US Declaration of Independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House (later renamed Independence Hall) in

By the time the Declaration of Independence was adopted in July 1776, the

By the time the Declaration of Independence was adopted in July 1776, the

In 1774, Parliament passed the

In 1774, Parliament passed the

online

, published by the

Some colonists still hoped for reconciliation, but public support for independence further strengthened in early 1776. In February 1776, colonists learned of Parliament's passage of the Prohibitory Act, which established a blockade of American ports and declared American ships to be enemy vessels.

Some colonists still hoped for reconciliation, but public support for independence further strengthened in early 1776. In February 1776, colonists learned of Parliament's passage of the Prohibitory Act, which established a blockade of American ports and declared American ships to be enemy vessels.

Support for a Congressional declaration of independence was consolidated in the final weeks of June 1776. On June 14, the Connecticut Assembly instructed its delegates to propose independence and, the following day, the legislatures of New Hampshire and Delaware authorized their delegates to declare independence. In Pennsylvania, political struggles ended with the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and a new Conference of Committees under

Support for a Congressional declaration of independence was consolidated in the final weeks of June 1776. On June 14, the Connecticut Assembly instructed its delegates to propose independence and, the following day, the legislatures of New Hampshire and Delaware authorized their delegates to declare independence. In Pennsylvania, political struggles ended with the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and a new Conference of Committees under

Congress ordered that the draft "lie on the table" and then methodically edited Jefferson's primary document for the next two days, shortening it by a fourth, removing unnecessary wording, and improving sentence structure. They removed Jefferson's assertion that King George III had forced

Congress ordered that the draft "lie on the table" and then methodically edited Jefferson's primary document for the next two days, shortening it by a fourth, removing unnecessary wording, and improving sentence structure. They removed Jefferson's assertion that King George III had forced

The Paragraph Missing From The Declaration of Independence

'', The Shipler Report, July 4, 2020 in order to moderate the document and appease those in South Carolina and Georgia, both states which had significant involvement in the On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of

On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of  There is a distinct change in wording from this original broadside printing of the Declaration and the final official engrossed copy. The word "unanimous" was inserted as a result of a Congressional resolution passed on July 19, 1776: "Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Historian George Athan Billias says: "Independence amounted to a new status of interdependence: the United States was now a sovereign nation entitled to the privileges and responsibilities that came with that status. America thus became a member of the international community, which meant becoming a maker of treaties and alliances, a military ally in diplomacy, and a partner in foreign trade on a more equal basis."

There is a distinct change in wording from this original broadside printing of the Declaration and the final official engrossed copy. The word "unanimous" was inserted as a result of a Congressional resolution passed on July 19, 1776: "Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Historian George Athan Billias says: "Independence amounted to a new status of interdependence: the United States was now a sovereign nation entitled to the privileges and responsibilities that came with that status. America thus became a member of the international community, which meant becoming a maker of treaties and alliances, a military ally in diplomacy, and a partner in foreign trade on a more equal basis."

Historians have often sought to identify the sources that most influenced the words and

Historians have often sought to identify the sources that most influenced the words and

The Declaration became official when Congress recorded its vote adopting the document on July 4; it was transposed on paper and signed by

The Declaration became official when Congress recorded its vote adopting the document on July 4; it was transposed on paper and signed by

The signatories include then future presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, though the most legendary signature is John Hancock’s. His large, flamboyant signature became iconic, and the term ''John Hancock'' emerged in the United States as a metaphor of "signature". A commonly circulated but apocryphal account claims that, after Hancock signed, the delegate from Massachusetts commented, "The British ministry can read that name without spectacles." Another report indicates that Hancock proudly declared, "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

A legend emerged years later about the signing of the Declaration, after the document had become an important national symbol. John Hancock is supposed to have said that Congress, having signed the Declaration, must now "all hang together", and Benjamin Franklin replied: "Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." That quotation first appeared in print in an 1837 London humor magazine.

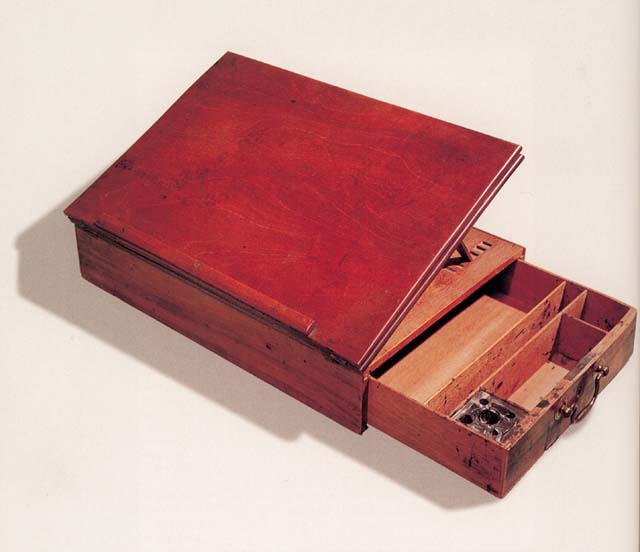

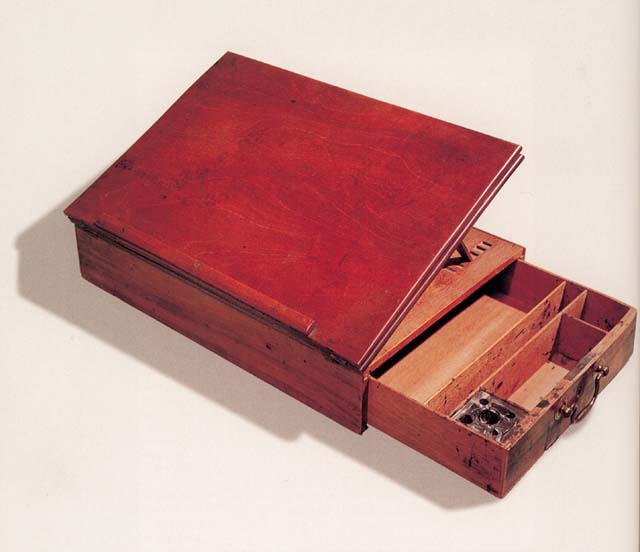

The Syng inkstand used at the signing was also used at the signing of the United States Constitution in 1787.

The signatories include then future presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, though the most legendary signature is John Hancock’s. His large, flamboyant signature became iconic, and the term ''John Hancock'' emerged in the United States as a metaphor of "signature". A commonly circulated but apocryphal account claims that, after Hancock signed, the delegate from Massachusetts commented, "The British ministry can read that name without spectacles." Another report indicates that Hancock proudly declared, "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

A legend emerged years later about the signing of the Declaration, after the document had become an important national symbol. John Hancock is supposed to have said that Congress, having signed the Declaration, must now "all hang together", and Benjamin Franklin replied: "Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." That quotation first appeared in print in an 1837 London humor magazine.

The Syng inkstand used at the signing was also used at the signing of the United States Constitution in 1787.

One of the first readings of the Declaration by the British is believed to have taken place at the Rose and Crown Tavern on

One of the first readings of the Declaration by the British is believed to have taken place at the Rose and Crown Tavern on

The document signed by Congress and enshrined in the National Archives is usually regarded as ''the'' Declaration of Independence, but historian Julian P. Boyd argued that the Declaration, like Magna Carta, is not a single document. Boyd considered the printed broadsides ordered by Congress to be official texts, as well. The Declaration was first published as a broadside that was printed the night of July 4 by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. Dunlap printed about 200 broadsides, of which 26 are known to survive. The 26th copy was discovered in

The document signed by Congress and enshrined in the National Archives is usually regarded as ''the'' Declaration of Independence, but historian Julian P. Boyd argued that the Declaration, like Magna Carta, is not a single document. Boyd considered the printed broadsides ordered by Congress to be official texts, as well. The Declaration was first published as a broadside that was printed the night of July 4 by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. Dunlap printed about 200 broadsides, of which 26 are known to survive. The 26th copy was discovered in

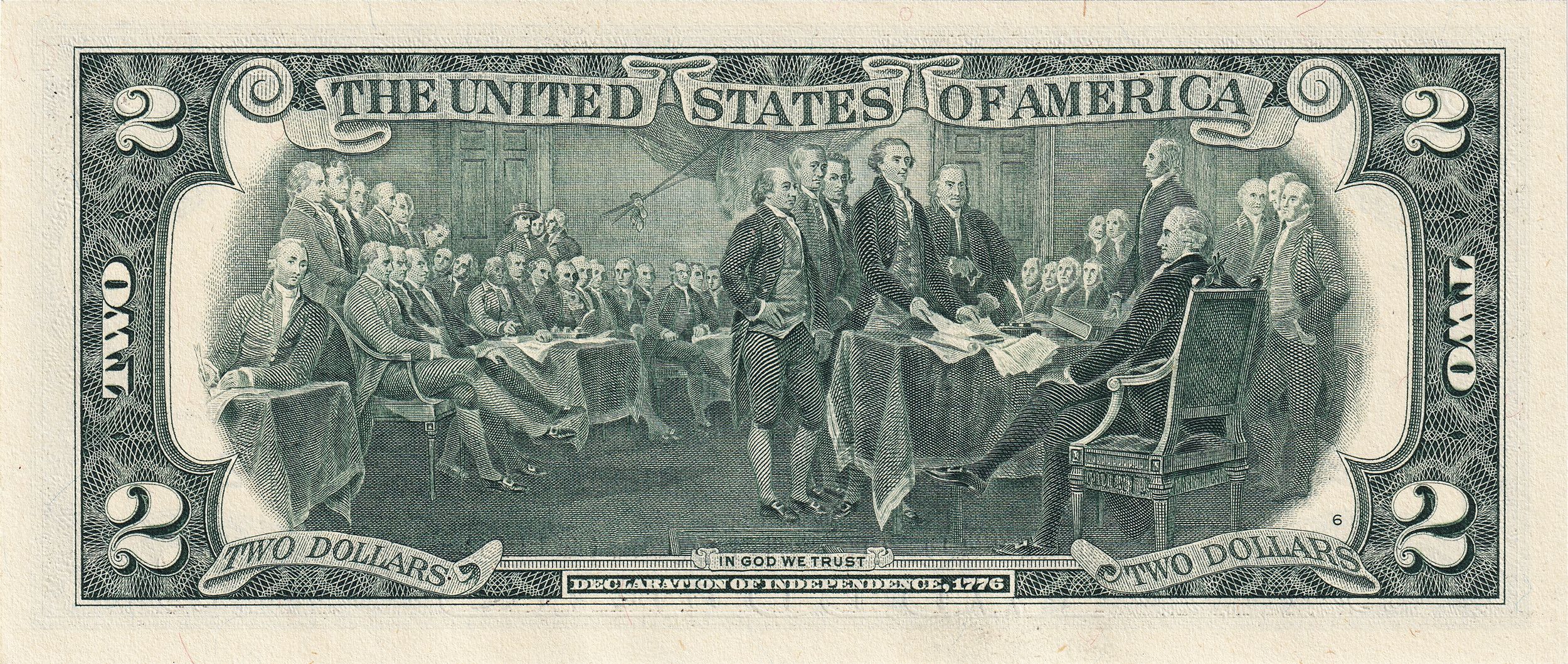

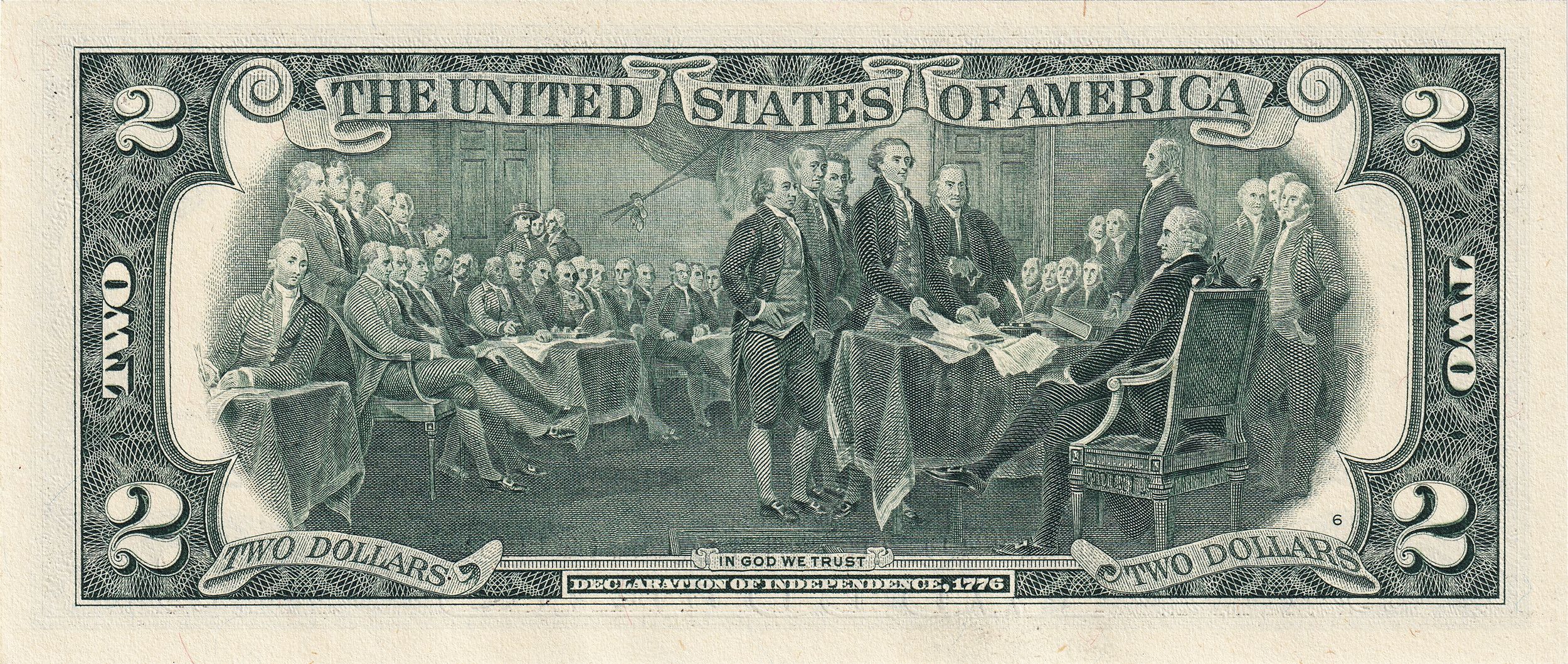

John Trumbull's painting ''Declaration of Independence'' has played a significant role in popular conceptions of the Declaration of Independence. The painting is in size and was commissioned by the

John Trumbull's painting ''Declaration of Independence'' has played a significant role in popular conceptions of the Declaration of Independence. The painting is in size and was commissioned by the

Project Gutenberg

. abolitionist John Brown had many copies printed of a

The Declaration's relationship to slavery was taken up in 1854 by

The Declaration's relationship to slavery was taken up in 1854 by

"The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original"

. ''Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 100, number 4 (October 1976), 438–67. * * Christie, Ian R. and Benjamin W. Labaree. ''Empire or Independence, 1760–1776: A British-American Dialogue on the Coming of the American Revolution''. New York: Norton, 1976. * Dumbauld, Edward. ''The Declaration of Independence And What It Means Today''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950. * Dupont, Christian Y. and Peter S. Onuf, eds. ''Declaring Independence: The Origins and Influence of America's Founding Document''. Revised edition. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Library, 2010. . * * * Gustafson, Milton

. ''Prologue Magazine'' 34, no 4 (Winter 2002). * Hamowy, Ronald. "Jefferson and the Scottish Enlightenment: A Critique of Garry Wills's ''Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence''". ''William and Mary Quarterly'', 3rd series, 36 (October 1979), 503–23. * Hazelton, John H. ''The Declaration of Independence: Its History''. Originally published 1906. New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. . 1906 edition available o

Google Book Search

* Journals of the Continental Congress,1774–1789, Vol. 5 ( Library of Congress, 1904–1937) * Lucas, Stephen E., "Justifying America: The Declaration of Independence as a Rhetorical Document", in Thomas W. Benson, ed., ''American Rhetoric: Context and Criticism'', Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1989 * * * Malone, Dumas. ''Jefferson the Virginian''. Volume 1 of ''Jefferson and His Time''. Boston: Little Brown, 1948. * * Mayer, Henry. ''All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. . * McDonald, Robert M. S. "Thomas Jefferson's Changing Reputation as Author of the Declaration of Independence: The First Fifty Years". ''Journal of the Early Republic'' 19, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 169–95. * Middlekauff, Robert. ''The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789''. Revised and expanded edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. * Norton, Mary Beth, ''et al''., ''A People and a Nation'', Eighth Edition, Boston, Wadsworth, 2010. . * * Ritz, Wilfred J. "The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776". ''Law and History Review'' 4, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 179–204. * Ritz, Wilfred J

"From the ''Here'' of Jefferson's Handwritten Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence to the ''There'' of the Printed Dunlap Broadside"

. ''Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 116, no. 4 (October 1992): 499–512. * * Warren, Charles. "Fourth of July Myths". ''The William and Mary Quarterly'', Third Series, vol. 2, no. 3 (July 1945): 238–72. . * United States Department of State,

The Declaration of Independence, 1776

1911. * * Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. ''Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War Against Slavery''. Cleveland: Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1969. . * “Declaration of Sentiments Full Text - Text of Stanton’s Declaration - Owl Eyes.” Owleyes.org, 2018. * NPR. “Read Martin Luther King Jr.'s ‘I Have a Dream" Speech in Its Entirety.” NPR.org. NPR, January 18, 2010.

"That's What America Is"

, Harvey Milk,

"Declare the Causes: The Declaration of Independence"

lesson plan for grades 9–12 from National Endowment for the Humanities

* /uscon.mobi/ind/ Mobile-friendly Declaration of Independence {{Authority control

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, on July 4, 1776. Enacted during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, the Declaration explains why the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

at war with the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

regarded themselves as thirteen independent sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined te ...

s, no longer subject to British colonial rule. With the Declaration, these new states took a collective first step in forming the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

and, de facto, formalized the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, which had been ongoing since April 1775.

The Declaration of Independence was signed by 56 of America's Founding Fathers, congressional representatives from New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

, Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

, Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

, New York, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

, South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. The Declaration became one of the most circulated and widely reprinted documents in early American history.

The Lee Resolution

The Lee Resolution (also known as "The Resolution for Independence") was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2, 1776 which resolved that the Thirteen Colonies in America (at the time referred to as United Colo ...

for independence was passed unanimously by the Congress on July 2. The Committee of Five

''

The Committee of Five of the Second Continental Congress was a group of five members who drafted and presented to the full Congress in Pennsylvania State House what would become the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Thi ...

had drafted the Declaration to be ready when Congress voted on independence. John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

, a leader in pushing for independence, had persuaded the committee to select Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

to compose the original draft of the document, which Congress edited. The Declaration was a formal explanation of why Congress had voted to declare independence from Great Britain, more than a year after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

After ratifying the text on July 4, Congress issued the Declaration of Independence in several forms. It was initially published as the printed Dunlap broadside that was widely distributed and read to the public. Jefferson's original draft is preserved at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

, complete with changes made by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, as well as Jefferson's notes of changes made by Congress. The best-known version of the Declaration is a signed copy that is displayed at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and which is popularly regarded as the official document. This engrossed

Western calligraphy is the art of writing and penmanship

as practiced in the Western world, especially using the Latin alphabet (but also including calligraphic use of the Cyrillic and Greek alphabets, as opposed to "Eastern" traditions such as ...

copy was ordered by Congress on July 19 and signed primarily on August 2.

The sources and interpretation of the Declaration have been the subject of much scholarly inquiry. The Declaration justified the independence of the United States by listing 27 colonial grievances

7 (seven) is the natural number following 6 and preceding 8. It is the only prime number preceding a cube.

As an early prime number in the series of positive integers, the number seven has greatly symbolic associations in religion, mythology, s ...

against King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

and by asserting certain natural and legal rights, including a right of revolution. Its original purpose was to announce independence, and references to the text of the Declaration were few in the following years. Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

made it the centerpiece of his policies and his rhetoric, as in the Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is a speech that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln delivered during the American Civil War at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery, now known as Gettysburg National Cemetery, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on the ...

of 1863. Since then, it has become a well-known statement on human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

, particularly its second sentence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal

The quotation "all men are created equal" is part of the sentence in the U.S. Declaration of Independence – penned by Thomas Jefferson in 1776 during the beginning of the American Revolution – that reads "We hold these truths to be self-evide ...

, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

The declaration was made to guarantee equal rights for every person, and if it had been intended for only a certain section of people, Congress would have left it as "rights of Englishmen". Stephen Lucas called it "one of the best-known sentences in the English language", with historian Joseph Ellis

Joseph John-Michael Ellis III (born July 18, 1943) is an American historian whose work focuses on the lives and times of the founders of the United States of America. '' American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson'' won a National Boo ...

writing that the document contains "the most potent and consequential words in American history". The passage came to represent a moral standard to which the United States should strive. This view was notably promoted by Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

, who considered the Declaration to be the foundation of his political philosophy and argued that it is a statement of principles through which the United States Constitution should be interpreted.

The Declaration of Independence inspired many similar documents in other countries, the first being the 1789 ''Declaration of United Belgian States

The United Belgian States ( nl, Verenigde Nederlandse Staten or '; french: États-Belgiques-Unis; lat, Foederatum Belgium), also known as the United States of Belgium, was a short-lived confederal republic in the Southern Netherlands (modern-da ...

'' issued during the Brabant Revolution

The Brabant Revolution or Brabantine Revolution (french: Révolution brabançonne, nl, Brabantse Omwenteling), sometimes referred to as the Belgian Revolution of 1789–1790 in older writing, was an armed insurrection that occurred in the Aust ...

in the Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The pe ...

. It also served as the primary model for numerous declarations of independence in Europe and Latin America, as well as Africa ( Liberia) and Oceania (New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

) during the first half of the 19th century.

Background

By the time the Declaration of Independence was adopted in July 1776, the

By the time the Declaration of Independence was adopted in July 1776, the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

and Great Britain had been at war for more than a year. Relations had been deteriorating between the colonies and the mother country since 1763. Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

enacted a series of measures to increase revenue from the colonies, such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767. Parliament believed that these acts were a legitimate means of having the colonies pay their fair share of the costs to keep them in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

.

Many colonists, however, had developed a different perspective of the empire. The colonies were not directly represented in Parliament, and colonists argued that Parliament had no right to levy taxes upon them. This tax dispute was part of a larger divergence between British and American interpretations of the British Constitution

The constitution of the United Kingdom or British constitution comprises the written and unwritten arrangements that establish the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a political body. Unlike in most countries, no attempt ...

and the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies. The orthodox British view, dating from the Glorious Revolution of 1688, was that Parliament was the supreme authority throughout the empire, and anything that Parliament did was constitutional. In the colonies, however, the idea had developed that the British Constitution recognized certain fundamental rights

Fundamental rights are a group of rights that have been recognized by a high degree of protection from encroachment. These rights are specifically identified in a constitution, or have been found under due process of law. The United Nations' Susta ...

that no government could violate, including Parliament. After the Townshend Acts, some essayists questioned whether Parliament had any legitimate jurisdiction in the colonies. Anticipating the arrangement of the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

, by 1774 American writers such as Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, an ...

, James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

, and Thomas Jefferson argued that Parliament was the legislature of Great Britain only, and that the colonies, which had their own legislatures, were connected to the rest of the empire only through their allegiance to the Crown.

Congress convenes

In 1774, Parliament passed the

In 1774, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

, known as the Intolerable Acts in the colonies. This was intended to punish the colonists for the Gaspee Affair

The ''Gaspee'' Affair was a significant event in the lead-up to the American Revolution. HMS ''Gaspee'' was a British customs schooner that enforced the Navigation Acts in and around Newport, Rhode Island, in 1772. It ran aground in shallow ...

of 1772 and the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

of 1773. Many colonists considered the Coercive Acts to be in violation of the British Constitution and thus a threat to the liberties of all of British America; the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in September 1774 to coordinate a formal response. Congress organized a boycott of British goods and petitioned the king for repeal of the acts. These measures were unsuccessful, since King George and the Prime Minister, Lord North

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford (13 April 17325 August 1792), better known by his courtesy title Lord North, which he used from 1752 to 1790, was 12th Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1770 to 1782. He led Great Britain through most o ...

, were determined to enforce parliamentary supremacy over America. As the king wrote to North in November 1774, "blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent".

Most colonists still hoped for reconciliation with Great Britain, even after fighting began in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

at Lexington and Concord in April 1775.Middlekauff, ''Glorious Cause'', 318 The Second Continental Congress convened at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia in May 1775, and some delegates hoped for eventual independence, but no one yet advocated declaring it. Many colonists believed that Parliament no longer had sovereignty over them, but they were still loyal to King George, thinking he would intercede on their behalf. They were disabused of that notion in late 1775, when the king rejected Congress's second petition, issued a Proclamation of Rebellion, and announced before Parliament on October 26 that he was considering "friendly offers of foreign assistance" to suppress the rebellion.The text of the 1775 king's speech ionline

, published by the

American Memory

American Memory is an internet-based archive for public domain image resources, as well as audio, video, and archived Web content. Published by the Library of Congress, the archive launched on October 13, 1994, after $13 million was raised in ...

project A pro-American minority in Parliament warned that the government was driving the colonists toward independence.

Toward independence

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

's pamphlet ''Common Sense

''Common Sense'' is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political arg ...

'' was published in January 1776, when the king clearly was not inclined to act as a conciliator. Paine, recently arrived in the colonies from England, argued in favor of colonial independence, advocating republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

as an alternative to monarchy and hereditary rule. ''Common Sense'' made a persuasive, impassioned case for independence, which had not been given serious consideration in the colonies. Paine linked independence with Protestant beliefs, as a means to present a distinctly American political identity, and he initiated open debate on a topic few had dared to discuss. Public support for separation from Great Britain steadily increased after the publication of ''Common Sense''.

Some colonists still hoped for reconciliation, but public support for independence further strengthened in early 1776. In February 1776, colonists learned of Parliament's passage of the Prohibitory Act, which established a blockade of American ports and declared American ships to be enemy vessels.

Some colonists still hoped for reconciliation, but public support for independence further strengthened in early 1776. In February 1776, colonists learned of Parliament's passage of the Prohibitory Act, which established a blockade of American ports and declared American ships to be enemy vessels. John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

, a strong supporter of independence, believed that Parliament had effectively declared American independence before Congress had been able to. Adams labeled the Prohibitory Act the "Act of Independency", calling it "a compleat Dismemberment of the British Empire". Support for declaring independence grew even more when it was confirmed that King George had hired German mercenaries to use against his American subjects.

Despite this growing popular support for independence, Congress lacked the clear authority to declare it. Delegates had been elected to Congress by 13 different governments, which included extralegal conventions, ad hoc committees, and elected assemblies, and they were bound by the instructions given to them. Regardless of their personal opinions, delegates could not vote to declare independence unless their instructions permitted such an action. Several colonies, in fact, expressly prohibited their delegates from taking any steps toward separation from Great Britain, while other delegations had instructions that were ambiguous on the issue; consequently, advocates of independence sought to have the Congressional instructions revised. For Congress to declare independence, a majority of delegations would need authorization to vote for it, and at least one colonial government would need to specifically instruct its delegation to propose a declaration of independence in Congress. Between April and July 1776, a "complex political war" was waged to bring this about.

Revising instructions

In the campaign to revise Congressional instructions, many Americans formally expressed their support for separation from Great Britain in what were effectively state and local declarations of independence. Historian Pauline Maier identifies more than ninety such declarations that were issued throughout the Thirteen Colonies from April to July 1776. These "declarations" took a variety of forms. Some were formal written instructions for Congressional delegations, such as theHalifax Resolves

The Halifax Resolves was a name later given to the resolution adopted by the North Carolina Provincial Congress on April 12, 1776. The adoption of the resolution was the first official action in the American Colonies calling for independence from ...

of April 12, with which North Carolina became the first colony to explicitly authorize its delegates to vote for independence. Others were legislative acts that officially ended British rule in individual colonies, such as the Rhode Island legislature renouncing its allegiance to Great Britain on May 4—the first colony to do so. Many "declarations" were resolutions adopted at town or county meetings that offered support for independence. A few came in the form of jury instructions, such as the statement issued on April 23, 1776, by Chief Justice William Henry Drayton

William Henry Drayton (September 1742 – September 3, 1779) was an American Founding Father, planter, and lawyer from Charleston, South Carolina. He served as a delegate for South Carolina to the Continental Congress in 1778-79 and signed t ...

of South Carolina: "the law of the land authorizes me to declare ... that ''George'' the Third, King of ''Great Britain'' ... has no authority over us, and we owe no obedience to him." Most of these declarations are now obscure, having been overshadowed by the resolution for independence, approved by Congress on July 2, and the declaration of independence, approved and printed on July 4 and signed in August. The modern scholarly consensus is that the best-known and earliest of the local declarations is most likely inauthentic, the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is a text published in 1819 with the now disputed claim that it was the first declaration of independence made in the Thirteen Colonies during the American Revolution. It was supposedly signed on May 20 ...

, allegedly adopted in May 1775 (a full year before other local declarations).

Some colonies held back from endorsing independence. Resistance was centered in the middle colonies

The Middle Colonies were a subset of the Thirteen Colonies in British America, located between the New England Colonies and the Southern Colonies. Along with the Chesapeake Colonies, this area now roughly makes up the Mid-Atlantic states.

Mu ...

of New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Advocates of independence saw Pennsylvania as the key; if that colony could be converted to the pro-independence cause, it was believed that the others would follow. On May 1, however, opponents of independence retained control of the Pennsylvania Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvania ...

in a special election that had focused on the question of independence. In response, Congress passed a resolution on May 10 which had been promoted by John Adams and Richard Henry Lee

Richard Henry Lee (January 20, 1732June 19, 1794) was an American statesman and Founding Father from Virginia, best known for the June 1776 Lee Resolution, the motion in the Second Continental Congress calling for the colonies' independence f ...

, calling on colonies without a "government sufficient to the exigencies of their affairs" to adopt new governments. The resolution passed unanimously, and was even supported by Pennsylvania's John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

, the leader of the anti-independence faction in Congress, who believed that it did not apply to his colony.

May 15 preamble

As was the custom, Congress appointed a committee to draft a preamble to explain the purpose of the resolution. John Adams wrote the preamble, which stated that because King George had rejected reconciliation and was hiring foreign mercenaries to use against the colonies, "it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed". Adams's preamble was meant to encourage the overthrow of the governments of Pennsylvania and Maryland, which were still under proprietary governance. Congress passed the preamble on May 15 after several days of debate, but four of the middle colonies voted against it, and the Maryland delegation walked out in protest. Adams regarded his May 15 preamble effectively as an American declaration of independence, although a formal declaration would still have to be made.Lee's resolution

On the same day that Congress passed Adams's radical preamble, the Virginia Convention set the stage for a formal Congressional declaration of independence. On May 15, the Convention instructed Virginia's congressional delegation "to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain". In accordance with those instructions,Richard Henry Lee

Richard Henry Lee (January 20, 1732June 19, 1794) was an American statesman and Founding Father from Virginia, best known for the June 1776 Lee Resolution, the motion in the Second Continental Congress calling for the colonies' independence f ...

of Virginia presented a three-part resolution to Congress on June 7. The motion was seconded by John Adams, calling on Congress to declare independence, form foreign alliances, and prepare a plan of colonial confederation. The part of the resolution relating to declaring independence read: "Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."Boyd, ''Evolution'', 19.

Lee's resolution met with resistance in the ensuing debate. Opponents of the resolution conceded that reconciliation was unlikely with Great Britain, while arguing that declaring independence was premature, and that securing foreign aid should take priority. Advocates of the resolution countered that foreign governments would not intervene in an internal British struggle, and so a formal declaration of independence was needed before foreign aid was possible. All Congress needed to do, they insisted, was to "declare a fact which already exists". Delegates from Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, Maryland, and New York were still not yet authorized to vote for independence, however, and some of them threatened to leave Congress if the resolution were adopted. Congress, therefore, voted on June 10 to postpone further discussion of Lee's resolution for three weeks. Until then, Congress decided that a committee should prepare a document announcing and explaining independence in case Lee's resolution was approved when it was brought up again in July.

Final push

Support for a Congressional declaration of independence was consolidated in the final weeks of June 1776. On June 14, the Connecticut Assembly instructed its delegates to propose independence and, the following day, the legislatures of New Hampshire and Delaware authorized their delegates to declare independence. In Pennsylvania, political struggles ended with the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and a new Conference of Committees under

Support for a Congressional declaration of independence was consolidated in the final weeks of June 1776. On June 14, the Connecticut Assembly instructed its delegates to propose independence and, the following day, the legislatures of New Hampshire and Delaware authorized their delegates to declare independence. In Pennsylvania, political struggles ended with the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and a new Conference of Committees under Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean (March 19, 1734June 24, 1817) was an American lawyer, politician, and Founding Father. During the American Revolution, he was a Delaware delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, the United ...

authorized Pennsylvania's delegates to declare independence on June 18. The Provincial Congress of New Jersey had been governing the province since January 1776; they resolved on June 15 that Royal Governor William Franklin

William Franklin (22 February 1730 – 17 November 1813) was an American-born attorney, soldier, politician, and colonial administrator. He was the acknowledged illegitimate son of Benjamin Franklin. William Franklin was the last colonial G ...

was "an enemy to the liberties of this country" and had him arrested. On June 21, they chose new delegates to Congress and empowered them to join in a declaration of independence.

Only Maryland and New York had yet to authorize independence toward the end of June. Previously, Maryland's delegates had walked out when the Continental Congress adopted Adams's radical May 15 preamble, and had sent to the Annapolis Convention for instructions. On May 20, the Annapolis Convention rejected Adams's preamble, instructing its delegates to remain against independence. But Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of t ...

went to Maryland and, thanks to local resolutions in favor of independence, was able to get the Annapolis Convention to change its mind on June 28. Only the New York delegates were unable to get revised instructions. When Congress had been considering the resolution of independence on June 8, the New York Provincial Congress

The New York Provincial Congress (1775–1777) was a revolutionary provisional government formed by colonists in 1775, during the American Revolution, as a pro-American alternative to the more conservative New York General Assembly, and as a repla ...

told the delegates to wait. But on June 30, the Provincial Congress evacuated New York as British forces approached, and would not convene again until July 10. This meant that New York's delegates would not be authorized to declare independence until after Congress had made its decision.

Draft and adoption

Political maneuvering was setting the stage for an official declaration of independence even while a document was being written to explain the decision. On June 11, 1776, Congress appointed a "Committee of Five

''

The Committee of Five of the Second Continental Congress was a group of five members who drafted and presented to the full Congress in Pennsylvania State House what would become the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Thi ...

" to draft a declaration, consisting of John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

of New York, and Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an American statesman, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign four of the great state papers of the United States related to the founding: the Con ...

of Connecticut. The committee took no minutes, so there is some uncertainty about how the drafting process proceeded; contradictory accounts were written many years later by Jefferson and Adams, too many years to be regarded as entirely reliable—although their accounts are frequently cited. What is certain is that the committee discussed the general outline which the document should follow and decided that Jefferson would write the first draft. The committee in general, and Jefferson in particular, thought that Adams should write the document, but Adams persuaded them to choose Jefferson and promised to consult with him personally. Considering Congress's busy schedule, Jefferson probably had limited time for writing over the next 17 days, and he likely wrote the draft quickly. Examination of the text of the early Declaration drafts reflects Jefferson's reference to the ideas and writings of John Locke and Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense. He then consulted the other members of the Committee of Five who offered minor changes, and then produced another copy incorporating these alterations. The committee presented this copy to the Congress on June 28, 1776. The title of the document was "A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled."

Congress ordered that the draft "lie on the table" and then methodically edited Jefferson's primary document for the next two days, shortening it by a fourth, removing unnecessary wording, and improving sentence structure. They removed Jefferson's assertion that King George III had forced

Congress ordered that the draft "lie on the table" and then methodically edited Jefferson's primary document for the next two days, shortening it by a fourth, removing unnecessary wording, and improving sentence structure. They removed Jefferson's assertion that King George III had forced slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

onto the colonies, Shipler, David K., The Paragraph Missing From The Declaration of Independence

'', The Shipler Report, July 4, 2020 in order to moderate the document and appease those in South Carolina and Georgia, both states which had significant involvement in the

slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Jefferson later wrote in his autobiography that Northern states were also supportive towards the clauses removal, "for though their people had very few slaves themselves, yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others." Jefferson wrote that Congress had "mangled" his draft version, but the Declaration that was finally produced was "the majestic document that inspired both contemporaries and posterity", in the words of his biographer John Ferling. John E. Ferling, ''Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution'', Oxford University Press. . , pp. 131–37

Congress tabled the draft of the declaration on Monday, July 1 and resolved itself into a committee of the whole

A committee of the whole is a meeting of a legislative or deliberative assembly using procedural rules that are based on those of a committee, except that in this case the committee includes all members of the assembly. As with other (standing) c ...

, with Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

of Virginia presiding, and they resumed debate on Lee's resolution of independence. John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

made one last effort to delay the decision, arguing that Congress should not declare independence without first securing a foreign alliance and finalizing the Articles of Confederation. John Adams gave a speech in reply to Dickinson, restating the case for an immediate declaration.

A vote was taken after a long day of speeches, each colony casting a single vote, as always. The delegation for each colony numbered from two to seven members, and each delegation voted among themselves to determine the colony's vote. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against declaring independence. The New York delegation abstained, lacking permission to vote for independence. Delaware cast no vote because the delegation was split between Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean (March 19, 1734June 24, 1817) was an American lawyer, politician, and Founding Father. During the American Revolution, he was a Delaware delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, the United ...

, who voted yes, and George Read, who voted no. The remaining nine delegations voted in favor of independence, which meant that the resolution had been approved by the committee of the whole. The next step was for the resolution to be voted upon by Congress itself. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina was opposed to Lee's resolution but desirous of unanimity, and he moved that the vote be postponed until the following day.

On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of

On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of Caesar Rodney

Caesar Rodney (October 7, 1728 – June 26, 1784) was an American Founding Father, lawyer, and politician from St. Jones Neck in Dover Hundred, Kent County, Delaware. He was an officer of the Delaware militia during the French and Indian War a ...

, who voted for independence. The New York delegation abstained once again since they were still not authorized to vote for independence, although they were allowed to do so a week later by the New York Provincial Congress

The New York Provincial Congress (1775–1777) was a revolutionary provisional government formed by colonists in 1775, during the American Revolution, as a pro-American alternative to the more conservative New York General Assembly, and as a repla ...

. The resolution of independence was adopted with twelve affirmative votes and one abstention, and the colonies formally severed political ties with Great Britain. John Adams wrote to his wife on the following day and predicted that July 2 would become a great American holiday He thought that the vote for independence would be commemorated; he did not foresee that Americans would instead celebrate Independence Day on the date when the announcement of that act was finalized.

I am apt to believe that ndependence Daywill be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.Congress next turned its attention to the committee's draft of the declaration. They made a few changes in wording during several days of debate and deleted nearly a fourth of the text. The wording of the Declaration of Independence was approved on July 4, 1776, and sent to the printer for publication.

There is a distinct change in wording from this original broadside printing of the Declaration and the final official engrossed copy. The word "unanimous" was inserted as a result of a Congressional resolution passed on July 19, 1776: "Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Historian George Athan Billias says: "Independence amounted to a new status of interdependence: the United States was now a sovereign nation entitled to the privileges and responsibilities that came with that status. America thus became a member of the international community, which meant becoming a maker of treaties and alliances, a military ally in diplomacy, and a partner in foreign trade on a more equal basis."

There is a distinct change in wording from this original broadside printing of the Declaration and the final official engrossed copy. The word "unanimous" was inserted as a result of a Congressional resolution passed on July 19, 1776: "Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Historian George Athan Billias says: "Independence amounted to a new status of interdependence: the United States was now a sovereign nation entitled to the privileges and responsibilities that came with that status. America thus became a member of the international community, which meant becoming a maker of treaties and alliances, a military ally in diplomacy, and a partner in foreign trade on a more equal basis."

Annotated text of the engrossed declaration

The declaration is not divided into formal sections; but it is often discussed as consisting of five parts: ''introduction'', ''preamble'', ''indictment'' of King George III, ''denunciation'' of the British people, and ''conclusion''.Influences and legal status

Historians have often sought to identify the sources that most influenced the words and

Historians have often sought to identify the sources that most influenced the words and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

of the Declaration of Independence. By Jefferson's own admission, the Declaration contained no original ideas, but was instead a statement of sentiments widely shared by supporters of the American Revolution. As he explained in 1825:

Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.Jefferson's most immediate sources were two documents written in June 1776: his own draft of the preamble of the

Constitution of Virginia

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the document that defines and limits the powers of the state government and the basic rights of the citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Like all other state constitutions, it is supreme ...

, and George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of the three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including ...

's draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted in 1776 to proclaim the inherent rights of men, including the right to reform or abolish "inadequate" government. It influenced a number of later documents, including the United States Declaratio ...

. Ideas and phrases from both of these documents appear in the Declaration of Independence. Mason's opening was:

Section 1. That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.Mason was, in turn, directly influenced by the 1689 English Declaration of Rights, which formally ended the reign of King James II. During the American Revolution, Jefferson and other Americans looked to the English Declaration of Rights as a model of how to end the reign of an unjust king. The Scottish

Declaration of Arbroath

The Declaration of Arbroath ( la, Declaratio Arbroathis; sco, Declaration o Aiberbrothock; gd, Tiomnadh Bhruis) is the name usually given to a letter, dated 6 April 1320 at Arbroath, written by Scottish barons and addressed to Pope John ...

(1320) and the Dutch Act of Abjuration

The Act of Abjuration ( nl, Plakkaat van Verlatinghe; es, Acta de Abjuración, lit=placard of abjuration) is the declaration of independence by many of the provinces of the Netherlands from the allegiance to Philip II of Spain, during the Dut ...

(1581) have also been offered as models for Jefferson's Declaration, but these models are now accepted by few scholars. Maier found no evidence that the Dutch Act of Abjuration served as a model for the Declaration, and considers the argument "unpersuasive". Armitage discounts the influence of the Scottish and Dutch acts, and writes that neither was called "declarations of independence" until fairly recently. Stephen E. Lucas argued in favor of the influence of the Dutch act.

Jefferson wrote that a number of authors exerted a general influence on the words of the Declaration. English political theorist John Locke is usually cited as one of the primary influences, a man whom Jefferson called one of "the three greatest men that have ever lived". In 1922, historian Carl L. Becker wrote, "Most Americans had absorbed Locke's works as a kind of political gospel; and the Declaration, in its form, in its phraseology, follows closely certain sentences in Locke's second treatise on government." The extent of Locke's influence on the American Revolution has been questioned by some subsequent scholars, however. Historian Ray Forrest Harvey argued in 1937 for the dominant influence of Swiss jurist Jean Jacques Burlamaqui, declaring that Jefferson and Locke were at "two opposite poles" in their political philosophy, as evidenced by Jefferson's use in the Declaration of Independence of the phrase "pursuit of happiness" instead of "property". Other scholars emphasized the influence of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

rather than Locke's classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, econo ...

. Historian Garry Wills argued that Jefferson was influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment, particularly Francis Hutcheson, rather than Locke, an interpretation that has been strongly criticized.

Legal historian John Phillip Reid has written that the emphasis on the political philosophy of the Declaration has been misplaced. The Declaration is not a philosophical tract about natural rights, argues Reid, but is instead a legal document—an indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of a ...

against King George for violating the constitutional rights of the colonists. As such, it follows the process of the 1550 '' Magdeburg Confession'', which legitimized resistance against Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) ...

in a multi-step legal formula now known as the doctrine of the lesser magistrate

The doctrine of the lesser magistrate is a concept in Protestant thought. A lesser magistrate is a ruler such as a prince who is under a greater ruler such as an emperor. The doctrine of the lesser magistrate is a legal system explaining the exact ...

. Historian David Armitage has argued that the Declaration was strongly influenced by de Vattel's ''The Law of Nations

''The Law of Nations: Or, Principles of the Law of Nature Applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns''french: Le Droit des gens : Principes de la loi naturelle, appliqués à la conduite et aux affaires des Nations et des Souvera ...

'', the dominant international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

treatise of the period, and a book that Benjamin Franklin said was "continually in the hands of the members of our Congress". Armitage writes, "Vattel made independence fundamental to his definition of statehood"; therefore, the primary purpose of the Declaration was "to express the international legal sovereignty of the United States". If the United States were to have any hope of being recognized by the European powers, the American revolutionaries first had to make it clear that they were no longer dependent on Great Britain. The Declaration of Independence does not have the force of law domestically, but nevertheless it may help to provide historical and legal clarity about the Constitution and other laws.

Signing

The Declaration became official when Congress recorded its vote adopting the document on July 4; it was transposed on paper and signed by

The Declaration became official when Congress recorded its vote adopting the document on July 4; it was transposed on paper and signed by John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of t ...

, President of the Congress, on that day. Signatures of the other delegates were not needed to further authenticate it.The U.S. State Department (1911), ''The Declaration of Independence, 1776'', pp. 10, 11. The signatures of fifty-six delegates are affixed to the Declaration, though the exact date when each person signed became debatable. Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams all wrote that the Declaration was signed by Congress on July 4. But in 1796, signer Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean (March 19, 1734June 24, 1817) was an American lawyer, politician, and Founding Father. During the American Revolution, he was a Delaware delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, the United ...

disputed that, because some signers were not then present, including several who were not even elected to Congress until after that date. Historians have generally accepted McKean's version of events. History particularly shows most delegates signed on August 2, 1776, and those who were not then present added their names later.

In an 1811 letter to Adams, Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (April 19, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, educa ...

recounted the signing in stark fashion, describing it as a scene of "pensive and awful silence". Rush said the delegates were called up, one after another, and then filed forward somberly to subscribe what each thought was their ensuing death warrant. He related that the "gloom of the morning" was briefly interrupted when the rotund Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

of Virginia said to a diminutive Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, at the signing table, "I shall have a great advantage over you, Mr. Gerry, when we are all hung for what we are now doing. From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes and be with the Angels, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in the air an hour or two before you are dead." According to Rush, Harrison’s remark "procured a transient smile, but it was soon succeeded by the Solemnity with which the whole business was conducted.”

The signatories include then future presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, though the most legendary signature is John Hancock’s. His large, flamboyant signature became iconic, and the term ''John Hancock'' emerged in the United States as a metaphor of "signature". A commonly circulated but apocryphal account claims that, after Hancock signed, the delegate from Massachusetts commented, "The British ministry can read that name without spectacles." Another report indicates that Hancock proudly declared, "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

A legend emerged years later about the signing of the Declaration, after the document had become an important national symbol. John Hancock is supposed to have said that Congress, having signed the Declaration, must now "all hang together", and Benjamin Franklin replied: "Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." That quotation first appeared in print in an 1837 London humor magazine.

The Syng inkstand used at the signing was also used at the signing of the United States Constitution in 1787.

The signatories include then future presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, though the most legendary signature is John Hancock’s. His large, flamboyant signature became iconic, and the term ''John Hancock'' emerged in the United States as a metaphor of "signature". A commonly circulated but apocryphal account claims that, after Hancock signed, the delegate from Massachusetts commented, "The British ministry can read that name without spectacles." Another report indicates that Hancock proudly declared, "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

A legend emerged years later about the signing of the Declaration, after the document had become an important national symbol. John Hancock is supposed to have said that Congress, having signed the Declaration, must now "all hang together", and Benjamin Franklin replied: "Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." That quotation first appeared in print in an 1837 London humor magazine.

The Syng inkstand used at the signing was also used at the signing of the United States Constitution in 1787.

Publication and reaction

After Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration on July 4, a handwritten copy was sent a few blocks away to the printing shop of John Dunlap. Through the night, Dunlap printed about 200 broadsides for distribution. The source copy used for this printing has been lost and may have been a copy in Thomas Jefferson's hand.Boyd (1976), ''The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original'', p. 438. It was read to audiences and reprinted in newspapers throughout the 13 states. The first formal public readings of the document took place on July 8, in Philadelphia (by John Nixon in the yard of Independence Hall),Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. It was the capital of the United States from November 1 to December 24, 1784.Easton, Pennsylvania

Easton is a city in, and the county seat of, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, United States. The city's population was 28,127 as of the 2020 census. Easton is located at the confluence of the Lehigh River, a river that joins the Delaware R ...

; the first newspaper to publish it was '' The Pennsylvania Evening Post'' on July 6. A German translation of the Declaration was published in Philadelphia by July 9.

President of Congress John Hancock sent a broadside to General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, instructing him to have it proclaimed "at the Head of the Army in the way you shall think it most proper". Washington had the Declaration read to his troops in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

on July 9, with thousands of British troops on ships in the harbor. Washington and Congress hoped that the Declaration would inspire the soldiers, and encourage others to join the army. After hearing the Declaration, crowds in many cities tore down and destroyed signs or statues representing royal authority. An equestrian statue of King George in New York City was pulled down and the lead used to make musket balls.

One of the first readings of the Declaration by the British is believed to have taken place at the Rose and Crown Tavern on

One of the first readings of the Declaration by the British is believed to have taken place at the Rose and Crown Tavern on Staten Island, New York

Staten Island ( ) is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull and ...

in the presence of General Howe