Timothy Leary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Timothy Francis Leary (October 22, 1920 – May 31, 1996) was an American psychologist and author known for his strong advocacy of

On May 13, 1957, ''

On May 13, 1957, ''

The Concord conclusions were contested in a follow-up study on the basis of time differences monitoring the study group vs. the control group and differences between subjects re-incarcerated for parole violations and those imprisoned for new crimes. The researchers concluded that statistically only a slight improvement could be attributed to psilocybin, in contrast to the significant improvement reported by Leary and his colleagues. Rick Doblin suggested that Leary had fallen prey to the Halo Effect, skewing the results and clinical conclusions. Doblin further accused Leary of lacking "a higher standard" or "highest ethical standards in order to regain the trust of regulators". Ralph Metzner rebuked Doblin for these assertions: "In my opinion, the existing accepted standards of honesty and truthfulness are perfectly adequate. We have those standards, not to curry favor with regulators, but because it is the agreement within the scientific community that observations should be reported accurately and completely. There is no proof in any of this re-analysis that Leary unethically manipulated his data."

Leary and Alpert founded the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF) in 1962 in

The Concord conclusions were contested in a follow-up study on the basis of time differences monitoring the study group vs. the control group and differences between subjects re-incarcerated for parole violations and those imprisoned for new crimes. The researchers concluded that statistically only a slight improvement could be attributed to psilocybin, in contrast to the significant improvement reported by Leary and his colleagues. Rick Doblin suggested that Leary had fallen prey to the Halo Effect, skewing the results and clinical conclusions. Doblin further accused Leary of lacking "a higher standard" or "highest ethical standards in order to regain the trust of regulators". Ralph Metzner rebuked Doblin for these assertions: "In my opinion, the existing accepted standards of honesty and truthfulness are perfectly adequate. We have those standards, not to curry favor with regulators, but because it is the agreement within the scientific community that observations should be reported accurately and completely. There is no proof in any of this re-analysis that Leary unethically manipulated his data."

Leary and Alpert founded the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF) in 1962 in

"Tim Leary and Ovum - A Visit to Castalia with Ovum"

, ''Chez Jim/Ovum'', March 3, 2003 The Castalia group's journal was the ''Psychedelic Review''. The core group at Millbrook wanted to cultivate the divinity within each person and regularly joined LSD sessions facilitated by Leary. The Castalia Foundation also hosted non-drug weekend retreats for meditation,

"Transmissions from The Timothy Leary Papers: Evolution of the "Psychedelic" Show"

, New York Public Library, June 4, 2012 Leary later wrote:

"Jean McCreedy and Psychedelic Prayers"

, ''Chez Jim/Ovum'', March 3, 2003 Woodruff helped Leary prepare weekend multimedia workshops simulating the psychedelic experience, which were presented around the East Coast. In September 1966, Leary said in a ''

"Chemist Who Sought to Bring LSD to the World, Dies at 75"

, ''

"Turn On, Tune In, Drop by the Archives: Timothy Leary at the N.Y.P.L."

, ''

''Start Your Own Religion''

to encourage people to do so. Leary was invited to attend the January 14, 1967 Human Be-In by Michael Bowen, the primary organizer of the event, a gathering of 30,000

Leary's first run-in with the law came on December 23, 1965, when he was arrested for marijuana possession. Leary took his two children, Jack and Susan, and his girlfriend Rosemary Woodruff to Mexico for an extended stay to write a book. On their return from Mexico to the United States, a

Leary's first run-in with the law came on December 23, 1965, when he was arrested for marijuana possession. Leary took his two children, Jack and Susan, and his girlfriend Rosemary Woodruff to Mexico for an extended stay to write a book. On their return from Mexico to the United States, a

Leary's space colonization plan evolved over the years. Initially, 5,000 of Earth's most virile and intelligent individuals would be launched on a vessel (Starseed 1) equipped with luxurious amenities. This idea was inspired by musician

Leary's space colonization plan evolved over the years. Initially, 5,000 of Earth's most virile and intelligent individuals would be launched on a vessel (Starseed 1) equipped with luxurious amenities. This idea was inspired by musician

In January 1995, Leary was diagnosed with inoperable

In January 1995, Leary was diagnosed with inoperable  Leary was reportedly excited for a number of years by the possibility of freezing his body in cryonic suspension, and he announced in September 1988 that he had signed up with

Leary was reportedly excited for a number of years by the possibility of freezing his body in cryonic suspension, and he announced in September 1988 that he had signed up with

In the 1968 '' Dragnet'' episode "The Big Prophet",

In the 1968 '' Dragnet'' episode "The Big Prophet",

TimothyLeary.info – biography, archives, links, and more

Lectures from the Leary Archive in audio format

* *

"Unlimited Virtual Realities for Everyone!"

,

Timothy Leary papers, 1910-2009

held by the Manuscripts and Archives Division,

Image of Timothy Leary and his wife, Rosemary Woodruff holding a news conference in Los Angeles, California, 1969.

psychedelic drug

Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary states of consciousness (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips").Pollan, Michael (2018). ''How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science o ...

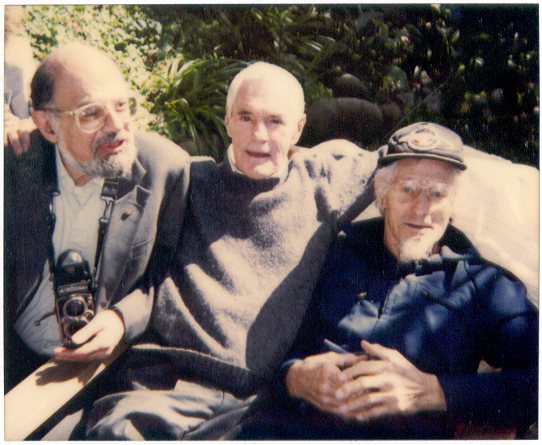

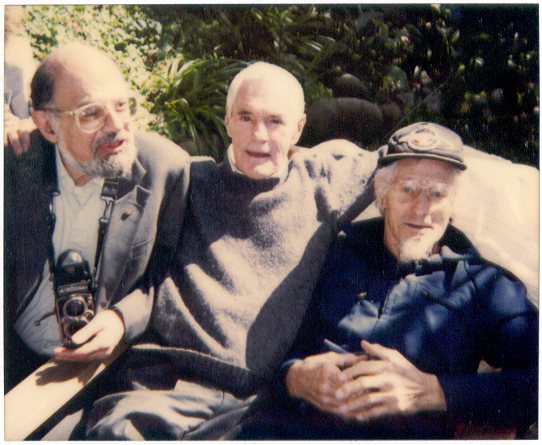

s. Evaluations of Leary are polarized, ranging from bold oracle to publicity hound. He was "a hero of American consciousness", according to Allen Ginsberg

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (; June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) was an American poet and writer. As a student at Columbia University in the 1940s, he began friendships with William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, forming the core of the Beat Gener ...

, and Tom Robbins

Thomas Eugene Robbins (born July 22, 1932) is a best-selling and prolific American novelist. His most notable works are "seriocomedies" (also known as "comedy drama"), such as ''Even Cowgirls Get the Blues''. Tom Robbins has lived in La Conner ...

called him a "brave neuronaut".

As a clinical psychologist at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, Leary founded the Harvard Psilocybin Project after a revealing experience with magic mushrooms in Mexico. He led the Project from 1960 to 1962, testing the therapeutic effects of lysergic acid diethylamide

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), also known colloquially as acid, is a potent psychedelic drug. Effects typically include intensified thoughts, emotions, and sensory perception. At sufficiently high dosages LSD manifests primarily mental, vi ...

(LSD) and psilocybin, which were legal in the U.S., in the Concord Prison Experiment and the Marsh Chapel Experiment. Other Harvard faculty questioned his research's scientific legitimacy and ethics because he took psychedelics along with his subjects and allegedly pressured students to join in. One of Leary's students, Robert Thurman, has denied that Leary pressured unwilling students. Harvard fired Leary and his colleague Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass

Ram Dass (born Richard Alpert; April 6, 1931 – December 22, 2019), also known as Baba Ram Dass, was an American spiritual teacher, guru of modern yoga, psychologist, and author. His best-selling 1971 book '' Be Here Now'', which has been ...

) in May 1963. Many people only learned of psychedelics after the Harvard scandal.

Leary believed that LSD showed potential for therapeutic use in psychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders. These include various maladaptations related to mood, behaviour, cognition, and perceptions. See glossary of psychiatry.

Initial p ...

. He took LSD and developed a philosophy of mind expansion and personal truth through LSD. After leaving Harvard, he continued to publicly promote psychedelic drugs and became a well-known figure of the counterculture of the 1960s

The counterculture of the 1960s was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon that developed throughout much of the Western world in the 1960s and has been ongoing to the present day. The aggregate movement gained momentum as the civil rights mo ...

. He popularized catchphrase

A catchphrase (alternatively spelled catch phrase) is a phrase or expression recognized by its repeated utterance. Such phrases often originate in popular culture and in the arts, and typically spread through word of mouth and a variety of mass ...

s that promoted his philosophy, such as " turn on, tune in, drop out", " set and setting", and " think for yourself and question authority". He also wrote and spoke frequently about transhumanist concepts of space migration, intelligence increase, and life extension

Life extension is the concept of extending the human lifespan, either modestly through improvements in medicine or dramatically by increasing the maximum lifespan beyond its generally-settled limit of 125 years.

Several researchers in the area ...

(SMI²LE). Leary developed the eight-circuit model of consciousness in his book ''Exo-Psychology'' (1977) and gave lectures, occasionally calling himself a "performing philosopher".

During the 1960s and 1970s, Leary was arrested 36 times. President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

once called him "the most dangerous man in America".

Early life and education

Leary was born inSpringfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, th ...

, an only child

An only child is a person with no siblings, by birth or adoption.

Children who have half-siblings, step-siblings, or have never met their siblings, either living at the same house or at a different house—especially those who were born consider ...

in an Irish Catholic household. His father, Timothy "Tote" Leary, was a dentist who left his wife Abigail Ferris when Leary was 14. He graduated from Classical High School in Springfield.

Leary attended the College of the Holy Cross

The College of the Holy Cross is a private, Jesuit liberal arts college in Worcester, Massachusetts, about 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston. Founded in 1843, Holy Cross is the oldest Catholic college in New England and one of the oldest in ...

in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 census, making it the second- most populous city in New England after ...

, from 1938 to 1940. Under pressure from his father, he became a cadet in the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

. In the first months as a "plebe", he received numerous demerits for rule infractions and then got into serious trouble for failing to report rule breaking by cadets he supervised. He was also accused of going on a drinking binge and failing to admit it, and was asked by the Honor Committee to resign. He refused and was "silenced"—that is, shunned by fellow cadets. He was acquitted by a court-martial, but the silencing continued, as well as the onslaught of demerits for small rule infractions. In his sophomore year his mother appealed to a family friend, United States Senator David I. Walsh, head of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, who investigated personally. The Honor Committee quietly revised its position and announced that it would abide by the court-martial verdict. Leary then resigned and was honorably discharged by the Army. About 50 years later he said that it was "the only fair trial I've had in a court of law".

To his family's chagrin, Leary transferred to the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, or Bama) is a public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of Alabama is the oldest and largest of the publ ...

in late 1941 because it admitted him so expeditiously. He enrolled in the university's ROTC

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in al ...

program, maintained top grades, and began to cultivate academic interests in psychology

Psychology is the science, scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immens ...

(under the aegis of the Middlebury and Harvard-educated Donald Ramsdell) and biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

. Leary was expelled a year later for spending a night in the female dormitory and lost his student deferment in the midst of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Leary was drafted into the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

and received basic training

Military recruit training, commonly known as basic training or boot camp, refers to the initial instruction of new military personnel. It is a physically and psychologically intensive process, which resocializes its subjects for the unique deman ...

at Fort Eustis in 1943. He remained in the non-commissioned officer track while enrolled in the psychology subsection of the Army Specialized Training Program, including three months of study at Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private research university in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll in 1789 as Georgetown College, the university has grown to comprise eleven undergraduate and graduate ...

and six months at Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best pub ...

.

With limited need for officers late in the war, Leary was briefly assigned as a private first class

Private first class (french: Soldat de 1 classe; es, Soldado de primera) is a military rank held by junior enlisted personnel in a number of armed forces.

French speaking countries

In France and other French speaking countries, the rank (; ...

to the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vas ...

-bound 2d Combat Cargo Group (which he later characterized as "a suicide command ... whose main mission, as far as I could see, was to eliminate the entire civilian branch of American aviation from post-war rivalry") at Syracuse Army Air Base

Hancock Field Air National Guard Base is a United States Air Force base, co-located with Syracuse Hancock International Airport. It is located north-northeast of Syracuse, New York, at 6001 East Molloy Road, Mattydale, NY 13211.

The installation ...

in Mattydale, New York. After a fateful reunion with Ramsdell (who was assigned to Deshon General Hospital in Butler, Pennsylvania

Butler is a city and the county seat of Butler County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located north of Pittsburgh and is part of the Greater Pittsburgh region. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 13,502.

History

Butler was n ...

, as chief psychologist) in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, he was promoted to corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

and reassigned to his mentor's command as a staff psychometrician

Psychometrics is a field of study within psychology concerned with the theory and technique of measurement. Psychometrics generally refers to specialized fields within psychology and education devoted to testing, measurement, assessment, an ...

. He remained in Deshon's deaf rehabilitation clinic for the remainder of the war. While stationed in Butler, Leary courted Marianne Busch; they married in April 1945. Leary was discharged at the rank of sergeant

Sergeant ( abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other ...

in January 1946, having earned such standard decorations as the Good Conduct Medal, the American Defense Service Medal

The American Defense Service Medal was a military award of the United States Armed Forces, established by , by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on June 28, 1941.

The medal was intended to recognize those military service members who had served ...

, the American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perfo ...

, and the World War II Victory Medal.

As the war concluded, Leary was reinstated at the University of Alabama and received credit for his Ohio State psychology coursework. He completed his degree via correspondence courses and graduated in August 1945.

After receiving his undergraduate degree, Leary pursued an academic career. In 1946, he received a M.S.

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast to ...

in psychology at the State College of Washington in Pullman, where he studied under educational psychologist Lee Cronbach. His M.S. thesis was on clinical applications of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

In 1947, Marianne gave birth to their first child, Susan. A son, Jack, arrived two years later. In 1950, Leary received a Ph.D. in clinical psychology

Clinical psychology is an integration of social science, theory, and clinical knowledge for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and relieving psychologically based distress or dysfunction and to promote subjective well-being and persona ...

from the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant un ...

. In the postwar era, Leary was galvanized by the objectivity of modern physics

Modern physics is a branch of physics that developed in the early 20th century and onward or branches greatly influenced by early 20th century physics. Notable branches of modern physics include quantum mechanics, special relativity and general ...

; his doctoral dissertation (''The Social Dimensions of Personality: Group Process and Structure'') approached group therapy

Group psychotherapy or group therapy is a form of psychotherapy in which one or more therapists treat a small group of clients together as a group. The term can legitimately refer to any form of psychotherapy when delivered in a group format, i ...

as a "psychlotron" from which behavioral characteristics could be derived and quantified in a manner analogous to the periodic table

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of the (chemical) elements, is a rows and columns arrangement of the chemical elements. It is widely used in chemistry, physics, and other sciences, and is generally seen as an icon of ch ...

, foreshadowing his later development of the interpersonal circumplex.

Leary stayed on in the Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Gov ...

as an assistant clinical professor of medical psychology at the University of California, San Francisco

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is a public land-grant research university in San Francisco, California. It is part of the University of California system and is dedicated entirely to health science and life science. It ...

; concurrently, he co-founded Kaiser Hospital's psychology department in Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the ...

, and maintained a private consultancy. In 1952, the Leary family spent a year in Spain, subsisting on a research grant. According to Berkeley colleague Marv Freedman, "Something had been stirred in him in terms of breaking out of being another cog in society."

Leary's marriage was strained by infidelity and mutual alcohol abuse

Alcohol abuse encompasses a spectrum of unhealthy alcohol drinking behaviors, ranging from binge drinking to alcohol dependence, in extreme cases resulting in health problems for individuals and large scale social problems such as alcohol-rela ...

. Marianne eventually died by suicide in 1955, leaving him to raise their son and daughter alone. He described himself during this period as "an anonymous institutional employee who drove to work each morning in a long line of commuter cars and drove home each night and drank martinis ... like several million middle-class, liberal, intellectual robots".

From 1954 or 1955 to 1958, Leary directed psychiatric research at the Kaiser Family Foundation

KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), also known as The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, is an American non-profit organization, headquartered in San Francisco, California. It prefers KFF since its legal name can cause confusion as it is no longer ...

. In 1957, he published ''The Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality'', which the ''Annual Review of Psychology

The ''Annual Review of Psychology'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes review articles about psychology. First published in 1950, its longest-serving editors have been Mark Rosenzweig (1969–1994) and Susan Fiske (2000&ndas ...

'' called the "most important book on psychotherapy of the year".

In 1958 the National Institute of Mental Health terminated Leary's research grant after he failed to meet with a NIMH investigator. Leary and his children relocated to Europe, where he attempted to write his next book while subsisting on small grants and insurance policies. His stay in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

was unproductive and indigent, prompting a return to academe. In late 1959 he started as a lecturer in clinical psychology at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

at the behest of Frank Barron (a colleague from Berkeley) and David McClelland

David Clarence McClelland (May 20, 1917 – March 27, 1998) was an American psychologist, noted for his work on motivation Need Theory. He published a number of works between the 1950s and the 1990s and developed new scoring systems for t ...

. Leary and his children lived in Newton, Massachusetts

Newton is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is approximately west of downtown Boston. Newton resembles a patchwork of thirteen villages, without a city center. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, the population of ...

. In addition to teaching, Leary was affiliated with the Harvard Center for Research in Personality under McClelland. He oversaw the Harvard Psilocybin Project and conducted experiments in conjunction with assistant professor Richard Alpert. In 1963, Leary was terminated for failing to attend scheduled class lectures, though he maintained that he had met his teaching obligations. The decision to dismiss him may have been influenced by his promotion of psychedelic drug use among Harvard students and faculty. The drugs were legal at the time.

His work in academic psychology expanded on the research of Harry Stack Sullivan and Karen Horney

Karen Horney (; ; 16 September 1885 – 4 December 1952) was a German psychoanalyst who practised in the United States during her later career. Her theories questioned some traditional Freudian views. This was particularly true of her theories ...

, which sought to better understand interpersonal processes to help diagnose disorders. Leary's dissertation developed the interpersonal circumplex model, later published in ''The Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality''. The book demonstrated how psychologists could use Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) is a standardized psychometric test of adult personality and psychopathology. Psychologists and other mental health professionals use various versions of the MMPI to help develop treatmen ...

(MMPI) scores to predict how respondents might react to various interpersonal situations. Leary's research was an important harbinger of transactional analysis, directly prefiguring the popular work of Eric Berne

Eric Berne (May 10, 1910 – July 15, 1970) was a Canadian-born psychiatrist who created the theory of transactional analysis as a way of explaining human behavior.

Berne's theory of transactional analysis was based on the ideas of Freud ...

.

Psychedelic experiments and experiences

Mexico and Harvard research (1957–1963)

Introduction to psychedelic mushrooms

On May 13, 1957, ''

On May 13, 1957, ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

'' magazine published an article by R. Gordon Wasson about the use of psilocybin mushrooms in religious rites of the indigenous Mazatec people of Mexico. Anthony Russo, a colleague of Leary's, had experimented with psychedelic

Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary states of consciousness (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips").Pollan, Michael (2018). ''How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science o ...

'' Psilocybe mexicana'' mushrooms on a trip to Mexico and told Leary about it. In August 1960, Leary traveled to Cuernavaca, Mexico, with Russo and consumed psilocybin mushrooms for the first time, an experience that drastically altered the course of his life.''Ram Dass Fierce Grace'', 2001, Zeitgeist Video In 1965, Leary said that he had "learned more about ... isbrain and its possibilities ... ndmore about psychology in the five hours after taking these mushrooms than ... in the preceding 15 years of studying and doing research".

Back at Harvard, Leary and his associates (notably Alpert) began a research program known as the Harvard Psilocybin Project. The goal was to analyze the effects of psilocybin on human subjects (first prisoners, and later Andover Newton Theological Seminary students) from a synthesized version of the drug, one of two active compounds found in a wide variety of hallucinogenic mushrooms, including '' Psilocybe mexicana''. Psilocybin was produced in a process developed by Albert Hofmann

Albert Hofmann (11 January 1906 – 29 April 2008) was a Swiss chemist known for being the first to synthesize, ingest, and learn of the psychedelic effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Hofmann's team also isolated, named and synthesi ...

of Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, who was famous for synthesizing LSD.

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (; June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) was an American poet and writer. As a student at Columbia University in the 1940s, he began friendships with William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, forming the core of the Beat Gener ...

heard about the Harvard research project and asked to join. Leary was inspired by Ginsberg's enthusiasm, and the two shared an optimism that psychedelics could help people discover a higher level of consciousness. They began introducing psychedelics to intellectuals and artists including Jack Kerouac

Jean-Louis Lebris de Kérouac (; March 12, 1922 – October 21, 1969), known as Jack Kerouac, was an American novelist and poet who, alongside William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, was a pioneer of the Beat Generation.

Of French-Canadian an ...

, Maynard Ferguson

Walter Maynard Ferguson CM (May 4, 1928 – August 23, 2006) was a Canadian jazz trumpeter and bandleader. He came to prominence in Stan Kenton's orchestra before forming his own big band in 1957. He was noted for his bands, which often serv ...

, Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus Jr. (April 22, 1922 – January 5, 1979) was an American jazz upright bassist, pianist, composer, bandleader, and author. A major proponent of collective improvisation, he is considered to be one of the greatest jazz musicians an ...

and Charles Olson.

Concord Prison Experiment

Leary argued thatpsychedelic substance

Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary states of consciousness (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips").Pollan, Michael (2018). ''How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science o ...

s—in proper doses, a stable setting, and under the guidance of psychologists—could benefit behavior in ways not easily obtained by regular therapy. He experimented in treating alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

and reforming criminals, and many of his subjects said they had profound mystical and spiritual experiences that permanently improved their lives.

The Concord Prison Experiment evaluated the use of psilocybin and psychotherapy in the rehabilitation of released prisoners. Thirty-six prisoners were reported to have repented and sworn off criminality after Leary and his associates guided them through the psychedelic experience. The overall recidivism

Recidivism (; from ''recidive'' and ''ism'', from Latin ''recidīvus'' "recurring", from ''re-'' "back" and ''cadō'' "I fall") is the act of a person repeating an undesirable behavior after they have experienced negative consequences of th ...

rate for American prisoners was 60%, whereas the rate for those in Leary's project reportedly dropped to 20%. The experimenters concluded that long-term reduction in criminal recidivism could be effected with a combination of psilocybin-assisted group psychotherapy (inside the prison) along with a comprehensive post-release follow-up support program modeled on Alcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is an international mutual aid fellowship of alcoholics dedicated to abstinence-based recovery from alcoholism through its spiritually-inclined Twelve Step program. Following its Twelve Traditions, AA is non-professi ...

.

Dissension over studies

The Concord conclusions were contested in a follow-up study on the basis of time differences monitoring the study group vs. the control group and differences between subjects re-incarcerated for parole violations and those imprisoned for new crimes. The researchers concluded that statistically only a slight improvement could be attributed to psilocybin, in contrast to the significant improvement reported by Leary and his colleagues. Rick Doblin suggested that Leary had fallen prey to the Halo Effect, skewing the results and clinical conclusions. Doblin further accused Leary of lacking "a higher standard" or "highest ethical standards in order to regain the trust of regulators". Ralph Metzner rebuked Doblin for these assertions: "In my opinion, the existing accepted standards of honesty and truthfulness are perfectly adequate. We have those standards, not to curry favor with regulators, but because it is the agreement within the scientific community that observations should be reported accurately and completely. There is no proof in any of this re-analysis that Leary unethically manipulated his data."

Leary and Alpert founded the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF) in 1962 in

The Concord conclusions were contested in a follow-up study on the basis of time differences monitoring the study group vs. the control group and differences between subjects re-incarcerated for parole violations and those imprisoned for new crimes. The researchers concluded that statistically only a slight improvement could be attributed to psilocybin, in contrast to the significant improvement reported by Leary and his colleagues. Rick Doblin suggested that Leary had fallen prey to the Halo Effect, skewing the results and clinical conclusions. Doblin further accused Leary of lacking "a higher standard" or "highest ethical standards in order to regain the trust of regulators". Ralph Metzner rebuked Doblin for these assertions: "In my opinion, the existing accepted standards of honesty and truthfulness are perfectly adequate. We have those standards, not to curry favor with regulators, but because it is the agreement within the scientific community that observations should be reported accurately and completely. There is no proof in any of this re-analysis that Leary unethically manipulated his data."

Leary and Alpert founded the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF) in 1962 in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, to carry out studies in the religious use of psychedelic drugs. This was run by Lisa Bieberman (now known as Licia Kuenning), a friend of Leary. ''The Harvard Crimson

''The Harvard Crimson'' is the student newspaper of Harvard University and was founded in 1873. Run entirely by Harvard College undergraduates, it served for many years as the only daily newspaper in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Beginning in the f ...

'' called her a "disciple" who ran a Psychedelic Information Center out of her home and published a national LSD newspaper. That publication was actually Leary and Alpert's journal ''Psychedelic Review'' and Bieberman (a graduate of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University—also known as the Harvard Radcliffe Institute—is a part of Harvard University that fosters interdisciplinary research across the humanities, sciences, social sciences, arts, a ...

at Harvard, who had volunteered for Leary as a student) was its circulation manager. Leary's and Alpert's research attracted so much attention that many who wanted to participate in the experiments had to be turned away. To satisfy the curiosity of those who were turned away, a black market for psychedelics sprang up near the Harvard campus.

Firing by Harvard

Other professors in the Harvard Center for Research in Personality raised concerns about the experiments' legitimacy and safety. Leary and Alpert taught a class that was required for graduation and colleagues felt they were abusing their power by pressuring graduate students to take hallucinogens in the experiments. Leary and Alpert also went against policy by giving psychedelics to undergraduate students and did not select participants throughrandom sampling

In statistics, quality assurance, and survey methodology, sampling is the selection of a subset (a statistical sample) of individuals from within a statistical population to estimate characteristics of the whole population. Statisticians attemp ...

. It was also ethically questionable that the researchers sometimes took hallucinogens along with the subjects they were studying. These concerns were printed in ''The Harvard Crimson

''The Harvard Crimson'' is the student newspaper of Harvard University and was founded in 1873. Run entirely by Harvard College undergraduates, it served for many years as the only daily newspaper in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Beginning in the f ...

'', leading the university to halt the experiments. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health is a governmental agency of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts with various responsibilities related to public health within that state. It is headquartered in Boston and headed by Commissioner Monica ...

launched an investigation that was later dropped but the university eventually fired Leary and Alpert.

According to Andrew Weil, Leary (who held an untenured teaching appointment) was fired for missing his scheduled lectures, while Alpert (a tenure-track assistant professor) was dismissed for allegedly giving an undergraduate psilocybin in an off-campus apartment. Harvard President Nathan Pusey

Nathan Marsh Pusey (; April 4, 1907 – November 14, 2001) was an American academic. Originally from Council Bluffs, Iowa, Pusey won a scholarship to Harvard University out of high school and went on to earn bachelor's, master's, and doctor ...

released a statement on May 27, 1963, reporting that Leary had left campus without authorization and "failed to keep his classroom appointments". His salary was terminated on April 30, 1963.''New York Times'', December 3, 1966, p. 25

Millbrook and psychedelic counterculture (1963–1967)

Leary's psychedelic experimentation attracted the attention of three heirs to the Mellon fortune, siblings Peggy, Billy, and Tommy Hitchcock. In 1963, they gave Leary and his associates access to a sprawling 64-room mansion on an estate in Millbrook, New York, where they continued their psychedelic sessions. Peggy directed the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF)'s New York branch, and Billy rented the estate to IFIF. Leary and Alpert set up a communal group with former Psilocybin Project members at theHitchcock Estate

The Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, New York is a historic mansion and surrounding grounds, associated with Timothy Leary and the psychedelic movement. It is often referred to in this context as just Millbrook; it is also sometimes called by its o ...

(commonly known as "Millbrook"). One of the IFIF's founding board members, Paul Lee, a Harvard theologian, a participant at Marsh Chapel

Marsh Chapel is a building on the campus of Boston University used as the official place of worship of the school. It was named for Daniel L. Marsh, a former president of BU and a Methodist minister. The building is Gothic in style.

While Met ...

and a member of the Leary circle, said of the group's formation:

The IFIF was reconstituted as the Castalia Foundation after the intellectual colony in Hermann Hesse

Hermann Karl Hesse (; 2 July 1877 – 9 August 1962) was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. His best-known works include '' Demian'', '' Steppenwolf'', '' Siddhartha'', and '' The Glass Bead Game'', each of which explores an individual ...

's 1943 novel '' The Glass Bead Game''.Chevallier, Jim"Tim Leary and Ovum - A Visit to Castalia with Ovum"

, ''Chez Jim/Ovum'', March 3, 2003 The Castalia group's journal was the ''Psychedelic Review''. The core group at Millbrook wanted to cultivate the divinity within each person and regularly joined LSD sessions facilitated by Leary. The Castalia Foundation also hosted non-drug weekend retreats for meditation,

yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciou ...

, and group therapy.Ulrich, Jennifer"Transmissions from The Timothy Leary Papers: Evolution of the "Psychedelic" Show"

, New York Public Library, June 4, 2012 Leary later wrote:

We saw ourselves as anthropologists from the 21st century inhabiting a time module set somewhere in the dark ages of the 1960s. On this space colony we were attempting to create a newpaganism Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...and a new dedication to life as art.

Lucy Sante

Lucy Sante (formerly Luc Sante; born May 25, 1954) is a Belgium-born American writer, critic, and artist. She is a frequent contributor to ''The New York Review of Books''. Her books include '' Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York'' (1991) ...

of ''The New York Times'' later described the Millbrook estate as:

the headquarters of Leary and gang for the better part of five years, a period filled with endless parties, epiphanies and breakdowns, emotional dramas of all sizes, and numerous raids and arrests, many of them on flimsy charges concocted by the local assistant district attorney, G. Gordon Liddy.Others contest the characterization of Millbrook as a party house. In '' The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test'',

Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

portrays Leary as using psychedelics only for research, not recreation. When Ken Kesey

Ken Elton Kesey (September 17, 1935 – November 10, 2001) was an American novelist, essayist and countercultural figure. He considered himself a link between the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s.

Kesey was born in ...

's Merry Pranksters visited the estate, they received a frosty reception. Leary had the flu and did not play host. After a private meeting with Kesey and Ken Babbs

Ken Babbs (born January 14, 1936) is a famous Merry Prankster who became one of the psychedelic leaders of the 1960s. He along with best friend and Prankster leader, Ken Kesey wrote the book '' Last Go Round''. Babbs is best known for his par ...

in his room, he promised to remain an ally in the years ahead.

In 1964, Leary, Alpert, and Ralph Metzner coauthored '' The Psychedelic Experience'', based on the '' Tibetan Book of the Dead''. In it, they wrote:

A psychedelic experience is a journey to new realms of consciousness. The scope and content of the experience is limitless, but its characteristic features are the transcendence of verbal concepts, ofLeary married model Birgitte Caroline "Nena" von Schlebrügge in 1964 at Millbrook. Both Nena and her brother Bjorn were friends of the Hitchcocks. D. A. Pennebaker, also a Hitchcock friend, and cinematographer Nicholas Proferes documented the event in the short film ''You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You''.spacetime In physics, spacetime is a mathematical model that combines the three dimensions of space and one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional manifold. Spacetime diagrams can be used to visualize relativistic effects, such as why differ ...dimensions, and of the ego or identity. Such experiences of enlarged consciousness can occur in a variety of ways: sensory deprivation, yoga exercises, disciplined meditation, religious or aesthetic ecstasies, or spontaneously. Most recently they have become available to anyone through the ingestion of psychedelic drugs such as LSD, psilocybin,mescaline Mescaline or mescalin (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a naturally occurring psychedelic protoalkaloid of the substituted phenethylamine class, known for its hallucinogenic effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin. Biological ...,DMT ''N'',''N''-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT or ''N'',''N''-DMT, SPL026) is a substituted tryptamine that occurs in many plants and animals, including human beings, and which is both a derivative and a structural analog of tryptamine. It is used as a ..., etc. Of course, the drug does not produce the transcendent experience. It merely acts as a chemical key—it opens the mind, frees the nervous system of its ordinary patterns and structures.

Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus Jr. (April 22, 1922 – January 5, 1979) was an American jazz upright bassist, pianist, composer, bandleader, and author. A major proponent of collective improvisation, he is considered to be one of the greatest jazz musicians an ...

played piano. The marriage lasted a year before von Schlebrügge divorced Leary in 1965. She married Indo-Tibetan Buddhist scholar and ex-monk Robert Thurman in 1967 and gave birth to Ganden Thurman that same year. Actress Uma Thurman, her second child, was born in 1970.

Leary met Rosemary Woodruff in 1965 at a New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

art exhibit, and invited her to Millbrook. After moving in, she co-edited the manuscript for Leary's 1966 book ''Psychedelic Prayers: And Other Meditations'' with Ralph Metzner and Michael Horowitz. The poems in the book were inspired by the ''Tao Te Ching

The ''Tao Te Ching'' (, ; ) is a Chinese classic text written around 400 BC and traditionally credited to the sage Laozi, though the text's authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated. The oldest excavated portion ...

'', and meant to be used as an aid to LSD trips.Chevallier, Jim"Jean McCreedy and Psychedelic Prayers"

, ''Chez Jim/Ovum'', March 3, 2003 Woodruff helped Leary prepare weekend multimedia workshops simulating the psychedelic experience, which were presented around the East Coast. In September 1966, Leary said in a ''

Playboy

''Playboy'' is an American men's Lifestyle magazine, lifestyle and entertainment magazine, formerly in print and currently online. It was founded in Chicago in 1953, by Hugh Hefner and his associates, and funded in part by a $1,000 loan from H ...

'' magazine interview that LSD could cure homosexuality. According to him, a lesbian became heterosexual after using the drug. Like most of the psychiatric field, he later decided that homosexuality was not an illness.

By 1966, use of psychedelics by America's youth had reached such proportions that serious concern about the drugs and their effect on American culture was expressed in the national press and halls of government. In response to this concern, Senator Thomas Dodd convened Senate subcommittee hearings to try to better understand the drug-use phenomenon, eventually with the intention of "stamping out" such usage by criminalizing it. Leary was one of several expert witnesses called to testify at these hearings. In his testimony, Leary said, "the challenge of the psychedelic chemicals is not just how to control them, but how to use them." He implored the subcommittee not to criminalize psychedelic drug use, which he felt would only serve to exponentially increase its usage among America's youth while removing the safeguards that controlled "set and setting" provided. When subcommittee member Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

asked Leary whether LSD usage was "extremely dangerous", Leary replied, "Sir, the motorcar is dangerous if used improperly...Human stupidity and ignorance is the only danger human beings face in this world." To conclude his testimony, Leary suggested that legislation be enacted that would require LSD users to be adults who were competently trained and licensed, so that such individuals could use LSD "for serious purposes, such as spiritual growth, pursuit of knowledge, or their own personal development." He presciently noted that without such licensing, the U.S. would face "another era of prohibition." Leary's testimony proved ineffective; on October 6, 1966, just months after the subcommittee hearings, LSD was banned in California, and by October 1968, it was banned nationwide by the Staggers-Dodd Bill.

In 1966, Folkways Records

Folkways Records was a record label founded by Moses Asch that documented folk, world, and children's music. It was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution in 1987 and is now part of Smithsonian Folkways.

History

The Folkways Records & Service ...

recorded Leary reading from his book ''The Psychedelic Experience'', and released the album ''The Psychedelic Experience: Readings from the Book "The Psychedelic Experience. A Manual Based on the Tibetan...".''

On September 19, 1966, Leary reorganized the IFIF/Castalia Foundation under the name the League for Spiritual Discovery, a religion with LSD as its holy sacrament

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the rea ...

, in part as an unsuccessful attempt to maintain legal status for the use of LSD and other psychedelics for the religion's adherents, based on a "freedom of religion" argument. Leary incorporated the League for Spiritual Discovery as a religious organization in New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. sta ...

, and its dogma was based on Leary's mantra: "drop out, turn on, tune in". ( The Brotherhood of Eternal Love later considered Leary its spiritual leader, but it did not develop out of the IFIF.) Nicholas Sand, the clandestine chemist for the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, followed Leary to Millbrook and joined the League for Spiritual Discovery. Sand was designated the "alchemist" of the new religion.Grimesmay, William"Chemist Who Sought to Bring LSD to the World, Dies at 75"

, ''

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', May 12, 2017 At the end of 1966, Nina Graboi, a friend and colleague of Leary's who had spent time with him at Millbrook, became the director of the Center for the League of Spiritual Discovery in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

. The Center opened in March 1967. Leary and Alpert gave free weekly talks there; other guest speakers included Ralph Metzner and Allen Ginsberg. Leary's papers at the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress) ...

include complete records of the IFIF, the Castalia Foundation, and the League for Spiritual Discovery.Staton, Scott"Turn On, Tune In, Drop by the Archives: Timothy Leary at the N.Y.P.L."

, ''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'', June 11, 2011

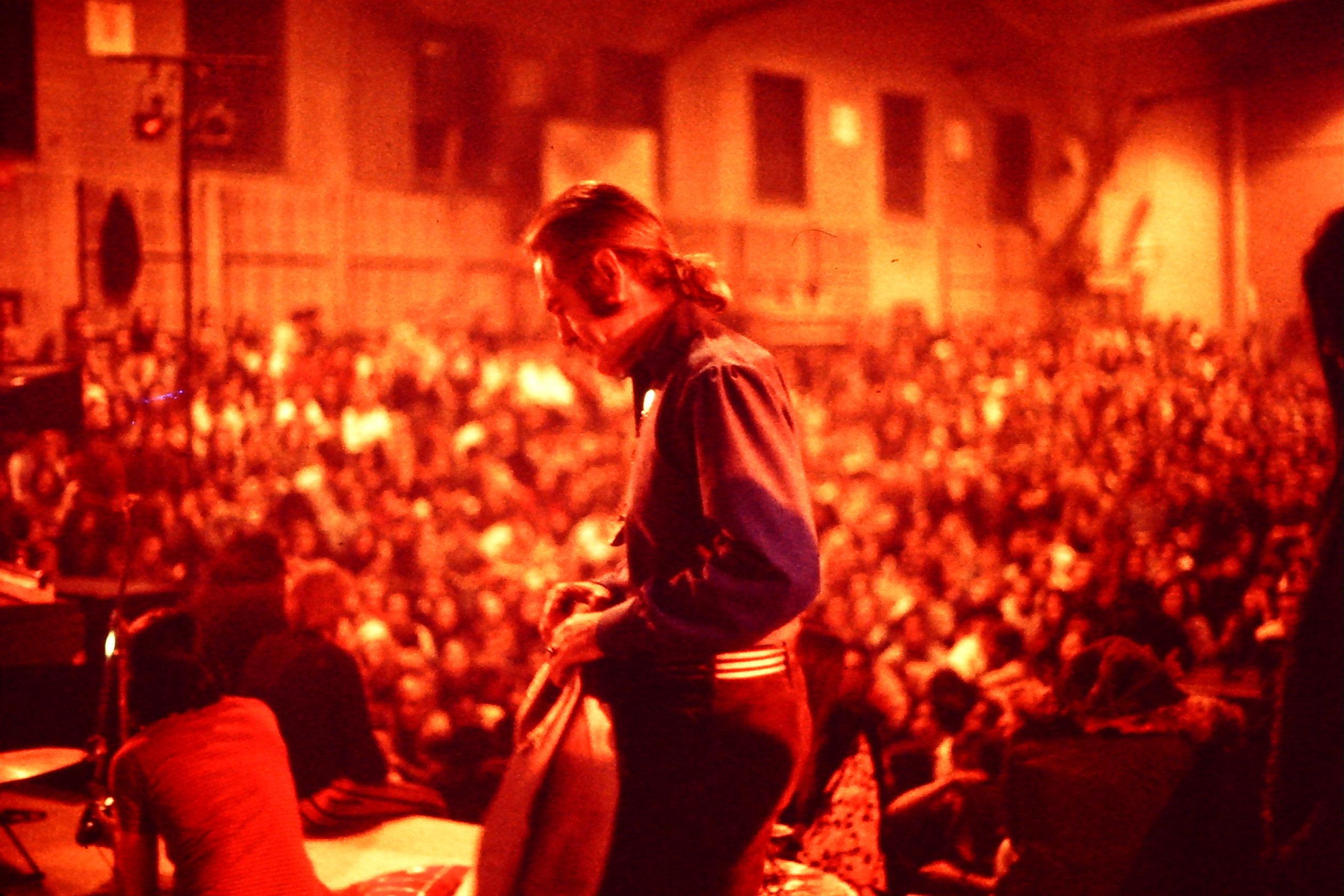

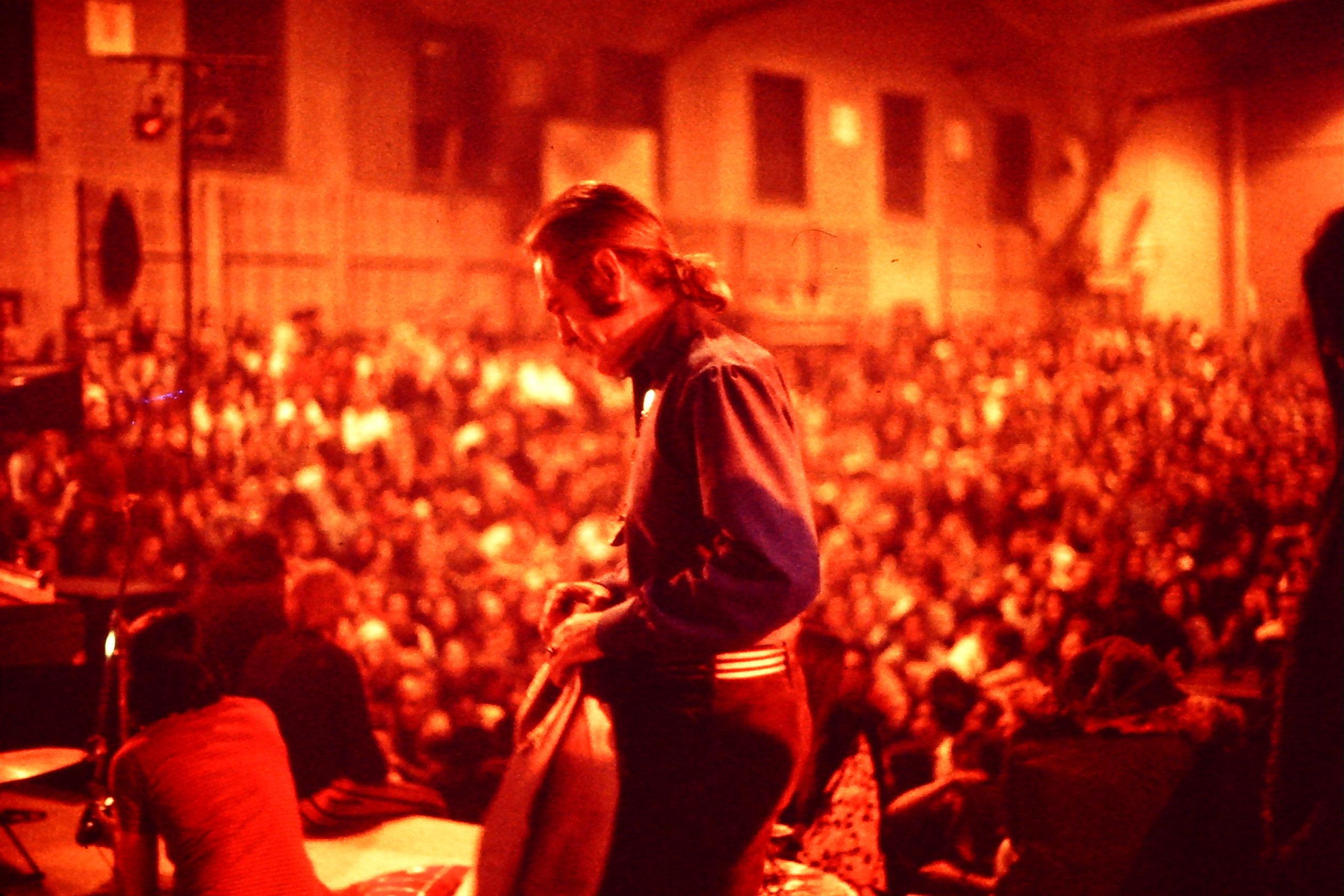

In late 1966 and early 1967, Leary toured college campuses presenting a multimedia performance called "The Death of the Mind", attempting an artistic replication of the LSD experience. He said that the League for Spiritual Discovery was limited to 360 members and was already at its membership limit, but encouraged others to form their own psychedelic religions. He published a pamphlet in 1967 calle''Start Your Own Religion''

to encourage people to do so. Leary was invited to attend the January 14, 1967 Human Be-In by Michael Bowen, the primary organizer of the event, a gathering of 30,000

hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to different countries around ...

s in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park

Golden Gate Park, located in San Francisco, California, United States, is a large urban park consisting of of public grounds. It is administered by the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department, which began in 1871 to oversee the developm ...

. In speaking to the group, Leary coined the famous phrase " Turn on, tune in, drop out". In a 1988 interview with Neil Strauss

Neil Darrow Strauss, also known by the pen names Style and Chris Powles, is an American author, journalist and ghostwriter. He is best known for his book '' The Game: Penetrating the Secret Society of Pickup Artists'', in which he describes his ...

, he said the slogan was "given to him" by Marshall McLuhan

Herbert Marshall McLuhan (July 21, 1911 – December 31, 1980) was a Canadian philosopher whose work is among the cornerstones of the study of media theory. He studied at the University of Manitoba and the University of Cambridge. He began his ...

when the two had lunch in New York City, adding, "Marshall was very much interested in ideas and marketing, and he started singing something like, 'Psychedelics hit the spot / Five hundred micrograms, that's a lot,' to the tune of he well-known Pepsi 1950s singing commercial Then he started going, 'Tune in, turn on, and drop out.'" Though the more popular "turn on, tune in, drop out" became synonymous with Leary, his actual definition with the League for Spiritual Discovery was: "''Drop Out''—detach yourself from the external social drama which is as dehydrated and ersatz as TV. ''Turn On''—find a sacrament which returns you to the temple of God, your own body. Go out of your mind. Get high. ''Tune In''—be reborn. Drop back in to express it. Start a new sequence of behavior that reflects your vision."

Repeated FBI raids ended the Millbrook era. Leary told author and Prankster Paul Krassner

Paul Krassner (April 9, 1932 – July 21, 2019) was an American author, journalist, and comedian. He was the founder, editor, and a frequent contributor to the freethought magazine ''The Realist'', first published in 1958. Krassner became a key ...

of a 1966 raid by Liddy, "He was a government agent entering our bedroom at midnight. We had every right to shoot him. But I've never owned a weapon in my life. I have never had and never will have a gun around."

In November 1967, Leary engaged in a televised debate on drug use with MIT professor Jerry Lettvin.

Post-Millbrook

At the end of 1967, Leary moved toLaguna Beach, California

Laguna Beach (; ''Laguna'', Spanish for "Lagoon") is a seaside resort city located in southern Orange County, California, in the United States. It is known for its mild year-round climate, scenic coves, environmental preservation efforts, an ...

, and made many friends in Hollywood. "When he married his third wife, Rosemary Woodruff, in 1967, the event was directed by Ted Markland of ''Bonanza

''Bonanza'' is an American Western television series that ran on NBC from September 13, 1959, to January 16, 1973. Lasting 14 seasons and 432 episodes, ''Bonanza'' is NBC's longest-running western, the second-longest-running western series on ...

''. All the guests were on acid."

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Leary formulated his eight-circuit model of consciousness in collaboration with writer Brian Barritt. The essay "The Seven Tongues of God" claimed that human brains have seven circuits producing seven levels of consciousness. An eighth circuit was added in the 1973 pamphlet ''Neurologic'', written with Joanna Leary while he was in prison. This eighth-circuit idea was not exhaustively formulated until the publication of ''Exo-Psychology'' by Leary and Robert Anton Wilson

Robert Anton Wilson (born Robert Edward Wilson; January 18, 1932 – January 11, 2007) was an American author, futurist, psychologist, and self-described agnostic mystic. Recognized within Discordianism as an Episkopos, pope and saint, Wilso ...

's ''Cosmic Trigger

''Cosmic Trigger I: The Final Secret of The Illuminati'' is the first book in the ''Cosmic Trigger'' series, first published in 1977 and the first of a three-volume autobiographical and philosophical work by Robert Anton Wilson. It has a forewor ...

'' in 1977. Wilson contributed to the model after befriending Leary in the early 1970s, and used it as a framework for further exposition in his book ''Prometheus Rising

''Prometheus Rising'' is a 1983 guidebook by Robert Anton Wilson. The book includes explanations of Timothy Leary eight-circuit model of consciousness, Alfred Korzybski general semantics, Aleister Crowley Thelema, and various other topics related t ...

'', among other works.

Leary believed that the first four of these circuits ("the Larval Circuits" or "Terrestrial Circuits") are naturally accessed by most people at transition points in life such as puberty. The second four circuits ("the Stellar Circuits" or "Extra-Terrestrial Circuits"), Leary wrote, were "evolutionary offshoots" of the first four that would be triggered at transition points as humans evolve further. These circuits, according to Leary, would equip humans to live in space and expand consciousness for further scientific and social progress. Leary suggested that some people might trigger these circuits sooner through meditation, yoga, or psychedelic drugs specific to each circuit. He suggested that the feelings of floating and uninhibited motion sometimes experienced with marijuana demonstrated the purpose of the higher four circuits. The function of the fifth circuit was to accustom humans to life at a zero gravity environment. Leary did not specify the location of the eight circuits in any brain structures, neural organization, or chemical pathways. He wrote that a higher intelligence "located in interstellar nuclear-gravitational-quantum structures" gave humans the eight circuits. A "U.F.O. message" was encoded in human DNA.

Many researchers believed that Leary provided little scientific evidence for his claims. Even before he began working on psychedelics, he was known as a theoretician rather than a data collector. His most ambitious pre-psychedelic work was ''Interpersonal Diagnosis Of Personality''. The reviewer for ''The British Medical Journal'', H. J. Eysenck, wrote that Leary created a confusing and overly broad rubric for testing psychiatric conditions. "Perhaps the worst failing of the book is the omission of any kind of proof for the validity and reliability of the diagnostic system," Eysenck wrote. "It is simply not enough to say" that the accuracy of the system "can be checked by the reader" in clinical practice. In 1965, Leary co-edited ''The Psychedelic Reader''. Penn State psychology researcher Jerome E. Singer reviewed the book and singled out Leary as the worst offender in a work containing "melanges of hucksterism". In place of scientific data about the effects of LSD, Leary used metaphors about "galaxies spinning" faster than the speed of light and a cerebral cortex "turned on to a much higher voltage".

Legal troubles

Leary's first run-in with the law came on December 23, 1965, when he was arrested for marijuana possession. Leary took his two children, Jack and Susan, and his girlfriend Rosemary Woodruff to Mexico for an extended stay to write a book. On their return from Mexico to the United States, a

Leary's first run-in with the law came on December 23, 1965, when he was arrested for marijuana possession. Leary took his two children, Jack and Susan, and his girlfriend Rosemary Woodruff to Mexico for an extended stay to write a book. On their return from Mexico to the United States, a US Customs Service

The United States Customs Service was the very first federal law enforcement agency of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government. Established on July 31, 1789, it collected import tariffs, performed other selected borde ...

official found marijuana in Susan's underwear. They had crossed into Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, in the late afternoon and discovered that they would have to wait until morning for the appropriate visa for an extended stay. They decided to cross back into Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

to spend the night, and were on the US–Mexico bridge when Rosemary remembered that she had a small amount of marijuana in her possession. It was impossible to throw it out on the bridge, so Susan put it in her underwear. After taking responsibility for the controlled substance, Leary was convicted of possession under the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 on March 11, 1966, sentenced to 30 years in prison, fined $30,000, and ordered to undergo psychiatric treatment. He appealed the case on the basis that the Marihuana Tax Act was unconstitutional, as it required a degree of self-incrimination

In criminal law, self-incrimination is the act of exposing oneself generally, by making a statement, "to an accusation or charge of crime; to involve oneself or another ersonin a criminal prosecution or the danger thereof". (Self-incriminati ...

in blatant violation of the Fifth Amendment.

On December 26, 1968, Leary was arrested again in Laguna Beach, California

Laguna Beach (; ''Laguna'', Spanish for "Lagoon") is a seaside resort city located in southern Orange County, California, in the United States. It is known for its mild year-round climate, scenic coves, environmental preservation efforts, an ...

, this time for the possession of two marijuana "roaches". Leary alleged that they were planted by the arresting officer, but was convicted of the crime. On May 19, 1969, The Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

concurred with Leary in '' Leary v. United States'', declared the Marihuana Tax Act unconstitutional, and overturned his 1965 conviction.

On that same day, Leary announced his candidacy for governor of California

The governor of California is the head of government of the U.S. state of California. The governor is the commander-in-chief of the California National Guard and the California State Guard.

Established in the Constitution of California, t ...

against the Republican incumbent, Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

. His campaign slogan was "Come together, join the party." On June 1, 1969, Leary joined John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter, musician and peace activist who achieved worldwide fame as founder, co-songwriter, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of ...

and Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono ( ; ja, 小野 洋子, Ono Yōko, usually spelled in katakana ; born February 18, 1933) is a Japanese multimedia artist, singer, songwriter, and peace activist. Her work also encompasses performance art and filmmaking.

Ono grew up i ...

at their Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

bed-in, and Lennon subsequently wrote Leary a campaign song called " Come Together".

On January 21, 1970, Leary received a ten-year sentence for his 1968 offense, with a further ten added later while in custody for a prior arrest in 1965, for a total of 20 years to be served consecutively. On his arrival in prison, he was given psychological tests used to assign inmates to appropriate work details. Having designed some of these tests himself (including the "Leary Interpersonal Behavior Inventory"), Leary answered them in such a way that he seemed to be a very conforming, conventional person with a great interest in forestry and gardening. As a result, he was assigned to work as a gardener in a lower-security prison from which he escaped in September 1970, saying that his nonviolent escape was a humorous prank and leaving a challenging note for the authorities to find after he was gone.

For a fee of $25,000, paid by The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, the Weathermen smuggled Leary out of prison in a pickup truck driven by Clayton Van Lydegraf

Clayton Van Lydegraf (May 6, 1915 – March 30, 1992) was a writer and activist of significant influence on the New Left in the 1960s. He served as Secretary of the Communist Party in Washington State in the late 1940s.

Van Lydegraf served as a l ...

. The truck met Leary after he had escaped over the prison wall by climbing along a telephone wire. The Weathermen then helped both Leary and Rosemary out of the U.S. (and eventually into Algeria). He sought the patronage of Eldridge Cleaver for $10,000 and the remnants of the Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxism-Leninism, Marxist-Leninist and Black Power movement, black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. New ...

's "government in exile" in Algeria, but after a short stay with them said that Cleaver had attempted to hold him and his wife hostage. Cleaver had put Leary and his wife under "house arrest" due to exasperation with their socialite lifestyle.

In 1971, the couple fled to Switzerland, where they were sheltered and effectively imprisoned by a high-living arms dealer, Michel Hauchard, who claimed he had an "obligation as a gentleman to protect philosophers"; Hauchard intended to broker a surreptitious film deal, and forced Leary to assign his future earnings (which Leary eventually won back). In 1972, Nixon's attorney general, John Mitchell, persuaded the Swiss government to imprison Leary, which it did for a month, but refused to extradite him to the U.S.

Leary and Rosemary separated later that year; she traveled widely, then moved back to the U.S., where she lived as a fugitive until the 1990s. Shortly after his separation from Rosemary in 1972, Leary became involved with Swiss-born British socialite Joanna Harcourt-Smith, a stepdaughter of financier Árpád Plesch and ex-girlfriend of Hauchard. The couple "married" in a hotel under the influence of cocaine and LSD two weeks after they were introduced, and Harcourt-Smith used his surname until their breakup in 1977. They traveled to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, then Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, and finally ended up in Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into #Districts, 22 municipal dist ...

, Afghanistan, in 1972; according to Lucy Sante

Lucy Sante (formerly Luc Sante; born May 25, 1954) is a Belgium-born American writer, critic, and artist. She is a frequent contributor to ''The New York Review of Books''. Her books include '' Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York'' (1991) ...

, "Afghanistan had no extradition treaty with the United States, but this stricture did not apply to American airliners." American authorities used that interpretation of the law to interdict Leary. "Before Leary could deplane, he was arrested by an agent of the federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs." Leary asserted a different story on appeal before the California Court of Appeal for the Second District, namely:

Leary's bail was set at $5 million. The judge at his remand hearing said, "If he is allowed to travel freely, he will speak publicly and spread his ideas". Facing 95 years in prison, Leary hired criminal defense attorney Bruce Margolin

Bruce Margolin (born September 11, 1941) is an American criminal defense attorney who specializes in marijuana and drug laws. Since 1973, he has served as the executive director of the Los Angeles chapter of NORML (National Organization for t ...

. Leary mostly directed his own defense strategy, which proved unsuccessful: the jury convicted him after deliberating for less than two hours. Leary received five years for his prison escape, added to his original 10-year sentence. In 1973, he was sent to Folsom Prison in California, and put in solitary confinement. While in Folsom, he was placed in a cell right next to Charles Manson

Charles Milles Manson (; November 12, 1934November 19, 2017) was an American criminal and musician who led the Manson Family, a cult based in California, in the late 1960s. Some of the members committed a series of nine murders at four loca ...

, and though they could not see each other, they could talk together. In their discussions, Manson was surprised and found it difficult to understand why Leary had given people LSD without trying to control them. At one point, Manson said to Leary, "They took you off the streets so that I could continue with your work."

Leary became an FBI informant in order to shorten his prison sentence and entered the witness protection program upon his release in 1976. He claimed that he feigned cooperation with the FBI investigation of Weathermen by providing information that they already had or that was of little consequence. The FBI gave him the code name "Charlie Thrush". In a 1974 news conference, Allen Ginsberg, Ram Dass, and Leary's 25-year-old son Jack denounced Leary, calling him a "cop informant," "liar," and "paranoid schizophrenic." No prosecutions stemmed from his FBI reporting. In 1999, a letter from 22 "Friends of Timothy Leary" sought to soften impressions of the FBI episode. It was signed by authors such as Douglas Rushkoff

Douglas Mark Rushkoff (born February 18, 1961) is an American media theorist, writer, columnist, lecturer, graphic novelist, and documentarian. He is best known for his association with the early cyberpunk culture and his advocacy of open sour ...

, Ken Kesey

Ken Elton Kesey (September 17, 1935 – November 10, 2001) was an American novelist, essayist and countercultural figure. He considered himself a link between the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s.

Kesey was born in ...

, and Robert Anton Wilson

Robert Anton Wilson (born Robert Edward Wilson; January 18, 1932 – January 11, 2007) was an American author, futurist, psychologist, and self-described agnostic mystic. Recognized within Discordianism as an Episkopos, pope and saint, Wilso ...

. Susan Sarandon, Genesis P-Orridge

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (born Neil Andrew Megson; 22 February 1950 – 14 March 2020) was a singer-songwriter, musician, poet, performance artist, visual artist, and occultist who rose to notoriety as the founder of the COUM Transmissions ar ...

and Leary's goddaughter Winona Ryder also signed. The letter said that Leary had smuggled a message to the Weather Underground informing it "that he was considering making a deal with the FBI" and he then "waited for their approval". The reported reply was, "We understand." The letter writers did not provide confirmation that the Weather Underground okayed his cooperation with the FBI.

While in prison, Leary was sued by the parents of Vernon Powell Cox, who had jumped from a third-story window of a Berkeley apartment while under the influence of LSD. Cox had taken the drug after attending a lecture by Leary promoting LSD use. Leary was unable to be present due to his incarceration, and unable to arrange for legal representation; a default judgment was entered against him in the amount of $100,000.

Post-prison

On April 21, 1976, GovernorJerry Brown

Edmund Gerald Brown Jr. (born April 7, 1938) is an American lawyer, author, and politician who served as the 34th and 39th governor of California from 1975 to 1983 and 2011 to 2019. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected Secretary of S ...

released Leary from prison. After briefly relocating to Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe ( ; , Spanish for 'Holy Faith'; tew, Oghá P'o'oge, Tewa for 'white shell water place'; tiw, Hulp'ó'ona, label= Northern Tiwa; nv, Yootó, Navajo for 'bead + water place') is the capital of the U.S. state of New Mexico. The name “S ...

, with Harcourt-Smith under the auspices of the United States Federal Witness Protection Program, the couple separated in early 1977.

Leary then moved to the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

, where he resided for the rest of his life. Unable to secure a conventional academic or research appointment due to his reputation, he continued to publish books through the independent press while maintaining an upper middle class lifestyle by making paid appearances at colleges and nightclubs as a self-described "stand-up philosopher". In 1978, he married filmmaker Barbara Blum, also known as Barbara Chase, sister of actress Tanya Roberts. He adopted Blum's young son Zachary and raised him as his own. He also took on several godchildren, including Winona Ryder (the daughter of his archivist Michael Horowitz) and technologist Joi Ito.

Leary developed an improbable partnership with former foe G. Gordon Liddy, the Watergate