United States v. The Amistad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''United States v. Schooner Amistad'', 40 U.S. (15 Pet.) 518 (1841), was a

On June 27, 1839, '' La Amistad'' ("Friendship"), a Spanish vessel, departed from the port of

On June 27, 1839, '' La Amistad'' ("Friendship"), a Spanish vessel, departed from the port of

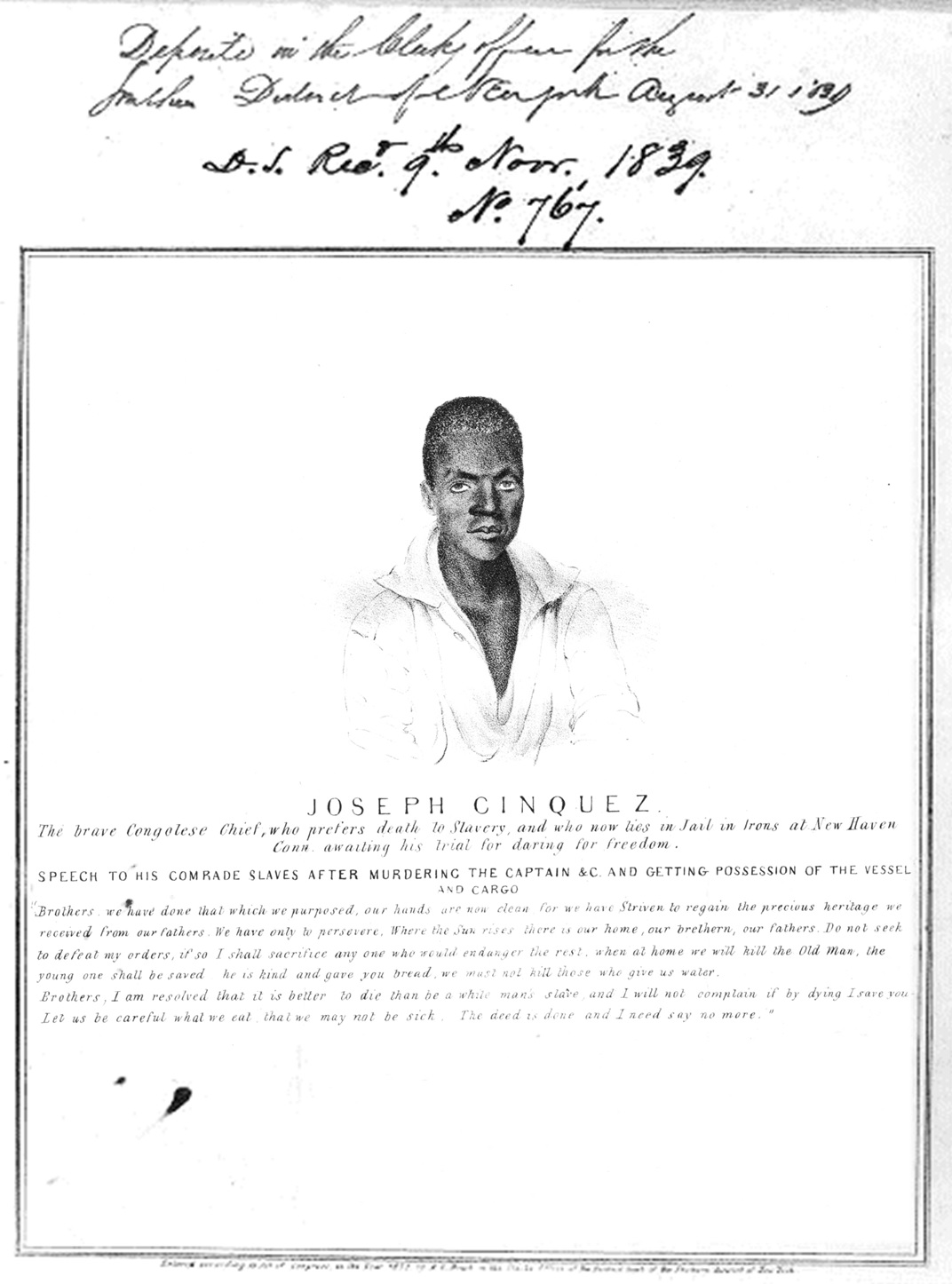

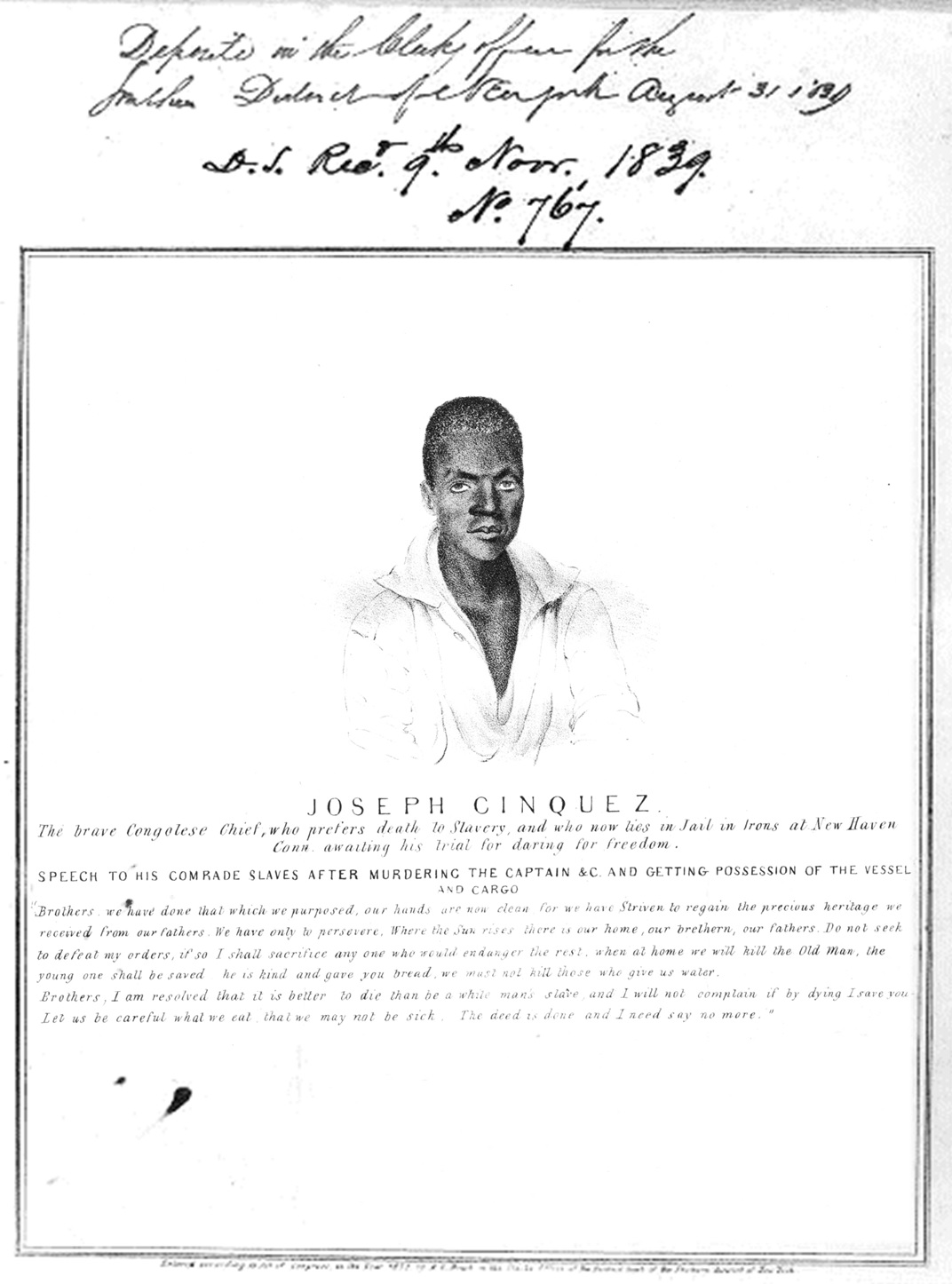

pp. 587–588 As the voyage normally took only four days, the crew had brought four days' worth of rations and had not anticipated the strong headwind that slowed the schooner. On July 2, 1839, one of the Africans, Joseph Cinqué, freed himself and the other captives using a file that had been found and kept by a woman who, like them, had been on the '' Tecora'', the Portuguese ship that had transported them illegally as slaves from West Africa to Cuba. The Mende killed the ship's cook, Celestino, who had told them that they were to be killed and eaten by their captors. The Mende also killed Captain Ferrer, and the armed struggle resulted as well in the deaths of two Africans. Two sailors escaped in a lifeboat. The Mende spared the lives of the two Spaniards who could navigate the ship, José Ruiz and Pedro Montez, if they returned the ship east across the

A case before the

A case before the  The abolitionist movement had formed the "''Amistad'' Committee," headed by the New York City merchant Lewis Tappan, and had collected money to mount a defense of the Africans. Initially, communication with the Africans was difficult since they spoke neither English nor Spanish. Professor J.W. Gibbs learned from the Africans to count to ten in their

The abolitionist movement had formed the "''Amistad'' Committee," headed by the New York City merchant Lewis Tappan, and had collected money to mount a defense of the Africans. Initially, communication with the Africans was difficult since they spoke neither English nor Spanish. Professor J.W. Gibbs learned from the Africans to count to ten in their

Amistad Research Center – Essays, Tulane University

The Africans greeted the news of the Supreme Court's decision with joy. Abolitionist supporters took the survivors – 36 men and boys and three girls – to Farmington, a village considered "Grand Central Station" on the

The Africans greeted the news of the Supreme Court's decision with joy. Abolitionist supporters took the survivors – 36 men and boys and three girls – to Farmington, a village considered "Grand Central Station" on the

The revolt aboard ''La Amistad,'' the background of the slave trade and its subsequent trial is retold in a celebrated poem by Robert Hayden entitled "

The revolt aboard ''La Amistad,'' the background of the slave trade and its subsequent trial is retold in a celebrated poem by Robert Hayden entitled "

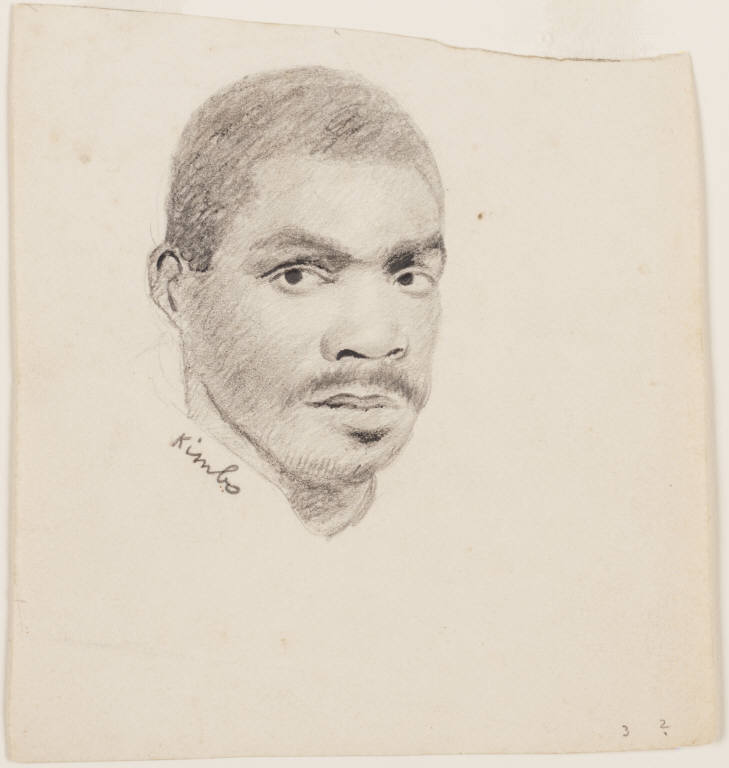

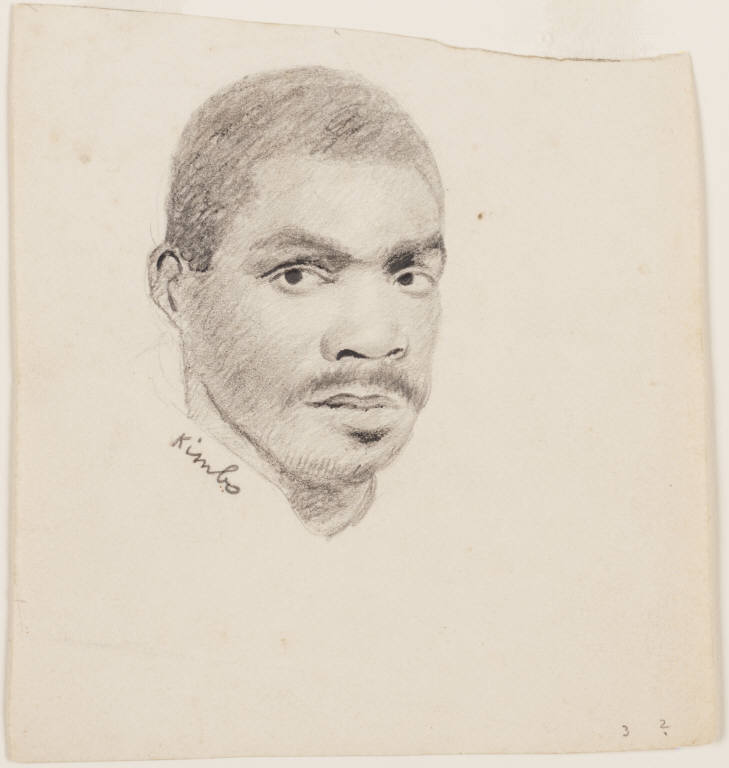

"Courtroom portraits of the ''Amistad'' captives drawn by New Haven resident William H. Townsend while the prisoners awaited trial"

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

Amistad Ctr

1841, e-text, University of North Carolina

Gilder Lehrman Center, Yale Univ

Cornell University (include

"''Amistad'' Court Records Online"

Footnote

"The ''Amistad'' Case"

the University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School {{Taney Court Conflicts in 1841 1841 in United States case law Pre-emancipation African-American history Freedom suits in the United States Legal history of Connecticut Farmington, Connecticut Mutinies United States maritime case law International maritime incidents Legal history of Spain La Amistad 1841 in Connecticut Maritime incidents in the United States United States Supreme Court cases of the Taney Court African-American history of Connecticut Spain–United States relations Fugitive American slaves United States Supreme Court cases

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

case resulting from the rebellion of Africans on board the Spanish schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

'' La Amistad'' in 1839.. It was an unusual freedom suit

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by enslaved people against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free sta ...

that involved international diplomacy as well as United States law. The historian Samuel Eliot Morison

Samuel Eliot Morison (July 9, 1887 – May 15, 1976) was an American historian noted for his works of maritime history and American history that were both authoritative and popular. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912, and tau ...

described it in 1969 as the most important court case involving slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

before being eclipsed by that of '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' in 1857.

''La Amistad'' was traveling along the coast of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

on her way to a port for re-sale of the slaves. The Africans, Mende people

The Mende are one of the two largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone; their neighbours, the Temne people, constitute the largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone, ethnic group at 35.5% of the total population, which is slightly larger than the Mende ...

who had been kidnapped in the area of Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

, in West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

, illegally sold into slavery and shipped to Cuba, escaped their shackles and took over the ship. They killed the captain and the cook; two other crew members escaped in a lifeboat. The Mende directed the two Spanish navigator survivors to return them to Africa. The crew tricked them by sailing north at night. ''La Amistad'' was later apprehended near Long Island, New York

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

, by the United States Revenue-Marine (later renamed the United States Revenue Cutter Service

The United States Revenue Cutter Service was established by an Act of Congress () on 4 August 1790 as the Revenue-Marine at the recommendation of the nation's first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

The federal government bod ...

and one of the predecessors of the United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and Admiralty law, law enforcement military branch, service branch of the armed forces of the United States. It is one of the country's eight Uniformed services ...

) and taken into custody. The widely publicized court cases in the U.S. federal district court and eventually the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, in 1841, which addressed international issues, helped the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

movement.

In 1840, a federal district court found that the transport of the kidnapped Africans across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

on the Portuguese slave ship '' Tecora'' was in violation of U.S. laws against international slave trade. The captives were ruled to have acted as free men when they fought to escape their kidnapping and illegal confinement. The court ruled the Africans were entitled to take whatever legal measures necessary to secure their freedom, including the use of force. Under international and Southern sectional pressure, U.S. President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

ordered the case appealed to the Supreme Court. It affirmed the lower district court ruling on March 9, 1841, and authorized the release of the Mende, but it overturned the additional order of the lower court to return them to Africa at government expense. Supporters arranged for temporary housing of the Africans in Farmington, Connecticut

Farmington is a town in Hartford County, Connecticut, Hartford County in the Farmington Valley area of central Connecticut in the United States. The town is part of the Capitol Planning Region, Connecticut, Capitol Planning Region. The populati ...

, as well as funds for travel. In 1842, the 35 who wanted to return to Africa, together with U.S. Christian missionaries, were transported by ship to Sierra Leone.

Background

Rebellion at sea and capture

On June 27, 1839, '' La Amistad'' ("Friendship"), a Spanish vessel, departed from the port of

On June 27, 1839, '' La Amistad'' ("Friendship"), a Spanish vessel, departed from the port of Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, for the Province of Puerto Principe, also in Cuba. The masters of ''La Amistad'' were Captain Ramón Ferrer, José Ruiz, and Pedro Montes, all Spanish nationals. With Ferrer was Antonio, a man enslaved by Ferrer to serve him personally. Ruiz was transporting 49 Africans, who had been entrusted to him by the governor-general of Cuba. Montez held four additional Africans, also entrusted to him by the governor-general.''US v. The Amistad''pp. 587–588 As the voyage normally took only four days, the crew had brought four days' worth of rations and had not anticipated the strong headwind that slowed the schooner. On July 2, 1839, one of the Africans, Joseph Cinqué, freed himself and the other captives using a file that had been found and kept by a woman who, like them, had been on the '' Tecora'', the Portuguese ship that had transported them illegally as slaves from West Africa to Cuba. The Mende killed the ship's cook, Celestino, who had told them that they were to be killed and eaten by their captors. The Mende also killed Captain Ferrer, and the armed struggle resulted as well in the deaths of two Africans. Two sailors escaped in a lifeboat. The Mende spared the lives of the two Spaniards who could navigate the ship, José Ruiz and Pedro Montez, if they returned the ship east across the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

to Africa. They also spared Antonio, a creole, and used him as an interpreter with Ruiz and Montez.

Ruiz and Montez deceived the Africans and steered ''La Amistad'' north along the East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

, where the ship was sighted repeatedly. They dropped anchor a half-mile off eastern Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, on August 26, 1839, at Culloden Point. Some of the Africans went ashore to procure water and provisions from the hamlet of Montauk. The vessel was discovered by , a revenue cutter

A cutter is any of various types of watercraft. The term can refer to the rig (sail plan) of a sailing vessel (but with regional differences in definition), to a governmental enforcement agency vessel (such as a coast guard or border force cut ...

of the United States Revenue-Marine (later renamed the United States Revenue Cutter Service

The United States Revenue Cutter Service was established by an Act of Congress () on 4 August 1790 as the Revenue-Marine at the recommendation of the nation's first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

The federal government bod ...

and one of the predecessors of the United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and Admiralty law, law enforcement military branch, service branch of the armed forces of the United States. It is one of the country's eight Uniformed services ...

) while ''Washington'' was conducting hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore wind farms, offshore oil exploration and drilling and related activities. Surveys may als ...

work for the United States Coast Survey. Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

Thomas R. Gedney, commanding the cutter, saw some of the Africans on shore and, assisted by his officers and crew, took custody of ''La Amistad'' and the Africans.

Taking them to the Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound is a sound (geography), marine sound and tidal estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It lies predominantly between the U.S. state of Connecticut to the north and Long Island in New York (state), New York to the south. From west to east, ...

port of New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River in New London County, Connecticut, which empties into Long Island Sound. The cit ...

, Lieutenant Gedney presented officials with a written claim for his property rights under international admiralty law

Maritime law or admiralty law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and conflict of laws, private international law governing the relations ...

for salvage of the vessel, the cargo, and the Africans. Gedney allegedly chose to land in Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

because slavery was still technically legal there, under the state's gradual abolition law, unlike in nearby New York State. He hoped to profit from sale of the Africans. Gedney transferred the captured Africans into the custody of the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut

The United States District Court for the District of Connecticut (in case citations, D. Conn.) is the federal district court whose jurisdiction is the state of Connecticut. The court has offices in Bridgeport, Hartford, and New Haven. Appeal ...

, where legal proceedings began.

Parties

* Lt. Thomas R. Gedney filed alibel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

(a lawsuit

A lawsuit is a proceeding by one or more parties (the plaintiff or claimant) against one or more parties (the defendant) in a civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today ...

in admiralty law) for salvage rights to the African captives and cargo on board ''La Amistad'' as property seized on the high seas.

* Henry Green and Pelatiah Fordham filed a libel for salvage and claimed that they had been the first to discover ''La Amistad''.

* José Ruiz and Pedro Montes filed libels requesting their property of "slaves" and cargo to be returned to them.

* The Office of the United States Attorney for the District of Connecticut, representing the Spanish government, libelled for the "slaves," cargo, and vessel to be returned to Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

as its property.

* Antonio Vega, vice-consul of Spain, libelled for "the slave Antonio" on the grounds that the man was his personal property.''US v. The Amistad'', p. 589

* The Africans denied that they were slaves or property and argued that the court could not "return" them to the control of the government of Spain.

* José Antonio Tellincas, with Aspe and Laca, claimed other goods on board ''La Amistad''.

British pressure

As the British had entered into a treaty with Spain prohibiting the slave trade north of the equator, they considered it a matter ofinternational law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

for the United States to release the Africans. The British applied diplomatic pressure to achieve that such as invoking the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

with the U.S., which jointly enforced their respective prohibitions against the international slave trade.

While the legal battle continued, Dr. Richard Robert Madden, "who served on behalf of the British commission to suppress the African slave trade in Havana," arrived to testify. He made a deposition "that some twenty-five thousand slaves were brought into Cuba every year – with the wrongful compliance of, and personal profit by, Spanish officials." Madden also "told the court that his examinations revealed that the defendants were brought directly from Africa and could not have been residents of Cuba," as the Spanish had claimed. Madden, who later had an audience with Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

concerning the case, conferred with the British Minister in Washington, D.C., Henry Stephen Fox, who pressured U.S. Secretary of State John Forsyth on behalf "of her Majesty's Government."

Fox wrote:

Forsyth responded that under the separation of powers in the U.S. Constitution, the President could not influence the court case. He said that the question of whether the "negroes of the Amistad" had been enslaved in violation of the Treaty was still an open one, "and this Government would with great reluctance erect itself into a tribunal to investigate such questions between two friendly sovereigns." He noted that when the facts were determined, they could be taken into account. He suggested that if the Court found for Spanish rights of property, the Africans would be returned to Cuba. Great Britain and Spain could then argue their questions of law and treaties between them.

Spanish argument

Secretary of State Forsyth requested from the Spanish minister, Chevalier de Argaiz, "a copy of the laws now in force in the island of Cuba relative to slavery." In response, the Captain General of Cuba sent Argaiz "everything on the subject, which had been determined since the treaty concluded in 1818 between Spain and England." The minister also expressed dismay that the Africans had not already been returned to Spanish control. The Spanish maintained that none but a Spanish court could have jurisdiction over the case. The minister stated, "I do not, in fact, understand how a foreign court of justice can be considered competent to take cognizance of an offence committed on board of a Spanish vessel, by Spanish subjects, and against Spanish subjects, in the waters of a Spanish territory; for it was committed on the coasts of this island, and under the flag of this nation." The minister noted that the Spanish had recently turned over American sailors "belonging to the crew of the American vessel 'William Engs,'" whom it had tried by request of their captain and the American consul. The sailors had been found guilty of mutiny and sentenced to "four years' confinement in a fortress." Other American sailors had protested, and when the American ambassador raised the issue with the Spaniards, on March 20, 1839, "her Majesty, having taken into consideration all the circumstances, decided that the said seamen should be placed at the disposition of the American consul, seeing that the offence was committed in one of the vessels and under the flag of his nation, and not on shore." The Spaniards asked how if America had demanded that the sailors in an American ship be turned over to them despite being in a Spanish port, they could now try the Spanish mutineers. The Spaniards held that just as America had ended its importation of African slaves but maintained a legal domestic population, so too had Cuba. It was up to Spanish courts to determine "whether the Negroes in question" were legal or illegal slaves under Spanish law, "but never can this right justly belong to a foreign country." The Spaniards maintained that even if it was believed that the Africans were being held as slaves in violation of "the celebrated treaty of humanity concluded between Spain and Great Britain in 1835," it would be a violation of "the laws of Spain; and the Spanish Government, being as scrupulous as any other in maintaining the strict observance of the prohibitions imposed on, or the liberties allowed to, its subjects by itself, will severely chastise those of them who fail in their duties." The Spaniards pointed out that by American law, the jurisdiction over avessel on the high seas, in time of peace, engaged in a lawful voyage, is, according to the laws of nations, under the exclusive jurisdiction of the State to which her flag belongs; as much so as if constituting a part of its own domain. ...if such ship or vessel should be forced, by stress of weather, or other unavoidable cause, into the port and under the jurisdiction of a friendly Power, she, and her cargo, and persons on board, with their property, and all the rights belonging to their personal relations as established by the laws of the State to which they belong, would be placed under the protection which the laws of nations extend to the unfortunate under such circumstances.The Spaniards demanded that the U.S. "apply these proper principles to the case of the schooner ''Amistad''." The Spanish were further encouraged that their view would win by U.S. Senator

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Born in South Carolina, he adamantly defended American s ...

and the Senate's Committee of Foreign Relations on April 15, 1840, issuing a statement announcing complete "conformity between the views entertained by the Senate, and the arguments urged by the panish MinisterChevalier de Argaiz" concerning ''La Amistad''.

Applicable law

The Spanish categorized the Africans as property to have the case fall underPinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795, by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

of 1795. They protested when Judge William Jay construed a statement by their Minister as seeming to demand

: "the surrender of the negroes apprehended on board the schooner ''Amistad'', as murderers, and not as property; that is to say founding his demand on the law of nations

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of rules, norms, legal customs and standards that states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generally do, obey in their mutual relations. In in ...

, and not on the treaty of 1795."

The Spanish pointed out that the statement to which Jay was referring was one of the Spanish minister "speaking of the crime committed by the negroes lave revolt and the punishment which they merit." They went on to point out that the minister had stated that a payment to compensate the owners "would be a slender compensation; for though the property should remain, as it ought to remain, unimpaired, public vengeance would be frustrated."

Judge Jay took issue with the Spanish minister's request for the Africans to be turned over to Spanish authorities, which seemed to imply that they were fugitives instead of misbehaving property, since the 1795 treaty stated that property should be restored directly to the control of its owners. The Spanish denied that it meant that the minister had waived the contention of them being property.

By insisting that the case fell under the treaty, the Spanish were invoking the Supremacy Clause

The Supremacy Clause of the Constitution of the United States ( Article VI, Clause 2) establishes that the Constitution, federal laws made pursuant to it, and treaties made under its authority, constitute the "supreme Law of the Land", and th ...

of the U.S. Constitution, which would put the clauses of the treaty above the state laws of Connecticut or New York, where the ship had been taken into custody

: "no one who respects the laws of the country ought to oppose the execution of the treaty, which is the supreme law of the country."

However, at that point the case had already risen out of the states' courts, into federal district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district. Each district covers one U.S. state or a portion of a state. There is at least one feder ...

.

The Spanish also sought to avoid talk about the law of nations, as some of their opponents argued that it included a duty by the U.S. to treat the Africans with the same deference as would be accorded any other foreign sailors.

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

would argue that issue before the Supreme Court in 1841:

: The Africans were in possession, and had the presumptive right of ownership; they were in peace with the United States: ... they were not pirates; they were on a voyage to their native homes ... the ship was theirs, and being in immediate communication with the shore, was in the territory of the State of New York; or, if not, at least half the number were actually on the soil of New York, and entitled to all the provisions of the law of nations, and the protection and comfort which the laws of that State secure to every human being within its limits.

When pressed with questions concerning the law of nations, the Spanish referred to a concept of Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius ( ; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Hugo de Groot () or Huig de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman, poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft an ...

, who is credited as one of the originators of the law of nations. Specifically, they noted that

: "the usage, then, of demanding fugitives from a foreign Government, is confined ... to crimes which affect the Government and such as are of extreme atrocity."

Initial court proceedings

A case before the

A case before the circuit court

Circuit courts are court systems in several common law jurisdictions. It may refer to:

* Courts that literally sit 'on circuit', i.e., judges move around a region or country to different towns or cities where they will hear cases;

* Courts that s ...

in Hartford

Hartford is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. The city, located in Hartford County, Connecticut, Hartford County, had a population of 121,054 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ce ...

, Connecticut, was filed in September 1839, charging the Africans with mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

and murder on ''La Amistad''. Roger Sherman Baldwin

Roger Sherman Baldwin (January 4, 1793 – February 19, 1863) was an American politician who served as the 32nd Governor of Connecticut from 1844 to 1846 and a United States senator from 1847 to 1851. As a lawyer, his career was most notable ...

, an attorney from New Haven who had served on that city's town board as well as in the state legislature, represented the Africans.

The court ruled that it lacked jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' and 'speech' or 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, the concept of jurisdiction applies at multiple level ...

, because the alleged acts took place on a Spanish ship in Spanish waters. It was entered into the docket books of the federal court as ''United States'' v. ''Cinque, et al.''

Various parties filed property claims with the district court

District courts are a category of courts which exists in several nations, some call them "small case court" usually as the lowest level of the hierarchy.

These courts generally work under a higher court which exercises control over the lower co ...

to many of the African captives, to the ship, and to its cargo: Ruiz and Montez, Lieutenant Gedney, and Captain Henry Green (who had met the Africans while on shore on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

and claimed to have helped in their capture). The Spanish government asked that the ship, cargo, and African captives be restored to Spain under the Pinckney treaty of 1795 between Spain and the United States. Article 9 of the treaty held that

: "all ships and merchandises of what nature soever, which shall be rescued out of the hands of pirates or robbers on the high seas, ... shall be restored, entire, to the true proprietor."

The United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

filed a claim on behalf of Spain.

The abolitionist movement had formed the "''Amistad'' Committee," headed by the New York City merchant Lewis Tappan, and had collected money to mount a defense of the Africans. Initially, communication with the Africans was difficult since they spoke neither English nor Spanish. Professor J.W. Gibbs learned from the Africans to count to ten in their

The abolitionist movement had formed the "''Amistad'' Committee," headed by the New York City merchant Lewis Tappan, and had collected money to mount a defense of the Africans. Initially, communication with the Africans was difficult since they spoke neither English nor Spanish. Professor J.W. Gibbs learned from the Africans to count to ten in their Mende language

Mende (''Mɛnde yia'') is a major language of Sierra Leone, with some speakers in neighboring Liberia and Guinea. It is spoken by the Mende people and by other ethnic groups as a regional lingua franca in southern Sierra Leone.

Mende is a tona ...

. He went to the docks of New York City and counted aloud in front of sailors until he located a person able to understand and translate. He found James Covey, a twenty-year-old sailor on the British man-of-war . Covey was a formerly enslaved person from West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

.

The abolitionists filed charges of assault, kidnapping

Kidnapping or abduction is the unlawful abduction and confinement of a person against their will, and is a crime in many jurisdictions. Kidnapping may be accomplished by use of force or fear, or a victim may be enticed into confinement by frau ...

, and false imprisonment

False imprisonment or unlawful imprisonment occurs when a person intentionally restricts another person's movement within any area without legal authority, justification, or the restrained person's permission.

Actual physical restraint is n ...

against Ruiz and Montes. Their arrest in New York City in October 1839 outraged pro-slavery advocates and the Spanish government. Montes immediately posted bail and went to Cuba. Ruiz, being

: "more comfortable in a New England setting (and entitled to many amenities not available to the Africans), hoped to garner further public support by staying in jail. ... Ruiz, however, soon tired of his martyred lifestyle in jail and posted bond. Like Montes, he returned to Cuba."

Outraged, the Spanish minister, Cavallero Pedro Alcántara Argaiz, made

: "caustic accusations against America's judicial system and continued to condemn the abolitionist affront. Ruiz's imprisonment only added to Alcántara's anger, and Alcántara pressured Forsyth to seek ways to throw out the case altogether."

The Spanish held that the bailbonds that the men had to acquire so that they could leave jail and return to Cuba caused them a grave financial burden, and

: "by the treaty of 1795, no obstacle or impediment o leave the U.S.should have eenplaced" n their way

On January 7, 1840, all of the parties, with the Spanish minister representing Ruiz and Montes, appeared before the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut and presented their arguments.''U.S.'' v. ''The Amistad'', p. 590

The abolitionists' main argument before the district court was that a treaty between Britain and Spain in 1817 and a subsequent pronouncement by the Spanish government had outlawed the slave trade across the Atlantic. They established that the slaves had been captured in Mendiland (also spelled Mendeland, now Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

) in Africa, sold to a Portuguese trader in Lomboko (south of Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

) in April 1839, and taken to Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

, a Democrat, sided with the Spanish position. He ordered the schooner USS ''Grampus'' to New Haven Harbor to return the Africans to Cuba immediately after a favorable decision, before any appeals could be decided.

Contrary to Van Buren's plan, the district court, led by judge Andrew T. Judson, ruled in favor of the abolitionists and the Africans' position. In January 1840, Judson ordered for the Africans to be returned to their homeland by the U.S. government, and for one third of ''La Amistad'' and its cargo to be given to Lieutenant Gedney as salvage property. (The federal government had outlawed the slave trade between the U.S. and other countries in 1808; an 1818 law, as amended in 1819, provided for the return of all illegally-traded slaves.)

Antonio, the deceased captain's personal slave, was declared the rightful property of the captain's heirs and was ordered restored to Cuba. Contrary to Sterne's 1953 fictional account that describes Antonio willingly returning to Cuba, Smithsonian sources report that he escaped to New York, or to Canada, with the help of an abolitionist group.

In detail, the District Court ruled as follows:

* It rejected the claim of the U.S. Attorney, who argued on behalf of the Spanish minister for the restoration of the "slaves".

* It dismissed the claims of Ruiz and Montez.

* It ordered that the captives be delivered to the custody of the U.S. president for transportation to Africa since they were in fact legally free.

* It allowed the Spanish vice-consul to claim the slave Antonio.

* It allowed Lt. Gedney to claim one third of the property on board ''La Amistad''.

* It allowed Tellincas, Aspe, and Laca to claim one third of the property.

* It dismissed the claims made by Green and Fordham for salvage rights.

The U.S. Attorney for the District of Connecticut, by order of Van Buren, immediately appealed to the U.S. circuit court for the Connecticut district. He challenged every part of the district court's ruling, except the concession of the slave Antonio to the Spanish vice-consul. Tellincas, Aspe, and Laca also appealed to gain a greater portion of the salvage value. Ruiz and Montez and the owners of ''La Amistad'' did not appeal.

In April 1840 the Circuit Court of Appeals, in turn, upheld the district court's decision. The U.S. Attorney appealed the federal government's case to the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

.

Arguments before Supreme Court

On February 22, 1841,U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government. The attorney general acts as the principal legal advisor to the president of the ...

Henry D. Gilpin began the oral argument phase before the Supreme Court. Gilpin first entered into evidence the papers of ''La Amistad'', which stated that the Africans were Spanish property. Gilpin argued that the Court had no authority to rule against the validity of the documents. Gilpin contended that if the Africans were slaves, as indicated by the documents, they must be returned to their rightful owner, the Spanish government. Gilpin's argument lasted two hours.Clifton Johnson, "The Amistad Case and Its Consequences in U.S. History"Amistad Research Center – Essays, Tulane University

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, a former U.S. president who was then a U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

from Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, had agreed to argue for the Africans. When it was time for him to argue, he said that he felt ill-prepared. Roger Sherman Baldwin

Roger Sherman Baldwin (January 4, 1793 – February 19, 1863) was an American politician who served as the 32nd Governor of Connecticut from 1844 to 1846 and a United States senator from 1847 to 1851. As a lawyer, his career was most notable ...

, who had already represented the captives in the lower cases, opened in his place.

Baldwin, a prominent attorney, contended that the Spanish government was trying to manipulate the Supreme Court to return "fugitives." He argued that the Spanish government sought the return of slaves who had been freed by the district court but was not appealing the fact of their having been freed. Covering all the facts of the case, Baldwin spoke for four hours over the course of February 22 and 23. (He was of no relation to the Court's Justice Henry Baldwin.)

Adams rose to speak on February 24. He reminded the Court that it was a part of the judicial branch

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

and not part of the executive. Introducing copies of correspondence between the Spanish government and Secretary of State John Forsyth, he criticized President Van Buren for his assumption of unconstitutional

In constitutional law, constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applic ...

powers in the case:

Adams argued that neither Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795, by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

nor the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p. 168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to ...

applied to the case. Article IX of Pinckney's Treaty referred only to property and did not apply to people. As to '' The Antelope'' decision (10 Wheat. 124), which recognized "that possession on board of a vessel was evidence of property," Adams said that did not apply either since the precedent was established prior to the prohibition of the foreign slave trade by the United States. Adams concluded on March 1 after eight-and-a-half hours of speaking. (The Court had taken a recess following the death of Associate Justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

Barbour on February 25.)

Attorney General Gilpin concluded oral arguments with a three-hour rebuttal on March 2. The Court retired to consider the case.

Decision

Associate JusticeJoseph Story

Joseph Story (September18, 1779September10, 1845) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin ...

delivered the Court's decision on March 9. Article IX of Pinckney's Treaty was ruled inapplicable, since the Africans in question had never been legal property. They were not criminals, as the U.S. Attorney's Office argued, but rather

: "unlawfully kidnapped, and forcibly and wrongfully carried on board a certain vessel."

The documents submitted by Attorney General Gilpin were evidence not of property but rather of fraud on the part of the Spanish government. Lt. Gedney and the USS ''Washington'' were to be awarded salvage from the vessel for having performed "a highly meritorious and useful service to the proprietors of the ship and cargo."''U.S.'' v. ''The Amistad'', p. 597 When ''La Amistad'' anchored near Long Island, however, the Court believed it to be in the possession of the Africans on board, who had never intended to become slaves. Therefore, the Adams-Onís Treaty did not apply and so the President was not required by that law to cover the expense of returning the Africans to Africa.

In his judgment, Story wrote:

Aftermath and significance

The Africans greeted the news of the Supreme Court's decision with joy. Abolitionist supporters took the survivors – 36 men and boys and three girls – to Farmington, a village considered "Grand Central Station" on the

The Africans greeted the news of the Supreme Court's decision with joy. Abolitionist supporters took the survivors – 36 men and boys and three girls – to Farmington, a village considered "Grand Central Station" on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

. Its residents had agreed to have the Africans stay there until they could return to their homeland. Some households took them in; supporters also provided barracks for them.

The Amistad Committee instructed the Africans in English and Christianity, and raised funds to pay for their return home. One missionary was James Steele, an Oberlin graduate, previously one of the Lane Rebels

Lane Seminary, sometimes called Cincinnati Lane Seminary, and later renamed Lane Theological Seminary, was a Presbyterian theological college that operated from 1829 to 1932 in Walnut Hills, Ohio, today a neighborhood in Cincinnati. Its campus ...

. In 1841, he joined the Amistad Mission to Mendhi, which returned freed slaves to Africa and worked to establish a mission there. However, Steele soon found that the Amistad captives belonged to seven different tribes, some at war with one another. All of the chiefs were slave traders and authorized to re-enslave freed persons. These findings led to the decision that the mission must start in Sierra Leone, under the protection of the British.

Along with several missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

, in 1842 the surviving 35 Africans returned to Sierra Leone, the others having died at sea or while awaiting trial. The Americans constructed a mission in Mendiland. Former members of the Amistad Committee later founded the American Missionary Association

The American Missionary Association (AMA) was a Protestant-based abolitionist group founded on in Albany, New York. The main purpose of the organization was abolition of slavery, education of African Americans, promotion of racial equality, and ...

, an integrated evangelical organization that continued to support both the Mendi mission and the abolitionist movement.

In the following years, the Spanish government continued to press the U.S. for compensation for the ship, cargo, and slaves. Several Southern lawmakers introduced resolutions into the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

to appropriate money for such payment but failed to gain passage, although it was supported by presidents James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

and James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

.

Joseph Cinqué returned to Africa. In his final years, he was reported to have returned to the mission and re-embraced Christianity. Recent historical research suggests that the allegations of Cinqué's later involvement in the slave trade are false.

In the ''Creole'' case of 1841, the United States dealt with another ship rebellion similar to that of ''La Amistad.''

The U.S. had prohibited the international slave trade in 1808, but ended domestic slavery only in 1865 with the Thirteenth Amendment. Connecticut had a gradual abolition law passed in 1797; children born to slaves were free but had to serve apprenticeships until young adulthood; the last slaves were freed in 1848.

In popular culture

In 1998, a memorial was installed at the Montauk Point Lighthouse to commemorate the Amistad. On August 26, 2023, the Montauk Historical Society, together with the Eastville Community Historical Society and the Southampton African-American Museum, erected a historic marker near Culloden Point in Montauk where the Amistad was anchored in 1839. The revolt aboard ''La Amistad,'' the background of the slave trade and its subsequent trial is retold in a celebrated poem by Robert Hayden entitled "

The revolt aboard ''La Amistad,'' the background of the slave trade and its subsequent trial is retold in a celebrated poem by Robert Hayden entitled "Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of Africans sold for enslavement were forcibly transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manu ...

", first published in 1962. Howard Jones published '' Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy'' in 1987.

A movie, '' Amistad'' (1997), was based on the events of the revolt and court cases, and Howard Jones' 1987 book '' Mutiny on the Amistad''.

African-American artist Hale Woodruff painted murals portraying events related to the revolt on ''La Amistad'' in 1938, for Talladega College

Talladega College is a Private college, private, Historically black colleges and universities, historically black college in Talladega, Alabama. It is Alabama's oldest private historically black college and offers 17 degree programs. It is accred ...

in Alabama. A statue of Cinqué was erected beside the City Hall building in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound. With a population of 135,081 as determined by the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, New Haven is List ...

in 1992. There is an ''Amistad'' memorial at Montauk Point State Park

Montauk Point State Park is a state park located in the hamlet of Montauk, at the eastern tip of Long Island in the Town of East Hampton, Suffolk County, New York. Montauk Point is the easternmost extremity of the South Fork of Long Island ...

on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

.

In 2000, '' Freedom Schooner Amistad'', a ship replica, was launched in Mystic, Connecticut

Mystic is a village and census-designated place (CDP) in Groton and Stonington, Connecticut, United States.

Mystic was a significant Connecticut seaport with more than 600 ships built over 135 years starting in 1784. Mystic Seaport, located in ...

. The Historical Society of Farmington, Connecticut

Farmington is a town in Hartford County, Connecticut, Hartford County in the Farmington Valley area of central Connecticut in the United States. The town is part of the Capitol Planning Region, Connecticut, Capitol Planning Region. The populati ...

offers walking tours of village houses that housed the Africans while funds were collected for their return home. The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University

The Tulane University of Louisiana (commonly referred to as Tulane University) is a private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by a cohort of medical doctors, it b ...

in New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, has numerous resources for research into slavery, abolition, and African Americans.

See also

* Amistad Research Center * American slave court cases * John Quincy Adams and abolitionism * Mendi BibleNotes

References

* * * * *External links

* *"Courtroom portraits of the ''Amistad'' captives drawn by New Haven resident William H. Townsend while the prisoners awaited trial"

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

Amistad Ctr

1841, e-text, University of North Carolina

Gilder Lehrman Center, Yale Univ

Cornell University (include

"''Amistad'' Court Records Online"

Footnote

"The ''Amistad'' Case"

the University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School {{Taney Court Conflicts in 1841 1841 in United States case law Pre-emancipation African-American history Freedom suits in the United States Legal history of Connecticut Farmington, Connecticut Mutinies United States maritime case law International maritime incidents Legal history of Spain La Amistad 1841 in Connecticut Maritime incidents in the United States United States Supreme Court cases of the Taney Court African-American history of Connecticut Spain–United States relations Fugitive American slaves United States Supreme Court cases