Tommy Douglas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

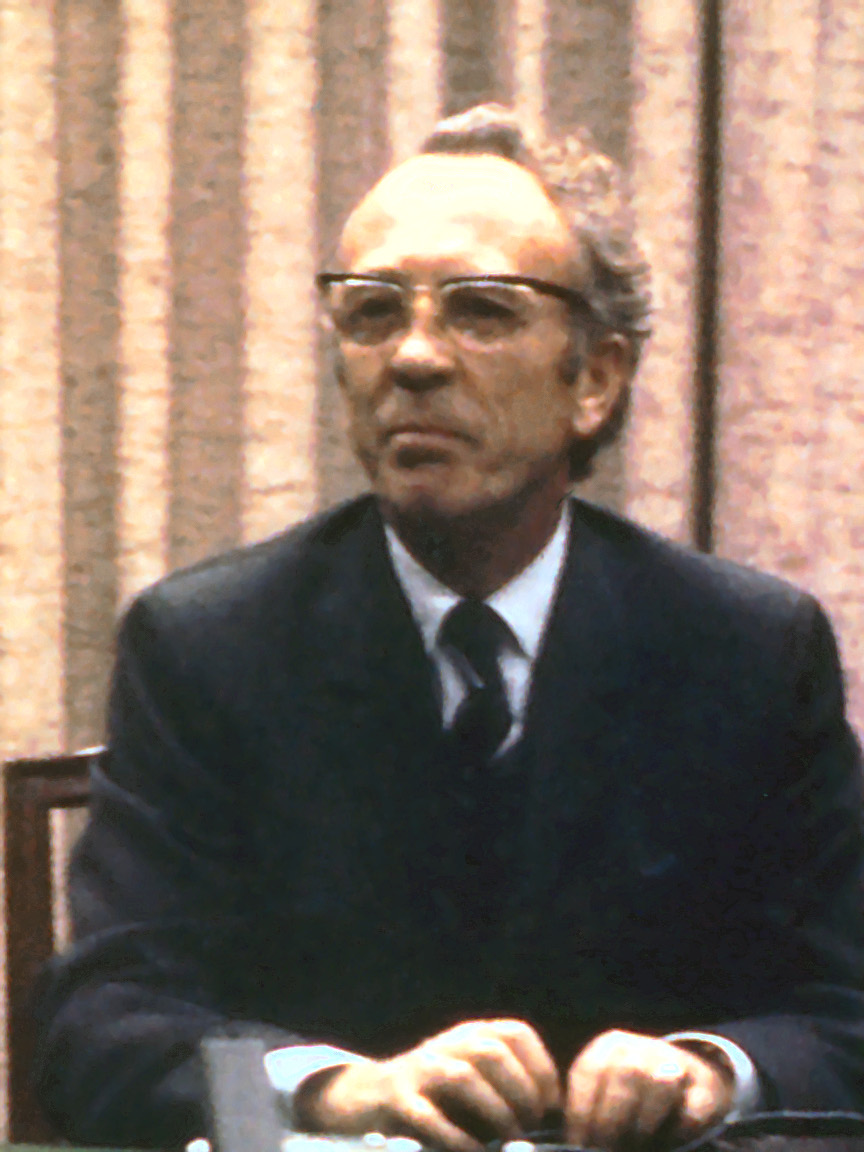

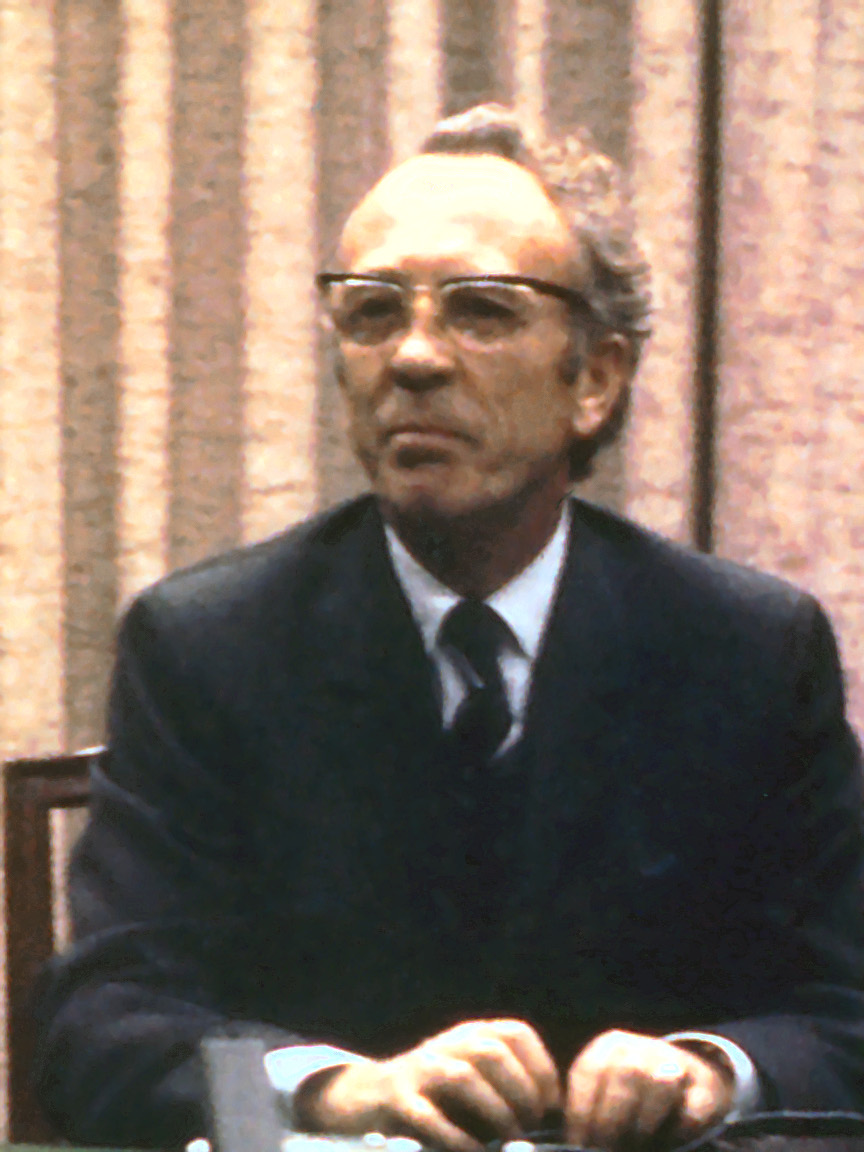

Thomas Clement Douglas (20 October 1904 – 24 February 1986) was a Scottish-born Canadian politician who served as seventh

The 1958 Canadian general election was a disaster for the CCF; its caucus was reduced to eight, and party leader M. J. Coldwell lost his own seat. The CCF executive knew that their party was dying and needed radical change. The executive persuaded Coldwell to remain as leader, but the party also needed a leader in the House of Commons to replace him, because he obviously was no longer a Member of Parliament. The CCF parliamentary caucus chose Hazen Argue as its new leader in the House. During the lead-up to the 1960 CCF convention, Argue was pressing Coldwell to step down; this leadership challenge jeopardized plans for an orderly transition to the new party that was being planned by the CCF and the

The 1958 Canadian general election was a disaster for the CCF; its caucus was reduced to eight, and party leader M. J. Coldwell lost his own seat. The CCF executive knew that their party was dying and needed radical change. The executive persuaded Coldwell to remain as leader, but the party also needed a leader in the House of Commons to replace him, because he obviously was no longer a Member of Parliament. The CCF parliamentary caucus chose Hazen Argue as its new leader in the House. During the lead-up to the 1960 CCF convention, Argue was pressing Coldwell to step down; this leadership challenge jeopardized plans for an orderly transition to the new party that was being planned by the CCF and the

Douglas Provincial Park near Saskatchewan's

Douglas Provincial Park near Saskatchewan's

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Tommy Douglas and his Government 1944–1960

* * *

Douglas Provincial Park

{{DEFAULTSORT:Douglas, Tommy 1904 births 1986 deaths Scottish military personnel The Canadian Grenadier Guards soldiers Canadian Army personnel of World War II 20th-century Canadian Baptist ministers Canadian eugenicists Brandon University alumni British emigrants to Canada Canadian democratic socialists Canadian socialists Canadian Christian socialists Baptist socialists Canadian anti-poverty activists Co-operative Commonwealth Federation MPs 20th-century Canadian politicians Companions of the Order of Canada Leaders of the Saskatchewan CCF/NDP McMaster University alumni Members of the House of Commons of Canada from British Columbia Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Saskatchewan Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Members of the Saskatchewan Order of Merit NDP and CCF leaders New Democratic Party MPs People from Falkirk Politicians from Brandon, Manitoba Politicians from Winnipeg Premiers of Saskatchewan Saskatchewan Co-operative Commonwealth Federation MLAs Scottish Christian socialists Scottish emigrants to Canada Deaths from cancer in Ontario Typesetters Royal Canadian Geographical Society fellows Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Burials at Beechwood Cemetery (Ottawa)

premier of Saskatchewan

The premier of Saskatchewan is the first minister and head of government for the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The current premier of Saskatchewan is Scott Moe, who was sworn in as premier on February 2, 2018, after winning the 2018 Saskatc ...

from 1944 to 1961 and Leader of the New Democratic Party

The New Democratic Party (NDP; french: Nouveau Parti démocratique, NPD) is a federal political party in Canada. Widely described as social democratic,The party is widely described as social democratic:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* ...

from 1961 to 1971. A Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

minister, he was elected to the House of Commons of Canada

The House of Commons of Canada (french: Chambre des communes du Canada) is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the bicameral legislature of Canada.

The House of Commo ...

in 1935 as a member of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF; french: Fédération du Commonwealth Coopératif, FCC); from 1955 the Social Democratic Party of Canada (''french: Parti social démocratique du Canada''), was a federal democratic socialistThe follo ...

(CCF). He left federal politics to become Leader of the Saskatchewan Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and then the seventh Premier of Saskatchewan. His government introduced the continent's first single-payer

Single-payer healthcare is a type of universal healthcare in which the costs of essential healthcare for all residents are covered by a single public system (hence "single-payer").

Single-payer systems may contract for healthcare services from ...

, universal health care program.

After setting up Saskatchewan's universal healthcare program, Douglas stepped down and ran to lead the newly formed federal New Democratic Party (NDP), the successor party of the national CCF. He was elected as its first federal leader in 1961. Although Douglas never led the party to government, through much of his tenure the party held the balance of power in the House of Commons. He was noted as being the main opposition to the imposition of the ''War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (french: Loi sur les mesures de guerre; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could t ...

'' during the 1970 October Crisis

The October Crisis (french: Crise d'Octobre) refers to a chain of events that started in October 1970 when members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the provincial Labour Minister Pierre Laporte and British diplomat James Cr ...

. He resigned as leader the next year, but remained as a Member of Parliament until 1979.

Douglas was awarded many honorary degrees, and a foundation was named for him and his political mentor M. J. Coldwell in 1971. In 1981, he was invested into the Order of Canada

The Order of Canada (french: Ordre du Canada; abbreviated as OC) is a Canadian state order and the second-highest honour for merit in the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, after the Order of Merit.

To coincide with the cen ...

, and he became a member of Canada's Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

in 1984, two years before his death. In 2004, a CBC Television

CBC Television (also known as CBC TV) is a Canadian English-language broadcast television network owned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the national public broadcaster. The network began operations on September 6, 1952. Its French- ...

program named Tommy Douglas "The Greatest Canadian

''The Greatest Canadian'' is a 2004 television series consisting of 13 episodes produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) to determine who is considered to be the greatest Canadian of all time, according to those who watched and p ...

", based on a Canada-wide, viewer-supported survey.

Early life

Thomas Clement Douglas was born in 1904 inCamelon

Camelon (; sco, Caimlan, gd, Camlann)

is a large set ...

, is a large set ...

Falkirk

Falkirk ( gd, An Eaglais Bhreac, sco, Fawkirk) is a large town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland, historically within the county of Stirlingshire. It lies in the Forth Valley, northwest of Edinburgh and northeast of Glasgow.

Falkirk had ...

, Scotland, the son of Annie (née Clement) and Thomas Douglas, an iron moulder A moldmaker (mouldmaker in English-speaking countries other than the US) or molder is a skilled tradesperson who fabricates moulds for use in casting metal products.

Moldmakers are generally employed in foundries, where molds are used to cast p ...

who fought in the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

. In 1910, his family emigrated to Canada, where they settled in Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

. Shortly before he left Scotland, Douglas fell and injured his right knee. Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is an infection of bone. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The long bones of the arms and legs are most commonly involved in children e.g. the femur and humerus, while the ...

set in and he underwent a number of operations in Scotland in an attempt to cure the condition. Later in Winnipeg, the osteomyelitis flared up again, and Douglas was sent to hospital. Doctors there told his parents his leg would have to be amputated; however, a well-known orthopedic surgeon

Orthopedic surgery or orthopedics ( alternatively spelt orthopaedics), is the branch of surgery concerned with conditions involving the musculoskeletal system. Orthopedic surgeons use both surgical and nonsurgical means to treat musculoskeletal ...

took interest and agreed to treat him for free if his parents allowed medical students to observe. After several operations, Douglas's leg was saved. This experience convinced him that health care should be free to all. Many years later, Douglas told an interviewer, "I felt that no boy should have to depend either for his leg or his life upon the ability of his parents to raise enough money to bring a first-class surgeon to his bedside."

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the family went back to Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

. They returned to Winnipeg in late 1918, in time for Douglas to witness the Winnipeg general strike. From a rooftop vantage point on Main Street, he witnessed the police charging the strikers with clubs and guns, and a streetcar being overturned and set on fire. He also witnessed the RCMP

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; french: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; french: GRC, label=none), commonly known in English as the Mounties (and colloquially in French as ) is the federal and national police service of Canada. As poli ...

shoot and kill one of the workers. This incident influenced Douglas later in life by cementing his commitment to protect fundamental freedoms in a Bill of Rights when he was premier of Saskatchewan.

In 1920, at the age of 15, Douglas began amateur boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

at the One Big Union gym in Winnipeg. Weighing , he won the 1922 Lightweight Championship of Manitoba after a six-round fight. Douglas sustained a broken nose, a loss of some teeth, and a strained hand and thumb. He held the title the following year.

In 1930, Douglas married Irma Dempsey, a music student at Brandon College

Brandon University is a university located in the city of Brandon, Manitoba, Canada, with an enrollment of 3375 (2020) full-time and part-time undergraduate and graduate students. The current location was founded on July 13, 1899, as Brandon C ...

. They had one daughter, actress Shirley Douglas

Shirley Jean Douglas (April 2, 1934 – April 5, 2020) was a Canadian actress and activist. Her acting career combined with her family name made her recognizable in Canadian film, television and national politics.

Early life

Douglas was born A ...

, and they later adopted a second daughter, Joan, who became a nurse. Actor Kiefer Sutherland

Kiefer William Sutherland (born 21 December 1966) is a British-Canadian actor and musician. He is best known for his starring role as Jack Bauer in the Fox drama series ''24 (TV series), 24'' (2001–2010, 2014), for which he won an Emmy Award ...

, son of daughter Shirley and actor Donald Sutherland

Donald McNichol Sutherland (born 17 July 1935) is a Canadian actor whose film career spans over six decades. He has been nominated for nine Golden Globe Awards, winning two for his performances in the television films '' Citizen X'' (1995) a ...

, is his grandson.

Education

Douglas startedelementary school

A primary school (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and South Africa), junior school (in Australia), elementary school or grade school (in North America and the Philippines) is a school for primary ed ...

in Winnipeg. He completed his elementary education after returning to Glasgow. He worked as a soap boy in a barber shop, rubbing lather into tough whiskers, then dropped out of high school at 13 after landing a job in a cork factory. The owner offered to pay Douglas's way through night school so that he could learn Portuguese and Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, languages that would enable him to become a cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

buyer. However, the family returned to Winnipeg when the war ended and Douglas entered the printing trades. He served a five-year apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

and worked as a Linotype operator finally acquiring his journeyman

A journeyman, journeywoman, or journeyperson is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that fie ...

's papers, but decided to return to school to pursue his ambition to become an ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

minister.

Brandon University

In 1924, the 19-year-old Douglas enrolled at Brandon College, aBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

school affiliated with McMaster University

McMaster University (McMaster or Mac) is a public research university in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The main McMaster campus is on of land near the residential neighbourhoods of Ainslie Wood and Westdale, adjacent to the Royal Botanical Ga ...

, to finish high school and study theology. During his six years at the college, he was influenced by the Social Gospel

The Social Gospel is a social movement within Protestantism that aims to apply Christian ethics to social problems, especially issues of social justice such as economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, racial tensions, slums, unclean envir ...

movement, which combined Christian principles with social reform. Liberal-minded professors at Brandon encouraged students to question their fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishi ...

religious beliefs. Christianity, they suggested, was just as concerned with the pursuit of social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals ...

as it was with the struggle for individual salvation. Douglas took a course in socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

at Brandon and studied Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empi ...

. He came first in his class during his first three years, then competed for gold medals in his last three with a newly arrived student named Stanley Knowles

Stanley Howard Knowles (June 18, 1908 – June 9, 1997) was a Canadian parliamentarian. Knowles represented the riding of Winnipeg North Centre from 1942 to 1958 on behalf of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and again from 1 ...

. Both later became ministers of religion and prominent left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

politicians. Douglas was extremely active in extracurricular activities. Among other things, he became a champion debater, wrote for the school newspaper and participated in student government winning election as Senior Stick, or president of the student body, in his final year.

Douglas financed his education at Brandon College by conducting Sunday services at several rural churches for 15 dollars a week. A shortage of ordained clergy forced smaller congregations to rely on student ministers. Douglas reported later that he preached sermons advocating social reform and helping the poor: " e Bible is like a bull fiddle ... you can play almost any tune you want on it." He added that his interest in social and economic questions led him to preach about "building a society and building institutions that would uplift mankind". He also earned money delivering entertaining monologues and poetry recitations at church suppers and service club meetings for five dollars a performance. During his second and third years at the college, he preached at a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

church in Carberry, Manitoba

Carberry is a town in southwestern Manitoba, Canada. It is situated 3 kilometres south of the Trans-Canada Highway on Highway 5 in the Municipality of North Cypress – Langford, and has a population of 1,738 people.

Economy

Carberry and the sur ...

. There he met a farmer's daughter named Irma Dempsey who would later become his wife.

MA thesis on eugenics

Douglas graduated from Brandon College in 1930 and completed his Master of Arts degree in sociology at McMaster University in 1933. His thesis, "The Problems of the Subnormal Family", endorsedeugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

. The thesis proposed a system that would have required couples seeking to marry to be certified as mentally and morally fit. Those deemed to be "subnormal", because of low intelligence, moral laxity, or venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and ora ...

would be sent to state farms or camps, while those judged to be mentally defective or incurably diseased would be sterilized.

Douglas rarely mentioned his thesis later in his life, and his government never enacted eugenics policies, though two official reviews of Saskatchewan's mental health

Mental health encompasses emotional, psychological, and social well-being, influencing cognition, perception, and behavior. It likewise determines how an individual handles Stress (biology), stress, interpersonal relationships, and decision-maki ...

system recommended such a program when he became premier and minister of health. As premier, Douglas opposed the adoption of eugenics laws. By the time Douglas took office in 1944, many people questioned eugenics due to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's embrace of it in its effort to create a "master race

The master race (german: Herrenrasse) is a pseudoscientific concept in Nazi ideology in which the putative "Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of human racial hierarchy. Members were referred to as "''Herrenmenschen''" ("master humans").

T ...

". Instead, Douglas implemented vocational training for the mentally handicapped and therapy for those suffering from mental disorder

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

s.

PhD research in Chicago

In the summer of 1931, Douglas continued his studies insociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation an ...

at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

. He never completed his PhD thesis, but was deeply disturbed by his field work in the Depression-era "jungles" or hobo

A hobo is a migrant worker in the United States. Hoboes, tramps and bums are generally regarded as related, but distinct: a hobo travels and is willing to work; a tramp travels, but avoids work if possible; and a bum neither travels nor works.

...

camps where about 75,000 transients sheltered in lean-tos venturing out by day to beg or to steal. Douglas interviewed men who once belonged to the American middle class—despondent bank clerks, lawyers and doctors. Douglas said later, "There were little soup kitchens run by the Salvation Army

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

and the churches ... In the first half-hour they'd be cleaned out. After that there was nothing ... It was impossible to describe the hopelessness." Douglas was equally disturbed that members of the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of ...

sat around quoting Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, waiting for a revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

while refusing to help the destitute. Douglas said: "That experience soured me with absolutists ... I've no patience with people who want to sit back and talk about a blueprint for society and do nothing about it."

From pulpit to politics

Two months after Douglas graduated from Brandon College, he married Irma Dempsey, and the two moved to the town ofWeyburn, Saskatchewan

Weyburn is the eleventh-largest city in Saskatchewan, Canada. The city has a population of 10,870. It is on the Souris River southeast of the provincial capital of Regina and is north from the North Dakota border in the United States. The ...

, where he became an ordained minister at the Calvary Baptist Church. Irma was 19, while Douglas was 25. With the onset of the Depression, Douglas became a social activist and joined the new Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF; french: Fédération du Commonwealth Coopératif, FCC); from 1955 the Social Democratic Party of Canada (''french: Parti social démocratique du Canada''), was a federal democratic socialistThe follo ...

(CCF) political party. He was elected to the House of Commons of Canada

The House of Commons of Canada (french: Chambre des communes du Canada) is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the bicameral legislature of Canada.

The House of Commo ...

in the 1935 federal election.

During the September 1939 special House of Commons debate on entering the war, Douglas, who had visited Nazi Germany in 1936 and was disgusted by what he saw, supported going to war against Hitler. He was not a pacifist, unlike his party's leader, J. S. Woodsworth, and stated his reasons:

Douglas and Coldwell's position was eventually adopted by the CCF National Council, but they also did not admonish Woodsworth's pacifist stand, and allowed him to put it forward in the House. Douglas assisted Woodsworth, during his leader's speech, by holding up the pages and turning them for him, even though he disagreed with him. Woodsworth had suffered a stroke earlier in the year and he needed someone to hold his notes, and Douglas still held him in very high regard, and dutifully assisted his leader.

After the outbreak of World War II, Douglas enlisted in the wartime Canadian Army

The Canadian Army (french: Armée canadienne) is the command responsible for the operational readiness of the conventional ground forces of the Canadian Armed Forces. It maintains regular forces units at bases across Canada, and is also respo ...

. He had volunteered for overseas service when a medical examination turned up his old leg problems. Douglas stayed in Canada and the Grenadiers headed for Hong Kong. If not for that ailment, he would likely have been with the regiment when its members were killed or captured at Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

in December 1941.

Premier of Saskatchewan

Despite being a federal Member of Parliament and not yet an MLA, Douglas was elected the leader of theSaskatchewan CCF

CCF can refer to:

Computing

* Confidential Consortium Framework, a free and open source blockchain infrastructure framework developed by Microsoft

* Customer Care Framework, a Microsoft product

Finance

* Credit conversion factor converts the a ...

in 1942 after successfully challenging the incumbent leader, George Hara Williams

George Hara Williams (November 17, 1894 – September 12, 1945) was a Canadian farmer activist and politician.Dale-Burnett, LisaWilliams, George (1894–1945), ''Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan, accessed February 12, 2008

Biography

Born in Binsca ...

, but did not resign from the House of Commons until 1 June 1944. He led the CCF to power in the 15 June 1944 provincial election, winning 47 of 52 seats in the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan

The Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan is the legislative chamber of the Saskatchewan Legislature in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. Bills passed by the assembly are given royal assent by the Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan, in the na ...

, and thus forming the first social democratic government in not only Canada, but all of North America. As premier, Douglas attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

The coronation of Elizabeth II took place on 2 June 1953 at Westminster Abbey in London. She acceded to the throne at the age of 25 upon the death of her father, George VI, on 6 February 1952, being proclaimed queen by her privy and executive ...

in June 1953.

Douglas and the Saskatchewan CCF then went on to win five straight majority victories in all subsequent Saskatchewan provincial elections up to 1960. Most of his government's pioneering innovations came about during its first term, including:

*the creation of the publicly owned Saskatchewan Power Corporation

Saskatchewan Power Corporation, operating as SaskPower, is the principal electric utility in Saskatchewan, Canada. Established in 1929 by the provincial government, it serves more than 538,000 customers and manages over $11.8 billion in assets. Sa ...

, successor to the Saskatchewan Electrical Power Commission, which began a long program of extending electrical service to isolated farms and villages;

*the creation of Canada's first publicly owned automotive insurance service, the Saskatchewan Government Insurance Office;

*the creation of a large number of crown corporations

A state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a government entity which is established or nationalised by the ''national government'' or ''provincial government'' by an executive order or an act of legislation in order to earn profit for the government ...

, many of which competed with existing private sector interests;

*legislation that allowed the unionization of the public service;

*a program to offer taxpayer-funded hospital care to all citizens—the first in North America.

*passage of the '' Saskatchewan Bill of Rights'', legislation that broke new ground as it protected both fundamental freedoms and equality rights against abuse not only by government actors but also on the part of powerful private institutions and persons. (''The Saskatchewan Bill of Rights'' preceded the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt ...

by the United Nations by 18 months.)

Douglas was the first head of any government in Canada to call for a constitutional bill of rights. This he did at a federal-provincial conference in Quebec City in January 1950. No one in attendance at the conference supported him in this. Ten years later, Premier Jean Lesage

Jean Lesage (; 10 June 1912 – 12 December 1980) was a Canadian lawyer and politician from Quebec. He served as the 19th premier of Quebec from 22 June 1960 to 16 June 1966. Alongside Georges-Émile Lapalme, René Lévesque and others, he is o ...

of Quebec joined with Douglas at a First Ministers' Conference in July 1960 in advocating for a constitutional bill of rights. Thus, respectable momentum was given to the idea that finally came to fruition, on 17 April 1982, with the proclamation of the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms'' (french: Charte canadienne des droits et libertés), often simply referred to as the ''Charter'' in Canada, is a bill of rights entrenched in the Constitution of Canada, forming the first part ...

''.

Thanks to a booming postwar economy and the prudent financial management of provincial treasurer Clarence Fines

Clarence Melvin Fines (August 16, 1905 – October 27, 1993) was a Canadian politician, teacher and union leader. He was provincial treasurer of the province of Saskatchewan during the Tommy Douglas era, and also served as Deputy Premier.

Bor ...

, the Douglas government slowly paid off the huge public debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt, or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit oc ...

left by the previous Liberal government, and created a budget surplus

Surplus may refer to:

* Economic surplus, one of various supplementary values

* Excess supply, a situation in which the quantity of a good or service supplied is more than the quantity demanded, and the price is above the equilibrium level determ ...

for the Saskatchewan government. Coupled with a federal government promise in 1959 to give even more tax money for medical care, this paved the way for Douglas's most notable achievement, the introduction of universal health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized ar ...

legislation in 1961.

Medicare

Douglas's number one concern was the creation of Medicare. He introduced medical insurance reform in his first term, and gradually moved the province towards universal medicare near the end of his last term. In the summer of 1962, Saskatchewan became the centre of a hard-fought struggle between the provincial government, the North American medical establishment, and the province's physicians, who brought things to a halt with the 1962Saskatchewan doctors' strike The Saskatchewan doctors' strike was a 23-day labour action exercised by medical doctors in 1962 in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan in an attempt to force the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation government of Saskatchewan to drop its program ...

. The doctors believed their best interests were not being met and feared a significant loss of income as well as government interference in medical care decisions even though Douglas agreed that his government would pay the going rate for service that doctors charged. The medical establishment claimed that Douglas would import foreign doctors to make his plan work and used racist images to try to scare the public.

Douglas is widely known as the father of Medicare, but the Saskatchewan universal program was finally launched by his successor, Woodrow Lloyd

Woodrow Stanley Lloyd (July 16, 1913 – April 7, 1972) was a Canadian politician and educator. Born in Saskatchewan in 1913, he became a teacher in the early 1930s. He worked as a teacher and school principal until 1944 and was involved with ...

, in 1962. Douglas stepped down as premier and as a member of the legislature the previous year, to lead the newly formed federal successor to the CCF, the New Democratic Party of Canada

The New Democratic Party (NDP; french: Nouveau Parti démocratique, NPD) is a federal political party in Canada. Widely described as social democratic,The party is widely described as social democratic:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* t ...

(NDP).

The success of the province's public health care program was not lost on the federal government. Another Saskatchewan politician, newly elected Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, decreed in 1958 that any province seeking to introduce a hospital plan would receive 50 cents on the dollar

Dollar is the name of more than 20 currencies. They include the Australian dollar, Brunei dollar, Canadian dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Jamaican dollar, Liberian dollar, Namibian dollar, New Taiwan dollar, New Zealand dollar, Singapore dollar, ...

from the federal government. In 1962, Diefenbaker appointed Justice Emmett Hall—also of Saskatchewan, a noted jurist and Supreme Court Justice

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight Associate Justice of the Supreme ...

—to Chair a Royal Commission on the national health system—the Royal Commission on Health Services. In 1964, Justice Hall recommended a nationwide adoption of Saskatchewan's model of public health insurance. In 1966, the Liberal minority government of Lester B. Pearson created such a program, with the federal government paying 50% of the costs and the provinces the other half. The adoption of public health care across Canada ended up being the work of three men with diverse political ideals – Douglas of the CCF, Diefenbaker of the Progressive Conservatives, and Pearson of the Liberals.

Federal NDP leader

Election

The 1958 Canadian general election was a disaster for the CCF; its caucus was reduced to eight, and party leader M. J. Coldwell lost his own seat. The CCF executive knew that their party was dying and needed radical change. The executive persuaded Coldwell to remain as leader, but the party also needed a leader in the House of Commons to replace him, because he obviously was no longer a Member of Parliament. The CCF parliamentary caucus chose Hazen Argue as its new leader in the House. During the lead-up to the 1960 CCF convention, Argue was pressing Coldwell to step down; this leadership challenge jeopardized plans for an orderly transition to the new party that was being planned by the CCF and the

The 1958 Canadian general election was a disaster for the CCF; its caucus was reduced to eight, and party leader M. J. Coldwell lost his own seat. The CCF executive knew that their party was dying and needed radical change. The executive persuaded Coldwell to remain as leader, but the party also needed a leader in the House of Commons to replace him, because he obviously was no longer a Member of Parliament. The CCF parliamentary caucus chose Hazen Argue as its new leader in the House. During the lead-up to the 1960 CCF convention, Argue was pressing Coldwell to step down; this leadership challenge jeopardized plans for an orderly transition to the new party that was being planned by the CCF and the Canadian Labour Congress

The Canadian Labour Congress, or CLC (french: Congrès du travail du Canada, link=no or ) is a national trade union centre, the central labour body in Canada to which most Canadian trade union, labour unions are affiliated.

History Formation ...

. CCF national president David Lewis – who succeeded Coldwell as president in 1958, when the national chairman and national president positions were merged – and the rest of the new party's organizers opposed Argue's manoeuvres and wanted Douglas to be the new party's first leader. To prevent their plans from being derailed, Lewis unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Argue not to force a vote at the convention on the question of the party's leadership, and there was a split between the parliamentary caucus and the party executive on the convention floor. Coldwell stepped down as leader, and Argue replaced him, becoming the party's final national leader.

As far back as 1941, Coldwell wanted Douglas to succeed him in leading the National CCF (at that time, it was obvious that Coldwell would be assuming the national leadership in the near future). When the time came for the " New Party" to form, in 1961, Coldwell pressured Douglas to run for the leadership. Coldwell did not trust Argue, and many in the CCF leadership thought that he was already having secret meetings with the Liberals with a view to a party merger. Also, Coldwell and Douglas thought Lewis would not be a viable alternative to Argue because Lewis was not likely to defeat Argue; this was partly due to Lewis' lack of a parliamentary seat but also, and likely more importantly, because his role as party disciplinarian over the years had made him many enemies, enough to potentially prevent him from winning the leadership. Douglas, after much consultation with Coldwell, Lewis, and his caucus, decided in June 1961 to reluctantly contest the leadership of the New Party. He handily defeated Argue on 3 August 1961 at the first NDP leadership convention in Ottawa, and became the new party's first leader.

Six months later, Argue crossed the floor and became a Liberal.

House of Commons, Act II

Douglas resigned from provincial politics and sought election to the House of Commons in the riding of Regina City in 1962, but was defeated by Ken More. He was later elected in aby-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election ( Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to ...

in the riding of Burnaby—Coquitlam, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

.

Re-elected as MP for that riding in the 1963

Events January

* January 1 – Bogle–Chandler case: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation scientist Dr. Gilbert Bogle and Mrs. Margaret Chandler are found dead (presumed poisoned), in bushland near the Lane Co ...

and 1965 elections, Douglas lost the redistricted seat of Burnaby—Seymour

Burnaby—Seymour was a federal electoral district in the province of British Columbia, Canada, that was represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1968 to 1979.

This riding was created in 1966 from parts of Burnaby—Coquitlam, Burna ...

in the 1968 federal election. He won a seat again in a 1969 by-election in the riding of Nanaimo—Cowichan—The Islands

Nanaimo—Cowichan—The Islands was a federal electoral district—also known as a “riding”—in British Columbia, Canada, that was represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1962 to 1979.

This riding was created in 1962 from Nanai ...

, following the death of Colin Cameron in 1968, and represented it until his retirement from electoral politics in 1979.

While the NDP did better in elections than its CCF predecessor, the party did not experience the breakthrough it had hoped for. Despite this, Douglas was greatly respected by party members and Canadians at large as the party wielded considerable influence during Lester Pearson's minority governments in the mid-1960s.

Views on homosexuality

During the 1968 Federal Election, Douglas describedhomosexuality

Homosexuality is Romance (love), romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romant ...

as a treatable illness by saying "its a mental illness nda psychiatric condition". Rather than treating it as a criminal offence with imprisonment, Douglas believed it could be treated by psychiatrists and social workers. This view of homosexuality was mainstream at the time, but has since raised questions about how historical figures are remembered.

The ''War Measures Act'', 1970

The October 1970 Quebec FLQ Crisis put Douglas and David Lewis—now a Member of Parliament—on the "hotseat", with Lewis being the only NDP MP with any roots in Quebec. He and Lewis were opposed to 16 October implementation of the ''War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (french: Loi sur les mesures de guerre; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could t ...

''.

The act, enacted previously only for wartime purposes, imposed extreme limitations on civil liberties, and gave the police and military vastly expanded powers for arresting and detaining suspects, usually with little to no evidence required. Although it was only meant to be used in Quebec, since it was federal legislation, it was in force throughout Canada. Some police services, from outside of Quebec, took advantage of it for their own purposes, which mostly had nothing even remotely related to the Quebec situation, as Lewis and Douglas suspected. During a second vote on 19 October, sixteen of the twenty members of the NDP parliamentary caucus voted against the implementation of the ''War Measures Act'' in the House of Commons and four voted with the Liberal government.

They took much grief for being the only parliamentarians to vote against it, dropping to an approval rating of seven per cent in public opinion polls. Lewis, speaking for the party at a press scrum that day: "The information we do have, showed a situation of criminal acts and criminal conspiracy in Quebec. But, there is no information that there was unintended, or apprehended, or planned insurrection, which alone, would justify invoking the ''War Measures Act''." Douglas voiced similar criticism: "The government, I submit, is using a sledgehammer to crack a peanut."

About five years later, many of the MPs who voted to implement it regretted doing so, and belatedly honoured Douglas and Lewis for their stand against it. Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield

Robert Lorne Stanfield (April 11, 1914 – December 16, 2003) was a Canadian politician who served as the 17th premier of Nova Scotia from 1956 to 1967 and the leader of the Official Opposition and leader of the federal Progressive Conservative ...

went so far as to say that, "Quite frankly, I've admired Tommy Douglas and David Lewis, and those fellows in the NDP for having the courage to vote against that, although they took a lot of abuse at the time ... I don't brood about it. I'm not proud of it."

Late career and retirement

Douglas resigned as NDP leader in 1971, but retained his seat in the House of Commons. Around the same time as theleadership convention {{Politics of Canada

In Canadian politics, a leadership convention is held by a political party when the party needs to choose a leader due to a vacancy or a challenge to the incumbent leader.

Overview

In Canada, leaders of a party generally rem ...

held to replace him, he asked the party not to buy him an elaborate parting gift. Instead, he and his friend and political mentor M. J. Coldwell were honoured by the party with the creation of the Douglas–Coldwell Foundation in 1971. He served as the NDP's energy critic under the new leader, David Lewis. He was re-elected in the riding of Nanaimo–Cowichan–The Islands in the 1972 and 1974 elections. He retired from politics in 1979 and served on the board of directors of Husky Oil, an Alberta oil and gas exploration company that had holdings in Saskatchewan.

In 1980, Douglas was awarded a Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor ...

degree ''honoris causa

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

'' by Carleton University

Carleton University is an English-language public research university in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Founded in 1942 as Carleton College, the institution originally operated as a private, non-denominational evening college to serve returning Wo ...

in Ottawa. On 22 June 1981, Douglas was appointed to the Order of Canada

The Order of Canada (french: Ordre du Canada; abbreviated as OC) is a Canadian state order and the second-highest honour for merit in the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, after the Order of Merit.

To coincide with the cen ...

as a Companion for his service as a political leader, and innovator in public policy. In 1985, he was appointed to the Saskatchewan Order of Merit

The Saskatchewan Order of Merit (french: Ordre du Mérite de la Saskatchewan) is a civilian honour for merit in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Instituted in 1985 by Lieutenant Governor Frederick Johnson, on the advice of the Cabinet u ...

and Brandon University created a students' union building in honour of Douglas and his old friend, Stanley Knowles

Stanley Howard Knowles (June 18, 1908 – June 9, 1997) was a Canadian parliamentarian. Knowles represented the riding of Winnipeg North Centre from 1942 to 1958 on behalf of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and again from 1 ...

.

In June 1984, Douglas was injured when he was struck by a bus, but he quickly recovered and on his 80th birthday he claimed to ''The Globe and Mail

''The Globe and Mail'' is a Canadian newspaper printed in five cities in western and central Canada. With a weekly readership of approximately 2 million in 2015, it is Canada's most widely read newspaper on weekdays and Saturdays, although it ...

'' that he usually walked up to five miles a day. By this point in his life his memory was beginning to slow down and he stopped accepting speaking engagements but remained active in the Douglas–Coldwell Foundation. Later that year, on 30 November, he became a member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada

The 's Privy Council for Canada (french: Conseil privé du Roi pour le Canada),) during the reign of a queen. sometimes called Majesty's Privy Council for Canada or simply the Privy Council (PC), is the full group of personal consultants to the ...

.

Douglas died of cancer on 24 February 1986, at the age of 81 in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

and was buried at Beechwood Cemetery

Beechwood Cemetery, located in the former city of Vanier in Ottawa, Ontario, is the National Cemetery of Canada. It is the final resting place for over 82,000 Canadians from all walks of life, such as important politicians like Governor Genera ...

.

In a national TV contest, conducted by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (french: Société Radio-Canada), branded as CBC/Radio-Canada, is a Canadian public broadcaster for both radio and television. It is a federal Crown corporation that receives funding from the governmen ...

(CBC) in 2004, he was crowned " Greatest Canadian" by viewers in an online vote.

Tributes

Douglas Provincial Park near Saskatchewan's

Douglas Provincial Park near Saskatchewan's Lake Diefenbaker

Lake Diefenbaker is a reservoir and bifurcation lake in Southern Saskatchewan, Canada. It was formed by the construction of Gardiner Dam and the Qu'Appelle River Dam across the South Saskatchewan and Qu'Appelle Rivers respectively. Construc ...

and Qu'Appelle River Dam

The Qu'appelle River Dam is the smaller of two embankment dams: which created Lake Diefenbaker in Saskatchewan, Canada. The larger dam is Gardiner Dam, the biggest embankment dam in Canada and one of the biggest in the world. Construction of b ...

was named after him. The statue ''The Greatest Canadian'', created by Lea Vivot, was erected in his hometown of Weyburn in September 2010 and unveiled by his grandson Kiefer Sutherland. A library located in Burnaby

Burnaby is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada. Located in the centre of the Burrard Peninsula, it neighbours the City of Vancouver to the west, the District of North Vancouver across the confluence of the Burrar ...

, British Columbia, was named in his honour and had its soft opening on 17 November 2009. Several schools have been named after him, including Tommy Douglas Collegiate

Tommy Douglas Collegiate Institute is a high school located in the Blairmore Suburban Centre district of western Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, serving students from grades 9 through 12. It is named for Tommy Douglas, the "Father of Canadian Medicare, ...

in Saskatoon, and a student housing co-op in Toronto, Campus Co-operative Residences, named one of their houses after him as well. The Tommy Douglas Secondary School in Vaughan, Ontario, Canada named in his honour opened in February 2015. Internationally the former National Labor College

The National Labor College was a college for union members and their families, union leaders and union staff in Silver Spring, Maryland. Established as a training center by the AFL–CIO in 1969 to strengthen union member education and organizin ...

in Silver Spring, Maryland

Silver Spring is a census-designated place (CDP) in southeastern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, near Washington, D.C. Although officially unincorporated, in practice it is an edge city, with a population of 81,015 at the 2020 ce ...

, was renamed the Tommy Douglas Center after its purchase by the Amalgamated Transit Union

The Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) is a labor organization in the United States and Canada that represents employees in the public transit industry. Established in 1892 as the Amalgamated Association of Street Railway Employees of America, the un ...

in 2014. In March 2019, a plaque commemorating Douglas as the "Father of Medicare" was revealed in Regina, Saskatchewan.

Artistic depiction

In the twoCBC Television

CBC Television (also known as CBC TV) is a Canadian English-language broadcast television network owned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the national public broadcaster. The network began operations on September 6, 1952. Its French- ...

mini-series

A miniseries or mini-series is a television series that tells a story in a predetermined, limited number of episodes. "Limited series" is another more recent US term which is sometimes used interchangeably. , the popularity of miniseries format ...

about Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau ( , ; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), also referred to by his initials PET, was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada from 1968 to 1979 and ...

, ''Trudeau'' and ''Trudeau II: Maverick in the Making'', Douglas is portrayed by Eric Peterson

Eric Neal Peterson (born October 2, 1946) is a Canadian stage, television, and film actor, known for his roles in three major Canadian series – '' Street Legal'' (1987–1994), '' Corner Gas'' (2004–2009), and '' This is Wonderland'' ...

. In the biography mini-series, '' Prairie Giant: The Tommy Douglas Story'', which aired on 12 and 13 March 2006, also on CBC, Douglas was played by Michael Therriault

Michael Therriault is a Canadian actor. He attended Etobicoke School of the Arts in Toronto, Sheridan College in Oakville, and was a member of the inaugural season of the Birmingham Conservatory for Classical Theatre Training in Stratford, Ontario ...

. The movie was widely derided by critics as being historically inaccurate. Particularly, the movie's portrayal of James Gardiner, premier of Saskatchewan from the late 1920s to mid-1930s, was objected to by political historians and the Gardiner family itself. In response, the CBC consulted a "third party historian" to review the film and pulled it from future broadcasts, including halting all home and educational sales. ''Prairie Giant'' was shown in Asia on the Hallmark Channel

The Hallmark Channel is an American television channel owned by Crown Media Holdings, Inc., which in turn is owned by Hallmark Cards, Inc. The channel's programming is primarily targeted at families, and features a mix of television movies a ...

on 11 and 12 June 2007.

Douglas was also the subject of a 1986 National Film Board of Canada

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB; french: Office national du film du Canada (ONF)) is Canada's public film and digital media producer and distributor. An agency of the Government of Canada, the NFB produces and distributes documentary fi ...

documentary ''Tommy Douglas: Keeper of the Flame'', which received the Gemini Award

The Gemini Awards were awards given by the Academy of Canadian Cinema & Television between 1986–2011 to recognize the achievements of Canada's television industry. The Gemini Awards are analogous to the Emmy Awards given in the United States ...

for Best Writing in a Documentary Program or Series. Douglas was mentioned in the Michael Moore

Michael Francis Moore (born April 23, 1954) is an American filmmaker, author and left-wing activist. His works frequently address the topics of globalization and capitalism.

Moore won the 2002 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature for ' ...

documentary '' Sicko'', which compared the health care system in the United States with that of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

and other countries.

Fables

"The Cream Separator" is afable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a particular m ...

, written by Douglas, which aims to explain the inherent injustices of the capitalist system as it relates to the agricultural sector by making the analogy that the upper class gets the cream, the middle class gets the whole milk, and the farmers and industrial workers get a watery substance that barely resembles milk.

He was also known for his retelling of the fable of " Mouseland", which likens the majority of voters to mice, and how they either elect black or white cats as their politicians, but never their own mice: meaning that workers and their general interests were not being served by electing wealthy politicians from the Liberal or Conservative parties (black and white cats), and that only a party from their class (mice), originally the CCF, later the NDP, could serve their interests (mice). Years later, his grandson, television actor Kiefer Sutherland, provided the introduction to a Mouseland animated video that used a Douglas Mouseland speech as its narration.Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Electoral history

Honorary degrees

Douglas received honorary degrees from several universities, including *University of Saskatchewan

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United State ...

in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Saskatoon () is the largest city in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. It straddles a bend in the South Saskatchewan River in the central region of the province. It is located along the Trans-Canada Yellowhead Highway, and has served as ...

(LLD) in 1962

*McMaster University

McMaster University (McMaster or Mac) is a public research university in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The main McMaster campus is on of land near the residential neighbourhoods of Ainslie Wood and Westdale, adjacent to the Royal Botanical Ga ...

in Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian province of Ontario. Hamilton has a population of 569,353, and its census metropolitan area, which includes Burlington and Grimsby, has a population of 785,184. The city is approximately southwest of ...

(LLD) in May 1969

* Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario

Kingston is a city in Ontario, Canada. It is located on the north-eastern end of Lake Ontario, at the beginning of the St. Lawrence River and at the mouth of the Cataraqui River (south end of the Rideau Canal). The city is midway between Tor ...

(LLD) on 27 May 1972

*University of Regina

The University of Regina is a public university, public research university located in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. Founded in 1911 as a private denominational high school of the Methodist Church of Canada, it began an association with the Unive ...

in Regina, Saskatchewan

Regina () is the capital city of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The city is the second-largest in the province, after Saskatoon, and is a commercial centre for southern Saskatchewan. As of the 2021 census, Regina had a city populatio ...

in 1978

*Carleton University

Carleton University is an English-language public research university in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Founded in 1942 as Carleton College, the institution originally operated as a private, non-denominational evening college to serve returning Wo ...

in Ottawa, Ontario

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

(LLD) in 1980

*University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

in Toronto, Ontario

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

(LLD) in June 1980

*University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia (UBC) is a public research university with campuses near Vancouver and in Kelowna, British Columbia. Established in 1908, it is British Columbia's oldest university. The university ranks among the top thr ...

in Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

, (LLD) 27 May 1981

*Trent University

Trent University is a public liberal arts university in Peterborough, Ontario, with a satellite campus in Oshawa, which serves the Regional Municipality of Durham. Trent is known for its Oxbridge college system and small class sizes.

in Peterborough, Ontario

Peterborough ( ) is a city on the Otonabee River in Ontario, Canada, about 125 kilometres (78 miles) northeast of Toronto. According to the 2021 Census, the population of the City of Peterborough was 83,651. The population of the Peterborough ...

(LLD) in 1983

Notes

Archives

There are Tommy Douglas fonds atLibrary and Archives Canada

Library and Archives Canada (LAC; french: Bibliothèque et Archives Canada) is the federal institution, tasked with acquiring, preserving, and providing accessibility to the documentary heritage of Canada. The national archive and library is t ...

and the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

Tommy Douglas and his Government 1944–1960

* * *

Douglas Provincial Park

{{DEFAULTSORT:Douglas, Tommy 1904 births 1986 deaths Scottish military personnel The Canadian Grenadier Guards soldiers Canadian Army personnel of World War II 20th-century Canadian Baptist ministers Canadian eugenicists Brandon University alumni British emigrants to Canada Canadian democratic socialists Canadian socialists Canadian Christian socialists Baptist socialists Canadian anti-poverty activists Co-operative Commonwealth Federation MPs 20th-century Canadian politicians Companions of the Order of Canada Leaders of the Saskatchewan CCF/NDP McMaster University alumni Members of the House of Commons of Canada from British Columbia Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Saskatchewan Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Members of the Saskatchewan Order of Merit NDP and CCF leaders New Democratic Party MPs People from Falkirk Politicians from Brandon, Manitoba Politicians from Winnipeg Premiers of Saskatchewan Saskatchewan Co-operative Commonwealth Federation MLAs Scottish Christian socialists Scottish emigrants to Canada Deaths from cancer in Ontario Typesetters Royal Canadian Geographical Society fellows Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Burials at Beechwood Cemetery (Ottawa)