United States Bill of Rights on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten

Following the Philadelphia Convention, some leading revolutionary figures such as Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, and

Following the Philadelphia Convention, some leading revolutionary figures such as Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, and

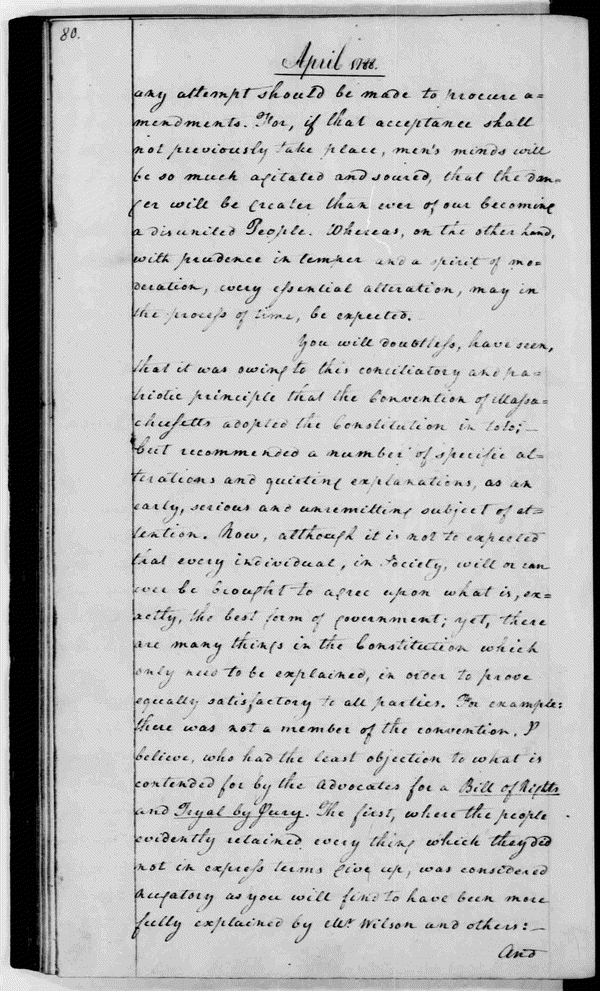

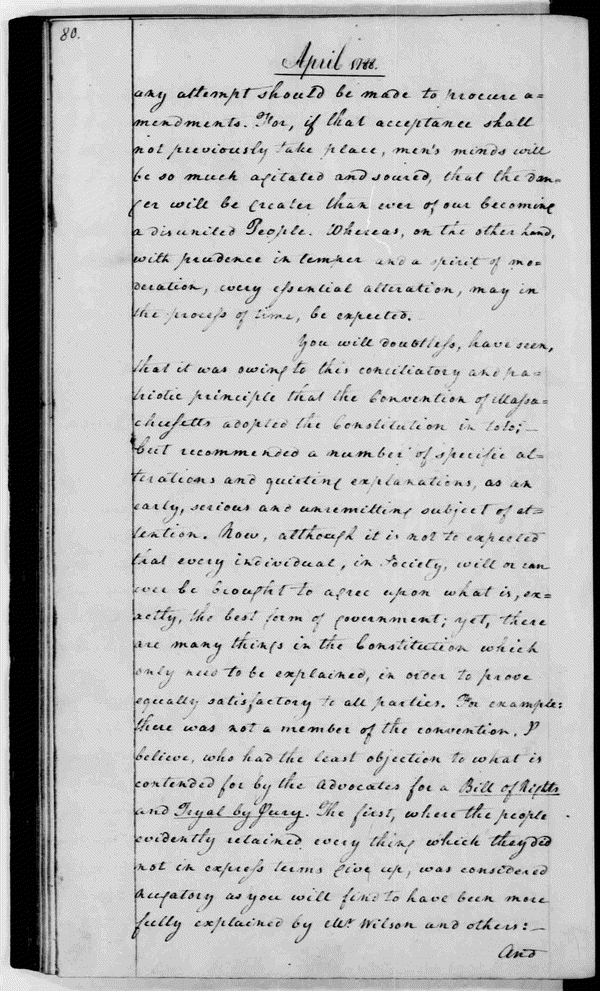

In December 1787 and January 1788, five states—Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut—ratified the Constitution with relative ease, though the bitter minority report of the Pennsylvania opposition was widely circulated. In contrast to its predecessors, the Massachusetts convention was angry and contentious, at one point erupting into a fistfight between Federalist delegate Francis Dana and Anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry when the latter was not allowed to speak. The impasse was resolved only when revolutionary heroes and leading Anti-Federalists Samuel Adams and John Hancock agreed to ratification on the condition that the convention also propose amendments. The convention's proposed amendments included a requirement for grand jury indictment in capital cases, which would form part of the Fifth Amendment, and an amendment reserving powers to the states not expressly given to the federal government, which would later form the basis for the Tenth Amendment.

Following Massachusetts' lead, the Federalist minorities in both Virginia and New York were able to obtain ratification in convention by linking ratification to recommended amendments. A committee of the Virginia convention headed by law professor

In December 1787 and January 1788, five states—Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut—ratified the Constitution with relative ease, though the bitter minority report of the Pennsylvania opposition was widely circulated. In contrast to its predecessors, the Massachusetts convention was angry and contentious, at one point erupting into a fistfight between Federalist delegate Francis Dana and Anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry when the latter was not allowed to speak. The impasse was resolved only when revolutionary heroes and leading Anti-Federalists Samuel Adams and John Hancock agreed to ratification on the condition that the convention also propose amendments. The convention's proposed amendments included a requirement for grand jury indictment in capital cases, which would form part of the Fifth Amendment, and an amendment reserving powers to the states not expressly given to the federal government, which would later form the basis for the Tenth Amendment.

Following Massachusetts' lead, the Federalist minorities in both Virginia and New York were able to obtain ratification in convention by linking ratification to recommended amendments. A committee of the Virginia convention headed by law professor

The 1st United States Congress, which met in New York City's

The 1st United States Congress, which met in New York City's

(After failing to ratify the 12 amendments during the 1789 legislative session.) Having been approved by the requisite three-fourths of the several states, there being 14 States in the Union at the time (as Vermont had been admitted into the Union on March 4, 1791), the ratification of Articles Three through Twelve was completed and they became Amendments 1 through 10 of the Constitution. Congress, now meeting at

slip op.

at 24 (U.S. June 26, 2015).

online

* Cogan, Neil H. (2015). ''The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins.'' Second edition. New York: Oxford University Press. * * * * Stevens, John Paul. "Keynote Address: The Bill of Rights: A Century of Progress." ''University of Chicago Law Review'' 59 (1992): 13

online

.

* Footnote.com (partners with the National Archives)

Online viewer with High-resolution image of the original document

* Library of Congress

on opposition to the Bill of Rights * TeachingAmericanHistory.org �

Bill of Rights

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Bill Of Rights, United States 1st United States Congress 1791 in American politics 1791 in American law Amendments to the United States Constitution American Enlightenment George Mason James Madison United States Bill of Rights Government documents of the United States Presidency of George Washington Constitution of the United States

amendments An amendment is a formal or official change made to a law, contract, constitution, or other legal document. It is based on the verb to amend, which means to change for better. Amendments can add, remove, or update parts of these agreements. The ...

to the United States Constitution. Proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the ratification of the Constitution and written to address the objections raised by Anti-Federalists, the Bill of Rights amendments add to the Constitution specific guarantees of personal freedoms and rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory ...

, clear limitations on the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and explicit declarations that all powers not specifically granted to the federal government by the Constitution are reserved to the states or the people

A person ( : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of prope ...

. The concepts codified in these amendments are built upon those in earlier documents, especially the Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted in 1776 to proclaim the inherent rights of men, including the right to reform or abolish "inadequate" government. It influenced a number of later documents, including the United States Declaratio ...

(1776), as well as the Northwest Ordinance (1787), the English Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights 1689 is an Act of the Parliament of England, which sets out certain basic civil rights and clarifies who would be next to inherit the Crown, and is seen as a crucial landmark in English constitutional law. It received Royal ...

(1689), and Magna Carta (1215).

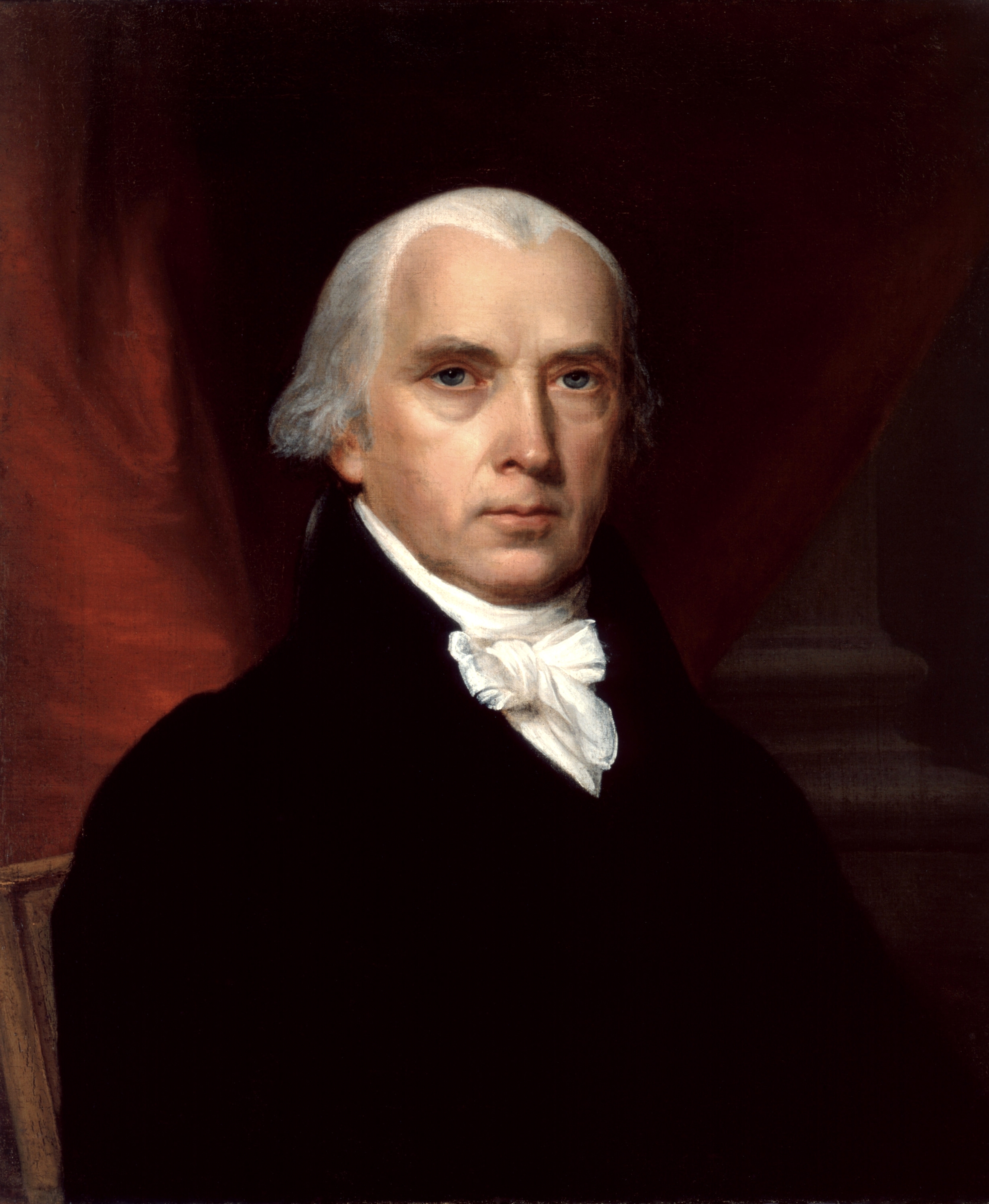

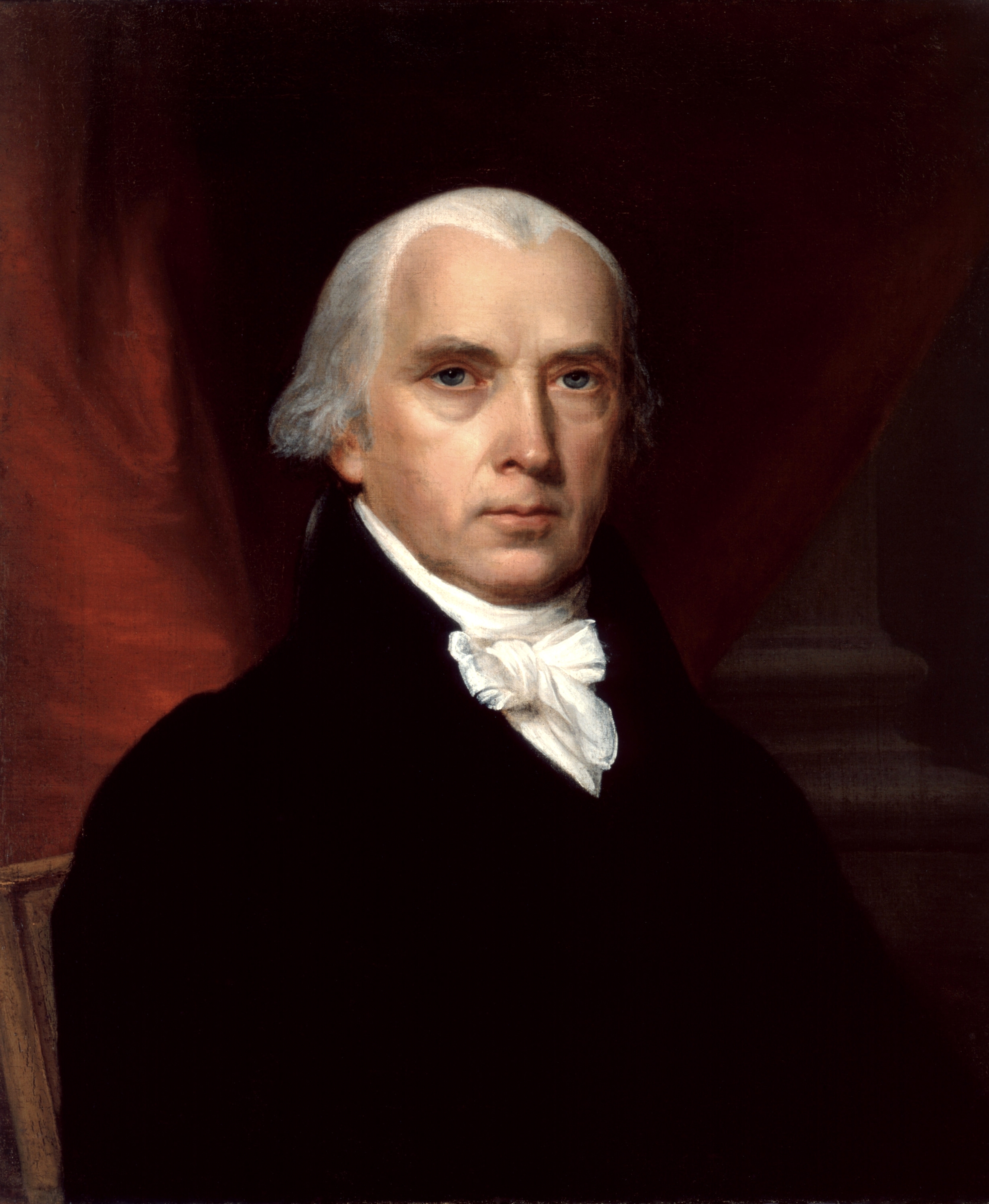

Largely because of the efforts of Representative James Madison, who studied the deficiencies of the Constitution pointed out by anti-federalists and then crafted a series of corrective proposals, Congress approved twelve articles of amendment on September 25, 1789, and submitted them to the states for ratification. Contrary to Madison's proposal that the proposed amendments be incorporated into the main body of the Constitution (at the relevant articles and sections of the document), they were proposed as supplemental additions (codicils) to it. Articles Three through Twelve were ratified as additions to the Constitution on December 15, 1791, and became Amendments One through Ten of the Constitution. Article Two became part of the Constitution on May 5, 1992, as the Twenty-seventh Amendment. Article One is still pending before the states.

Although Madison's proposed amendments included a provision to extend the protection of some of the Bill of Rights to the states, the amendments that were finally submitted for ratification applied only to the federal government. The door for their application upon state governments was opened in the 1860s, following ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. Since the early 20th century both federal and state courts have used the Fourteenth Amendment to apply portions of the Bill of Rights to state and local governments. The process is known as incorporation.

There are several original engrossed

Western calligraphy is the art of writing and penmanship

as practiced in the Western world, especially using the Latin alphabet (but also including calligraphic use of the Cyrillic and Greek alphabets, as opposed to "Eastern" traditions such as ...

copies of the Bill of Rights still in existence. One of these is on permanent public display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Background

Philadelphia Convention

Prior to the ratification and implementation of the United States Constitution, the thirteen sovereign states followed the Articles of Confederation, created by the Second Continental Congress and ratified in 1781. However, the national government that operated under the Articles of Confederation was too weak to adequately regulate the various conflicts that arose between the states. The Philadelphia Convention set out to correct weaknesses of the Articles that had been apparent even before theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

had been successfully concluded.

The convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. Although the Convention was purportedly intended only to revise the Articles, the intention of many of its proponents, chief among them James Madison of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and Alexander Hamilton of New York, was to create a new government rather than fix the existing one. The convention convened in the Pennsylvania State House, and George Washington of Virginia was unanimously elected as president of the convention. The 55 delegates who drafted the Constitution are among the men known as the Founding Fathers of the new nation. Thomas Jefferson, who was Minister to France during the convention, characterized the delegates as an assembly of "demi-gods." Rhode Island refused to send delegates to the convention.

On September 12, George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of the three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including ...

of Virginia suggested the addition of a Bill of Rights to the Constitution modeled on previous state declarations, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

made it a formal motion. However, after only a brief discussion where Roger Sherman pointed out that State Bills of Rights were not repealed by the new Constitution, the motion was defeated by a unanimous vote of the state delegations. Madison, then an opponent of a Bill of Rights, later explained the vote by calling the state bills of rights "parchment barriers" that offered only an illusion of protection against tyranny. Another delegate, James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, later argued that the act of enumerating the rights of the people would have been dangerous, because it would imply that rights not explicitly mentioned did not exist; Hamilton echoed this point in '' Federalist'' No. 84.

Because Mason and Gerry had emerged as opponents of the proposed new Constitution, their motion—introduced five days before the end of the convention—may also have been seen by other delegates as a delaying tactic. The quick rejection of this motion, however, later endangered the entire ratification process. Author David O. Stewart characterizes the omission of a Bill of Rights in the original Constitution as "a political blunder of the first magnitude" while historian Jack N. Rakove calls it "the one serious miscalculation the framers made as they looked ahead to the struggle over ratification".

Thirty-nine delegates signed the finalized Constitution. Thirteen delegates left before it was completed, and three who remained at the convention until the end refused to sign it: Mason, Gerry, and Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

of Virginia. Afterward, the Constitution was presented to the Articles of Confederation Congress with the request that it afterwards be submitted to a convention of delegates, chosen in each State by the people, for their assent and ratification.

Anti-Federalists

Richard Henry Lee

Richard Henry Lee (January 20, 1732June 19, 1794) was an American statesman and Founding Father from Virginia, best known for the June 1776 Lee Resolution, the motion in the Second Continental Congress calling for the colonies' independence f ...

publicly opposed the new frame of government, a position known as "Anti-Federalism". Elbridge Gerry wrote the most popular Anti-Federalist tract, "Hon. Mr. Gerry's Objections", which went through 46 printings; the essay particularly focused on the lack of a bill of rights in the proposed Constitution. Many were concerned that a strong national government was a threat to individual rights

Group rights, also known as collective rights, are rights held by a group '' qua'' a group rather than individually by its members; in contrast, individual rights are rights held by individual people; even if they are group-differentiated, which ...

and that the President would become a king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

. Jefferson wrote to Madison advocating a Bill of Rights: "Half a loaf is better than no bread. If we cannot secure all our rights, let us secure what we can." The pseudonymous Anti-Federalist "Brutus" (probably Robert Yates) wrote,

He continued with this observation:

Federalists

Supporters of the Constitution, known as Federalists, opposed a bill of rights for much of the ratification period, in part because of the procedural uncertainties it would create. Madison argued against such an inclusion, suggesting that state governments were sufficient guarantors of personal liberty, in No. 46 of '' The Federalist Papers'', a series of essays promoting the Federalist position. Hamilton opposed a bill of rights in ''The Federalist No. 84'', stating that "the constitution is itself in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, a bill of rights." He stated that ratification did not mean the American people were surrendering their rights, making protections unnecessary: "Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing, and as they retain everything, they have no need of particular reservations." Patrick Henry criticized the Federalist point of view, writing that the legislature must be firmly informed "of the extent of the rights retained by the people ... being in a state of uncertainty, they will assume rather than give up powers by implication." Other anti-Federalists pointed out that earlier political documents, in particular the Magna Carta, had protected specific rights. In response, Hamilton argued that the Constitution was inherently different:Massachusetts compromise

In December 1787 and January 1788, five states—Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut—ratified the Constitution with relative ease, though the bitter minority report of the Pennsylvania opposition was widely circulated. In contrast to its predecessors, the Massachusetts convention was angry and contentious, at one point erupting into a fistfight between Federalist delegate Francis Dana and Anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry when the latter was not allowed to speak. The impasse was resolved only when revolutionary heroes and leading Anti-Federalists Samuel Adams and John Hancock agreed to ratification on the condition that the convention also propose amendments. The convention's proposed amendments included a requirement for grand jury indictment in capital cases, which would form part of the Fifth Amendment, and an amendment reserving powers to the states not expressly given to the federal government, which would later form the basis for the Tenth Amendment.

Following Massachusetts' lead, the Federalist minorities in both Virginia and New York were able to obtain ratification in convention by linking ratification to recommended amendments. A committee of the Virginia convention headed by law professor

In December 1787 and January 1788, five states—Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut—ratified the Constitution with relative ease, though the bitter minority report of the Pennsylvania opposition was widely circulated. In contrast to its predecessors, the Massachusetts convention was angry and contentious, at one point erupting into a fistfight between Federalist delegate Francis Dana and Anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry when the latter was not allowed to speak. The impasse was resolved only when revolutionary heroes and leading Anti-Federalists Samuel Adams and John Hancock agreed to ratification on the condition that the convention also propose amendments. The convention's proposed amendments included a requirement for grand jury indictment in capital cases, which would form part of the Fifth Amendment, and an amendment reserving powers to the states not expressly given to the federal government, which would later form the basis for the Tenth Amendment.

Following Massachusetts' lead, the Federalist minorities in both Virginia and New York were able to obtain ratification in convention by linking ratification to recommended amendments. A committee of the Virginia convention headed by law professor George Wythe

George Wythe (; December 3, 1726 – June 8, 1806) was an American academic, scholar and judge who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The first of the seven signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence from ...

forwarded forty recommended amendments to Congress, twenty of which enumerated individual rights and another twenty of which enumerated states' rights. The latter amendments included limitations on federal powers to levy taxes and regulate trade.

A minority of the Constitution's critics, such as Maryland's Luther Martin, continued to oppose ratification. However, Martin's allies, such as New York's John Lansing, Jr., dropped moves to obstruct the Convention's process. They began to take exception to the Constitution "as it was", seeking amendments. Several conventions saw supporters for "amendments before" shift to a position of "amendments after" for the sake of staying in the Union. Ultimately, only North Carolina and Rhode Island waited for amendments from Congress before ratifying.

Article Seven of the proposed Constitution set the terms by which the new frame of government would be established. The new Constitution would become operational when ratified by at least nine states. Only then would it replace the existing government under the Articles of Confederation and would apply only to those states that ratified it.

Following contentious battles in several states, the proposed Constitution reached that nine-state ratification plateau in June 1788. On September 13, 1788, the Articles of Confederation Congress certified that the new Constitution had been ratified by more than enough states for the new system to be implemented and directed the new government to meet in New York City on the first Wednesday in March the following year. On March 4, 1789, the new frame of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

came into force

In law, coming into force or entry into force (also called commencement) is the process by which legislation, regulations, treaties and other legal instruments come to have legal force and effect. The term is closely related to the date of this t ...

with eleven of the thirteen states participating.

New York Circular Letter

In New York, the majority of the Ratifying Convention was Anti-Federalist and they were not inclined to follow the Massachusetts Compromise. Led by Melancton Smith, they were inclined to make the ratification of New York conditional on prior proposal of amendments or, perhaps, insist on the right to secede from the union if amendments are not promptly proposed. Hamilton, after consulting with Madison, informed the Convention that this would not be accepted by Congress. After ratification by the ninth state, New Hampshire, followed shortly by Virginia, it was clear the Constitution would go into effect with or without New York as a member of the Union. In a compromise, the New York Convention proposed to ratify, feeling confident that the states would call for new amendments using the convention procedure in Article V, rather than making this a condition of ratification by New York. John Jay wrote the New York Circular Letter calling for the use of this procedure, which was then sent to all the States. The legislatures in New York and Virginia passed resolutions calling for the convention to propose amendments that had been demanded by the States while several other states tabled the matter to consider in a future legislative session. Madison wrote the Bill of Rights partially in response to this action from the States.Proposal and ratification

Anticipating amendments

The 1st United States Congress, which met in New York City's

The 1st United States Congress, which met in New York City's Federal Hall

Federal Hall is a historic building at 26 Wall Street in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City. The current Greek Revival–style building, completed in 1842 as the Custom House, is operated by the National Park Service as a nat ...

, was a triumph for the Federalists. The Senate of eleven states contained 20 Federalists with only two Anti-Federalists, both from Virginia. The House included 48 Federalists to 11 Anti-Federalists, the latter of whom were from only four states: Massachusetts, New York, Virginia and South Carolina.

Among the Virginia delegation to the House was James Madison, Patrick Henry's chief opponent in the Virginia ratification battle. In retaliation for Madison's victory in that battle at Virginia's ratification convention, Henry and other Anti-Federalists, who controlled the Virginia House of Delegates, had gerrymandered a hostile district for Madison's planned congressional run and recruited Madison's future presidential successor, James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, to oppose him. Madison defeated Monroe after offering a campaign pledge that he would introduce constitutional amendments forming a bill of rights at the First Congress.

Originally opposed to the inclusion of a bill of rights in the Constitution, Madison had gradually come to understand the importance of doing so during the often contentious ratification debates. By taking the initiative to propose amendments himself through the Congress, he hoped to preempt a second constitutional convention that might, it was feared, undo the difficult compromises of 1787, and open the entire Constitution to reconsideration, thus risking the dissolution of the new federal government. Writing to Jefferson, he stated, "The friends of the Constitution, some from an approbation of particular amendments, others from a spirit of conciliation, are generally agreed that the System should be revised. But they wish the revisal to be carried no farther than to supply additional guards for liberty." He also felt that amendments guaranteeing personal liberties would "give to the Government its due popularity and stability". Finally, he hoped that the amendments "would acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion". Historians continue to debate the degree to which Madison considered the amendments of the Bill of Rights necessary, and to what degree he considered them politically expedient; in the outline of his address, he wrote, "Bill of Rights—useful—not essential—".

On the occasion of his April 30, 1789 inauguration as the nation's first president, George Washington addressed the subject of amending the Constitution. He urged the legislators,

Madison's proposed amendments

James Madison introduced a series of Constitutional amendments in the House of Representatives for consideration. Among his proposals was one that would have added introductory language stressing natural rights to the preamble. Another would apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government. Several sought to protect individual personal rights by limiting various Constitutional powers of Congress. Like Washington, Madison urged Congress to keep the revision to the Constitution "a moderate one", limited to protecting individual rights. Madison was deeply read in the history of government and used a range of sources in composing the amendments. The English Magna Carta of 1215 inspired the right to petition and to trial by jury, for example, while the English Bill of Rights of 1689 provided an early precedent for the right to keep and bear arms (although this applied only to Protestants) and prohibited cruel and unusual punishment. The greatest influence on Madison's text, however, was existing state constitutions.Madison introduced "amendments culled mainly from state constitutions and state ratifying convention proposals, especially Virginia's." Levy, p. 35 Many of his amendments, including his proposed new preamble, were based on theVirginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted in 1776 to proclaim the inherent rights of men, including the right to reform or abolish "inadequate" government. It influenced a number of later documents, including the United States Declaratio ...

drafted by Anti-Federalist George Mason in 1776. To reduce future opposition to ratification, Madison also looked for recommendations shared by many states. He did provide one, however, that no state had requested: "No state shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases." He did not include an amendment that every state had asked for, one that would have made tax assessments voluntary instead of contributions. Madison proposed the following constitutional amendments:

Crafting amendments

Federalist representatives were quick to attack Madison's proposal, fearing that any move to amend the new Constitution so soon after its implementation would create an appearance of instability in the government. The House, unlike the Senate, was open to the public, and members such asFisher Ames

Fisher Ames (; April 9, 1758 – July 4, 1808) was a Representative in the United States Congress from the 1st Congressional District of Massachusetts. He was an important leader of the Federalist Party in the House, and was noted for his ...

warned that a prolonged "dissection of the constitution" before the galleries could shake public confidence. A procedural battle followed, and after initially forwarding the amendments to a select committee for revision, the House agreed to take Madison's proposal up as a full body beginning on July 21, 1789.

The eleven-member committee made some significant changes to Madison's nine proposed amendments, including eliminating most of his preamble and adding the phrase "freedom of speech, and of the press". The House debated the amendments for eleven days. Roger Sherman of Connecticut persuaded the House to place the amendments at the Constitution's end so that the document would "remain inviolate", rather than adding them throughout, as Madison had proposed. The amendments, revised and condensed from twenty to seventeen, were approved and forwarded to the Senate on August 24, 1789.

The Senate edited these amendments still further, making 26 changes of its own. Madison's proposal to apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government was eliminated, and the seventeen amendments were condensed to twelve, which were approved on September 9, 1789. The Senate also eliminated the last of Madison's proposed changes to the preamble.

On September 21, 1789, a House–Senate Conference Committee convened to resolve the numerous differences between the two Bill of Rights proposals. On September 24, 1789, the committee issued this report, which finalized 12 Constitutional Amendments for House and Senate to consider. This final version was approved by joint resolution of Congress on September 25, 1789, to be forwarded to the states on September 28.

By the time the debates and legislative maneuvering that went into crafting the Bill of Rights amendments was done, many personal opinions had shifted. A number of Federalists came out in support, thus silencing the Anti-Federalists' most effective critique. Many Anti-Federalists, in contrast, were now opposed, realizing that Congressional approval of these amendments would greatly lessen the chances of a second constitutional convention. Anti-Federalists such as Richard Henry Lee also argued that the Bill left the most objectionable portions of the Constitution, such as the federal judiciary and direct taxation, intact.

Madison remained active in the progress of the amendments throughout the legislative process. Historian Gordon S. Wood

Gordon Stewart Wood (born November 27, 1933) is an American historian and professor at Brown University. He is a recipient of the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for History for '' The Radicalism of the American Revolution'' (1992). His book ''The Creation o ...

writes that "there is no question that it was Madison's personal prestige and his dogged persistence that saw the amendments through the Congress. There might have been a federal Constitution without Madison but certainly no Bill of Rights."

Ratification process

The twelve articles of amendment approved by congress were officially submitted to the Legislatures of the several States for consideration on September 28, 1789. The following statesratified

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inten ...

some or all of the amendments:

# New Jersey: Articles One and Three through Twelve on November 20, 1789, and Article Two on May 7, 1992

# Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

: Articles One through Twelve on December 19, 1789

# North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

: Articles One through Twelve on December 22, 1789

# South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

: Articles One through Twelve on January 19, 1790

# New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

: Articles One and Three through Twelve on January 25, 1790, and Article Two on March 7, 1985

# Delaware: Articles Two through Twelve on January 28, 1790

# New York: Articles One and Three through Twelve on February 24, 1790

# Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

: Articles Three through Twelve on March 10, 1790, and Article One on September 21, 1791

# Rhode Island: Articles One and Three through Twelve on June 7, 1790, and Article Two on June 10, 1993

# Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

: Articles One through Twelve on November 3, 1791

# Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

: Article One on November 3, 1791, and Articles Two through Twelve on December 15, 1791(After failing to ratify the 12 amendments during the 1789 legislative session.) Having been approved by the requisite three-fourths of the several states, there being 14 States in the Union at the time (as Vermont had been admitted into the Union on March 4, 1791), the ratification of Articles Three through Twelve was completed and they became Amendments 1 through 10 of the Constitution. Congress, now meeting at

Congress Hall

Congress Hall, located in Philadelphia at the intersection of Chestnut and 6th Streets, served as the seat of the United States Congress from December 6, 1790, to May 14, 1800. During Congress Hall's duration as the capitol of the United State ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, was informed of this by President Washington on January 18, 1792.

As they had not yet been approved by 11 of the 14 states, the ratification of Article One (ratified by 10) and Article Two (ratified by 6) remained incomplete. The ratification plateau they needed to reach soon rose to 12 of 15 states when Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

joined the Union (June 1, 1792). On June 27, 1792, the Kentucky General Assembly ratified all 12 amendments, however this action did not come to light until 1996.

Article One came within one state of the number needed to become adopted into the Constitution on two occasions between 1789 and 1803. Despite coming close to ratification early on, it has never received the approval of enough states to become part of the Constitution. As Congress did not attach a ratification time limit to the article, it is still pending before the states. Since no state has approved it since 1792, ratification by an additional 27 states would now be necessary for the article to be adopted.

Article Two, initially ratified by seven states through 1792 (including Kentucky), was not ratified by another state for eighty years. The Ohio General Assembly ratified it on May 6, 1873 in protest of an unpopular Congressional pay raise. A century later, on March 6, 1978, the Wyoming Legislature

The Wyoming State Legislature is the legislative branch of the U.S. State of Wyoming. It is a bicameral state legislature, consisting of a 60-member Wyoming House of Representatives, and a 30-member Wyoming Senate. The legislature meets at th ...

also ratified the article. Gregory Watson, a University of Texas at Austin undergraduate student, started a new push for the article's ratification with a letter-writing campaign to state legislatures. As a result, by May 1992, enough states had approved Article Two (38 of the 50 states in the Union) for it to become the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution. The amendment's adoption was certified by Archivist of the United States Don W. Wilson and subsequently affirmed by a vote of Congress on May 20, 1992.

Three states did not complete action on the twelve articles of amendment when they were initially put before the states. Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

found a Bill of Rights unnecessary and so refused to ratify. Both chambers of the Massachusetts General Court ratified a number of the amendments (the Senate adopted 10 of 12 and the House 9 of 12), but failed to reconcile their two lists or to send official notice to the Secretary of State of the ones they did agree upon. Both houses of the Connecticut General Assembly voted to ratify Articles Three through Twelve but failed to reconcile their bills after disagreeing over whether to ratify Articles One and Two. All three later ratified the Constitutional amendments originally known as Articles Three through Twelve as part of the 1939 commemoration of the Bill of Rights' sesquicentennial: Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

on March 2, Georgia on March 18, and Connecticut on April 19. Connecticut and Georgia would also later ratify Article Two, on May 13, 1987 and February 2, 1988 respectively.

Application and text

The Bill of Rights had little judicial impact for the first 150 years of its existence; in the words ofGordon S. Wood

Gordon Stewart Wood (born November 27, 1933) is an American historian and professor at Brown University. He is a recipient of the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for History for '' The Radicalism of the American Revolution'' (1992). His book ''The Creation o ...

, "After ratification, most Americans promptly forgot about the first ten amendments to the Constitution." The Court made no important decisions protecting free speech rights, for example, until 1931. Historian Richard Labunski attributes the Bill's long legal dormancy to three factors: first, it took time for a "culture of tolerance" to develop that would support the Bill's provisions with judicial and popular will; second, the Supreme Court spent much of the 19th century focused on issues relating to intergovernmental balances of power; and third, the Bill initially only applied to the federal government, a restriction affirmed by '' Barron v. Baltimore'' (1833). In the 20th century, however, most of the Bill's provisions were applied to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment—a process known as incorporation—beginning with the freedom of speech clause, in ''Gitlow v. New York

''Gitlow v. New York'', 268 U.S. 652 (1925), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court holding that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution had extended the First Amendment's provisions protecting freedom of spe ...

'' (1925). In '' Talton v. Mayes'' (1896), the Court ruled that constitutional protections, including the provisions of the Bill of Rights, do not apply to the actions of American Indian tribal governments. Through the incorporation process the Supreme Court succeeded in extending to the states almost all of the protections in the Bill of Rights, as well as other, unenumerated rights. The Bill of Rights thus imposes legal limits on the powers of governments and acts as an anti-majoritarian/minoritarian safeguard by providing deeply entrenched legal protection for various civil liberties and fundamental rights. The Supreme Court for example concluded in the '' West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette'' (1943) case that the founders intended the Bill of Rights to put some rights out of reach from majorities, ensuring that some liberties would endure beyond political majorities. As the Court noted, the idea of the Bill of Rights "was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts." This is why "fundamental rights may not be submitted to a vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections."'' Obergefell v. Hodges'', No. 14-556slip op.

at 24 (U.S. June 26, 2015).

First Amendment

The First Amendment prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering with the right to peaceably assemble or prohibiting the petitioning for a governmental redress of grievances. Initially, the First Amendment applied only to laws enacted by Congress, and many of its provisions were interpreted more narrowly than they are today. In '' Everson v. Board of Education'' (1947), the Court drew on Thomas Jefferson's correspondence to call for "a wall of separation between church and State", though the precise boundary of this separation remains in dispute. Speech rights were expanded significantly in a series of 20th- and 21st-century court decisions that protected various forms of political speech, anonymous speech, campaign financing, pornography, and school speech; these rulings also defined a series of exceptions to First Amendment protections. The Supreme Court overturnedEnglish common law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

precedent to increase the burden of proof for libel suits, most notably in '' New York Times Co. v. Sullivan'' (1964). Commercial speech is less protected by the First Amendment than political speech, and is therefore subject to greater regulation.

The Free Press Clause protects publication of information and opinions, and applies to a wide variety of media. In '' Near v. Minnesota'' (1931) and '' New York Times v. United States'' (1971), the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protected against prior restraint

Prior restraint (also referred to as prior censorship or pre-publication censorship) is censorship imposed, usually by a government or institution, on expression, that prohibits particular instances of expression. It is in contrast to censorship ...

—pre-publication censorship—in almost all cases. The Petition Clause protects the right to petition all branches and agencies of government for action. In addition to the right of assembly guaranteed by this clause, the Court has also ruled that the amendment implicitly protects freedom of association.

Second Amendment

The Second Amendment protects the individual right to keep and bear arms. The concept of such a right existed within Englishcommon law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

long before the enactment of the Bill of Rights. First codified in the English Bill of Rights of 1689 (but there only applying to Protestants), this right was enshrined in fundamental laws of several American states during the Revolutionary era, including the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted in 1776 to proclaim the inherent rights of men, including the right to reform or abolish "inadequate" government. It influenced a number of later documents, including the United States Declaratio ...

and the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776. Long a controversial issue

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opposite d ...

in American political, legal, and social discourse, the Second Amendment has been at the heart of several Supreme Court decisions.

* In '' United States v. Cruikshank'' (1876), the Court ruled that " e right to bear arms is not granted by the Constitution; neither is it in any manner dependent upon that instrument for its existence. The Second Amendment means no more than that it shall not be infringed by Congress, and has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the National Government."

* In '' United States v. Miller'' (1939), the Court ruled that the amendment " rotects arms that had areasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia".

* In '' District of Columbia v. Heller'' (2008), the Court ruled that the Second Amendment "codified a pre-existing right" and that it "protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia, and to use that arm for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home" but also stated that "the right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose".

* In '' McDonald v. Chicago'' (2010), the Court ruled that the Second Amendment limits state and local governments to the same extent that it limits the federal government.

Third Amendment

The Third Amendment restricts the quartering of soldiers in private homes, in response to Quartering Acts passed by the British parliament during the Revolutionary War. The amendment is one of the least controversial of the Constitution, and, , has never been the primary basis of a Supreme Court decision.Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment guards against unreasonable searches and seizures, along with requiring any warrant to be judicially sanctioned and supported byprobable cause

In United States criminal law, probable cause is the standard by which police authorities have reason to obtain a warrant for the arrest of a suspected criminal or the issuing of a search warrant. There is no universally accepted definition o ...

. It was adopted as a response to the abuse of the writ of assistance, which is a type of general search warrant

A search warrant is a court order that a magistrate or judge issues to authorize law enforcement officers to conduct a search of a person, location, or vehicle for evidence of a crime and to confiscate any evidence they find. In most countries, ...

, in the American Revolution. Search and seizure (including arrest) must be limited in scope according to specific information supplied to the issuing court, usually by a law enforcement officer who has sworn by it. The amendment is the basis for the exclusionary rule

In the United States, the exclusionary rule is a legal rule, based on constitutional law, that prevents evidence collected or analyzed in violation of the defendant's constitutional rights from being used in a court of law. This may be consider ...

, which mandates that evidence obtained illegally cannot be introduced into a criminal trial. The amendment's interpretation has varied over time; its protections expanded under left-leaning courts such as that headed by Earl Warren and contracted under right-leaning courts such as that of William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

.

Fifth Amendment

The Fifth Amendment protects againstdouble jeopardy

In jurisprudence, double jeopardy is a procedural defence (primarily in common law jurisdictions) that prevents an accused person from being tried again on the same (or similar) charges following an acquittal or conviction and in rare case ...

and self-incrimination and guarantees the rights to due process, grand jury screening of criminal indictments, and compensation for the seizure of private property under eminent domain. The amendment was the basis for the court's decision in '' Miranda v. Arizona'' (1966), which established that defendants must be informed of their rights to an attorney and against self-incrimination prior to interrogation by police.

Sixth Amendment

The Sixth Amendment establishes a number of rights of the defendant in a criminal trial: * to aspeedy

Speedy refers to something or someone moving at high speed.

Speedy may refer to:

Ships

* HMS ''Speedy'', nine ships of the Royal Navy

* ''Speedy''-class brig, a class of naval ship

* ''Speedy'' (1779), a whaler and convict ship despatched i ...

and public trial

* to trial by an impartial jury

* to be informed of criminal charges

* to confront witnesses

* to compel witnesses to appear in court

* to assistance of counsel

In '' Gideon v. Wainwright'' (1963), the Court ruled that the amendment guaranteed the right to legal representation in all felony prosecutions in both state and federal courts.

Seventh Amendment

The Seventh Amendment guarantees jury trials in federal civil cases that deal with claims of more than twenty dollars. It also prohibits judges from overruling findings of fact by juries in federal civil trials. In '' Colgrove v. Battin'' (1973), the Court ruled that the amendment's requirements could be fulfilled by a jury with a minimum of six members. The Seventh is one of the few parts of the Bill of Rights not to be incorporated (applied to the states).Eighth Amendment

The Eighth Amendment forbids the imposition of excessive bails or fines, though it leaves the term "excessive" open to interpretation. The most frequently litigated clause of the amendment is the last, which forbids cruel and unusual punishment. This clause was only occasionally applied by the Supreme Court prior to the 1970s, generally in cases dealing with means of execution. In '' Furman v. Georgia'' (1972), some members of the Court found capital punishment itself in violation of the amendment, arguing that the clause could reflect "evolving standards of decency" as public opinion changed; others found certain practices in capital trials to be unacceptably arbitrary, resulting in a majority decision that effectively halted executions in the United States for several years. Executions resumed following '' Gregg v. Georgia'' (1976), which found capital punishment to be constitutional if the jury was directed by concrete sentencing guidelines. The Court has also found that some poor prison conditions constitute cruel and unusual punishment, as in ''Estelle v. Gamble __NOTOC__

''Estelle v. Gamble'', 429 U.S. 97 (1976), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States established the standard of what a prisoner must plead in order to claim a violation of Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitut ...

'' (1976) and '' Brown v. Plata'' (2011).

Ninth Amendment

The Ninth Amendment declares that there are additional fundamental rights that exist outside the Constitution. The rights enumerated in the Constitution are not an explicit and exhaustive list of individual rights. It was rarely mentioned in Supreme Court decisions before the second half of the 20th century, when it was cited by several of the justices in ''Griswold v. Connecticut

''Griswold v. Connecticut'', 381 U.S. 479 (1965), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protects the liberty of married couples to buy and use contraceptives withou ...

'' (1965). The Court in that case voided a statute prohibiting use of contraceptives as an infringement of the right of marital privacy. This right was, in turn, the foundation upon which the Supreme Court built decisions in several landmark cases, including, '' Roe v. Wade'' (1973), which overturned a Texas law making it a crime to assist a woman to get an abortion, and '' Planned Parenthood v. Casey'' (1992), which invalidated a Pennsylvania law that required spousal awareness prior to obtaining an abortion.

Tenth Amendment

The Tenth Amendment reinforces the principles ofseparation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

and federalism by providing that powers not granted to the federal government by the Constitution, nor prohibited to the states, are reserved to the states or the people. The amendment provides no new powers or rights to the states, but rather preserves their authority in all matters not specifically granted to the federal government nor explicitly forbidden to the states.

Display and honoring of the Bill of Rights

George Washington had fourteen handwritten copies of the Bill of Rights made, one for Congress and one for each of the original thirteen states. The copies for Georgia, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania went missing. The New York copy is thought to have been destroyed in a fire. Two unidentified copies of the missing four (thought to be the Georgia and Maryland copies) survive; one is in the National Archives, and the other is in the New York Public Library. North Carolina's copy was stolen from the State Capitol by a Union soldier following the Civil War. In an FBI sting operation, it was recovered in 2003. The copy retained by the First Congress has been on display (along with the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence) in the ''Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom'' room at theNational Archives Building

The National Archives Building, known informally as Archives I, is the headquarters of the United States National Archives and Records Administration. It is located north of the National Mall at 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, Northwest, Washington, ...

in Washington, D.C. since December 13, 1952.

After fifty years on display, signs of deterioration in the casing were noted, while the documents themselves appeared to be well preserved. Accordingly, the casing was updated and the Rotunda rededicated on September 17, 2003. In his dedicatory remarks, President George W. Bush stated, "The true mericanrevolution was not to defy one earthly power, but to declare principles that stand above every earthly power—the equality of each person before God, and the responsibility of government to secure the rights of all."

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

declared December 15 to be Bill of Rights Day, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights. In 1991, the Virginia copy of the Bill of Rights toured the country in honor of its bicentennial, visiting the capitals of all fifty states.

See also

*Anti-Federalism

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Conf ...

* Constitutionalism in the United States

* Founding Fathers of the United States

* Four Freedoms

The Four Freedoms were goals articulated by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Monday, January 6, 1941. In an address known as the Four Freedoms speech (technically the 1941 State of the Union address), he proposed four fundamental freed ...

* Institute of Bill of Rights Law

* Patients' ill ofrights

* Second Bill of Rights

* States' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

* Substantive due process

Substantive due process is a principle in United States constitutional law that allows courts to establish and protect certain fundamental rights from government interference, even if only procedural protections are present or the rights are unen ...

* Taxpayer Bill of Rights

* Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom was drafted in 1777 by Thomas Jefferson in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and introduced into the Virginia General Assembly in Richmond in 1779. On January 16, 1786, the Assembly enacted the statute into the s ...

* '' We Hold These Truths''

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * Bordewich, Fergus M. ''The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government'' (2016) on 1789–1791. * Brant, Irving. ''The Bill of rights; its origin and meaning'' (1965online

* Cogan, Neil H. (2015). ''The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins.'' Second edition. New York: Oxford University Press. * * * * Stevens, John Paul. "Keynote Address: The Bill of Rights: A Century of Progress." ''University of Chicago Law Review'' 59 (1992): 13

online

.

External links

* National Archives* Footnote.com (partners with the National Archives)

Online viewer with High-resolution image of the original document

* Library of Congress

on opposition to the Bill of Rights * TeachingAmericanHistory.org �

Bill of Rights

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Bill Of Rights, United States 1st United States Congress 1791 in American politics 1791 in American law Amendments to the United States Constitution American Enlightenment George Mason James Madison United States Bill of Rights Government documents of the United States Presidency of George Washington Constitution of the United States