Turabay Dynasty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

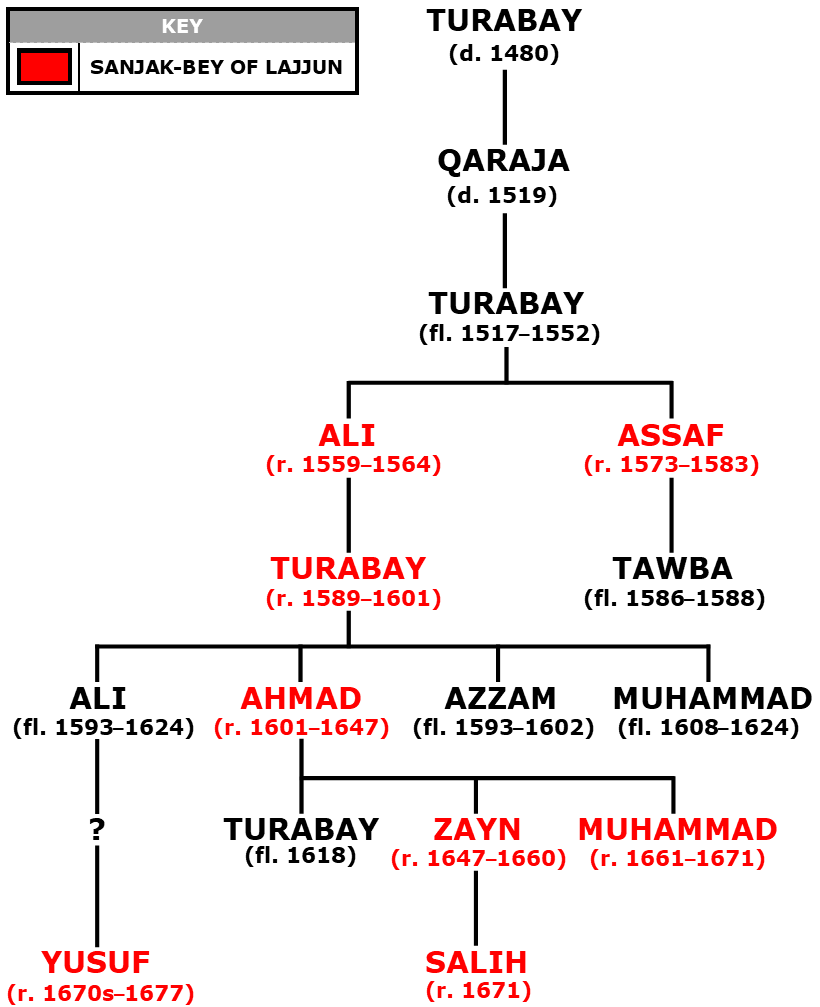

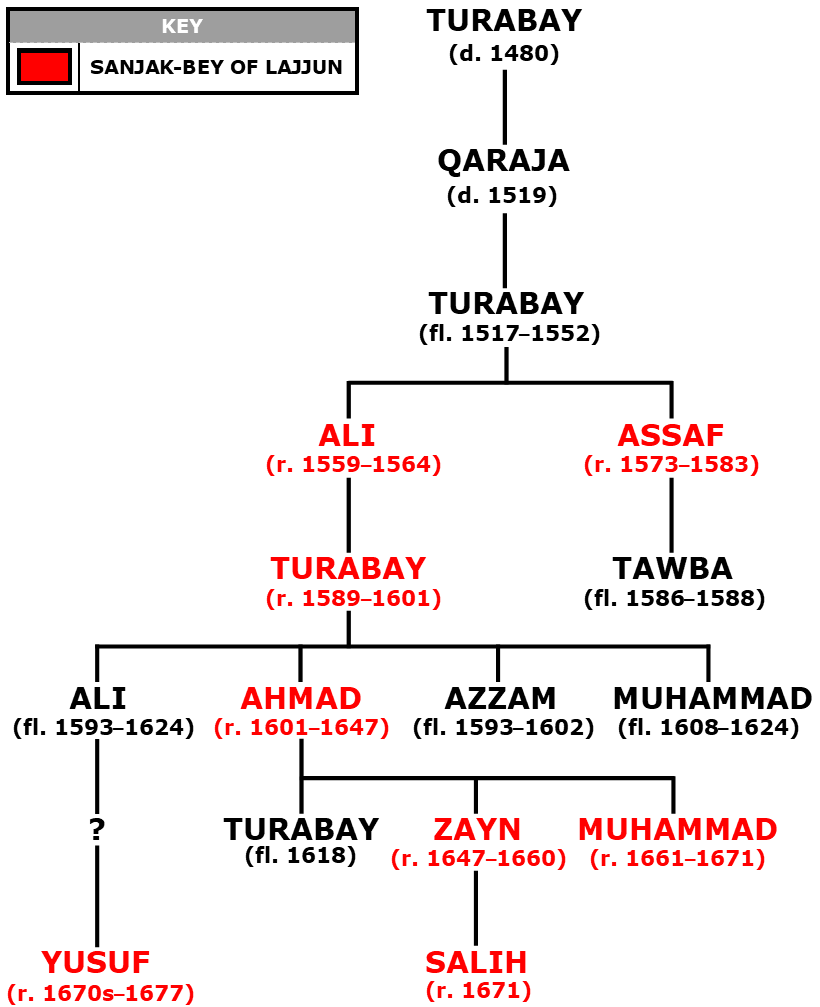

The Turabay dynasty () was the preeminent household of the

The Turabays were a family of the Banu Haritha tribe, a branch of the Sinbis, itself a branch of the

The Turabays were a family of the Banu Haritha tribe, a branch of the Sinbis, itself a branch of the

The Iqta of Turabay became its own sanjak, called the Lajjun Sanjak after its center,

The Iqta of Turabay became its own sanjak, called the Lajjun Sanjak after its center,

Turabay was succeeded as ''sanjak-bey'' of Lajjun by his son Ahmad Bey, the "greatest leader" of the dynasty, according to Sharon. Ahmad and his brother Ali Bey had already been joint holders of ''

Turabay was succeeded as ''sanjak-bey'' of Lajjun by his son Ahmad Bey, the "greatest leader" of the dynasty, according to Sharon. Ahmad and his brother Ali Bey had already been joint holders of ''

Ahmad's son Zayn Bey succeeded him as ''sanjak-bey'' and held the office until his death in 1660. Zayn was described by near-contemporary local and foreign sources as "courageous, wise and modest". His brother and successor Muhammad Bey was described by the French merchant and diplomat

Ahmad's son Zayn Bey succeeded him as ''sanjak-bey'' and held the office until his death in 1660. Zayn was described by near-contemporary local and foreign sources as "courageous, wise and modest". His brother and successor Muhammad Bey was described by the French merchant and diplomat

In their capacity as ''multazims'' the Turabays were responsible for collecting taxes in their jurisdiction on behalf of the Porte. They designated a

In their capacity as ''multazims'' the Turabays were responsible for collecting taxes in their jurisdiction on behalf of the Porte. They designated a  The Turabays retained their Bedouin way of life, living in tents among their Banu Haritha tribesmen. In the summers they encamped along the Na'aman River near Acre and in the winters they encamped near

The Turabays retained their Bedouin way of life, living in tents among their Banu Haritha tribesmen. In the summers they encamped along the Na'aman River near Acre and in the winters they encamped near

Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

Banu Haritha tribe in northern Palestine whose chiefs traditionally served as the ''multazim

An Iltizām (Arabic التزام) was a form of tax farm that appeared in the 15th century in the Ottoman Empire. The system began under Mehmed the Conqueror and was abolished during the Tanzimat reforms in 1856.

Iltizams were sold off by the gov ...

s'' (tax farmers) and '' sanjak-beys'' (district governors) of Lajjun Sanjak during Ottoman rule in the 16th–17th centuries. The sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησις (''dioikēsis'', meaning "province" ...

spanned the towns of Lajjun

Lajjun ( ar, اللجّون, ''al-Lajjūn'') was a large Palestinian Arab village in Mandatory Palestine, located northwest of Jenin and south of the remains of the biblical city of Megiddo. The Israeli kibbutz of Megiddo, Israel was built on ...

, Jenin

Jenin (; ar, ') is a State of Palestine, Palestinian city in the northern West Bank. It serves as the administrative center of the Jenin Governorate of the State of Palestine and is a major center for the surrounding towns. In 2007, Jenin had ...

, Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

and Atlit

Atlit ( he, עַתְלִית, ar, عتليت) is a coastal town located south of Haifa, Israel. The community is in the Hof HaCarmel Regional Council in the Haifa District of Israel.

Off the coast of Atlit is a submerged Neolithic village. At ...

and the surrounding countryside. The progenitors of the family had served as chiefs of Marj Bani Amir (the Plain of Esdraelon or Jezreel Valley) under the Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

s in the late 15th century.

During the Ottoman conquest in 1516–1517, the Turabay chief Qaraja and his son Turabay aided the forces of Ottoman sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

. The Ottomans kept them in their Mamluk-era role as guardians of the strategic Via Maris and Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

–Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

highways and rewarded them with tax farms in northern Palestine. Their territory became a sanjak in 1559 and Turabay's son Ali became its first governor. His brother Assaf was appointed in 1573, serving for ten years before being dismissed and exiled to Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

for involvement in a rebellion. His nephew Turabay was appointed in 1589 and remained in office until his death in 1601. His son and successor Ahmad, the most prominent chief of the dynasty, ruled Lajjun for nearly a half-century and repulsed attempts by the powerful Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

chief and Ottoman governor of Sidon-Beirut and Safad

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an eleva ...

, Fakhr al-Din Ma'n

Fakhr al-Din ibn Qurqumaz Ma'n ( ar, فَخْر ٱلدِّين بِن قُرْقُمَاز مَعْن, Fakhr al-Dīn ibn Qurqumaz Maʿn; – March or April 1635), commonly known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II ( ar, فخر الدين ال ...

, to take over Lajjun and Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

in the 1620s. In the effort, he consolidated the family's alliance with the Ridwan and Farrukh governing dynasties of Gaza and Nablus, which remained intact until the dynasties' demise toward the end of the century.

As ''multazims'' and ''sanjak-beys'' the Turabays were entrusted with collecting taxes for the Ottomans, quelling local rebellions, acting as judges, and securing roads. They were largely successful in these duties, while keeping good relations with the peasantry and the village chiefs of the sanjak. Although in the 17th century a number of their chiefs lived in the towns of Lajjun and Jenin, the Turabays largely preserved their nomadic way of life, pitching camp with their tribesmen near Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesar ...

in the winters and the plain of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

in the summers. The eastward migration of the Banu Haritha to the Jordan Valley, Ottoman centralization drives, and diminishing tax revenues brought about their political decline and they were permanently stripped of office in 1677. The family remained in the area, with members living in Jenin at the close of the century and in Tulkarm.

History

Origins

The Turabays were a family of the Banu Haritha tribe, a branch of the Sinbis, itself a branch of the

The Turabays were a family of the Banu Haritha tribe, a branch of the Sinbis, itself a branch of the Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

tribe of Tayy

, location = 2nd century CE–10th century: Jabal Tayy and Syrian Desert

10th century–16th century: Jabal Tayy, Syrian Desert, Jibal al-Sharat, al-Balqa, Palmyrene Steppe, Upper Mesopotamia, Northern Hejaz, Najd

, parent_tribe = Madh ...

. The Damascene historian al-Burini

Badr al-Din al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Dimashqi al-Saffuri al-Burini (July 1556-11 June 1615), commonly known as al-Hasan al-Burini, was a Damascus-based Ottoman Arab historian and poet and Shafi'i jurist.

Life

Al-Burini was born in mid-July 1556 i ...

(d. 1615) noted that the Turabays were the preeminent house of the Banu Haritha. During Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

rule in Palestine (1260s–1516) the eponymous progenitor of the family, Turabay, was recognized as the chief of Marj Bani Amir. Marj Bani Amir was an ''amal'' (subdistrict) of Mamlakat Safad (the province of Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an elev ...

). Turabay was executed in 1480 and replaced by his son Qaraja.

Early relations with the Ottomans

Qaraja's son Turabay joined the Ottoman sultanSelim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

during the latter's conquest of Mamluk Syria and participated in the subsequent conquest of Mamluk Egypt. On 8 February 1517, following his victory over the Mamluks, Selim wrote to Qaraja from Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, ordering him to capture Mamluk officials fleeing Egypt, transfer captive commanders to the sultan, and execute regular soldiers. On 2 February 1518, Qaraja paid homage to Selim in Damascus, where the sultan had stopped on his return to the imperial capital Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. The Damascene historian Ibn Tulun (d. 1546) referred to Qaraja as ''amir al-darbayn'' (commander of the two roads) in reference to his role as the protector of the Via Maris and the road connecting Lajjun to Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

via Jenin

Jenin (; ar, ') is a State of Palestine, Palestinian city in the northern West Bank. It serves as the administrative center of the Jenin Governorate of the State of Palestine and is a major center for the surrounding towns. In 2007, Jenin had ...

and Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

. In the Ottoman provincial system the part of Marj Bani Amir around the Daughters of Jacob Bridge

Daughters of Jacob Bridge ( he, גשר בנות יעקב, ''Gesher Bnot Ya'akov''; ar, جسر بنات يعقوب, ''Jisr Benat Ya'kub''). is a bridge that spans the last natural ford of the Jordan at the southern end of the Hula Basin between ...

remained under Safed's direct administration in the newly-formed Safed Sanjak

Safed Sanjak ( ar, سنجق صفد; tr, Safed Sancağı) was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Damascus Eyalet ( Ottoman province of Damascus) in 1517–1660, after which it became part of the Sidon Eyalet (Ottoman province of Sidon). The sanjak was ce ...

of Damascus Eyalet

ota, ایالت شام

, conventional_long_name = Damascus Eyalet

, common_name = Damascus Eyalet

, subdivision = Eyalet

, nation = the Ottoman Empire

, year_start = 1516

, year_end ...

, while much of the original ''amal'', along with the coastal ''amal'' of Atlit

Atlit ( he, עַתְלִית, ar, عتليت) is a coastal town located south of Haifa, Israel. The community is in the Hof HaCarmel Regional Council in the Haifa District of Israel.

Off the coast of Atlit is a submerged Neolithic village. At ...

, was administered separately in the " Iqta of Turabay". The area's separation from Safed Sanjak may have been done to reward or pacify the Turabays. Early 16th-century Ottoman tax documents record that fifty-one households of the Banu Haritha were encamped near the Daughters of Jacob Bridge.

The Ottoman ''beylerbey

''Beylerbey'' ( ota, بكلربكی, beylerbeyi, lit= bey of beys, meaning the 'commander of commanders' or 'lord of lords') was a high rank in the western Islamic world in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, from the Anatolian Selj ...

'' (provincial governor) of Damascus, Janbirdi al-Ghazali, captured and executed Qaraja in 1519, along with three chiefs from the area of Nablus. The execution was likely connected to an earlier attack by Bedouin tribesmen against a Muslim pilgrim caravan returning to Damascus from the Hajj

The Hajj (; ar, حَجّ '; sometimes also spelled Hadj, Hadji or Haj in English) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried o ...

in Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

. After the death of Selim in 1520 Janbirdi revolted and declared himself sultan. He was supported by the Bedouin tribes of Banu Ata, Banu Atiyya and Sawalim (all based around Gaza and Ramla

Ramla or Ramle ( he, רַמְלָה, ''Ramlā''; ar, الرملة, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

), who were aligned against the Turabays. Under the leadership of Qaraja's son Turabay, the family fought alongside the Ottomans against the rebels, who were defeated. Turabay gained the confidence of the Ottomans following the suppression of Janbirdi's revolt. He was entrusted in 1530/31 with overseeing the construction of the Ukhaydir fort in the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

on the Hajj caravan route to Mecca. A further testament to Ottoman confidence in Turabay was the large size of his ''iltizam

An Iltizām (Arabic التزام) was a form of tax farm that appeared in the 15th century in the Ottoman Empire. The system began under Mehmed the Conqueror and was abolished during the Tanzimat reforms in 1856.

Iltizams were sold off by the gov ...

'' (tax farm), the revenues of which amounted to 516,855 akces. His ''iltizam'' spanned the subdistricts of Qaqun

Qaqun ( ar, قاقون) was a Palestinian Arab village located northwest of the city of Tulkarm at the only entrance to Mount Nablus from the coastal Sharon plain.

Evidence of organized settlement in Qaqun dates back to the period of Assyrian ...

, Marj Bani Amir, Ghawr, Banu Kinana, Banu Atika and Banu Juhma, at the time located in the sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησις (''dioikēsis'', meaning "province" ...

s of Safed, Ajlun

Ajloun ( ar, عجلون, ''‘Ajlūn''), also spelled Ajlun, is the capital town of the Ajloun Governorate, a hilly town in the north of Jordan, located 76 kilometers (around 47 miles) north west of Amman. It is noted for its impressive ruins of t ...

and Damascus. His uncle Budah and son Sab' held ''timar

A timar was a land grant by the sultans of the Ottoman Empire between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, with an annual tax revenue of less than 20,000 akçes. The revenues produced from the land acted as compensation for military service ...

s'' (fiefs) in the subdistricts of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

in 1533–1536 and Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

in 1533–1539, respectively.

There may have been tensions between Turabay and Sinan Pasha al-Tuwashi, ''beylerbey'' of Damascus in 1545–1548, and the latter's successors. In 1552 the Turabays were accused of rebellion for acquiring illegal firearms and the authorities warned the '' sanjak-beys'' (district governors) of Damascus Eyalet to prohibit their subjects' dealings with the family. A nephew of Turabay was sent to Damascus to secure a pardon for the family. The information about this event is unclear, but the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

(Ottoman imperial government) requested the ''beylerbey'' of Damascus to lure and punish the family; Turabay may have been killed as a consequence.

Early governors of Lajjun

The Iqta of Turabay became its own sanjak, called the Lajjun Sanjak after its center,

The Iqta of Turabay became its own sanjak, called the Lajjun Sanjak after its center, Lajjun

Lajjun ( ar, اللجّون, ''al-Lajjūn'') was a large Palestinian Arab village in Mandatory Palestine, located northwest of Jenin and south of the remains of the biblical city of Megiddo. The Israeli kibbutz of Megiddo, Israel was built on ...

in 1559. Turabay's son Ali was appointed the new district's ''sanjak-bey'', becoming the first member of the family to hold the office. Under his leadership, the Turabays once again entered into a state of rebellion by acquiring firearms and Ali was replaced by a certain official, Kemal Bey, in 1564. Three years later the Porte ordered the arrest and imprisonment of a certain member of the family for stockpiling arms. Ali was succeeded as head of the family by Assaf, who worked to reconcile with the Ottomans by demonstrating his obedience to the Porte. He allied with the ''sanjak-bey'' of Gaza, Ridwan Pasha

Riḍwān ibn Muṣṭafā ibn ʿAbd al-Muʿīn Pasha ( Turkish transliteration: ''Ridvan Pasha''; died 2 April 1585) was a 16th-century Ottoman statesman. He served terms as governor of Gaza in the early 1560s and in 1570–1573, Yemen in 1564/ ...

, who lobbied on his behalf to the Porte, writing that Assaf safeguarded the road between Cairo and Damascus. The Porte responded in 1571 that if he continued to be obedient he would be granted the sultan's favor. Two years later he was appointed ''sanjak-bey'' of Lajjun.

Assaf was dismissed in 1583 in connection to a Bedouin rebellion. Six years later he was exiled to Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, pardoned, and allowed to return and reside in Lajjun, but was not reinstated as ''sanjak-bey''. During his absence an impostor with the same name, referred to in Ottoman documents as "Assaf the Liar" had gained control of the sanjak. The Ottomans appointed another member of the family, Turabay ibn Ali, as ''sanjak-bey'' on 22 November 1589. Assaf the Liar went to Damascus in an attempt to legalize his control of the sanjak. Although the ''beylerbey'' of Damascus, Muhammad Pasha ibn Sinan Pasha sought to grant his request, the Porte ordered that he be arrested and executed in October 1590. Two years later the actual Assaf lodged a complaint against Turabay ibn Ali, accusing him of having seized from him 150,000 coins, 300 camels and 2,500 calves. Turabay ibn Ali continued in office until his death in 1601 and in 1594 had also acted as a placeholder for the ''sanjak-bey'' of Gaza, Ahmad Pasha ibn Ridwan. According to the historian Abdul-Rahim Abu-Husayn, Turabay demonstrated "a special capability" and the Ottomans had "confidence in his person". By the 17th century the Banu Haritha's dwelling areas were in the coastal plain of Palestine between Qaqun in the northern coastal plain and Kafr Kanna

Kafr Kanna ( ar, كفر كنا, ''Kafr Kanā''; he, כַּפְר כַּנָּא) is an Arab town in the Galilee, part of the Northern District of Israel. It is associated by Christians with the New Testament village of Cana, where Jesus tur ...

in the Lower Galilee The Lower Galilee (; ar, الجليل الأسفل, translit=Al Jalil Al Asfal) is a region within the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. The Lower Galilee is bordered by the Jezreel Valley to the south; the Upper Galilee to t ...

and the surrounding hinterland.

Governorship of Ahmad

Turabay was succeeded as ''sanjak-bey'' of Lajjun by his son Ahmad Bey, the "greatest leader" of the dynasty, according to Sharon. Ahmad and his brother Ali Bey had already been joint holders of ''

Turabay was succeeded as ''sanjak-bey'' of Lajjun by his son Ahmad Bey, the "greatest leader" of the dynasty, according to Sharon. Ahmad and his brother Ali Bey had already been joint holders of ''ziamet Ziamet was a form of land tenure in the Ottoman Empire, consisting in grant of lands or revenues by the Ottoman Sultan to an individual in compensation for their services, especially military services. The ziamet system was introduced by Osman I, wh ...

'' (land grants) worth 20,000 akces in the Atlit subdistrict from 1593. Ahmad's rule over Lajjun was soon followed with the appointment of the Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

chieftain Fakhr al-Din Ma'n

Fakhr al-Din ibn Qurqumaz Ma'n ( ar, فَخْر ٱلدِّين بِن قُرْقُمَاز مَعْن, Fakhr al-Dīn ibn Qurqumaz Maʿn; – March or April 1635), commonly known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II ( ar, فخر الدين ال ...

to the Safed Sanjak. Fakhr al-Din had already been in control of the ports of Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

and Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, and southern Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

as the ''sanjak-bey'' of Sidon-Beirut; with the appointment to Safed Sanjak, his control was extended to the port of Acre and the Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

. Abu-Husayn notes that "this had the effect of bringing the two chiefs, as immediate neighbors, into direct confrontation with one another". During the rebellion of Ali Janbulad

Ali Janbulad Pasha (transliterated in Turkish as Canbolatoğlu Ali Paşa; died 1 March 1610) was a Kurdish tribal chief from Kilis and a rebel Ottoman governor of Aleppo who wielded practical supremacy over Syria in . His rebellion, launched ...

of Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

and Fakhr al-Din against the Ottomans in Syria in 1606, Ahmad generally remained neutral. However, he welcomed the overall commander of the Ottoman forces in the region, Yusuf Sayfa, in Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

after the rebels ousted him from Tripoli. Janbulad demanded Ahmad execute Yusuf, but he refused, and Yusuf made his way to Damascus. Later, he ignored summons to join the imperial army of Grand Vizier Murad Pasha, who suppressed the rebellion in 1607. Interested in weakening his powerful neighbor to the north, Ahmad joined the government campaign of Hafiz Ahmed Pasha against Fakhr al-Din and his Ma'n dynasty in Mount Lebanon in 1613–1614, which prompted the Druze chief's flight to Europe.

Upon his pardon and return in 1618, Fakhr al-Din pursued an expansionist policy, making conflict between him and the Turabays "inevitable", according to Abu-Husayn. Initially, Ahmad dispatched his son Turabay with a present of Arabian horses to welcome back Fakhr al-Din. When Fakhr al-Din and his '' kethuda'' Mustafa were appointed to the sanjaks of Ajlun and Nablus, respectively, in 1622, Ahmad's brother-in-law, a certain resident of Nablus Sanjak called Shaykh Asi, refused to recognize the new governor. At the same, Ahmad entered into conflict with Mustafa over control of the village of Qabatiya and the surrounding farms. Reinforcements sent to Mustafa to fight the Turabays were defeated by the villagers of Nablus. Further, Mustafa and Fakhr al-Din opposed the refuge Ahmad offered to fleeing peasants from the Nablus area and Shia Muslim

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most ...

rural chieftains fleeing Safed Sanjak.

When Fakhr al-Din and his proxies were dismissed from the sanjaks of Safed, Ajlun and Nablus in 1623, Ahmad backed their replacements Bashir Qansuh in Ajlun and Muhammad ibn Farrukh in Nablus. Starting in the 16th century, the Turabays had developed a military, economic and marital alliance with the Farrukhs of Nablus and the Ridwans of Gaza. By the following century, the extensive ties between the three ruling families practically made them "one extended family" according to the historian Dror Ze'evi. Fakhr al-Din responded to Turabays' support for his replacements by dispatching troops to capture the tower of Haifa and burn villages in Mount Carmel

Mount Carmel ( he, הַר הַכַּרְמֶל, Har haKarmel; ar, جبل الكرمل, Jabal al-Karmil), also known in Arabic as Mount Mar Elias ( ar, link=no, جبل مار إلياس, Jabal Mār Ilyās, lit=Mount Saint Elias/ Elijah), is a ...

in Ahmad's jurisdiction, which were hosting Shia refugees from Safed Sanjak. At the head of an army of ''sekban

The Sekban were mercenaries of peasant background in the Ottoman Empire. The term ''sekban'' initially referred to irregular military units, particularly those without guns, but ultimately it came to refer to any army outside the regular military ...

'' mercenaries, Fakhr al-Din captured Jenin, which he garrisoned, and proceeded to resend Mustafa to Nablus. The two sides met in battle at the Awja River, where Ahmad and his local allies decisively defeated Fakhr al-Din and forced his retreat. The Porte expressed its gratitude to Ahmad and his allies by enlarging his land holdings.

The Druze chief soon had to contend with a campaign from the ''beylerbey'' Mustafa Pasha of Damascus, allowing Ahmad to clear Lajjun Sanjak of the residual Ma'nid presence. To that end his brother Ali recaptured the tower of Haifa, killed the commander of the Ma'nid ''sekbans'' there, and raided the plain around Acre. Fakhr al-Din defeated and captured Mustafa Pasha in the Battle of Anjar

The Battle of Anjar was fought on 1 November 1623 between the army of Fakhr al-Din II and an coalition army led by the governor of Damascus Mustafa Pasha.

Background

In 1623, Yunus al-Harfush prohibited the Druze of the Chouf from cultivatin ...

later that year and extracted from the ''beylerbey'' the appointment of his son Mansur as ''sanjak-bey'' of Lajjun. Nonetheless, the Ma'nids could not gain control of the sanjak, even after recapturing the tower of Haifa in May/June 1624. Ahmad sued for a peaceful arrangement with Fakhr al-Din, but the latter offered him deputy control of the sanjak and conditioned it on Ahmad's submission to Fakhr al-Din in person; Ahmad ignored the offer. Later that month Ahmad and his ally Muhammad ibn Farrukh defeated Fakhr al-Din in battle and shortly after dislodged the Ma'nid ''sekbans'' stationed in Jenin. At the end of June, Ahmad took up residence in the town. He then sent his Bedouin troops to raid the plain of Acre.

Afterward, Ahmad and Fakhr al-Din reached an agreement stipulating the withdrawal of Ma'nid troops from the tower of Haifa, an end to Bedouin raids against Safed Sanjak, and the establishment of peaceful relations; afterward "communication between ''bilad'' he lands of BanuHaritha and ''bilad'' Safad was resumed", according to the contemporary local historian Ahmad al-Khalidi

Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Khālidī al-Safadī (died 1625) was an Ottoman historian and the Hanafi mufti of Safed . He was best known for being the adviser of the powerful Druze chief and tax farmer Fakhr al-Din II after the latter was appointed g ...

. Ahmad had the tower of Haifa demolished, likely to avoid a future a Ma'nid takeover. According to Sharon, the Turabays' victories against the Ma'n "compelled" Fakhr al-Din "to abandon his plans for subjecting northern Palestine", while Bakhit stated that Fakhr al-Din's retreat from Turabay territory to confront the Damascenes and their local allies at Anjar "rescued him from probable destruction at the hands of Ahmad Turabay". The Ottomans launched a campaign against Fakhr al-Din in 1633, during which he was captured. One of his nephews who survived the campaign, Mulhim, was given refuge by Ahmad. Upon learning of Fakhr al-Din's capture and the death of Mulhim's father Yunus, Ahmad arranged for one of his ''kethudas'' to surrender Mulhim to the authorities in Damascus, but Mulhim escaped.

Ahmad was dismissed as ''sanjak-bey'' in May 1640 for his role in a rebellion, but reappointed in the same year. He remained in office until his death in 1647. At different times during his governorship, his brothers Ali, Azzam and Muhammad and son Zayn Bey held ''iltizam'', ''timars'', and ''ziamets'' of the sanjak in general or the subdistricts of Atlit, Shara and Shafa.

Later chiefs and downfall

Ahmad's son Zayn Bey succeeded him as ''sanjak-bey'' and held the office until his death in 1660. Zayn was described by near-contemporary local and foreign sources as "courageous, wise and modest". His brother and successor Muhammad Bey was described by the French merchant and diplomat

Ahmad's son Zayn Bey succeeded him as ''sanjak-bey'' and held the office until his death in 1660. Zayn was described by near-contemporary local and foreign sources as "courageous, wise and modest". His brother and successor Muhammad Bey was described by the French merchant and diplomat Laurent d'Arvieux Laurent d'Arvieux (21 June 1635 – 30 October 1702) was a French traveller and diplomat born in Marseille.Le Consulat de France à Alep au XVIIe siecle2009, p.29-38

Arvieux is known for his travels in the Middle East, which began in 1654 as a ...

as a dreamy chief heavily addicted to hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. European Monitoring ...

. The fortunes of the family began to deteriorate under his chieftainship, though he continued to successfully perform his duties as ''sanjak-bey'', protecting the roads and helping suppress a peasants' revolt in Nablus Sanjak. D'Arvieux was dispatched by the French consul of Sidon in August 1664 to request from Muhammad the reestablishment of monks from the Carmelite Order

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Ca ...

in Mount Carmel. Muhammad befriended d'Arvieux, who afterward served as his secretary for Arabic and Turkish correspondences while Muhammad's usual secretary was ill. Muhammad died on 1 October 1671 and was buried in Jenin.

Throughout the late 17th century the Porte, having eliminated the power of Fakhr al-Din, who "had reduced Ottoman authority in Syria to a mere shadow" in the words of Abu-Husayn, embarked on a centralization drive in the western districts of Damascus Eyalet to suppress the power of local chiefs. In Palestine the Turabays, Ridwans and Farrukhs considered the region's sanjaks to be their own and resisted imperial attempts to weaken their control, while being careful not to openly rebel against the Porte. The Porte became increasingly concerned with the local dynasties in the late 17th century due to decreasing tax revenues from their sanjaks and the loss of control of the Hajj caravan routes. High-ranking officers, governors of districts outside of Syria, and family members of the imperial elite were gradually appointed to the sanjaks of Damascus. Implementation of the policy proved challenging in the case of the Turabays in Lajjun; their chiefs were occasionally dismissed but would shortly after regain office. With the imprisonment and execution of the Ridwan governor Husayn Pasha in 1662/63, and the mysterious death of the ''sanjak-bey'' Assaf Farrukh on his way to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in 1670/71, the alliance of the three dynasties was fatally weakened.

The Turabays' position declined further with Muhammad's death. His nephews succeeded him as ''sanjak-bey'' for relatively short stints: Salih Bey, the son of Zayn, ruled until he was succeeded by his cousin Yusuf Bey, the son of Ali. Yusuf was dismissed from the post in 1677 and replaced by an Ottoman officer, Ahmed Pasha al-Tarazi, who was also appointed to other sanjaks in Palestine; "the ttomangovernment had abandoned them", in the contemporary historian al-Muhibbi's words. The Turabays' governorship of Lajjun thus ended and the family "ceased to be a ruling power" in the words of Bakhit. Sharon attributes the decline of the Turabays to the eastward migration of the Banu Haritha to the Jordan Valley and the Ajlun region in the late 17th century. In the last years of the 17th century, the Turabays were politically replaced in northern Palestine by the semi-Bedouin Banu Zaydan of Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Daher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar ( ar, ظاهر العمر الزيداني, translit=Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 or 22 August 1775) was the autonomous Arab ruler of northern Pale ...

.

Although they were dispossessed of their government, the Turabays remained in the sanjak. The emirs of the dynasty were visited in Jenin by the Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

traveler Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi

Shaykh 'Abd al-Ghani ibn Isma′il al-Nabulsi (an-Nabalusi) (19 March 1641 – 5 March 1731), was an eminent Sunni Muslim scholar, poet, and author on works about Sufism, ethnography and agriculture.

Family origins

Abd al-Ghani's family descen ...

(d. 1731), who wrote that "They are now in eclipse". Sharon notes that "the memory of the Turabays was completely erased with their fall". Descendants of the family lived in Tulkarm and were known as the Tarabih. The Tarabih were part of the Fuqaha clan, which was a collective of several families genealogically unrelated to each other. The Fuqaha were the religious scholarly elite of Tulkarm in the 17th–19th centuries.

Governance and way of life

In their capacity as ''multazims'' the Turabays were responsible for collecting taxes in their jurisdiction on behalf of the Porte. They designated a

In their capacity as ''multazims'' the Turabays were responsible for collecting taxes in their jurisdiction on behalf of the Porte. They designated a sheikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

(chief) in each village in the sanjak to collect the taxes from the peasants. The village sheikhs paid the Turabay emirs based on the harvest. In return, the lives and properties of the village chiefs were defended by the Turabays. In the words of Sharon, the Turabays "developed good and effective relations with the sedentary population". The annual revenues forwarded to the emir in the late 17th century amounted to about 100,000 piasters, a relatively small amount. The Turabays levied customs on the European ships which occasionally docked in the harbors of Haifa and Tantura. Both ports were also used by the Turabays for their own imports, including coffee, vegetables, rice and cloth. The revenues derived from Haifa ranged from 1,000 akces in 1538 to 10,000 akces in 1596, while the combined revenues of Tantura, Tirat Luza (near Mount Carmel) and Atlit were 5,000 akces in 1538. The family's emirs may have served as the qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a '' sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and mino ...

s (head judges) of the sanjak, at least in the case of Muhammad Turabay. D'Arvieux noted that Muhammad rarely ordered death sentences.

The Turabays were responsible for ensuring the safety of the sanjak's roads for traveling merchants and the imperial post, and suppressing local rebellions. Their success in guarding the roads was frequently acknowledged in Ottoman government documents where their chiefs are referred to by their Mamluk-era title ''amir al-darbayn''. The Turabay emirs ignored their official duty as ''sanjak-beys'' to participate in imperial wars upon demand, but they generally remained loyal to the Ottomans in Syria, including during the peak of Fakhr al-Din's power. The Turabays' army was composed of their tribesmen, whose solidarity stood in contrast to the ''sekbans'' of Fakhr al-Din who fought for pay; the Turabays' battlefield successes against the latter were likely owed to their tribal power base. At the time of d'Arvieux's visit, Muhammad Turabay could field an army of 4,000–5,000 Bedouin warriors. The Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagre ...

faith of the Turabays also helped secure the favor of the Sunni Muslim Ottoman state.

The Turabays retained their Bedouin way of life, living in tents among their Banu Haritha tribesmen. In the summers they encamped along the Na'aman River near Acre and in the winters they encamped near

The Turabays retained their Bedouin way of life, living in tents among their Banu Haritha tribesmen. In the summers they encamped along the Na'aman River near Acre and in the winters they encamped near Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesar ...

. D'Arvieux noted that their chiefs could have resided in palaces, but chose not to; they remained nomadic out of pride. Although they retained their nomadic tents, by the 17th century they also established residences in the towns of Lajjun and Jenin. The family, and the Banu Haritha in general, were mainly dependent on livestock for their source of living. Their main assets were their horses, camels, cattle, goats, sheep and grain. According to Sharon, "they introduced two innovations as a mark of their official status": the employment of a secretary to handle their correspondences and the use of a band composed of tambourines, oboes, drums and trumpets. Assaf built a mosque in Tirat Luza in 1579/80, which contained an inscription bearing his name ("Emir Assaf ibn Nimr Bey"). The family designated Jenin as the administrative headquarters of the sanjak and buried their dead in the town's Izz al-Din cemetery. Turabay ibn Ali was the first emir of the family to be buried in a mausoleum, later known as Qubbat al-Amir Turabay (Dome of Amir Turabay). The building was the only grave of the Turabays to have survived into the 20th century and no longer exists today. It consisted of a domed chamber housing the tombstone of the emir with a two-line inscription reading: Basmalah 'in the name of God'' This is the tomb of the slave who is in need of his Lord, the Exalted, al-Amir Turabay b. Ali. The year 1010 H, i.e. 1601 CEThe Turabay emirs oversaw nearly a century of relative peace and stability in northern Palestine. According to Abu-Husayn, they maintained the favor of the Ottomans by "properly attending to the administrative and guard duties assigned to them" and served as an "example of a dynasty of bedouin chiefs who managed to perpetuate their control over a given region". They stood in contrast to their Bedouin contemporaries, the Furaykhs of the

Beqaa Valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

, who used initial imperial favor to enrich themselves at the expense of the proper governance of their territory. As a result of their administrative success, military strength, and loyalty to the Porte, the Turabays were one of the few local dynasties to maintain their rule throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * *{{cite book , last1=Ze'evi , first1=Dror , author-link1= Dror Ze'evi, title=An Ottoman Century: The District of Jerusalem in the 1600s , url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EN-Pd-JLybUC , year=1996 , publisher=State University of New York Press , location=Albany , isbn=0-7914-2915-6 Ottoman Palestine Jenin Arabs from the Ottoman Empire 17th-century Arabs 16th-century Arabs 15th-century Arabs Arabs from the Mamluk Sultanate Political people from the Ottoman Empire Arab dynasties Sunni dynasties