Type II supernova on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Type II supernova (plural: ''supernovae'' or ''supernovas'') results from the rapid collapse and violent explosion of a massive

A Type II supernova (plural: ''supernovae'' or ''supernovas'') results from the rapid collapse and violent explosion of a massive

A Type II supernova (plural: ''supernovae'' or ''supernovas'') results from the rapid collapse and violent explosion of a massive

A Type II supernova (plural: ''supernovae'' or ''supernovas'') results from the rapid collapse and violent explosion of a massive star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by its gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night, but their immense distances from Earth ma ...

. A star must have at least 8 times, but no more than 40 to 50 times, the mass of the Sun

The solar mass () is a standard unit of mass in astronomy, equal to approximately . It is often used to indicate the masses of other stars, as well as stellar clusters, nebulae, galaxies and black holes. It is approximately equal to the mass of ...

() to undergo this type of explosion. Type II supernovae are distinguished from other types of supernovae by the presence of hydrogen in their spectra. They are usually observed in the spiral arm

Spiral galaxies form a class of galaxy originally described by Edwin Hubble in his 1936 work ''The Realm of the Nebulae''galaxies and in

Stars far more massive than the sun evolve in complex ways. In the core of the star, hydrogen is fused into helium, releasing thermal energy that heats the star's core and provides outward pressure that supports the star's layers against collapse - a situation known as stellar or hydrostatic equilibrium. The helium produced in the core accumulates there. Temperatures in the core are not yet high enough to cause it to fuse. Eventually, as the hydrogen at the core is exhausted, fusion starts to slow down, and gravity causes the core to contract. This contraction raises the temperature high enough to allow a shorter phase of helium fusion, which produces carbon and oxygen, and accounts for less than 10% of the star's total lifetime.

In stars of less than eight solar masses, the carbon produced by helium fusion does not fuse, and the star gradually cools to become a

Stars far more massive than the sun evolve in complex ways. In the core of the star, hydrogen is fused into helium, releasing thermal energy that heats the star's core and provides outward pressure that supports the star's layers against collapse - a situation known as stellar or hydrostatic equilibrium. The helium produced in the core accumulates there. Temperatures in the core are not yet high enough to cause it to fuse. Eventually, as the hydrogen at the core is exhausted, fusion starts to slow down, and gravity causes the core to contract. This contraction raises the temperature high enough to allow a shorter phase of helium fusion, which produces carbon and oxygen, and accounts for less than 10% of the star's total lifetime.

In stars of less than eight solar masses, the carbon produced by helium fusion does not fuse, and the star gradually cools to become a

When the progenitor star is below about – depending on the strength of the explosion and the amount of material that falls back – the degenerate remnant of a core collapse is a neutron star. Above this mass, the remnant collapses to form a

When the progenitor star is below about – depending on the strength of the explosion and the amount of material that falls back – the degenerate remnant of a core collapse is a neutron star. Above this mass, the remnant collapses to form a

When the

When the

H II region

An H II region or HII region is a region of interstellar atomic hydrogen that is ionized. It is typically in a molecular cloud of partially ionized gas in which star formation has recently taken place, with a size ranging from one to hundred ...

s, but not in elliptical galaxies

An elliptical galaxy is a type of galaxy with an approximately ellipsoidal shape and a smooth, nearly featureless image. They are one of the four main classes of galaxy described by Edwin Hubble in his Hubble sequence and 1936 work ''The Real ...

; those are generally composed of older, low-mass stars, with few of the young, very massive stars necessary to cause a supernova.

Stars generate energy by the nuclear fusion of elements. Unlike the Sun, massive stars possess the mass needed to fuse elements that have an atomic mass

The atomic mass (''m''a or ''m'') is the mass of an atom. Although the SI unit of mass is the kilogram (symbol: kg), atomic mass is often expressed in the non-SI unit dalton (symbol: Da) – equivalently, unified atomic mass unit (u). 1&nbs ...

greater than hydrogen and helium, albeit at increasingly higher temperatures and pressures, causing correspondingly shorter stellar life spans. The degeneracy pressure of electrons and the energy generated by these fusion reactions are sufficient to counter the force of gravity and prevent the star from collapsing, maintaining stellar equilibrium. The star fuses increasingly higher mass elements, starting with hydrogen and then helium, progressing up through the periodic table until a core of iron and nickel is produced. Fusion of iron or nickel produces no net energy output, so no further fusion can take place, leaving the nickel–iron core inert. Due to the lack of energy output creating outward thermal pressure, the core contracts due to gravity until the overlying weight of the star can be supported largely by electron degeneracy pressure.

When the compacted mass of the inert core exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit

The Chandrasekhar limit () is the maximum mass of a stable white dwarf star. The currently accepted value of the Chandrasekhar limit is about ().

White dwarfs resist gravitational collapse primarily through electron degeneracy pressure, compar ...

of about , electron degeneracy is no longer sufficient to counter the gravitational compression. A cataclysmic implosion of the core takes place within seconds. Without the support of the now-imploded inner core, the outer core collapses inwards under gravity and reaches a velocity of up to 23% of the speed of light, and the sudden compression increases the temperature of the inner core to up to 100 billion kelvins. Neutrons and neutrinos are formed via reversed beta-decay, releasing about 1046 joules (100 foe) in a ten-second burst. The collapse of the inner core is halted by neutron degeneracy

Degenerate matter is a highly dense state of fermionic matter in which the Pauli exclusion principle exerts significant pressure in addition to, or in lieu of, thermal pressure. The description applies to matter composed of electrons, protons, ne ...

, causing the implosion to rebound and bounce outward. The energy of this expanding shock wave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a med ...

is sufficient to disrupt the overlying stellar material and accelerate it to escape velocity, forming a supernova explosion. The shock wave and extremely high temperature and pressure rapidly dissipate but are present for long enough to allow for a brief period during which the

production of elements heavier than iron occurs. Depending on initial mass of the star, the remnants of the core form a neutron star or a black hole

A black hole is a region of spacetime where gravity is so strong that nothing, including light or other electromagnetic waves, has enough energy to escape it. The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass can defo ...

. Because of the underlying mechanism, the resulting supernova is also described as a core-collapse supernova.

There exist several categories of Type II supernova explosions, which are categorized based on the resulting light curve

In astronomy, a light curve is a graph of light intensity of a celestial object or region as a function of time, typically with the magnitude of light received on the y axis and with time on the x axis. The light is usually in a particular freq ...

—a graph of luminosity versus time—following the explosion. Type II-L supernovae show a steady ( linear) decline of the light curve following the explosion, whereas Type II-P display a period of slower decline (a plateau) in their light curve followed by a normal decay. Type Ib and Ic supernovae are a type of core-collapse supernova for a massive star that has shed its outer envelope of hydrogen and (for Type Ic) helium. As a result, they appear to be lacking in these elements.

Formation

white dwarf

A white dwarf is a stellar core remnant composed mostly of electron-degenerate matter. A white dwarf is very dense: its mass is comparable to the Sun's, while its volume is comparable to the Earth's. A white dwarf's faint luminosity comes f ...

. If they accumulate more mass from another star, or some other source, they may become Type Ia supernovae. But a much larger star is massive enough to continue fusion beyond this point.

The cores of these massive stars directly create temperatures and pressures needed to cause the carbon in the core to begin to fuse when the star contracts at the end of the helium-burning stage. The core gradually becomes layered like an onion, as progressively heavier atomic nuclei build up at the center, with an outermost layer of hydrogen gas, surrounding a layer of hydrogen fusing into helium, surrounding a layer of helium fusing into carbon via the triple-alpha process, surrounding layers that fuse to progressively heavier elements. As a star this massive evolves, it undergoes repeated stages where fusion in the core stops, and the core collapses until the pressure and temperature are sufficient to begin the next stage of fusion, reigniting to halt collapse.

:

Core collapse

The factor limiting this process is the amount of energy that is released through fusion, which is dependent on thebinding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

that holds together these atomic nuclei. Each additional step produces progressively heavier nuclei, which release progressively less energy when fusing. In addition, from carbon-burning

The carbon-burning process or carbon fusion is a set of nuclear fusion reactions that take place in the cores of massive stars (at least 8 \beginM_\odot\end at birth) that combines carbon into other elements. It requires high temperatures (> 5&t ...

onwards, energy loss via neutrino production becomes significant, leading to a higher rate of reaction than would otherwise take place. This continues until nickel-56 is produced, which decays radioactively into cobalt-56

Naturally occurring cobalt (Co) consists of a single stable isotope, Co. Twenty-eight radioisotopes have been characterized; the most stable are Co with a half-life of 5.2714 years, Co (271.8 days), Co (77.27 days), and Co (70.86 days). All other ...

and then iron-56

Iron-56 (56Fe) is the most common isotope of iron. About 91.754% of all iron is iron-56.

Of all nuclides, iron-56 has the lowest mass per nucleon. With 8.8 MeV binding energy per nucleon, iron-56 is one of the most tightly bound nuclei.

...

over the course of a few months. As iron and nickel have the highest binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

per nucleon of all the elements, energy cannot be produced at the core by fusion, and a nickel-iron core grows. This core is under huge gravitational pressure. As there is no fusion to further raise the star's temperature to support it against collapse, it is supported only by degeneracy pressure of electrons. In this state, matter is so dense that further compaction would require electrons to occupy the same energy states. However, this is forbidden for identical fermion

In particle physics, a fermion is a particle that follows Fermi–Dirac statistics. Generally, it has a half-odd-integer spin: spin , spin , etc. In addition, these particles obey the Pauli exclusion principle. Fermions include all quarks and ...

particles, such as the electron – a phenomenon called the Pauli exclusion principle

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli exclusion principle states that two or more identical particles with half-integer spins (i.e. fermions) cannot occupy the same quantum state within a quantum system simultaneously. This principle was formula ...

.

When the core's mass exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit

The Chandrasekhar limit () is the maximum mass of a stable white dwarf star. The currently accepted value of the Chandrasekhar limit is about ().

White dwarfs resist gravitational collapse primarily through electron degeneracy pressure, compar ...

of about , degeneracy pressure can no longer support it, and catastrophic collapse ensues. The outer part of the core reaches velocities of up to (23% of the speed of light) as it collapses toward the center of the star.

The rapidly shrinking core heats up, producing high-energy gamma rays

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically sh ...

that decompose iron nuclei into helium nuclei and free neutrons via photodisintegration

Photodisintegration (also called phototransmutation, or a photonuclear reaction) is a nuclear process in which an atomic nucleus absorbs a high-energy gamma ray, enters an excited state, and immediately decays by emitting a subatomic particle. The ...

. As the core's density increases, it becomes energetically favorable for electrons and protons to merge via inverse beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus, transforming the original nuclide to an isobar of that nuclide. For e ...

, producing neutrons and elementary particles called neutrinos. Because neutrinos rarely interact with normal matter, they can escape from the core, carrying away energy and further accelerating the collapse, which proceeds over a timescale of milliseconds. As the core detaches from the outer layers of the star, some of these neutrinos are absorbed by the star's outer layers, beginning the supernova explosion.

For Type II supernovae, the collapse is eventually halted by short-range repulsive neutron-neutron interactions, mediated by the strong force

The strong interaction or strong force is a fundamental interaction that confines quarks into proton, neutron, and other hadron particles. The strong interaction also binds neutrons and protons to create atomic nuclei, where it is called the ...

, as well as by degeneracy pressure of neutrons, at a density comparable to that of an atomic nucleus. When the collapse stops, the infalling matter rebounds, producing a shock wave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a med ...

that propagates outward. The energy from this shock dissociates heavy elements within the core. This reduces the energy of the shock, which can stall the explosion within the outer core.

The core collapse phase is so dense and energetic that only neutrinos are able to escape. As the protons and electrons combine to form neutrons by means of electron capture, an electron neutrino is produced. In a typical Type II supernova, the newly formed neutron core has an initial temperature of about 100 billion kelvins, 104 times the temperature of the Sun's core. Much of this thermal energy must be shed for a stable neutron star to form, otherwise the neutrons would "boil away". This is accomplished by a further release of neutrinos. These 'thermal' neutrinos form as neutrino-antineutrino pairs of all flavors, and total several times the number of electron-capture neutrinos. The two neutrino production mechanisms convert the gravitational potential energy of the collapse into a ten-second neutrino burst, releasing about 1046 joules (100 foe).

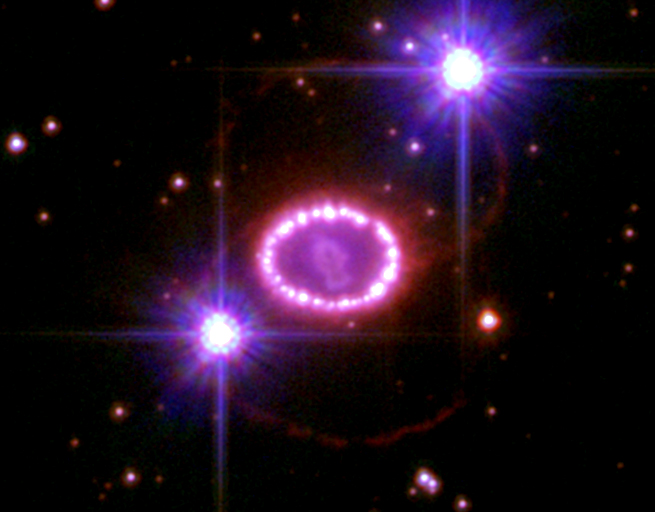

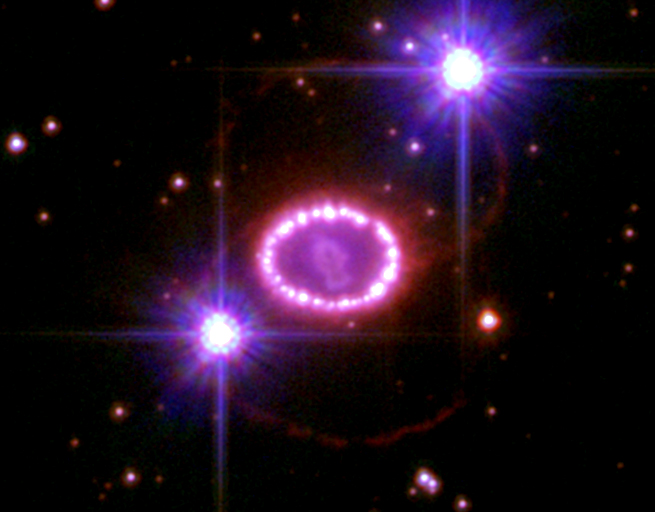

Through a process that is not clearly understood, about 1%, or 1044 joules (1 foe), of the energy released (in the form of neutrinos) is reabsorbed by the stalled shock, producing the supernova explosion. Neutrinos generated by a supernova were observed in the case of Supernova 1987A

SN 1987A was a type II supernova in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. It occurred approximately from Earth and was the closest observed supernova since Kepler's Supernova. 1987A's light reached Earth on Febr ...

, leading astrophysicists to conclude that the core collapse picture is basically correct. The water-based Kamiokande II and IMB instruments detected antineutrinos of thermal origin, while the gallium

Gallium is a chemical element with the symbol Ga and atomic number 31. Discovered by French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran in 1875, Gallium is in group 13 of the periodic table and is similar to the other metals of the group (alumini ...

-71-based Baksan instrument detected neutrinos (lepton number

In particle physics, lepton number (historically also called lepton charge)

is a conserved quantum number representing the difference between the number of leptons and the number of antileptons in an elementary particle reaction.

Lepton number ...

= 1) of either thermal or electron-capture origin.

black hole

A black hole is a region of spacetime where gravity is so strong that nothing, including light or other electromagnetic waves, has enough energy to escape it. The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass can defo ...

. The theoretical limiting mass for this type of core collapse scenario is about . Above that mass, a star is believed to collapse directly into a black hole without forming a supernova explosion,

although uncertainties in models of supernova collapse make calculation of these limits uncertain.

Theoretical models

The Standard Model of particle physics is a theory which describes three of the four known fundamental interactions between the elementary particles that make up allmatter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic parti ...

. This theory allows predictions to be made about how particles will interact under many conditions. The energy per particle in a supernova is typically 1–150 picojoules (tens to hundreds of MeV

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. ...

).

The per-particle energy involved in a supernova is small enough that the predictions gained from the Standard Model of particle physics are likely to be basically correct. But the high densities may require corrections to the Standard Model.

In particular, Earth-based particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles to very high speeds and energies, and to contain them in well-defined beams.

Large accelerators are used for fundamental research in particle ...

s can produce particle interactions which are of much higher energy than are found in supernovae, but these experiments involve individual particles interacting with individual particles, and it is likely that the high densities within the supernova will produce novel effects. The interactions between neutrinos and the other particles in the supernova take place with the weak nuclear force, which is believed to be well understood. However, the interactions between the protons and neutrons involve the strong nuclear force

The strong interaction or strong force is a fundamental interaction that confines quarks into proton, neutron, and other hadron particles. The strong interaction also binds neutrons and protons to create atomic nuclei, where it is called the ...

, which is much less well understood.

The major unsolved problem with Type II supernovae is that it is not understood how the burst of neutrinos transfers its energy to the rest of the star producing the shock wave which causes the star to explode. From the above discussion, only one percent of the energy needs to be transferred to produce an explosion, but explaining how that one percent of transfer occurs has proven extremely difficult, even though the particle interactions involved are believed to be well understood. In the 1990s, one model for doing this involved convective overturn, which suggests that convection, either from neutrinos from below, or infalling matter from above, completes the process of destroying the progenitor star. Heavier elements than iron are formed during this explosion by neutron capture, and from the pressure of the neutrinos pressing into the boundary of the "neutrinosphere", seeding the surrounding space with a cloud of gas and dust which is richer in heavy elements than the material from which the star originally formed.

Neutrino physics, which is modeled by the Standard Model, is crucial to the understanding of this process. The other crucial area of investigation is the hydrodynamics

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids—liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including ''aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) and ...

of the plasma that makes up the dying star; how it behaves during the core collapse determines when and how the shockwave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a med ...

forms and when and how it stalls and is reenergized.

In fact, some theoretical models incorporate a hydrodynamical instability in the stalled shock known as the "Standing Accretion Shock Instability" (SASI). This instability comes about as a consequence of non-spherical perturbations oscillating the stalled shock thereby deforming it. The SASI is often used in tandem with neutrino theories in computer simulations for re-energizing the stalled shock.

Computer model

Computer simulation is the process of mathematical modelling, performed on a computer, which is designed to predict the behaviour of, or the outcome of, a real-world or physical system. The reliability of some mathematical models can be dete ...

s have been very successful at calculating the behavior of Type II supernovae when the shock has been formed. By ignoring the first second of the explosion, and assuming that an explosion is started, astrophysicists have been able to make detailed predictions about the elements produced by the supernova and of the expected light curve

In astronomy, a light curve is a graph of light intensity of a celestial object or region as a function of time, typically with the magnitude of light received on the y axis and with time on the x axis. The light is usually in a particular freq ...

from the supernova.

Light curves for Type II-L and Type II-P supernovae

When the

When the spectrum

A spectrum (plural ''spectra'' or ''spectrums'') is a condition that is not limited to a specific set of values but can vary, without gaps, across a continuum. The word was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of colors ...

of a Type II supernova is examined, it normally displays Balmer absorption lines – reduced flux at the characteristic frequencies where hydrogen atoms absorb energy. The presence of these lines is used to distinguish this category of supernova from a Type I supernova.

When the luminosity of a Type II supernova is plotted over a period of time, it shows a characteristic rise to a peak brightness followed by a decline. These light curves have an average decay rate of 0.008 magnitudes per day; much lower than the decay rate for Type Ia supernovae. Type II is subdivided into two classes, depending on the shape of the light curve. The light curve for a Type II-L supernova shows a steady ( linear) decline following the peak brightness. By contrast, the light curve of a Type II-P supernova has a distinctive flat stretch (called a plateau) during the decline; representing a period where the luminosity decays at a slower rate. The net luminosity decay rate is lower, at 0.0075 magnitudes per day for Type II-P, compared to 0.012 magnitudes per day for Type II-L.

The difference in the shape of the light curves is believed to be caused, in the case of Type II-L supernovae, by the expulsion of most of the hydrogen envelope of the progenitor star. The plateau phase in Type II-P supernovae is due to a change in the opacity of the exterior layer. The shock wave ionizes the hydrogen in the outer envelope – stripping the electron from the hydrogen atom – resulting in a significant increase in the opacity. This prevents photons from the inner parts of the explosion from escaping. When the hydrogen cools sufficiently to recombine, the outer layer becomes transparent.

Type IIn supernovae

The "n" denotes narrow, which indicates the presence of narrow or intermediate width hydrogen emission lines in the spectra. In the intermediate width case, the ejecta from the explosion may be interacting strongly with gas around the star – the circumstellar medium. The estimated circumstellar density required to explain the observational properties is much higher than that expected from the standard stellar evolution theory. It is generally assumed that the high circumstellar density is due to the high mass-loss rates of the Type IIn progenitors. The estimated mass-loss rates are typically higher than per year. There are indications that they originate as stars similar toluminous blue variable

Luminous blue variables (LBVs) are massive evolved stars that show unpredictable and sometimes dramatic variations in their spectra and brightness. They are also known as S Doradus variables after S Doradus, one of the brightest stars of the Large ...

s with large mass losses before exploding. SN 1998S and SN 2005gl are examples of Type IIn supernovae; SN 2006gy, an extremely energetic supernova, may be another example.

Type IIb supernovae

A Type IIb supernova has a weak hydrogen line in its initial spectrum, which is why it is classified as a Type II. However, later on the H emission becomes undetectable, and there is also a second peak in the light curve that has a spectrum which more closely resembles a Type Ib supernova. The progenitor could have been a massive star that expelled most of its outer layers, or one which lost most of its hydrogen envelope due to interactions with a companion in a binary system, leaving behind the core that consisted almost entirely of helium. As the ejecta of a Type IIb expands, the hydrogen layer quickly becomes more transparent and reveals the deeper layers. The classic example of a Type IIb supernova is SN 1993J, while another example is Cassiopeia A. The IIb class was first introduced (as a theoretical concept) by Woosley et al. in 1987, and the class was soon applied to SN 1987K and SN 1993J.See also

*History of supernova observation

The known history of supernova observation goes back to 185 AD, when supernova SN 185 appeared; which is the oldest appearance of a supernova recorded by mankind. Several additional supernovae within the Milky Way galaxy have been recorded since t ...

* Supernova remnant

References

External links

* * * {{Good article Type 2