thylacines on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The thylacine ( , or , also ) (''Thylacinus cynocephalus'') is an

Numerous examples of thylacine engravings and

Numerous examples of thylacine engravings and

The modern thylacine probably appeared about 2 million years ago, during the

The modern thylacine probably appeared about 2 million years ago, during the

extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

carnivorous marsupial

Dasyuromorphia (, meaning "hairy tail" in Greek) is an order comprising most of the Australian carnivorous marsupials, including quolls, dunnarts, the numbat, the Tasmanian devil, and the thylacine. In Australia, the exceptions include the omn ...

that was native to the Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

. The last known live animal was captured in 1930 in Tasmania. It is commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger (because of its striped lower back) or the Tasmanian wolf (because of its canid-like characteristics). Various Aboriginal Tasmanian

The Aboriginal Tasmanians (Palawa kani: ''Palawa'' or ''Pakana'') are the Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal people of the List of islands of Australia, Australian island of Tasmania, located south of the mainland. For much of the 20th centu ...

names have been recorded, such as ''coorinna'', ''kanunnah'', ''cab-berr-one-nen-er'', ''loarinna'', ''laoonana'', ''can-nen-ner'' and ''lagunta'', while ''kaparunina'' is used in Palawa kani

Palawa kani is a constructed language created by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre as a composite Tasmanian languages, Tasmanian language, based on reconstructed vocabulary from the limited accounts of the various languages once spoken by the eas ...

.

The thylacine was relatively shy and nocturnal, with the general appearance of a medium-to-large-size canid, except for its stiff tail and abdominal pouch similar to that of a kangaroo

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern ...

. Because of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

, it displayed an anatomy and adaptations similar to the tiger

The tiger (''Panthera tigris'') is the largest living Felidae, cat species and a member of the genus ''Panthera''. It is most recognisable for its dark vertical stripes on orange fur with a white underside. An apex predator, it primarily pr ...

(''Panthera tigris'') and wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly un ...

(''Canis lupus'') of the Northern Hemisphere, such as dark transverse stripes that radiated from the top of its back, and a skull shape extremely similar to those of canids, despite being unrelated. The thylacine was a formidable apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

, Paddle (2000) though exactly how large its prey animals were is disputed. Its closest living relatives are the other members of Dasyuromorphia, including the Tasmanian devil

The Tasmanian devil (''Sarcophilus harrisii'') ( palawa kani: purinina) is a carnivorous marsupial of the family Dasyuridae. Until recently, it was only found on the island state of Tasmania, but it has been reintroduced to New South Wales ...

and quoll

Quolls (; genus ''Dasyurus'') are carnivorous marsupials native to Australia and New Guinea. They are primarily nocturnal and spend most of the day in a den. Of the six species of quoll, four are found in Australia and two in New Guinea. Anoth ...

s. The thylacine was one of only two marsupials known to have a pouch in both sexes: the other (still extant) species is the water opossum from Central and South America. The pouch of the male thylacine served as a protective sheath, covering the external reproductive organs.

The thylacine had become locally extinct on both New Guinea and the Australian mainland before British settlement of the continent, but its last stronghold was on the island of Tasmania, along with several other endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

species, including the Tasmanian devil. Intensive hunting encouraged by bounties is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributing factors may have been disease, the introduction of and competition with dingo

The dingo (''Canis familiaris'', ''Canis familiaris dingo'', ''Canis dingo'', or ''Canis lupus dingo'') is an ancient ( basal) lineage of dog found in Australia. Its taxonomic classification is debated as indicated by the variety of scienti ...

es, and human encroachment into its habitat.

Taxonomic and evolutionary history

Numerous examples of thylacine engravings and

Numerous examples of thylacine engravings and rock art

In archaeology, rock art is human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type also m ...

have been found, dating back to at least 1000 BC. Petroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

images of the thylacine can be found at the Dampier Rock Art Precinct, on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia.

By the time the first European explorers arrived, the animal was already extinct in mainland Australia and New Guinea, and rare in Tasmania. Europeans may have encountered it in Tasmania as far back as 1642, when Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

first arrived in Tasmania. His shore party reported seeing the footprints of "wild beasts having claws like a ''Tyger''".Rembrants. D. (1682) "A short relation out of the journal of Captain Abel Jansen Tasman, upon the discovery of the ''South Terra incognita''; not long since published in the Low Dutch". ''Philosophical Collections of the Royal Society of London'', (6), 179–186. Quoted in Paddle (2000), p. 3. Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne

Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne (22 May 1724 – 12 June 1772) was a French privateer, East India captain and explorer. The expedition he led to find the hypothetical ''Terra Australis'' in 1771 made important geographic discoveries in the south ...

, arriving with the ''Mascarin'' in 1772, reported seeing a "tiger cat".Roth, H. L. (1891) "Crozet's Voyage to Tasmania, New Zealand, etc. ... 1771–1772.". London. Truslove and Shirley. Quoted in Paddle (2000), p. 3. Positive identification of the thylacine as the animal encountered cannot be made from this report, since the tiger quoll

The tiger quoll (''Dasyurus maculatus''), also known as the spotted-tail quoll, the spotted quoll, the spotted-tail dasyure, native cat or the tiger cat, is a carnivorous marsupial of the quoll genus '' Dasyurus'' native to Australia. With male ...

(''Dasyurus maculatus'') is similarly described.

The first definitive encounter was by French explorers on 13 May 1792, as noted by the naturalist Jacques Labillardière

Jacques-Julien Houtou de Labillardière (28 October 1755 – 8 January 1834) was a French biologist noted for his descriptions of the flora of Australia. Labillardière was a member of a voyage in search of the La Pérouse expedition. He pub ...

, in his journal from the expedition led by d'Entrecasteaux

Antoine Raymond Joseph de Bruni, chevalier d'Entrecasteaux () (8 November 1737 – 21 July 1793) was a French naval officer, explorer and colonial governor. He is perhaps best known for his exploration of the Australian coast in 1792, while ...

. In 1805, William Paterson, the Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania, sent a detailed description for publication in the ''Sydney Gazette

''The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser'' was the first newspaper printed in Australia, running from 5 March 1803 until 20 October 1842. It was a semi-official publication of the government of New South Wales, authorised by Governo ...

''. Paddle (2000), p. 3. He also sent a description of the thylacine in a letter to Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

, dated 30 March 1805.

The first detailed scientific description was made by Tasmania's Deputy Surveyor-General, George Harris, in 1808, five years after first European settlement of the island. Harris originally placed the thylacine in the genus ''Didelphis

''Didelphis'' is a genus of New World marsupials. The six species in the genus ''Didelphis'', commonly known as Large American opossums, are members of the ''opossum'' order, Didelphimorphia.

The genus ''Didelphis'' is composed of cat-sized om ...

'', which had been created by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

for the American opossum

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 93 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered No ...

s, describing it as ''Didelphis cynocephala'', the "dog-headed opossum". Recognition that the Australian marsupials were fundamentally different from the known mammal genera led to the establishment of the modern classification scheme, and in 1796, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire created the genus '' Dasyurus'', where he placed the thylacine in 1810. To resolve the mixture of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

nomenclature, the species name was altered to ''cynocephalus''. In 1824, it was separated out into its own genus, ''Thylacinus'', by Temminck

Coenraad Jacob Temminck (; 31 March 1778 – 30 January 1858) was a Dutch aristocrat, zoologist and museum director.

Biography

Coenraad Jacob Temminck was born on 31 March 1778 in Amsterdam in the Dutch Republic. From his father, Jacob Temminc ...

. Paddle (2000), p. 5. The common name derives directly from the genus name, originally from the Greek (), meaning "pouch" or "sack".

Evolution

The modern thylacine probably appeared about 2 million years ago, during the

The modern thylacine probably appeared about 2 million years ago, during the Early Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, being the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently estimated to span the time ...

. Specimens from the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Charles De Vis in 1894, have in the past been suggested to represent ''Thylacinus cynocephalus'', but have been shown to either have been curatorial errors, or ambiguous in their specific attribution.Mackness, B. S., et al. "Confirmation of ''Thylacinus'' from the Pliocene Chinchilla Local Fauna". ''Australian Mammalogy''. 24.2 (2002): 237–242. The family Thylacinidae includes at least 12 species in eight genera, and appears around the late

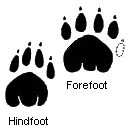

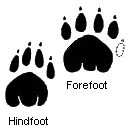

. '' Thylacine footprints could be distinguished from other native or introduced animals; unlike foxes, cats, dogs,

Thylacine footprints could be distinguished from other native or introduced animals; unlike foxes, cats, dogs,

Little is known about the behaviour of the thylacine. A few observations were made of the animal in captivity, but only limited, anecdotal evidence exists of the animal's behaviour in the wild. Most observations were made during the day, whereas the thylacine was naturally nocturnal. Those observations, made in the twentieth century, may have been atypical, as they were of a species already under the stresses that would soon lead to its extinction. Some behavioural characteristics have been extrapolated from the behaviour of its close relative, the Tasmanian devil.

The thylacine was a

Little is known about the behaviour of the thylacine. A few observations were made of the animal in captivity, but only limited, anecdotal evidence exists of the animal's behaviour in the wild. Most observations were made during the day, whereas the thylacine was naturally nocturnal. Those observations, made in the twentieth century, may have been atypical, as they were of a species already under the stresses that would soon lead to its extinction. Some behavioural characteristics have been extrapolated from the behaviour of its close relative, the Tasmanian devil.

The thylacine was a

There is some controversy over the preferred prey size of the thylacine. A 2011 study by the

There is some controversy over the preferred prey size of the thylacine. A 2011 study by the

Australia lost more than 90% of its

Australia lost more than 90% of its

However, it is likely that multiple factors led to its decline and eventual extinction, including competition with wild dogs introduced by European settlers, erosion of its habitat, the concurrent extinction of prey species, and a

However, it is likely that multiple factors led to its decline and eventual extinction, including competition with wild dogs introduced by European settlers, erosion of its habitat, the concurrent extinction of prey species, and a

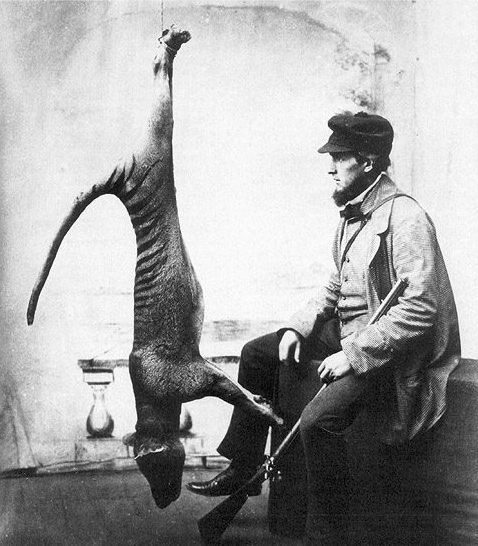

File:Thylacine-chicken.png, This 1921 photo by

The last captive thylacine, often referred to as Benjamin, lived as an

The last captive thylacine, often referred to as Benjamin, lived as an

The

The  In 1982, a researcher with the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service, Hans Naarding, observed what he believed to be a thylacine for three minutes during the night at a site near Arthur River in northwestern Tasmania. The sighting led to an extensive year-long government-funded search. In 1985, Aboriginal tracker Kevin Cameron produced five photographs which appear to show a digging thylacine, which he stated he took in

In 1982, a researcher with the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service, Hans Naarding, observed what he believed to be a thylacine for three minutes during the night at a site near Arthur River in northwestern Tasmania. The sighting led to an extensive year-long government-funded search. In 1985, Aboriginal tracker Kevin Cameron produced five photographs which appear to show a digging thylacine, which he stated he took in

The

The  In late 2002, the researchers had some success as they were able to extract replicable DNA from the specimens. On 15 February 2005, the museum announced that it was stopping the project after tests showed the DNA retrieved from the specimens had been too badly degraded to be usable. In May 2005, Archer, the

In late 2002, the researchers had some success as they were able to extract replicable DNA from the specimens. On 15 February 2005, the museum announced that it was stopping the project after tests showed the DNA retrieved from the specimens had been too badly degraded to be usable. In May 2005, Archer, the

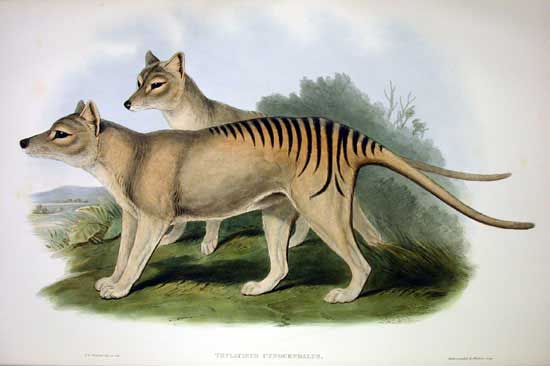

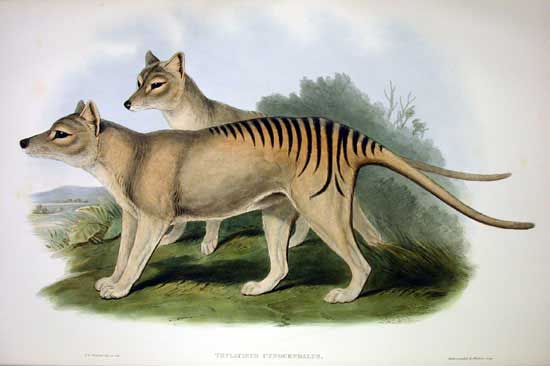

The best known illustrations of ''Thylacinus cynocephalus'' were those in

The best known illustrations of ''Thylacinus cynocephalus'' were those in

ABC.net.au: Australian Megafauna

* ttp://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7825011.stm BBC News: item about the thylacine genome

Preserved thylacine body at National Museum of Australia, Canberra

Tasmanian tiger: newly released footage captures last-known vision of thylacine – video

''The Guardian''. 19 May 2020. {{Authority control Apex predators Articles containing video clips Carnivorous marsupials Dasyuromorphs Extinct mammals of Australia Extinct marsupials Holocene extinctions Mammal extinctions since 1500 Mammals described in 1808 Mammals of Tasmania Marsupials of Australia Marsupials of New Guinea Pleistocene first appearances Species made extinct by deliberate extirpation efforts

Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but t ...

with the small, plesiomorphic '' Badjcinus turnbulli''. Early thylacinids were quoll-sized, well under , and probably ate insects and small reptiles and mammals, although signs of an increasingly-carnivorous diet can be seen as early as the early Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

in '' Wabulacinus''. Members of the genus ''Thylacinus'' are notable for a dramatic increase in both the expression of carnivorous dental traits and in size, with the largest species, ''Thylacinus potens

''Thylacinus potens'' ("powerful pouched dog") was the largest species of the family Thylacinidae, originally known from a single poorly preserved fossil discovered by Michael O. Woodburne in 1967 in a Late Miocene locality near Alice Springs, N ...

'' and ''Thylacinus megiriani

''Thylacinus megiriani'' lived during the late Miocene, 8 million years ago; the area ''T. megiriani'' inhabited in the Northern Territory was covered in forest with a permanent supply of water.

''Thylacinus megiriani'' was a quadrupedal marsup ...

'' both approaching the size of a wolf. In Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch withi ...

and early Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

times, the modern thylacine was widespread (although never numerous) throughout Australia and New Guinea.

A classic example of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

, the thylacine showed many similarities to the members of the dog family, Canidae

Canidae (; from Latin, '' canis'', " dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to as dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). There are three subfamilies found withi ...

, of the Northern Hemisphere: sharp teeth, powerful jaws, raised heels, and the same general body form. Since the thylacine filled the same ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

in Australia and New Guinea as canids did elsewhere, it developed many of the same features. Despite this, as a marsupial, it is unrelated to any of the Northern Hemisphere placental mammal

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

predators.

The thylacine is a basal member of the Dasyuromorphia, along with numbats, dunnart

Dunnart is a common name for species of the genus ''Sminthopsis'', narrow-footed marsupials the size of a European mouse. They have a largely insectivorous diet.

Taxonomy

The genus name ''Sminthopsis'' was published by Oldfield Thomas in 18 ...

s, wambenger

The phascogales (members of the eponymous genus ''Phascogale''), also known as wambengers or mousesacks,A Hollow Victory

s, and quoll

Quolls (; genus ''Dasyurus'') are carnivorous marsupials native to Australia and New Guinea. They are primarily nocturnal and spend most of the day in a den. Of the six species of quoll, four are found in Australia and two in New Guinea. Anoth ...

s. The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

follows:

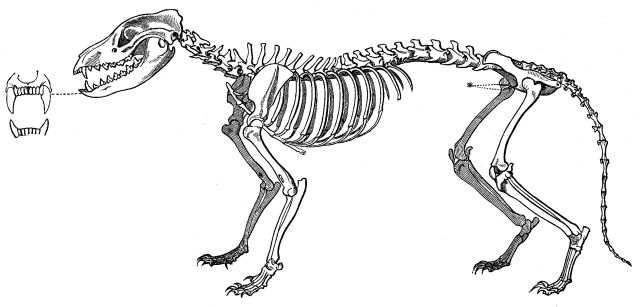

Description

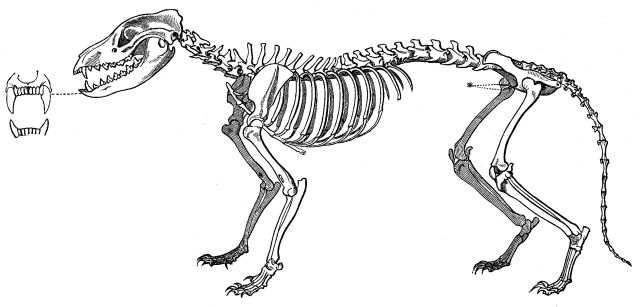

The only recorded species of ''Thylacinus

''Thylacinus'' is a genus of extinct carnivorous marsupials from the order Dasyuromorphia. The only recent member was the thylacine (''Thylacinus cynocephalus''), commonly also known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, which is believed t ...

'', a genus that superficially resembles the dogs and foxes of the family Canidae

Canidae (; from Latin, '' canis'', " dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to as dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). There are three subfamilies found withi ...

, the animal was a predatory marsupial that existed on mainland Australia during the Holocene epoch and observed by Europeans on the island of Tasmania; the species is known as the Tasmanian tiger for the striped markings of the pelage

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket ...

. Descriptions of the thylacine come from preserved specimens, fossil records, skins and skeletal remains, and black and white photographs and film of the animal both in captivity and from the field. The thylacine resembled a large, short-haired dog with a stiff tail which smoothly extended from the body in a way similar to that of a kangaroo

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern ...

. The mature thylacine ranged from long, plus a tail of around . Adults stood about at the shoulder and on average weighed , though they could range anywhere from . There was slight sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

with the males being larger than females on average. Males weighed in at around , and females weighed in at around . The skull is noted to be highly convergent on those of canids, most closely remembling that of the red fox

The red fox (''Vulpes vulpes'') is the largest of the true foxes and one of the most widely distributed members of the Order (biology), order Carnivora, being present across the entire Northern Hemisphere including most of North America, Europe ...

.

Thylacines, uniquely for marsupials, had largely cartilaginous epipubic bones with a highly reduced osseous element. This has been once considered a synapomorphy

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to hav ...

with sparassodonts, though it is now thought that both groups reduced their epipubics independently. Its yellow-brown coat featured 15 to 20 distinctive dark stripes across its back, rump and the base of its tail, which earned the animal the nickname "tiger". The stripes were more pronounced in younger specimens, fading as the animal got older. One of the stripes extended down the outside of the rear thigh. Its body hair was dense and soft, up to in length. Colouration varied from light fawn to a dark brown; the belly was cream-coloured.

Its rounded, erect ears were about long and covered with short fur. The early scientific studies suggested it possessed an acute sense of smell which enabled it to track prey, but analysis of its brain structure revealed that its olfactory bulb

The olfactory bulb (Latin: ''bulbus olfactorius'') is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex ...

s were not well developed. It is likely to have relied on sight and sound when hunting instead.

The thylacine was able to open its jaws to an unusual extent: up to 80 degrees. This capability can be seen in part in David Fleay

David Howells Fleay (; 6 January 1907 – 7 August 1993) was an Australian scientist and biologist who pioneered the captive breeding of endangered species, and was the first person to breed the platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus'') in ...

's short black-and-white film sequence of a captive thylacine from 1933. The jaws were muscular, and had 46 teeth, but studies show the thylacine jaw was too weak to kill sheep."Tasmanian Tiger's Jaw Was Too Small to Attack Sheep, Study Shows". ''

Science Daily

''Science Daily'' is an American website launched in 1995 that aggregates press releases and publishes lightly edited press releases (a practice called churnalism) about science, similar to Phys.org and EurekAlert!.

The site was founded by ...

''. 1 September 2011. The tail vertebrae were fused to a degree, with resulting restriction of full tail movement. Fusion may have occurred as the animal reached full maturity. The tail tapered towards the tip. In juveniles, the tip of the tail had a ridge. The female thylacine had a pouch with four teat

A teat is the projection from the mammary glands of mammals from which milk flows or is ejected for the purpose of feeding young. In many mammals the teat projects from the udder. The number of teats varies by mammalian species and often corr ...

s, but unlike many other marsupials, the pouch opened to the rear of its body. Males had a scrotal pouch, unique amongst the Australian marsupials, into which they could withdraw their scrotal sac for protection.

Thylacine footprints could be distinguished from other native or introduced animals; unlike foxes, cats, dogs,

Thylacine footprints could be distinguished from other native or introduced animals; unlike foxes, cats, dogs, wombat

Wombats are short-legged, muscular quadrupedal marsupials that are native to Australia. They are about in length with small, stubby tails and weigh between . All three of the extant species are members of the family Vombatidae. They are ad ...

s, or Tasmanian devil

The Tasmanian devil (''Sarcophilus harrisii'') ( palawa kani: purinina) is a carnivorous marsupial of the family Dasyuridae. Until recently, it was only found on the island state of Tasmania, but it has been reintroduced to New South Wales ...

s, thylacines had a very large rear pad and four obvious front pads, arranged in almost a straight line. The hindfeet were similar to the forefeet but had four digits rather than five. Their claws were non-retractable. More detail can be seen in a cast taken from a freshly dead thylacine. The cast shows the plantar pad in more detail and shows that the plantar pad is tri-lobal in that it exhibits three distinctive lobes. It is a single plantar pad divided by three deep grooves. The distinctive plantar pad shape along with the asymmetrical nature of the foot makes it quite different from animals such as dogs or foxes. This cast dates back to the early 1930s and is part of the Museum of Victoria's thylacine collection.

The thylacine was noted as having a stiff and somewhat awkward gait

Gait is the pattern of movement of the limbs of animals, including humans, during locomotion over a solid substrate. Most animals use a variety of gaits, selecting gait based on speed, terrain, the need to maneuver, and energetic efficiency. ...

, making it unable to run at high speed. It could also perform a bipedal hop, in a fashion similar to a kangaroo—demonstrated at various times by captive specimens. Guiler speculates that this was used as an accelerated form of motion when the animal became alarmed. The animal was also able to balance on its hind legs and stand upright for brief periods.

Observers of the animal in the wild and in captivity noted that it would growl and hiss when agitated, often accompanied by a threat-yawn. During hunting, it would emit a series of rapidly repeated guttural cough-like barks (described as "yip-yap", "cay-yip" or "hop-hop-hop"), probably for communication between the family pack members. It also had a long whining cry, probably for identification at distance, and a low snuffling noise used for communication between family members. Paddle (2000), pp. 65–66. Some observers described it as having a strong and distinctive smell, others described a faint, clean, animal odour, and some no odour at all. It is possible that the thylacine, like its relative, the Tasmanian devil, gave off an odour when agitated. Paddle (2000), p. 49.

Distribution and habitat

The thylacine most likely preferred the dry eucalyptus forests, wetlands, and grasslands ofmainland Australia

Mainland Australia is the main landmass of the Australian continent, excluding the Aru Islands, New Guinea, Tasmania, and other Australian offshore islands. The landmass also constitutes the mainland of the territory governed by the Commonw ...

. Indigenous Australian rock paintings indicate that the thylacine lived throughout mainland Australia and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

. Proof of the animal's existence in mainland Australia came from a desiccated carcass that was discovered in a cave in the Nullarbor Plain

The Nullarbor Plain ( ; Latin: feminine of , 'no', and , 'tree') is part of the area of flat, almost treeless, arid or semi-arid country of southern Australia, located on the Great Australian Bight coast with the Great Victoria Desert to its ...

in Western Australia in 1990; carbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

revealed it to be around 3,300 years old. Recently examined fossilised footprints also suggest historical distribution of the species on Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island, also known as Karta Pintingga (literally 'Island of the Dead' in the language of the Kaurna people), is Australia's third-largest island, after Tasmania and Melville Island. It lies in the state of South Australia, southwest ...

. The northernmost record of the species is from the Kiowa rock shelter in Chimbu Province

Chimbu, more frequently spelled Simbu, is a province in the Highlands Region of Papua New Guinea. The province has an area of 6,112 km2 and a population of 376,473 (2011 census). The capital of the province is Kundiawa. Mount Wilhelm, the ta ...

in the highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

of Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, dating to the Early Holocene, ~10,000-8,500 years Before Present.

In Tasmania it preferred the woodlands of the midlands and coastal heath

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a cooler a ...

, which eventually became the primary focus of British settlers seeking grazing land for their livestock. The striped pattern may have provided camouflage in woodland conditions, but it may have also served for identification purposes. Paddle (2000), pp. 42–43. The animal had a typical home range of between . It appears to have kept to its home range without being territorial; groups too large to be a family unit were sometimes observed together. Paddle (2000), pp. 38–39.

Ecology and behaviour

Little is known about the behaviour of the thylacine. A few observations were made of the animal in captivity, but only limited, anecdotal evidence exists of the animal's behaviour in the wild. Most observations were made during the day, whereas the thylacine was naturally nocturnal. Those observations, made in the twentieth century, may have been atypical, as they were of a species already under the stresses that would soon lead to its extinction. Some behavioural characteristics have been extrapolated from the behaviour of its close relative, the Tasmanian devil.

The thylacine was a

Little is known about the behaviour of the thylacine. A few observations were made of the animal in captivity, but only limited, anecdotal evidence exists of the animal's behaviour in the wild. Most observations were made during the day, whereas the thylacine was naturally nocturnal. Those observations, made in the twentieth century, may have been atypical, as they were of a species already under the stresses that would soon lead to its extinction. Some behavioural characteristics have been extrapolated from the behaviour of its close relative, the Tasmanian devil.

The thylacine was a nocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

and crepuscular

In zoology, a crepuscular animal is one that is active primarily during the twilight period, being matutinal, vespertine, or both. This is distinguished from diurnal and nocturnal behavior, where an animal is active during the hours of dayli ...

hunter, spending the daylight hours in small caves or hollow tree trunks in a nest of twigs, bark, or fern fronds. It tended to retreat to the hills and forest for shelter during the day. and hunted in the open heath at night. Early observers noted that the animal was typically shy and secretive, with awareness of the presence of humans and generally avoiding contact, though it occasionally showed inquisitive traits. At the time, much stigma existed in regard to its "fierce" nature; this is likely to be due to its perceived threat to agriculture.

Reproduction

There is evidence for at least some year-round breeding (cull records show joeys discovered in the pouch at all times of the year), although the peak breeding season was in winter and spring. They would produce up to four joeys per litter (typically two or three), carrying the young in a pouch for up to three months and protecting them until they were at least half adult size. Early pouch young were hairless and blind, but they had their eyes open and were fully furred by the time they left the pouch. The young also have their own pouches but are not visible until they are 9.5 weeks old. After leaving the pouch, and until they were developed enough to assist, the juveniles would remain in the lair while their mother hunted. Paddle (2000), p. 60. Thylacines only once bred successfully in captivity, inMelbourne Zoo

Melbourne Zoo is a zoo in Melbourne, Australia. It is located within Royal Park in Parkville, approximately north of the centre of Melbourne. It is the primary zoo serving Melbourne. The zoo contains more than 320 animal species from Austr ...

in 1899. Paddle (2000), pp. 228–231. Their life expectancy in the wild is estimated to have been 5 to 7 years, although captive specimens survived up to 9 years.

In 2018, Newton et al. collected and CT-scanned all known preserved thylacine pouch young specimens to digitally reconstruct its development throughout its entire window of growth in the mother's pouch. This study revealed new information on the biology of the thylacine, including the growth of its limbs and when it developed its 'dog-like' appearance. It was found that two of the thylacine young in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) were misidentified and of another species, reducing the number of known pouch young specimens to 11 worldwide. One of four specimens kept at Museum Victoria has been serially sectioned, allowing an in-depth investigation of its internal tissues and providing some insights into thylacine pouch young development, biology, immunology and ecology.

Feeding and diet

The thylacine was exclusively carnivorous. In captivity, thylacines had a clear preference for birds (particularly chickens). In the wild, large ground-dwelling birds (such as Tasmanian nativehens) may have been their primary prey, since they are documented to have hunted a wide range of them, and its comparatively moderate bite force was more suited to hollow avian bones. During its peak occupation of the mainland, such prey would have been bountiful, and studies of their Pleistocene habitat points to a more suitable diet consisting of a range ofmegapodes

The megapodes, also known as incubator birds or mound-builders, are stocky, medium-large, chicken-like birds with small heads and large feet in the family Megapodiidae. Their name literally means "large foot" and is a reference to the heavy leg ...

(such as the Giant malleefowl

''Progura'' is an extinct genus of megapode that was native to Australia. It was described from Plio-Pleistocene deposits at the Darling Downs and Chinchilla in southeastern Queensland by Charles De Vis.

Taxonomy

Comparison of Australian meg ...

) ratite

A ratite () is any of a diverse group of flightless, large, long-necked, and long-legged birds of the infraclass Palaeognathae. Kiwi, the exception, are much smaller and shorter-legged and are the only nocturnal extant ratites.

The systematics ...

s (such as the emu), and possibly dromornithid

Dromornithidae, known as mihirungs and informally as thunder birds or demon ducks, were a clade of large, flightless Australian birds of the Oligocene through Pleistocene Epochs. All are now extinct. They were long classified in Struthioniformes, ...

s (most of which became extinct prior to European settlement). At the time of European settlement, the Tasmanian emu

The Tasmanian emu (''Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis'') is an extinct subspecies of emu. It was found in Tasmania, where it had become isolated during the Late Pleistocene. As opposed to the other insular emu taxa, the King Island emu and t ...

, a subspecies believed to be smaller than mainland emus, was common and widespread and Thylacines were known to prey on them and share the same habitat. Many early depictions of them hunting included emu. The large, flightless bird was hunted to extinction by humans within 30 years of European settlement. The extinction correlates with a rapid decline in thylacine numbers. Paddle (2000), pp. 81. Cassowary

Cassowaries ( tpi, muruk, id, kasuari) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'' in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites (flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones) and are native to the tropical ...

species of northern Australia and New Guinea coexisted with the Thylacine, but had developed strong defenses against predators; the emu on the other hand was more vulnerable to the Thylacine's adaptions including endurance hunting and bipedal hop. Dingo

The dingo (''Canis familiaris'', ''Canis familiaris dingo'', ''Canis dingo'', or ''Canis lupus dingo'') is an ancient ( basal) lineage of dog found in Australia. Its taxonomic classification is debated as indicated by the variety of scienti ...

es, feral dogs, and red fox

The red fox (''Vulpes vulpes'') is the largest of the true foxes and one of the most widely distributed members of the Order (biology), order Carnivora, being present across the entire Northern Hemisphere including most of North America, Europe ...

es have all been noted to hunt the emu on the mainland and killings of emus by dogs were noted in Tasmania. European settlers believed the thylacine to prey upon farmers' sheep and poultry. Paddle (2000), pp. 79–138. Throughout the 20th century, the thylacine was often characterised as primarily a blood drinker; according to Robert Paddle, the story's popularity seems to have originated from a single second-hand account heard by Geoffrey Smith (1881–1916) in a shepherd's hut. Paddle (2000), pp. 29–35.

There is some controversy over the preferred prey size of the thylacine. A 2011 study by the

There is some controversy over the preferred prey size of the thylacine. A 2011 study by the University of New South Wales

The University of New South Wales (UNSW), also known as UNSW Sydney, is a public research university based in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is one of the founding members of Group of Eight, a coalition of Australian research-intensiv ...

using advanced computer modelling indicated that the thylacine had surprisingly feeble jaws. Animals usually take prey close to their own body size, but an adult thylacine of around was found to be incapable of handling prey much larger than . Thus, some researchers believe thylacines only ate small animals such as bandicoot

Bandicoots are a group of more than 20 species of small to medium-sized, terrestrial, largely nocturnal marsupial omnivores in the order Peramelemorphia. They are endemic to the Australia–New Guinea region, including the Bismarck Archipelago t ...

s and possums, putting them into direct competition with the Tasmanian devil

The Tasmanian devil (''Sarcophilus harrisii'') ( palawa kani: purinina) is a carnivorous marsupial of the family Dasyuridae. Until recently, it was only found on the island state of Tasmania, but it has been reintroduced to New South Wales ...

and the tiger quoll

The tiger quoll (''Dasyurus maculatus''), also known as the spotted-tail quoll, the spotted quoll, the spotted-tail dasyure, native cat or the tiger cat, is a carnivorous marsupial of the quoll genus '' Dasyurus'' native to Australia. With male ...

. Another study in 2020 produced similar results, after estimating the average thylacine weight as about rather than , suggesting that the animal did indeed hunt much smaller prey.

However, an earlier study showed that the thylacine had a bite force quotient of 166, similar to that of most quolls; in modern mammalian predators, such a high bite force is almost always associated with predators which routinely take prey as large, or larger than, themselves. If the thylacine was indeed specialised for small prey, this specialisation likely made it susceptible to small disturbances to the ecosystem.

Analysis of the skeletal frame and observations of the thylacine in captivity suggest the species were pursuit predators, singling out a prey item and pursuing them until the prey was exhausted. However, trappers reported it as an ambush predator

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture or trap prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey ...

. The animal may have hunted in small family groups, with the main group herding prey in the general direction of an individual waiting in ambush. Although the living grey wolf is widely seen as the thylacine's counterpart, the thylacine may have been more of an ambush predator as opposed to a pursuit predator. In fact, the predatory behaviour of the thylacine was probably closer to ambushing felids than to large pursuit canids. Its stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

was muscular, and could distend to allow the animal to eat large amounts of food at one time, probably an adaptation to compensate for long periods when hunting was unsuccessful and food scarce.

In captivity, thylacines were fed a wide variety of foods, including dead rabbits and wallabies as well as beef, mutton, horse, and occasionally poultry. Paddle (2000), p. 96. There is a report of a captive thylacine which refused to eat dead wallaby flesh or to kill and eat a live wallaby offered to it, but "ultimately it was persuaded to eat by having the smell of blood from a freshly killed wallaby

A wallaby () is a small or middle-sized macropod native to Australia and New Guinea, with introduced populations in New Zealand, Hawaii, the United Kingdom and other countries. They belong to the same taxonomic family as kangaroos and som ...

put before its nose." Paddle (2000), p. 32.

In 2017, Berns and Ashwell published comparative cortical map Cortical maps are collections (areas) of minicolumns in the brain cortex that have been identified as performing a specific information processing function ( texture maps, color maps, contour maps, etc.).

Cortical maps

Cortical organization, esp ...

s of thylacine and Tasmanian devil

The Tasmanian devil (''Sarcophilus harrisii'') ( palawa kani: purinina) is a carnivorous marsupial of the family Dasyuridae. Until recently, it was only found on the island state of Tasmania, but it has been reintroduced to New South Wales ...

brains, showing that the thylacine had a larger, more modularised basal ganglion

The basal ganglia (BG), or basal nuclei, are a group of subcortical nuclei, of varied origin, in the brains of vertebrates. In humans, and some primates, there are some differences, mainly in the division of the globus pallidus into an extern ...

. The authors associated these differences with the thylacine's predatory lifestyle. The same year, White, Mitchell and Austin published a large-scale analysis of thylacine mitochondrial genomes, showing that they had split into Eastern and Western populations on the mainland prior to the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eu ...

and had low genetic diversity by the time of European arrival.

Relationship with humans

Captivity

By the beginning of the 20th century, the increasing rarity of thylacines led to increased demand for captive specimens by zoos around the world. Despite the export of breeding pairs, attempts at having thylacines in captivity were unsuccessful, and the last thylacine outside Australia died at the London Zoo in 1931.Extinction in the Australian mainland

Australia lost more than 90% of its

Australia lost more than 90% of its megafauna

In terrestrial zoology, the megafauna (from Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and New Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") comprises the large or giant animals of an area, habitat, or geological period, extinct and/or extant. The most common thresho ...

by around 40,000 years ago, with the notable exceptions of several kangaroo species and the thylacine. A 2010 paper examining this issue showed that humans were likely to be one of the major factors in the extinction of many species in Australia although the authors of the research warned that one-factor explanations might be over-simplistic. The thylacine itself likely neared extinction throughout most of its range in mainland Australia by about 2,000 years ago.

However, reliable accounts of thylacine survival in South Australia (though confined to the "thinly settled districts" and Flinders Ranges

The Flinders Ranges are the largest mountain range in South Australia, which starts about north of Adelaide. The ranges stretch for over from Port Pirie to Lake Callabonna.

The Adnyamathanha people are the Aboriginal group who have inhabit ...

) and New South Wales ( Blue Mountains) exist from as late as the 1830s, from both indigenous and European sources. Paddle (2000), pp. 23–24.

A study proposes that the arrival of the dingoes may have led to the extinction of the Tasmanian devil, the thylacine, and the Tasmanian native hen

The Tasmanian nativehen (''Tribonyx mortierii'') (palawa kani: piyura) (alternate spellings: Tasmanian native-hen or Tasmanian native hen) is a flightless rail and one of twelve species of birds endemic to the Australian island of Tasmania. Alt ...

in mainland Australia because the dingo might have competed with the thylacine and devil in preying on the native hen. The study also proposes that an increase in the human population that gathered pace around 4,000 years ago may have led to this.

A counter-argument is that the two species were not in direct competition with one another because the dingo primarily hunts during the day, whereas it is thought that the thylacine hunted mostly at night. Nonetheless, recent morphological examinations of dingo and thylacine skulls show that although the dingo had a weaker bite, its skull could resist greater stresses, allowing it to pull down larger prey than the thylacine. The thylacine was less versatile in its diet than the omnivorous dingo

The dingo (''Canis familiaris'', ''Canis familiaris dingo'', ''Canis dingo'', or ''Canis lupus dingo'') is an ancient ( basal) lineage of dog found in Australia. Its taxonomic classification is debated as indicated by the variety of scienti ...

. Their ranges appear to have overlapped because thylacine subfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains have been discovered near those of dingoes. The adoption of the dingo as a hunting companion by the indigenous peoples would have put the thylacine under increased pressure.

A 2013 study suggested that, while dingoes were a contributing factor to the thylacine's demise on the mainland around 3,000 years ago, larger factors were the intense human population growth and technological advances and the abrupt change in the climate during the period.

Extinction in Tasmania

Although the thylacine was extinct on mainland Australia, it survived into the 1930s on the island state ofTasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. At the time of the first European settlement, the heaviest distributions were in the northeast, northwest and north-midland regions of the state. They were rarely sighted during this time but slowly began to be credited with numerous attacks on sheep. This led to the establishment of bounty schemes in an attempt to control their numbers. The Van Diemen's Land Company introduced bounties on the thylacine from as early as 1830, and between 1888 and 1909 the Tasmanian government

The Tasmanian Government is the democratic administrative authority of the state of Tasmania, Australia. The leader of the party or coalition with the confidence of the House of Assembly, the lower house of the Parliament of Tasmania, is invit ...

paid £1 per head for dead adult thylacines and ten shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

s for pups. In all, they paid out 2,184 bounties, but it is thought that many more thylacines were killed than were claimed for. Its extinction is popularly attributed to these relentless efforts by farmers and bounty hunter

A bounty hunter is a private agent working for bail bonds who captures fugitives or criminals for a commission or bounty. The occupation, officially known as bail enforcement agent, or fugitive recovery agent, has traditionally operated outsid ...

s.

However, it is likely that multiple factors led to its decline and eventual extinction, including competition with wild dogs introduced by European settlers, erosion of its habitat, the concurrent extinction of prey species, and a

However, it is likely that multiple factors led to its decline and eventual extinction, including competition with wild dogs introduced by European settlers, erosion of its habitat, the concurrent extinction of prey species, and a distemper

Distemper may refer to:

Illness

*A viral infection

**Canine distemper, a disease of dogs

** Feline distemper, a disease of cats

** Phocine distemper, a disease of seals

*A bacterial infection

**Equine distemper, or Strangles, a bacterial infect ...

-like disease that affected many captive specimens at the time. Paddle (2000), pp. 202–203. A study from 2012 also found that were it not for an epidemiological influence, the extinction of thylacine would have been at best prevented, at worst postponed. "The chance of saving the species, through changing public opinion, and the re-establishment of captive breeding, could have been possible. But the marsupi-carnivore disease, with its dramatic effect on individual thylacine longevity and juvenile mortality, came far too soon, and spread far too quickly."

Whatever the reason, the animal had become extremely rare in the wild by the late 1920s. Despite the fact that the thylacine was believed by many to be responsible for attacks on sheep, in 1928 the Tasmanian Advisory Committee for Native Fauna recommended a reserve similar to the Savage River National Park

Savage River National Park is located in north-west Tasmania, Australia. Established in April 1999, it is the largest undisturbed area of temperate rainforest in Australia since the era of the thylacine. Unlike other national parks of Tasmania ...

to protect any remaining thylacines, with potential sites of suitable habitat including the Arthur

Arthur is a common male given name of Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. Another theory, more wi ...

- Pieman area of western Tasmania.

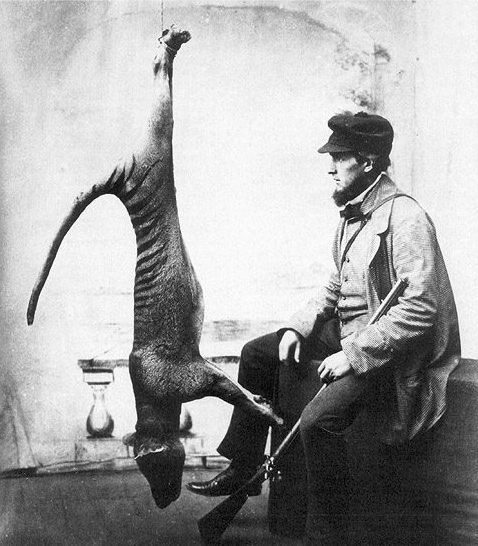

The last known thylacine to be killed in the wild was shot in 1930 by Wilf Batty, a farmer from Mawbanna in the state's northwest. The animal, believed to have been a male, had been seen around Batty's house for several weeks.

Work in 2012 examined the relationship of the genetic diversity of the thylacines before their extinction. The results indicated that the last of the thylacines in Tasmania had limited genetic diversity due to their complete geographic isolation from mainland Australia. Further investigations in 2017 showed evidence that this decline in genetic diversity started long before the arrival of humans in Australia, possibly starting as early as 70–120 thousand years ago.

Henry Burrell

Henry (Harry) James Burrell OBE (19 January 1873 – 29 July 1945) was an Australian naturalist who specialised in the study of monotremes. He was the first person to successfully keep the platypus in captivity and was a lifelong collector o ...

of a thylacine with a chicken was widely distributed and may have helped secure the animal's reputation as a poultry thief. In fact the image is cropped to hide the fenced run and housing, and analysis by one researcher has concluded that this thylacine is a mounted

Mount is often used as part of the name of specific mountains, e.g. Mount Everest.

Mount or Mounts may also refer to:

Places

* Mount, Cornwall, a village in Warleggan parish, England

* Mount, Perranzabuloe, a hamlet in Perranzabuloe parish, Co ...

specimen, posed for the camera. The photograph may even have involved photo manipulation.

File:Wilf Batty last wild Thylacine.jpg, Wilf Batty with the last thylacine that was killed in the wild.

Tasmanian_Tiger_Trap_1823_Thomas_Scott.jpg, Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) trap, intended for Mount Morriston, 1823, by Thomas Scott

Benjamin and searches

The last captive thylacine, often referred to as Benjamin, lived as an

The last captive thylacine, often referred to as Benjamin, lived as an endling

An endling is the last known individual of a species or subspecies. Once the endling dies, the species becomes extinct. The word was coined in correspondence in the scientific journal ''Nature''. Alternative names put forth for the last indi ...

; (the known last of its species), at Hobart Zoo

The Hobart Zoo (also known as Beaumaris Zoo) was an old-fashioned zoological garden located on the Queen's Domain in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. The Zoo site is very close to the site of the Tasmanian Governor's House, and the Botanical Gard ...

until its death on the night of September 6, 1936. Its source has long been disputed. Until recently, Elias Churchill was regularly quoted as being the captor, but there appears to be little evidence to support this claim. Two more recent candidates are far better placed evidentially as the probable source – the Kaine capture near Preolenna in 1931 and the Delphin capture near Waratah in 1930. The thylacine died on the night of 6–7 September 1936. It is believed to have died as the result of neglect—locked out of its sheltered sleeping quarters, it was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: extreme heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night. Paddle (2000), p. 195. This thylacine features in the last known motion picture footage of a living specimen: 45 seconds of black-and-white footage showing the thylacine in its enclosure in a clip taken in 1933, by naturalist David Fleay

David Howells Fleay (; 6 January 1907 – 7 August 1993) was an Australian scientist and biologist who pioneered the captive breeding of endangered species, and was the first person to breed the platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus'') in ...

. In the film footage, the thylacine is seen seated, walking around the perimeter of its enclosure, yawning, sniffing the air, scratching itself (in the same manner as a dog), and lying down. Fleay was bitten on the buttock whilst shooting the film. In 2021, a digitally colourised 80-second clip of Fleay's footage of Benjamin was released by the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, to mark National Threatened Species Day. The digital colourisation process was completed by a Paris-based company, based on historic primary and secondary descriptions to ensure an as exact colour match as possible. The location of remains of a later Thylacine have been discovered in a cupboard in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in December 2022.

Frank Darby, who claimed to have been a keeper at Hobart Zoo, suggested Benjamin as having been the animal's pet name in a newspaper article of May 1968. No documentation exists to suggest that it ever had a pet name, and Alison Reid (''de facto'' curator at the zoo) and Michael Sharland (publicist for the zoo) denied that Frank Darby had ever worked at the zoo or that the name Benjamin was ever used for the animal. Darby also appears to be the source for the claim that the last thylacine was a male. Paddle (2000), pp. 198–201. Robert Paddle was unable to uncover any records of any Frank Darby having been employed by Beaumaris/Hobart Zoo during the time that Reid or her father was in charge and noted several inconsistencies in the story Darby told during his interview in 1968.

The sex of the last captive thylacine has been a point of debate since its death at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. In 2011, a detailed examination of a single frame from the motion film footage confirmed that the thylacine was male. When frame III is enlarged the scrotum

The scrotum or scrotal sac is an anatomical male reproductive structure located at the base of the penis that consists of a suspended dual-chambered sac of skin and smooth muscle. It is present in most terrestrial male mammals. The scrotum co ...

can be seen; and by enhancing the frame, the outline of the individual testes

A testicle or testis (plural testes) is the male reproductive gland or gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testes are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testoste ...

is discernable.

After the thylacine's death, the zoo expected that it would soon find a replacement, and "Benjamin"'s death was not reported on in the media at the time. Although there had been a conservation movement

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the ...

pressing for the thylacine's protection since 1901, driven in part by the increasing difficulty in obtaining specimens for overseas collections, political difficulties prevented any form of protection coming into force until 1936. Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government was introduced on 10 July 1936, 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity. Paddle (2000), p. 184.

A thylacine was reportedly shot and photographed at Mawbanna in 1938. A 1957 sighting from a helicopter could not be confirmed on the ground. An animal killed in Sandy Cape

Sandy Cape (also known by the Indigenous name of Woakoh) is the most northern point on Fraser Island (also known as K'gari and Gari) off the coast of Queensland, Australia. The place was named ''Sandy Cape'' for its appearance by James Cook dur ...

at night in 1961 was tentatively identified as a thylacine. The results of subsequent searches indicated a strong possibility of the survival of the species in Tasmania into the 1960s. Searches by Dr. Eric Guiler and David Fleay in the northwest of Tasmania found footprint

Footprints are the impressions or images left behind by a person walking or running. Hoofprints and pawprints are those left by animals with hooves or paws rather than feet, while "shoeprints" is the specific term for prints made by shoes. The ...

s and scats

The Sydney Coordinated Adaptive Traffic System, abbreviated SCATS, is an intelligent transportation system that manages the dynamic (on-line, real-time) timing of signal phases at traffic signals, meaning that it tries to find the best phasing (i ...

that may have belonged to the animal, heard vocalisations matching the description of those of the thylacine, and collected anecdotal evidence from people reported having sighted the animal.

Despite the searches, no conclusive evidence was found to point to its continued existence in the wild. Between 1967 and 1973, zoologist Jeremy Griffith

Jeremy Griffith (born 1945) is an Australian biologist and author. He first came to public attention for his attempts to find the Tasmanian tiger. He later became noted for his writings on the human condition and theories about human progress, w ...

and dairy farmer James Malley conducted what is regarded as the most intensive search ever carried out, including exhaustive surveys along Tasmania's west coast, installation of automatic camera stations, prompt investigations of claimed sightings, and in 1972 the creation of the Thylacine Expeditionary Research Team with Dr. Bob Brown

Robert James Brown (born 27 December 1944) is a former Australian politician, medical doctor and environmentalist. He was a senator and the parliamentary leader of the Australian Greens. Brown was elected to the Australian Senate on the Tasma ...

, which concluded without finding any evidence of the thylacine's existence.

The thylacine held the status of endangered species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inv ...

until the 1980s. International standards at the time stated that an animal could not be declared extinct until 50 years had passed without a confirmed record. Since no definitive proof of the thylacine's existence in the wild had been obtained for more than 50 years, it met that official criterion and was declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

in 1982 and by the Tasmanian government in 1986. The species was removed from Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of intern ...

) in 2013.

Unconfirmed sightings

The

The Department of Conservation and Land Management

The Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) was a department of the Government of Western Australia that was responsible for implementing the state's conservation and environment legislation and regulations. It was created by the ...

recorded 203 reports of sightings of the thylacine in Western Australia from 1936 to 1998. On the mainland, sightings are most frequently reported in Southern Victoria.

Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

.

In January 1995, a Parks and Wildlife officer reported observing a thylacine in the Pyengana region of northeastern Tasmania in the early hours of the morning. Later searches revealed no trace of the animal. In 1997, it was reported that locals and missionaries near Mount Carstensz

Puncak Jaya (; literally "Glorious Peak") or Carstensz Pyramid, Mount Jayawijaya or Mount Carstensz () on the island of New Guinea, with an elevation of , is the highest mountain peak of an island on Earth. The mountain is located in the Sud ...

in Western New Guinea had sighted thylacines. The locals had apparently known about them for many years but had not made an official report. In February 2005 Klaus Emmerichs, a German tourist, claimed to have taken digital photographs of a thylacine he saw near the Lake St Clair National Park, but the authenticity of the photographs has not been established. The photos were published in April 2006, fourteen months after the sighting. The photographs, which showed only the back of the animal, were said by those who studied them to be inconclusive as evidence of the thylacine's continued existence.

In light of two detailed sightings around 1983 from the remote Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest unspoiled wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupación ...

of mainland Australia, scientists led by Bill Laurance

Bill Laurance (born 2 April 1981) is an English composer, producer, and multi-instrumental musician. Laurance is a member of jazz fusion and funk band Snarky Puppy, as well as founder and CEO of London-based record label Flint Music.

Bio ...

announced plans in 2017 to survey the area for thylacines using camera trap

A camera trap is a camera that is automatically triggered by a change in some activity in its vicinity, like presence of an animal or a human being. It is typically equipped with a motion sensor – usually a passive infrared (PIR) senso ...

s.

In 2017, 580 camera traps were deployed in North Queensland by James Cook University

James Cook University (JCU) is a public university in North Queensland, Australia. The second oldest university in Queensland, JCU is a teaching and research institution. The university's main campuses are located in the tropical cities of Cairn ...

after two people – an experienced outdoorsman and a former Park Ranger – reported having seen a thylacine there in the 1980s but being too embarrassed to tell anyone at the time.

According to the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment

The Tasmanian Department of Natural Resources and Environment (NRE) is the government department of the Tasmanian Government responsible for supporting primary industry development, the protection of Tasmania's natural environment, effective lan ...

, there have been eight unconfirmed thylacine sighting reports between 2016 and 2019, with the latest unconfirmed visual sighting on 25 February 2018.

Since the disappearance and effective extinction of the thylacine, speculation and searches for a living specimen have become a topic of interest to some members of the cryptozoology

Cryptozoology is a pseudoscience and subculture that searches for and studies unknown, legendary, or extinct animals whose present existence is disputed or unsubstantiated, particularly those popular in folklore, such as Bigfoot, the Loch Ness ...

subculture. Loxton, Daniel and Donald Prothero

Donald Ross Prothero (February 21, 1954) is an American geologist, paleontologist, and author who specializes in mammalian paleontology and magnetostratigraphy, a technique to date rock layers of the Cenozoic era and its use to date the climate ...

. ''Abominable Science!: Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids'', p. 323 & 327. Columbia University Press

Columbia University Press is a university press based in New York City, and affiliated with Columbia University. It is currently directed by Jennifer Crewe (2014–present) and publishes titles in the humanities and sciences, including the fie ...

. The search for the animal has been the subject of books and articles, with many reported sightings that are largely regarded as dubious. According to writer Errol Fuller

Errol Fuller (born 19 June 1947) is an English writer and artist who lives in Tunbridge Wells, Kent. He was born in Blackpool, Lancashire, grew up in South London, and was educated at Addey and Stanhope School. He is the author of a series of bo ...

, the most likely record of the species persistence was proposed by Athol Douglas Athol may refer to:

Places

Scotland

* Atholl, Scotland, a district in central Scotland

Canada

* Athol, Nova Scotia, a small community

* Athol, Prince Edward County, Ontario, a municipality and census division

* Athol, a rural community in North ...

in the journal ''Cryptozoology'', where Douglas challenges the carbon dating of the specimen found at Mundrabilla in South Australia as 4,500 years old; Douglas proposed instead that the well-preserved thylacine carcass was several months old when discovered. The dating of the specimen has not been reassessed.

A preliminary 2021 study published by Brook

A brook is a small river or natural stream of fresh water. It may also refer to:

Computing

*Brook, a programming language for GPU programming based on C

*Brook+, an explicit data-parallel C compiler

* BrookGPU, a framework for GPGPU programmin ...

''et al.''. compiles many of the alleged sightings of thylacines in Tasmania throughout the 20th century and claims that contrary to beliefs that thylacines went extinct in the 1930s, the Tasmanian thylacine may have actually lasted throughout the 20th century with a window of extinction between the 1980s and the present day, with the likely extinction date being between the late 1990s and early 2000s. The study claims that the reason behind the apparent lack of confirmed sightings during this wide and relatively recent time range is the lack of wide deployment of camera trap

A camera trap is a camera that is automatically triggered by a change in some activity in its vicinity, like presence of an animal or a human being. It is typically equipped with a motion sensor – usually a passive infrared (PIR) senso ...

s (which have been used to rediscover other elusive carnivores, such as the Zanzibar leopard

The Zanzibar leopard is an African leopard (''Panthera pardus pardus'') population on Unguja Island in the Zanzibar archipelago, Tanzania, that is considered extirpated due to persecution by local hunters and loss of habitat. It was the island's ...

) in Tasmania until the early 21st century, by which time the thylacine would be extinct or very nearly so. (This study has not yet been peer-reviewed

Peer review is the evaluation of work by one or more people with similar competencies as the producers of the work ( peers). It functions as a form of self-regulation by qualified members of a profession within the relevant field. Peer revie ...

.)

Rewards

In 1983, the Americanmedia mogul

A media proprietor, media mogul or media tycoon refers to a entrepreneur who controls, through personal ownership or via a dominant position in any media-related company or enterprise, media consumed by many individuals. Those with significant co ...

Ted Turner

Robert Edward "Ted" Turner III (born November 19, 1938) is an American entrepreneur, television producer, media proprietor, and philanthropist. He founded the Cable News Network (CNN), the first 24-hour cable news channel. In addition, he ...

offered a $100,000 reward for proof of the continued existence of the thylacine. A letter sent in response to an inquiry by a thylacine-searcher, Murray McAllister in 2000, indicated that the offer had been withdrawn. In March 2005, Australian news magazine '' The Bulletin'', as part of its 125th anniversary celebrations, offered a $1.25 million reward for the safe capture of a live thylacine. When the offer closed at the end of June 2005, no one had produced any evidence of the animal's existence. An offer of $1.75 million has subsequently been offered by a Tasmanian tour operator, Stewart Malcolm. Trapping is illegal under the terms of the thylacine's protection, so any reward made for its capture is invalid, since a trapping license would not be issued.

Research

The

The Australian Museum

The Australian Museum is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It is the oldest museum in Australia,Design 5, 2016, p.1 and the fifth oldest natural history museum in the ...

in Sydney began a cloning