poetry and prose fiction writing. Modernism experimented with literary form a ...

(later, he would say that he considered his teachers not Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

, of whom he was very critical, or other classic writers, but Andrei Bely

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev (, ; – 8 January 1934), better known by the pen name Andrei Bely or Biely, was a Russian novelist, Symbolist poet, theorist and literary critic. He was a committed anthroposophist and follower of Rudolf Steiner. Hi ...

and Aleksey Remizov

Aleksey Mikhailovich Remizov (; in Moscow – 26 November 1957 in Paris) was a Russian modernist writer whose creative imagination veered to the fantastic and bizarre. Apart from literary works, Remizov was an expert calligrapher who sought to ...

) and classic poetry. His favorite poets were Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

and Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

, whose works influenced him his entire life. He also praised Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influenti ...

, Savinkov, Joyce and Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized f ...

, about whom he later wrote a long essay depicting the myriad possibilities of artistic endeavors.

First imprisonment, 1929–1932

Shalamov joined a

Shalamov joined a Trotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

-leaning group and on February 19, 1929, was arrested and sent to Butyrskaya prison for solitary confinement

Solitary confinement (also shortened to solitary) is a form of imprisonment in which an incarcerated person lives in a single Prison cell, cell with little or no contact with other people. It is a punitive tool used within the prison system to ...

. He was later sentenced to three years of correctional labor in the town of Vizhaikha, convicted of distributing the "Letters to the Party Congress" known as Lenin's Testament

Lenin's Testament is a document alleged to have been dictated by Vladimir Lenin in late 1922 and early 1923, during and after his suffering of multiple strokes. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bod ...

, which were critical of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, and of participating in a demonstration marking the tenth anniversary of the Soviet revolution with the slogan "Down with Stalin". Courageously he refused to sign the sentence branding him a criminal. Later, he would write in his short stories that he was proud of having continued the Russian revolutionary tradition of members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia. The party memb ...

and Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya () was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system. The org ...

, who were fighting against tsarism

Tsarist autocracy (), also called Tsarism, was an autocracy, a form of absolute monarchy in the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire. In it, the Tsar possessed in principle authority and ...

. He was taken by train to the former Solikamsk

Solikamsk (, , also Соликамскӧй, ''Sovkamsköy'') is a town in Perm Krai, Russia. Modern Solikamsk is the third-largest town in the krai, with a population of

History

The earliest surviving recorded mention of Solikamsk, initially a ...

monastery, which was transformed into a militsiya

''Militsiya'' ( rus, милиция, 3=mʲɪˈlʲitsɨjə, 5=, ) were the police forces in the Soviet Union until 1991, in several Eastern Bloc countries (1945–1992), and in the Non-Aligned Movement, non-aligned Socialist Federal Republic ...

headquarters of the Vishera department of Solovki ITL}

Shalamov was released in 1931 and worked in the new town of Berezniki, Perm Oblast

Until 1 December 2005, Perm Oblast () was a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) in Privolzhsky (Volga) Federal District. According to the results of the referendum held in October 2004, Perm Oblast was merged with Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug ...

, at the local chemical plant construction site. He was given the opportunity to travel to Kolyma

Kolyma (, ) or Kolyma Krai () is a historical region in the Russian Far East that includes the basin of Kolyma River and the northern shores of the Sea of Okhotsk, as well as the Kolyma Mountains (the watershed of the two). It is bounded to ...

for colonization. Sarcastically, Shalamov said that he would go there only under enforced escort. Coincidentally, fate would hold him to his promise several years later. He returned to Moscow in 1932, where he worked as a journalist and managed to see some of his essays and articles published, including his first short story, "The three deaths of Doctor Austino" (1936).

Second imprisonment, 1937–1942

At the outset of the

At the outset of the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, on January 12, 1937, Shalamov was arrested again for "counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities" and sent to Kolyma

Kolyma (, ) or Kolyma Krai () is a historical region in the Russian Far East that includes the basin of Kolyma River and the northern shores of the Sea of Okhotsk, as well as the Kolyma Mountains (the watershed of the two). It is bounded to ...

, also known as "the land of white death", for five years. He was already in jail awaiting sentencing when one of his short stories was published in the literary journal ''Literary Contemporary''.

Third imprisonment, 1943–1951

In 1943, Shalamov was sentenced to another term, this time for 10 years, under Article 58 (anti-Soviet agitation), in part, for having called NobelistIvan Bunin

Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin ( or ; rus, Ива́н Алексе́евич Бу́нин, p=ɪˈvan ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪdʑ ˈbunʲɪn, a=Ivan Alyeksyeyevich Bunin.ru.vorb.oga; – 8 November 1953)typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

, of which Shalamov was not aware until he became well. At that time, as he recollects in his writings, he did not care much about his survival.

In 1946, while becoming a ''dokhodyaga'' (one in an emaciated

Emaciation is defined as the state of extreme thinness from absence of body fat and muscle wasting usually resulting from malnutrition. It is often seen as the opposite of obesity.

Characteristics

Emaciation manifests physically as thin limbs, pr ...

and devitalized state, which in Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

literally means one who is walking towards the ultimate end), his life was saved by a doctor-inmate, A. I. Pantyukhov, who risked his own life to get Shalamov a place as a camp hospital attendant. The new career allowed Shalamov to survive and concentrate on writing poetry.

After release

In 1951, Shalamov was released from the camp, and continued working as a medical assistant for the forced labor camps of Sevvostlag while still writing. After his release, he was faced with the dissolution of his former family, including a grown-up daughter who now refused to recognize her father. In 1952, Shalamov sent his poetry toBoris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

, who praised his work. Shalamov was allowed to leave Magadan

Magadan ( rus, Магадан, p=məɡɐˈdan) is a Port of Magadan, port types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative centre of Magadan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the isthmus of the Staritsky Peninsula by the ...

in November 1953 following Stalin's death in March of that year, and was permitted to go to the village of Turkmen in Kalinin Oblast

Tver Oblast (, ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is the city of Tver. From 1935 to 1990, it was known as Kalinin Oblast (). Population:

Tver Oblast is a region of lakes, such as Seliger and Brosno. Much of ...

, near Moscow, where he worked as a supply agent.

''Kolyma Tales''

From 1954 to 1973, Shalamov worked on his book of short stories of labour camp life, ''Kolyma Tales

''Kolyma Tales'' or ''Kolyma Stories'' (, ''Kolymskiye rasskazy'') is the name given to six collections of short stories by Russian author Varlam Shalamov, about labour camp life in the Soviet Union. Most stories are documentaries and reflect the ...

''. During the Khrushchev thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw (, or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when Political repression in the Soviet Union, repression and Censorship in ...

, many inmates

A prisoner, also known as an inmate or detainee, is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement or captivity in a prison or physical restraint. The term usually applies to one serving a Sentence (law), se ...

were released from the Gulag and politically rehabilitated. Some were rehabilitated posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award, an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication, publishing of creative work after the author's death

* Posthumous (album), ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1 ...

. Shalamov was allowed to return to Moscow after having been officially exonerated ("rehabilitated") in 1956. In 1957, he became a correspondent for the literary journal ''Moskva'', and his poetry began to be published. His health, however, had been broken by his years in the camps, and he received a disability pension.

Shalamov proceeded to publish poetry and essays in the major Soviet literary magazines while writing his magnum opus

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

, ''Kolyma Tales''. He was acquainted with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Soviet and Russian author and Soviet dissidents, dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag pris ...

, Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

, and Nadezhda Mandelstam. The manuscripts of ''Kolyma Tales'' were smuggled abroad and distributed via ''samizdat

Samizdat (, , ) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual rep ...

''. The translations were published in the West in 1966. The complete Russian-language edition was published in London in 1978, and reprinted thereafter both in Russian and in translation. As the Soviet scholar David Satter writes, "Shalamov's short stories are the definitive chronicle of those camps". ''Kolyma Tales'' is considered to be one of the great Russian collections of short stories of the twentieth century.

Late in life, Shalamov got on bad terms with Solzhenitsyn and other fellow dissidents, and opposed the publication of his own works abroad.

Shalamov also wrote a series of autobiographical essays that vividly bring to life the city ofGospodin ''Gospodar'' or ''hospodar'', also ''gospodin'' as a diminutive, is a term of Slavic languages, Slavic origin, meaning "lord" or "Master (form of address), master". The compound (, , , sh-Latn-Cyrl, gospodar, господар, ) is a derivative o ...Solzhenitsyn, I willingly accept Your funeral joke on the account of my death. With the feeling of honor and pride I consider myself the firstCold War The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...victim which have fallen from Your hand … – From the undispatched letter of V. T. Shalamov to A. I. Solzhenitsyn

Vologda

Vologda (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Vologda Oblast, Russia, located on the river Vologda (river), Vologda within the watershed of the Northern Dvina. Population:

The city serves as ...

and his life before prison.

Last years

As his health deteriorated, he spent the last three years of his life in a house for elderly and disabled writers operated by Litfond (Union of Soviet Writers

The Union of Soviet Writers, USSR Union of Writers, or Soviet Union of Writers () was a creative union of professional writers in the Soviet Union. It was founded in 1934 on the initiative of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (1932) a ...

) in Tushino. The quality of this nursing home can be judged from the memoirs of Yelena Zakharova, who was introduced to Shalamov by her father, who had translated some of his works, and was close to Shalamov in the last six months of his life:

Despite his impairments, he continued to compose poems, which were written down and published by . Following a cursory examination, it was determined that he should be transferred to a psychiatric facility. On the way there, he became ill and contracted pneumonia. Shalamov died on January 17, 1982, and, despite having been an atheist, was given an Orthodox funeral ceremony (at the insistence of his friend, Zakharova) and was interred at Kuntsevo Cemetery, Moscow. The historian Valery Yesipov wrote that only forty people attended Shalamov's funeral, not counting plainclothes policemen.

''Kolyma Tales'' was finally published on Russian soil in 1987, as a result of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

's glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

policy.

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov was rehabilitated in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

on July 18, 1956 by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union.Victims of political terror in the USSR.Database of the Memorial Society.

Legacy

In 1991, the Shalamov family house in Vologda, next to the town's cathedral, was turned into the Shalamov Memorial Museum and local art gallery. The cathedral hill in Vologda has been named in his memory. One of the Kolyma short stories, "The Final Battle of Major Pugachoff", was made into a film () in 2005. In 2007, Russian Television produced the series "Lenin's TestamentЗавещание Ленина

, based on ''Kolyma Tales''. A

minor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

3408 Shalamov discovered by Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh

Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh ( rus, Никола́й Степа́нович Черны́х, , nʲɪkɐˈlaj sʲtʲɪˈpanəvʲɪtɕ tɕɪrˈnɨx, links=yes; 6 October 1931 – 25 May 2004Казакова, Р.К. Памяти Николая Сте ...

in 1977 is named after him. A memorial to Shalamov was erected in Krasnovishersk in June 2007, the site of his first labor camp.

Shalamov's friend, Fedot Fedotovich Suchkov, erected a monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, historical ...

on the burial plot, which was destroyed by unknown vandals in 2001. The criminal case was closed as uncompleted. With the help of some workers from ''SeverStal

Severstal () is a Russian company mainly operating in the steel and mining industry, headquartered in Cherepovets. Severstal is listed on the Moscow Exchange and LSE and is the largest steel company in Russia. The company is majority-owned and ...

'' the monument was reestablished in 2001.

A few of Shalamov's poems were set to music and performed as songs.songs by Elena Frolova and there are audio records of Shalamov reading his own poetry

Bibliography

*''Ocherki Prestupnovo Mira: Ob Odnoi Oshibke Khudojestvennoi Literatura''. 1959.See also

*History of the Soviet Union

The history of the Soviet Union (USSR) (1922–91) began with the ideals of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution and ended in dissolution amidst economic collapse and political disintegration. Established in 1922 following the Russian Civil War, ...

*Enemy of the people

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and the social class, social-class opponents of the Power (social and political), power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, ...

* 101st km

*Karlo Štajner

Karlo Štajner (15 January 1902 – 1 April 1992) was an Austrian-Yugoslav communist activist and a prominent Gulag survivor. Štajner was born in Vienna, where he joined the Communist Youth of Austria, but emigrated to the Kingdom of Serbs, ...

*Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Soviet and Russian author and dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system. He was a ...

* Lev Razgon

* Evgenia Ginzburg

References

Publications

* ''Kolyma Tales'' * ''Graphite'' * ''Vospominaniia'' (memoirs) *Varlam Shalamov (1998) "Complete Works" (Варлам Шаламов. Собрание сочинений в четырех томах), printed by publishers '' Vagrius'' and '' Khudozhestvennaya Literatura'', ,External links

Varlam Shalamov official site

Russian series "Lenin's Testament", based on Kolyma Tales (online)

* Fil

My Several Lives (1991)

Varlam Shalamov official site

Varlam Shalamov on Lib.ru

Varlam Shalamov. Poetry

Grave site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shalamov, Varlam 1907 births 1982 deaths People from Vologda People from Vologodsky Uyezd Soviet short story writers 20th-century Russian short story writers Russian male short story writers Stalinism-era scholars and writers 20th-century Russian poets Russian male poets Soviet Trotskyists Russian socialists Russian Trotskyists Moscow State University alumni Gulag detainees Soviet rehabilitations Burials at Kuntsevo Cemetery