Election of 1868

Grant's rise in political popularity among Republicans was based on his successful generalship that defeated

Grant's rise in political popularity among Republicans was based on his successful generalship that defeated First term (1869–1873)

Inaugural address 1869

Grant's March 4, 1869, inaugural speech addressed four priorities. First, Grant stated he would approach

Grant's March 4, 1869, inaugural speech addressed four priorities. First, Grant stated he would approach Cabinet

Grant's cabinet choices surprised the nation. Although Grant respectfully listened to political advice, he independently bypassed traditional consultations with prominent Republicans and kept his cabinet selections secret. Grant's initial cabinet nominations were met with both criticism and approval. Grant appointed Elihu B. Washburne, Secretary of State, out of a friendship courtesy. Washburne served eleven days of office and then resigned. A week later, Grant appointed Washburne Minister to France. Grant appointed the conservativeTenure of Office Act modified

In March 1869, President Grant made it known he desired the Tenure of Office Act (1867) repealed, stating it was a "stride toward a revolution in our free system". The law prevented the president from removing executive officers without Senate approval. Grant believed it was a major curtailment to presidential power. To bolster the repeal effort, Grant declined to make any new appointments except for vacancies, until the law was overturned. On March 9, 1869, the House repealed the law outright, but the Senate Judiciary Committee rejected the bill and only offered Grant a temporary suspension of the law. When Grant objected, the Senate Republican caucus met and proposed allowing the president to have a free hand in choosing and removing his cabinet. The Senate Judiciary Committee wrote the new bill. A muddled compromise was reached by the House and Senate. Grant signed the bill into law on April 5, having gotten virtually everything he wanted.Reconstruction

Fifteenth Amendment

Grant worked to ensureDepartment of Justice

On June 22, 1870, Grant signed a bill into law passed by Congress that created the Department of Justice and to aid the Attorney General, the Office ofNaturalization Act of 1870

On July 14, 1870, Grant signed into law theForce Acts of 1870 and 1871

To add enforcement to the 15th Amendment, Congress passed an act that guaranteed the protection of voting rights of African Americans; Grant signed the bill, known as the Force Act of 1870 into law on May 31, 1870. This law was designed to keep theAmnesty Act of 1872

Financial policy

Public Credit Act

On taking office Grant's first move was signing the Act to Strengthen the Public Credit, which the Republican Congress had just passed. It ensured that all public debts, particularly war bonds, would be paid only in gold rather than in greenbacks. The price of gold on the New York exchange fell to $130 per ounce – the lowest point since the suspension of specie payment in 1862.Federal wages raised

On May 19, 1869, Grant protected the wages of those working for the U.S. Government. In 1868, a law was passed that reduced the government working day to 8 hours; however, much of the law was later repealed allowing day wages to also be reduced. To protect workers Grant signed an executive order that "no reduction shall be made in the wages" regardless of the reduction in hours for the government day workers.Boutwell reforms

Treasury SecretaryGold corner conspiracy

The New York gold conspiracy almost dismantled Grant's presidency. In September 1869, financial manipulatorsForeign policy

Grant was a man of peace, and almost wholly devoted to domestic affairs. There were no foreign-policy disasters, and no wars to engage in. Besides Grant himself, the main players in foreign affairs were the Secretary of State The foreign policy of the Administration was generally successful, except for the attempt to annex Santo Domingo. The annexation of Santo Domingo was Grant's effort to create a haven for blacks in the South and was a first step to end slavery in Cuba and Brazil. The dangers of a confrontation with Britain on the ''Alabama'' question were resolved peacefully, and to the monetary advantage of the United States. Issues regarding the Canadian boundary were easily settled. The achievements were the work of Secretary Hamilton Fish, who was a spokesman for caution and stability. A poll of historians has stated that Secretary Fish was one of the greatest Secretaries of States in United States history.''American Heritage'' (December 1981), ''The Ten Best Secretaries Of States'', volume 33, issue 1, Fish served as Secretary of State for nearly the entire two terms. Historians emphasize his judiciousness and efforts towards reform and diplomatic moderation.American Heritage Editors (December, 1981), ''The Ten Best Secretaries Of State...''. Fish kept the United States out of war with Spain over

The foreign policy of the Administration was generally successful, except for the attempt to annex Santo Domingo. The annexation of Santo Domingo was Grant's effort to create a haven for blacks in the South and was a first step to end slavery in Cuba and Brazil. The dangers of a confrontation with Britain on the ''Alabama'' question were resolved peacefully, and to the monetary advantage of the United States. Issues regarding the Canadian boundary were easily settled. The achievements were the work of Secretary Hamilton Fish, who was a spokesman for caution and stability. A poll of historians has stated that Secretary Fish was one of the greatest Secretaries of States in United States history.''American Heritage'' (December 1981), ''The Ten Best Secretaries Of States'', volume 33, issue 1, Fish served as Secretary of State for nearly the entire two terms. Historians emphasize his judiciousness and efforts towards reform and diplomatic moderation.American Heritage Editors (December, 1981), ''The Ten Best Secretaries Of State...''. Fish kept the United States out of war with Spain over Failed annexation of Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic)

Grant gave a high priority to protecting and improving the status of Blacks in the United States and tried to annex the Caribbean country of the Dominican Republic as a safety valve for them. Senator Charles Sumner was even more firmly devoted to Black interests and opposed Grant's scheme. Sumner stopped the plan and Grant retaliated by destroying Sumner's power. In 1869, Grant proposed to annex the independent Spanish-speaking black nation of the

Grant gave a high priority to protecting and improving the status of Blacks in the United States and tried to annex the Caribbean country of the Dominican Republic as a safety valve for them. Senator Charles Sumner was even more firmly devoted to Black interests and opposed Grant's scheme. Sumner stopped the plan and Grant retaliated by destroying Sumner's power. In 1869, Grant proposed to annex the independent Spanish-speaking black nation of the Cuban insurrection

The Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the Ten Years' War, gained wide sympathy in the U.S. Juntas based in New York raised money, and smuggled men and munitions to Cuba, while energetically spreading propaganda in American newspapers. The Grant administration turned a blind eye to this violation of American neutrality. In 1869, Grant was urged by popular opinion to support rebels in Cuba with military assistance and to give them U.S. diplomatic recognition. Fish, however, wanted stability and favored the Spanish government, without publicly challenging the popular anti-Spanish American viewpoint. They reassured European governments that the U.S. did not want to annex Cuba. Grant and Fish gave lip service to Cuban independence, called for an end to slavery in Cuba, and quietly opposed American military intervention. Fish worked diligently against popular pressure, and was able to keep Grant from officially recognizing Cuban independence because it would have endangered negotiations with Britain over the ''Alabama'' Claims.Treaty of Washington

Historians have credited the Treaty of Washington for implementing The Tribunal met on neutral territory in Geneva, Switzerland. The panel of five international arbitrators included Charles Francis Adams, Sr., Charles Francis Adams, who was counseled by William M. Evarts, Caleb Cushing, and Morrison R. Waite. On August 25, 1872, the Tribunal awarded the United States $15.5 million in gold; $1.9 million was awarded to Great Britain. Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration "bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy". In addition to the $15.5 million arbitration award, the treaty resolved some disputes over borders and fishing rights. On October 21, 1872, William I, Emperor of Germany, settled a boundary dispute in favor of the United States.

The Tribunal met on neutral territory in Geneva, Switzerland. The panel of five international arbitrators included Charles Francis Adams, Sr., Charles Francis Adams, who was counseled by William M. Evarts, Caleb Cushing, and Morrison R. Waite. On August 25, 1872, the Tribunal awarded the United States $15.5 million in gold; $1.9 million was awarded to Great Britain. Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration "bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy". In addition to the $15.5 million arbitration award, the treaty resolved some disputes over borders and fishing rights. On October 21, 1872, William I, Emperor of Germany, settled a boundary dispute in favor of the United States.

Korea

In 1871, the Grant administration sought to open Korea and the United States in a trade agreement. In May 1871, the U.S. Minister to China ordered a squadron of Navy ships to Seoul to pressure the Korean government to sign a trade treaty with the United States, similar to opening up trade with Japan in 1854, by Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, Matthew Perry. The Koreans resisted and sent a fleet of ships to block the entrance of the Han River to prevent the U.S. Navy from reaching Seoul. On May 30, 1871, Rear Admiral John Rodgers (American Civil War naval officer), John Rodgers with a fleet of five ships, part of the Asiatic Squadron, arrived at the mouth of the Salee River below Seoul. The Koreans fired on the U.S. ships with little damage done. Rogers demanded an apology from the Koreans and open trade negotiations, but the Koreans refused to comply. On June 10, Rogers attacked and destroyed several Korean forts. This attack was called the Battle of Ganghwa, which resulted in 250 Koreans and three Americans killed. The Koreans still refused to negotiate, and the American fleet sailed away. The Koreans refer to this 1871 U.S. military action as Shinmiyangyo. Grant defended Rogers in his third annual message to Congress in December 1871.Native American policy

After the very bloody frontier wars in the 1860s, Grant sought to build a "peace policy" toward the tribes. He emphasized appointees who wanted peace and were favorable toward religious groups. In the end, however, the western warfare grew worse.

Grant declared in his 1869 Inaugural Address that he favored "any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship." In a bold step, Grant appointed his aide General Ely S. Parker, ''Donehogawa'' (a Seneca people, Seneca), the first Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Parker met some opposition in the Senate until Attorney General Hoar said Parker was legally able to hold the office. The Senate confirmed Parker by a vote of 36 to 12. During Parker's tenure Native wars dropped from 101 in 1869 to 58 in 1870.

After the very bloody frontier wars in the 1860s, Grant sought to build a "peace policy" toward the tribes. He emphasized appointees who wanted peace and were favorable toward religious groups. In the end, however, the western warfare grew worse.

Grant declared in his 1869 Inaugural Address that he favored "any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship." In a bold step, Grant appointed his aide General Ely S. Parker, ''Donehogawa'' (a Seneca people, Seneca), the first Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Parker met some opposition in the Senate until Attorney General Hoar said Parker was legally able to hold the office. The Senate confirmed Parker by a vote of 36 to 12. During Parker's tenure Native wars dropped from 101 in 1869 to 58 in 1870.

Board of Indian Commissioners

Early on Grant met with tribal chiefs of the Choctaw, Creek, Cherokee, and Chickasaw nations who expressed interest to teach "wild" Natives outside their own settled districts farming skills. Grant told the Native chiefs that American settlement would lead to inevitable conflict, but that the "march to civilization" would lead to pacification. On April 10, 1869, Congress created the Board of Indian Commissioners. Grant appointed volunteer members who were "eminent for their intelligence and philanthropy." The Grant Board was given extensive joint power with Grant, Secretary of Interior Cox, and the Interior Department to supervise the Bureau of Indian Affairs and "civilize" Native Americans. No Natives were appointed to the committee, only European Americans. The commission monitored purchases and began to inspect Native agencies. It attributed much of the trouble in Native country to the encroachment of whites. The board approved of the destruction of Native culture. The Natives were to be instructed in Christianity, agriculture, representative government, and assimilated on reservations.Marias Massacre

On January 23, 1870, the ''Peace Policy'' was tested when Major Edward M. Baker senselessly slaughtered 173 Piegan Indians, mostly women, and children, in the Marias Massacre. Public outcry increased when General Sheridan defended Baker's actions. On July 15, 1870, Grant signed Congressional legislation that barred military officers from holding either elected or appointed office or suffering dismissal from the Army. In December 1870, Grant submitted to Congress the names of the new appointees, most of whom were confirmed by the Senate.Red Cloud White House visit

Grant's ''Peace'' policy received a boost when the Chief of the Oglala Sioux Red Cloud, ''Maȟpíya Lúta'', and Brulé Sioux Spotted Tail, ''Siŋté Glešká'', arrived in Washington, D.C., and met Grant at the White House for a bountiful state dinner on May 7, 1870. Red Cloud, at a previous meeting with Secretary Cox and Commissioner Parker, complained that promised rations and arms for hunting had not been delivered. Afterward, Grant and Cox lobbied Congress for the promised supplies and rations. Congress responded and on July 15, 1870, Grant signed the Indian Appropriations Act into law that appropriated the tribal monies. Two days after Spotted Tail urged the Grant administration to keep white settlers from invading Native reservation land, Grant ordered all Generals in the West to "keep intruders off by military force if necessary". In 1871, Grant signed another Indian Appropriations Act that ended the governmental policy of treating tribes as independent sovereign nations. Natives would be treated as individuals or wards of the state and Indian policies would be legislated by Congressional statutes.Peace policy

At the core of the ''Peace Policy'' was placing the western reservations under the control of religious denominations. In 1872, the implementation of the policy involved the allotting of Indian reservations to religious organizations as exclusive religious domains. Of the 73 agencies assigned, the Methodists received fourteen; the Orthodox Quakers, Friends ten; the Presbyterians nine; the Episcopal Church (United States), Episcopalians eight; the Roman Catholics seven; the Hicksite Quakers, Friends six; the Baptists five; the Dutch Reformed five; the Congregationalists three; Christians two; Unitarianism, Unitarians two; American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions one; and Lutheranism, Lutherans one. Infighting between competitive missionary groups over the distribution of agencies was detrimental to Grant's ''Peace'' Policy. The selection criteria were vague, and some critics saw the Peace Policy as violating Native American freedom of religion. In another setback, William Welsh, a prominent merchant, prosecuted the Bureau in a Congressional investigation over malfeasance. Although Parker was exonerated, legislation passed in Congress that authorized the board to approve goods and services payments by vouchers from the Bureau. Parker resigned from office, and Grant replaced Parker with reformer Francis A. Walker.Domestic policy

Holidays law

On June 28, 1870, Grant approved and signed legislation that made Christmas, on December 25, a legal federal public holiday in the national capital of Washington, D.C. According to historian Ron White, Grant did this because of his passion to unify the nation. During the early 19th Century in the United States, Christmas became more of a family-centered activity. Other Holidays, included in the law within Washington, D.C., were New Year, Fourth of July, and Thanksgiving (United States), Thanksgiving. The law affected 5,300 federal employees working in the District of Columbia, the nation's capital. The legislation was meant to adapt to similar laws in states surrounding Washington, D.C., and "in every State of the Union."Utah territory polygamy

In 1862, during the American Civil War President Lincoln signed into law the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, Morrill bill that outlawed polygamy in all U.S. Territories. Mormons who practiced polygamy in Utah, for the most part, resisted the Morrill law and the territorial governor. During the 1868 election, Grant had mentioned he would enforce the law against polygamy. Tensions began as early as 1870, when Mormons in Ogden, Utah began to arm themselves and practice military drilling. By the Fourth of July, 1871 Mormon militia in Salt Lake City, Utah were on the verge of fighting territorial troops; in the end, violence was averted. Grant, however, who believed Utah was in a state of rebellion was determined to arrest those who practiced polygamy outlawed under the Morrill Act. In October 1871 hundreds of Mormons were rounded up by U.S. marshals, put in a prison camp, arrested, and put on trial for polygamy. One convicted polygamist received a $500 fine and three years in prison under hard labor. On November 20, 1871, Mormon leader Brigham Young, in ill health, had been charged with polygamy. Young's attorney stated that Young had no intention to flee the court. Other persons during the polygamy shutdown were charged with murder or intent to kill. The Morrill Act, however, proved hard to enforce since proof of marriage was required for conviction. Grant personally found polygamy morally offensive. On December 4, 1871, Grant said polygamists in Utah were "a remnant of barbarism, repugnant to civilization, to decency, and to the laws of the United States."Comstock Act

In March 1873, anti-obscenity moralists, led by Anthony Comstock, secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, easily secured passage of the Comstock Act which made it a federal crime to mail articles "for any indecent or immoral use". Grant signed the bill after he was assured that Comstock would personally enforce it. Comstock went on to become a special agent of the Post Office appointed by Secretary James Cresswell. Comstock prosecuted pornographers, imprisoned abortionists, banned nude art, stopped the mailing of information about contraception, and tried to ban what he considered bad books.Early suffrage movement

During Grant's presidency, the early Women's suffrage in the United States, Women's suffrage movement led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton gained national attention. Anthony lobbied for female suffrage, equal gender pay, and protection of property for women who resided in Washington, D.C. In April 1869, Grant signed into law the protection of married women's property from their husbands' debts and the ability for women to sue in court in Washington, D.C. In March 1870 Representative Samuel M. Arnell introduced a bill, coauthored by suffragist Belva Ann Lockwood, Bennette Lockwood, that would give women federal workers equal pay for equal work. Two years later Grant signed a modified Senate version of the Arnell Bill into law. The law required that all federal female clerks would be paid the fully compensated salary; however, lower tiered female clerks were exempted. The law increased women's clerk salaries from 4% to 20% during the 1870s; however, the culture of patronage and patriarchy continued. To placate the burgeoning Women's suffrage in the United States, suffragist movement, the Republicans' platform included that women's rights should be treated with "respectful consideration", while Grant advocated equal rights for all citizens.Yellowstone created

On March 1, 1872, Grant played his role, in signing the "Act of Dedication" into law, that established the Yellowstone region as the nation's first national park, made possible by three years of exploration by Cook-Folsom-Peterson (1869), Washburn-Langford-Doane (1870), and Hayden (1871). The 1872 Yellowstone Act prohibited fish and game, including buffalo, from "wanton destruction" within the confines of the park. However, Congress did not appropriate funds or legislation for the enforcement against poaching; as a result, Secretary Delano could not hire people to aid tourists or protect Yellowstone from encroachment.Kennedy (2001),

On March 1, 1872, Grant played his role, in signing the "Act of Dedication" into law, that established the Yellowstone region as the nation's first national park, made possible by three years of exploration by Cook-Folsom-Peterson (1869), Washburn-Langford-Doane (1870), and Hayden (1871). The 1872 Yellowstone Act prohibited fish and game, including buffalo, from "wanton destruction" within the confines of the park. However, Congress did not appropriate funds or legislation for the enforcement against poaching; as a result, Secretary Delano could not hire people to aid tourists or protect Yellowstone from encroachment.Kennedy (2001),The Last Buffalo

Simon (2003) ''Papers of Ulysses S. Grant'', Volume 25, 1874, pp. 411–412 By the 1880s buffalo herds dwindled to only a few hundred, a majority found mostly in Yellowstone National Park. As the Indian wars ended, Congress appropriated money and enforcement legislation in 1894, signed into law by President Grover Cleveland, that protected and preserved buffalo and other wildlife in Yellowstone. Grant also signed legislation that protected northern fur seals on Alaska's Pribilof Islands. This was the first law in U.S. history that specifically protected wildlife on federally owned land.The Wilderness Society (February 16, 2015

Happy Presidents' Day: 12 of our greatest White House conservationists

Reforms and scandals

Civil service commission

The reform of the spoils system of political patronage entered the national agenda under the Grant presidency and would take on the fervor of a religious revival. The distribution of federal jobs by Congressional legislators was considered vital for their reelection to Congress. Grant required that all applicants to federal jobs apply directly to the Department heads, rather than the president. Two of Grant's appointments, Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox and Secretary of TreasuryNew York Custom House Ring

Prior to the presidential election of 1872 two congressional and one Treasury Department investigations took place over corruption at the New York Custom House under Grant collector appointments Moses H. Grinnell and Thomas Murphy. Private warehouses were taking imported goods from the docks and charging shippers storage fees. Grant's friend, George K. Leet, was allegedly involved with exorbitant pricing for storing goods and splitting the profits. Grant's third collector appointment, Chester A. Arthur, implemented Secretary of TreasuryStar Route Postal Ring

In the early 1870s during the Grant Administration, lucrative postal route contracts were given to local contractors on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast and Southern regions of the United States. These were known as Star routes, Star Routes because an asterisk was given on official United States Post Office Department, Post Office documents. These remote routes were hundreds of miles long and went to the most rural parts of the United States by horse and buggy. In obtaining these highly prized postal contracts, an intricate ring of bribery and straw bidding was set up in the Postal Contract office; the ring consisted of contractors, postal clerks, and various intermediary brokers. Straw bidding was at its highest practice while John Creswell, Grant's 1869 appointment, was United States Postmaster General, Postmaster-General. An 1872 federal investigation into the matter exonerated Creswell, but he was Censure in the United States, censured by the minority House report. A $40,000 bribe to the 42nd United States Congress, 42nd Congress by one postal contractor had tainted the results of the investigation. In 1876, another congressional investigation under a Democratic House shut down the postal ring for a few years.Salary law

On March 3, 1873, Grant signed a law that authorized the president's salary to be increased from $25,000 a year to $50,000 a year and Congressmen's salaries to be increased by $2,500. Representatives also received a retroactive pay bonus for the previous two years of service. This was done in secret and attached to a general appropriations bill. Reforming newspapers quickly exposed the law and the bonus was repealed in January 1874. Grant missed an opportunity to veto the bill and to make a strong statement for good government.Election of 1872

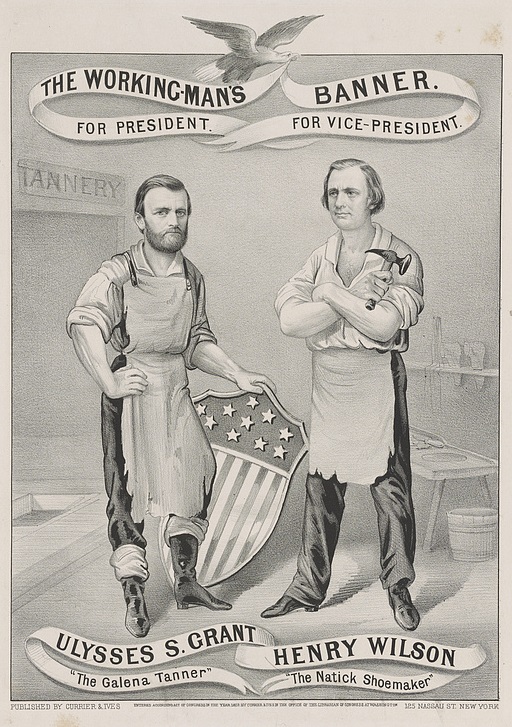

As his first term entered its final year, Grant remained popular throughout the nation despite the accusations of corruption that were swirling around his administration. When Republicans gathered for their 1872 Republican National Convention, 1872 national convention he was unanimously nominated for a second term. Henry Wilson was selected as his running mate over scandal-tainted Vice President Schuyler Colfax. The party platform advocated high tariffs and a continuation of Radical Reconstruction policies that supported five military districts in the Southern states.

During Grant's first term, a significant number of Republicans had become completely disillusioned with the party. Weary of the scandals and opposed to several of Grant's policies, split from the party to form the Liberal Republican Party (United States), Liberal Republican Party. At the party's only national convention, held in May 1872 ''

As his first term entered its final year, Grant remained popular throughout the nation despite the accusations of corruption that were swirling around his administration. When Republicans gathered for their 1872 Republican National Convention, 1872 national convention he was unanimously nominated for a second term. Henry Wilson was selected as his running mate over scandal-tainted Vice President Schuyler Colfax. The party platform advocated high tariffs and a continuation of Radical Reconstruction policies that supported five military districts in the Southern states.

During Grant's first term, a significant number of Republicans had become completely disillusioned with the party. Weary of the scandals and opposed to several of Grant's policies, split from the party to form the Liberal Republican Party (United States), Liberal Republican Party. At the party's only national convention, held in May 1872 ''Second term (1873–1877)

The Second inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant, second inauguration of Ulysses Grant's presidency was held on Tuesday, March 4, 1873, commencing the second four-year term of his presidency. Subsequently, the inaugural ball ended early when the food froze. Departing from the White House, a parade escorted Grant down the newly paved Pennsylvania Avenue, which was all decorated with banners and flags, on to the swearing-in ceremony in front of the Capitol building. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase administered the presidential oath of office. This was one of the coldest inaugurations in U.S. history, with the temperature at only 6 degrees at sunrise. After the swearing-in ceremony the inaugural parade commenced down Pennsylvania. The The Washington Star, ''Evening Star'' observed. "The private stands and windows along the entire route were crowded to excess." The parade consisted of a variety of military units along with marching bands, and civic organizations. The military units, in their fancy regalia, were the most noticeable. Altogether there were approximately 12,000 marchers who participated, including several units of African American soldiers. At the inaugural ball there were some 6,000 people in attendance. Great care was taken to ensure that Grant's inaugural ball would be in spacious quarters and would feature an elegant assortment of appetizers, food, and champagne. A large temporary wooden building was constructed at Judiciary Square to accommodate the event. Grant arrived around 11:30pm and the dancing began.

It was the only term of Henry Wilson as vice president. Wilson died 2 years, 263 days into this term, and the office remained vacant for the balance of it.

The Second inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant, second inauguration of Ulysses Grant's presidency was held on Tuesday, March 4, 1873, commencing the second four-year term of his presidency. Subsequently, the inaugural ball ended early when the food froze. Departing from the White House, a parade escorted Grant down the newly paved Pennsylvania Avenue, which was all decorated with banners and flags, on to the swearing-in ceremony in front of the Capitol building. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase administered the presidential oath of office. This was one of the coldest inaugurations in U.S. history, with the temperature at only 6 degrees at sunrise. After the swearing-in ceremony the inaugural parade commenced down Pennsylvania. The The Washington Star, ''Evening Star'' observed. "The private stands and windows along the entire route were crowded to excess." The parade consisted of a variety of military units along with marching bands, and civic organizations. The military units, in their fancy regalia, were the most noticeable. Altogether there were approximately 12,000 marchers who participated, including several units of African American soldiers. At the inaugural ball there were some 6,000 people in attendance. Great care was taken to ensure that Grant's inaugural ball would be in spacious quarters and would feature an elegant assortment of appetizers, food, and champagne. A large temporary wooden building was constructed at Judiciary Square to accommodate the event. Grant arrived around 11:30pm and the dancing began.

It was the only term of Henry Wilson as vice president. Wilson died 2 years, 263 days into this term, and the office remained vacant for the balance of it.

Reconstruction continued

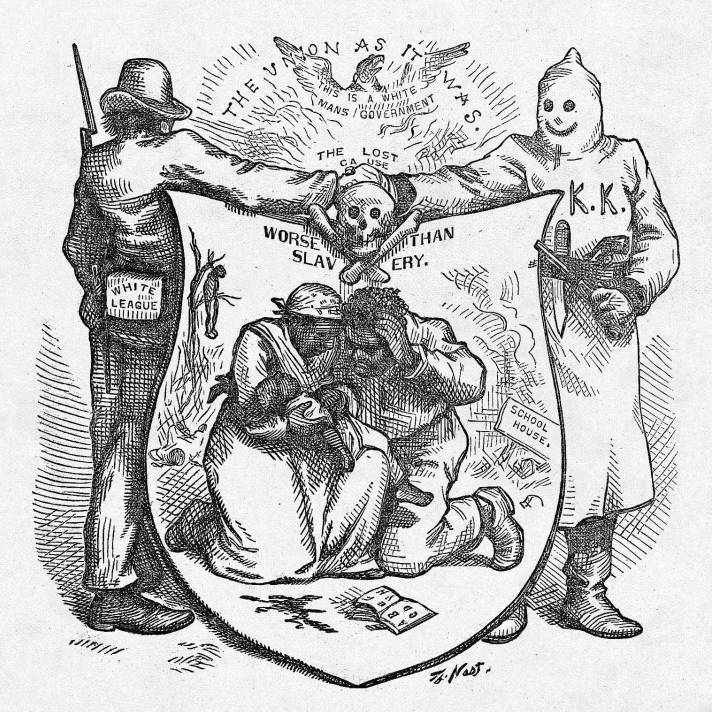

Grant was vigorous in his enforcement of the 14th and 15th amendments and prosecuted thousands of persons who violated African American civil rights; he used military force to put down political insurrections in Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. He proactively used military and United States Department of Justice, Justice Department enforcement of civil rights laws and the protection of African Americans more than any other 19th-century president. He used his full powers to weaken theColfax Massacre

After the November 4, 1872, election, Louisiana was a split state. In a controversial election, two candidates were claiming victory as governor. Violence was used to intimidate black Republicans. The fusionist party of Liberal Republicans and Democrats claimed John McEnery (Louisiana politician), John McEnery as the victor, while the Republicans claimed U.S. Senator William P. Kellogg. Two months later each candidate was sworn in as governor on January 13, 1873. A federal judge ruled that Kellogg was the rightful winner of the election and ordered him and the Republican-based majority to be seated. The White League supported McEnery and prepared to use military force to remove Kellogg from office. Grant ordered troops to enforce the court order and protect Kellogg. On March 4, Federal troops under a flag of truce and Kellogg's state militia defeated McEnery's fusionist party's insurrection. A dispute arose over who would be installed as judge and sheriff at the Colfax, Louisiana, Colfax courthouse in Grant Parish, Louisiana, Grant Parish. Kellogg's two appointees had seized control of the Court House on March 25 with the aid and protection of black state militia troops. Then on April 13, White League forces attacked the courthouse and massacred 50 black militiamen who had been captured. A total of 105 blacks were killed trying to defend the Colfax courthouse for Governor Kellogg. On April 21, Grant sent in the U.S. 19th Infantry Regiment (United States), 19th Infantry Regiment to restore order. On May 22, Grant issued a new proclamation to restore order in Louisiana. On May 31, McEnery finally told his followers to obey "peremptory orders" of the President. The orders brought a brief peace to New Orleans and most of Louisiana, except, ironically, Grant Parish.

A dispute arose over who would be installed as judge and sheriff at the Colfax, Louisiana, Colfax courthouse in Grant Parish, Louisiana, Grant Parish. Kellogg's two appointees had seized control of the Court House on March 25 with the aid and protection of black state militia troops. Then on April 13, White League forces attacked the courthouse and massacred 50 black militiamen who had been captured. A total of 105 blacks were killed trying to defend the Colfax courthouse for Governor Kellogg. On April 21, Grant sent in the U.S. 19th Infantry Regiment (United States), 19th Infantry Regiment to restore order. On May 22, Grant issued a new proclamation to restore order in Louisiana. On May 31, McEnery finally told his followers to obey "peremptory orders" of the President. The orders brought a brief peace to New Orleans and most of Louisiana, except, ironically, Grant Parish.

Brooks-Baxter war in Arkansas

In the fall of 1872, the Republican party split in Arkansas and ran two candidates for governor, Elisha Baxter and Joseph Brooks (politician), Joseph Brooks. Massive fraud characterized the election, but Baxter was declared the winner and took office. Brooks never gave up; finally, in 1874, a local judge ruled Brooks was entitled to the office and swore him in. Both sides mobilized militia units, and rioting and fighting bloodied the streets. Speculation swirled as to who President Grant would side with – either Baxter or Brooks. Grant delayed, requesting a joint session of the Arkansas government to figure out peacefully who would be the Governor, but Baxter refused to participate. On May 15, 1874, Grant issued a Proclamation that Baxter was the legitimate Governor of Arkansas, and hostilities ceased. In the fall of 1874 the people of Arkansas voted out Baxter, and Republicans and theVicksburg riots

In August 1874, the Vicksburg, Mississippi, Vicksburg city government elected White reform party candidates consisting of Republicans and Democrats. They promised to lower city spending and taxes. Despite such intentions, the reform movement turned racist when the new White city officials went after the county government, which had a majority of African Americans. The White League threatened the life of and expelled Crosby, the black Warren County, Mississippi, Warren County Sheriff and tax collector. Crosby sought help from Republican Governor Adelbert Ames to regain his position as sheriff. Governor Ames told him to take other African Americans and use force to retain his lawful position. At that time Vicksburg had a population of 12,443, more than half of whom were African American.. On December 7, 1874, Crosby and an African American militia approached Vicksburg. He had said that the Whites were, "ruffians, barbarians, and political banditti". A series of confrontations occurred against white paramilitary forces that resulted in the deaths of 29 African Americans and 2 Whites. The White militia retained control of the County Court House and jail. On December 21, Grant issued a Presidential Proclamation for the people in Vicksburg to stop fighting. General Philip Sheridan, based in Louisiana for this regional territory, dispatched federal troops, who reinstated Crosby as sheriff and restored the peace. When questioned about the matter, Governor Ames denied that he had told Crosby to use African American militia. On June 7, 1875, Crosby was shot to in the head by a white deputy while drinking in a bar. He survived, but never fully recovered from his injuries. The origins of the shooting remained a mystery.

Louisiana revolt and coups

On September 14, 1874, theCivil Rights Act of 1875

Throughout his presidency, Grant was continually concerned with the civil rights of all Americans, "irrespective of nationality, color, or religion." Grant had no role in writing the Civil Rights Act of 1875 but he did sign it a few days before the Republicans lost control of Congress. The new law was designed to allow everyone access to public eating establishments, hotels, and places of entertainment. This was done particularly to protect African Americans who were discriminated across United States. The bill was also passed in honor of SenatorSouth Carolina 1876

During the election year of 1876, South Carolina was in a state of rebellion against Republican governor Daniel Henry Chamberlain, Daniel H. Chamberlain. Conservatives were determined to win the election for ex-Confederate Wade Hampton III, Wade Hampton through violence and intimidation. The Republicans went on to nominate Chamberlain for a second term. Hampton supporters, donning red shirts, disrupted Republican meetings with gun shootings and yelling. Tensions became violent on July 8, 1876, when five African Americans were murdered at Hamburg, South Carolina, Hamburg. The rifle clubs, wearing their Red Shirts, were better armed than the blacks. South Carolina was ruled more by "mobocracy and bloodshed" than by Chamberlain's government.

Black militia fought back in Charleston, South Carolina, Charleston on September 6, 1876, in what was known as the "King Street riot". The white militia assumed defensive positions out of concern over possible intervention from federal troops. Then, on September 19, the Red Shirts took offensive action by openly killing between 30 and 50 African Americans outside Ellenton, South Carolina, Ellenton. During the massacre, state representative Simon Coker was killed. On October 7, Governor Chamberlain declared martial law and told all the "rifle club" members to put down their weapons. In the meantime, Wade Hampton never ceased to remind Chamberlain that he did not rule South Carolina. Out of desperation, Chamberlain wrote to Grant and asked for federal intervention. The "Cainhoy riot" took place on October 15 when Republicans held a rally at "Brick Church" outside Cainhoy. Blacks and whites both opened fire; six whites and one black were killed. Grant, upset over the Ellenton and Cainhoy riots, finally declared a Presidential Proclamation on October 17, 1876, and ordered all persons, within 3 days, to cease their lawless activities and disperse to their homes. A total of 1,144 federal infantrymen were sent into South Carolina, and the violence stopped; election day was quiet. Both Hampton and Chamberlain claimed victory, and for a while both acted as governor; Hampton took the office in 1877 after President

During the election year of 1876, South Carolina was in a state of rebellion against Republican governor Daniel Henry Chamberlain, Daniel H. Chamberlain. Conservatives were determined to win the election for ex-Confederate Wade Hampton III, Wade Hampton through violence and intimidation. The Republicans went on to nominate Chamberlain for a second term. Hampton supporters, donning red shirts, disrupted Republican meetings with gun shootings and yelling. Tensions became violent on July 8, 1876, when five African Americans were murdered at Hamburg, South Carolina, Hamburg. The rifle clubs, wearing their Red Shirts, were better armed than the blacks. South Carolina was ruled more by "mobocracy and bloodshed" than by Chamberlain's government.

Black militia fought back in Charleston, South Carolina, Charleston on September 6, 1876, in what was known as the "King Street riot". The white militia assumed defensive positions out of concern over possible intervention from federal troops. Then, on September 19, the Red Shirts took offensive action by openly killing between 30 and 50 African Americans outside Ellenton, South Carolina, Ellenton. During the massacre, state representative Simon Coker was killed. On October 7, Governor Chamberlain declared martial law and told all the "rifle club" members to put down their weapons. In the meantime, Wade Hampton never ceased to remind Chamberlain that he did not rule South Carolina. Out of desperation, Chamberlain wrote to Grant and asked for federal intervention. The "Cainhoy riot" took place on October 15 when Republicans held a rally at "Brick Church" outside Cainhoy. Blacks and whites both opened fire; six whites and one black were killed. Grant, upset over the Ellenton and Cainhoy riots, finally declared a Presidential Proclamation on October 17, 1876, and ordered all persons, within 3 days, to cease their lawless activities and disperse to their homes. A total of 1,144 federal infantrymen were sent into South Carolina, and the violence stopped; election day was quiet. Both Hampton and Chamberlain claimed victory, and for a while both acted as governor; Hampton took the office in 1877 after President Financial policy

Panic of 1873

Between 1868 and 1873, the American economy was robust, primarily caused by railroad building, manufacturing expansion, and thriving agriculture production. Financial debt, however, particularly in railroad investment, spread throughout both the private and federal sectors. The market began to break in July 1873 when the Brooklyn Trust Company went broke and closed. Secretary Richardson sold gold to pay for $14 million in federal bonds. Two months later, the Panic of 1873, collapsed the national economy. On September 17, the stock market crashed, followed by the New York Warehouse & Security Company, September 18, and the Jay Cooke & Company, September 19, both going bankrupt. On September 19, Grant ordered Secretary William Adams Richardson, Richardson, Boutwell's replacement, to purchase $10 million in bonds. Richardson complied using greenbacks to expand the money supply. On September 20, the New York Stock Exchange (''NYSE'') closed for ten days. Traveling to New York, Grant met with Richardson to consult with bankers, who gave Grant conflicting financial advice. Returning to Washington, Grant and Richardson sent millions of greenbacks from the treasury to New York to purchase bonds, stopping the purchases on September 24. By the beginning of January 1874, Richardson had issued a total of $26 million greenbacks from the Treasury reserve, into the economy, relieving Wall Street, but not stopping the national Long Depression, that would last 5 years. Thousands of businesses, depressed daily wages by 25% for three years, and brought the unemployment rate up to 14%.Inflation bill vetoed and compromise

Grant and Richardson's mildly inflationary response to the Panic of 1873, encouraged Congress to pursue a more aggressive policy. The legality of releasing greenbacks was presumed to have been illegal. On April 14, 1874, Congress passed the ''Inflation Bill'' that set the greenback maximum at $400,000 retroactively legalizing the $26 million reserve greenbacks earlier released by the Treasury. The bill released an additional $18 million in greenbacks up to the original $400,000,000 amount. Going further, the bill authorized an additional $46 million in banknotes and raised their maximum to $400 million. Eastern bankers vigorously lobbied Grant to veto the bill because of their reliance on bonds and foreign investors who did business in gold. Most of Grant's cabinet favored the bill in order to secure a Republican election. Grant's conservative Secretary of State

Grant and Richardson's mildly inflationary response to the Panic of 1873, encouraged Congress to pursue a more aggressive policy. The legality of releasing greenbacks was presumed to have been illegal. On April 14, 1874, Congress passed the ''Inflation Bill'' that set the greenback maximum at $400,000 retroactively legalizing the $26 million reserve greenbacks earlier released by the Treasury. The bill released an additional $18 million in greenbacks up to the original $400,000,000 amount. Going further, the bill authorized an additional $46 million in banknotes and raised their maximum to $400 million. Eastern bankers vigorously lobbied Grant to veto the bill because of their reliance on bonds and foreign investors who did business in gold. Most of Grant's cabinet favored the bill in order to secure a Republican election. Grant's conservative Secretary of State Resumption of Specie Act

On January 14, 1875, Grant signed the Resumption of Specie Act, and he could not have been happier; he wrote a note to Congress congratulating members on the passage of the act. The legislation was drafted by Ohio Republican Senator John Sherman (politician), John Sherman. This act provided that paper money in circulation would be exchanged for gold specie and silver coins and would be effective January 1, 1879. The act also implemented that gradual steps would be taken to reduce the number of greenbacks in circulation. At that time there were "paper coin" currency worth less than $1.00, and these would be exchanged for silver coins. Its effect was to stabilize the currency and make the consumers money as "good as gold". In an age without a Federal Reserve system to control inflation, this act stabilized the economy. Grant considered it the hallmark of his administration.Foreign policy

Foreign affairs were managed peacefully during Grant's second term in office. Historians credit Secretary of StateVirginus incident

On October 31, 1873, a steamer ''Virginius'', flying the American flag carrying war materials and men to aid the Cuban insurrection (in violation of American and Spanish law) was intercepted and taken to Cuba. After a hasty trial, the local Spanish officials executed 53 would-be insurgents, eight of whom were United States citizens; orders from Madrid to delay the executions arrived too late. War scares erupted in both the U.S. and Spain, heightened by the bellicose dispatches from the American minister in Madrid, retired general Daniel Sickles. Secretary of State Fish kept a cool demeanor in the crisis, and through investigation discovered there was a question over whether the ''Virginius'' ship had the right to bear the United States flag. The Spanish Republic's president Emilio Castelar expressed profound regret for the tragedy and was willing to make reparations through arbitration. Fish negotiated reparations with the Spanish minister Senor Polo de Barnabé. With Grant's approval, Spain was to surrender ''Virginius'', pay an indemnity to the surviving families of the Americans executed, and salute the American flag; the episode ended quietly. Grant also played a pivotal role in the affair. Grant sent American warships off of Florida and discussed Cuban invasion plans with General Sherman and the War Department. The bluff worked and the Spanish government accepted Grant's negotiated peace terms. Grant messaged Congress the incident was closed and national honor was restored. However, the salute of the American flag by the Spanish Navy was a stickler. When the Spanish returned the ''Virginus'' the Spanish Navy did not salute the American flag disputing that the ''Virginius'' was not an American-owned ship. The next day Grant's Attorney General George H. Williams ruled that the ''Virginus'' U.S. ownership was fraudulent, but the Spanish had no right to capture the ship.Hawaiian free trade treaty

In December 1874, Grant held a state dinner at the White House for the King of Hawaii, David Kalakaua, who was seeking the importation of Hawaiian sugar duty-free to the United States. Grant and Fish were able to produce a successful free trade treaty in 1875 with the Kingdom of Hawaii, incorporating the Pacific islands' sugar industry into the United States' economy sphere.Liberian-Grebo war

The U.S. settled the war between Liberia and the native Grebo people in 1876 by dispatching the to Liberia.Mexican border raids

At the close of Grant's second term in office, Fish had to contend with Indian raids on the Mexican border, due to a lack of law enforcement over the U.S.–Mexican border. The problem would escalate during the Hayes administration, under Fish's successor William Evarts.Native American policy

Under Grant's ''Peace'' policy, wars between settlers, the federal army, and the American Indians had been decreasing from 101 per year in 1869 to a low of 15 per year in 1875. However, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory and the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway, threatened to unravel Grant's Indian policy, as white settlers encroached upon native land to mine for gold. In his second term of presidential office, Grant's fragile ''Peace'' policy came apart. Major General Edward Canby was killed in the Modoc War. Indian wars per year jumped up to 32 in 1876 and remained at 43 in 1877. One of the highest casualty Indian battles that took place in American history was at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Indian war casualties in Montana went from 5 in 1875, to 613 in 1876 and 436 in 1877.Modoc War

In January 1873, Grant's Native American peace policy was challenged. Two weeks after Grant was elected for a second term, fighting broke out between the Modocs and settlers near the California-Oregon border. The Modocs, led by Kintpuash, Captain Jack, killed 18 white settlers and then found a strong defensive position. Grant ordered General Sherman not to attack the Indians but settle matters peacefully with a commission. Sherman then sent Major General Edward Canby, but Captain Jack killed him. Reverend Eleazar Thomas, a Methodist minister, was also killed. Alfred B. Meacham, an Indian Agent, was severely wounded. The murders shocked the nation, and Sherman wired to have the Modocs exterminated. Grant overruled Sherman; Captain Jack was executed, and the remaining 155 Modocs were relocated to the Quapaw Agency in the Indian Territory. This episode and the Great Sioux War undermined public confidence in Grant's peace policy, according to historian Robert M. Utley. During the peace negotiations between Brig. Gen. Edward Canby and the Modoc tribal leaders, there were more Indians in the tent then had been agreed upon. As the Indians grew more hostile, Captain Jack, said "I talk no more." and shouted "All ready." Captain Jack drew his revolver and fired directly into the head of Gen Canby. Brig. Gen Canby was the highest-ranking officer to be killed during the Indian Wars that took place from 1850 to 1890. Alfred Meacham, who survived the massacre, defended the Modocs who were put on trial.Red River War

In 1874, war erupted on the southern Plains when Quanah Parker, leader of the Comanche, led 700 tribal warriors and attacked the buffalo hunter supply base on the Canadian River, at Adobe Walls, Texas. The Army under General Phil Sheridan launched a military campaign, and, with few casualties on either side, forced the Indians back to their reservations by destroying their horses and winter food supplies. Grant, who agreed to the Army plan advocated by Generals William T. Sherman and Phil Sheridan, imprisoned 74 insurgents in Florida.Great Sioux War

In 1874 gold had been discovered in the Black Hills in the Dakota Territory. White speculators and settlers rushed in droves seeking riches mining gold on land reserved for the Sioux tribe by the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868. These prospectors treated the natives unfairly when they moved into the area. In 1875, to avoid conflict Grant met with Red Cloud, chief of the Sioux and offered $25,000 from the government to purchase the land. The offer was declined. On November 3, 1875, at a White House meeting, Phil Sheridan told the President that the Army was overstretched and could not defend the Sioux tribe from the settlers; Grant ordered Sheridan to round up the Sioux and put them on the reservation. Sheridan used a strategy of convergence, using Army columns to force the Sioux onto the reservation. On June 25, 1876, one of these columns, led by Colonel George A. Custer met the Sioux at the Battle of Little Big Horn and part of his command was slaughtered. Approximately 253 federal soldiers and civilians were killed compared to 40 Indians. Custer's death and the Battle of Little Big Horn shocked the nation. Sheridan avenged Custer, pacified the northern Plains, and put the defeated Sioux on the reservation. On August 15, 1876, President Grant signed a proviso giving the Sioux nation $1,000,000 in rations, while the Sioux relinquished all rights to the Black Hills, except for a 40-mile land tract west of the 103rd meridian. On August 28, a seven-man committee, appointed by Grant, gave additional harsh stipulations for the Sioux in order to receive government assistance. Halfbreeds and "squaw men" (A white man with an Indian wife) were banished from the Sioux reservation. To receive the government rations, the Indians had to work the land. Reluctantly, on September 20, the Indian leaders, whose people were starving, agreed to the committee's demands and signed the agreement. During the Great Sioux War, Grant came into conflict with Col. George Armstrong Custer after he testified in 1876 about corruption in the War Department under SecretaryDomestic policy

Religion and schools

Grant believed strongly in the separation of church and state and championed complete secularization in public schools. In a September 1875 speech, Grant advocated "security of free thought, free speech, and Freedom of the press, free press, pure morals, unfettered religious sentiments, and of equal rights and privileges to all men, irrespective of nationality, color, or religion." In regard to public education, Grant endorsed that every child should receive "the opportunity of a good common school education, unmixed with sectarian, pagan, or atheist tenets. Leave the matter of religion to the family altar, the church, and the private schools... Keep the church and the state forever separate." In a speech in 1875 to a veteran's meeting, Grant called for a Constitutional amendment that would mandate free public schools and prohibit the use of public money for sectarian schools. He was echoing nativist sentiments that were strong in his Republican Party. Tyler Anbinder says, "Grant was not an obsessive nativist. He expressed his resentment of immigrants and animus toward Catholicism only rarely. But these sentiments reveal themselves frequently enough in his writings and major actions as general....In the 1850s he joined a Know Nothing lodge and irrationally blamed immigrants for setbacks in his career." Grant laid out his agenda for "good common school education". He attacked government support for "sectarian schools" run by religious organizations and called for the defense of public education "unmixed with sectarian, pagan or atheistical dogmas." Grant declared that "Church and State" should be "forever separate." Religion, he said, should be left to families, churches, and private schools devoid of public funds. After Grant's speech Republican Congressman James G. Blaine proposed the amendment to the federal Constitution. Blaine believed that possibility of hurtful agitation on the school question should be ended. In 1875, the proposed amendment passed by a vote of 180 to 7 in the House of Representatives, but failed by four votes to achieve the necessary two-thirds vote in the Senate. Nothing like it ever became federal legislation. However, many states did adopt similar amendments to their state constitution. The proposed Blaine Amendment text was:Polygamy and Chinese prostitution

In October 1875, Grant traveled to Utah and was surprised that the Mormons treated him kindly. He told the Utah territorial governor, George W. Emery, that he had been deceived concerning the Mormons. However, on December 7, 1875, after his return to Washington, Grant wrote to Congress in his seventh annual State of the Union address that as "an institution polygamy should be banished from the land…" Grant believed that polygamy negatively affected children and women. Grant advocated that a second law, stronger than the Morrill Act, be passed to "punish so flagrant a crime against decency and morality." Grant also denounced the immigration of Chinese women into the United States for the purposes of prostitution, saying that it was "no less an evil" than polygamy.Interactions with Jews

Grant publicly stated regret for his offensive wartime order expelling Jewish traders. In his army days, he traded at a local store operated by the Seligman brothers, two Jewish merchants who became Grant's lifelong friends. They J. & W. Seligman & Co., became wealthy bankers who donated substantially to Grant's presidential campaign. After the wartime order, however, the Jewish community was angry with Grant. While running for president, in 1868, Grant publicly apologized for the expulsion order, and once elected, he took actions intended to make amends. He appointed several Jewish leaders to office, including Simon Wolf recorder of deeds in Washington, D.C., and Edward S. Salomon Governor of the Washington Territory. Historian Jonathan Sarna argues:Eager to prove that he was above prejudice, Grant appointed more Jews to public office than had any of his predecessors and, in the name of human rights, he extended unprecedented support to persecuted Jews in Russia and Romania. Time and again, partly as a result of this enlarged vision of what it meant to be an American and partly in order to live down General Orders No. 11, Grant consciously worked to assist Jews and secure them equality. ... Through his appointments and policies, Grant rejected calls for a 'Christian nation' and embraced Jews as insiders in America, part of 'we the people.' During his administration, Jews achieved heightened status on the national scene, anti-Jewish prejudice declined, and Jews looked forward optimistically to a liberal epoch characterized by sensitivity to human rights and interreligious cooperation.

Midterm election 1874

As the 1874 midterm elections approached, three scandals, the Crédit Mobilier scandal, Crédit Mobilier, the Salary Grab Act, Salary Grab, and the Sanborn incident caused the public to view the Republican Party as mired in corruption. The Democratic Party held the Republican Party responsible for the Long Depression. The Republicans were divided on the currency issue. Grant, who with hard money Northeastern Republicans, vetoed an inflation bill. Grant was blamed for the nation's problems, while he was accused of wanting a third term. Grant never officially campaigned, but traveled West, to emphasize his relatively popular Indian policy. The October elections swept the Republicans from office and was a repudation of Grant's veto. In Indiana and Ohio, the Republicans suffered losses, caused by the money issue and the temperance movement. The Democratic Party won the New York governorship for Samuel Tilden. The Democrats won the U.S. House, gaining 182 seats, while the Republicans retained 103 seats. The Republicans retained control of the Senate, but the new class included 14 Democrats and 11 Republicans. The Democratic Party also had strong victories in New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Missouri, and Illinois. In the South, the 1874 election campaign was violent. Six Republican office holders were murdered in Coushatta, Louisiana. On September 14, General Longstreet, police, and black militia fought 3,500 White Leaguers who attempted to capture the statehouse in New Orleans, that ended with 32 people killed. Grant issued a dispersal proclamation, the next day, and sent 5,000 troops and 5 gunboats to New Orleans. TheReforms and scandals

Scandals and frauds continued to be exposed during Grant's second term in office, although Grant's appointments of reformers to his cabinet temporarily helped his presidential reputation, cleaned up federal departments, and defeated the notoriousSanborn contracts

In June 1874, Treasury Secretary William Adams Richardson, William A. Richardson gave private contracts to one John D. Sanborn who in turn collected illegally withheld taxes for fees at inflated commissions. The profits from the commissions were allegedly split with Richardson and SenatorPratt & Boyd

In April 1875, it was discovered that Attorney General George H. Williams allegedly received a bribe through a $30,000 gift to his wife from a Merchant house company, Pratt & Boyd, to drop the case for fraudulent customhouse entries. Williams was forced to resign by Grant in 1875.Delano's Department of Interior

By 1875, the Department of the Interior under Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano was in serious disrepair with corruption and fraud. Profiteering prevailed in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, controlled by corrupt clerks and bogus agents. This proved to be the most serious detriment to Grant's Indian peace policy. Many agents that worked for the department made unscrupulous fortunes and retired with more money than their pay would allow at the expense and exploitation of Native Americans of the United States, Native Americans. Delano had allowed "Indian Attorneys" who were paid by Native American tribes $8.00 a day plus food and travel expenses for sham representation in Washington. Delano exempted his department from Grant's civil service reform implementation in federal offices. Delano told Grant the Interior Department was too large to implement civil service reform. Delano's son, John Delano, and Ulysses S. Grant's own brother, Orvil Grant, were discovered to have been awarded lucrative corrupt cartographical contracts by Surveyor General Silas Reed. Neither John Delano nor Orvil Grant performed any work or were qualified to hold such surveying positions. Massive fraud was also found in the Patent Office with corrupt clerks who embezzled from the government payroll. Under increasing pressure by the press and Indian reformers, Delano resigned from office on October 15, 1875. Grant then appointed Zachariah Chandler as Secretary of the Interior who replaced Delano. Chandler vigorously uncovered and cleaned up the fraud in the department by firing all the clerks and banned the phony "Indian Attorneys" access to Washington. Grant's "Quaker" or church appointments partially made up the lack of food staples and housing from the government. Chandler cleaned up the Patent Office by firing all the corrupt clerks.Whiskey Ring prosecuted

Grant's presidency is often criticized for scandals, though Grant also appointed many reformers. In May 1875, Secretary of TreasuryTrading post ring

In March 1876 it was discovered under House investigations that Secretary of WarCattellism

In March 1876, Secretary of Navy George M. Robeson was charged by a Democratic-controlled House investigation committee with giving lucrative contracts to Alexander Cattell & Company, a grain supplier, in return for real estate, loans, and payment of debts. The House investigating committee also discovered that Secretary Robeson had allegedly embezzled $15 million in naval construction appropriations. Since there were no financial paper trails or enough evidence for impeachment and conviction, the House Investigation committee admonished Robeson and claimed he had set up a corrupt contracting system known as "Cattellism".Safe burglary conspiracy

In September 1876, Orville E. Babcock, Superintendent of Public Works and Buildings, was indicted in a safe burglary Conspiracy (crime), conspiracy case and trial. In April, corrupt building contractors in Washington, D.C. were on trial for graft when a safe robbery occurred. Bogus secret service agents broke into a safe and attempted to frame Columbus Alexander, who had exposed the corrupt contracting ring. Babcock was named as part of the conspiracy, but later acquitted in the trial against the burglars. Evidence suggests that Backcock was involved with the Confidence trick, swindles by the corrupt Washington Contractors Ring and he wanted revenge on Columbus Alexander, an avid reformer and critic of the Grant Administration. There was also evidence that safe burglary jury had been tampered with.''The New York Times'' 1876Centennial Exposition

file:Centennial Exhibition, Opening Day.jpg, On the morning of May 10, 1876 the Centennial Exposition opened at Philadelphia's Fairmont Park. Thousands were in attendance on the Philadelphia streets. Grant rose to speak saying the Exposition would "show in the direction of rivaling older and more advanced nations in law, medicine, and theology --- in science literature, philosophy, and the fine arts."Election of 1876

In the 1876 United States presidential election, presidential election of 1876, the Republicans nominated the fiscally conservativeThird term attempt 1880

At the 1880 Republican Convention held in Chicago, Grant's Republican delegates, known as the ''306'', attempted to nominate Grant the Republican nominee, to run for a third presidential term. However, on the thirty-sixth ballot, the Republicans nominated Ohio Congressman James Garfield, with 399 votes. Grant, himself, did not attend the Convention in person.Historical evaluations

Grant's presidency has traditionally been viewed by historians as incompetent and full of corruption. An examination of his presidency reveals Grant had both successes and failures during his two terms in office. In recent years historians have elevated his presidential rating because of his support for African American civil rights. Grant had urged the passing of the 15th Amendment and signed into law the Civil Rights Bill of 1875 that gave all citizens access to places of public enterprise. He leaned heavily toward the Radical camp and often sided with their Reconstruction policies, signing into law Force Acts to prosecute the"A Better President Than They Think"

''The Weekly Standard'' (August 3, 1998). Barone argues that: "This consensus, however, is being challenged by writers outside the professional historians' guild." Barone points to a lawyer Frank Scaturro, who led the movement to restore Grant's Tomb while only a college student, and in 1998 wrote the first book of the modern era which portrays Grant's presidency in a positive light. Barone said that Scaturro's work was a "convincing case that Grant was a strong and, in many important respects, successful president. It is an argument full of significance for how we see the course of American political history ... Scaturro's work ... should prompt a reassessment of the entire Progressive-New Deal Tradition." In the 21st Century, Grant's reputation and ranking had significantly increased, that followed a series of positive biographies written by noted historians, that included Jean Edward Smith, ''Grant'', H.W. Brands, ''The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace'' and most recently Ronald C. White, ''American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant''. Historian Joan Waugh said Grant took steps where a few other presidents attempted "in the areas of Native American policy, civil service reform, and African American rights." Waugh said Grant "executed a successful foreign policy and was responsible for improving Anglo-American relations." Interest in his presidency has also increased by historians, that included Josiah Bunting III, Josiah H Bunting III, ''Ulysses S. Grant: The American Presidents Series: The 18th President''.

Administration and cabinet

Judicial appointments

Grant appointed four Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States during his presidency. When Grant took office, there were eight seats on the bench. Congress had passed a Judicial Circuits Act in 1866, which provided for the elimination of one seat on the Court each time a justice retired, to prevent Andrew Johnson from nominating replacements for them. In April 1869 Congress passed a Judiciary Act of 1869, Judiciary Act which fixed the size of the Supreme Court at nine. Grant had the opportunity to fill two Supreme Court seats in 1869. His initial nominees were: * Ebenezer R. Hoar, nominated December 14, 1869, was rejected by the Senate (Vote: 24–33) on February 3, 1870. * Edwin M. Stanton, nominated December 20, 1869, confirmed by the Senate (vote: 46–11) on December 20, 1869, died before he took office. He subsequently submitted two more nominees who were successfully appointed: * William Strong (Pennsylvania judge), William Strong, nominated February 7, 1870, confirmed by the Senate on February 18, 1870. * Joseph P. Bradley, nominated February 7, 1870, confirmed by the Senate (vote: 46–9) on March 21, 1870. Both men were railroad lawyers, and their appointment led to accusations that Grant intended them to overturn the case of ''Hepburn v. Griswold,'' which had been decided the same day they were nominated. That case, which was unpopular with business interests, held that the federal debt incurred before 1862 must be paid in gold, not greenbacks. Nonetheless, both Strong and Bradley were confirmed, and the following year ''Hepburn'' was indeed reversed. Grant had the opportunity to fill two more seats during his second term. To fill the first vacancy, he nominated: * Ward Hunt, nominated December 3, 1872, confirmed by the Senate on December 11, 1872. In May 1873, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase died suddenly. Grant initially offered the seat to Senator Roscoe Conkling, who declined, as did Senator Timothy Howe. Grant made three attempts to fill vacancies: * George Henry Williams, nominated December 1, 1873, withdrawn on January 8, 1874. The Senate had a dim view of Williams's performance at the Justice Department and refused to act on the nomination. * Caleb Cushing, nominated January 9, 1874, withdrawn on January 13, 1874. Cushing was an eminent lawyer and respected in his field, but the emergence of his wartime correspondence with Jefferson Davis doomed his nomination. * Morrison Waite, nominated January 19, 1874, confirmed by the Senate (vote: 63–0) on January 21, 1874. Waite was an uncontroversial nominee, but in his time on the Court he authored two of the decisions (''United States v. Reese'' and ''United States v. Cruikshank'') that did the most to undermine Reconstruction-era laws for the protection of black Americans.States admitted to the Union

* Colorado – August 1, 1876Vetoes

Grant vetoed more bills than any of his predecessors with 93 vetoes during the 41st through 44th Congresses. 45 were regular vetoes, and 48 of them were pocket vetoes. Grant had 4 vetoes overridden by Congress.Clerk of the United States House of Representatives.Memorials and monuments

* Grant's Tomb * Ulysses S. Grant Memorial

* Statue of Ulysses S. Grant (U.S. Capitol), Statue of Ulysses S. Grant

* Ulysses S. Grant Memorial

* Statue of Ulysses S. Grant (U.S. Capitol), Statue of Ulysses S. GrantGovernment agencies instituted

*Notes

Citations

Bibliography

By author

* * * * * * * * * * Chamberlain reviewed speech by Charles Francis Adams, Jr., Charles Francis Adams to New York Historical Society on November 19, 1901. * * ; online review * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * , Pulitzer prize, but hostile to Grant * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Simpson, Brooks D. ''The Reconstruction Presidents'' (1998) pp. 133–196 on Grant. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *By title (anonymous)

* * * * *Newspaper articles

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * Buenker, John D. and Joseph Buenker, eds. ''Encyclopedia of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' (2005). 1256 pp. in three volumes. 900 essays by 200 scholars * Donald, David Herbert. ''Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man'' (1970), Pulitzer Prize–winning biography of Grant's enemy in the Senate * Fitzgerald, Michael W. ''Splendid Failure: Postwar Reconstruction in the American South.'' (2007) 234 pp. * Foner, Eric. ''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877'' (1988), Pulitzer Prize–winning synthesis from Neoabolitionism (race relations), neoabolitionist perspective * Jennifer Graber, Graber, Jennifer. If a War It May Be Called' The Peace Policy with American Indians." ''Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation'' (2014) 24#1 pp: 36–69. * * * McCullough, Stephen. "Avoiding war: the foreign Policy of Ulysses S. Grant and Hamilton Fish." in Edward O. Frantz, ed., '' A Companion to the Reconstruction Presidents 1865–1881'' (2014): 311+ * , major scholarly biography * * Mantell, Martin E. ''Johnson, Grant, and the Politics of Reconstruction'' (1973online edition

* * * * Perret, Geoffrey. ''Ulysses S. Grant: Soldier & President'' (2009). popular biography * Priest, Andrew. "Thinking about Empire: The Administration of Ulysses S. Grant, Spanish Colonialism and the Ten Years' War in Cuba." ''Journal of American Studies'' (2014) 48#2 pp: 541–558. * * Rahill, Peter J. ''The Catholic Indian Missions and Grant's Peace Policy 1870–1884'' (1953

online

* Simpson, Brooks D. ''The Reconstruction Presidents'' (1998) * * Smith, Robert C. "Presidential Responsiveness to Black Interests From Grant to Biden: The Power of the Vote, the Power of Protest." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 52.3 (2022): 648–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12762 * Tatum, Lawrie. ''Our Red Brothers and the Peace Policy of President Ulysses S. Grant'' (2010) * Thompson, Margaret S. ''The "Spider Web": Congress and Lobbying in the Age of Grant'' (1985) * Trefousse, Hans L. ''Historical Dictionary of Reconstruction'' Greenwood (1991), 250 entries * * * Williams, Frank J. "Grant and Heroic Leadership." in Edward O. Frantz, ed., '' A Companion to the Reconstruction Presidents 1865–1881'' (2014): 343–352. * Woodward, C. Vann. ed. ''Responses of the Presidents to Charges of Misconduct'' (1974), essays by historians on each administration from George Washington to Lyndon Johnson. * Woodward, C. Vann. ''Reunion and Reaction'' (1950) on bargain of 1877

Primary sources

* * Simon, John Y., ed., ''The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant'', Southern Illinois University Press (1967–2009complete in 31 volumes

*

Online version vol 1–31

vol 19–28 (1994–2005) cover the presidential years; includes all known letters and writing by Grant, and the most important letters written to him. * James D. Richardson, Richardson, James, ed. ''Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents'' (numerous editions, 1901–20), vol 7 contains most of Grant's official presidential public documents and messages to Congress

1869 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1870 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1871 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1872 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1873 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1874 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1875 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1876 State of the Union Message – Ulysses S. Grant

1869 Inaugural Address – Ulysses S. Grant

1873 Inaugural Address – Ulysses S. Grant

* * * * * *

Yearbooks

* ''American Annual Cyclopedia...1868'' (1869)online

highly detailed compendium of facts and primary sources * ''American Annual Cyclopedia...for 1869'' (1870), large compendium of facts, thorough national coverage; includes also many primary document

online edition

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1870''

(1871)

''American Annual Cyclopedia...for 1872''

(1873)

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1873''

(1879)

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1875''

(1877)

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia ...for 1876''

(1885)

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1877''

(1878) *

External links

* * *Extensive essay on Ulysses S. Grant and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet from the Miller Center of Public Affairs, U. of Virginia

{{Republican Party (United States) Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, 1860s in the United States 1870s in the United States Ulysses S. Grant, *Presidency Schuyler Colfax Henry Wilson 1869 establishments in the United States 1877 disestablishments in the United States Presidencies of the United States, Grant, Ulysses S.